Chapter Seventeen Skin, hair and nails

INTRODUCTION

Think of the skin as the body’s largest organ system—it covers 6.01 square metres of surface area in the average adult. The skin is the sentry that guards the body from environmental stresses (e.g. trauma, pathogens, dirt) and adapts it to other environmental influences (e.g. heat, cold). We assess the skin in nearly every area of health assessment. As nutrition is very important to the health of the skin, hair and nails please also refer to Chapter 16.

SKIN

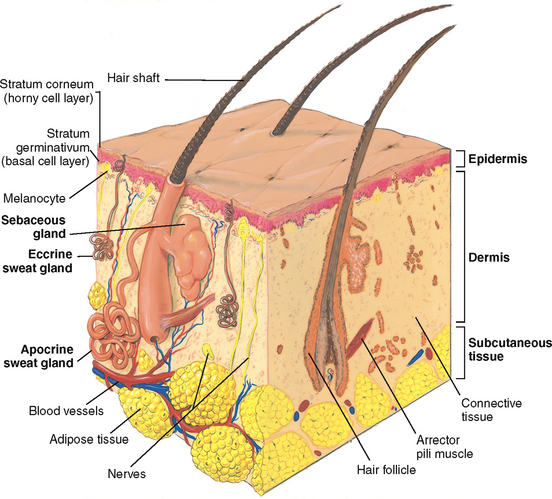

The skin has two layers—the outer highly differentiated epidermis and the inner supportive dermis (Fig 17.1). Beneath these layers is a third layer, the subcutaneous layer of adipose tissue.

Epidermis

The epidermis is thin but tough. Its cells are bound tightly together into sheets that form a rugged protective barrier. It is stratified into several zones. The inner stratum germinativum, or basal cell layer, forms new skin cells. Their major ingredient is the tough, fibrous protein keratin. The melanocytes interspersed along this layer produce the pigment melanin, which gives brown tones to the skin and hair. All people have the same number of melanocytes; however, the amount of melanin they produce varies with genetic, hormonal and environmental influences.

From the basal layer the new cells migrate up and flatten into the stratum corneum. This outer horny cell layer consists of dead keratinised cells that are interwoven and closely packed. The cells are constantly being shed, or desquamated, and are replaced with new cells from below. The epidermis is completely replaced every 4 weeks. In fact, each person sheds about ½ kg of skin each year.

The epidermis is uniformly thin except on the surfaces that are exposed to friction, such as the palms and the soles. On these surfaces, skin is thicker because of work and weight bearing. The epidermis is avascular; it is nourished by blood vessels in the dermis below.

Skin colour is derived from three sources: (1) mainly from the brown pigment melanin, (2) also from the yellow-orange tones of the pigment carotene and (3) from the red-purple tones in the underlying vascular bed. All people have skin of varying shades of brown, yellow and red; the relative proportion of these shades affects the prevailing colour. Skin colour is further modified by the thickness of the skin and by the presence of oedema.

Dermis

The dermis is the inner supportive layer consisting mostly of connective tissue, or collagen. This is the tough, fibrous protein that enables the skin to resist tearing. The dermis also has resilient elastic tissue that allows the skin to stretch with body movements. The nerves, sensory receptors, blood vessels and lymphatics lie in the dermis. Also, appendages from the epidermis—such as the hair follicles, sebaceous glands and sweat glands—are embedded in the dermis.

Subcutaneous layer

The subcutaneous layer is adipose tissue, which is made up of lobules of fat cells. The subcutaneous tissue stores fat for energy, provides insulation for temperature control and aids in protection by its soft cushioning effect. Also, the loose subcutaneous layer gives skin its increased mobility over structures underneath.

EPIDERMAL APPENDAGES

These structures are formed by a tubular invagination of the epidermis down into the underlying dermis.

Hair

Hair is vestigial for humans; it is no longer needed for protection from cold or trauma. However, hair is highly significant in most cultures for its cosmetic and psychological meaning (see Cultural and social considerations below).

Hairs are threads of keratin. The hair shaft is the visible projecting part, and the root is below the surface embedded in the follicle. At the root the bulb matrix is the expanded area where new cells are produced at a high rate. Hair growth is cyclical, with active and resting phases. Each follicle functions independently so that while some hairs are resting, others are growing. Around the hair follicle are the muscular arrector pili, which contract and elevate the hair so that it resembles ‘goose flesh’ when the skin is exposed to cold or in emotional states.

People have two types of hair. Fine, faint vellus hair covers most of the body (except the palms and soles, the dorsa of the distal parts of the fingers, the umbilicus, the glans penis and inside the labia). The other type is terminal hair, the darker thicker hair that grows on the scalp and eyebrows and, after puberty, on the axillae, pubic area and the face and chest in the male.

Sebaceous glands

These glands produce a protective lipid substance, sebum, which is secreted through the hair follicles. Sebum oils and lubricates the skin and hair and forms an emulsion with water that retards water loss from the skin. (Dry skin results from loss of water, not directly from loss of oil.) Sebaceous glands are everywhere except on the palms and soles. They are most abundant in the scalp, forehead, face and chin.

Sweat glands

There are two types. The eccrine glands are coiled tubules that open directly onto the skin surface and produce a dilute saline solution called sweat. The evaporation of sweat reduces body temperature. Eccrine glands are widely distributed through the body and are mature in the 2-month-old infant.

The apocrine glands produce a thick, milky secretion and open into the hair follicles. They are located mainly in the axillae, anogenital area, nipples and navel and are vestigial in humans. They become active during puberty, and secretion occurs with emotional and sexual stimulation. Bacterial flora residing on the skin surface react with apocrine sweat to produce a characteristic musky body odour. The functioning of apocrine glands decreases in the older adult.

Nails

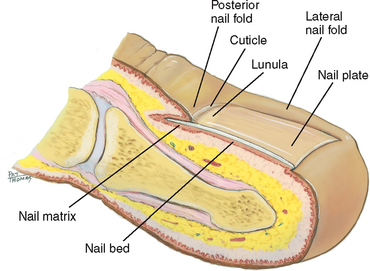

The nails are hard plates of keratin on the dorsal edges of the fingers and toes (Fig 17.2). The nail plate is clear, with fine longitudinal ridges that become prominent in ageing. Nails take their pink colour from the underlying nail bed of highly vascular epithelial cells. The lunula is the white opaque semilunar area at the proximal end of the nail. It lies over the nail matrix where new keratinised cells are formed. The nail folds overlap the posterior and lateral borders. The cuticle works like a gasket to cover and protect the nail matrix.

FUNCTION OF THE SKIN

The skin is a waterproof, almost indestructible covering that has protective and adaptive properties:

• Protection. Skin minimises injury from physical, chemical, thermal and light wave sources.

• Prevents penetration. Skin is a barrier that stops invasion of microorganisms and loss of water and electrolytes from within the body.

• Perception. Skin is a vast sensory surface holding the neurosensory end-organs for touch, pain, temperature and pressure.

• Temperature regulation. Skin allows heat dissipation through sweat glands and heat storage through subcutaneous insulation.

• Identification. People identify one another by unique combinations of facial characteristics, hair, skin colour and even fingerprints. Self-image is often enhanced or deterred by the way society’s standards of beauty measure up to each person’s perceived characteristics.

• Communication. Emotions are expressed in the sign language of the face and in the body posture. Vascular mechanisms such as blushing or blanching also signal emotional states.

• Wound repair. Skin allows cell replacement of surface wounds.

• Absorption and excretion. Skin allows limited excretion of some metabolic wastes, byproducts of cellular decomposition such as minerals, sugars, amino acids, cholesterol, uric acid and urea.

• Production of vitamin D. The skin is the surface on which ultraviolet light converts cholesterol into vitamin D.

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Infants and children

The hair follicles develop in the fetus at 3 months gestation; by midgestation most of the skin is covered with lanugo, the fine downy hair of the newborn infant. In the first few months after birth, this is replaced by fine vellus hair. Terminal hair on the scalp, if present at birth, tends to be soft and to suffer a patchy loss, especially at the temples and occiput. Also present at birth is vernix caseosa: the thick, cheesy substance made up of sebum and shed epithelial cells.

The newborn’s skin is similar in structure to the adult’s, but many of its functions are not fully developed. The newborn’s skin is thin, smooth and elastic and is relatively more permeable than that of the adult, so the infant is at greater risk for fluid loss. Sebum, which holds water in the skin, is present for the first few weeks of life, producing milia and cradle cap in some babies. Then sebaceous glands decrease in size and production and do not resume functioning until puberty. Temperature regulation is ineffective. Eccrine sweat glands do not secrete in response to heat until the first few months of life and then only minimally throughout childhood. The skin cannot protect much against cold because it cannot contract and shiver and because the subcutaneous layer is inefficient. Also, the pigment system is inefficient at birth.

As the child grows, the epidermis thickens, toughens and darkens and the skin becomes better lubricated. Hair growth accelerates. At puberty, secretion from apocrine sweat glands increases in response to heat and emotional stimuli, producing body odour. Sebaceous glands become more active—the skin looks oily and acne develops. Subcutaneous fat deposits increase, especially in females.

Secondary sex characteristics that appear during adolescence are evident in the integument (i.e. skin). In the female the diameter of the areola enlarges and darkens, and breast tissue develops. Coarse pubic hair develops in males and females, then axillary hair, then coarse facial hair in males.

