Planning Nursing Care

• Explain the relationship of planning to assessment and nursing diagnosis.

• Discuss criteria used in priority setting.

• Discuss the difference between a goal and an expected outcome.

• List the seven guidelines for writing an outcome statement.

• Develop a plan of care from a nursing assessment.

• Discuss the differences between nurse-initiated, physician-initiated, and collaborative interventions.

• Discuss the process of selecting nursing interventions during planning.

• Describe the role that communication plays in planning patient-centered care.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

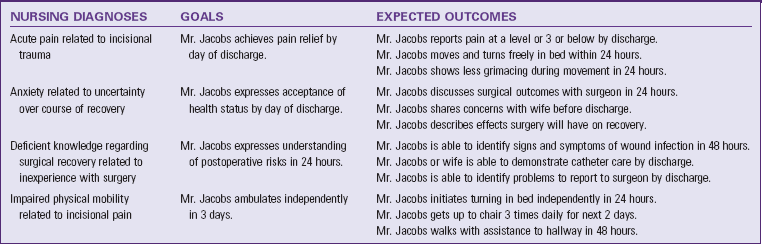

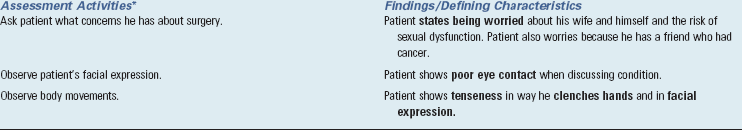

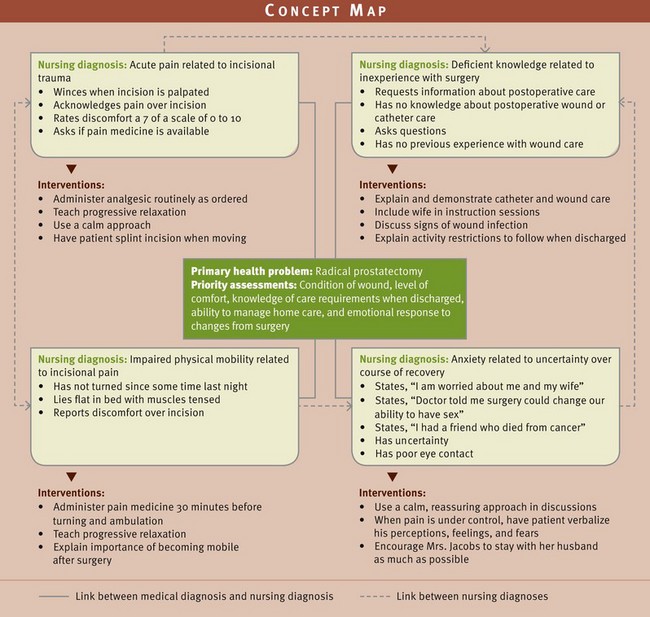

Tonya conducted a thorough assessment of Mr. Jacobs’ health status and identified four nursing diagnoses: acute pain related to incisional trauma, deficient knowledge regarding postoperative recovery related to inexperience with surgery, impaired physical mobility related to incisional pain, and anxiety related to uncertainty over course of recovery. Tonya is responsible for planning Mr. Jacobs’ nursing care from the time of her initial assessment in the morning until the end of her shift. The care that she plans will continue throughout the course of Mr. Jacobs’ hospital stay by the other nurses involved in Mr. Jacobs’ care. If Tonya plans well, the individualized interventions that she selects will prepare the patient for a smooth transition home. Collaboration with the patient is critical for a plan of care to be successful. Using input from Mr. Jacobs, Tonya identifies the goals and expected outcomes for each of his nursing diagnoses. The goals and outcomes direct Tonya in selecting appropriate therapeutic interventions. Tonya knows that Mrs. Jacobs’ must be involved in the patient’s care because of the ongoing support that she provides and because she will be a key care provider once Mr. Jacobs’ returns home. In addition, Mr. Jacobs has told Tonya that his wife is the one who keeps their family together. Consultation with other health care providers such as social work or home health ensures that the right resources are used in planning care. Careful planning involves seeing the relationships among a patient’s problems, recognizing that certain problems take precedence over others, and proceeding with a safe and efficient approach to care.

After you identify a patient’s nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems, you begin planning, the third step of the nursing process. Planning involves setting priorities, identifying patient-centered goals and expected outcomes, and prescribing individualized nursing interventions. Ultimately during implementation your interventions resolve the patient’s problems and achieve the expected goals and outcomes (see Chapter 19). Planning requires critical thinking applied through deliberate decision making and problem solving. It also involves working closely with patients, their families, and the health care team through communication and ongoing consultation. Patients benefit most when their care represents a collaborative effort from the expertise of all health care team members. A plan of care is dynamic and changes as the patient’s needs change.

Establishing Priorities

Remember that a single patient often has multiple nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems. In addition, once you enter into nursing practice, you do not care for just a single patient. Eventually you care for groups of patients. Being able to carefully and wisely set priorities for a single patient or group of patients ensures the timeliest, relevant, and appropriate care.

Priority setting is the ordering of nursing diagnoses or patient problems using determinations of urgency and/or importance to establish a preferential order for nursing actions (Hendry and Walker, 2004). In other words, as you care for a patient or a group of patients, you must deal with certain aspects of care before others. By ranking a patient’s nursing diagnoses in order of importance, you attend to each patient’s most important needs and better organize ongoing care activities. Priorities help you to anticipate and sequence nursing interventions when a patient has multiple nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems. Together with your patients, you select mutually agreed-on priorities based on the urgency of the problems, the patient’s safety and desires, the nature of the treatment indicated, and the relationship among the diagnoses. Establishing priorities is not a matter of numbering the nursing diagnoses on the basis of severity or physiological importance. Nurses establish priorities in relation to clinical importance, but they also prioritize on the basis of time. On a given day the demands that exist within a health care setting require you to ration your time wisely.

Classify a patient’s priorities as high, intermediate, or low importance. Nursing diagnoses that, if untreated, result in harm to a patient or others (e.g., those related to airway status, circulation, safety, and pain) have the highest priorities. One way to consider diagnoses of high priority is to consider Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (see Chapter 6). For example, risk for other-directed violence, impaired gas exchange, and decreased cardiac output are examples of high-priority nursing diagnoses that drive the priorities of safety, adequate oxygenation, and adequate circulation. However, it is always important to consider each patient’s unique situation. High priorities are sometimes both physiological and psychological and may address other basic human needs. Avoid classifying only physiological nursing diagnoses as high priority. Consider Mr. Jacobs’ case. Among his nursing diagnoses, acute pain and anxiety are of the highest priority. Tonya knows that she needs to relieve Mr. Jacobs’ acute pain and lessen his anxiety so he will be responsive to discharge education and be able to participate in postoperative care activities.

Intermediate priority nursing diagnoses involve nonemergent, nonlife-threatening needs of patients. In Mr. Jacobs’ case, deficient knowledge and impaired physical mobility are both intermediate diagnoses. It is important for Mr. and Mrs. Jacobs’ to understand potential problems that develop following surgery, know how to recognize the problems, and be able to continue appropriate care at home. Focused and individualized instruction from all members of the health care team is necessary throughout a patient’s hospitalization. The diagnosis of impaired physical mobility is not life threatening and will likely resolve once Tonya and the other nurses collaborate with the surgeon to ensure effective pain control. Relief of pain will make Mr. Jacobs’ more mobile and more active in his road to recovery.

