Chapter 38 Urinary elimination

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Describe the physiological process of micturition.

• Identify factors that commonly influence urinary elimination.

• Compare and contrast common alterations in urinary elimination.

• Obtain a nursing history and perform a physical examination for a patient with urinary elimination problems.

• Describe characteristics of normal and abnormal urine.

• Describe the nursing implications of common diagnostic tests of the urinary system.

• Identify nursing diagnoses appropriate for patients with alterations in urinary elimination.

• Discuss nursing interventions to promote normal voiding.

• Discuss nursing interventions to promote continence.

• Discuss nursing interventions to reduce urinary tract infection.

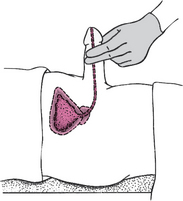

• Apply a urinary sheath/condom drainage device.

• Describe routine care and assessment of a person with an indwelling urinary catheter.

Normal elimination of waste products via the urine is a basic function most people take for granted. When the renal system fails to function properly, virtually all organ systems will eventually be affected. Similarly, problems with function of the lower urinary tract can significantly affect a person’s health and quality of life.

Scientific knowledge base

Urinary system

Urinary elimination depends on the function of the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. Kidneys remove wastes from the blood to form urine. Ureters transport urine from the kidneys to the bladder. The bladder holds urine until the urge to urinate develops. Urine leaves the body through the urethra. The kidneys and ureters form the upper urinary tract; the bladder and urethra form the lower urinary tract. All organs of the urinary system must be intact and functional for successful removal of urinary wastes (Figure 38-1).

FIGURE 38-1 Organs of the urinary system.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

Kidneys

The kidneys are reddish-brown, bean-shaped organs, one on either side of the vertebral column, posterior to the peritoneum and lying against the deep muscles of the back. The kidneys extend to the twelfth thoracic and third lumbar vertebrae. Normally, the left kidney is 1.5–2 cm higher than the right because of the anatomical position of the liver on the right side of the abdomen. Each kidney typically measures approximately 12 × 7 cm and weighs 120–150 g. Each kidney is covered by a tough capsule and surrounded by a cushion of fat.

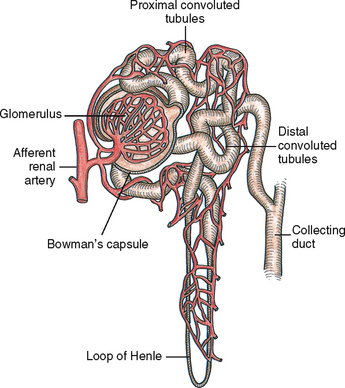

The kidneys filter the waste products of metabolism that collect in the blood. Blood reaches each kidney by a renal artery that branches from the abdominal aorta. The renal artery enters the kidney at the hilum. Approximately 20–25% of the cardiac output circulates each minute through the kidneys. The nephron, the functional unit of the kidney, forms the urine. The nephron is composed of the glomerulus, Bowman’s capsule, proximal convoluted tubule, loop of Henle, distal tubule and collecting duct (Figure 38-2).

Blood reaches nephrons through the afferent arterioles. A cluster of these blood vessels forms the capillary network of the glomerulus, which is the initial site of filtration of the blood and the beginning of urine formation. The glomerular capillaries are porous and permit filtration of water and substances such as glucose, amino acids, urea, creatinine and major electrolytes into the Bowman’s capsule. Large proteins and blood cells do not normally filter through the glomerulus. The presence of large proteins in the urine (proteinuria) is one sign of glomerular injury. The glomerulus filters approximately 125 mL of filtrate per minute. Initially the filtrate closely approximates the composition of blood plasma minus the large proteins.

Only a small amount of the glomerular filtrate is excreted as urine. About 99% of the filtrate is reabsorbed into the plasma, with the remaining 1% excreted as urine. Thus the kidneys play a key role in fluid and electrolyte balance (see Chapter 39). Although urine output does depend on intake, the normal adult 24-hour output of urine is about 1500–1600 mL. An output of less than 0.5 mL/kg per hour may indicate alterations in renal function.

The kidneys also produce several hormones vital to production of red blood cells (RBCs), blood pressure regulation and bone mineralisation. The kidneys are responsible for maintaining a normal RBC volume by producing erythropoietin. As a hormone, erythropoietin functions within the bone marrow to stimulate RBC production and maturation (McCance and Huether, 2010). Erythropoietin also prolongs the life of mature RBCs. People with chronic alterations in kidney function cannot produce sufficient quantities of this hormone and are, therefore, prone to anaemia.

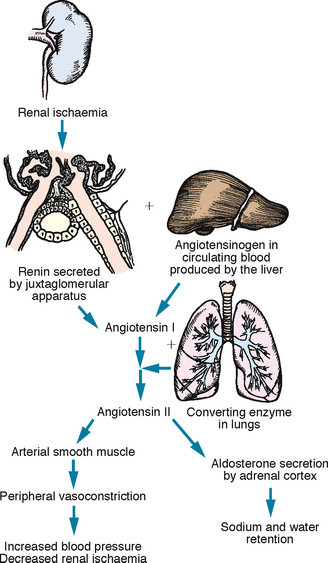

Renin is another hormone produced by the kidneys. Its major role is the regulation of the systemic circulation in times of renal ischaemia (decreased blood supply to the kidneys). Renin is released from juxtaglomerular cells (Figure 38-3).

FIGURE 38-3 Physiological effects of the renin–angiotensin mechanism.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

Renin functions as an enzyme to convert angiotensinogen (a plasma substance synthesised by the liver) into angiotensin I. As angiotensin I circulates through the lungs, it is converted to angiotensin II and angiotensin III. Angiotensin II exerts its effect on vascular smooth muscle to cause vasoconstriction and stimulates aldosterone release from the adrenal cortex. Aldosterone causes retention of water, which increases blood volume. Angiotensin III exerts similar effects, but to a lesser degree. The net effect of both these mechanisms is an increase in arterial blood pressure and renal blood flow (McCance and Huether, 2010).

The kidneys also play a role in calcium and phosphate regulation. They are responsible for producing a substance that converts vitamin D into its active form. People with chronic alterations in kidney function do not make sufficient amounts of the active vitamin D metabolite. They are therefore prone to developing renal bone disease resulting from the demineralisation of bone secondary to impaired intestinal calcium absorption unless the active form of vitamin D is supplied.

Ureters

Urine enters the renal pelvis from the collecting ducts. A ureter joins each renal pelvis to the urinary bladder. Ureters are tubular structures measuring 25–30 cm in length and 0.5 cm in diameter in the adult (Getliffe and Dolman, 2007). They extend retroperitoneally to enter the urinary bladder in the pelvic cavity at the ureterovesical junction. Urine draining from the ureters to the bladder is usually sterile.

Three layers of tissue form the wall of the ureter. The inner layer is a mucous membrane continuous with the lining of the renal pelvis and urinary bladder. The middle layer consists of smooth muscle fibres that transport urine through the ureters by peristaltic waves stimulated by distension with urine. An outer layer of fibrous connective tissue supports the ureters.

Peristaltic waves cause the urine to enter the bladder in spurts, rather than steadily. The ureters enter obliquely through the posterior bladder wall. This arrangement normally prevents the reflux of urine from the bladder into the ureters during the act of micturition by the compression of the ureter at the ureterovesical junction (the juncture of the ureters with the bladder). An obstruction within a ureter, such as a kidney stone (renal calculus), results in strong peristaltic waves that attempt to move the obstruction into the bladder. These strong peristaltic waves result in pain often referred to as renal colic.

Bladder

The urinary bladder is a hollow, distensible, muscular organ that is both a reservoir for urine and the organ of excretion. The size and shape of the bladder will vary depending on its state of fullness. When empty, the bladder lies in the pelvic cavity behind the symphysis pubis. In men the bladder lies against the anterior wall of the rectum and in women it rests against the anterior wall of the uterus and vagina.

The bladder expands as it becomes filled with urine. Pressure within the bladder is usually low, even when partly full, a factor that protects against reflux of urine back up the ureters into the kidneys. In a healthy adult, bladder capacity is approximately 500 mL and when the bladder is emptied there is no residual urine volume. Both men and women will void at 3- to 5-hour intervals during the day and usually do not need to void at night (Getliffe and Dolman, 2007). Keep in mind, however, that the habits of individuals will vary. When the bladder is full, it expands and extends above the symphysis pubis. A greatly distended bladder may reach the umbilicus. In a pregnant woman the developing fetus pushes against the bladder, causing a feeling of fullness and reducing the bladder’s capacity. This effect is more likely to occur in the first and third trimesters.

