Concordance

What is meant and understood by the term ‘concordance’

What is meant and understood by the term ‘concordance’

How concordance differs from compliance and adherence

How concordance differs from compliance and adherence

The concordance model and the relationship with patients

The concordance model and the relationship with patients

The need for good communication skills in developing a concordant relationship

The need for good communication skills in developing a concordant relationship

Introduction

‘Mrs Jones is being a non-concordant patient [sigh] again’. Or is she? Concordance offers a way forward when we, as pharmacists, notice that patients are not taking their medicines as prescribed. Yet concordance can fundamentally challenge our assumptions about the role of patients in a professional–patient interaction. It states that patients have a legitimate and valuable perspective on taking their medicines and that healthcare professionals should encourage patients, should they wish it, to become involved in decisions about their treatment. For these reasons, concordance is about a consultation process and not individual patient behaviour. Mrs Jones cannot be non-concordant on her own: it takes at least two, professional and patient, to have a non-concordant (or successfully concordant) encounter. The consultation could have been non-concordant but Mrs Jones, on her own, cannot have been. Mrs Jones can be non-compliant or non-adherent with her medicine but these have a distinctly different meaning from concordance.

What is concordance?

Concordance occurs when ‘the patient and the healthcare professional participate as partners to reach an agreement on when, how and why to use medicines, drawing on the expertise of the healthcare professional, as well as the experiences, beliefs and wishes of the patient’ (Marinker et al. 1997). It arose from the recognition that throughout the decades of research investigating interventions to help patients follow prescriptions for medications, there was still a high level of non-adherence. In a review by Haynes et al. (2001), interventions that used a combination of approaches in helping patients take their medicines, such as providing more convenient care, giving patients more information, providing reminders or offering medicine counselling, did not lead to large improvements in adherence rates. From this synthesis of research findings, there was a call to investigate more innovative approaches to assist patients with taking their medicines. Concordance is one such innovative approach.

This is not to say that terms like adherence and compliance can no longer be used. When referring to the extent to which patients take medicines as prescribed by their doctor or other healthcare professional, the words ‘adherence’ and ‘compliance’ are appropriate terms to be used. As a concept distinct from compliance or adherence, concordance may affect adherence although it is mainly concerned with improving the quality of health care through a shared understanding between professional and patient on treatment choices. Yet there are difficulties with words like adherence and compliance, which have overtones of the patient being disobedient or ‘naughty’ in not following the doctor’s instructions. Conceptually, terms like ‘compliance’ and ‘adherence’ reinforce a paternalistic doctor-knows-best model of health care and implicitly devalue the views and experience of patients as users of medicines. Concordance seeks to redress this balance by acknowledging that patients and customers have a key role in the decision-making of whether or not to take their medicine.

The term adherence has been usefully split into those who are intentionally non-adherent and those who are unintentionally non-adherent. Unintentionally non-adherent patients are those who do not take their medicine because of a number of reasons, e.g. because they are unable to read the label due to poor eyesight, or forgot to take a tablet because a medicine regimen is complex and difficult to remember. Appropriate solutions to unintentional non-adherence are big print labels, improved medicines information, simplified medicine regimens or adherence aids, such as a Dosette box. Intentional non-adherence is where concordance can play a role; previous research has suggested that patients make reasoned decisions about whether or not to take their medicines. Patients may alter their medicine-taking behaviour for a number of reasons, e.g.:

They have experienced side-effects

They have experienced side-effects

Taking medicines interferes with their daily lives

Taking medicines interferes with their daily lives

They have beliefs about the medicines or illness which conflict with medicine taking

They have beliefs about the medicines or illness which conflict with medicine taking

They are adjusting the medicine dose in response to symptoms.

They are adjusting the medicine dose in response to symptoms.

Concordance has been called a partnership in medicine taking and has three important ingredients: (1) includes an explicit agreement between two people; (2) is based upon respect for each other’s beliefs; and (3) gives the patient’s view priority although they may choose to have the professional make all the decisions about treatment. This third ingredient recognizes that once the patient leaves the encounter with the healthcare professional, they will ultimately have the casting vote to decide whether or not to take that medicine.

