CHAPTER 78 Supportive Periodontal Treatment

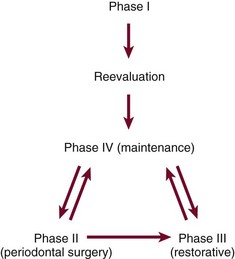

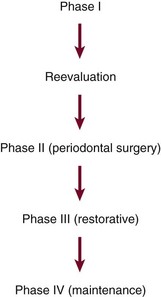

Preservation of the periodontal health of the treated patient requires as positive a program as that required for the elimination of periodontal disease. After Phase I therapy is completed, patients are placed on a schedule of periodic recall visits for maintenance care to prevent recurrence of the disease (Figures 78-1 and 78-2).

Figure 78-1 Incorrect sequence of periodontal treatment phases. Maintenance phase should be started immediately after the reevaluation of Phase I therapy.

Transfer of the patient from active treatment status to a maintenance program is a definitive step in total patient care that requires time and effort on the part of the dentist and staff. Patients must understand the purpose of the maintenance program, and the dentist must emphasize that preservation of the teeth depends on maintenance therapy. Patients who are not maintained in a supervised recall program subsequent to active treatment show obvious signs of recurrent periodontitis (e.g., increased pocket depth, bone loss, or tooth loss).7,10,16 The more often patients present for recommended supportive periodontal treatment (SPT), the less likely they are to lose teeth.70 One study found that treated patients who do not return for regular recall are at 5.6 times greater risk for tooth loss than compliant patients.16 Another study showed that patients with inadequate SPT after successful regenerative therapy have a fiftyfold increase in risk of probing attachment loss compared with those who have regular recall visits.18

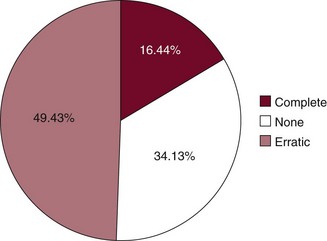

Motivational techniques and reinforcement of the importance of the maintenance phase of treatment should be considered before performing definitive periodontal surgery.10 Studies have shown that few patients display complete compliance with recommended maintenance schedules1,33,37,39,40,69,71 (Figure 78-3). It is meaningless simply to inform patients that they are to return for periodic recall visits without clearly explaining the significance of these visits and describing what is expected of patients between visits.

Figure 78-3 Compliance with maintenance therapy in 961 patients studied for 1 to 8 years.

(Modified from Wilson TG Jr, Glover ME, Schoen J, et al: J Periodontol 55:468, 1984.)

The maintenance phase of periodontal treatment starts immediately after the completion of Phase I therapy (see Figures 78-1 and 78-2). While the patient is in the maintenance phase, the necessary surgical and restorative procedures are performed. This ensures that all areas of the mouth retain the degree of health attained after Phase I therapy.

Rationale for Supportive Periodontal Treatment

Studies have shown that even with appropriate periodontal therapy, some progression of disease is possible.23,26,41,46,63,67 One likely explanation for the recurrence of periodontal disease is incomplete subgingival plaque removal.66 If subgingival plaque is left behind during scaling, it regrows within the pocket. The regrowth of subgingival plaque is a slow process compared with that of supragingival plaque. During this period (perhaps months), the subgingival plaque may not induce inflammatory reactions that can be discerned at the gingival margin. The clinical diagnosis may be further confused by the introduction of adequate supragingival plaque control because the inflammatory reactions caused by the plaque in the soft tissue wall of the pocket are not likely to be manifested clinically as gingivitis. Thus inadequate subgingival plaque control can lead to continued loss of attachment, even without the presence of clinical gingival inflammation.

Bacteria are present in the gingival tissues in chronic and aggressive periodontitis cases.13,17,43,48 Eradication of intragingival microorganisms may be necessary for a stable periodontal result.20 Scaling, root planing, and even flap surgery may not eliminate intragingival bacteria in some areas.18 These bacteria may recolonize the pocket and cause recurrent disease.

Bacteria associated with periodontitis can be transmitted between spouses and other family members.2,64 Patients who appear to be successfully treated can become infected or reinfected with potential pathogens. This is especially likely in patients with remaining pockets.

Another possible explanation for the recurrence of periodontal disease is the microscopic nature of the dentogingival unit healing after periodontal treatment. Histologic studies have shown that after periodontal procedures, tissues usually do not heal by formation of new connective tissue attachment to root surfaces14,57,58 but result in a long junctional epithelium. It has been speculated that this type of dentogingival unit may be weaker and that inflammation may rapidly separate the long junctional epithelium from the tooth. Thus treated periodontal patients may be predisposed to recurrent pocket formation if maintenance care is not optimal.

