Evidence-Based Practice

• Discuss the benefits of evidence-based practice.

• Describe the five steps of evidence-based practice.

• Explain the levels of evidence available in the literature.

• Discuss ways to apply evidence in practice.

• Explain how nursing research improves nursing practice.

• Discuss the steps of the research process.

• Discuss priorities for nursing research.

• Explain the relationship between evidence-based practice and performance improvement.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Rick has been a registered nurse (RN) on a surgical unit for over 5 years. During that time standard nursing care for patients following abdominal surgery has included getting the patient out of bed, sitting in a chair, and walking within the first postoperative day. Patients are encouraged to walk farther and more frequently each day until they begin to pass gas or have a bowel movement. Rick has noticed lately that several of his patients who have had abdominal surgery have experienced a postoperative ileus. This happens when the patient’s gastrointestinal tract fails to begin moving after surgery (see Chapter 50). When patients have a postoperative ileus, they have increased pain and are in the hospital longer. Rick raises the question with the other RNs in the department, “What if we had our patients sit and rock in a rocking chair instead of sitting in a regular high-back chair after abdominal surgery? Is it possible that rocking after surgery will decrease the incidence of postoperative ileus?”

Most nurses like Rick practice nursing according to what they learn in nursing school, their experiences in practice, and the policies and procedures of their institution. Such an approach to practice does not guarantee that nursing practice is always based on up-to-date scientific information. Sometimes nursing practice is based on tradition and not on current evidence. If Rick went to the scientific literature for articles about how to prevent postoperative ileus, he would find some studies that indicate that simple changes in activity such as encouraging patients to rock in a rocking chair following surgery may help them recover more quickly. The evidence from research and the opinions of nursing experts provide a basis for Rick and his colleagues to make evidence-based changes to their care of patients following abdominal surgery. The use of evidence in practice enables clinicians like Rick to provide the highest quality of care to their patients and families.

A Case for Evidence

Nurses practice in an “age of accountability” in which quality and cost issues drive the direction of health care (Makadon et al., 2010; Moore et al., 2010). The general public is more informed about their own health and the incidence of medical errors within health care institutions across the country. Greater scrutiny is being given as to why certain health care approaches are used, which ones work, and which ones do not. As a result, evidence-based practice (EBP) is a guide to help nurses make effective, timely, and appropriate clinical decisions in response to the broad political, professional, and societal forces that nurses and other health professionals are confronted with daily (Scott and McSherry, 2009).

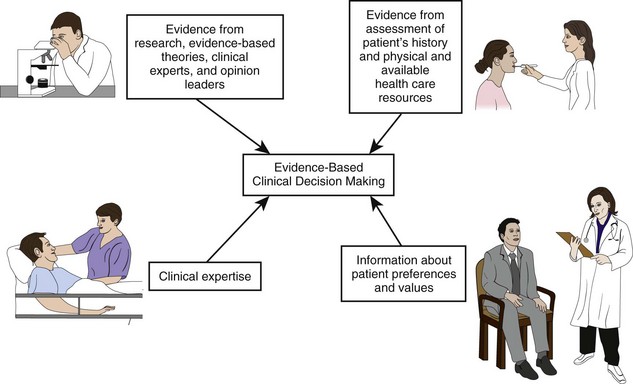

Nurses face important clinical decisions when caring for patients (e.g., what to assess in a patient and what interventions are best to use). It is important to translate best evidence into best practices at a patient’s bedside. For example, changing how patients are cared for after abdominal surgery is one way that Rick (see previous case study) can use evidence at the bedside. Evidence-based practice (EBP) is a problem-solving approach to clinical practice that integrates the conscientious use of best evidence in combination with a clinician’s expertise and patient preferences and values in making decisions about patient care (Fig. 5-1) (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011; Sackett et al., 2000). Today EBP is becoming a goal of all health care institutions and an expectation of professional nurses who are expected to use current evidence when caring for patients (Ingersoll et al., 2010).

Nurses find evidence in different places. A good textbook incorporates evidence into the practice guidelines and procedures it describes. However, a textbook relies on scientific literature, which is sometimes outdated by the time the book is published. Articles from nursing and the health care literature are available on almost any topic involving nursing practice in either journals or on the Internet. Although the scientific basis of nursing practice has grown, some practices are not yet “research based” (Titler et al., 2001). The challenge is to obtain the very best, most current accurate information at the right time, when you need it for patient care.

The best information is the evidence that comes from well-designed, systematically conducted research studies, mostly found in scientific journals. Unfortunately much of that evidence never reaches the bedside. Nurses in practice settings, unlike in educational settings, do not always have easy access to databases for scientific literature. Instead, they often care for patients on the basis of tradition or convenience. Another source of information comes from nonresearch evidence, including quality improvement and risk management data; international, national, and local standards; infection control data; benchmarking, retrospective, or concurrent chart reviews; and clinicians’ expertise. It is important to rely more on research evidence rather than solely on nonresearch evidence. When you face a clinical problem, always ask yourself where you can find the best evidence to help you find the best solution in caring for patients.

Even when you use the best evidence available, application and outcomes will differ based on your patient’s values, preferences, concerns, and/or expectations (Oncology Nursing Society [ONS], n.d.). As a nurse, you develop critical thinking skills to determine whether evidence is relevant and appropriate to your patients and to a clinical situation. For example, a single research article suggests that the use of therapeutic touch is effective in reducing abdominal incision pain. However, if your patient’s cultural beliefs prevent the use of touch, you will likely need to search for a better evidence-based therapy that patients will accept. Using your clinical expertise and considering patient values and preferences ensures that you apply the evidence available in practice both safely and appropriately.

Steps of Evidence-Based Practice

EBP is a systematic approach to rational decision making that facilitates achievement of best practices. A step-by-step approach ensures that you obtain the strongest available evidence to apply in patient care (Oh et al., 2010). There are six steps of EBP (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011):

2. Collect the most relevant and best evidence.

3. Critically appraise the evidence you gather.

4. Integrate all evidence with one’s clinical expertise and patient preferences and values in making a practice decision or change.

Ask a Clinical Question

Always think about your practice when caring for patients. Question what does not make sense to you and what needs to be clarified. Think about a problem or area of interest that is time consuming, costly, or not logical (Stilwell et al., 2010). Use problem- and knowledge-focused triggers to think critically about clinical and operational nursing unit issues (Titler et al., 2001). A problem-focused trigger is one you face while caring for a patient or a trend you see on a nursing unit. For example, while Rick is caring for patients following abdominal surgery, he wonders, “If we changed our patients’ activity levels after surgery, would they experience fewer episodes of postoperative ileus?” Other examples of problem-focused trends include the increasing number of patient falls or incidence of urinary tract infections on a nursing unit. Such trends lead you to ask, “How can I reduce falls on my unit?” or “What is the best way to prevent urinary tract infections in postoperative patients?”

A knowledge-focused trigger is a question regarding new information available on a topic. For example, “What is the current evidence to improve pain management in patients with migraine headaches?” Important sources of this type of information are standards and practice guidelines available from national agencies such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the American Pain Society (APS), or the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN). Other sources of knowledge-focused triggers include recent research publications and nurse experts within an organization.