The trigone (a smooth, triangular area on the inner surface of the bladder) is at the base of the bladder. An opening exists at each of the trigone’s three angles. Two are for the ureters, and one is for the urethra. This area does not change shape very much during bladder filling and is very sensitive to stretch due to the large number of sensory nerve endings it contains (Getliffe and Dolman, 2007).

The wall of the bladder has four layers: an inner mucous coat, a submucous layer of connective tissue, a muscular layer and an outer serous coat. The muscular layer has bundles of muscle fibres that form the detrusor muscle. Parasympathetic nerve fibres stimulate the detrusor muscle during urination. In the male, the bladder neck provides a powerful sphincter mechanism. It also prevents retrograde ejaculation into the bladder during orgasm. The male internal urethral sphincter is made of a ring-like band of muscle which has a rich nerve supply. In the female the bladder neck is a far weaker structure than in the male (Getliffe and Dolman, 2007): the smooth muscle fibres extend longitudinally along the urethra; there are no circular muscles.

Urethra

Urine travels from the bladder through the urethra and passes outside the body through the urethral meatus. Normally, the turbulent flow of urine through the urethra washes it free of bacteria. Mucous membrane lines the urethra, and urethral glands secrete mucus into the urethral canal. The mucus is believed to be bacteriostatic and forms a mucous plug to prevent entrance of bacteria. Thick layers of smooth muscle surround the urethra. In addition, the urethra descends through a layer of skeletal muscle called the pelvic floor muscles. When these muscles are contracted, it is possible to prevent urine flow through the urethra (McCance and Huether, 2010).

In women the urethra is approximately 4–6.5 cm long. The external urethral sphincter, located about halfway down the urethra, permits voluntary flow of urine. The short length of the urethra predisposes women to ascending infection. Bacteria can easily enter the urethra from the perineal area. In men the urethra, which is both a urinary canal and a passageway for semen, is 18–22 cm long. The male urethra has three sections: the prostatic urethra, the membranous urethra and the cavernous or penile urethra. The prostate gland encircles the male urethra at the base of the bladder. In a female the urinary meatus (opening) is located between the labia minora, above the vagina and below the clitoris. In a male the meatus is located at the distal end of the penis.

Pelvic floor muscles

The bony pelvis forms the solid structure for the muscles and ligaments of the anterior, posterior and lateral pelvic walls and pelvic floor, which play an important role in supporting the position of the pelvic organs. The pelvic floor muscles include the coccygeus muscle and the levator ani and are referred to as the pelvic diaphragm. The anal canal, urethra and vagina pass through the pelvic diaphragm. The levator ani muscles support the pelvic organs and function as a sphincter for the anal canal and urethra (Jenkins and others, 2010).

The perineum is located inferior to the pelvic diaphragm. The perineum extends from the symphysis pubis anteriorly to the coccyx posteriorly and the ischial tuberosities laterally. The muscles of the perineum are in two layers: superficial and deep. The deep muscle layer of the perineum includes the external urethral sphincter and external anal sphincter which assist in maintaining urinary and faecal continence (Jenkins and others, 2010).

Micturition

Several brain structures influence bladder function, including the cerebral cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus and brainstem. Together they suppress contraction of the bladder’s detrusor muscle until a person decides to urinate (void). Once voiding (micturition) occurs, the response is a contraction of the bladder and coordinated relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles.

The desire to urinate can be sensed when the bladder contains approximately 150–200 mL of urine in an adult and 50–200 mL of urine in a child. As the volume increases, the bladder walls stretch, sending sensory impulses to the micturition centre in the sacral spinal cord. Parasympathetic impulses from the micturition centre stimulate the detrusor muscle to contract rhythmically. The internal urethral sphincter also relaxes so that urine may enter the urethra, although voiding does not yet occur. As the bladder contracts, nerve impulses travel up the spinal cord to the pons and cerebral cortex. A person is thus conscious of the need to urinate. Older children and adults can respond to or ignore this urge, thus making urination under voluntary control. If the person chooses not to void, the external urinary sphincter remains contracted, and the micturition reflex is inhibited. However, when a person is ready to void, the external sphincter relaxes, the micturition reflex stimulates the detrusor muscle to contract, and efficient emptying of the bladder occurs.

Nursing knowledge base

Factors affecting urinary elimination

Many factors influence the volume and quality of urine and a person’s ability to urinate. Some pathophysiological conditions may be acute and reversible (e.g. acute urinary tract infection), while others may be chronic and irreversible (e.g. slow, progressive development of renal dysfunction). There are changes that occur to the urinary system from normal growth and development; for example, development of continence in a child. There are also a number of changes that occur with normal ageing that predispose older people to problems related to their kidneys and bladder.

Growth and development

Infants and young children cannot effectively concentrate urine. Their urine thus appears light yellow or clear. In relation to their small body size, infants and children excrete large volumes of urine. For example, a 6-month-old infant who weighs 6–8 kg excretes 400–500 mL of urine daily.

A child cannot control micturition voluntarily until 18–24 months old. A child must be able to recognise the feeling of bladder fullness, to hold urine for 1–2 hours and to communicate the sense of needing to void to an adult. The young child needs parents’ understanding, patience and consistency. A child may not gain full control of micturition until age 4 or 5 years. Daytime control of micturition is easier to accomplish than night-time control and occurs earlier in the child’s development, usually by 2–3 years of age (see Working with diversity).

The adult normally voids 1500–1600 mL of urine daily. The kidney concentrates urine, normally producing amber-coloured urine. A person does not normally wake to void during sleep because of reduction of renal blood flow during rest and the kidneys’ ability to concentrate urine.

Changes in kidney and bladder function also occur with ageing. The glomerular filtration rate declines, but the kidneys’ ability to concentrate urine also declines. Thus the older adult often experiences nocturia (urination at night). The bladder loses its muscle tone and capacity to hold urine, resulting in increased urinary frequency. Because the bladder cannot contract as effectively, an older person often retains urine in the bladder after voiding (residual urine). Older men may also suffer from benign prostatic hypertrophy, which makes them prone to urinary retention and incontinence. These changes increase the risk for bacterial growth and development of urinary tract infections (UTIs). Another factor related to urinary elimination difficulties is constipation. Constipation and resulting bowel fullness may put external pressure on the bladder, reducing the effective capacity and causing frequency or even incontinence (see Chapter 37).

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON INFANTS AND CHILDREN

Bedwetting (nocturnal enuresis) is common in children and can occur until the teen years. According to the Continence Foundation of Australia, 1 in 5 Australian children wet their bed. There are three main causes of bedwetting:

• the inability to waken to the sensation of a full bladder at night

• overactivity of the bladder at night, causing loss of urine

• an abnormal amount of urine production occurring at night (nocturnal polyuria) when the child is asleep and unable to sense the fullness of the bladder.

Most children will gain night-time continence with time. The Continence Foundation of Australia suggests parents should seek assistance from a healthcare professional if a child who has been dry at night suddenly starts wetting at night; the episodes are frequent after 5 years of age; the wetting bothers the child or makes them angry or frustrated; the child is socially affected; or if the child states they want to become dry.

There are several approaches—bladder-training programs to increase the child’s functional bladder capacity; night alarms which wake the child when there is leakage, so they learn to wake when their bladder is full; and the use of some medications.

At home, parents can praise success and ignore failure; encourage the child to drink plenty of water; encourage the child to take responsibility for the problem (assist when changing sheets, etc); provide a high-fibre diet, as constipation can aggravate the problem; and avoid ‘toileting’ the child during the night—this does not improve bladder control.

Parents can be advised to seek help from:

• Continence Foundation of Australia, www.continence.org.au/index.php or helpline 1800 33 00 66

• New Zealand Continence Association, www.continence.org.nz or helpline 0800 650 659.

In the female, childbearing and/or the hormonal changes of menopause may cause changes that lead to urinary difficulties. During a pregnancy, urinary frequency is common and susceptibility to UTIs is increased. Temporary or permanent changes that result from repeated vaginal deliveries or hormonal changes may result in decreased pelvic floor muscle tone, leading to urgency and stress incontinence (see Chapter 22). The changes in the urethral mucosa associated with loss of oestrogen during and after menopause also contribute to increased susceptibility to infection (McCance and Huether, 2010).

Fluid balance

The kidneys maintain a sensitive balance between retention and excretion of fluids (see Chapter 39). If fluids and the concentration of electrolytes and solutes are in equilibrium, an increase in fluid intake causes an increase in urine production. Ingested fluids increase the body’s circulating plasma and thus increase the volume of glomerular filtrate and urine excreted.