Low-priority nursing diagnoses are not always directly related to a specific illness or prognosis but affect the patient’s future well-being. Many low-priority diagnoses focus on the patient’s long-term health care needs. Tonya has not yet identified a nursing diagnosis related to Mr. Jacobs’ concern about his sexual function. At this point the patient’s anxiety over the uncertainty of the success of surgery, the risk of cancer recurrence, and his concern about his sexual function are the predominant problems. If the patient learns from the surgeon that the procedure resulted in damage to the nerves affecting his sexual performance, a diagnosis more pertinent to this health problem is appropriate.

The order of priorities changes as a patient’s condition changes, sometimes within a matter of minutes. Each time you begin a sequence of care such as at the beginning of a hospital shift or a patient’s clinic visit, it is important to reorder priorities. For example, when Tonya first met Mr. Jacobs, his acute pain was rated at a 7, and it was apparent that the administration of an analgesic was more a priority than trying to reposition or use other nonpharmacological approaches (e.g., relaxation or distraction). Later, after receiving the analgesic, Mr. Jacobs’ pain lessened to a level of 4; and Tonya was able to gather more assessment information and begin to focus on his problem of deficient knowledge. Ongoing patient assessment is critical to determine the status of your patient’s nursing diagnoses. The appropriate ordering of priorities ensures that you meet a patient’s needs in a timely and effective way.

Priority setting begins at a holistic level when you identify and prioritize a patient’s main diagnoses or problems (Hendry and Walker, 2004). However, you also need to prioritize the specific interventions or strategies that you will use to help a patient achieve desired goals and outcomes. For example, as Tonya considers the high-priority diagnosis of acute pain for Mr. Jacobs, she decides during each encounter which intervention to do first among these options: administering an analgesic, repositioning, and teaching relaxation exercises. Critical thinking helps her to prioritize. Tonya knows that a certain degree of pain relief is necessary before a patient can participate in relaxation exercises. When she is in the patient’s room, she might decide to turn and reposition Mr. Jacobs first and then prepare the analgesic. However, if Mr. Jacobs expresses that pain is a high level and is too uncomfortable to turn, Tonya chooses obtaining and administering the analgesic as her first priority. Later, with Mr. Jacobs’ pain more under control, she considers whether relaxation is appropriate.

Involve patients in priority setting whenever possible. Patient-centered care requires you to know a patient’s preferences, values, and expressed needs. Tonya must learn what Mr. Jacobs expects with regard to pain control to have a relevant plan of care in place. In some situations a patient assigns priorities different from those you select. Resolve any conflicting values concerning health care needs and treatments with open communication, informing the patient of all options and consequences. Consulting with and knowing the patient’s concerns do not relieve you of the responsibility to act in a patient’s best interests. Always assign priorities on the basis of good nursing judgment.

Ethical care is a part of priority setting. When ethical issues make priorities less clear, it is important to have open dialogue with the patient, the family, and other health care providers (Holmstrom and Hoglund, 2007). For example, when you care for a patient nearing death or one newly diagnosed with a chronic long-term disabling disease, you need to be able to discuss the situation fully with the patient, know his or her expectations, know your own professional responsibility in protecting the patient from harm, know the physician’s therapeutic or palliative goals, and then form a plan of care. Chapter 22 outlines strategies for choosing a course of action when facing an ethical dilemma.

Priorities in Practice

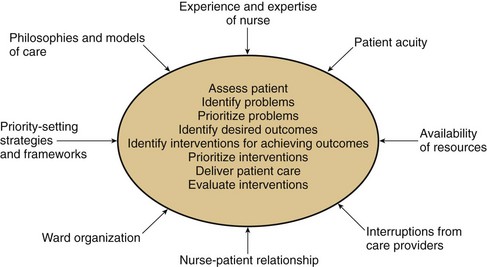

Hendry and Walker (2004) address an important issue regarding priority setting (Fig. 18-1). Many factors within the health care environment affect your ability to set priorities. For example, in the hospital setting the model for delivering care (see Chapter 21), the organization of a nursing unit, staffing levels, and interruptions from other care providers affect the minute-by-minute determination of patient care priorities. Available resources (e.g., nurse specialists, laboratory technicians, and dietitians), policies and procedures, and supply access affect priorities as well. Finally, patients’ conditions are always changing; thus priority setting is always changing.

FIG. 18-1 A model for priority setting. (Modified from Hendry C, Walker A: Priority setting in clinical nursing practice, J Adv Nurs 47[4]:427, 2004.)

The same factors that influence your minute-by-minute ability to prioritize nursing actions affect the ability to prioritize nursing diagnoses for groups of patients. The nature of nursing work challenges your ability to cognitively attend to a given patient’s priorities when you care for more than one patient. The nursing care process is nonlinear (Potter et al., 2005). Often you complete an assessment and identify nursing diagnoses for one patient, leave the room to perform an intervention for a second patient, and move on to consult on a third patient. Nurses exercise “cognitive shifts” (i.e., shifts in attention from one patient to another during the conduct of the nursing process). This shifting of attention occurs in response to changing patient needs, new procedures being ordered, or environmental processes interacting (Potter et al., 2005). Because of these cognitive shifts, it becomes important to stay organized and know your patients’ priorities. Always work from your plan of care and use your patients’ priorities to organize the order for delivering interventions and organizing documentation of care.

Critical Thinking in Setting Goals and Expected Outcomes

Once you identify nursing diagnoses for a patient, ask yourself, “What is the best approach to address and resolve each problem? What do I plan to achieve?” Goals and expected outcomes are specific statements of patient behavior or physiological responses that you set to resolve a nursing diagnosis or collaborative problem. For example, Tonya chooses to administer ordered analgesics for Mr. Jacobs’ acute pain and provide nursing measures that promote relaxation and minimize any other sources of discomfort. She hopes to achieve pain relief (goal). The specific patient behaviors or physiological responses (expected outcomes) include Mr. Jacobs’ reporting pain at a level below 4, showing more freedom in movement and less grimacing, and being able to participate in education sessions.

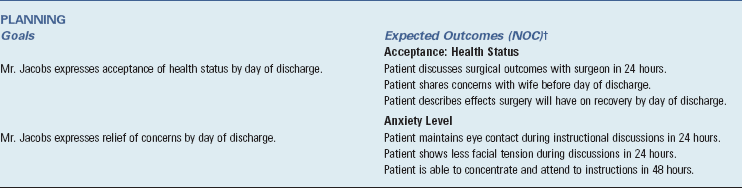

During planning you select goals and outcomes for each nursing diagnosis to provide a clear focus for the type of interventions needed to care for your patient and to then evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions. A goal is a broad statement that describes a desired change in a patient’s condition or behavior. Mr. Jacobs has the diagnosis of deficient knowledge regarding his postoperative recovery. A goal of care for this diagnosis includes, “Patient expresses understanding of postoperative risks.” The goal requires making Mr. Jacobs aware of the risks associated with his type of surgery. It gives Tonya a clear focus on the topics to include in her instruction. An expected outcome is a measurable criterion to evaluate goal achievement. Once an outcome is met, you then know that a goal has been at least partially achieved. Sometimes several expected outcomes must be met for a single goal. Measurable outcomes for the goal of “understanding postoperative risks” include: “Patient identifies signs and symptoms of wound infection,” and “Patient explains signs of urinary obstruction,” both risks from a prostatectomy. After Tonya instructs Mr. Jacobs, she determines if he can identify signs and symptoms of wound infection; if so, the goal is partially met. If the patient can also explain signs of urinary obstruction, the goal is fully met.

