Managing Patient Care

• Differentiate among the types of nursing care delivery models.

• Describe the elements of decentralized decision making.

• Discuss the ways in which a nurse manager supports staff involvement in a decentralized decision-making model.

• Discuss ways to apply clinical care coordination skills in nursing practice.

• Discuss principles to follow in the appropriate delegation of patient care activities.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

As a nursing student it is important for you to acquire the necessary knowledge and competencies that ultimately allow you to practice as an entry-level staff nurse. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) identified competencies that registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practical/vocational nurses need on entry to practice (Kearney, 2009) (Box 21-1). Regardless of the type of setting in which you eventually choose to work as a staff nurse, you will be responsible for using organizational resources, participating in organizational routines while providing direct patient care, using time productively, collaborating with all members of the health care team, and using certain leadership characteristics to manage others on the nursing team. The delivery of nursing care within the health care system is a challenge because of the changes that influence health professionals, patients, and health care organizations (see Chapter 2). However, change offers opportunities. As you develop the knowledge and skills to become a staff nurse, you learn what it takes to effectively manage the patients for whom you care and to take the initiative in becoming a leader among your professional colleagues.

Building a Nursing Team

Nurses are self-directed and, with proper leadership and motivation, are able to solve most complex problems. A nurse’s education and commitment to practicing within established standards and guidelines ensures a rewarding professional career. As a nurse it is also important to work in an empowering environment as a member of a solid and strong nursing team. A strong nursing team works together to achieve the best outcomes for patients (Batcheller et al., 2004).

Building an empowered nursing team begins with the nurse executive, who is often vice president or director of nursing. The executive’s position within an organization is critical in uniting the strategic direction of an organization with the philosophical values and goals of nursing. The nurse executive is both a clinical and business leader who is concerned with maximizing quality of care and cost-effectiveness while maintaining relationships and professional satisfaction of the staff. The relationship between the nurse and nurse manager contributes to job satisfaction and retention (Ulrich et al., 2005). Perhaps the most important responsibility of the nurse executive is to establish a philosophy for nursing that enables managers and staff to provide quality nursing care. In this environment staff members have high levels of productivity and make contributions to the success of the organization (Feltner et al., 2008). Box 21-2 identifies the characteristics of an effective nurse leader.

It takes an excellent nurse manager and an excellent nursing staff to make an empowering work environment. Together a manager and the nursing staff have to share a philosophy of care for their work unit. A philosophy of care includes the professional nursing staff’s values and concerns for the way they view and care for patients. For example, a philosophy addresses the purpose of the nursing unit, how staff works with patients and families, and the standards of care for the work unit. Selection of a nursing care delivery model and a management structure that supports professional nursing practice are essential to the philosophy of care.

Magnet Recognition

One way of creating an empowering work environment is through the Magnet Recognition Program (see Chapter 2). A Magnet hospital has a transformed culture with a practice environment that is dynamic, autonomous, collaborative, and positive for nurses. The culture focuses on concern for patients. Typically a Magnet hospital has clinical promotion systems and research and evidence-based practice programs. The nurses have professional autonomy over their practice and control over the practice environment (Upenieks and Sitterding, 2008). A Magnet hospital empowers the nursing team to make changes and be innovative. Professional nurse councils at the organizational and unit level are one way to create an empowerment model. An effective empowerment model leads to a staff that feels valued and has increased autonomy and a work environment that promotes job satisfaction (Gokenbach, 2007).This culture and empowerment combine to produce a strong collaborative relationship among team members and improve patient quality outcomes (Box 21-3).

Nursing Care Delivery Models

Since the time of Florence Nightingale nurses have used a variety of nursing care delivery models to provide care for patients. Ideally the philosophy that nurses establish for the quality care of patients guides the selection of a care delivery model. However, too often a lack of nursing resources and business plans from the health care organization influences the final decision. A care delivery model needs to help nurses achieve desirable outcomes for their patients, either in the way work is organized or in the way a nurse’s responsibilities are defined. Important factors contributing to success of a care delivery model are decision-making authority for nurses who provide direct care, autonomy, collaborative practice, and effective methods of communicating with colleagues, physicians, and other health care providers (Tiedeman and Lookinland, 2004). In effective nursing models, the experienced RN provides faster diagnosis and intervention, which promotes a safe patient environment (Berkow et al., 2007).