Sometimes you use data gathered from a health care setting to examine clinical trends to develop clinical questions. For example, most hospitals keep monthly records on key quality of care or performance indicators such as medication errors or infection rates. All magnet-designated hospitals maintain the National Database of Nursing Quality Improvement (NDNQI) (see Chapter 2). The database includes information on falls, pressure ulcer incidence, and nurse satisfaction. Typically quality and risk management data do not give you evidence in finding a solution to a problem, but the data inform you about the nature or severity of problems that then allow you to form practice questions.

The questions you ask eventually lead you to the evidence for an answer. When you ask a question and then go to the scientific literature, you do not want to read 100 articles to find the handful that are most helpful. You want to be able to read the best four-to-six articles that specifically address your practice question. Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt (2011) suggest using a PICOT format to state your question. The five elements of a PICOT question are summarized in Box 5-1. The more focused a question you ask, the easier it becomes to search for evidence in the scientific literature. For example, Rick develops the following PICOT question: Do patients who have had abdominal surgery (P) and who rock in a rocking chair (I) have a reduced incidence of postoperative ileus (O) during hospitalization (T) when compared with patients who receive standard nursing care following surgery (C)? Another example is: Is an adult patient’s (P) blood pressure more accurate (O) when measuring with the patient’s legs crossed (I) versus the patient’s feet flat on the floor (C)?

Proper question formatting allows you to identify key words to use when conducting your literature search. Note that a well-designed PICOT question does not have to follow the sequence of P, I, C, O, and T. In addition, intervention (I), comparison (C), and time (T) are not appropriate to be used in every question. The aim is to ask a question that contains as many of the PICOT elements as possible. For example, here is a meaningful question that contains only a P and O: How do patients with cystic fibrosis (P) rate their quality of life (O)?

Inappropriately formed questions (e.g., What is the best way to reduce wandering? What is the best way to improve family’s satisfaction with patient care?) are background questions that will likely lead to many irrelevant sources of information, making it difficult to find the best evidence. Sometimes a background question is needed to identify a more specific PICOT question. The PICOT format allows you to ask questions that are intervention focused. For questions that are not intervention focused, the meaning of the letter I can be an area of interest (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). For example, What is the difference in retention (O) of new nursing graduates (P) who have previous experience as nurse assistants (I) versus those who do not (C)?

The questions you ask using a PICOT format help to identify knowledge gaps within a clinical situation. When you raise well–

thought-out questions, you should understand the evidence that is missing to guide clinical practice. Remember: do not be satisfied with clinical routines. Always question and use critical thinking to consider better ways to provide patient care.

Collect the Best Evidence

Once you have a clear and concise PICOT question, you are ready to search for evidence. You can find the evidence you need in a variety of sources: agency policy and procedure manuals, quality improvement data, existing clinical practice guidelines, or computerized bibliographical databases. Do not hesitate to ask for help to find appropriate evidence. Your faculty is always a key resource. When you are assigned to a health care setting, use agency experts such as advanced practice nurses, staff educators, risk managers, and infection control nurses.

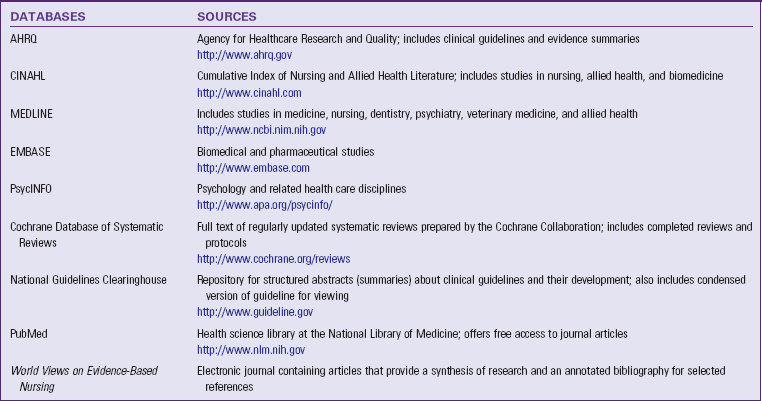

When using the scientific literature for evidence, seek the assistance of a medical librarian. He or she knows the various databases that are available to you (Table 5-1). The databases contain large collections of published scientific studies, including peer-reviewed research. A peer-reviewed article is one reviewed by a panel of experts familiar with the topic or subject matter of the article before it was published. The librarian is available to help translate your PICOT question into the language or key words that will yield the best evidence search. When conducting a search, it is necessary to enter and manipulate different key words until you get the combination that gives you the key articles that you want to read about your question. When you enter a word to search into a database, be prepared for some confusion with the evidence you obtain. The vocabulary within published articles is often vague. The word you select sometimes has one meaning to one author and a very different meaning to another.

When Rick searches for evidence to answer his PICOT question, he asks for help from a medical librarian. The medical librarian helps him learn how to choose alternative words or terms that identify his PICOT question. During their search Rick identifies three research articles published since 1990 that address the effects of rocking in a rocking chair on return of bowel function following abdominal surgery (Massey, 2010; Moore et al., 1995; Thomas et al., 1990).

MEDLINE and the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) are among the best-known comprehensive databases to search for scientific knowledge in health care (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). Among the many databases, some are available through vendors at a cost, some are free of charge, and some offer both options. As a student you have access to an institutional subscription through a vendor purchased by your school. One of the more common vendors is OVID, which offers several different databases. Databases are also available free on the Internet. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews is a valuable source of high-quality evidence. It includes the full text of regularly updated systematic reviews and protocols for reviews currently under way. Collaborative review groups prepare and maintain the reviews. The protocols provide the background, objectives, and methods for reviews in progress (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). The National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC) is a database supported by the AHRQ. It contains clinical guidelines, systematically developed statements about a plan of care for a specific set of clinical circumstances involving a specific patient population. Examples of clinical guidelines on NCG include care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes and practice guidelines for the treatment of adults with low back pain. The NGC is invaluable when developing a plan of care for a patient (see Chapter 18).

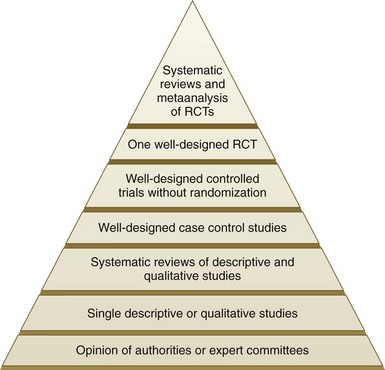

Fig. 5-2 represents the hierarchy of available evidence. The level of rigor or amount of confidence you can have in a study’s findings decreases as you move down the pyramid. At this point in your nursing career, you cannot be an expert on all aspects of the types of studies conducted. But you can learn enough about the types of studies to help you know which ones have the best scientific evidence. At the top of the pyramid are systematic reviews or meta-analyses, which are state-of-the-art summaries from an individual researcher or panel of experts. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews are the perfect answers to PICOT questions because they rigorously summarize current evidence.

FIG. 5-2 Hierarchy of evidence. RCTs, Randomized controlled trials. (Modified from Guyatt G, Rennie D: User’s guide to the medical literature, Chicago, 2002, American Medical Association; Harris RP et al: Current methods of the US Prevention Services Task Force: a review of the process, Am J Prev Med 20:21, 2001; Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E: Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: a guide to best practice, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2011, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.)