Ethical considerations

The need to involve patients in decisions about their care is enshrined in ‘principle 4’ of the Standards of conduct, ethics and performance by the GPhC. This principle draws upon healthcare professionals’ duty to obtain informed consent when initiating new medicines and the ethical principle of respect for patient autonomy. This recognizes that patients should be allowed to have control over their own lives and make decisions that affect their lives. In common with the concordance initiative, this principle advocates working in partnership with patients, to explain the options available and to help patients make informed decisions about different treatment options.

The concordance model

Concordance shares many characteristics with other models and themes currently prevalent in health care, most importantly those of shared decision-making and patient-centredness. There is a greater chance of a successfully concordant encounter when each participant knows what the other is thinking. For this reason, concordance shares many characteristics with shared decision-making, where both the doctor and patient share information with each other, when both take steps to participate in the decision-making process by expressing treatment preferences and they jointly agree on the treatment to implement. Shared decision-making may be considered part of the wider concept of patient-centredness. Patient-centredness has three themes: eliciting the patient’s perspectives and understanding them within a psychosocial context; reaching a shared understanding of the patient’s problem and treatment; and involving patients, to the extent they wish to be involved, in choices about their care. It is not a coincidence that the concept of concordance arose during the same time period that patient-centred care became dominant in healthcare policy. Concordance can be seen as part of the wider patient-centred political context but one which specifically focuses on medicine- taking behaviour. NICE has similarly produced guidance on medicines adherence which draws upon many of the themes relevant to concordance.

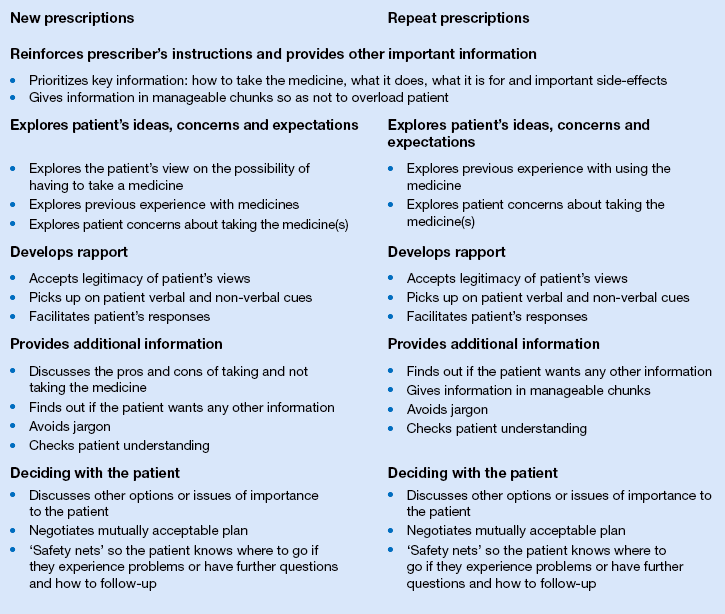

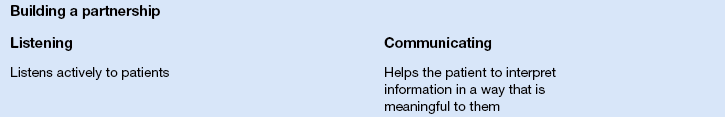

Concordance shares many features with the formative communication teaching guides, the Calgary–Cambridge guides as discussed in Chapter 17. Although designed as a formative aid in teaching medical students communication skills, the Calgary–Cambridge guides have a consultation structure which is readily adaptable to the pharmacy setting. These guides assume a chronology to the consultation with distinct sections on initiating the consultation, gathering information, providing structure to the consultation, building a relationship, explanation and planning and closing the consultation. The Calgary–Cambridge guide has been adapted to reflect two common pharmacy consultation situations of (1) handing out a new prescription and (2) issuing a repeat prescription, as shown in Box 18.1. Sample phrases or ‘catchphrases’ useful in conducting a concordant consultation in pharmacy are shown in Box 18.2.

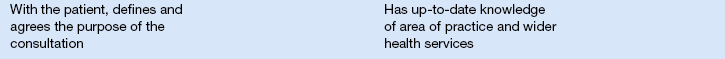

The Medicines Partnership at NICE has developed a competency framework for shared decision-making with patients, describing the skills and behaviours professionals need to reach a shared agreement about treatment. In this document, shared decision-making and concordance are used synonymously, highlighting the common approach underpinning these concepts. These eight competencies are shown in Box 18.3.

