Socio-behavioural aspects of treatment with medicines

Societal perspectives on rational use of medicines

Societal perspectives on rational use of medicines

Factors affecting the treatment process with medicines

Factors affecting the treatment process with medicines

Sociological and behavioural aspects of use and prescribing of medicines

Sociological and behavioural aspects of use and prescribing of medicines

A sociological perspective of pharmacy and the pharmacy profession

A sociological perspective of pharmacy and the pharmacy profession

Introduction

In attempting to understand the social and psychological aspects of treatment with medicines, we can to some extent apply the theoretical models for illness behaviour (see Ch. 2 and Fig. 3.1). The treatment process may be viewed from a macro- and a micro-perspective. The macro-perspective includes an analysis of the different systems and structural components in place to ensure a rational use of medicines, which is one of the primary goals of the system. The micro-perspective includes patient-related issues and the interaction between the patient and the healthcare professional.

When explaining patients’ medicine-taking behaviour and the interaction with the environment we can, for example, use the social learning theory and the concept of self-efficacy. The health belief model has been used to explain patients’ adherence in taking medicines. In addition, we need to understand the behaviour of the healthcare professional during the patient consultation and when prescribing medicines, and the interactions between healthcare professionals. Different models and theories provide different perspectives on the use of medicines, and the adequacy of the theory often depends on the question being addressed.

Functions of medicines

It has been proposed that medicines and the use of medicines serve important latent functions for the individual and society. In this context, it is important to have a wide definition of the word ‘medicines’. The functions may be the same as the approved medical uses or may have hidden functions. Barber, and later Svarstad, identified a long list of medicine functions:

Therapeutic function – the conventional use of medicines to prevent, treat and cure disease

Therapeutic function – the conventional use of medicines to prevent, treat and cure disease

Placebo function – to show concern for, and to satisfy the patient

Placebo function – to show concern for, and to satisfy the patient

Coping function – to relieve feelings of failure, stress, grief, sadness, loneliness

Coping function – to relieve feelings of failure, stress, grief, sadness, loneliness

Self-regulatory function – to exercise control over disorder or life

Self-regulatory function – to exercise control over disorder or life

Social control function – to manage behaviour of demanding or disruptive patients, hyperactive children

Social control function – to manage behaviour of demanding or disruptive patients, hyperactive children

Recreational function – to relax, enjoy the company of others, experience pleasurable feelings

Recreational function – to relax, enjoy the company of others, experience pleasurable feelings

Religious function – to seek religious meaning or experience

Religious function – to seek religious meaning or experience

Cosmetic function – to beautify skin, hair and body

Cosmetic function – to beautify skin, hair and body

Appetitive function – to allay hunger or control the desire for food

Appetitive function – to allay hunger or control the desire for food

Instrumental function – to improve academic, athletic or work performance

Instrumental function – to improve academic, athletic or work performance

Sexual function – to increase sexual ability

Sexual function – to increase sexual ability

Fertility function – to control fertility

Fertility function – to control fertility

Research function – to gain knowledge and understanding of human behaviour

Research function – to gain knowledge and understanding of human behaviour

Diagnostic function – to help make a diagnosis

Diagnostic function – to help make a diagnosis

Status-conferring function – to gain social status, prestige, income.

Status-conferring function – to gain social status, prestige, income.

One medicine may fulfil one or more functions for an individual.

A societal perspective on the rational use of medicines

Defining rational use

The rational use of medicines has been defined as the safe, effective, appropriate and economic use of medicines. This definition seems to be clear and straightforward, but the definition of safe, effective and the other components needs consideration. Safety relates to aspects like relative and absolute safety. All medicines have side-effects, some less and some more, such that they may be viewed as more or less safe. Safety has to be assessed from many different angles, e.g. the severity of the disease, the available treatment options including medicines and other options, long or short-term treatment, whether the medicine is to cure or control symptoms, and over-dosage risks.

Effectiveness relates to the question of how well the medicine works in daily practice when used by unselected populations and patients having co-morbidities and other medications. Efficacy relates to the maximum effect of the medicine in a particular disease, particularly when it is optimally used in selected patients with as few confounding factors as possible, such as co-morbidities and other medicines used simultaneously.

Appropriateness refers to how a medicine is being prescribed and used in and by patients, including aspects such as appropriate indication, with no contraindications, appropriate dosage and administration. Duration of treatment should be optimal and the medicine should be correctly dispensed with appropriate and sufficient information and counselling (see Ch. 25). To achieve the intended effects, the medicine also needs to be correctly used by the patient.

The economic aspect refers to a cost-effectiveness approach which needs to be applied, where all factors are assessed (see Ch. 22). A somewhat more expensive medicine may be preferable to a less expensive medicine, for example, because it has better treatment outcomes or fewer side-effects. Additionally, hidden costs, such as a need for more extensive laboratory tests, may increase the total cost of a particular treatment.

