Chapter 17 NURSING MANAGEMENT: preoperative care

1. Outline the common purposes and settings of surgery.

2. Describe the purpose and components of a preoperative nursing assessment.

3. Interpret the significance of data related to the preoperative patient’s health status and operative risk.

4. Explain the components and purpose of informed consent for surgery.

5. Outline the nursing role in the physical, psychological and educational preparation of the surgical patient.

6. Discuss the day-of-surgery preparation for the surgical patient.

7. Outline the purposes and types of preoperative medications.

8. Discuss the special considerations of preoperative preparation for the older adult surgical patient.

Surgery can be defined as the art and science of treating diseases, injuries and deformities by operation and instrumentation and may be performed for any of the following purposes:

1. diagnosis: determination of the presence and/or extent of pathology (e.g. lymph node biopsy or bronchoscopy)

2. cure: elimination or repair of pathology (e.g. removal of a ruptured appendix or benign ovarian cyst)

3. palliation: alleviation of symptoms without cure (e.g. cutting a nerve root [rhizotomy] to remove symptoms of pain or creating a colostomy to bypass an inoperable bowel obstruction)

4. prevention: examples include removal of a mole before it becomes malignant or removal of the colon in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis to prevent cancer

5. exploration: surgical examination to determine the nature or extent of a disease (e.g. laparotomy)

6. cosmetic improvement: examples include repairing a burn scar or changing breast shape.

Specific suffixes are commonly used in combination with identifying a body part or organ in naming surgical procedures (see Table 17-1).

TABLE 17-1 Suffixes describing surgical procedures

| Suffix | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| -ectomy | Excision or removal of | Appendectomy |

| -lysis | Destruction of | Electrolysis |

| -orrhaphy | Repair or suture of | Herniorrhaphy |

| -oscopy | Looking into | Endoscopy |

| -ostomy | Creation of opening into | Colostomy |

| -otomy | Cutting into or incision of | Tracheotomy |

| -plasty | Repair or reconstruction of | Mammoplasty |

Surgical settings

Surgery may be a carefully planned event (elective surgery) or may arise with unexpected urgency (emergency surgery). Both elective and emergency surgery may be performed in a variety of settings. The setting in which a surgical procedure may be safely and effectively performed is influenced by the complexity of the surgery, the potential complications and the general health status of the patient. Changes in fiscal conditions, surgical techniques and technology have led to surgical patients most often being admitted to the hospital on the day of surgery for inpatient surgery (day-of-surgery admission [DOSA]). Today the usual situation is that only those patients who are already hospitalised because of their medical conditions are in the hospital before surgery.

A large number and type of surgical procedures are being performed as day surgery (also called ambulatory surgery). Many of these surgical procedures involve the use of endoscopic techniques and are described in chapters throughout the text that discuss surgical intervention for specific medical problems. Day surgery is conducted in day surgery units, endoscopy clinics, doctors’ surgeries, freestanding surgical clinics and outpatient surgery units in hospitals. These procedures: can be performed with the use of a general, regional or local anaesthetic; usually take less than 2 hours; require less than a 3–4 hour stay in the recovery room or postanaesthetic recovery unit (PARU); and do not require an overnight hospital stay. Patients and surgeons generally prefer day surgery. Patients like the convenience, surgeons prefer the flexibility in scheduling and in the availability of operating rooms, and the cost is usually less for the patient in the private hospital setting. Day surgery generally involves fewer laboratory tests, fewer preoperative and postoperative medications, less psychological stress (especially for older adults) and less susceptibility to hospital-acquired infections.

Regardless of where the surgery is performed, the nurse is vital in preparing the patient for surgery, caring for the patient during surgery and facilitating the patient’s recovery following surgery. To perform these functions effectively, the nurse must have certain basic information. First, the nurse must have knowledge of the nature of the disorder requiring surgery and any coexisting disease processes. Second, the nurse must identify the individual patient’s response to the stress of surgery. Third, the nurse must assess the results of appropriate preoperative diagnostic tests. Finally, the nurse must consider the bodily alterations and potential risks and complications associated with the surgical procedure and any coexisting medical problems. The nurse caring for the patient preoperatively is likely to be a different nurse from the one in the operating room (OR), PARU (recovery room), intensive care unit (ICU) or surgical ward. Thus, communication and documentation of important preoperative assessment findings are essential.

The preoperative nursing measures included in this chapter are those that are applicable to the preparation of any surgical patient. Specific measures in preparation for specific surgical procedures (e.g. abdominal, thoracic or orthopaedic surgery) are covered in appropriate chapters of this text.

Patient interview

Before surgery, the patient may be seen multiple times by multiple people. To prevent the patient from having to repeat the same information over and over, the nurse should check the documentation for information before asking common questions. Regardless of the source of information, one of the most important nursing actions is the preoperative interview. The nurse who works in the surgeon’s office, the preadmission clinic, the day surgery unit or the hospital surgical ward may do the interview. The location of the interview and the time before surgery will dictate the depth and completeness of the interview. Important findings must be documented and communicated to others so that a continuum of care can be maintained.

The preoperative interview may occur in advance or on the day of surgery. The primary purposes of the patient interview are to: (1) obtain patient health information; (2) determine the patient’s expectations about surgery and anaesthesia; (3) provide and clarify information about the surgical experience; and (4) assess the patient’s emotional state and readiness for surgery. The nurse may also ensure that the patient’s consent form for surgery is signed appropriately.

In addition, the interview provides an opportunity for the patient and family to ask questions about surgery, anaesthesia and postoperative care. Often patients will ask about taking their routine medications, such as insulin or heart medications, or whether they will experience pain. The nurse who is aware of a patient’s and family’s needs and perceptions of stressors can provide or arrange for the support needed during the perioperative period.

Nursing assessment of the preoperative patient

Although nursing assessment and interventions are discussed separately here, both are done simultaneously in practice. The overall goal of the preoperative assessment is to gather data in order to identify risk factors and plan care to ensure patient safety throughout the surgical experience. Goals of the assessment are to:

1. determine the psychological status of the patient in order to reinforce coping strategies relevant to the proposed surgery

2. determine physiological factors related and unrelated to the surgical procedure that may contribute to operative risk factors

3. establish baseline data for comparison in the intraoperative and postoperative periods

4. identify prescription medications and over-the-counter medications and herbs that have been taken by the patient that may affect the surgical outcome

5. ensure that the results of all preoperative laboratory and diagnostic tests are documented and communicated to the appropriate personnel

6. identify cultural and ethnic factors that may affect the surgical experience

7. determine whether the patient has received adequate information from the surgeon to make an informed decision to have surgery and ensure that the consent form is signed.

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Psychosocial assessment

Surgery is a frightening event, even when the procedure is considered relatively minor. The psychological and physiological reactions to the surgery elicit the body’s stress response.1 This is a desirable mechanism that enables the body to cope, adapt and heal in the postoperative period. If stressors or the response to the stressors are excessive, the stress response can be magnified and recovery can be affected. Many factors influence the patient’s susceptibility to stress, including age, past experiences, current health (including mental health) and socioeconomic status. The nurse who is aware of a patient’s perceived or actual stressors can provide support and the required information during the preoperative period so that stress will not become distress.

Emotional reactions to impending surgery and hospitalisation often intensify in the older adult. Hospitalisation may represent to the patient a physical decline and loss of health, mobility and independence. The older adult may view the hospital as a place to die or as a stepping stone to long term care. The nurse can be instrumental in allaying anxieties and fears and in maintaining and restoring the self-esteem of the older adult during the surgical experience (see the section on gerontological considerations).

The nurse must use common language and avoid medical jargon. If the patient and family do not speak English, it is essential that the services of a competent translator be obtained. Hospitals now provide interpreters for common languages other than English. Words and language that are familiar to the patient should be used to increase the patient’s understanding of surgical consent and the surgical process. This also will decrease the preoperative anxiety level.

