Chapter Twenty-six Male sexual and reproductive function

INTRODUCTION

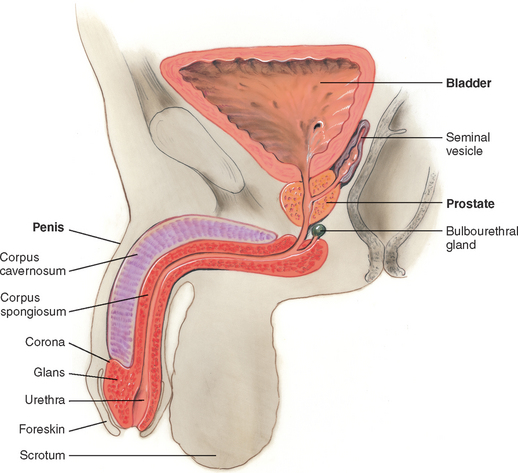

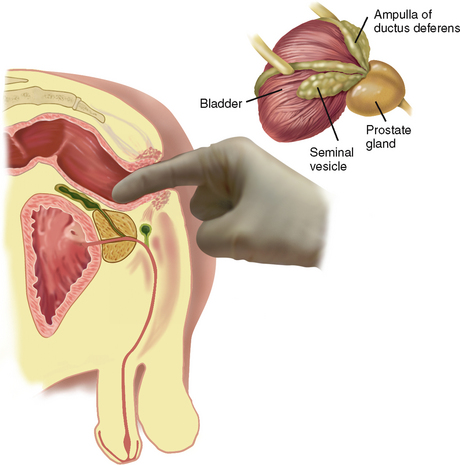

The male reproductive structures include the penis and scrotum externally and the testis, epididymis and vas deferens internally. They also include glandular structures accessory to the genital organs (the prostate, seminal vesicles and bulbourethral glands). As the organs, muscles and structures of the urinary tract, abdomen and bowel are relevant to male sexual and reproductive function you should also revise these chapters (18, 19 and 20).

THE MALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

Penis

The penis is composed of three cylindrical columns of erectile tissue: the two corpora cavernosa on the dorsal side and the corpus spongiosum ventrally (Fig 26.1). At the distal end of the shaft, the corpus spongiosum expands into a cone of erectile tissue, the glans. The shoulder where the glans joins the shaft is the corona. The urethra transverses the corpus spongiosum, and its meatus forms a slit at the glans tip (see Ch 18 for more detail on the structure of the male urethra). Over the glans, the skin folds in and back on itself, forming a hood or flap. This is the foreskin or prepuce. The frenulum is a fold of the foreskin extending from the urethral meatus ventrally.

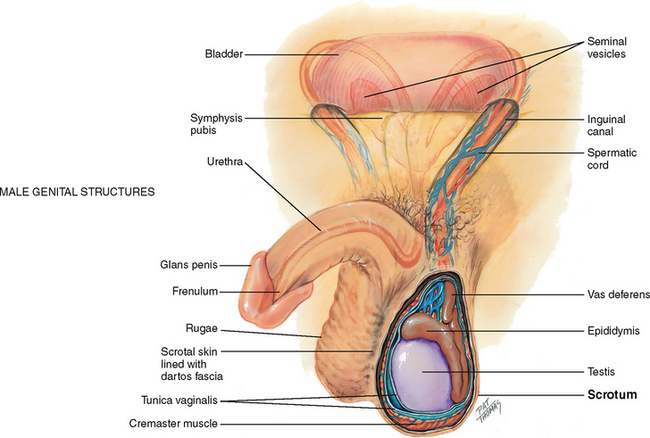

Scrotum

The scrotum is a loose protective sac, which is a continuation of the abdominal wall (Fig 26.2). After adolescence, the scrotal skin is deeply pigmented and has large sebaceous follicles. The scrotal wall consists of thin skin lying in folds, or rugae, and the underlying cremaster muscle. The cremaster muscle controls the size of the scrotum by responding to ambient temperature. This is to keep the testes at 3°C below abdominal temperature, the best temperature for producing sperm. When it is cold, the muscle contracts, raising the sac and bringing the testes closer to the body to absorb heat necessary for sperm viability. As a result, the scrotal skin looks corrugated. When it is warmer, the muscle relaxes, the scrotum lowers and the skin looks smoother.

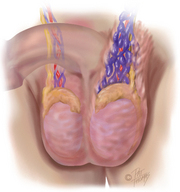

Testes

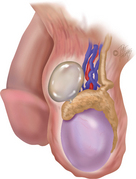

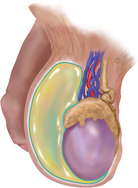

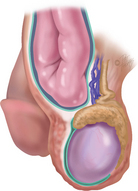

Inside the scrotum a septum separates the sac into two halves. In each scrotal half is a testis, which produces sperm. The testis has a solid oval shape, which is compressed laterally and measures 4 to 5 cm long by 3 cm wide in the adult. The testis is suspended vertically by the spermatic cord. The left testis is lower than the right because the left spermatic cord is longer. Each testis is covered by a double-layered membrane, the tunica vaginalis, which separates it from the scrotal wall. The two layers are lubricated by fluid so that the testis can slide a little within the scrotum; this helps prevent injury.

Sperm are transported along a series of ducts. First, the testis is capped by the epididymis, which is a markedly coiled duct system and the main storage site of sperm. It is a comma-shaped structure, curved over the top and the posterior surface of the testis. Occasionally (in 6% to 7% of males), the epididymis is anterior to the testis.

The lower part of the epididymis is continuous with a muscular duct, the vas deferens. This duct approximates with other vessels (arteries and veins, lymphatics, nerves) to form the spermatic cord. The spermatic cord ascends along the posterior border of the testis and runs through the tunnel of the inguinal canal into the abdomen. Here, the vas deferens continues back and down behind the bladder, where it joins the duct of the seminal vesicle to form the ejaculatory duct. This duct empties into the urethra.

The lymphatics of the penis and scrotal surface drain into the inguinal lymph nodes, whereas those of the testes drain into the abdomen. Abdominal lymph nodes are not accessible to clinical examination.