This amount varies with food and fluid intake. The volume of urine formed at night is about half that formed during the day, because both intake and metabolism decline. This results in a reduction in the volume of renal blood flow. In a healthy person, the intake of water in food and fluids balances the output of water in urine, faeces and insensible losses in perspiration and respiration. An excessive output of urine is known as polyuria.

Ingestion of certain fluids directly affects urine production and excretion. Coffee, tea, cocoa and cola drinks that contain caffeine promote increased urine formation (diuresis). Alcohol inhibits the release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), resulting in increased water loss in urine. Foods that contain a high fluid content, such as fruits and vegetables, may also increase urine production.

Febrile conditions affect urine production. The patient who becomes diaphoretic loses a large amount of fluids through insensible water loss, which decreases urine production. However, the increased body metabolism associated with fever increases accumulation of body wastes. Although urine volume may be reduced, it is highly concentrated.

Changes to renal function

Disease processes that primarily affect renal function (changes in urine volume or quality) are generally categorised as prerenal, renal or postrenal in origin (Box 38-1). Prerenal alterations in urinary elimination decrease circulating blood flow to and through the kidneys, with subsequent decreased perfusion to renal tissue. In other words, the alterations are outside the urinary system. The decrease in renal perfusion leads to oliguria (diminished capacity to form urine) or, less commonly, anuria (inability to produce urine). Renal alterations result from factors that cause injury directly to the glomerulus or renal tubule, interfering with their normal filtering, reabsorptive and secretory functions. Postrenal alterations result from obstruction to the urinary collecting system anywhere from the calyces (drainage structures within the kidney) to the urethral meatus (i.e. outside the kidney but within the urinary system). Urine is formed by the urinary system but cannot be eliminated by normal means.

Changes to bladder function

Several diseases can affect the ability to void normally. Any lesion of peripheral nerves leading to the bladder causes loss of bladder tone, reduced sensation of bladder fullness and difficulty in controlling urination. For example, diabetes mellitus and multiple sclerosis cause neuropathic conditions that alter bladder function.

Illness and frailty

Reduced mobility or disability sometimes makes it difficult for a person to reach a toilet in time or to manage clothing or hygiene requirements. Rheumatoid arthritis, degenerative joint disease and Parkinson’s disease are examples of conditions that make it difficult to reach and use toilet facilities. A person with rheumatoid arthritis often cannot sit on or rise from a toilet without an elevated seat or handrails.

Any alteration in cognitive function can impair a person’s perception of the need to void or impair their ability to get themselves to the toilet and complete toileting activities. This is particularly relevant when a person who has dementia is admitted to an acute care hospital or moves from home to residential care. The change in environment can increase the person’s confusion and make episodes of urinary incontinence more likely. A major goal when caring for a person in this situation is to reduce the impact of the change in environment by close observation of the person’s responses, so that the nurse can anticipate the cues that the person needs to go to the toilet, reinforce the location of the toilet and provide frequent reassurance.

Psychological and environmental factors

Anxiety and emotional stress may cause a sense of urgency and increased frequency of urination. An anxious person may have the urge to void even after voiding only a few minutes earlier. Anxiety may also prevent a person from being able to urinate completely. Emotional tension makes it difficult to relax abdominal and pelvic floor muscles. If the external urethral sphincter is not completely relaxed, voiding may be incomplete and urine is retained in the bladder.

When people are hospitalised they are often reluctant to void in a shared ward environment or to use a bedpan or urinal. Where possible the person should be assisted to the toilet to void. Men may need assistance to stand to void. Staying close by and leaving the person with a call bell may encourage a more normal environment in which they feel comfortable for voiding to occur.

Surgical procedures

The stress of surgery initially triggers the general adaptation syndrome (see Chapter 42). The posterior pituitary gland releases an increased amount of ADH, which increases water reabsorption and reduces urine output. The surgical patient is often in an altered state of fluid balance before surgery due to the disease process or preoperative fasting, which aggravates the reduction in urine output. The stress response also elevates the level of aldosterone, resulting in reduction of urine output in an effort to maintain circulatory fluid volume.

Anaesthetic and narcotic analgesics may slow the glomerular filtration rate, reducing urine output. These pharmacological agents also impair sensory and motor impulses between the bladder, spinal cord and brain. Patients recovering from anaesthesia and deep analgesia are often unable to sense bladder fullness and are unable to initiate or inhibit micturition. Spinal anaesthetics, in particular, create the risk of urinary retention because of an inability to sense the need to void and a possible inability of the bladder muscles and sphincters to respond (Brown and Edwards, 2011).

Surgery of lower abdominal and pelvic structures can impair voiding because of local trauma to surrounding tissues. Pain can interfere with relaxation of pelvic floor and sphincter muscles and make voiding difficult or painful. After returning from surgery involving the ureters, bladder and urethra, patients routinely have an indwelling urinary catheter.

Medications

Diuretics prevent reabsorption of water and certain electrolytes to increase urine output. Urinary retention may be caused by use of anticholinergics (e.g. atropine), antihistamines (e.g. pseudoephedrine), antihypertensives (e.g. methyldopa) or beta-adrenergic blockers (e.g. propranolol). Some medications change the colour of urine. Amitriptyline causes a green or blue discolouration, while levodopa may discolour the urine to brown or black (Bryant and Knights, 2010). Cancer chemotherapy drugs may also colour the urine and be toxic to the kidneys or the bladder. Patients with alterations in kidney function require dosage adjustments of medications excreted by the kidneys.

Common urinary elimination problems

People with urinary problems most commonly have disturbances in voiding that involve a failure to store urine or a failure to empty urine. These disturbances result from impaired bladder function, obstruction to urine outflow or inability to voluntarily control micturition. Chronic kidney disease is a significant health problem in the Australian and New Zealand community, causing a significant and ongoing health burden on the person, their family and the healthcare system.

Lower urinary tract infections

Urinary tract infections are very common throughout the life span but are more prevalent in older people. It is estimated that 1 in 3 women and 1 in 20 men will develop a UTI during their lifetime. Approximately 1 in 3 women will have a UTI requiring treatment before the age of 24 years (Masson and others, 2009). When the infection is confined to the bladder and urethra it is termed a lower urinary tract infection. Bacteria in the urine (bacteriuria) may lead to the spread of organisms into the kidneys (upper urinary tract infection).

The most common organisms that cause UTIs in otherwise healthy people are Escherichia coli (85%), Staphylococcus saprophyticus (10%), Enterococcus faecalis and other enterobacteriacae (Gray and Robinson, 2010). Microorganisms most commonly enter the urinary tract through the urethral route. Bacteria inhabit the distal urethra, external genitalia and vagina in women. Organisms enter the urethral meatus easily and travel up the inner mucosal lining to the bladder. Risk factors for developing a UTI include being a postmenopausal woman, sexual activity in women, pregnancy, and underlying anatomical abnormality (vesico-ureteric reflux, history of recurrent UTI, urinary obstruction, presence of renal calculi). Older adults and people with progressive underlying disease or decreased immunity are also at increased risk (Gray and Moore, 2009).

Most children and adults with lower UTIs have pain or burning during urination (dysuria) as urine flows past inflamed tissues. An irritated bladder causes a frequent and urgent sensation of the need to void. Irritation to bladder and urethral mucosa can result in blood-tinged urine (haematuria). The urine can appear concentrated and cloudy because of the presence of white blood cells (WBCs) or bacteria. The signs and symptoms of UTI in older adults can be less obvious. Often the first symptoms may be confusion and dehydration. An infection in the upper urinary tract (kidneys—pyelonephritis) can cause more-severe symptoms such as (commonly) flank pain, tenderness, nausea, vomiting, fever and chills.

The most common cause of infection in hospitalised patients is the introduction of instruments into the urinary tract. For example, the introduction of a catheter through the urethra provides a direct route for microorganisms. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) are common. The incidence of bacteriuria increases with the duration that the catheter is in situ. According to Gray and Moore (2009:105), nearly all people with an indwelling urinary catheter will have bacteriuria within 30 days. Hence, a goal of care is to remove the urinary catheter as soon as possible. Bacteria ascend along the outside of the catheter on the urethral wall or travel up the catheter’s lumen. The catheter interferes with the normal voiding mechanism that acts as a defence against organisms entering the urethra. Local irritation to the urethra or bladder further predisposes tissues to bacterial invasion. The majority of CAUTIs do not cause generalised symptoms and are generally not treated with antibiotics. Use of antibiotics in this situation can result in bacterial resistance.

Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence is defined as the complaint of any involuntary loss of urine (Abrams and others, 2009). It may be temporary or permanent. Urinary incontinence can be further defined according to the person’s symptoms: stress incontinence, urge incontinence, mixed incontinence (a mix or stress and urge symptoms), nocturnal enuresis, post-micturition dribble, continuous urinary leakage, overactive bladder and functional incontinence (Abrams and others, 2009; Newman and Wein, 2009a) (see Table 38-1 for definitions, risk factors and defining characteristics).

TABLE 38-1 TYPES OF URINARY INCONTINENCE

| DESCRIPTION | RISK FACTORS | SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|---|

| URGE URINARY INCONTINENCE | ||

| Involuntary leakage of urine after a strong sense of urgency to void | Decreased bladder capacity; irritation of bladder stretch receptors; alcohol or caffeine ingestion; increased fluid intake; infection | Significant urinary urgency—inability to defer voiding once the urge has occurred, often with frequency (more often than every 2 hours) |

| STRESS URINARY INCONTINENCE | ||

| Involuntary leakage of urine on effort or exertion or on sneezing or coughing | Coughing, laughing, sneezing or lifting with a full bladder; obesity; full uterus in third trimester; incompetent bladder outlet; vaginal or uterine prolapse; weak pelvic floor muscles | Loss of urine with increased intra-abdominal pressure. Usually small amounts of urine lost |

| MIXED URINARY INCONTINENCE | ||

| Involuntary leakage of urine associated with urgency and also with effort or exertion or on sneezing or coughing | Coughing, laughing, sneezing or lifting with a full bladder; obesity; full uterus in third trimester; incompetent bladder outlet; vaginal or uterine prolapse; weak pelvic floor muscles | Loss of urine with increased intra-abdominal pressure, urinary urgency and frequency. Can be a small or large amount of urine lost |

| FUNCTIONAL URINARY INCONTINENCE | ||

| Involuntary urine loss that occurs because of impaired functional status—impaired cognitive status, impaired mobility and dexterity and/or environmental barriers that block toilet access | Change in environment: sensory, cognitive or mobility deficits | Urge to void that causes loss of urine before reaching appropriate receptacle. The patient with cognitive changes may have forgotten what to do or not recognise the place to void |

| NOCTURNAL ENURESIS | ||

| Involuntary loss of urine occurring during sleep | Abnormal night-time secretion of antidiuretic hormone, developmental delay in development of control of the micturition reflex, family history of enuresis. Exacerbated by urinary tract infection | Urinary loss while asleep |

| OVERACTIVE BLADDER | ||

| Symptoms of urgency with or without urge incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia | Neurological disorders such as stroke, dementia, Parkinson’s disease; stress urinary incontinence, inflammation, idiopathic | Diagnosed with urodynamic testing. Bothersome urgency usually associated with frequency and nocturia |

| POST-MICTURITION DRIBBLE | ||

| Feeling of involuntary urine loss immediately after finishing voiding | Urinary retention, urethral abnormalities such as a diverticulum in women and post prostatectomy in men | Men will complain of urine loss immediately after voiding; women will complain of urine loss on rising from the toilet |

| NEUROGENIC DETRUSOR OVERACTIVITY (‘REFLEX’ INCONTINENCE) AND DETRUSOR SPHINCTER DYSSYNERGIA | ||

| Urinary incontinence, urinary retention. Urine leakage occurs without warning | Disruption of the central nervous system regulation of the micturition reflex as seen in neurological disorders such as spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, etc | Urine leakage occurs without warning |

Adapted from: Abrams P, Cardozo P, Khoury S and others, editors, 2009 Incontinence, ed 4. Paris, Health Publications Ltd, Paris; Gray M, Moore KN 2009 Urologic disorders: adult and paediatric care. St Louis, Mosby; Newman DK, Wein A 2009 Managing and treating urinary incontinence. Baltimore: Health Professionals Press.

Urinary incontinence affects up to 13% of Australian men and up to 37% of Australian women (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2006). In New Zealand, 17% of adult women have bothersome urinary incontinence. The prevalence is even higher in adult Māori women, at 47% (New Zealand Continence Association 2011).

Urinary incontinence significantly affects a person’s quality of life, including the person’s daily activities, sexuality, body image and self-esteem. Efforts to cope with the problem may lead to the person reducing their fluid intake, increasing the frequency of voiding and avoiding social contact (Newman and Wein, 2009a; St John and others, 2010). There is also evidence in the literature that continence problems have significant impact on family caregivers, including depression (Gotoh and others, 2009; Hayder and Schnepp, 2008).

Prostatic hypertrophy and prostate cancer

Benign enlargement of the prostate gland that can occur with ageing can obstruct the urethra and make voiding difficult. Benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) is a common condition affecting men from the age of approximately 50 years. According to Gray and Moore (2009:50), 50% of 60-year-old men and 80% of 80-year-old men will experience some bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). The typical symptoms are decreased urinary stream, hesitancy, intermittent stream, nocturia, frequency and urgency (see Table 38-2 for a description of common types of lower urinary symptoms). Some men may develop an acute or chronic urinary retention (see below). Treatment for men who have symptomatic BPH include medications which aim to relax the smooth muscles at the bladder neck (alpha-blockers) or to reduce the size of the prostate gland (5-alpha-reductase inhibitors), or surgery—for example trans-urethral resection of the prostate (Bright and Abrams, 2010).

TABLE 38-2 COMMON LOWER URINARY TRACT SYMPTOMS

| SYMPTOMS | DESCRIPTION | CAUSES OR ASSOCIATED FACTORS |

|---|---|---|

| STORAGE/FILLING SYMPTOMS | ||

| Frequency | Voiding more than 8 times in a 24-hour period | Increased fluid intake, bladder inflammation, increased pressure on bladder (pregnancy, psychological stress), overactive bladder. |

| Nocturia | Urination, particularly excessive or frequent, at night | Excessive fluid intake before bed (especially coffee or alcohol), renal disease, ageing process, prostate enlargement, heart failure, incomplete bladder emptying, use of sedatives and hypnotics |

| Urgency | Strong and immediate need to void immediately that is not easily deferred | Bladder irritation or inflammation from infection, incompetent urethral sphincter, psychological stress |

| EMPTYING/VOIDING SYMPTOMS | ||

| Dysuria | Painful or difficult urination—often described as a ‘burning’ sensation | Bladder inflammation, trauma or inflammation of urethral sphincter |

| Hesitancy | Difficulty initiating urination and delay in onset of voiding | Prostate enlargement, anxiety, urethral oedema |

| Incomplete bladder emptying | The sensation that urine remains in the bladder after micturition | Abnormal bladder sensations, bladder outlet obstruction, neurological diseases, pelvic organ prolapse |

Adapted from Newman DK, Wein A 2009 Managing and treating urinary incontinence. Baltimore: Health Professionals Press.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer that occurs in men. The risk of developing prostate cancer to age 75 years is 1 in 8 for Australian men (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2008). There are similar rates of prostate cancer in New Zealand men (Ministry of Health, 2011). Prostate cancer is essentially a disease of older men, with 85% diagnosed after 65 years of age (Cancer Council Australia 2011). Prostate cancer is rare before the age of 40 years and its incidence rises rapidly after age 60 years. The cause of prostate cancer is unknown. Apart from advancing age and being male, the strongest established risk factor is a family history of the disease (Bright and Abrams, 2010). Part of the concern for men and for healthcare workers is the non-specific nature of the typical presenting signs and symptoms associated with prostate cancer. In the early stages they are likely to be asymptomatic. Differential diagnosis involves a health assessment and will include a prostatic-specific antigen (PSA) test, digital rectal examination (DRE) and transrectal ultrasound and biopsy. Treatment options for prostate cancer include surgery (radical prostatectomy), androgen deprivation therapy and radiation therapy.

Urinary retention

Urinary retention is defined as the inability to fully empty the bladder after voiding or a complete inability to urinate (Gray and Moore, 2009). Urinary retention can be acute or chronic. In acute retention, key signs are bladder distension and absence of urine output over several hours. The bladder may hold as much as 2000–3000 mL of urine. The person may experience significant discomfort, tenderness over the symphysis pubis, restlessness and diaphoresis (sweating). Acute retention is most common in men due to obstruction of the urethra as a result of benign enlargement of the prostate gland. It is a medical emergency that requires immediate intervention.

