Chapter 19 NURSING MANAGEMENT: postoperative care

1. Outline the nursing responsibilities in caring for patients admitted to the postanaesthetic recovery unit (PARU).

2. Identify components of the physical assessment of the postanaesthesia patient on admission to the PARU.

3. Explain the aetiology of potential postoperative problems that may occur in the PARU, including nursing assessment and management.

4. Discuss the criteria for the transfer of the patient from the PARU.

5. Outline the initial nursing assessment and management of the postanaesthesia patient after transfer from the PARU to the general surgical unit.

6. Explain the aetiology of potential postoperative problems, including the nursing assessment and management.

7. Discuss the information provided to the patient prior to discharge from the surgical unit.

The postoperative period begins immediately after surgery and continues until the patient is discharged from medical care. This chapter focuses on the postoperative nursing management of the surgical patient. The problems and nursing care related to specific surgical procedures are discussed in separate chapters.

POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT IN THE POSTANAESTHESIA RECOVERY UNIT

The patient’s postoperative recovery period is supervised by a postanaesthesia recovery (PAR) nurse, a specialist working in a postanaesthesia recovery unit (PARU) and following the Australian College of Operating Room Nurses (ACORN) standards.1 The PARU is located adjacent to the operating room (OR) to minimise transportation of patients immediately after surgery and to provide ready access to the anaesthetist and surgical team. The primary purpose of the PARU is to conduct an immediate assessment of the postsurgical patient, including stabilisation and prevention of complications that may occur as a result of the anaesthesia or the operative procedure. The design of the PARU may include two patient-designated areas referred to as Stage I and Stage II recovery areas. While these areas are not a common feature within all PARUs in Australia, units that have Stage I and Stage II areas are able to segregate patients according to the method of anaesthesia administered intraoperatively. Postoperative patients who have undergone general anaesthesia are admitted to the Stage I area and those who have had a local or regional anaesthetic or conscious sedation are admitted to the Stage II area. Those patients considered day surgery patients are discharged from the hospital directly from the Stage II area. Units without a two-stage recovery area facilitate the recovery of all postoperative patients within the delegated area, irrespective of the anaesthetic method administered.

Fast-tracking

Fast-tracking may be implemented in certain units in which patients are admitted to either Stage I or Stage II recovery areas. Patient allocation to either area would depend on the type of anaesthesia and surgical procedure, including the time of discharge from the unit that would be anticipated. Bypass of PARU Stage I results in direct admission of patients from the operating room to the Stage II recovery area. This type of bypass is appropriate only for day surgery patients who are discharged from the hospital directly from the unit. Inpatients are required to be admitted to the Stage I recovery area prior to being transferred to the inpatient surgical unit.

Rapid PARU progression is fast-tracking of both inpatient and day surgery patients owing to the patients recovering rapidly postoperatively and meeting the criteria required for discharge. Patients are admitted to the Stage I unit during emergence from a general anaesthetic but are transferred to the Stage II area, the inpatient unit and/or home as soon as the discharge criteria are met. Technological advances in monitoring equipment and the use of shorter-acting anaesthetic agents have been the impetus for instituting these changes. Fast-tracking has been shown to result in reduced patient stay in the PARU, cost savings and increased patient satisfaction.2 Studies involving day surgery patients have shown that implementing fast-tracking has not resulted in compromising patient safety.2

Postanaesthesia recovery unit admission

In 2002, ACORN published standards that provide guidelines for the admission and ongoing management of patients while in the PARU. These standards were updated in 2010–2011 and include guidelines for providing quality nursing care in the PARU.3 The ACORN standards are the recommended guidelines for the PAR nurse to ensure a positive outcome for patients undergoing a surgical procedure. ACORN standard S19, statement 5, provides guidelines recommending nursing staff numbers and the appropriate skills required by nursing staff to ensure that the needs of the patient are met during the recovery phase of the surgical experience. These guidelines include the following recommendations for the PARU:

• In the Stage I and Stage II areas, a minimum of two nurses is required if a patient is present, one of whom must be an experienced PAR nurse.

• A minimum requirement of a 1:1 nurse-to-patient ratio is recommended for certain circumstances, such as the initial assessment of the patient on arrival to the PARU; an uncomplicated unconscious patient; a patient requiring continuous airway support; all paediatric patients until they meet the discharge criteria; and during the initiation of intravenous (IV) pain protocol administration.

• A 2:1 nurse-to-patient ratio (or higher) is required during the initial reception phase of a critically ill, complicated or unstable patient.

• A minimum of a 1:2 nurse-to-patient ratio is recommended in circumstances in the stabilisation phase where the patient is conscious and haemodynamically stable.

• A minimum of a 1:3 nurse-to-patient ratio can be considered during the predischarge phase for an uncomplicated patient who is ready for discharge from the PARU.

• In the Stage II area a minimum of a 1:4 nurse-to-patient ratio is recommended for low-acuity, uncomplicated patients, with a higher staffing ratio to be considered when higher acuity patients are admitted to the area.3

The initial admission of the patient to the PARU results from a joint effort between the PAR nurse and the anaesthetist. This collaborative effort fosters the smooth transfer of the patient from the OR to the PARU and ensures that a designated area in the PARU is equipped to receive and manage the patient postoperatively.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

On admission of the patient to the PARU, the anaesthetist provides a handover report to the PAR nurse, including the patient’s preoperative history, pertinent intraoperative information and postanaesthesia orders, such as anticipated postoperative problems. Box 19-1 summarises the components of a complete postanaesthesia report. While the patient is in the PARU, priority care includes monitoring and management of respiratory and circulatory function, pain and temperature, and observation of the surgical site. Postoperative management of the patient includes anticipation and treatment of any complication that may arise while the patient is in the PARU.4

Assessment should commence with an evaluation of the airway, breathing and circulation (ABC) status of the patient. An assessment of the patient’s airway patency and rate and quality of respirations is conducted, including auscultation of breath sounds throughout the lung fields. This may include the assessment of an artificial airway until it can be safely removed. Artificial airways are used to maintain patency of the airway and may involve the use of a balloon-cuffed endotracheal/nasotracheal tube, an oropharyngeal tube or a nasopharyngeal tube. The airway must be kept clear of all secretions to ensure that adequate gaseous exchange can occur, and an artificial airway should not be removed until the laryngeal and pharyngeal reflexes have returned. These reflexes ensure that the patient is able to control the tongue, coughing and swallowing.

Oxygen therapy is delivered via a nasal cannula or a face mask if the patient has had a general anaesthetic, as even healthy patients are at risk of developing transient hypoxaemia during the emergence phase. The use of oxygen aids in the elimination of anaesthetic gases and helps meet the increased demand for oxygen due to a decreased blood volume or increased cellular metabolism. Postoperative mechanical ventilation will be commenced if required by the patient while in the PARU. Pulse oximetry monitoring is initiated as it provides a non-invasive means of assessing the adequacy of oxygenation. However, its use has not been shown to affect the outcome of anaesthetic recovery.5 (Pulse oximetry is discussed in more detail in Ch 25.)

During the initial assessment of the respiratory system, signs of inadequate oxygenation and ventilation should be identified (see Box 19-2), as these require prompt intervention.6 Common respiratory postanaesthesia problems in the PARU are discussed in the section on nursing management of respiratory complications.

Electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring is initiated to determine cardiac rate and rhythm. Deviations from preoperative findings should be noted and evaluated. Blood pressure should be measured and compared with baseline readings or parameters as determined by the anaesthetist. Invasive monitoring (e.g. arterial blood pressure monitoring) will be initiated if required or intraoperative monitoring continued in the PARU. Body temperature and skin colour and turgor should also be included in the assessment to determine the adequacy of the cardiovascular system. Any evidence of inadequate perfusion will require prompt intervention. Commonly encountered cardiovascular problems in the PARU are discussed in the section on nursing management of cardiovascular complications.

The initial neurological assessment focuses on the level of consciousness; orientation; sensory and motor status; and size, equality and reactivity of the pupils. The patient’s level of consciousness may vary from being fully awake to being completely anaesthetised. Occasionally the patient may wake up agitated, which is referred to as emergence delirium. The PAR nurse, who is also responsible for ensuring the patient’s safety until the patient is fully awake, facilitates orientation of the patient. If the patient has had a regional anaesthetic (e.g. spinal or epidural), sensory and motor blockade may still be present. Careful positioning of the patient is required to prevent overextension of the joints. Assessment of the residual effects of the block must be conducted until adequate return of both motor and sensory functions occurs.