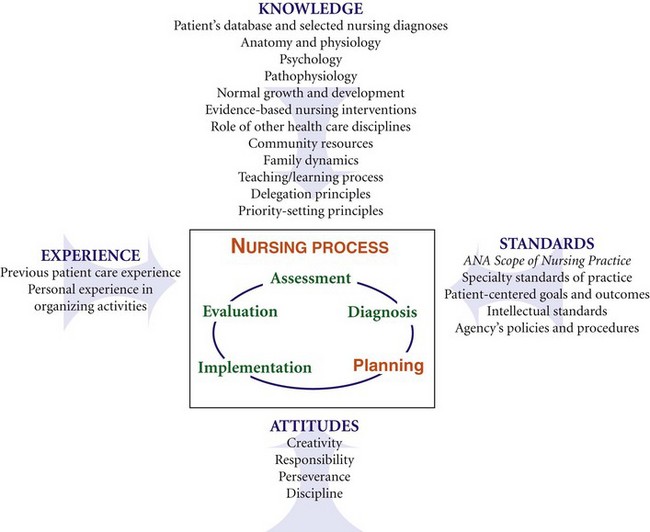

Planning nursing care requires critical thinking (Fig. 18-2). Critically evaluate the identified nursing diagnoses, the urgency or priority of the problems, and the resources of the patient and the health care delivery system. You apply knowledge from the medical, sociobehavioral, and nursing sciences to plan patient care. The selection of goals, expected outcomes, and interventions requires consideration of your previous experience with similar patient problems and any established standards for clinical problem management. The goals and outcomes need to meet established intellectual standards by being relevant to patient needs, specific, singular, observable, measurable, and time limited. You also use critical thinking attitudes in selecting interventions with the greatest likelihood of success.

Goals of Care

A patient-centered goal reflects a patient’s highest possible level of wellness and independence in function. It is realistic and based on patient needs and resources. For example, consider the diagnoses of acute pain versus chronic pain. A patient such as Mr. Jacobs with acute pain can realistically expect pain relief. In contrast, a patient with terminal bone cancer in chronic pain can only expect an acceptable level of pain control. A patient goal represents a predicted resolution of a diagnosis or problem, evidence of progress toward resolution, progress toward improved health status, or continued maintenance of good health or function (Carpenito-Moyet, 2009).

Each goal is time limited so the health care team has a common time frame for problem resolution. For example, the goal of “patient will achieve pain relief” for Mr. Jacobs is complete by adding the time frame “by day of discharge.” With this goal in place, all efforts by the health care team are aimed at managing the patient’s pain. At the time of discharge evaluation of expected outcomes (e.g., pain-rating score, signs of grimacing, level of movement) show if the goal was met. The time frame depends on the nature of the problem, etiology, overall condition of the patient, and treatment setting. A short-term goal is an objective behavior or response that you expect a patient to achieve in a short time, usually less than a week. In an acute care setting you often set goals for over a course of just a few hours. A long-term goal is an objective behavior or response that you expect a patient to achieve over a longer period, usually over several days, weeks, or months (e.g., “Patient will be tobacco free within 60 days”). Table 18-1 shows the progression from nursing diagnoses to goals and expected outcomes and the relationship to nursing interventions.

Role of the Patient in Goal Setting

Always partner with patients when setting their individualized goals. Mutual goal setting includes the patient and family (when appropriate) in prioritizing the goals of care and developing a plan of action. For patients to participate in goal setting, they need to be alert and have some degree of independence in completing activities of daily living, problem solving, and decision making. Unless goals are mutually set and there is a clear plan of action, patients fail to fully participate in the plan of care. Patients need to understand and see the value of nursing therapies, even though they are often totally dependent on you as the nurse. When setting goals, act as an advocate or support for the patient to select nursing interventions that promote his or her return to health or prevent further deterioration when possible.

Tonya has a discussion with Mr. Jacobs and his wife together about setting the plan for the diagnosis of deficient knowledge. Tonya explains the topics that they need to discuss so the couple understands Mr. Jacobs’ postoperative risks. They plan the instruction the next day just before lunch when Mrs. Jacobs’ visits. Mr. Jacobs asks to have the instruction also include information on how the surgery can affect his sexual function. Tonya agrees and plans to clarify with the surgeon so the information is accurate and realistic. The surgeon has told Mr. Jacobs that there is a risk, but it is too early to know the extent of any possible nerve damage.

Expected Outcomes

An expected outcome is a specific measurable change in a patient’s status that you expect to occur in response to nursing care. Outcomes as a result of Mr. Jacobs’ postoperative instruction include his ability to describe signs of a surgical wound infection and identify when to call his surgeon with problems. Expected outcomes direct nursing care because they are the desired physiological, psychological, social, developmental, or spiritual responses that indicate resolution of a patient’s health problems. A patient’s willingness and capability to reach an expected outcome improves his or her likelihood of achieving it. Taken from both short- and long-term goals, outcomes determine when a specific patient-centered goal has been met.

Usually you develop several expected outcomes for each nursing diagnosis and goal because sometimes one nursing action is not enough to resolve a patient problem. In addition, a list of the step-by-step expected outcomes gives you practical guidance in planning interventions. Always write expected outcomes sequentially, with time frames (see Table 18-1). Time frames give you progressive steps in which to move a patient toward recovery and offer an order for nursing interventions. They also set limits for problem resolution.

Nursing Outcomes Classification

Much attention in the current health care environment is focused on measuring outcomes to gauge the quality of health care. If a chosen intervention repeatedly results in desired outcomes that benefit patients, it needs to become part of a standardized approach to a patient problem. For example, if the use of a chlorhexidine mouthwash (intervention) repeatedly results in a lower incidence of aspiration pneumonia (outcome) in critically ill patients, use of the mouthwash needs to become part of standard mouth care in critical care units.

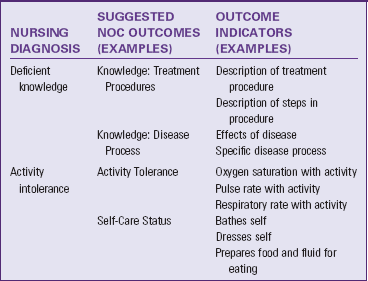

Nursing plays an important role in monitoring and managing patient conditions and diagnosing problems that are amenable to nursing intervention. The clinical reasoning and decision making of nurses is a key part of quality health care (Moorhead et al., 2008). Thus it becomes important to identify and measure patient outcomes that are influenced by nursing care. A nursing-sensitive patient outcome is a measurable patient, family or community state, behavior, or perception largely influenced by and sensitive to nursing interventions (Moorhead et al., 2008). For the nursing profession to become a full participant in clinical evaluation research, policy development, and interdisciplinary work, nurses need to identify and measure patient outcomes influenced by nursing interventions. The Iowa Intervention Project has done just that. It published the Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) and linked the outcomes to NANDA International nursing diagnoses (Moorhead et al., 2008). For each NANDA International nursing diagnosis there are multiple NOC suggested outcomes. These outcomes have labels for describing the focus of nursing care and include indicators to use in evaluating the success with nursing interventions (Table 18-2). NOC contains outcomes for individuals, family caregivers, the family, and the community in all health care settings. Efforts to measure outcomes and capture the changes in the status of patients over time allow nurses to improve patient care quality and add to nursing knowledge (Moorhead et al., 2008). The use of a common set of outcomes allows nurses to study the effects of nursing interventions over time and across settings. The fourth edition of NOC standardizes the way to measure patient outcomes. It is an excellent resource for you to develop care plans and concept maps. NOC outcomes provide a common nursing language for continuity of care and measurement of the success of nursing interventions.

