Abad C, Fearday A, Safdar N. Adverse effects of isolation in hospitalised patients: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2010;76:97–102.

Australian College of Operating Room Nurses (ACORN). Standards for perioperative nursing, including nursing roles, guidelines and position statements. Adelaide: ACORN, 2010.

Boyce JM, Pittet D. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings. Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. MMWR Recommendations and Report. 2002;51:1–45.

Cruickshank M, Ferguson J, eds. Reducing harm to patients from health care associated infection: the role of surveillance. Canberra: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2008. Online Available at www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2008/01/Reducing-Harm-to-Patient-Role-of-Surveillance1.pdf 10 Jun 2012.

Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA). Infection control guidelines for the prevention of transmission of infectious diseases in the healthcare setting. Canberra: DoHA, 2004.

Gomez C, Nomellini V, Faunce DE, et al. Innate immunity and aging. Exper Gerontol. 2008;43:718–728.

Gould DJ, Moralejo D, Drey N, et al. Interventions to improve hand hygiene compliance in patient care, Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(9). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005186.pub3. CD005186.

Graves N, Halton K, Robertus L. Costs of health care associated infection. Cruickshank M, Ferguson J, eds. Reducing harm to patients from health care associated infection: the role of surveillance. Canberra: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2008. Online Available at www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2008/01/Reducing-Harm-to-Patient-Role-of-Surveillance1.pdf, 2008 10 Jun 2012.

Grayson ML, Russo KR, Bellis K, et al, eds. Hand hygiene Australian manual. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2010. Online Available at www.hha.org.au/ForHealthcareWorkers/manual.aspx 20 Nov 2011.

Hand Hygiene Australia (HHA). National Hand Hygiene Initiative. Melbourne: HHA, 2012. Online Available at www.hha.org/home.aspx 12 Mar 2012.

Hand Hygiene New Zealand Ringa Horoia Aotearoa (HHNZ). Guidelines on hand hygiene for New Zealand hospitals. Auckland: HHNZ, 2009. Online Available at www.infectioncontrol.org.nz/handhygiene/resources.htm 6 Jun 2012.

Morgan DJ, Diekema DJ, Sepkowitz K, et al. Adverse outcomes associated with contact precautions: a review of the literature. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:85–93.

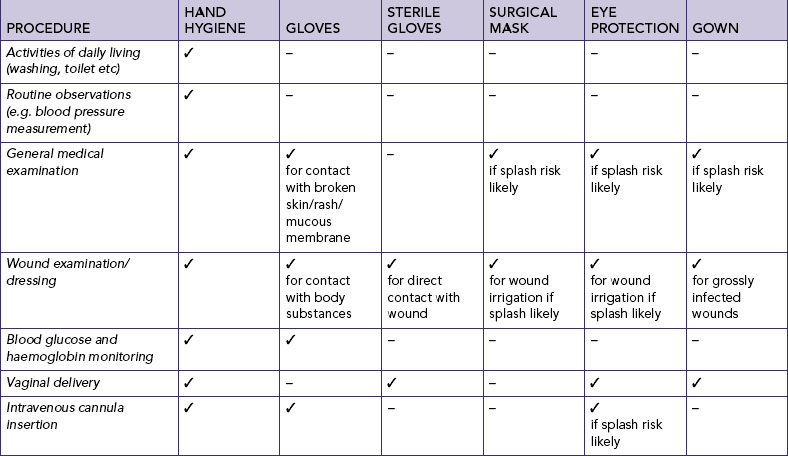

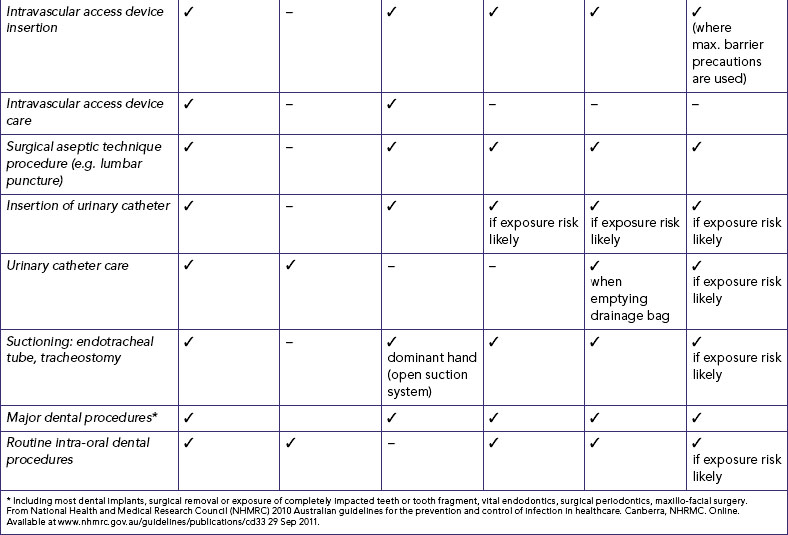

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Australian guidelines for the prevention and control of infection in healthcare. Canberra: NHMRC, 2010. Online Available at www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/cd33 29 Sep 2011.

Parker D, Callan L, Harwood J, et al. Nursing interventions to reduce the risk of catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Part 1: catheter selection. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36(1):23–34.

Rothrock J. Alexander’s Care of the patient in surgery, ed 13. Toronto: Mosby, 2007.

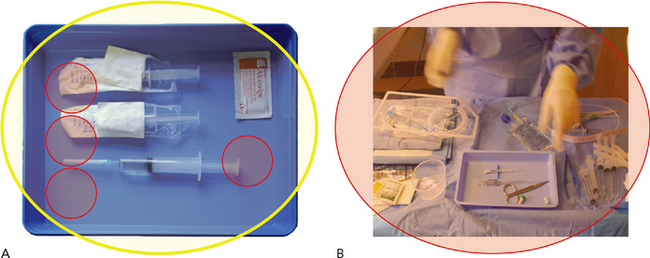

Rowley S, Clare S, Macqueen S, et al. ANTT v2: an updated practice framework for aseptic technique. Br J Nurs. 2010;19(5):S5–S11.

Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007. Online Available at www.cdc.gov/hicpac/2007IP/2007isolationPrecautions.html 6 Jun 2012.

Standards Australia. Cleaning, disinfection and sterilising reusable medical and surgical instruments and equipment, and maintenance of associated environments in health care facilities (AS/NZS 4187). Sydney: Standards Australia, 2003.

Standards New Zealand. Health and disability services (infection prevention and control) standards NZS 8134.3: 2008. Wellington: Standards New Zealand, 2008.

Stewardson A, Pittet D. Ignac Semmelweis—celebrating a flawed pioneer of patient safety. Lancet. 2011;378(9785):22–23.

Stone PW, Pogorzelska M, Kunches L, et al. Hospital staffing and healthcare-associated infections: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(7):937–944.

Struelens MJ. The epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance in hospital acquired infections: problems and possible solutions. Br Med J. 1998;317:652–654.

Tanner J, Parkinson H. (updated) Double gloving to reduce surgical cross-infection, Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003087.pub2. CD003087.

Weaver BA. Herpes zoster overview: natural history and incidence. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109(suppl 2):S2–S6.

Weller B, ed. Encyclopedic dictionary of nursing and health care. London: Ballière Tindall, 1997:81

Weiskopf D, Weinberger B, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. The aging of the immune system. Transplant Int. 2009;22:1041–1050.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care. Geneva: WHO, 2009. Online Available at www.who.int/gpsc/tools/en 12 Mar 2012.