National medicines policy (NMP)

The rational use of medicines requires that appropriate and effective structures and processes are in place. The starting point and frame of reference is the NMP, which, particularly in developing countries, defines the policies and key issues that need consideration and the policies relating to medicines and their usage. More developed countries often already have many key issues and policies regarding medicines and their rational use already in place and therefore, the NMP receives little attention. However, the global pressure on healthcare funding, especially the increasing medicines budget, has created the momentum to look more closely at medicine policies in industrialized countries too. When trying to understand the general principles that can be applied to all countries it is helpful to use the guidelines that have been proposed for developing countries, and from there, to understand how the system works and what might be the strong and weak points in each particular country.

The NMP can be seen as a guide for action, including the goals and priorities set by the government, and their main strategies and approaches. It also serves as a framework in the coordination of different activities. Depending on cultural, historical and socioeconomic factors there are differences in objectives, strategies and approaches between countries, but some common components can be identified. The goals for an NMP can be divided into:

Health-related goals, which entail making essential medicines available, ensuring the safety, efficacy and quality of medicines, and promoting rational prescribing, dispensing and use of medicines

Health-related goals, which entail making essential medicines available, ensuring the safety, efficacy and quality of medicines, and promoting rational prescribing, dispensing and use of medicines

Economic goals, which may include lowering the cost of medicines and providing jobs in the pharmaceutical sector

Economic goals, which may include lowering the cost of medicines and providing jobs in the pharmaceutical sector

National development goals, which may include increasing the skills of personnel in pharmacy, medicine, etc. and encouraging industrial activities in the manufacturing of medicines.

National development goals, which may include increasing the skills of personnel in pharmacy, medicine, etc. and encouraging industrial activities in the manufacturing of medicines.

Ensuring the safety of medicines

Why is it important to regulate and control the medicine sector with special laws and regulations? The medicine sector is of concern to the whole population. Most citizens will use medicines and related services on a regular basis and therefore the functioning of the sector is of common interest. There are many parties involved – patients, healthcare providers, manufacturers and sales people – requiring detailed rules for interaction and functioning. The consequences from the lack of medicines or their misuse might be serious.

Legislation and regulation include different health-related laws, pharmacy law, trademark and patent laws, criminal law, international treaties (e.g. on narcotic and psychotropic drugs) and governmental decrees. Sometimes there may be a lack of political will or a weak infrastructure to enforce the laws. When looking at the legal situation in the medicine sector in different countries, the problems seem to be more often in the enforcement of legislation than in the lack of legislation.

Registration of medicines is a key tool in assuring the safety, quality and efficacy of a new medicine being introduced on to the market and in defining the legal status of the medicinal product. The infrastructure that will assure quality, safety and efficacy involves the licensing and inspection of manufacturers, distributors and their premises, and setting professional working standards. There is wide international cooperation in this field among the different component authorities. Nevertheless, every now and then the media have reports about counterfeit products and toxic products sold to the public, sometimes with disastrous consequences (see Chs 22 and 51).

Ensuring the availability of medicines

Medicines’ availability is one of the key requirements in a well-functioning pharmaceutical system. This includes a functioning manufacturing and importation system of medicines, and good procurement and distribution practices. These functions are often taken for granted in industrialized countries, while in developing countries they are key issues for a functioning system. In developing countries the maintenance of a constant supply of medicines, keeping them in good condition and minimizing losses due to spoilage and expiry are issues that need to be solved to assure the availability of medicines to the population.

As medicines increase in sophistication, the prices increase, and many new products are too expensive for much of the population if no mechanisms like price control or reimbursement/insurance systems are in place in the country. Economic availability of medicines continues to be a major policy issue for all countries at the present time.

Use of medicines

Medicine (drug) use or utilization studies and pharmacoepidemiological studies have aimed to describe the users of medicines and quantify their usage. On a population, or macro-level, factors influencing medicine consumption include among others: size of population, age and gender distributions, occupational structure, income levels, availability of health services, number and type of health facilities and personnel, along with social insurance and reimbursement mechanisms.

Medicine use studies have been used to identify ‘irrational medicine use’, such as the overuse of psychotropics and antibiotics, where there has been inappropriate prescribing and unnecessary extended treatment periods. There has also been interest in the ‘underuse’ of medicines for major chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia. Underuse of medicines, together with misuse, whether deliberate or unintentional, has been one of the main focuses of patient adherence studies. From these studies we know something about the use of medicines and the clinical, social and economic consequences.