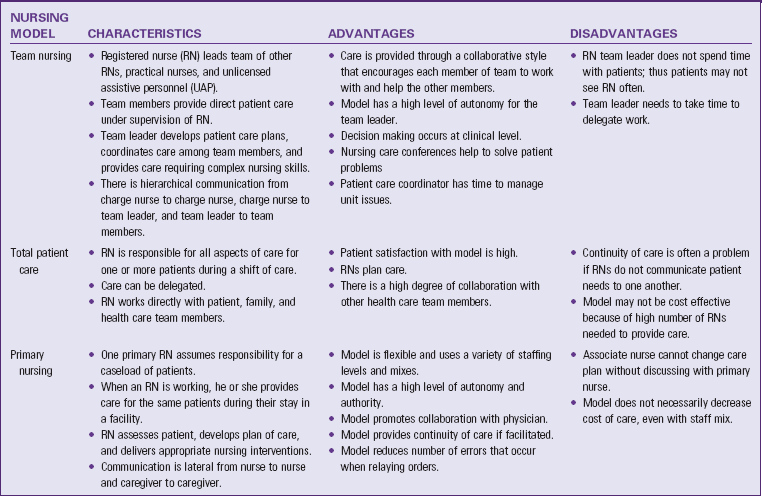

Three common models are team nursing, total patient care, and primary nursing. Team nursing developed in response to the severe nursing shortage following World War II. By 2000 the interdisciplinary team was a more common model (Marriner Tomey, 2009). Total patient care delivery was the original care delivery model developed during Florence Nightingale’s time. The model disappeared in the 1930s and became popular again during the 1970s and 1980s, when the number of RNs increased (Tiedeman and Lookinland, 2004). The primary nursing model of care delivery was developed to place RNs at the bedside and improve the accountability of nursing for patient outcomes and the professional relationships among staff members (Marriner Tomey, 2009). The model became more popular in the 1970s and early 1980s as hospitals began to employ more RNs. Primary nursing supports a philosophy regarding nurse and patient relationships. Table 21-1 summarizes the three nursing models.

TABLE 21-1

Modified from Marriner Tomey A: Guide to nursing management and leadership, ed 8, St Louis, 2009, Mosby; Tiedeman ME, Lookinland S: Traditional models of care delivery: what have we learned? J Nurs Adm 34(6):291, 2004.

Case management is a care management approach that coordinates and links health care services to patients and their families while streamlining costs and maintaining quality (Marriner Tomey, 2009) (see Chapter 2). The Case Management Society of America (2010) defines case management as “a collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality cost-effective outcomes.” Case management is unique because clinicians, either as individuals or as part of a collaborative group, oversee the management of patients with specific, complex health problems or are held accountable for some standard of cost management and quality.

For example, a case manager coordinates a patient’s acute care in the hospital and follows up with the patient after discharge home. Case managers do not always provide direct care but instead work with and supervise the care delivered by other staff and health care team members and actively coordinate patient discharge planning. Ongoing communication with team members facilitates the patient’s transition to home (Carr, 2007). In this situation the case manager helps the patient identify health needs, determine the services and resources that are available, and make cost-efficient choices (Marriner Tomey, 2009). The case manager frequently oversees a caseload of patients with complex nursing and medical problems. Often he or she is an advanced practice nurse who, through specific interventions, helps to improve patient outcomes, optimize patient safety by facilitating care transitions, decrease length of stay, and lower health care costs (Carr, 2007; Thomas, 2008).

Many organizations use critical pathways or CareMaps in a case management delivery system (see Chapter 18). These are multidisciplinary treatment plans for specific cases. The case manager, along with members of the health care team, uses the critical pathways or CareMaps to implement timely interventions in a coordinated plan of care. The plans eliminate the guesswork in patient care because all members of the health care team work from the same plan.

Decision Making

With a philosophy for nursing established, it is the manager who directs and supports staff in the realization of that philosophy. The nurse executive supports managers by establishing a structure that helps to achieve organizational goals and provide appropriate support to care delivery staff. It takes a committed nurse executive, an excellent manager, and an empowered nursing staff to create an enriching work environment in which nursing practice thrives.

Decentralized management, in which decision making is moved down to the level of staff, is very common within health care organizations. This type of management structure has the advantage of creating an environment in which managers and staff become more actively involved in shaping the identity and determining the success of a health care organization. Working in a decentralized structure has the potential for greater collaborative effort, increased competency of staff, increased staff motivation, and ultimately a greater sense of professional accomplishment and satisfaction.

Progressive organizations achieve more when employees at all levels are actively involved. As a result, the role of a nurse manager is critical in the management of effective nursing units or groups. Box 21-4 highlights the diverse responsibilities of nursing managers. To make decentralized decision making work, managers need to know how to move it down to the lowest level possible. On a nursing unit it is important for all nursing staff members (RNs, licensed practical nurses [LPNs], and licensed vocational nurses [LVNs]), nurse assistants, and unit secretaries to become involved. They need to be kept well informed. They also need to be given the opportunity by managers to participate in problem-solving activities, including opportunities in direct patient care and unit activities such as committee participation. Important elements of the decision-making process are responsibility, autonomy, authority, and accountability (Anders and Hawkins, 2006).