The nurse’s role in psychologically preparing the patient for surgery is to assess the patient for potential stressors that could negatively affect surgery (see Box 17-1). The nurse may not be the healthcare provider who intervenes but she or he should be able to communicate all concerns to the appropriate surgical team member. Patients with a history of mental illness may require the expertise of a mental health professional and this should be determined in the preoperative phase to improve the outcome for the patient postoperatively.2 Because the patient may be admitted directly into the preoperative area from the community or home, the nurse must be skilled in assessing vital psychological factors in a very short time. The most common psychological factors are anxiety, fear and hope.

BOX 17-1 Psychosocial assessment of the preoperative patient

Situational changes

• Determine support systems, including family, significant others, group and institutional structure, and religious and spiritual orientation.

• Define current degree of personal control, decision making and independence.

• Consider the impact of surgery and hospitalisation and the possible effects on lifestyle.

• Identify the presence of hope and anticipation of positive results.

Past experiences

• Review previous surgical experiences, hospitalisations and treatments.

• Determine responses to those experiences (positive and negative).

• Identify current perceptions of surgical procedure in relation to the above and information from others (e.g. a neighbour’s view of a personal surgical experience).

• Identify the accuracy of information the patient has received from others, including healthcare team, family, friends and the media.

Knowledge deficit

• Identify what amount and type of preoperative information this specific patient wants to know.

• Identify what this patient must know preoperatively.

• Assess the patient’s understanding of the surgical procedure, including preparation, care, interventions, preoperative activities, restrictions and expected outcomes.

Anxiety

Everyone is anxious when facing surgery because of the unknown. This is normal and is an inherent survival mechanism. However, if the anxiety level is extremely high, cognition, decision-making and coping abilities are diminished. Anxiety can arise from lack of knowledge, which may range from not knowing what to expect during the surgical experience to uncertainty about the outcome of surgery. The potential of the unknown often contributes to anxiety when the surgery is for diagnostic purposes. The patient may have unrealistic expectations of what surgery will be like or what it will accomplish. This may be a result of past experiences or the vicarious experiences provided by friends’ stories and the mass media, especially television. The nurse can decrease some anxiety for the patient by providing information about what can be expected.2 The surgeon and the surgical team (perioperative staff) should be informed if the patient requires any additional information or if anxiety seems excessive.

Patients may experience anxiety when surgical interventions are in conflict with their religious and cultural beliefs. In particular, the nurse should identify the patient’s religious and cultural beliefs about the possibility of blood transfusions.3 The need for blood replacement should have been discussed with the surgeon before admission but may not have been communicated to all the perioperative staff. The nurse also needs to be aware that patients from various ethnicities may request to have personal religious icons near them during the perioperative continuum.

Common fears

There are many reasons patients fear surgery. The most prevalent is the potential for death or permanent disability resulting from surgery. Sometimes the fear arises after hearing or reading about the risks during the informed consent process. Other fears can be pain, change in body image or results of a diagnostic procedure.

Fear of death can be extremely detrimental. If the nurse identifies a strong death fear, this concern must be communicated to the surgeon immediately. A strong fear of impending death may prompt the surgeon to postpone the surgery if the patient is convinced that it will lead to death. Attitude and emotional state influence the stress response and thus the surgical outcome.

Fear of pain and discomfort during and after surgery is universal. If the fear appears extreme, the nurse should notify the anaesthetist so that an appropriate preoperative medication can be given. The nurse can encourage the patient to talk with the anaesthetist for clarification. The patient should be reassured that medications are available to eliminate pain during surgery. Medications will be given that provide an amnesic effect so that the patient will not remember what occurs during the surgical episode. These medications can cause temporary cognitive deficits following surgery and the patient should be told preoperatively that this is common. Some patients, particularly older adults, fear that they have had a stroke during surgery if they are not aware of temporary postoperative cognition problems. The nurse should inform the patient that they should ask for medications following surgery if pain is present and that taking these medications will not contribute to an addiction.

Fear of mutilation or alteration in body image can occur whether the surgery is radical, such as amputation, or minor, such as a bunion repair. The presence of even a small scar on the body can be repulsive to some and others fear keloid development (overgrowth of a scar). The nurse must listen to and assess the patient’s concerns about this aspect of surgery with an open, non-judgemental attitude. The nurse should also ensure that aids, such as compression garments for scar minimisation, have been discussed and are available for use immediately following surgery.

Fear of anaesthesia may arise from the unknown, from tales of others’ bad experiences or from personal past experience. These concerns can result from a prior unpleasant induction of anaesthesia or from information about the hazards or complications (e.g. brain damage, paralysis). Many patients fear losing control while under the influence of anaesthesia. If these fears are identified, the nurse should inform the anaesthetist immediately so that he or she can talk further with the patient. Some patients will ask the nurse if it is safer to have general or spinal anaesthesia. The nurse should not recommend one or the other but should reassure patients that both methods are equally safe and suggest that they talk further with the anaesthetist. The patient should also be reassured that a nurse and the anaesthetist will be present at all times during surgery.

Fear of disruption of life functioning or patterns may be present in varying degrees. It can range from fear of permanent disability and loss of life to concern about not being able to play golf for a few weeks. Concerns about separation from family and about how a spouse or children are managing are common. Financial concerns may be related either to an anticipated loss of income or to the costs of surgery. If the nurse identifies any of these fears, consultation with a social worker, a spiritual or cultural advisor, a psychologist or family members may prove valuable in providing assistance to the patient.

Hope

Most psychological factors related to surgery seem to be negative but hope stands out as a positive attribute.4 Hope may be the patient’s strongest method of coping and to deny or minimise hope may negate the positive mental attitude necessary for a quick and full recovery. Some surgeries are hopefully anticipated. These can be the surgeries that repair (e.g. plastic surgery for burn scars), rebuild (e.g. total joint replacement to minimise pain and improve function) or save and extend life (e.g. repair of aneurysm or coronary artery bypass surgery). The nurse should assess and support the presence of hope and anticipation of positive results that the patient is expecting.

Past health history

The nurse should ask about diagnosed medical conditions in the patient’s past, as well as current health problems. A guideline for preoperative review of the patient’s past health history and other subjective data will assist in asking the patient about specific problems. An organised approach elicits better information than just asking whether the patient has had any medical problems. Initially, the nurse should determine if the patient understands the reason for surgery. For example, the patient scheduled for a total knee replacement may indicate that the reason for the surgery is increasing problems with pain and mobility. Past hospitalisations and the reasons for those hospitalisations should be documented. Any previous surgeries and dates of the surgeries should also be documented. Any problems with previous surgeries should be identified. For example, the patient may have experienced a bad wound infection or a reaction to an analgesic following a prior surgery.

Women should be asked about their menstrual and obstetric history. This includes obtaining the date of the patient’s last menstrual period and the number of pregnancies. If the patient states that she might be pregnant, information should be immediately given to the surgeon and the anaesthetist to avoid maternal and subsequent fetal exposure to anaesthetics during the first trimester. Questioning regarding reproductive functioning may be embarrassing for a teenager in the presence of parents or guardians. The nurse may elect to ask these questions with parents or guardians out of the room.

Asking about the patient’s family health history may identify possible inherited conditions. A family history of cardiac or endocrine disease should be recorded. For example, if a patient reports a mother or father with hypertension, sudden cardiac death, myocardial infarction or coronary artery disease, the nurse should be alerted to the possibility that the patient may also have a similar predisposition or condition. A family history of diabetes should also be investigated because of the familial predisposition to both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Tendencies towards these conditions may be exacerbated during surgery and affect physiological function during and after surgery.5 Racially and genetically inherited traits, such as Down syndrome, may contribute to the surgical outcome and need to be considered in the family history.

Information should also be obtained about the patient’s family history of adverse reactions to or problems with anaesthesia. Anaesthetists first became aware of a condition, later to be known as malignant hyperthermia, when a young man reported that 10 of his family members had died while undergoing anaesthesia. The genetic predisposition for malignant hyperthermia is now well documented, and plans of care include minimising complications associated with this condition. (See Ch 18 for further information on malignant hyperthermia.)