During either a meta-analysis or a systematic review, a researcher asks a PICOT question, reviews the highest level of evidence available (e.g., randomized controlled trials [RCTs]), summarizes what is currently known about the topic, and reports if current evidence supports a change in practice or if further study is needed. The main difference is that in a meta-analysis the researcher uses statistics to show the effect of an intervention on an outcome, whereas in a systematic review no statistics are used to draw conclusions about the evidence. In the Cochrane Library all entries include information on meta-analyses and systematic reviews. If you use MEDLINE or CINAHL, enter a textword such as “meta-analysis” or “systematic review” or the MeSH heading of evidence-based medicine to obtain scientific reviews on your PICOT question.

The RCT is the most precise form of experimental study and therefore is the gold standard for research. A single RCT is not as conclusive as a review of several RCTs on the same question. However, a single RCT that tests the intervention included in your question yields very useful evidence. If RCTs are not available, you can use results from other research studies such as descriptive or qualitative studies to help answer your PICOT question. The use of clinical experts may be at the bottom of the evidence pyramid, but do not consider clinical experts to be a poor source of evidence. Expert clinicians use evidence frequently as they build their own practice, and they are rich sources of information for clinical problems.

Critically Appraise the Evidence

Perhaps the most difficult step in the EBP process is critiquing or analyzing the available evidence. Critiquing evidence involves evaluating it, which includes determining the value, feasibility, and usefulness of evidence for making a practice change (ONS, n.d.). When critiquing evidence, first evaluate the scientific merit and clinical applicability of the findings of each study. Then with a group of studies and expert opinion determine what findings have a strong enough basis for use in practice. After critiquing the evidence you will be able to answer the following questions. Do the articles together offer evidence to explain or answer my PICOT question? Do the articles show support for the reliability and validity of the evidence? Can I use the evidence in practice?

As a student new to nursing, it takes time to acquire the skills to critique evidence like an expert. When you read an article, do not put it down and walk away because of the statistics and technical language. Know the elements of an article and use a careful approach when reviewing each one. Evidence-based articles include the following elements:

• Abstract. An abstract is a brief summary of the article that quickly tells you if it is research or clinically based. An abstract summarizes the purpose of the article. It also includes the major themes or findings and the implications for nursing practice.

• Introduction. The introduction contains more information about the purpose of the article. There is usually brief supporting evidence as to why the topic is important.

Together the abstract and introduction help you decide if you want to continue to read the entire article. You will know if the topic of the article is similar to your PICOT question or related closely enough to provide useful information. If you decide that this article may help answer your question, continue to read the next elements of the article.

• Literature review or background. A good author offers a detailed background of the level of science or clinical information that exists about the topic. The literature review offers an argument about what led the author to conduct a study or report on a clinical topic. This section of an article is very valuable. Even if the article itself does not address your PICOT question the way you desire, the literature review will possibly lead you to other more useful articles. After reading a literature review, you should have a good idea of how past research led to the researcher’s question. For example, a study designed to test an educational intervention for older adult family caregivers reviews literature that describes characteristics of caregivers, the type of factors influencing caregivers’ ability to cope with stressors of caregiving, and any previous educational interventions used with families.

• Manuscript narrative. The “middle section” or narrative of an article differs according to the type of evidence-based article it is (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). A clinical article describes a clinical topic, which often includes a description of a patient population, the nature of a certain disease or health alteration, how patients are affected, and the appropriate nursing therapies. An author sometimes writes a clinical article to explain how to use a therapy or new technology. A research article contains several subsections within the narrative, including the following:

• Purpose statement: Explains the focus or intent of a study. It includes research questions or hypotheses—predictions made about the relationship or difference between study variables (concepts, characteristics, or traits that vary within or among subjects). An example of a research question is: What environmental characteristics are common among young adults who experience frequent exacerbations of asthma?

• Methods or design: Explains how a research study was organized and conducted to answer the research question or test the hypothesis. This is when you learn the type of study that was conducted (e.g., RCT, case control study, or qualitative study). You also learn how many subjects or persons were in a study. In health care studies subjects may include patients, family members, or health care staff. The language in the methods section is sometimes confusing because it explains details about how the researcher designed the study to obtain the most accurate results possible. Use your faculty member as a resource to help interpret this section.

• Results or conclusions. Clinical and research articles have a summary section. In a clinical article the author explains the clinical implications for the topic presented. In a research article the author details the results of the study and explains whether a hypothesis is supported or how a research question is answered. This section includes a statistical analysis if it is a quantitative research study. A qualitative study summarizes the descriptive themes and ideas that arise from the researcher’s analysis of data. Do not let the statistical analysis in an article overwhelm you. Read carefully and ask these questions: Does the researcher describe the results? Were the results significant? A good author also discusses any limitations to a study in this section. The information on limitations is valuable in helping you decide if you want to use the evidence with your patients. Have a faculty member or an expert nurse help you interpret statistical results.

• Clinical implications. A research article includes a section that explains if the findings from the study have clinical implications. The researcher explains how to apply findings in a practice setting for the type of subjects studied.

After Rick critiques each article for his PICOT question, he combines the findings from the three articles he found about the use of rocking chairs to determine the state of the evidence. He uses critical thinking to consider the scientific rigor of the evidence and how well it answers his PICOT question. He also considers the evidence in light of his patients’ concerns and preferences. As a clinician Rick judges whether to use the evidence for the group of patients for whom he normally cares on the surgical unit. Patients frequently have complex medical histories and patterns of responses (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). Ethically it is important for Rick to consider evidence that will benefit patients and do no harm. He needs to decide if the evidence is relevant, is easily applicable in his setting of practice, and has the potential for improving patient outcomes.

Integrate the Evidence

Once you decide that the evidence is strong and applicable to your patients and clinical situation, incorporate it into practice. Your first step is simply to apply the research in your plan of care for a patient (see Chapter 18). Use the evidence you find as a rationale for an intervention you plan to try. For instance, you learned about an approach to bathe older adults who are confused and decide to use the technique during your next clinical assignment. You use the bathing technique with your own assigned patients, or you work with a group of other students or nurses to revise a policy and procedure or develop a new clinical protocol.

The literature Rick found reveals that rocking in a rocking chair after bowel surgery usually results in a quicker return of bowel function following surgery when compared with standard nursing care (Massey, 2010; Moore et al., 1995; Thomas et al., 1990). Rick then meets with his colleagues on the unit practice committee to recommend a protocol for patients who have abdominal surgery. The protocol outlines guidelines to have patients routinely sit in rocking chairs when they get out of bed after surgery.

Evidence is integrated in a variety of ways through teaching tools, clinical practice guidelines, policies and procedures, and new assessment or documentation tools. Depending on the amount of change needed to apply evidence in practice, it becomes necessary to involve a number of staff from a given nursing unit. It is important to consider the setting where you want to apply the evidence. Is there support from all staff? Does the practice change fit with the scope of practice in the clinical setting? Are resources (time, secretarial support, and staff) available to make a change? When evidence is not strong enough to apply in practice, your next option is to conduct a pilot study to investigate your PICOT question. A pilot study is a small-scale research study or one that includes a quality or performance improvement project.

Evaluate the Practice Decision or Change

After applying evidence in your practice, your next step is to evaluate the outcome. How does the intervention work? How effective was the clinical decision for your patient or practice setting? Sometimes your evaluation is as simple as determining if the expected outcomes you set for an intervention are met (see Chapters 18 and 20). For example, after the use of a transparent intravenous (IV) dressing, does the IV dislodge, or does the patient develop the complication of phlebitis? When using a new approach to preoperative teaching, does the patient learn what to expect after surgery?