Prostate

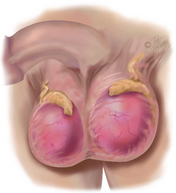

In the male, the prostate gland lies in front of the anterior wall of the rectum and 2 cm behind the symphysis pubis. It surrounds the bladder neck and the urethra and has 15 to 30 ducts that open into the urethra. The prostate secretes a thin, milky alkaline fluid that helps sperm viability. It is a bilobed structure with a round or heart shape. It measures 2.5 cm long and 4 cm in diameter. The two lateral lobes are separated by a shallow groove called the median sulcus.

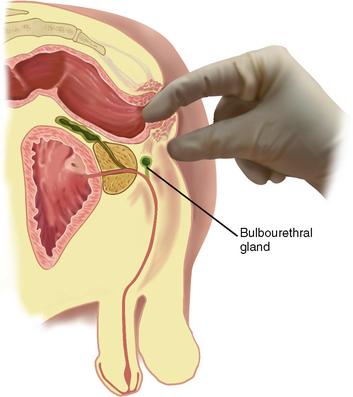

The two seminal vesicles project like rabbit ears above the prostate. The seminal vesicles secrete a fluid that is rich in fructose, which nourishes the sperm, and contains prostaglandins. The two bulbourethral (Cowper’s) glands are each the size of a pea and are located inferior to the prostate on either side of the urethra (see Fig 26.3). They secrete a clear, viscid mucus.

PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLES AND PERINEUM

The bony pelvis forms the solid structure for the muscles and ligaments of the anterior, posterior and lateral pelvic walls and pelvic floor which play such an important role in supporting the position of the pelvic organs. The pelvic floor muscles include the coccygeus muscle and the levator ani and are referred to as the pelvic diaphragm, which stretches from the pubic bone anteriorly to the coccyx posteriorly and from the right and left lateral pelvic walls. The anal canal and urethra pass through the pelvic diaphragm. The levator ani muscles support the pelvic organs and functions as a sphincter for the anal canal and urethra (Jenkins, Kemnitz and Tortora, 2010).

The perineum is located inferior to the pelvic diaphragm. The perineum extends from the symphysis pubis anteriorly to the coccyx posteriorly and the ischial tuberosities laterally. The muscles of the perineum are in two layers, superficial and deep. The superficial layer includes the superficial transverse perineal, bulbospongiosus and the ischiocavernosus muscles which help to maintain erection of the penis and facilitate ejaculation. The deep layer of the perineum includes the deep transverse perineal muscle, the external urethral sphincter and external anal sphincter which assist in maintaining urinary and faecal continence and as well as ejaculation (Jenkins, Kemnitz and Tortora, 2010).

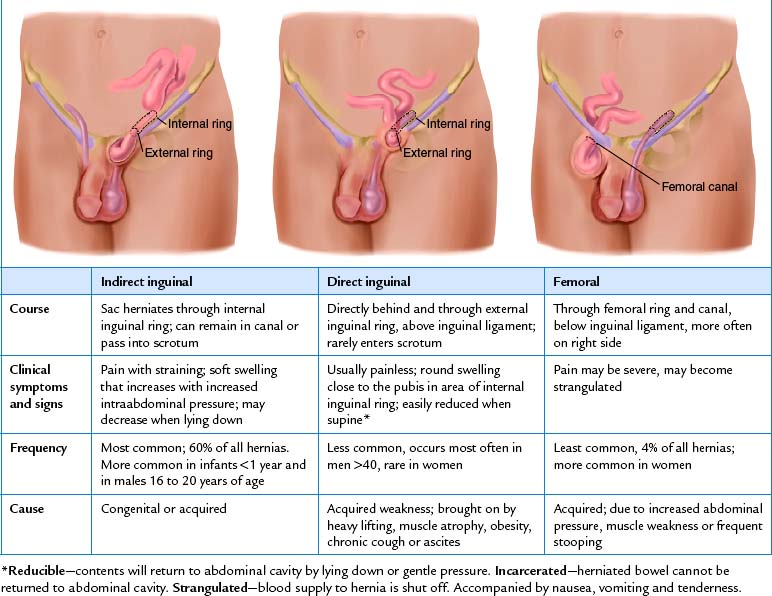

Inguinal area

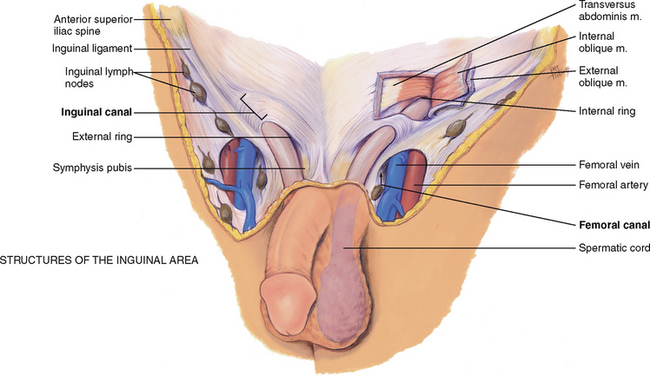

The inguinal area, or groin, is the juncture of the lower abdominal wall and the thigh (Fig 26.4). Its diagonal borders are the anterior superior iliac spine and the symphysis pubis. Between these landmarks lies the inguinal ligament (Poupart’s ligament). Superior to the ligament lies the inguinal canal, a narrow tunnel passing obliquely between layers of abdominal muscle. It is 4 to 6 cm long in the adult. Its openings are an internal ring, located 1 to 2 cm above the midpoint of the inguinal ligament, and an external ring, located just above and lateral to the pubis.

Inferior to the inguinal ligament is the femoral canal. It is a potential space located 3 cm medial to and parallel with the femoral artery. You can use the artery as a landmark to find this space.

Knowledge of these anatomical areas in the groin is useful because they are potential sites for a hernia, which is a loop of bowel protruding through a weak spot in the musculature.

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Infants

Prenatally, the testes develop in the abdominal cavity near the kidneys. During the later months of gestation the testes migrate, pushing the abdominal wall in front of them and dragging the vas deferens, the blood vessels and nerves behind. The testes descend along the inguinal canal into the scrotum before birth. At birth, each testis measures 1.5 to 2 cm long and 1 cm wide. Only a slight increase in size occurs during the prepubertal years.