The pregnant female

The change in hormone levels results in increased pigment in the areolae and nipples, vulva and sometimes in the midline of the abdomen (linea nigra) or in the face (chloasma). Hyperoestrogenaemia probably also causes the common vascular spiders and palmar erythema. Connective tissue develops increased fragility, resulting in striae gravidarum, which may develop in the skin of the abdomen, breasts or thighs. Metabolism is increased in pregnancy; as a way to dissipate heat, the peripheral vasculature dilates, and the sweat and sebaceous glands increase secretion. Fat deposits are laid down, particularly in the buttocks and hips, as maternal reserves for the nursing baby.

Late adulthood (65+ years)

The skin is a mirror that reflects ageing changes that proceed in all our organ systems; it just happens to be the one organ we can view directly. The ageing process carries a slow atrophy of skin structures. The ageing skin loses its elasticity; it folds and sags. By the 70s to 80s, it looks parchment thin, lax, dry and wrinkled.

The epidermis’s outer layer, the stratum corneum, thins and flattens. This allows chemicals easier access into the body. Wrinkling occurs because the underlying dermis thins and flattens. A loss of elastin, collagen and subcutaneous fat occurs as well as a reduction in muscle tone. The loss of collagen increases the risk for shearing, tearing injuries.

Sweat glands and sebaceous glands decrease in number and function, leaving dry skin. Decreased response of the sweat glands to thermoregulatory demand also puts the older person at greater risk for heat stroke. The vascularity of the skin diminishes while the vascular fragility increases; a minor trauma may produce dark red discoloured areas, or senile purpura.

Sun exposure and, to a somewhat lesser extent, cigarette smoking further accentuate ageing changes in the skin. Coarse wrinkling, decreased elasticity, atrophy, speckled and uneven colouring, more pigment changes and a yellowed leathery texture occur. Chronic sun damage is even more prominent in pale or light-skinned persons.

An accumulation of factors place the older person at risk for skin disease and breakdown: the thinning of the skin, the decrease in vascularity and nutrients, the loss of protective cushioning of the subcutaneous layer, a lifetime of environmental trauma to skin, the social changes of ageing (e.g. less nutrition, limited financial resources), the increasingly sedentary lifestyle and the chance of immobility. When skin breakdown does occur, subsequent cell replacement is slower, and wound healing is delayed.

In the ageing hair matrix, the number of functioning melanocytes decreases, so the hair looks grey or white and feels thin and fine. A person’s genetic script determines the onset of greying and the number of grey hairs. Hair distribution changes. Males may have a symmetrical W-shaped balding in the frontal areas. Some testosterone is present in both males and females; as it decreases with age, axillary and pubic hair decrease. As the female’s oestrogen also decreases, testosterone is unopposed and the female may have some bristly facial hairs. Nails grow more slowly. Their surface is lustreless and is characterised by longitudinal ridges resulting from local trauma at the nail matrix.

Because the ageing changes in the skin and hair can be viewed directly, they carry a profound psychological impact. For many people, self-esteem is linked to a youthful appearance. This view is compounded by media advertising in western society. Although sagging and wrinkling skin and greying and thinning hair are normal processes of ageing, they prompt a loss of self-esteem for many adults.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Awareness of normal biocultural differences and the ability to recognise the unique clinical manifestations of disease are especially important for people with dark pigmented skin. As described earlier, melanin is responsible for the various colours and tones of skin observed among people from culturally diverse backgrounds. Melanin protects the skin against harmful ultraviolet rays, a genetic advantage accounting for the lower incidence of skin cancer in people with dark pigmented skin. The incidence of melanoma is higher among Caucasians than among people with dark pigmented skin.

Areas of the skin affected by hormones and, in some cases, differing for culturally diverse people are the sexual skin areas, such as the nipples, areola, scrotum and labia majora. In general, these areas are darker than other parts of the skin in both adults and children.

The apocrine and eccrine sweat glands are important for fluid balance and for thermoregulation. When apocrine gland secretions are contaminated by normal skin flora, odour results. The amount of chloride excreted by sweat glands varies widely.

While the characteristics of hair vary widely between people, hair condition is significant in diagnosing and treating certain disease states. For example, hair texture becomes dry, brittle and lustreless with inadequate nutrition.

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Comprehensive assessment of the skin, hair and nails is an important component of health assessment. Skin integrity refers to intact structure and function and relies on adequate perfusion by oxygenated blood and adequate nutrition and hydration. Changes in skin integrity may therefore indicate alterations in perfusion and oxygenation, nutrition and hydration state of the person. Altered skin integrity can also occur as a result of reduced mobility, mechanical or chemical factors, extremes of temperature, bodily excretions or secretions and humidity. Altered skin integrity often results in pain and puts the person at risk of infection.

1. Previous history of skin disease (allergies, hives, psoriasis, eczema)

3. Change in mole (size or colour)

4. Excessive dryness or moisture

OBJECTIVE DATA

Objective assessment of the skin is rarely done in a comprehensive, head-to-toe approach by nurses, although nurses working in skin cancer clinics adopt a systematic, detailed and comprehensive approach. For most nurses, skin assessment is done in an opportunistic way in which the nurse takes the opportunity to examine the person’s skin when performing other health assessments; for example, assisting the person with activities of daily living or assisting the person to move and reposition may prompt the need for a more comprehensive assessment of a particular area of the skin.

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

|---|---|

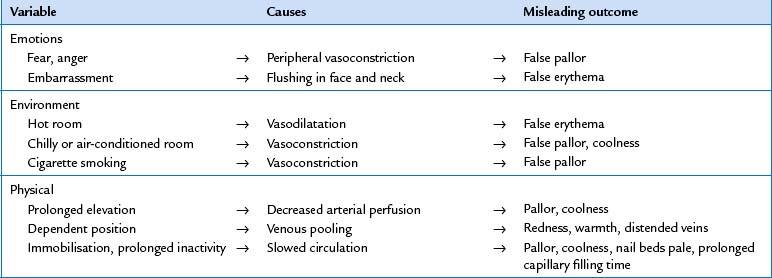

Try to control external variables that may infuence skin colour and confuse your fndings (Table 17.1). Learn to consciously attend to skin characteristics. The danger is one of omission. You grow so accustomed to seeing the skin that you are likely to ignore it as you assess the organ systems underneath. Yet the skin holds information about the body’s circulation, nutritional status and signs of systemic diseases as well as topical data on the integument itself. Know the person’s normal skin colouring. Baseline knowledge is important to assess colour or pigment changes. If this is the first time you are examining the person, ask about their usual skin colour and about any self-monitoring practices. |

TABLE 17.2 Detecting colour changes in light and dark skin

| Note appearance | ||

|---|---|---|

| Aetiology | Light skin | Dark skin |

| Pallor | ||

| Anaemia–decreased haematocrit Shock–decreased perfusion, vasoconstriction | Generalised pallor | Brown skin appears yellow-brown, dull; dark coloured skin appears ashen grey, dull; skin loses its healthy glow–check areas with least pigmentation, such as conjunctivae, mucous membranes |

| Local arterial insuffciency | Marked localised pallor (e.g. lower extremities, especially when elevated) | Ashen grey, dull; cool to palpitation |

| Albinism–total absence of pigment melanin throughout the integument | Whitish pink | Tan, cream, white |

| Vitiligo–patchy depigmentation from destruction of melanocytes | Patchy milky white spots, often symmetrical bilaterally | Same |

| Cyanosis | ||

| Dusky blue | Dark but dull, lifeless; only severe cyanosis is apparent in skin—check conjunctivae, oral mucosa, nail beds | |

| Peripheral–exposure to cold, anxiety | Nail beds dusky | |

| Erythema | ||

| Hyperaemia–increased blood fow through engorged arterioles, such as in infammation, fever, alcohol intake, blushing | Red, bright pink | Purplish tinge, but diffcult to see; palpate for increased warmth with infammation, taut skin and hardening of deep tissues |

| Polycythaemia–increased red blood cells, capillary stasis | Ruddy blue in face, oral mucosa, conjunctiva, hands and feet | Well-concealed by pigment–check for redness in lips |

| Carbon monoxide poisoning | Bright cherry red in face and upper torso | Cherry red colour in nail beds, lips and oral mucosa |

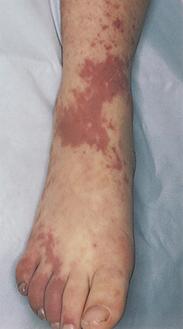

| Venous stasis–decreased blood fow from area, engorged venules | Dusky rubor of dependent extremities; a prelude to necrosis with pressure sore | Easily masked; use palpation for warmth or oedema |

| Jaundice | ||

| Increased serum bilirubin, more than 2 to 3 mg/100 mL from liver infammation or haemolytic disease, such as after severe burns, some infections | Yellow in sclera, hard palate, mucous membranes, then over skin | Check sclera for yellow near limbus; do not mistake normal yellowish fatty deposits in the periphery under the eyelids for jaundice–jaundice best noted in junction of hard and soft palate and also palms |

| Carotenaemia–increased serum carotene from ingestion of large amounts of carotenerich foods | Yellow-orange in forehead, palms and soles, nasolabial folds, but no yellowing in sclera or mucous membranes | Yellow-orange tinge in palms and soles |

| Uraemia–renal failure causes retained urochrome pigments in the blood | Orange-green or grey overlying pallor of anaemia; may also have ecchymoses and purpura | Easily masked; rely on laboratory and clinical fndings |

| Brown–tan | ||

| Addison’s disease–cortisol defciency stimulates increased melanin production | Bronzed appearance, an ‘eternal tan’, most apparent around nipples, perineum, genitalia and pressure points (inner thighs, buttocks, elbow, axillae) | Easily masked; rely on laboratory and clinical fndings |

| Café au lait spots–caused by increased melanin pigment in basal cell layer | Tan to light brown, irregularly shaped, oval patch with well-defned borders | |

| Procedures and normal fndings | Abnormal fndings and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| INSPECT AND PALPATE THE SKIN | |

| Colour | |

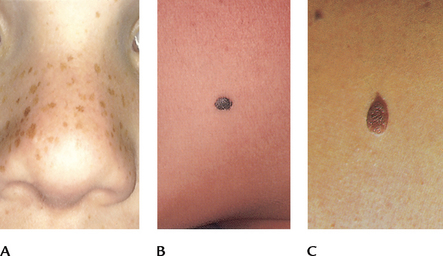

| General pigmentation. Observe the skin tone. Normally it is consistent with genetic background and varies from pinkish tan to ruddy dark tan or from light to dark brown and may have yellow or olive overtones. Dark-skinned people normally have areas of lighter pigmentation on the palms, nail beds and lips (Fig 17.3, A). | An acquired condition is vitiligo, the complete absence of melanin pigment in patchy areas of white or light skin on the face, neck, hands, feet, body folds and around orifces (Fig. 17.3, B). Vitiligo can occur in any person, although dark-skinned people are more severely affected and potentially suffer a greater threat to their body image. |

| General pigmentation is darker in sun-exposed areas. Common (benign) pigmented areas also occur: | |

