Chapter 18 NURSING MANAGEMENT: intraoperative care

1. Outline the purpose of different areas of the perioperative/surgery department and the proper attire for each area.

2. Describe the roles and responsibilities of the members of the multidisciplinary surgical team.

3. Identify and prioritise needs experienced by the patient undergoing surgical procedures.

4. Discuss the role of the perioperative nurse in managing the care of the patient undergoing surgery.

5. Outline basic principles of aseptic technique used in the operating room.

6. Discuss the importance of physical, psychological, emotional, environmental and cultural safety in the operating room.

7. Differentiate between general, regional and local anaesthesia, including advantages, disadvantages and rationale for the choice of anaesthetic technique.

8. Identify the basic techniques used to induce and maintain general anaesthesia and administer local and regional anaesthesia.

Nursing care of the surgical patient requires an understanding of anaesthesia, pharmacology, surgery and surgical interventions. This comprehensive knowledge allows the nurse to monitor the patient’s response to the stressors related to the surgical experience. Use of the nursing process during the operative phase of care is necessary as a framework for the delivery of care. The needs of the patient, based on the patient’s current health status and the type of surgical intervention anticipated, determine the type of nursing care delivered.

Historically, surgical interventions have taken place in the traditional environment of the hospital operating room (OR) suite. However, advancements in surgical technology, improvements in the administration of anaesthesia and changes in the healthcare environment have altered where and how surgery is performed. As a result, there has been a decrease in the number of in-hospital surgical procedures and an increase in the number of day surgery or outpatient procedures in hospitals, freestanding surgery centres and doctors’ surgeries. The number of surgical procedures being performed in the day surgery setting has doubled in the last decade, thereby lowering the number of cases being performed in the hospital environment. The first freestanding day surgery unit was established in Australia in 1985 and day surgery is now well-established in the country: more than half of all hospital admissions (56%) in 2007–2008 were same-day admissions, compared with 48% in 1998–1999.1 Trends in ambulatory surgery continue with the introduction of day-of-surgery admission (DOSA) and 23-hour stay facilities for elective surgery patients.

Differences that are noted in the day surgery setting compared with the traditional in-hospital surgery setting include healthier patient populations, shorter procedure times, quicker turnovers and less time available for perioperative teaching of the patient and family. Although all surgical specialties are represented in the day surgery setting, ophthalmology, gynaecology, plastic surgery, otorhinolaryngology, orthopaedic surgery and general surgery have the highest patient loads.

Currently, approximately 50% of all surgery is conducted as day surgery.2 The perioperative nurse must remember that the surgical procedure has the same seriousness and potential for complications regardless of where it is performed. The patient, family members and care givers still have the same needs and fears. The nurse must maintain asepsis in the surgical environment, keep current on new technologies and continue to be a strong advocate for safe patient care.

This chapter describes the physical environment of the operating room suite, differentiates between the roles of various members of the surgical team and discusses the nurse’s role in the management of the physical, psychological, emotional, environmental and cultural needs of the patient during surgery.

The physical environment of the operating room suite

DEPARTMENT LAYOUT

The operating room (OR) suite is a controlled environment designed to minimise the spread of infectious organisms and allow a smooth flow of patients, personnel, and the instruments and equipment needed to provide safe patient care. The suite is divided into four distinct areas: the unrestricted, semi-restricted, restricted and transition areas. The unrestricted area is where personnel in street clothes can interact with those in surgical attire. These areas typically include the points of entry for patients (e.g. holding area), staff (e.g. locker rooms) and information (e.g. nursing station or control desk). The semi-restricted area includes the peripheral support areas and corridors, including anaesthetic rooms and postanaesthetic recovery units. Other semi-restricted areas include storage and sterile stock supply areas and sterilising departments. Only authorised personnel are allowed access to the semi-restricted areas and personnel in these areas wear appropriate perioperative attire, although this may vary across facilities. The restricted area typically includes the operating rooms (see Fig 18-1) and scrub sink areas. In this area, personal protective equipment, such as masks, is required to supplement perioperative attire. The transition area usually refers to staff changing rooms.

In addition, the physical layout is designed to reduce cross-contamination. The flow of clean and sterile supplies and equipment should be separated from contaminated supplies, equipment and waste by space, time and traffic patterns.3 Personnel move supplies from clean areas, such as clean utility rooms, through the operating room for surgery, and on to peripheral areas, such as the instrument decontamination area.3

HOLDING AREA

The holding area, frequently called the preoperative holding area, is a special waiting area inside or adjacent to the surgical suite. The size varies according to hospital design and can range from a centralised area to accommodate numerous patients to a small designated area immediately outside the actual room scheduled for the surgical procedure. In the holding area the perioperative nurse makes the final identification and assessment before the patient is transferred into the operating room for surgery. Many minor procedures can be performed in the holding area, such as inserting intravenous catheters and arterial lines, removing casts and administering drugs. All patients admitted for surgery, either as inpatients or day-of-surgery admissions, or through a surgical day care or 23-hour stay unit typically have the same journey to the operating room via the holding area. Separation from loved ones just before surgery can produce anxiety. Some institutions permit a family member or friend to wait with the patient until it is time to be transferred to the operating room in order to help relieve anxiety.

OPERATING ROOM

The traditional surgical environment, or operating room (OR), is a unique acute care setting removed from other hospital clinical units. The environment is controlled geographically, environmentally and bacteriologically, and it is restricted in terms of the inflow and outflow of personnel. Geographically, it is preferable that the OR is physically located adjacent to both the postanaesthetic recovery unit (PARU) and the intensive care unit for quick transportation of the surgical postoperative patient and close proximity to anaesthesia personnel if complications arise. This allows close collaboration for postanaesthetic recovery and intensive care follow-up.

The physical and environmental design of the operating room plays an important role not only in preventing the transmission of infection but also in promoting patient comfort and safety. The lighting is designed to provide a low- to high-intensity range for a precise view of the surgical site. Ultraviolet (UV) lighting may be used, as UV radiation reduces the number of microorganisms in the air. Standards recommend that the room temperature is controlled between 18°C and 24°C and the humidity is regulated between 40% and 60% to facilitate patient comfort under the surgical drapes and the surgical team’s comfort during the procedure.3,4 In individual operating rooms, optimising the temperature range from 20°C to 23°C can inhibit bacterial growth, and maintaining the humidity between 30% and 60% not only inhibits bacterial growth but also decreases potential risks associated with static electricity.5,6 Positive air pressure in the room prevents air from entering from the halls and corridors. Filters and controlled airflow in the ventilating systems provide dust control and play a part in reducing postoperative infections in complex surgical procedures.7 Diligence in monitoring and controlling environmental parameters enhances patient safety and promotes an environment that is well tolerated by patients and staff.

The functional design of equipment and furniture facilitates the practice of environmental cleaning in the OR. Dust-collecting surfaces, such as open shelves and tables, windows and ledges, are minimised and materials that are resistant to the corroding effects of strong disinfectants are used. Physical safety and comfort are also aided by the functional design of furniture, fixtures and other equipment. Furniture located in the OR should be adjustable, easy to clean and easy to move. All equipment must be checked frequently to ensure electrical safety.

Another important consideration in the design and function of the OR is patient privacy. This is achieved by restricting the influx of hospital personnel and visitors throughout the entire surgical suite, particularly in the OR. Restricting extra staff and visitors also preserves the aseptic environment and prevents undue noise or distractions during the operative procedure (see Fig 18-2). In addition, a communications system provides a means for the delivery of routine and emergency messages to and from the room.8

Surgical team

In preparation for and carrying out the surgical procedure, all members of the surgical team collaborate to ensure that the patient is receiving the best possible care.