Adolescents

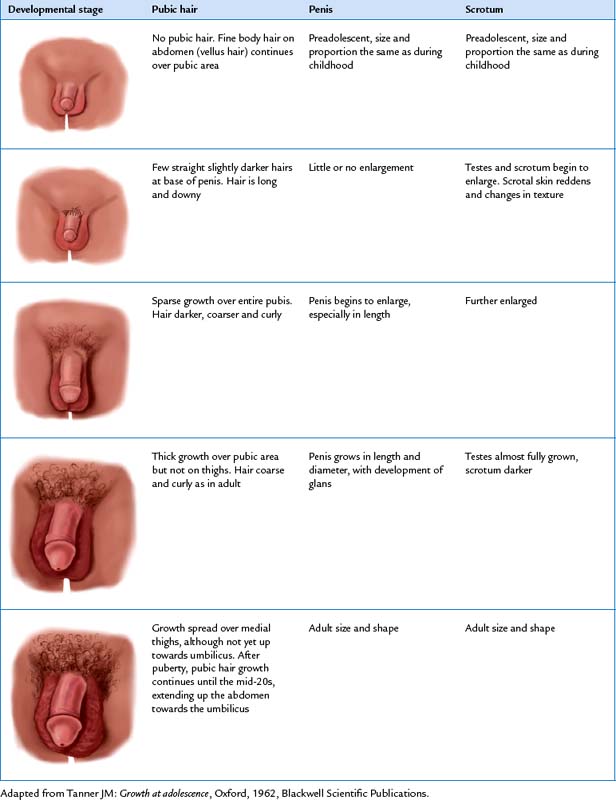

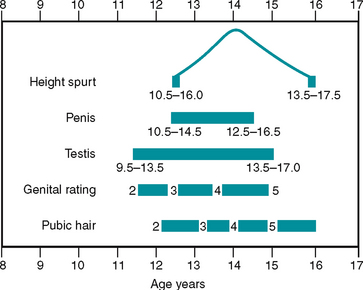

Puberty begins sometime between the ages of 9½ and 13. The first sign is enlargement of the testes. Next, pubic hair appears then penis size increases. The stages of development are documented in Tanner’s sexual maturity ratings (SMR) (Table 26.1).

The complete change in development from a preadolescent to an adult takes about 3 years, although the normal range is 2 to 5 years (Fig 26.5). The chart shown in Figure 26.5 is useful in teaching a boy the expected sequence of events and in reassuring him about the wide range of normal ages when these events are experienced.

Adults, including those over 65 years

The level of sexual development at the end of puberty remains constant through young and middle adulthood, with no further genital growth and no change in circulating sex hormone. The male does not experience a definite end to fertility as the female does. Around age 40 years, the production of sperm begins to decrease, although it continues into the 80s and 90s.

In the ageing male, the amount of pubic hair decreases, and the remaining hair turns grey. Penis size decreases. Due to decreased tone of the dartos muscle, the scrotal contents hang lower, the rugae decrease and the scrotum looks pendulous. The testes decrease in size and are less firm to palpation. Increased connective tissue is present in the tubules, so these become thickened and produce less sperm.

At male puberty, the prostate gland undergoes a very rapid increase to more than twice its prepubertal size. During young adulthood its size remains fairly constant. The prostate gland commonly starts to enlarge during the middle adult years. This benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) is present in 1 of 10 males at the age of 40 years and increases with age. It is thought that the hypertrophy is caused by hormonal imbalance that leads to the proliferation of benign adenomas. These gradually impede urine output because they obstruct the urethra.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer that occurs in men and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men. The risk of developing prostate cancer to age 75 years is 1 in 8 for Australian men (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2008). There are similar rates of prostate cancer in New Zealand men (New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2002). Prostate cancer is essentially a disease of older men with 85% diagnosed after 65 years of age (Cancer Council of Australia, 2009). Prostate cancer is rare before the age of 40 and its incidence rises rapidly after age 60. The cause of prostate cancer is unknown. Apart from advancing age and being male, the strongest established risk factor is a family history of the disease (Kirby, Partin, Feneley et al, 2006). Part of the concern for men and for healthcare workers is the nonspecific nature of the typical presenting signs and symptoms associated with prostate cancer. In the early stages they are likely to be asymptomatic. Differential diagnosis involves a health assessment and will include a prostatic specific antigen (PSA) test, digital rectal examination (DRE) and transrectal ultrasound and biopsy. However, while mass screening of men for prostate cancer (like cervical cancer screening in women) has not been recommended in Australia and New Zealand (due to lack of scientific evidence of the efficacy of mass screening), both the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia and the Prostate Cancer Foundation of New Zealand recommend that men over 50 years of age, those with a family history of prostate cancer and those with lower urinary tract symptoms should be tested for prostate cancer.

As men age their testosterone levels decline slowly from about the age of 40 years. Some older men will develop very low testosterone levels (androgen deficiency) which will cause symptoms similar to the female menopause such as fatigue, hot flushes, decreased sexual drive and osteoporosis. Although a wide range of individual differences can occur, the older male may find that an erection takes longer to develop and that it is less full or firm. Once obtained, the erection may be maintained for longer periods without ejaculation. Ejaculation is shorter and less forceful, and the volume of seminal fluid is less than when the man was younger. After ejaculation, rapid detumescence (return to the flaccid state) occurs, especially after 60 years of age. This occurs in a few seconds as compared with minutes or hours in the younger male. Erectile dysfunction is common in Australian men with 21% of men over 40 years of age reporting erectile dysfunction (Holden et al, 2005). However, lifestyle risk factors such as smoking, alcohol abuse, obesity and lack of physical activity are more likely to contribute to erectile dysfunction than chronological age.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Circumcision is a surgical procedure involving the removal of the male foreskin. It is a procedure which has been performed for thousands of years for cultural and religious reasons. There are high rates of male circumcision still practised in some countries, including the United States. However, in Australia and New Zealand, male circumcision remains a controversial procedure and is no longer routinely performed. The controversy has increased in recent years with a number of published papers and a Cochrane review that support the role of male circumcision as a means of reducing the spread of human immunodeficiency virus in developing countries especially Africa (Siegfried, Muller, Deeks et al, 2009). However, the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) position statement on circumcision (2010) affirms that ‘After reviewing the currently available evidence, the RACP believes that the frequency of diseases modifiable by circumcision, the level of protection offered by circumcision and the complication rates of circumcision do not warrant routine infant circumcision in Australia and New Zealand (p. 1)’.

