Chapter Eleven Peripheral vascular system and lymphatic system

INTRODUCTION

The vascular system consists of the blood vessels of the body. Blood vessels are tubes for transporting fluid, such as the blood or lymph. Arteries carry oxygenated blood from the heart to the peripheries. Arterial walls stretch during systole and recoil during diastole resulting in a palpable pulse. Veins carry deoxygenated blood to the heart. Because veins are low pressure vessels they do not usually produce pulsations. The exceptions are large veins such as the right internal carotid vein. Veins distend when there is an increase in intravascular volume. Any disease in the vascular system creates problems with delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the tissues or elimination of waste products from cellular metabolism. The lymphatic system consists of lymph nodes that filter lymphatic fluid. Body tissue fluids are drained first to lymphatic vessels then to lymphatic channels that empty into the bloodstream through lymphatic ducts in the thorax. Any disease in the lymphatic system results in tissue swelling which results from obstruction to lymph flow. Infection may cause enlarged, painful lymph nodes. Neoplasms may result in enlarged lymph nodes. In order to appreciate the impact of disease and trauma to these complex and dynamic systems you are advised to first review the structure and function of the cardiovascular system.

ARTERIES

The heart pumps freshly oxygenated blood through the arteries to all body tissues. The pumping heart makes this a high-pressure system. The artery walls are strong, tough and tense to withstand pressure demands. Arteries contain elastic fibres, which allow their walls to stretch with systole and recoil with diastole. Arteries also contain muscle fibres (vascular smooth muscle, or VSM), which control the amount of blood delivered to the tissues. The VSM contracts or dilates, which changes the diameter of the arteries to control the rate of blood flow.

Each heartbeat creates a pressure wave, which makes the arteries expand then recoil. It is the recoil that propels blood through like a wave. All arteries have this pressure wave, or pulse, throughout their length, but you can feel it only at body sites where the artery lies close to the skin and over a bone. The arteries described in the following sections are accessible to examination.

Carotid artery.

The carotid artery is palpated in the groove between the sternomastoid muscle and the trachea and is covered in Chapter 12 with the great vessels.

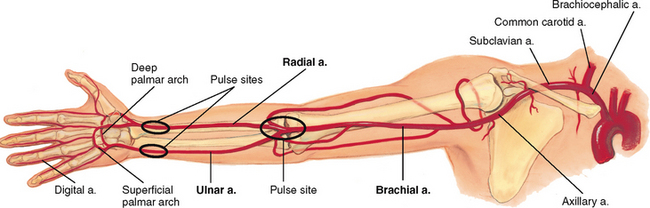

Arteries in the arm.

The major artery supplying the arm is the brachial artery, which runs in the biceps–triceps furrow of the upper arm and surfaces at the antecubital fossa in the elbow medial to the biceps tendon (Fig 11.1). Immediately below the elbow, the brachial artery bifurcates into the ulnar and radial arteries. These run distally and form two arches supplying the hand; these are called the superficial and deep palmar arches. The radial pulse lies just medial to the radius at the wrist; the ulnar artery runs parallel to the ulna, but it is deeper and often difficult to feel.

Arteries in the leg.

The major artery to the leg is the femoral artery, which passes under the inguinal ligament (Fig 11.2). The femoral artery travels down the thigh. At the lower thigh, it courses posteriorly; then it is termed the popliteal artery. Below the knee, the popliteal artery divides. The anterior tibial artery travels down the front of the leg on to the dorsum of the foot, where it becomes the dorsalis pedis. In the back of the leg, the posterior tibial artery travels down behind the medial malleolus and in the foot forms the plantar arteries.

The function of the arteries is to supply oxygen and essential nutrients to the tissues. Ischaemia is a deficient supply of oxygenated arterial blood to a tissue caused by obstruction of a blood vessel. A complete blockage leads to death of the distal tissue. A partial blockage creates an insufficient blood supply and the ischaemia may be apparent only at exercise when oxygen needs increase.

VEINS

The course of veins parallels that of arteries, but the body has more veins, and they lie closer to the skin surface. The following veins are accessible to examination.

Veins in the arm.

Each arm has two sets of veins: superficial and deep. The superficial veins are in the subcutaneous tissue and are responsible for most of the venous return.

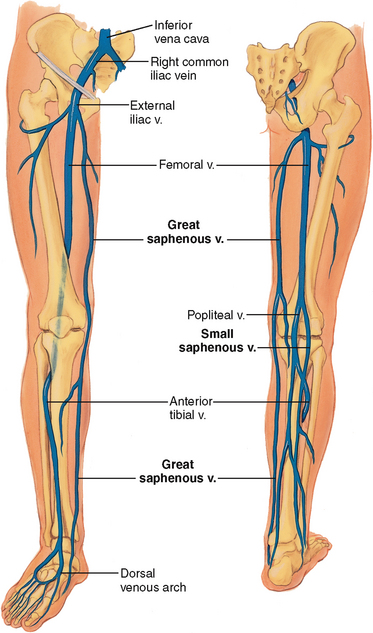

Veins in the leg.

The legs have three types of veins (Fig 11.3):

1. The deep veins run alongside the deep arteries and conduct most of the venous return from the legs. These are the femoral and popliteal veins. As long as these veins remain intact, the superficial veins can be excised without harming the circulation.

2. The superficial veins are the great and small saphenous veins. The great saphenous vein, inside the leg, starts at the medial side of the dorsum of the foot. You can see it ascend in front of the medial malleolus; then it crosses the tibia obliquely and ascends along the medial side of the thigh. The small saphenous vein, outside the leg, starts on the lateral side of the dorsum of the foot, ascends behind the lateral malleolus, up the back of the leg, where it joins the popliteal vein.

3. Perforators (not illustrated) are connecting veins that join the two sets. They also have one-way valves that direct blood from the superficial into the deep veins.