Medications

Current medication use, including the use of over-the-counter medications and herbal products, should be documented. In many day surgery units, patients are asked to bring their bottles of medications with them when reporting for surgery. This enables the nurse to chart the names and dosage of medications more accurately, because patients frequently cannot remember specific details if they use a large number of medications. For example, it is important to investigate whether the patient is taking the medication as ordered or has stopped taking it because of cost, side effects or the feeling that ongoing therapy is no longer needed.

Medications and herbal products may interact with anaesthetics, often increasing or decreasing potency and effectiveness, or they may be needed during surgery to maintain physiological function. It is especially important to consider the effects of medications used for heart disease, hypertension, immunosuppression, seizure control, anticoagulation and endocrine replacement. For example, tranquillisers potentiate the effect of narcotics and barbiturates, which are agents that can be used for anaesthesia. Antihypertensive medications may predispose the patient to shock from the combined effect of the medication and the vasodilator effect of some anaesthetic agents. Insulin and oral hypoglycaemic agents may require dose or agent adjustments during the perioperative period because of increased body metabolism, decreased kilojoule intake, stress and anaesthesia. Aspirin use is common in many people but it inhibits platelet aggregation and may contribute to postoperative bleeding complications. Surgeons often require that patients do not take any aspirin for at least 2 weeks before surgery, although this may vary according to the institution.6

The use of herbal therapy and dietary supplements is prevalent today. Many patients do not consider herbs and dietary supplements to be medications so they do not report them when asked what medications they are taking. Therefore, it is essential to ask specifically about the use of herbs and dietary supplements (see the Complementary & alternative therapies box). One study that examined the frequency of herbal use by surgical patients showed that of 500 patients surveyed, 51% took herbs, vitamins, dietary supplements or homeopathic medicine, ranging from one to 22 products per person.7

Complications from herbal products can include effects on blood pressure, increased sedation, cardiac effects, electrolyte alterations and inhibition of platelet aggregation. In patients taking anticoagulants or platelet aggregation inhibitors, the additional use of herbal products can produce extensive postoperative bleeding that may necessitate a return to the operating room.7 Some effects of specific herbs that can be of concern during the perioperative period are identified in the Complementary & alternative therapies box overleaf. While research is emerging about the safe use of complementary and alternative therapies in surgery, nurses need to be aware of the quality of this research.8

The nurse must also ask the patient about possible recreational substance use, abuse and addiction. The substances people are most likely to be addicted to include tobacco, alcohol, opioids, marijuana and cocaine. Questions should be asked matter-of-factly and the nurse should stress that recreational drug use may affect the type and amount of anaesthesia that will be needed. When patients become aware of the potential interactions of these drugs with anaesthetics, most will respond honestly about their drug use.9 Chronic alcohol use will place the surgical patient at risk because of lung, gastrointestinal or liver damage. When liver function is decreased, metabolism of anaesthetic agents is prolonged, nutritional status is altered and the potential for postoperative complications is increased. Alcohol withdrawal can also occur during lengthy surgery or in the postoperative period. This can be a life-threatening event, but it can be avoided with appropriate planning and management (see Ch 10).

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Herbal use of concern during the perioperative period

| Herb | Perioperative considerations |

|---|---|

| Dong quai | Increases the risk of bleeding. |

| Echinacea | Has immunostimulatory effect and should be avoided in patients who require preoperative immunosuppression; prolonged use may suppress the immune system. |

| Ephedra (ma huang) | Can interact with anaesthetics to cause dangerous elevations in blood pressure and heart rate that can lead to arrhythmias, stroke, myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest. |

| Feverfew | Increases the risk of bleeding. |

| Garlic | Inhibits platelet aggregation and increases the risk of bleeding and/or can result in an excessive response to anticoagulants. |

| Ginger | Increases the risk of bleeding. |

| Ginkgo biloba | Increases the risk of bleeding, especially in patients taking anticoagulants. |

| Ginseng | May cause rapid heart rate and increase in blood pressure; may decrease effect of certain anticholinergic drugs; may cause hypoglycaemia; inhibits platelet aggregation. |

| Goldenseal | May cause or increase high blood pressure; has anticoagulant effects. |

| Kava | May cause central nervous system depression and prolong the effects of anaesthetic agents. Possible liver toxicity, especially with high doses. |

| St John’s wort | Prolongs the effects of certain anaesthetics; has mild monoamine oxidase inhibitor effects. |

| Valerian | May prolong the effects of anaesthetic agents. |

Recommendations: As up to 70% of patients do not reveal their use of herbal medicines to their doctor, it is important that nurses be open to patients discussing any herbal medicines they may be taking. It is recommended that herbal products should be stopped at least 2–3 weeks before surgery to avoid potential complications of herb use. If this is not possible, the herbal product in its original container should be brought to the surgery site so that the anaesthetic care provider knows exactly what the patient is taking.

Source: Pribitkin EA. Herbal medicine and surgery. Semin Integr Med 2005; 3:17–23.

When assessing medications, both medication intolerance and medication allergies should be considered. Medication intolerance usually results in side effects that are uncomfortable or unpleasant for the patient but are not life-threatening. These side effects can include nausea, constipation, diarrhoea and idiosyncratic (other than expected) reactions. A true medication allergy produces hives and/or an anaphylactic reaction, causing cardiopulmonary compromise, including hypotension, tachycardia, bronchospasm and possibly pulmonary oedema. By being aware of medication intolerance and medication allergies, it will be possible to maintain patient comfort, safety and stability. For example, some anaesthetic agents contain sulfur, so the anaesthetist should be notified if a history of allergy to sulfur is given. If a medication intolerance or medication allergy is noted, it must be documented and an allergy wristband should be put on the patient on the day of surgery.

All findings of the medication history should be documented and communicated to the intraoperative and postoperative personnel. The anaesthetist will determine the appropriate schedule and dose of the patient’s routine medications before and after surgery based on the medication history; however, the nurse must ensure that all of the patient’s medications are identified, implement the alterations in medication administration and monitor the patient for potential interactions and complications.

Allergies

The nurse should inquire about non-medication allergies, including allergies to foods, chemicals, tapes and pollen. The patient with a history of any allergic responsiveness has a greater potential for demonstrating hypersensitivity reactions to medications administered during anaesthesia.

Patients should also be screened for possible latex allergies (see Ch 13). The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy10 recommends that all elective patients undergo preoperative screening using a standardised questionnaire to inquire about reactions experienced with latex gloves, balloons or condoms. Questions should be aimed at detecting individuals at risk, identifying patients from high-risk occupations and, in particular, identifying those with atopy or spina bifida. For patients with known or suspected latex allergies:

1. If the allergy is clinically relevant, consider further investigation.

2. Investigate the patient with undiagnosed episodes of anaphylaxis, as well as those with severe fruit reactions.

3. Label the patient, the patient’s notes and the bed or trolley ideally in a way to differentiate the patient from patients with other allergies.

4. Prior to admission, except in the case of an emergency, carry out admission-to-discharge planning for the patient. This must involve medical, nursing and domestic staff.

Risk factors include long-term, multiple exposures to latex products, such as those experienced by healthcare personnel and rubber industry workers. Additional risk factors include a history of hay fever, asthma and allergies to certain foods, such as avocados, kiwifruit, peanuts, bananas, chestnuts, potatoes, peaches, apricots or shellfish.

Review of systems

The last component of the patient history is the body systems review. Specific questions should be asked to confirm the presence or absence of disease. Past medical problems can alert the nurse to areas that should be examined more closely in the preoperative physical examination. If the patient is being evaluated before the day of surgery, the review of systems, combined with patient history data, will suggest the need for preoperative laboratory tests.

