Ethics – the theory

The major ethical theories and principles applied to decision-making in health care

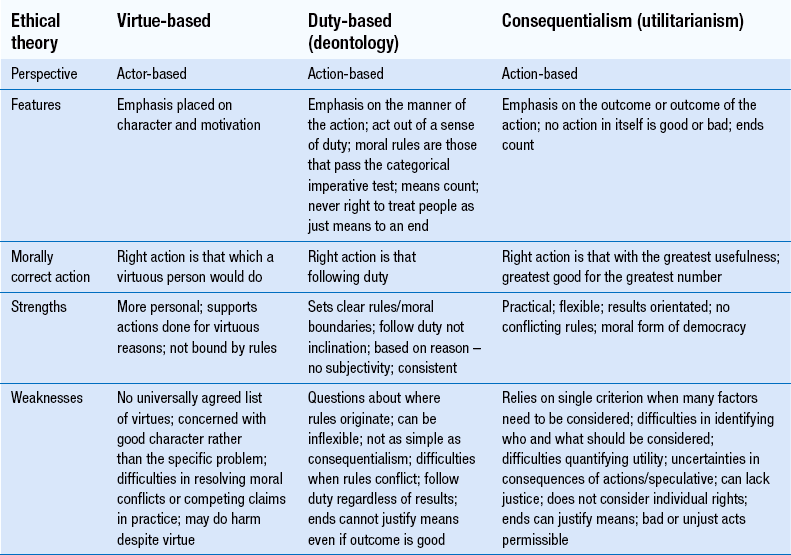

The major ethical theories and principles applied to decision-making in health care

The key limitations of each ethical theory

The key limitations of each ethical theory

The distinction between morals, ethics and law

The distinction between morals, ethics and law

Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to introduce the concept of ethics, briefly explain ethical theories and principles and relate these to issues of relevance in pharmacy and healthcare practice.

Morals, values and ethics

The terms ‘ethics’ and ‘morals’, ‘ethical’ and ‘moral’, are often used interchangeably. They are almost synonymous in that an ethical action is one that is morally acceptable. However, they are not identical. Morals usually refer to practises; ethics is concerned with evaluating such practises. Morality is concerned with the standards of right or wrong behaviour, the values and duties adopted by individuals, groups and society. Personal morals arise from religious beliefs, political views, prejudices and cultural and family backgrounds.

Values are those ideals, beliefs, attitudes and characteristics considered to be valuable and worthwhile by an individual, a group or society in general. Personal values are acquired over a long period of time through interaction with family, friends, school, work, colleagues and role models, and develop and change throughout life. The way in which a person makes personal and professional judgements and choices is influenced by the way they organize, rank and prioritize values in a personal value system.

Ethics is the branch of philosophy that deals with the moral dimension of human life. Ethics deals with what is right and wrong, good and bad, what ought and ought not to be done. It is concerned with actions and judging whether an action is right or wrong and justifying this. The study of ethics is commonly grouped into three areas:

Descriptive ethics simply describes the way things are – how people actually behave

Descriptive ethics simply describes the way things are – how people actually behave

Meta-ethics is concerned with analysis of the language people use when they discuss a moral issue, e.g. the meaning of the words ‘right’ and ‘wrong’

Meta-ethics is concerned with analysis of the language people use when they discuss a moral issue, e.g. the meaning of the words ‘right’ and ‘wrong’

Normative ethics is concerned with how things ought to be, how people should behave and how people justify decisions when faced with situations of moral choice. It attempts to generate the norms or standards of the right action.

Normative ethics is concerned with how things ought to be, how people should behave and how people justify decisions when faced with situations of moral choice. It attempts to generate the norms or standards of the right action.

Descriptive ethics is about facts while normative ethics is about values. One cannot argue from the one to the other. The way things are is not necessarily a guide to how they should be.

Ethical theories

Ethical theories provide a framework within which the acceptability of actions and the morality of judgements can be assessed. Absolutist theories rest on the assumption that there is an absolute right or wrong. Relativistic or reason-based theories rest on the assumption that right or wrong can depend purely on what any society, group or individual believes.