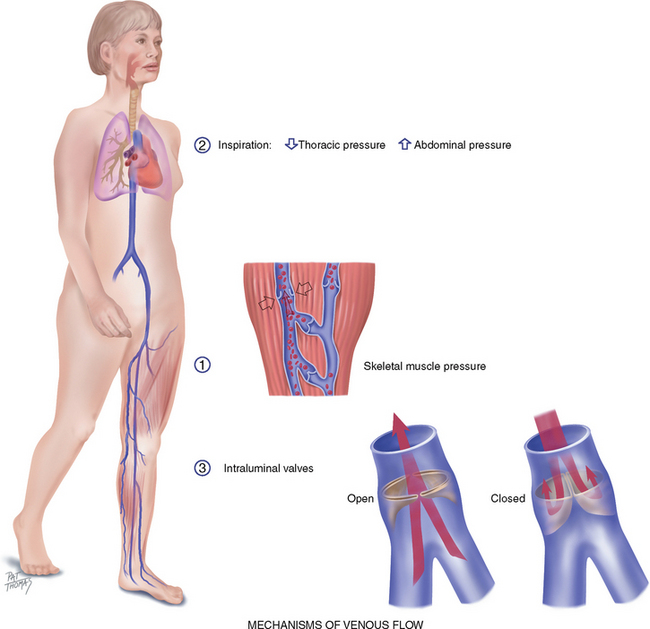

VENOUS FLOW

Veins drain the deoxygenated blood and its waste products from the tissues and return it to the heart. Unlike the arteries, veins are a low-pressure system. Because veins do not have a pump to generate their blood flow, the veins need a mechanism to keep blood moving (Fig 11.4). This is accomplished by (1) the contracting skeletal muscles that milk the blood proximally, back towards the heart; (2) the pressure gradient caused by breathing, in which inspiration makes the thoracic pressure decrease and the abdominal pressure increase; and (3) the one-way valves, called the intraluminal valves, which ensure unidirectional flow. Each valve is a paired semilunar pocket that opens towards the heart and closes tightly when filled to prevent backflow of blood.

In the legs, this mechanism is called the ‘calf pump’, or ‘peripheral heart’. While walking, the calf muscles alternately contract (systole) and relax (diastole). In the contraction phase, the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles squeeze the veins and direct the blood flow proximally. Because of the valves, venous blood flows just one way—towards the heart.

Besides the presence of intraluminal valves, venous structure differs from arterial structure. Because venous pressure is lower, the walls of the veins are thinner than those of the arteries. Veins have a larger diameter and are more distensible; they can expand and hold more blood when blood volume increases. This is a compensatory mechanism to reduce stress on the heart. Because of this ability to stretch, veins are called capacitance vessels.

Efficient venous return is dependent on contracting skeletal muscles, competent valves in the veins and a patent lumen. Problems with any of these three elements lead to venous stasis. At risk for venous disease are people who undergo prolonged standing, sitting or bed rest because they do not benefit from the milking action that walking accomplishes. Hypercoagulable states and vein wall trauma are other factors that increase risk for venous disease. Also, dilated and tortuous (varicose) veins create incompetent valves, wherein the lumen is so wide the valve cusps cannot approximate. This condition increases venous pressure, which further dilates the vein. Some people have a genetic predisposition to varicose veins, but obesity and pregnancy are increased risk factors.

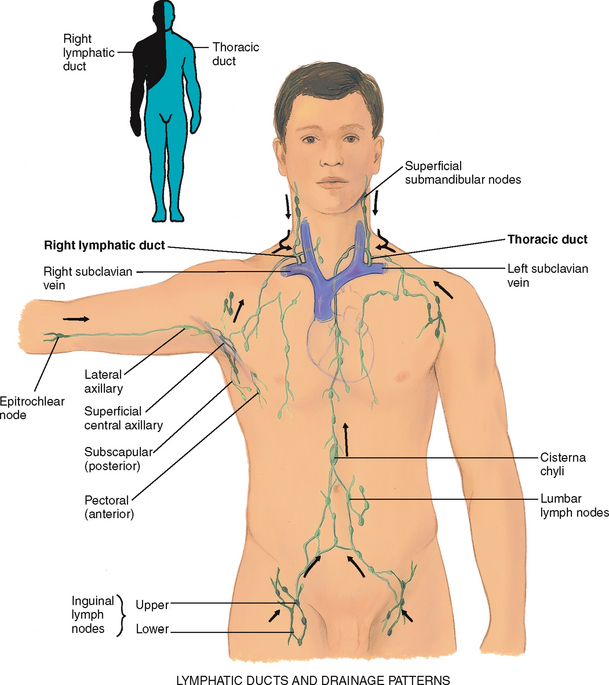

LYMPHATICS

The lymphatics form a completely separate vessel system, which retrieves excess fluid from the tissue spaces and returns it to the bloodstream (Fig 11.5). During circulation of the blood, somewhat more fluid leaves the capillaries than the veins can absorb. Without lymphatic drainage, fluid would build up in the interstitial spaces and produce oedema.

The vessels drain into two main trunks, which empty into the venous system at the subclavian veins (see Fig 11.5):

1. The right lymphatic duct empties into the right subclavian vein. It drains the right side of the head and neck, right arm, right side of thorax, right lung and pleura, right side of the heart and right upper section of the liver.

2. The thoracic duct drains the rest of the body. It empties into the left subclavian vein.

The functions of the lymphatic system are (1) to conserve fluid and plasma proteins that leak out of the capillaries, (2) to form a major part of the immune system that defends the body against disease and (3) to absorb lipids from the intestinal tract.

The processes of the immune system are complicated and not fully understood. The immune system detects and eliminates microorganisms that could be harmful to the body (pathogens), both those that come in from the environment and those arising from inside (abnormal or mutant cells). It accomplishes this by phagocytosis (digestion) of the substances by neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages and by production of specific antibodies or specific immune responses by the lymphocytes.

The lymphatic vessels have a unique structure. Lymphatic capillaries start as microscopic open-ended tubes, which siphon interstitial fluid. The capillaries converge to form vessels. The vessels, like veins, drain into larger ones. The vessels have valves, so flow is one way from the tissue spaces into the bloodstream. The many valves make the vessels look beaded. The flow of lymph is slow compared with that of the blood. Lymph flow is propelled by contracting skeletal muscles, by pressure changes secondary to breathing and by contraction of the vessel walls themselves.