Cardiovascular system

The purpose of evaluating cardiovascular function is to determine the presence of pre-existing disease or existing problems (e.g. mitral valve prolapse, valve replacements) so that the patient can be efficiently monitored during the surgical and recovery periods. In the review of systems the nurse may find that there is a history of cardiac problems, including hypertension, angina, arrhythmias, congestive heart failure and/or myocardial infarction. The nurse should also inquire whether the patient has seen a cardiologist, who the cardiologist is and whether the patient is using any cardiac medications. If the patient has had a recent myocardial infarction or has a pacemaker or automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator, a cardiologist should be consulted before surgery. For patients who are on dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) following a percutaneous coronary intervention and stent insertion, a cardiologist should be consulted to assess the suitability of timing of surgery post-coronary interventions.11

The patient’s heart will be monitored continuously during surgery and, if indicated, postoperatively. The vital signs recorded preoperatively will be the baseline for the perioperative period. If pertinent, clotting and bleeding times should be recorded on the chart before surgery, as well as other laboratory reports. For example, in the patient who is on digoxin therapy, serum potassium levels will have been tested preoperatively and results should be available. If the patient has a history of hypertension, the anaesthetist will maintain adequate blood flow with medications during the surgery. If the patient has a history of congenital, rheumatic or valvular heart disease, antibiotic prophylaxis before surgery may be given to decrease the risk of bacterial endocarditis (see Ch 36). If the patient has congestive cardiac failure, the anaesthetist will ensure that an appropriate intravenous fluid administration regimen is followed to prevent pulmonary oedema.

Respiratory system

The patient should be asked about any recent or chronic upper respiratory tract infections. The presence of an upper airway infection normally results in the cancellation or postponement of elective surgery because the patient is at an increased risk of bronchospasm, laryngospasm, decreased oxygen saturation and problems with respiratory secretions. If the patient has a history of dyspnoea at rest or with exertion (e.g. breathing hard when carrying groceries), coughing (dry or productive) or haemoptysis (coughing blood), it should be brought to the attention of the anaesthetist and the perioperative team.

If a patient has a history of asthma, the nurse should inquire about the patient’s use of inhaled or oral corticosteroids and bronchodilators and the frequency and triggers of asthma attacks. The patient with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma is at high risk of postoperative pulmonary complications, including hypoxaemia and atelectasis.

The patient who smokes should be encouraged to stop at least 6 weeks preoperatively to decrease the risk of intraoperative and postoperative respiratory complications12 but may find this difficult during such a stressful time. The greater the patient’s pack-years of smoking (number of packs smoked per day multiplied by the number of years smoking), the greater the patient’s potential for pulmonary complications during or after surgery.12 Any additional conditions likely to influence or compromise respiratory function should also be noted. These include obesity; spinal, chest and airway deformities; and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA). If the patient has a history of OSA, the nurse should inquire about the use of respiratory appliances and their treatment regimens as it may be necessary to wear these appliances in the recovery room postoperatively. Depending on the patient’s history and physical examination, baseline pulmonary function tests and blood gas analyses (BGAs) may be ordered preoperatively.

Neurological system

Preoperative evaluation of neurological functioning includes assessing the patient’s ability to respond to questions, follow commands and maintain orderly thought patterns. Alterations in the patient’s hearing and vision may affect responses and the ability to follow directions, and should also be evaluated. The ability to pay attention, concentrate and respond appropriately must be documented to use as the baseline for postoperative comparison.

Cognitive function is particularly important for the patient who is expected to prepare for surgery and to complete preoperative preparation on an outpatient basis. If deficits are noted, careful assessment should determine their extent and whether the problem can be corrected before surgery. If the problem cannot be corrected, it is important to determine whether there are appropriate resources and support to assist the patient.

Assessment of cognitive function is a major assessment area in older patients. The older adult may have intact mental abilities preoperatively but the stresses of surgery, dehydration, hypothermia and medications affect older adults more than younger adults. These factors may contribute to the development of postoperative delirium, a condition that may be falsely labelled as senility or dementia. Thus, preoperative findings are extremely important for postoperative comparison.

In the review of the nervous system it is also important to inquire about any presence of cerebrovascular accidents (strokes), transient ischaemic attacks or spinal cord injury. In some cases, patients may require examination of the carotid arteries prior to surgery to assess the risk of stroke. The nurse should inquire about diseases of the nervous system, such as cerebral palsy, myasthenia gravis, Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis, and medications used for the conditions.

Urinary system

The preoperative patient should be asked about a history of renal or urinary diseases, such as glomerulonephritis, chronic renal insufficiency or repeated urinary tract infections. The present status should be noted and documented. Renal dysfunction is associated with a number of alterations, including fluid and electrolyte imbalances, coagulopathies, increased risk of infection and impaired wound healing.13 It should be noted if the patient has any treatment for chronic renal failure, such as renal dialysis. Another important consideration is the recognition that many medications are metabolised and excreted by the kidneys. A decrease in renal function may contribute to an altered response to medications and unpredictable medication elimination. Renal function tests, such as serum creatinine and urea, are commonly ordered preoperatively, and results should be recorded on the patient’s chart before surgery. It is common that patients with renal impairment may require intravenous hydration prior to surgery to avoid dehydration induced by fasting.14

If the patient has any problems voiding, it should be noted. Male patients may have physical alterations, such as an enlarged prostate, which would hinder the insertion of a urinary catheter during surgery. An enlarged prostate may also impair voiding in the postoperative period. This information should be documented and shared with the perioperative team. Incontinence problems should also be documented, as catheters may need to be inserted prophylactically to avoid contamination of the operative field.

Hepatic system

The liver is involved in glucose homeostasis, fat metabolism, protein synthesis, medication and hormone metabolism, and bilirubin formation and excretion. The liver detoxifies many anaesthetics and adjunctive medications. The patient with hepatic dysfunction may have problems with glucose control, clotting abnormalities and an impaired response to medications, all of which may increase perioperative risk. The nurse should consider the presence of liver disease if there is a history of jaundice, hepatitis or alcohol abuse.

Integumentary system

The nurse should ask about a history of skin problems, especially in the older adult. A history of skin rashes, boils, ulcers or other dermatological conditions should be noted. A history of pressure ulcers may require extra padding during surgery, and skin problems may affect postoperative healing. Allergies and sensitivities to dressings or tapes should be noted and these products should be avoided. Skin should be assessed for cleanliness and excessive hair in the operative area to reduce the incident of surgical site infection. Appropriate skin cleansing and hair removal treatments may be required.15

Musculoskeletal system

Mobility problems should also be noted. If the patient has arthritis, all affected joints should be identified. Mobility restrictions may influence intraoperative and postoperative positioning and postoperative ambulation. Spinal anaesthesia may be difficult if patients cannot flex their lumbar spine adequately to allow easy needle insertion. If the neck is affected, intubation and airway management may be difficult. Any mobility aids, such as a cane, walker or crutches, should be brought with the patient on the day of surgery.

Endocrine system

Diabetes mellitus is a risk factor for both anaesthesia and surgery. The diabetic patient is at risk of the development of hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia, ketosis, cardiovascular alterations, delayed wound healing and infection. Preoperative blood sugar level (BSL) tests should be done to determine baseline levels. It is important to clarify with the patient’s surgeon or anaesthetist whether the patient should take the usual dose of insulin on the day of surgery. Some practitioners prefer that the patient take only half of the usual dose; others ask that the patient take either the usual dose or take no insulin at all. Regardless of the preoperative insulin orders, the patient’s BSL will be determined periodically and managed, if necessary, with regular (short-acting, rapid-onset) insulin.

It should also be determined whether the patient has a history of thyroid dysfunction. Either hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism can place the patient at surgical risk because of alterations in metabolic rate. If the patient takes a thyroid replacement medication, the nurse should check with the anaesthetist about administration of the medication on the day of surgery. If the patient has a history of thyroid dysfunction, laboratory tests may be ordered to determine current levels of thyroid function.

Immune system

If the patient has a history of a compromised immune system or takes immunosuppressive medications, it must be documented. Impairment of the immune system can lead to delayed wound healing and increased risk of postoperative infections. If the patient has an acute infection (e.g. active skin rash, acute sinusitis, influenza), elective surgery is frequently cancelled. Patients with active chronic infections, such as hepatitis, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and tuberculosis, may still have surgery. When preparing the patient for surgery, it should be remembered that infection control precautions must be taken with every patient. (Infection control guidelines are discussed in Ch 12.)

Fluid and electrolyte status

The patient should be questioned about the presence of conditions that increase the risk of fluid and electrolyte imbalances, such as vomiting, diarrhoea or difficulty swallowing. Medications that the patient takes that alter fluid and electrolyte status, such as diuretics, should also be identified. Serum electrolyte levels are often evaluated before surgery. Some patients may have restricted fluids for some time before surgery and, if the surgery is delayed, they could develop dehydration. A patient with or at risk of dehydration may require additional fluids and electrolytes before or during surgery. Although a preoperative fluid balance history should be completed for all patients, it is especially critical for the older adult because the reduced adaptive capacity leaves a narrow margin of safety between overhydration and underhydration.

Nutritional status

Nutritional deficits include overnutrition and undernutrition, both of which require considerable time to correct. However, knowing that a patient is at either end of the nutritional scale can help the team provide safer care. For example, with the very obese patient, timely notification can allow the perioperative nurse time to obtain a large operating table on which surgery can be performed. Longer instruments can also be prepared, especially for abdominal surgery. These interventions can only happen if the information is communicated at least a day before surgery.

Obesity stresses both the cardiac and the pulmonary systems and makes access to the surgical site and anaesthesia administration more difficult. Some inhalational anaesthetic agents are absorbed and stored by adipose tissue, which is less vascular than other types of tissue. The obese patient may be slower to recover from anaesthesia because some inhalation anaesthetic agents are absorbed and stored in adipose tissue, and therefore may leave the body more slowly.16 Obesity predisposes the patient to wound dehiscence, wound infection and incisional herniation postoperatively due to increased tension on the wound.17

Nutritional deficiencies of protein and vitamins A, B and C complex are particularly significant because these substances are essential for wound healing.18 Supplemental intravenous and oral nutrients can be administered during the perioperative period to promote adequate healing ability if the patient is malnourished. The older adult is often at risk of malnutrition and fluid volume deficits.18 If the patient is very thin, the perioperative team should be notified in order to provide more padding than usual (pressure points on all patients are protected routinely) on the operating table. This is necessary to prevent pressure ulcers, especially during a lengthy procedure. Nutritional deficiencies impair the ability to recover from surgery. It is important to remember that the obese patient can also be protein and vitamin deficient. If the nutritional problem is severe, the surgery may be postponed until the patient loses or gains weight and nutritional deficiencies are corrected.

Dietary habits may affect postoperative recovery and should be identified. For example, patients who consume large quantities of coffee or soft drinks containing high caffeine levels should be identified. In many cases, the withholding of caffeinated beverages preoperatively, as well as for a considerable length of time postoperatively, can lead to severe withdrawal headaches.19 Caffeine withdrawal headaches could be confused with spinal headaches if the preoperative data are not documented. Caffeinated beverages given postoperatively to the patient, when possible, will prevent caffeine withdrawal headaches.

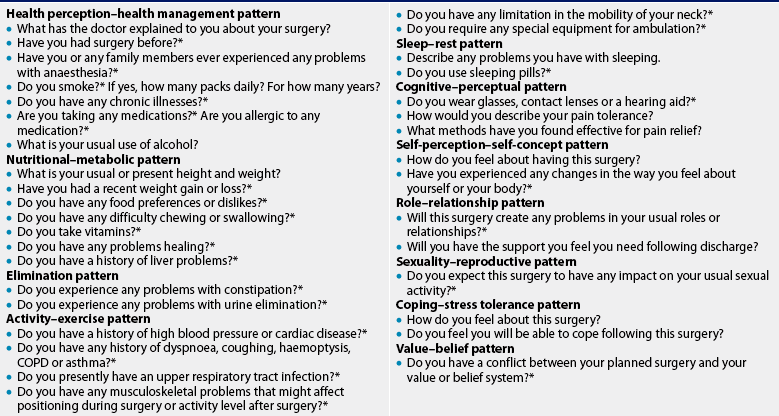

Functional health patterns

The review of each functional health pattern of the patient provides valuable subjective data about the patient’s physical and psychological status, as well as cultural values and beliefs related to his or her healthcare. Questions to ask a preoperative patient are listed in Table 17-2.

OBJECTIVE DATA

Physical examination

All patients admitted to the operating room have a documented physical examination (PE) in the chart. This examination may be done in advance of surgery or on the day of surgery. The PE may be performed by any of a number of qualified people, including nurses, surgeons, surgical residents and anaesthetists.

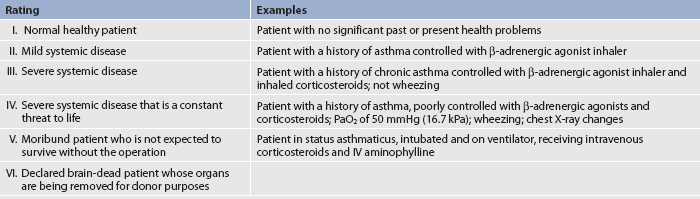

Findings from the patient’s history and PE will enable the anaesthetist to assign the patient a physical status rating for anaesthesia administration (see Table 17-3). This rating is an indicator of the patient’s perioperative risk and overall outcome.

TABLE 17-3 Preoperative rating of patient’s physical status

Source: Adapted from Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. PS9: Guidelines on sedation and/or analgesia for diagnostic and interventional medical or surgical procedures. Available at www.anzca.edu.au/resources/professional-documents/pdf/PS9-2010.pdf, accessed 29 December 2010.

Many physiological stressors may put the patient at risk of surgical complications, whether the surgery is an elective or an emergency procedure. A physiological assessment of the preoperative patient is presented in Table 17-4. If the PE is done immediately before surgery, it will be focused because of the impending procedures that need to be completed before surgery. The nurse should review the documentation already present on the patient’s chart, including the review of systems and the doctor’s PE report, to better proceed with the examination in a relevant way. All findings must be documented, with any relevant findings immediately communicated to members of the perioperative team.

TABLE 17-4 Physiological assessment of the preoperative patient*

• Identify acute or chronic problems; focus on the presence of angina, hypertension, congestive heart failure and recent history of myocardial infarction.

• Auscultate and palpate baseline pulses: apical, radial and pedal for rate and characteristics (compare one side with the other).

• Inspect and palpate for presence of oedema (including dependent areas), noting location and severity.

• Inspect and palpate neck veins for distension.

• Take baseline blood pressure.

• Identify any drug or herbal product that may affect coagulation (e.g. aspirin, ginkgo, ginger).

• Review laboratory and diagnostic tests for cardiovascular function.

• Identify acute or chronic problems; note the presence of infection

• Assess history of smoking, including the time interval since the last cigarette and the number of pack-years. (Remember that although smoking should be discouraged preoperatively, it may be difficult for patients to stop during this time of anxiety.)

• Auscultate lungs for normal and adventitious breath sounds.

• Determine baseline respiratory rate and rhythm, and regularity of pattern.

• Observe for cough, dyspnoea and use of accessory muscles of respiration.

• Determine orientation to time, place and person.

• Identify presence of confusion, disorderly thinking or inability to follow commands.

• Identify past history of strokes, transient ischaemic attacks or diseases of the central nervous system, such as Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

• Identify any pre-existing disease.

• Determine ability of the patient to void. Prostate enlargement may affect catheterisation during surgery and ability to void postoperatively.

• If necessary, note colour, amount and characteristics of urine.

• Review laboratory and diagnostic tests for renal function.

• Inspect skin colour and sclera of eyes for any signs of jaundice.

• Review past history of substance abuse, especially alcohol and IV drug use.

• Review laboratory and diagnostic tests for liver function.

• Assess mucous membranes for dryness and intactness.