Normative theories of ethics

Normative theories are distinguished by the way in which they provide ethical guidance:

Virtue ethics locate the highest moral value in the development of persons

Virtue ethics locate the highest moral value in the development of persons

Consequentialist (or utilitarian) theories evaluate actions by reference to their outcomes

Consequentialist (or utilitarian) theories evaluate actions by reference to their outcomes

Deontological theories hold that actions are intrinsically right or wrong.

Deontological theories hold that actions are intrinsically right or wrong.

These are summarized in Table 7.1.

Virtue ethics

The word ethics is derived from the Greek ethos, meaning a person’s character, nature or disposition. Virtue ethics has its roots in the work of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, and places emphasis on the character of the person performing the action rather than on the action itself.

Virtue ethicists stress the importance of inner character traits such as honesty, courage, faithfulness, trustworthiness and integrity. Healthcare professionals are expected to demonstrate such characteristics or virtues.

Socrates (470–399 bc) taught the priority of personal integrity in terms of a person’s duty to himself.

Plato (427–347 bc) emphasized four cardinal virtues: wisdom, courage, temperance and justice. Others virtues were fortitude, generosity, self-respect, good temper and sincerity. Hierarchies of virtues have changed over time.

Aristotle (384–322 bc) was concerned with what makes a good person rather than what makes a good action. He believed that being moral involved rationally applying good sense to find the middle way between one extreme and another, for example courage is the mean between cowardice and rashness (Box 7.1).

Modern Aristotelians believe that ethics should be concentrating more on how people should live their lives, advising which ethical characteristics people should try to develop and habituating people into having good dispositions so that moral behaviour becomes almost instinctive.

Consequentialism and utilitarianism

For consequentialists, whether an action is morally right or wrong, depends on the action’s ‘utility’ or usefulness.

Utilitarians consider that an action should be judged according to the results it achieves. Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) argued that actions are right if they maximize pleasure (good) and minimize pain (evil) for the majority of people. Since he believed everyone had an equal right to pleasure, everyone counted in the assessment of benefits of an action.

Later it was argued that not all forms of pleasure and happiness were equal and other values such as duty, love and respect should be considered. The goal of ethics is not only the pleasure (happiness) of the individual, but also the greatest pleasure (happiness) for the greatest number (John Stuart Mill 1806–1873).

Recent utilitarian theorists have advocated taking into account the preferences of persons concerned. This approach has become widely used in areas of applied and professional ethics and assumes that there should be equal consideration of interests. While accepting that not all have equal interests (animals compared with humans for example), all should be treated in a way that is appropriate.

The simplicity and practical usefulness of utilitarianism is one of its main benefits. If an act is likely to produce the greatest good for the greatest number, then it is right – if it does not, it is wrong.

Deontology

Deontology refers to a group of normative ethical theories that emphasize moral duties and rules. They are referred to as non-consequentialist, since some actions are inherently right or wrong, regardless of consequences. There are acts we have the duty to perform because these acts are good in themselves; and we have a duty to refrain from acts that are intrinsically bad or wrong.

Kantianism

Kantianism is the most comprehensive deontological ethical theory named after Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). He believed that people, not God, imposed morality because they were rational beings. Kant suggested that moral duty could be determined by the use of reason about the act in question. This categorical imperative exists as several versions, the two best known being:

First version: ‘Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law’

First version: ‘Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law’

This means that ‘unless you are able to say that everyone must act like this, then you should not act like it’. Something is morally right, or wrong, only if it applies for everyone. It would be inconsistent and irrational to decide, for example, that you could steal from others, but they could not steal from you. Thus, reason demands that we do not steal unless everyone is allowed to steal.

Second version: ‘Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end’

Second version: ‘Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end’

People must be treated as ends in themselves and not as a means to an end. This means that all people are equal and deserve equal respect. There are certain ways we must not treat people, no matter how much usefulness might be produced by treating them in those ways (e.g. not lying to a patient). A consequentialist, by contrast, does not believe it is wrong to use people as means – if the ends justify the means, lying is permissible.

