EQUIPMENT

• Special patient gown with press-studs at shoulder seams (makes removal with IV tubing easier)

• Prescribed IV fluid (with time tape attached)

• Over-the-needle catheter (ONC) for venepuncture (gauge will vary with patient’s body size and reason for IV fluid administration)

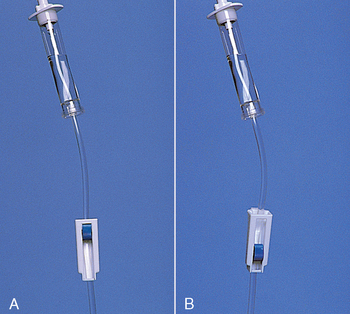

• Administration set (choice depends on type of solution and rate of administration; infants and children require microdrip tubing, which provides 60 drops/mL)

• Extension tubing (used when a longer IV line is necessary)

• Alcohol and povidone-iodine cleaning swabs or sticks (Rosenthal, 2003).

• Towel (to place under patient’s hand or arm)

• IV pole, rolling or ceiling-mounted

• Tourniquet (can be a source of contamination; use a single-use product)

• Arm board, if needed (used to maintain wrist or elbow joint position

• Needle disposal container (sharps container)

• Transparent dressing (e.g. Opsite, Tegaderm)

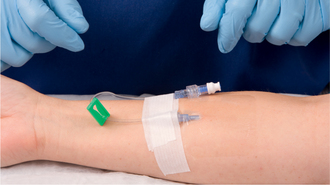

• ‘Interlink injection site’ (also called IV bung/plug/cap); connects to IV cannula; allows needless connection to the IV cannula.

• ‘Lever lock cannula’ or ‘threaded lock cannula’; attaches to the IV-giving set and connects the giving set to the cannula. Note that the giving set is never directly attached to the IV cannula without either of these Interlink connections

| STEPS | RATIONALE | |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment | ||

|

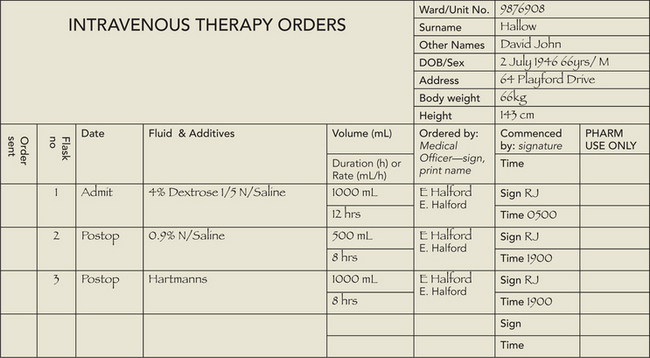

1. Review doctor’s order for type and amount of IV fluid, rate of fluid administration and purpose of infusion. In addition, follow the seven rights for administration of medications (see Chapter 31). |

||

|

2. Review clinical data for indications of type of fluid and electrolyte imbalance and reason for prescribed infusion; e.g. admission diagnosis, signs and symptoms (e.g. bodyweight, blood pressure, pulse, skin turgor, urine output, fluid balance chart, serum electrolytes, full blood count—haemoglobin [Hb] and haematocrit [Hct]). |

||

| May reveal information that affects insertion of devices, such as allergy to iodine, adhesive or latex. | ||

| Determines level of emotional support and patient education required. | ||

| Although the application of EMLA cream makes IV cannulation relatively painless, it must be applied at least 1 to 1.5 hours before the proposed procedure. It is effective for up to 4 hours post application. Not recommended for infants under 3 months of age. | ||

| Allows placement of appropriate-size catheter (i.e. 18 or 16 gauge for surgery) which will not interfere with medical procedures. | ||

| Persons at extremes in age develop fluid imbalances more rapidly because of a proportionately larger ECF volume; persons with heart failure and acute kidney disease may require fluid restriction and cannot adapt to sudden increases in vascular volume. A low platelet count predisposes patients to bleeding at IV site. | ||

| Preparation of patient | ||

| Decreases anxiety and promotes cooperation. | ||

| Use of a special IV gown facilitates safe removal of the gown. | ||

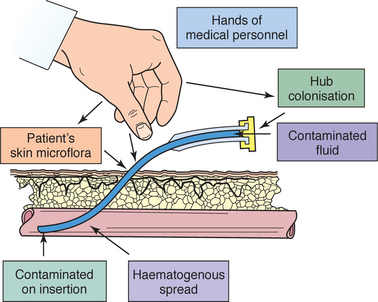

| Reduces transmission of microorganisms. | ||

| Preparing the IV solution | ||

|

13. Check IV solution and any prescribed additives, using the seven rights of drug administration (see Chapter 31). |

IV solutions are medications and should be carefully checked by two nurses to reduce risk of error. | |

| Solutions that are discoloured, contain particles or are expired are not to be used. Leaky bags present an opportunity for infection and must not be used. | ||

| Prevents bacteria from entering infusion equipment and bloodstream. | ||

| Close proximity of roller clamp to drip chamber allows more-accurate regulation of flow rate. Moving clamp to ‘off’ prevents accidental spillage of fluid and decreases amount of air bubbles when priming line. | ||

| 17 Remove protective sheath over IV-giving set tubing port on plastic IV solution bag (see illustration). For bottled IV solution, remove metal cap and metal and rubber disks beneath cap. | Provides access for insertion of infusion tubing into solution. | |

| Prevents contamination of solution from contaminated insertion spike. | ||

| Creates suction effects; fluid enters drip chamber to prevent air from entering tubing. | ||

| Large air bubbles can act as emboli. | ||

| Insertion of IV catheter/cannula | ||

| Reduces transmission of microorganisms. | ||

| Tourniquet should be tight enough to impede venous return but not occlude arterial flow. | ||