Subgingival scaling alters the microflora of periodontal pockets.38,45,55 In one study, a single session of scaling and root planing in patients with chronic periodontitis resulted in significant changes in subgingival microflora.38 Reported alterations included a decrease in the proportion of motile rods for 1 week, a marked elevation in the proportion of coccoid cells for 21 days, and a marked reduction in the proportion of spirochetes for 7 weeks.

Although pocket debridement suppresses components of the subgingival microflora associated with periodontitis, periodontal pathogens may return to baseline levels within days or months.3,54 The return of pathogens to pretreatment levels generally occurs in approximately 9 to 11 weeks but can vary dramatically among patients.3

Both the mechanical debridement performed by the therapist and the motivational environment provided by the appointment seem to be necessary for good maintenance results. Patients tend to reduce their oral hygiene efforts between appointments.7,71 Knowing that their hygiene will be evaluated motivates them to perform better oral hygiene in anticipation of the appointment.

In one study the proportion of spirochetes obtained in baseline samples of subgingival flora was highly correlated with clinical periodontal deterioration over 1 year.31 However, subsequent reports in the same longitudinal study concluded that the arbitrary assignment of treated periodontitis patients to 3-month maintenance intervals appears to be as effective in preventing recurrences of periodontitis as assignment of recall intervals based on microscopic monitoring of the subgingival flora.31,32 Microscopic monitoring was found not to be a reliable predictor of future periodontal destruction in patients on 3-month recall programs, presumably because of the alteration of subgingival flora produced by subgingival instrumentation.

In conclusion, there is a sound scientific basis for recall maintenance because subgingival scaling alters the pocket microflora for variable but relatively long periods.

Maintenance Program

Periodic recall visits form the foundation of a meaningful long-term prevention program. The interval between visits is initially set at 3 months but may be varied according to the patient’s needs.

Periodontal care at each recall visit comprises three parts (Box 78-1). The first part involves examination and evaluation of the patient’s current oral health. The second part includes the necessary maintenance treatment and oral hygiene reinforcement. The third part involves scheduling the patient for the next recall appointment, additional periodontal treatment, or restorative dental procedures. The time required for a recall visit for patients with multiple teeth in both arches is approximately 1 hour,49 which includes time for greeting the patient, setting up, and cleaning up.

Examination and Evaluation

The recall examination is similar to the initial evaluation of the patient (see Chapter 30). However, because the patient is not new to the office, the dentist primarily looks for changes that have occurred since the last evaluation. Analysis of the current oral hygiene status of the patient is essential. Updating of changes in the medical history and evaluation of restorations, caries, prostheses, occlusion, tooth mobility, gingival status, and periodontal and periimplant probing depths are important parts of the recall appointment. The oral mucosa should be carefully inspected for pathologic conditions (Figures 78-4 to 78-9).

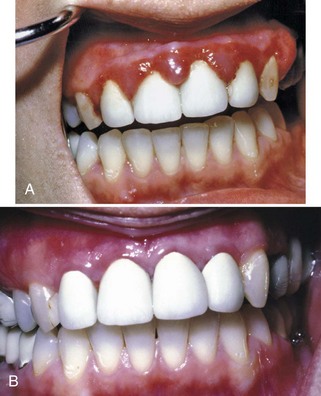

Figure 78-4 A, Hyperplastic gingivitis related to crown margins and plaque accumulation in a 27-year-old woman. B, Four months after treatment, there is significant improvement. However, some inflammation around crown margins still exists, which cannot be resolved without replacing the crowns.

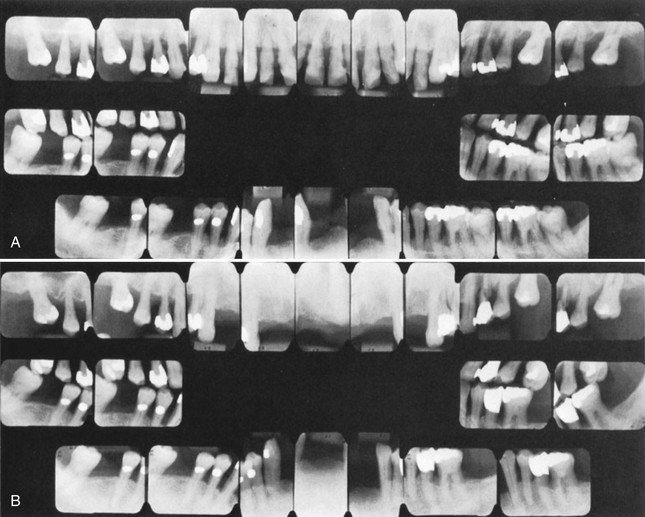

Figure 78-5 A, Patient was 38 years old when these original radiographs were taken and was treated with a combination of surgical and nonsurgical therapy. This individual is a classic class C maintenance patient. B, Pretreatment photograph. Note the inflammation and heavy calculus deposits. C, Photograph taken 10 years after treatment. D, Radiographs taken 5 years after treatment. E, Radiographs taken 10 years after treatment. The radiographic appearance is as good as can be expected in such a severe case. Teeth #15 and #17 were extracted 8 years after treatment.