This second version has been very influential in medical ethics, as it can be translated as saying it is necessary to treat people as autonomous agents capable of making their own decisions. The concept of autonomy and respecting an autonomous decision demonstrates respect for the person as an ‘end in itself’.

Ross’s prima facie duties

WD Ross (1877–1971) recognized that a number of obligations present themselves in practical situations and that we must weigh up the various options available when deciding which course of action is morally correct (Hawley 2007). Ross distinguished duties as prima facie or ‘actual’ duties. A prima facie duty is one that is always to be performed unless it conflicts with an equal or stronger duty. The stronger duty becomes an actual duty that must be carried out for the action to be morally correct. The prima facie duty to keep a promise, for example, could be over-ridden if it was not in a person’s best interests. Ross identified seven prima facie duties (see Box 7.2).

Conflict of duties can only be resolved by considered judgement in a particular situation: there is no general ranking of the duties. The morally correct action is the one that produces the greatest balance of prima facie rightness to prima facie wrongness. However, the principle of non-maleficence is considered to take precedence over the principle of beneficence when they come into conflict. Ross’s theory has greatly influenced the ‘four-principles’ approach to medical ethics (see below), as it introduced the idea of sorting and weighing principles.

Deontology and rights

The rights of persons are closely associated with duty. Using someone as a means to an end infringes that person’s ‘rights’, such as rights to freedom and choice. This ‘right’ could be derived from the capacity to reason or to make choices, so that healthcare professionals, for example, are obliged to respect rational wishes of patients.

In every case, the deontological norm has boundaries. What lies outside those boundaries is not forbidden. Thus, lying is wrong while withholding a truth may be perfectly permissible. This is because withholding a truth is not lying. If more than one option is morally acceptable, the individual can choose which to carry out. By contrast, a consequentialist must always select the best option.

Principlism and the four ethical principles

‘Principlism’, introduced in the late 1970s, is now a widely applied bioethical framework for identifying key moral issues and as a starting point for looking at ethical dilemmas. It identifies four prima facie moral commitments relevant in health care and compatible with the major ethical theories. These enable a simple, accessible approach when the ethical theories themselves can be considered to be too general to guide particular decisions. Being conditional, the principles allow a stronger case to overrule a weaker one in a particular circumstance.

These are supplemented with four ‘rules’:

Autonomy

Autonomy encompasses the capacity to think, decide and act freely and independently. Respect for autonomy flows from the recognition that all rational beings have unconditional worth, and each has the capacity to determine his or her own destiny. People should be seen as ends in themselves and not treated simply as means to the ends of others.

Autonomy generally brings about the best outcome. Individuals should be allowed to develop their potential according to their own personal convictions provided these do not interfere with a like expression of freedom by others. A person’s autonomy should be respected unless it causes harm to others. Liberty should not be limited on the sole grounds that a person’s choice would harm them – competent adults should be free to risk their own health and well-being without interference. Respectfulness can be considered a characteristic of a virtuous person.

Three types of autonomy have been suggested:

Autonomy of thought: thinking for oneself, making decisions, believing things, making moral assessments

Autonomy of thought: thinking for oneself, making decisions, believing things, making moral assessments

Autonomy of will (intention): freedom to do things on the basis of one’s deliberations

Autonomy of will (intention): freedom to do things on the basis of one’s deliberations

Autonomy is perhaps the dominant principle of medical ethics. Autonomy is the basis of informed consent and truthfulness, privacy and confidentiality. Other proposed ‘principles’ such as fidelity (faithfulness) and veracity (truthfulness) can be considered to come under the umbrella of autonomy. Autonomy means that patients can choose what type of treatment they would prefer given a choice, and even choose not to be treated. Autonomy also involves helping the patient to come to his or her own decision. Where a patient is able to make an informed decision, this should be respected, even when it appears to be detrimental, illogical or immoral. However, healthcare providers must also be able to recognize situations where a patient is unable to act autonomously. Of course, a person may even make an autonomous decision to leave decision-making to someone else.