Chronic retention results from incomplete bladder emptying over a period of time. It results from either a partial obstruction of the urethra (e.g. urethral stricture, enlarged prostate, chronic constipation) and/or from reduced ability of the detrusor (bladder) muscle to contract during voiding (e.g. spinal cord injury, nerve damage from diabetes mellitus) (Gray and Moore, 2009). As retention progresses, retention with overflow may develop. Pressure in the bladder builds to a point where the external urethral sphincter is unable to hold back urine. The person may have an urge to void but is only able to void small amounts. Some people may experience intermittent episodes of incontinence, and others constant dribbling of urine. Depending on the cause of the chronic retention, the person may or may not be aware of the incomplete bladder emptying. Chronic retention caused by partial obstruction can result in increased pressures within the urinary tract causing damage to the kidneys (postrenal obstruction). Incomplete bladder emptying can predispose the person to UTIs.

Chronic kidney disease

Diseases that cause irreversible damage to the glomerulus or tubules result in permanent alterations in renal function. Chronic kidney disease (CKD—formally known as chronic renal failure) or end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) are the terms used to describe the resulting decline in kidney function from these processes. CKD is damage to the kidneys or reduced renal function lasting more than 3 months (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009). It is estimated that 13% of Australians are living with CKD (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, especially those living in remote communities, are at high risk of developing CKD and the incidence is increasing (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011). There is a similar incidence of CKD in New Zealand, with 16% of New Zealanders having some form of kidney damage, and a higher incidence in Māori and Pacific Islanders (Joshy and others, 2010). A major risk factor for developing CKD is diabetes. Other risk factors include hypertension, cigarette smoking, obesity, family history of CKD and being over 50 years of age (Kidney Health Australia, 2011).

The person with ESKD manifests numerous metabolic disturbances that require treatment for survival. The associated symptoms experienced by the patient occur as a result of the uraemic syndrome. This syndrome is characterised by an increase in nitrogenous wastes in the blood, altered regulatory functions (causing marked fluid and electrolyte abnormalities), nausea, vomiting, headache, coma and convulsions. Treatment options include methods to correct these biochemical derangements. The problem may be managed conservatively with medications and a regimen of dietary and fluid restrictions. However, as worsening of the uraemic symptoms becomes evident, more-aggressive treatment is indicated. These treatments are known as renal replacement therapies. Dialysis (see Box 38-2) and organ transplant are the two methods of renal replacement; the two methods of dialysis are haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Both dialysis methods can be applied for a short or a long time, and they require specialised equipment and appropriately qualified nurses.

BOX 38-2 INDICATIONS FOR DIALYSIS

• Renal failure that can no longer be controlled by conservative management (i.e. dietary modifications and administration of medications to correct electrolyte abnormalities)

• Worsening of uraemic syndrome associated with end-stage kidney disease (i.e. nausea, vomiting, neurological changes, pericarditis)

• Severe electrolyte and/or fluid abnormalities that cannot be controlled by simpler measures (e.g. hyperkalaemia, pulmonary oedema)

Haemodialysis involves using a machine equipped with a semipermeable filtering membrane (artificial kidney) that removes accumulated waste products from the blood. In the dialysis machine, dialysate fluid is pumped through one side of the filter membrane (artificial kidney) while the patient’s blood passes through the other side. The processes of diffusion, osmosis and ultrafiltration clean the patient’s blood, and it is returned through a specially placed vascular access device (LaRocco, 2011).

An organ transplant is the replacement of the patient’s diseased kidney with a healthy one from a living or cadaveric donor of compatible blood and tissue type. After the patient (recipient) is deemed medically and psychosocially suitable, the organ is surgically implanted. Immunosuppressive medications are administered for life to prevent the body rejecting the transplanted organ. Unlike the other treatments, a successful organ transplant offers the patient the potential for restoration of normal kidney function for varying periods of time.

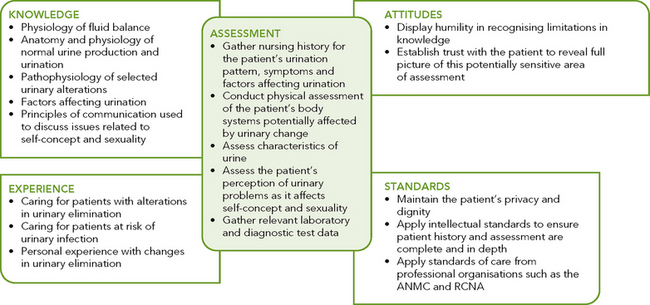

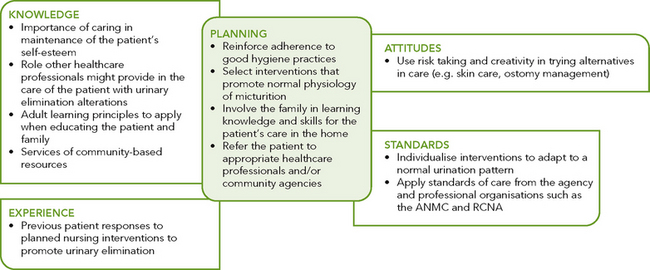

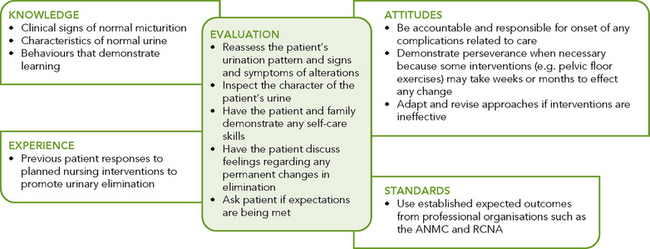

Critical thinking synthesis

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from patients, critical-thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Assessment of a person for risk factors or actual urinary elimination problems requires specific knowledge and sensitivity in approaching health issues that the person may find difficult to discuss (see Figure 38-4).

NURSING PROCESS AND URINARY ELIMINATION

ASSESSMENT

Assessing urinary elimination patterns and determining the aetiology of symptoms requires a focused nursing history, physical assessment including abdominal examination, assessment of skin, mobility and where necessary cognition, fluid balance, voiding patterns and urinalysis. In most cases you would also need to assess bowel function (see Chapter 37).

Nursing history

The focused nursing history provides a review of the person’s usual urinary elimination pattern and habits. The purpose of this nursing history is to identify normal and abnormal patterns, habits and the person’s perception of normal and abnormal urinary function. This information enables identification of possible problems and gives direction to the physical examination. The nursing history includes a review of the patient’s elimination pattern, LUTS and an assessment of other factors that may be affecting the ability to urinate normally.

• Determine the person presenting’s concern. It is important to acknowledge the person’s perception of their urinary elimination problem and how this affects their quality of life. How does this problem affect their work, school, activities, relationships, etc?

• Determine the usual voiding pattern. Ask the person about the frequency and pattern of urination, including frequency and times of day, normal volume at each voiding and any recent changes. Frequency varies among individuals and varies with intake and other types of fluid losses. The common times for urination are on waking, after meals and before bedtime. Most people void an average of five or more times a day. Information about the pattern of urination establishes a baseline for comparison. Having the person or caregiver complete a ‘voiding or bladder diary’ can enhance accurate assessment of the person’s urinary pattern. The information collected in a typical voiding diary includes: time of voiding and the measured amount voided, fluid intake and type, presence of symptoms (urge, incontinence, etc). To improve accuracy, the person completing the diary must understand what information must be recorded. Normally a voiding diary would be kept for three 24-hour periods so that the person’s normal urinary elimination patterns can be determined. Keep in mind that normal changes with ageing predispose older adults to certain elimination problems (see Research highlight).

• Characteristics of the urine. Assess colour, odour, clarity, etc.

• Fluid intake/fluid balance. In a hospitalised patient, assessment of fluid balance is often undertaken. The data is recorded on a fluid balance chart, and intake and output are compared over a 24-hour period (see below). The information in the voiding diary will help you determine the amount and types of fluid that the person usually consumes. If the person has not completed a voiding diary, ask them about their usual fluid intake (type and amount) and pattern of intake.

• Pain. There are several sites for pain associated with urinary tract dysfunction. These include flank pain (costovertebral angle), usually unilateral, which is associated with a problem in the kidney or renal pelvis; and suprapubic pain which is associated with UTI. Ask about the frequency and character of the pain. Is the pain associated with voiding?

• Lower urinary tract symptoms. LUTS may occur in more than one type of disorder. During assessment ask the patient about the LUTS listed in Table 38-2. Also investigate the factors that precipitate or aggravate symptoms. It is important to specifically ask people about the presence of urinary incontinence. People are embarrassed about this problem and are often reluctant to talk about it (Keyock and Newman, 2011).

