18 ANALYSIS: ONE LUNG LOOKS BLACKER

WHICH SIDE IS ABNORMAL?

Rule of thumb: In most instances the side that is blacker is the abnormal side.

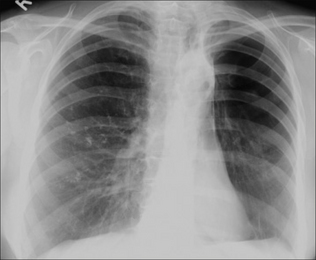

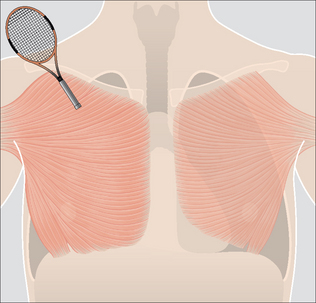

Important rider: On occasion one side will appear blacker because the opposite side is abnormal (i.e. denser/more opaque) (Figs 18.2-18.5). A more dense hemithorax (e.g. on the right side) may result from:

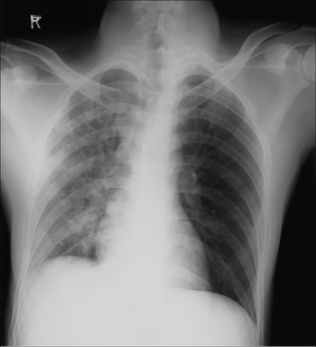

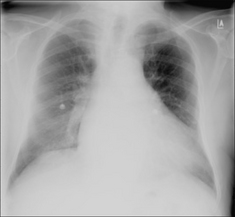

Figure 18.2 This patient’s left side will appear blacker than the right on a CXR. This is because he is a right-handed tennis player whose right pectoral muscles are highly developed…they absorb more of the x-ray beam than does the less developed left side.

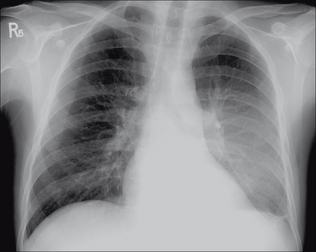

Figure 18.3 Right-sided malignant pleural effusion was treated with a pleurodesis. This additional pleural fluid and thickening absorbs more of the x-ray beam and so the normal left side looks blacker.

HYPERTRANSRADIANCY: HOW COMMON?

Unilateral hypertransradiancy is a common finding. In our analysis of 200 otherwise normal PA CXRs it occurred in 35% of patients (see Chapter 16, p. 243). The explanation was patient rotation in half of these cases. In 42% the cause was not obvious, though these are likely to have been due to other technical factors (Table 18.1).

Table 18.1 Unilateral Hypertransradiant Hemithorax.

| Cause | |

|---|---|

| Technical | |

| Chest wall abnormality | Asymmetric soft tissues3,4 |

| Skeletal abnormality | Scoliosis |

| Airways disease | |

| Vascular disease |

HYPERTRANSRADIANCY: A HELPFUL CLASSIFICATION

Technical factors account for the vast majority of cases of unilateral hyper-transradiancy. Nevertheless, there are occasions when the finding indicates underlying disease (Table 18.1) on the hypertransradiant, i.e. blacker, side. For this reason it is worth carrying out a simple step-by-step analysis whenever one lung appears blacker than the other (see p. 258).

HYPERTRANSRADIANCY: A STEP-BY-STEP ANALYSIS

If you have decided that the more opaque (denser) side is the normal side, adopt this step-by-step approach, concentrating on the side that is blacker.

STEP 1

Question: Is the medial end of each clavicle equidistant from the midline?

No—rotation is the likely explanation (Fig. 18.6).

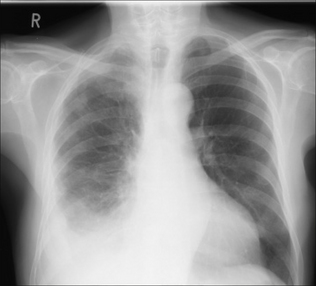

Figure 18.6 The patient is rotated slightly to the right. The right side appears blacker. This obeys the rule of rotation2.