The use of medicines should be seen within the context of a society, community, family and individual, recognizing cultural diversity in concepts of health and illness or how medicines work. To try and understand the medicine-related behaviour of patients, qualitative research methods such as in-depth interviews have been used. These studies have focused on people’s thoughts about their medicines, their motivation to take or not take the medicine, their attitudes and beliefs about the medicines and their experiences of treatments. Some general consumer behaviour models have been used to explain non-prescription and prescription purchases. In one American study the medicine attributes that consumers rated as important included possible side-effects, physician recommendation, strength, prior use, price and the availability of generic versions. Medicines are not ordinary goods and consumers appear to understand this. According to one purchase theory, purchase motivations can also be characterized as being either transformational (positive) or informational (negative). Positive purchases are made to enhance or generate a positive situation or state of mind (e.g. clothes, music) and negative purchases to minimize or prevent negative situations (e.g. car service). Negative purchases are based on (rational) choices like perceived benefits and convenience (and therefore require more information), while positive purchases are more emotional and based on subjective appeal and positive shopping experience. Research has shown that OTC medicines and vitamins are neutral on the positive–negative dimension and oral contraceptives highly negative. This type of research is still not very well developed within the pharmaceutical field.

Like general illness behaviour, medicine use occurs in a social context. Choosing self-medication or consulting a healthcare professional to obtain prescription medicines is not based solely on symptoms or clinical aspects. The concept of ‘social knowledge’ has been used to describe collective understanding, arising in a group or population, which is based on available information and prior experiences. Family members, friends, work colleagues and their experiences, books and the media in addition to our own experiences, form the basis of social knowledge of medicines. Montagne in 1996 described some interesting social conceptions or fundamental principles about medicines in people’s minds, which he calls ‘pharmacomythologies’. It is a common belief among lay people that a specific medicine produces only one ‘main’ effect, which is positive. Other effects are considered as negative or ‘side’-effects. Likewise, it is believed that a medicine produces the same main effect every time it is taken and in each person who takes it. This means that medicine effects are caused by the taken medicine and the effect of the medicine is a property residing inside the chemical compound and not a function of some change in a living human body. This perception leads to the belief that medicines cure diseases, rather than often only treating symptoms.

The general health behaviour models and theories previously presented – such as the health belief model, theory of reasoned action, social learning theory, conflict theory and behavioural decision theory – can all be used to explain certain types of behaviour related to taking medicines. Basic decision-making and problem-solving skills are important components of patients’ seemingly rational and irrational behaviours. As presented earlier, the choices do not always follow the criteria of medical rationality, but can be justified as rational by the individual patient. It may be useful to consider rationality as a continuum rather than seeing something as either rational or not. The degree of rationality an individual exhibits is also influenced by social knowledge and the micro- and macro-environment, as described earlier, as well as the actual health problem.

Improving public understanding of medicines

During the last few years there have been attempts in both developed and developing countries to improve the knowledge and understanding about medicines among the general public. This can be seen as an attempt to influence and improve (from a medical point of view) social knowledge related to medicines and health in general. National campaigns such as ‘Ask about your medicines’ are good examples of this kind of activity. A more balanced partnership between consumer-patients and healthcare providers is one of the goals in such activities. This has been referred to as concordance (see Ch. 18). A better appreciation of the limits of medicines and a lessening of the belief that there is a ‘pill for every ill’ are examples of the goals of such efforts.

Advertising and other commercial information may fail to give objective information about medicines and patients need to be encouraged to be more critical of such information. Early education in schools about health and medicines would improve health knowledge, along with guidance on using appropriate information sources. To facilitate informed choices on the use of medicines, public education should be accompanied by supportive legislation and controls on the availability of medicines. Non-governmental organizations, community groups and consumer and professional organizations should be involved in the planning and implementation of such programmes to make them seem more relevant to their target audience. Healthcare professionals need to be prepared for their role in developing a partnership with their patient to optimize treatment options.

Prescribing

The process of prescribing has gained a lot of interest lately because of ever increasing medicine costs and the concern for rational prescribing from a clinical point of view (see Ch. 20). Previously, social scientists had studied aspects such as the decision-making process in prescribing and the adoption of new medicines, using the ‘diffusion of innovations’ theory.

The extension of prescribing rights, in some countries, to a wider range of healthcare professionals has also raised the issue of ensuring that prescribers understand their responsibilities in ensuring the safe and effective use of medicines.

Functions of prescriptions

Prescriptions are primarily issued to request the supply of a specific medicine to fulfil a treatment need. However, prescribers may sometimes use a medicine knowingly or unknowingly for other reasons too. According to Smith (2002), these can be either patient or physician centred. She presented a long list of latent functions of prescriptions in addition to their intended and recognized functions (method of therapy, legal document, record source and means of communication). Medicines may be used to stimulate the patient’s expectations for recovery and to meet patients’ expectations, e.g. the use of antibiotics for viral infections or boosting a patient’s morale in intractable diseases. The prescriber may also want to gain some time to diagnose the condition more precisely. The medicine legitimizes the healthcare professional–patient relationship. The prescription is a sign of the prescriber’s commitment to try to heal and care for the patient. Finally, the prescriber may use the prescription to communicate to the patient that the consultation is over.