PERIOPERATIVE NURSE

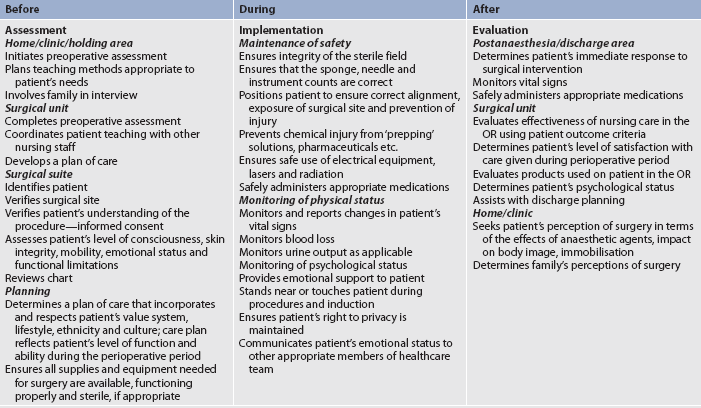

The perioperative nurse plans, directs and implements patient care during the perioperative period based on the nursing process. The highest quality patient-focused nursing care during anaesthesia and the surgical intervention is achieved by a registered nurse (RN; also called a Division 1 Registered Nurse) performing in the role of anaesthetic nurse, circulating nurse and instrument nurse.9 Enrolled nurses (ENs; also called Division 2 Registered Nurses) undertaking these roles must be supervised by an experienced registered nurse and work within their defined scope of practice as determined by the relevant registering authority.9 There are opportunities for nurses in the perioperative environment to focus on different aspects of the patient’s perioperative experience (preoperative, intraoperative or postoperative) and to develop specific skills and knowledge. Examples of nursing activities that characterise each phase surrounding the surgical experience are presented in Table 18-1.

Before the patient’s arrival in the OR, the nurse, through close collaboration with the other members of the surgical team, prepares the OR for the patient. This is commonly the shared responsibility of several nurses acting in distinct roles, as anaesthetic assistant, instrument (or scrub) nurse and circulating (or scout) nurse. The role of anaesthetic assistant may be fulfilled by a perioperative nurse or a qualified anaesthetic technician.

When the patient arrives from home or is transported from the acute care inpatient area to the holding area, the perioperative nurse is usually the first member of the surgical team that the patient encounters. The perioperative nurse is the patient’s advocate throughout the intraoperative experience.10 This entails protecting the patient and communicating with the patient, as well as carrying out the patient assessment to determine any additional needs before surgery and to meet the patient’s individual plan of care. The nurse provides preoperative education regarding the upcoming experience and physical comfort measures. In addition, the nurse works with the patient’s family and/or significant others, keeping them informed and answering questions. This is particularly important in day surgery areas where families may have less contact with staff members and must assume greater responsibility for preoperative and postoperative care.11

During the patient’s intraoperative phase of care, different functions may be assumed by the perioperative nurse, which involve either sterile or unsterile activities. The perioperative nurse can serve in the role of circulating nurse when not scrubbed, gowned and gloved and remain in the unsterile field. If the nurse follows the designated scrub procedure, is gowned and gloved in sterile attire and remains in the sterile field, the role of instrument nurse is implemented. Some specific intraoperative activities of each function are outlined in Table 18-2.

TABLE 18-2 Intraoperative activities of the perioperative nurse

• Reviews anatomy, physiology and the surgical procedure.

• Assists with preparation of the surgical list.

• Practises aseptic technique in all required activities.

• Monitors practices of aseptic technique in self and others.

• Ensures that needed items are available and sterile (if required).

• Checks mechanical and electrical equipment and environmental factors.

• Identifies and admits the patient to the OR suite.

• Assesses the patient’s physical and emotional status.

• Plans and coordinates the intraoperative nursing care.

• Checks the documentation and relates pertinent data.

• Admits the patient to the OR suite.

• Assists with transferring the patient to the OR bed.

• Assures patient safety in transferring and positioning the patient.

• Participates in insertion and application of monitoring devices.

• Monitors the draping procedure.

• Implements infection control principles.

• Documents intraoperative care.

• Records, labels and sends to proper locations tissue specimens and cultures.

• Measures blood and fluid loss.

• Records amount of drugs used during local anaesthesia.

• Coordinates all activities in the room with team members and other health-related personnel and departments.

• Counts sponges, needles and instruments.

• Accompanies the patient to the postanaesthesia recovery area.

• Reports information relevant to the care of the patient to the recovery area nurses.

Instrument nurse/sterile activities

• Reviews anatomy, physiology and the surgical procedure.

• Assists with preparation of the surgical list.

• Scrubs, gowns and gloves self and other members of the surgical team.

• Prepares the instrument table and organises sterile equipment for functional use.

• Assists with the draping procedure.

• Passes instruments to the surgeon and assistants by anticipating the surgeon’s needs.

• Counts sponges, needles and instruments.

• Monitors practices of aseptic technique in self and others.

• Keeps track of irrigation solutions used in order to calculate blood loss.

• Reports amounts of local anaesthesia and adrenaline solutions used by anaesthetist and/or surgeon.

The perioperative nurse acting as circulating nurse is responsible and accountable for all activities occurring during a surgical procedure, including, but not limited to, the management of personnel, equipment, supplies and the environment during the surgical procedure, and managing the flow of information to and from the surgical team members scrubbed at the field. The circulating nurse is responsible for documenting the perioperative care of the patient, such as the surgical position, pack and instrument count, and nursing interventions. Documentation may be written or electronic. The Australian College of Operating Room Nurses (ACORN) publishes the ACORN standards for perioperative nursing including nursing roles, guidelines, position statements.9 The Perioperative Nurses College of the New Zealand Nurses Organisation also publishes the Recommended standards, guidelines and policy statements for safe practice in the perioperative setting.12 The ACORN standards relate to the delivery of nursing care in the perioperative setting to ‘the highest standards of patient care and professional competencies in the operating suite’.9 Documentation of the assessment and identification of clinical problems, diagnoses and intervention differentiates the perioperative nurse’s role from that of other members of the surgical team.

The perioperative nurse acting as instrument nurse is responsible for maintaining the integrity, safety and efficiency of the sterile field throughout the surgical procedure. Knowledge of and experience with aseptic and sterile techniques qualify the instrument nurse to prepare and arrange instruments and supplies and to facilitate the surgical procedure by providing the required sterile instruments and supplies. The instrument nurse must anticipate, plan for and respond to the needs of the surgeon and other team members by constantly watching the sterile field.

The perioperative nurse actively implements nursing care throughout the patient’s surgical experience. The majority of behaviours of perioperative nurses reflect critical thinking regarding safe patient care. The nurse must anticipate the needs of not only the patient but also other members of the team. Ongoing assessment of the patient is essential because the patient’s condition may change quickly and the perioperative nurse must respond to these changes and revise the plan of care as needed.

PERIOPERATIVE NURSE SURGEON’S ASSISTANT

Nursing roles in the perioperative setting change and evolve as technology and healthcare change. One of these changes is the development of the perioperative nurse surgeon’s assistant (PNSA) as an extended practice role. The PNSA works in collaboration with the surgeon to produce an optimal surgical outcome for the patient. The ACORN revised position statement for PNSAs states that the perioperative nurse who undertakes the role of surgeon’s assistant shall meet the appropriate educational requirements, be suitably experienced and demonstrate competence in the role. Duties may include deep retraction and tissue handling, provision of haemostasis, insertion of sutures, and patient preparation and transfer to the PARU.13

SURGEON AND SURGEON’S ASSISTANT

The surgeon is the specialist medical practitioner who performs the surgical procedure. The surgeon may be selected by the patient’s general practitioner or by the patient. The surgeon is primarily responsible for the following:

1. preoperative medical history and physical assessment, including the need for surgical intervention, the choice of surgical procedure and the management of preoperative diagnostic tests and the discussion of the risks of and alternatives to surgical intervention

The surgeon’s assistant is usually a medical officer (surgical resident or registrar) who functions in an assisting role during the surgical procedure. The assistant usually holds retractors to expose surgical areas and assists with haemostasis and suturing. In some instances, especially in educational settings, the assistant may perform some portions of the operative procedure under the direct supervision of the surgeon. In some institutions the surgeon’s assistant is a registered nurse who functions in the role of the assistant under the direct supervision of the surgeon. Organisational policies define this role and the surgeon’s responsibilities when a medical officer is not available to fill the assistant’s position.

ANAESTHETIST

An anaesthetist is a medical doctor who has completed a program of study in the field of anaesthesia and has credentials from the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA).14 The anaesthetist is qualified to administer anaesthetics to the patient and assume responsibility for the maintenance of physiological homeostasis throughout the intraoperative period. A qualified anaesthetist in combination with an anaesthetic registrar may provide anaesthesia.

The anaesthetist accepts the following responsibilities:

1. Assess the patient preoperatively to determine the safest anaesthetic for the particular patient’s needs and anticipated operative procedure.

2. Prescribe preoperative and adjunctive medications.

3. Monitor the patient’s cardiac and respiratory status.

4. Monitor the patient’s vital signs throughout the procedure.

5. Administer the anaesthetic during the surgical procedure and inform the surgeon if difficulties arise during the patient’s anaesthetic course.

