Chapter 37 Bowel elimination

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Discuss the role of gastrointestinal organs in digestion and elimination.

• Describe four functions of the large intestine.

• Explain the physiological aspects of normal defecation.

• Discuss psychological and physiological factors that influence the elimination process.

• Describe common physiological alterations in elimination.

• Assess a patient’s elimination pattern.

• List nursing diagnoses related to common alterations in elimination.

• Describe nursing implications for common diagnostic examinations of the gastrointestinal tract.

• Administer a pre-packaged enema.

• Describe nursing measures that promote normal bowel function.

• Discuss the relationship between the structure and function of bowel diversions and the nursing care required.

• Use critical thinking in the provision of care to patients with alterations in bowel elimination.

Regular elimination of bowel waste products is essential for normal body functioning. Alterations in elimination are often early signs or symptoms of problems within the gastrointestinal or other body systems. Because bowel function depends on the balance of several factors, elimination patterns and habits vary among individuals.

People who are hospitalised have additional risk factors for bowel problems, such as immobility, bed rest, altered diet, surgery and narcotic-type pain medications. To promote normal function and manage patients’ elimination problems, an understanding of normal elimination and factors that promote, impede or cause alterations in elimination is required.

Scientific knowledge base

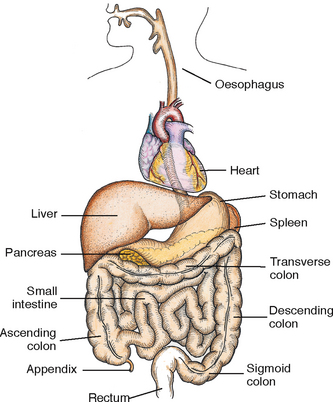

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a series of hollow, mucous-membrane-lined muscular organs. The purposes of these organs are to absorb fluid and nutrients, prepare food for absorption and use by the body’s cells, and provide for temporary storage of faeces (Figure 37-1). The volume of fluids absorbed by the GI tract is high, making fluid balance a key function of the GI system. In addition to ingested fluids and foods, the GI tract receives secretions from organs such as the gallbladder and the pancreas. Any condition that seriously impairs normal absorption or secretion of GI fluids could cause fluid imbalance.

FIGURE 37-1 Organs of the gastrointestinal tract (with the heart as a reference point).

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of Nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

Mouth

Digestion begins in the mouth, where mechanical and chemical breakdown of nutrients occurs. The teeth masticate (chew) food, breaking it down to a suitable size for swallowing. Salivary secretions contain enzymes, such as ptyalin, that initiate digestion of certain food elements. Saliva dilutes and softens the bolus of food in the mouth for easier swallowing.

Oesophagus

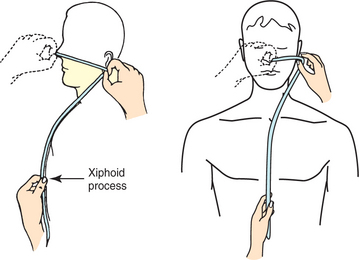

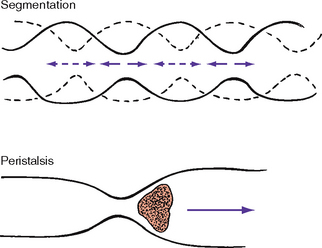

As food enters the upper oesophagus, it passes through the upper oesophageal sphincter, which is a circular muscle that prevents air from entering the oesophagus and food from refluxing (moving backwards) into the throat. The bolus of food travels approximately 25 cm down the oesophagus. Food is pushed along by slow peristalsis produced by alternating involuntary contractions and relaxations of smooth muscle. As a portion of the oesophagus contracts above the food bolus, the circular muscle below (or in front) of the bolus relaxes. This alternate contraction–relaxation of smooth muscle propels food towards the next wave (Figure 37-2).

FIGURE 37-2 Segmented and peristaltic waves.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of Nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

In 15 seconds the bolus of food moves down the oesophagus and reaches the lower oesophageal sphincter. The lower oesophageal (or cardiac) sphincter lies between the oesophagus and stomach and prevents backward movement of fluids from the stomach to the oesophagus. Factors influencing cardiac sphincter efficacy include antacids, which minimise reflux, and fatty foods and nicotine, which increase reflux.

Stomach

In the stomach, food is temporarily stored and mechanically and chemically broken down for digestion and absorption (see Chapter 36). The stomach secretes hydrochloric acid (HCl), mucus, the enzyme pepsin, and intrinsic factor. The concentration of hydrochloric acid influences stomach acidity and the body’s acid–base balance (see Chapter 39), and helps mix and break down food. Prostaglandins assist in the formation of mucus, which protects the stomach mucosa from acidity and enzyme activity. Pepsin digests proteins, although not much digestion occurs in the stomach. Intrinsic factor is the essential component needed for vitamin B12 absorption in the intestine and subsequent normal red blood cell formation. Lack of this intrinsic factor results in a condition called pernicious anaemia.

Before food leaves the stomach, it is changed into a semifluid material called chyme. Chyme is more easily digested and absorbed than solid food. Patients who have portions of their stomachs removed, have had a gastroplasty or have rapid stomach emptying (as with gastritis) may have serious digestive problems because food is not broken down into chyme.

Small intestine

During normal digestion, chyme leaves the stomach and enters the small intestine. The small intestine is a tube about 2.5 cm in diameter and 6 m long. It contains three divisions: duodenum, jejunum and ileum. Chyme mixes with digestive enzymes (e.g. bile and amylase) while travelling through the small intestine. Segmentation (alternating contraction and relaxation of smooth muscle) churns the chyme, further breaking down food for digestion (see Figure 37-2). These alternating contractions occur about 12 times a minute. As chyme mixes, forward peristaltic movement temporarily ceases, permitting absorption. Chyme travels slowly through the small intestine to allow absorption of nutrients and electrolytes.

Enzymes from the pancreas (e.g. amylase) and bile from the gallbladder are released into the duodenum. The enzymes in the small intestine break down fats, proteins and carbohydrates into basic elements (see Chapter 36). Nutrients are almost entirely absorbed by the duodenum and jejunum, although the ileum absorbs certain vitamins, iron and bile salts. If the function of the small intestine is impaired, the digestive process is greatly altered. For example, inflammation, surgical resection or obstruction can disrupt peristalsis, reduce the area of absorption or block passage of chyme.

Large intestine

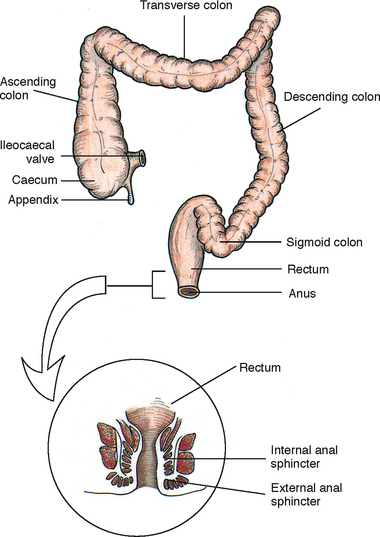

The lower GI tract is called the large intestine because it is larger in diameter than the small intestine. However, its length of 1.5–1.8 m is much shorter. The large intestine is divided into the caecum, colon and rectum (Figure 37-3). It is responsible for the absorption of water and is the primary organ of bowel elimination.

FIGURE 37-3 Divisions of the large intestine.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of Nursing, 8 ed. St Louis, Mosby.

Caecum

Unabsorbed chyme enters the large intestine at the caecum through the ileocaecal valve. This valve is a circular muscle layer that prevents colon contents from regurgitating and returning to the small intestine. Located at the end of the caecum is the vermiform appendix. Inflammation of this area can result in blockage of the appendix, leading to appendicitis.

Colon

Although watery chyme enters the colon, the volume of water lessens as chyme moves along it. The colon is divided into the ascending, transverse, descending and sigmoid colon. The colon is made of muscular tissue, which allows it to accommodate and thus eliminate large quantities of waste.

The colon has four interrelated functions: absorption, protection, secretion and elimination. A large volume of water and significant amounts of sodium and chloride are absorbed by the colon daily. As food passes through the colon, haustral contractions occur. These are similar to segmental contractions of the small intestine but last longer, up to 5 minutes. The contractions produce large sacs in the colon’s wall, providing a large surface area for absorption.

As much as 2.5 L of water can be absorbed by the colon in 24 hours. On average, 55 mmol of sodium and 23 mmol of chloride are absorbed daily. The amount of water absorbed from chyme depends on the speed at which colonic contents move. Chyme is normally a soft, formed mass. If the speed of peristaltic contractions is abnormally fast, there is less time for water to be absorbed and the stool will be more liquid. If peristaltic contractions slow down, water continues to be absorbed and a hard mass of stool forms, resulting in constipation.

The colon protects itself by secreting a supply of mucus. Mucus is normally clear to opaque, with a stringy consistency. Mucus lubricates the colon, preventing trauma to its inner walls. Lubrication is especially important near the distal end of the colon, where contents become drier and harder. The secretory function of the colon aids in electrolyte balance. Bicarbonate is secreted in exchange for chloride. About 4–9 mmol of potassium is released each day by the large intestine. Serious alterations in colon function, such as diarrhoea, can cause electrolyte imbalance due to loss of potassium and chloride.