The assessment of the urinary system focuses on intake, output and fluid balance. Intraoperative fluid totals are communicated as part of the anaesthesia report. The PAR nurse should note the presence of all intravenous lines, irrigation solutions and infusions, and all output devices, including catheters and wound drains. Intravenous infusions are regulated according to postoperative orders.

The PAR nurse should also assess the surgical site, noting the condition of any dressings and the type and amount of any drainage. Postoperative orders related to site care are instituted. All data obtained during the initial assessment are documented on a PARU record, a form that is specific to postanaesthetic and postsurgical nursing management.

Even the patient who has been told what to expect after surgery may be frightened or confused on awakening in the PARU. Because hearing is the first sense to return in the unconscious patient, the nurse should explain all activities to the patient on admission. Orientation to the unit includes informing patients of the time and admission to the recovery room following completion of the surgery. They are also informed that their family or significant other has been notified of their progress. The nurse introduces those involved in caring for the patient, including an explanation of the interventions that are being implemented while in the PARU.

After the initial assessment has been completed, the PAR nurse continues to assess and provide interventions as required during the ongoing management of the patient. The patient’s response to the nursing interventions is documented until it has been assessed that the patient has met the criteria for discharge from the recovery room.

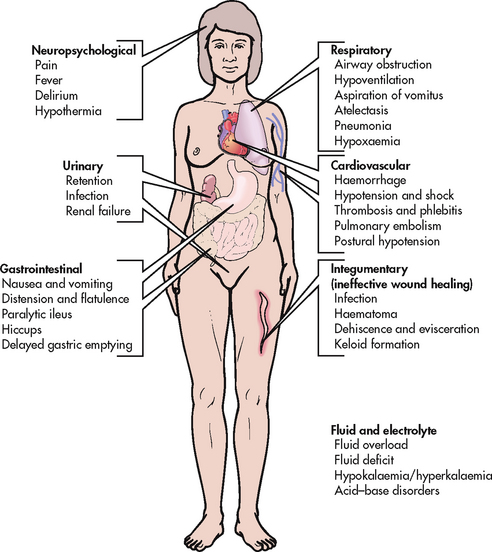

Common postoperative complications that may occur in the PARU include airway compromise (obstruction), respiratory insufficiency (hypoxaemia and hypercarbia), cardiac compromise (hypotension, hypertension and arrhythmias), neurological compromise (emergence delirium and delayed awakening), pain, hypothermia, and nausea and vomiting (see Fig 19-1). Each of these problems and appropriate nursing interventions are discussed in this chapter.

Potential alterations in respiratory function

AETIOLOGY

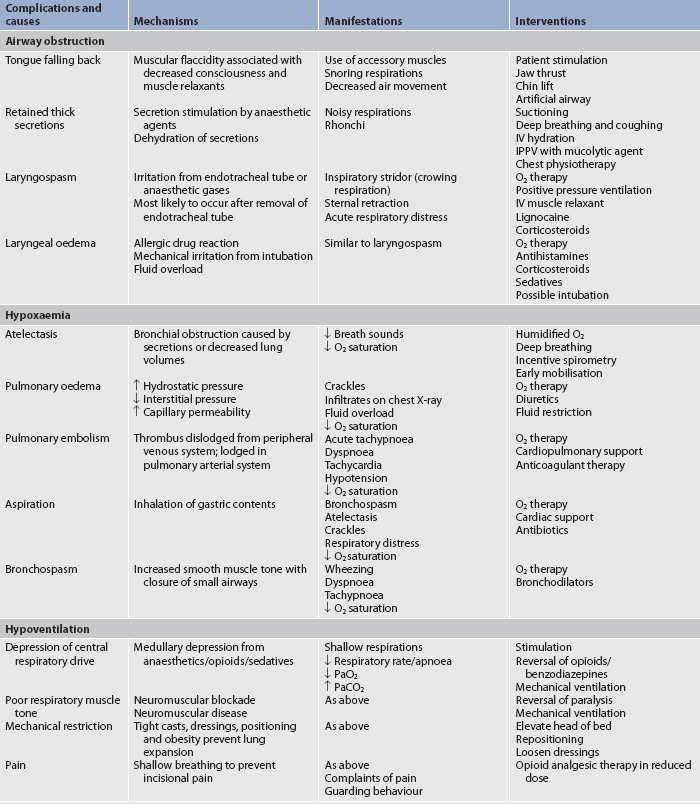

In the immediate postanaesthetic period the most common causes of airway compromise include airway obstruction, hypoxaemia and hypoventilation (see Table 19-1). Postoperatively, patients at risk of developing airway complications include older and obese patients, patients recovering from a general anaesthetic, patients with a history of smoking or with pre-existing lung disease, or patients who have undergone thoracic or abdominal surgery. However, respiratory complications may occur with any patient who has been anaesthetised.

TABLE 19-1 Common immediate postoperative respiratory complications

IPPV, intermittent positive pressure ventilation; IV, intravenous.

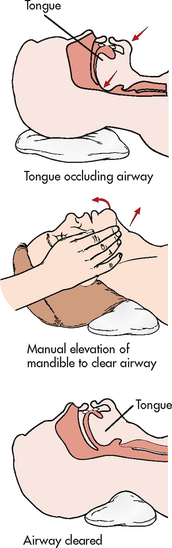

Airway obstruction is most commonly caused by the patient’s tongue blocking the airway (see Fig 19-2). The base of the tongue falls backwards against the soft palate and occludes the pharynx. This is most pronounced in the supine position and in the patient who is extremely drowsy after surgery. Less common causes of airway obstruction include laryngospasm, retained secretions and laryngeal oedema.

Hypoxaemia, specifically a PaO2 of less than 60 mmHg (8 kPa), is characterised by a variety of non-specific clinical signs and symptoms, which include early signs such as agitation, hypertension, tachycardia, tachypnoea and altered mental status. Late signs include hypotension, bradycardia, somnolence and cardiac arrest. The routine use of pulse oximetry will easily detect a low oxygen saturation (<90–92%), which requires confirmation by performing an arterial blood gas analysis.

The most common cause of postoperative hypoxaemia is atelectasis. Atelectasis (alveolar collapse) may be the result of bronchial obstruction caused by retained secretions or decreased respiratory excursion. Hypotension and low cardiac output states can also contribute to the development of atelectasis. Other causes of hypoxaemia that may occur in the patient in the PARU include pulmonary oedema, aspiration and bronchospasm.

Pulmonary oedema is caused by an accumulation of fluid in the alveoli and may be as a result of fluid overload, left ventricular failure or prolonged airway obstruction, sepsis or aspiration. Pulmonary oedema is characterised by hypoxaemia, crackles on auscultation, decreased pulmonary compliance and the presence of infiltrates on chest X-ray.

Aspiration of gastric contents into the lungs is a potentially serious airway emergency. Symptoms include bronchospasm, hypoxaemia, atelectasis, interstitial oedema, alveolar haemorrhage and respiratory failure. Gastric aspiration may also cause laryngospasm, infection and pulmonary oedema. Because of the serious consequences of gastric aspiration, prevention is the best treatment for patients at risk of aspiration. Patients identified as being at risk (patients who are obese, pregnant, have a history of hiatus hernia, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer or trauma) may be premedicated with a histamine H2-receptor antagonist (e.g. ranitidine) or an antacid (e.g. sodium citrate) before induction of anaesthesia. The anaesthetist will take special precautions to protect the airway during induction of and emergence from anaesthesia.

Bronchospasm is the result of an increase in bronchial smooth muscle tone with resultant closure of the small airways. Airway oedema develops, causing secretions to build up in the airway. The patient will present with wheezing, dyspnoea, use of accessory muscles, hypoxaemia and tachypnoea. Bronchospasm may be due to aspiration, endotracheal intubation, suctioning or chemical mediator release as a result of an allergic response. (Allergic responses are discussed in Ch 13.) Bronchospasm is seen more frequently in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Hypoventilation, a common complication in the PARU, is characterised by a decreased respiratory rate or effort, hypoxaemia and an increasing PaCO2 (hypercapnia). Hypoventilation may occur as a result of depression of the central respiratory drive (secondary to anaesthesia or pain medication) or poor respiratory muscle tone (secondary to neuromuscular blockade or disease), or a combination of both.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

To assess for respiratory adequacy, the PAR nurse must evaluate airway patency, chest symmetry and the depth, rate and character of respirations. The nurse can place a cupped hand over the patient’s nose and mouth to evaluate the forcefulness of exhaled air.