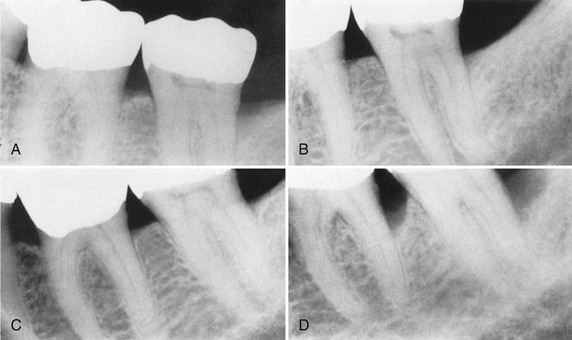

Figure 78-6 This series of radiographs clearly shows the importance of maintenance therapy. A, Original radiograph of a 58-year-old male. Note the deep distal bone loss on tooth #18 and the moderate distal lesion of tooth #19. Surgical treatment included osseous grafting. B, Radiograph 14 months after surgical therapy. The patient had recall maintenance performed every 3 to 4 months. C, Appearance 3 years after surgery, with regular recalls every 3 to 4 months. D, Appearance after 2 years without recalls (7 years after surgery). Note the progression of the disease on the distal surfaces of teeth #18 and #19.

Figure 78-7 Advanced cases sometimes do better than expected when the patient complies with maintenance therapy. A, Initial radiographs showing a very advanced case. The maxillary arch had extractions and nonsurgical treatment. A plastic partial denture was placed and was expected to grow into a full denture within a few years. The mandibular arch was treated with periodontal surgery, and a permanent, metal and plastic, removable partial denture was placed. B, Radiographs taken 8 years later. The patient performed good oral hygiene and had 3-month recalls. Teeth #12 and #15 required extraction.

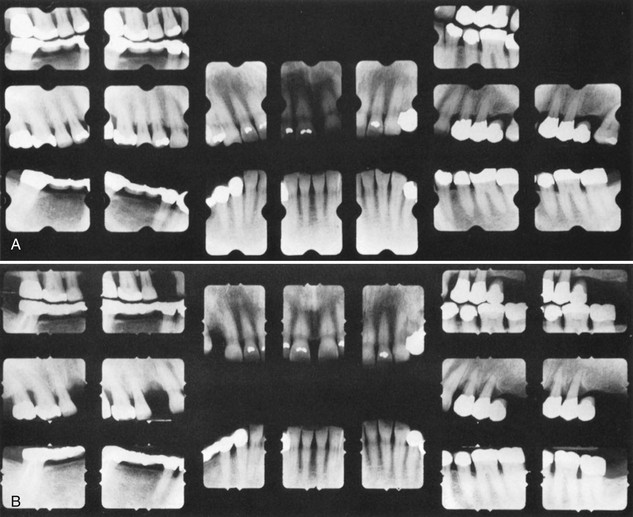

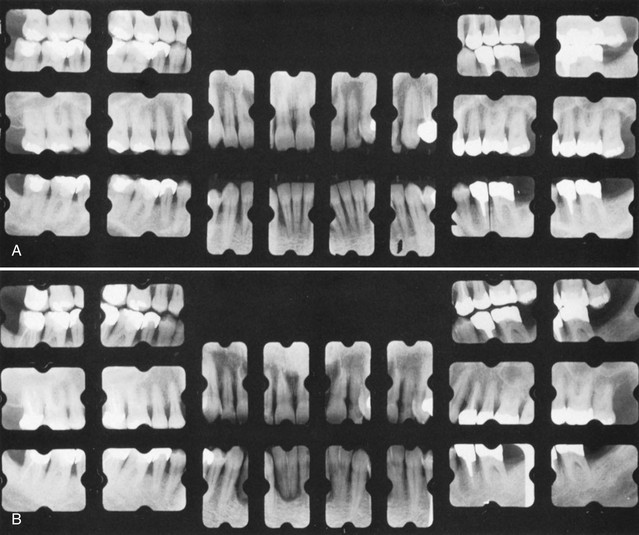

Figure 78-8 A, Initial radiographs. The patient was advised to have localized areas of periodontal surgery and periodontal recall every 3 months. However, the patient did not comply and only had dental cleanings once or twice yearly. B, Radiographs 4 years later. Note the loss of teeth #5 and #15 and the increased bone loss of several premolars and molars.

Figure 78-9 A, Initial radiographs. The patient was advised to have localized areas of periodontal surgery and periodontal recall every 3 months. However, the patient did not comply and had no treatment other than emergency care and occasional dental cleanings. B, Radiographs 7 years later. Note the advanced bone loss and caries on many teeth.

Radiographic examination must be individualized,5 depending on the initial severity of the case and the findings at the recall visit (Table 78-1). These are compared with findings on previous radiographs to check the bone height and look for repair of osseous defects, signs of trauma from occlusion, periapical pathologic changes, and caries.

TABLE 78-1 Radiographic Examination of Recall Patients for Supportive Periodontal Treatment*

| Patient Condition/Situation | Type of Examination |

|---|---|

| Clinical caries or high-risk factors for caries. | Posterior bite-wing examination at 12- to 18-month intervals. |

| Clinical caries and no high-risk factors for caries. | Posterior bite-wing examination at 24- to 36-month intervals. |

| Periodontal disease not under good control. | Periapical and/or vertical bite-wing radiographs of problem areas every 12 to 24 months; full-mouth series every 3 to 5 years. |

| History of periodontal treatment with disease under good control. | Bite-wing examination every 24 to 36 months; full-mouth series every 5 years. |

| Root form dental implants. | Periapical or vertical bite-wing radiographs at 6, 12, and 36 months after prosthetic placement, then every 36 months unless clinical problems arise. |

| Transfer of periodontal or implant maintenance patients. | Full-mouth series if a current set is not available. If full-mouth series has been taken within 24 months, radiographs of implants and periodontal problem areas should be taken. |

* Radiographs should be taken when they are likely to affect diagnosis and patient treatment. The recommendations in this table are subject to clinical judgment and may not apply to every patient.

Data from Matteson SR, Bottomley W, Finger H, et al: The selection of patients for x-ray examinations: dental radiographic examinations, DHHS Pub No FDA 88-8273, Washington, DC, 1987, US Department of Health and Human Services; and Wilson TG: J Am Dent Assoc 121:491, 1990.

Checking of Plaque Control

To assess the effectiveness of their plaque control, patients should perform their hygiene regimen immediately before the recall appointment. Plaque control must be reviewed and corrected until the patient demonstrates the necessary proficiency, even if additional instruction sessions are required. Patients instructed in plaque control have less plaque and gingivitis than uninstructed patients,7,61,62 and the amount of supragingival plaque affects the number of subgingival anaerobic organisms.19,56

Treatment

The required scaling and root planing are performed, followed by an oral prophylaxis (see Chapter 45). Care must be taken not to instrument normal sites with shallow sulci (1 to 3 mm deep) because studies have shown that repeated subgingival scaling and root planing in initially normal periodontal sites result in significant loss of attachment.29 Irrigation with antimicrobial agents or placement of site-specific antimicrobial devices is performed in maintenance patients with remaining pockets.3,30,34,49

Recurrence of Periodontal Disease

Occasionally, lesions may recur, which often can be traced to inadequate plaque control on the part of the patient or failure to comply with recommended SPT schedules. It should be understood, however, that it is the dentist’s responsibility to teach, motivate, and control the patient’s oral hygiene technique, and the patient’s failure is the dentist’s failure. Surgery should not be undertaken unless the patient has shown proficiency and willingness to cooperate by adequately performing his or her part of therapy.10,59,70

Other causes for recurrence include the following:

A failing case can be recognized by the following:

Cases that do not respond to adequate therapy or recur for unknown reasons are referred to as aggressive periodontitis (see Chapters 18 and 40).

The decision to re-treat a periodontal patient should not be made at the preventive maintenance appointment but should be postponed for 1 to 2 weeks.15 Often the mouth looks much better at that time because of the resolution of edema and the resulting improved tone of the gingiva. Table 78-2 summarizes the symptoms of recurrence of periodontal disease and their probable causes.

TABLE 78-2 Symptoms and Causes of Recurrence of Disease

| Symptom | Possible Causes |

|---|---|

| Increased mobility | Increased inflammation Poor oral hygiene Subgingival calculus Inadequate restorations Deteriorating or poorly designed prostheses Systemic disease modifying host response to plaque |

| Recession | Toothbrush abrasion Inadequate keratinized gingiva Frenum pull Orthodontic therapy |

| Increased mobility with no change in pocket depth and no radiographic change | Occlusal trauma caused by lateral occlusal interference, bruxism, high restoration Poorly designed or worn-out prosthesis Poor crown-to-root ratio |

| Increased pocket depth with no radiographic change | Poor oral hygiene Infrequent recall visits Subgingival calculus Poorly fitting partial denture Mesial inclination into edentulous space Failure of new attachment surgery Cracked teeth Grooves in teeth New periodontal disease Gingival overgrowth caused by medication |

| Increased pocket depth with increased radiographic bone loss | Poor oral hygiene Subgingival calculus Infrequent recall visits Inadequate or deteriorating restorations Poorly designed prostheses Inadequate surgery Systemic disease modifying host response to plaque Cracked teeth Grooves in teeth New periodontal disease |

Classification of Posttreatment Patients

The first year after periodontal therapy is important in terms of indoctrinating the patient in a recall pattern and reinforcing oral hygiene techniques. In addition, it may take several months to evaluate accurately the results of some periodontal surgical procedures. Consequently, some areas may have to be re-treated because the results may not be optimal. Furthermore, the first-year patient often has etiologic factors that may have been overlooked and may be more amenable to treatment at this early stage. For these reasons, the recall interval for first-year patients should not be longer than 3 months.

The patients who are on a periodontal recall schedule are a varied group. Table 78-3 lists several categories of maintenance patients and a suggested recall interval for each. Patients can improve or may relapse to a different classification, with a reduction in or exacerbation of periodontal disease. When one dental arch is more involved than the other, the patient’s periodontal disease is classified by the arch with the worse condition.

TABLE 78-3 Recall Intervals for Various Classes of Recall Patients

| Merin Classification | Characteristics | Recall Interval |

|---|---|---|

| First year | First-year patient: routine therapy and uneventful healing. | 3 months |

| First-year patient: difficult case with complicated prosthesis, furcation involvement, poor crown-to-root ratios, or questionable patient cooperation. | 1-2 months | |

| Class A | Excellent results well maintained for 1 year or more. Patient displays good oral hygiene, minimal calculus, no occlusal problems, no complicated prostheses, no remaining pockets, and no teeth with less than 50% of alveolar bone remaining. |

6 months to 1 year |

| Class B | Generally good results maintained reasonably well for 1 year or more, but patient displays some of the following factors: |

3-4 months (decide on recall interval based on number and severity of negative factors) |

| Class C | Generally poor results after periodontal therapy and/or several negative factors from the following list: |

1-3 months (decide on recall interval based on number and severity of negative factors; consider re-treating some areas or extracting severely involved teeth) |

In summary, maintenance care is a critical phase of therapy. The long-term preservation of the dentition is closely associated with the frequency and quality of recall maintenance.

Referral of Patients to the Periodontist

Many periodontal patients can be well managed by the general dentist As more people retain their teeth throughout their lifetime and as the proportion of older people in the population increases, more teeth will be at risk of periodontal disease. Considerable research shows possible links between periodontal disease and systemic diseases, such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Therefore the prevalence of patients requiring SPT is likely to increase in the future.

This expected increase in the number of periodontal patients will necessitate a greater understanding of periodontal problems and an increased level of expertise for the solution of such problems on the part of the general practitioner of dentistry. General dentists must know when co-management with a periodontist is indicated. Specialists are needed to treat particularly difficult periodontal cases, patients with systemic health problems, dental implant patients, and those with a complex prosthetic construction that requires reliable results.

The question of where to draw the line between the cases to be treated in the general dental office and those to be referred to a specialist varies for different practitioners and patients, and the American Academy of Periodontology has issued guidelines to help the general practitioner decide when co-management with a periodontist is indicated.4 The diagnosis indicates the type of periodontal treatment required. If periodontal destruction necessitates surgery on the distal surfaces of second molars, extensive osseous surgery, or complex regenerative procedures, the patient is usually best treated by a specialist. On the other hand, patients who require localized gingivectomy or flap curettage usually can be treated by the general dentist.

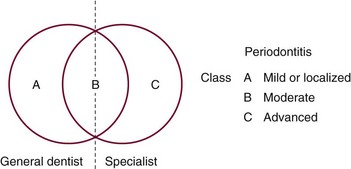

It is immediately obvious that some patients should be referred to a specialist, whereas most patients clearly have problems that can be treated by a general dentist. For a third group of patients, however, it will be difficult to decide whether treatment by a specialist is required. Any patient who does not clearly belong in the second of these categories should be considered a candidate for referral to a specialist.4,42

The decision to have the general practitioner treat a patient’s periodontal problem should be guided by a consideration of the degree of risk that the patient will lose a tooth or teeth for periodontally related reasons or the risk of the periodontal disease contributing to their general health problems.

The most important factors in the decision are the extent and location of the periodontal deterioration. Teeth with pockets of 5 mm or more, as measured from the cementoenamel junction, may have a prognosis of rapid decline. The location of the periodontal deterioration is also an important factor in determining the risk of tooth loss. Teeth with furcation lesions may be at risk even when more than 50% of bone support remains. Therefore patients with strategically important teeth that fall into these categories are usually best treated by specialists.

An important question remains: Should the maintenance phase of therapy be performed by the general practitioner or the specialist? This should be determined by the amount of periodontal deterioration present. Class A recall patients should be maintained by the general dentist, whereas Class C patients should be maintained by the specialist (see Table 78-3). Class B patients can alternate recall visits between the general practitioner and the specialist (Figure 78-10). The suggested rule is that the patient’s disease should dictate whether the general practitioner or the specialist should perform the maintenance therapy.