6. Administer fluids and electrolytes, medications and blood products throughout the surgical procedure.

7. Supervise the postanaesthesia recovery of the patient in the PARU and document the patient’s postanaesthetic recovery in the first 24 hours.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: THE PATIENT BEFORE SURGERY

NURSING MANAGEMENT: THE PATIENT BEFORE SURGERY

The preoperative assessment of the surgical patient establishes baseline data for intraoperative and postanaesthesia care. Assessment data that are provided by the patient and family in the holding area and data from the inpatient nursing units are verified and are important to ensure that a plan of care can be developed.

Psychosocial assessment

Psychosocial assessment

The perioperative nurse who cares for the patient in the OR should be knowledgeable about the ongoing activities that occur when a patient is transferred into the surgical suite. This knowledge ensures informative and reassuring explanations, especially to the anxious patient. The perioperative nurse can usually answer general questions regarding surgery or anaesthesia. Examples of these questions include, ‘When will I go to sleep?’, ‘Who will be in the room?’, ‘When will my doctor arrive?’, ‘How much of my body will be exposed and to whom?’, ‘Will I be cold?’, ‘When will I wake up?’. Specific questions relating to details of the surgical procedure and anaesthesia may be referred to the surgeon or anaesthetist.

Cultural assessment

Cultural assessment

It is especially important that the perioperative nurse has knowledge of the patient’s spiritual and cultural habits and beliefs in order to understand the patient’s response to the surgical experience (see Ch 2 for cultural assessment and considerations). Culturally competent care and safety are important, and healthcare professionals must consider the cultural implications of their practices on others. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses may refuse blood transfusions.15 For Muslims, the left hand is considered unclean, so the nurse should use the right hand to administer forms, drugs and treatments.16 Body piercings may have cultural meaning for certain peoples.17 Indigenous Australians and Māori have customs and practices associated with their culture, identity, gender and healthcare that may impact on the delivery of care within the surgical context. For instance, in Māori culture, all body parts are considered sacred and they must be disposed of according to cultural traditions or returned to the patient or family.18 Language is also a part of culture and an interpreter may be necessary for patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Spiritual needs, attitudes and expressions regarding pain and health beliefs and practices also need to be considered in the individualised plan of care. It is the perioperative nurse’s responsibility to engender trust and care must be taken to ensure that cultural practices are identified and respected.

Physical assessment

Physical assessment

A thorough history and physical assessment made during the preoperative preparation of the patient (see Ch 17) will provide the perioperative nurse with knowledge to ensure patient safety. Physical assessment data that are specifically important to intraoperative nursing care include baseline data, such as vital signs, height, weight and age; allergic reactions to food, drugs and latex; condition and cleanliness of the skin; skeletal and muscle impairments; perceptual difficulties; level of consciousness; nil by mouth (NBM) status; and any sources of pain or discomfort.

Baseline vital signs are important to evaluate the effects of intraoperative medications and body positioning. The patient’s height and weight guide the decision regarding the width and length of the operating bed. The patient’s age, metabolic problems and planned surgical procedures may warrant the need for extra warmth. Some allergic reactions may be avoided with such simple measures as a change in ‘prepping’ solutions or the type of tape used with dressings. Catastrophic allergic reactions can possibly be avoided if sensitivity, for instance to latex, is determined before the procedure begins. (See the discussion of latex allergies in Ch 13.) The condition and cleanliness of the skin determine the amount and type of intraoperative skin preparation solutions and will alert the team to the potential for infection as a result of open or closed skin lesions. Assessment of the skin may also provide an opportunity to identify physical factors suggestive of abuse and/or neglect. Knowledge of skeletal and muscle impairments helps prevent injury during positioning. Knowledge of the presence of piercings will allow jewellery to be removed to prevent site burns when using electrosurgery. Perceptual difficulties, such as a vision or hearing impairment, will guide the nurse in adapting communication techniques to individual needs. An altered level of consciousness necessitates increased safety and protection techniques. Communicating identified sources of pain to other health team members prevents subjecting the patient to unnecessary discomfort. Knowledge of the patient’s medication history can also be valuable in ensuring patient safety.

The increased use of herbs and dietary supplements has increased the risk of complications for patients undergoing surgery. Herbs can potentially inhibit coagulation, alter blood pressure, cause sedation, have cardiac effects or alter electrolyte levels (see the Complementary & alternative therapies box).

Documentation

Documentation

The required documentation varies with hospital policy, patient condition and specific surgical procedures. Because day surgery facilities tend to have a healthier population, fewer tests may be required. Examples of data that are obtained during the preoperative assessment include the following:

1. history and physical examination

7. other diagnostic tests (e.g. computed tomography [CT] scan)

8. pregnancy testing (if applicable)

Knowledge of these data contribute to an understanding of past and present history, cardiopulmonary status and potential for infection.

Admitting the patient

Admitting the patient

Hospital policy designates the exact procedure that should be followed when admitting the patient to the holding area and the OR suite. A general routine includes initial greeting, extension of human contact and warmth, and proper identification. The identification process includes asking patients to state their name, their surgeon’s name and the operative procedure and location. In addition, the hospital identification numbers are compared with the patient’s own identification band and chart. Before anaesthesia induction the surgeon may further identify the patient. In some institutions identification may take place in the holding area and, in others, in the OR itself.

Complementary and alternative therapies, such as therapeutic touch, aromatherapy and music therapy, guided imagery and humour, are some of the integrative caring–healing therapies that are being used for surgical patients. (See the Complementary & alternative therapies box and Ch 7.)These therapies may decrease anxiety, promote relaxation, reduce pain and accelerate the healing process.4,19 In some facilities these are initiated before the patient’s admission to the OR. In others, such as day surgery settings, they may be started after the patient’s arrival in the holding area.

The admitting procedure is continued with reassessment of the patient and with time allowed for last-minute questions. The nurse completes the review of the documentation for the previously mentioned data, including informed consent, and notes any abnormalities or changes. The patient is questioned concerning valuables, prostheses, and last intake of food and fluid. Validation is made that the correct preoperative medication was given, if ordered. A warm blanket, pillow or position adjustment is provided if the patient is uncomfortable. Most hospitals require the patient’s hair to be covered just before transfer to the OR suite to reduce potential shedding. A prophylactic antibiotic may be started within 30 to 60 minutes before the surgical incision. If the hair at or around the incision site will interfere with the surgery, it is removed, preferably with electric clippers.

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Music is an ancient healing tool recognised in the writings of Plato.

Clinical uses

Music can be used to: (1) decrease stress, anxiety and pain; (2) improve cognitive functioning; (3) alter mood states; (4) promote relaxation and sleep; and (5) enhance alertness. Music can be used in many different clinical settings, including occupational and physiotherapy, elder care facilities, operating or procedure rooms, and hospices. Playing music in the background, while a person is seemingly unaware of the music itself, can reduce stress.

Preoperatively, music can be used to decrease anxiety.** Before and during surgery music can be used to distract the attention of patients from their discomfort and the sounds of the equipment and staff. Surgical patients exposed to music have diminished analgesic and hypnotic requirements during conscious sedation. Postoperatively, music can decrease pain and the need for analgesics.

Effects

Music can have many different physiological effects. Listening to calming music can result in slower, deeper breathing and a decrease in heart rate and blood pressure—an indication of relaxation. Music with a faster pace can energise a person and promote mental alertness. Often music from the patient’s own culture is most effective.

Nursing implications

To be effective, music selection needs to be appropriate for the situation. There is not a single type of music that is good for everyone. People have different tastes. It is important that the patient likes the music being played. There are no known side effects of this low-cost intervention. It is also well suited as a self-care technique. Combining music with relaxation therapy is more effective than doing relaxation therapy alone. Additional information can be found at www.musictherapy.org.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: THE PATIENT DURING SURGERY

NURSING MANAGEMENT: THE PATIENT DURING SURGERY

Preparing the operating room

Preparing the operating room

Before transferring the patient into the scheduled OR, the nurse spends significant time preparing the room to ensure privacy and safety and prevention of infection. Surgical attire (pants and shirts, masks, protective eyewear, and caps or hoods) is worn by all persons entering the OR suite (see Fig 18-3). All electrical and mechanical equipment is checked for proper functioning. Aseptic technique is used as each surgical item is opened and placed systematically on the instrument table.20 Sponges or packs, needles and instruments are counted to ensure accurate retrieval at the close of the procedure.21

During this time and during the procedure the functions of the team members are delineated. The instrument nurse will scrub hands and arms, don sterile gown and gloves, and touch only those items in the sterile field. The circulating nurse remains in the unsterile field and implements those activities that permit touching all unsterile items and the patient. Every person on the surgical team must share the responsibility for monitoring aseptic practice and initiating corrective action when a sterile field is compromised.