The chest wall should be observed for symmetry of movement with a hand placed lightly over the xiphoid process. Impaired ventilation may initially be detected by the observation of slowed breathing or diminished chest and abdominal movement during the respiratory cycle. It should also be determined whether abdominal or accessory muscles are being used for breathing. Observable use of these muscles may indicate respiratory distress.

Breath sounds should be auscultated anteriorly, laterally and posteriorly along the chest wall. Decreased or absent breath sounds will be detected when airflow is diminished or obstructed. The presence of crackles or wheezes requires notification to the anaesthetist.

Regular monitoring of vital signs and use of pulse oximetry in conjunction with thorough respiratory assessment enable the nurse to recognise early signs of respiratory complications. Rapid breathing, gasping, apprehension, restlessness and a rapid or thready pulse may reflect the presence of hypoxaemia from any cause. The use of capnography in monitoring carbon dioxide levels in respiratory gases in the PARU provides an early warning of inadequate respiration during anaesthesia emergence, preventing potentially catastrophic events from occurring.

The characteristics of sputum or mucus should be noted and recorded. Mucus from the trachea and throat is colourless and thin in consistency, whereas sputum, which is obtained from the lungs and bronchi, is thick with a slight yellow tinge.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems related to potential respiratory complications for the patient in the PARU include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

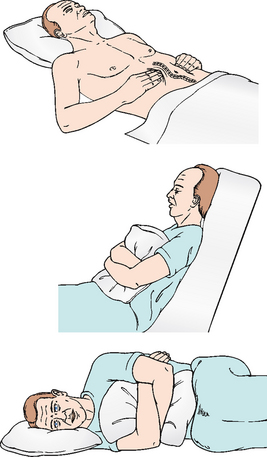

In the PARU, nursing interventions are designed to both prevent and treat respiratory problems. Proper positioning of the patient to facilitate respirations and protect the airway is essential. Unless contraindicated by the surgical procedure, the unconscious patient is positioned in a lateral ‘recovery’ position (see Fig 19-3). This recovery position keeps the airway open and reduces the risk of aspiration if vomiting occurs.7 Once conscious, the patient is usually returned to a supine position with the head of the bed elevated. This position maximises expansion of the thorax by decreasing the pressure of the abdominal contents on the diaphragm.

Deep breathing is encouraged to facilitate gas exchange and to promote the return to consciousness. The patient should be taught to take in slow, deep breaths, ideally through the nose, hold the breath and then exhale slowly. This type of breathing is also useful as a relaxation strategy when the patient is anxious or in pain. Other nursing interventions appropriate for specific respiratory complications are detailed in Table 19-1.

Potential alterations in cardiovascular function

AETIOLOGY

In the immediate postanaesthetic period the most common cardiovascular complications include hypotension, hypertension and cardiac arrhythmias. Patients at greatest risk of alterations in cardiovascular function include patients with alterations in respiratory function, patients with a history of cardiac disease, and older, debilitated and critically ill patients.

Signs of hypoperfusion to the vital organs, especially the brain, heart and kidneys, are evidence of hypotension. Clinical signs of disorientation, loss of consciousness, chest pain, oliguria and anuria reflect hypoxaemia and the loss of physiological compensation. Intervention must be timely to prevent the devastating complications of cardiac ischaemia or infarction, cerebral ischaemia, renal ischaemia and bowel infarction.

The most common cause of hypotension in the PARU is hypovolaemia and blood loss. As a result, treatment will be aimed at restoring circulating volume. If there is no response to fluid administration, cardiac dysfunction should be considered as the cause of hypotension.

Primary cardiac dysfunction, as may occur in the case of myocardial infarction, cardiac tamponade or pulmonary embolism, results in an acute fall in cardiac output. Secondary myocardial dysfunction occurs as a result of the negative chronotropic (rate) and negative inotropic (force) effects of medications, such as β-adrenergic blockers, digoxin or opioids. Other causes of hypotension include decreased systemic vascular resistance, arrhythmias and measurement errors that may occur if a blood pressure cuff is incorrectly sized.

Hypertension, a common finding in the PARU, is most frequently the result of sympathetic nervous stimulation that may be the result of pain, anxiety, bladder distension or respiratory compromise. Hypertension may also be the result of hypothermia and pre-existing hypertension. It may be observed following vascular and cardiac surgery as a result of revascularisation.

Arrhythmias are often the result of an identifiable cause as opposed to myocardial injury. The leading causes include hypocalcaemia, hypoxaemia, hypercarbia, alterations in acid–base status, circulatory instability and pre-existing heart disease. Hypothermia, pain, surgical stress and many anaesthetic agents are also responsible for causing arrhythmias.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: CARDIOVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: CARDIOVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

The most important aspect of the cardiovascular assessment is frequent monitoring of vital signs. They are usually monitored every 15 minutes, or more often until the patient’s condition is stabilised, and then performed at less frequent intervals. Postoperative vital signs should be compared with preoperative and intraoperative readings to determine a return to normal cardiovascular functioning for the patient. The anaesthetist or surgeon should be notified if the following observations are noted:

• systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg or greater than 160 mmHg

• pulse rate less than 60 beats per minute or greater than 120 beats per minute

• narrowing pulse pressure (difference between systolic and diastolic pressures)

• gradually decreasing blood pressure over several consecutive readings

Cardiac monitoring is recommended for patients who have a history of cardiac disease and for all older adult patients who have undergone major surgery, irrespective of their cardiac history. The apical–radial pulse should be assessed carefully and any irregularities should be reported.8

Assessment of skin colour, temperature and moisture provides valuable information in detecting cardiovascular problems. Hypotension accompanied by a normal pulse and warm, dry, pink skin usually represents the residual vasodilating effects of anaesthesia and suggests only a need for continued observation. Hypotension accompanied by a rapid pulse and cold, clammy, pale skin may be caused by impending hypovolaemic shock and requires immediate treatment.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems related to potential cardiovascular complications for the patient in the PARU include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Nursing interventions in the PARU are designed to prevent and treat cardiovascular complications. Treatment of hypotension should always commence with oxygen therapy to promote oxygenation of hypoperfused organs. Volume status should be assessed as described and errors of blood pressure measurement should be determined. Because the most common cause of hypotension is fluid loss, intravenous fluid boluses should be given to normalise blood pressure. Primary cardiac dysfunction may require medication intervention. Peripheral vasodilation and hypotension may require vasoconstrictive agents to normalise systemic vascular resistance.

Treatment of hypertension focuses on addressing the cause of sympathetic stimulation and eliminating the precipitating cause. Treatment may include the use of analgesics, assistance in voiding and correction of respiratory problems. Rewarming will correct hypothermia-induced hypertension. If the patient has pre-existing hypertension or has undergone cardiac or vascular surgery, medication therapy designed to reduce blood pressure will usually be required.

Because the majority of arrhythmias seen in the PARU have identifiable causes, treatment is directed towards eliminating the cause. Correction of these physiological alterations will, in most instances, correct the arrhythmias. In the event of life-threatening arrhythmias, protocols of advanced cardiac life support will be applied (see Ch 35).

Potential alterations in neurological function

AETIOLOGY

Postoperatively, emergence delirium remains the neurological alteration that causes the most concern for the PAR nurse.9 Emergence delirium, or violent emergence, can include behaviours such as restlessness, agitation, disorientation, thrashing and shouting. Anaesthetic agents, hypoxia, bladder distension, pain, electrolyte abnormalities or the patient’s state of anxiety may cause this condition. Nurses may be able to affect the patient’s recovery by using interventions to decrease anxiety.

Delayed awakening may also be a problem postoperatively. The most common cause of delayed awakening includes prolonged medication action, particularly opioids, sedatives and inhalational anaesthetics, as opposed to neurological injury. The anaesthetist can predict normal awakening based on the medications used in surgery.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: NEUROLOGICAL COMPLICATIONS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: NEUROLOGICAL COMPLICATIONS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

The patient’s level of consciousness, orientation and ability to follow commands should be assessed. The size, reactivity and equality of the pupils should be determined, and the patient’s sensory and motor status should be included in the assessment. If the neurological status is altered, possible causes should be determined.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses related to potential neurological complications for the patient in the PARU include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

The most common cause of postoperative agitation is hypoxaemia; therefore, an immediate assessment of the patient’s respiratory system should be conducted on admission to the PARU to rule this out as a cause of postoperative delirium. Once all potential causes of agitation have been addressed, sedation may prove beneficial in controlling the patient and providing safety for both the patient and PARU staff. Emergence delirium is usually time limited and will resolve before the patient is discharged from the PARU. Because the most common cause of delayed awakening is prolonged medication action, delays in awakening usually resolve spontaneously with time. If necessary, benzodiazepines and opioids may be pharmacologically reversed with antagonists.