The evidence for concordance

Already presented has been the Haynes Cochrane review regarding the use of interventions to help patients take their medicines; that current methods of improving adherence are complex and not very effective. Much of the information available about concordance relates to the doctor–patient consultation. As shown in Box 18.1, the concordant approach can be readily adapted to the pharmacy situation after a prescribing decision has been made. Examples are handing out new or repeat prescriptions, in repeat dispensing or in conducting a medicines use review. Yet pharmacists also have a role before treatment decisions about medicines are made: when giving over-the-counter advice or as pharmacist independent prescribers. The next sections will look at this evidence, drawing upon pharmacy literature where possible, as well as evidence from medicine. Medical literature may appear to be relevant only in the latter situation, i.e. before prescribing decisions are made. However, the evidence has resonance for the range of pharmacy consultations, both before and after treatment decisions have been made. These are grouped under four headings: eliciting the patient’s view; developing rapport with the patient; providing information; and the therapeutic alliance.

Eliciting the patient’s view

Previous research tells us that patients have beliefs about their medicines and illness, and that these beliefs can affect their medicine-taking behaviour. For example, individual patients will vary in their confidence in the medicine to help them. They may have doubts about a medicine and ‘test’ whether the medicine is having an effect by stopping it on occasions. Patients may believe that they will become ‘immune’ or addicted to a medicine if they take it long term. These beliefs can occur, even when we know these medicines are not associated with a true pharmacological dependence. Many people consider prescribed or over-the-counter medicines, particularly in comparison with herbal or homoeopathic products, to be unnatural, artificial and potentially harmful to their bodies. They might see themselves as being ‘anti-drugs’ people, where doing without a medicine is the preferred course of action, only resorting to medicine taking when it is absolutely necessary. Evidence also suggests that patients make complex judgements about their medicines, weighing up the benefits and drawbacks of taking a medicine within their individual patient experience. All of these patient beliefs have their own rationality when viewed from the patient’s perspective of taking medicines within the context of their everyday life.

Research on doctor–patient consultations suggests that these beliefs are important because, if not elicited, they can lead to misunderstandings in consultations when prescribing decisions are made. Misunderstandings in consultations can be caused by non-disclosure of information from either the doctor or the patient, disagreement about causes of side-effects or failure of communication about a decision reached by the doctor. Misunderstandings arise when patients do not play an active role in the consultation by stating their views and beliefs about the medicine or illness under discussion. The consequence of consultation misunderstandings can be non-adherence to prescribed medication. While research has primarily focused on doctor–patient consultations, it can be hypothesized that eliciting the patient’s views and beliefs on their medicine and medicine-taking behaviour is equally important in pharmacist–patient or pharmacist–customer interactions as well. However, this is an area pharmacists find particularly difficult to incorporate into their practice. Healthtalkonline is a website which gives videoclips of patients’ experiences of health-related conditions and experiences. These videoclips may be useful when professionals want to gain insight into what it is like from a patient’s perspective to experience an illness or face a specific health-related decision.

Developing rapport with the patient

Concordance is focused on a consultation process and, as such, is primarily concerned with professional– patient communication. Although we all tend to think of ourselves as good communicators, to participate in a concordant consultation is actually very difficult. If it seems easy, you are probably not doing it right! All of the ‘generic’ communication skills such as active listening, avoiding jargon, giving information ‘in chunks’ or a little bit at a time, using open questions, appropriate body language, encouraging the patient to ask questions, treating the patient as an equal and being non-judgemental are important. Checking patients’ understanding and giving them explicit opportunities to ask questions are areas pharmacists find particularly difficult to include in their consultations. Other skills, such as presenting information in a way the patient is able to understand, without being patronizing, are essential. Both people in the consultation need to explore each other’s viewpoint and confirm that they understand where the other person is coming from. While a patient may spontaneously volunteer their personal beliefs or views, if they do not, it is down to the skill of the professional to elicit the patient’s view and ensure that the patient feels comfortable enough to discuss this information.