Transferring the patient

Transferring the patient

Once the patient has been properly identified and the OR has been adequately prepared, the patient is transported into the room for surgery. Each time a patient is transferred from one bed to another, the wheels of the trolley should be locked, and a sufficient number of personnel should be available to transfer the patient and prevent accidental falling. Hospitals and surgical centres may have ‘no lift’ policies to minimise injury to patients and personnel, so nurses should be familiar with the particular policy for their organisation. Once on the OR table, the patient should be safely secured. At this time the monitor leads (e.g. ECG leads), blood pressure cuff and pulse are usually applied and an intravenous catheter is inserted if it was not in place when the patient arrived from the holding area.

Scrubbing, gowning and gloving

Scrubbing, gowning and gloving

Surgical hand antisepsis is required of all sterile members of the surgical team (scrub assistant, surgeon and assistant). This is done to eliminate dirt, skin oil and transient microorganisms; to decrease the microbial count as much as possible; and to inhibit rapid rebound growth of microorganisms.22 The agent used for antisepsis should be an effective antimicrobial agent. It should significantly reduce microorganisms on the skin; contain a non-irritating, antimicrobial preparation; be broad spectrum and fast acting; and have a persistent effect.22 The procedure should be standardised for all personnel. When the procedure of scrubbing is the chosen method for surgical hand antisepsis, the team members’ fingers and hands should be scrubbed first, with progression to the forearms and elbows. The hands should be held away from surgical attire and higher than the elbows at all times to prevent contamination from clothing or detergent suds and water from draining from the unclean area above the elbows to the clean and previously scrubbed areas of the hands and fingers.22 Waterless, alcohol-based agents are replacing antimicrobial agents and water in many facilities. When a waterless hand scrub product is chosen, the team members should first wash and dry their hands and forearms with soap and water.22

Once surgical hand antisepsis is completed, the team members enter the OR to put on the surgical gowns. Current literature supports scrubbed personnel wearing powder-free or latex-free gloves to protect patients and themselves from powder and latex sensitivity,23,24 as well as wearing two pairs of gloves to protect patients and themselves from the transmission of microorganisms.25 Because the gowns and gloves are sterile, it is permissible for scrubbed team members to manipulate and organise all sterile items for use during the procedure.

Following basic aseptic technique

Following basic aseptic technique

To prevent infections, aseptic technique is practised in the OR. This is implemented through the creation and maintenance of a sterile field (see Fig 18-4). The centre of the sterile field is the site of the surgical incision. Inanimate items in the sterile field include surgical items and equipment that have been sterilised by appropriate sterilisation methods.

Figure 18-4 A sterile field is maintained during surgery.

Reproduced with permission from Central Medical Illustration Unit, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Queensland Department of Health.

There are specific principles that the team members should understand to practise aseptic technique. Unless these principles are followed, the safety of the patient will be compromised and the potential for postoperative infection will increase. Box 18-1 presents the basic principles of aseptic technique.20

BOX 18-1 Principles of basic aseptic technique in the operating room

1. All materials that enter the sterile field must be sterile.

2. If a sterile item comes in contact with an unsterile item, it is contaminated.

3. Contaminated items should be removed immediately from the sterile field.

4. Sterile team members must wear only sterile gowns and gloves; once dressed for the procedure, they should recognise that the only parts of the gown considered sterile are the front from chest to table level and the sleeves to 50 mm above the elbow.

5. A wide margin of safety must be maintained between the sterile and unsterile fields.

6. Tables are considered sterile only at tabletop level; items extending beneath this level are considered contaminated.

7. The edges of a sterile package are considered contaminated once the package has been opened.

8. Bacteria travel on airborne particles and will enter the sterile field with excessive air movements and currents.

9. Bacteria travel by capillary action through moist fabrics and contamination occurs.

10. Bacteria harbour on the patient’s and the team members’ hair, skin and respiratory tracts, and must be confined by appropriate attire.

In addition to following the principles of aseptic technique, the surgical team is responsible for following the guidelines established by the relevant authorities and organisations to protect the patient and the team from potential exposure to blood-borne pathogens, which in the OR environment can be high. Examples include guidelines from the relevant Occupational Health and Safety Acts of Australia and New Zealand, ACORN26 and the Perioperative Nurses College of the New Zealand Nurses Organisation.12 These guidelines emphasise standard and transmission-based precautions, engineering and work practice controls, and the use of personal protective equipment, such as gloves, gowns, aprons, caps, face shields, masks and protective eyewear (see Fig 18-3).

Assisting the anaesthetist

Assisting the anaesthetist

While the perioperative nurse checks the OR to complete its preparation, the anaesthetist and the anaesthetic assistant prepare the patient for the administration of the anaesthetic. The anaesthetist and the anaesthetic assistant work together closely to provide optimal patient care preoperatively, and during induction, maintenance and emergence of anaesthesia. The nurse must understand the mechanism of anaesthetic administration and the pharmacological and physiological effects of the agents. Prior to the patient entering the OR or the anaesthetic preparation room, the anaesthetic assistant is responsible for preparing the environment for specific surgical and anaesthetic techniques. This includes requirements for airway management, fluid replacement therapy, invasive and non-invasive monitoring devices, and continuance of normothermia. The anaesthetic machine will be checked according to guidelines at the commencement of each operating list. Its proper functioning is crucial for patient safety. The nurse should be prepared for potential emergency situations by knowing the location of all emergency drugs and equipment in the OR area. In some ORs the anaesthetic assistant is not a nurse but a technician. Anaesthetic technicians would be required to work within their scope of practice as integrated members of the surgical team.

The circulating non-sterile perioperative nurse may be involved in placing monitoring devices that will be used during the surgical procedure (e.g. urinary catheter, ECG leads) and the diathermy plate. If the patient is to have a general anaesthetic, the nurse remains at the patient’s side to ensure safety and to assist the anaesthetist. These responsibilities may include obtaining blood pressure measurements and assisting in the maintenance of the patient’s airway. During the surgical procedure, the perioperative nurse also provides a vital communication link between the anaesthetist and ancillary departments such as pathology or blood bank.

Positioning the patient

Positioning the patient

Positioning the patient is a critical part of every procedure and usually follows administration of the anaesthetic. The anaesthetist will indicate when to begin positioning. The position of the patient should allow for accessibility to the operative site, administration and monitoring of anaesthetic agents, and maintenance of the patient’s airway. When positioning for the surgical procedure, care must be used to: (1) provide correct skeletal alignment; (2) prevent undue pressure on nerves, skin over bony prominences, and eyes; (3) provide for adequate thoracic expansion; (4) prevent occlusion of arteries and veins; (5) provide modesty in exposure; and (6) recognise and respect individual needs, such as previously assessed aches, pains or deformities. It is a nursing responsibility to secure the extremities, provide adequate padding and support, and obtain sufficient physical or mechanical help to avoid unnecessary straining of self or patient.27

Various positions in which the patient may be placed include supine, prone, Trendelenburg, lateral, lithotomy and sitting. The supine is the most common position used. It is suited for surgery involving the abdomen, heart and breast. The prone position allows easy access for back surgeries (e.g. laminectomies). The lithotomy position is used for some types of pelvic organ surgery (e.g. vaginal hysterectomy).

Whatever position is required for the procedure, great care should be taken to prevent injury to the patient. Because anaesthesia has blocked the nerve impulses, the patient will not feel pain or discomfort, or stress being placed on the nerves, muscles, bones and skin. Improper positioning could potentially result in muscle strain, joint damage, pressure ulcers, nerve damage and other untoward effects.

General anaesthesia causes peripheral vessels to dilate. Therefore, position changes affect where the pooling of blood occurs. If the head of the OR bed is raised, the lower torso will have increased blood volume and the upper torso may become compromised. Hypovolaemia and cardiovascular disease can further compromise the patient’s status. Consequently, the perioperative nurse, working with the entire surgical team, carefully plans and implements the patient’s positioning, and then closely monitors the patient throughout the surgical procedure.27

Preparing the surgical site

Preparing the surgical site

The purpose of skin preparation, or ‘prepping’, is to reduce the number of organisms available to migrate to the surgical wound. A member of the surgical scrub team, usually the person assisting the surgeon, performs the task of prepping.