Lymph nodes are small oval clumps of lymphatic tissue located at intervals along the vessels. Most nodes are arranged in groups, both deep and superficial, in the body. Nodes filter the fluid before it is returned to the bloodstream and filter out pathogens. The pathogens are exposed to lymphocytes in the lymph nodes. The lymphocytes mount an antigen-specific response to eliminate the pathogens. With local inflammation, the nodes in that area become swollen and tender.

The superficial groups of nodes are accessible to inspection and palpation and give clues to the status of the lymphatic system:

• Cervical nodes drain the head and neck and are described in Chapter 13.

• Axillary nodes drain the breast and upper arm. They are described in Chapter 27.

• The epitrochlear node is in the antecubital fossa and drains the hand and lower arm.

• The inguinal nodes in the groin drain most of the lymph from the legs, the external genitalia and the anterior abdominal wall.

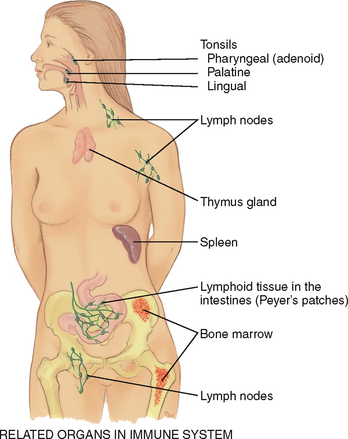

Related organs

The spleen, tonsils and thymus aid the lymphatic system (Fig 11.6). The spleen is located in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. It has four functions: (1) to destroy old red blood cells, (2) to produce antibodies, (3) to store red blood cells and (4) to filter microorganisms from the blood.

The tonsils (palatine, adenoid and lingual) are located in the throat at the entrance to the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts and respond to local inflammation.

The thymus is the flat, pink-grey gland located in the superior mediastinum behind the sternum and in front of the aorta. It is relatively large in the fetus and young child and atrophies after puberty. It is important in developing the T lymphocytes of the immune system in children, but it serves no function in adults. The T and B lymphocytes originate in the bone marrow and mature in the lymphoid tissue.

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Infants and children

The lymphatic system has the same function in children as in adults. Lymphoid tissue has a unique growth pattern compared with other body systems (Fig 11.7). It is well developed at birth and grows rapidly until age 10 or 11 years. By age 6 years, the lymphoid tissue reaches adult size; it surpasses adult size by puberty, then it slowly atrophies. It is possible that the excessive antigen stimulation in children causes the early rapid growth.

Lymph nodes are relatively large in children, and the superficial ones are often palpable even when the child is healthy. With infection, excessive swelling and hyperplasia occur. Enlarged tonsils are familiar signs in respiratory infections. The excessive lymphoid response may also account for the common childhood symptom of abdominal pain with seemingly unrelated problems such as upper respiratory infections. It is possible that the inflammation of mesenteric lymph nodes produce the abdominal pain.

The pregnant female

Hormonal changes cause vasodilatation and the resulting drop in blood pressure described in Chapter 12. The growing uterus obstructs drainage of the iliac veins and the inferior vena cava. This condition causes low blood flow and increases venous pressure. This, in turn, causes dependent oedema, varicosities in the legs and vulva and haemorrhoids.

Late adulthood (65+ years)

Peripheral blood vessels grow more rigid with age, resulting in a condition called arteriosclerosis. This condition produces the rise in systolic blood pressure discussed in Chapter 9. Do not confuse this process with another one, atherosclerosis, or the deposition of fatty plaques on the intima of the arteries.

Ageing produces a progressive enlargement of the intramuscular calf veins. Prolonged bed rest, prolonged sitting and heart failure increase the risk of deep venous thrombosis and subsequent pulmonary embolism. These conditions are common in ageing and also occur after myocardial infarction (MI). However, care for MI now includes early mobilisation and low-dose anticoagulant medication, which reduce the risk of pulmonary embolism.

Loss of lymphatic tissue leads to fewer numbers of lymph nodes and a decrease in the size of remaining nodes in people over 65.

SUBJECTIVE DATA

An accurate assessment requires the nurse to obtain a careful history from the patient of the symptoms they experience and to then undertake the clinical examination that articulates with what the patient has reported. This subjective data has been grouped under the following headings:

| Assessment guidelines | Clinical significance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

Peripheral vascular disease (PVD)–see Table 11.3. Claudication distance is the number of blocks walked or stairs climbed to produce pain. Confirm that claudication distance is the primary symptom impacting on mobility. |

|

| • Any recent change in exercise, a new exercise, increasing exercise? | Pain of musculoskeletal origin rather than vascular. |

| • What relieves this pain: dangling, walking, rubbing? Is the leg pain associated with any skin changes? | |

| • Is it associated with any change in sexual function (males)? | Aortoiliac occlusion is associated with impotence (Leriche’s syndrome). |

| • Any history of vascular problems, heart problems, diabetes, obesity, pregnancy, smoking, trauma, prolonged standing or bed rest? | |

| 2 Skin changes on arms or legs. Any skin changes in arms or legs? What colour: redness, pallor, blueness, brown discolourations? Hyper-pigmentation? | Hyperpigmentation, pallor/cyanosis and oedema are associated with venous stasis. |

| Coolness, pallor and hair loss are associated with arterial disease. Varicose veins. | |

| • Any leg sores or ulcers? Where on the leg? Any pain with the leg ulcer? | Leg ulcers occur with chronic arterial and chronic venous disease (see Table 11.4). |

| Oedema is bilateral when caused by a systemic problem such as heart failure or unilateral when the result of a local obstruction or inflammation. | |

| 4 Medications. What medications are you taking (e.g. oral contraceptives, hormone replacement)? |