Responsibility refers to the duties and activities that an individual is employed to perform. A position description outlines a professional nurse’s responsibilities. Nurses meet these responsibilities through participation as members of the nursing unit.

Responsibility reflects ownership. The individual who manages the employee has to distribute responsibility, and the employee has to accept it. Managers have to be sure that staff clearly understand their responsibilities, particularly in the face of change. For example, when hospitals participate in work redesign, patient care delivery models change significantly. A manager is responsible for clearly defining the RN’s role within the new care delivery model. If decentralized decision making is in place, professional staff have a voice in identifying the new RN role. Each RN on the work team is responsible for knowing his or her role and how to perform that role on the busy nursing unit. For example, primary nurses are responsible for completing a nursing assessment of all assigned patients and developing a plan of care that addresses each of the patient’s nursing diagnoses (see Chapters 15 to 20). As the staff delivers the plan of care, the primary nurse evaluates whether the plan is successful. This responsibility becomes a work ethic for the nurse in delivering excellent patient care.

Autonomy is freedom of choice and responsibility for the choices (Marriner Tomey, 2009). Autonomy consistent with the scope of professional nursing practice maximizes your effectiveness as a nurse (Weston, 2008). With clinical autonomy a professional nurse makes independent decisions about patient care, planning nursing care for the patient within the scope of professional nursing practice. The nurse implements independent nursing interventions (Weston, 2008) (see Chapter 18). Another type of autonomy for nurses is work autonomy. In work autonomy the nurse makes independent decisions about the work of the unit such as scheduling or unit governance (Weston, 2008). Autonomy is not an absolute; it occurs in degrees. For example, a nurse has the autonomy to develop and implement a discharge teaching plan based on specific patient needs for any hospitalized patient. He or she also provides nursing care that complements the prescribed medical therapy.

Authority refers to legitimate power to give commands and make final decisions specific to a given position (Anders and Hawkins, 2006; Marriner Tomey, 2009). For example, a primary nurse managing a caseload of patients discovers that members of the nursing team did not follow through on a discharge teaching plan for an assigned patient. The primary nurse has the authority to consult other nurses to learn why the team did not follow recommendations on the plan of care and to choose appropriate teaching strategies for the patient that all members of the team will follow. The primary nurse has the final authority in selecting the best course of action for the patient’s care.

Accountability refers to individuals being answerable for their actions. It means that as a nurse you accept the commitment to provide excellent patient care and the responsibility for the outcomes of the actions in providing that care (Anders and Hawkins, 2006). A primary nurse is accountable for his or her patients’ outcomes and for ensuring that each patient learns the information necessary to improve self-care. The nurse demonstrates accountability by checking on the patient and family after discharge and reviewing with the nursing team whether continuity in teaching occurred.

A successful decentralized nursing unit supports the four elements of decision making: responsibility, autonomy, authority, and accountability. An effective manager sets the same expectations for the staff in how decisions are made. Staff routinely meet to discuss and negotiate how to maintain an equality and balance in the elements. Staff members need to feel comfortable in expressing differences of opinion and challenging ways in which the team functions while recognizing their own responsibility, autonomy, authority, and accountability. Ultimately decentralized decision making helps create the philosophy of professional nursing care for the unit.

Staff Involvement

When decentralized decision making exists on a nursing unit, all staff members actively participate in unit activities (Fig. 21-1). The influence and control that nurses have over their practice contribute to job satisfaction (Schmalenberg and Kramer, 2008). Because the work environment promotes participation, all staff members benefit from the knowledge and skills of the entire work group. If the staff learns to value knowledge and the contributions of co-workers, better patient care is an outcome. Experienced RNs provide leadership and mentoring on a nursing unit while promoting collaborative practice (Berkow et al., 2007). The nursing manager supports staff involvement through a variety of approaches:

FIG. 21-1 Staff collaborating on practice issues. (From Yoder-Wise P: Leading and managing in nursing, ed 5, St Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

1. Establishing nursing practice or problem-solving committees or professional shared governance councils. Chaired by senior clinical staff, these groups establish and maintain care standards for nursing practice on their work unit. Shared governance councils promote empowerment in staff nurses and enable them to control their nursing practice (Kramer et al., 2008, 2010). The committees review and establish standards of care, develop policy and procedures, resolve patient satisfaction issues, or develop new documentation tools. It is important for the committees to focus on patient outcomes rather than only work issues to ensure quality care on the unit. Quality of care is further improved when nurses control their own practice (Anders and Hawkins, 2006). The committee establishes methods to ensure that all staff have input or participation on practice issues. Managers do not always sit on a committee, but they receive regular reports of committee progress. The nature of work on the nursing unit determines committee membership. At times members of other disciplines (e.g., pharmacy, respiratory therapy, or clinical nutrition) participate in practice committees or shared governance councils.