The skin is prepared by mechanically scrubbing or cleansing around the surgical site with antimicrobial agents. These agents should be broad-spectrum activity, fast acting and persistent, and identified as non-irritating or non-allergenic to the patient.28 The area is then scrubbed in a circular motion. The principle of scrubbing from the clean area (site of the incision) to the dirty area (periphery) is observed at all times.21,22 A liberal area is cleansed to allow for added protection and unexpected occurrences during the procedure.29 If the patient is very hairy or if the hair will interfere with the surgical procedure, the nurse or theatre technician removes hair before the surgical scrub using clippers.30 After preparation of the skin, the sterile members of the surgical team drape the area. Only the site to be incised is left exposed.

Safety considerations

Safety considerations

All surgical procedures, regardless of where they take place, can put the patient at risk of injury. These injuries comprise infections, physical trauma from positioning or equipment used and physiological effects of the surgery itself. For example, smoke particles produced during laser procedures may contain trace hydrocarbons, including acetone, isopropanol, toluene, formaldehyde and cyanide. These airborne contaminates can cause respiratory irritation and have mutagenic and carcinogenic potential. Smoke evacuators may be used to minimise this exposure.31 Also, care must be taken with the correct placement of the grounding pad and all aspects of the electrosurgical equipment to prevent injury from burns or fire.32 Perioperative nurses must minimise pooling of prep solutions, which can cause chemical burns on skin or catalysts for fires.29

Wrong patient, wrong site and wrong procedure incidents are also a major safety consideration that can be prevented. In 2003, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (now known as the Joint Commission) developed the first national patient safety goals to assist accredited healthcare institutions to address patient safety concerns. This incorporated a ‘Universal protocol’ for preventing wrong site, wrong procedure and wrong person surgery.33 In response to an increase in reported incidents, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, with permission, adopted these guidelines and adapted them to the Australian context.34 In support, ACORN has developed a position statement regarding correct patient, correct site and correct procedure.35 More recently, the World Health Organization has developed a ‘Surgical safety checklist’,36 which both the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons and the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists have incorporated into their practice guidelines.37,38 This safety procedure requires all members of the surgical team to stop what they are doing during a surgical time out just before the procedure is started to verify patient identification, surgical procedure and surgical site.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: THE PATIENT AFTER SURGERY

NURSING MANAGEMENT: THE PATIENT AFTER SURGERY

Through constant observation of the surgical progress and good team communication, the anaesthetist anticipates the end of the surgical procedure and uses appropriate types and doses of anaesthetic agents so that their effects will be minimal at the end of the surgical procedure. This also allows greater physiological control of the patient during the transfer to the PARU.

The anaesthetist and the perioperative nurse or another member of the surgical team accompany the patient to the PARU. A report of the patient’s status and procedure is communicated to the PARU staff to promote safe, continuing care. The OR nurse evaluates the patient’s response to nursing care based on outcome criteria established when the plan of care was developed (see Table 18-3).39

TABLE 18-3 Outcome criteria—perioperative nursing data set: outcome statements

• The patient is free from signs and symptoms of injury caused by extraneous objects.

• The patient is free from signs and symptoms of chemical injury.

• The patient is free from signs and symptoms of electrical injury.

• The patient is free from signs and symptoms of injury related to positioning.

• The patient is free from signs and symptoms of laser injury.

• The patient is free from signs and symptoms of radiation injury.

• The patient is free from signs and symptoms of injury related to transfer/transport.

• The patient receives appropriate medication(s) safely administered during the perioperative period.

Domain: physiological responses

• The patient is free from signs and symptoms of infection.

• The patient has wound/tissue perfusion consistent with or improved from baseline levels established preoperatively.

• The patient is at or returning to normothermia at the conclusion of the immediate postoperative period.

• The patient’s fluid, electrolyte and acid-base balances are consistent with or improved from baseline levels established preoperatively.

• The patient’s respiratory function is consistent with or improved from baseline levels established preoperatively.

• The patient’s cardiovascular function is consistent with or improved from baseline levels established preoperatively.

• The patient demonstrates and/or reports adequate pain control throughout the perioperative period.

• The patient’s neurological function is consistent with or improved from baseline levels established preoperatively.

Domain: behavioural responses—patient and family

• The patient demonstrates knowledge of expected responses to the operative or invasive procedure.

• The patient demonstrates knowledge of nutritional requirements related to the operative or other invasive procedure.

• The patient demonstrates knowledge of medication management.

• The patient demonstrates knowledge of pain management.

• The patient participates in the rehabilitation process.

• The patient demonstrates knowledge of wound healing.

• The patient participates in decisions affecting his or her perioperative plan of care.

• The patient’s care is consistent with the perioperative plan of care.

• The patient’s right to privacy is maintained.

• The patient is the recipient of competent and ethical care within legal standards of practice.

• The patient receives consistent and comparable care regardless of the setting.

• The patient’s value system, lifestyle, ethnicity and culture are considered, respected and incorporated in the perioperative plan of care.

Source: Reprinted with permission from AORN. Standards, recommended practices, and guidelines. 2005. Copyright © AORN, Inc., 2170 south parker Road, suite 300, Denver, CO 80231.

Anaesthesia

The art and science of anaesthesia have changed dramatically in the last 20 years. Advances in anaesthesia allow anaesthetists to use newer drugs, techniques and sophisticated equipment to ensure safe and pain-free surgery.7 For example, the bispectral index monitor, introduced in the 1990s, allows the anaesthetist to track the level of patient awareness (i.e. awareness monitoring) during surgery. The use of regional anaesthetics (some with indwelling catheters for postoperative pain control) facilitates the transition from inpatient recovery to early discharge. Anaesthetists effectively use modes of medication delivery that facilitate early discharge to home.

Although the anaesthetic technique and agents are selected by the anaesthetist in collaboration with the surgeon and the patient, the ultimate responsibility for the choice of anaesthetic remains the responsibility of the anaesthetist. Factors contributing to the choice of anaesthetic include the patient’s current physical, mental and emotional health status and history; the expertise of the anaesthetist; factors relating to the operative procedure such as length of surgery, position, site and discharge plans; as well as any contraindications and the patient’s refusal of any anaesthetic technique or agent. The anaesthetist validates this information during the preoperative assessment, obtains anaesthesia consent, writes orders for the preoperative medication and assigns the patient an anaesthesia classification.40,41

CLASSIFICATION OF ANAESTHESIA

The anaesthesia classification, an independent guideline for the anaesthetist, is based on the physiological status of the patient with no regard to the surgical procedure to be performed. A scale of I to VI is used, with I being a normal healthy patient, V being a moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the operation and VI classifying a patient who is brain-dead and whose organs are being removed for donor purposes. An intraoperative complication is more likely to develop with a higher classification number (see Table 17-3).4

Anaesthesia is classified according to the effect that it has on the patient’s sensorium (central nervous system) and pain perception. These classifications include general anaesthesia, local anaesthesia and sedation/analgesia, with the latter often used for procedures performed outside of the OR. General anaesthesia is the loss of sensation with loss of consciousness, skeletal muscle relaxation, analgesia and elimination of the somatic, autonomic and endocrine responses, including coughing, gagging, vomiting and sympathetic nervous system responsiveness. Local anaesthesia is the loss of sensation without loss of consciousness. Local anaesthesia may be induced topically or via infiltration intracutaneously or subcutaneously. Conscious sedation (‘twilight sleep’) is a minimally depressed level of consciousness with maintenance of the patient’s protective airway reflexes. The primary goal of conscious sedation is to reduce the patient’s anxiety and discomfort and to facilitate cooperation. Often a combination of sedative–hypnotic and opioid drugs is used.42 Conscious sedation retains the patient’s ability to maintain their own airway and to respond appropriately to verbal commands, yet achieves a level of emotional and physical acceptance of a painful procedure (e.g. colonoscopy). Regional anaesthesia is the loss of sensation to a region of the body without loss of consciousness when a specific nerve or group of nerves is blocked with the administration of a local anaesthetic (e.g. spinal, epidural or peripheral nerve block).