For the patient, the prescription may legitimize their illness and confirms that they have fulfilled one of the obligations of the sick role, to try to become well again. There may be an expectation from the patient that they will receive a prescription and they may be reluctant to leave without one.

Prescribing can also raise ethical dilemmas, for example when purposely using placebos. Does the patient have the right to know what they are being given and in not informing the patient is the physician respecting the rights of the patient?

Choosing the right medicine

Therapeutic effect is of primary importance when the prescriber decides which medicine to prescribe. A second consideration is the incidence and severity of side-effects. Prescribers have been shown to concentrate on a few serious side-effects and ignore those that they perceive to be less important, even where this may not match the perception of the patient. Economic aspects have a lower priority than the first two dimensions, although if patients pay, the prescriber may give more attention to the cost of the medicine prescribed. Patient convenience and compliance may be decision criteria in situations when medically similar preparations are available, e.g. suppositories not being recommended when oral preparations are feasible. When prescribing for children, taste may be an important factor to consider (see Ch. 33).

Prescribers who work with others or are part of a professional network are often some of the first to use new medicines, while those who work alone adopt a new preparation more slowly than those working in group practices.

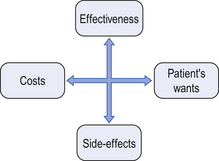

Barber summarized the areas that a prescriber considers and tries to balance, when deciding to prescribe a medicine (see Fig. 3.1):

Models to study prescribing

Several studies have tried to determine if there are specific characteristics of prescribers and their work settings that would explain their prescribing behaviours. Three general models or approaches have been used to study prescribing:

Models focusing on demographic and practice variables which give descriptive information about what and how prescribers tend to prescribe. These variables are often difficult or impossible to change, but these studies help to determine possible focal points for prescribing interventions

Models focusing on demographic and practice variables which give descriptive information about what and how prescribers tend to prescribe. These variables are often difficult or impossible to change, but these studies help to determine possible focal points for prescribing interventions

Models focusing on psychosocial issues related to prescriber–patient interaction

Models focusing on psychosocial issues related to prescriber–patient interaction

Models focusing on the cognitive theories that explain prescribing decisions. These studies focus on how prescribers evaluate product and clinical information and their decision-making processes.

Models focusing on the cognitive theories that explain prescribing decisions. These studies focus on how prescribers evaluate product and clinical information and their decision-making processes.

These studies have shown some differences in prescribing behaviour, although the underpinning reasons are sometimes less clearly determined. Prescribing behaviour may be erratic, with a prescriber prescribing rationally in one area and less rationally in another. More recently graduated prescribers seem to prescribe more rationally and in line with clinical evidence than those who are older. It has been found that prescribers with a negative attitude towards the use of medicines for social problems tend to prescribe fewer psychotropic medicines. Where non-medicine, alternative treatments are available, such as with cognitive behavioural therapy for depression, there is a reduction in benzodiazepine prescribing. A study found that a more cosmopolitan attitude and a more critical attitude towards commercial information are associated with more careful prescribing of potentially risky medicines. Another study showed that ‘less rational prescribers’, defined as those with a high rate of benzodiazepine prescriptions, rely more on commercial information from the pharmaceutical industry than from other sources. Professional satisfaction and reading professional material seem to translate into better prescribing.

Personal experiences also influence prescribers, as they do patients. For example, previous experiences of adverse drug reactions may decrease the prescriber’s willingness to prescribe a particular drug, and conversely, experiencing positive outcomes in other patients may encourage the prescriber to use the medication in future. Individuals may use positive personal experiences to legitimize their irrational prescribing decisions.

Certain patient factors also influence the probability of receiving a prescription for psychotropic medicines. The most widely studied factors have been age and gender. The elderly are usually prescribed more than younger people, which may be a reflection of a higher rate of symptoms and psychological distress and the nature of the longer-term conditions from which the elderly are more likely to suffer. Women are prescribed psychotropic medicines more often, possibly due to them being more likely to seek professional help.

The nature of the consultation process

In considering why some patients take medicines and why some do not, it is important to look at how the decision to prescribe is taken from the patient’s perspective. In traditional, paternalistic models of prescribing, the prescriber decides on the treatment, prescribes a drug and the patient goes away and does as they are told. They must be compliant with the wishes of the doctor in order to get well, regardless of whether this fits into their life, respects their beliefs and values, or is what they want.

Including the patient in the decision over whether there should be a medicine prescribed, and if so, what this should be, is important in encouraging the patient to commit to the treatment protocol. This can be of particular importance where the illness does not manifest itself in symptoms on a daily basis, and therefore does not normally inconvenience the patient, such as hypertension.