TABLE 11.3 History profiles of pain of peripheral vascular disease

| Symptom analysis | Chronic arterial symptoms | Acute arterial symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Deep muscle pain, usually in calf, but may be lower on leg or dorsum of foot | Varies, distal to occlusion, may involve entire leg |

| Character | Intermittent claudication, feels like ‘cramp’, ‘numbness and tingling’, ‘feeling of cold’ | Throbbing |

| Onset and duration | Chronic pain, onset gradual after exertion | Sudden onset (within 1 hr) |

| Aggravating factors | ||

| Relieving factors | Rest (usually within 2 min (e.g. lying)). Dangling (severe involvement) | |

| Associated symptoms | Cool pale skin | Six Ps: pain, pallor, pulselessness, paraesthesia, poikilothermia (coldness), paralysis (indicates severe) |

| Those at risk | Adults over 65 years, more males than females, inherited predisposition, history of hypertension, smoking, diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia, obesity, vascular disease | History of vascular surgery; arterial invasive procedure; abdominal aneurysm (emboli); trauma, including injured arteries, chronic atrial fibrillation |

| Chronic venous symptoms | Acute venous symptoms | |

| Location | Calf, lower leg | Calf |

| Character | Aching, tiredness, feeling of fullness | Intense, sharp; deep muscle tender to touch |

| Onset and duration | Chronic pain, increases at end of day | Sudden onset (within 1 hr) |

| Aggravating factors | Prolonged standing, sitting | Pain may increase with sharp dorsifexion of foot |

| Relieving factors | Elevation, lying, walking | |

| Associated symptoms | Oedema, varicosities, weeping ulcers at ankles | Red, warm, swollen leg |

| Those at risk | Job with prolonged standing or sitting; obesity; pregnancy; prolonged bed rest; history of heart failure, varicosities or thrombophlebitis; veins crushed by trauma or surgery |

OBJECTIVE DATA

The focus of the clinical examination is to examine the patient for clinical signs that support or are in addition to the patient’s report of symptoms. In particular, assessment of the peripheral vascular system is aimed at finding out risk factors for skin breakdown, pain, immobility and changes to everyday activity. Patient preparation is the essential first step.

TABLE 11.4 Peripheral vascular disease in the legs

| Chronic arterial insuffciency |

|

| Arteriosclerosis—ischaemic ulcer |

Build-up of fatty plaques on inner layer (intima) (atherosclerosis) plus hardening and calcifcation of arterial wall (arteriosclerosis). S: Deep muscle pain in calf or foot, claudication (pain with walking), pain at rest indicates worsening of condition. O: Coolness, pallor, elevational pallor and dependent rubor; diminished pulses; systolic bruits; trophic skin; signs of malnutrition (thin, shiny skin, thick-ridged nails, absence of hair, atrophy of muscles); xanthoma formation; distal gangrene. Ulcers occur at toes, metatarsal heads, heels, lateral ankle, and are characterised by pale ischaemic base, well-defined edges and no bleeding. Diabetes hastens changes described above, with generalised dysfunction in all arterial areas: peripheral, coronary, cerebral, retina, kidney. Peripheral involvement is associated with diabetic neuropathy and local infection. |

| Chronic venous insufficiency |

|

| Venous (stasis) ulcer |

After acute deep vein thrombosis or chronic incompetent valves in deep veins. S: Aching pain in calf or lower leg, worse at end of the day, worse with prolonged standing or sitting. O: Firm brawny oedema; coarse, thickened skin; pulses normal; brown pigment discolouration; petechiae; dermatitis. Venous stasis causes increased venous pressure, which then causes red blood cells (RBCs) to leak out of veins and into the skin. As these RBCs break down, they leave haemosiderin (iron deposits) behind, which are the brown pigment deposits. Ulcers occur at medial malleolus and are characterised by bleeding, uneven edges. |

| Chronic venous disease |

|

| Superficial varicose veins |

Incompetent valves permit reflux of blood, producing dilated, tortuous veins. Unremitting hydrostatic pressure causes distal valves to be incompetent and causes worsening of the varicosity. Over age 45 years, occurrence is three times more common in women than in men. S: Aching, heaviness in calf, easy fatiguability, night leg or foot cramps. |

| Acute venous disease |

|

| Deep vein thrombophlebitis |

A deep vein is occluded by a thrombus, causing inflammation, blocked venous return, cyanosis and oedema. Cause may be prolonged bed rest; history of varicose veins; trauma; infection; cancer; and, in younger women, the use of oral oestrogenic contraceptives (Dockery, 1997). S: Sudden onset of intense, sharp, deep muscle pain, may increase with sharp dorsiflexion of foot. O: Increased warmth; swelling (to compare swelling, observe the usual shoe size as in above photo); redness; dependent cyanosis is mild or may be absent; tender to palpation; Homans’ sign is present only in few cases. Requires emergency referral because of risk of pulmonary embolism. |

S, Subjective data; O, objective data.

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

|---|---|

During a complete physical examination, examine the arms at the very beginning when you are checking the vital signs—the person is sitting. Examine the legs directly after the abdominal examination while the person is still supine. Then stand the person up to evaluate the leg veins. Examination of the arms and legs includes peripheral vascular characteristics (described below), the skin (Ch 17), musculoskeletal findings (Ch 15) and neurological findings (Ch 22). A method of integrating these steps is discussed in Chapter 29.

Room temperature should be about 22°C and draughtless to prevent vasodilatation or vasoconstriction. Use inspection and palpation. Compare your findings with the opposite extremity. |

| Procedures and normal findings | Abnormal findings and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| INSPECT AND PALPATE THE ARMS | |

| Lift both of the person’s hands in your hands. Inspect, then turn the person’s hands over, noting colour of skin and nailbeds; temperature, texture and turgor of skin; and the presence of any lesions, oedema or clubbing. Use the profile sign (viewing the finger from the side) to detect early clubbing. The normal nail bed angle is 160°. (See Ch 17 for a full discussion of skin colour, lesions and clubbing.) | Flattening of angle and clubbing (diffuse enlargement of terminal phalanges) occur with congenital cyanotic heart disease and cardiopulmonary disease. |

| With the person’s hands near the level of their heart, check capillary refill. This is an index of peripheral perfusion and cardiac output. Depress and blanch the nail beds; release and note the time for colour return. Usually, the vessels refill within a fraction of a second. Consider it normal if the colour returns in less than 1 or 2 seconds. Note conditions that can skew your findings: a cool room, decreased body temperature, cigarette smoking, peripheral oedema and anaemia. | Refill lasting more than 1 or 2 seconds signifies vasoconstriction or decreased cardiac output (hypovolaemia, heart failure, shock). The hands are cold, clammy and pale. |

| The two arms should be symmetrical in size. | Oedema of upper extremities occurs when lymphatic drainage is obstructed, which may occur after breast surgery (see Table 11.2). |

| Note the presence of any scars on hands and arms. Many occur normally with usual childhood abrasions or with occupations involving hand tools. | Needle tracks occur with IV drug use; linear scars in wrists may signify past self-inflicted injury. |