Autonomy and patient preferences or wishes are not absolute and must be weighed against competing liberties and interests. The opposite of autonomy is paternalism. Paternalism over-rides the principle of respect for autonomy and involves making decisions on behalf of another, usually justified by appealing to the principle of beneficence (the duty to do good) or non-maleficence (the duty not to harm). In the past, paternalistic practise was common, but in modern society, it is less acceptable, although weak (soft) paternalism can be justified in some cases, such as when acting in the best interests of an incompetent patient. However, strong (hard) paternalism, ignoring or over-riding a competent person’s wishes, is difficult to justify.

Non-maleficence

Non-maleficence means not doing harm, often expressed as ‘First, do no harm’ – a simplification from the Greek fourth century bc Hippocratic Oath.

Non-maleficence requires healthcare providers to do everything in their ability to avoid causing, and where possible actively avoid causing, either intentional or unintentional harm. This would include maintenance of competence through continuing education, always acting within the scope of practice and individual ability and doing everything to avoid making mistakes that can harm the patient. Healthcare providers have an ethical (if not legal) obligation to report behaviours by others that adversely (or could adversely) affect the health, safety or welfare of patients – an obligation to report others who are incompetent, impaired (such as from fatigue, alcohol, drugs or mental illness) or are unethical.

Beneficence

Beneficence is an obligation to do good. To benefit the patient is a fundamental goal of health care. Most people enter a healthcare profession because of the opportunity to help others and each profession will have its own definition of what ‘good’ means.

Beneficence and non-maleficence are often seen as two sides of the same coin. However, while there is a general positive obligation not to do harm, providing benefit (typically to a specific individual) is not always possible.

Desire to help others can come into conflict with the principle of autonomy, as when a patient chooses a course of action that does not appear to coincide with his or her best interest. Beneficence also frequently comes into conflict with non-maleficence. Most medical and therapeutic interventions are associated with some harm (e.g. the pain associated with immunization) and benefits have to be balanced against risks. In such instances, we rely on beneficence to ensure that any harm is performed for a greater good.

Beneficence involves doing what is best for the patient. This does raise the question of who should judge what is best. Conflicts between beneficence and autonomy can occur when a competent patient chooses a course of action that the healthcare professional does not consider is in his or her best interests.

Justice

Justice is often synonymous with fairness and equity: a moral obligation to act on the basis of fair adjudication between competing claims. All people of equal need are entitled to be treated equally in the distribution of benefits and burdens regardless of race, gender, religion and socioeconomic status, etc. Justice requires that only morally defensible differences among people be used to decide who gets what. Decisions should not be based on capricious or illogical reasons. The logical opposite of justice is discrimination.

Various factors can be used as criteria for the distribution of various resources (after Beauchamp and Childress 2001), e.g. to each:

Justice is about equal access to health care. Not all patients have an equal need and it is not always possible to provide the same level of care to all patients at all times. Consequently, a system has to be established to provide care as fairly as possible. For example, in emergency departments, a system of triage is applied in which the most critical patients are treated first on the basis of clinical need.

The four rules

Beauchamp and Childress (2001) analysed veracity, privacy, confidentiality and fidelity in the context of the professional–patient relationship.

Veracity

Veracity is the obligation to tell the truth and is an essential component of informed consent and hence, respect for autonomy. It is also closely linked to obligations of fidelity, trust and promise keeping. Veracity is not limited to cases of informed consent. Veracity provides for open and meaningful communication that is an absolute necessity in any moral relationship between two persons. The relationship between healthcare professional and patient needs to be based on mutual trust and honesty.

To Beauchamp and Childress, veracity is prima facie binding. It is not absolute, and non-disclosure, deceiving and lying could be justified when veracity conflicts with other principles such as non-maleficence. Non-disclosure or benevolent deception, but not involving lying, would be more easily justified, as it is less likely to threaten the relationship of trust.