GENERAL ANAESTHESIA

Traditionally, general anaesthesia was induced primarily through the use of inhalation agents that provided a complete anaesthetic. Today the anaesthetist has the choice of a variety of anaesthetic agents and techniques to meet the predominant goal of anaesthesia (i.e. to facilitate a faster return to baseline function and thereby decrease the risk of anaesthesia). To this end, the intravenous and inhalation agents used today have a faster onset with a shortened duration of action to facilitate earlier discharge from both the PARU and the outpatient surgery facilities.

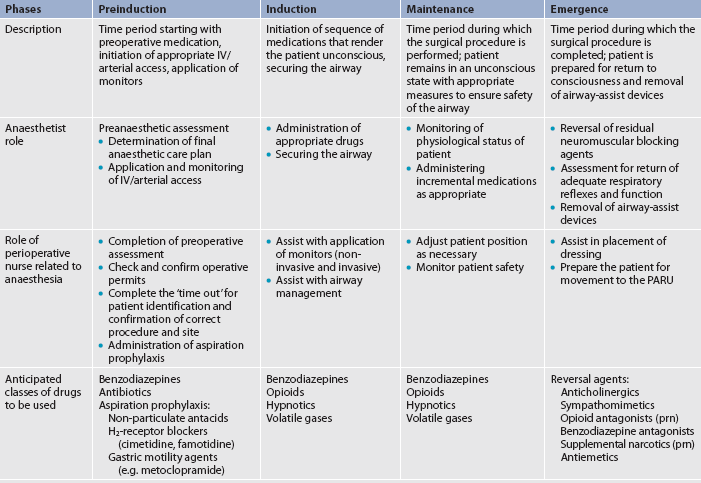

General anaesthesia is usually the technique of choice for patients who: (1) are having surgical procedures that require significant skeletal muscle relaxation, last for long periods of time, require awkward positions because of the location of the incision site or require control of respiration; (2) are extremely anxious; (3) refuse or have contraindications for local or regional anaesthetic techniques; and (4) are uncooperative because of their emotional status, lack of maturity, intoxication, head injury or pathophysiological processes that do not permit them to remain immobile for any length of time. Phases of general anaesthesia are presented in Table 18-4.

TABLE 18-4 Phases of general anaesthesia

IV, intravenous; PARU, postanaesthetic recovery unit; prn, as required.

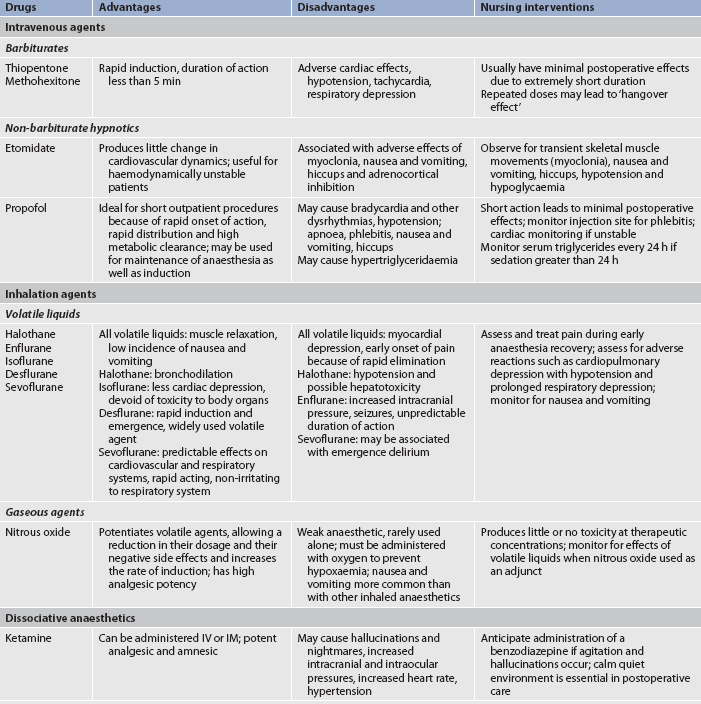

General anaesthesia may be administered intravenously or by inhalation and maintained by either one or a combination of the two. A balanced technique (use of drugs from different classes) is the most common method used for general anaesthesia. Table 18-5 presents common anaesthetic drugs with advantages, disadvantages and nursing interventions that are indicated for patients receiving the agents.

Intravenous induction agents

Virtually all routine general anaesthetics begin with an intravenous induction agent, whether it is a hypnotic, an anxiolytic or a dissociative agent. When used during the initial period of anaesthesia, these agents induce a pleasant sleep with a rapid onset of action that patients find desirable. A single dose lasts only a few minutes, which is long enough for a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) or an endotracheal tube to be placed and an inhalation agent to be started.

Recent advances in intravenous anaesthetics have created a new type of general anaesthesia known as total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA). During TIVA, all medications are delivered intravenously via a continuous infusion, thus eliminating the need for inhalation agents. This method of delivery, as opposed to intermittent bolus doses, provides an equivalent level of sedation with the benefit of a smaller total drug dosage. Continuous monitoring of the pump and the intravenous lines is critical while using this technique, as the delivery of anaesthetic agents is entirely dependent on proper functioning. The patient may still require advanced airway management, such as endotracheal intubation, and will receive oxygen/air mixtures via the endotracheal tube.

Inhalation agents

Inhalation agents are the foundation of general anaesthesia. The inhalation agents used for general anaesthesia may be volatile liquids (liquids at room temperature) or gases (gases at room temperature). Volatile liquids are administered through a specially designed vaporiser after being mixed with oxygen as a carrier gas. This gas mixture is then delivered to the patient via the anaesthesia circuit/apparatus. Waste gases are removed using a negative evacuation pressure system, or ‘scavenger’, venting to outside of the institution.

Inhalation agents enter the body through the alveoli in the lungs. They may be administered through a mask, an endotracheal tube, an LMA or a tracheostomy. Ease of administration and rapid excretion by ventilation makes them desirable agents. One undesirable characteristic is an irritating effect on the respiratory tract. Complications that may arise are coughing, laryngospasm (muscular constriction of the larynx), bronchospasm, increased secretions and respiratory depression.43 The newer, less soluble agents (e.g. desflurane) enable faster induction and emergence from general anaesthesia.

Inhalation agents are most commonly administered via an LMA or an endotracheal tube placed into the trachea after the patient has been induced with an intravenous agent. The endotracheal tube permits control of ventilation and airway protection, both for patency and to prevent aspiration. An LMA is currently a viable option for patients with difficult airways, but does not provide tracheal isolation with the same certainty that endotracheal tubes provide. Complications of endotracheal tube or LMA use include those primarily associated with insertion and removal. These include failure to intubate, damage to teeth and lips, laryngospasm, laryngeal oedema, postoperative sore throat and hoarseness caused by injury or irritation of the vocal cords or surrounding tissues.

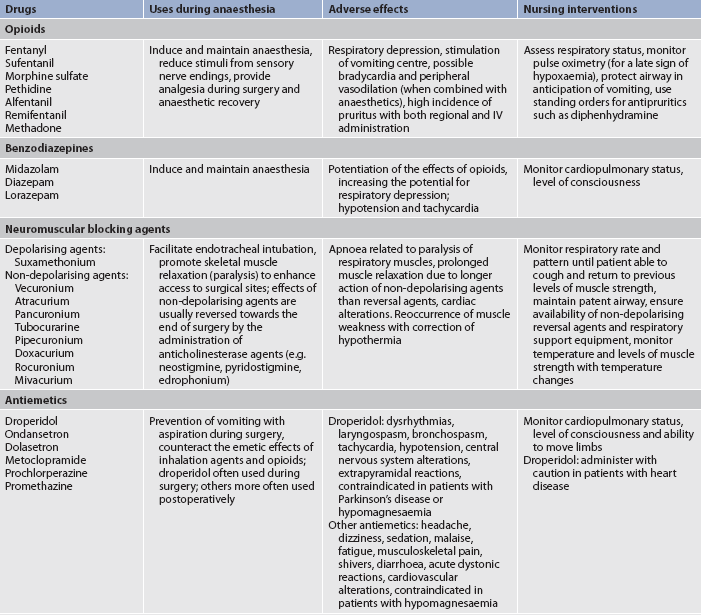

Adjuncts to general anaesthesia

The administration of general anaesthesia is rarely limited to one agent. Drugs added to an inhalation anaesthetic (other than an intravenous induction agent) are termed adjuncts. These agents are added to the anaesthetic regimen specifically to achieve unconsciousness, analgesia, amnesia, muscle relaxation or autonomic nervous system control. Adjuncts include opioids (narcotics), benzodiazepines, neuromuscular blocking agents (muscle relaxants), antiemetics and dissociative anaesthesia. It is important that the nurse know that these drugs are often given in combination and may have synergistic or antagonistic effects. The nurse may observe deeper levels of sedation or more drug-related side effects beyond those seen with inhalation anaesthetics alone. Table 18-6 lists commonly used adjunct agents, their uses during anaesthesia, adverse effects and nursing interventions.