• Other symptoms. Generalised symptoms can also result from urinary elimination problems, especially CKD and upper UTI. Another important association is heart failure; people who have heart failure tend to retain fluid over the day. In addition to a sense of breathlessness on exertion, the person may complain of nocturia. This happens because of the diuresis that may occur in these people when they lie down and their peripheral oedema is relieved. Ask the person about the presence of fever, nausea and vomiting, weight gain or loss, peripheral oedema, fatigue and lethargy, headache, itching skin, etc.

Research focus

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are common in the community and can cause decreased quality of life, loss of dignity, social isolation and depression and can interfere with activities of daily living. People living with LUTS use a variety of self-management strategies to deal with the symptoms, including voiding frequently, pelvic floor muscle exercises, use of continence products and fluid manipulation. Little is known about how people experiencing LUTS use fluid manipulation to manage their symptoms.

Research abstract

The purpose of this project was to determine how individuals use fluid manipulation to self-manage the urinary symptoms of daytime frequency, urgency and urine leakage and the underlying rationale for this behaviour. A mixed-methods design included statistical analysis of data from a population-based survey of urological symptoms and qualitative analysis of in-depth interviews. Quantitative data were collected from 5503 participants participating in a community health survey of urological symptoms in Boston (USA). Qualitative data were derived from in-depth interviews from a random subsample of men and women with LUTS.

The findings revealed that fluid intake was greater in men and women reporting frequency (p < 0.001). Women with frequency drank significantly more water (p < 0.001), while women with urgency drank significantly less water (p = 0.047). Qualitative data analysis revealed that some respondents restricted fluid intake while others increased it, in both cases with the expectation of improved symptoms. This study found divergent expectations of the role of fluids in alleviating symptoms, leading some individuals to restrict and others to increase fluid intake.

Evidence-based practice

Individuals with LUTS may need guidance in fluid management. Nurses should be aware that patients may self-manage LUTS by restricting fluid intake, putting them at risk for dehydration, constipation and urinary tract infection, but also that they may be increasing their fluid intake, which could worsen symptoms.

• Past health history. Personal or family history of health issues affecting the urinary tract; for example, infection, urinary calculi, family history of renal or bladder cancer, neurological disorders, surgery including gynaecological, spinal or bowel surgery, diabetes, urinary catheterisation or any issues with constipation. For men, ask about history of prostate cancer. For women, ask about obstetric history (number of births, birthweights, type of delivery, etc) and, if relevant, menopausal symptoms.

• History of smoking. Smoking is a known risk factor for bladder and renal cancer and can contribute to voiding problems.

• Self-care practices. Ask about activity and exercise patterns, toileting and hygiene, use of continence aids and appliances. The patient’s mobility and dexterity need to be evaluated to determine whether the patient needs assistive devices or personnel. You need to make a judgment about the need for questioning in this area based on your observation of the person. For example, questions regarding assistance needed to get to the toilet, undressing/redressing, hygiene, and use of toileting aids (commode chairs, raised toilet seats, etc). Where patients live may affect their toileting habits. If the patient is sharing living quarters, how many bathrooms are there? Do patients have their own bathroom, or do they need to share and thus adjust the time they use the bathroom to accommodate others?

• Medications (prescribed and over the counter) currently being used. Many medications can affect bladder function.

Physical examination

The physical examination is focused on body systems and functions related to urinary elimination problems (see Chapter 27). You will need to make a judgment about the specific areas to include in your examination, which may include assessment of fluid balance (including skin and mucous membranes), abdomen and perineal area/skin. You will also need to complete a urinalysis and may be involved in specimen collection for microscopic examination and microbiological and biochemical analysis.

SKIN AND MUCOSAL MEMBRANES

Problems with urinary elimination are often associated with fluid and electrolyte disturbances. By assessing skin turgor and the oral mucosa, you are assessing the person’s hydration status. A more general skin assessment may be required if the person has urinary incontinence. Specifically assess the health of skin on the upper thighs, groin and perineal area.

ABDOMINAL ASSESSMENT

As mentioned previously, often an assessment of urinary elimination is done at the same time as an assessment of bowel elimination. Specific aspects of an abdominal assessment relevant to urinary elimination involve inspection, palpation and percussion.

Inspect all four abdominal quadrants for contour, shape, symmetry and skin colour. Inspection also includes noting masses, scars, stomas and lesions. In adults the bladder rests below the symphysis pubis and cannot be examined abdominally. When distended, the bladder rises above the symphysis pubis at the midline of the abdomen and may extend to just below the umbilicus. A distended bladder may appear as a protuberance on the central lower abdomen.

Palpation of the abdomen is performed to determine distension (a drum-like tightness), areas of tenderness or the presence of masses (see Chapter 27). It is important for the person to relax. Tensing abdominal muscles interferes with palpating underlying organs or masses. If the examination reveals significant tenderness in any area of the abdomen, note the location of the tenderness and do not progress with further palpation or percussion. Refer the person to a medical practitioner for further assessment, as the pain/tenderness may indicate serious underlying pathology such as acute appendicitis or inflammation of the bowel.

The partially filled bladder normally feels smooth and rounded. As the nurse applies light pressure to the bladder, the patient may feel tenderness or even pain. Even when the bladder is not visible, palpation may cause the urge to urinate. A person with urinary retention may have a significantly distended bladder that you may be able to palpate centrally on the lower abdomen. The suprapubic area may also be tender if the person has a UTI.

Percussion detects lesions, fluid or gas within the abdomen. On percussion a distended bladder will elicit a dull percussion tone. If the kidneys become infected or inflamed, flank pain typically develops. Percussion at the costovertebral angle (the angle formed by the spine and the twelfth rib) may indicate inflammation of the kidney. If you find that the person has kidney pain, they should be referred to a medical practitioner for further assessment.

In most acute care hospitals you will have access to a bladder scanner. This is an ultrasound device which detects and measures the volume of urine in the bladder. It is commonly used to determine the volume (if any) of residual urine left in the bladder after voiding. A conductive gel is applied to the lower abdomen and the transducer is placed on the skin and moved about until a reading is obtained. Once the bladder volume is determined, the person is asked to void normally. The scan is repeated to determine the presence of a residual urine volume. The accuracy of the scan is determined by correct use of the equipment and patient selection. You will need to follow the manufacturer’s instructions on correct use of the bladder scanner.

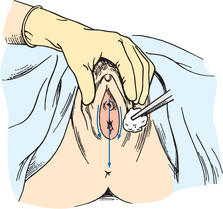

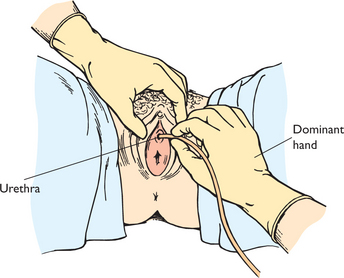

URETHRAL MEATUS

Assess the urinary meatus to note the presence of discharge, inflammation and lesions. This assessment screens for infections and other abnormalities. To examine the female, a dorsal recumbent position provides full exposure of the genitalia. While wearing gloves, retract the labial folds to see the urethral meatus. Normally the meatus is pink and appears as a small slit-like opening below the clitoris and above the vaginal orifice. There is normally no discharge from the meatus. If present, specimens of urethral discharge should be obtained before the patient voids.

Women with vaginal infections are susceptible to UTIs because the vaginal discharge may travel easily to the urethral meatus. Older women commonly have vaginitis as a result of hormonal deficiencies. Inspect the vaginal orifice and note any discharge and the appearance of the labial and vaginal mucosa. Normally the mucosa is pink and moist.

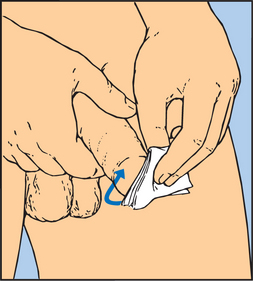

The male urethral meatus is normally a small opening at the tip of the penis. Inspect the meatus for discharge, inflammation and lesions. It may be necessary to retract the foreskin in uncircumcised men to see the meatus.

ASSESSMENT OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT

As mentioned previously, assessment of fluid balance is often undertaken for a hospitalised patient. The data are recorded on a fluid balance chart, and intake and output are compared over a 24-hour period. All sources are included, including oral intake, intravenous fluid infusions, tube feedings and fluid instilled into nasogastric or gastric tubes.