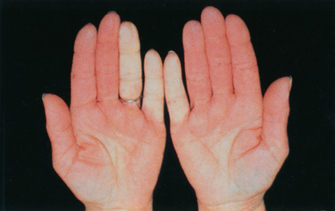

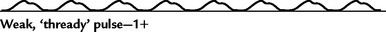

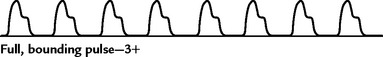

| Palpate both radial pulses, noting rate, rhythm, elasticity of vessel wall and equal force (Fig 11.8). Grade the force (amplitude) on a three-point scale: | |

| Full, bounding pulse (3+) occurs with hyperkinetic states (exercise, anxiety, fever), anaemia and hyperthyroidism. | |

| Weak, ‘thready’ pulse occurs with shock and peripheral arterial disease. See Table 11.1 for illustrations of these and irregular pulse rhythms. | |

| It is not usually necessary to palpate the ulnar pulses. If indicated, palpate along the medial side of the inner forearm (Fig 11.9), although the ulnar pulses are often not palpable in the normal person. | |

| Palpate the brachial pulses–their force should be equal bilaterally (Fig 11.10). | |

| INSPECT AND PALPATE THE LEGS | |

| Uncover the legs while keeping the genitalia draped. Inspect both legs together, noting skin colour, hair distribution, venous pattern, size (swelling or atrophy) and any skin lesions or ulcers. | Pallor with vasoconstriction; erythema with vasodilatation; cyanosis. |

| Normally hair covers the legs. Even if leg hair is shaved, you will still note hair on the dorsa of the toes. | Malnutrition: thin, shiny atrophic skin, thick-ridged nails, loss of hair, ulcers, gangrene. Malnutrition, pallor and coolness occur with arterial insufficiency. |

| The venous pattern is normally fat and barely visible. Note obvious varicosi-ties, although these are best assessed while standing. | |

| Both legs should be symmetrical in size without any swelling or atrophy. If the lower legs look asymmetrical or if deep venous thrombosis is suspected, measure the calf circumference with a tape measure (Fig 11.11). Measure at the widest point, taking care to measure the other leg in exactly the same place, i.e. the same number of centimetres down from the patella or other landmark. If lymphoedema is suspected, measure also at the ankle, knee and thigh. Record your findings in centimetres. | |

| Asymmetry of 1 to 3 cm occurs with mild lymphoedema; 3 to 5 cm with moderate lymphoedema; and more than 5 cm with severe lymphoedema (see Table 11.2). | |

| In the presence of skin discolouration, skin ulcers or gangrene, note the size and the exact location. | Brown discolouration occurs with chronic venous stasis due to haemosiderin deposits from red blood cell degradation. Venous ulcers occur usually at medial malleolus because of bacterial invasion of poorly drained tissues (see Table 11.4). With arterial deficit, ulcers occur on tips of toes, metatarsal heads and lateral malleoli. |

| Palpate for temperature along the legs down to the feet, comparing symmetrical spots (Fig 11.12). The skin should be warm and equal bilaterally. Bilateral cool feet may be due to environmental factors such as cool room temperature, apprehension and cigarette smoking. If any increase in temperature is present higher up the leg, note if it is gradual or abrupt. | A unilateral cool foot or leg or a sudden temperature drop as you move down the leg occurs with arterial deficit. |

| Flex the person’s knee, then gently compress the gastrocnemius (calf) muscle anteriorly against the tibia; no tenderness should be present. Or you may sharply dorsifex the foot towards the tibia. Flexing the knee first exerts pressure on the posterior tibial vein. Normally this does not cause pain. | Calf pain with these manoeuvres is a positive homans’ sign, which occurs in about 35% of cases of deep vein thrombosis. It is not specific for this condition because it occurs also with superfcial phlebitis, Achilles tendinitis, gastrocnemius and plantar muscle injury and lumbosacral disorders. |

| Palpate these peripheral arteries in both legs: femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial. Grade the force on the 4-point scale. Locate the femoral arteries just below the inguinal ligament halfway between the pubis and anterior superior iliac spines (Fig 11.13). The simplest method of locating the femoral artery is to recall that the femoral artery is always located at a 45° angle to the patient’s umbilicus. Press frmly and then slowly release, noting the pulse tap under your fingertips. | |

| The popliteal pulse is a more diffuse pulse and can be difficult to localise. With the leg extended but relaxed, anchor your thumbs on the knee, and curl your fingers around into the popliteal fossa (Fig 11.14). Press your fingers forwards hard to compress the artery against the bone (the lower edge of the femur or the upper edge of the tibia). Often it is just lateral to the medial tendon. | |

| If you have difficulty, turn the person prone and lift up the lower leg (Fig 11.15). Let the leg relax against your arm and press in deeply with your two thumbs. Often a normal popliteal pulse is impossible to palpate. | |

| For the posterior tibial pulse, curve your fingers around the medial malleolus (Fig 11.16). You will feel the tapping right behind it in the groove between the malleolus and the Achilles tendon. If you cannot, try passive dorsiflexion of the foot to make the pulse more accessible. | |

| The dorsalis pedis pulse requires a very light touch. Normally it is just lateral to and parallel with the extensor tendon of the big toe (Fig 11.17). Do not mistake the pulse in your own fingertips for that of the person. | |

In adults over 45 years, occasionally either the dorsalis pedis or the posterior tibial pulse may be hard to fnd, but not both on the same foot. Check for pretibial oedema. Firmly depress the skin over the tibia or the medial malleolus for 5 seconds and release (Fig 11.18, A). Normally, your fnger should leave no indentation, although a pit is commonly seen if the person has been standing all day or during pregnancy. |

Bilateral, dependent, pitting oedema occurs with heart failure, diabetic neuro pathy and hepatic cirrhosis (Fig. 11.18, B). |