Guidelines for Writing Goals and Expected Outcomes

There are seven guidelines for writing goals and expected outcomes.

Patient-Centered

Outcomes and goals reflect patient behaviors and responses expected as a result of nursing interventions. Write a goal or outcome to reflect a patient’s specific behavior, not to reflect your goals or interventions.

Singular Goal or Outcome

You want to be precise when you evaluate a patient’s response to a nursing action. Each goal and outcome should address only one behavior or response. If an outcome reads, “Patient’s lungs will be clear to auscultation, and respiratory rate will be 20 breaths per minute by 8/22,” your measurement of outcomes will be complicated. When you evaluate that the lungs are clear but the respiratory rate is 28 breaths per minute, you do not know if the patient achieved the expected outcome. By splitting the statement into two parts, “Lungs will be clear to auscultation by 8/22,” and “Respiratory rate will be 20 breaths per minute by 8/22,” you are able to determine if and when the patient achieves each outcome. Singularity allows you to decide if there is a need to modify the plan of care.

A goal also contains only one behavior or response. The example, “Patient will administer a self-injection and demonstrate infection control measures,” is incorrect because the statement includes two different behaviors, administer and demonstrate. Instead word the goal as follows, “Patient will administer a self-injection by discharge.” The specific criteria you use to measure success of the goal are the singular expected outcomes. For example, “Patient will prepare medication dose correctly,” and “Patient uses medical asepsis when preparing injection site.”

Observable

You need to be able to observe if change takes place in a patient’s status. Observable changes occur in physiological findings and in the patient’s knowledge, perceptions, and behavior. You observe outcomes by directly asking patients about their condition or using assessment skills. For example, you observe the goal, “Patient will be able to self-administer insulin,” through the outcome of watching, “Patient prepares insulin dosage correctly by 8/30.” For the outcome, “Lungs will be clear on auscultation by 8/31,” you auscultate the lungs following any therapy. The outcome statement, “Patient will appear less anxious,” is not correct because there is no specific behavior observable for “will appear.” A more correct outcome is, “Patient will show better eye contact during conversations.”

Measurable

You learn to write goals and expected outcomes that set standards against which to measure the patient’s response to nursing care. Examples such as, “Body temperature will remain 98.6° F,” and, “Apical pulse will remain between 60 and 100 beats per minute,” allow you to objectively measure changes in the patient’s status. Do not use vague qualifiers such as “normal,” “acceptable,” or “stable” in an expected outcome statement. Vague terms result in guesswork in determining a patient’s response to care. Terms describing quality, quantity, frequency, length, or weight allow you to evaluate outcomes precisely.

Time-Limited

The time frame for each goal and expected outcome indicates when you expect the response to occur. It is very important to collaborate with patients to set realistic and reasonable time frames. Time frames help you and the patient to determine if the patient is making progress at a reasonable rate. If not, you must revise the plan of care. Time frames also promote accountability in delivering and managing nursing care.

Mutual Factors

Mutually set goals and expected outcomes ensure that the patient and nurse agree on the direction and time limits of care. Mutual goal setting increases the patient’s motivation and cooperation. As a patient advocate, apply standards of practice, evidence-based knowledge, safety principles, and basic human needs when assisting patients with setting goals. Your knowledge background helps you select goals and outcomes that should be met on the basis of typical responses to clinical interventions. Yet you must consider patients’ desires to recover and their physical and psychological condition to set goals and outcomes to which they can agree.

Realistic

Set goals and expected outcomes that a patient is able to reach based on your assessment. This is a challenge when the time allotted for care is limited. But it also means that you must communicate these goals and outcomes to caregivers in other settings who will assume responsibility for patient care (e.g., home health, rehabilitation). Realistic goals provide patients a sense of hope that increases motivation and cooperation. To establish realistic goals, assess the resources of the patient, health care facility, and family. Be aware of the patient’s physiological, emotional, cognitive, and sociocultural potential and the economic cost and resources available to reach expected outcomes in a timely manner.

Critical Thinking in Planning Nursing Care

Part of the planning process is to select nursing interventions for meeting the patient’s goals and outcomes. Once nursing diagnoses have been identified and goals and outcomes are selected, you choose interventions individualized for the patient’s situation. Nursing interventions are treatments or actions based on clinical judgment and knowledge that nurses perform to meet patient outcomes (Bulechek et al., 2008). During planning you select interventions designed to help a patient move from the present level of health to the level described in the goal and measured by the expected outcomes. The actual implementation of these interventions occurs during the implementation phase of the nursing process (see Chapter 19).

Choosing suitable nursing interventions involves critical thinking and your ability to be competent in three areas: (1) knowing the scientific rationale for the intervention, (2) possessing the necessary psychomotor and interpersonal skills, and (3) being able to function within a particular setting to use the available health care resources effectively (Bulechek et al., 2008).

Types of Interventions

There are three categories of nursing interventions: nurse-initiated, physician-initiated, and collaborative interventions. Some patients require all three categories, whereas other patients need only nurse- and physician-initiated interventions.

Nurse-initiated interventions are the independent nursing interventions, or actions that a nurse initiates. These do not require an order from another health care professional. As a nurse you act independently on a patient’s behalf. Nurse-initiated interventions are autonomous actions based on scientific rationale. Examples include elevating an edematous extremity, instructing patients in side effects of medications, or repositioning a patient to achieve pain relief. Such interventions benefit a patient in a predicted way related to nursing diagnoses and patient goals (Bulechek et al., 2008). Nurse-initiated interventions require no supervision or direction from others. Each state within the United States has Nurse Practice Acts that define the legal scope of nursing practice (see Chapter 23). According to the Nurse Practice Acts in a majority of states, independent nursing interventions pertain to activities of daily living, health education and promotion, and counseling. For Mr. Jacobs Tonya selects anxiety-reduction interventions such as using a calm and reassuring approach, listening attentively, and providing factual information.

Physician-initiated interventions are dependent nursing interventions, or actions that require an order from a physician or another health care professional. The interventions are based on the physician’s or health care provider’s response to treat or manage a medical diagnosis. Advanced practice nurses who work under collaborative agreements with physicians or who are licensed independently by state practice acts are also able to write dependent interventions. As a nurse you intervene by carrying out the provider’s written and/or verbal orders. Administering a medication, implementing an invasive procedure (e.g., inserting a Foley catheter, starting an intravenous [IV] infusion), changing a dressing, and preparing a patient for diagnostic tests are examples of physician-initiated interventions.

Each physician-initiated intervention requires specific nursing responsibilities and technical nursing knowledge. You are often the one performing the intervention, and you must know the types of observations and precautions to take for the intervention to be delivered safely and correctly. For example, when administering a medication you are responsible for not only giving the medicine correctly, but also knowing the classification of the drug, its physiological action, normal dosage, side effects, and nursing interventions related to its action or side effects (see Chapter 31). You are responsible for knowing when an invasive procedure is necessary, the clinical skills necessary to complete it, and its expected outcome and possible side effects. You are also responsible for adequate preparation of the patient and proper communication of the results. You perform dependent nursing interventions, like all nursing actions, with appropriate knowledge, clinical reasoning, and good clinical judgment.