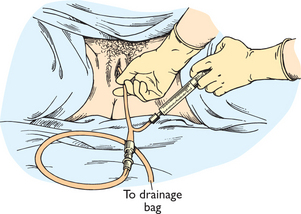

The volume of urinary output is measured (with plastic receptacles, bed pans or urinals) with each voiding. If the person has a urinary catheter, precise measurement of the volume of urine is done by using a measuring device which is part of the urinary drainage bag. The urine drains passively into the urimeter, which holds 100–200 mL of urine. After measuring the urine in the urimeter, typically at hourly or 2-hourly intervals, the urine can be drained directly into the large drainage bag without opening the closed drainage system. If there is no need to measure hourly or 2-hourly urine output, urine volume can be measured by draining the urine from the drainage bag into a plastic graduated measuring receptacle (Figure 38-5). Standard infection-control precaution measures should be used when measuring urine.

FIGURE 38-5 Urine drainage bag.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

Report any extreme increase or decrease in urine volume. An hourly output of less than 0.5 mL/kg for more than 2 hours is cause for concern. Similarly, consistently high volumes of urine (polyuria), more than 2000–2500 mL daily, should be reported to the person’s medical practitioner.

ASSESSMENT OF URINE

The characteristics of the urine should also be recorded. Inspect the urine for colour, clarity and odour. Normal urine ranges from a pale straw colour to amber, depending on its concentration. Urine is usually more concentrated in the morning or with fluid volume deficits. As the person drinks more fluids, urine becomes less concentrated. Bleeding from the kidneys or ureters causes urine to become dark red or tea-coloured; bleeding from the bladder or urethra causes bright-red urine. Various medications also change urine colour. Eating beetroot, rhubarb or blackberries may cause red urine. Special dyes used in intravenous diagnostic studies eventually discolour urine. Dark-amber urine may be the result of high concentrations of bilirubin caused by liver dysfunction. Document and report any abnormal colour or sediment, especially if the cause is unknown.

Normal urine is transparent at voiding; urine that stands several minutes in a container becomes cloudy. Freshly voided urine in patients with renal disease may be cloudy or foamy because of high protein concentrations. Urine can be thick and cloudy as a result of bacteria.

Urine has a characteristic odour. The more concentrated the urine, the stronger the odour. Stagnant urine has an ammonia odour, which is common in patients who are repeatedly incontinent. A sweet or fruity odour occurs from acetone or acetoacetic acid (by-products of incomplete fat metabolism) seen with diabetes mellitus or starvation. Keep in mind that some foods, for example asparagus, can change the odour of urine. If you detect an unusual odour, especially when there are no other abnormalities in the urine, ask the person about what they have been eating in the last 12–24 hours.

Urine testing

Urine specimens are often collected for laboratory testing. The type of test determines the method of collection. Specimens that need to be sent to the laboratory for analysis should be labelled with the patient’s name and date and time of collection. They should be transported to the laboratory in a timely fashion to ensure accuracy of test results. Standard infection-control precaution measures should be used when collecting urine specimens (see Chapter 29). In all cases you need a fresh urine sample.

COLLECTING A CLEAN VOIDED URINE SPECIMEN

A clean, freshly voided specimen is collected so that urinalysis and inspection of the urine can be performed. The person is asked to void into a clean urine cup, urinal or bed pan. Most people are able to do this independently; however, if the person has poor mobility they may require assistance. The person should void before defecating so that faeces does not contaminate the specimen. Female patients are also instructed not to place toilet tissue in the bed pan. Only 50–100 mL of urine is needed for accurate testing. After the specimen is collected, the urine is inspected and then tested using the appropriate testing strips (dipsticks).

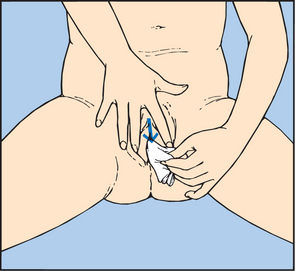

COLLECTING A MIDSTREAM URINE SPECIMEN

To obtain a specimen relatively free of the microorganisms growing in the lower urethra, the patient will need to be instructed about the method for obtaining a midstream urine specimen (Skill 38-1). This type of specimen is needed to culture urine to determine the presence of bacteriuria and to check for antibiotic sensitivity (micro-culture and sensitivity or MC&S test). After appropriate cleaning of the external genitalia, the person begins voiding, allowing a small amount of urine to escape; then during the middle portion of voiding, the person collects the specimen in a sterile container. The initial stream of urine cleans or flushes the urethral orifice and meatus of resident bacteria. It is easiest for a patient to obtain midstream urine specimens while using toilet facilities.

SKILL 38-1 Collecting a midstream (clean-voided) urine specimen

DELEGATION CONSIDERATIONS

If appropriate, an alert patient who is physically able may be instructed to collect the specimen.

EQUIPMENT

• Soap or cleaning solution, washcloth and towel or disposable cleansing towel

• Sterile specimen collection jar with lid

• If the person cannot collect the specimen themselves, a bed pan, bedside commode or specimen hat

| STEPS | RATIONALE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| May indicate bladder fullness. | |||

| Reveals patient’s ability to cooperate during procedure. | |||

| Determines level of assistance. | |||

| Information allows you to clarify misunderstandings and promotes patient cooperation. | |||

| Helps patient understand the procedure. | |||

| Faeces change characteristics of urine and may cause abnormal values. | |||

| Improves likelihood of patient being able to void. | |||

| Privacy allows patient to relax and produce specimen more quickly. | |||

| Prevents transmission of microorganisms to nurse, provides easy access to perineal area to collect specimen. | |||

|

7. Open the sterile specimen container, placing cap with sterile inside surface up; do not touch inside of container or cap (see Chapter 29). |

Aseptic technique is essential to maintain sterility of equipment and specimen. Contaminated specimen is most frequent reason for inaccurate reporting of urine cultures and sensitivities. | ||

| Provides access to urethral meatus. | |||

| Clean from area of least contamination to area of greatest contamination, to decrease bacterial levels. | |||

| Initial stream flushes out microorganisms that accumulate at urethral meatus and prevents transfer into specimen. | |||

| Clean from area of least contamination to area of greatest contamination, to decrease bacterial levels. | |||

| Initial stream flushes out microorganisms that accumulate at urethral meatus and prevents transfer into specimen. | |||

| Prevents contamination of specimen with skin flora. | |||

| If foreskin not replaced, swelling and constriction may occur, causing pain and possible obstruction to urine flow. | |||

| Retains sterility of inside of container and prevents spillage of urine. | |||

| Prevents transfer of microorganisms to others. | |||

| Promotes relaxing environment. | |||

| Prevents inaccurate identification that could lead to errors in diagnosis or treatment. | |||

| Critical decision point: If patient is menstruating, indicate information on laboratory requisition. | |||

| Reduces transmission of infection. | |||

| Bacteria grow quickly in urine, and specimen should be analysed immediately to obtain correct results. | |||

| RECORDING AND REPORTING | HOME CARE CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|

COLLECTING A URINE SPECIMEN FROM A PATIENT WITH AN INDWELLING URINARY CATHETER

You may need to perform a urinalysis using dipsticks or collect a specimen for laboratory analysis from a person who has an indwelling urinary catheter. A urine specimen is not collected for culture from a urine drainage bag unless it is the first urine drained into a new, sterile bag. Bacteria grow rapidly in the drainage bags and could cause an inaccurate result. The aim is to obtain a fresh urine sample while maintaining the closed system between the catheter and the urine drainage bag. The sample needs to be drawn from the needleless sampling port in the drainage bag tubing. You should not disconnect the catheter from the drainage bag tubing, nor insert a needle into the catheter or the drainage bag tubing. The following steps should be undertaken:

• Inform the patient of the purpose of collecting the urine.

• Place the urine drainage bag tubing so that a loop near the drainage port is lying flat on the patient’s bed or chair (so that urine will collect in the tubing). In some cases you may need to clamp off the tubing; however, make sure that you return to take the sample within 15 minutes so that urine does not build up in the bladder.

• After performing hand hygiene, don non-sterile gloves.

• Assemble a sterile 10 mL syringe.

• If the specimen is for laboratory analysis, have a sterile pathology specimen container close by—do not touch the inside of the container or the lid. Make sure that the container is labelled with the patient’s details and date and time of the specimen collection. Also make a note on the label that the urine was obtained from a patient with an indwelling catheter.

• Wipe the needleless port with an antimicrobial swab. When this has dried, carefully insert the hub of the syringe through the needleless port into the catheter lumen. Aspirate 5–10 mL of urine and remove the syringe from the sampling port. Transfer the urine into the sterile container using an aseptic technique (see Chapter 29).

• Return the drainage bag tubing to the usual position so that urine will flow freely into the drainage bag.

• Remove the gloves and properly dispose of equipment. Perform hand hygiene.