If pitting oedema is present, grade it on the following scale: 1+ Mild pitting, slight indentation, no perceptible swelling of the leg 2+ Moderate pitting, indentation subsides rapidly 3+ Deep pitting, indentation remains for a short time, leg looks swollen 4+ Very deep pitting, indentation lasts a long time, leg is very swollen. This scale is subjective and qualitative. The amount of pressure used is arbitrary, as is the judgment of the depth and rate of pitting. Clinicians need a standard quantified scale to ensure consistent clinical measurements and management. Many classify the oedema by measuring the depth of the pitting in centimetres (1+ = 1 cm, 2+ = 2 cm, etc.) Some measure with a millimetre scale, others by an increase in weight; still others try to quantify the rate of time the pitting remains after release of pressure. Check with your institution to determine a consistently used scale. |

Unilateral oedema occurs with occlusion of a deep vein. Unilateral or bilateral oedema occurs with lymphatic obstruction. With these factors, it is ‘brawny’ or nonpitting and feels hard to the touch. |

| Ask the person to stand so that you can assess the venous system. Note any visible, dilated and tortuous veins. | Varicosities occur in the saphenous veins (see Table 11.4). |

| Colour changes | |

| If you suspect an arterial deficit, raise the legs about 30 cm off the table and ask the person to wag the feet for about 30 seconds to drain off venous blood (Fig 11.19). The skin colour now reflects only the contribution of arterial blood. A light-skinned person’s feet normally will look a little pale but still should be pink. A dark-skinned person’s feet are more difficult to evaluate, but the soles should reveal extreme colour change. | Elevational pallor (marked) indicates arterial insufficiency. |

| Now have the person sit up with the legs over the side of the table (Fig 11.20). Compare the colour of both feet. Note the time it takes for colour to return to the feet. Normally, this is 10 seconds or less. Note also the time it takes for the superfcial veins around the feet to fill—the normal time is about 15 seconds. This test is unreliable if the person has concomitant venous disease with incompetent valves. | |

| Test the lower legs for strength (see Ch 15). Test the lower legs for sensation (see Ch 22). | |

| The Doppler | |

| Use this device to detect a weak peripheral pulse, to monitor blood pressure in infants or children or to measure a low blood pressure or blood pressure in a lower extremity (Fig 11.21). The Doppler magnifes pulsatile sounds from the heart and blood vessels. Position the person supine, with the legs externally rotated so you can reach the medial ankles easily. Place a drop of coupling gel on the end of the handheld transducer. Place the transducer over a pulse site, swivelled at a 45° angle. Apply very light pressure; locate the pulse site by the swishing, whooshing sound. | |

| DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS | |

| Infants and children | |

| Transient acrocyanosis and skin mottling at birth are discussed in Chapter 17. Pulse force should be normal and symmetrical. Pulse force should also be the same in the upper and lower extremities. | Acrocyanosis is persistent, painless, symmetrical cyanosis of the hands, feet or face caused by vasospasm of the small vessels of the skin in response to cold (Merck Manual, 2008). Weak pulses occur with vasoconstriction of diminished cardiac output. Full, bounding pulses occur with patent ductus arteriosus as a result of the large left-to-right shunt. Diminished or absent femoral pulses while upper extremity pulses are normal suggest coarctation of aorta. |

| The pregnant female | |

| Expect diffuse bilateral pitting oedema in the lower extremities, especially at the end of the day and into the third trimester. Varicose veins in the legs are also common in the third trimester. | |

| The adult over 65 years | |

| The dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulse may become more difficult to fnd. Trophic changes associated with arterial insufficiency (thin, shiny skin, thick-ridged nails, loss of hair on lower legs) also occur normally with ageing. | |

| FURTHER SUBJECTIVE AND OBJECTIVE ASSESSMENT FOR ADVANCED PRACTICE | |

| The assessments that are described in the following sections require advanced skill and scope of practice. Nurses working in specialist cardiac units and nurses working in community centres need to develop these skills. | |

| Subjective data | |

| Lymph node enlargement. Any ‘swollen glands’ (lumps)? Where in the body? How long have you had them? Lymph node enlargement. Any ‘swollen glands’ (lumps)? Where in the body? How long have you had them? |

Enlarged lymph nodes occur with infection, malignancies and immunological diseases. |

| Inspect and palpate the arms | |

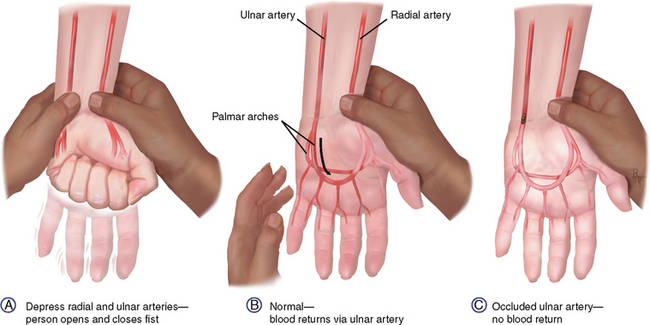

| In addition to the techniques related to inspection and palpation of the arms described previously, the modified Allen test will give you additional data on peripheral circulation of the arms. | |

| Check the epitrochlear lymph node in the depression above and behind the medial condyle of the humerus. Do this by ‘shaking hands’ with the person and reaching your other hand under the person’s elbow to the groove between the biceps and triceps muscles, above the medial epicondyle (Fig 11.22). This node is not normally palpable. | An enlarged epitrochlear node occurs with infection of the hand or forearm. |

| The modified Allen test is used to evaluate the adequacy of collateral circulation prior to cannulating the radial artery (Fig 11.23). A, Firmly occlude both the ulnar and the radial arteries of one hand while the person makes a fst several times. This causes the hand to blanch. B, Ask the person to open the hand without hyperextending it; then release pressure on the ulnar artery while maintaining pressure on the radial artery. Adequate circulation is suggested by a return to the hand’s normal colour in approximately 2 to 5 seconds. This test is valid and useful (Kohonen, Teerenhovi, Terho et al, 2007). Its limitations include that it is relatively crude and subject to error—that is, you must occlude both arteries uniformly with frm occlusive pressure for the test to be accurate (Fuhrman et al, 1992; Gelberman and Blasingame, 1981). Further, when compared to the use of Doppler, the latter yields greater accuracy in clinical practice (Ronald, Patel, Dunning, 2005). | C, Pallor persists or a sluggish return to colour suggests occlusion of the collateral arterial fow. Avoid radial artery cannulation until adequate circulation is shown. |