• Freckles (ephelides)—small, flat macules of brown melanin pigment that occur on sun-exposed skin (Fig 17.4, A). • Mole (naevus)—a proliferation of melanocytes, tan to brown colour, flat or raised. Acquired naevi are characterised by their symmetry, small size (6 mm or less), smooth borders and single uniform pigmentation. The junctional naevus (Fig 17.4, B) is macular only and occurs in children and adolescents. It progresses to the compound naevi in young adults (Fig 17.4, C) that are macular and papular. The intradermal naevus (mainly in older age) has naevus cells in the dermis only. |

Macule: small pigmented spot on the skin that is neither raised nor depressed Papule: a small hard round protuberance on the skin Danger signs: abnormal characteristics of pigmented lesions are summarised in the mnemonic ABCDE: Asymmetry (not regularly round or oval, two halves of lesion do not look the same) Border irregularity (notching, scalloping, ragged edges or poorly defined margins) Colour variation (areas of brown, tan, black, blue, red, white or combination) Diameter greater than 6 mm (i.e. the size of a pencil eraser), although early melanomas may be diagnosed at a smaller size (Oliviero, 2004). |

| Additional symptoms: change in mole’s size, a new pigmented lesion and development of itching, burning or bleeding in a mole. Any of these signs should raise suspicion of malignant melanoma and warrant referral. | |

Widespread colour change. Note any colour change over the entire body skin, such as pallor (whitish tone), erythema (red), cyanosis (blue) and jaundice (yellow). Note whether the colour change is transient and expected or if it is due to pathology. In dark-skinned people the amount of normal pigment may mask colour changes. Lips and nail beds show some colour change, but they vary with the person’s skin colour and may not always be accurate signs. The more reliable sites are those with the least pigmentation, such as under the tongue, the buccal mucosa, the palpebral conjunctiva and the sclera. See Table 17.2 for specifc clues to assessment. |

|

| Pallor. When the red-pink tones from the oxygenated haemoglobin in the blood are lost, the skin takes on the colour of connective tissue (collagen), which is mostly white. Pallor is common in acute high-stress states, such as anxiety or fear, because of the powerful peripheral vasoconstriction from sympathetic nervous system stimulation. The skin also looks pale with vasoconstriction from exposure to cold and cigarette smoking and in the presence of oedema. | Ashen grey colour in a person with dark skin or marked pallor in a person with light coloured skin occurs with anaemia, shock, arterial insuffciency (see Table 17.2). |

| Look for pallor in people with dark skin by the absence of the underlying red tones that normally give brown- or dark-coloured skin its lustre. The brown-skinned person demonstrates pallor with a more yellowish-brown colour, and the person with dark-coloured skin will appear ashen or grey. Generalised pallor can be observed in the mucous membranes, lips and nail beds. The palpebral conjunctiva and nail beds are preferred sites for assessing the pallor of anaemia. When inspecting the conjunctiva, lower the lid suffciently to visualise the conjunctiva near the outer canthus as well as the inner canthus. The colouration is often lighter near the inner canthus. | Anaemias, particularly chronic iron defciency anaemia, may show ‘spoon’ nails, with a concave shape. A lemon yellow tint of the face and slightly yellow sclera accompany pernicious anaemia, also indicated by neurological defcits and a red, painful tongue. Fatigue, exertional dyspnoea, rapid pulse, dizziness and impaired mental function accompany most severe anaemias. The pallor of impending shock is accompanied by other subtle manifestations, such as increasing pulse rate, oliguria, apprehension and restlessness. |

Erythema. Erythema is an intense redness of the skin from excess blood (hyper-aemia) in the dilated superfcial capillaries. This sign is expected with fever, local infammation or with emotional reactions such as blushing in vascular fush areas (cheeks, neck and upper chest). When erythema is associated with fever or localised infammation, it is characterised by increased skin temperature from the increased rate of blood fow through the blood vessels. Because you cannot see infammation in people with dark skin, it is often necessary to palpate the skin for increased warmth, taut or tightly pulled surfaces that may be indicative of oedema and hardening of deep tissues or blood vessels. |

Erythema occurs with polycythaemia, venous stasis, carbon monoxide poisoning and the extravascular presence of red blood cells (petechiae, ecchymoses, haematoma) (see Tables 17.2 and 17.3). |

Cyanosis. This is a bluish mottled colour that signifes that the tissues are not adequately perfused with oxygenated blood. Be aware that cyanosis can be a nonspecifc sign. A person who is anaemic could have hypoxaemia without ever looking cyanosed because not enough haemoglobin is present (either oxygenated or reduced) to colour the skin. On the other hand, a person with polycythaemia (an increase in the number of red blood cells) looks ruddy blue at all times and may not necessarily be hypoxaemic. This person is just unable to fully oxygenate the massive numbers of red blood cells. Cyanosis is difficult to observe in people with dark skin (see Table 17.2). Given that most conditions causing cyanosis also cause decreased oxygenation of the brain, other clinical signs—such as changes in level of consciousness and signs of respiratory distress—will be evident. |

Cyanosis indicates hypoxaemia and occurs with shock, heart failure, chronic bronchitis and congenital heart disease. |

| Jaundice. Jaundice is exhibited by a yellow colour, indicating rising amounts of bilirubin in the blood. Except for physiological jaundice in the newborn (see below), jaundice does not occur normally. Jaundice is first noted in the junction of the hard and soft palate in the mouth and in the sclera. But do not confuse scleral jaundice with the normal yellow subconjunctival fatty deposits that are common in the outer sclera of people with dark skin. The scleral yellow of jaundice extends up to the edge of the iris. | Jaundice occurs with hepatitis, cirrhosis, sickle-cell disease, transfusion reaction and haemolytic disease of the newborn. |

| As levels of serum bilirubin rise, jaundice is evident in the skin over the rest of the body. This is best assessed in direct natural daylight. Common calluses on palms and soles often look yellow—do not interpret these as jaundice. | Light or clay-coloured stools and dark golden urine often accompany jaundice. |

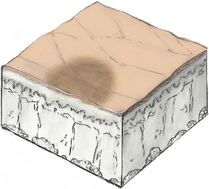

| Pressure injury | |

Assessment is an important aspect of the nurse’s role in prevention of pressure injury. Identifcation of people at risk includes patients/clients with incontinence, who are elderly, have poor oxygenation, nutritional defcit, confusion or who have had recent surgery. Ensure thorough and regular assessment of bony prominences, skinfolds that trap moisture, areas that come in contact with tubing; for example, a patient may require oxygen or tube feeding and the nares or ears are vulnerable to pressure from this equipment. |

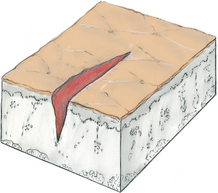

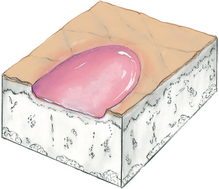

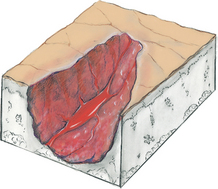

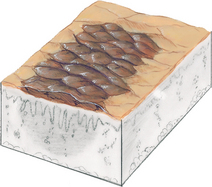

Grade 1: non-blanchable erythema Grade 2: partial thickness skin loss (damage to epidermis and/or dermis—including abrasion, blisters) Grade 3: full thickness skin loss (damage or necrosis of subcutaneous tissues; does not include underlying fascia or underlying structures) Grade 4: full thickness skin loss with extensive destruction and tissue necrosis extending to underlying bone, tendon or joint capsule |

| Temperature | |

| Note the temperature of your own hands. Then use the backs (dorsa) of your hands to palpate the person bilaterally. The skin should be warm, and the temperature should be equal bilaterally; warmth suggests normal circulatory status. Hands and feet may be slightly cooler in a cool environment. | |

| Hypothermia. Generalised coolness may be induced, such as in hypothermia used for surgery or high fever. Localised coolness is expected with an immobilised extremity, as when a limb is in a cast or with an intravenous infusion. | |

| Hyperthermia. Generalised hyperthermia occurs with an increased metabolic rate, such as in fever or after heavy exercise. A localised area feels hyperthermic with trauma, infection or sunburn. | Hyperthyroidism has an increased metabolic rate, causing warm, moist skin. |