Over the last 15 years, there has been a movement to encourage patients and prescribers to work together, as a partnership, to determine the appropriate treatment protocol for the individual and their lifestyle. This partnership has been termed ‘concordance’ and is seen as a move away from paternalistic compliance by the patient to the prescriber’s instructions (see Ch. 18).

Ultimately, it is up to the patient whether or not they take their medication once they get home. There are a number of models that try to define aspects of the patient–practitioner relationship. Paternalism is at one end of the spectrum, where the power and decision making lies with the prescriber, and consumer choice at the opposite end, with all the power lying with the consumer or patient.

The model that relates most closely to the concept of concordance is the shared decision-making model. This model incorporates four fundamental factors that are required for shared decision making to occur:

Both the prescriber and the patient must be involved in the decision-making process. Others may also be included, such as other healthcare professionals, carers, etc

Both the prescriber and the patient must be involved in the decision-making process. Others may also be included, such as other healthcare professionals, carers, etc

Information is shared by all the participants

Information is shared by all the participants

Both prescriber and patient participate and express their preferences with regards to treatment options

Both prescriber and patient participate and express their preferences with regards to treatment options

The treatment decision needs to be agreed upon by both parties.

The treatment decision needs to be agreed upon by both parties.

If the patient chooses to abdicate responsibility for treatment decisions to the healthcare professionals, this may be concordant. The important factor is that they have the option to participate fully.

Both the patient and the practitioner need to develop their relationship and skills to ensure that they can participate in the shared decision-making process. Pharmacists need to consider the communication skills that are needed to negotiate with the patient and gain their agreement to a mutually approved treatment plan.

It is entirely appropriate for the prescriber to provide the patient with evidence-based information for them to use in reaching their decision. This needs to be presented in a way that enables the patient to understand the information.

Individuals are influenced by a number of external factors when making decisions relating to their health and illness and this is also true in relation to their medicines. Concordance recognizes that individuals will value the various aspects they are considering subjectively and they will also vary in their willingness to take risks and deal with uncertainty (see Ch. 18). Concordant discussions with patients were not the norm – equal sharing of views was not common.

It needs to be recognized that pressures on prescriber’s time may not help with concordance. A 10 minute consultation period limits the scope for shared decision making. Pharmacists need to consider this when arranging appointments to discuss medication with patients. Time is needed for a concordant discussion and this may pay back in terms of more successful use of medication.

Influencing prescribing

Providing information and employing educational programmes to change prescribers’ prescribing behaviour has become an integral part of the pharmacist’s role. Pharmacists participate in this kind of activity as part of their daily work in community, hospital or primary care, and there have also been formal prescribing intervention programmes used in research studies. It has been shown that pharmacists who provide information and education for prescribers can produce positive effects on their knowledge and attitudes, but the effects on prescribing behaviour have usually been modest. However, interventions by healthcare professionals, such as pharmacists, are more effective than simply providing printed material alone, which does not influence prescribing habits.

Individual feedback coupled with one-to-one education is the method most likely to be successful. Prescribers are most receptive to education in their own practice base and the facilitators (often pharmacists) should be professional and well briefed, and the messages should be concise, clear and relevant to the prescriber. An ongoing programme with regular repeat visits is needed to maintain the contact and keep the messages up to date. Additionally processes and procedures, such as formularies which limit prescribing, hospital or regional drug and therapeutic committees providing advice on prescribing, drug utilization review, audit and treatment guidelines, also help to ensure rational prescribing.

The changing nature of prescribers

Another factor that may play an increasingly important role in prescribing behaviour is the extension of prescribing rights to other healthcare professions. In the UK for example, prescribers may now come from nursing, midwifery, pharmacy, physiotherapy and other healthcare professions if they have undertaken appropriate additional training (see Ch. 4). These individuals will have different backgrounds and experiences that may influence their prescribing habits. It may also be necessary to look at implementing wider education programmes for prescribers aimed at those from all backgrounds.

Pharmacies and the pharmacy profession

Historically, a pharmacy has been the place for preparing and dispensing medicines. The first known pharmacy was established in the year 766 in Baghdad. In Europe, the first pharmacies date back to the eleventh century. In ancient times, the same person acted as both doctor and pharmacist, i.e. diagnosed, prescribed and prepared the medicines for the patient. But in 1231, the German emperor and king of Sicily, Frederick II of Hohenstaufen in the edict of Palermo, legally separated the professions of medicine and pharmacy. Physicians were to diagnose and prescribe medicines, while pharmacists were to be responsible for preparing the medicines and providing these to the patients. Pharmacies were also designated to certain areas, where they had the monopoly of selling medicines. Frederick also laid down rules about the education of healthcare professionals. These and other provisions given by him were the basis of the legislation and practice of pharmacy in many European countries until the twentieth century.