When an EBP change occurs on a larger scale, an evaluation is more formal. For example, evidence showing factors that contribute to pressure ulcers might lead a nursing unit to adopt a new skin care protocol. To evaluate the protocol, nurses track the incidence of pressure ulcers over a course of time (e.g., 6 months to a year). In addition, they collect data to describe both patients who develop ulcers and those who do not. This comparative information is valuable in determining the effects of the protocol and whether modifications are necessary.

When evaluating an EBP change, determine if the change was effective, if modifications in the change are needed, or if the change needs to be discontinued. Events or results that you do not expect may occur. For example, a hospital that implements a new method of cleaning IV line puncture sites discovers an increased rate of IV line infections and reevaluates the new cleaning method to determine why infections have increased. If the hospital does not evaluate this change in practice, more patients will develop IV site infections. Never implement a practice change without evaluating its effect.

In Rick’s case the unit practice committee collects evaluation data after 3 months of implementing the rocking chair protocol to determine if patients experienced a lower incidence of postoperative ileus following abdominal surgery. After completing chart reviews, the committee discovers that patients who used the rocking chairs following abdominal surgery experienced fewer incidences of postoperative ileus compared with patients who did not use rockers before the protocol was implemented. The protocol patients went home 1 to 2 days sooner than the patients who did not use the rocking chairs. Patient interviews revealed that the patients were satisfied with the rocking movement and that, not only did the rocking chairs help them pass gas faster, but the patients also felt less anxious because of the rocking motion. After talking with the committee, Rick discovered that not all patients were able to use rocking chairs during this time because the unit did not have enough rocking chairs. He presented these data to his manager who approved the purchase of more rocking chairs.

Share the Outcomes with Others

After implementing an EBP change, it is important to communicate the results. If you implement an evidence-based intervention with one patient, you and the patient determine the effectiveness of that intervention. When a practice change occurs on a nursing unit level, the first group to discuss the outcomes of the change is often the clinical staff on that unit. To enhance professional development and promote positive patient outcomes beyond the unit level, share the results with various groups of nurses or other care providers such as the nursing practice council or the research council. Clinicians enjoy and appreciate seeing the results of a practice change. In addition, the practice change will more likely be sustainable and remain in place when staff are able to see the benefits of an EBP change.

As a professional nurse it is critical to contribute to the growing knowledge of nursing practice, especially if he or she is involved in an EBP change. Nurses often communicate the outcomes of EBP changes at professional conferences and meetings. Being involved in professional organizations allows them to present EBP changes in scientific abstracts, poster presentations, or even podium presentations.

After evaluating the results of the EBP change, Rick decides to present the outcomes to the nursing research committee at his hospital. The chief nursing officer hears Rick’s presentation and encourages him to submit an abstract about his EBP change to a national professional nursing conference. Rick submits his abstract for consideration as a poster presentation at the annual Midwest Nursing Research Society conference, and it is accepted. During the conference Rick tells other nurses about his EBP change and is contacted by several nurses after the conference who are thinking about implementing the use of rocking chairs on their patient care units.

Nursing Research

After completing a thorough review and critique of the scientific literature, you might not have enough strong evidence to make a practice change. Instead you may find a gap in knowledge that makes your PICOT question go unanswered. When this happens, the best way to answer your PICOT question is to conduct a research study. At this time in your career you will not be conducting research. However, it is important for you to understand the process of nursing research and how it generates new knowledge.

The International Council of Nurses (ICN) (2007) supports the need for nursing research as a means for improving the health and welfare of people. Nursing research is a way to identify new knowledge, improve professional education and practice, and use resources effectively. Research means to search again or to examine carefully. It is a systematic process that asks and answers questions to generate knowledge. The knowledge provides a scientific basis for nursing practice and validates the effectiveness of nursing interventions. Nursing research improves professional education and practice and helps nurses use resources effectively. The scientific knowledge base of nursing continues to grow today, thus furnishing evidence nurses can use to provide safe and effective patient care. Many professional and specialty nursing organizations support the conduct of research for advancing nursing science.

An example of how research can expand our practice can be seen in the work of Dr. Norma Metheny who has spent many years asking questions about how to prevent the aspiration of tube feeding in patients who receive feeding through nasogastric tubes (Metheny et al., 1988, 1989, 1990, 1994, 2000). Through her research she identified factors that increase the risk for aspiration and approaches to use in determining tube feeding placement. Dr. Metheny’s findings are incorporated into this textbook and have changed the way nurses administer tube feedings to patients. Through research Dr. Metheny has contributed to the scientific body of knowledge that has saved patients’ lives and helped to prevent the serious complication of aspiration.

Outcomes Management Research

The management of care delivery outcomes is a growing concern for nurse clinicians and researchers (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). Outcomes research assesses and documents the effectiveness of health care services and interventions. It responds to the increased demands from policy makers, insurers, and the public to justify care practices and systems in terms of improved patient outcomes and costs (Polit and Beck, 2007). For example, studying the effects of an outpatient education program on the ability of older adult patients to follow a nutrition and exercise program is an outcome study.

Care delivery outcomes are the observable or measurable effects of some intervention or action (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). As is the case with the expected outcomes you develop in a plan of care (see Chapter 18), a care delivery outcome focuses on the recipient of service (e.g., patient, family, or community) and not the provider (e.g., nurse or physician). For example, an outcome of a diabetes education program is that patients are able to self-administer insulin, not the nurses’ success in instructing all patients newly diagnosed with diabetes.

A problem in outcomes research is the clear definition or selection of measurable outcomes. Components of an outcome include the outcome itself, how it is observed (the indicator), its critical characteristics (how it is measured), and its range of parameters (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). For example, health care settings commonly measure the outcome of patient satisfaction when they introduce new services (e.g., new care delivery model or outpatient clinic). The outcome is patient satisfaction, observed through patients’ responses to a patient satisfaction instrument, including characteristics such as nursing care, physician care, support services, and the environment. Patients complete the instrument, responding to a scale (parameter) designed to measure their degree of satisfaction (e.g., scale of 1 to 5). The combined score on the instrument yields a measure of patient satisfaction, an outcome that the facility can track over time.

Although the nursing literature now addresses the identification of “nursing-sensitive outcomes” (Box 5-2), or outcomes that are sensitive to nursing practice (Ingersoll et al., 2010; Montalvo, 2007), researchers frequently choose outcomes that do not measure a true impact of care delivery, particularly nursing care delivery. For example, common outcome measures include morbidity, mortality, readmission rate, or length of stay. Although important outcomes to understand, they do not always measure the true effect of a specific nursing intervention on care delivery. For example, if a nurse researcher intends to measure the success of a nurse-initiated protocol to manage blood glucose levels in critically ill patients, the researcher will not likely measure mortality because it is too broad and susceptible to many factors (e.g., the selection of medical therapies, the patients’ acuity of illness) other than the nurse-initiated protocol. Instead, he or she will have a better idea of the effects of the protocol by measuring the outcome of patients’ blood glucose ranges. The nurse researcher obtains the blood glucose level of patients placed on the protocol and compares them to a desired range that represents good blood glucose control.

Scientific Method

The scientific method is the foundation of research and the most reliable and objective of all methods of gaining knowledge. This method is an advanced, objective means of acquiring and testing knowledge. Aspects of the method guide you in applying research evidence in practice and in conducting research. When using research findings to change practice, you need to understand the process that a researcher uses to guide a study. For example, when Rick considered whether to have the patients on his unit use a rocking chair following abdominal surgery, he needed to know if this had been tested on similar patients and the outcomes or results. The scientific method is a systematic, step-by-step process that provides support that the findings from a study are valid, reliable, and generalizable to subjects similar to those researched.