Until the patient is awake and able to communicate effectively, it is the responsibility of the PAR nurse to act as a patient advocate and to maintain patient safety at all times.10 This includes keeping the bed side rails up, securing IV lines and artificial airways, verifying the presence of identification and allergy bands, and monitoring the patient’s physiological status.

Pain and discomfort

AETIOLOGY

One of the challenges facing the PAR nurse is the objective assessment of pain, including the implementation of a safe, effective intervention in managing postoperative pain. Despite the availability of analgesic medications and pain-relieving techniques, pain remains a common problem and a significant fear that patients experience in the PARU and during the postoperative period. Pain may be the result of surgical manipulation, positioning or the presence of internal devices, such as an endotracheal tube or catheter, or it may occur as the patient begins to mobilise postoperatively. Pain is a common reason for a prolonged stay in the PARU and may contribute to complications.11

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PAIN

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PAIN

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

The patient should be observed for indications of pain (e.g. restlessness) and questioned about the degree and characteristics of the pain. Identifying the location of the pain is important as it will assist in the management of the pain. Incisional pain is to be expected but other causes of pain, such as a full bladder, may impact on patients’ experience of pain and therefore require additional interventions to assist in providing patient comfort. Unrelieved surgical pain can induce muscle splinting, which reduces functional capacity and gaseous exchange. The inability to cough associated with this pain results in the retention of secretions, which may contribute to infection and pneumonia, delaying postoperative recovery. The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetist guidelines for acute pain management (PS41) outline pain management measures.12 The assessment of pain involves using a variety of assessment tools, which include describing pain quality and intensity. A pain management tool, such as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), provides an objective measurement of pain whereby patients select a position on the scale representing the level of pain they are experiencing.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient experiencing pain and discomfort include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

The most effective pain intervention includes using a variety of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches.13–15 Intravenous opioids provide the most rapid relief during the immediate postoperative phase. Medications are administered slowly and titrated to allow for optimal pain management with minimal to no adverse medication side effects. More sustained relief may be obtained through the use of epidural catheters, patient-controlled analgesia or regional anaesthetic blockade. Comfort measures, including touch, reuniting the patient and family, and rewarming, also contribute to patient comfort.

Pain management is most likely to be successful if the treatment plan is initiated involving the patient, anaesthetist and PAR nurse. The goals should be determining the most effective therapy, medication and dose, and determining the outcome that is desirable. When the patient is discharged from the PARU to an inpatient unit, the nurse will replace the PAR nurse as a member of the pain management team. For more information on nursing assessment and management of patients in pain, refer to Chapter 8.

Hypothermia

AETIOLOGY

Hypothermia, which is a core temperature of less than 36°C, occurs when heat loss exceeds heat production. Hypothermia may result when heat is lost from a warm body to a cold environment or when heat is lost from body organs exposed to the air.

Although all patients are at risk of hypothermia, the older, debilitated or intoxicated patient is at an increased risk. Long surgical procedures and prolonged anaesthetic administration lead to redistribution of body heat from the core to the peripheries, placing the patient at an increased risk of hypothermia. Complications from hypothermia may include compromised immune function, postoperative pain, bleeding, myocardial ischaemia and delayed medication metabolism, resulting in a prolonged PARU stay.16,17

NURSING MANAGEMENT: HYPOTHERMIA

NURSING MANAGEMENT: HYPOTHERMIA

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Measurement of vital signs, which includes measuring the patient’s body temperature, should be performed on admission to the PARU. Body temperature may be measured orally, via the tympanic membrane or in the axilla. The use of rectal temperature monitoring is rare and the use of skin temperature monitoring is unreliable. The colour and temperature of the skin should also be assessed.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with hypothermia include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Passive rewarming (i.e. shivering) raises basal heat metabolism. Active rewarming requires the application of external warming devices and may include warm blankets, heated aerosols, radiant warmers, forced air warmers or heated water mattresses. When using any external warming device, body temperature should be monitored at 15-minute intervals and care should be taken to prevent skin injuries. In addition, oxygen therapy via nasal prongs or a face mask can be used to treat the increased demand for oxygen accompanying the increase in body temperature. Shivering is usually quickly suppressed by opioids.18 Refer to Chapter 68 for additional management of hypothermia.

Nausea and vomiting

AETIOLOGY

Nausea and vomiting are significant problems in the immediate postoperative period. These problems are responsible for the unanticipated hospital admission of day surgery patients, increased patient discomfort, delays in discharge and patient dissatisfaction with the surgical experience. Numerous factors have been identified as contributing to the development of nausea and vomiting, including anaesthetic agents and techniques, a history of smoking, sex (female), length and type of surgery (eye, ear, abdominal and gynaecological), and a history of nausea and vomiting after surgery or of motion sickness.19

NURSING MANAGEMENT: NAUSEA AND VOMITING

NURSING MANAGEMENT: NAUSEA AND VOMITING

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

High-risk patients should be treated prophylactically and assessment of pain may include questioning patients about nausea.20 If vomiting occurs, it is important to determine the quantity, characteristics and colour of the vomitus.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient experiencing nausea and vomiting include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Intervention for nausea and vomiting is primarily the use of antiemetic or prokinetic medications (see Ch 41). In the PARU, oral fluids should be given only as indicated and tolerated. Intravenous fluids will provide hydration until the patient is able to tolerate oral fluids. Care should also be taken to prevent aspiration if the patient vomits while still drowsy from anaesthesia. Having suction equipment readily available at the patient’s bedside and turning the patient’s head to the side will help protect the patient from aspiration. Other nursing interventions that may be effective include placing the patient in the upright position; slow, deep breathing; mouth care; placing a cool washcloth to the forehead; and emotional support. Selected non-pharmacological interventions should also be considered.21

Surgical-specific care of the patient in the PARU

In addition to meeting the postanaesthesia needs of the patient in the PARU, the PAR nurse also attends to the surgery-specific (e.g. abdominal, thoracic) needs of the patient. The nursing assessment and management of the patient having a specific surgical procedure are discussed in the appropriate chapters of this text.

Discharge from the PARU

On discharge from the PARU, patients may be admitted to an intensive care unit, an inpatient unit or a day surgery care unit or directly discharged to their home. The choice of discharge site is based on patient acuity, access to follow-up care and the potential development of postoperative complications.

While the discharge of the patient from the PARU remains the responsibility of the anaesthetist, which extends into the postoperative phase, accountability for the patient’s wellbeing is transferred to the PAR nurse once the patient is admitted to the PARU unless the patient’s condition requires the intervention of the anaesthetist. This requires strict discharge criteria to be developed, ensuring a uniform approach to patient discharge from the PARU.

The decision to discharge the patient from the PARU is based on specific written discharge criteria contained within clinical guidelines or protocols that state the need for a patient to meet certain criteria prior to discharge from the PARU.22 Depending on the area of discharge, criteria will vary accordingly. Patients should be observed for at least 20–30 minutes following the administration of parenteral narcotics. Discharge from a day surgery PARU requires that the patient meet additional criteria. Examples of discharge criteria are provided in Box 19-3.

BOX 19-3 Postanaesthesia and day surgical discharge criteria

DAY SURGERY DISCHARGE

Day surgery patients in the PARU include outpatients, same-day surgery patients and short-stay patients. Because patients’ exposure to the healthcare setting is brief, preoperative information required by patients is hampered by the lack of time available during their surgical admission. Ideally, patients and their caregivers should be contacted one or more days before surgery to collect assessment data and to provide education that will be required to enhance the postoperative experience.

Patients discharged from a day surgery setting must be mobile and alert in order to be able to provide a degree of self-care on return to their home. Postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting must be controlled. Overall, the patient must be stable and near the level of preoperative functioning for discharge from the unit. On discharge, instructions specific to the type of anaesthesia administered and the surgery should be communicated verbally and reinforced with written directions. The type of information included in teaching is detailed later in this chapter.

The patient may not drive a motor vehicle and must be accompanied by a responsible adult at the time of discharge. A follow-up evaluation of the patient’s status is made by telephone and any specific questions and concerns should be addressed.