Empathy plays a key part in concordance. Empathy is distinct from sympathy. Empathy involves fully understanding an individual’s emotions, while sympathy is simultaneously being affected by another’s emotions. In interactions with patients, empathy allows for recognition and acknowledgement of the patient perspective. Professionals display their acceptance of the legitimacy of the patient’s view by communicating their understanding of the patient’s situation. Included within this are expressions of concern, a general willingness to help and an acknowledgement of the efforts the patient may have made thus far in terms of trying to manage their medicines and illness. It requires the professional to be able to deal sensitively with potentially embarrassing or unpleasant issues.

In a concordant consultation, it can be useful to overtly draw attention to the structure of the interaction and signpost when a different issue or change of subject will take place. This includes providing information in a logical sequence but may also consist of statements such as ‘I would now like to move on to discussing potential options, is that okay with you?’ or ‘There are three ways in which this medicine can help you. First, …’ or ‘I’d now just like to summarize some of the things we’ve discussed’. Summarizing information at various points in the interaction, asking if the patient has any questions, as well as ‘safety netting’ – identifying appropriate follow-up or what to do if something changes or further questions arise – are important.

Providing information

Studies over the years have consistently shown that patients want information about their medicines (see Ch. 25). When patients are asked what they would like to know, they frequently respond that they want to know about side-effects, what the medication does, any lifestyle changes they might need to undertake and how to take the medication. Surveys support the view that, while most patients have considerable confidence in their medicines, 30% also have concerns, particularly with regard to side-effects. Patients want to know information even when the information contains bad news or in terms of side-effects, no matter how rare. This may be impractical during a typically brief pharmacy encounter. Should the patient wish to have information beyond the more frequent and serious side-effects, this information can be provided in a written format. Nonetheless, it is not unusual for patients, when asked retrospectively about whether they would have liked more information about a prescribed medicine, to state that they would have liked more.

Information should be provided in a manner which takes account of what the patient may already know and what, and how much, information they would like to receive. Patients should be offered information on treatment options, to including non-pharmacological options or the choice to have no treatment. Addressing the ‘no treatment’ option is important, even when there is only one drug of choice or when the doctor has already prescribed the medicine. If the patient has reservations or concerns about a medicine that were not resolved before the medicine was prescribed, the patient will simply walk out of the pharmacy and not take it. This is the pharmacist’s opportunity to provide information on both the benefits and risks of taking and not taking a medicine, which may influence the patient’s decision-making process long after they have left the pharmacy. Throughout this process, it is important for both pharmacist and patient to communicate their thoughts, perceived dilemmas or uncertainties in treatment options, ideas and reactions to new pieces of information. Only through this process can a mutually agreeable treatment plan be devised.

Verbal information can be supported with written information, the most familiar written format being the patient information leaflet (PIL). European Union legislation requires a comprehensive medicines information leaflet to be provided in every medicines pack. There is strict guidance on the information to be included in this leaflet and, most recently, requirements on the readability of these leaflets. PILs often do not increase patient knowledge, nor do patients value them. This may, however, change as the development of PILs now includes a consultation process with the target patient groups to ensure the readability and usefulness. Findings from studies have indicated that patients would like information to be tailored to their particular illness and circumstances, to help with decision-making before prescribing occurs, and for it to contain a balance of benefit and harm information.

PILs are not the only way of communicating information. As well as verbal communication and information from PILs, other written information can include condition- or medicine-specific information guides, or use can be made of video, DVD or other interactive media. Information can also be presented in the form of a decision aid. Decision aids are patient decision support tools, which facilitate evidence-based patient choice. They normally have a number of informational elements. They provide information on available treatment options, consider the patient’s values for benefits versus harm, and facilitate the patient’s participation in treatment decisions. Like other educational materials, they can be provided as booklets, DVDs, videos or as interactive media. A systematic review of decision aids by O’Connor et al. (2003) has shown that they can increase patient knowledge, improve the proportion of patients with realistic perceptions of benefits and harms, reduce the proportion of patients who are undecided after counselling and decrease the proportion of patients who are passive in decision-making. There is a library of decision aids at the Ottawa Health Research Institute’s website covering a broad range of clinical conditions and health issues (see Appendix 4). On this website library, each decision aid is rated using a series of internationally agreed quality criteria. Many of these decision aids are American but can be adapted to the UK setting. The Medicines and Prescribing Centre at NICE provides advice and support to underpin an evidence-based patient-choice approach.