Researchers use the scientific method to understand, explain, predict, or control a nursing phenomenon (Polit and Beck, 2007). Systematic, orderly procedures characterize this method to limit the possibility for error, although it is not without fault. The scientific method minimizes the chance that bias or opinion by a researcher will influence the results of research and thus the knowledge gained. The characteristics of scientific research are as follows (Polit and Beck, 2007):

• The research identifies the problem area or area of interest to study.

• The steps of planning and conducting a research study occur in a systematic and orderly way.

• Researchers try to control external factors that are not being studied but can influence a relationship between the phenomena they are studying. For example, if a nurse is studying the relationship between diet and heart disease, he or she controls other characteristics among subjects such as stress or smoking history because they are contributing factors to this disease. Patients on a study diet and those on a regular diet would both have to have similar levels of stress and smoking histories to test the true effect of the diet.

• Researchers gather empirical data through the use of observations and assessments and use the data to discover new knowledge.

• The goal is to understand phenomena to apply the knowledge generally to a broad group of patients.

Nursing and the Scientific Approach

In the past much of the information used in nursing practice was borrowed from other disciplines such as biology, physiology, and psychology. Often nurses applied this information to their practice without testing it. For example, nurses use several methods to help patients sleep. Interventions such as giving a patient a back rub, making sure that the bed is clean and comfortable, and preparing the environment by dimming the lights are nursing measures that are used frequently and in general are logical, commonsense approaches. However, when these measures are considered in greater depth, questions arise about their applications. For example, are they the best methods to promote sleep? Do different patients in different situations require other interventions to promote sleep?

Research provides a way to study nursing questions and problems in greater depth within the context of nursing. If nurses do not use an evidence-based approach to practice, they often rely on personal experience or the statements of nursing experts alone. If an intervention works for most patients, you may become satisfied with this success without questioning whether there might be a better way for other patients. If the intervention is not successful, you might use an approach practiced by a colleague or try a different sequence of accepted measures. Even if an intervention discovered with this approach is effective for one or more patients, it is not always appropriate for other patients in other settings. Nursing interventions must be tested through research to determine the measures that work best with specific patients.

Nursing research addresses issues important to the discipline of nursing. Some of these issues relate to the profession itself, education of nurses, patient and family needs, and issues within the health care delivery system. Once research is completed, it is important to disseminate or communicate the findings. One method of dissemination is through publication of the findings in professional journals. Nursing research uses many methods to study clinical problems (Box 5-3). There are two broad approaches to research: quantitative and qualitative methods.

Quantitative Research

Quantitative nursing research is the study of nursing phenomena that offers precise measurement and quantification. For example, a study dealing with pain therapies quantitatively measures pain severity. A study testing different forms of surgical dressings measures the extent of wound healing. Quantitative research is the precise, systematic, objective examination of specific concepts. It focuses on numerical data, statistical analysis, and controls to eliminate bias in findings (Polit and Beck, 2007). Although there are many quantitative methods, the following sections briefly describe experimental, nonexperimental, survey, and evaluation research.

Experimental Research: An RCT is a true experimental study that tightly controls conditions to eliminate bias and ensure that findings can be generalizable to similar groups of subjects. Researchers test an intervention (e.g., new drug, therapy, or education method) against the usual standard of care (Box 5-4). They randomly assign subjects to either a control or treatment group. In other words, all subjects in a study have an equal chance to be in either group. The treatment group receives the experimental intervention, and the control group receives the usual standard of care. The researchers measure both groups for the same outcomes to see if there is a difference. When an RCT is completed, the researcher will know if the intervention leads to better outcomes than the standard of care.

Controlled trials without randomization are studies that test interventions, but researchers have not randomized the subjects into control or treatment groups. Thus there is bias in how the study is conducted. Some findings are distorted because of how the study was designed. A researcher wants to be as certain as possible when testing an intervention that the intervention is the reason for the desired outcomes. In a nonrandomized controlled trial the way in which subjects fall into the control or treatment group sometimes influences the results. This suggests that the intervention tested was not the only factor affecting the results of the study. Careful critique allows you to determine if bias were present in a study and what effect, if any, the bias had on the results of the study.

Although RCTs investigate cause and effect and are excellent for testing drug therapies or medical treatments, this approach is not always the best for testing nursing interventions. The nature of nursing care causes nurse researchers to ask questions that are not always answered best by an RCT. For example, nurses help patients with problems such as knowledge deficits and symptom management. Learning to understand how patients experience health problems cannot always be addressed through an RCT. Therefore nonexperimental descriptive studies are often used in nursing research.

Nonexperimental Research: Nonexperimental descriptive studies describe, explain, or predict phenomena such as factors that lead to an adolescent’s decision to smoke cigarettes and those that lead patients with dementia to fall in a hospital setting.

A case control study is one in which researchers study one group of subjects with a certain condition (e.g., asthma) at the same time as another group of subjects who do not have the condition. A case control study determines if there is an association between one or more predictor variables and the condition (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011). For example, is there an association between predictor variables such as family history or environmental exposure to dust and the incidence of asthma? Often a case control study is conducted retrospectively, or after the fact. Researchers look back in time and review available data about their two groups of subjects to understand what variables explain the condition. These studies involve a small number of subjects, creating a risk of bias. Sometimes the subjects in the two groups differ on certain other variables (e.g., amount of stress or history of contact allergies) that also influence the incidence of the condition, more so than the variables being studied. Correlational studies describe the relationship between two variables (e.g., the age of the adolescent and if the adolescent smokes). The researcher determines if the two variables are correlated or associated with one another and to what extent.

Many times researchers use findings from descriptive studies to develop studies that test interventions. For example, if the researcher determines that adolescents 15 years old and older tend to smoke, he or she might test if participation in a program about smoking for older adolescents is effective in helping adolescents stop smoking.

Surveys: Surveys are common in quantitative research. They obtain information from populations regarding the frequency, distribution, and interrelation of variables among subjects in the study (Polit and Beck, 2007). An example is a survey designed to measure nurses’ perceptions of physicians’ willingness to collaborate in practice. Surveys obtain information about practices, education, experience, opinions, and other characteristics of people. The most basic function of a survey is description. Surveys gather a large amount of data to describe the population and the topic of study. It is important in survey research that the population sampled be large enough to keep sampling error at a minimum.

Evaluation Research: Evaluation research is a form of quantitative research that determines how well a program, practice, procedure, or policy is working (Polit and Beck, 2007). An example is outcomes management research. Evaluation research determines why a program or some components of the program are successful or unsuccessful. When programs are unsuccessful, evaluation research identifies problems with the program and opportunities for change or barriers to program implementation.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative nursing research is the study of phenomena that are difficult to quantify or categorize such as patients’ perceptions of illness. This method describes information obtained in a nonnumerical form (e.g., data in the form of written transcripts from a series of interviews). Qualitative research offers answers when trying to understand patients’ experiences with health problems and the contexts in which the experiences occur. Patients have the opportunity to tell their stories and share their experiences in these studies. The findings are in depth because patients are usually very descriptive in what they choose to share. Examples of qualitative studies include “patient’s perceptions of nurses’ caring in a palliative care unit,” and “the perceptions of stress by family members of critically ill patients.”