Opioids

Opioids are used preoperatively for sedation and analgesia, intraoperatively for induction and maintenance of anaesthesia, and postoperatively for pain management. Opioids alter the perception of pain and the response to painful stimuli. When administered before the end of a surgical procedure, the residual analgesia often carries over into the PARU, allowing the patient to awaken relatively pain-free.

All opioids produce dose-related respiratory depression.44 A decreased arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) recorded by pulse oximetry is a late sign of respiratory depression. Assessment of respiratory rate and depth is critical in the management of the patient who has received opioids. Opioid-induced respiratory depression can be reversed with naloxone. However, its use is often associated with a reversal of the analgesic effects of the opioids as well.

Benzodiazepines

Sedative–hypnotic benzodiazepines are widely used for premedication before surgery for their amnesic effects, as agents for the induction and maintenance of anaesthesia, for conscious sedation, as supplemental intravenous sedation during local and regional anaesthesia, and for postoperative anxiety and agitation. Because of its excellent amnesic property, shorter duration of action and absence of pain on injection, midazolam is presently the most frequently used benzodiazepine. The other agents are limited in their usefulness because of their long duration of action. In both day surgery settings and conscious sedation, midazolam is the most commonly used anaesthesia adjunct. It is mainly administered intravenously or via intramuscular injection. Flumazenil is a specific benzodiazepine antagonist that may be used to reverse marked benzodiazepine-induced respiratory depression.45 However, the use of a reversal agent may also cause unwanted or untoward side effects.

Neuromuscular blocking agents

Neuromuscular blocking agents (muscle relaxants) are used as adjuncts to general anaesthesia to facilitate endotracheal intubation and to optimise surgical working conditions by providing relaxation (paralysis) of skeletal muscles. They interrupt the transmission of nerve impulses at the neuromuscular junction. Based on their mechanisms of action, neuromuscular blocking agents are classified as either depolarising or non-depolarising muscle relaxants. The effects of non-depolarising muscle relaxants are frequently reversed towards the end of the surgery by the administration of anticholinesterase agents (e.g. neostigmine, pyridostigmine).46 This stage of anaesthesia is referred to as emergence. The anaesthetist will suction the oropharynx to decrease the risk of aspiration and laryngospasm before extubation (removal of the endotracheal tube).

The disadvantages of the use of muscle relaxants are of special concern to the anaesthetist and postanaesthesia nurse. The duration of their action may be longer than the surgical procedure or reversal agents may not be effective in completely eliminating the residual effects. The patient should be carefully observed for airway patency and adequacy of respiratory muscle movement. Change of patient temperature can greatly alter the metabolism and effectiveness of neuromuscular blocking agents. Therefore, temperature should be closely monitored. For example, a patient who arrives in the PARU with a temperature of 35.4°C is strong and easily managing his or her airway. As the patient is warmed to a temperature of 36.7°C, weakness induced by the action of the neuromuscular blocking drugs may reoccur. Lack of movement or poor return of reflexes and strength may indicate the need for an artificial airway and ventilator. If the patient is intubated, the endotracheal tube should not be removed without careful assessment of return of muscular strength, level of consciousness and the minute volume (respiratory rate multiplied by tidal volume [amount of air inhaled and exhaled during normal ventilation]).

Antiemetics

Antiemetics are used preoperatively, intraoperatively and postoperatively to prevent and treat nausea and vomiting associated with the administration of anaesthesia. Antiemetics are used prophylactically in patients who are most at risk of nausea and vomiting. Risk factors include gender, age, smoking history, history of motion sickness and history of prior postoperative nausea.47,48 At highest risk is the female non-smoker with a history of motion sickness. An additional risk factor is the surgical procedure. High-risk procedures include abdominal or gynaecological laparoscopic procedures, facial cosmetic procedures and a variety of ear, nose and throat procedures. Treatment includes the use of medications from more than one drug class along with appropriate hydration. The antiemetics listed in Table 18-6 are most frequently used preoperatively or postoperatively.

Dissociative anaesthesia

Dissociative anaesthesia interrupts associative brain pathways while blocking sensory pathways. The patient may appear catatonic, is amnesic and experiences profound analgesia that lasts into the postoperative period. Ketamine is a commonly administered dissociative anaesthetic. Ketamine is particularly advantageous because it can be administered intravenously or intramuscularly; it is a potent analgesic and amnesic. Some examples of its usage are in asthmatic patients undergoing surgery because it promotes bronchodilation, in trauma patients requiring surgery and in patients with acute hypovolaemic shock because it increases the heart rate and helps maintain cardiac output. Because ketamine is a phencyclidine (PCP; phenylcyclohexylpiperidine) derivative, it may cause hallucinations and nightmares, particularly in adult patients, greatly limiting its usefulness.49 Concurrent use of midazolam has been found to effectively reduce or eliminate hallucinations associated with ketamine. The perioperative nurse should provide a quiet, unhurried environment in the PACU for all patients receiving dissociative anaesthesia.

LOCAL ANAESTHESIA

Local anaesthetics block the initiation and transmission of electrical impulses along nerve fibres by altering the flow of sodium into nerve cells through cell membranes. With progressive increases in local anaesthetic concentration, the transmission of autonomic, then somatic sensory and finally somatic motor impulses is blocked. This produces autonomic nervous system blockade, anaesthesia and skeletal muscle paralysis in the area of the affected nerve.

Local anaesthesia allows an operative procedure to be performed on a particular part of the body without loss of consciousness or sedation. Because there is little systemic absorption of the drug, recovery is rapid with little residual drug ‘hangover’. The duration of action of the local anaesthetic frequently carries over into the postoperative period, providing continued analgesia.50 In addition, the use of a local anaesthetic in a regional technique provides an alternative to a general anaesthetic in a physiologically compromised patient. Patients with comorbidities that would preclude general anaesthesia are now offered surgical solutions with increased safety.

There are a variety of methods for administering local anaesthetics (see Table 18-7). They can be injected at the surgical site, nebulised or applied topically. Local infiltration is the injection of the agent into the tissues through which the surgical incision will pass. The success of injected local anaesthetics may be limited by prolonged duration of the procedure or infection at the injection site, thus interfering with drug absorption. A local anaesthetic, such as lidocaine or lignocaine (xylocaine), is applied to a specific area of the body by the surgeon or anaesthetist and does not require sedation or loss of consciousness.

TABLE 18-7 Methods for administering local anaesthesia

Topical application, with or without compression, of creams, ointments, aerosols and liquids is a standard method of administration. It involves applying the agent directly to the skin, mucous membranes or open surface. Eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics (EMLA) cream, a combination of lignocaine and prilocaine, can be applied to the skin to produce localised dermal anaesthesia. EMLA should be applied to the site 30–60 minutes before painful procedures.

In day surgery or outpatient procedures the nurse may assist a medical practitioner in the administration of a peripheral or ‘field’ anaesthesia block. Consequently, the nurse must be familiar with the drugs, the methods of administration, and adverse and toxic effects of the drugs. Initial assessment of the patient should include detailed questioning of the patient’s history with local anaesthetics and any adverse events associated with the use of local anaesthetics experienced by the patient or blood relatives.

The disadvantages of local anaesthetics include the technical difficulty and discomfort that may be associated with injections, inadvertent intravenous administration producing hypotension and potential seizures, and the inability to precisely match the duration of action of the agents administered to the duration of the surgical procedure. Many patients will report ‘allergies’ to local anaesthetics. While true allergies to local anaesthetics occur, it is rare. Allergies are most likely to be a result of additives or preservatives in the preparation. Moreover, many local anaesthetics are combined with adrenaline solutions. They may be absorbed in the tissues or inadvertently injected intravenously, thus entering the general circulation causing tachycardia, hypertension and a general perception of panic. There are two classes of local anaesthetics: esters and amides. It is highly unlikely that an individual is allergic to both. Therefore, it is important to carefully question the patient concerning the agent and the symptoms experienced so that an agent in the proper class may be selected for the procedure.