Although day surgical procedures are minimally invasive, the nurse must carefully determine not only the patient’s readiness for discharge but also their home care needs. It is important to determine the availability of assistive personnel (e.g. family, friends), access to a pharmacy for prescriptions, access to a telephone in the event of an emergency and access to follow-up care.23,24

CARE OF THE POSTOPERATIVE PATIENT IN THE SURGICAL UNIT

Before discharging the patient from the PARU to the surgical unit, the PAR nurse provides a verbal report about the patient to the receiving nurse. The report summarises the operative and postanaesthetic period.

The nurse who receives the patient in the surgical unit assists PARU transport personnel in transferring the patient from the PARU trolley onto the bed. Care must be taken to protect IV lines, wound drains, dressings and traction devices. The use of a slide sheet, transfer board and sufficient personnel is necessary to facilitate the safe transfer of the patient.

Vital signs should be obtained and patient status should be compared with the report provided by the PAR nurse. Documentation of the transfer is then completed, followed by a more in-depth assessment (see Box 19-4). Postoperative orders and appropriate nursing care are then initiated.

BOX 19-4 Nursing assessment and care of patient on admission to surgical unit

NURSING ASSESSMENT

• Record time of patient’s return to unit

• Assess airway and breath sounds

• Assess neurological status, including level of consciousness and movement of extremities

• Assess wound, dressing, drainage tubes

• Assess colour and appearance of skin

• Position for airway maintenance, comfort, safety (bed in low position, side rails up)

• Attach call light within reach and orient patient to use of call light

• Ensure that emesis basin and tissues are available

• Determine emotional condition and support

Although many of the potential problems that may occur in the PARU are time limited to the immediate postoperative period, a number of potential complications may occur during the extended postoperative recovery period in the clinical unit. Nursing assessment and management are based on an awareness of the potential complications of surgery in general, as well as the complications specific to the surgical procedure. A general nursing care plan for the postoperative patient is presented in NCP 19-1.

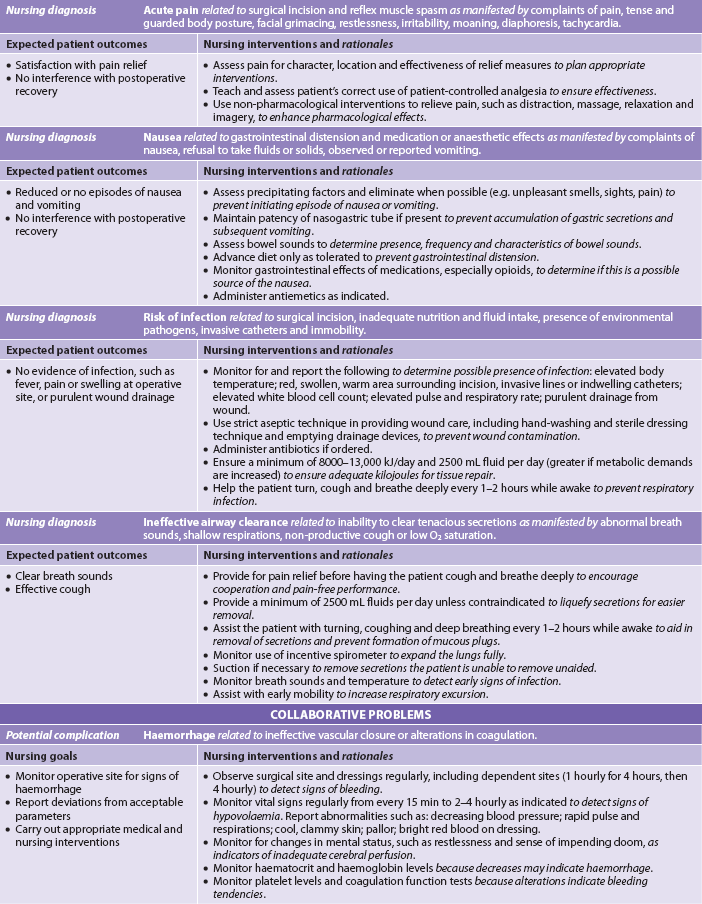

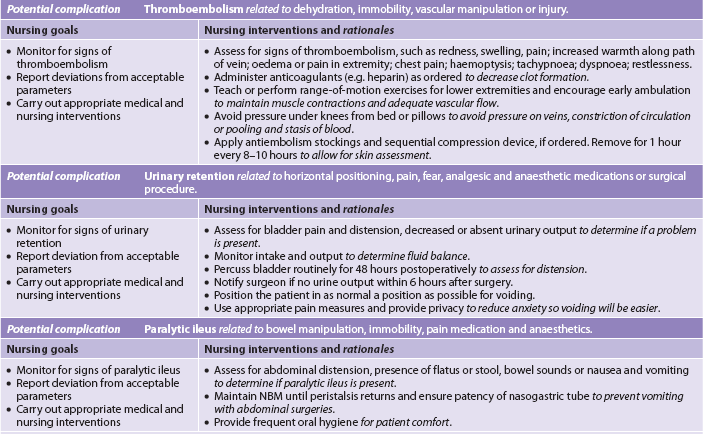

NURSING CARE PLAN 19-1 Postoperative patient*

*This is a general nursing care plan for the postoperative patient. It should be used in conjunction with a nursing care plan specific to the type of surgery performed.

Early ambulation is the most significant general nursing measure to prevent postoperative complications. Since it was first advocated nearly 40 years ago, the value of early ambulation has been obvious. The exercise associated with walking: (1) increases muscle tone; (2) improves gastrointestinal (GI) and urinary tract function; (3) stimulates circulation, which prevents venous stasis and speeds wound healing; and (4) increases vital capacity and maintains normal respiratory function.25

Potential alterations in respiratory function

AETIOLOGY

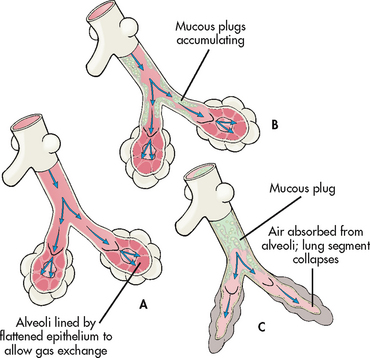

Atelectasis and pneumonia can occur in the postoperative surgical patient and are more common following abdominal and thoracic surgery. Atelectasis occurs when mucus blocks bronchioles or when the amount of alveolar surfactant (the substance that holds the alveoli open) is reduced (see Fig 19-4). As air becomes trapped beyond the plug and is eventually absorbed, the alveoli collapse. Atelectasis may affect a portion or an entire lobe of the lungs.

Figure 19-4 Postoperative atelectasis. A, Normal bronchiole and alveoli. B, Mucous plug in bronchiole. C, Collapse of alveoli due to atelectasis following absorption of air.

The postoperative development of mucous plugs and decreased surfactant production are directly related to hypoventilation, constant recumbent position, ineffective coughing and smoking. Increased bronchial secretions occur when heavy smoking, acute or chronic pulmonary infection or disease, and the drying of mucous membranes that occurs with intubation, inhalation anaesthesia and dehydration irritate the respiratory passages. Without intervention, atelectasis can progress to pneumonia when microorganisms grow in the stagnant mucus and an infection develops.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment of the patient’s respiratory rate, patterns and breath sounds is essential to identify potential respiratory problems.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems related to potential respiratory complications for the postoperative patient include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Deep-breathing and coughing techniques help the patient to prevent alveolar collapse and move respiratory secretions to larger airway passages for expectoration. The patient should be assisted to breathe deeply 10 times every hour while awake. The use of an incentive spirometer is helpful in providing visual feedback of respiratory effort. Diaphragmatic or abdominal breathing is accomplished by inhaling slowly and deeply through the nose, holding the breath for a few seconds and then exhaling slowly and completely through the mouth. The patient’s hands should be placed lightly over the lower ribs and upper abdomen. This allows the patient to feel the abdomen rise during inspiration and fall during expiration.

Effective coughing is essential to mobilise secretions (refer to Ch 28). If secretions are present in the respiratory passages, deep breathing often will move them up to stimulate the cough reflex without any voluntary effort by the patient, and they can then be expectorated. Splinting an abdominal incision with a pillow or a rolled blanket provides support to the incision and aids in coughing and expectoration of secretions (see Fig 19-5).