Elsewhere, the distinction between the medical and pharmaceutical professions has not always been so clear. While medicine and pharmacy are clearly defined practice areas in the UK, there are still ‘dispensing doctors’ who both prescribe and dispense the medication for their patients from one premises. The system of dispensing doctors has been defended based on availability and grounds of patient convenience. The problems related to the system are an apparent conflict of interest, which is present when the income of the physician depends on the volume and price of medicines prescribed. Japan also has issues relating to dispensing doctors: they have one of the highest costs of medicines per capita in the world and prescription medicines in Japan are mainly distributed by physicians. The same conflict of interest is often mentioned in the context of the professional and business roles of the pharmacist, especially concerning sales of non-prescription medicines.

There has been much discussion in the literature about pharmacy and whether it is a true profession. Two major approaches have been used by academics in trying to answer the question. One approach is to look at the functions pharmacists perform for society, asking if they are vital for the society. The second approach is to look at certain characteristic traits of the occupation and determine whether they fulfil typical traits of a profession. During the last 50 years, different traits have been mentioned by different academics, but there are some common ones. The following are traits that characterize a profession:

Registration or state certification embodying standards of training and practice in some statutory form

Registration or state certification embodying standards of training and practice in some statutory form

A fiduciary practitioner–client relationship

A fiduciary practitioner–client relationship

Most authors agree that the basic traits of a learned profession are advanced and lengthy training in a highly specialized body of knowledge. This knowledge is to be used in the service of society and mankind. Research and abstract reasoning are the ways of expanding this unique body of knowledge. The services provided by a profession are related to the degree of impact or danger they may have on individuals or society. Besides the expert knowledge the professional possesses, he must also exert his professional judgement to the benefit of the client. Co-workers, in the same or related occupations, acknowledge the level of expertise of the profession, which is also important in legitimating the practice. There is a certain level of trust that the public must place in the work performance of the professional. Professionals themselves define which kind of activities are allowed and what privileges members may claim. They also define, through ethical codes and legislation which they have often themselves had an opportunity to draw up, the type of controls that guarantee the social privileges given to them (like autonomy of action, monopoly of practice, remuneration) are not abused. Pharmacy can be argued to fulfil all of the requirements above and therefore, in the practice of clinical pharmacy and providing clinical care for their patients, pharmacists are very much professionals.

International guidelines for good pharmacy practice by the FIP

The International Pharmacy Federation (FIP) has issued its guidelines for good pharmacy practice (GPP), stating that the mission of pharmacy practice is to provide medications and other healthcare products and services and to help people and society to make the best use of them. The concept of GPP is based mainly on the concept of pharmaceutical care. The patient and community are the primary beneficiaries of the pharmacist’s actions and the pharmacist’s first concern must be the welfare of the patient in all settings. The core of pharmacy activity is the supply of medication and other healthcare products of assured quality, along with giving appropriate information and advice to the patient and monitoring the effects of the medicine used. From an international perspective, a rather new aspect is the quest for the pharmacist’s contribution to the promotion of rational and economic prescribing and appropriate medicine use. According to GPP, the objective of each element of pharmacy service should be relevant to the individual, clearly defined and effectively communicated to all those involved.

In satisfying GPP requirements, professional factors should be the main philosophy underlying practice. Economic factors are also important, but they should not be the driving force. Pharmacists should give their input to decisions on medicine use, and a therapeutic partnership with prescribers and good relationships with other healthcare professionals, including other pharmacists, are important. Pharmacists are also responsible for the evaluation and improvement of the quality of services given. There is a need to keep patient profiles and to record pharmacists’ interventions. Pharmacists need independent, comprehensive, objective and current information about medicines. They should also accept personal responsibility for lifelong learning and educational programmes should address changes in practice. National standards of GPP need to be put in place and adhered to.

According to the guidelines there are four main elements of GPP: promotion of good health, supply and use of medicines, self-care and influencing prescribing and medicine use. It also encompasses cooperation with other healthcare professionals in health promotion activities, including the minimization of abuse and misuse of medicines. Professional assessment of promotional materials for medicines should also be carried out and evaluated, and appropriate materials should be disseminated to the public. Pharmacist involvement in all stages of clinical trials is also recommended. The guidelines include further areas within the four main elements that need to be addressed, such as national standards for facilities for confidential conversation, provision of general advice on health matters, involvement in health campaigns and the quality assurance of equipment used and advice given in diagnostic testing. In the supply and use of prescribed medicines, standards are needed for facilities, procedures and use of personnel. Assessment of the prescription by the pharmacist should include therapeutic aspects (pharmaceutical and pharmacological), appropriateness for the individual and social, legal and economic aspects.