| Moisture | |

| Perspiration appears normally on the face, hands, axillae and skinfolds in response to activity, a warm environment or anxiety. Diaphoresis, or profuse perspiration, accompanies an increased metabolic rate, such as occurs in heavy activity or fever. | Diaphoresis occurs with thyrotoxico-sis and with stimulation of the nervous system with anxiety or pain. |

| Look for dehydration in the oral mucous membranes and the elasticity of the skin. Normally the mucous membranes look smooth and moist and the skin is elastic. | With dehydration, mucous membranes look dry and the lips look parched and cracked. With extreme dryness the skin is fissured, resembling cracks in a dry lake bed and does not recoil quickly when lightly pinched. |

| Texture | |

| Normal skin feels smooth and firm, with an even surface. | |

| Thickness | |

| The epidermis is uniformly thin over most of the body, although thickened callus areas are normal on palms and soles. A callus is a circumscribed overgrowth of epidermis and is an adaptation to excessive pressure from the friction of work and weight bearing. | Very thin, shiny skin (atrophic) occurs with arterial insuffciency. |

| Oedema | |

Oedema is fluid accumulating in the intercellular spaces; it is not present normally. To check for oedema, imprint your thumbs firmly against the ankle malleolus or the tibia. Normally the skin surface stays smooth. If your pressure leaves a dent in the skin, ‘pitting’ oedema is present. Its presence is graded on a four-point scale: 1+ Mild pitting, slight indentation, no perceptible swelling of the leg 2+ Moderate pitting, indentation subsides rapidly 3+ Deep pitting, indentation remains for a short time, leg looks swollen 4+ Very deep pitting, indentation lasts a long time, leg is very swollen This scale is somewhat subjective; outcomes vary among examiners (see further content on grading scale in Ch 11). Oedema masks normal skin colour and obscures pathological conditions such as jaundice or cyanosis because the fluid lies between the surface and the pigmented and vascular layers. It makes skin look lighter. |

Oedema is most evident in dependent parts of the body (feet, ankles and sacral areas), where the skin looks puffy and tight. Oedema makes the hair follicles more prominent, so you note a pigskin or orange-peel look (called peau d’orange). Unilateral oedema–consider a local or peripheral cause. Bilateral oedema or oedema that is generalised over the whole body (anasarca)–consider a central problem such as heart failure or kidney failure. |

| Mobility and turgor | |

| Pinch up a large fold of skin on the anterior chest under the clavicle (Fig 17.5). Mobility is the skin’s ease of rising, and turgor is its ability to return to place promptly when released. This refects the elasticity of the skin. | Mobility and turgor is decreased when oedema is present. Poor turgor is evident in severe dehydration or extreme weight loss; the pinched skin recedes slowly or ‘tents’ and stands by itself. Scleroderma, literally ‘hard skin’, is a chronic connective tissue disorder associated with decreased mobility (see Table 17.14). |

| Vascularity or bruising | |

| Cherry (senile) angiomas are small (1 to 5 mm), smooth, slightly raised bright red dots that commonly appear on the trunk in all adults over 30 years old (Fig 17.6). They normally increase in size and number with ageing and are not significant. | |

| Any bruising (ecchymosis) should be consistent with the expected trauma of life. There are normally no venous dilatations or varicosities. | Varicosities: enlarged or swollen veins. Bruises usually occur as a result of trauma, bleeding disorders or liver dysfunction. Multiple bruises at different stages of healing and excessive bruises above knees or elbows should raise concern about physical abuse (see Table 17.6). |

| Document the presence of any tattoos on the person’s chart. | Needle marks or tracks from intravenous injection of non-prescription drugs may be visible on the antecubital fossae, forearms or on any available vein. |

| Lesions | |

If any lesions are present, note the: 2. Elevation: fat, raised or pedunculated 3. Pattern or shape: the grouping or distinctness of each lesion, for example, annular, grouped, confuent, linear. The pattern may be characteristic of a certain disease. 4. Size, in centimetres: use a ruler to measure. Avoid household descriptions such as ‘pea sized’. 5. Location and distribution on body: is it generalised or localised to area of a specific irritant; around jewellery, watchband, around eyes? |

Lesions are traumatic or pathological changes in previously normal structures. When a lesion develops on previously unaltered skin, it is primary. However, when a lesion changes over time or changes because of a factor such as scratching or infection, it is secondary. Study Table 17.3 for the shapes and Tables 17.4 and 17.5 for the characteristics of primary and secondary skin lesions. The terms used (macule, papule, etc.) are helpful to describe any lesion you encounter. |

| Palpate lesions. Wear a glove if you anticipate contact with blood, mucosa, any body fluid or skin lesion. Roll a nodule between the thumb and index finger to assess depth. | Note the pattern and characteristics of common skin lesions (see Table 17.9) and malignant skin lesions (Table 17.10), and lesions associated with AIDS (Table 17.11). |

| Does the lesion blanch with pressure or stretch? Stretching the area of skin between your thumb and index finger decreases (blanches) the normal underlying red tones, thus providing more contrast and brightening the macules. Red macules from dilated blood vessels will blanch momentarily, whereas those from extravasated blood (petechiae) do not. Blanching also helps identify a macular rash in people with dark skin. | |

| INSPECT AND PALPATE THE HAIR AND SCALP | |

| Colour | |

| Hair colour comes from melanin production and may vary from pale blonde to total black. Greying begins as early as the third decade of life because of reduced melanin production in the follicles. Genetic factors affect the age of onset of greying. | |

| Texture | |

| Scalp hair may be fine or thick and may look straight, curly or kinky. It should look shiny, although this characteristic may be lost with the use of some beauty products such as dyes, rinses or other hair treatments. | Note dull, coarse or brittle scalp hair. Grey, scaly, well-defined areas with broken hairs accompany tinea capitis, a ringworm infection found mostly in school-age children (see Table 17.12). |

| Distribution | |

| Fine vellus hair coats the body, whereas coarser terminal hairs grow at the eyebrows, eyelashes and scalp. During puberty, distribution conforms to normal male and female patterns. At first, coarse curly hairs develop in the pubic area, then in the axillae and last in the facial area in boys. In the genital area the female pattern is an inverted triangle; the male pattern is an upright triangle with pubic hair extending up to the umbilicus. The amount of hair varies from person to person. | Absent or abnormally configured pubic hair suggests endocrine abnormalities. Hirsutism–excess body hair. In females, this forms a male pattern of hair distribution on the face and chest and indicates endocrine abnormalities (see Table 17.12). |

| Lesions | |

| Separate the hair into sections and lift it, observing the scalp. With a history of itching, inspect the hair behind the ears and in the occipital area as well. All areas should be clean and free of any lesions or pest inhabitants. Many people normally have seborrhoea (dandruff), which is indicated by loose white fakes on the scalp and hair. | Distinguish dandruff from nits (eggs) of lice, which are oval, adherent to hair shaft and cause intense itching (see Table 17.12). |

| INSPECT AND PALPATE THE NAILS | |

| Shape and contour | |

| The nail surface is normally slightly curved or fat, and the posterior and lateral nail folds are smooth and rounded. Nail edges are smooth, rounded and clean, suggesting adequate self-care. | |

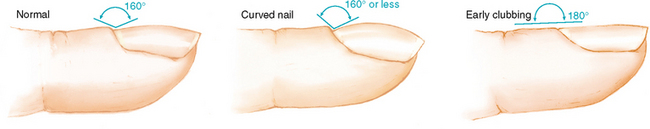

| The profle sign. View the index finger at its profile and note the angle of the nail base; it should be about 160 degrees (Fig 17.7). The nail base is firm to palpation. Curved nails are a variation of normal with a convex profile. They may look like clubbed nails, but notice that the angle between nail base and nail is normal (i.e. 160 degrees or less). | |

| Consistency | |

| The surface is smooth and regular, not brittle or splitting. | Pits, transverse grooves or lines may indicate a nutrient deficiency or may accompany acute illness in which nail growth is disturbed (see Table 17.13). |

| Nail thickness is uniform. | Nails are thickened and ridged with arterial insufficiency. |

| The nail is firmly adherent to the nail bed, and the nail base is firm to palpation. | A spongy nail base accompanies clubbing. |

| Colour | |

| The translucent nail plate is a window to the even, pink nail bed underneath. | Cyanosis or marked pallor. |

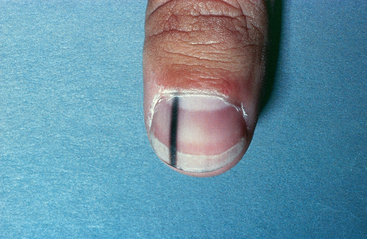

| People with dark skin may have brown-black pigmented areas or linear bands or streaks along the nail edge (Fig 17.8). All people may normally have white hairline linear markings from trauma or picking at the cuticle (Fig 17.9). | Brown linear streaks (especially sudden appearance) are abnormal in light-skinned people and may indicate melanoma. |

| Note any abnormal marking in the nail beds. | Splinter haemorrhages, transverse ridges or Beau’s lines (see Table 17.13). |

Capillary refill. Depress the nail edge to blanch and then release, noting the return of colour. Normally, colour return is instant, or at least within a few seconds in a cold environment. This indicates the status of the peripheral circulation. A sluggish colour return takes longer than 1 or 2 seconds. Inspect the toenails. Separate the toes and note the smooth skin in between. |