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Assessment in the area of male reproductive function is closely linked to assessment of bladder function. Health issues in this area are likely to cause significant distress to the man (and their partner) and therefore you need to approach the assessment in a tactful and empathic manner. Privacy is of upmost importance and you need to establish a trusting relationship with the person. Detailed questions and physical examination techniques related to urinary and bowel function and the prostate are covered in Chapters 18 and 20. Because of the sensitive nature of this assessment you should start with a more general health assessment then focus on the specific areas.

| Assessment guidelines | Clinical significance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| If the person has any voiding issues refer to the information in Chapter 18 for specific areas for assessment. | |

| Urethral discharge occurs with infection. Some penile infections will be sexually transmitted. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) can cause pain on voiding and lower abdominal pain. All people with a suspected STI should be referred to a medical practitioner or sexual health clinic for diagnosis and treatment. | |

| • Do you perform testicular self-examination (TSE)? (See section on teaching TSE below.) | |

| • Noticed any lump or swelling on testes? | |

| • Noted any change in size of the scrotum? | |

| • Noted any bulge or swelling in the scrotum? For how long? Ever been told you have a hernia? Any dragging, heavy feeling in scrotum? | Possible hernia. |

| • For men over 40 years—Do you have a family history of prostate cancer? Have you ever had a digital rectal examination of the prostate or prostate-specific antigen blood test? | There is an increased incidence of prostate cancer in men with a first degree relative who has prostate cancer. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a glycoprotein which liquefies semen at ejaculation. It is produced by the epithelial cells lining the acini and ducts of the prostate gland. Levels can be raised in men with prostate cancer or benign enlargement, and following certain prostatic manipulations such as catheterisation, cystoscopy, biopsy, trans urethral resection and even after ejaculation. PSA levels also increase with age. |

4. Sexual activity and safe sex practices. Questions about sexual activity should be routine in review of body systems for these reasons: • Your comfort with discussion prompts person’s interest and possibly relief that topic has been introduced

– Occasionally a man notices a change in ability to have an erection when aroused. Have you noticed any changes?

|

There are validated sexual health/satisfaction and erectile function assessment tools available (e.g. the Male Sexual Health Questionnaire (MSHQ) (Rosen, Cantania, Pollack et al, 2004)). Men who are concerned about erectile function should be referred to a medical practitioner/sexual health clinic for further assessment. Erectile dysfunction can be associated with other significant health problems such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Chang, Chu, Hsu et al, 2010). • Establishes a database for comparisons with any future sexual activities • Provides opportunity to screen sexual problems. Your questions should be objective and matter-of-fact. Gay and bisexual men need to feel acceptance to discuss their health concerns. You should avoid making assumptions about a person’s sexual preference. |

| Additional history for infants and children | |

| If the infant/child has any voiding issues refer to Chapter 18 for specific areas for assessment. | |

3. Questions related to suspected child abuse. Registered nurses in Australia have a legal requirement to report suspected cases of child abuse and neglect. This is known as mandatory reporting. All Australian states and territories possess mandatory reporting requirements of some description. You should make sure that you understand the requirements within your area—http://www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/sheets/rs3/rs3.html |

For more information about signs and symptoms related to child abuse refer to Chapter 5. |

| Where appropriate, you need to make a judgment about the specific situation; however, examples of possible questions include: | |

| Has anyone ever touched your penis or in between your legs and you did not want them to? Sometimes that happens to children and it’s not okay. You should know that you have not been bad. You should try to tell a big person about it. Can you tell me three different big people you trust who you could talk to? | For prevention, teach the child that it’s not okay for someone to look at or touch their genitals while telling them it’s a secret. |

| Additional history for preadolescents and adolescents | |

| Use the following questions regarding sexual growth and development and sexual behaviour. First | |

• Ask questions that seem appropriate for boy’s age but be aware that norms vary widely. When you are in doubt, it is better to ask too many questions than to omit something. Children obtain information, often misinformation, from the media and from peers at surprisingly early ages. You can be sure your information will be more thoughtful and accurate. • Ask direct, matter-of-fact questions. Avoid sounding judgmental. • Start with a permission statement. ‘Often boys your age experience…’ This conveys that it is normal and all right to think or feel a certain way. • Try the ubiquity approach, ‘When did you…’ rather than ‘Do you…’ This method is less threatening because it implies that the topic is normal and unexceptional. • Do not be concerned if a boy will not discuss sexuality with you or respond to offers for information. He may not wish to let on that he needs or wants more information. You do well to ‘open the door’. The adolescent may come back at a future time. |

|

1. At about age 12 to 13 years, but sometimes earlier, boys start to change and grow around the penis and scrotum. What changes have you noticed? Have you ever seen charts and pictures of normal growth patterns for boys? Let us go over these now. Who can you talk to about your body changes and about sex information? How do these talks go? Do you think you get enough information? What about sex education classes at school? |

|

| An occasional boy confuses this with a sign of STI or feels guilty. | |

3. Teenage boys have other normal experiences and wonder if they are the only ones who ever had them, like having an erection at embarrassing times, having sexual fantasies or masturbating. Also, a boy might have a thought about touching another boy’s genitals and wonder if this means he might be homosexual. Would you like to talk about any of these things? |

A boy may feel guilty about experiencing these things if not informed that they are normal. |

| Assess level of knowledge. Many boys will not admit they need more knowledge. | |

| • Are you going out with someone? Have you had sexual intercourse? Are you using safe sex practices? | Avoid the term ‘having sex’. It is ambiguous, and teens can take it to mean anything from foreplay to intercourse. |

| • What kind of contraception did you use the last time you had intercourse? | This particular question often reveals that the teen is not using any method of birth control. |

| Assess knowledge of testicular self-examination. | |

6. Questions related to suspected child abuse. See previous information about your legal responsibilities regarding mandatory reporting of sexual abuse. Where appropriate, you need to make a judgment about the specific situation; however, examples of possible questions include: Has anyone ever touched your genitals and you did not want them to? Another boy, or an adult, even a relative? Sometimes that happens to teenagers. They should remember it is not their fault. They should tell another adult about it. |

For more information about signs and symptoms related to child abuse refer to Chapter 5. |

OBJECTIVE DATA

The techniques and extent of the physical examination in this area will depend on the presenting signs and symptoms. Nurses working in sexual health clinics and some urological settings may need to develop skill in a more comprehensive assessment of male sexual and reproductive function. For most nurses asking questions about the man’s reproductive health will be sufficient for a nursing assessment.