Qualitative research involves inductive reasoning to develop generalizations or theories from specific observations or interviews (Polit and Beck, 2007). For example, a nurse extensively interviews cancer survivors and then summarizes the common themes from all of the interviews to inductively determine the characteristics of cancer survivors’ quality of life. Qualitative research involves the discovery and understanding of important behavioral characteristics or phenomena. An example is a qualitative research study conducted by Nixon and Narayanasamy (2010) that described the spiritual needs of patients with brain tumors and how well nurses support these needs.

There are a number of different qualitative research methods, including ethnography, phenomenology, and grounded theory. Each is based on a different philosophical or methodological view of how to collect, summarize, and analyze qualitative data.

Research Process

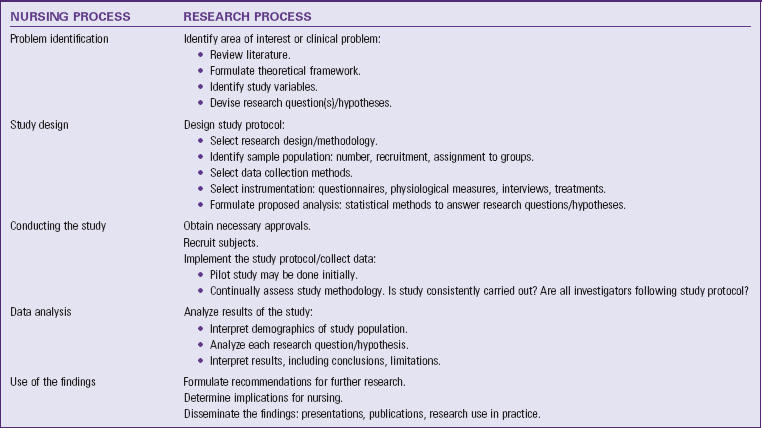

The research process is an orderly series of steps that allow a researcher to move from asking the research question to finding the answer. Usually the answer to the initial research question leads to new questions and other areas of study. The research process builds knowledge for use in other similar situations. For example, a nurse researcher might seek knowledge about why a particular event happens or the best way to provide care for patients with a certain health problem. The research process provides knowledge that a nurse can apply repeatedly to a whole group or class of patients. Table 5-2 summarizes steps of the research process. Initially the researcher identifies an area of inquiry (identifying a problem), which often results from clinical practice. For example, after speaking with a researcher at a professional nursing conference, Rick decides he wants to conduct a pilot study on the nursing unit to determine if chewing peppermint gum following colon surgery prevents patients from having nausea and reduces the incidence of postoperative ileus. He reviews the relevant literature to determine what is known about chewing peppermint gum and its effect on bowel mobility and nausea following abdominal surgery. Rick notes that, although many patients report problems with nausea and return of bowel function, there is limited research on the effects of chewing gum on these two outcomes.

Following identification of the problem and review of the literature, Rick designs a study with the help of a nurse researcher. The sample includes all patients who are having elective colon resections. Subjects are excluded if they need to have surgery because of an emergency situation. Rick places each subject into one of the two groups (experimental or control) based on random assignment. The control group receives standard postoperative care. The experimental or treatment group receives standard postoperative care, and they chew gum for 5 minutes three times a day. Subjects have a 50-50 chance of being in each group. Rick selects appropriate instruments to measure postoperative nausea and decides to use patient assessment data to determine when nurses first hear bowel sounds and when patients first pass flatus and have a bowel movement after surgery.

Before conducting any study with human subjects, the researcher obtains approvals from the agency’s human subjects committee or institutional review board (IRB). An IRB includes scientists and laypersons who review all studies conducted in the institution to ensure that ethical principles, including the rights of human subjects, are followed. Informed consent means that research subjects (1) are given full and complete information about the purpose of a study, procedures, data collection, potential harm and benefits, and alternative methods of treatment; (2) are capable of fully understanding the research and the implications of participation; (3) have the power of free choice to voluntarily consent or decline participation in the research; and (4) understand how the researcher maintains confidentiality or anonymity. Confidentiality guarantees that any information a subject provides will not be reported in any manner that identifies the subject and will not be accessible to people outside the research team.

Once Rick’s study begins, the nurses on his unit collect data as indicated in the study protocol. The team analyzes the data from the nausea instrument and the chart review about bowel function from the two groups studied. With the help of a statistician from the hospital, a comparison of the results determines whether patients who chewed peppermint gum experienced less nausea and a quicker return of bowel function than the patients who had standard nursing care. The results from this study will advance postoperative nursing care.

In any study a researcher must consider study limitations. Limitations are factors that affect study findings such as a small sample of subjects, a unique setting where the study was conducted, or the failure of the study to include representative cultural groups or age-groups. Rick’s team conducted a pilot study because little data were available about the benefits of chewing gum following abdominal surgery. The sample size only included 20 patients in each group, and it was challenging to collect all the data from the patient charts because of inconsistencies in documentation. Therefore the results of Rick’s study have limited generalizability to other patients who are experiencing abdominal surgery. The limitations in this study help Rick decide how to refine or adapt it for further investigation in the future.

A researcher also addresses the implications for nursing practice. This ultimately helps fellow researchers, clinicians, educators, and administrators know how to apply findings from a study in practice. At the conclusion of Rick’s study, the research team recommends that patients who have elective colon resections be offered the opportunity to chew peppermint gum following surgery. The surgeons on the unit agreed to the change in practice. The team decides to consider conducting future studies to investigate this intervention with patients who have other types of abdominal surgeries. In addition, the team suggests ways to effectively introduce the use of chewing gum into other surgical units following surgery.

Quality and Performance Improvement

Every health care organization gathers data on a number of health outcome measures as a way to gauge its quality of care. This is the focus of outcomes management. Examples of quality data include fall rates, number of medication errors, incidence of pressure ulcers, and infection rates. Health care organizations actively promote efforts for improving patient care and outcomes, particularly with respect to reducing medical errors and enhancing patient safety. Quality data are the outcome of both quality improvement (QI) and performance improvement (PI) initiatives. The Joint Commission (TJC, 2010a) defines quality improvement (QI) as an approach to the continuous study and improvement of the processes of providing health care services to meet the needs of patients and others and inform health care policy. The QI program of an institution focuses on improvement of health care–related processes (e.g., medication delivery or fall prevention). Performance measurement analyzes what an institution does and how well it does it. In performance improvement (PI) an organization analyzes and evaluates current performance and uses the results to develop focused improvement actions. PI activities are typically clinical projects conceived in response to identified clinical problems and designed to use research findings to improve clinical practice (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2011).

