Chapter Eighteen Urinary system

INTRODUCTION

Structures relevant to assessment of urinary tract function include the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. The upper urinary tract consists of the kidneys and ureters. The lower urinary tract consists of the bladder and urethra. The male prostate gland, while not related to the urinary tract in terms of urine production, drainage of urine, storage and voiding, is an important structure to consider in this chapter as any enlargement of the prostate can lead to obstructed urine flow through the urethra. The structure and function of the prostate gland is described in Chapter 26. Likewise the pelvic floor muscles play an important role in the maintenance of continence (see Ch 25).

STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

The urinary system has several important functions including the regulation of blood volume and composition; assisting in the regulation of blood pressure; production of hormones (calcitriol and erythropoietin); regulation of blood glucose levels; excretion of wastes in the urine; passing urine from the kidney to the bladder via the ureters; storage of urine in the bladder; emptying the stored urine from the bladder via the urethra (Jenkins, Kemnitz and Tortora, 2010).

KIDNEYS

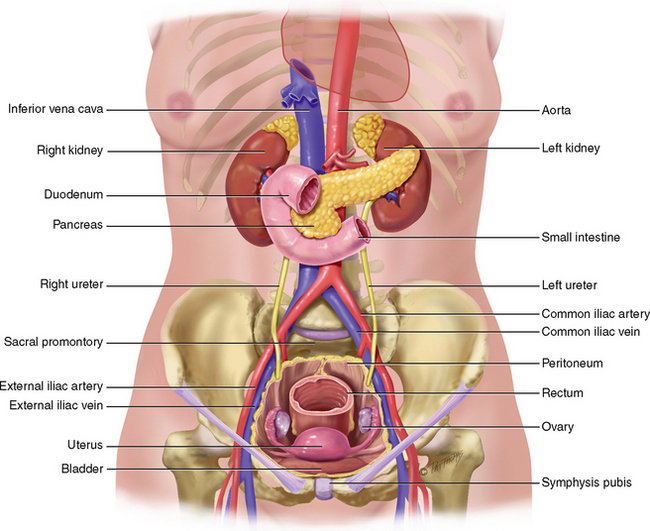

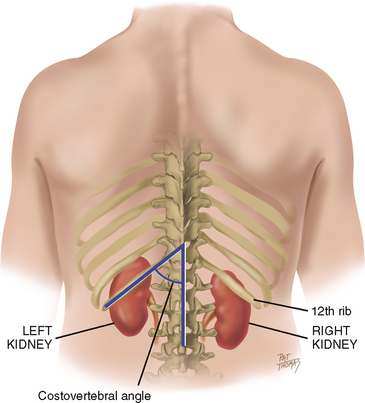

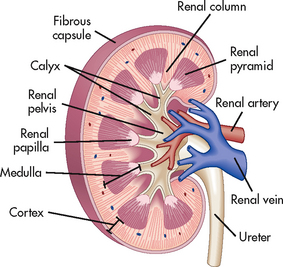

The bean-shaped kidneys are retroperitoneal, or posterior to the abdominal contents (Fig 18.1). They are well protected by the posterior ribs and musculature. The twelfth rib forms an angle with the vertebral column, the costovertebral angle (Fig 18.2). The left kidney lies here at the eleventh and twelfth ribs. An average-sized adult kidney is approximately 10–12 cm long and 5–7 cm wide and weighs approximately 115–150 gm. Each kidney is covered by three layers of tissue: the renal capsule, adipose capsule and renal fascia which all help to maintain the position of the kidney and protect it from trauma. Near the centre of each kidney is a narrowing (the renal hilum) through which the ureter, renal artery and renal vein, lymphatic vessels and nerves enter and exit. A longitudinal section through the kidney (Fig 18.3) reveals two distinct regions; the outer layer (renal cortex) and the inner layer (the medulla). The medulla consists of a number of pyramid shaped structures (the renal pyramids) which narrow forming the renal papillae. The renal cortex contains the functional unit of the kidney, the nephron. There are more than 1 million nephrons in each healthy kidney. Each nephron is a complex system comprising a glomerulus, Bowman’s capsule and tubular system (proximal convoluted tubule, the loop of Henle and the distal convoluted tubule). Several nephrons merge together into a collecting duct which empties via the papillae to the minor calyx, the renal pelvis, eventually draining into the ureters. The two kidneys receive 25% of the resting cardiac output into the renal arteries. In adults renal blood flow is approximately 1200 mL per minute. The amount of filtrate formed in the renal corpuscle (a Bowman’s capsule and a glomerulus) of both kidneys each minute is known as the glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

URETERS

The two ureters extend in a continuous tube from the renal pelvis (pelvoureteric junction) to the trigone of the bladder (vesicoureteric junction) and carry urine from the kidney. Peristaltic contractions of the muscle walls of the ureters help move urine down each ureter into the bladder. Each ureter is 24–30 cm long and has a diameter of approximately 3–4 mm. Three layers of muscle form the ureters (the mucosa, the muscularis and the adventitia). The deepest layer (the mucosa) is composed of transitional epithelium which is able to stretch to accommodate varying volume of fluid. The distal end of the ureter enters the bladder on an angle at the vesicoureteric junction. The muscle of bladder and ureter in combination with the angle of entry of the ureter into the bladder acts as a valve-like mechanism to prevent reflux of urine back up into the ureter from the bladder during micturition.