| Assessment guidelines | Clinical significance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| INSPECT THE PENIS | |

| The skin normally looks wrinkled, hairless and without lesions. The dorsal vein may be apparent (Fig 26.6). | Lesions: nodules, solitary ulcer (chancre), grouped vesicles or superficial ulcers, wart-like papules (see Table 26.2). |

| The glans looks smooth and without lesions. Ask the uncircumcised male to retract the foreskin, or you retract it. It should move easily. Some cheesy smegma may have collected under the foreskin (this is normal). After inspection, ask the man to slide the foreskin back to the original position. | |

| The urethral meatus is positioned just about centrally. | Hypospadias–ventral location of meatus. Epispadias–dorsal location of meatus (see Table 26.3). |

| At the base of the penis, pubic hair distribution is consistent with age. Hair is without lice. | Pubic lice or nits can be seen with the unaided eye. Excoriated skin usually accompanies. |

| INSPECT THE SCROTUM | |

| Inspect the scrotum as male holds the penis out of the way. Alternatively, you hold the penis out of the way with the back of your hand (Fig 26.7). Scrotal size varies with ambient room temperature. Asymmetry is normal, with the left scrotal half usually lower than the right. | |

| DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS | |

| Infants and children | |

| For an infant or toddler, perform this procedure right after the abdominal examination. In a preschool-age to young school-age child (3 to 8 years of age), leave underpants on until just before the examination. In an older school-age child or adolescent, offer an extra drape, as with the adult. Reassure child and parents of normal findings. | |

| Inspect the penis and scrotum. Penis size is usually small in infants (2 to 3 cm) (Fig 26.8) and in young boys until puberty. In the obese boy, the penis looks even smaller because of folds of skin covering the base. | |

| The urethral meatus should be located centrally in the tip of the penis. | Hypospadias, epispadias (see Table26.3). |

| The foreskin is normally tight during the first 3 months and should not be retracted because of the risk of tearing the membrane attaching the foreskin to the shaft. This leads to scarring and, possibly, to adhesions later in life. In infants older than 3 months of age, retract the foreskin gently to check the glans and meatus. It should return to its original position easily. | |

| Rugae are well formed in the full-term infant. Size varies with ambient temperature, but overall, the infant’s scrotum looks large in relation to the penis. No bulges, either constant or intermittent, are present. | |

| The adolescent | |

The adolescent shows a wide variation in normal development of the genitals. Using the sex maturity charts (Table 26.1), note: (1) enlargement of the testes and scrotum; (2) pubic hair growth; (3) darkening of scrotal colour; (4) roughening of scrotal skin; (5) increase in penis length and width; and (6) axillary hair growth. |

|

| The adult over 65 years | |

| In the older male, you may note thinner, greying pubic hair and the decreased size of the penis. The size of the testes may be decreased and may feel less firm. The scrotal sac is pendulous with less rugae. |

FURTHER OBJECTIVE ASSESSMENT FOR ADVANCED PRACTICE

The assessments that are described in the following sections require advanced skill and scope of practice. Nurses working in specialist men’s health and sexual health settings, as well as urological and continence nurses, need to develop these skills. Advanced assessment for infants and children is performed by specialist neonatal and paediatric nurses, some midwives and maternal and child health nurses.

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

|---|---|

| Position supine for most of the examination. Cover with sheet or blanket when possible. |

| Assessment guidelines | Clinical significance and clinical alerts |

|---|---|

| PALPATE THE PENIS | |

| With gloved hands, compress the glans anteroposteriorly between your thumb and forefinger (Fig 26.9). The meatus edge should appear pink, smooth and without discharge. | Edges that are red, everted, oedemat ous, along with purulent discharge, suggest urethritis (see Table 26.2). |

| If you note urethral discharge, collect a smear for microscopic examination and a culture. If no discharge shows but the man gives a history of it, ask him to milk the shaft of the penis. This should produce a drop of discharge. | |

| Palpate the shaft of the penis between your thumb and first two fingers. Normally, the penis feels smooth, semi-firm and nontender. | Nodule or induration. Tenderness. |

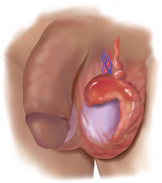

| PALPATE THE SCROTUM | |

| Spread rugae out between your fingers. Lift the sac to inspect the posterior surface. Normally, no scrotal lesions are present, except for the commonly found sebaceous cysts. These are yellowish, 1-cm nodules and are firm, nontender and often multiple. | Inflammation. |

| Palpate gently each scrotal half between your thumb and first two fingers (Fig 26.10). The scrotal contents should slide easily. Testes normally feel oval, firm and rubbery, smooth and equal bilaterally, and are freely movable and slightly tender to moderate pressure. Each epididymis normally feels discrete, softer than the testis, smooth and nontender. | Absent testis–may be a temporary migration or true cryptorchidism (see Table 26.4). Atrophied testes–small and soft. Nodules on testes or epididymides. An indurated, swollen and tender epididymis indicates epididymitis. |

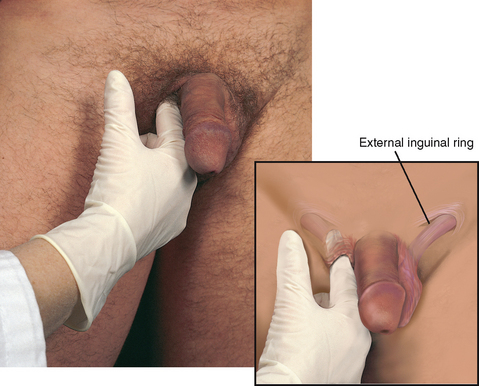

| Palpate each spermatic cord between your thumb and forefinger, along its length from the epididymis up to the external inguinal ring (Fig 26.11). You should feel a smooth, nontender cord. | Soft, swollen, and tortuous cord–see the discussion of varicocoele, Table 26.4. |

| Abnormalities in the scrotum: hernia, tumour, orchitis, epididymitis, hydro-coele, spermatocoele, varicocoele (see Table 26.4). | |

| Transillumination. Perform this manoeuvre if you note a swelling or mass. Darken the room. Shine a strong flashlight from behind the scrotal contents. Normal scrotal contents do not transilluminate. | Serous fluid does transilluminate and shows as a red glow, e.g. hydrocoele, or spermatocoele. Solid tissue and blood do not transilluminate, e.g. hernia, epididymitis or tumour (see Table 26.4). |