2. Nurse/physician collaborative practice. Collaboration is a process between individuals. There is a sharing of different perspectives that are then synthesized to better understand complex problems. An outcome of collaboration is a shared solution that could not have been accomplished by a single person or organization. Nurse-physician collaboration improves patient safety and outcomes and reduces errors (Manojlovich et al., 2008; Seago, 2008). The care delivery model of the nursing unit, an environment that supports teamwork, and organizational values influence how nurses and physicians collaborate. An open communication system that fosters respect, trust, shared decision making, and teamwork among all team members is critical to achieving quality patient care (Cronenwett et al., 2007). Physicians sometimes attend practice committees when clinical problems arise and present timely in-service programs.

3. Interdisciplinary collaboration. The emphasis on efficiency in health care delivery brings all members of the health care team together. Teamwork decreases mistakes because team members commit to shared knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Baker et al., 2006). Interdisciplinary collaboration leads to decreased patient mortality, decreased health care costs, and increased nurse job satisfaction (Manojlovich et al., 2008). Mutual respect is a critical part of any collaborative relationship (Ulrich et al., 2005). Essential characteristics for effective teams include having a common purpose, communicating frequently, anticipating one another, trust, managing conflict well, and providing feedback to one another (Baker et al., 2006). Use your judgment to decide which problems are complex and require a collaborative process. At the patient care level, staff recognize the importance of prompt referrals and timely communication with other health professionals. Participating in interdisciplinary patient care rounds, use of protocols and critical pathways, and holding interdisciplinary training for collaboration development are strategies that promote interdisciplinary collaboration (Kramer et al., 2010). Other strategies include having representatives of the various disciplines together in practice projects, in-service programs, conferences, and staff meetings.

4. Staff communication. A manager’s greatest challenge, especially if a work group is large, is communication with staff. It is difficult to make sure that all staff members receive the same message: the correct message. In the present health care environment, staff quickly become uneasy and distrusting if they fail to hear about planned changes on their work unit. However, a manager cannot assume total responsibility for all communication. An effective manager uses a variety of approaches to communicate quickly and accurately to all staff. For example, many managers distribute biweekly or monthly newsletters of ongoing unit or agency activities. Minutes of committee meetings are usually in an accessible location for all staff to read. When the team needs to discuss important issues regarding the operations of the unit, the manager conducts staff meetings. When the unit has practice or quality improvement committees, each committee member has the responsibility to communicate directly to a select number of staff members. Thus all staff members are contacted and given the opportunity for input.

5. Staff education. A professional nursing staff needs to always grow in knowledge. It is impossible to remain knowledgeable about current medical and nursing practice trends without ongoing education. The nurse manager is responsible for making learning opportunities available so staff members remain competent in their practice. This involves planning in-service programs, sending staff to continuing education classes and professional conferences, and having staff present case studies or practice issues during staff meetings. Staff members are responsible for pursuing educational opportunities when they know that their competencies are lacking.

Leadership Skills for Nursing Students

It is important that as a nursing student you prepare yourself for leadership roles. This does not mean that you have to quickly learn how to lead a team of nursing staff. Instead first learn to become a dependable and competent provider of patient care. As a nursing student you are responsible and accountable for the care you give to your patients. Learn to become a leader by consulting with instructors and nursing staff to obtain feedback in making good clinical decisions, learning from mistakes and seeking guidance, working closely with professional nurses, and trying to improve your performance during each patient interaction. These skills require you to think critically and solve problems in the clinical setting. Thinking critically allows nurses to provide higher quality care, meet the needs of patients while considering their preferences, consider alternatives to problems, understand the rationale for performing nursing interventions, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions (Benner et al., 2008). Clinical experiences develop these critical thinking skills (Toofany, 2008). Important leadership skills to learn include clinical care coordination, team communication, delegation, and knowledge building.

Clinical Care Coordination

You acquire necessary skills so you can deliver patient care in a timely and effective manner. In the beginning this often involves only one patient, but eventually it will involve groups of patients. Clinical care coordination includes clinical decision making, priority setting, use of organizational skills and resources, time management, and evaluation. The activities of clinical care coordination require use of critical reflection, critical reasoning, and clinical judgment (Benner et al., 2008). They are important first steps in developing a caring relationship with a patient. Use a critical thinking approach, applying previous knowledge and experience to the decision-making process (see Chapter 15).