• Determine skin status; note drying, bruising or breaks in integrity of surface.

• Inspect skin for rashes, boils or infection, especially around the planned surgical site.

• Assess skin moisture and temperature.

• Inspect the mucous membranes and skin turgor for presence of dehydration.

• Examine skin/bone pressure points.

• Assess for presence of any pressure ulcers.

• Assess for limitations in joint range of motion and muscle weakness.

• Assess mobility, gait and balance.

• Assess for presence of joint pain.

• Determine food and fluid intake patterns and any recent weight loss.

• Weigh patient and measure height.

• Assess for the presence of dentures and bridges (loose dentures or teeth may be dislodged during intubation).

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Iv, intravenous.

*See related body system chapters for more specific assessments and related laboratory studies.

Laboratory and diagnostic testing

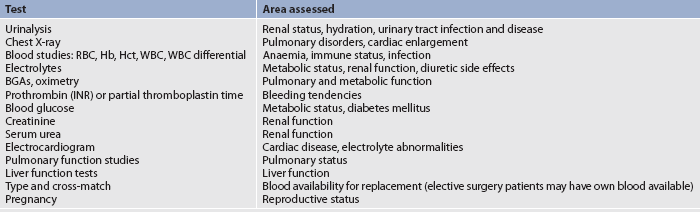

The nurse should obtain and evaluate the results of laboratory and diagnostic tests ordered preoperatively. For example, if the patient is taking an anticoagulant (including aspirin), a coagulation profile may be done; patients on diuretic therapy may need to have their potassium level tested; a patient taking medications for arrhythmias will probably have a preoperative electrocardiogram (ECG). Blood glucose monitoring should be done for patients with diabetes. The nurse can do a BSL if a low or high glucose level is suspected during the preoperative assessment where there are institutional policies in place to do so. Findings may require dose or agent adjustments during the perioperative period because of increased body metabolism, decreased kilojoule intake, stress and anaesthesia. Regulation of the stability of the blood glucose levels during surgery will promote a more positive outcome. Commonly ordered preoperative laboratory tests are listed in Table 17-5.

TABLE 17-5 Common preoperative laboratory tests

BGAs, blood gas analyses; Hb, haemoglobin; Hct, haematocrit; INR, international normalised ratio; RBC, red blood cells; WBC, white blood cells.

Ideally, preoperative laboratory tests should be ordered on the basis of the individual patient history and physical examination. However, many facilities have a written protocol or standards for preoperative laboratory tests, which may or may not include all the identified need areas. In addition, doctors’ surgeries and preadmission clinics may do the preoperative tests days before surgery and they may not be physically located near the surgical institution. Thus, the nurse must ensure that all laboratory and diagnostic reports such as CT scans and X-rays have arrived at the place of surgery at the right time and are recorded on the patient’s chart. Lack of these reports may result in a delay to or cancellation of the surgery.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: THE PREOPERATIVE PATIENT

NURSING MANAGEMENT: THE PREOPERATIVE PATIENT

Preoperative nursing interventions are derived from the nursing assessment and must reflect each individual patient’s specific needs. Physical preparations will be determined by the pending surgery and the routines of the surgery setting. Psychological preparations should be tailored to each patient’s needs. Preoperative teaching may be minimal or extensive. General information for surgery should be given.

Preoperative teaching

Preoperative teaching

The patient has a right to know what to expect and how to participate effectively during the surgical experience. Preoperative teaching increases patient satisfaction. It can reduce postoperative vomiting and pain, and preoperative fear, anxiety and stress.1 It can also decrease complications, the duration of hospitalisation and the recovery time following discharge. However, the time available for effective teaching can be minimal.

In most surgical settings, patients often arrive only a short time before surgery is scheduled, even when the surgery is performed in a hospital and they will be hospitalised postoperatively. After day surgery, patients usually go home several hours after recovery. This means that patient teaching must be efficient and address needs of the highest priority—that is, what does the patient want to know, or need to know, right now, versus what would be nice to know for the whole surgical experience. If there is no time to allow for repetition, reinforcement and verification of the patient’s understanding, the family should be included to provide these actions. Written materials should also be provided for patients and families to use for review and reinforcement.

In preparing the patient for surgery, the nurse must strike a balance between telling so little that the patient is unprepared and explaining so much that the patient is overwhelmed. The nurse who observes carefully and listens sensitively to the patient can usually determine how much information is enough, remembering that anxiety and fear may decrease learning ability.1 The nurse must also assess what the patient wants to know right away and give priority to these concerns.

Generally, preoperative teaching relates to three types of information: sensory, process and procedural.20 Different patients, with varying cultures, backgrounds and experience, may want different types of information. With sensory information, patients want to know what they will see, hear, smell and feel during the surgery. For example, the nurse may tell them that the OR will be cold but that they can ask the OR nurse for a warm blanket; the lights in the OR are very bright; or there will be a lot of sounds that are unfamiliar and there may be specific smells present. Patients wanting process information may not want specific details but desire to know the general flow of what is going to happen. For example, they can be told that they will be in a holding area and the nurse and anaesthetist will visit them. They will go to the OR; then, when they wake up, they will be in the PARU; and as soon as they are awake, their family can come in to visit them. With procedural information, desired details are more specific; for example, an intravenous line will be started while the patient is in the holding area, and in the OR the patient will be asked to move onto a narrow bed.

Preoperative patient teaching must be communicated to the postoperative care nurses so that learning can be evaluated from past teaching and duplication of teaching can be prevented. Because no nurse has unlimited time for teaching, the team approach is usually used. Patient teaching may commence in the preadmission clinic or in the surgical ward preoperatively, the perioperative nurse continues it and the surgical ward nurse reinforces and supplements it. It may be important that community nurses also be aware if the patient has continuing learning needs because they may be the ones who visit the patient at home, in the community or in extended care facilities after surgery.

All teaching should be documented in the patient’s medical record. A patient and family teaching guide for preoperative preparation is presented in Table 17-6. Additional information related to patient teaching may be found in Chapter 4.

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

• Holding area is often noisy.

• Drugs and cleaning solutions may be smelled.

• OR can be cold; warm blankets are available.

• Talking may be heard in the OR but will be distorted because of masks. Questions should be asked if something is not understood.

• Lights in the OR can be very bright.

• Machines (ticking and pinging noises) may be heard when awake.

Their purpose is to monitor and ensure safety.

• What to bring and what type of clothing to wear to the day surgery centre.

• Any changes in time of surgery.

• Fluid and food restrictions.

• Physical preparation required (e.g. bowel or skin preparation).

• Purpose of frequent vital signs assessment.

• Pain control and other comfort measures.

• Why turning, coughing and deep breathing postoperatively are important; practice sessions need to be done preoperatively.

• Insertion of intravenous lines.

• Procedure for anaesthesia administration.

Information about general flow of surgery

• Preoperative holding area, OR and recovery area.

• Families can usually stay in holding area until surgery.

• Families may be able to enter recovery area as soon as patient is awake.

• Identification of any technology that may be present on awakening, such as monitors and central lines.

Where families can wait during surgery

• Patient and family members need to be encouraged to verbalise concerns.

OR, operating room.

General surgery information

General surgery information

Preoperative teaching includes essential information that the patient desires and needs to know during the surgical experience. This information must be tailored to each individual patient and reflect the specific surgery. The nurse should determine what would best serve this patient rather than routinely giving information that may or may not be relevant. All patients should receive instruction about deep breathing, coughing and moving postoperatively. This is essential because patients may not want to do these activities postoperatively unless they are taught the rationale for them and practise them preoperatively. Patients and families should be told if there will be tubes, drains, monitoring devices or special equipment after surgery, and that these devices enable the nurse to care for the patient safely.

Examples of individualised teaching may include how to use incentive spirometers or postoperative patient-controlled analgesia pumps. The patient could also receive surgery-specific information; for example, a patient with a total joint replacement having an immobiliser, a patient getting an epidural catheter for postoperative pain control or the patient requiring extensive surgery being told about waking up in the ICU.