A major issue for all types of written, computer-based, audio, video and interactive information is the quality of information available. Much of the information available is poor, particularly with regard to providing accurate and adequately detailed clinical information to assist patients in decision-making. Other issues exist, such as ensuring topics of relevance to patients are included and that uncertainties in treatment need to be clearly communicated. A number of tools have been developed to assess the quality of health information, such as the DISCERN tool and the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) instrument. The tools use a range of criteria to judge the issue information, such as:

Information accuracy, comprehensiveness and reliability

Information accuracy, comprehensiveness and reliability

Clarity of aims and target audience

Clarity of aims and target audience

The comprehensibility and balance of information

The comprehensibility and balance of information

Pharmacists are not the only people who need to be able to judge the quality of health information. Patients are active information seekers and, although their most common source of health information is the doctor, other sources such as the internet are increasingly playing a part. The pharmacist is in an excellent position to act as the patient’s ‘internet guide’: to provide advice on accessing and understanding web resources, to direct them to high-quality internet sites and to discuss with them any information affecting their decision to take, or not take, a medicine (see Ch. 16). This will show the pharmacist as a resource for accessing and discussing medicines information to which patients will be likely to return in the future.

Communicating risk

A key aspect of sharing information with patients is the ability to communicate risk: to provide information on the effectiveness of a medicine or the likelihood of a side-effect occurring. Pharmacists often use words such as ‘rarely’ or ‘commonly’ to indicate to patients how frequent a particular side-effect is likely to be experienced. In an effort to standardize the interpretation of these words, the European Union (EU) has issued a guideline banding the level of risk into five groups, from ‘very common’ to ‘very rare’ (Box 18.4). However, even this approach may not ensure consistency. Evidence suggests that the general public has a tendency to reliably overestimate the risk associated with these words in comparison with the risk frequency intended by the EU. Healthcare professionals also consistently overestimate the risk level associated with these words, although not to the same magnitude that the lay public does. The use of these verbal descriptors can lead to people perceiving there is a greater risk to their health than there actually is, suggesting that they need to be used in combination with actual numbers in order to effectively communicate the intended risk level.

Expressing risks as natural frequencies (e.g. 3 out of 10 people will experience dizziness with this medicine) facilitates greater understanding of risk than presenting it as a probability statement (e.g. there is a 30% chance of dizziness with this medicine). As well as textual (or verbal) and numerical presentations of risk, other visual forms can be used, such as bar charts, icons (showing how many people in 100 are affected), pie charts, tables or survival curves. Graphical information may result in greater accuracy in determining the relative quantitative difference between risks, although icons have been found to be quite helpful to decision-making. Further research is needed on patient preferences and the benefits of alternative risk formats. It is also possible that different people may prefer different formats to aid their individual understanding of risk information. Verbal, textual, visual, graphical and numerical formats may all have a place and the key to communicating risk is a flexible approach. A greater desire for involvement in decision-making is associated with a preference for more complex risk information so the need for alternative risk formats, and flexibility in approach, is essential.

A number of factors have been shown to improve people’s understanding of risk information, including both verbal or text information and numerical or graphical information on risks can aid understanding. Presentation of information which is both positive and negative provides a more balanced view of the benefits and risks of taking a particular medicine. Taking account of the starting or baseline risk levels can also improve the accuracy of people’s judgements about, for example, the benefit associated with introducing a new medication (e.g. reduction in stroke risk). This allows people to anchor their perception at their starting level of risk and extrapolate more accurately to the potential decrease in stroke risk with starting a new medication.

Finally, whether a risk is presented as an absolute-risk reduction or relative-risk reduction can also influence people’s perception of risk. Absolute-risk reduction is the difference in risk between a control group and a treatment group. Relative-risk reduction is the absolute-risk reduction divided by the control group event rate. For example, if a new hypertensive drug decreases the risk of stroke from 0.004% (control group event rate) to 0.003% (intervention group event rate), the relative-risk reduction is 25%, although the absolute-risk reduction is only 0.001%. Relative-risk reduction sounds much more impressive and is more persuasive. Absolute-risk reduction is the preferred method for conveying accurate risk information and should be used on its own or in combination with the relative-risk reduction.