| INSPECT AND PALPATE FOR HERNIA | |

| With the man in a standing position, inspect the inguinal region for a bulge as he strains down. Normally, none is present. | Bulge at external inguinal ring or at femoral canal. (A hernia may be present but easily reduced and may appear only intermittently with an increase in intraabdominal pressure.) |

| Palpate the inguinal canal (Fig 26.12). For the right side, ask the male to shift his weight onto the left (unexamined) leg. Place your right index finger low on the right scrotal half. Palpate up the length of the spermatic cord, invaginating the scrotal skin as you go, to the external inguinal ring. It feels like a triangular slit-like opening, and it may or may not admit your finger. If it will admit your finger, gently insert it into the canal and ask the person to ‘bear down’.* Normally, you feel no change. Repeat the procedure on the left side. | Palpable herniating mass bumps your fingertip or pushes against the side of your finger (see Table 26.6). |

| Palpate the femoral area for a bulge. Normally you feel none. | |

| PALPATE INGUINAL LYMPH NODES | |

| Palpate the horizontal chain along the groin inferior to the inguinal ligament and the vertical chain along the upper inner thigh. | |

| It is normal to palpate an isolated node on occasion; it then feels small (less than 1 cm), soft, discrete and movable (Fig 26.13). | Enlarged, hard, matted, fixed nodes. |

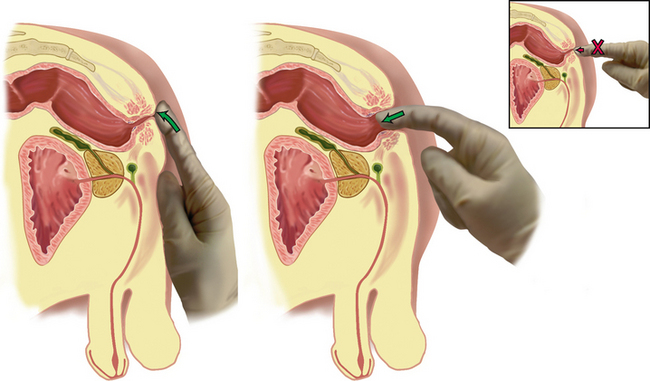

| PALPATE THE PROSTATE GLAND VIA THE RECTUM | |

| Drop lubricating jelly onto your gloved index finger. Instruct the person that palpation is not painful but may feel like needing to move the bowels. Place the pad of your index finger gently against the anal verge (Fig 26.14). You will feel the sphincter tighten, then relax. As it relaxes, flex the tip of your finger and slowly insert it into the anal canal in a direction towards the umbilicus. Never approach the anus at right angles with your index finger extended. Such a jabbing motion does not promote sphincter relaxation and is painful. | |

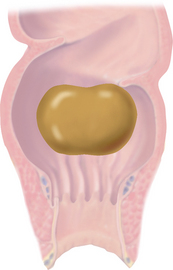

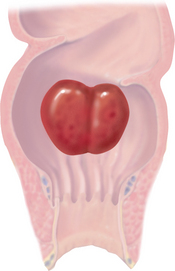

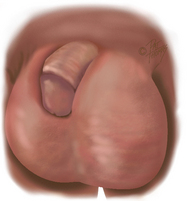

| Prostate gland. On the anterior wall in the male, note the elastic, bulging prostate gland (Fig 26.15). Palpate the entire prostate in a systematic manner, but note that only the superior and part of the lateral surfaces are accessible to examination. Press into the gland at each location, because when a nodule occurs, it will not project into the rectal lumen. The surface should feel smooth and muscular; search for any distinct nodule or diffuse firmness. Note these characteristics: | |

| Size—2.5 cm long by 4 cm wide; should not protrude more than 1 cm into the rectum | Enlarged, or atrophied gland. |

| Shape—heart shape, with palpable central groove | Flat with no groove. |

| Surface—smooth | Nodular. |

| Consistency—elastic, rubbery | Hard; or boggy, soft, fluctuant. |

| Mobility—slightly movable | Fixed. |

| Sensitivity–nontender to palpation | Enlarged, firm smooth gland with central groove obliterated suggests benign prostatic hypertrophy. Swollen, exquisitely tender gland accompanies prostatitis. Any stone-hard, irregular, fixed nodule indicates carcinoma–needs referral to medical practitioner (see Table 26.5). |

| DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS-ADVANCED PRACTICE | |

| Infants and children | |

| Palpate the scrotum and testes. The cremasteric reflex is strong in the infant, pulling the testes up into the inguinal canal and abdomen from exposure to cold, touch, exercise or emotion. Take care not to elicit the reflex: (1) keep your hands warm and palpate from the external inguinal ring down; (2) block the inguinal canals with the thumb and forefinger of your other hand to prevent the testes from retracting (Fig 26.16). | |

Normally, the testes are descended and are equal in size bilaterally (1.5 to 2 cm until puberty). It is important to document that you have palpated the testes. Once palpated, they are considered descended, even if they have retracted momentarily at the next visit. If the scrotal half feels empty, search for the testes along the inguinal canal and try to milk them down. Ask the toddler or child to squat with the knees flexed up; this pressure may force the testes down. Or, have the young child sit cross-legged to relax the reflex (Fig 26.17). |

Cryptorchidism: undescended testes (those that have never descended). Undescended testes are common in premature infants. They occur in 3% to 4% of term infants, although most have descended by 3 months of age. Age at which child should be referred differs among physicians (see Table 26.4). |

| Migratory testes (physiological cryptorchidism) are common because of the strength of the cremasteric reflex and the small mass of the prepubertal testes. Note that the affected side has a normally developed scrotum (with true cryp-torchidism, the scrotum is atrophic) and that the testis can be milked down. These testes descend at puberty and are normal. | |

Palpate the epididymis and spermatic cord as described in the adult section. A common scrotal finding in the boy under 2 years of age is a hydrocoele, or fluid in the scrotum. It appears as a large scrotum and transilluminates as a faint pink glow. It usually disappears spontaneously. Inspect the inguinal area for a bulge. If you do not see a bulge but the parent gives a positive history of one, try to elicit it by increasing intraabdominal pressure. Ask the boy to hold his breath and strain down or have him blow up a balloon. If a hernia is suspected, palpate the inguinal area. Use your little finger to reach the external inguinal ring. |

A hydrocoele is a cystic collection of serous fluid in the tunica vaginalis, surrounding the testis (see Table 26.4). |

* Avoid the old direction, ‘turn your head and cough’. For one thing, a brief cough does not give the steady, increased intraabdominal pressure you need. For another, the person is likely to cough right in your face.