| Inspect and palpate the legs | |

| In addition to the techniques related to inspection and palpation of the legs described previously, palpation of inguinal lymph nodes will extend patient assessment data for the advanced practice nurse. The manual compression test and the ankle brachial index will give you additional data on peripheral circulation of the legs. | |

| Palpate the inguinal lymph nodes. It is not unusual to fnd palpable nodes that are small (1 cm or less), movable and nontender. | Enlarged nodes, tender or fxed in area. |

| Manual compression test | |

| While the person is still standing, test the length of the varicose vein to determine whether its valves are competent (Fig 11.24). Place one hand on the lower part of the varicose vein, and compress the vein with your other hand about 15 to 20 cm higher. | |

| The ankle-brachial index (ABI) | |

| Use of the Doppler is a highly specific, noninvasive and readily available way to determine the extent of peripheral vascular disease. Apply a regular arm blood pressure cuff above the ankle and determine the systolic pressure in either the posterior tibial or the dorsalis pedis artery. Then divide that fgure by the systolic pressure of the brachial artery. | |

| (Take brachial systolic pressures in both arms and use the higher measurement.) The normal ankle pressure is slightly greater than or equal to the brachial pressure; thus, a normal ABI is usually 1.0 to 1.2. For example, in people with diabetes mellitus, the ABI may be less reliable because of calcifcation (which makes their arteries noncompressible) and may give a falsely high measurement (Khan et al, 2006). | An ABI of 90% or less indicates the presence of peripheral arterial disease: |

| Infants and children | |

| Palpable lymph nodes often occur in healthy infants and children. They are small, frm, mobile and nontender. They may be the sequelae of past infection, such as inguinal nodes from a nappy rash or cervical nodes from a respiratory infection. Vaccinations can also produce local lymphadenopathy. Note characteristics of any palpable nodes and whether they are local or generalised. | Enlarged, warm, tender nodes indicate current infection. Look for source of infection. |

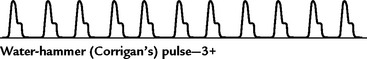

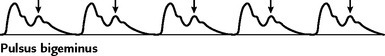

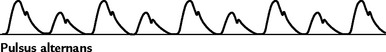

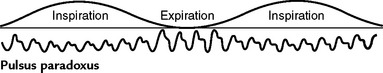

TABLE 11.1 Variations in arterial pulse

| Description | Associated with |

|---|---|

|

|

| Decreased cardiac output; peripheral arterial disease; aortic valve stenosis | |

|

|

| Hyperkinetic states (exercise, anxiety, fever), anaemia, hyperthyroidism | |

|

|

| Aortic valve regurgitation; patent ductus arteriosus | |

|

|

| Conduction disturbance (e.g. premature ventricular contraction, premature atrial contraction) | |

|

|

| Heart failure | |

|

|

| Any condition that blocks venous return to the right side of the heart, or blocks left ventricular filling (e.g. cardiac tamponade; constrictive pericarditis, pulmonary embolism) | |

|

|

| Aortic valve stenosis plus regurgitation |

TABLE 11.2 Peripheral vascular disease in the arms

Promoting a healthy lifestyle Foot care

Take care of your feet!

Foot problems often herald more serious health conditions such as arthritis, diabetes and nerve or circulatory disorders. Healthcare providers should not only remember to examine the feet for common foot problems but also be prepared to explain what ‘good’ foot care really means. Too often healthcare providers will advise good foot care but do not take the time to explain what ‘good’ foot care entails.

‘Good’ foot care entails the following:

• Checking your feet every day.

• Toenails should be kept trimmed, straight across, and filed at the edges with an emery board or nail file.

• Keeping the blood flowing to your feet.

• Wearing shoes that fit and are comfortable.

For more information on foot care:

American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society: http://www.aofas.org

American Podiatric Medical Association: http://www.apma.org

Australian Podiatry Association: http://www.podiatry.asn.au/

New Zealand Society of Podiatrists: http://www.podiatry.org.nz/

DOCUMENTATION AND CRITICAL THINKING

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY EXAMPLE

Mr James K. is a 43-year-old married local council employee, admitted to hospital today for ‘bypass surgery tomorrow to fix my aorta and these dark-coloured toes’.

Subjective

6 yrs ago: motorcycle accident with handle bars jammed into groin. Treated and discharged from local hospital. No apparent injury, although the cardiac surgeon now thinks accident may have precipitated present stenosis of aorta.

1 yr ago: radiating pain in right calf on walking 0.5 km. Pain relieved with rest.

3 months ago: problems with sex, unable to maintain erection during intercourse.

1 month ago: leg pain present after walking two blocks. Numbness and tingling in right foot and calf. Tips of three toes on right foot look dusky in colour. Referred to a surgeon.

Present: leg pain at rest, constant and severe, worse at night, partially relieved by dangling legs over side of bed.

History: no history of heart or vessel disease or hypertension or diabetes or obesity.

Personal habits: Current smoker: 1 packet per day. History of 69 pack years; as defined by British Thoracic Society (1997). Walking is part of occupation, although has been driving the local council truck last 3 months due to leg pain. Not currently on medication.

Objective

Inspection: Lower extremity size = bilaterally with no swelling or atrophy. No varicosities. Colour L leg pink, R leg pink when supine, but marked pallor to R foot on elevation. Black gangrene at tips of R 2nd, 3rd, 4th toes. Leg hair present but absent on involved toes.

Palpation: R foot cool and temperature progressively warms on palpation up R leg.

Pulses: Femorals, both 1+; popliteals, both 0; posterior tibial, both 0 but present with Doppler; dorsalis pedis both 0, but left dorsalis pedis is present with Doppler, and right is not present with Doppler.

Diagnostic studies showed stenosis of abdominal aorta below kidneys.