The therapeutic alliance

What are the benefits of a therapeutic alliance with patients? Once pharmacists have engaged with patients in a pharmacy consultation and a plan of action regarding medicines has been mutually agreed, what are the benefits of this process? Reviews have shown that good adherence to medication is associated with a decreased mortality. This includes adherence to placebo or beneficial drug therapy suggesting that there is a ‘healthy adherer effect’, where adherence to drug therapy may be a proxy for overall healthy behaviours. The question then becomes, does concordance improve adherence or affect other health outcomes? With concordance embracing a range of competences around the professional and patient sharing beliefs, preferences and information in a collaborative consultation process, the evidence for concordance affecting adherence depends upon how concordance has been defined. Patients rarely voice their concerns about medicines, unless encouraged to do so, and the issue of whether or not patients are taking their medicines is not always discussed in a consultation. Many of the elements perceived to be necessary for concordance (such as establishing whether or not both the professional and patient express their points of view, whether the professional respects the patient’s perspective on their illness and medicine use, or whether both work together towards shared decisions) appear not to be taking place in practice, or only taking place to a limited extent. For these reasons, finding evidence that concordance improves adherence or other health outcomes is difficult.

There is evidence on specific aspects of communication which are relevant for concordance. When patients are given information about treatment options and coached to ask questions about their condition, they are more involved in the consultation and have better health outcomes. Improvement in health outcomes can, for example, include decreased blood pressure or blood glucose levels, an improved subjective evaluation of overall health or increased functionality in terms of activities of daily living. When professionals share treatment decision making with patients and focus on the patient as a person and not merely a disease state, patient satisfaction is likely to be increased. Effective communication involving activities such as encouraging the patient to ask questions, providing information and support and sharing the decision-making process has been shown, across a range of research studies, to improve emotional health, resolve symptoms, improve function and reduce pain.

Concerns about concordance

Concerns about concordance centre on four issues:

Time. That a concordant consultation will take too long

Time. That a concordant consultation will take too long

Anxiety. That providing information to patients makes them anxious and they will either experience the side-effects that have been described to them and/or stop taking their medication

Anxiety. That providing information to patients makes them anxious and they will either experience the side-effects that have been described to them and/or stop taking their medication

Participation. People do not want to participate in decisions about their medicines

Participation. People do not want to participate in decisions about their medicines

Demands. Concordance will lead to unreasonable patient demands for expensive medicines and health care.

Demands. Concordance will lead to unreasonable patient demands for expensive medicines and health care.

Time is a concern for all healthcare professionals. Approaches such as concordance which have the potential to increase consultation times are an issue in any busy pharmacy setting. Research suggests that using a concordant approach with patients may take longer initially, but as professionals gain experience and proficiency in this approach, consultation times will decrease. There is also some evidence that if professionals do not pick up on patient clues, defined as direct or indirect comments made by patients about personal aspects of their lives or emotions, then the consultation may be longer. It seems that if a patient has issues or ideas which they hint about during a consultation, it is best to address these issues openly. If not, the patient may feel obliged to continue seeking opportunities throughout the interaction to allude to these issues and this may ultimately prolong the consultation further.

It is also now possible to separate the provision of information about options from the consultation process. This has been facilitated through the use of decision aids and other interactive media. Patients can access the information outside of the consultation and have time to think about their options, discuss them with relevant others, make a list of questions to ask the healthcare professional and then participate as an informed patient in the consultation with their healthcare professional. This may be the best solution to deal with issues of time, i.e. de-couple the provision of information about options from the constraints on consultation length. Decision aids do not replace a consultation with a healthcare professional but may enhance informed discussion by giving patients the time to think about the issues of importance to them, having taken account of the clinical information in the decision aid.

There is a concern that telling patients about the side-effects of their medicines can lead to them experiencing these side-effects. This comes from the idea that humans are suggestible; that telling people about a side-effect makes them experience it. The research on whether forewarning of side-effects affects people’s adherence can be conflicting. Yet the weight of research evidence indicates that provision of information about side-effects does not increase anxiety nor does it affect a patient’s adherence. What does seem clear is that how this information is presented can affect adherence. So presenting information on both positive and negative effects of treatment, in a manner understandable (without being patronizing) to lay people, that links into lay theories of illness and treatment (see Ch. 3) and which promotes informed choice can avoid the potential negative consequences of information overload or ‘information anxiety’.