Finally, the colon eliminates waste products and gas (flatus). Flatus results from air swallowing, diffusion of gas from the bloodstream into the intestine, and bacterial action on non-absorbable carbohydrates. Fermentation of carbohydrates (such as in cabbage and onions) produces intestinal gas, which can stimulate peristalsis. An adult normally forms 400–700 mL of flatus daily.

Slow peristaltic contractions move contents through the colon. Intestinal content is the main stimulus for contraction. Waste products and gas exert pressure against the walls of the colon. The muscle layer stretches, stimulating the reflex that initiates contraction. Mass peristaltic movements push undigested food towards the rectum. These movements occur only three or four times daily, unlike the frequent peristaltic waves in the small intestine (usually heard during auscultation). When these mass peristaltic movements occur, large segments of the colon contract as a result of gastrocolic reflex and duodenocolic reflex responses. These occur when the stomach or duodenum is filled with food. Filling initiates nerve impulses that stimulate the colon’s muscular walls. Mass peristalsis is strongest during the hour after a meal.

Rectum

Waste products that reach the sigmoid portion of the colon are called faeces. The sigmoid stores faeces until just before defecation. The rectum is the final division of the GI tract. Its length varies according to age:

| Infant | 2.5–4 cm |

| Toddler | 5 cm |

| Preschooler | 7.5 cm |

| School-age child | 10 cm |

| Adult | 15–20 cm |

Normally the rectum is empty of faeces until defecation. It contains vertical and transverse folds of tissue. Each vertical fold contains an artery and veins. If the veins become distended from pressure during the straining, haemorrhoids form. Haemorrhoids can make defecation painful.

When the faecal mass or gas moves into the rectum to distend its walls, defecation begins. The process involves involuntary and voluntary control. The internal sphincter is a smooth muscle innervated by the autonomic nervous system. As the rectum distends, sensory nerves are stimulated and carry impulses that cause the internal sphincter to relax, allowing more faeces to enter the rectum. At the same time, impulses travel to the brain to create awareness of the need to defecate.

As the internal sphincter relaxes, so does the external sphincter. Adults and toilet-trained children can voluntarily control the external sphincter. If the time for defecation is not right, constriction of the levator ani muscles closes the anus and defecation is delayed. At the time of defecation, the external sphincter relaxes. Pressure can be exerted to expel faeces through an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, or a Valsalva manoeuvre. A Valsalva manoeuvre is voluntary contraction of abdominal muscles during forced expiration with a closed glottis (holding one’s breath while straining).

Nursing knowledge base

Factors affecting bowel elimination

Many factors influence the process of bowel elimination. Knowledge of these factors enables identification of people at risk and the appropriate selection of intervention(s) to prevent or alleviate the symptoms of altered bowel elimination.

Age

Developmental changes that affect elimination occur throughout life. An infant has a small stomach capacity and less secretion of digestive enzymes. Some foods, such as complex starches, are tolerated poorly. Food passes quickly through an infant’s intestinal tract because of rapid peristalsis. The infant is unable to control defecation because of a lack of neuromuscular development (see Working with diversity). This development usually does not take place until 2–3 years of age.

During adolescence, there is rapid growth of the large intestine. The secretion of HCl increases, particularly in boys. Adolescents typically eat more.

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON INFANTS AND CHILDREN

• Normally, a healthy newborn infant has a bowel motion within 24–36 hours of birth. This first stool is called meconium and is a thick greenish-black material.

• The frequency of bowel movements in babies can be affected by their feeding regimen. Breastfed babies tend to have more-frequent bowel actions than those fed with formula. They may have an average of three bowel actions per day.

• The stools of babies are a yellow colour, gradually assuming more adult characteristics as solid food is introduced into the diet after 6 months of age. By the age of 3 years, a child will normally have one soft bowel movement each day.

Adapted from Greenwald B 2010 Clinical practice guidelines for paediatric constipation. J Acad Nurse Pract 22:332–8; Hockenberry M, Wilson D 2011 Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 9. St Louis, Mosby.

Older adults often experience changes in the GI system that impair digestion and elimination (Ebersole and Hess, 2012). These changes in the GI tract that occur with ageing are given in Table 37-1. In addition, peristaltic action declines with age, and oesophageal emptying slows. Sluggish emptying of the oesophagus can cause discomfort in the epigastric section of the abdomen. Absorptive properties of the intestinal mucosa change, causing protein, vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Older adults may also have decreased tone in the pelvic floor muscles and anal sphincter. Although the integrity of the external sphincter may remain intact, frail older adults may have difficulty controlling bowel evacuation. Because of slowing of nerve impulses, some are less aware of the need to defecate and are likely to become constipated.

TABLE 37-1 NORMAL CHANGES IN THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT FROM AGEING

| PORTION OF GI TRACT | CHANGES | CAUSES |

|---|---|---|

| Mouth | Degeneration of cells, use of some medications | |

| Oesophagus | Reduced peristalsis, especially in lower third in late older age (85+ years) | Degeneration of neural cells |

| Stomach | Decrease in acid secretions | |

| Decrease in motor activity | Delayed gastric emptying and fewer hunger contractions | |

| Decrease in mucosal thickness | Loss of parietal cells also leads to loss of intrinsic factor, which is needed for vitamin B12 absorption | |

| Small intestine | Absorption of most nutrients and minerals not significantly affected | |

| Large intestine | ||

| Liver | Reduced storage capacity and ability to synthesise protein and medications |

Source: Feldstein RC, Tepper RE, Katz S 2010 Geriatric gastroenterology—an overview. In Fillit HM, Rockwood K, Woodhouse A, editors, Brocklehurst’s Textbook of geriatric medicine and gerontology, ed 7. Philadelphia, Saunders, pp. 106–10. DOI: 10.1016/B978-1-4160-6231-8.10017-0.

Diet

The food that a person eats influences elimination. Regular daily food intake helps maintain a regular pattern of peristalsis in the colon. Fibre, the indigestible residue in the diet, provides the bulk in faecal material. Bulk-forming foods absorb fluids, thereby increasing stool mass. The bowel walls are stretched, creating peristalsis and initiating the defecation reflex. An infant’s immature bowel cannot usually tolerate fibre-containing foods until several months of age. The following foods contain a high amount of fibre (see Chapter 36):

• raw fruits (apples, bananas, oranges)

• cooked fruits (prunes, apricots)

• raw vegetables (celery, green beans, zucchini)

• whole grains (cereal, bran flakes, breads) (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2008).

Ingestion of a high-fibre diet improves the likelihood of a normal elimination pattern if other factors are normal. Gas-producing foods such as onions, cauliflower and beans also stimulate peristalsis. The gas formed distends intestinal walls, increasing colon motility. Some spicy foods can increase peristalsis but can also cause indigestion and watery stools.

Some foods, such as milk and milk products, are difficult or impossible for some people to digest. These people are known as lactose intolerant; this condition bears a genetic link. Lactose-intolerant people are unable to digest lactose (milk sugar) due to an inadequate production of the enzyme lactase. Intolerance to lactose-containing foods results in diarrhoea, abdominal cramping and gaseous distension. Some children with lactose intolerance can tolerate cheese and yoghurt (McCance and Huether, 2010).

Fluid intake

An inadequate intake of fluids affects the character of faeces. Fluid liquefies the intestinal contents, easing its passage through the colon. Inadequate fluid intake may slow passage of food through the intestine and can result in hardening of stool contents.

Physical activity

Physical activity promotes peristalsis. Therefore, it is important to encourage people to move around as quickly as possible following surgery or serious illness. Additionally, weakened abdominal and pelvic floor muscles impair the ability to increase intra-abdominal pressure and to control the external sphincter.

Personal habits

Personal elimination habits influence bowel function. Most people benefit from being able to use their own toilet facilities at a time that is most effective and convenient for them. A busy work schedule may prevent the individual from responding appropriately to the urge to defecate, disrupting regular habits and causing possible alterations such as constipation.

Hospitalised patients can rarely maintain privacy during defecation. Bathroom facilities are often shared with another person whose hygiene habits might be quite different. The patient’s illness often limits physical activity and requires the use of a bed pan or bedside commode. The sights, sounds and odours associated with sharing toilet facilities or using bed pans are often embarrassing. Embarrassment prompts patients to ignore the urge to defecate, which can begin a vicious circle of constipation and discomfort.

Position during defecation

Squatting is the normal position during defecation. Modern toilets are designed to facilitate this posture, allowing the person to lean forward, exert intra-abdominal pressure and contract the thigh muscles. For the patient immobilised in bed, defecation is often difficult. In a supine position it is impossible to contract the muscles used during defecation. If allowable within the patient’s condition, raise the head of the bed; this helps the patient to a more normal sitting position on a bed pan, enhancing the ability to defecate.

Psychological factors

The function of almost all body systems can be impaired by prolonged emotional stress (see Chapter 42). If an individual becomes anxious, afraid or angry, the stress response is initiated, allowing the body to restore defences. The digestive process is accelerated, and peristalsis is increased to provide nutrients needed for defence. Side effects of increased peristalsis are diarrhoea and gaseous distension.