With the complexity and uncertainties of modern medicine, complete honesty and ‘whole truth’ can be an oversimplification. Just what the truth is can be a matter of clinical judgement. Issues concerning how much information should be given, to whom and in what circumstances, create continuing difficulties for healthcare professionals. The obligation of veracity often conflicts with obligations of confidentiality and privacy.

Whistle-blowing, calling the attention of authorities to unethical, illegal or incompetent actions of others, is based on the ethical principles of non-maleficence and veracity.

Privacy

An obligation to respect privacy can be seen to come under the ethical principle of respect for a person’s autonomy. Privacy relates to a right to restrict access to what a person regards as private and personal and not to be invaded. Beauchamp and Childress (2001) consider privacy to include decisions about sharing or withholding information about one’s body or mind, one’s thoughts, beliefs and feelings.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality relates to the duty to maintain confidence and thereby respect privacy. Beauchamp and Childress (2001) define privacy as allowing individuals to limit access to information about themselves and confidentiality as allowing individuals to control access to information they have shared.

Fidelity

Fidelity is the obligation of faithfulness and is concerned with acting in good faith, keeping promises, fulfilling agreements, integrity and honesty. Among the duties of fidelity is the duty of loyalty and an obligation to put the patient’s interest first. Issues can arise when there are conflicts of interest or divided loyalties.

Principlist ethics and research

Principlist ethics have dominated the field of health research. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioural Research, in the Belmont Report of 1979, identified three basic ethical principles (the so-called Belmont principles):

Respect for persons incorporated two ethical convictions: that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents; and that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection.

Beneficence required that persons be treated in an ethical manner and their decisions respected and protected from harm. It incorporated the concept of non-maleficence by maximizing possible benefits and minimizing possible harms.

Justice required fairness in distribution of benefits and burdens associated with research and subject selection.

Morals and law

Both laws and morals can be considered to be guidelines for conduct. Laws establish minimum standards of behaviour that everyone must meet. The law is influenced by moral and ethical principles but they do not necessarily match. Laws may not necessarily be ethical and many things that are not illegal may still be wrong. Morality is a system of right and wrong enforced through societal pressure. Morals tend to be simple and general rather than precisely defined. They provide general rules that should be applied in particular instances according to circumstances and an individual’s conscience. In general, morals correspond to what is done in a society and accord with customs and traditions. Personal morals relate to the values and beliefs that provide the framework for an individual’s decisions and actions. Ethics lies somewhat between law and morality. Ethical standards need to be precisely defined but are subject to individual interpretation. Ethics seeks ideal or maximal standards of behaviour.

All law has some moral basis, and in medicine, law, morality and ethics are inextricably linked. Many acts of parliament associated with health care are far from ethically neutral. There are many areas – research on embryos and embryonic stem cells for example – that are a source of deep moral divisions. Sometimes the law acts almost in a knee-jerk fashion, responding to society’s moral disquiet, e.g. the Surrogacy Arrangements Act 1990, prohibiting commercialization of surrogacy; and the Human Reproductive Cloning Act 2001, prohibiting the planting of cloned embryos in a womb, were both rushed through parliament. Medical science and technology are continuously advancing and at a pace. Situations are having to be addressed before society has had time to thoroughly think them through.

Applied and professional ethics

Applied ethics is the branch of ethics that is concerned with the analysis of specific, controversial issues, arising in specific cases. It uses ethical theories and principles to form judgements. Applied ethics covers a number of areas including business ethics, environmental ethics and bioethics. Bioethics, a contraction of biomedical ethics, is concerned with the interface between the life sciences and ethics. It encompasses medical or healthcare ethics and focuses on issues that arise in healthcare or clinical settings. Professional ethics includes group standards and norms as well as individual ethics.

