Care of Surgical Patients

• Explain the concept of perioperative nursing care.

• Differentiate among classifications of surgery and types of anesthesia.

• Describe the assessment data to collect for a surgical patient.

• Demonstrate postoperative exercises: diaphragmatic breathing, coughing, incentive spirometer use, turning, and leg exercises.

• Design a preoperative teaching plan.

• Prepare a patient for surgery.

• Explain the nurse’s role in the operating room.

• Describe the rationale for nursing interventions designed to prevent postoperative complications.

• Explain the differences and similarities in caring for ambulatory versus inpatient surgical patients.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Perioperative nursing care is nursing care given before (preoperative), during (intraoperative), and after (postoperative) surgery. It takes place in hospitals, surgical centers attached to hospitals, freestanding surgical centers, or health care providers’ offices. Perioperative nursing is a fast-paced, changing, and challenging field. It is based on the nurse’s understanding of several important principles, including:

• High-quality and patient safety–focused care.

• Effective therapeutic communication and collaboration with the patient, the patient’s family, and the surgical team.

• Effective and efficient assessment and intervention in all phases of surgery.

When you work in a perioperative setting, you need to practice strict surgical asepsis, thoroughly document care, and emphasize patient safety in all phases of care. Effective teaching and discharge planning prevent or minimize complications and ensure quality outcomes. The nursing process provides a basis for perioperative nursing, with the nurse individualizing strategies throughout the perioperative period so the patient has a smooth course from admission into the health care system through convalescence. Continuity of care is stressed in the perioperative model.

Care of the patient having surgery has shifted from hospital-based to home-based convalescence, with responsibility shifting to the patient and/or family. As the length of hospital stay decreases, the educational needs of the patient undergoing a surgical procedure increase. Patients return home with complex medical/surgical conditions that require both education and follow-up. Proper patient education is essential to ensuring positive surgical outcomes.

History of Surgical Nursing

The discipline of surgery progressed as a science in the twentieth century to give physicians the means to treat conditions that were difficult or impossible to manage with medicine alone. In 1956 the Association of Operating Room Nurses (AORN) was formed to gain knowledge of surgical principles and explore methods to improve nursing care of surgical patients. The organization is now known as the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses; however, AORN is still its acronym. AORN is the driving force for the practice of perioperative nursing and has developed standards of nursing practice that outline the scope of responsibility of the perioperative nurse. It was the first nursing organization to develop structure, process, and outcome standards as defined by the American Nurses Association (ANA). Current standards of perioperative professional practice include a patient-centered model of care with focus on (1) clinical practice, (2) professional practice, (3) administrative practice, (4) patient outcomes, and (5) quality improvement (AORN, 2011).

Ambulatory Surgery

During the 1970s the advent of ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), also referred to as outpatient surgery, short-stay surgery, or same-day surgery, changed the perioperative process. Centers providing these services are hospital-based or freestanding surgical centers. Starting in 1982 Medicare began paying for surgeries performed in ASCs, and now over half of all elective surgical procedures occur on an outpatient basis. This increase is the result of payer changes and advances in medical technology. These procedures include ophthalmic, gastroenterological, gynecological, eye-ear-nose-throat, orthopedic, cosmetic/restorative, and general (Ambulatory Surgery Center Association, 2010). Many patients are discharged the day of surgery following reversal of the anesthetic agent. One-day surgery, in which the patient is admitted the day of surgery and observed overnight (23-hour admission), also occurs.

There are benefits for the patient who has ambulatory surgery. Anesthetic drugs that metabolize rapidly with few aftereffects allow shorter operative times and faster recovery time. Ambulatory surgery also offers cost savings by eliminating the need for hospital stays, thus reducing the possibility of acquiring health care–associated infections (HAIs). For example, many abdominal procedures such as gallbladder removal (cholecystectomy) are now performed using laparoscopic procedures. Laparoscopic surgery involves the use of minimally invasive techniques with small incisions and cameras or scopes for performance of the surgery as opposed to a large incision required for an open surgery. Because of the small incision, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy involves only a few hours to a 24-hour hospital stay and a recovery period of a week. By contrast, an open cholecystectomy involves a larger abdominal incision with a hospitalization of 1 to 3 days and up to a 4-week recovery period. Advances in medical technology have made laparoscopic procedures more commonplace and less risky. Thus many surgeons use them instead of traditional surgical procedures, thereby decreasing the length of surgery, hospitalization, and associated costs.

Scientific Knowledge Base

The types of surgical procedures are classified according to seriousness, urgency, and purpose (Table 50-1). Some procedures fall into more than one classification. For example, surgical removal of a disfiguring scar is minor in seriousness, elective in urgency, and reconstructive in purpose. Frequently the classes overlap. An urgent procedure is also major in seriousness. Sometimes the same operation is performed for different reasons on different patients. For example, a gastrectomy may be performed as an emergency procedure to resect a bleeding ulcer or as an urgent procedure to remove a cancerous growth. The classification indicates the level of care a patient requires. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) assigns classification based on a patient’s physiological condition independent of the proposed surgical procedure (Table 50-2). Anesthesia always involves risks even in healthy patients, but certain patients are at higher risk, including those who are volume depleted or who have poor cardiac function (Rothrock, 2007). ASA physical status classes 1 and 2 and also stable class 3 are now acceptable for ambulatory surgery. Classes 4 and 5 require inpatient surgery.

TABLE 50-1

Classification of Surgical Procedures

TABLE 50-2

Physical Status (PS) Classification of the American Society of Anesthesiologists

Modified from Physical Status (PS) Classification. Reprinted with permission of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 520 N. Northwest Highway, Park Ridge, Illinois, 60068-2573, http://www.asahq.org/clinical/physicalstatus.htm, 2010.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Nurses made significant contributions demonstrating the benefit of preoperative education and preparation on positive patient outcomes following surgery. Structured preoperative teaching includes the AORN (2011) standards to prevent pulmonary and circulatory complications. Educating a patient before surgery can lead to increased patient satisfaction and decreased anxiety (Rosen, 2008).

Significant evidence-based knowledge is also available for proper wound care interventions. Nursing research contributes to our knowledge of the characteristics of wound healing and the types of applications most likely to be beneficial after surgery. Chapter 48 describes in detail a variety of interventions used to treat wounds, including surgical wounds.

Within the operating room (OR) setting, nursing knowledge improves the standards for infection control and patient safety. Evidence-based practice changes within the OR improve the quality of care for surgical patients and ultimately patient outcomes.

Critical Thinking

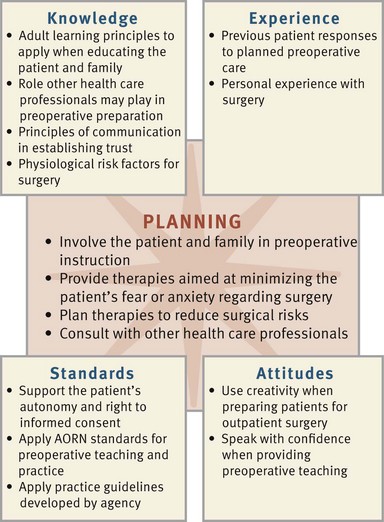

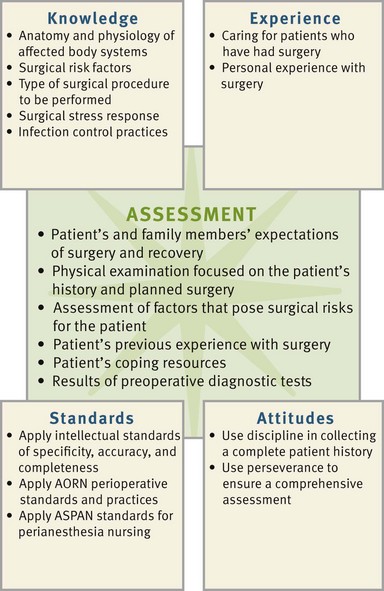

Successful critical thinking synthesizes knowledge, information gathered from patients, previous experience, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require you to anticipate the necessary information, analyze the data, and make decisions about patient care. A patient’s condition is always changing. During assessment (Fig. 50-1) consider all of the elements that build toward making appropriate nursing diagnoses.

FIG. 50-1 Critical thinking model for surgical patient assessment. AORN, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses; ASPAN, American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses.

When caring for the perioperative patient, integrate knowledge from anatomy and physiology, pathophysiology, and the surgical stress response, along with previous experiences in caring for surgical patients. Apply this knowledge using a patient-centered care approach to making clinical decisions. The use of critical thinking attitudes ensures that a plan of care is comprehensive and incorporates evidence-based principles for successful perioperative care (e.g., airway management, infection control, pain management, and discharge planning). The use of professional standards developed by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) (http://www.ahrq.gov), AORN (http://www.aorn.org), the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN) (http://www.aspan.org), and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) (http://www.asahq.org) provides valuable guidelines for perioperative management and evaluation of process and outcomes. Always review these guidelines within the context of new emerging evidence-based practice, agency policies, and the scope of practice of the state in which you practice.

Preoperative Surgical Phase

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

Patients having surgery enter the health care setting in different stages of health. A patient may enter the hospital or ambulatory surgical center on a predetermined day feeling relatively healthy and prepared to face elective surgery. In contrast, a person in a motor vehicle crash may face emergency surgery with no time to prepare. The ability to establish rapport and maintain a professional relationship with the patient is an essential component of the preoperative phase. You must do this quickly, with compassion and effectiveness.

The patient meets many health care personnel, including surgeons, nurse anesthetists, anesthesiologists, surgical technologists, and nurses. All play a role in the patient’s care and recovery. Family members attempt to provide support through their presence but face many of the same stressors as the patient. You need to effectively communicate with the patient and family because the nurse-patient relationship is the foundation of care (see Chapter 24). Assess the patient’s physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being and cultural heritage; recognize the degree of surgical risk; coordinate diagnostic tests; identify nursing diagnoses and nursing interventions; and establish outcomes in collaboration with the patient and the patient’s family. Communicate pertinent data and the plan of care to the surgical team members.

Assessment

A thorough patient assessment and critical analysis of findings ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. The aim of the preoperative assessment is to identify the patient’s normal preoperative function to recognize, prevent, and minimize possible postoperative complications. Ambulatory and same-day surgical programs offer challenges in gathering a complete assessment in a short time. A multidisciplinary team approach is essential. Patients are admitted only hours before surgery; thus it is important for you to organize and verify data obtained before surgery and implement a perioperative plan of care. This occurs both in ASCs and with patients who require a hospital stay.

Most assessments begin before admission for surgery—in the health care provider’s office, preadmission clinic, or anesthesia clinic or by telephone. Some patients answer a self-report inventory. Other times a health care provider performs a physical examination or orders laboratory tests. Before surgery nurses begin teaching, answer questions, and begin paperwork. This streamlines the care required by the patient on the day of surgery.

So as not to waste time duplicating information from the preoperative examination, focus on key measurements for all body systems to ensure that no one overlooked any obvious problems. Also make sure that the patient understands any previous education. Even though the surgeon screens the patient before scheduling surgery, preoperative assessment occasionally reveals an abnormality that delays or cancels surgery. For example, consider an infection in a patient with a cough and low-grade fever on admission and notify the surgeon immediately.

Through the Patient’s Eyes: Individualize each plan of care to be patient centered, including the patient’s expectations of surgery and the road to recovery. Does the patient expect full pain relief or simply to have his or her pain reduced? Does the patient expect to be independent immediately after surgery, or does he or she expect to be fully dependent on the nurse or family? These are only a few of the questions that you need to ask to establish a plan of care that matches the patient’s needs and expectations. It is important to consider the patient’s values as they relate to the nature of surgery. Also be sure to incorporate any of his or her previous experiences with surgery (e.g., pain, ability to advance through postoperative exercises, experience with diet) so your current assessment is accurate and relevant. Findings often reveal patient preferences to postoperative care allowing for a more individualized care approach.

Nursing History: Conduct an initial interview to collect a patient history similar to that described in Chapter 30. If a patient is unable to relate all of the necessary information, rely on family members as resources.

Medical History: A review of the patient’s medical history includes past illnesses and surgeries and the primary reason for seeking medical care. The patient’s current medical record and medical records from past hospitalizations are excellent sources of data. Preexisting illnesses influence patients’ abilities to tolerate surgery and nurses’ choices of therapies to help them reach full recovery (Table 50-3). The history of previous surgery influences the level of physical care required after an upcoming surgical procedure. Screen patients scheduled for ambulatory surgery for medical conditions that increase the risk for complications during or after surgery. For example, a patient who has a history of heart failure may experience a further decline in cardiac function during and after surgery. The patient with heart failure in the preoperative period may require beta-blocker medications, intravenous (IV) fluids infused at a slower rate, or administration of a diuretic after blood transfusions. Box 50-1 highlights an example of a focused assessment for a patient with a cardiac history.

TABLE 50-3

Medical Conditions That Increase Risks of Surgery

| TYPE OF CONDITION | REASON FOR RISK |

| Bleeding disorders (thrombocytopenia, hemophilia) | Increase risk of hemorrhage during and after surgery. |

| Diabetes mellitus | Increases susceptibility to infection and impairs wound healing from altered glucose metabolism and associated circulatory impairment. Stress of surgery often results in hyperglycemia (Lewis et al., 2011). |

| Heart disease (recent myocardial infarction, dysrhythmias, heart failure) and peripheral vascular disease | Stress of surgery causes increased demands on myocardium to maintain cardiac output. General anesthetic agents depress cardiac function. |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | Administration of opioids increases risk of airway obstruction after surgery. Patients desaturate as revealed by drop in oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry. |

| Upper respiratory infection | Increases risk of respiratory complications during anesthesia (e.g., pneumonia and spasm of laryngeal muscles). |

| Liver disease | Alters metabolism and elimination of drugs administered during surgery and impairs wound healing and clotting time because of alterations in protein metabolism. |

| Fever | Predisposes patient to fluid and electrolyte imbalances and may indicate underlying infection. |

| Chronic respiratory disease (emphysema, bronchitis, asthma) | Reduces patient’s means to compensate for acid-base alterations (see Chapter 41). Anesthetic agents reduce respiratory function, increasing risk for severe hypoventilation. |

| Immunological disorders (leukemia, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS], bone marrow depression, and use of chemotherapeutic drugs or immunosuppressive agents) | Increases risk of infection and delayed wound healing after surgery. |

| Abuse of street drugs | People abusing drugs sometimes have underlying disease (human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], hepatitis) that affects healing. |

| Chronic pain | Regular use of pain medications often results in higher tolerance. Increased doses of analgesics are sometimes necessary to achieve postoperative pain control. |

Risk Factors: Various conditions and factors increase a person’s risk in surgery. Knowledge of risk factors enables you to take necessary precautions in planning care.

Age: Very young and older adults are at risk for complications because of immature or declining physiological status. Mortality rates are higher in very young and very old surgical patients. During surgery nurses and health care providers are especially concerned with maintaining an infant’s normal body temperature. The infant has an underdeveloped shivering reflex, and often wide temperature variations occur. Anesthesia adds to the risk because anesthetics often cause vasodilation and heat loss.

During surgery an infant has difficulty maintaining a normal circulatory blood volume. He or she has considerably less total blood volume than an older child or adult. Even a small amount of blood loss is serious. A reduced circulatory volume makes it difficult for the infant to respond to increased oxygen demands during surgery. In addition, the infant is highly susceptible to complications associated with dehydration. However, if blood or fluids are replaced too quickly, overhydration may occur. Other unique aspects of a child’s surgical care include airway management, management of temperature alterations, and treatment of emergence delirium or delayed emergence from anesthesia.

With advancing age patients have less physical capacity to adapt to the stress of surgery because of deterioration in certain body functions. Perioperative registered nurses (RNs) should recognize the physiological, cognitive/psychological, and sociological changes associated with aging and understand that age alone puts older adults at risk for surgical complications (AORN, 2010). Despite the risk, the majority of patients undergoing surgery are older adults. Table 50-4 summarizes physiological factors that place older patients at risk during surgery.

TABLE 50-4

Physiological Factors That Place the Older Adult at Risk During Surgery

| ALTERATIONS | RISKS | NURSING IMPLICATIONS |

| Cardiovascular System | ||

| Degenerative change in myocardium and valves | Decreased cardiac reserve puts older adults at risk for decreased cardiac output, especially during times of stress (AORN, 2010) | Assess baseline vital signs for tachycardia, fatigue, and arrhythmias (AORN, 2010). |

| Rigidity of arterial walls and reduction in sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation to the heart | Alterations predispose patient to postoperative hemorrhage and rise in systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Maintain adequate fluid balance to minimize stress to the heart. Ensure that blood pressure level is adequate to meet circulatory demands. |

| Increase in calcium and cholesterol deposits within small arteries; thickened arterial walls | Predispose patient to clot formation in lower extremities | Instruct patient in techniques of leg exercises and proper turning. Apply elastic stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices. Administer anticoagulants as ordered by health care provider. Provide education regarding effects, side effects, and dietary considerations. |

| Integumentary System | ||

| Decreased subcutaneous tissue and increased fragility of skin | Prone to pressure ulcers and skin tears | Assess skin every 4 hours; pad all bony prominences during surgery. Turn or reposition at least every 2 hours. |

| Pulmonary System | ||

| Decreased respiratory muscle strength and cough reflex (AORN, 2010) | Increased risk for atelectasis | Instruct patient in proper technique for coughing, deep breathing, and use of spirometer. Ensure adequate pain control to allow for participation in exercises. |

| Reduced range of movement in diaphragm | Residual capacity (volume of air is left in lung after normal breath) increased, reducing amount of new air brought into lungs with each inspiration | When possible, have patient ambulate and sit in chair frequently. |

| Stiffened lung tissue and enlarged air spaces | Blood oxygenation reduced | Obtain baseline oxygen saturation; measure throughout perioperative period. |

| Gastrointestinal System | ||

| Gastric emptying delayed | Increases the risk for reflux and indigestion (AORN, 2010) | Position patient with head of bed elevated at least 45 degrees. Reduce size of meals in accordance with ordered diet. |

| Renal System | ||

| Decreased renal function, with reduced blood flow to kidneys | Increased risk of shock when blood loss occurs; increased risk for fluid and electrolyte imbalance (AORN, 2010) | For patients hospitalized before surgery, determine baseline urinary output for 24 hours. |

| Reduced glomerular filtration rate and excretory times | Limits ability to eliminate drugs or toxic substances | Assess for adverse response to drugs. |

| Decreased bladder capacity | Increases the risk for urgency, incontinence, and urinary tract infections (AORN, 2010) (Sensation of need to void often does not occur until bladder is filled) | Instruct patient to notify nurse immediately when sensation of bladder fullness develops. Keep call light and bedpan within easy reach. Toilet every 2 hours or more frequently if indicated. |

| Neurological System | ||

| Sensory losses, including reduced tactile sense and increased pain tolerance | Decreased ability to respond to early warning signs of surgical complications | Inspect bony prominences for signs of pressure that patient is unable to sense. Orient patient to surrounding environment. Observe for nonverbal signs of pain. |

| Blunted febrile response during infection (AORN, 2010) | Increased risk of undiagnosed infection | Ensure careful, close monitoring of patient temperature; provide warm blankets; monitor heart function; warm intravenous fluids (AORN, 2010). |

| Decreased reaction time | Confusion and delirium after anesthesia; increased risk for falls | Allow adequate time to respond, process information, and perform tasks. Perform fall risk screening and institute fall precautions. Screen for delirium with validated tools. Orient frequently to reality and surroundings. |

| Metabolic System | ||

| Lower basal metabolic rate | Reduced total oxygen consumption | Ensure adequate nutritional intake when diet is resumed but avoid intake of excess calories. |

| Reduced number of red blood cells and hemoglobin levels | Reduced ability to carry adequate oxygen to tissues | Administer necessary blood products. Monitor blood test results and oxygen saturation. |

| Change in total amounts of body potassium and water volume | Greater risk for fluid or electrolyte imbalance | Monitor electrolyte levels and supplement as necessary. Provide cardiac monitoring (telemetry) as needed. |

Nutrition: Before surgery assess if the patient is on a therapeutic diet and if there are any factors influencing food intake such as ability to chew and swallow and the presence of regurgitation after meals. This affects your choice of postoperative foods and liquids. In addition, normal tissue repair and resistance to infection depend on adequate nutrients. Surgery intensifies this need. After surgery a patient requires at least 1500 kcal/day to maintain energy reserves. Increased protein, vitamins A and C, and zinc facilitate wound healing (see Chapters 44 and 48). A patient who is malnourished is prone to poor tolerance to anesthesia, negative nitrogen balance from lack of protein, delayed blood-clotting mechanisms, infection, and poor wound healing. Assess the patient’s weight and height to determine body mass index. Many hospitalized patients display some degree of malnutrition. If a patient has elective surgery, attempt to correct nutritional imbalances before surgery. However, if a patient who is malnourished must undergo an emergency procedure, efforts to restore nutrients occur after surgery.

Obesity: Obesity increases surgical risk by reducing ventilatory and cardiac function. Obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and heart failure are common in the bariatric (obese) population. Embolus, atelectasis, and pneumonia are common postoperative complications in the patient who is obese. He or she often has difficulty resuming normal physical activity after surgery and is susceptible to poor wound healing and wound infection because of the structure of fatty tissue, which contains a poor blood supply. This slows delivery of essential nutrients, antibodies, and enzymes needed for wound healing (see Chapter 48). It is often difficult to close the surgical wound of a patient who is obese because of the thick adipose layer; thus he or she is at risk for dehiscence (opening of the suture line) and evisceration (abdominal contents protruding through surgical incision).

Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a syndrome of periodic, partial, or complete obstruction of the upper airway during sleep. Patients with diagnosed OSA have an increased incidence of postoperative complications, the most frequent being oxygen desaturation (Liao et al., 2009). Assess for a history of diagnosed OSA and use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV), or apnea monitoring. Instruct patients who use CPAP or NIPPV to bring their machine to the hospital or surgery center. Many patients with OSA are undiagnosed; thus it is becoming standard practice to assess for risk of OSA before surgery. It is necessary to ask the patient and sleep partner about symptoms of OSA such as snoring, apnea during sleep, frequent arousals during sleep, morning headaches, daytime somnolence, and chronic fatigue (ASA, 2006; Seet and Chung, 2010).

Immunocompromise: Patients with conditions that alter immune function are more at risk for developing infection after surgery. Examples include patients with cancer, bone marrow alterations, and those who undergo radiation therapy. Radiation is sometimes given before surgery to reduce the size of a cancerous tumor so it can be removed surgically. It has some unavoidable effects on normal tissue such as excess thinning of skin layers, destruction of collagen, and impaired vascularization of tissue. Ideally the surgeon waits to perform surgery 4 to 6 weeks after completion of radiation treatments. Otherwise the patient may face serious wound-healing problems. In addition, the use of chemotherapeutic drugs for cancer treatment, immunosuppressive medications for preventing rejection after organ transplantation, and steroids for treating a variety of inflammatory or autoimmune conditions increases the risk for infection.

Fluid and Electrolyte Imbalance: The body responds to surgery as a form of trauma. Severe protein breakdown causes a negative nitrogen balance (see Chapter 44) and hyperglycemia. Both of these effects decrease tissue healing and increase the risk of infection. As a result of the adrenocortical stress response, the body retains sodium and water and loses potassium within the first 2 to 5 days after surgery. The severity of the stress response influences the degree of fluid and electrolyte imbalance. Extensive surgery results in a greater stress response. A patient who is hypovolemic or who has serious preoperative electrolyte alterations is at significant risk during and after surgery. For example, an excess or depletion of potassium increases the chance of dysrhythmias during or after surgery. If the patient has preexisting diabetes mellitus or renal, gastrointestinal (GI), or cardiovascular abnormalities, the risk of fluid and electrolyte alterations is even greater.

Pregnancy: The perioperative plan of care addresses not one, but two patients: the mother and the developing fetus. The pregnant patient has surgery only on an emergent or urgent basis. Because all of the mother’s major systems are affected during pregnancy, the risk for intraoperative complications is increased. General anesthesia is administered with caution because of the increased risk of fetal death and preterm labor. Psychological assessment of mother and family is essential.

Perceptions and Knowledge Regarding Surgery: A patient’s past experience with surgery influences physical and psychological responses to a procedure. Assess the patient’s previous experiences with surgery as a foundation for anticipating his or her needs, providing teaching, addressing fears, and clarifying concerns. Ask the patient to discuss the previous type of surgery, level of discomfort, extent of disability, and overall level of care required. Address any complications that the patient experienced. It is also important to assess patients for motion sickness and nausea and vomiting during previous surgeries since these factors increase the risk for aspiration (McCaffrey, 2007). Prior anesthesia records are a useful source of information if previous problems occurred.

The surgical experience affects the family unit as a whole. Therefore prepare both the patient and the family for the surgical experience. Understanding of a patient’s and family’s knowledge, expectations, and perceptions allows you to plan teaching and provide individualized emotional support measures.

Each patient fears surgery. Some fears are the result of past hospital experiences, warnings from friends and family, or lack of knowledge. Assess the patient’s understanding of the planned surgery, its implications, and planned postoperative activities. Ask questions such as “Tell me what you think will happen before and after surgery” or “Explain what you know about surgery.” Nurses face ethical dilemmas when patients are misinformed or unaware of the reason for surgery. Confer with the surgeon if the patient has an inaccurate perception or knowledge of the surgical procedure before the patient is sent to the surgical suite. Also determine whether the health care provider explained routine preoperative and postoperative procedures and assess the patient’s readiness and willingness to learn. When a patient is well prepared and knows what to expect, reinforce his or her knowledge.

Medication History: Presence of preexisting co-morbid conditions such as hypertension, renal or heart disease, respiratory disorders, and diabetes increases a patient’s surgical risk. If a patient regularly uses prescription or over-the-counter medications, the surgeon or anesthesia provider may temporarily discontinue the drugs before surgery or adjust the dosages. Certain medications pose greater risks for surgical complications (Table 50-5). Instruct patients to ask the health care provider if they need to take usual medications the morning of surgery. Also ask them if they take any herbal preparations because many patients do not view herbs as medications and often omit them from their medication history (see Chapter 32). Certain herbs interfere with the action of other medications (consult the pharmacist). For hospitalized patients prescription drugs taken before surgery are automatically discontinued after surgery unless the health care provider reorders them. The use of a medication reconciliation process (see Chapter 31) is common practice to ensure that at the time of a patient’s admission a complete list of the medications the patient is taking at home is created and documented. The patient and, as needed, the family needs to be involved to be sure that there is an accurate and current medication list for the patient (TJC, 2011).

TABLE 50-5

Drugs with Special Implications for the Surgical Patient

Allergies: Assess for patients’ allergies to drugs during the perioperative period. Also assess for latex, food, and contact allergies (e.g., to tape, ointments, or solutions). A wide variety of equipment and materials used in the OR contains latex; thus assessment is critical. Patients most at risk for a latex allergy include people with genetic predisposition to latex allergy, children with spina bifida, patients with urogenital abnormalities or spinal cord injury (because of a long history of urinary catheter use), patients with a history of multiple surgeries, health care professionals, and workers who manufacture rubber products. Patients with an allergy to certain foods such as bananas, chestnuts, kiwi fruit, avocadoes, and tomatoes have shown a cross-sensitivity to latex (Sussman and Gold, 2010). Surgical centers provide latex-free environments for patients with known latex allergies.

Some patients are too young or have not had any exposure to drugs; thus they do not know if they have allergies. The type of allergic response is very important to assess. Allergies are not the same as unpleasant side effects. For example, codeine may cause nausea (a side effect) or hypotension and confusion (an allergy). When asking a patient about allergies, realize that the term allergy is confusing for some patients. Asking a patient if he or she has ever “had a problem with a medication or substance” is a helpful approach to questioning. Ensure that you list the patient’s allergies appropriately in his or her chart and/or the hospital computer system and any other places designated by institutional policy such as an allergy band.

Smoking Habits: The patient who smokes is at greater risk for postoperative pulmonary complications than a patient who does not (Smetana, 2009). The chronic smoker already has an increased amount and thickness of mucus secretions in the lungs. General anesthetics increase airway irritation and stimulate pulmonary secretions, which the airways retain as a result of reduction in ciliary activity during anesthesia. After surgery the patient who smokes has greater difficulty clearing the airways of mucus secretions and needs to know the importance of postoperative deep breathing and coughing (see Chapter 40).

Alcohol Ingestion and Substance Use and Abuse: Habitual use of alcohol and illegal drugs predisposes the patient to adverse reactions to anesthetic agents. Some patients experience a cross-tolerance to anesthetic agents, necessitating higher-than-normal doses. In addition, the health care provider may need to increase postoperative dosages of analgesics. Patients with a history of excessive alcohol ingestion are often malnourished, which delays wound healing. These patients are also at risk for liver disease, portal hypertension, and esophageal varices (predisposing the patient to bleeding disorders). The patient who habitually uses alcohol and is required to remain in the hospital longer than 24 hours is also at risk for acute alcohol withdrawal and its more severe form, delirium tremens (DTs).

Support Sources: Because a patient’s family does not always consist of blood relations, always assess who comprises family and their level of support. The patient usually cannot immediately assume the same level of physical activity enjoyed before surgery. With ambulatory surgery patients and families assume responsibility for postoperative care. The family is an important resource for the patient with physical limitations and provides the emotional support needed to motivate him or her to return to a previous state of health. Sometimes a family member remembers preoperative and postoperative teaching better than the patient. With older adults having ambulatory surgery, it is important to establish before surgery that the patient will receive a postdischarge phone call as a check on recovery progress. Because some older adults are unable to hear or reach a phone after surgery, identify if a family member will be staying with the patient to answer the phone. Another option is an arrangement for the family member to call the surgery center the next day to ensure proper follow-up (Mamaril, 2006).

Ask if family members or friends are able to provide support. Some patients want someone else present when you provide instructions or explanations. Encourage family presence when feasible, especially for patients in the ambulatory setting. Often a family member becomes the patient’s coach, offering valuable support during the postoperative period when the patient’s participation in care is vital.

Occupation: Surgery often results in physical changes and limits that prevent a person from returning to work or lengthen recovery time before work can be resumed. Assess the patient’s occupational history to anticipate the possible effects of surgery on recovery, return to work, and eventual work performance. Explain any restrictions such as lifting, use of the extremities, or climbing stairs before a patient returns to work. When a patient is unable to return to a job, refer him or her to a social worker and/or occupational therapist for job-training programs or to help him or her seek economic assistance.

Preoperative Pain Assessment: Surgical manipulation of tissues, treatments, and positioning on the OR table contribute to postoperative pain. Before surgery conduct a comprehensive pain assessment, including the patient’s and family’s expectations for pain management following surgery. Ask patients to describe their perceived tolerance to pain, past experiences, and prior successful interventions used. Teaching patients how to score their pain before surgery allows for more effective self-report of pain after surgery (Bond et al., 2005). Use a pain instrument to rate the presence and severity of pain before surgery (see Chapter 43). Frequent pain assessments are necessary to alert nurses to treat the pain and assess the adequacy (outcome) of pain interventions.

Review of Emotional Health: Surgery is psychologically stressful. Patients are often anxious about the surgery and its implications and believe that they are powerless over their situation. Family members may perceive the patient’s surgery as a disruption of their lifestyle. Hospitalization and the recovery period at home are sometimes lengthy. The family is usually concerned about the patient returning to a normal, productive life. When the patient has chronic illness, the family is either fearful that surgery will result in further disability or hopeful that it will improve their lifestyle. To understand the impact of surgery on a patient’s and family’s emotional health, assess the patient’s feelings about surgery, self-concept, body image, and coping resources.

It is difficult to assess a patient’s feelings thoroughly when ambulatory surgery is scheduled because you have less time to establish a relationship with him or her. You can address these concerns initially with the patient during a home visit or on the telephone before surgery. In a hospital room choose a time for discussion after completing admitting procedures or diagnostic tests. Explain that it is normal to have fears and concerns. For example, patients often have a fear of being “put to sleep” under anesthesia because it causes loss of control. A patient’s ability to share feelings partially depends on your willingness to listen, be supportive, and clarify misconceptions. Assure patients of their right to ask questions and seek information.

Self-Concept: Patients with a positive self-concept are more likely to approach surgical experiences appropriately. Assess self-concept by asking patients to identify personal strengths and weaknesses (see Chapter 33). Patients who are quick to criticize or scorn their own personal characteristics may have little self-regard or may be testing your opinion of their character. Poor self-concept hinders the ability to adapt to the stress of surgery and aggravates feelings of guilt or inadequacy.

Body Image: Surgical removal of any diseased body part often leaves permanent disfigurement, alteration in body function, or concern over mutilation. Loss of certain body functions (e.g., with a colostomy or amputation) may compound a patient’s fears. Assess for body image alterations that patients perceive will result from surgery. Individuals respond differently, depending on their culture, age, experience in seeing others with alterations, and their own self-concept and self-esteem (see Chapter 33).

Often surgery changes the physical or psychological aspects of patients’ sexuality. Excision of breast tissue, an ostomy, hysterectomy, or removal of the prostate gland affects patients’ perceptions of their sexuality. Surgery such as hernia repair or cataract extraction forces patients to temporarily refrain from sexual intercourse until they return to normal physical activity. Encourage patients to express concerns about their sexuality. The patient facing even temporary sexual dysfunction requires understanding and support. Hold discussions about the patient’s sexuality with his or her sexual partner so the partner gains a shared understanding of how to cope with limitations in sexual function (see Chapter 34).

Coping Resources: Assessment of feelings and self-concept reveals whether the patient is able to cope with the stress of surgery. The physiological effects of stress are well documented. Activation of the endocrine system results in the release of hormones and catecholamines, which increases blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration. Platelet aggregation also occurs, along with many other physiological responses. Be aware of these responses and assist with stress management (see Chapter 37).

Ask the patient about past stress management techniques and behaviors that helped resolve any tension or nervousness. When reviewing the patient’s coping resources, ask him or her about specific family members and friends who may provide support. Once identified, include these individuals in any patient teaching and interventions to manage stress and anxiety.

Culture and Religion: Culture is a system of beliefs and values developed over time and passed on through many generations. Patients come from diverse cultural, ethnic, and religious backgrounds, which affect the way each patient perceives and reacts to the surgical experience. An important aspect of patient-centered care is to identify a family’s and patient’s expectations for relief of pain, discomfort, and suffering (Cronenwett et al., 2007). If you do not acknowledge and plan for cultural, ethnic, and religious differences in the perioperative plan of care, you may not achieve desired surgical outcomes (Box 50-2). The acquisition of knowledge about a patient’s cultural and ethnic heritage helps you care for the perioperative patient. Although it is important to recognize and plan for differences based on culture, it is also necessary to recognize that members of the same culture are individuals and do not always hold these shared beliefs.

Physical Examination: Conduct a partial or complete physical examination, depending on the amount of time available and the patient’s preoperative condition. Chapter 30 describes physical assessment techniques. Assessment focuses on findings from the patient’s medical history and on body systems that the surgery is likely to affect. The nursing assessment complements the surgeon’s and anesthesia provider’s physical examination (Bray, 2006).

General Survey: Observe the patient’s general appearance. Gestures and body movements may reflect weakness caused by illness. Assess the patient for a malnourished appearance. Height, body weight, and history of recent weight loss are important indicators of nutritional status.

Preoperative vital signs, including blood pressure while sitting and standing, and pulse oximetry provide important baseline data with which to compare alterations that occur during and after surgery. Some institutions request that you obtain blood pressure in both arms for comparison. Anxiety and fear commonly cause elevations in heart rate and blood pressure. Preoperative assessment of vital signs is also important to rule out fluid and electrolyte abnormalities (see Chapter 41).

An elevated temperature before surgery is a cause for concern. If the patient has an underlying infection, the surgeon may choose to postpone surgery until the infection has been treated. An elevated body temperature increases the risk of fluid and electrolyte imbalance after surgery. Notify the surgeon immediately if the patient has an elevated temperature.

Head and Neck: The condition of oral mucous membranes is one indicator of the level of hydration. Inspect the area between the gums and cheek, the soft palate, and the nasal sinuses. Sinus drainage indicates respiratory or sinus infection. During the examination of the oral mucosa, identify any loose or capped teeth because they can become dislodged during endotracheal intubation. Note the presence of dentures, prosthetic devices, or piercings so they can be removed before surgery, especially if the patient receives general anesthesia.

Integument: Carefully inspect the skin, especially over bony prominences such as the heels, elbows, sacrum, back of head, and scapula. During surgery patients often lie in a fixed position for several hours, making them at increased risk for pressure ulcers (see Chapter 48) (Walton-Geer, 2009). Chronic use of steroids also increases a patient’s susceptibility to skin tears. The overall condition of the skin reveals the patient’s level of hydration. An older adult is at high risk for alteration in skin integrity from positioning (pressure forces) and sliding on the OR table (shearing forces).

Thorax and Lungs: Assessment of the patient’s breathing pattern and chest excursion measures ventilatory capacity. A decline in ventilatory function places the patient at risk for respiratory complications. Auscultation of breath sounds indicates whether the patient has pulmonary congestion or narrowing of airways. Existing atelectasis or moisture in the airways is aggravated during surgery. Serious pulmonary congestion usually results in postponement of the surgery. Certain anesthetics cause laryngeal muscle spasm. If you auscultate wheezing in the airways before surgery, the patient is at risk for further airway narrowing during surgery and after extubation (removal of the endotracheal tube); therefore notify health care providers of these findings.

Heart and Vascular System: Assess the character of the apical pulse and listen to heart sounds. Assess peripheral pulses, capillary refill, and the color and temperature of extremities. If peripheral pulses are not palpable, use a Doppler instrument for assessment of their presence. Acceptable capillary refill occurs in less than 2 seconds. Measurement of capillary refill and assessment of peripheral pulses are particularly important for the patient having vascular surgery or for a patient who has casts or constricting bandages applied to the extremities after surgery (see Chapter 30).

Abdomen: Assess the abdomen for size, shape, symmetry, and presence of distention. Ask how often the patient has regular bowel movements and inquire about the color and consistency of stools. Auscultate bowel sounds.