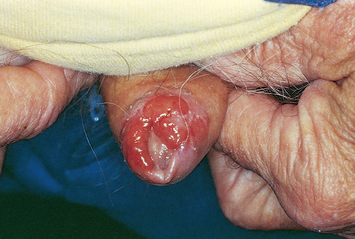

TABLE 26.2 Male genital lesions

Reprinted from Colour Atlas of Infectious Diseases, 3rd edn, Emon p. 161, 1995, by permission of the publisher Mosby.

TABLE 26.3 Abnormalities of the penis

|

| Phimosis |

| Foreskin is advanced and fixed so tight it is impossible to retract over glans. May be congenital or acquired from adhesions secondary to infection. Poor hygiene leads to retained dirt and smegma, which increases risk of inflammation or calculus formation. |

| Paraphimosis (not illustrated) |

| Foreskin is retracted and fixed. Once retracted behind glans, a tight or inflamed foreskin cannot return to its original position. Constriction impedes circulation, so glans swells. If untreated, it may compromise arterial circulation. |

|

| Hypospadias |

| Urethral meatus opens on the ventral (under-) side of glans, shaft, or at the penoscrotal junction. A groove extends from the meatus to the normal location at the tip. This is a congenital defect that is important to recognise at birth. The newborn should not be circumcised because surgical correction may use foreskin tissue to extend urethral length. |

|

| Epispadias |

| Meatus opens on the dorsal (upper) side of glans or shaft above a broad, spade-like penis. Rare; less common than hypospadias but more disabling because of associated urinary incontinence and separation of pubic bones. |

| Urethral stricture (not illustrated) |

| Pinpoint, constricted opening at meatus or inside along urethra. Occurs congenitally or secondary to urethral injury. Gradual decrease in force and calibre of urine stream is most common symptom. Shaft feels indurated along ventral aspect at the site of the stricture. |

| Priapism (not illustrated) |

| Prolonged painful erection of penis without sexual desire. Rare condition occurs with sickle-cell trait or disease; leukaemia where increased numbers of white blood cells produce engorgement; malignancy; or local trauma or spinal cord injuries with autonomic nervous system dysfunction. |

|

| Peyronie’s disease |

| Hard, nontender, subcutaneous plaques palpated on dorsal or lateral surface of penis. May be single or multiple and asymmetrical. They are associated with painful bending of the penis during erection. Plaques are fibrosis of covering of corpora cavernosa. Usually occurs after 45 years. Its cause is trauma to the erect penis, e.g. unexpected change in angle during intercourse. More common in men with diabetes, gout and Dupuytren’s contracture of the palm. |

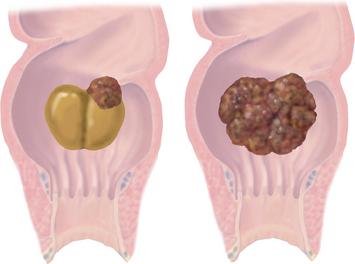

TABLE 26.4 Abnormalities in the scrotum

| Disorder | Clinical findings | Discussion |

|---|---|---|

Absent testis cryptorchidism |

True cryptorchidism–testes that have never descended. Incidence at birth is 3% to 4%; one-half of these descend in first month. Incidence with premature infants is 30%; in the adult 0.7% to 0.8%. True undescended testes have a histological change by 6 years, causing decreased spermatogenesis and infertility. | |

Small testis |

Small and soft (<3.5 cm) indicates atrophy as with cirrhosis, hypopituitarism, following oestrogen therapy, or as a sequela of orchitis. Small and firm (<2 cm) occurs with Klinefelter’s syndrome (hypogonadism). | |

Testicular torsion |

S: Excruciating pain in testicle of sudden onset, often during sleep or following trauma. May also have lower abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, no fever O: Inspection–red, swollen scrotum, one testis (usually left) higher owing to rotation and shortening Palpation–cord feels thick, swollen, tender, epididymis may be anterior, cremasteric reflex is absent on side of torsion |

Clinical alert: sudden twisting of spermatic cord. Occurs in late childhood, early adolescence, rare after age of 20 years. Torsion occurs usually on the left side. Faulty anchoring of testis on wall of scrotum allows testis to rotate. The anterior part of the testis rotates medially towards the other testis. Blood supply is cut off, resulting in ischaemia and engorgement. This is an emergency requiring surgery; testis can become gangrenous in a few hours. |

Epididymitis |

S: Severe pain of sudden onset in scrotum, somewhat relieved by elevation (a positive Phren’s sign); also rapid swelling, fever O: Inspection–enlarged scrotum; reddened Palpation–exquisitely tender; epididymis enlarged, indurated; may be hard to distinguish from testis. Overlying scrotal skin may be thick and oedematous |

Acute infection of epididymis commonly caused by prostatitis, after prostatectomy because of trauma of urethral instrumentation or due to chlamydia, gonorrhoea or other bacterial infection. Often difficult to distinguish between epididymitis and testicular torsion. |

Spermatic cord varicocoele |

S: Dull pain; constant pulling or dragging feeling; or may be asymptomatic O: Inspection–usually no sign. May show bluish colour through light scrotal skin Palpation–when standing, feel soft, irregular mass posterior to and above testis; collapses when supine, refills when upright. Feels distinctive, like a ‘bag of worms’ The testis on the side of the varicocoele may be smaller owing to impaired circulation |

A varicocoele is dilated, tortuous varicose veins in the spermatic cord due to incompetent valves within the vein, which permit reflux of blood. Most often on left side, perhaps because left spermatic vein is longer and inserts at a right angle into left renal vein. Common in young males. Screen at early adolescence; early treatment important to prevent potential infertility when an adult. |

Spermatocoele |

Retention cyst in epididymis. Cause unclear but may be obstruction of tubules. Filled with thin, milky fluid that contains sperm. Most spermatocoeles are small (<1 cm); occasionally, they may be larger and then mistaken for hydrocoele. | |