Cyanotic nail beds or sluggish colour return: consider cardiovascular or respiratory dysfunction. |

| PROMOTING HEALTH AND SELF-CARE | |

| Teach skin self-examination | |

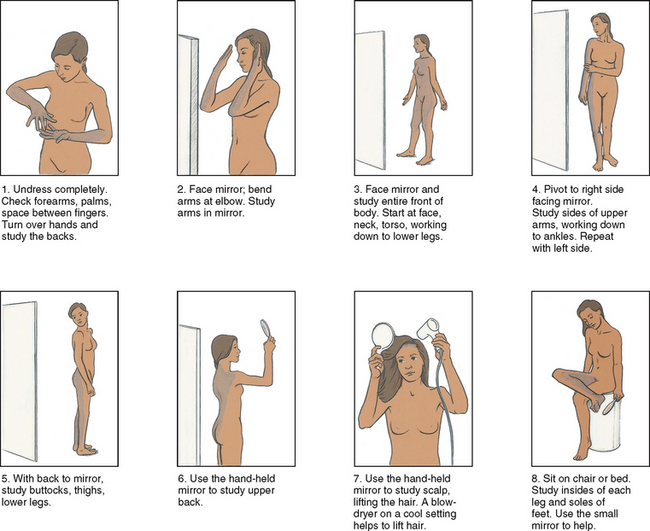

| Teach all adults to examine their skin once a month, using the ABCDE rule (see above) to raise warning signals of any suspicious lesions. Use a well-lighted room that has a full-length mirror. It helps to have a small handheld mirror. Ask a relative to search skin areas difficult to see (e.g. behind ears, back of neck, back). Follow the sequence outlined in Figure 17.10 and advise the person to report any suspicious lesions promptly to their general practitioner or nurse. | |

| DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS | |

| Infants | |

| Skin colour—general pigmentation. Dark-skinned newborns initially have lighter-toned skin than their parents because of a pigment function that is not yet in full production. Their full melanotic colour is evident in the nail beds and scrotal folds. The mongolian spot is a common variation of hyperpigmentation in infants of South-East Asian, Pacific Island and African descent (Fig 17.11). It is a blue-black to purple macular area at the sacrum or buttocks, but sometimes it occurs on the abdomen, thighs, shoulders or arms. It is due to deep dermal melanocytes. It gradually fades during the frst year. By adulthood these spots are lighter but are frequently still visible. | If you are unfamiliar with mongolian spots, be careful not to confuse them with bruises. Recognition of this normal variation is particularly important when dealing with children who might be erroneously identified as victims of child abuse. Bruising is a common soft tissue injury that follows a rapid, traumatic or breech birth. |

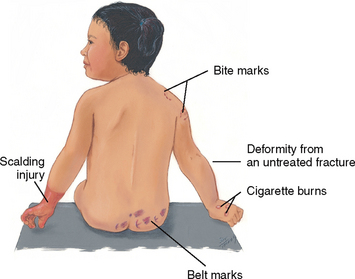

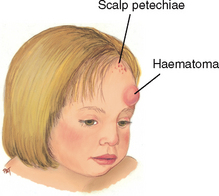

| Multiple bruises in various stages of healing, or pattern injury, suggest child abuse (see Table 17.6). | |

| The café au lait spot is a large round or oval patch of light-brown pigmentation (hence, the name ‘coffee with milk’), which is usually present at birth (Fig 17.12). Most often these patches are normal. | Six or more café au lait macules, each more than 1.5 cm in diameter, are diagnostic of neurofibromatosis, an inherited neurocutaneous disease. |

| Skin colour change. Three erythematous states are common variations in the neonate: | |

3. Finally, erythema toxicum is a common rash that appears in the first 3 to 4 days of life. Sometimes called the ‘flea bite’ rash or newborn rash, it consists of tiny, punctate, red macules and papules on the cheeks, trunk, chest, back and buttocks (Fig 17.13). The cause is unknown; no treatment is needed. |

|

| Two temporary cyanotic conditions may occur: | |

| Persistent generalised cyanosis indicates distress, such as cyanotic congenital heart disease. | |

2. Cutis marmorata is a transient mottling in the trunk and extremities in response to cooler room temperatures (Fig 17.14). It forms a reticulated red or blue pattern over the skin. |

|

Physiological jaundice is a common variation in about half of all newborns. A yellowing of the skin, sclera and mucous membranes develops after the 3rd or 4th day of life because of the increased numbers of red blood cells that haemolyse after birth. The haemoglobin in the red blood cells is metabolised by the liver and spleen; its pigment is converted into bilirubin. Carotenaemia also produces a yellow-orange colour in light-skinned persons but no yellowing in the sclera or mucous membranes. It comes from ingesting large amounts of foods containing carotene, a vitamin A precursor. Carotenerich foods are popular as prepared infant foods, and the absorption of carotene is enhanced by mashing, pureeing and cooking. The colour is best seen on the palms and soles, the forehead, tip of the nose and nasolabial folds, the chin, behind the ears and over the knuckles; it fades to normal colour within 2 to 6 weeks of withdrawing carotenerich foods from the diet. |

Jaundice on the frst day of life may indicate haemolytic disease. Jaundice after 2 weeks of age may indicate biliary tract obstruction. |

| Moisture. The vernix caseosa is the moist, white, cream cheese-like substance that covers part of the skin in all newborns. Perspiration is present after 1 month of age. | |

| Texture. A common variation occurring in the infant is milia (Fig 17.15). Milia are tiny white papules on the cheeks, forehead and across the nose and chin caused by sebum that occludes the opening of the follicles. Tell parents not to squeeze the lesions; milia resolve spontaneously within a few weeks. | |

| Thickness. In the neonate, the epidermis is normally thin, but you will also note well-defned areas of subcutaneous fat. The baby’s skin dimples over joints, but there is no break in the skin. Check for any defect or break in the skin, especially over the length of the spine. | Lack of subcutaneous fat occurs in prematurity and malnutrition. A red sacrococcygeal dimple occurs with a pilonidal cyst or sinus (see Table 20.1). |

| Mobility and turgor. Test mobility and turgor over the abdomen in an infant. | Poor turgor, or ‘tenting’, indicates dehydration or malnutrition. |

| Vascularity or bruising. Some vascular markings are common birthmarks in the newborn. A storkbite (salmon or strawberry patch) is a flat, irregularly shaped red or pink patch found on the forehead, eyelid or upper lip but most commonly at the back of the neck (nuchal area) (Fig 17.16). It is present at birth and usually fades during the frst year. | Port-wine stain, strawberry mark (immature haemangioma), cavernous haemangioma (see Table 17.7). Bruising may suggest abuse (see Table 17.6). |

| Hair. A newborn’s skin is covered with fne downy lanugo (Fig 17.17), especially in a preterm infant. Dark-skinned newborns have more lanugo than lighter-skinned newborns. Scalp hair may be lost in the few weeks after birth, especially at the temples and occiput. It grows back slowly. | Scaly crusted scalp occurs with seborrhoeic dermatitis (cradle cap) (see Table 17.12). |

| Nails. A newborn’s nail beds may be blue (cyanotic) for the first few hours of life; then they turn pink. | |

| Adolescents | |

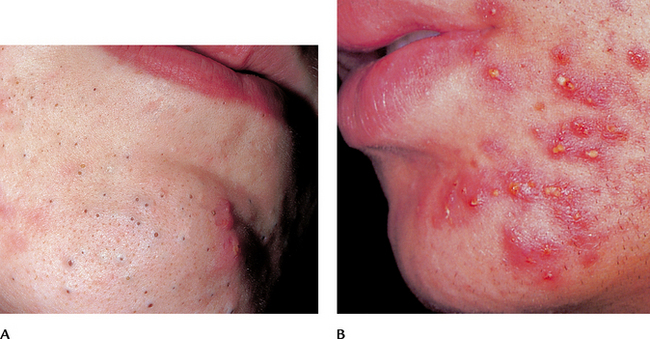

| The increase in sebaceous gland activity creates increased oiliness and acne. Acne is the most common skin problem of adolescence. Almost all teens have some acne, even if it is the milder form of open comedones (blackheads) (Fig 17.18, A) and closed comedones (whiteheads). Severe acne includes papules, pustules and nodules (Fig. 17.18, B). Acne lesions usually appear on the face and sometimes on the chest, back and shoulders. Acne may appear in children as early as 7 to 8 years of age; then the lesions increase in number and severity and peak at 14 to 16 years in girls and at 16 to 19 years in boys. | |

| The pregnant female | |

| Striae are jagged linear ‘stretch marks’ of silver to pink colour that appear during the second trimester on the abdomen, breasts and sometimes thighs. They occur in half of all pregnancies. They fade after delivery but do not disappear. Another skin change on the abdomen is the linea nigra, a brownish black line down the midline (see Fig 28.3). Chloasma is an irregular brown patch of hyperpigmentation on the face. It may occur with pregnancy or in women taking oral contraceptive pills. Chloasma disappears after delivery or stopping the pills. Vascular spiders occur in two-thirds of pregnancies. These lesions have tiny red centres with radiating branches and occur on the face, neck, upper chest and arms. | |

| Late adulthood (65+ years) | |

| Skin colour and pigmentation. Common variations of hyperpigmentation are: | |

| Senile lentigines. Commonly called liver spots, these are small, flat, brown macules (Fig 17.19). These circumscribed areas are clusters of melanocytes that appear after extensive sun exposure. They appear on the forearms and dorsa of the hands. They are not malignant and require no treatment. | |

| Keratoses. These lesions are raised, thickened areas of pigmentation that look crusted, scaly and warty. One type, seborrhoeic keratosis, looks dark, greasy and ‘stuck on’ (Fig 17.20). They develop mostly on the trunk but also on the face and hands and on unexposed as well as on sun-exposed areas. They do not become cancerous. | |