Day surgery information

Day surgery information

The day surgery patient or the patient admitted to the hospital on the day of surgery will need to receive information before admission. The teaching is generally done in the surgeon’s office or preadmission surgical clinic and reinforced on the day of surgery. Some day surgical units have the staff telephone the patient the evening before surgery to answer last-minute questions and to reinforce teaching. Each surgical centre has policies and procedures that direct and enable this communication in a timely manner. Nurses should identify this process for the institution in which they will be working.

Information for the patient includes the time to arrive at the surgery centre and the time of surgery. Arrival time is usually 1–2 hours before the scheduled time of surgery to allow for the completion of the preoperative assessment and paperwork preparation. Information can also include the day-of-surgery events, such as patient registration, parking, what to wear, what to bring and the need to have a responsible adult present for transportation home after surgery.

Preoperative preadmission information can include the need for a preoperative shower, an enema, and food and fluid restrictions. Historically, patients having elective surgery were usually instructed to have nil by mouth (NBM) starting at midnight on the night before surgery. However, professional anaesthetic organisations around the world have revised this practice in the light of evidence demonstrating the safety and benefits of a shortened preoperative fast for healthy surgical patients.21,22 The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists has developed recommendations for fasting for patients selected for day care surgery (see Box 17-2).23 Providing the patient with the rationale for adhering to NBM orders can significantly increase the patient’s perception of their importance. Protocols may vary if the patient is having local anaesthesia or the surgery is scheduled for late in the day. The NBM protocol of each surgical facility should be followed because varying NBM protocols exist. Restriction of fluids and food is designed to minimise the potential risk of aspiration and to decrease the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting. The patient who has not followed this instruction may have surgery delayed or cancelled, so it is vital that the surgical patient understands and adheres to these restrictions.

BOX 17-2 Preoperative fasting recommendations for patients selected for day care surgery

The patient should be provided with information in an understandable written format, which must include instructions for fasting according to the following guidelines unless otherwise specifically prescribed by the anaesthetist or where other institution guidelines apply:

• Limited solid food may be taken up to 6 hours prior to anaesthesia.

• Unsweetened clear fluids totalling not more than 200 mL per hour in adults may be taken up to 2 hours prior to anaesthesia. Body fluid depletion due to excessive fasting should be avoided.

• Only mediations or water ordered by the anaesthetist should be taken less than 3 hours prior to anaesthesia.

• An H2-receptor antagonist should be considered for patients with an increased risk of gastric regurgitation.

Source: Adapted from Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. PS15: Recommendations for the perioperative care of patients selected for day care surgery. Available at www.anzca.edu.au/resources/professional-documents/ps15.html, accessed 29 December 2010.

Legal preparation for surgery

Legal preparation for surgery

Legal preparation for surgery consists of checking that all required forms have been correctly signed and are present on the chart, and that the patient and family understand what is going to happen. The most important of these forms is the signed consent form for the surgical procedure and blood transfusion. Other forms may include those that have been completed for advance directives, living wills and power of attorney (see Ch 9).

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Best clinical practice

• Prolonged preoperative fasting is a time-honoured tradition. The typical order of NBM after midnight (or no food or liquid after 12 am (‘midnight’) on the day of surgery) has been challenged in recent years.

• Pulmonary aspiration is a rare complication of modern anaesthesia.

• Based on extensive evidence, and in line with many other professional anaesthetist organisations worldwide, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) revised its practice guidelines for preoperative fasting in healthy patients undergoing elective procedures.

• The guidelines allow clear liquids up to 2 hours before elective surgery, and a light breakfast (e.g. tea and toast) up to 6 hours before anaesthesia.

Implications for nursing practice

More collaboration between nurses and surgeons is needed to ensure that fasting instructions are given according to ANZCA guidelines and that patients understand them.

Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. PS15: Recommendations for the perioperative care of patients selected for day care surgery. Available at www.anzca.edu.au/resources/professional-documents/ps15.html. accessed 29 December 2010.

Brady M, Kinn S, Stuart P, Ness V. Preoperative fasting for adults to prevent perioperative complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2003. CD004423.

Consent for surgery

Consent for surgery

Before non-emergency surgery can be performed legally, the patient must sign a voluntary and informed consent form in the presence of a witness. Informed consent is an active, shared decision-making process between the provider and the recipient of care. This process protects the patient, the surgeon, and the hospital and its employees. Every surgical facility has its own required informed consent form, and the nurse should become familiar with both the form and the process of obtaining consent in that institution.

Three conditions must be met for consent to be valid. First, there must be adequate disclosure of the diagnosis; nature and purpose of the proposed treatment; risks and consequences of the proposed treatment; probability of a successful outcome; availability, benefits and risks of alternative treatments; and prognosis if treatment is not instituted. Second, the patient must demonstrate a clear understanding and comprehension of the information that is provided. Because preoperative medications may cloud a patient’s comprehension, the operative consent must be signed before any preoperative medication is given. Third, the recipient of care must give consent voluntarily. The patient must not be persuaded or coerced in any way to undergo the procedure.

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Situation

The nurse discusses a patient’s impending surgery in the preoperative holding area. It becomes obvious that this competent adult patient was not fully informed of the alternatives to this surgery. She has signed the consent form but clearly was not fully informed about her treatment options.

Important points for consideration

• Informed consent requires that patients have complete information about the proposed treatment and its possible consequences, as well as alternative treatments and possible consequences.

• Risks and benefits of each treatment option must also be explained in order for patients to weigh up treatment options.

• An opportunity to have questions answered about the various treatment options and their possible outcomes is an important element of informed consent.

• Paternalism results when healthcare providers do not provide complete information for patients to make fully informed decisions or when they decide what is best for patients.

The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists recommend:

1. Consent must be given voluntarily without coercion.

2. Consent must be given by a person capable of doing so.

4. Consent should include disclosure of risks.24

The treating doctor is ultimately responsible for obtaining the consent; however, the nurse may be responsible for witnessing the patient’s signature on the consent form. At this time the nurse can be a patient advocate, verifying that the patient (or family member) understands the consent form and its implications and that consent for surgery is truly voluntary. The nurse will contact the surgeon and explain the need for additional information if the patient is unclear about operative plans. The patient needs to be informed that permission may be withdrawn at any time, including after the consent form has been signed.

If the patient is a minor, is unconscious or is mentally incompetent to sign the consent form, the written permission may be given by a legally appointed representative or responsible family member. Local hospital policies should be checked for further clarification.

A true medical emergency may override the need to obtain consent. When immediate medical treatment is needed to preserve life or to prevent serious impairment to life and the individual patient is incapable of giving consent, the next of kin may give consent. If reaching the next of kin is not possible, the treating doctor may institute treatment without written consent. A note is written in the chart documenting the medical necessity of the procedure.

Procedures for obtaining consent vary among states and institutions. The nurse should be aware of the state’s Nurses’ Act and the institutional or agency policies that apply to an individual situation.