Early testicular tumour |

Most testicular tumours occur between the ages of 18 and 35. Practically all are malignant. Must biopsy to confirm. Most important risk factor is undescended testis, even those surgically corrected. Early detection important in prognosis, but practice of testicular self-examination is currently low. | |

Diffuse tumour |

Diffuse tumour maintains shape of testis. | |

Hydrocoele |

Cystic. Circumscribed collection of serous fluid in tunica vaginalis, surrounding testis. May occur following epididymitis, trauma, hernia, tumour of testis or spontaneously in the newborn. | |

Scrotal hernia |

Scrotal hernia usually due to indirect inguinal hernia (see Table 26.6). | |

Orchitis |

||

Scrotal oedema |

Accompanies marked oedema in lower half of body, e.g. congestive heart failure, renal failure and portal vein obstruction. Occurs with local inflammation: epididymitis, torsion of spermatic cord. Also obstruction of inguinal lymphatics produces lymphoedema of scrotum. |

S, Subjective data; O, objective data; A, assessment.

TABLE 26.5 Abnormalities of the prostate gland

S, Subjective data; O, objective data.

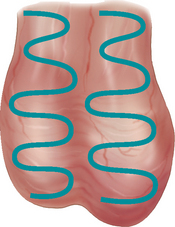

Promoting a healthy lifestyle Testicular self-examination/testicular awareness

Testicular cancer accounts for 1.2 per cent of all male cancers. The risk of developing testicular cancer to age 75 years is 1 in 212 for Australian men (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2008). A similar incidence is found in New Zealand men (New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2002). It is primarily a disease of young males, with incidence being most frequent in males aged between 15 and 40 years. Risk factors include having undescended testis, infertility, previous testicular cancer and a family history of testicular cancer (Gray and Moore, 2009). If discovered early almost all testicular cancers are curable.

Men are advised to become aware of the normal size and consistency of their testicles so that they are able to recognise any changes that may occur. Andrology Australia recommends that men perform monthly examination so that they develop a sense of what is normal for them.

Early detection is enhanced if the man is familiar with his normal consistency. Points to include during health teaching are:

• S = shower, warm water relaxes scrotal sac

• E = examine, check both testis, one at a time check for changes, report changes immediately.

For example, you could approach teaching TSE using the following points (Fig 26.18):

• A good time to examine the testicles is during the shower or bath, when your hands are warm and soapy and the scrotum is warm.

• Cold hands stimulate a muscle (cremasteric) reflex, retracting the scrotal contents. The procedure is simple. Hold the scrotum in the palm of your hand and gently feel each testicle using your thumb and first two fingers. If it hurts, you are using too much pressure. The testicle is egg-shaped and movable. It feels rubbery with a smooth surface, like a peeled hard-boiled egg. The epididymis is on top and behind the testicle; it feels a bit softer.

• If you ever notice a firm, painless lump, a hard area or an overall enlarged testicle, call your local doctor (GP) for a further check.

For more information see the following websites:

Andrology Australia: http://www.andrologyaustralia.org/

Cancer Society of New Zealand (Te Kāhui Matepukupuku o Aotearoa): http://www.cancernz.org.nz/information/mens-health/

DOCUMENTATION AND CRITICAL THINKING

FOCUSED ASSESSMENT: CLINICAL CASE STUDY

Subjective

RC is a 19-year-old student who noted acute onset of painful urination, frequency and urgency 2 days ago. Noted some thick penile discharge. States has no side pain, no abdominal pain, no fever or genital skin rash. RC is concerned he has an STI because of episode of unprotected intercourse with a new partner 6 days ago. Has no known allergies.

Atashili J. Adult male circumcision to prevent HIV? Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10(3):202–205.

Australian Institute of Family Studies. National Child Protection Clearing House. Available at http://www.aifs.gov.au/nch/.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia: an overview. Available at http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10607/, 2008.

Bickford J. Sexual history taking and genital examination. Prim Health Care. 2006;16(2):33–35.

Broom A, Tovey P. Men’s health: body, identity and social context. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2009.

Cancer Council of Australia. Cancer types: Prostate cancer. Available at http://www.cancer.org.au/Healthprofessionals/cancertypes/prostatecancer.htm, 2009.

Chang ST, Chu CM, Hsu JT, et al. Independent determinants of coronary artery disease in erectile dysfunction patients. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(4):1478–1487 (part 1).

Gray M, Moore KN. Urologic disorders: adult and pediatric care. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2009.

Harlan W, et al. Secondary sex characteristics of boys 12 to 17 years of age: the U.S. Health Examination Survey. J Pediatr. 1979;95:293.

Held-Warmkessel J, ed. Contemporary issues in prostate cancer: a nursing perspective, 2nd edn., Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2006.

Holden CA, McLachlan RI, Pitts M, et al. Men in Australia Telephone Survey (MATeS): a national survey of the reproductive health and concerns of middle-aged and older Australian men. Lancet. 2005;366:218–224.

Jenkins G, Kemnitz C, Tortora GJ. Anatomy and physiology: from science to life, 2nd edn. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

Kirby RS, Partin AW, Feneley M, et al. Prostate cancer: principles and practice. London: Informa Healthcare, 2006.

Kleier J. Nurse practitioners’ behavior regarding teaching testicular self-examination. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2004;16(5):206–218.

Marshall W, Tanner J. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:13.

Mathews BP, Walsh KM, Fraser JA. Mandatory reporting by nurses of child abuse and neglect. Journal of Law and Medicine. 2006;13(4):505–517.

New Zealand Ministry of Health. Cancer in New Zealand: trends and projections. Available at http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/0/8e1d731682cab3d9cc256c7e00764a23?OpenDocument, 2002.

Rosen RC, Catania J, Pollack L, et al. Male Sexual Health Questionnaire (MSHQ): scale development and psychometric validation. Urology. 2004;64(4):777–782.

Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Policy statement on infant male circumcision. Available at http://www.racp.edu.au/page/policy-and-advocacy/paediatrics-and-child-health, 2010.

Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, et al, Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2009. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2. Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003362

Weiss H, et al. Male circumcision and risk of syphilis, chancroid, and genital herpes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82:101–110.

Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia, http://www.prostate.org.au/articleLive/.

Prostate Cancer Foundation of New Zealand, http://www.prostate.org.nz/home.