Collaborative interventions, or interdependent interventions, are therapies that require the combined knowledge, skill, and expertise of multiple health care professionals. Typically when you plan care for a patient, you review the necessary interventions and determine if the collaboration of other health care disciplines is necessary. A patient care conference with an interdisciplinary health care team results in selection of interdependent interventions.

In the case study involving Mr. Jacobs, Tonya plans independent interventions to help calm Mr. Jacobs’ anxiety and begin teaching him about postoperative care activities. Among the dependent interventions Tonya plans to implement are the administration of an analgesic and ordered wound care. Tonya’s collaborative intervention involves consulting with the unit discharge coordinator, who will help Mr. and Mrs. Jacobs plan for their return home and consult with the home health department to ensure that the Jacobs have home health visits.

When preparing for physician-initiated or collaborative interventions, do not automatically implement the therapy but determine whether it is appropriate for the patient. Every nurse faces an inappropriate or incorrect order at some time. The nurse with a strong knowledge base recognizes the error and seeks to correct it. The ability to recognize incorrect therapies is particularly important when administering medications or implementing procedures. Errors occur in writing orders or transcribing them to a documentation form or computer screen. Clarifying an order is competent nursing practice, and it protects the patient and members of the health care team. When you carry out an incorrect or inappropriate intervention, it is as much your error as the person who wrote or transcribed the original order. You are legally responsible for any complications resulting from the error (see Chapter 23).

Selection of Interventions

During planning do not select interventions randomly. For example, patients with the diagnosis of anxiety do not always need care in the same way with the same interventions. You treat anxiety related to the uncertainty of surgical recovery very differently than anxiety related to a threat to loss of family role function. When choosing interventions, consider six important factors: (1) characteristics of the nursing diagnosis, (2) goals and expected outcomes, (3) evidence base (e.g., research or proven practice guidelines) for the interventions, (4) feasibility of the intervention, (5) acceptability to the patient, and (6) your own competency (Bulechek et al., 2008) (Box 18-1). When considering a plan of care, review resources such as the nursing literature, standard protocols or guidelines, the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), critical pathways, policy or procedure manuals, or textbooks. Collaboration with other health professionals is also useful. As you select interventions, review your patient’s needs, priorities, and previous experiences to select the interventions that have the best potential for achieving the expected outcomes.

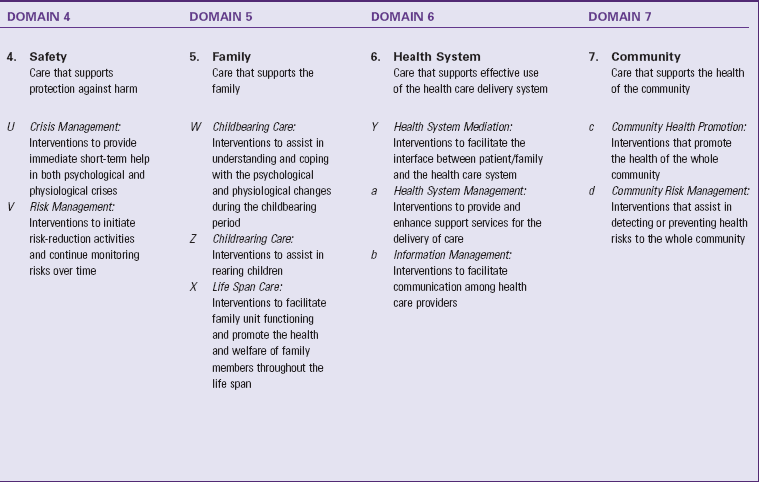

Nursing Interventions Classification

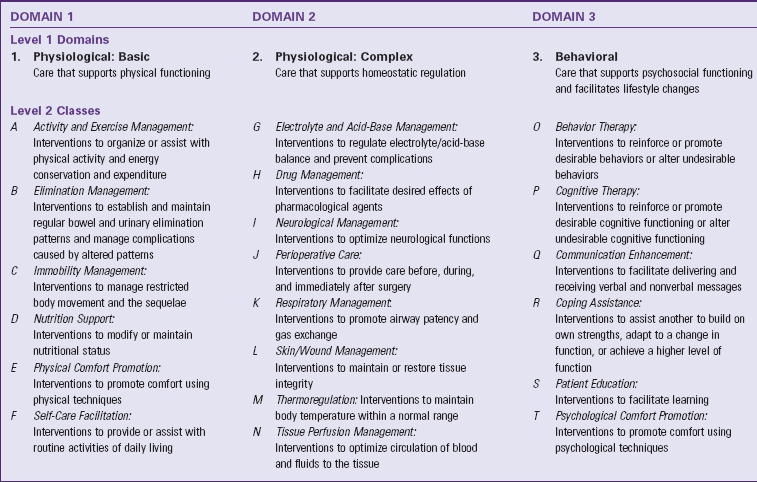

Just as with the standardized NOC, the Iowa Intervention Project has also developed a set of nursing interventions that provides a level of standardization to enhance communication of nursing care across all health care settings and to compare outcomes (Bulechek et al., 2008). The NIC model includes three levels: domains, classes, and interventions for ease of use. The domains are the highest level (level 1) of the model, using broad terms (e.g., safety and basic physiological) to organize the more specific classes and interventions (Table 18-3). The second level of the model includes 30 classes, which offer useful clinical categories to reference when selecting interventions. The third level of the model includes the 542 interventions, defined as any treatment based on clinical judgment and knowledge that a nurse performs to enhance patient outcomes (Bulechek et al., 2008) (Box 18-2). Each intervention then includes a variety of nursing activities from which to choose (Box 18-3) and which a nurse commonly uses in a plan of care. NIC interventions are also linked with NANDA International nursing diagnoses for ease of use (NANDA International, 2012). For example, if a patient has a nursing diagnosis of acute pain, there are 21 recommended interventions, including pain management, cutaneous stimulation, and anxiety reduction. Each of the recommended interventions has a variety of activities for nursing care. NIC is a valuable resource for selecting appropriate interventions and activities for your patient. It is evolving and practice oriented. The classification is comprehensive, including independent and collaborative interventions. It remains your decision to determine which interventions and activities best suit your patient’s individualized needs and situation.

Systems for Planning Nursing Care

In any health care setting a nurse is responsible for providing a nursing plan of care for all patients. The plan of care sometimes takes several forms (e.g., nursing Kardex, standardized care plans, and computerized plans). More hospitals today are adopting electronic health records (EHRs) and a documentation system that includes software programs for nursing care plans (Hebda et al., 2009). Generally a nursing care plan includes nursing diagnoses, goals and/or expected outcomes, specific nursing interventions, and a section for evaluation findings so any nurse is able to quickly identify a patient’s clinical needs and situation. Nurses revise a plan when a patient’s status changes. Electronic care plans often follow a standardized format, but you can individualize each plan to a unique patient’s needs (see Chapter 26). The standardized format is usually based on nursing diagnoses or select problem areas, which nurses are able to individualize for a specific patient. In hospitals and community-based settings, patients receive care from more than one nurse, physician, or allied health professional. Thus more institutions are developing interdisciplinary care plans, which include contributions from all disciplines involved in patient care. The interdisciplinary plan is designed to improve the coordination of all patient therapies and communication among all disciplines.

A nursing care plan reduces the risk for incomplete, incorrect, or inaccurate care. As the patient’s problems and status change, so does the plan. A nursing care plan is a guideline for coordinating nursing care, promoting continuity of care, and listing outcome criteria to be used later in evaluation (see Chapter 20). The plan of care communicates nursing care priorities to nurses and other health care professionals. It also identifies and coordinates resources for delivering nursing care. For example, in a care plan you list specific supplies necessary to use in a dressing change or names of clinical nurse specialists who are providing consultation for a patient.