Furthermore, national standards are needed for information sources, competence of pharmacists and medication records. Advice should be given to ensure that the patient receives and understands sufficient oral and written information. It is also important to have standards on how to follow up the effect of prescribed treatments and the recording of professional activities. When trying to influence prescribing and medicine use, general rational prescribing policies and national standards are needed. In research and practice documentation, pharmacists have a professional responsibility to document professional practice experience and activities and to conduct and/or participate in pharmacy practice research and therapy research. These guidelines form an international consensus on the current practice of pharmacy and point to the direction for national guidelines to improve it.

Outcomes of medical treatment

Evaluation and outcomes research

Evaluation and outcomes research are fairly new topics within pharmacy. They are integral elements of pharmaceutical care and much more effort needs to be put into these aspects of pharmacy practice and research in the future. Evaluation has been defined as making a comparative assessment of the value of the intervention, using systematically collected and analysed data, in order to make informed decisions about how to act or to understand causal mechanisms and general principles. One important aspect from society’s point of view is the question ‘What are we getting for our money?’ According to the model originally proposed by Avedis Donabedian, evaluation of health care can focus on:

Structure, e.g. facilities, equipment, money, number and qualification of personnel

Structure, e.g. facilities, equipment, money, number and qualification of personnel

Process, e.g. activities by staff and patients such as prescribing and counselling

Process, e.g. activities by staff and patients such as prescribing and counselling

Outcomes, e.g. intermediate outcomes such as patients’ knowledge and behaviour, and final outcomes such as curing the disease.

Outcomes, e.g. intermediate outcomes such as patients’ knowledge and behaviour, and final outcomes such as curing the disease.

Traditionally, evaluation has focused on structure and process and to a lesser extent on outcomes. More recently, a whole new research field has emerged within health care called ‘outcomes research’.

One difficulty in health-related outcomes research is to demonstrate the links between the three elements of the model: structure–process–outcome. For example, will a new computer-based patient medication record system in the pharmacy (structure) improve the follow-up of a patient (process), so that the pharmacist is able to detect more efficiently a medicine-related problem in the use of the antihypertensive medicine with the outcome of lowered blood pressure and the patient feeling better and living a healthier, longer and happier life (outcome)? Even if there is little empirical evidence, it is the general view that good structure leads to a more appropriate process resulting in better outcomes.

Many of the interventions, treatments and procedures used in health care are still not backed by strong evidence for efficacy, effectiveness and safety. While new medicines are thoroughly tested and evaluated, there are older treatments for which the evidence of efficacy may be weak, and even when a medicine has a proven benefit, it still needs to be prescribed and taken correctly.

Within the pharmaceutical field a more comprehensive framework for the assessment of medicines and treatments has been proposed. This model, named ECHO, classifies outcomes in three categories: economic, clinical and humanistic outcomes. Clinical outcomes have been defined as medical events that occur as a result of the condition or its treatment. Economic outcomes are the direct, indirect and intangible costs compared with consequences of medical treatment alternatives. Humanistic outcomes include well-being, health-related quality of life and patient satisfaction. The ECHO model allows pharmaceutical interventions to be planned, implemented and assessed in a way that incorporates different perspectives, potentially providing a more complete assessment of the intervention.

Health-related quality of life

The primary objective of health care is to improve a patient’s quality of life. To what extent this objective is achieved often remains unanswered. This may be due to a lack of proper measures, the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare providers or some other factors. The central feature and objective of pharmaceutical care is to achieve outcomes by identifying, solving and preventing medicine-related problems in order to improve a patient’s quality of life. In experimental settings this has been shown to be the case but the extent to which this is achieved in ordinary everyday practice is still open to question, as not all studies of practice-based interventions have shown positive effects.

A classic list of outcomes in medical care has been crystallized in the ‘five Ds’ – death, disease, disability, discomfort and dissatisfaction. These include a wide range of different aspects, but are all negative terms. Utilizing the ‘five Ds’ to assess a patient’s quality of life will give partial answers only but does not allow all the aspects that might be included in quality of life to be assessed. Quality of life is not just the absence of the negative but also incorporates a measure of the positive. The term ‘health-related quality of life’ has been used quite differently in the literature and daily practice. Explicit definitions are quite rare because of the multidimensionality of the concept. The domains of health-related quality of life usually include functional health (physical activity, mobility and self-care), emotional health (anxiety, stress, depression, spiritual well-being) social and role functioning (personal and community interactions, work and household activities), cognitive functioning (memory), perceptions of general well-being and life satisfaction, and perceived symptoms.

Health-related quality of life has been measured with disease-specific instruments and general or generic instruments, e.g. health profiles and measures based on utilities. Disease-specific instruments provide a greater detail concerning functioning and well-being in that particular disease. The disease-specific measures (e.g. those used in hypertension and asthma) can also be further categorized as population specific (e.g. elderly), function specific (e.g. sexual) and condition specific (e.g. pain). Examples of these instruments include the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire and the Diabetes Quality of Life Questionnaire.