The patient’s position should be changed every 1–2 hours to allow full chest expansion and increase perfusion in both lungs. Ambulation, not just sitting in a chair, should be aggressively carried out as soon as the surgeon gives approval. Adequate and regular analgesic medication should be provided because incisional pain often is the greatest deterrent to patient participation in effective ventilation and ambulation. The patient should also be reassured that these activities will not cause the incision to separate. Adequate hydration, either parenteral or oral, is essential to maintain the integrity of mucous membranes and to keep secretions thin and loose for easy expectoration.

Potential alterations in cardiovascular function

AETIOLOGY

Postoperative fluid and electrolyte imbalances are contributing factors to alterations in cardiovascular function. They may develop as a result of a combination of the body’s normal response to the stress of surgery, excessive fluid losses and improper IV fluid replacement. The body’s fluid status directly affects cardiac output. Fluid retention during the first 2–5 postoperative days can be the result of the stress response. This body response serves to maintain both blood volume and blood pressure. Fluid retention results from the secretion and release of two hormones by the pituitary—antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH)—and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. ADH release leads to increased water reabsorption and decreased urinary output, increasing blood volume. ACTH stimulates the adrenal cortex to secrete aldosterone. Fluid losses resulting from surgery decrease kidney perfusion, stimulating the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and causing marked release of aldosterone (see Ch 16). Both of the mechanisms that increase aldosterone lead to significant sodium and fluid retention, which also increase blood volume.

Fluid overload may occur during this period of fluid retention when IV fluids are administered too rapidly, when chronic (e.g. cardiac or renal) disease exists or in the elderly patient. Conversely, fluid deficit may be related to slow or inadequate fluid replacement, which leads to decreases in cardiac output and tissue perfusion. Untreated preoperative dehydration or intraoperative or postoperative losses from vomiting, bleeding, wound drainage or suctioning may be contributing factors to fluid deficit.

Hypokalaemia can be a consequence of urinary and GI tract losses, and results when potassium is not replaced in IV fluids. Low serum potassium levels directly affect the contractility of the heart and thus may also contribute to decreased cardiac output and overall body tissue perfusion. Adequate replacement of potassium is usually 40 mmol per day. However, it should not be given until adequate renal function has been established. A urine output of at least 0.5 mL/kg per hour is generally considered indicative of adequate renal function.

Cardiovascular status is also affected by the state of tissue perfusion or blood flow. The stress response contributes to an increase in clotting tendencies in the postoperative patient by increasing platelet production. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) may occur in leg veins as a result of inactivity, body position and pressure, all of which result in venous stasis and decreased perfusion. DVT, which is especially common in the older adult, obese individual and immobilised patient, is a potentially life-threatening complication because it may lead to pulmonary embolism. Therefore, patients with a history of DVT have a greater risk of developing a pulmonary embolism.26 Pulmonary embolism should be suspected in any patient complaining of tachypnoea, dyspnoea and tachycardia, particularly when the patient is already receiving oxygen therapy. Manifestations may include chest pain, hypotension, haemoptysis, arrhythmias and heart failure. Definitive diagnosis requires pulmonary angiography. Superficial thrombophlebitis is an uncomfortable but less ominous complication that may develop in a leg vein as a result of venous stasis or in the arm veins as a result of irritation from IV catheters or solutions. If a piece of a clot becomes dislodged and travels to the lung, it can cause a pulmonary infarction of a size proportional to the vessel in which it lodges.

Syncope (fainting) is another factor that reflects the cardiovascular status. It may indicate decreased cardiac output, fluid deficits or defects in cerebral perfusion. Syncope frequently occurs as a result of postural hypotension when the patient ambulates. It is more common in the older adult or in the patient who has been immobile for long periods of time. Normally when the patient moves suddenly to a standing position, the arterial pressure receptors respond to the accompanying fall in blood pressure with sympathetic nervous stimulation, which produces vasoconstriction. This sympathetic nervous system response causes an increase in, and therefore maintains, blood pressure. These sympathetic and vasomotor functions may be diminished in the older adult and the immobile or postanaesthetic patient, therefore increasing the risk of developing syncope.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: CARDIOVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: CARDIOVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Specific assessment of cardiovascular function includes regular monitoring of the patient’s blood pressure, heart rate, pulses, and skin temperature and colour. Results should be compared with preoperative status and the immediate postoperative and intraoperative findings.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems related to potential cardiovascular complications for the postoperative patient include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

An accurate intake and output record should be maintained during the postoperative period, and laboratory findings (e.g. electrolytes, haematocrit) should be monitored. Nursing responsibilities relating to IV management are critical during this period. In particular, the nurse should be alert for symptoms of too slow or too rapid a rate of fluid replacement. Assessment should also be made of the infusion site for discomfort and the hazards associated with the IV administration of potassium, such as cardiac arrest and pain in the area surrounding the vein. Thirst is one of the most annoying discomforts for postoperative patients. This may be related to the drying effects of anticholinergic medications, anaesthetic gases and fluid deficits. Adequate and regular mouth care is helpful while the patient is unable to tolerate food or drink by mouth.

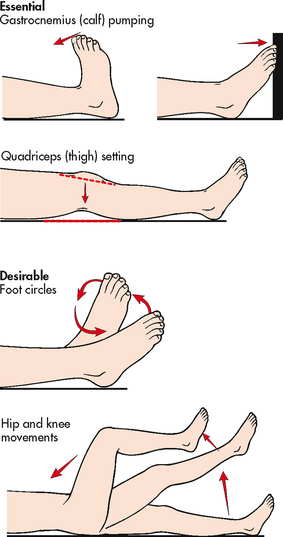

Leg exercises (see Fig 19-6) should be encouraged 10–12 times every 1–2 hours while awake. The muscular contraction produced by these exercises and by ambulation facilitates venous return from the lower extremities. Ambulating patients should lift their feet while walking rather than shuffling so that muscular contraction is maximised. When confined to bed, the patient should alternately flex and extend the legs. While sitting in a chair or lying in bed, the patient should be checked to ensure that there is no pressure impeding venous flow through the popliteal space. Crossed legs, pillows behind the knees and extreme elevation of the knee must be avoided.

Some surgeons routinely prescribe elastic stockings or mechanical aids, such as sequential compressive devices, to stimulate and enhance the massaging and milking actions that are transmitted to the veins when leg muscles contract. The nurse must remember that these aids are useless if the legs are not exercised and may actually impair circulation if the legs remain inactive or if the devices are sized or applied incorrectly. When in use, elastic stockings must be removed and reapplied at least twice daily for skin care and inspection. The skin of the heels and post-tibial areas is particularly susceptible to increased pressure and breakdown.

The use of unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is a prophylactic measure for venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The advantages of LMWH over unfractionated heparin include: (1) reduction in major bleeding; (2) decreased incidence of thrombocytopenia; (3) better absorption; (4) longer duration of action; (5) as effective or more effective; and (6) no laboratory monitoring required.27

The nurse may prevent syncope by making changes in the patient’s position slowly. Progression to ambulation can be achieved by first raising the head of the patient’s bed for 1–2 minutes and then by assisting the patient to sit on the side of the bed while monitoring the radial pulse for rate and quality. If no changes or complaints are noted, ambulation can be initiated. If faintness occurs, the nurse can help the patient to sit on the edge of the bed while continuing to monitor the pulse. If changes occur or if the patient complains of feeling faint during ambulation, the nurse should provide assistance to a nearby chair or ease the patient to the floor. The patient should remain in either location until recovery is evidenced by blood pressure stability and then be assisted back to the bed. If faintness occurs, it is often frightening for the patient and for the unprepared nurse, but syncope poses no real physiological danger, although injury can result from a fall.

Potential alterations in urinary function

AETIOLOGY

Low urine output (800–1500 mL) in the first 24 hours may be expected, regardless of fluid intake. This low output is caused by increased aldosterone and ADH secretion, resulting from the stress of surgery, fluid restriction before surgery, and loss of fluids during surgery, drainage and diaphoresis. By the second or third day, the patient will begin to have increasing urinary output after fluid has been mobilised and the immediate stress reaction subsides.

Acute urinary retention can occur in the postoperative period for a variety of reasons. Anaesthesia depresses the nervous system, including the micturition reflex arc and the higher centres that influence it. This allows the bladder to fill more completely than normal before the urge to void is felt. Anaesthesia also impedes voluntary micturition. Anticholinergic and opioid medications may also interfere with the ability to initiate voiding or to empty the bladder completely.

Urinary retention is more likely to occur after lower abdominal or pelvic surgery because spasms or guarding of the abdominal and pelvic muscles interferes with their normal function in micturition.28 Pain may alter perception and affect the patient’s awareness of the less intense sensation as the bladder fills. Voiding ability is probably impaired to the greatest extent by immobility and the recumbent position in bed. Lack of skeletal muscle activity decreases smooth muscle (bladder detrusor) tone, and the supine position reduces the ability to relax the perineal muscles and external sphincter.