The nursing care plan enhances the continuity of nursing care by listing specific nursing interventions needed to achieve the goals of care. All nurses who care for a given patient carry out these nursing interventions (e.g., throughout each day during a patient’s length of stay [in a hospital] or during weekly visits to the home [home health nursing]). A correctly formulated nursing care plan makes it easy to continue care from one nurse to another. The nursing care plan provides an example of a care plan for Mr. Jacobs, using the format found throughout this text.

A care plan includes a patient’s long-term needs. Incorporating the goals of the care plan into discharge planning is important. Thus it is beneficial to involve the family in planning care if the patient is agreeable. The family is often a resource to help the patient meet health care goals. In addition, meeting some of the family’s needs will possibly improve the patient’s level of wellness. Discharge planning is especially important for a patient undergoing long-term rehabilitation in the community and who will require ongoing home care. Same-day surgeries and earlier discharges from hospitals require you to begin planning discharge from the moment the patient enters the health care agency. The complete care plan is the blueprint for nursing action. It provides direction for implementation of the plan and a framework for evaluation of the patient’s response to nursing actions.

Change of Shift

The change-of-shift report is the standard practice used for off-going nurses leaving a shift to communicate information about the patient’s plan of care to oncoming patient care personnel. At the end of a shift you discuss your patients’ plans of care and their overall progress with the next caregivers. Thus all nurses are able to discuss current and relevant information about each patient’s plan of care. The newest term used to describe this process is nursing handoff. It is a critical time when nurses collaborate and share important information that ensures the continuity of care for a patient and prevents errors or delays in providing nursing interventions. In the past the change-of-shift report typically involved nurses leaving their report on an audiotape recorder, which would be heard by the oncoming nursing staff. This approach did not consistently allow staff from both shifts to share information one on one, ask questions, clarify misunderstandings, and validate the patients’ priority problems. Audiotapes are often difficult to hear, and frequently nurses omit information. In some agencies, the nursing handoff process occurs during walking rounds when nurses exchange information about patients at the bedside, giving patients the opportunity to also ask questions and confirm information. Recent research identifies approaches to use for effective handoffs and barriers to their effectiveness. However, there is no evidence for one best nursing hand-off practice (Riesenberg et al., 2010) (Box 18-4). Written care plans organize information exchanged by nurses in change-of-shift reports (see Chapter 26). You learn to focus your reports on the nursing care, treatments, and expected outcomes documented in the care plans. Avoid adding personal opinions about the patient since these are not relevant and could unnecessarily influence the oncoming nurse’s perception of him or her as an individual.

Student Care Plans

Student care plans are useful for learning the problem-solving technique, the nursing process, skills of written communication, and organizational skills needed for nursing care. Most important, a student care plan helps you apply knowledge gained from the nursing and medical literature and the classroom to a practice situation. Students typically write a care plan for each nursing diagnosis. The student care plan is more elaborate than a care plan used in a hospital or community agency because its purpose is to teach the process of planning care. Each school uses a different format for student care plans. Often, the format used is similar to the one used by the health care agency that provides students from that school their clinical experiences.

One example of a form of care plan developed by students is the six-column format. Starting from left to right, the six columns include: (1) assessment data relevant to corresponding diagnosis, (2) goals, (3) outcomes identified for the patient, (4) implementation for the plan of care, (5) a scientific rationale (the reason that you chose a specific nursing action, based on supporting evidence), and (6) a section to evaluate your care. In the implementation section you select the interventions appropriate for the patient. The following questions help you design a plan:

• When should each intervention be implemented?

• How should the intervention be performed for this specific patient?

Each scientific rationale that you use to support a nursing intervention needs to include a reference, whenever possible, to document the source from the scientific literature. This reinforces the importance of evidence-based nursing practice. It is also important that each intervention be specific and unique to a patient’s situation. Nonspecific nursing interventions result in incomplete or inaccurate nursing care, lack of continuity among caregivers, and poor use of resources. Common omissions that nurses make in writing nursing interventions include action, frequency, quantity, method, or person to perform them. These errors occur when nurses are unfamiliar with the planning process. Table 18-4 illustrates these types of errors by showing incorrect and correct statements of nursing interventions. The sixth column of the care plan includes a section for you to evaluate the plan of care: was each outcome fully or only partially met? Use the evaluation column to document whether the plan requires revision or when outcomes are met, thus indicating when a particular nursing diagnosis is no longer relevant to the patient’s plan of care (see Chapter 20).

TABLE 18-4

Frequent Errors in Writing Nursing Interventions

| TYPE OF ERROR | INCORRECTLY STATED NURSING INTERVENTION | CORRECTLY STATED NURSING INTERVENTION |

| Failure to precisely or completely indicate nursing actions | Turn patient every 2 hours. | Turn patient every 2 hours, using the following schedule: 8 am—supine 10 am—left side; Noon—prone 2 pm—right side Repeat at 4 pm and 2 am |

| Failure to indicate frequency | Perform blood glucose measurements. | Measure blood glucose before each meal: 7 am—11 am—5 pm. |

| Failure to indicate quantity | Irrigate wound once a shift: 6 am—2 pm—8 pm. | Irrigate wound with 100 mL normal saline until clear: 6 am—2 pm—8 pm. |

| Failure to indicate method | Change patient’s dressing once a shift: 6 am—2 pm—10 pm. | Replace patient’s dressing with Neosporin ointment to wound and two dry 4 × 4 dressings secured with hypoallergenic tape once a shift: 2 pm—10 pm—6 am. |

Care Plans for Community-Based Settings

Planning care for patients in community-based settings (e.g., clinics, community centers, or patients’ homes) involves using the same principles of nursing practice. However, in these settings you need to complete a more comprehensive community, home, and family assessment. Ultimately the patient/family unit must be able to independently provide the majority of health care. You design a plan to (1) educate the patient/family about the necessary care techniques and precautions, (2) teach the patient/family how to integrate care within family activities, and (3) guide the patient/family on how to assume a greater percentage of care over time. Finally the plan includes nurses’ and the patient’s/family’s evaluation of expected outcomes.

Critical Pathways

Critical pathways are patient care management plans that provide the multidisciplinary health care team with the activities and tasks to be put into practice sequentially (over time); their main purpose is to deliver timely care at each phase of the care process for a specific type of patient (Espinosa-Aguilar et al., 2008). A critical pathway clearly defines transition points in patient progress and draws a coordinated map of activities by which the health care team can help to make these transitions as efficient as possible. A pathway allows staff from all disciplines to develop integrated care plans for a projected length of stay or number of visits. Critical pathways improve continuity of care because they clearly define the responsibility of each health care discipline. Well-developed pathways include evidence-based interventions and therapies.

Concept Maps

Chapter 16 first described concept maps and their use in care planning. Because you care for patients who present with multiple health problems and related nursing diagnoses, it is often not realistic to have a written columnar plan developed for each nursing diagnosis. In addition, the columnar plans do not contain a means to show the association between different nursing diagnoses and different nursing interventions. A concept map offers you a visual representation of all patient nursing diagnoses and allows you to diagram interventions for each. You quickly see the relationship between the diagnoses and often how a single intervention often applies to more than one health problem. Concept maps group and categorize nursing concepts to give you a holistic view of your patient’s health care needs and help you make better clinical decisions in planning care.