BLADDER

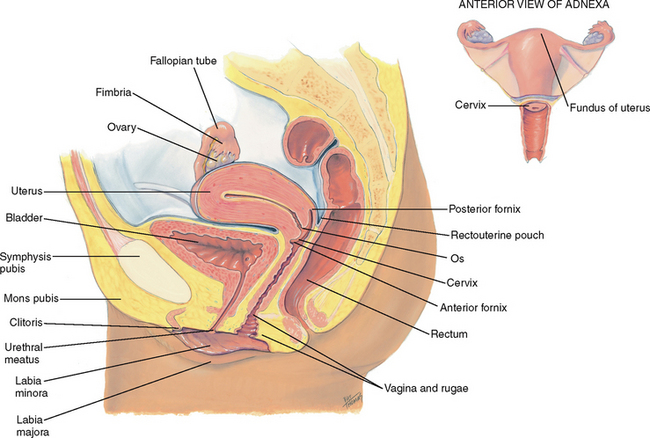

The urinary bladder is a hollow organ designed to store and expel urine. It lies in the pelvic cavity posterior to the symphysis pubis. In men the bladder lies directly anterior to the rectum and in women it is anterior to the vagina and inferior to the uterus. The size and shape of the bladder changes to comply with the amount of urine it contains. At the base of the bladder there is a triangular area called the trigone. The two upper corners of the trigone contain the two ureteral openings and the lower corner is where the urethral orifice is located. The bladder is constructed of four layers of tissue. The inner surface of the bladder is lined with transitional cell epithelium that prevents reabsorption of urine. The muscle of the bladder consists of three layers of smooth muscle (the detrusor muscle). The outermost layer (the adventitia) is composed of fibroelastic connective tissue. The serosa, a layer of the visceral peritoneum, lies over the superior surface of the bladder.

URETHRA

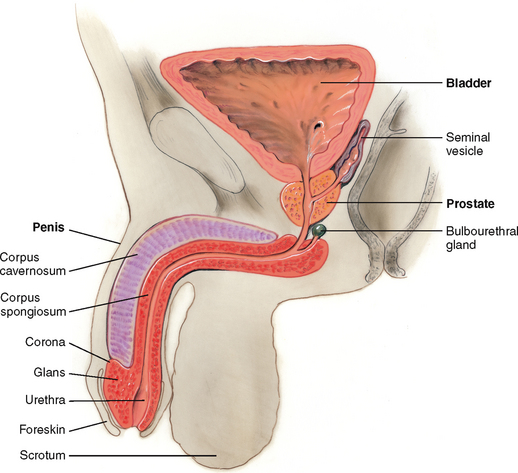

The urethra is a small tube from the base of the bladder (bladder neck) to the outside of the body. In women the urethra is approximately 3.5–5.5 cm in length and leaves the bladder neck at an angle. The entire length of the female urethra acts as a sphincter mechanism and contributes to continence during bladder filling. The urethral orifice lies between the clitoris and the vaginal opening (Fig 18.4). The relative shortness of the female urethra and its position close to the vagina and anus predisposes women to urinary tract infection (UTI) from ascending movement of bacteria up the urethra into the bladder. In males the urethra is approximately 23 cm long and is divided into two portions; proximal and distal (Fig 18.5). The proximal urethra originates at the bladder neck and travels through the prostate gland (prostatic urethra). The next portion of the proximal urethra is the membranous urethra (approx 2–2.5 cm in length) which passes through the deep muscle of the perineum. These two sections form the sphincter mechanism in males. The distal urethra (the spongy urethra) consists of four parts: the bulbous urethra, pendulous urethra, fossa navicularis and the meatus. The male urethra transverses the corpus spongiosum, and its meatus forms a slit at the glans tip. The urethra consists of a mucosa and muscularis with circular smooth muscle fibres continuous with the wall of the bladder.

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Infants and children

At birth the kidneys occupy a large portion of the abdominal cavity. Urine formation occurs at the third month of fetal development and contributes to the volume of amniotic fluid. At birth the bladder is located in the abdomen and as the child grows it becomes a pelvic structure. In infants and children micturition is an involuntary act occurring about 20 times per day. As the child develops the frequency of voiding decreases and mean voiding volume increases. At about 2–3 years of age the child becomes aware of bladder filling and begins to be able to inhibit voiding by contracting the pelvic floor muscles. As the central nervous system develops the child learns to inhibit the detrusor muscle activity, which enables them to achieve continence.

Adults and late adulthood (65+ years)

Kidney and bladder function change as people age. The kidneys decrease in size and weight as does the glomerular filtration rate. By 70 years of age approximately 30–50% of glomeruli have stopped functioning. Under normal circumstances these changes do not cause any problems with maintaining homeostasis. However, the decrease in function puts the older person more at risk for health problems with rapid changes to blood volume or other insults. Physiological changes related to ageing occur in the bladder and urethra. For example, changes to the female bladder, urethra, vagina and pelvic floor due to decreasing oestrogen following menopause can cause these structures to become less vascular, thinner and less elastic. The muscles that surround the urethra and support the bladder can lose strength, causing changes to the anatomical positioning of these structures. In men the prostate gland enlarges and can obstruct the flow of urine through the urethra (see ‘Promoting a healthy lifestyle’ below).