The specimen is transferred to the laboratory in a sealed plastic bag with the request slip for testing. It generally takes 24 hours to culture the bacteria and 48 hours to identify sensitivity to antimicrobial agents.

COLLECTING URINE OVER A SPECIFIC TIME PERIOD

Some tests of renal function and urine composition, such as measuring levels of adrenocortical steroids or hormones, creatinine clearance or protein quantitation tests, require collection of urine over 2-, 12- or 24-hour intervals. The urine is collected each time the person voids and placed in a specially labelled container over the prescribed period of time. The timed collection period begins after the person urinates. This sample is discarded and the collection begins at this time. You will need to inform the patient that all urine must now be collected, and note the starting time on the collection container and on the laboratory requisition. The person then collects all urine voided in the timed period. Each voiding is collected in a clean container and immediately emptied into the larger container. Any missed specimens will make test results inaccurate. The person should be reminded to void before defecating so that faeces or toilet paper do not contaminate urine. The person should void the last specimen at the end of the timed period. For example, for a 24-hour collection the person first voids at 0800. This sample is discarded and the 24-hour time period begins. All urine from this time onwards is saved until 0800 the next day. The person voids as close to 0800 as possible. This urine is added to the collection container and the time period is completed.

COLLECTING URINE FROM CHILDREN

Specimen collection from infants and children is often difficult. Adolescents and school-age children are usually able to cooperate, although they may be embarrassed. Preschool children and toddlers have difficulty voiding on request. Offering a young child fluid 30 minutes before requesting a specimen may help. Gain cooperation from the parents in obtaining the specimen.

A young child may be reluctant to void in unfamiliar receptacles. A potty-chair or specimen hat placed under the toilet seat is usually effective. For infants or toddlers who are not toilet-trained, clear plastic, single-use bags with self-adhering material (paediatric urine collector) can be attached over the child’s urethral meatus. Specimens should not be obtained by squeezing urine from the nappy material. When the specimen is obtained, it is placed in a sterile container and labelled with the child’s details and date and time of the specimen collection. Also, make a note on the label that the urine was obtained using a paediatric urine-collecting device.

COMMON URINE TESTS

Urine tests include urinalysis, specific gravity and urine culture.

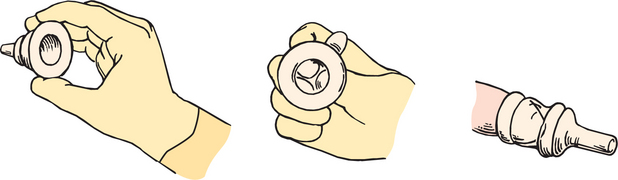

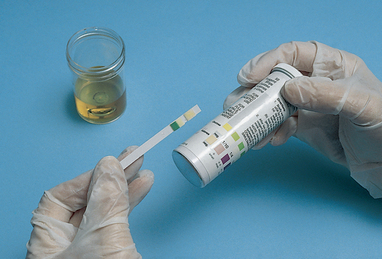

Urinalysis is a test commonly performed by nurses in all healthcare settings. The urine specimen should be fresh. The purpose of the urinalysis is to determine the constituents of the urine and determine the presence of abnormalities. Using standard infection-control guidelines, dip the reagent strips (often called dipsticks) into the urine, making sure that all of the reagent pads are submerged in the urine. Taking care to drain the urine off the dipstick, observe for a colour change in the time interval designated on the packaging (Figure 38-6). Various brands of urine dipsticks test for varying abnormalities. Typically the strips test for glucose, bilirubin, ketones, specific gravity, microscopic blood, pH, protein, urobilinogen, nitrites and leucocytes. The exact detail of the results of the urinalysis is recorded in the patient’s clinical progress notes. Urine may also be sent to the laboratory where urinalysis is performed using specialised equipment. Table 38-3 lists normal values for a urinalysis.

FIGURE 38-6 Checking results of a chemical reagent strip dipped in urine.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2013 Fundamentals of nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

TABLE 38-3 ROUTINE URINALYSIS—ADULTS

Adapted from: Royal Society of Pathologists of Australia Manual 2009. Online. Available at http://rcpamanual.edu.au; Gormella LG, editor, 2009 The 5-minute urology consult. Philadelphia, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Diagnostic examinations

The urinary system is one of the few organ systems amenable to accurate diagnostic study by several radiographical techniques. The two approaches for viewing urinary structures, direct and indirect techniques, can be quite simple or very complex, requiring extensive nursing intervention. These procedures are further subdivided into invasive or non-invasive categories.

NON-INVASIVE PROCEDURES

ABDOMINAL X-RAY

Also referred to as plain abdominal film or KUB (kidney, ureter, bladder), X-ray of the abdomen is commonly used to assess the gross structures of the urinary tract for abnormalities. It can determine size, symmetry, shape and location of the kidneys, ureters and bladder structures. It is also useful in showing calculi (if calcified) or tumours in these organs. In addition, the ribs or other surrounding support structures can be assessed for fractures or abnormalities. Lack of positive findings on the X-ray does not rule out the possibility of abnormalities in the urinary tract; additional diagnostic studies may be needed. No special preparation is needed prior to this procedure.

INTRAVENOUS PYELOGRAM (IVP)

This technique enables visualisation of the collecting ducts and renal pelvis and outlines the ureters, bladder and urethra. Although this procedure is non-invasive, it requires the patient to receive an intravenous injection of a radio-opaque dye. Because the kidneys and ureters lie behind the intestines, it is necessary that the patient receives a bowel preparation to empty the intestines before the procedure.

During the IVP, X-ray studies are taken at specific intervals over 30–60 minutes as the dye concentrates. The patient may also be asked to void during the procedure, to measure bladder emptying. Diseases or disorders of the urinary tract that should be investigated by this means include renal artery occlusion, tumours, cysts or calculi, vesico-urethral reflux and traumatic injuries.

RADIONUCLIDE TESTS

Radionuclide tests such as renal scans allow indirect viewing of urinary tract structures after an intravenous injection of radioactive isotopes. The emissions from the radionuclides can be photographed by special cameras. The isotope can be detected without the need for bowel preparation. A very low dose of radioisotope is used. No precautions against radioactive exposure are needed except for the use of disposable gloves if the patient uses a bed pan or urinal to void. Rinse bed pan or urinal and double-flush urine down the toilet to dilute any possible remaining radiation hazard.

After a radionuclide is injected, it circulates through the kidneys and is excreted. The renal scan measures radioactive concentrations. Except for the venepuncture, it is painless. The scanning procedure is completed in about 1 hour. Information pertaining to renal blood flow, anatomical structures and their excretory function can be obtained from this procedure.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY (CT)

This is a computerised X-ray procedure used to obtain detailed images of structures within a selected plane of the body. The tomographic scanner is a large machine that contains specialised computers and X-ray detector systems that function simultaneously to photograph internal structures in thin, transverse cross-sections (Figure 38-7). The computer, through a series of complex manipulations, is able to ‘reconstruct’ the cross-sectional image as a recognisable photograph on the television monitor. With this procedure it is possible to see abnormal pathological conditions such as tumours, obstructions, retroperitoneal masses and lymph node enlargement. Although this procedure is non-invasive, in some examinations oral or intravenous contrast material is used to enhance the areas under study. If intravenous contrast is used, it may be necessary to administer a bowel-cleaning solution orally (such as GoLYTELY), especially if additional organs in the abdominal cavity will be examined.

ULTRASONOGRAPHY

A valuable non-invasive diagnostic tool in the assessment of urinary disorders, ultrasonography or ultrasound makes use of high-frequency inaudible sound waves that reflect off tissue structures. Some of the sound waves are reflected back to the transducer as echoes; the velocity of the sound waves varies with tissue density. The patient is usually prone during the procedure but can be positioned in a sitting position. Ultrasound is often used to identify gross renal structures and structural abnormalities of the kidneys or lower urinary tract, and to assist with percutaneous biopsy. Abnormalities such as tumours or cysts in the kidney are easily identified. If a Doppler is used with the transducer, examination of blood flow through the kidney can also be performed. This procedure is painless.

INVASIVE PROCEDURES

ENDOSCOPY

Endoscopy is the visual inspection of a hollow body organ with the aid of a fibre-optic instrument. A cystoscopy enables visualisation of the interior of the bladder and urethra. The cystoscope is inserted through the patient’s urethra into the bladder. The instrument has an outer plastic or rubber sheath, an obturator that keeps the scope rigid during insertion, a telescope for viewing the bladder and urethra, and a channel for inserting catheters or special surgical instruments.