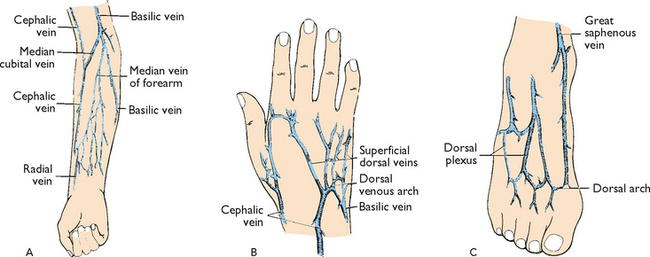

| Venepuncture should be performed distal to proximal, which increases the availability of other sites for future IV therapy. | ||

|

|

||

| Prevents interruption of venous flow while preparing IV site. Hair impedes venepuncture or adherence of dressing. Shaving can cause microabrasions and predispose patient to infection. | ||

| Povidone–iodine reduces skin surface bacteria; touching the cleaned area introduces organisms from nurse’s hand. Povidone–iodine must dry to be effective in reducing microbial counts. | ||

| Use of alcohol improves visualisation of the IV site and reduces the possible adverse effects of povidone–iodine. | ||

| If the patient is allergic to iodine, use 70% alcohol and allow to dry for 60 seconds. | ||

| Tourniquet time should be as short as possible. Avoid the use of a tourniquet in areas of compromised circulation. The tourniquet should not interfere with arterial blood flow to the extremity. | ||

| Places needle parallel to vein. When vein is punctured, risk of puncturing posterior vein wall is reduced. | ||

|

35. Gentle pressure is applied over the vein proximal to the entry site whilst the needle is removed from the catheter and disposed of into the sharps container. The needle should never be reinserted into the catheter as there is a risk of shearing off a part of the plastic catheter causing an embolus. |

Prevents risk of exposure to blood. | |

| Flushing will reaffirm patency and decrease risk of intra-cannula clotting. | ||

| Prompt connection of infusion set maintains patency of vein. Maintains sterility. | ||

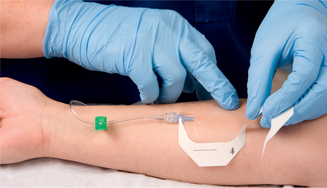

| Transparent dressing allows early observation for phlebitis. Securing the catheter and tubing prevents movement and tension on the device, reducing mechanical irritation and possible phlebitis or infection. It is advisable not to use the ‘chevron’ taping technique. | ||

| Tape on top of tape makes it easier to access hub/tubing junction. Securing loop of tubing reduces risk of dislodging catheter from accidental pull. | ||

| Critical decision point: No more than three attempts at inserting an IV should be made by a single nurse (check agency policy). | ||

| Permits venous flow and prevents clotting of vein and obstruction of flow of IV solution. | ||

| Critical decision point: Be sure to calculate rate so as not to infuse IV solution too rapidly or too slowly. | ||

| Documents when IV was inserted and when subsequent changes in IV cannula are required (check agency policy). | ||

| Reduces transmission of microorganisms and protects staff from injury. | ||

| Compression results in mechanical obstruction of vein. When IV catheter is patent, compression results in slowing or cessation of flow rate. No change in flow rate may indicate infiltration. | ||

| Provides continuous evaluation of type and amount of fluid delivered to patient. Hourly inspection prevents accidental fluid overload or inadequate infusion rate and identifies early incidence of vein inflammation or tissue damage. | ||

|

e. Inspect insertion site for absence of infiltration, phlebitis, or inflammation (Table 39-19). |

||

| IV fluids and additives are given to maintain or restore fluid and electrolyte balance. They can also cause unexpected effects, which can be serious. | ||

| RECORDING AND REPORTING | HOME CARE CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|

|

• Record patient’s response to IV fluid, amount infused in shift report; integrity and patency of system every hour or according to agency policy. • Report to oncoming nursing staff: type of fluid, flow rate, status of venepuncture site, amount of fluid remaining in present solution, expected time to hang next IV bag or bottle and any side effects. |

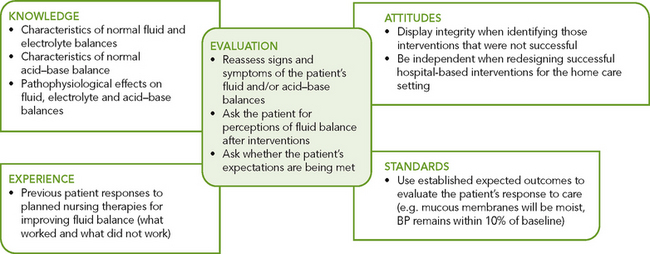

See Box 39-6.

• Teach caregiver to apply pressure with sterile gauze if catheter falls out and, if patient is on anticoagulant therapy, to tape several pieces of sterile gauze in place for at least 20 minutes or until bleeding stops. • Teach patient and caregiver to perform bed bath without getting IV tubing wet. For showering, the patient must insert hand and forearm into a plastic bag. Tape bag in place to ensure that IV site is completely covered. IV pumps are not designed to be located in moist bathroom environments during the bathing or showering process. Refer to relevant agency policy for management practices. • Teach patient and family to monitor fluid balance using household measuring devices. |