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Assessment of urinary tract function is a frequent assessment area for nurses in a variety of healthcare settings. The extent of the questioning and examination will depend on the person’s main health concern. Assessment of fluid and electrolyte balance is a common assessment for hospitalised patients. Many people with urinary problems, in particular urinary incontinence, will be reluctant to discuss their problem so you need to pose these questions with tact and empathy. You need to keep in mind that bladder problems often coincide with bowel problems, especially constipation and, in men, erectile dysfunction, so you may need to assess these areas as well. There are common terms that the general public use to describe urine and the process of voiding, for example ‘wee’ and ‘having a leak’; while the correct terms are used in the assessment guidelines below, you may need to adjust your language when you are collecting the subjective information.

There are many tools available to assist in the collection of subjective data, specifically in relation to the presence and severity of urinary symptoms, including incontinence, and the impact of these symptoms on the quality of life. These validated tools are used in clinical practice and research. The following are some—not all—of the most commonly used tools:

• Assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms in men: I-PPS—American Urological Association Symptom Index

• Assessment of quality of life in benign prostate disease: BPH Bother Index

• Assessment of quality of life in prostate cancer: UCLA—Prostate Cancer Index or EPIC—Expanded Prostate Cancer Index

• Assessment of sexual function in men: IEEF—International Index of Erectile Function

• Symptoms of incontinence: Bristol Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

Assessment components

3. Fluid intake (type and amount)

4. History of change or disturbance to urinary tract function

6. Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)

7. Other symptoms (including fever, weight gain/loss, fatigue)

| Assessment guidelines | Clinical signifcance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

There is a usual pattern to voiding over a 24-hour period although there is variation between individuals. It is considered normal for an adult to void 3–5 hourly during the daytime and not need to void overnight. The adult bladder capacity is approximately 500 mL and there should be no residual urine volume after voiding (Getliffe and Dolman, 2007) |

|

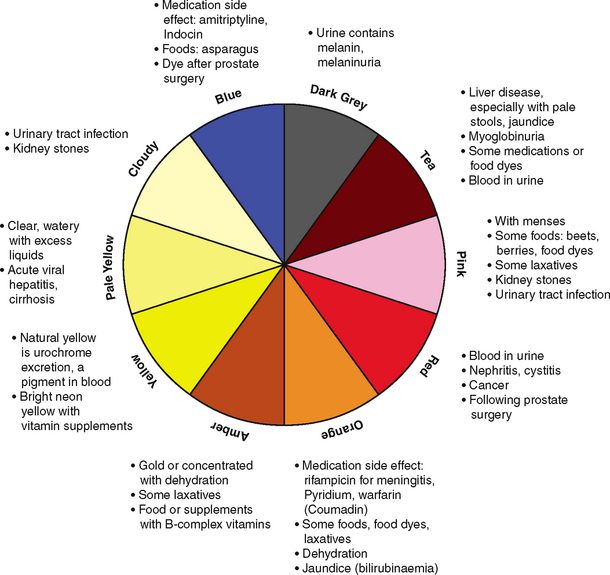

Urine should normally be clear, light yellow coloured and have a non-offensive odour. Cloudy—urinary tract infection. Haematuria—a danger sign that warrants further workup. Some colour changes are temporary or harmless. However, when there is blood in urine, or a colour change lasting >1 day, the person should seek healthcare. For a complete description, see Table 18.1. |

|

3 Fluid intake (type and amount) • Assessment of ‘fluid balance’ is often conducted for hospitalised patients using a fluid balance chart to record intake and output over a 24-hour period.

• It is often difficult for people to accurately estimate the amount of fluid they consume in a day. In community and clinic settings accurate assessment of fluid intake and output is also important for those people with renal and urinary tract health problems (and others, for example with heart failure). The person (or their carer) should be asked to keep a written record usually over three 24-hour periods. See further information in the voiding diary section below.

|

It is important to ascertain the types of fluids consumed over the day and night because some types of fluids are known to irritate the bladder in certain individuals; for example, caffeine-containing fluids such as coffee and cola drinks. Alcohol is a diuretic and can cause exacerbation of urinary symptoms, especially frequency and urgency. |

| Changes in urinary tract function can be a symptom of underlying significant health problems such as malignancy and require further assessment. You need to fully investigate and document the details of the typical symptoms that the person is experiencing. | |

• Do you have any pain? Where is the pain? Can you describe the nature of this pain (e.g. stabbing, dull ache, burning)? How long does it last? On a scale of 0–10 how bad is this pain at the moment (0—no pain to 10—worst pain ever)? If the person doesn’t have pain at the time, on a scale of 0–10 how bad has the pain been recently? Does anything make this pain worse (e.g. voiding or having bowels opened, sexual intercourse)?