Ethical issues in health care

Advances and changes in health care and medical technology, the changing relationship between professional and patient and the changing interprofessional roles and their relationships all require an increased ethical awareness in healthcare professionals (see Ch. 15). Healthcare professionals need to be able to answer ethical questions, work out solutions to ethical problems and resolve ethical dilemmas. Some current issues such as medical research and resource allocation (rationing) appear to reflect a more utilitarian approach to ethics. Issues surrounding the beginning and end of life, cloning and reproductive technologies, and genetic testing clearly do not evoke utilitarian principles alone. In a pluralistic society, there are many different and strongly held moral viewpoints (moral pluralism) which apply to medicine, as is clearly demonstrated with issues such as abortion and euthanasia.

One area, for example, where significant challenges in ethics are likely to occur, is in relation to death and dying. The issue of euthanasia encompasses a number of concepts used in moral discussion, such as autonomy, the sanctity of life, quality of life, medical futility, best interests, acts and omissions, double effect and slippery slopes.

The doctrine of double effect embraces two effects, an intended good effect and an unintended secondary bad effect. This justifies giving pain-relief treatment to terminally ill patients, provided it is given with the primary intention of relieving pain, and excuses any unavoidable, but unwanted, life-shortening effect of doing so. The central core of the doctrine is the moral distinction between intention and foresight.

The moral distinction between passive and active euthanasia rests largely on the distinction between acts and omissions. To actively end life is both morally and legally wrong, whereas to withhold life-saving treatment could, in some circumstances, be seen as the right thing.

The slippery slope argument is one used against the practice of voluntary euthanasia. The sanctioning of some mildly objectionable practice inevitably leads to some highly objectionable practice. Thus, by permitting voluntary euthanasia this will lead down a slippery slope to involuntary active euthanasia.

Ethics and pharmacy

There are legal, ethical and professional implications to every decision and action taken by a pharmacist (see Ch. 8). While dramatic ethical dilemmas may not be the norm of everyday practice, each encounter with a patient raises ethical issues. Most do not present a dilemma. A dilemma arises from fundamental conflicts among beliefs, duties and principles. An expanded role and increased patient contact increases the opportunity for ethical issues to arise. Pharmacists need to become more comfortable with decision making in conditions of uncertainty. Ethics in practice involves such varied issues as pharmacist–patient relationships, empathy, responsibility and accountability, privacy and confidentiality issues, compliance and adherence, responding to errors, maintaining competence, supply of emergency contraception, abuse of over the counter medicines, supply of homoeopathic medicines, supply of unlicenced medicines, etc. (see Chs 5, 9, 15, 18, 21, 48, 50).

Ethical dilemmas are not restricted to clinical issues. Studies have reported a willingness of students to engage in some sort of academic dishonesty. This demonstrates the importance of nurturing and enhancing ethical behaviour in students and helping them to find their ‘moral compasses’. Dilemmas may also arise in areas of practice, for example areas of possible conflict of interest, areas concerning NHS fees and remuneration (e.g. dispensing a prescription item at a loss), as well as personal behaviour, whistle-blowing and research, etc.

Professional ethics and law

Laws can be considered an empowering force in healthcare ethics. They define the legal aspects of practice, rights of patients and duties of healthcare professionals. Negligence involves a failure to meet obligations to others and, by attributing fault or blame, clearly has a moral dimension. Standards of care have a moral as well as legal and professional dimension. However, the law is seen as setting minimum standards, while the others aim for the maximum.

Professional ethics are concerned with the principles of professional conduct concerning the rights and duties of the profession and the professional person himself or herself.

Professional codes and oaths

Professional ethics are concerned with professional values and philosophies. Health professions articulate their profession’s values and standards of conduct, and the rights and responsibilities of their members in an ethical code. Codes exist to encourage optimal behaviour and promote a sense of community between members. While codes tend to emphasize duties and responsibilities (deontologically based), a feature of many is their aspirational nature – they strive for upper ideals. They make explicit, to both members and the public, the expectations and ideals central to the profession and so help ensure public trust and confidence in professional practice. Law and professional guidelines alone are unlikely to be an effective way of maintaining professional competence and behaviour. Standards of care are as much about ethics as they are about skills.