Oliguria, the diminished output of urine, can be a manifestation of acute renal failure and is a less common although more serious problem after surgery. It may result from renal ischaemia caused by inadequate renal perfusion or altered cardiovascular function.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: URINARY COMPLICATIONS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: URINARY COMPLICATIONS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

The urine of the postoperative patient should be examined for both quantity and quality. The colour, amount, consistency and odour of the urine should be noted. Indwelling catheters should be assessed for patency, and urine output should be at least 0.5 mL/kg per hour. If a catheter is not present, the patient should be able to void approximately 200 mL of urine following surgery. Most people urinate within 6–8 hours after surgery. If no voiding occurs, the abdominal contour should be inspected and the bladder palpated and percussed for distension.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems related to potential urinary complications for the postoperative patient include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

The nurse may facilitate voiding by normal positioning of the patient—sitting for women and standing for men. Providing reassurance to the patient regarding the ability to void and using techniques such as running water, drinking water or pouring warm water over the perineum may also be of assistance. Ambulation, preferably to the bathroom, and the use of a bedside commode are additional helpful measures to assist in voiding.

The surgeon may provide a written order for catheterisation of the patient after 8–12 hours if voiding has not occurred. Because of the possibility of infection associated with catheterisation, the nurse should first include other measures to induce voiding and validate that the bladder is actually full. In assessing the need for catheterisation, the nurse should consider fluid intake during and after surgery and determine bladder fullness (e.g. palpable fullness above the symphysis pubis, discomfort when pressure is applied over the bladder or the presence of the urge to void). Straight catheterisation is preferred because of the possibility of infection associated with an indwelling catheter.

Potential alterations in gastrointestinal function

AETIOLOGY

Slowed GI motility and altered patterns of food intake may lead to the development of several distressing postoperative symptoms that are most pronounced after abdominal surgery. Nausea and vomiting may be caused by the action of anaesthetics or opioids, delayed gastric emptying, slowed peristalsis resulting from the handling of the bowel during surgery and resumption of oral intake too soon after surgery.

Abdominal distension is another common problem caused by decreased peristalsis as a result of handling of the intestine during surgery and limited dietary intake before and after surgery. Following abdominal surgery, motility of the large intestine may be reduced for 3–5 days, although motility in the small intestine resumes within 24 hours. Swallowed air and GI secretions may accumulate in the colon, producing distension and gas pains.

Hiccups (singultus) are intermittent spasms of the diaphragm caused by irritation of the phrenic nerve, which innervates the diaphragm. Postoperative sources of direct irritation of the phrenic nerve may be gastric distension, intestinal obstruction, intra-abdominal bleeding and a subphrenic abscess. Indirect irritation of the phrenic nerve may be produced by acid–base and electrolyte imbalances. Reflex irritation may come from drinking hot or cold liquids or from the presence of a nasogastric (NG) tube. Hiccups usually last a short time and subside spontaneously; occasionally they may be persistent but they are rarely debilitating.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: GASTROINTESTINAL COMPLICATIONS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: GASTROINTESTINAL COMPLICATIONS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

The abdomen should be auscultated in all four quadrants to determine the presence, frequency and characteristics of the bowel sounds. Bowel sounds are frequently absent or diminished in the immediate postoperative period when peristalsis is decreased. The return of normal bowel motility is usually accompanied by the passage of flatus in addition to normal bowel sounds. If vomiting occurs, the emesis should be evaluated for colour, consistency and amount.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems related to potential GI complications for the postoperative patient may include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Depending on the nature of the surgery, the patient may resume oral intake as soon as the gag reflex returns. The patient who has had abdominal surgery is usually required to remain nil by mouth (NBM) until the presence of bowel sounds indicates the return of peristalsis. When the patient is NBM, IV infusions are administered to maintain fluid and electrolyte balance. An NG tube may be used to decompress the stomach to prevent nausea, vomiting and abdominal distension. When oral intake is permitted, clear liquids are commenced and the IV infusion is continued, usually at a reduced rate. If oral intake is well tolerated by the patient, the IV infusion is discontinued and the diet is advanced until a regular diet is tolerated.

When the patient is on NBM status, regular mouth care is essential for comfort and stimulation of the salivary glands. Nausea and vomiting may be prevented or relieved by the administration of an antiemetic medication given intravenously, intramuscularly or by rectal suppository. In some instances an NG tube is inserted if symptoms persist.

Abdominal distension may be prevented or minimised by early and frequent ambulation, which stimulates intestinal motility. The nurse should assess the patient regularly to detect the resumption of normal intestinal peristalsis as evidenced by the return of bowel sounds and the passage of flatus. The NG tube must be clamped or suction turned off when the abdomen is auscultated. Resumption of a normal diet after bowel sounds have returned will also enhance the return of normal peristalsis.

The patient may need to be encouraged to expel flatus and assured that expulsion is necessary and desirable. Ambulation and frequent repositioning may relieve gas pains, which tend to become pronounced on the second or third postoperative day. Positioning the patient on the right side permits gas to rise along the transverse colon and facilitates its release. Bisacodyl suppositories may be ordered to stimulate colonic peristalsis and expulsion of flatus and faeces.

The postoperative patient who is hiccupping should first be assessed in an attempt to determine the cause. In many instances simple irrigation of the NG tube to restore patency will solve the problem.

Potential alterations of the integument

AETIOLOGY

Surgery generally involves an incision through the skin and underlying tissues. An incision disrupts the protective skin barrier. Therefore, wound healing is one of the major concerns during the postoperative period.

An adequate nutritional state is essential for wound healing. Amino acids are readily available for the healing process because of the catabolic effects of the stress-related hormones (e.g. cortisol). The patient who was well nourished preoperatively can tolerate the postoperative delay in nutritional intake for several days. However, the patient with pre-existing nutritional deficits that occur with chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes, ulcerative colitis, alcoholism) is more prone to problems associated with wound healing. Wound healing is also a concern for the older adult and is affected by multiple factors. The patient who is unable to meet nutritional needs postoperatively may be provided with total parenteral nutrition to promote healing.

Wound infection may result from contamination of the wound from three major sources: (1) exogenous flora present in the environment and on the skin; (2) oral flora; and (3) intestinal flora. The incidence of wound sepsis is higher in patients who are malnourished, immunosuppressed or older, or who have had a prolonged hospital stay or a lengthy surgical procedure (lasting more than 3 hours). Patients undergoing bowel surgery, especially following a traumatic injury, are at a much higher risk of developing a wound infection due to the risks associated with contamination of the wound during surgery. Infection may involve the entire incision and may extend downwards through the deeper tissue layers. An abscess may form locally or the infection may penetrate entire body cavities, as in peritonitis. Evidence of wound infection usually does not become apparent before the third to the fifth postoperative day. Signs and symptoms include local manifestations of redness, swelling and increasing pain and tenderness at the site. Systemic manifestations are fever and leucocytosis.

An accumulation of fluid in a wound may create pressure, impair circulation and wound healing, and predispose to infection. For these reasons the surgeon may place a drain in the incision or make a stab wound adjacent to the incision to allow drainage. These drains may open into a collection bag or dressing, or they may be firm catheters attached to a self-vacuum system, such as a Jackson-Pratt drain or Redivac drain. Wound healing and complications are discussed in Chapter 12.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: SURGICAL WOUNDS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: SURGICAL WOUNDS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment of the wound and dressing requires knowledge of the type of wound, drains inserted and expected drainage related to the specific type of surgery. A small amount of serous drainage is common from any type of wound. If a drain is in place, a moderate-to-large amount of drainage may be expected. For example, an abdominal incision with an accompanying drain is expected to have a moderate amount of serosanguineous (haemoserous) drainage in the first 24 hours. In contrast, an inguinal hernia repair should have only minimal serous drainage during the postoperative period.