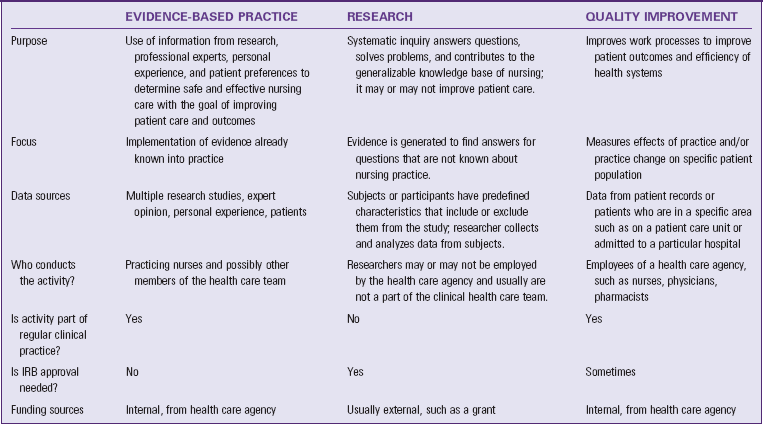

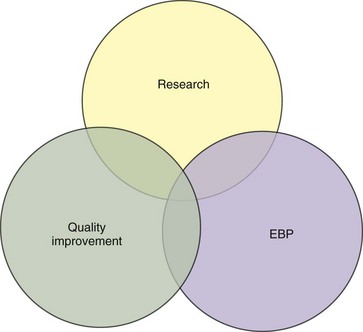

EBP, research, and quality improvement are closely interrelated (Fig. 5-3). Although you use all of these in nursing practice, it is important to know the similarities and differences between them (Table 5-3). When implementing an EBP project, it is important to first review evidence from appropriate research and QI data. The information helps you better understand the extent of a problem in practice and within your organization. QI data inform you about how processes work within an organization and thus offer information about how to make EBP changes. When implementing a research project, EBP and QI can inform opportunities for research. Rapid-cycle improvements measured through QI often identify gaps in evidence. Similarly EBP literature reviews often identify gaps in scientific evidence. Thus the two processes help to identify topics for research. When implementing a QI project, you consider information from research and EBP that aims to improve or better understand practice, thus helping to identify worthy processes to evaluate. Here is an example of how the three processes can merge to improve nursing practice. A nursing unit has an increase in the number of patient falls over the last several months. QI data identifies the type of patients who fall, time of day of falls, and possible precipitating factors (e.g., efforts to reach the bathroom, multiple medications, or patient confusion). A thorough analysis of QI data then leads clinicians to conduct a literature review and implement the best evidence available to prevent patient falls for the type of patients on the unit. Once the staff apply the evidence in a fall-prevention protocol, they implement the protocol (in this case, focusing efforts on care approaches during evening hours) and evaluate its results. Recurrent problems with falls may lead staff to conduct a research study.

TABLE 5-3

Similarities and Differences Among Evidence-Based Practice, Research, and Quality Improvement

FIG. 5-3 The overlapping relationship among research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement. EBP, Evidence-based practice.

Quality Improvement Programs

A well-organized QI program focuses on processes or systems that contribute to patient, staff, or system outcomes. A systematic approach ensures that all employees support a continuous QI philosophy. An organizational culture in which all staff members understand their responsibility toward maintaining and improving quality is essential. Typically in health care many individuals are involved in single processes of care. For example, medication delivery involves the nurse who prepares and administers the drugs, the health care provider who prescribes medications, the pharmacist who prepares the dosage, the secretary who communicates about new orders being written, and the transporter who delivers medications. All members of the health care team collaborate together in QI activities. As a member of the nursing team, you participate in recognizing trends in practice, identifying when recurrent problems develop, and initiating opportunities to improve the quality of care.

The QI process begins at the staff level, where problems are defined. This requires staff members to know the practice standards or guidelines that define quality. Unit QI committees review activities or services considered to be most important in providing quality care to patients. To identify the greatest opportunity for improving quality, the committees consider activities that are high-volume (greater than 50% of the activity of a unit), high-risk (potential for trauma or death), and problem areas (potential for patient, staff, or institution). TJC’s annual National Patient Safety Goals provide another focus for QI committees to explore and identify problem areas (TJC, 2010b) (see Chapter 38). Sometimes the problem is presented to a committee in the form of a sentinel event (i.e., an unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or psychological injury). Once a committee defines the problem, it applies a formal model for exploring and resolving quality concerns. There are many models for QI and PI. One model is the PDSA cycle: plan, do, study, and act:

Plan—Review available data to understand existing practice conditions or problems to identify the need for change.

Do—Select an intervention on the basis of the data reviewed and implement the change.

Study—Study (evaluate) the results of the change.

Act—If the process change is successful with positive outcomes, act on the practices by incorporating them into daily unit performance.

Six Sigma or Lean is another quality improvement model. In this model organizations carefully evaluate processes to reduce costs, enhance quality and revenue, and improve teamwork while using the talents of existing employees and the fewest resources. In a lean organization all employees are responsible and accountable for integrating quality improvement methodologies and tools into daily work (Kimsey, 2010).

Some organizations use a quality improvement model called rapid-cycle improvement or rapid-improvement event (RIE). RIEs are very intense, usually week-long events, in which a group gets together to evaluate a problem with the intent of making radical changes to current processes (Kimsey, 2010). Changes are made within a very short time. The effects of the changes are measured quickly, results are evaluated, and further changes are made when necessary. RIE is appropriate to use when a serious problem exists that greatly affects patient safety and needs to be solved quickly.

Once a QI committee makes a practice change, it is important to communicate results to staff in all appropriate organizational departments. Practice changes will likely not last when QI committees fail to report findings and results of interventions. Regular discussions of QI activities through staff meetings, newsletters, and memos are good communication strategies. Often a QI study reveals information that prompts organization-wide change. An organization must be responsible for responding to the problem with the appropriate resources. Revision of policies and procedures, modification of standards of care, and implementation of new support services are examples of ways an organization responds.

Key Points

• A challenge in EBP is to obtain the very best, most current information at the right time, when you need it for patient care.

• Using your clinical expertise and considering patients’ values and preferences ensures that you will apply the evidence in practice both safely and appropriately.

• The five steps of EBP provide a systematic approach to rational clinical decision making.

• The more focused a PICOT question is, the easier it will become to search for evidence in the scientific literature.

• The hierarchy of available evidence offers a guide to the types of literature or information that offer the best scientific evidence.

• A randomized controlled trial is the highest level of experimental research.

• Expert clinicians are a rich source of evidence because they use it frequently to build their own practice and solve clinical problems.

• The critique or evaluation of evidence includes determining the value, feasibility, and usefulness of evidence for making a practice change.

• After critiquing all articles for a PICOT question, synthesize or combine the findings to consider the scientific rigor of the evidence and whether it has application in practice.

• When you decide to apply evidence, consider the setting and whether there is support from staff and available resources.

• Research is a systematic process that asks and answers questions that generate knowledge, which provides a scientific basis for nursing practice.

• Outcomes research is designed to assess and document the effectiveness of health care services and interventions.

• Nursing research involves two broad approaches for conducting studies: quantitative and qualitative methods.

• The research process usually consists of the following steps: identifying the problem, designing the study, conducting the study, analyzing the data, and using the findings.

• A thorough analysis of QI data leads clinicians to understand work processes and the need to change practice.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

The nursing staff on Rick’s postsurgical unit have been reviewing their patients’ medical records and have seen a steady increase in the incidence of pressure ulcers over the last 3 months, especially in patients who are incontinent. Rick speaks with the wound care specialist in the hospital about this issue. The specialist recommends that the nurses try using special wipes that include an emollient to clean patients who are incontinent.

1. Rick and the nursing staff decide to approach this practice change using evidence-based practice. What would be a PICOT question for this group to ask? Identify each part of the PICOT question.

2. Rick conducts a literature search and gathers research articles about the PICOT question. He evaluates the scientific merit of each of the articles and determines that he has sufficient evidence to answer the PICOT question. Which step of the evidence-based practice process has Rick completed?

3. Rick and the staff on the postsurgical unit implemented a new skin care protocol for patients who are incontinent after surgery. The protocol has been implemented for 4 months. Rick needs to determine if this practice change has been effective. What outcome does Rick need to measure? Describe one method he could use to measure this outcome.