In Chapter 17 you learned how to add nursing diagnostic labels to a concept map. When planning care for each nursing diagnosis, analyze the relationships among the diagnoses. Draw dotted lines between nursing diagnoses to indicate their relationship to one another (Fig. 18-3). It is important for you to make meaningful associations between one concept and another. The links need to be accurate, meaningful, and complete so you can explain why nursing diagnoses are related. For example, Mr. Jacobs’ anxiety and acute pain are interrelated; in addition, pain has an influence on his reduced mobility. Pain and anxiety both influence his ability to respond to instruction for his deficient knowledge.

Finally, on a separate sheet of paper or on the map itself, list nursing interventions to attain the outcomes for each nursing diagnosis. This step corresponds to the planning phase of the nursing process. While caring for the patient, use the map to write the patient’s responses to each nursing activity. Also write your clinical impressions and inferences regarding the patient’s progress toward expected outcomes and the effectiveness of interventions. Keep the concept map with you throughout the clinical day. As you revise the plan, take notes and add or delete nursing interventions. Use the information recorded on the map for your documentation of patient care. Critical thinkers learn by organizing and relating cognitive concepts. Concept maps help you learn the interrelationships among nursing diagnoses to create a unique meaning and organization of information.

Consulting Other Health Care Professionals

Planning involves consultation with members of the health care team. Consultation occurs at any step in the nursing process, but you consult most often during planning and implementation. During these times you are more likely to identify a problem requiring additional knowledge, skills, or resources. This requires you to be aware of your strengths and limitations as a team member. Consultation is a process by which you seek the expertise of a specialist such as your nursing instructor, a physician, or a clinical nurse educator to identify ways to handle problems in patient management or the planning and implementation of therapies. The consultation process is important so all health care providers are focused on common patient goals. Always be prepared before you make a consult. Consultation is based on the problem-solving approach, and the consultant is the stimulus for change.

Often an experienced nurse is a valuable consultant when you face an unfamiliar patient care situation such as a new procedure or a patient presenting a set of symptoms that you cannot identify. In clinical nursing, consultation helps to solve problems in the delivery of nursing care. For example, a nursing student consults a clinical specialist for wound care techniques or an educator for useful teaching resources. Nurses are consulted for their clinical expertise, patient education skills, or staff education skills. Nurses also consult with other members of the health care team such as physical therapists, nutritionists, and social workers. Again, the consultation focuses on problems in providing nursing care.

When to Consult

Consultation occurs when you identify a problem that you are unable to solve using personal knowledge, skills, and resources. The process requires good intrapersonal and interprofessional collaboration. Consultation with other care providers increases your knowledge about the patient’s problems and helps you learn skills and obtain resources. A good time to consult with another health care professional is when the exact problem remains unclear. An objective consultant enters a clinical situation and more clearly assesses and identifies the nature of a problem, whether it is patient, personnel, or equipment oriented. Most often you consult with health care providers who are working in your clinical area. However, sometimes you consult over the telephone (Box 18-5).

How to Consult

Begin with your own understanding of a patient’s clinical problems. The first step in making a consultation is to identify the general problem area. Second, direct the consultation to the right professional such as another nurse or social worker. Third, provide the consultant with relevant information about the problem area. Include a brief summary of the problem, methods used to resolve the problem so far, and outcomes of these methods. Also share information from the patient’s medical record, conversations with other nurses, and the patient’s family.

Fourth, do not prejudice or influence consultants. Consultants are in the clinical setting to help identify and resolve a nursing problem, and biasing or prejudicing them blocks problem resolution. Avoid bias by not overloading consultants with subjective and emotional conclusions about the patient and the problem.

Fifth, be available to discuss the consultant’s findings and recommendations. When you request a consultation, provide a private, comfortable atmosphere for the consultant and patient to meet. However, this does not mean that you leave the environment. A common mistake is turning the whole problem over to the consultant. The consultant is not there to take over the problem but to help you resolve it. When possible, request the consultation for a time when both you and the consultant are able to discuss the patient’s situation with minimal interruptions or distractions. Finally, incorporate the consultant’s recommendations into the care plan. The success of the advice depends on the implementation of the problem-solving techniques. Always give the consultant feedback regarding the outcome of the recommendations.

Key Points

• During planning determine patient goals, set priorities, develop expected outcomes of nursing care, and select interventions for the nursing care plan.

• Priorities help you anticipate and sequence nursing interventions when a patient has multiple nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems.

• Goals and expected outcomes provide clear direction for the selection and use of nursing interventions and the evaluation of the effectiveness of the interventions.

• In setting goals the time frame depends on the nature of the problem, etiology, overall condition of the patient, and treatment setting.

• A patient-centered goal is singular, observable, measurable, time limited, mutual, and realistic.

• An expected outcome is an objective criterion for goal achievement.

• Nurse-initiated interventions require no order and no supervision or direction from others.

• Physician-initiated interventions require specific nursing responsibilities and technical nursing knowledge.

• During a nursing handoff nurses collaborate and share important information that ensures the continuity of care for a patient and prevents errors or delays in providing nursing interventions.

• Care plans and critical pathways increase communication among nurses and facilitate the continuity of care from one nurse to another and from one health care setting to another.

• A concept map provides a visually graphic way to show the relationship between patients’ nursing diagnoses and interventions.

• The NIC taxonomy provides a standardization to help nurses select suitable interventions for patients’ problems.

• Correctly written nursing interventions include actions, frequency, quantity, method, and the person to perform them.

• Consultation increases your knowledge about a patient’s problem and helps in learning skills and obtaining the resources needed to solve the problem.

• When making a consultation, first identify the general problem, direct the consultation to the right professional, and provide the consultant with relevant information about the problem.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

Tonya sets out to formally plan Mr. Jacobs’ care. For the nursing diagnosis of impaired physical mobility related to incisional pain, Tonya identifies the goal of “Patient will walk 100 yards three times a day”; and the outcome she lists is, “Patient will report pain below level of 4 and will not splint incision when moving within 48 hours.” The interventions she selects for her plan include administering the ordered analgesic, progressive relaxation, and splinting the incision when the patient gets out of bed. The following three questions apply to the case study.

1. Critique the goal and outcomes that Tonya set and explain if they were written correctly.

2. Among the interventions that Tonya selected, which ones are independent, dependent, and collaborative?

3. What interventions will possibly increase the likelihood that the patient’s goals of care and outcomes will be met?

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. A nurse is assigned to a patient who has returned from the recovery room following surgery for a colorectal tumor. After an initial assessment the nurse anticipates the need to monitor the patient’s abdominal dressing, intravenous (IV) infusion, and function of drainage tubes. The patient is in pain, reporting 6 on a scale of 0 to 10, and will not be able to eat or drink until intestinal function returns. The family has been in the waiting room for an hour, wanting to see the patient. The nurse establishes priorities first for which of the following situations? (Select all that apply.)

1. The family comes to visit the patient.

2. The patient expresses concern about pain control.

3. The patient’s vital signs change, showing a drop in blood pressure.

4. The charge nurse approaches the nurse and requests a report at end of shift.

2. A patient signals the nurse by turning on the call light. The nurse enters the room and finds the patient’s drainage tube disconnected, 100 mL of fluid in the intravenous (IV) line, and the patient asking to be turned. Which of the following does the nurse perform first?

1. Reconnect the drainage tubing

2. Inspect the condition of the IV dressing

3. A nurse assesses a 78-year-old patient who weighs 240 pounds (108.9 kg) and is partially immobilized because of a stroke. The nurse turns the patient and finds that the skin over the sacrum is very red and the patient does not feel sensation in the area. The patient has had fecal incontinence on and off for the last 2 days. The nurse identifies the nursing diagnosis of risk for impaired skin integrity. Which of the following goals are appropriate for the patient? (Select all that apply.)