The generic measures include health profiles, which constitute a number of questions covering the different aspects, giving separate scores for each domain of life. Examples include the Nottingham Health Profile, Sickness Impact Profile, McMaster Index and SF-36. The advantage of health profiles is that they provide a comprehensive array of scores that is multidimensional. If the measure used is sensitive enough, through the profile, we may be able to distinguish, for example, when a medicine influences the emotional domain while having no effect on the functional health domain.

The utility-based measures incorporate specific patient-health states while adjusting for the preferences (utilities) for the health state. The outcome scores range from 0 to 1, where 0 represent quality of life associated with death and 1 represents perfect health. The preferences have been empirically tested in different populations and have been through a validation process. These utility-based measures have been extensively used in pharmacoeconomics research and more specifically in cost–utility analysis (see Ch. 22).

The most accurate and comprehensive end result may be achieved by using both a generic and a disease-specific measure when possible. The focus in current medicine is more on patient-perceived impact on long-term morbidity than on limiting mortality. It is good to remember that medicines can both increase and decrease the quality of life. The goal of medical therapy is to improve health and make patients feel better. Physiological measures may change without people feeling any better, for example, treating mildly elevated blood pressure may show a change in measured blood pressure without the patient experiencing any change as they may have been asymptomatic to begin with. Nevertheless, treatment may improve subjective health without any measurable changes in clinical parameters. There may also be a trade-off between positive treatment outcomes and adverse events.

In trying to measure quality of life, many of the measurement tools change subjective experience into quantitative data. Given the subjective nature of quality of life this may simplify the reality for the patient.

Client and patient satisfaction

An important aspect when measuring the outcomes of pharmacy practice and pharmaceutical interventions is the satisfaction of clients and patients. Measurement of client satisfaction can be an important tool in quality assurance of pharmacy practice (see Ch. 12). There are difficulties in defining the quality of pharmacy services. One approach is to divide the quality into a technical dimension (i.e. what is offered) and a functional dimension (i.e. how it is offered). Different proposals have been made to cover different aspects of service provision in general. One comprehensive model is that by Parasuram: he distinguishes between 10 different dimensions: reliability, responsiveness, competence, access, courtesy, communication, credibility, security, understanding/knowing the customer and tangibles. Hedvall has presented a somewhat simplified model. She has proposed four dimensions: professionalism, commitment, confidentiality and milieu, which also contain the essence of that which Parasuram proposed. In assessing service provision, customers may have difficulty in distinguishing between all 10 dimensions and some of them tend to overlap. The proposed dimensions represent important aspects to both prescription and self-care clients visiting the pharmacy. These aspects also have a direct linkage to communication skills and pharmaceutical care.

Measurement of patient satisfaction has usually focused more specifically on aspects in providing care. Cleary and McNeil have listed the following dimensions that are typically covered in the measurements of patient satisfaction: accessibility and availability of care, convenience, technical quality, physical setting, efficacy, personal aspects of care, continuity and economic aspects. In these dimensions, we can distinguish a technical or cognitively based evaluation of the services offered and also an emotional or affective aspect – how well they are offered. The significance of client satisfaction can be correlated to patronage, patient adherence, and ultimately to the survival of the pharmacy profession.

Key Points

Medicines have a wider function than merely treating disease

Medicines have a wider function than merely treating disease

Rational use of medicines is defined in terms of safety, effectiveness, appropriateness and economics

Rational use of medicines is defined in terms of safety, effectiveness, appropriateness and economics

Society expects the medicines used to be safe and attempts to achieve this by employing legislation and regulation supported by pharmacoepidemiological studies

Society expects the medicines used to be safe and attempts to achieve this by employing legislation and regulation supported by pharmacoepidemiological studies

Patients’ medicine use behaviour is influenced by complex social and behavioural factors

Patients’ medicine use behaviour is influenced by complex social and behavioural factors

Prescribing is a complex process in which the prescriber has to balance cost, effectiveness, side-effects and the patient’s needs and wants

Prescribing is a complex process in which the prescriber has to balance cost, effectiveness, side-effects and the patient’s needs and wants

The professional status of pharmacy can be determined from its role in society and the service characteristics of pharmacists in society

The professional status of pharmacy can be determined from its role in society and the service characteristics of pharmacists in society

Evaluation of health care is achieved by measuring structure, process and outcomes

Evaluation of health care is achieved by measuring structure, process and outcomes

Outcomes may be economic, clinical or humanistic

Outcomes may be economic, clinical or humanistic

Health-related quality of life can be assessed using disease-specific questionnaires or general health profiles

Health-related quality of life can be assessed using disease-specific questionnaires or general health profiles