|

There are several sites for pain associated with upper and/or lower urinary tract dysfunction. Keep in mind that pain may be referred from another organ or site and may be associated with general symptoms such as fever or nausea. Flank pain (costovertebral angle) is usually associated with a disorder of the renal pelvis or kidney, especially when it is unilateral. A continuous dull ache is associated with chronic obstruction or infection. An acute pain in the flank region may be the result of acute obstruction of the renal pelvis or proximal (upper) ureter and is commonly termed ‘renal colic’. Pain may also radiate to upper lateral aspect of the abdomen. It is often described as moderate to severe in intensity and will cause the person to seek help. The pain tends to occur in waves during which the pain intensifes for periods of time as the pressure in the ureter and renal pelvis increases in response to the peristaltic waves. If the obstruction is in the lower ureter the pain may also radiate to the inguinal area and/or groin and upper thigh. The person with this type of pain should also be questioned about haematuria, fever and other urinary tract symptoms that might indicate infection (e.g. cloudy, foul-smelling urine, dysuria, frequency) (Gray and Moore, 2009). See also Table 19.2. Clinical alert: people with pain indicating renal colic and signs and symptoms of infection need urgent medical referral for further assessment and intervention to prevent septicaemia. |

| • Do you ever experience pain associated with passing urine? | Lower urinary tract and pelvic pain— most commonly caused by urinary tract infection (including prostatitis in the male). Dysuria (painful urination) is a common symptom related to urinary tract dysfunction. Typically the person complains of burning on urination which is associated with lower urinary tract infection and, less commonly, prostatitis in men. |

| Increased daytime frequency—voiding more than 8 times per day. It is important to take into account the volume of urine per void and fluid intake when assessing urinary frequency. The increased urinary frequency could be the result of an unusually high fluid intake or an underlying problem with renal function. | |

| Urgency—Do you feel that you are able to delay going to the toilet? | Urgency—inability to defer voiding after feeling the desire to void. Can lead to urge urinary incontinence if the person is unable to quickly respond to the desire to void. Urgency can be a debilitating urinary symptom that significantly affects activities of daily living and decreases a person’s quality of life (Elstad et al, 2010). Urgency often accompanies urinary frequency. |

| Nocturia—Do you need to get up at night to pass urine? How often? How long has this been occurring? Has it increased over this time? | Getting up to void more than two times per night is considered to be excessive nocturia (Getliffe and Dolman, 2007). It is commonly associated with benign prostatic enlargement in men over the age of 50 years and can be severe. Some men have to void more than six times per night; this results in sleep disturbance, relationship tensions and a general decrease in health and wellbeing (Booth et al, 2010). Other causes are cardiovascular disorders, urinary tract infection, hyperglycaemia and diuretic medication. |

Urinary incontinence—Do you ever lose or leak urine when you don’t want to? Keep in mind that people will frequently underestimate their urinary symptoms, especially if they have urinary incontinence. Often if asked directly about urinary incontinence they will answer ‘no’. However, if you ask about whether they use pads so their clothes don’t get wet they may answer ‘yes’. This happens because people are embarrassed; and some may have had the problem for a long time and now consider it ‘normal’. When does the leakage occur (changing position, coughing, sneezing, laughing or no provocation)? How much urine is lost (estimate in terms of dampness to clothing)? How often does this happen? |

Urinary incontinence is the inability to control the passage of urine which is sufficient to be a social or hygienic problem (Abrams et al, 2002). It is important to note that this is an involuntary loss of urine. A comprehensive assessment of urinary incontinence takes time and expertise to determine the exact type of urinary incontinence. The person may need referral to a continence nurse advisor for further assessment and advice. The International Continence Society classifies the varying types of urinary incontinence according to the typical symptoms (Abrams et al, 2009): |

| Stress urinary incontinence—urine leakage which occurs when there is an increase in intraabdominal pressure. This type of incontinence is often caused by weakness of the pelvic floor muscles. Usually small amounts of urine are leaked. | |

| Do you ever lose urine because you are unable to get to the toilet in time? | Overactive bladder is the term used to describe a syndrome of bothersome urgency, frequency, nocturia and sometimes urine leakage. |

| Urge incontinence occurs in the presence of a signifcant sensation of urgency. The person may not be able to inhibit the urge and this can result in the entire bladder contents being leaked. Urge incontinence can be caused by a number of factors including neurological conditions such as stroke and multiple sclerosis, and local causes such as urinary tract infection, faecal impaction or prostatic enlargement (Getliffe and Dolman, 2007). | |

| Mixed urinary incontinence—a combination of stress and urge symptoms. | |

| Do you ever lose urine at night when you are asleep? | Nocturnal enuresis—any involuntary loss of urine occurring during sleep. Most commonly occurs in children but can also occur in adults. Loss of urine at night can also occur in people who have acute or chronic urinary retention (see below). |

| Does urine leak regardless of what you are doing? Do you feel that you completely empty your bladder after you have been to the toilet? | Continuous urinary leakage—can be a sign of anatomical abnormality; for example, a fistula formation from bladder to vagina, or continuous overfow of urine where there is an acute or chronic obstruction causing retention with some overfow of urine. The most common cause of retention of urine is enlargement of the prostate gland in men. |