The rule of rotation: The side with the medial end of the clavicle furthest from the midline will be blacker. If this rule is broken, suspect another cause2.

STEP 2

Question: Are the soft tissues around the scapula and the axilla on the blacker side more penetrated (i.e. not quite so white as on the normal side)?

Yes—incorrect centering of the x-ray beam is the likely explanation (Fig. 18.7).

Figure 18.7 The left side appears blacker. No rotation. Note that the scapula and soft tissues on the left side are less white (i.e. better penetrated) than those on the right. This indicates that the x-ray beam is decentred to the left—consequently the left-sided tissues (including the lung) appear blacker.

STEP 3

Question: Are the chest wall soft tissues asymmetric?

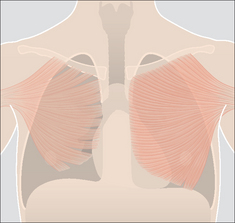

The clinical history and/or the physical examination is crucial: e.g. mastectomy; absent or hypoplastic pectoral muscles (Figs 18.8 and 18.9).

STEP 4

Question: Is there a scoliosis?

This may result in alterations to the soft tissues in the path of the x-ray beam (Fig. 18.10). Also, a scoliosis may cause uneven compression of the anterior chest wall against the cassette.

This may result in alterations to the soft tissues in the path of the x-ray beam (Fig. 18.10). Also, a scoliosis may cause uneven compression of the anterior chest wall against the cassette. NB: uneven compression of chest wall soft tissues against the cassette, even in the absence of a scoliosis, is a very common cause1 of unilateral hypertransradiancy (Table 18.1).

NB: uneven compression of chest wall soft tissues against the cassette, even in the absence of a scoliosis, is a very common cause1 of unilateral hypertransradiancy (Table 18.1).STEP 5

NONE OF THE ABOVE? Now consider pulmonary or pleural pathology.

Question: Is there evidence of airways disease?

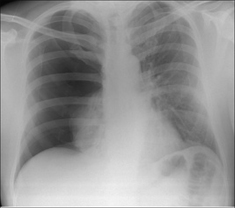

Figure 18.11 The right side appears blacker. Large right pneumothorax with major collapse of the right lower lobe.

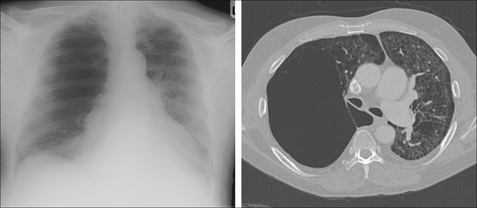

Figure 18.12 The right side appears blacker. Airways disease…very large emphysematous bulla compressing the right lower lobe. CT section to illustrate.

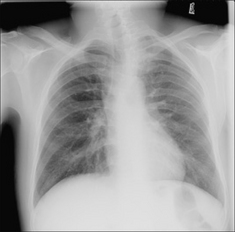

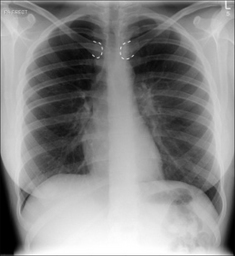

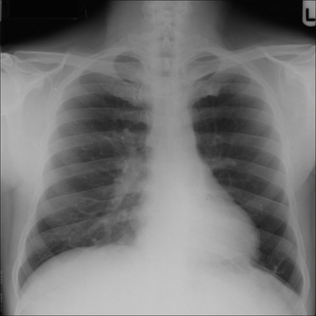

Figure 18.13 The left side appears blacker. Airways disease. Note that there are fewer vessels in the left lung compared with a similar area in the right lung. There is a differential diagnosis for this appearance. In this patient the explanation proved to be the Swyer–James syndrome (also known as MacLeod’s syndrome)…resulting from bronchiolitis obliterans in childhood3,4,7,9.

STEP 6

NONE OF THE ABOVE? Now consider vascular disease.

Question A: Are there any clinical features to suggest arterial disease?

Question B: Is there any suggestion of a tumour at or adjacent to the hilum?