Patients do not always want to be involved in decisions about what treatment is best for them. It is well known that there is a proportion of patients who want the doctor (most commonly) to decide what treatment is right for them. However, up to two-thirds of patients either want to decide for themselves, after the doctor has explained the options to them, or want to do so in partnership with a healthcare professional. While older people are less likely to want a more active role in decision-making than younger, more affluent people, half of those aged over 65 and those in lower social classes want to have a ‘say’ in decisions about their care. People need to be involved in decision-making to the extent that they want to be. The best way to do this is to ask them.

There is a view that if the patient’s view takes priority in an interaction between healthcare professional and patient, the patient will simply demand expensive medicines or healthcare services at the expense of those who are less articulate but more in need of health care. Given the current emphasis on the need to ration scarce healthcare resources, this is a potentially valid concern. High-profile cases in the popular press with patients demanding expensive treatments reinforce this concern. Concordance is about both parties expressing their views and if a healthcare professional has reservations about a particular treatment option (e.g. that it is of uncertain benefit or the costs outweigh the benefits), they need to explain this rationale to the patient. A common cause of litigation is poor communication between professionals and patients, such as devaluing or failing to understand the patient’s perspective. The alternative is not to inform patients of all options because one option may be particularly expensive. This can lead to patients seeking out this information on their own and raising a legitimate complaint that they were not informed about all options. Unreasonable demands may occur in a consultation but, provided both parties express their views and the rationale behind their views as part of a concordant consultation process, there is unlikely to be a basis for litigation against an individual practitioner. In the end, both parties may need to agree to differ.

Conclusion

Concordance is an opportunity for pharmacists to engage with patients on an equal level to understand their perspective on taking medicines. It argues for openness in the consultation where both professional and patient are able to express their views. Information is exchanged which may be clinical, personal, experiential and potentially worrying. Decisions are based on all types of information which are relevant for subsequent medicine taking. Ultimately, it is hoped that this will make the best use of medicines and, in situations where the patient has decided not to take a medicine, recognizes that an agreement to differ to include the open acknowledgement of the patient’s perspective is preferable to the patient going away with concerns or issues which remain unaddressed.

Key Points

Concordance promotes the view that patients have a legitimate and valuable perspective on taking decisions about their health care

Concordance promotes the view that patients have a legitimate and valuable perspective on taking decisions about their health care

The concept of concordance arose because of the need for innovative approaches to help patients with their medicines

The concept of concordance arose because of the need for innovative approaches to help patients with their medicines

Non-adherence may be unintentional or intentional

Non-adherence may be unintentional or intentional

The Standards of conduct, ethics and performance state that pharmacists have a duty to encourage patients and the public to participate in decisions about their care

The Standards of conduct, ethics and performance state that pharmacists have a duty to encourage patients and the public to participate in decisions about their care

The concordance model shares features with other models of effective communication

The concordance model shares features with other models of effective communication

Eliciting patient views is the first stage in establishing a concordant relationship

Eliciting patient views is the first stage in establishing a concordant relationship

Because concordance is concerned with the consultation, it is essential to have a good patient–pharmacist relationship

Because concordance is concerned with the consultation, it is essential to have a good patient–pharmacist relationship

Empathy plays a key role in concordance

Empathy plays a key role in concordance

Patients want information and different techniques can be used, including the use of decision aids, PILs, the internet, medicine guides, video and DVDs

Patients want information and different techniques can be used, including the use of decision aids, PILs, the internet, medicine guides, video and DVDs

When communicating risk to patients, pharmacists need to ensure that patients have understood the information fully and have received the breadth and depth of information they desire

When communicating risk to patients, pharmacists need to ensure that patients have understood the information fully and have received the breadth and depth of information they desire

The ultimate aim of concordance is to establish a therapeutic alliance between patient and healthcare provider

The ultimate aim of concordance is to establish a therapeutic alliance between patient and healthcare provider

There are strategies for reducing concerns about concordance, particularly with respect to the time it involves

There are strategies for reducing concerns about concordance, particularly with respect to the time it involves