| Do you have trouble getting to the toilet—e.g. walking, transferring from chair to standing, standing to toilet? Are you able to undress/redress for toileting unassisted? See also below on environmental factors. | Functional incontinence—urinary leak -age that is associated with impairment of the person’s mobility, dexterity or cognitive function (Newman and Wein, 2009). Certain medications such as sedatives can also contribute to functional incontinence. This type of incontinence is a significant problem for frail older people and those people with a disability. The person’s or their carer’s answers to these questions may lead to the need for a more in-depth assessment of the home environment and referral to an occupational therapist. |

| Slow urinary stream—perception that the urinary stream has slowed. If the person has a severe slowing of the urinary stream they may describe it as a dribble or trickle. Sometimes described as a weak stream. | |

| Intermittent/interrupted stream— starting and stopping voiding. | |

| Straining—Do you ever have to strain (bear down) to start or continue urinating? Do you ever have to strain to completely empty your bladder? | Straining—using muscular effort to initiate, maintain or improve the urinary stream. This is abnormal and may indicate an underlying dysfunction of the detrusor or bladder outlet obstruction. |

| post-micturition dribble—a symptom most commonly affecting men where there is a small loss if urine after urination is completed, happening even when the man is redressing. | |

| Feeling of incomplete emptying—the perception that the bladder is not fully emptied following voiding. This may or may not indicate that the person has a raised post void residual volume (Gray and Moore, 2009). | |

| Difficulty or complete inability to void—in this situation ask: Do you feel that you need to pass urine but can’t? | The two most likely causes of significant difficulty with voiding are urinary retention (acute or chronic) and oliguria or anuria (Gray and Moore, 2009). People experiencing severe pain or who have undergone surgery (especially with epidural anaesthesia) can experience transient difficulty in voiding and may require urinary catheterisation until their general health improves. Acute and chronic retention is most often associated with enlargement of the prostate in men. Acute retention can cause significant lower abdominal pain and restlessness. Chronic urinary retention can result in renal damage due to increased pressures and/or infection in the urinary tract. |

| Lack of sensation of the need to void—in this situation ask: Do you have any sensation to pass urine? Do you lose urine but have no sensation of this happening? | Lack of sensation to void is associated with neurogenic dysfunction of the bladder which can be caused by disease or injury of the central or peripheral nervous system (e.g. multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, spina bifida, diabetes mellitus). For some people the bladder contracts without the sensation of the need to void, causing urinary incontinence. For others, the bladder may fail to contract (atonic bladder) resulting in retention of urine. The bladder can retain large amounts of urine which can cause further damage to the detrusor muscle and increased pressures in the urinary tract resulting in renal damage. |

7 Other symptoms (including fever, weight gain/loss, fatigue) Fever—Have you experienced fever now or recently? Nausea and vomiting—Have you experienced nausea and/or vomiting now or recently? Anorexia? Weight gain/loss and peripheral oedema—Have you had a weight increase/loss now or recently? Do you have any swelling in your lower legs? Are you experiencing excessive thirst? |

Fever is associated with infection of the urinary tract and may be accompanied by other symptoms. The presence of a high body temperature with other symptoms such as flank pain, nausea and chills usually indicates the need for urgent referral to a medical practitioner. |

| Fatigue/lethargy—Have you experienced fatigue now or recently? For men—Erectile dysfunction (see Ch 26). Any other symptoms (e.g. headache, itching skin)? | Nausea and vomiting can accompany pain and fever or can be a sign of increased creatinine levels indicating renal failure. |

| Weight gain/loss in the person with a renal disorder is an indicator of general fluid balance. | |

| Fatigue and lethargy can be associated with chronic urinary tract disorders including renal failure. | |

8 Past history (including obstetric history) Do you or your family have any past history of renal or urinary tract health problems (infection, urinary stones, cancer)? Do you or your family have any past history neurological disorders? Are you diabetic? For how long? Current treatment? Have you had any problem with your bowel function, including constipation? History of mental health problems? For men—any history of prostate cancer in your family? For women—obstetric history: How many births? Were forceps used for any of these? Did you have an episiotomy? What were the babies’ birth weights? Did you have any bladder control issues after the births? Menopausal symptoms? Surgical history—including gynaecological, spinal, bowel surgery. |

Diabetes mellitus is a major risk factor for renal failure and bladder dysfunction. Constipation is a risk factor for urinary incontinence and voiding dysfunction. There is a higher incidence of prostate cancer in men who have a frst degree relative with the disease. Pregnancy and childbirth are risk factors for the development of urinary incontinence. Obesity is a risk factor for the development of urinary incontinence. Older people may experience acute confusion rather than the more typical symptoms of urinary tract infection (such as frequency, urgency and dysuria). |

Activity and exercise—What regular exercise do you take? Are you able to manage your personal hygiene and toileting? Smoking—How much? For how long? Continence aids and appliances—Do you use any continence aids to assist you with toileting or incontinence (e.g. commodes, urinals, toilet seats, grab bars and rails)? If so, which ones? For how long? How effective are they? Do you use any continence products to assist you with bladder leakage (e.g. pads, pants, condom (sheath) drainage catheters (sometimes referred to as external catheters))? If so which ones? For how long? How effective are they? Medications—What medications are you currently taking (both over-the-counter and prescribed)? Screening (for men over 50 years)—When did you have your last digital rectal examination of the prostate and/or prostate specific antigen test? (See ‘Promoting a healthy lifestyle’ below.) |

Some exercise activities can contribute to bladder symptoms and pelvic floor dysfunction, especially high impact activities or those which cause increased intraabdominal pressure. Smoking is a known risk factor for bladder and renal cancer and can contribute to urinary dysfunction. It is common for the person with urinary incontinence to self-manage their problem. You may need to assess the effectiveness of these aids and appliances and the person’s knowledge of matters such as skin care, fluid intake, voiding position. They may need referral to a continence nurse advisor for further assessment and advice. Many medications affect bladder function, in particular anticholinergics, antidepressants and sedatives. Polypharmacy is a major contributor to the risk of incontinence in older people. |

10 Environmental issues related to bladder function Mobility and dexterity issues—Any mobility and dexterity issues related to getting to and from the toilet and/or dressing/undressing? Do you have any vision problems? Home environment—location and access to the toilet? Work environment—location and access to the toilet, work restrictions related to fuid intake and/or going to the toilet? |

All of these factors may contribute to urinary incontinence or other voiding dysfunction and can significantly affect the person’s ability to cope with the problem. |

| Additional history for infants and children | |

| Nocturnal enuresis—involuntary passing of urine after an age at which continence is expected. |

TABLE 18.1 Urine colour and discolourations

|

OBJECTIVE DATA

Objective data collection focuses on the symptoms experienced by the person which have been revealed in the history taking. Some of the areas for objective assessment required for the assessment of urinary tract function are described in other chapters and will only be mentioned briefly below. Other relevant areas for assessment could include bowel function, skin, genitals (including digital rectal palpation of the prostate in men and vaginal examination and pelvic muscle function in women), mobility and cognitive examination. Refer to the relevant chapters for details.

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

|---|---|

| The positioning of the person is dependent on the area being assessed. |

| Procedures and normal fndings | Clinical signifcance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| VITAL SIGNS | |

| Temperature and BP—see Chapter 9. | |

| ABDOMINAL EXAMINATION | |

| Inspection, percussion and palpation of the lower abdomen to determine bladder distension (see Ch 19). Normally the bladder would not be palpable above the symphysis pubis after voiding. | Lower abdominal pain on palpation may accompany urinary retention or urinary tract infection. |

| Post-void residual bladder volume | |

| The portable bladder scanner is commonly used by nurses in hospitals and in the community to assess post-void residual urine volume. The use of this specialised piece of equipment has reduced the need for intermittent urethral catheterisation to assess residual volume. There are various scanning devices available. Most will have an integrated digital screen, a transducer which is placed on the lower abdomen and a printer for displaying the bladder volume measurements. You need to read the instructions for the scanner that you are using; however, the following are general guidelines:

• Explain the procedure to the person. • Have the person void as usual—the volume of this void should be measured. Save the sample for dipstick testing after the scan is completed. (The scan should be performed as soon as possible after the person has voided to obtain accurate results.) • Ask the person to lie down (use one pillow if tolerated) and remove clothing on the lower abdomen down to the level of the symphysis pubis. • Have the scanning device placed on a trolley beside the person. • Wipe the transducer head with an alcohol wipe and allow to dry. • Turn the device on—male or female setting (male setting for a woman who has had a hysterectomy). • Apply transmission gel to the transducer head. • Place the transducer head onto the abdomen approximately 2.5 cm above the symphysis pubis and pointing down towards the bladder. Move the transducer head around until you have the bladder positioned centrally on the scanner screen, then avoid moving the transducer during scanning process. • The scanning device will signal when the scanning is complete. • Remove the transducer head from the abdomen and clean. Offer the person tissues to wipe their abdomen and assist them if necessary to redress. |

A post-void residual volume (PVR) can lead to urinary retention, infection, hydro-nephrosis and renal insufficiency. A PVR >100 mL is generally considered to define voiding dysfunction (Getliffe and Dolman, 2007). However, an acceptable PVR is very patient specific and you should always check with the attending medical officer as to what is considered acceptable for a particular person. Keep in mind that the amount of PVR must be interpreted in light of the volume of urine the person had in their bladder in the first place. For example, if the person voided 100 mL and had a PVR of 100 mL, the finding is significant. |

• Label the printed results with the date and time, the volume voided prior to the bladder scan and the person’s name and date of birth. The printed results should be fixed into the person’s medical history/progress notes. (Note: some scanners use thermal printing that fades over time. In this case photocopy the results.) In the normal bladder there should be less than 50 mL of urine left in the bladder after voiding. In people 70 years and over, up to 100 mL is acceptable (Moore, 2006). |

|

| Examination of urine | |

• Characteristics: volume of void, colour, clarity and odour. Urine should normally be clear, light yellow coloured and have a non-offensive odour. • Collect a clean specimen of urine—you should always collect a clean specimen for urinalysis. It should never be taken from a urine drainage bag. Ask the person to void into a clean container (urinal, bed pan or clean urine measuring jug). The specimen should be tested as soon as possible after collection. For the person who has a urethral or suprapubic catheter, the drainage bag tubing should be positioned so that there are loops at the level of the bladder (so that the urine collects in the tubing rather than dripping into the urine drainage bag). When the urine has collected in the tubing draw approximately 10 mL of the urine from the access port in the tubing. (Never disconnect the tubing from the catheter to take a urine specimen: this breaks the closed system and increases the risk of urinary tract infection.) • Urinalysis—can produce quick and useful information on the person’s health status, and bladder and kidney function. It may indicate the need for further investigations such as midstream urine (MSU) for microscopy and culture. There are various brands of reagent strips available which test for a variety of urine characteristics and abnormalities. These need to be stored and used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The following are general guidelines: • Open the reagent strip container and remove a reagent strip. Avoid touching the reagent test pads on the stick.

• Dip the stick into the urine specimen making sure that all of the reagent test pads are moistened. Remove the stick, making sure that you don’t flick the stick causing spray. Start timing the test. Let the stick drain above the urine container to reduce dripping of urine.

• Some test pads can be read immediately, others require a specific time for the result to be finalised. Follow the instructions on the container regarding the time requirements.

|

See Table 18.1 for interpretation of urinalysis findings. A person should be referred for urine microscopy and culture where there is a positive finding for blood, protein, nitrates or leucocytes (Getliffe and Dolman, 2007). |

Fluid balance chart/voiding diary In hospitalised people a ‘fluid balance’ chart is commonly issued to record intake and output as well as type and amount of fluid intake and any accompanying voiding symptoms. In situations where estimation of fluid balance is vital to the overall health of the person, urinary catheterisation may be required so that accurate, frequent urine volumes may be obtained. |

Output should be roughly similar to intake. In an adult the amount of urine produced per hour is 0.5 mL/kg/hr or 30–40 mL per hour in an average sized adult. |

| A voiding diary (sometimes called a bladder chart, bladder diary or frequency/volume chart) can be used to record a person’s voiding and incontinence pattern over a period of time. The form used will depend on the information to be elicited, e.g. information on intake and types of fluids, volume voided, accompanying symptoms such as urgency, dysuria, incontinence and precipitating factors, use of continence pads. This data is sometimes combined with a bowel chart/diary. It is common practice to collect at least three full (24-hour) days of charting to establish if a voiding pattern exists. During this time the person or their carer should make no attempt to alter their usual patterns, as the purpose of the chart is to establish the person’s usual voiding patterns. You need to review the following data: | Proportion of urine voided overnight. Up to one-third of daily urine production overnight is considered normal. |

| DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS | |

| Infants and children | |

| It may be difficult to obtain an accurate measurement of urine volume in infants and young children. Observation of the number of wet nappies and the colour and concentration of urine can give an indication of urine output. In sick children, urinary catheterisation may be required to accurately measure urine output. | The expected urine output for infants and young children is 1 mL/kg/hr. |

Promoting a healthy lifestyle Understanding prostate changes

The discussion of prostate health and the examination of the prostate gland is a unique aspect of male health assessment. Men should be offered the opportunity to discuss changes in their urinary elimination patterns and sexual activity, including ejaculation. These discussions often give rise to the early signs and symptoms of prostatic changes that may indicate the need for further studies and workup.

Through much of a man’s life, the prostate gland is typically the size of a walnut. However, by the time a man is 40, it may grow slightly larger. Although this varies between individuals, this gradual enlargement is considered to be a normal part of ageing. This enlargement is termed benign prostatic hypertrophy, or BPH. It does not raise an individual’s risk for prostate cancer. However, benign enlargement of the prostate can cause significant and bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms including urinary urgency, frequency, poor stream hesitancy, post micturition dribble and acute or chronic urinary retention. Treatment can include medications, lifestyle modification and surgical interventions (typically transurethral resection of the prostate—TURP).

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer that occurs in men and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men. The risk of developing prostate cancer to age 75 years is 1 in 8 for Australian men (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2008). Despite these disturbing facts, there is still much that is not known about this disease. Prostate cancer is essentially a disease of older men with 85% diagnosed after 65 years of age (Cancer Council of Australia, 2009). Prostate cancer is rare before the age of 40 and its incidence rises rapidly after age 60. Part of the concern for men and for healthcare workers is the non-specific nature of the typical presenting signs and symptoms associated with prostate cancer. In the early stages they are likely to be asymptomatic. Prostate cancer is typically detected by testing the blood for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and/or on digital rectal exam (DRE). PSA is a substance made by the normal prostate gland. When prostate cancer develops, the PSA level increases. However, benign or non-cancerous enlargement of the prostate (BPH), age and prostatitis can also cause the PSA to increase. Ejaculation causes a temporary increase in PSA levels and men need to be instructed to abstain from ejaculation for 2 days before having their PSA level tested. If the PSA is elevated, further laboratory work and/or a transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) and biopsy may be recommended. The DRE involves a gloved, lubricated finger being inserted into the rectum. The prostate gland is located just in from of the rectum, making it possible to palpate the surface of the gland manually for nodules or hard areas that may be a developing cancer (see Ch 19 for details). Although it is less effective than the PSA blood test in finding prostate cancer, it can sometimes find cancers in men who have normal PSA levels. For this reason, both PSA and DRE are recommended to be done together when screening for prostate cancer.

DOCUMENTATION AND CRITICAL THINKING

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY

Subjective

Ms MR is a 24-year-old woman attending a general practice clinic following sudden onset today of dysuria, urinary frequency and urgency. She has no fever, nausea or flank pain but is complaining of suprapubic pain and discomfort. She has never had a urinary tract infection and has no past medical health problems or surgery. She has recently started a sexual relationship with her boyfriend of 3 months. She takes the oral contraceptive pill but no other medications.

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardization sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurology and Urodynamics. 2002;21:167–178.

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, et al. Incontinence: 4th international consultation on incontinence—Paris, 4th edn., Paris: Health Publications Ltd, 2009.

Angie MA. Accurate use of prostate specific antigen in determining risk of prostate cancer. Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2010;6(3):177–184.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia: an overview. Available at http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10607/, 2008.

Berry A. Helping children with nocturnal enuresis. Am J Nurs. 2006;106(8):56–64.

Booth J, Lawrence M, O’Neill K, et al. Exploring older people’s experiences of nocturia: a poorly recognised urinary condition that limits participation. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2010;32(9):765–774.

Burgio K, Johnson T, Goode P, et al. Prevalence and correlates of nocturia in community-dwelling older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(5):861–866.

Busuttil-Leaver R. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Practice Nurse. 2008;36(6):19–23.

Cancer Council of Australia. Cancer types: prostate cancer. Available at http://www.cancer.org.au/Healthprofessionals/cancer types/prostatecancer.htm.

Coyne KS, Wein A, Tubaro A, et al. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU International. 2009;103(Supplement):4–11.

Djavan B, Eckersberger E, Finkelstein J, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: current clinical practice. Primary Care Clinics Office Practice. 2010;37:583–597.

Doughty DB, Jensen LL. Assessment and management of the patient with faecal incontinence and related bowel dysfunction. In: Doughty DB, ed. Urinary and fecal incontinence: current management concepts. 3rd edn. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2006:457–490.

Elstad E, Taubenberger S, Botelho E, et al. Beyond incontinence: the stigma of other urinary symptoms. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;66(11):2460–2470.

Getliffe K, Dolman M. Assessing bladder function. In: Getliffe K, Dolman M. Promoting continence: a clinical and research resource. 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall; 2007:25–54.

Gray M, Moore KN. Urologic disorders: adult and pediatric care. St Louis: Mosby-Elsevier, 2009.

Gray M. Assessment and management of urinary incontinence. Nurs Pract. 2005;30(7):33–45.

Jenkins G, Kermnitz C, Tortora GJ. Anatomy and physiology: from science to life, 2nd edn. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

Jimbo M. Evaluation and management of haematuria. Primary Care Clinics Office Practice. 2010;37:461–472.

Jinbo AK, Stark MJ. Bowel and bladder management in children. In: Doughty DB, ed. Urinary and fecal incontinence: current management concepts. 3rd edn. St Louis: Mosby/Elsevier; 2006:491–547.

Juthani-Mehta M, Quagliarello V, Perrelli E, et al. Clinical features to identify urinary tract infection in nursing home residents: a cohort study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(6):963–970.

Legg V. Complications of chronic kidney disease: a close look at renal osteodystrophy, nutritional disturbances, and inflammation. Am J Nurs. 2005;105(6):40–50.

Litza JA, Brill JR. Urinary tract infections. Primary Care Clinics Office Practice. 2010;37:491–507.

Marieb EN, Hoehn K. Human anatomy & physiology, 8th edn. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings, 2010.

Midthun S, Pauer R, Bruce AW. A protocol for the urine dipstick/pad method. Journal Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing. 2006;33(4):396–400.

Moore KN. Pathology and management of acute and chronic urinary retention. In: Doughty DB, ed. Urinary and fecal incontinence: current management concepts. 3rd edn. St Louis: Mosby-Elsevier; 2006:225–253.

Newman DK, Wein A. Managing and treating urinary incontinence. Baltimore: Health Professions Press, 2009.

Schadem GR, Faerber GJ. Urinary tract stones. Primary Care Clinics Office Practice. 2010;37:565–581.

Swithinbank L, Heron J, Gontard AV, et al. The natural history of daytime urinary incontinence in children: a large British cohort. Acta Pædiatrica. 2010;99(7):1031–1036.

Thomas N, ed. Renal nursing, 3rd edn., Edinburgh: Elsevier Saunders, 2008.

Continence Foundation of Australia, http://www.continence.org.au/.

International Continence Society, http://www.icsoffice.org/.

Kidney Health Australia, http://www.kidney.org.au/.

Kidney Health New Zealand, http://www.nzkidneyfoundation.co.nz/Home/.

New Zealand Continence Association, http://www.continence.org.nz/.

Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia, http://www.prostate.org.au/articleLive/.

Prostate Cancer Foundation of New Zealand, http://www.prostate.org.nz/.