Neurological Status: Preoperative assessment of neurological status is important for all patients receiving general anesthesia. The baseline neurological status assists with the assessment of ascent from anesthesia. Observe the patient’s level of orientation, alertness, mood, and ease of speech, noting whether he or she answers questions appropriately and is able to recall recent and past events. A patient who will have surgery for neurological disease (e.g., brain tumor or aneurysm) sometimes demonstrates an impaired level of consciousness or altered behavior. If the patient is scheduled for spinal anesthesia, preoperative assessment of gross motor function and strength is important. Spinal anesthesia causes temporary paralysis of the lower extremities (see Chapter 43). Be aware of a patient entering surgery with weakness or impaired mobility of the lower extremities and communicate this to the perioperative team so care providers do not become alarmed when full motor function does not return as the spinal anesthetic wears off.

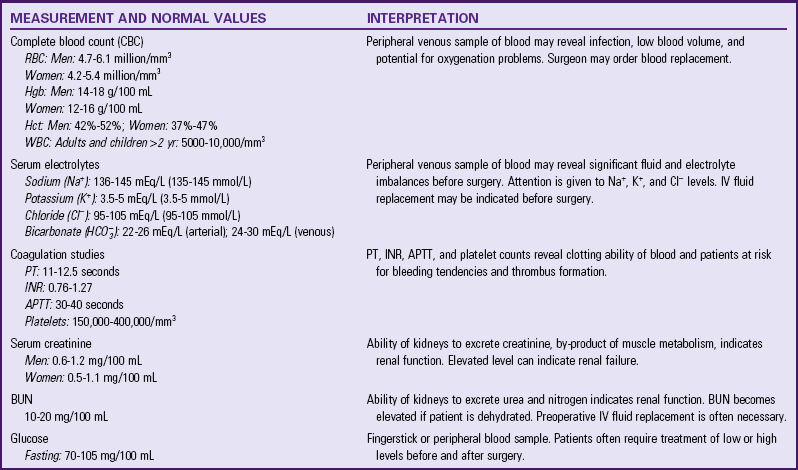

Diagnostic Screening: Patients have a variety of preoperative tests and procedures to confirm or rule out preexisting alterations requiring surgery or that will affect recovery. Usually patients scheduled for ambulatory surgery have tests done several days before surgery. Testing done the day of surgery is usually limited to tests such as glucose monitoring for the patient with diabetes. You need to be familiar with the tests, their purposes, and how to monitor results.

The patient’s medical history, physical assessment findings, and surgical procedure determine the type of tests ordered. For example, a type and cross-match are indicated before surgery for procedures in which blood loss is expected (e.g., hip and knee replacements) in case the patient needs a blood transfusion during surgery. The surgeon designates the number of blood units to have available during surgery. Table 50-6 gives the purpose and normal values for common blood tests. If diagnostic tests reveal severe problems, the surgeon will probably cancel surgery until the cause of the problem is identified or the condition stabilizes. You are responsible for preparing patients for diagnostic studies and coordinating completion of the tests. Review diagnostic results as they become available, alert health care providers to findings, and assist with planning appropriate therapy.

TABLE 50-6

Diagnostic Screening for Surgical Patients

APTT, Activated partial thromboplastin time; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Hct, hematocrit; Hgb, hemoglobin; INR, international normalized ratio; IV, intravenous; PT, prothrombin time; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell.

Modified from Pagana KD, Pagana TJ: Mosby’s diagnostic and laboratory test reference, ed 10, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.

If a patient is over the age of 40 or has heart disease, the health care provider often orders a chest x-ray film examination or an electrocardiogram (ECG). The chest x-ray film is an examination of the condition of the heart and lungs. An ECG measures the electrical activity of the heart to determine whether the heart rate, rhythm, and other factors are normal. Pulmonary function testing and occasionally arterial blood gas analysis are conducted on patients with preexisting lung disease. Blood glucose levels are measured before surgery when patients have diabetes.

Autologous infusions are an option for some patients who choose to donate their own blood before surgery to reduce the risk of transfusion-related infections and transfusion reactions (see Chapter 41). The patient makes the donation several weeks before the scheduled surgery. The patient who self-donates sometimes has a lower hemoglobin and hematocrit level on the day of surgery. Autotransfusion via a cell-saver device during surgery is possible if health care providers are anticipating large blood loss (e.g., open-heart surgery). Although the cell saver is expensive, it returns washed red blood cells to the patient and decreases the risk of transfusion reactions and blood-related infections by using the patient’s own blood (Rothrock, 2007).

Nursing Diagnosis

Cluster patterns of defining characteristics are gathered during the assessment to identify nursing diagnoses for the surgical patient (Box 50-3). The patient with preexisting health problems is likely to have a variety of risk diagnoses. For example, a patient with preexisting bronchitis who has abnormal breath sounds and a productive cough is at risk for ineffective airway clearance. The nature of the surgery and assessment of the patient’s health status provide defining characteristics and risk factors for a number of nursing diagnoses. For example, because a patient will have a surgical incision and an IV infusion, there is a risk for developing infection at the surgical site or in the bloodstream (sepsis). A diagnosis of risk for infection requires your attention from admission through recovery.

The related factors for each diagnosis establish directions for nursing care that is provided during one or all surgical phases. For example, the diagnosis of ineffective airway clearance related to abdominal pain requires different interventions than the diagnosis ineffective airway clearance related to excess mucus. Preoperative nursing diagnoses allow you to take precautions and actions so care provided during the intraoperative and postoperative phases is consistent with the patient’s needs.

Nursing diagnoses made before surgery also focus on the potential risks that a patient may face after surgery. Preventive care is essential so you can manage the surgical patient effectively. The following are some common nursing diagnoses relevant to the patient having surgery:

Planning

During planning synthesize information to establish a plan of care based on the patient’s nursing diagnoses (see the Nursing Care Plan). Apply critical thinking in your selection of nursing interventions (Fig. 50-2). For example, apply knowledge pertaining to adult learning principles, standards for preoperative education (AORN, 2011), and the patient’s unique learning needs to formulate a well-designed preoperative teaching plan for the diagnosis of deficient knowledge. Critical thinking ensures that the patient’s plan of care integrates knowledge, previous experiences, critical thinking attitudes, and established standards of practice. Previous experience in caring for surgical patients helps you anticipate how to approach patient care (e.g., complications to prevent and anticipate and methods to reduce anxiety). Professional standards are especially important to consider when selecting interventions for the plan of care. These standards often establish scientifically proven guidelines for preferred nursing interventions.

Successful planning requires involving the surgical patient and family to set realistic expectations for care. Early involvement of the patient when developing the surgical care plan minimizes surgical risks and postoperative complications. A patient informed about the surgical experience is less likely to be fearful and is able to participate in the postoperative recovery phase so expected outcomes are met. Establish diagnosis, interventions, and outcomes to ensure recovery or maintenance of the preoperative state.

Goals and Outcomes: Base the goals and outcomes of care on the individualized nursing diagnoses. Review and modify the plan during the intraoperative and postoperative periods. Outcomes established for each goal of care provide measurable behavioral evidence to gauge the patient’s progress toward meeting stated goals. As an example, the goal “Patient is able to perform postoperative exercises during postoperative recovery” is measured through the following expected outcomes:

Setting Priorities: Use clinical judgment to prioritize nursing diagnoses and interventions based on the unique needs of each patient. Patients requiring emergent surgery often experience changes in their physiological status that require you to reprioritize quickly. For example, if a patient’s blood pressure begins to drop; hemodynamic stabilization becomes a priority over education and stress management. Ensure that the approach to each patient is thorough and reflects an understanding of the implications of the patient’s age, physical and psychological health, educational level, cultural and religious practices, and stated and/or written wishes concerning advance medical directives.

Teamwork and Collaboration: For patients having ambulatory surgery and those admitted the day of their scheduled surgery, the health care team must collaborate to ensure continuity of care. Preoperative planning ideally occurs days before admission to the hospital or surgical center. The collaboration between the health care provider’s office and the surgical center is crucial to preparing the patient for the procedure. Preoperative instruction gives the patient time to think about the surgical experience, make necessary physical preparations (e.g., altering diet or discontinuing medication use), and ask questions about postoperative procedures. The patient having ambulatory surgery usually returns home on the day of surgery. Thus well-planned preoperative care ensures that he or she is well informed and able to be an active participant during recovery. The family or spouse also plays an active supportive role for the patient.

Implementation

Preoperative nursing interventions provide the patient with a complete understanding of the surgery and anticipated postoperative activities and prepare him or her physically and psychologically for surgical intervention.

Informed Consent: Surgery cannot be legally or ethically performed until a patient understands the need for a procedure, the steps involved, risks, expected results, and alternative treatments. Chapter 23 discusses in detail the nurse’s responsibilities for informed consent. It is the surgeon’s responsibility to explain the procedure and obtain the informed consent. After the patient completes the consent form, place it in the medical record. The record goes to the OR with the patient.

Health Promotion: Health promotion activities during the preoperative phase focus on health maintenance, prevention of complications, and anticipation of continued care needed after surgery.

Preoperative Teaching: Patient education is an important aspect of the patient’s surgical experience (see Chapter 25). Provided in a systematic and structured format with teaching and learning principles, preoperative teaching regarding a patient’s expected postoperative course has a positive influence on the patient’s recovery (Kruzik, 2009). Preadmission nurses call patients up to 1 week before surgery to clarify questions and reinforce explanations. Preoperative information and instructions are delivered by telephone calls, mailings from the health care provider’s office or hospital, printed preoperative teaching guidelines and checklists, or the use of videotapes or websites. The American College of Surgeons developed a patient education website titled Partners in Surgical Care, which provides a supplement to the surgeon’s teaching (American College of Surgeons, 2006). Education throughout the perioperative period is essential. The Joanna Briggs Institute (2000) highlights the importance of preoperative teaching for knowledge acquisition and skill performance. It is ideal to attempt perioperative education before admission, during the hospital stay, and after discharge. Including family members in perioperative preparation is advisable. Often a family member is the coach for postoperative exercises when the patient returns from surgery. The family often has better retention of preoperative teaching and will be with the patient and able to help them in their recovery. If anxious relatives do not understand routine postoperative events, it is likely that their anxiety heightens the patient’s fears and concerns. Perioperative preparation of family members before surgery lessens anxiety and misunderstanding.

Provide patients with information about sensations typically experienced after surgery. Preparatory information helps them anticipate the steps of a procedure and thus form realistic images of the surgical experience. For example, in the OR the anesthesia provider applies ointment to patients’ eyes to prevent corneal damage. Warning patients about sensations of blurred vision reduces their anxiety on awakening from surgery. Other sensations to describe include the expected pain at the surgical site, the tightness of dressings, dryness of the mouth, and the sensation of a sore throat resulting from an endotracheal tube.

Anxiety and fear are barriers to learning, and both emotions heighten as surgery approaches. If the patient is capable of and receptive to learning, present information in a logical sequence, beginning with preoperative events and advancing to intraoperative and postoperative routines. The AORN (2011) has the following standards to demonstrate patient understanding of the surgical experience.

Patient Cites Reasons for Preoperative Instructions and Exercises: When given a rationale for preoperative and postoperative procedures, the patient is better prepared to participate in care. Most preoperative teaching programs include explanation and demonstration of postoperative exercises: diaphragmatic breathing, incentive spirometry, coughing, turning, and leg exercises. These exercises help to prevent postoperative complications (Skill 50-1 on pp. 1287-1292). In addition, if the patient needs graded compression or elastic stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices, teach about the purposes and the specific nursing care associated with the device (see Chapter 47).

After you explain each exercise, demonstrate it for the patient. Guide him or her through each exercise. For example, assess whether the patient is sitting properly and help him or her place the hands in the proper position during breathing. Allow the patient time for independent practice and return later to evaluate effectiveness before surgery.

Patient States Time of Surgery: Tell the patient and family the approximate time that surgery will begin and when they should arrive at the hospital or ASC. The surgeon informs the patient and family of the anticipated length of surgery. Unanticipated delays occur for many reasons. Make the family aware that delays occur for various reasons and do not necessarily indicate a problem.

Patient States Postoperative Unit and Location of Family During Surgery and Recovery: The unit to which the patient is admitted before surgery is often different from the postoperative unit. The family needs to know where the patient will be after surgery. Also explain where the family can wait and where the surgeon will attempt to find family members after surgery. Many institutions have implemented programs in which the circulating nurse gives periodic reports to the family in the waiting room for surgeries that are expected to be prolonged. If the patient will be taken to a special unit, it helps to orient the patient and family members to the environment of the unit before surgery.

Patient Discusses Anticipated Postoperative Monitoring and Therapies: The patient and family need to know about postoperative events. If they understand the frequency of postoperative vital sign monitoring before surgery occurs, they are less apprehensive when nurses measure vital signs. Also explain whether the patient is likely to have IV lines, monitoring lines, dressings, or drainage tubes or will require ventilator support.

Patient Describes Surgical Procedures and Postoperative Treatment: After the surgeon explains the basic purpose of a surgical procedure, some patients ask you additional questions to clarify information. First clarify with the patient what was discussed with the surgeon. When the patient has little or no understanding about the surgery, notify the surgeon that the patient requires further explanation. You can augment the surgeon’s explanations.

Patient Describes Postoperative Activity Resumption: The type of surgery that patients undergo determines how quickly they can resume normal physical activity and regular eating habits. Explain that it is normal to progress gradually in activity and eating. If the patient tolerates activity and diet well, activity levels progress more quickly.

Patient Verbalizes Pain-Relief Measures: Pain is one of the surgical patient’s most common fears. The family is also concerned for the patient’s comfort. Pain after surgery is expected. Inform the patient and family of interventions available for pain relief (e.g., analgesics, positioning, splinting, and relaxation exercises) (see Chapter 43). The patient needs to know the schedule for analgesic drugs, the route of administration, and their effects.

Some patients avoid taking pain-relief drugs after surgery for fear of becoming dependent on them. Encourage the patient to use analgesics as ordered because, unless the pain is controlled, it is difficult for the patient to participate in postoperative therapy. Encourage the patient to take pain medications at the ordered intervals. Pain relief has been shown to be more effective when analgesics are given around-the-clock (ATC) rather than as needed (prn) (Paice et al., 2005), especially if pain is expected throughout the day. However, prn administration of analgesics after surgery is still very common. Closely assess the patient’s pain level, tolerance to activity, and response to pain-relieving interventions. When pain is not regularly addressed, it becomes excruciating, and an analgesic often does not provide relief at the dose ordered. Teach patients who will have patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) how to push the button, the need to push the button when beginning to feel discomfort, and that use of the PCA does not cause overmedication (see Chapter 43). Also explain to the patient the length of time that it takes for the drug to begin working. Information from preoperative pain assessment is helpful when teaching about pain-relief measures (such as positioning and splinting).

Patient Expresses Feelings Regarding Surgery: Some patients feel like part of an assembly line before surgery. Frequent visits by staff, diagnostic testing, and physical preparation for surgery consume time; and the patient has few opportunities to reflect on the experience. Recognize the patient as a unique individual. The patient and family need time to express feelings about surgery and ask questions. The patient’s level of anxiety influences the frequency of discussions. While delivering routine care, encourage expression of concerns, be patient and listen attentively. The family may wish to discuss concerns without the patient present so their fears do not frighten the patient and vice versa. Establishing a trusting and therapeutic relationship with the patient and family allows this to happen.

Acute Care: Acute care activities in the preoperative phase focus on the physical preparation of the patient for surgery.

Physical Preparation: The degree of preoperative physical preparation depends on the patient’s health status, the planned surgery, and the surgeon’s preferences. A seriously ill patient receives more supportive care in the form of medications, IV fluid therapy, and monitoring than the patient facing a minor elective procedure.

Maintaining Normal Fluid and Electrolyte Balance: The surgical patient is vulnerable to fluid and electrolyte imbalances as a result of the stress of surgery, inadequate preoperative intake, and the potential for excessive fluid losses during surgery (see Chapter 41). The American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Preoperative Fasting (ASA, 2011) reviewed the current fasting practices for elective procedures requiring general anesthesia, regional anesthesia, or sedation. They recommend fasting before nonemergent procedures for the following time periods: do not take clear liquids for 2 hours; do not take breast milk for 4 hours; and do not take formula, solids, and nonhuman milk for 6 hours. For fatty, fried, and meat sources the recommended fast is for 8 hours. A patient who is at home the evening before surgery needs to understand the importance of the specific fasting period ordered by the health care provider.

Agencies vary regarding these fasting guidelines. One difficulty is that often surgical cases begin before the time they are originally scheduled. When a patient is admitted NPO, remove fluids and solid foods from the patient’s bedside and post a sign over the bed to alert hospital personnel and family members about fasting restrictions. Some patients take specific medications (e.g., anticoagulants, cardiovascular medications, anticonvulsants, and antibiotics) with a sip of water as ordered by their health care providers. Although the concept of preoperative fasting has changed over the past 10 years, studies and a systematic review demonstrate that the guidelines are not fully implemented and multidisciplinary improvement processes are necessary (Brady, Kinn, and Stuart, 2003).

Allow patients time to rinse their mouths with water or mouthwash and brush their teeth immediately before surgery as long as they do not swallow water. Notify the surgeon and anesthesia provider if the patient eats or drinks during the fasting period.

During surgery normal mechanisms for controlling fluid and electrolyte balance, including respiration, digestion, circulation, and elimination, are disturbed. Extensive losses of blood and other body fluids sometimes occur. The surgical stress response aggravates any fluid and electrolyte imbalance. Before the day of surgery patients are usually encouraged to eat foods high in protein with sufficient carbohydrates, fat, and vitamins. If a patient cannot eat because of GI alterations or impairments in consciousness, you will probably start an IV route for fluid replacement. The health care provider assesses serum electrolyte levels to determine the type of IV fluids and electrolyte additives to administer during surgery. Patients with severe nutritional imbalances sometimes require supplements with concentrated protein and glucose such as total parenteral nutrition (see Chapter 44).

Reducing Risk of Surgical Site Infection: A surgical site infection is one of the National Quality Forum (NQF)–endorsed patient safety measures that hospitals are encouraged to report (NQF, 2010). As of 2008 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2010) no longer pays a higher reimbursement for hospitalizations complicated by certain types of surgical wound infections (e.g., mediastinitis after heart surgery, select orthopedic procedures, and certain bariatric procedures for obesity) if they were not present on admission. Thus there is great emphasis within hospitals for preventing the occurrence of surgical site infections.

The risk of developing a surgical site infection is determined by the amount and type of microorganisms contaminating a wound, susceptibility of the host, and the condition of the surgical wound itself. All three factors interact to cause infection. Antibiotics may be ordered in the preoperative period. A reduction in wound infection rates occurs when an antibiotic is administered 30 to 60 minutes before the surgical incision (Weber et al., 2008). The surgeon orders a specific time before surgery for the oral antibiotic to be taken or an IV antibiotic to be administered.

The skin is a favorite site for microorganisms to grow and multiply. Without proper skin preparation, the risk of postoperative wound infection is high. Many surgeons have patients bathe or shower the evening before surgery. Some health care providers ask patients to bathe or shower more than once, whereas others may have patients use an antibacterial soap to clean the proposed operative site. Depending on the surgical procedure, some patients shower the morning of surgery. If the surgical procedure involves the head, neck, or upper chest area, the patient may also be required to shampoo the hair. Cleaning and trimming fingernails and toenails is sometimes necessary.

The need for hair removal depends on the amount of hair, location of the incision, and surgical procedure planned (AORN, 2011). Hair removal can damage and cause breaks in the patient’s skin, which allows for the entry of microorganisms. If required, perform hair removal, preferably with a clipper or shaver, as close to the time of surgery as possible. Short hospital stays reduce the chance of a health care–associated infection (HAI). Patients can also acquire respiratory, urinary tract, and wound infections during hospitalization. One advantage to having ambulatory surgical procedures is that the patient usually returns home after surgery.

Preventing Bowel and Bladder Incontinence: Some patients receive a bowel preparation (e.g., a cathartic or enema) if the surgery involves the lower GI system or lower abdominal organs. Manipulation of portions of the GI tract during surgery results in absence of peristalsis for 24 hours and sometimes longer. Enemas and cathartics such as polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution (GoLytely) clean the GI tract to prevent intraoperative incontinence and postoperative constipation. An empty bowel reduces risk of injury to the intestines and minimizes contamination of the operative wound if a portion of the bowel is incised or opened accidentally or if colon surgery is planned. The surgeon’s order reads “give enemas until clear.” This means that you administer enemas until the enema return contains no solid fecal material (see Chapter 46). Too many enemas given over a short time can cause serious fluid and electrolyte imbalances (Chapter 41). Most agencies limit the number of enemas (usually three) that a nurse may administer successively. Verify a patient’s potassium level following bowel preparation.

Promoting Rest and Comfort: Rest is essential for normal healing. Anxiety about the impending surgery can easily interfere with a patient’s ability to relax or sleep. The underlying condition requiring surgery is often painful, further impairing rest. Attempt to make the patient’s environment quiet and comfortable. The health care provider may order a sedative-hypnotic or anxiolytic agent for the night before surgery. Sedative-hypnotics (e.g., temazepam [Restoril]) affect and promote sleep. Anxiolytic agents (e.g., alprazolam [Xanax]) act on the cerebral cortex and limbic system to relieve anxiety.

Preparation on the Day of Surgery: Complete several routine procedures before releasing patients for surgery.

Hygiene: Basic hygiene measures provide additional comfort before surgery. If the hospitalized patient is unwilling to take a complete bath, a partial bath is refreshing and removes irritating secretions or drainage from the skin. Because the patient cannot wear personal nightwear to the OR because it is restrictive and is a flammable hazard, provide a clean hospital gown. When the patient is NPO for the last several hours, his or her mouth is often very dry. Offer the patient mouthwash and toothpaste, again cautioning the patient not to swallow water.

Hair and Cosmetics: During surgery with the patient under general anesthesia, his or her head is positioned to introduce an endotracheal tube into the airway (see Chapter 40). This procedure may involve manipulation of the patient’s hair and scalp. To avoid injury ask the patient to remove hairpins or clips before leaving for surgery. Electrocautery is frequently used during surgery. Hairpins and clips can become an exit source for the electricity and cause burns. Remove hairpieces or wigs as well. The patient applies a disposable hat before entering the OR.

During and after surgery the anesthesia provider and nurse assess skin and mucous membranes to determine the patient’s level of oxygenation and circulation. Therefore remove all makeup (i.e., lipstick, powder, blush, nail polish) to expose normal skin and nail coloring. Pulse oximetry records accurate measurements through most nail polish colors, but removal is still considered good practice. Also remove contact lenses, false eyelashes, and eye makeup. Give the patient’s glasses to the family immediately before the patient leaves for the OR. Document this per agency policy.

Removal of Prostheses: It is easy for any type of prosthetic device to become lost or damaged during surgery. The patient needs to remove all prostheses, including partial or complete dentures, artificial limbs, artificial eyes, and hearing aids. If a patient has a brace or splint, check with the health care provider to determine whether it should remain with him or her.

For many patients it is embarrassing to remove dentures, wigs, or other devices that enhance personal appearance. Always offer privacy as the patient removes personal items. Patients are sometimes allowed to keep these until they reach the preoperative area. Place dentures in special containers, labeled with the patient’s name and other identification required by the agency, for safekeeping to prevent loss or breakage. In many agencies you document an inventory of all prosthetic devices or personal items and have them locked away. It is also common practice for nurses to give prostheses to family members or to keep the devices at the patient’s bedside. Document these actions in the nursing notes, surgical checklist, or per agency policy.