ABNORMAL FINDINGS FOR ADVANCED PRACTICE

TABLE 11.5 Peripheral artery disease

|

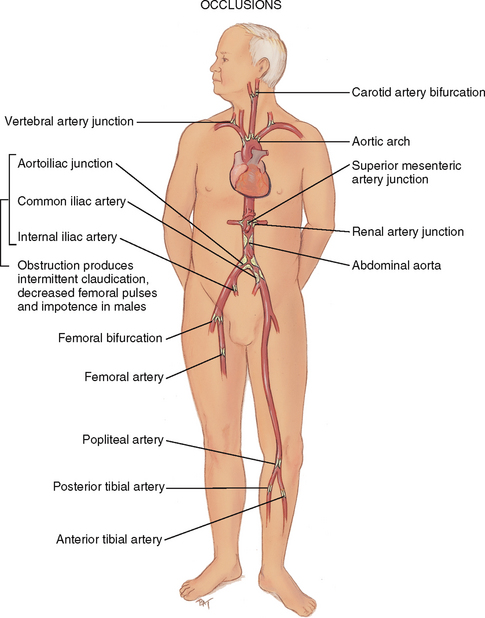

| Occlusions |

| Occlusions in the arteries are caused by atherosclerosis, which is the chronic gradual build-up of (in order) fatty streaks, fib roid plaque, calcification of the vessel wall and thrombus formation. This reduces blood flow with vital oxygen and nutrients. Risk factors fo r atherosclerosis include obesity, cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, elevated serum cholesterol, sedentary lifestyle and family history of hyperlipidaemia. |

|

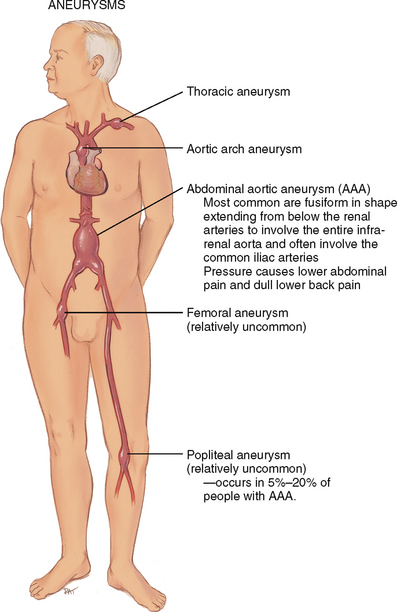

| Aneurysms |

| An aneurysm is a sac formed by dilation in the artery wall. Atherosclerosis weakens the middle layer (media) of the vessel wall. This stretches the inner and outer layers (intima and adventitia), and the effect of blood pressure creates the balloon enlargement. The most common site is the aorta, and the most common cause is atherosclerosis. The incidence increases rapidly in men over 55 years and women over 70 years; the overall occurrence is four to five times more frequent in men. |

Bowling JCR, Dowd PM. Raynaud’s disease. Lancet. 2003;361:2078–2080.

British Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1997;52(Suppl 5):S1–S28.

Brown J. A clinically useful method for evaluating lymphoedema. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2003;8:35–38.

Chant T. Peripheral vascular disease. Prim Health Care. 2004;14:29–34.

Dockery GL. Cutaneous disorders of the lower extremity. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997.

Fahey VA. Vascular nursing, 4th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2004.

Fecerman DG, et al. Peripheral arterial disease. Postgrad Med. 2006;119:21–27.

Fox JC, Otarodifard K, Deavers M. Diagnostic and therapeutic keys to deep vein thrombosis. Emerg Med. 2006;38:14–20.

Fuhrman TM, et al. Evaluation of collateral circulation of the hand. J Clin Monit. 1992;8:28–32.

Gelberman RH, Blasingame JP. The timed Allen test. J Trauma. 1981;21:477–479.

Gould SD, Spandorfer JM. Unilateral leg swelling: clues to cause and ways to treat. Patient Care. 2005;39:49–55.

Gupta A. Intermittent claudication. Geriatr Med. 2006;36:22–25.

Khan NA, et al. Does the clinical examination predict lower extremity peripheral arterial disease? JAMA. 2006;295:536–545.

Kohonen M, Teerenhovi O, Terho T, et al. Is the Allen test reliable enough? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32:902–905.

McDermott MM. Ankle brachial index as a predictor of outcomes in peripheral arterial disease. J Lab Clin Med. 1999;133:33–40.

Merck Manual, 2008. Available at http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec07/ch080/ch080b.html.

Morrell RM, et al. Breast cancer–related lymphoedema. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1480–1484.

Oka RK. Peripheral arterial disease in older adults. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;21:515–520.

Olson KWP, Treat-Jacobson D. Symptoms of peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Nurs. 2004;22:72–77.

Perrodin JP. Noninvasive assessment of the peripheral vascular system: Handheld Doppler, oscillometry, and air plethysmography. Acute Care Perspect. 2001;10:13–15.

Reilly A, Snyder B. Raynaud phenomenon. Am J Nurs. 2005;105:56–66.

Rice KL. How to measure ankle/brachial index. Nursing 2005. 2005;35:56–57.

Ronald A, Patel A, Dunning J. Is the Allen’s test adequate to safely confirm that a radial artery may be harvested for coronary arterial bypass grafting? Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg. 2005;4:332–340.

Sieggreen M. A contemporary approach to peripheral arterial disease. Nurse Pract. 2006;31:14–26.

Sieggreen M. Lower extremity arterial and venous ulcers. Nurs Clin North Am. 2005;40:391–410.

Sieggreen MY, Line RA. Arterial insufficiency and ulceration. Nurse Pract. 2004;29:46–52.

Slack CB, Landis CA. Improving outcomes for restless legs syndrome. Nurse Pract. 2006;31:27–37.

Stevens LM. Peripheral arterial disease. JAMA. 2006;295(5):584.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for peripheral arterial disease: Recommendation statement. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:497–500.

Urbano FL. Homans’ sign in the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. Hosp Physician. 2001;37:22–24.

Welsh JR, Arzouman JM, Holm K. Nurses’ assessment and documentation of peripheral oedema. Clin Nurs Spec. 1996;10:7–10.

Wigley FM. Raynaud’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1001–1007.

Williams AF. How to recognize lymphooedema. Pract Nurs. 2006;17:228–232.

Zipes D, et al. Braunwald’s heart disease: A textbook of cardiovascular medicine, 7th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2005.