In general, drainage is expected to change from sanguineous (red) to haemoserous (pink) to serous (clear yellow). The drainage output should decrease over hours or days, depending on the type of surgery. Wound infection may be accompanied by purulent drainage. Wound dehiscence (separation and disruption of previously joined wound edges) may be preceded by a sudden discharge of brown, pink or clear drainage.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems related to surgical wounds of the postoperative patient include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

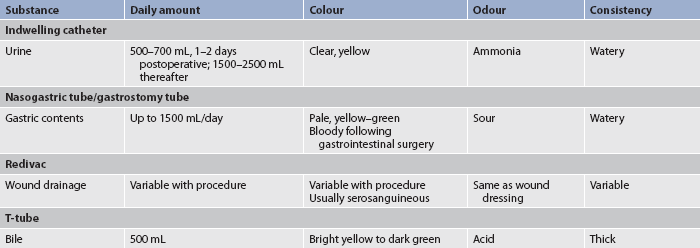

When drainage occurs on the dressing, the type, amount, colour, consistency and odour of drainage should be noted and recorded. Expected drainage from tubes is outlined in Table 19-2. The effect of position changes on drainage should also be assessed. The surgeon should be notified of any excessive or abnormal drainage and significant changes in vital signs.

The incision may initially be covered with a dressing immediately after surgery. If there is no drainage after 24–48 hours, the incision may be opened to the air. Health institution policy and/or surgeon preference usually determines whether the nurse may change the initial operative dressing or simply reinforce it if the dressing is saturated.

When a dressing is changed, the number and type of drains present should be noted. Care should be taken to avoid dislodging drains during dressing removal. When the dressing is changed, the incision site should be examined carefully. The area around the sutures may be slightly reddened and swollen, which is an expected inflammatory response. However, the skin around the incision should be normal in colour and temperature. Clinical manifestations of infection include redness, swelling, pain, fever and increased white blood cell count. The nurse should wear clean gloves when removing a dressing. Sterile technique should be used when any new dressing is applied. If healing is by primary intention, little or no drainage is present and no drains are in place, a single-layer dressing or no dressing is sufficient. When drains are in place, when moderate-to-heavy drainage is occurring or when healing occurs other than by primary intention, a multiple-layer dressing is needed. Wound healing and care are discussed in Chapter 12.

Pain and discomfort

AETIOLOGY

The assessment and management of the patient in pain are discussed in Chapter 8. Postoperative pain is caused by the interaction of a number of physiological and psychological factors. The skin and underlying tissues have been traumatised by the incision and retraction during surgery. In addition, there may be reflex muscle spasms around the incision. Anxiety and fear, sometimes related to the anticipation of pain, create tension and further increase muscle tone and spasm. The effort and movement associated with deep breathing, coughing and changing position may aggravate pain by creating tension or pull on the incisional area.

When the internal viscera are cut, no pain is felt. However, pressure in the internal viscera elicits pain. Therefore, deep visceral pain may signal the presence of a complication such as intestinal distension, bleeding or abscess formation.

Postoperative pain is usually most severe within the first 48 hours and subsides thereafter. Variation is considerable, according to the procedure performed and the patient’s individual pain tolerance or perception.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PAIN

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PAIN

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Pain assessment may be difficult in the early postoperative period. The patient may not be able to verbalise the presence or severity of pain. The nurse should observe for behavioural clues of pain, such as a wrinkling face or brow, a clenched fist, moaning, diaphoresis or an increased pulse rate.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses related to pain for the postoperative patient may include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Postoperative pain relief is a nursing responsibility because the surgeon’s orders for analgesic medication and other comfort measures are usually written on an as-needed basis. During the first 48 hours or longer, opioid analgesics (e.g. morphine) are required to relieve moderate-to-severe pain. After that time, non-opioid analgesics, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, may be sufficient as pain intensity decreases. Effective pain management promotes optimal healing, prevents complications and allows patients to participate in necessary activities.29 Analgesic administration should be timed to ensure that it is in effect during activities that may be painful for the patient, such as ambulating. Although opioid analgesics are often essential for the postoperative patient’s comfort, undesirable side effects, such as constipation, nausea and vomiting, respiratory and cough depression, and hypotension, are the most common. Before administering any analgesic, the nurse should first assess the nature of the patient’s pain, including location, quality and intensity. If it is incisional pain, analgesic administration is appropriate. If it is chest or leg pain, medication may simply mask a complication that must be reported and documented prior to analgesic administration. If it is gas pain, opioids can aggravate it; therefore, the nurse should notify the surgeon and request a change in the order. This should also occur if the analgesic either fails to relieve the pain or makes the patient excessively lethargic or somnolent.

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) and epidural analgesia are two alternative approaches for pain control. The goals of PCA are to provide immediate analgesia and to maintain a constant, steady blood level of the analgesic agent. PCA involves self-administration of predetermined doses of analgesia by the patient. The most popular route of delivery is IV; however, oral or epidural may be requested. (PCA is discussed in Ch 8.) Epidural analgesia is the infusion of pain-relieving medications through a catheter placed into the epidural space surrounding the spinal cord. The goal of epidural analgesia is the delivery of medication directly to the opiate receptors in the spinal cord. The administration may be intermittent or continuous and is monitored hourly by the nurse. The overall effectiveness and the technique of administration result in a constant circulating level and a reduced total dose of medication.

Potential alterations in temperature

AETIOLOGY

Temperature variation in the postoperative period provides valuable information about the patient’s status. Hypothermia may be present in the immediate postoperative period while the patient is recovering from the effects of anaesthesia and body heat loss during surgery. Fever may occur at any time during the postoperative period (see Table 19-3). A mild elevation (up to 38°C) during the first 48 hours is reflective of the surgical stress response. A moderate elevation (higher than 38°C) is caused more frequently by respiratory congestion or atelectasis and less frequently by dehydration. After the first 48 hours a moderate-to-marked elevation (higher than 37.7°C) is usually caused by infection.

Wound infection, particularly from aerobic organisms, is often accompanied by a fever that spikes in the afternoon or evening and returns to near-normal levels in the morning. The respiratory tract may be infected secondary to stasis of secretions in areas of atelectasis. The urinary tract may be infected secondary to catheterisation. Superficial thrombophlebitis may occur at the IV site or in the leg veins. The latter may produce a temperature elevation between 7 and 10 days after surgery.

Intermittent high fever accompanied by shaking chills and diaphoresis suggests septicaemia. This may occur at any time during the postoperative period due to the introduction of microorganisms into the bloodstream during surgery, especially in GI or genitourinary (GU) procedures, or later, resulting from a wound site or urinary infection.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ALTERED TEMPERATURE

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ALTERED TEMPERATURE

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Frequent assessment of the patient’s temperature is important to detect patterns of hypothermia and/or fever that may be present in the postoperative period. The nurse should observe the patient for early signs of inflammation and infection so that any complications that arise may be treated in a timely manner.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses related to potential temperature complications for the postoperative patient may include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

The nurse’s role with respect to postoperative fever may be preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic. The patient’s temperature is usually measured every 4 hours for the first 48 hours postoperatively and then less frequently if no problems are identified. Meticulous asepsis is maintained with regard to the wound and IV site, and airway clearance is encouraged. If fever develops, chest X-rays may be taken and, depending on the suspected cause, cultures of the wound, urine or blood are obtained. If infection is the source of the fever, antibiotics are commenced as soon as cultures have been obtained. If the fever rises above 39.4°C, antipyretic medications and body-cooling measures may be implemented.

Potential alterations in psychological function

AETIOLOGY

Anxiety and depression may occur in the postoperative patient. These states may be more pronounced in the patient who has had radical surgery (e.g. colostomy) or amputation or whose findings suggest a poor prognosis (e.g. inoperable tumour). A history of a neurotic or psychotic disorder should alert the nurse to the possibility of postoperative anxiety and depression. However, these responses may develop in any patient as part of the grief response to loss of a body organ or disturbance in body image and may be exacerbated by a lowered response to stress.

The patient who lives alone or requires rehabilitation after surgery may also develop anxiety and depression when faced with the need for assistance postoperatively until strength and independence can be regained. A lack of knowledge about Medicare or insurance payments for rehabilitation and the type of services needed often impair the patient’s ability to make a decision regarding continuing care.

Confusion or delirium may arise from a variety of psychological and physiological sources, including fluid and electrolyte imbalances, hypoxaemia, medication effects, sleep deprivation and sensory alteration, deprivation or overload. Delirium tremens may also occur as a result of alcohol withdrawal in a postoperative patient. Delirium tremens is a reaction characterised by restlessness, insomnia and nightmares, tachycardia, apprehension, confusion and disorientation, irritability, and auditory or visual hallucinations. Management of delirium tremens is discussed in Chapter 10.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PSYCHOLOGICAL FUNCTION

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PSYCHOLOGICAL FUNCTION

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses related to potential alterations in psychological function in the postoperative patient include, but are not limited to, the following:

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation