CHAPTER 40 Treatment of Aggressive and Atypical Forms of Periodontitis

The majority of patients with common forms of periodontal disease respond predictably well to conventional therapy, including oral hygiene instruction, nonsurgical debridement, surgery, and supportive periodontal maintenance. However, patients diagnosed with aggressive and some atypical forms of periodontal disease often do not respond as predictably or as favorably to conventional therapy. Fortunately, only a small percentage of patients with periodontal disease are diagnosed with aggressive periodontitis. Patients who are diagnosed with periodontal disease (any type) that is refractory to treatment present in small numbers as well. Even fewer patients are diagnosed with necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis. Each of these atypical disease entities poses significant challenges for the clinician not only because they are infrequently encountered, but also because they may not respond favorably to conventional periodontal therapy.27,45 Furthermore, the severe loss of periodontal support associated with these cases leaves the clinician faced with uncertainty about treatment outcomes and difficulty in making decisions about whether to save compromised teeth or to extract them.

This chapter outlines important considerations for the treatment of patients diagnosed with aggressive periodontitis and atypical forms of periodontal disease, including refractory cases of periodontitis and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis.

Aggressive Periodontitis

Aggressive periodontitis, by definition, causes rapid destruction of the periodontal attachment apparatus and the supporting alveolar bone (see Chapter 18). The responsiveness of aggressive periodontitis to conventional periodontal treatment is unpredictable, and the overall prognosis for these patients is poorer than for patients with chronic periodontitis. Because these patients do not respond “normally” to conventional methods and their disease progresses unusually fast, the logical question is whether there are problems associated with an impaired host immune response that may contribute to such a different disease and result in a limited response to the usual therapeutic measures. Indeed, defects in polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN, neutrophil) function have been identified in some patients with aggressive periodontitis.34,36 Also, in a small number of cases, a systemic disease, such as neutropenia, can be identified that clearly explains the unusual severity of the periodontal disease for that individual.14,15 In most patients with aggressive periodontitis, however, systemic diseases or disorders cannot be identified. In fact, the irony is that these patients are typically quite healthy. Numerous attempts to examine immunologic profiles in patients with aggressive periodontitis have failed to identify any specific etiologic factors common to all patients.

The prognosis for patients with aggressive periodontitis depends on (1) whether the disease is generalized or localized, (2) the degree of destruction present at the time of diagnosis, and (3) the ability to control future progression. Generalized aggressive periodontitis rarely undergoes spontaneous remission, whereas localized forms of the disease have been known to arrest spontaneously.33 This unexplained curtailment of disease progression has sometimes been referred to as a “burnout” of the disease. It appears that cases of localized aggressive periodontitis often have a limited period of rapid periodontal attachment and alveolar bone loss, followed by a slower, more chronic phase of disease progression. Overall, patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis tend to have a poorer prognosis because they typically have more teeth affected by the disease and because the disease is less likely to go spontaneously into remission compared with patients with localized forms of aggressive periodontitis.

Therapeutic Modalities

Early detection is critically important in the treatment of aggressive periodontitis (generalized or localized) because preventing further destruction is often more predictable than attempting to regenerate lost supporting tissues. Therefore, at the initial diagnosis, it is helpful to obtain any previously taken radiographs to assess the rate of progression of the disease. Together with future radiographs, this documentation will also facilitate the clinician’s assessment of treatment success and control of the disease.

Treatment of aggressive periodontitis must be pursued with a logical and regimented approach. Several aspects of treatment must be particularly considered when managing a patient with aggressive periodontitis. One of the most important aspects of treatment success is to educate the patient about the disease, including the causes and the risk factors for disease, and to stress the importance of the patient’s role in the success of treatment.1 Essential therapeutic considerations for the clinician are to control the infection, arrest disease progression, correct anatomic defects, replace missing teeth, and ultimately help the patient maintain periodontal health with frequent periodontal maintenance care. Educating family members is another important factor because aggressive periodontitis is known to have familial aggregation. Thus family members, especially younger siblings, of the patient diagnosed with aggressive periodontitis should be examined for signs of disease, educated about preventive measures, and monitored closely. It cannot be stressed enough that early diagnosis, intervention, and if possible, prevention of disease are more desirable than attempting to reverse the destruction that results from aggressive periodontitis.

Many different treatment approaches have been used to manage patients with aggressive periodontitis, including nonsurgical, surgical, and antimicrobial therapy. Recent advances in our understanding of the role of the host response in disease pathogenesis are leading to new opportunities for treatment. The advantages and limitations of conventional, antimicrobial, and combination therapy for the treatment of aggressive periodontitis, as well as restorative considerations are discussed next.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

Treatment of Aggressive and Atypical Forms of Periodontitis

There is a small group of patients that develops aggressive periodontal diseases. In a few of these cases, this is related to specific systemic diseases that affect the immune system, e.g., neutropenia, polymorphonuclear leukocyte dysfunction, and diabetes. However, in most of those patients, it is not possible to identify the reason why such dramatic periodontal disease occurred, and so comprehensive blood tests at present are unlikely to identify the problem. The treatment approach to these patients follows the same rationale of treatment used for regular periodontitis patients, i.e., initial therapy, followed by periodontal surgery and maintenance care. In general, these patients will respond to treatment, particularly those patients that develop aggressive periodontitis as adolescents in whom often the disease activity diminishes once they reach their twenties. All available adjunctive therapy should accompany these patients including systemic antibiotics, localized antimicrobial rinses such as chlorhexidine, and the use of host modulation therapy. The latter of these may in the future provide increased therapeutic success as new protocols and agents become available. These patients can be treated with dental implants without concern for dramatic increases in risk of failure.

Another group of atypical patients is those that are refractory to treatment, which includes patients with high plaque scores, smokers, and poorly controlled diabetics. These patients similarly require the comprehensive use of all available treatment modalities and many can be helped by including systemic antibiotics such as metronidazole and amoxicillin with potassium clavulanate.

All of the patients outlined in this chapter require maintenance programs with strict monitoring of plaque scores and high-frequency recall appointments (at least one every 3 months.)

Conventional Periodontal Therapy

Conventional periodontal therapy for aggressive periodontitis consists of patient education, oral hygiene improvement, scaling and root planing, and regular (frequent) recall maintenance. It may or may not include periodontal flap surgery.4,64 Unfortunately, the response of aggressive periodontitis to conventional therapy alone has been limited and unpredictable. Patients who are diagnosed with aggressive periodontitis at an early stage and who are able to enter therapy may have a better outcome than those who are diagnosed at an advanced stage of destruction. In general, the earlier the disease is diagnosed, the more conservative the therapy and the more predictable the outcome.

Teeth with moderate to advanced periodontal attachment loss and bone loss often have a poor prognosis and pose the most difficult challenge. Depending on the condition of the remaining dentition, treatment of these teeth may have a limited prospect for improvement and may even diminish the overall treatment success for the patient. Clearly, some of these teeth should be extracted; however, other teeth may be pivotal to the stability of that individual’s dentition, and thus it may be desirable to attempt treatment to maintain them. Treatment options for teeth with deep periodontal pockets and bone loss may be nonsurgical or surgical. Surgery may be purely resective, regenerative, or a combination of these approaches.

Surgical Resective Therapy

Resective periodontal surgery can be effective to reduce or eliminate pocket depth in patients with aggressive periodontitis. However, it may be difficult to accomplish if adjacent teeth are unaffected, as often seen in cases of localized aggressive periodontitis. If a significant height discrepancy exists between the periodontal support of the affected tooth and the adjacent unaffected tooth, the gingival transition (following the bone) will often result in deep probing pocket depth around the affected tooth despite surgical efforts. A less-than-ideal outcome must be taken into consideration before deciding to treat increased pocket depth surgically.

It is important to realize the limitations of surgical therapy and to appreciate the possible risk that surgical therapy may further compromise teeth that are mobile because of extensive loss of periodontal support. For example, in a patient with severe horizontal bone loss, surgical resective therapy may result in increased tooth mobility that is difficult to manage, and a nonsurgical approach may be indicated. Therefore careful evaluation of the risks versus the benefits of surgery must be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Regenerative Therapy

The concept and application of periodontal regeneration has been established in patients with chronic forms of periodontal disease (see Chapter 61). The use of regenerative materials, including bone grafts, barrier membranes, and wound-healing agents, are well documented and often used. Intrabony defects, particularly vertical defects with multiple osseous walls, are often amenable to regeneration with these techniques. Most of the success and predictability of periodontal regeneration have been achieved in patients with chronic periodontitis; much less evidence is available about the use of periodontal regeneration for patients with aggressive periodontitis.

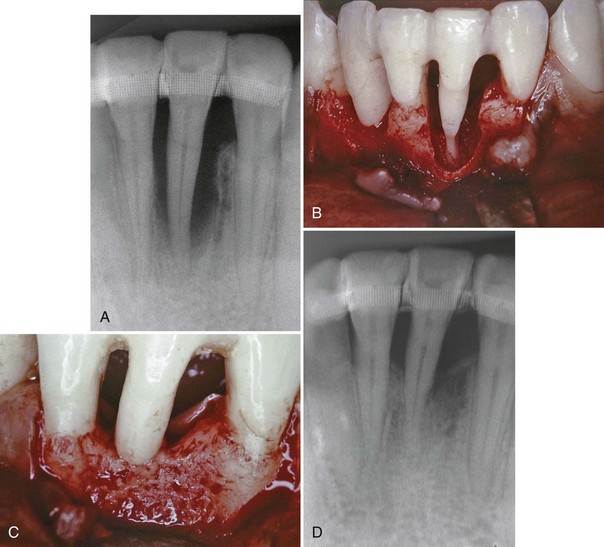

Periodontal regenerative procedures have been successfully demonstrated in patients with localized aggressive periodontitis in some clinical case reports. Dodson et al16 demonstrated the regenerative potential of a severe, localized osseous defect around a mandibular incisor in a healthy, 19-year-old black man diagnosed with localized aggressive periodontitis. The patient presented with severe bone loss localized around one of the mandibular incisors. Using open-flap surgical debridement, root surface conditioning (tetracycline solution), and an allogenic bone graft reconstituted with sterile saline and tetracycline powder, the surgeons reduced the probing pocket depth from 9 to 12 mm down to 1 to 3 mm (3 mm of recession was noted), and significant bone fill of the defect (about 80%) was reported (Figure 40-1). This case illustrates the potential for healing severe defects in patients with localized aggressive periodontitis, especially when local factors are controlled and sound surgical principles are followed. The authors cited several factors that likely contributed to the success of this case, including a probable transition of disease activity from aggressive to chronic, tooth stabilization before surgery, sound surgical management of hard and soft tissues, and good postoperative care.16

Figure 40-1 Clinical photographs and periapical radiographs demonstrating regenerative success in patient with localized aggressive periodontitis. A, Periapical radiograph of the right lateral incisor at the initial diagnosis. Notice the severe, vertical bone loss associated with the right lateral incisor. Tooth has been splinted to adjacent teeth for stability. B, Facial view of the circumferential osseous defect around the lower right lateral incisor during open flap surgery. There is complete loss of buccal, lingual, mesial, and distal bone around the lateral incisor, with minimal bone support limited to the apical few millimeters. C, Facial view of reentered surgical site 1 year after treatment. Bone fill around all surfaces demonstrates remarkable potential for regeneration of a large osseous defect in a young patient with localized aggressive periodontitis. D, Periapical radiograph taken 1 year after regenerative therapy. Note the increased radiopacity and bone fill.

(From Dodson SA, Takei HH, Carranza FA Jr: Int J Periodont Restor Dent 16:455, 1996.)

It is important to note that although the potential for regeneration in patients with aggressive periodontitis appears to be good, expectations are limited for patients with severe bone loss. Depending on the anatomy of the defect and teeth involved, the potential for bone fill and periodontal regeneration may be poor. This is especially true if the bone loss is horizontal and if it has progressed to involve furcations. The usual criteria of case selection and sound principles of surgical management for regenerative therapy apply equally to cases of aggressive periodontitis. Good clinical judgment must be used to determine whether a particular tooth should be treated with the goal of regeneration.

Recent advances in regenerative therapy have advocated the use of an enamel matrix protein to aid in the regeneration of cementum and new attachment in periodontal defects.67 A systematic review of the literature concluded that treatment with an enamel matrix protein can improve probing attachment level (mean difference, 1.3 mm) and probing pocket depth (mean difference, 1.0 mm) compared with flap debridement alone in patients with chronic periodontitis.17 However, no evidence has been reported to suggest significant advantages for the use of enamel matrix proteins in patients with aggressive periodontitis. One recent case report described use of the protein in a 15-year-old patient with localized aggressive periodontitis.8 No comparative sites were treated, so the effect that may be attributed to enamel matrix protein could not be determined. A recent clinical and radiographic study with a split-mouth design included four patients with aggressive periodontitis and four patients with chronic periodontitis. The authors concluded that enamel matrix proteins offered no advantage over surgical debridement alone in these patients.66 Although this study attempted to use controls to measure the effect of enamel matrix proteins, there were insufficient patients to appreciate a difference in outcome. At this time, it is unknown whether the use of enamel matrix proteins offers significant advantages for the patient with aggressive periodontitis.

Antimicrobial Therapy

The presence of periodontal pathogens, specifically Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, has been implicated as the reason that aggressive periodontitis does not respond to conventional therapy alone. These pathogens are known to remain in the tissues after therapy to reinfect the pocket.11,62 In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the identification of A. actinomycetemcomitans as a major culprit and the discovery that this organism penetrates the tissues offered another perspective to the pathogenesis of aggressive periodontitis and offered new hope for therapeutic success, namely, antibiotics.11 The use of systemic antibiotics was thought to be necessary to eliminate pathogenic bacteria (especially A. actinomycetemcomitans) from the tissues. Indeed, several authors have reported success in the treatment of aggressive periodontitis using antibiotics as adjuncts to standard therapy.38-4075

Systemic Administration of Antibiotics

There is compelling evidence that adjunctive antibiotic treatment frequently results in a more favorable clinical response than mechanical therapy alone.70 In a systematic review, Herrera et al26 found that systemic antimicrobials in conjunction with scaling and root planing offer benefits over scaling and planing alone in terms of clinical attachment level, probing pocket depth, and reduced risk of additional attachment loss. Patients with deeper, progressive pockets seem to benefit the most from systemic administration of adjunctive antibiotics. Many different antibiotic types and regimens were reviewed. Because of limitations in comparing data from different studies, however, definitive recommendations were not possible.

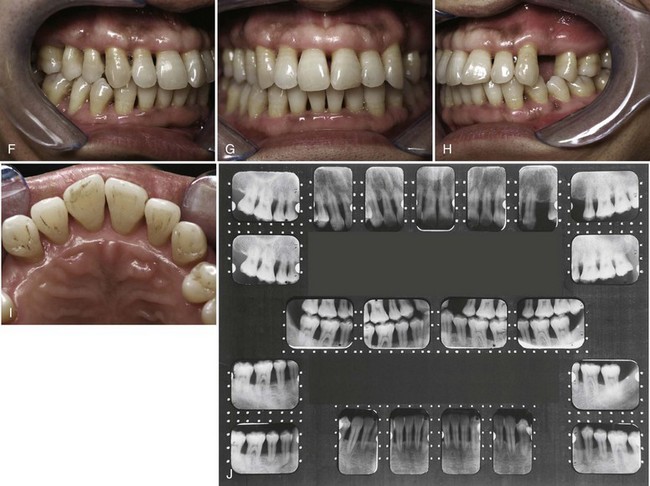

Figure 40-2 shows the before and after results of an aggressive periodontitis case treated nonsurgically with scaling and root planing and adjunctive antibiotic therapy. The patient, a 34-year-old Asian male, presented with a complaint of loose teeth and bleeding gums. He requested treatment to save his teeth. Treatment consisted of patient education including oral hygiene instructions and nonsurgical therapy with adjunctive antibiotics. All teeth were thoroughly scaled and root planed under local anesthesia over two treatment appointments, and the patient was treated with systemic amoxicillin (500 mg, 3 times a day for 2 weeks) during the period of treatment. All areas responded favorably with probing pocket depths decreasing from 3 to 13 mm down to 2 to 5 mm. Bleeding on probing diminished from generalized to very few isolated areas. He has been on periodontal maintenance with good results for more than 5 years.

Figure 40-2 Intraoral clinical photographs and full mouth radiographs (before and after treatment) of a 34-year-old Asian male with aggressive periodontitis. A to D, Intraoral clinical photographs of pretreatment periodontal condition. Note the gingival edema, inflammation and bleeding. Probing pocket depths ranged from 3 to 13 mm with generalized bleeding on probing and purulent exudate. E, Pretreatment full mouth radiographs demonstrating generalized severe horizontal bone loss. Note the periapical radiolucency at the apex of the upper left premolar indicating pulpal disease. F to I, Intraoral clinical photographs of posttreatment (5 years) results. Treatment included nonsurgical scaling and root planing along with adjunctive systemic antibiotics (amoxicillin). Patient improved oral hygiene and continued to be seen for professional maintenance every 3 months. Probing pocket depths have been maintained in the range of 2 to 5 mm with only a few localized areas of bleeding on probing. J, Posttreatment (5 years) full mouth radiographs demonstrating no additional bone loss. Note that the endodontically involved maxillary premolar was extracted. The missing tooth has been replaced with a removable partial denture.

Genco et al21 treated localized aggressive periodontitis patients with scaling and root planing plus systemic administration of tetracycline (250 mg, 4 times daily for 14 days every 8 weeks). Measurements of vertical defects were made at intervals of up to 18 months after the initiation of therapy. Bone loss had stopped, and one-third of the defects demonstrated an increase in bone level, whereas in the control group, bone loss continued.

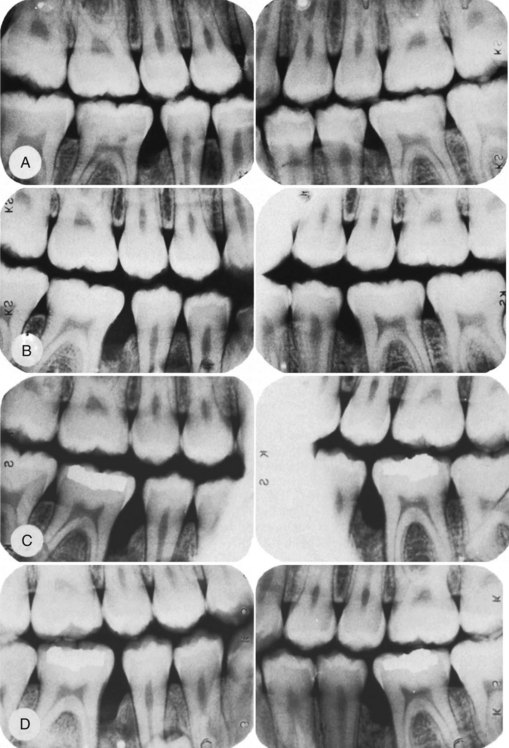

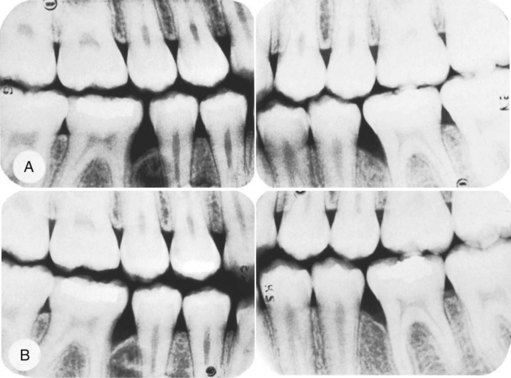

Liljenberg and Lindhe38 treated patients with localized aggressive periodontitis with systemic administration of tetracycline (250 mg, 4 times daily for 2 weeks), modified Widman flaps, and periodic recall visits (1 visit every month for 6 months, then 1 visit every 3 months). The lesions healed more rapidly and more completely than similar lesions in control patients. These investigators reevaluated their results after 5 years and found that the treatment group continued to demonstrate resolution of gingival inflammation, gain of clinical attachment, and refill of bone in angular defects.39 Figures 40-3 and 40-4 show radiographs of a case with similar treatment and results.5

Figure 40-3 Radiographs depicting progression of the osseous lesion in patient with localized aggressive periodontitis (formerly “localized juvenile periodontitis”). A, January 29, 1979; B, August 16, 1979; C, February 22, 1980; D, May 15, 1981. Note the progressive deterioration of the osseous level.

(From Barnett ML, Baker RL: J Periodontol 54:148, 1983.)

Figure 40-4 Postoperative radiographs of the patient in Figure 40-3. A, November 6, 1981; B, March 3, 1982. Treatment consisted of oral hygiene instruction, scaling and root planing concurrently with 1 g of tetracycline per day for 2 weeks, and modified Widman flaps.

(From Barnett ML, Baker RL: J Periodontol 54:148, 1983.)

Clearly, numerous studies support the use of adjunctive tetracycline along with mechanical debridement for the treatment of A. actinomycetemcomitans–associated aggressive periodontitis (Box 40-1). Given the possible emergence of tetracycline-resistant A. actinomycetemcomitans, there is concern that tetracycline may not be effective. In these cases the combination of metronidazole and amoxicillin may be advantageous. The combination of these two antibiotics with conventional periodontal therapy24,25 provides better disease control and better clinical improvement in attachment levels in difficult-to-manage periodontitis cases than similar periodontal therapy without antibiotics. Similar effects were seen for a variety of antibiotic types. However, a lack of sufficient sample sizes among studies makes it difficult to offer specific recommendations about which antibiotics were most effective.26

BOX 40-1 Systemic Tetracycline in Treatment of Aggressive Periodontitis

Systemic tetracycline (250 mg of tetracycline hydrochloride 4 times daily for at least 1 week) should be given in conjunction with local mechanical therapy. If surgery is indicated, systemic tetracycline should be prescribed and the patient instructed to begin taking the antibiotic approximately 1 hour before surgery. Doxycycline, 100 mg/day, may be used instead of tetracycline. Chlorhexidine rinses should be prescribed and continued for several weeks to enhance plaque control and facilitate healing.

The criteria for selection of antibiotics are not clear. Good clinical and microbiologic responses have been reported with several individual antibiotics and antibiotic combinations (Table 40-1). The optimal antibiotic or combination for any particular infection probably depends on the case. Choices must be made based on patient-related and disease-related factors.

TABLE 40-1 Antibiotic Therapy for Aggressive Periodontitis

| Associated Microflora | Antibiotic of Choice |

|---|---|

| Gram-positive organisms | Amoxicillin–clavulanate potassium (Augmentin)12,72 |

| Gram-negative organisms | Clindamycin22,23,68,72 |

| Nonoral gram-negative, facultative rods | Ciprofloxacin41 |

| Pseudomonads, staphylococci | |

| Black-pigmented bacteria and spirochetes | Metronidazole22,65 |

| Prevotella intermedia, Porphyromonas gingivalis | Tetracycline55 |

| Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans | Metronidazole-amoxicillin22,65 Metronidazole-ciprofloxacin Tetracycline53 |

| P. gingivalis | Azithromycin54 |

Microbial Testing

Some investigators and clinicians advocate microbial testing to identify the specific periodontal pathogens responsible for disease and to select an appropriate antibiotic based on sensitivity and resistance. There may be specific cases in which bacterial identification and antibiotic-sensitivity testing is invaluable. For example, in localized aggressive periodontitis cases, tetracycline-resistant Actinobacillus species have been suspected. If antibiotic susceptibility tests determine that tetracycline-resistant species exist in the lesion, the clinician may be advised to consider another antibiotic or an antibiotic combination, such as amoxicillin and metronidazole.18,55,66

In practice, antibiotics are often used empirically without microbial testing. One study evaluated and compared the results of microbial testing offered by two independent laboratories.46,63 Two microbiologic cultures, sampled simultaneously from the same sites in 20 patients, were submitted separately to each of the two laboratories for bacterial identification and antibiotic-sensitivity testing. The reported presence of bacterial species varied from one laboratory to another, as did their antimicrobial recommendations. Interestingly, the combination of amoxicillin and metronidazole yielded the highest level of agreement (80%). This is likely attributed to the effectiveness of this combination, as well as a clinical predisposition to favor a known regimen. These findings suggest that the usefulness of microbial testing may be limited and led the authors to conclude that the empiric use of antibiotics, such as a combination of amoxicillin and metronidazole, may be more clinically sound and cost-effective than bacterial identification and antibiotic-sensitivity testing.46,63

Nonetheless, the use of microbial testing should be considered whenever a case of aggressive periodontitis is not responding or if the destruction continues despite good therapeutic efforts.

Local Delivery

The use of local delivery to administer antibiotics offers a novel approach to the management of periodontal “localized” infections. The primary advantage of local therapy is that smaller total dosages of topical agents can be delivered inside the pocket, avoiding the side effects of systemic antibacterial agents while increasing the exposure of the target microorganisms to higher concentrations, and therefore more therapeutic levels, of the medication. Local delivery agents have been formulated in many different forms, including solutions, gels, fibers, and chips19,20,31 (see Chapter 47).

Full-Mouth Disinfection

Another approach to antimicrobial therapy in the control of infection associated with periodontitis is the concept of full-mouth disinfection. The concept, described by Quirynen et al,56 consists of full-mouth debridement (removal of all plaque and calculus) completed in 2 appointments within a 24-hour period. In addition to scaling and root planing, the tongue is brushed with a chlorhexidine gel (1%) for 1 minute, the mouth is rinsed with a chlorhexidine solution (0.2%) for 2 minutes, and periodontal pockets are irrigated with a chlorhexidine solution (1%).

In a clinical and microbiologic study, 10 patients with advanced chronic periodontitis were randomly assigned to test or control groups. Test patients were treated as just described while control patients received scaling and root planing by quadrant at 2-week intervals along with oral hygiene instructions. At 1 and 2 months after treatment, the test group showed significantly higher reduction in probing pocket depth, especially for pockets that were initially deep (7 to 8 mm). Patients in the test group also had significantly lower pathogenic microorganisms after treatment compared with controls. Several follow-up studies by the same center demonstrated similar results for up to 6 months after therapy.6,7,67 In another study, the same group included a test group who did not use chlorhexidine as part of the one-stage full-mouth disinfection.57 Interestingly, the results of both test groups (with and without chlorhexidine) were similar and were significantly better than for controls. The authors concluded that the beneficial effects of one-stage full-mouth disinfection probably result from the full-mouth debridement within 24 hours rather than the adjunctive chlorhexidine treatment.

A few reports have included patients with aggressive (early-onset) periodontitis in their evaluation of the one-stage full-mouth disinfection protocol.13,50,58 As with the advanced chronic periodontitis group, De Soete et al13 found a significant reduction in probing pocket depth and gain in clinical attachment in patients with aggressive periodontitis up to 8 months after treatment compared with controls (scaling and root planing by quadrant at 2-week intervals). They also found significant reductions in periodontal pathogens up to 8 months after therapy. Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythia were reduced to levels below detection.

Host Modulation

A novel approach in the treatment of aggressive periodontitis and difficult-to-control forms of periodontal disease is the administration of agents that modulate the host response. Several agents have been used or evaluated to modify the host response to disease (see Chapter 48).

The use of sub-antimicrobial dose doxycycline (SDD) may help to prevent the destruction of the periodontal attachment by controlling the activation of matrix metalloproteinases, primarily collagenase and gelatinase, from both infiltrating cells and resident cells of the periodontium, primarily the neutrophils.65 SDD as an adjunct to repeated mechanical debridement resulted in clinical improvement in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis.35 More than 50% of the patients in this study were smokers. Other agents, such as flurbiprofen, indomethacin, and naproxen, may reduce inflammatory mediator production.29 Further research needs to be done to substantiate the effects of these agents.

Treatment Planning and Restorative Considerations

Successful management of patients with aggressive periodontitis must include tooth replacement as part of the treatment plan. In some advanced cases of aggressive periodontitis, the overall treatment success for the patient may be enhanced if severely compromised teeth are extracted. The outcome of treatment for these teeth is limited, and more importantly, the retention of severely diseased teeth over time may result in additional bone loss and teeth that are further compromised. The risk of further bone loss is even a greater concern now with the current success and predictability of dental implants and the desire to preserve bone for implant placement. Any additional alveolar bone loss in an area that has already undergone severe bone loss may further compromise residual anatomy and impair the opportunity for tooth replacement with a dental implant. This is especially true for certain areas with poor bone quality or limited bone volume, such as the posterior maxilla. Fortunately, healing of extraction sites is typically uneventful in patients with aggressive periodontitis, and bone augmentation of defect sites is predictable.

In the patient with aggressive periodontitis, the approach to restorative treatment should be made based on a single premise: extract severely compromised teeth early and plan treatment to accommodate future tooth loss. The teeth with the best prognosis should be identified and considered when planning the restorative treatment. The lower cuspids and first premolars are generally more resistant to loss, probably because of the favorable anatomy (single roots, no furcations) and easier access for patient oral hygiene. As a rule, an extensive fixed prosthesis should be avoided, and removable partial dentures should be planned in such a way as to allow for the addition of teeth.

When hopeless teeth are extracted, they need to be replaced. The desire to replace missing teeth in a permanent manner without preparation of adjacent teeth for a fixed partial denture motivated clinicians to attempt transplantation of teeth from one site to another. Transplantation of developing third molars to the sockets of hopeless first molars has been attempted with limited success.9,37,44 Clearly, the success and predictability of dental implants have obviated the need for attempting to transplant teeth to edentulous sites.

Use of Dental Implants

Initially, the use of dental implants was suggested and implemented with much caution in patients with aggressive periodontitis because of an unfounded fear of bone and implant loss. However, evidence to the contrary appears to support the use of dental implants in patients treated for aggressive periodontal disease.42,49,51,74 A recent systematic review of implant outcomes in patients treated for aggressive periodontitis suggests a good short-term survival of implants placed in well maintained aggressive periodontitis patients.2 In a 10-year follow-up study, Mengel et al47 reported successful implant rehabilitation of partially edentulous patients treated for generalized aggressive periodontitis. However, they reported significantly greater bone and attachment loss around implants in the treated generalized aggressive periodontitis patients as compared to the control group of periodontally healthy patients. Thus it is possible to consider the use of dental implants in the overall treatment plan for patients with aggressive periodontitis.

There is scant evidence to support the use of bone augmentation procedures in preparation for or in combination with implant placement in patients treated for aggressive periodontitis. One case report with short-term follow-up suggests it is successful.28 A prospective study of ten patients treated for generalized aggressive periodontitis undergoing guided bone regeneration followed by implant placement found that the implant survival rate was 100% after 3 years.48 However, a slightly greater attachment (0.65 mm) and bone (1.78 mm) loss was observed in the aggressive periodontitis group as compared to 10 periodontally healthy controls who received implants without bone augmentation.

Clinical Consideration

It is important to recognize that special consideration must be given to the risk of occlusal overload of implants placed in a periodontally compromised dentition. This is especially true when only one or a few implants are used to replace a limited number of teeth with an implant-supported fixed crown or bridge in a patient with a majority of the remaining dentition being mobile. The immobility of implants in a dentition that does not have a stable vertical occlusal stop may lead to implant overloaded.

Periodontal Maintenance

When patients with aggressive periodontitis are transferred to maintenance care, their periodontal condition must be stable (i.e., no clinical signs of disease and no periodontal pathogens). Each maintenance visit should consist of a medical history review, an inquiry about any recent periodontal problems, assessment risk of factors, a comprehensive periodontal and oral examination, thorough root debridement, and prophylaxis, followed by a review of oral hygiene instructions. If oral hygiene is not good, patients may benefit most from a review of oral hygiene instructions and visualization of plaque in their own mouth before debridement and prophylaxis.

Frequent maintenance visits appear to be one of the most important factors in the control of disease and the success of treatment in patients with aggressive periodontitis.39,68 In a study of 25 individuals with aggressive (early-onset) periodontitis followed with maintenance every 3 to 6 months for 5 years, it was concluded that patients with aggressive periodontitis could be effectively maintained with clinical and microbiologic improvements after active periodontal therapy.30 The presence of high bacterial counts (particularly P. gingivalis and Treponema denticola), number of acute episodes, number of teeth lost, smoking, and stress appear to be significant factors in the small percentage of sites that showed progressive bone loss. In a 5-year follow-up study of 13 patients with aggressive periodontitis, comprehensive mechanical, surgical, and antimicrobial therapy with supportive periodontal maintenance every 3 to 4 months, periodontal disease progression was arrested in 95% of the initially affected lesions. Only 2% to 5% experienced discrete episodes of loss of periodontal support.10

A supportive periodontal maintenance program aimed at early detection and treatment of sites that begin to lose attachment should be established. The duration between these recall visits is usually short during the first period after the patient’s completion of therapy, generally no longer than 3-month intervals. Acute episodes of gingival inflammation can be detected and managed earlier when the patient is on a frequent monitoring cycle. Monitoring as frequently as every 3 to 4 weeks may be necessary when the disease is thought to be active. If signs of disease activity and progression persist despite therapeutic efforts, frequent visits and good patient compliance, microbial testing may be indicated. The rate of disease progression may be faster in younger individuals, and therefore the clinician should monitor such patients more frequently. Over time the recall maintenance interval can be adjusted (more or less often) to suit the patient’s level of oral hygiene and control of disease, as determined by each examination.

Close collaboration between members of the treatment team, including the periodontist, general dentist, dental hygienist, and patient’s physician, is required for continuity of care and for patient motivation and encouragement. It is important to monitor and observe the patient’s overall physical status as well, because weight loss, depression, and malaise have been reported in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis. Finally, there is a constant need to reinforce patient education about disease etiology and preventive practices (i.e., oral hygiene and control of risk factors).

Periodontitis Refractory to Treatment

Although refractory periodontitis is not currently considered a separate disease entity (see Chapter 4), patients who fail to respond to conventional therapy are considered to have periodontitis that is “refractory” to treatment. It is possible to characterize any form of periodontal disease (e.g., chronic periodontitis, aggressive periodontitis) as refractory to treatment.

These cases are difficult to manage because the etiology behind their lack of response to therapy is unknown. Initially, because contributing factors may have been overlooked, it is important to evaluate the adequacy of treatment attempts thoroughly and to consider other possible etiologies before concluding that a case truly is refractory. A patient with periodontitis that is refractory to treatment often does not have any distinguishing clinical characteristics on initial examination compared with cases of periodontitis that respond normally. Therefore the initial treatment would follow conventional therapeutic modalities for periodontitis. After treatment, if the patient has not responded as expected, the clinician should rule out the following conditions:

A case may be considered refractory to treatment only when loss of periodontal attachment and bone continues after well-executed treatment in a patient with good oral hygiene and no other infections or etiologic factors.

Clinicians are in a quandary when presented with a patient who is not responding to periodontal therapy. Therapeutic means must be broad in scope and thorough to ensure that all aspects of the host response are addressed. At a minimum, a frequent and intensive recall maintenance and home care program is necessary. Mechanical debridement with scaling and root planing can reduce total supragingival and subgingival bacterial masses, but major periodontal pathogens may persist. Surgical treatment may aid in providing access for debridement and in elimination of bacterial pathogens.62 In addition, the morphology of the gingival tissues should be modified to facilitate daily plaque removal by the patient.

Systemic antibiotic therapy is administered to reinforce mechanical periodontal treatment and support the host defense system in overcoming the infection by killing subgingival pathogens that remain after conventional mechanical periodontal therapy. Many antibiotics have been used according to the target microflora with various degrees of success23 (see Table 40-1). For patients with refractory disease who fail to respond to initial antibiotic therapy, subsequent treatment should include microbial testing with bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility.

Antibiotic resistance is a potential problem. Patients with periodontitis that is refractory to treatment often present with a history of previous tetracycline therapy, and thus they may have a microflora that is resistant to this drug.32,43,70,71 Tetracycline-resistant bacteria have been isolated from patients with periodontitis refractory to treatment.53 However, some patients with refractory disease may still benefit from the use of tetracycline or one of its derivatives.

Cases of periodontitis (refractory) in which the associated microflora consists primarily of gram-positive microorganisms have been successfully treated with amoxicillin–clavulanate potassium. Many efforts have been made to establish the most appropriate regimen of antibiotic therapy for these patients. Similar antimicrobial regimens, consisting of 250 mg of amoxicillin and 125 mg of clavulanate potassium, have been administered 3 times daily for 14 days, with scaling and root planing, and produced a reduction in attachment loss for at least 12 months. A regimen of 1 capsule containing the same amount of drug every 6 hours for 2 weeks, with intrasulcular full-mouth lavage using a 10% povidone-iodine solution and chlorhexidine oral rinses twice daily, resulted in a reduction in attachment loss that persisted at approximately 34 months.12 A regimen of 500 mg of metronidazole 3 times daily for 7 days was shown to be effective in treating periodontitis (refractory) in patients who were culture positive for T. forsythia in the absence of A. actinomycetemcomitans.73

Clindamycin is a potent antibiotic that penetrates well into gingival fluid, although it is not usually effective against A. actinomycetemcomitans and Eikenella corrodens.70 However, clindamycin has been effective in controlling the extent and rate of disease progression in refractory cases in patients who have a microflora susceptible to this antibiotic.23,41,69 A regimen of clindamycin hydrochloride, 150 mg, 4 times daily for 7 days, combined with scaling and root planing produced a decrease in the incidence of disease activity from an annual rate of 8% to an annual rate of 0.5% of sites per patient.22 Clindamycin should be prescribed with caution because of the potential for pseudomembranous colitis from superinfections with Clostridium difficile. Patients should be warned and advised to discontinue the antibiotic if symptoms of diarrhea develop.

Azithromycin may be effective in periodontitis that is refractory to treatment, especially in patients infected with P. gingivalis.54

Combinations of antibiotic therapy may offer greater promise as adjunctive treatment for the management of refractory periodontitis.3,12,18,43 The rationale is based on the diversity of putative pathogens21,66 and no single antibiotic being bactericidal for all known pathogens. Combination antibiotic therapy may help broaden the antimicrobial range of the therapeutic regimen beyond that attained by any single antibiotic. Other advantages include lowering the dose of individual antibiotics by exploiting possible synergy between two drugs against targeted organisms. In addition, combination therapy may prevent or forestall the emergence of bacterial resistance. Many combinations of antibiotics have demonstrated significant improvement in the clinical aspects of the disease.43 Examples of combinations include amoxicillin-clavulanate18 or metronidazole-amoxicillin for the treatment of A. actinomycetemcomitans–associated periodontitis; metronidazole-doxycycline for the prevention of recurrent periodontitis; metronidazole-ciprofloxacin59 for the treatment of recurrent cases containing a microflora associated with enteric rods and pseudomonads; and amoxicillin-doxycycline43 in the treatment of periodontitis associated with A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis.

Some cases of periodontitis that are refractory to treatment may not respond to a given antibiotic regimen. When this occurs, the clinician should consider a different antimicrobial therapy based on microbial susceptibility analysis. At this point in the therapy, strong consideration should be given to consulting with the patient’s physician for an evaluation of a possible host immune system deficiency or a metabolic problem such as diabetes.

Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis

Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP) is a rare disease, especially in developed countries. Often, NUP is diagnosed in individuals with a compromised host immune response (see Chapter 17). The incidence of NUP in specific populations, such as patients who are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or who have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), has been reported as 0% to 6%. Most patients diagnosed with NUP apparently have diseases or conditions that impair their host immune response. These patients often have an underlying predisposing systemic factor that renders them susceptible to necrotizing ulcerative periodontal disease. For this reason, patients presenting with NUP should be treated in consultation with their physician.

A comprehensive medical evaluation and diagnosis of any condition that may be contributing to an altered host immune response should be completed. It is also important to rule out any hematologic disease (e.g., leukemia) before initiating treatment of a case that has a similar presentation to NUP (see Chapter 27 and Figure 27-17 Figure 27-19 ).

Treatment can be initiated only after a thorough medical history and examination to identify the existence of any systemic diseases, such as leukemia or other hematologic disorders, that might contribute to the oral presentation. Treatment for NUP includes local debridement of lesions with scaling and root planing, lavage, and instructions for good oral hygiene. It may be necessary to use local anesthesia during the debridement because lesions are frequently painful. The use of ultrasonic instrumentation with profuse irrigation may enhance debridement and flushing of the deep lesions. Achieving good oral hygiene may be challenging as well until the lesions and associated pain resolve.

Antimicrobial adjuncts, such as chlorhexidine, added to the oral hygiene regimen may be effective in contributing to the daily reduction of bacterial loads. Patients frequently complain of pain. The use of locally applied topical antimicrobials and systemic antibiotics, as well as systemic analgesics, should be used as indicated by signs and symptoms.

Patients with NUP often harbor bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other nonoral microorganisms, complicating the selection of antimicrobial therapy. Superinfection or overgrowth of fungi and viruses may be propagated by antibiotic therapy. Antifungal and/or antiviral agents can be considered prophylactically against these infections or after they are diagnosed. Because oral hygiene for these patients is complicated by the painful lesions, alternative methods should be encouraged. In such patients, irrigation with diluted cleansing and antibacterial agents can be of some benefit.

Ultimately, the successful treatment of NUP may depend on the resolution or treatment of the systemic condition (e.g., immune compromise) that predisposed the individual to the disease. Evaluation and treatment of patients with known systemic conditions, such as HIV infection, should be coordinated with the patient’s physician.

Conclusion

Aggressive and atypical forms of periodontitis are a challenge for the clinician because they are infrequently encountered and because the predictability of treatment success varies from one patient to another. Clearly, the host immune response plays a significant role in these patients. As a result, these unusual disease entities often do not respond well to conventional therapy. Therapeutic measures must be broad in scope and thorough to ensure that all aspects of the host response are addressed. At a minimum, a frequent professional recall maintenance and personal daily oral hygiene program is necessary. The best treatment for these patients appears to be a combination of conventional treatment with antimicrobial therapy (systemic and/or local delivery) and close follow-up care.

Many questions remain regarding the selection of antibiotic type, dosage, duration, and route of administration. Antibiotic regimens have been successful in selected cases; common practice continues to be somewhat empiric. Bacterial identification may be of value for patients with disease that continues to progress despite diligent efforts by the practitioner and patient. The information can be used to determine antibiotic susceptibility of suspected pathogens. Adjunctive host modulation, although only an emerging area of interest, may prove to be promising in the treatment of patients with aggressive periodontitis, as well as periodontitis that is refractory to treatment.

1 Parameter on aggressive periodontitis. American Academy of Periodontology. J Periodontol. 2000;71:867-869.

2 Al-Zahrani MS. Implant therapy in aggressive periodontitis patients: a systematic review and clinical implications. Quintessence Int. 2008;39:211-215.

3 Atiken S, Birek P, Kulkarni GV, et al. Serial doxycycline and metronidazole in prevention of recurrent periodontitis in high-risk patients. J Periodontal. 63, 1993.

4 Baer PN, Socransky SS. Periodontosis: case report with long-term follow-up. Periodontal Case Rep. 1979;1:1-6.

5 Barnett ML, Baker RL. The formation and healing of osseous lesions in a patient with localized juvenile periodontitis, case report. J Periodontol. 1983;54:148-150.

6 Bollen CM, Mongardini C, Papaioannou W, et al. The effect of a one-stage full-mouth disinfection on different intra-oral niches. Clinical and microbiological observations. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:56-66.

7 Bollen CM, Vandekerckhove BN, Papaioannou W, et al. Full- versus partial-mouth disinfection in the treatment of periodontal infections. A pilot study: long-term microbiological observations. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:960-970.

8 Bonta H, Llambes F, Moretti AJ, et al. The use of enamel matrix protein in the treatment of localized aggressive periodontitis: a case report. Quintessence Int. 2003;34:247-252.

9 Borring-Moller G, Frandsen A. Autologous tooth transplantation to replace molars lost in patients with juvenile periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1978;5:152-158.

10 Buchmann R, Nunn ME, Van Dyke TE, Lange DE. Aggressive periodontitis: 5-year follow-up of treatment. J Periodontol. 2002;73:675-683.

11 Carranza FAJr. Saglie R, Newman MG, Valentin PL: Scanning and transmission electron microscopic study of tissue-invading microorganisms in localized juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1983;54:598-617.

12 Collins JG, Offenbacher S, Arnold RR. Effects of a combination therapy to eliminate Porphyromonas gingivalis in refractory periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1993;64:998-1007.

13 de Soete M, Mongardini C. Peuwels M, et al: One-stage full-mouth disinfection: long-term microbiological results analyzed by checkerboard DNA-DNA hybridization. J Periodontal. 72, 1983.

14 Deas DE, Mackey SA, McDonnell HT. Systemic disease and periodontitis: manifestations of neutrophil dysfunction. Periodontal 2000. 32, 2003.

15 Delcourt-Debruyne EM, Boutigny HR, Hildebrand HF. Features of severe periodontal disease in a teenager with Chediak-Higashi syndrome. J Periodontol. 2000;71:816-824.

16 Dodson SA, Takei HH, Carranza FAJr. Clinical success in regeneration: report of a case. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1996;16:455-461.

17 Esposito M, Coulthard P, Worthington HV: Enamel matrix derivative (Emdogain) for periodontal tissue regeneration in intrabony defects, Cochrane Database Syst Rev:CD003875, 2003.

18 Flemmig TF, Milian E, Karch H, Klaiber B. Differential clinical treatment outcome after systemic metronidazole and amoxicillin in patients harboring Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and/or Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:380-387.

19 Fourmousis I, Tonetti MS, Mombelli A, et al. Evaluation of tetracycline fiber therapy with digital image analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:737-745.

20 Garrett S, Johnson L, Drisko CH, et al. Two multi-center studies evaluating locally delivered doxycycline hyclate, placebo control, oral hygiene, and scaling and root planing in the treatment of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1999;70:490-503.

21 Genco RJ, Ciancio SG, Rosling B. Treatment of localized juvenille periodontitis. J Dent Res. 1981;60:(abstract).

22 Gordon J, Walker C, Hovliaras C, Socransky S. Efficacy of clindamycin hydrochloride in refractory periodontitis: 24-month results. J Periodontol. 1990;61:686-691.

23 Gordon JM, Walker CB. Current status of systemic antibiotic usage in destructive periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1993;64:760-771.

24 Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Gunsolley JC. Systemic anti-infective periodontal therapy. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8:115-181.

25 Haffajee AD, Uzel NG, Arguello EI, et al. Clinical and microbiological changes associated with the use of combined antimicrobial therapies to treat “refractory” periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:869-877.

26 Herrera D, Sanz M, Jepsen S, et al. A systematic review on the effect of systemic antimicrobials as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(Suppl 3):136-159. discussion 160-2

27 Hirschfeld L, Wasserman B. A long-term survey of tooth loss in 600 treated periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 1978;49:225-237.

28 Hoffmann O, Beaumont C, Zafiropoulos GG. Combined periodontal and implant treatment of a case of aggressive periodontitis. J Oral Implantol. 2007;33:288-292.

29 Howell T, Williams R, Periodontology AAo. Pharmacologic blocking of host response as an adjunct in the management of periodontal disease: a research update. Chicago. 1992.

30 Kamma JJ, Baehni PC. Five-year maintenance follow-up of early-onset periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:562-572.

31 Killoy WJ. The use of locally delivered chlorhexidine in the treatment of periodontitis. Clinical results. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:953-958. discussion 978-9

32 Kornman KS, Karl EH. The effect of long-term low-dose tetracycline therapy on the subgingival microflora in refractory adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1982;53:604-610.

33 Lang N, Bartold PM, Cullinan M, et al. Consensus Report: aggressive periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999.

34 Lavine WS, Maderazo EG, Stolman J, et al. Impaired neutrophil chemotaxis in patients with juvenile and rapidly progressing periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 1979;14:10-19.

35 Lee HM, Ciancio SG, Tuter G, et al. Subantimicrobial dose doxycycline efficacy as a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor in chronic periodontitis patients is enhanced when combined with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. J Periodontol. 2004;75:453-463.

36 Leino L, Hurttia H. A potential role of an intracellular signaling defect in neutrophil functional abnormalities and promotion of tissue damage in patients with localized juvenile periodontitis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:215-222.

37 Levine RA. Twenty-five month follow-up of an autogenous third molar transplantation in a localized juvenile periodontitis patient: a case report. Compendium. 1987;8:560. 563, 566 passim

38 Liljenberg B, Lindhe J. Juvenile periodontitis. Some microbiological, histopathological and clinical characteristics. J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:48-61.

39 Lindhe J, Liljenberg B. Treatment of localized juvenile periodontitis. Results after 5 years. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:399-410.

40 Mabry TW, Yukna RA, Sepe WW. Freeze-dried bone allografts combined with tetracycline in the treatment of juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1985;56:74-81.

41 Magnusson I, Low SB, McArthur WP, et al. Treatment of subjects with refractory periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:628-637.

42 Malmstrom HS, Fritz ME, Timmis DP, Van Dyke TE. Osseo-integrated implant treatment of a patient with rapidly progressive periodontitis. A case report. J Periodontol. 1990;61:300-304.

43 Matisko MW, Bissada NF. Short-term sequential administration of amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium and doxycycline in the treatment of recurrent/progressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1993;64:553-558.

44 Mattout P, Moskow BS, Fourel J. Repair potential in localized juvenile periodontitis. A case in point. J Periodontol. 1990;61:653-660.

45 McFall WTJr. Tooth loss in 100 treated patients with periodontal disease. A long-term study. J Periodontol. 1982;53:539-549.

46 Mellado JR, Freedman AL, Salkin LM, et al. The clinical relevance of microbiologic testing: a comparative analysis of microbiologic samples secured from the same sites and cultured in two independent laboratories. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2001;21:232-239.

47 Mengel R, Behle M, Flores-de-Jacoby L. Osseointegrated implants in subjects treated for generalized aggressive periodontitis: 10-year results of a prospective, long-term cohort study. J Periodontol. 2007;78:2229-2237.

48 Mengel R, Flores-de-Jacoby L. Implants in regenerated bone in patients treated for generalized aggressive periodontitis: a prospective longitudinal study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2005;25:331-341.

49 Mengel R, Schroder T, Flores-de-Jacoby L. Osseointegrated implants in patients treated for generalized chronic periodontitis and generalized aggressive periodontitis: 3- and 5-year results of a prospective long-term study. J Periodontol. 2001;72:977-989.

50 Mongardini C, van Steenberghe D, Dekeyser C, Quirynen M. One stage full- versus partial-mouth disinfection in the treatment of chronic adult or generalized early-onset periodontitis. I. Long-term clinical observations. J Periodontol. 1999;70:632-645.

51 Nevins M, Langer B. The successful use of osseointegrated implants for the treatment of the recalcitrant periodontal patient. J Periodontol. 1995;66:150-157.

52 Nyman S, Lindhe J, Rosling B. Periodontal surgery in plaque-infected dentitions. J Clin Periodontol. 1977;4:240-249.

53 Olsvik B, Tenover FC. Tetracycline resistance in periodontal pathogens. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16(Suppl 4):S310-S313.

54 Pajukanta R. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of Porphyromonas gingivalis to azithromycin, a novel macrolide. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1993;8:325-326.

55 Pavicic MJ, van Winkelhoff AJ, Pavivic-Temming YA, et al. Metronidazole susceptibility factors in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 35, 1995.

56 Quirynen M, Bollen CM, Vandekerckhove BN, et al. Full- vs. partial-mouth disinfection in the treatment of periodontal infections: short-term clinical and microbiological observations. J Dent Res. 1995;74:1459-1467.

57 Quirynen M, Mongardini C, de Soete M, et al. The role of chlorhexidine in the one-stage full-mouth disinfection treatment of patients with advanced adult periodontitis. Long-term clinical and microbiological observations. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:578-589.

58 Quirynen M, Mongardini C, Pauwels M, et al. One stage full- versus partial-mouth disinfection in the treatment of chronic adult or generalized early-onset periodontitis. II. Long-term impact on microbial load. J Periodontol. 1999;70:646-656.

59 Rams TE, Feik D, Slots J. Ciprofloxacin/metronidazole treatment of recurrent adult periodontitis. J Dent Res. 70, 1992.

60 Rosling B, Nyman S, Lindhe J. The effect of systematic plaque control on bone regeneration in infrabony pockets. J Clin Periodontol. 1976;3:38-53.

61 Rosling B, Nyman S, Lindhe J, Jern B. The healing potential of the periodontal tissues following different techniques of periodontal surgery in plaque-free dentitions. A 2-year clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 1976;3:233-250.

62 Saglie FR, Carranza FAJr, Newman MG, et al. Identification of tissue-invading bacteria in human periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1982;17:452-455.

63 Salkin LM, Freedman AL, Mellado JR, et al. The clinical relevance of microbiologic testing. Part 2: a comparative analysis of microbiologic samples secured simultaneously from the same sites and cultured in the same laboratory. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2003;23:121-127.

64 Tanner AC, Socransky SS, Goodson JM. Microbiota of periodontal pockets losing crestal alveolar bone. J Periodontal Res. 1984;19:279-291.

65 Thomas JG, Metheny RJ, Karakiozis JM, et al. Long-term sub-antimicrobial doxycycline (Periostat) as adjunctive management in adult periodontitis: effects on subgingival bacterial population dynamics. Adv Dent Res. 1998;12:32-39.

66 van Winkelhoff AJ, Tijhof CJ, de Graaff J. Microbial and clinical results of metronidazole amoxicillin therapy in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans-associated periodontitis. J Periodontal. 63, 1992.

67 Vandekerckhove BN, Bollen CM, Dekeyser C, et al. Full- versus partial-mouth disinfection in the treatment of periodontal infections. Long-term clinical observations of a pilot study. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1251-1259.

68 Waerhaug J. Subgingival plaque and loss of attachment in periodontosis as evaluated on extracted teeth. J Periodontol. 1977;48:125-130.

69 Walker C, Gordon J. The effect of clindamycin on the microbiota associated with refractory periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1990;61:692-698.

70 Walker C, Karpinia K. Rationale for use of antibiotics in periodontics. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1188-1196.

71 Walker CB, Gordon JM, Magnusson I, Clark WB. A role for antibiotics in the treatment of refractory periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1993;64:772-781.

72 Walker CB, Pappas JD, Tyler KZ, et al. Antibiotic susceptibilities of periodontal bacteria. In vitro susceptibilities to eight antimicrobial agents. J Periodontol. 1985;56:67-74.

73 Winkel EG, Van Winkelhoff AJ, Timmerman MF, et al. Effects of metronidazole in patients with “refractory” periodontitis associated with Bacteroides forsythus. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:573-579.

74 Yalcin S, Yalcin F, Gunay Y, Bellaz B, et al. Treatment of aggressive periodontitis by osseointegrated dental implants. A case report. J Periodontol. 2001;72:411-416.

75 Yukna RA, Sepe WW. Clinical evaluation of localized periodontosis defects treated with freeze-dried bone allografts combined with local and systemic tetracyclines. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1982;2:8-21.