Pain

Normally the act of defecation is painless. However, a number of conditions, including haemorrhoids, rectal surgery, rectal fistulas and abdominal surgery, can result in discomfort. In these instances the patient often suppresses the urge to defecate to avoid pain. Constipation is a common consequence for people who experience pain during defecation.

Pregnancy

As pregnancy advances and the size of the fetus increases, pressure is exerted on the rectum. A temporary obstruction created by the fetus impairs passage of faeces. Slowing of peristalsis during the third trimester often leads to constipation.

Surgery and anaesthesia

Some general anaesthetic agents used during surgery cause temporary cessation of peristalsis (see Chapter 44). The patient who receives local or regional anaesthesia is less at risk of elimination alterations because bowel activity is affected minimally or not at all.

Surgery that involves direct manipulation of the bowel can temporarily stop peristalsis. This condition, called paralytic ileus, usually lasts about 24–48 hours. If the patient remains inactive or is unable to eat after surgery, return of normal bowel function may be further delayed.

Infection

It is known that Helicobacter pylori is an infection that contributes to the development of gastric ulcers and gastritis, and can lead to gastric cancers (Bornschein and others, 2010). Chronic gastritis can occur in the older adult, leading to degeneration of the stomach wall and altered digestion and elimination (McCance and Huether, 2010).

Medications

Many common medications can affect bowel elimination (Table 37-2). These effects include slowing peristalsis, increasing peristalsis and changing the bowel flora. Laxatives, cathartics and stool softeners soften the stool and promote peristalsis. Although similar to cathartics, laxatives are milder in action. When used correctly, laxatives and cathartics safely promote and maintain normal elimination patterns. However, long-term use of cathartics causes the large intestine to lose muscle tone and become less responsive to stimulation by laxatives. Laxative overuse can also cause serious diarrhoea that can lead to dehydration and electrolyte depletion.

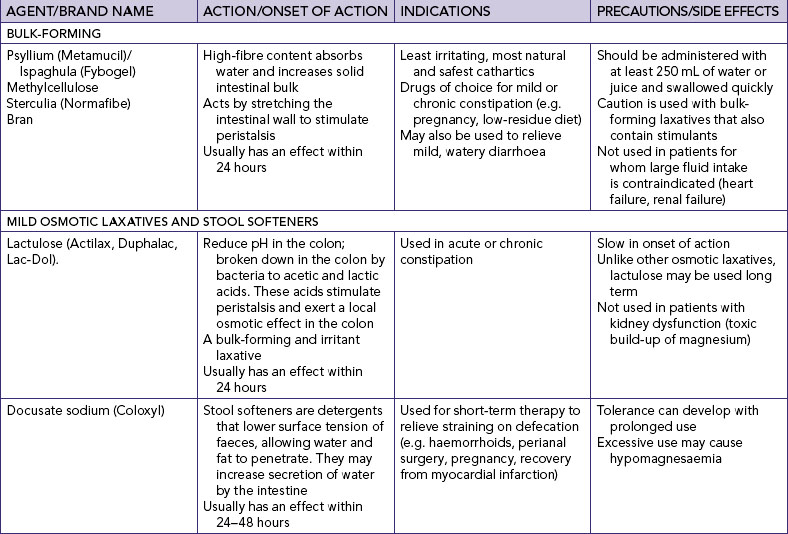

TABLE 37-2 MEDICATIONS AND THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM

| MEDICATIONS | ACTION |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | May produce diarrhoea by disrupting the normal bacterial flora in the GI tract, especially if administered orally. If the diarrhoea and associated abdominal cramping become severe, the patient might need to change medications |

| Anticholinergic drugs, such as atropine | Inhibit gastric acid secretion and depress gastrointestinal (GI) motility (Bryant and Knights, 2010). Although useful in treating hyperactive bowel disorders, anticholinergics can cause constipation |

| Anticholinergic/antispasmodic drugs, such as dicyclomine HCl (Merbentyl) | Suppresses peristalsis and can decrease gastric emptying |

| Aspirin | A prostaglandin inhibitor, it can interfere with the formation and production of protective mucus and can predispose patients to gastritis |

| Histamine-2 (H2) antagonists | Suppress the secretion of hydrochloric acid and may interfere with the digestion of some foods |

| Iron | Can cause discolouration of the stool (black) and lead to constipation |

| Narcotic analgesics | Slow peristalsis and segmental contractions, often resulting in constipation |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Promote gastrointestinal irritation that can range from dyspepsia to life-threatening haemorrhage (Bryant and Knights, 2010) |

Bryant B, Knights K 2010 Pharmacology for health professionals, ed 3. Sydney, Mosby; Tiziani A 2010 Havard’s nursing guide to drugs, ed 8. Sydney, Mosby.

Diagnostic tests

Diagnostic examinations that involve viewing of GI structures often require portions of the bowel to be empty of contents. In the case of evaluation through the use of an enema or endoscopy, the patient usually has a low-residue diet for 3 days and receives cathartics until the bowel contents that are expelled are clear. Such emptying of the bowel can interfere with elimination until normal eating is resumed. The patient is not allowed to eat or drink after midnight of the day preceding examinations such as endoscopy of the lower GI tract (colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy).

Common bowel elimination problems

Nurses commonly care for people who have, or are at risk of, elimination problems because of physiological changes in the GI tract, surgical alteration of intestinal structures, other prescribed therapy or disorders impairing defecation.

Constipation

Constipation is noted by a decrease in frequency of normal bowel movements, normally accompanied by straining and prolonged or difficult passage of hard, dry stools (Brown and Edwards, 2011). Constipation is a common health issue in the community-dwelling population. According to an epidemiological study by Peppas and others (2008), the incidence of constipation in the Australasian population is between 6% and 30%. The incidence in hospitalised patients is likely to be much higher.

Constipation is a symptom that should not be ignored, as it may indicate a serious underlying disease or motility disorder of the GI tract (Apau, 2010). When intestinal motility slows, the faecal mass becomes exposed for an increased time to the intestinal walls and most of the faecal water content is absorbed. Little water is left to soften and lubricate stools. Passage of a dry, hard stool may cause rectal pain. An important consideration when assessing a person’s bowel elimination pattern is that defecation patterns vary between individuals. Not every adult has a daily bowel movement. A bowel movement only every 3 or more days may be considered normal, if it is not associated with pain, passage of hard faeces or bloating.

The causes of constipation are multifactorial. Primary causes include insufficient dietary fibre, lack of exercise and deferring defecation. Secondary causes include anal and colonic disorders such as anal stricture and colon cancer; neurological disorders such as spinal cord injury or damage to the sacral nerves; metabolic disorders such as hypothyroidism; and laxative abuse (Apau, 2010). Common medications are also a significant cause of constipation. These include antacids, iron supplements, anticholinergics, antidepressants, calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), diuretics and narcotic analgesics (Toglia, 2009) (Table 37-2). Prolonged constipation can have significant adverse health effects, including the development of haemorrhoids, faecal impaction, urinary incontinence (due to direct pressure of a faecal mass on the bladder), urinary retention and urinary tract infection (due to incomplete bladder emptying) (Kyle and Prynn, 2007).

Impaction

Faecal impaction results from unrelieved constipation. It is a collection of hardened faeces, wedged in the rectum, which cannot be expelled. In cases of severe impaction, the mass can extend up into the sigmoid colon. Frail older adults, who are debilitated or confused (e.g. people with dementia), or people who are unconscious or have an intellectual disability are most at risk for impaction. They are too frail, unaware of the need to defecate or may be dehydrated so that the stool becomes too hard and dry to pass.

BOX 37-1 COMMON CAUSES OF CONSTIPATION

• Irregular bowel habits and ignoring the urge to defecate

• Slowed peristalsis, loss of abdominal muscle elasticity and reduced sense of rectal fullness

• Reduced physical or cognitive functioning (including dementia)

An obvious sign of impaction is the inability to pass a stool for several days, despite a repeated urge to defecate. When a continuous oozing of diarrhoeal stool develops, impaction should be suspected. The liquid portion of faeces located higher in the colon seeps around the impacted mass. Loss of appetite (anorexia), abdominal distension and cramping, and rectal pain may accompany the condition.

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON OLDER ADULTS

Constipation is a common health issue in the community. Older adults are prone to developing constipation because of the interaction of a number of factors:

• Physiological—lack of dietary fibre intake, poor fluid intake, inappropriate dietary habits, poor dentition

• Functional—decrease in mobility due to chronic joint disease, increase in sedentary lifestyle, ignoring the urge to defecate, poor lifelong bowel habits

• Mechanical—any condition that slows peristalsis or obstructs the colon and rectum; lack of sufficient abdominal muscle tone

• Psychological—depression, confusion, stress, avoidance of defecation (e.g. in a 4-bed ward), recent environmental change

• Systemic—conditions that alter the physiology of the gastrointestinal tract

• Pharmacological—numerous medications that slow peristalsis, alter absorption or change the physiology of the gastrointestinal tract, e.g. antacids, opioid analgesics, antidepressants, sedatives, overuse of laxatives

Adapted from Ebersole P, Hess P 2012 Toward healthy aging, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea is an increase in the number of stools and the passage of liquid, unformed faeces. It is a symptom of disorders affecting digestion, absorption and secretion in the GI tract. Intestinal contents pass through the small and large intestines too quickly to allow the usual absorption of fluid and nutrients. Irritation within the colon can result in an increased mucus secretion. As a result, faeces become watery and the person may be unable to control the urge to defecate.