REGIONAL ANAESTHESIA

Regional nerve block

Regional nerve block (also called peripheral nerve block) is achieved by the injection of a local anaesthetic into or around a specific central nerve (e.g. spinal) or group of nerves (e.g. plexus) that innervate a site remote to the point of injection. Examples of common regional nerve blocks include brachial plexus blocks, intercostal and retrobulbar blocks, and femoral, axillary, cervical, sciatic and ankle blocks. Another common regional nerve block is the intravenous regional nerve block (Bier block), which involves the intravenous injection of a local anaesthetic into an extremity following mechanical exsanguination using a compression bandage and a tourniquet. This type of block provides not only analgesia, but also the ability to work in a bloodless field. A fully functioning double-cuff tourniquet is vital to the safety of the patient. The function and status of the tourniquet should be checked and documented immediately prior to use.

Administration of a regional anaesthetic may involve concomitant use of sedation/analgesia, either preinjection or intraoperatively. Regional blocks are now used preoperatively as analgesia, intraoperatively to manage surgical pain and postoperatively to control pain. Indwelling catheters that deliver local anaesthetic via a pump to the surgical site may be implanted before the patient emerges in order to deliver continuous pain relief up to 72 hours postoperatively. Regional nerve blocks may also be used for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pain.

Whenever a patient is prepared for regional anaesthesia, airway equipment, emergency drugs and a cardiac monitor/defibrillator should be immediately available to provide advanced airway and cardiopulmonary support if necessary. Intravenous injection of the agent or excessive absorption of bupivacaine (sensorcaine), in particular, may lead to cardiac depression, severe dysrhythmias or cardiac arrest. Recent research has focused on the use of a 20% lipid emulsion (intralipid) to prevent cardiac arrest from bupivacaine toxicity.51,52

The perioperative nurse can facilitate the success of regional anaesthesia by assisting in patient positioning, monitoring vital signs during block delivery and administering oxygen therapy and supporting devices used to contribute to the anaesthesia (e.g. ultrasound imaging, nerve stimulator, tourniquets).

Spinal and epidural anaesthesia

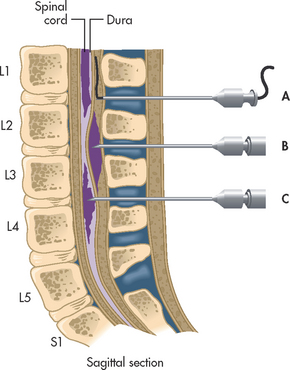

Spinal and epidural anaesthesia are also types of regional anaesthesia (see Fig 18-5). Spinal anaesthesia involves the injection of a local anaesthetic into the cerebrospinal fluid found in the subarachnoid space, usually below the level of L2. The local anaesthetic mixes with cerebrospinal fluid and, depending on the extent of its spread, various levels of anaesthesia are achieved. Because the local anaesthetic is administered directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, a spinal anaesthetic produces an autonomic, sensory and motor blockade. Patients experience vasodilation and may become hypotensive as a result of the autonomic block, feel no pain as a result of the sensory block and be unable to move as a result of the motor block. The duration of action of the spinal anaesthetic depends on the agent selected and the dose administered. A spinal anaesthetic may be used for procedures involving the lower abdomen, groin, perineum or lower extremities (e.g. joint replacements) and for lower gastrointestinal, prostate and gynaecological surgeries.

Figure 18-5 Location of needle point and injected anaesthetic relative to dura. A, Epidural catheter. B, Single-injection epidural. C, Spinal anaesthesia. (Interspaces most commonly used are L4–5, L3–4 and L2–3.)

An epidural block involves injection of a local anaesthetic into the epidural (extradural) space via either a thoracic or a lumbar approach. The anaesthetic agent does not enter the cerebrospinal fluid but works by binding to nerve roots as they enter and exit the spinal cord. By using a low concentration of local anaesthetic, sensory pathways are blocked but motor fibres remain intact. In higher doses, both sensory and motor fibres are blocked. Epidural anaesthesia may be used as the sole anaesthetic for a surgical procedure, or a catheter may be placed to enable intraoperative use, with continued use into the postoperative period so as to provide analgesia. This method of postoperative analgesia uses lower doses of epidurally administered local anaesthetic, usually in combination with an opioid.50 Epidural anaesthesia is commonly used alone or in combination with sedation/analgesia or general anaesthesia for obstetrics, vascular procedures involving the lower extremities, hip and knee replacement surgeries, lung resections, and renal and midabdominal surgeries. The desirable effects of vasodilation and analgesia contribute to better surgical outcomes.

During the surgical procedure when spinal or epidural anaesthesia is used, the patient can remain fully conscious, or intravenous sedation can be achieved. The onset of spinal anaesthesia is faster than that seen with an epidural, but the end results with either approach are usually similar. Both spinal and epidural anaesthesia may be extended in duration using indwelling catheters, thus allowing additional doses of anaesthesia to be administered. The patient must be closely observed for signs of autonomic nervous system blockade, including hypotension, bradycardia, nausea and vomiting. There is less autonomic nervous system blockade with epidural anaesthesia as compared with spinal anaesthesia. Should ‘too high’ a block be achieved, the patient may experience inadequate breathing and apnoea.50

Complications of spinal/epidural anaesthesia include postdural puncture headache, back pain, isolated nerve injury and meningitis. One advantage of epidural (extradural) injection over spinal (subarachnoid) injection is a decreased incidence of headache. A headache may be experienced after spinal anaesthesia if leakage of spinal fluid occurs at the site of injection. The incidence of headache is decreasing with the common use of smaller-gauge spinal needles (25- to 27-gauge) and the use of non-cutting, ‘pencil-point’ spinal needles.

ADDITIONAL ANAESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS

Controlled hypotension is a technique used to decrease the amount of expected blood loss by lowering the blood pressure during the administration of anaesthesia. By effectively decreasing blood loss this technique also provides better wound visualisation. Examples of when this technique may be used include during joint replacement surgery, transurethral resection of the prostate and cerebral aneurysm surgery. Hypothermia is the deliberate lowering of body temperature to decrease metabolism, thus reducing both the demand for oxygen and anaesthetic requirements. Intentional hypothermia is routinely used once a patient undergoes cardiopulmonary bypass during cardiac surgery. It is pertinent to note that unintentional hypothermia has serious physiological consequences for the perioperative patient, including cardiac dysrhythmias, alterations in level of consciousness and renal impairment. Cryoanaesthesia involves cooling or freezing a localised area to block pain impulses. Following lung resection, a cryoanaesthesia probe may be used intraoperatively to freeze the intercostal nerves and produce long-lasting analgesic effects. Hypnoanaesthesia uses hypnosis to produce an alteration in pain consciousness. Acupuncture is also used to decrease sensation (see Ch 7).53

Gerontological considerations: the patient during surgery

Although anaesthetic agents have become safer and more predictable, older people often demonstrate varying and unique responses to medications, due to alterations in the onset, peak and duration of medications administered by any route. As a result, anaesthetic drugs should be carefully titrated when given to older adults. Physiological changes in ageing may alter the patient’s response not only to the anaesthetic, but also to blood and fluid loss and replacement, hypothermia, pain and tolerance of the surgical procedure and positioning. The older adult’s response to all anaesthetic agents must be carefully monitored and the postoperative recovery assessed before the patient is left without close supervision (e.g. transferred from the PARU to a surgical ward).

Many older adults experience a decrease in their ability to communicate and follow directions as a result of alterations in vision or hearing. These factors pose a special need for clear and concise communication in the OR, especially when preoperative sedation is superimposed on the existing sensory deficit. Due to a decreased ability to perceive discomfort or pressure on vulnerable areas and a loss of skin elasticity, the older adult’s skin is at risk of injury from tape, electrodes, warming and cooling blankets, and certain types of dressing. In addition, pooling of solutions used to prepare the skin in dependent areas can quickly create skin burns or abrasions.

The care and vigilance of the entire surgical team is needed in preparing and positioning the older patient. The older adult often has osteoporosis and osteoarthritis. Bad positioning, pressure and other insults to arthritic joints that may be desensitised by administration of an anaesthetic may create long-term injury and disability. Older adults are also at greater risk of perioperative hypothermia. The use of a variety of warming devices should be considered and carefully monitored if used.4

Catastrophic events in the operating room