Tests for Disease Activity

Periodontal patients, even though they have received effective periodontal therapy, are at risk of disease recurrence for the rest of their lives.25,26 In addition, many pockets in furcation areas may not have been eliminated by surgery. At present, the best way of determining areas that are losing attachment is to use a well-organized charting system.47,68 Some computerized systems allow easy retrieval and comparison of past findings.

Comparison of sequential probing measurements gives the most accurate indication of the rate of loss of attachment.6 A number of other clinical and laboratory variables have been correlated with disease activity.

At present, no accurate method of predicting disease activity exists, and clinicians rely on the information provided by combining probing, bleeding on probing, and sequential attachment measurements.28,32,68 Patients whose disease is clearly refractory are candidates for bacterial culturing and antibiotic therapy in conjunction with additional mechanical therapy.

New methods will undoubtedly be developed in the future to help predict disease activity.3 The clinician must be able to interpret whether a test may be useful in determining disease activity and future loss of attachment.11 Tests should be adopted only when they are based on research that includes a critical analysis of the sensitivity, specificity, disease incidence, and predictive value of the proposed test.

Maintenance for Dental Implant Patients

Patients with implants are susceptible to a form of bone loss called periimplantitis, and evidence suggests that such patients may be more prone to plaque-induced inflammation with bone loss than those with natural teeth9,50,53,65 (see Chapter 77). Patients with periodontitis-associated tooth loss are at significantly increased risk of developing periimplantitis.51,52

The overall periodontal condition in partially edentulous implant patients can influence the clinical condition around implants.12 The microflora of implants in partially edentulous patients differs from that in edentulous patients.8 The implant microflora is similar to tooth microflora in the partially edentulous mouth. Periodontal and implant maintenance are linked because maintenance of a tooth microflora consistent with periodontal health is necessary to maintain implant microflora consistent with periimplant health.8,60 Because periimplantitis is difficult to treat,24 it is extremely important to treat periodontal disease before implant placement and to provide good supportive therapy with implant patients.

In general, procedures for maintenance of patients with implants are similar to those for patients with natural teeth,3,21,27,36 with the following three differences:

During the phase after uncovering the implants, patients must use ultrasoft brushes, chemotherapeutic rinses, tartar control pastes, irrigation devices, and yarnlike materials to keep the implants and natural teeth clean. Patients often are reluctant to touch the implants but must be encouraged to keep the areas clean.

Special instruments should be used on the implants during recall appointments.21,36 Metal hand instruments and ultrasonic and sonic tips should be avoided because they can alter the titanium surface.22 Only plastic instruments or specially designed gold-plated curettes should be used for calculus removal because the implant surfaces can be easily scratched. The rubber cup with flour of pumice, tin oxide, or special implant-polishing pastes should be used on abutment surfaces with light, intermittent pressure.35

Although daily use of topically applied antimicrobials is advised,36 acidic fluoride agents should not be used because they cause surface damage to titanium abutments.44

When prosthetics must be unscrewed and removed for maintenance, it is best done in the office responsible for placing the prosthetics. Each time the prosthetic appliances are reattached, a slight change in the occlusion occurs. Time must be allowed for occlusal corrections.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

The most important factor that determines the long-term success of periodontal therapy is plaque control. No matter how skillful the surgeon, the initial postsurgical improvement of periodontal status quickly deteriorates if bacterial plaque deposition is not controlled. Patients with a history of periodontal disease should be seen for plaque control and any needed recall root planing at least every 3 or 4 months. All patients should have their plaque score monitored, and oral hygiene instruction should be upgraded when plaque scores increase. The use of antibacterial mouthwashes, such as chlorhexidine, on the toothbrush two to three times daily augments mechanical plaque removal and is an important adjunct to supportive periodontal treatment.

All patients need to have an ongoing recording of pocket depth, recession, and plaque status to detect any periodontal deterioration in its early stages so that appropriate treatment measures can be given.

1 Ainamo J, Ainamo A. Risk assessment of recurrence of disease during supportive periodontal care. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:232.

2 Alaluusua S, Asikainen S, Lai CH. Intrafamilial transmission of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Periodontol. 1991;62:207.

3 American Academy of Periodontology. Position paper: Periodontal maintenance. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1395.

4 American Academy of Periodontology. Academy Report: Guidelines for the management of patients with periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1608.

5 American Dental Association, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The selection of patients for dental radiograph examinations. www.ada.org, November 2004. Available on

6 Armitage GC. Diagnosing periodontal diseases. In: Perspectives on oral antimicrobial therapeutics. Littleton, Mass: PSG Publishing; 1987.

7 Axelson P, Lindhe J. The significance of maintenance care in the treatment of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1981;8:281.

8 Bauman GR, Mills M, Rapley JW, et al. Plaque-induced inflammation around implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1992;7:330.

9 Bauman GR, Rapley JW, Hallmon WW, et al. The peri-implant sulcus. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1993;8:273.

10 Becker W, Becker BE, Berg LE. Periodontal treatment without maintenance: a retrospective study in 44 patients. J Periodontol. 1984;155:505.

11 Bennett WI. Screening for bowel cancer. Harvard Med School Health Lett. 1986;11:6.

12 Bragger U, Burgin WB, Hammerle CH, et al. Associations between clinical parameters assessed around implants and teeth. Clin Oral Implant Res. 1997;8:412.

13 Carranza FAJr, Saglie FR, Newman MG, et al. Scanning and transmission electron microscope study of tissue invading microorganisms in localized juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1983;54:598.

14 Caton JG, Zander HA. The attachment between tooth and gingival tissues after periodic root planing and soft tissue curettage. J Periodontol. 1979;50:462.

15 Chace R. Retreatment in periodontal practice. J Periodontol. 1977;48:410.

16 Checchi L, Montevecchi M, Gatto MR, Trombelli L. Retrospective study of tooth loss in 92 periodontal patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:651.

17 Christersson LA, Albini B, Zambon JJ, et al. Tissue localization of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontitis. I. Light, immunofluorescence and electron microscopic studies. J Periodontol. 1987;58:529.

18 Cortellimi P, Pini-Prato G, Torretti M. Periodontal regeneration of human infrabony defects. V. Effects of oral hygiene on long-term stability. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:606.

19 Dahlen G, Lindhe J, Sato K, et al. The effect of supragingival plaque control on the subgingival microbiota in subjects with periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:802.

20 Egloff E, Saglie FR, Newman MG. Intragingival bacteria subsequent to scaling and root planing. J Dent Res. 1986;65:269. (abstract)

21 Eskow RN, Smith VS. Preventive periimplant protocol. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1999;20:137.

22 Fox SC, Moriarty JD, Kusy RP. The effects of scaling a titanium implant surface with metal and plastic instruments: an in vitro study. J Periodontol. 1990;61:485.

23 Greenwell H, Bissada NB, Wittwer JW. Periodontics in general practice: perspectives on periodontal diagnosis. J Am Dent Assoc. 1989;119:537.

24 Grunder U, Hürzeler MB, Schüpbach P, et al. Treatment of ligature-induced peri-implantitis using guided tissue regeneration: a clinical and histologic study in the beagle dog. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1993;8:282.

25 Halazonetis TD, Smulow JB, Donnenfeld W, et al. Pocket formation 3 years after comprehensive periodontal therapy: a retrospective study. J Periodontol. 1985;56:515.

26 Hirschfeld L, Wasserman B. A long-term survey of tooth loss in 600 treated periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 1978;49:225.

27 Lang NP, Nyman SR. Supportive maintenance care for patients with implants and advanced restorative therapy. Periodontol 2000. 1994;4:119.

28 Lang NP, Joss A, Orsanic T, et al. Bleeding on probing. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:590.

29 Lindhe J, Nyman S, Karring T. Scaling and root planing in shallow pockets. J Clin Periodontol. 1982;9:415.

30 Lindhe J, Heijl L, Goodson JM, et al. Local tetracycline delivery using hollow fiber devices in periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1979;6:141.

31 Listgarten MA, Hellden L. Relative distribution of bacteria at clinically healthy and periodontally diseased sites in humans. J Clin Periodontol. 1978;5:115.

32 Listgarten MA, Schifter CC, Sullivan P, et al. Failure of a microbiological assay to reliably predict disease recurrence in a treated periodontitis population receiving regularly scheduled prophylaxes. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:768.

33 Listgarten MA, Sullivan P, George C, et al. Comparative longitudinal study of 2 methods of scheduling maintenance visit: 4-year data. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:105.

34 Mazza JE, Newman MG, Sims TN. Clinical and antimicrobial effect of stannous fluoride on periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1981;8:213.

35 McCollum J, O’Neal RB, Brennan WA, et al. The effect of titanium implant abutment surface irregularities on plaque accumulation in vivo. J Periodontol. 1992;63:802.

36 Meffert RM, Langer B, Fritz ME. Dental implants: a review. J Periodontol. 1992;63:859.

37 Mendoza AR, Newcomb GM, Nixon KC. Compliance with supportive periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1991;62:731.

38 Mousques T, Listgarten MA, Phillips RW. Effect of scaling and root planing on the composition of human subgingival microflora. J Periodontal Res. 1980;15:144.

39 Novaes ABJr, Novaes AB. Compliance with supportive periodontal therapy. Part 1. Risk of non-compliance in the first 5-year period. J Periodontol. 1999;70:679.

40 Novaes ABJr, Novaes AB. Compliance with supportive periodontal therapy. Part II. Braz Dent J. 2001;12:47.

41 Oliver RC. Tooth loss with and without periodontal therapy. Periodont Abstracts. 1969;17:8.

42 Parr RW, Pipe P, Watts T. Periodontal maintenance therapy. Berkeley, Calif: Praxis; 1974.

43 Pertuiset JH, Saglie FR, Lofthus J, et al. Recurrent periodontal disease and bacterial presence in the gingiva. J Periodontol. 1987;58:553.

44 Probster L, Lin W, Juttemann H. Effect of fluoride prophylactic agents on titanium surfaces. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1992;7:390.

45 Rosenberg ES, Evian CI, Listgarten MA. The composition of the subgingival microbiota after periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1981;52:435.

46 Ross IF, Thompson RH, Galdi M. The results of treatment: a long-term study of 180 patients. Parodontologie. 1971;25:125.

47 Ryan RJ. The accuracy of clinical parameters in detecting periodontal disease activity. J Am Dent Assoc. 1985;111:753.

48 Saglie FR, Newman MG, Carranza FAJr, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in sections of gingival tissue in localized juvenile periodontitis. Acta Odont Lat Am. 1984;1:40.

49 Schallhorn RG, Snider LE. Periodontal maintenance therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 1981;103:227.

50 Schou S, Holmstrup P, Reibel J, et al. Ligature-induced marginal inflammation around osseointegrated implants and ankylosed teeth: stereologic and histologic observations on cynomolgus monkeys. J Periodontol. 1993;64:529.

51 Schou S, Holmstrup P, Worthington HV, Esposito M. Outcome of implant therapy in patients with previous tooth loss due to periodontitis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;2:104.

52 Schou S. Implant treatment in periodonitits-susceptible patients: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;1:9.

53 Serino G, Strom C. Peri-implantitis in partially edentulous patients: association with inadequate plaque control. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20:169.

54 Shiloah J, Patters MR. Repopulation of periodontal pockets by microbial pathogens in the absence of supportive therapy. J Periodontol. 1996;67:130.

55 Slots J, Mashimo P, Levine MJ, et al. Periodontal therapy in humans. I. Microbiological and clinical effects of a single course of periodontal scaling and root planing, and of adjunctive tetracycline therapy. J Periodontol. 1979;50:495.

56 Smulow JB, Turesky SS, Hill RG. The effect of supragingival plaque removal on anaerobic bacteria in deep pockets. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;107:737.

57 Stahl SS. Repair potential of the soft tissue-root interface. J Periodontol. 1977;48:545.

58 Stahl SS, Witkin GJ, Heller A, et al. Gingival healing. IV. The effects of home care on gingivectomy repair. J Periodontol. 1969;40:264.

59 Sternlich HC. Evaluating long-term periodontal therapy. Texas Dent J. 1974;92:4.

60 Sumida S, Ishihara K, Kishi M, Okuda K. Transmission of periodontal disease-associated bacteria from teeth to osseointegrated implant regions. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2002;17:696.

61 Suomi JD, Greene JC, Vermillion JR, et al. The effect of controlled oral hygiene procedures on the progression of periodontal disease in adults: results after the third and final year. J Periodontol. 1971;42:152.

62 Suomi JD, West JD, Chang JJ, et al. The effect of controlled oral hygiene procedures on the progression of periodontal disease in adults: radiographic findings. J Periodontol. 1971;42:562.

63 Tonetti MA, Muller-Campanile V, Lang NP. Changes in the prevalence of residual pockets and tooth loss in treated periodontal patients during a supportive maintenance care program. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:1008.

64 van Steenbergen TJ, Petit MD, van der Velden U, et al. Transmission of Porphyromonas gingivalis between spouses. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:340.

65 van Steenberghe D, Klinge B, Linden U, et al. Periodontal indices around natural and titanium abutments: a longitudinal multicenter study. J Periodontol. 1993;64:538.

66 Waerhaug J. Healing of the dentoepithelial junction following subgingival plaque control. J Periodontol. 1978;49:119.

67 Wilson TG. Maintaining periodontal treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;121:491.

68 Wilson TG, Kornman KS. Retreatment. Periodontol 2000. 1996;12:119.

69 Wilson TGJr. Compliance: a review of the literature. J Periodontol. 1987;58:706.

70 Wilson TGJr, Glover ME, Malik AK, et al. Tooth loss in maintenance patients in a private periodontal practice. J Periodontol. 1987;58:231.

71 Wilson TGJr, Glover ME, Schoen J, et al. Compliance with maintenance therapy in a private periodontal practice. J Periodontol. 1984;55:468.