Various oaths and codes exist in health care (e.g. the Hippocratic Oath), their content having evolved (Box 7.3). Reference to autonomy and justice, as well as the obligation and virtue or veracity, has traditionally been ignored in medical codes and pharmacy codes.

Both law and ethics influence the formulation of the code of ethics and, more recently, so do the ethical principles: respect for people is related to autonomy, competence to non-maleficence and integrity to fidelity. The Standards of conduct, ethics and performance, published by GPhC, now adopts a principled approach, identifying ethical principles and including inherent value attitudes and behaviours that characterize a good pharmacist. The code is intended to promote professional judgement and support professional discretion.

Health care requires a multidisciplinary approach and healthcare professionals can be expected to share some common ethical rules. A shared code of ethics has been advocated and principles identified based on the Tavistock principles (Berwick et al. 2001) (see Box 7.4).

There has been a resurgence of interest in medical oaths in recent years (and such a personal professional pledge has been advocated in pharmacy). This could take the form of a personal affirmation encompassing the four ethical principles, some of the virtues such as integrity, honesty, compassion and other key obligations concerned with working practice such as confidentiality and consent. Such pledges (or oaths) are used in some schools of pharmacy.

Ethical decision-making

In making ethical decisions, healthcare professionals can refer to law, professional codes and guidelines and to the principles and theories of ethics. Common sense, beliefs and values, intuition and experience also all play a role in influencing the decision. The first step in the process is to recognize that an ethical issue is involved and it is not purely a matter of law or professional etiquette. Ethical issues arise when there is confusion about competing alternatives for action, when interests compete and when none of the alternatives is entirely satisfactory. It typically prompts the question: ‘What should I do?’ or ‘What ought I to do?’ This requires a moral awareness or sensitivity. The next stage requires critical thinking and an ability to make ethical judgements. Typically this benefits from following a structured approach such as:

Obtaining knowledge of all the pertinent facts

Obtaining knowledge of all the pertinent facts

Identifying the specific ethical issue(s)

Identifying the specific ethical issue(s)

Framing these issues in the context of ethical theories and principles

Framing these issues in the context of ethical theories and principles

Considering – weighing up all available information in order to identify options

Considering – weighing up all available information in order to identify options

Wingfield and Badcott (2007) have set out in detail a methodology for ethical decision-making, based on a four-stage approach:

Gathering relevant facts includes ascertaining what law (criminal, civil, NHS) applies and what guidance (codes and guidelines) is available. The second stage is identifying all the individual parties involved and attempting to balance their disparate interests. The third stage involves asking the question ‘What COULD I do in this situation?’ and the final stage, asking the question ‘What SHOULD I do in this situation?’ – recognizing that decisions may have to be justified. Finally, so as to develop decision-making skills, professional judgement and practice experience, once the decision has been made and any consequences realized, reflection is required.

When applying ethical principles, the principles involved should be identified, asking whether any of these are in competition, and whether one principle should take priority over another. The ethically correct option is typically one that fulfils the most principles. There may not always be right and wrong answers to situations, but there are better and worse ways of dealing with them. The better way would be to analyse an ethical problem by following a structured framework that enables the theories and principles to be critically reviewed and applied.

The importance of reflection cannot be emphasized enough. Most people make decisions at great speed and with little reflection. Experienced pharmacists often do not recognize the processes they use when making difficult choices. By slowing down the process, and breaking it up into stages and steps, it is possible to analyse how decisions were reached. An analysis of what was done, and why, can prove helpful the next time a situation presents with a difficult decision to make.

The virtuous pharmacist

Ethical principles do not in themselves solve ethical dilemmas but merely act as starting points to help identify the issues and concerns. Principles need to be supplemented with compassion, empathy and common sense.

At its simplest, the ethical principles become merely a checklist. Beauchamp and Childress (2001) were keen to assert that the principles-based approach was not designed to provide simple solutions to complex ethical dilemmas:

Principles do not provide precise or specific guidelines for every conceivable set of circumstances. Principles require judgment, which in turn depends on the character, moral discernment, and a person’s sense of responsibility and accountability … Often what counts most in the moral life is not consistent adherence to principles and rules, but reliable character, moral good sense, and emotional responsiveness.