| Another type, actinic (senile or solar) keratosis, is less common (Fig 17.21). These lesions are red-tan scaly plaques that increase over the years to become raised and roughened. They may have a silvery-white scale adherent to the plaque. They occur on sun-exposed surfaces and are directly related to sun exposure. They are premalignant and may develop into squamous cell carcinoma. | |

| Moisture. Dry skin (xerosis) is common in the older person because of a decline in the size, number and output of the sweat glands and sebaceous glands. The skin itches and looks flaky and loose. | |

| Texture. Common variations occurring in the older adult are acrochordons, or ‘skin tags’, which are overgrowths of normal skin that form a stalk and are polyp-like (Fig 17.22). They occur frequently on eyelids, cheeks and neck and axillae and trunk. | |

| Sebaceous hyperplasia consists of raised yellow papules with a central depression. They are more common in men, occurring over the forehead, nose or cheeks. They have a pebbly look (Fig 17.23). | |

| Thickness. With ageing, the skin looks as thin as parchment and the subcutaneous fat diminishes. Thinner skin is evident over the dorsa of the hands, forearms, lower legs, dorsa of feet and over bony prominences. The skin may feel thicker over the abdomen and chest. | |

| Mobility and turgor. The turgor is decreased (less elasticity), and the skin recedes slowly or ‘tents’ and stands by itself (Fig 17.24). | |

| Hair. With ageing, the hair growth decreases, and the amount decreases in the axillae and pubic areas. After menopause, some women may develop bristly hairs on the chin or upper lip resulting from unopposed androgens. In men, coarse terminal hairs develop in the ears, nose and eyebrows, although the beard is unchanged. Male-pattern balding, or alopecia, is a genetic trait. It is usually a gradual receding of the anterior hairline in a symmetrical W shape. In men and women, scalp hair gradually turns grey because of the decrease in melanocyte function. | |

| Nails. With ageing, the nail growth rate decreases, and local injuries in the nail matrix may produce longitudinal ridges. The surface may be brittle or peeling and sometimes yellowed. Toenails are also thickened and may grow misshapen, almost grotesque. The thickening may be a process of ageing or it may be due to chronic peripheral vascular disease. | Fungal infections are common in ageing, with thickened crumbling toenails and erythematous scaling on contiguous skin surfaces. |

TABLE 17.3 Common shapes and confgurations of lesions

|

| Annular, or circular, begins in centre and spreads to periphery (e.g. tinea corporis or ringworm, tinea versicolour, pityriasis rosea) |

|

| Confuent, lesions run together (e.g., urticaria (hives)). |

|

| Discrete, distinct, individual lesions that remain separate (e.g. molluscum). |

|

| Grouped, clusters of lesions (e.g. vesicles of contact dermatitis). |

|

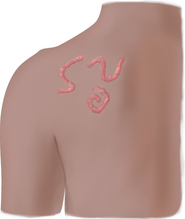

| Gyrate, twisted, coiled spiral, snake-like. |

|

| Target, or iris, resembles iris of eye, concentric rings of colour in the lesions (e.g. erythema multiforme). |

|

| Linear, a scratch, streak, line or stripe. |

|

| Polycyclic, annular lesions grow together (e.g. lichen planus, psoriasis). |

|

| Zosteriform, linear arrangement along a nerve route (e.g. herpes zoster). |

TABLE 17.4 Primary skin lesions*

|

| Macule |

| Solely a colour change, fat and circumscribed, of less than 1 cm. Examples: freckles, fat naevi, hypopigmentation, petechiae, measles, scarlet fever. |

| Patch |

| Macules that are larger than 1 cm. Examples: mongolian spot, vitiligo, café au lait spot, chloasma, measles rash. |

|

| Papule |

| Something you can feel (i.e. solid, elevated, circumscribed, less than 1 cm diameter) caused by superfcial thickening in the epidermis. Examples: elevated naevus (mole), lichen planus, molluscum, wart (verruca). |

| Plaque |

| Papules coalesce to form surface elevation wider than 1 cm. A plateau-like, disc-shaped lesion. Examples: psoriasis, lichen planus. |

|

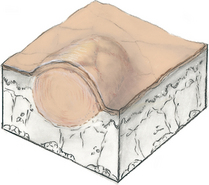

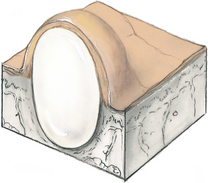

| Nodule |

| Solid, elevated, hard or soft, larger than 1 cm. May extend deeper into dermis than papule. Examples: xanthoma, fbroma, intradermal naevi. |

| Tumour |

| Larger than a few centimetres in diameter, frm or soft, deeper into dermis; may be benign or malignant, although ‘tumour’ implies ‘cancer’ to most people. Examples: lipoma, haemangioma. |

|

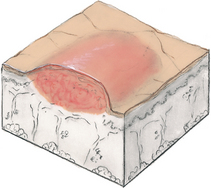

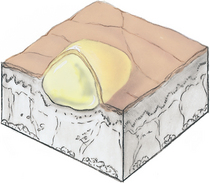

| Wheal |

| Superfcial, raised, transient and erythematous; slightly irregular shape due to oedema (fuid held diffusely in the tissues). Examples: mosquito bite, allergic reaction, dermographism. |

|

| Urticaria (hives) |

| Wheals coalesce to form extensive reaction, intensely pruritic. |

| Reprinted by permission of the publisher from Fireman P: Atlas of allergies, 2nd edn. St Louis, 1995, Mosby. |

|

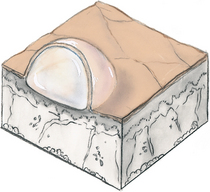

| Vesicle |

| Elevated cavity containing free fuid, up to 1 cm; a ‘blister’. Clear serum fows if wall is ruptured. Examples: herpes simplex, early varicella (chickenpox), herpes zoster (shingles), contact dermatitis. |

| Bulla |

| Larger than 1 cm diameter; usually single chambered (unilocular); superfcial in epidermis; it is thin walled, so it ruptures easily. Examples: friction blister, pemphigus, burns, contact dermatitis. |

|

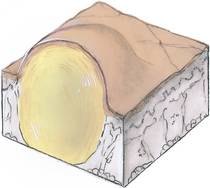

| Cyst |

| Encapsulated fuid-flled cavity in dermis or subcutaneous layer, tensely elevating skin. Examples: sebaceous cyst, wen. |

|

| Pustule |

| Turbid fuid (pus) in the cavity. Circumscribed and elevated. Examples: impetigo, acne. |

* The immediate result of a specific causative factor; primary lesions develop on previously unaltered skin.

TABLE 17.5 Secondary skin lesions*

| DEBRIS ON SKIN SURFACE |

|

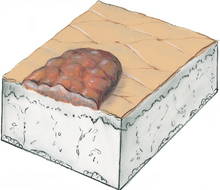

| Crust |

| The thickened, dried-out exudate left when vesicles/pustules burst or dry up. Colour can be red-brown, honey or yellow, depending on the fuid’s ingredients (blood, serum, pus). Examples: impetigo (dry, honey coloured), weeping eczematous dermatitis, scab after abrasion. |

|

| Scale |

| Compact, desiccated fakes of skin, dry or greasy, silvery or white, from shedding of dead excess keratin cells. Examples: after scarlet fever or drug reaction (laminated sheets), psoriasis (silver, mica-like), seborrhoeic dermatitis (yellow, greasy), eczema, ichthyosis (large, adherent, laminated), dry skin. |

| BREAK IN CONTINUITY OF SURFACE |

|

| Fissure |

| Linear crack with abrupt edges, extends into dermis, dry or moist. Examples: cheilosis–at corners of mouth due to excess moisture; athlete’s foot. |

|

| Erosion |

| Scooped out but shallow depression. Superfcial; epidermis lost; moist but no bleeding; heals without scar because erosion does not extend into dermis. |

|

| Ulcer |

| Deeper depression extending into dermis, irregular shape; may bleed; leaves scar when heals. Examples: stasis ulcer, pressure sore, chancre. |

|

| Excoriation |

| Self-inficted abrasion; superfcial; sometimes crusted; scratches from intense itching. Examples: insect bites, scabies, dermatitis, varicella. |

|

| Scar |

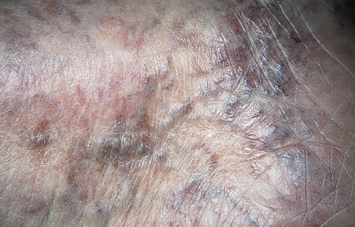

| After a skin lesion is repaired, normal tissue is lost and replaced with connective tissue (collagen). This is a permanent fbrotic change. Examples: healed area of surgery or injury, acne. |

|

| Atrophic scar |

| Resulting skin level depressed with loss of tissue; a thinning of the epidermis. Example: striae. |

|

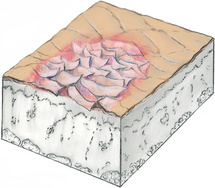

| Lichenifcation |

| Prolonged intense scratching eventually thickens the skin and produces tightly packed sets of papules; looks like surface of moss (or lichen). |

|

| keloid |

| A hypertrophic scar. The resulting skin level is elevated by excess scar tissue, which is invasive beyond the site of original injury. May increase long after healing occurs. Looks smooth, rubbery, ‘clawlike’, and has a higher incidence among dark skinned people. |

Note: Combinations of primary and secondary lesions may coexist in the same person. Such combined designations may be termed papulosquamous, maculopapular, vesiculopustular or papulovesicular.

* Resulting from a change in a primary lesion from the passage of time; an evolutionary change.

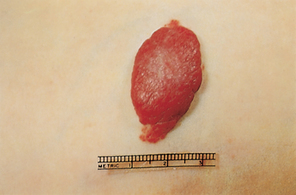

TABLE 17.6 Lesions caused by trauma or abuse

TABLE 17.8 Common skin lesions in children

|

| Nappy dermatitis |

| Red, moist maculopapular patch with poorly defined borders in nappy area, extending along inguinal and gluteal folds. History of infrequent nappy changes or occlusive coverings. Inflammatory disease caused by skin irritation from ammonia, heat, moisture occlusive nappies. |

|

| Intertrigo (candidiasis) |

| Scalding red, moist patches with sharply demarcated borders, some loose scales. Usually in genital area extending along inguinal and gluteal folds. Aggravated by urine, faeces, heat and moisture, the Candida fungus infects the superfcial skin layers. |

|

| Impetigo |

| Moist, thin-roofed vesicles with thin, erythematous base. Rupture to form thick, honey-coloured crusts. Contagious bacterial infection of skin; most common in infants and children. |

|

| Atopic dermatitis (eczema) |

| Erythematous papules and vesicles, with weeping, oozing and crusts. Lesions usually on scalp, forehead, cheeks, forearms and wrists, elbows, backs of knees. Paroxysmal and severe pruritus. Family history of allergies. |

|

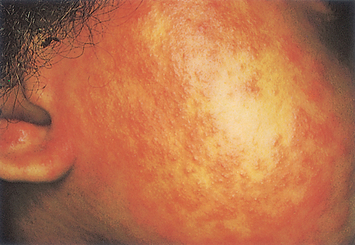

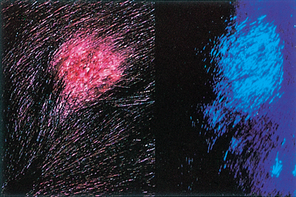

| Measles (rubeola) in dark skin |

| Red-purple maculopapular blotchy rash in dark skin (on left) and in light skin (on right) appears on third or fourth day of illness. Rash appears first behind ears and spreads over face, then over neck, trunk, arms and legs; looks ‘coppery’ and does not blanch. Also characterised by Koplik’s spots in mouth—bluish white, red-based elevations of 1 to 3 mm. |

|

| Measles (rubeola) in light skin |

|

| German measles (rubella) |

| Pink papular rash (similar to measles but paler) frst appears on face, then spreads. Distinguished from measles by presence of neck lymphadenopathy and absence of Koplik’s spots. |

|

| Chickenpox (varicella) |

| Small tight vesicles first appear on trunk, then spread to face, arms and legs (not palms or soles). Shiny vesicles on an erythematous base are commonly described as the ‘dewdrop on a rose petal’. Vesicles erupt in succeeding crops over several days, then become pustules, then crusts. Intensely pruritic. |

TABLE 17.9 Common skin lesions

|

| Primary contact dermatitis |

| Local inflammatory reaction to an irritant in the environment or an allergy. Characteristic location of lesions often gives clue. Often erythema shows first, followed by swelling, wheals (or urticaria) or maculopapular vesicles, scales. Frequently accompanied by intense pruritus. |

|

| Allergic drug reaction |

| Erythematous and symmetric rash, usually generalised. Some drugs produce urticarial rash or vesicles and bullae. History of drug ingestion. |

|

| Tinea corporis (ringworm of the body) |

| Scales—hyperpigmented in whites, depigmented in dark-skinned persons—on chest, abdomen, back of arms forming multiple circular lesions with clear centres. |

|

| Tinea pedis (ringworm of the foot) |

| ‘Athlete’s foot’, a fungal infection, first appears as small vesicles between toes, sides of feet, soles. Then grows scaly and hard. Found in chronically warm moist feet: children after gymnasium activities, athletes, ageing adults who cannot dry their feet well. |

|

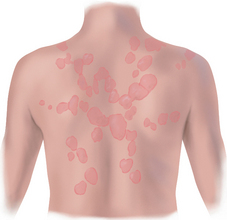

| Psoriasis |

| Scaly erythematous patch, with silvery scales on top. Usually on scalp, outside of elbows and knees, low back and anogenital area. |

|

| Tinea versicolour |

| Fine, scaling, round patches of pink, tan, or white that (hence the name) do not tan in sunlight, caused by a superficial fungal infection. Usual distribution is on neck, trunk and upper arms—a short-sleeved turtleneck sweater area. Most common in otherwise healthy young adults. |

|

| Labial herpes simplex (cold sores) |

| Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection has a prodrome of skin tingling and sensitivity. Lesion then erupts with tight vesicles followed by pustules and then produces acute gingivostomatitis with many shallow, painful ulcers. Common location is upper lip, also in oral mucosa and tongue. |

|

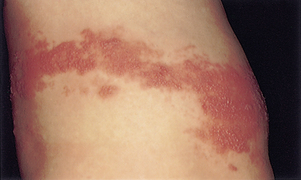

| Herpes zoster (shingles) |

| Small grouped vesicles emerge along route of cutaneous sensory nerve, then pustules, then crusts. Caused by the varicella zoster virus (VZV), a reactivation of the dormant virus of chickenpox. Acute appearance, practically always unilateral, does not cross midline. Commonly on trunk, can be anywhere. If on ophthalmic branch of cranial nerve V, it poses risk to eye. Most common in adults more than 50 years old. Pain is often severe and long lasting in older adults, called postherpetic neuralgia. |

TABLE 17.10 Malignant skin lesions

|

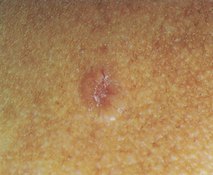

| Basal cell carcinoma |

| Usually starts as a skin-coloured papule (may be deeply pigmented) with a translucent top and overlying telangiectasia. Then develops rounded pearly borders with central red ulcer, or looks like large open pore with central yellowing. Most common form of skin cancer; slow but inexorable growth. |

|

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Erythematous scaly patch with sharp margins, 1 cm or more. Develops central ulcer and surrounding erythema. Usually on hands or head, areas exposed to solar radiation. Less common than basal cell carcinoma but grows rapidly. |

|

| Malignant melanoma |

| Half these lesions arise from preexisting naevi. Usually brown; can be tan, black, pink-red, purple or mixed pigmentation. Often irregular or notched borders. May have scaling, flaking, oozing texture. Common locations are on the trunk and back in men and women, on the legs in women and on the palms, soles of feet and the nails in dark-skinned people. |

TABLE 17.11 Skin lesions associated with AIDS

|

| Epidemic kaposi’s sarcoma: patch stage |

| An aggressive form of Kaposi’s sarcoma is one of the diseases that characterise the epidemic AIDS. Here, multiple patch-stage early lesions are faint pink on the temple and beard area. They could easily be mistaken for bruises or naevi and be ignored. |

|

| Epidemic kaposi’s sarcoma: advanced disease |

| Advanced stage, widely disseminated lesions involving skin, mucous membranes and visceral organs. Here, violet-coloured tumours over the nose and face, and a tiny cherry-red tumour nodule is on the inner canthus of the right eye. |

|

| Epidemic kaposi’s sarcoma: plaque stage |

| Evolving lesions develop into raised papules or thickened plaques. These are oval in shape and vary in colour from red to brown. |

TABLE 17.12 Abnormal conditions of hair

|

| Seborrhoeic dermatitis (cradle cap) |

| Thick, yellow to white, greasy, adherent scales with mild erythema on scalp and forehead; very common in early infancy. Resembles eczema lesions except cradle cap is distinguished by absence of pruritus, ‘greasy’ yellow-pink lesions and negative family history of allergy. |

|

| Tinea capitis (scalp ringworm) |

| Rounded patchy hair loss on scalp, leaving broken-off hairs, pustules and scales on skin. Caused by fungal infection; lesions may fluoresce blue-green under Wood’s light. Usually seen in children and farmers; highly contagious, may be transmitted by another person, by domestic animals or from soil. |

|

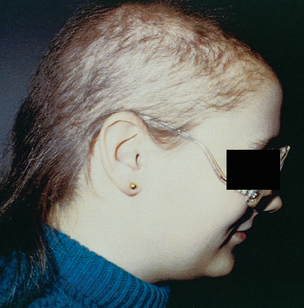

| Toxic alopecia |

| Patchy, asymmetric balding that accompanies severe illness or use of chemotherapy where growing hairs are lost and resting hairs are spared. Regrowth occurs after illness or discontinuation of toxin. |

|

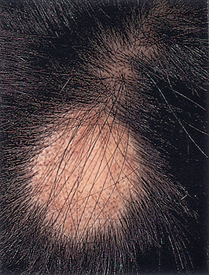

| Alopecia areata |

| Sudden appearance of a sharply circumscribed, round or oval balding patch, usually with smooth, soft, hairless skin underneath. Unknown cause; when limited to a few patches, person usually has complete regrowth. |

|

| Traumatic alopecia: traction alopecia |

| Linear or oval patch of hair loss along hair line, a part or scattered distribution; caused by trauma from hair rollers, tight braiding, tight ponytail, hair clips. |

|

| Trichotillomania |

| Traumatic self-induced hair loss usually the result of compulsive twisting or plucking. Forms irregularly shaped patch, with broken-off, stub-like hairs of varying lengths; person is never completely bald. Occurs as child rubs or twists area absently while falling asleep, reading or watching television. In adults it can be a serious problem and is usually a sign of a personality disorder. |

|

| Pediculosis capitis (head lice) |

| History includes intense itching of the scalp, especially the occiput. The nits (eggs) of lice are easier to see in the occipital area and around the ears, appearing as 2- to 3-mm oval translucent bodies, adherent to the hair shafts. Common among school-age children. Over-the-counter pediculicide shampoos are available; however, nit removal by daily combing of wet hair with a fine-tooth metal comb is especially important. |