1. Patient will be turned every 2 hours within 24 hours.

2. Patient will have normal bowel function within 72 hours.

4. Setting a time frame for outcomes of care serves which of the following purposes?

1. Indicates which outcome has priority

2. Indicates the time it takes to complete an intervention

3. Indicates how long a nurse is scheduled to care for a patient

4. Indicates when the patient is expected to respond in the desired manner

5. A patient has been in the hospital for 2 days because of newly diagnosed diabetes. His medical condition is unstable, and the medical staff is having difficulty controlling his blood sugar. The physician expects that the patient will remain hospitalized at least 3 more days. The nurse identifies one nursing diagnosis as deficient knowledge regarding insulin administration related to inexperience with disease management. Which of the following patient care goals are long term?

1. Patient will explain relationship of insulin to blood glucose control.

2. Patient will self-administer insulin.

3. Patient will achieve glucose control.

4. Patient will describe steps for preparing insulin in a syringe.

6. A patient has been in the hospital for 2 days because of newly diagnosed diabetes. His medical condition is unstable, and the medical staff is having difficulty controlling his blood sugar. The physician expects that the patient will remain hospitalized at least 3 more days. The nurse identifies one nursing diagnosis as deficient knowledge regarding insulin administration related to inexperience with disease management. What does the nurse need to determine before setting the goal of “patient will self-administer insulin?” (Select all that apply.)

1. Goal within reach of the patient

2. The nurse’s own competency in teaching about insulin

7. The nurse writes an expected-outcome statement in measurable terms. An example is:

2. Patient will have less pain.

3. Patient will take pain medication every 4 hours.

4. Patient will report pain acuity less than 4 on a scale of 0 to 10.

8. A patient has the nursing diagnosis of nausea. The nurse develops a care plan with the following interventions. Which are examples of collaborative interventions?

1. Provide frequent mouth care.

2. Maintain intravenous (IV) infusion at 100 mL/hr.

3. Administer prochlorperazine (Compazine) via rectal suppository.

4. Consult with dietitian on initial foods to offer patient.

5. Control aversive odors or unpleasant visual stimulation that triggers nausea.

9. A 72-year-old patient has come to the health clinic with symptoms of a productive cough, fever, increased respiratory rate, and shortness of breath. His respiratory distress increases when he walks. He lives alone and did not come to the clinic until his neighbor insisted. He reports not getting his pneumonia vaccine this year. Blood tests show the patient’s oxygen saturation to be lower than normal. The physician diagnoses the patient as having pneumonia. Match the priority level with the nursing diagnoses identified for this patient:

| Nursing Diagnoses | Priority Level |

| 1. Impaired gas exchange _____ | a. Long term |

| 2. Risk for activity intolerance _____ | b. Short term |

| 3. Ineffective self-health management _____ | c. Intermediate |

10. An 82-year-old patient who resides in a nursing home has the following three nursing diagnoses: risk for fall, impaired physical mobility related to pain, and wandering related to cognitive impairment. The nursing staff identified several goals of care. Match the goals on the left with the appropriate outcome statements on the right.

| Goals | Outcomes |

| 1. Patient will ambulate independently in 3 days. _____ | a. Patient will express fewer nonverbal signs of discomfort. |

| 2. Patient will be injury free for 1 month. _____ | b. Patient will follow a set care routine. |

| 3. Patient will be less agitated. _____ | c. Patient will walk correctly using a walker. |

| 4. Patient will achieve pain relief. _____ | d. Patient will exit a low bed without falling. |

11. A nurse is preparing for change-of-shift rounds with the nurse who is assuming care for his patients. Which of the following statements or actions by the nurse are characteristics of ineffective handoff communication?

1. This patient is anxious about his pain after surgery; you need to review the information I gave him about how to use a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump this evening.

2. The nurse refers to the electronic care plan in the electronic health record (EHR) to review interventions for the patient’s care.

3. During walking rounds the nurse talks about the problem the patient care technicians created by not ambulating the patient.

4. The nurse gives her patient a pain medication before report so there is likely to be no interruption during rounding.

12. Which of the following outcome statements for the goal, “Patient will achieve a gain of 10 lbs (4.5 kg) in body weight in a month” are worded incorrectly? (Select all that apply.)

1. Patient will eat at least three fourths of each meal by 1 week.

2. Patient will verbalize relief of nausea and have no episodes of vomiting in 1 week.

3. Patient will eat foods with high-calorie content by 1 week.

13. A nurse from home health is talking with a nurse who works on an acute medical division within a hospital. The home health nurse is making a consultation. Which of the following statements describes the unique difference between a nursing care plan from a hospital versus one for home care?

1. The goals of care will always be more long term.

2. The patient and family need to be able to independently provide most of the health care.

3. The patient’s goals need to be mutually set with family members who will care for him or her.

4. The expected outcomes need to address what can be influenced by interventions.

14. Which outcome allows you to measure a patient’s response to care more precisely?

1. The patient’s wound will appear normal within 3 days.

2. The patient’s wound will have less drainage within 72 hours.

3. The patient’s wound will reduce in size to less than 4 cm ( inches) by day 4.

inches) by day 4.

4. The patient’s wound will heal without redness or drainage by day 4.

15. A nurse identifies several interventions to resolve the patient’s nursing diagnosis of impaired skin integrity. Which of the following are written in error? (Select all that apply.)

Answers: 1. 2, 3; 2. 1; 3. 2, 3; 4. 4; 5. 3; 6. 1, 3, 4; 7. 4; 8. 4; 9. 1b, 2c, 3a; 10. 1c, 2d, 3b, 4a; 11. 3; 12. 2, 4; 13. 2; 14. 3; 15. 1, 3.

References

Bastable, SB. Essentials of patient education. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett; 2006.

Bulechek, GM, et al. Nursing interventions classification (NIC), ed 5. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Carpenito-Moyet, LJ. Nursing diagnoses: application to clinical practice, ed 13. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

Espinosa-Aguilar, A, et al. Design and validation of a critical pathway for hospital management of patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2008;64(5):1327.

Hebda, T, et al. Handbook of informatics for nurses and health care professionals, ed 4. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2009.

Moorhead, S, et al. Nursing outcomes classification, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

NANDA International. nursing diagnoses: definitions and classification 2012-2014. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012.

Schumacher, K, et al. Family caregivers. Am J Nurs. 2006;106(8):40.

Vacarolis, EM, Halter, MJ. Essentials of psychiatric mental health nursing: a communication approach to evidence-based care. St Louis: Saunders; 2009.

Research References

Athwal, P, et al. Standardization of change-of-shift report. J Nurs Care Qual. 2009;24(2):143.

Hendry, C, Walker, A. Priority setting in clinical nursing practice: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(4):427.

Holmstrom, I, Hoglund, AT. The faceless encounter: ethical dilemmas in telephone nursing. J Clin Nurs. 2007;17(16):2237.

Hui, PN, et al. An evaluation of two behavioral rehabilitation programs, qigong versus progressive relaxation, in improving the quality of life in cardiac patients. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12(4):351.

Potter, P, et al. Understanding the cognitive work of nursing in the acute care environment. J Nurs Admin. 2005;35(7/8):327.

Riesenberg, LA, Leisch, J, Cunningham, JM. Nursing handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Nurs. 2010;110(4):24.