It is often difficult to assess diarrhoea in infants. An infant who is bottle-fed may have one firm stool every second day, whereas a breastfed baby may pass 5–8 small soft stools daily. Any sudden increase in the number of stools, any reduction in faecal consistency with an increase in fluid content and a tendency for faeces to be greenish may indicate the need for further assessment.

Excess loss of colonic fluid can result in serious fluid and electrolyte or acid–base imbalances. Infants and older adults are particularly susceptible to associated complications (see Chapter 39). Because repeated passage of diarrhoeal stools also exposes the skin of the perineum and buttocks to irritating intestinal contents, meticulous skin care is needed to prevent skin breakdown (see Chapter 34), and containment of faecal drainage is needed.

Diarrhoea can be acute or chronic and can be caused by many conditions (Table 37-3). The aims of treatment are to remove precipitating conditions and to slow peristalsis. Box 37-2 lists nursing interventions that can be used in the treatment of acute diarrhoea in a hospitalised patient.

TABLE 37-3 CONDITIONS AND INTERVENTIONS THAT CAUSE DIARRHOEA

| CONDITION/INTERVENTION | PHYSIOLOGICAL EFFECTS |

|---|---|

| Emotional stress (anxiety) | Increased intestinal motility |

| Colon disease (colitis, Crohn’s disease) | Inflammation and ulceration of intestinal walls, reduced absorption of fluids, increased intestinal motility |

| Food allergies | Reduced digestion of food elements |

| Food intolerance (greasy foods, coffee, alcohol, spicy foods) | Increased intestinal motility, increased mucus secretion in colon |

| Intestinal infection (streptococcal or staphylococcal enteritis) | Inflammation of intestinal mucosa, increased mucus secretion in colon |

| Laxatives (short term) | Increased intestinal motility |

| Medications | |

| Iron | Irritation of intestinal mucosa |

| Antibiotics | Superinfection allowing overgrowth of normal flora, inflammation and irritation of mucosa |

| Surgical alterations | |

| Gastrectomy | Loss of reservoir function of stomach, improper absorption because food is moved into duodenum too quickly |

| Colon resection | Reduced size of colon, reduced amount of absorptive surface |

| Tube feedings | Hyperosmolarity of some enteral solutions results in diarrhoea, because hyperosmolar fluids draw fluids into the gastrointestinal tract |

BOX 37-2 SUMMARY OF NURSING INTERVENTIONS FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE DIARRHOEA IN A HOSPITALISED PATIENT

• Reduce risk of spread of infective organism—use standard and transmission-based infection control precautions.

• Fluid replacement—provide measures to maintain, or restore, fluid status and electrolyte balance.

• Assessment—observe vital signs for systemic manifestations such as fever, leucocytosis, fluid volume deficits, electrolyte imbalances.

• Nutrition—consult dietitians and encourage foods that are nourishing and tempting, little and often.

• Skin care—maintain perianal skin integrity by cleansing area and drying well.

Adapted from Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare 2010 Australian guidelines for the prevention and control of infection in healthcare. Canberra, Australian Government; Hall V 2010 Acute uncomplicated diarrhoea management. Pract Nurs 21(3):118–22.

Incontinence

Faecal incontinence is the inability to control passage of faeces and flatus (gas) from the anus that is sufficient enough to become a social or hygienic problem (Abrams and others, 2009). It is a debilitating condition that is estimated to affect up to 10% of community-dwelling adults, with the incidence rising to 40% in the nursing-home population (Bliss and others, 2006; Smith, 2010). Physical conditions that impair anal sphincter function or control can cause incontinence; for example, damage to the anal sphincter during childbirth, pelvic floor dysfunction and neurological disorders such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and spinal cord injury (Toglia, 2009). Conditions that create frequent, loose, large-volume, watery stools also predispose to incontinence; for example, inflammatory bowel disease.

Consider for a moment how you would feel if you were not confident you could get to the toilet on time. Incontinence significantly affects a person’s quality of life and can lead to depression, anxiety and a decrease in general wellbeing (Chien and Bradway, 2010). The embarrassment of soiling clothes can lead to social isolation.

Flatulence

As gas accumulates in the lumen of the intestines, the bowel wall stretches and distends (flatulence). This is a common cause of abdominal fullness, pain and cramping. Normally, intestinal gas escapes through the mouth (burping) or the anus (passing of flatus). However, if there is a reduction in intestinal motility resulting from opiates, general anaesthetics, abdominal surgery or immobilisation, flatulence can become severe enough to cause abdominal distension and severe sharp pain.

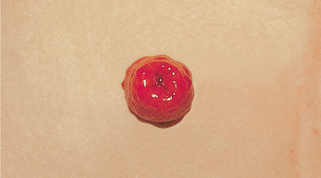

Haemorrhoids

Haemorrhoids are dilated engorged veins in the lining of the rectum. They are either external or internal. External haemorrhoids are clearly visible on the outside of the anus as protrusions of skin. If the underlying vein is hardened, there can be a purplish discolouration (thrombosis). This causes increased pain and the haemorrhoid may need to be excised. Internal haemorrhoids have an outer mucous membrane. Increased venous pressure from straining at defecation, pregnancy, obesity, heart failure and chronic liver disease can cause haemorrhoids.

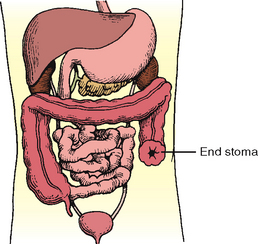

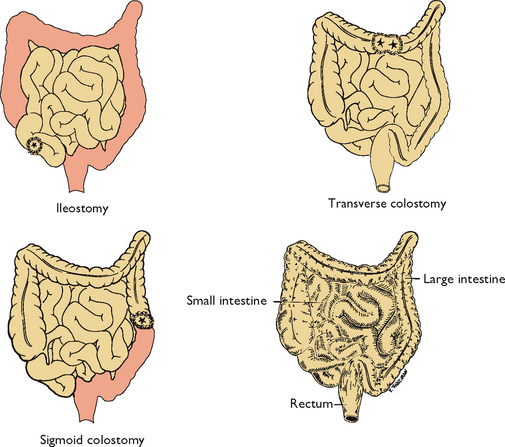

Bowel diversions

Certain diseases cause conditions that prevent normal passage of faeces through the rectum. This creates the need for a temporary or permanent artificial opening (stoma) in the abdominal wall. Surgical openings (ostomies) are most commonly formed in the ileum (ileostomy) or colon (colostomy) (Figure 37-4). Ends of the intestines are brought through a surgical opening in the abdominal wall to create the stoma (Burch, 2011). A stoma can be permanent or temporary. Depending on the type of surgical procedure done, the patient either will have no control over when the faecal material exits the stoma (incontinent ostomy) or will have control (continent ostomy). For incontinent ostomies, the stoma is covered with a pouch (appliance), what patients refer to as ‘a bag’, to collect faecal material.

FIGURE 37-4 Normal intestines (bottom right) and three types of ostomy. Shaded areas indicate excised tissue.

INCONTINENT OSTOMIES

The location of the ostomy determines the consistency of stool. An ileostomy bypasses the entire large intestine. As a result, stools are frequent and liquid. The same is true for a colostomy of the ascending colon. A colostomy of the transverse colon generally results in a more solid, formed stool. The sigmoid colostomy emits near-normal stools. The location of a colostomy is determined by the patient’s medical problem and general condition. There are three types of colostomy construction: loop colostomy, end colostomy and double-barrel colostomy.

LOOP COLOSTOMY

A loop colostomy is usually performed in a medical emergency when closure of the colostomy is anticipated. These are usually temporary large stomas constructed in the transverse colon (Figure 37-5). The surgeon pulls a loop of bowel onto the abdomen. An external supporting device such as a plastic rod, bridge or rubber catheter is temporarily placed under the bowel loop to keep it from slipping back. The surgeon then opens the bowel and sutures it to the skin of the abdomen. A communicating wall remains between the proximal and distal bowel. The loop ostomy has two openings through the stoma. The proximal end drains stools, whereas the distal portion drains mucus. Within 7–10 days the external supporting device is removed.

END COLOSTOMY

The end colostomy consists of one stoma formed from the proximal end of the bowel with the distal portion of the GI tract either removed or sewn closed (called a Hartmann’s pouch) and left in the abdominal cavity. For many patients, end colostomies are a result of surgical treatment of colorectal cancer. In such cases the rectum might also be removed. Patients with diverticulitis who are treated surgically often have a temporary end colostomy with a Hartmann’s pouch (Figure 37-6).

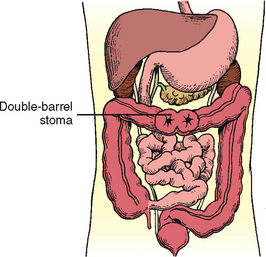

DOUBLE-BARREL COLOSTOMY

Unlike the loop colostomy, the bowel is surgically severed in a double-barrel colostomy, and the two ends are brought out onto the abdomen (Figure 37-7). The double-barrel colostomy consists of two distinct stomas: the proximal functioning stoma and the distal non-functioning stoma.

FIGURE 37-7 Double-barrel colostomy. Both ends of transected colon are brought out to skin.

Modified from Phillips N 2007 Berry & Kohn’s Operating room technique. St Louis, Mosby.

Ostomies that emit frequent liquid stools (e.g. ileostomy) create a management challenge. A pouch must always be worn. Control of defecation cannot be achieved because of a continuous oozing of liquid stool. The pouch must be emptied, washed and, if a two-piece ostomy system is being used, even replaced throughout the day. Skin care is vital to prevent exposure to faecal irritants.

A colostomy in the transverse or sigmoid colon needs less-frequent emptying of the pouch. Although some patients might choose to not wear a pouch at all times, most patients with sigmoid colostomies wear a pouch at all times even though bowel movements may occur only once or twice daily. Selected foods can be eaten at prescribed intervals so that bowel movements occur at a convenient time.

CONTINENT OSTOMIES

Certain types of surgery may provide continence for select colectomy patients. These continent ostomies are also called continent diversions or continent reservoirs. In a procedure called an ileoanal pull-through, the colon is removed and the ileum is anastomosed or connected to an intact anal sphincter. Not every colectomy patient is a candidate for this procedure. Selection criteria require close coordination between the patient and surgeon.

ILEOANAL RESERVOIR

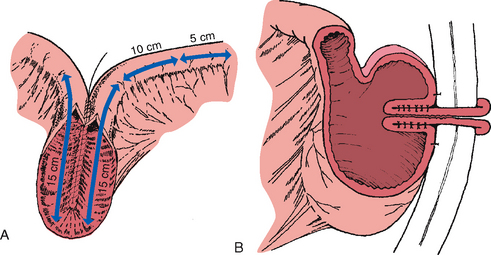

Another surgical procedure based on the ileoanal pull-through is the ileoanal reservoir (IAR). The ileoanal reservoir is also called a restorative proctocolectomy, ileal pouch–anal anastomosis, or pelvic pouch. In this procedure, the patient has no permanent external stoma and therefore does not need to wear an ostomy pouch. Patients have an internal pouch created from their ileum. These ileum pouches can be constructed in various configurations such as in a lateral, S, J or W shape. The end of the pouch is then sewn or anastomosed to the anus (Figure 37-8). The surgery is done in stages, 8–12 weeks apart, and the patient may have a temporary ostomy until the surgically created ileum pouch has healed. When healing has occurred and the patient has successfully learned Kegel exercises to strengthen the pelvic floor and sphincter muscles, the temporary ostomy is removed. The patient then has bowel movements, less frequently, from only the anal area. Nursing care for patients with an ileoanal reservoir should focus on emotional support, perianal skin care of washing carefully, drying and the use of a perineal pad if necessary, sphincter re-education and prompt recognition of complications. Information regarding self-care management should be available in verbal and written format (Brown and Edwards, 2011).

FIGURE 37-8 Ileoanal reservoirs (IARs). A, S-shaped configuration for IAR. Three 10 cm limbs of ileum are used, the antimesenteric surface of each limb opened and adjacent bowel walls anastomosed. B, J-shaped configuration for IAR. Distal ileum is aligned in J shape; the antimesenteric surface of J shape opened, and adjacent bowel walls anastomosed. Side-to-end anastomosis of bowel to dentate line is evident. C, Lateral or side-by-side ileoanal pouch configuration.

From Hampton BG, Bryant RA 1992 Ostomies and continent diversions: nursing management. St Louis, Mosby.

KOCK CONTINENT ILEOSTOMY

The Kock continent ileostomy is another type of continent ostomy. In this procedure an internal reservoir or pouch is created from a piece of the patient’s small intestine (Figure 37-9A). Part of the pouch is brought out onto the patient’s abdomen as an external stoma (Figure 37-9B). Unlike other ostomy stomas, the external stoma from a Kock continent ileostomy is usually very low on the patient’s abdomen; usually below the line of the patient’s underpants. At the end of the internal part of the pouch is a one-way nipple valve, which is how continence is accomplished (see Figure 37-9B). This valve allows faecal contents to drain from the pouch only when an external catheter is intermittently placed into the stoma. As faecal contents are eliminated from the Kock pouch only when intubated with the catheter, the patient, unlike other people with an ostomy, does not have to wear an ostomy pouch. Nursing care of patients with a Kock reservoir focuses on emotional support, teaching self-intubation technique, determining an intubation schedule, diet teaching and recognising complications.

FIGURE 37-9 Construction of Kock continent ileostomy—Kock pouch. A, Two 15 cm limbs are used to create pouch, and one 15 cm limb is used to fashion a nipple valve and stoma. B, Distal limb is intussuscepted into reservoir to create one-way valve and accomplish continence. Sutures or staples, or both, are placed to stabilise and maintain intussuscepted nipple. Anterior surface of reservoir is anchored to anterior peritoneal wall.

From Hampton BG, Bryant RA 1992 Ostomies and continent diversions: nursing management. St Louis, Mosby.

PSYCHOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

A stoma can cause serious body image changes, particularly if it is permanent. Changes to the person’s ability to complete daily tasks (including their usual work), changes to sexuality and sexual function (including erectile dysfunction in men), social isolation, changes to general wellbeing and perception of quality of life are all possible consequences of living with a bowel stoma (Boyles, 2010). An important factor in the person’s reaction to living with a stoma is the character of faecal secretions and the ability to control them. Foul odours, the fear of spillage or leakage of liquid stools and inability to regulate bowel movement can severely affect the person’s quality of life.

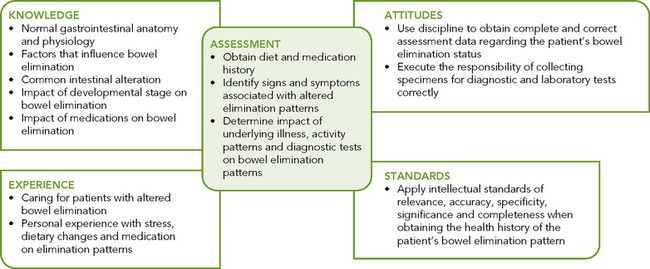

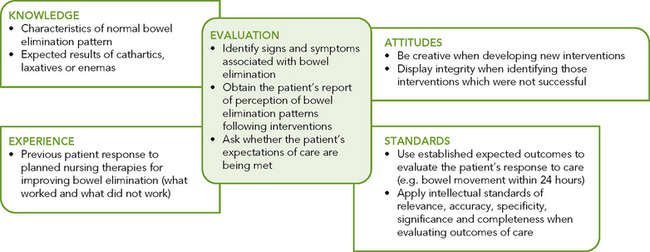

Critical thinking synthesis

Successful clinical decision making requires a synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from patients, critical thinking attitudes and intellectual and professional standards. Assessment of a person for risk factors or actual bowel elimination problems requires specific knowledge and sensitivity in approaching health issues that the person may find difficult to discuss (see Figure 37-10).

NURSING PROCESS AND BOWEL ELIMINATION

ASSESSMENT

To assess bowel elimination patterns and determine the aetiology of symptoms requires a focused nursing history, physical assessment including abdominal examination, specimen inspection and skin assessment.

Nursing history

The focused nursing history provides a review of the person’s usual bowel pattern and habits. Identifying normal and abnormal patterns, habits and the person’s perception of normal and abnormal bowel function enables identification of possible problems and gives direction to the physical examination. Much of the nursing history can be organised around the factors that affect elimination:

• Determination of the person presenting’s concern. It is important to acknowledge the person’s perception of their bowel elimination problem and how this affects their quality of life.

• Determination of the usual bowel elimination pattern. Frequency and time of day are included. Accurate assessment of the current bowel elimination pattern can be enhanced by having the person or caregiver complete a ‘bowel diary’. To improve accuracy, the person completing the diary must understand what information must be recorded. Normally a bowel diary would be kept for three 24-hour periods so that the person’s normal bowel elimination patterns can be determined.

• Description of any recent change in elimination pattern. This information is perhaps the most significant, because elimination patterns are variable and the patient can best detect change. For example, a change in character or frequency of bowel elimination, history of recent overseas travel, eating take-away food, etc. Ask the person to describe any change in detail.

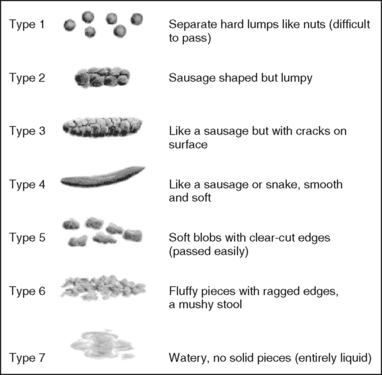

• Bowel symptoms and description of usual characteristics of stool. Ask the person to describe any abnormal symptoms they are experiencing. For example, presence of blood or mucus in the stool, presence of pain before, during or after defecation, sense of incomplete emptying, or anal symptoms such as itchiness or pain. Ask the person to describe their usual stool using the Bristol Stool Chart (Lewis and Heaton, 1997). This chart is a validated tool for describing stool appearance. It has a 7-point scale (see Figure 37-11). Stool types 3 and 4 are considered to be the most usual or normal consistency (Kyle and Prynn, 2007).

• Routines followed to promote normal elimination. Examples are drinking hot liquids, using laxatives, eating specific foods or taking time to defecate during a certain part of the day.

• Usual diet. The most accurate way of collecting this information is for the person to complete a food diary. If this is not possible, ask the person to recall their food intake over the last 24-hour period. Take note of types of food consumed (fresh or processed), the amount of dietary fibre in the diet and the variety of foods eaten. The information may indicate the need for referral to a dietitian for specific dietary advice.

• Description of daily fluid intake. This includes the type and amount of fluid. The person might have to estimate the amount using common household measurements.

• Exercise. Describe the type and amount of daily exercise, as lack of exercise is linked to constipation.

• Medication history. Question the person regarding their usual medications (such as laxatives, antacids, iron supplements and analgesics) that might alter defecation or faecal characteristics.

• Past health history. Personal or family history of health issues affecting the GI tract; for example abdominal surgery, neurological disease, family history of bowel cancer. If the patient has an ostomy, ask them about the frequency of faecal drainage, character of faeces, appearance and condition of the stoma (colour, swelling and irritation), type of appliance used and methods used to maintain the ostomy’s function.

• Mobility and dexterity—ability to care for self. The patient’s mobility and dexterity need to be evaluated to determine whether the patient needs assistive devices or personnel. You need to make a judgment about the need for questioning in this area based on your observation of the person; for example, on assistance needed to get to the toilet, undressing/redressing, hygiene, and use of toileting aids (commode chairs, raised toilet seats, etc). Where patients live may affect their toileting habits. If the patient is sharing living quarters, how many bathrooms are there? Do patients have their own bathroom, or do they need to share and thus adjust the time they use the bathroom to accommodate others?

• Other self-care practices. Health screening related to faecal occult blood testing (FOBT), rectal examination and colonoscopy (where there is a risk of bowel cancer). Use of continence pads or pants if the person has a bowel control problem.

FIGURE 37-11 Bristol Stool Chart

developed by KW Heaton and SJ Lewis at the University of Bristol, England.

Research abstract

Constipation is a common symptom for people of all ages. Constipation is a major health concern for many hospitalised patients, especially older, immobile patients; those with neurological impairment; and patients with multiple healthcare needs. The causes of constipation are multifactorial and influenced by physical, psychological, physiological, emotional and environmental factors. This paper defines constipation and describes the symptoms and types and risk factors for constipation. It also describes assessment of constipation using the Norgine Risk Assessment for Constipation.

Findings

In this paper Kyle defines constipation, and raises the point that patients tend to define constipation on the basis of their symptoms while healthcare professionals define constipation in terms of frequency and stool consistency. This difference in emphasis, she argues, is likely to contribute to the problem not being attended to until it has become a significant problem.

Constipation presents as two main syndromes: slow colonic transit (slow transit of stool through the bowel to the rectum); and evacuation difficulties (stool not able to be evacuated from the rectum). Often symptoms are from a combination of both types.

The assessment of constipation must take into account all possible causes and aims to establish a detailed symptom and risk profile. In addition to history, there are a number of tools that can be used in assessment including the Bristol Stool Chart, food and fluid diaries and bowel diaries.

Kyle also emphasises the importance of the physical assessment, including functional assessment, posture, gait and mobility; abdominal examination; digital rectal examination including the assessment of anal sphincter tone; and general skin condition.

Kyle advocates the use of the Norgine risk assessment tool (developed by Kyle and others, 2007). The validity and reliability of this tool has been tested and it has been found to have good inter-rater reliability (95% confidence interval). The tool requires a series of questions to be answered when assessing the patient, which are scored. The higher the score, the greater the risk the patient has of developing constipation. Kyle makes the point that the tool is still in development and encourages use, further development and evaluation.

Evidence-based practice

• Accurate assessment of the patient requires a comprehensive knowledge of the different types of constipation and risk factors.

• Clear identification of risk factors will assist in preventing constipation in high-risk patients.

• The Norgine risk assessment tool provides a valid tool for use in all clinical settings in determining patient risk.

• CRITICAL THINKING

A 17-year-old male with a history of good health and regular exercise is seen by the school nurse. He complains of increasing diarrhoea and abdominal cramping. He states that on rare occasions he has noticed blood on the toilet paper he has used. What additional pieces of assessment data do you need?

Physical assessment

Focused physical examination (see Chapter 27) of body systems and functions related to elimination problems should be carried out. You will need to make a judgment about the specific areas to include in your examination, which may include assessment of the mouth, abdomen, perianal area and rectum.

Mouth

An assessment includes inspection of the patient’s teeth, tongue and gums. Poor dentition or poorly fitting dentures influence the ability to chew (see Chapter 34). Sores and oral Candida (thrush) in the mouth can make eating not only difficult but painful.

Abdomen

Inspect all four abdominal quadrants for contour, shape, symmetry and skin colour. Inspection also includes noting masses, scars, stomas and lesions. Abdominal distension appears as an overall outward protuberance of the abdomen. Intestinal gas, large tumours, or fluid in the peritoneal cavity may cause distension. The skin of a distended abdomen appears taut, as if stretched.

Auscultation of the abdomen with the stethoscope is performed to assess bowel sounds in each quadrant (see Chapter 27). Auscultation of the bowel sounds is not done in the usual order of physical assessment, but is done prior to palpation. Normal bowel sounds occur every 5–15 seconds and last 1 second to several seconds. While auscultating, note the character and frequency of bowel sounds.

• An increase in pitch or a tinkling sound may be heard with abdominal distension.

• Absent or hypoactive sounds (< 5 sounds per minute) occur with paralytic ileus, such as after abdominal surgery.

• High-pitched and hyperactive bowel sounds (35 or more sounds per minute) occur with small-intestine obstruction and inflammatory disorders.

Palpation of the abdomen is performed to determine distension (a drum-like tightness), areas of tenderness or the presence of masses (see Chapter 27). It is important for the person to relax. Tensing abdominal muscles interferes with palpating underlying organs or masses. If the examination reveals significant tenderness in any area of the abdomen, note the location of the tenderness and do not progress with further palpation or percussion. Refer the person to a medical practitioner for further assessment, as the pain/tenderness may indicate serious underlying pathology such as acute appendicitis or inflammation of the bowel. A person with severe constipation or faecal impaction may have faecal matter in the sigmoid or descending colon which you may be able to palpate on the left lower abdominal region.

Percussion detects lesions, fluid or gas within the abdomen. Familiarity with the five percussion notes (see Chapter 27) also permits identification of underlying abdominal structures, for example a distended bladder. Gas or flatulence creates a tympanic note. Masses, tumours and fluid are dull to percussion.

Perianal area

Inspect the area around the anus for lesions, discolouration, inflammation and haemorrhoids. Abnormalities should be carefully recorded (see Chapter 27).

Laboratory tests

Laboratory and diagnostic examinations yield useful information concerning elimination problems. Laboratory analysis of faecal contents can detect pathological conditions such as tumours, GI haemorrhage, infection and parasites.

FAECAL SPECIMENS

Ensure that specimens are accurately obtained, properly labelled in appropriate containers and transported to the laboratory on time. Institutions provide special containers for faecal specimens. Some tests require specimens to be placed in chemical preservatives.

Aseptic technique should be used during collection of stool specimens (see Chapter 29). Because about 25% of the solid portion of a stool is bacteria from the colon, you must wear disposable gloves when handling specimens.

Hand hygiene is necessary for anyone who might come in contact with the specimen. Often the patient can obtain the specimen if properly instructed. Explain that faeces cannot be mixed with urine or water. For this reason the patient must defecate into a clean, dry bed pan or special container placed under the toilet seat.

Tests performed by the laboratory for occult (microscopic) blood in the stool and stool cultures require only a small sample; collect about 2 cm of formed stool or 15–30 mL of liquid diarrhoeal stool. Tests for measuring the output of faecal fat require a 3- to 5-day collection of stool. All faecal material must be saved throughout the test period.

After obtaining a specimen, label and tightly seal the container and complete the laboratory requisition forms. Then record the specimen collection in the patient’s medical record. It is important to avoid delays in sending specimens to the laboratory. Some tests, such as measurement for ova and parasites, require the stool to be warm; this is called a ‘hot’ specimen. When stool specimens are allowed to stand at room temperature, bacteriological changes that alter test results can occur.

FAECAL OCCULT BLOOD TEST

The FOBT is a common laboratory test which measures microscopic amounts of blood in faeces. There are two main types of tests for FOB: guaiac and immunochemical. Immunochemical techniques are considered to be more reliable, as their accuracy is not influenced by diet and the use of certain medications. The FOBT is useful as a diagnostic screening test for colon cancer. The Australian Federal Government funds a National Bowel Screening Program aimed at detecting bowel cancer early so that it can be effectively treated. The New Zealand Ministry of Health has a similar bowel screening program for New Zealanders. See Box 37-3.

BOX 37-3 SCREENING FOR COLORECTAL CANCER

SCREENING TESTS

• Faecal occult blood test (FOBT)—the Australian National Bowel Screening Program screens at ages 50, 55 and 65 years. The Cancer Council Australia recommends screening every two years for people over 50 years of age. New Zealand is currently (2011–2013) carrying out a pilot to test whether bowel screening should be introduced nationally.

• Colonoscopy is undertaken every 1–3 years for people at high risk or who have had a FOBT.

Cancer Council Australia 2008 Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer. Sydney, Cancer Council Australia. Online. Available at www.cancer.org.au/File/HealthProfessionals/ClinicalpracticeguidelinesJuly2008.pdf; National Bowel Cancer Screening Program 2012 About the program. Canberra, Department of Health and Ageing. Online, Available at www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/Content/bowel-about.

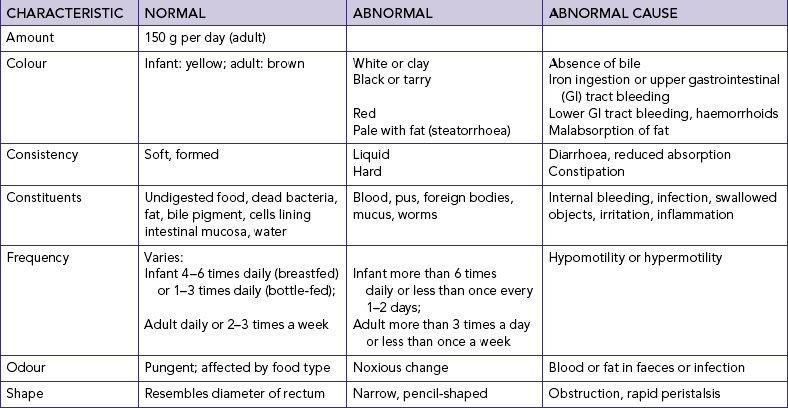

Faecal characteristics

Inspection of faecal characteristics (Table 37-4) reveals information about the nature of elimination alterations. Several factors can influence each characteristic. A key to assessment is determining whether there have been any recent changes in bowel elimination patterns and the characteristics of the faeces.

Diagnostic examinations

A patient may have a diagnostic test as an outpatient or inpatient. Viewing of GI structures may be by direct or indirect approach. Many facilities use conscious sedation during these procedures. Midazolam, a sedative-antianxiety agent, may be used, possibly augmented with a narcotic analgesic along with a local anaesthetic spray to help overcome gagging (Bryant and Knights, 2010). It is essential to understand the safety precautions involved concerning the use of this form of anaesthesia. Most institutions require nurses to have specialised skills in anaesthetic care nursing to care for such patients. Resuscitation equipment must be present at the bedside, and the patient must be monitored continuously with pulse oximetry.

DIRECT VIEWING

Instruments introduced through the mouth (upper GI viewing, or UGI) or the rectum (lower GI viewing) allow the medical practitioner to inspect the integrity of mucosa, blood vessels and organ parts. A colonoscopy is usually the test of choice; this uses a fibre-optic endoscope with a lens viewer, a long flexible tube and a light source at the end. It allows viewing of structures at the tip of the tube and insertion of special instruments for biopsy. Proctoscopes and sigmoidoscopes are rigid, tube-shaped instruments with attached light sources; the proctoscope looks like a speculum with a light. These instruments are less flexible than fibre-optic scopes and more capable of causing discomfort.

UGI endoscopy or gastroscopy allows viewing of the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum. The doctor inspects for tumours, vascular changes, mucosal inflammation, ulcers, hernias and obstructions. A gastroscope enables the doctor to remove tissue specimens (biopsy), remove abnormal tissue growth (e.g. polyps) and coagulate sources of bleeding. Lower GI examinations require bowel preparation for several days prior to the procedure. The person has a restricted, low-fibre diet for several days and then clear fluids on the day prior to the procedure. They are also required to take a strong stimulant laxative (e.g. ColonLYTELY) the day prior to the procedure. This is taken orally, usually 1 litre of fluid per hour for 2 hours. It has a strong osmotic effect in the bowel and may cause abdominal distension and cramping. The person should be advised to stay close to the toilet as it will result in high volumes of watery diarrhoea within 30 minutes to 3 hours following ingestion (Tiziani, 2010).

Nursing implications before diagnostic procedures concerning the GI system include the following:

• Record baseline observations including oxygen saturation (SpO2).

• Check that the patient has signed an informed consent form after the steps of the procedure have been explained to them.

• Check that the patient has performed the necessary bowel preparations.

• Check that the patient has not had anything to eat or drink for the required period of time prior to the procedure (as instructed by the medical practitioner).

• If conscious sedation is used, explain to the patient that they will have an intravenous cannula inserted prior to the procedure. The sedation will make them very sleepy, but they may hear voices of the staff involved in the procedure. They will recover quickly following the procedure.

For procedures involving the upper GI tract:

• If conscious sedation is not used, explain that the patient may feel fullness in the throat and a sense of gagging during the test.

• Explain that the patient will be unable to speak as the endoscope enters the oesophagus.

For procedures involving the lower GI tract:

• During the test, air is used to distend the bowel for better viewing; explain that the patient may have ‘wind pains’ after the procedure.

• For upper GI procedures—instruct the patient to avoid eating or drinking until the gag reflex returns (2–4 hours). To check for the gag reflex, the nurse places a tongue blade at the back of the patient’s tongue. Hoarseness and a sore throat are normal for several days; cool fluids and Normal saline gargling relieve soreness. The person should not drive a car or operate machinery for 12 hours after the procedure when conscious sedation is used.

• For lower GI procedures—the nurse observes for bleeding, fever, abdominal pain and blood in the stool. The person should not drive a car or operate machinery for 12 hours after the procedure when conscious sedation is used.

INDIRECT VIEWING

When direct viewing is impossible (as with deeper GI structures), the doctor relies on indirect X-ray examination. The patient ingests a contrast medium or has the medium given as an enema. One of the most common media is barium, a white, chalky, radio-opaque substance that the patient drinks like a milkshake. It is used in upper GI studies and barium enemas. Contrast media usually contain a flavouring agent to improve the taste.

The upper GI study is an X-ray study of an ingested contrast medium that allows the doctor to view the lower oesophagus, stomach and duodenum. The doctor notes ulcerations, inflammation, tumours and anatomical malposition of organs. The patency of organs and the pyloric valve are also observed. Nursing implications before the test include the following:

• Signed an informed consent form—explain the steps of the procedure to the patient, including that the test might take several hours and requires frequent position changes; explain that discomfort is minimal except for lying on a hard examination table.

• Performed the necessary bowel preparations (if applicable).

• Not had anything to eat or drink for the required period of time prior to the procedure (as instructed by the medical practitioner).

• Been informed that the radio-opaque medium meglumine diatrizoate (Gastrografin) may have a chalky taste and that the patient can resume eating after the test.

Small-bowel follow-through (continuation of upper GI viewing) enables close examination of the small intestine. The flow of meglumine through the intestine may suggest motility problems. A barium enema enables indirect viewing of the lower colon to reveal location of tumours, polyps and diverticula as well as structural abnormalities such as rectovaginal prolapse.

Patient expectations

Patients expect the nurse to be able to answer all their questions regarding diagnostic tests and the preparation for those tests. Patients will be concerned about discomfort and exposure of their more personal areas. Fear of loss of control over bowel elimination is especially worrisome. Patients will need reassurance that their needs will be met and that the nurse will be supportive.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS

A nursing assessment of the patient’s bowel function may reveal data that indicates an actual or potential elimination problem or a problem resulting from elimination alterations (Box 37-4). Associated problems, such as body-image changes or skin breakdown, require interventions unrelated to bowel-function impairment. However, in some instances the nurse must direct as much attention to the elimination problem as to the associated problem.

The ability to identify the correct diagnosis depends not only on the thoroughness of the assessment but also on recognition of the defining characteristics and factors that can impair elimination (Box 37-5). The nurse determines the patient’s risk and institutes measures to ensure maintenance of normal bowel function.