A tumour may cause secondary constrictive effects, including obstruction, to the adjacent pulmonary artery.

Answer to Fig. 18.1 on p. 254

Analysis: No evidence of rotation. Scapula density similar on the two sides. No scoliosis. The left hilum is elevated. Fibrotic shadowing in left upper zone. Fewer vessels in the left lung compared with a similar area in the right lung.

Conclusion: The left lung is blacker because there is major contraction (collapse and shrinkage) of the left upper lobe with consequent compensatory hyperinflation of the lower lobe.

SPECIFIC CAUSES OF UNILATERAL HYPERTRANSRADIANCY

EMPHYSEMA

See Chapter 22, pp. 285–286. Emphysematous changes are often asymmetric with one lung or one lobe predominantly affected.

BRONCHIAL OBSTRUCTION CAUSING LOBAR COLLAPSE

See Chapter 5, pp. 57–66. Major collapse of a lobe will result in compensatory emphysema (i.e. lobar over-expansion) in the unaffected lobe/lobes. The over-expansion of the lobe together with shunting of arterial blood to the opposite lung produces the unilateral hypertransradiancy. This effect is most commonly seen in adults with bronchial obstruction.

BRONCHIAL OBSTRUCTION DUE TO AN INHALED FOREIGN BODY5

See Chapter 14, p. 201. Occurs most commonly in young children. Though lobar collapse with compensatory emphysema in the unaffected lobe/lobes may occur it is more common for the foreign body to cause a ball valve obstruction and consequent air trapping. The affected lung appears blacker and larger than the opposite side.

CONGENITAL LOBAR EMPHYSEMA6

See Chapter 14, p. 203. There is developmental bronchial narrowing with progressive air trapping and over-expansion of the lobe or lung segment distal to the stricture. The majority of affected patients present within one month of birth. Presentation after six months is rare. The CXR shows an area of hypertransradiancy. Shift of the mediastinum to the opposite side and compression collapse of adjacent lung segments are commonly associated findings.

SWYER–JAMES SYNDROME7,8

Also known as MacLeod’s syndrome. This results from viral bronchiolitis obliterans occurring in childhood which adversely affects normal development of the bronchial tree. Patients are thereafter usually asymptomatic. The CXR appearance of unilateral hypertransradiancy is often an incidental finding in adulthood. Characteristic findings on CT will confirm the diagnosis8.

PULMONARY EMBOLISM

A massive pulmonary embolus producing a decrease in pulmonary blood flow may cause unilateral hypertransradiancy. A focal hypertransradiancy is often referred to as Westermark’s sign9. It is a very rare finding. More often, any hypertransradiancy in a severely ill patient—even one who has sustained a pulmonary embolus—is due to a technical factor, e.g. patient rotation.

1. Crass JR, Cohen AM, Wiesen E, et al. Hyperlucent thorax from rotation: anatomic basis. Invest Radiol. 1993;28:567-572.

2. Joseph AE, de Lacey GJ, Bryant TH, et al. The hypertransradiant hemithorax: the importance of lateral decentering, and the explanation for its appearance due to rotation. Clin Radiol. 1978;29:125-131.

3. Reed JC. Chest Radiology: Plain Film Patterns and Differential Diagnosis, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, 2003.

4. Collins J, Stern EJ. Chest Radiology: The Essentials. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1999.

5. Baharloo F, Veyckemans F, Francis C, et al. Tracheobronchial foreign bodies: presentation and management in children and adults. Chest. 1999;115:1357-1362.

6. Kennedy CD, Habibi P, Matthew DJ, et al. Lobar emphysema: long-term imaging follow up. Radiology. 1991;180:189-193.

7. Stokes D, Sigler A, Khouri NF, et al. Unilateral hyperlucent lung (Swyer–James syndrome) after severe mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;117:145-152.

8. Moore AD, Godwin JD, Dietrich PA, et al. Swyer–James syndrome: CT findings in eight patients. AJR. 1992;158:1211-1215.

9. Worsley DF, Alavi A, Aronchick JM, et al. Chest radiographic findings in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: observations from the PIOPED study. Radiology. 1993;189:133-136.