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. A nurse researcher interviews parents of children who have diabetes and asks them to describe how they deal with their child’s illness. The analysis of the interviews yields common themes and stories describing the parents’ coping strategies. This is an example of which type of study?

2. A nurse who works in a newborn nursery asks, “I wonder if the moms who breastfeed their babies would be able to breastfeed more successfully if we played peaceful music while they were breastfeeding.” In this example of a PICOT question, the I is:

3. A nurse researcher conducts a study that randomly assigns 100 patients who smoke and attend a wellness clinic into two groups. One group receives the standard smoking cessation handouts; the other group takes part in a new educational program that includes a smoking cessation support group. The nurse plans to compare the effectiveness of the standard treatment with the educational program. What type of a research study is this?

4. A group of nurses have implemented an evidence-based practice (EBP) change and have evaluated the effectiveness of the change. Their next step is to:

1. Conduct a literature review.

2. Share the findings with others.

5. Arrange the following steps of evidence-based practice (EBP) in the appropriate order:

2. Ask the burning clinical question.

3. Evaluate the practice decision or change.

4. Share the results with others.

6. When recruiting subjects to participate in a study about the effects of an exercise program on balance, the researcher provides full and complete information about the purpose of the study and gives the subjects the choice to participate or not participate in the study. This is an example of:

7. Nurses on a pediatric nursing unit are discussing ways to improve patient care. One nurse asks a colleague, “I wonder how best to measure pain in a child who has sickle cell disease?” This question is an example of a/an:

8. The nurses on a medical unit have seen an increase in the number of pressure ulcers that develop in their patients. They decide to initiate a quality improvement project using the PDSA model. Which of the following is an example of “Do” from that model?

1. Implement the new skin care protocol on all medicine units.

2. Review the data collected on patients cared for using the protocol.

3. Review the QI reports on the six patients who developed ulcers over the last 3 months.

4. Based on findings from patients who developed ulcers, implement an evidence-based skin care protocol.

9. A nurse researcher decides to complete a study to evaluate how Florence Nightingale improved patient outcomes in the Crimean War. This is an example of what type of research?

10. A group of nurses on the research council of a local hospital are measuring nursing-sensitive outcomes. Which of the following is a nursing-sensitive outcome that the nurses need to consider measuring?

1. Incidence of asthma among children of parents who smoke

2. Frequency of low blood sugar episodes in children at a local school

3. Number of patients who fall and experience subsequent injury on the evening shift

4. Number of sexually active adolescent girls who attend the community-based clinic for birth control

11. A group of staff nurses notice an increased incidence of medication errors on their unit. After further investigation it is determined that the nurses are not consistently identifying the patient correctly. A change is needed quickly. What type of quality improvement method would be most appropriate?

12. A nurse is providing care to a patient who is experiencing major abdominal trauma following a car accident. The patient is losing blood quickly and needs a blood transfusion. The nurse finds out that the patient is a Jehovah’s Witness and cannot have blood transfusions because of religious beliefs. He or she notifies the patient’s health care provider and receives an order to give the patient an alternative to blood products. This is an example of:

1. A quality improvement study.

2. An evidence-based practice change.

3. A time when calling the hospital’s ethics committee is essential.

4. Considering the patient’s preferences and values while providing care.

13. A group of staff educators are reading a research study together at a journal club meeting. While reviewing the study, one of the nurses states that it evaluates if newly graduated nurses progress through orientation more effectively when they participate in patient simulation exercises. Which part of the research process is reflected in this nurse’s statement?

14. A research study is investigating the following research question: What is the effect of the diagnosis of breast cancer on the roles of the family? In this study “the diagnosis of breast cancer” and “family roles” are examples of:

15. A nurse researcher is developing a research proposal and is in the process of selecting an instrument to measure anxiety. In which part of the research process is this nurse?

Answers: 1. 2; 2. 3; 3. 4; 4. 2; 5. 2, 6, 5, 1, 3, 4; 6. 4; 7. 4; 8. 1; 9. 1; 10. 3; 11. 3; 12. 4; 13. 2; 14. 3; 15. 2.

References

Ingersoll, GL, et al. Meeting Magnet® research and evidence-based practice expectations through hospital-based research centers. Nurs Econ. 2010;28(4):226.

International Council of Nurses. Nursing research: ICN position statement. http://www.icn.ch/images/stories/documents/publications/position_statements/B05_Nsg_Research.pdf, 2007. [Accessed June 23, 2011].

Kimsey, DB. Lean methodology in health care. AORN J. 2010;92(1):53.

Makadon, HJ, et al. Value management: optimizing quality, service, and cost. J Healthc Qual. 2010;32(1):29.

Melnyk, BM, Fineout-Overholt, E. Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: a guide to best practice, ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Montalvo, I, The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI). Online J Issues Nurs 2007;12(3). http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Volume122007/No3Sept07/NursingQualityIndicators.aspx [Accessed October 14, 2010].

Oncology Nursing Society. Evidence-based practice resource area. n.d. http://onsopcontent.ons.org/toolkits/evidence/. [Accessed October 2010].

Polit, DF, Beck, CT. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, ed 8. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

Sackett, DL, et al. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

Stilwell, SB, et al. Asking the clinical question: a key step in evidence-based practice. Am J Nurs. 2010;110(3):58.

The Joint Commission (TJC). Performance measurement. http://www.jointcommission.org/PerformanceMeasurement/, 2010. [Accessed October 16, 2010].

The Joint Commission (TJC). 2010 National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs). http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/. [Accessed October 16, 2010].

Research References

Massey, RL. A randomized trial of rocking-chair motion on the effect of postoperative ileus duration in patients with cancer recovering from abdominal surgery. Appl Nurs Res. 2010;23(2):59.

Metheny, N, et al. Measures to test placement of nasogastric and nasointestinal feeding tubers: a review. Nurs Res. 1988;37:324.

Metheny, N, et al. Effectiveness of pH measurement in predicting feeding tube placement. Nurs Res. 1989;38(5):262.

Metheny, N, et al. Effectiveness of the auscultatory method in predicting feeding tube location. Nurs Res. 1990;39(5):262.

Metheny, N, et al. Visual characteristics of aspirates from feeding tubes as a method for predicting tube location. Nurs Res. 1994;43:282.

Metheny, N, et al. Development of a reliable and valid bedside test for bilirubin and its utilization for improving prediction of feeding tube location. Nurs Res. 2000;49(6):202.

Moore, CL, et al. Clinical process variation: effect on quality and cost of care. Am J Managed Care. 2010;16(5):385.

Moore, L, et al. Investigation of rocking as a postoperative intervention to promote gastrointestinal motility. Gastroenterol Nurs. 1995;18(3):87.

Nixon, A, Narayanasamy, A. The spiritual needs of neuro-oncology patients from patients’ perspective. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(15–16):2259.

Oh, EG, et al. Integrating evidence-based practice into RN-to-BSN clinical nursing education. J Nurs Ed. 2010;49(7):387.

Scott, K, McSherry, R. Evidence-based nursing: clarifying the concepts for nurses in practice. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(8):1085.

Thomas, L, et al. The effects of rocking, diet modifications, and antiflatulant medication of postcesarean section gas pain. J Perinatal Neonatal Nurs. 1990;4(3):12.

Titler, MG, et al. The Iowa model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Crit Care Clin North Am. 2001;13(4):497.