BOX 37-5 SAMPLE NURSING DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

| ACUTE DIARRHOEA | |

| Possible nursing diagnosis | Diarrhoea related to infection, changes in diet or alteration in gastrointestinal functioning |

| ASSESSMENT | ACTIVITIES DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS |

|---|---|

| Have patients describe pain, cramping, or any associated factors. | Pain is colicky in nature and spasmodic. |

| Have patient describe onset of symptoms, relationship to diet, recent travel, etc. | |

| Auscultate bowel sounds. | Bowel sounds will be hyperactive and may be audible without a stethoscope. |

| Assess frequency of stools. | Frequency is an early indication of increased risk of fluid and electrolyte imbalance, which is further indicated by muscle cramps. |

| Assess hydration status. | |

| Evaluate perianal area for redness and irritation. | Frequent stools lead to breakdown of perianal tissues. |

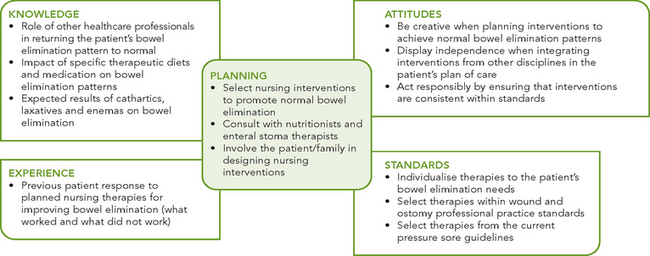

PLANNING

During the planning of care, the nurse synthesises information from multiple resources (Figure 37-12). Critical thinking ensures that the plan of care integrates knowledge about the patient and the clinical problem. The guidelines on urinary incontinence (see Chapter 38) should be used in care planning to protect the patient’s skin, promote continence and reduce the embarrassment associated with faecal incontinence. In addition, the use of current guidelines for the reduction of pressure injury helps in the development of care for patients with bowel incontinence (see Chapter 30). When the person requires surgical intervention, a care pathway may be used to coordinate the activities of the multidisciplinary healthcare team.

Goals and outcomes

The care plan establishes goals and outcomes by incorporating the patient’s elimination patterns or routines as much as possible. The person may need to be assisted to develop knowledge and new elimination patterns. Defecation patterns vary among individuals. For this reason, the nurse and patient must work together closely to plan effective interventions (see Sample nursing care plan).

The goals of care for patients with elimination problems include the following:

• understanding normal elimination

• attaining regular defecation patterns

• understanding and maintaining healthy fluid and food intake

Outcomes for a goal of attaining regular defecation patterns would be that the patient maintains soft, formed bowel motions every 1–3 days, identifies measures to prevent constipation, demonstrates regular bowel habits, increases fibre in the diet and increases fluid intake.

Setting priorities depends on the patient’s condition and perceived need. Some patients perceive that they are constipated if they do not open their bowels every day; others do not worry until they become uncomfortable.

Continuity of care

Patients who are discharged with unresolved bowel problems may require ongoing community care. Appropriate nursing services (e.g. Royal District Nursing Services) will be involved in teaching and monitoring the patient and meeting any ongoing needs. As well, the patient with alterations in bowel elimination may require intervention from many members of the healthcare team—the general practitioner, pharmacist and physiotherapist can provide information, support, expertise and assistance. When patients have a disability or are debilitated by illness, it is necessary to include the family in the plan of care.

Certain tasks, such as assisting patients onto the bed pan or bedside commode, are appropriate to delegate to nursing assistants (for example a personal care worker or health assistant). It is, however, important to remind the assistant to report any abnormal findings or difficulties with elimination.

Implementation

Success of the nursing interventions depends on improving patients’ and family members’ understanding of bowel elimination.

Health promotion

One of the most important concepts a nurse can teach regarding bowel elimination is to take time for defecation. To establish regular bowel elimination patterns, a person must know when the urge to defecate normally occurs. Advise the person to begin establishing a routine during a time when defecation is most likely to occur, usually an hour after a meal. If the person is restricted to bed or requires assistance in moving, the person should be offered a bed pan or assistance to reach the toilet.

Many people have established rituals for defecation. In a hospital or extended-care facilities, make certain that treatment routines do not interfere with these schedules. It is also important to provide privacy. When patients are forced to use a bed pan or share rooms with other people, pull the curtain around the area so that patients can relax, knowing that interruptions will not occur. The call light should always be placed within a patient’s reach. Bathroom doors should be closed, although you may need to stand close in case the patient needs assistance.

BOWEL ELIMINATION ALTERATIONS

ASSESSMENT*

Chris White (a registered nurse working in a rehabilitation centre) is assessing Mr John Moore on admission to the centre from an acute care hospital following a right total hip replacement 4 days ago. Mr Moore is 75 years old and has a history of osteoarthritis for approximately 15 years. This has caused pain and reduced movement in both hips and knees. He had his left hip replaced 18 months ago. He has no other health problems and his only regular medication prior to surgery was ‘Panadol osteo’. He was taking 2 tablets three times a day. He has progressed well following surgery and is keen to be involved in a rehabilitation program. The wound is healing well and has no signs of redness or swelling. Mr Moore is progressing well with increasing his mobility. His main health concern relates to bowel elimination. On this issue, the assessment revealed the following data:

• Normally has one soft bowel movement per day. Experienced constipation following previous hip replacement surgery.

• Has a poor appetite since the surgery, eating only small amounts. Drinking approximately 1500 mL of water and cups of tea per day.

• Feels bloated, feels like he needs to have his bowels opened but can’t. Last bowel movement 4 days ago.

• Had patient-controlled analgesia of morphine for 24 hours postoperatively and then Oxynorm for pain.

• Abdominal examination: slightly convex shape to abdomen, bowel sounds decreased in all four quadrants. Tender on palpation, especially in left lower quadrant.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS: Constipation related to opiate-containing pain medication, change of diet and mobility.

PLANNING

| GOALS | EXPECTED OUTCOMES |

|---|---|

*Defining characteristics are shown in bold type.

PROMOTION OF NORMAL DEFECATION

To help patients evacuate bowel contents normally and without discomfort, a number of interventions can stimulate the defecation reflex, affect the character of faeces or increase peristalsis.

TOILETING POSITION

You might need to give assistance to patients who have difficulty getting onto a toilet because of muscular weakness and mobility problems. Regular toilets are often too low for people who are unable to lower themselves to a squatting position because of joint- or muscle-wasting diseases. Patients can purchase elevated toilet seats for the home. With such a seat, less effort is needed to sit or stand.

POSITIONING ON BED PAN

Patients restricted to bed must use bed pans for defecation. Women use bed pans to pass both urine and faeces, whereas men use bed pans only for defecation. Sitting on a bed pan can be extremely uncomfortable. You may need to assist the person to get positioned comfortably. Two types of bed pans are available (Figure 37-13). The regular bed pan, made of metal or hard plastic, has a curved smooth upper end and a sharp-edged lower end and is about 5 cm deep. A fracture or slipper pan, designed for patients with body or leg casts, has a shallow upper end about 1.3 cm deep. The upper end of the pan fits under the buttocks toward the sacrum, with the lower end just under the upper thighs. The pan should be high enough so that faeces enter the pan.

FIGURE 37-13 Types of bed pans. From left, regular bed pan and fracture or slipper pan.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of Nursing, 8 ed. St Louis, Mosby.

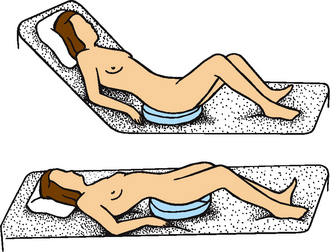

When positioning a patient, it is important to prevent muscle strain and discomfort. A patient should never be placed on a bed pan and then left with the bed flat unless activity restrictions demand this. If the bed is flat, the hips remain hyperextended. It may be necessary to have the bed flat when placing the patient on the bed pan. After the patient is on the pan, the nurse raises the head of the bed 30 degrees. Patients who have had abdominal surgery will be hesitant to exert strain on suture lines.

Figure 37-14 shows correct and incorrect positions on bed pans. The best method is to be sure the patient is positioned high in bed. Raise the patient’s head about 30 degrees, to prevent hyperextension of the back and to provide support to the upper torso, as the patient raises the hips by bending the knees and lifting the hips upwards. The use of an overbed handrail to assist the patient to pull themselves off the mattress may also be used. When handling a bed pan, always wear gloves.

FIGURE 37-14 Positions on a bed pan. Top, Proper position reduces patient’s back strain. Bottom, Improper positioning of patient.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of Nursing, 8 ed. St Louis, Mosby.

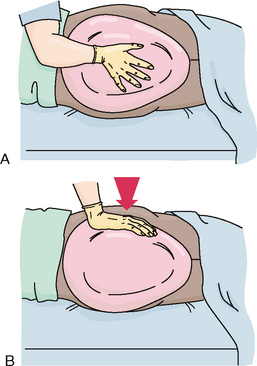

If the patient is immobile or it is unsafe to allow the patient to exert such effort, the patient can roll onto the bed pan by using the following steps:

1. Lower the head of the bed flat and help the patient roll onto one side, backside towards you.

2. You may need to apply talcum powder lightly to the back and buttocks to prevent skin from sticking to the pan.

3. Place the bed pan firmly against the buttocks, down into the mattress with the open rim towards the patient’s feet (Figure 37-15).

4. Keeping one hand against the bed pan, place the other around the patient’s upper hip. Ask the patient to roll back onto the pan, flat in bed. Do not push the pan under the patient.

5. With the patient positioned comfortably, raise the head of the bed 30 degrees.

6. Place a rolled towel or small pillow under the lumbar curve of the patient’s back for added comfort.

7. Ask the patient to bend the knees to assume a squatting position.

FIGURE 37-15 Positioning an immobilised patient on a bedpan. A, Place bed pan firmly against buttocks. B, Push buttocks down into mattress with open rim towards feet. Once bed pan is in this position, place one hand against pan and the other on the patient’s upper hip and ask the patient to roll onto the pan.