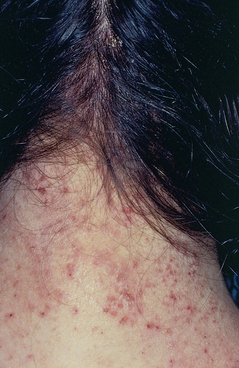

|

| Folliculitis |

| Superficial infection of hair follicles. Multiple pustules, ‘whiteheads’, with hair visible at centre and erythematous base. Usually on arms, legs, face and buttocks. |

|

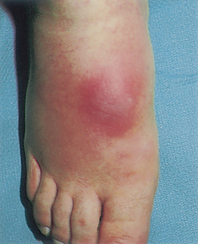

| Furuncle and abscess |

| Red, swollen, hard, tender, pus-filled lesion caused by acute localised bacterial (usually staphylococcal) infection; usually on back of neck, buttocks, occasionally on wrists or ankles. Furuncles are due to infected hair follicles, whereas abscesses are due to traumatic introduction of bacteria into the skin. Abscesses are usually larger and deeper than furuncles. |

TABLE 17.13 Abnormal conditions of the nails

TABLE 17.14 Chronic connective tissue disorder associated with decreased mobility

Promoting a healthy lifestyle Artificial tanning and skin cancer risk

The dangers of tanning salons

Despite public health warnings and increasing evidence of the dangers of artificial UV radiation, indoor tanning salons continue to be popular. We know that prolonged sun exposure can lead to skin cancer, yet why is it that we do not realise the potential dangers of tanning salons? As healthcare providers, the skin examination is an opportunity to educate the public about the dangers of excessive UV exposure. As you examine an individual’s skin, take the time to ask about the use of tanning salons. Ask about solar exposure and outdoor sun-protective precautions as well.

There are many documented adverse effects of sunbeds, including acute sunburn, suppression of cutaneous DNA repair and immune functioning, ocular disorders and increased risk of skin cancer, specifically squamous/basal cell carcinoma and melanoma. Exposure to sunbeds and sunlamps is known to be a human carcinogen (VicHealth and Cancer Council Victoria, 2009). In addition, in 2010 the World Health Organization publicly recognised the dangers of sunbed use and declared that, worldwide, no person under the age of 18 years should use a sunbed. Yet, despite these warnings, the tanning industry appears to have convinced the public that indoor tanning is healthy, emphasising that tanning produces a psychological sense of wellbeing and can even induce vitamin D production. Further, they claim that getting a tan before you go out into the sun can actually prevent sunburn, a known risk factor for skin cancer. ‘Pretanning’ before a holiday or outdoor sun exposure is a particularly dangerous practice because not only does it lead to extra UV exposure, but it also appears to lead to decreased use of subsequent outdoor sun-protective precautions. At best, artificial ‘pretans’ only offer the protection equal to a sunscreen with an SPF 2 to 3, well under the minimal protective recommendation—SPF 15.

Regulations are now in place for manufacturers of indoor tanning equipment limiting the amount of UV radiation that can be emitted. These regulations do not control the proportion of UVB emitted, however. Most tanning salons promote their devices emitting UVA light, which is thought to be ‘safer’ than UVB light; however, UVB light usage is increasing as it intensifies tanning results. Further, the amount of UVA light received in a tanning salon may be two to three times more than the UVA light we receive from the sun and is a known risk factor for melanoma. Women who use tanning beds more than once a month are 55% more likely to have malignant melanoma. In addition, people who use tanning salons are 2.5 times more likely to have squamous cell carcinoma and 1.5 times more likely to have basal cell carcinoma.

Although one of the sources of vitamin D is exposure to UV light, an adequate level of vitamin D is typically attained through incidental exposure to the sun and normal dietary intake of vitamin D. Sources of vitamin D that do not carry an increased risk of skin cancer include vitamin D supplements or food sources supplemented with vitamin D.

Many individuals feel that tanning gives you a ‘healthy glow’; on the contrary, the long-term use of tanning can lead to something more frightening and deadly.

DOCUMENTATION AND CRITICAL THINKING

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY 1

Ethan E is a 3-year-old male presenting with his mother, who seeks healthcare because of Ethan’s fever, fatigue and rash of 3 days duration.

Subjective

2 weeks ago—Ethan was playing with a child who was subsequently diagnosed as having chickenpox. Three days ago mother reports Ethan had a fever 37.7° to 38.3°C and fatigue, irritability. That evening noted ‘tiny blisters’ on chest and back.

Yesterday blisters on chest changed to white with scab on top. New eruption of blisters on shoulders, thighs, face. Intense itching and scratching.

Objective

Skin: Generalised vesiculopustular rash covering face, trunk, upper arms and thighs. Small vesicles on face, pustules and red-honey-coloured crusts on trunk. Otherwise skin is warm and dry, turgor elastic.

Ears: Tympanic membranes pearl-grey with landmarks intact. No discharge.

Mouth and throat: Mucosa dark pink, no lesions. Tonsils 1+, no exudate. No lymphadenopathy.

Heart: S1, S2 normal, not accentuated or diminished, no murmurs or extra sounds.

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY 2

Myra G is a 79-year-old widowed retired academic, in good health up until recent hospitalisation after a fall. A fractured right hip was diagnosed and followed by hip replacement surgery.

Australasian College of Dermatologists, Available at http://www.dermcoll.asn.au/public/default.asp.

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. National skin cancer awareness campaign. Available at http://www.skincancer.gov.au/.

Cancer Council Australia, Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society, Osteoporosis Australia and the Australasian College of Dermatologists, 2008: How much sun is enough? Getting the balance right—vitamin D and sun protection (brochure).

Cancer Council Australia. Solariums. Available at http://www.cancercouncilnt.com.au/postition Statements/Solariums.pdf.

Cancer Council ACT. 2010: Solariums and fake tans. Available at http://www.actcancer.org/downloads/File/Solarium and Fake Tans Jan10.pdf.

Biagini M, et al. Genetic and environmental risk factors for childhood eczema development and allergic sensitization in the CCAAPS cohort. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2010;130(2):430–437.

Cashen K, Kamat D. Recurrent fever and rash. Clinical Pediatrics. 2009;48(6):679–682.

de Haas E, Nijsten T, de Vries E. Population education in preventing skin cancer: from childhood to adulthood. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2010;9(2):112–116.

Doherty D. Skin care considerations in chronic oedema. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2009;Supplement:S4–S12.

Driver C. Tick-borne diseases. Practice Nurse. 2010;39(3):24–27.

Ek E, Giorlando F, Su S, et al. Clinical diagnosis of skin tumours: how good are we? ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2005;75(6):415–420.

Emond RT, Welsby P, Rowland H. Colour atlas of infectious diseases, 4th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2003.

Farage MA, Miller KW, Berardesca E, et al. Neoplastic skin lesions in the elderly patient. Cutaneous and Ocular Toxicology. 2008;27(3):213–229.

Goldberg A, Tobin J, Daigneau J, et al. Bruising frequency and patterns in children with physical disabilities. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):604–609.

Grant-Els J, ed. Color atlas of dermatopathology. New York: Informa Healthcare, 2007.

Gregonou S, Argyriou G, Larios G, et al. Nail disorders and systemic disease: What the nails tell us. Journal of Family Practice. 2008;57(8):509–514.

Habif TP, et al. Skin disease: diagnosis and treatment, 2nd edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2005.

Hamidi R, Peng D, Cockburn M. Efficacy of skin self-examination for the early detection of melanoma. International Journal of Dermatology. 2010;49(2):126–134.

Hess C. Practice points. Performing a skin assessment. Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 2008;21(8):392.

Levine JA, et al. The indoor UV tanning industry: A review of skin cancer risk, health benefit claims, and regulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(6):1038–1044.

Mirza S. Benign skin tumours. InnovAiT. 2009;2(6):342–350.

O’Dea D. The costs of skin cancer to New Zealand, Cancer Update in Practice 2. Available at www.cancernz.org.nz, 2000.

Oliviero MC. Skin lesions in the elderly: precancer and cancer. Care Manage J. 2004;5(2):107–111.

Puchalski A, Winograd S. Petechial rashes. Pediatric Emergency Medicine Reports. 2010;15(1):1–12.

Rowe J, McCall E, Kent B. Clinical effectiveness of barrier preparations in the prevention and treatment of nappy dermatitis in infants and preschool children of nappy age. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2008;6(1):3–23.

Samanek AJ, Croager EJ, Gies P. Estimates of beneficial and harmful sun exposure times during the year for major Australian population centres. Med J Aust. 2006;184(7):338–341.

Shah S, Kannikeswaran N, Kamat D. A rash. Clinical Pediatrics. 2007;46(7):650–654.

Shih ST-F, Carter R, Sinclair C, et al. Economic evaluation of skin cancer prevention in Australia. Preventive Medicine. 2009;49(5):449–453.

VicHealth and Cancer Council Victoria. Solariums and tanning. Available at http://www.sunsmart.com.au/sun_protection/tanning_and_solariums.

Watkins J. Dermatology and the community nurse: actinic (solar) keratosis. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2010;15(1):6–11.

Wheeler T. Diagnosing common skin conditions in a care home. Nursing & Residential Care. 2009;11(12):602–603. 600

Wheeler T. The role of skin assessment in older people. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2009;14(9):380–384.

World Health Organization. Sunbeds, tanning and UV exposure. Available at http://www.who.int/mendiacentre/factsheets/fs287/en/.