(Beauchamp and Childress 2001: 462)

The four focal virtues

One or two virtuous traits do not amount to a virtuous person. A virtuous professional requires a virtuous character. To that end, they identified four focal virtues:

Compassion: ‘regard for the welfare of others. It combines an attitude of active regard for another’s welfare with an imaginative awareness and emotional response of deep sympathy and discomfort at the other person’s misfortune or suffering’

Compassion: ‘regard for the welfare of others. It combines an attitude of active regard for another’s welfare with an imaginative awareness and emotional response of deep sympathy and discomfort at the other person’s misfortune or suffering’

Discernment: ‘includes the ability to make judgements and reach decisions without being unduly influenced by extraneous considerations, fears, or personal attachments’

Discernment: ‘includes the ability to make judgements and reach decisions without being unduly influenced by extraneous considerations, fears, or personal attachments’

Trustworthiness: ‘Trust is a confident belief in and reliance upon the ability and moral character of another person’

Trustworthiness: ‘Trust is a confident belief in and reliance upon the ability and moral character of another person’

Integrity: ‘means soundness, reliability, wholeness, and integration of moral character … [it] means fidelity in adherence to moral norms’.

Integrity: ‘means soundness, reliability, wholeness, and integration of moral character … [it] means fidelity in adherence to moral norms’.

Mapping of values associated with pharmacy (Benson 2006; Benson et al. 2007; BMA 1995) have been undertaken in recent years and have identified some of the basic and ancient virtues.

Being a professional is concerned with personal development and striving for professional and moral excellence. In response to the question, ‘What is a good doctor?’, Tonks (2002) identified the following qualities:

The education of a healthcare professional is more than the acquisition of knowledge and skills. There is the need to learn professional behaviour and to acquire a new identity – a professional identity. From entering a professional programme, professionalism, the development of character traits and behaviours associated with professionalism, and the development of a commitment to ethical principles must be nurtured. This process continues throughout professional life.

Conclusion

Why is ethics important and why do healthcare professionals need to study ethics? Because it helps us to consider different perspectives, to respect others and the different needs of others. It helps us to take note of a patient’s wishes. It helps personal and professional development. Autonomous professionals are required to make judgements and take decisions and it helps us to analyse these actions and their consequences.

Healthcare professionals have a responsibility to work ethically and personal standards, competence and high ethical standards are essential. Individual reflection on personal standards and ethics is vital. Excellence is not a state but a journey. It requires constant effort and never quite reaching the final destination. Aristotle recognized that it was not easy to be virtuous – otherwise we would not praise it.

Key Points

Ethics is associated with choices, judgements and decisions, encompassing concepts such as right and wrong, values, duty and obligation. Importantly, ethics is critically reflective and analytical

Ethics is associated with choices, judgements and decisions, encompassing concepts such as right and wrong, values, duty and obligation. Importantly, ethics is critically reflective and analytical

Three main ethical theories inform biomedical ethics: utilitarianism, deontology and virtue theory

Three main ethical theories inform biomedical ethics: utilitarianism, deontology and virtue theory

Utilitarianism is the most prominent consequentialist theory and actions are judged by their usefulness

Utilitarianism is the most prominent consequentialist theory and actions are judged by their usefulness

Deontology emphasizes duty and motives

Deontology emphasizes duty and motives

Virtue theory stresses the importance of the actor’s character

Virtue theory stresses the importance of the actor’s character

The four key ethical principles in medical ethics are autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justice

The four key ethical principles in medical ethics are autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justice

Ethical principles serve as a stimulus to identify ethical conflicts and aid decision-making

Ethical principles serve as a stimulus to identify ethical conflicts and aid decision-making

A coherent and consistent approach to ethical decision making is needed and requires critical analysis and reflective thinking

A coherent and consistent approach to ethical decision making is needed and requires critical analysis and reflective thinking