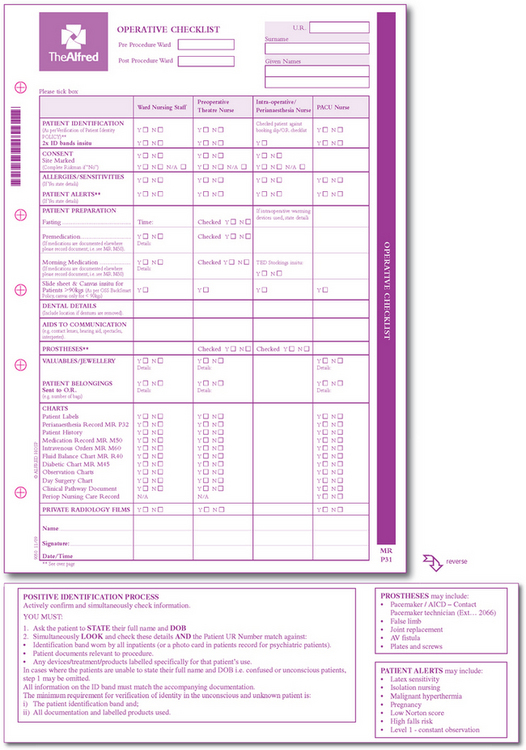

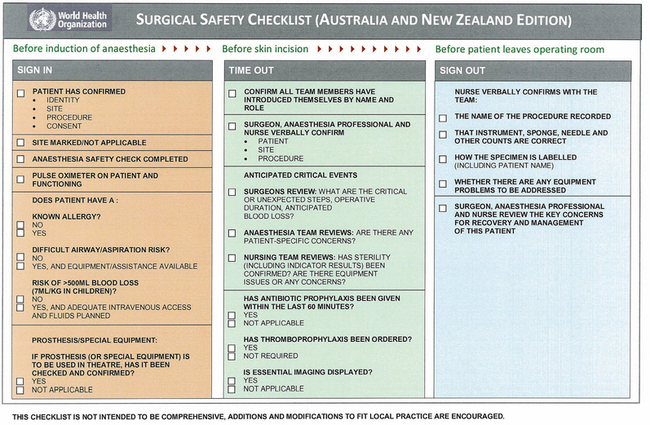

In August 2009, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists welcomed the introduction of the Surgical Safety Checklist, developed by the World Health Organization, as an important clinical tool for Australian and New Zealand hospitals.25 This tool was designed to improve outcomes for patients undergoing surgery by decreasing the potential for errors, such as an incorrect surgery site. It is recommended that local preoperative checklists incorporate the principles of this document. An example would be the identification and marking of the correct surgical site (see Figure 17-1).

Figure 17-1 Surgical safety checklist.

Source: Australia New Zealand College of Anaesthetics. www.anzca.edu.au.

Day-of-surgery preparation

Day-of-surgery preparation

Nursing role

Nursing role

Day-of-surgery preparation will vary a great deal depending on whether the patient is an inpatient or an outpatient. The nursing responsibility immediately before surgery includes final preoperative teaching, assessment and communication of pertinent findings, ensuring that all preoperative preparation orders have been completed, ensuring that records and reports are present and complete, and ensuring that these records and reports accompany the patient to the OR. It is especially important to verify the presence of a signed operative consent, laboratory data, a history and physical examination report, a record of any consultations, baseline vital signs and nurses’ notes complete to that point.

If the patient is an inpatient, it will be the responsibility of the hospital nurse to ensure that the patient is ready and appropriately prepared for surgery. If the patient is an outpatient, the patient or family member will share the responsibility for preoperative preparation.

Most institutions require that a patient wear a hospital gown with no underclothes. Some surgery centres allow the patient to wear underwear, depending on the surgical procedure to be performed. The patient should wear no make-up because observation of skin colour will be important. While many institutions recommend that nail polish should be removed to gain more accurate pulse oximetry readings, there is little evidence to support this.26 An identification band is put on the patient along with, if applicable, an allergy band. All the patient’s valuables are returned to a family member or locked up according to institutional protocol. If the patient prefers not to remove a wedding ring, the ring can be taped securely to the finger to prevent loss. All prostheses, including dentures, contact lenses and glasses, are generally removed to prevent loss or damage to them. Glasses and hearing aids may be left in place until the time of surgery to allow the patient to follow instructions better, but they must be returned to the patient as soon as possible following surgery.

The patient must void shortly before surgery as this prevents involuntary elimination under anaesthesia and reduces the possibility of urinary retention during early postoperative recovery.27 This should be done before the administration of any preoperative medication: many preoperative medications can interfere with balance and could result in a fall when the patient is in the bathroom.

The nurse should determine that all preoperative preparations have been completed and that the signed consent for surgery is present before giving any preoperative medications. The use of a preoperative checklist (see Fig 17-2) ensures that no detail has been omitted.

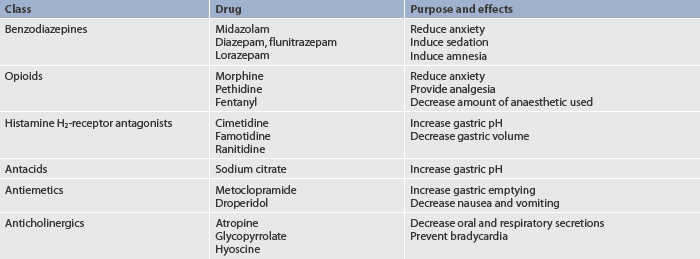

Preoperative medications

Preoperative medications

Preoperative medications are used for a variety of reasons (see Box 17-3). A patient may receive a single medication or a combination of medications (see Table 17-7). Benzodiazepines and barbiturates are used for their sedative and amnesic properties. Narcotics may be given to decrease intraoperative anaesthetic requirements and to decrease pain. Antiemetics may be given to decrease nausea and vomiting. Anticholinergics are given to reduce secretions.

Other medications that may be administered preoperatively include antibiotics, eye drops and routine prescription medications. Antibiotics may be administered throughout the perioperative period for a patient with a history of congenital or valvular heart disease to prevent the development of infective endocarditis. They may also be ordered for the patient undergoing surgery where wound contamination is either a potential risk (e.g. gastrointestinal surgery) or where wound infection could have serious postoperative consequences (e.g. cardiac and joint replacement surgery). Antibiotics are most commonly administered intravenously and may be started either preoperatively or in the OR.

Eye drops are commonly ordered and administered preoperatively for the patient undergoing cataract and other eye surgery. Many times the patient will require multiple sets of eye drops administered at 5-minute intervals. It is important to administer these medications as ordered and on time to prepare the eye adequately for surgery.

A standard protocol for what routine medications are always given on the day of surgery and those that are never given on the day of surgery does not exist. In order to facilitate patient teaching and eliminate confusion about the medications, it is very important to check written preoperative orders carefully and to clarify which medications should and should not be taken on the day of surgery. If there is any question, the nurse should clarify the orders with the anaesthetist. Most patients will be advised to take routine cardiac, antihypertensive and asthma medications on the day of surgery. In the case of insulin it is important to clarify with the anaesthetist the time and amount of the last dose before surgery.

Premedications may be administered orally (O), intravenously (IV), subcutaneously (SC) or intramuscularly (IM). Oral medications should be given 60–90 minutes before the patient goes to the OR. Because patients are fluid restricted before surgery, the patient should swallow these medications with a minimal amount of water. IM and SC injections should be given 30–60 minutes before arrival at the OR (minimum 20 minutes) (see Box 17-3). IM medications are usually administered to the patient after arrival in the preoperative holding area or the OR. Medication administration should be charted immediately.28 The patient should be told the effects of the medications, such as relaxation, drowsiness and dryness of the mouth, and be advised not to ambulate without assistance following administration to reduce the risk of falls. Some patients may require oxygen therapy prior to an anaesthetic for major surgery, such as cardiac surgery, as the premedication may inhibit their ability to maintain adequate oxygenation.

Transportation to the operating room

Transportation to the operating room

If the patient is an inpatient, the OR staff may send transport personnel to the patient’s room with a trolley to transport the patient to surgery. The nurse assists the patient in transferring from the hospital bed to the OR trolley, and the side rails of the trolley are raised and secured. In some hospitals, patients are transferred to the OR on their hospital bed and then transferred to the OR trolley. The nurse should ensure that the completed chart goes with the patient, as well as any ordered preoperative equipment, such as oxygen therapy, antiembolism devices or the patient’s inhaler. In many institutions the family may accompany the patient to the holding area.

If the patient is an outpatient, the patient may be transported to the OR on a bed or by trolley or wheelchair or, in the absence of premedication, may even walk accompanied to the OR. In all cases it is important for the nurse to ensure patient safety during transport. The nurse responsible for the transfer should document the method of transportation and who transported the patient.

The family should be instructed where to wait for the patient during surgery. Some hospitals provide pagers to waiting family members so that they may eat or undertake other activities during the surgery.