Clinical Decisions

Your ability to make clinical decisions depends on application of the nursing process (see Chapters 16 to 20). When you begin a patient assignment, the first activity involves a focused but complete assessment of the patient’s condition so you are able to make an accurate judgment about his or her nursing diagnoses and collaborative health problems (see Chapter 16). This initial contact is an important first step in developing a caring relationship with a patient. Following the identification of a patient’s diagnoses and problems, you develop a plan of care, implement nursing interventions, and evaluate patient outcomes. The process requires clinical decision making, using a critical thinking approach (see Chapter 15).

If you do not make accurate clinical decisions about a patient, undesirable outcomes will probably occur. The patient’s condition worsens or remains the same when you lose the potential for improvement. An important lesson in organizational skills is to be thorough. Learn to attend and listen to the patient, look for any cues (obvious or subtle) that point to a pattern of findings, and direct the assessment to explore the pattern further. Accurate clinical decision making keeps you focused on the proper course of action. Never hesitate to ask for assistance when a patient’s condition changes.

Priority Setting

After forming a picture of the patient’s total needs, you set priorities by deciding which patient needs or problems need attention first (see Chapter 18). It is important to prioritize in all caregiving situations because it allows you to see relationships among patient problems and avoid delays in taking action that possibly leads to serious complications for a patient (Hendry and Walker, 2004). If a patient is experiencing serious physiological or psychological problems, the priority becomes clear. You need to act immediately to stabilize his or her condition. Hendry and Walker (2004) classify patient problems in three priority levels:

• High priority—An immediate threat to a patient’s survival or safety such as a physiological episode of obstructed airway, loss of consciousness, or a psychological episode of an anxiety attack.

• Intermediate priority—Nonemergency, non–life-threatening actual or potential needs that the patient and family members are experiencing. Anticipating teaching needs of patients related to a new drug and taking measures to decrease postoperative complications are examples of intermediate priorities.

• Low priority—Actual or potential problems that are not directly related to the patient’s illness or disease. These problems are often related to developmental needs or long-term health care needs. An example of a low priority problem is a patient at admission who will eventually be discharged and needs teaching for self-care in the home.

Many patients have all three types of priorities, requiring you to make careful judgments in choosing a course of action. Obviously high-priority needs demand immediate attention. When a patient has diverse priority needs, it helps to focus on his or her basic needs. For example, a patient who is in traction reports being uncomfortable from being in the same position. The dietary assistant arrives in the room to deliver a meal tray. Instead of immediately assisting the patient with the meal, you reposition him and offer basic hygiene measures. The patient likely becomes more interested in eating after he is more comfortable. He also is more receptive to any instruction you want to provide.

Eventually you will be required to meet the priority needs of a group of patients. This means that you need to know the priority needs of each patient within the group, assessing each patient’s needs as soon as possible while addressing high priorities first. To identify which patients require assessment first, rely on information from the change-of-shift report, the classification system of the agency that identifies patient acuity, and information from the medical record. Over time you learn to spontaneously rank patients’ needs by priority or urgency. Priorities do not remain stable but change as a patient’s condition changes. It is important to think about the resources available, be flexible in recognizing that priority needs often change, and consider how to use time wisely.

You also make priorities on the basis of patient expectations. Sometimes you have established an excellent plan of care; however, if the patient is resistant to certain therapies or disagrees with the approach, you have very little success. Working closely with the patient and showing a caring attitude are important. Share the priorities you have defined with the patient to establish a level of agreement and cooperation.

Organizational Skills

Implementing a plan of care requires you to be effective and efficient. Effective use of time means doing the right things, whereas efficient use of time means doing things right. Learn to become efficient by combining various nursing activities—in other words, doing more than one thing at a time. For example, during medication administration or while obtaining a specimen, combine therapeutic communication, teaching interventions, and assessment and evaluation. Always try to establish and strengthen relationships with patients and use any patient contact as an opportunity to convey important information. Patient interaction gives you the chance to show caring and interest. Always attend to the patient’s behaviors and responses to therapies to assess if new problems are developing and evaluate responses to interventions.

A well-organized nurse approaches any planned procedure by having all of the necessary equipment available and making sure that the patient is prepared. If the patient is comfortable and well informed, the likelihood that the procedure will go smoothly increases. Sometimes you require the assistance of colleagues to perform or complete a procedure. It is always wise to have the work area organized and preliminary steps completed before asking co-workers for assistance.

As you begin to deliver care based on established priorities, events sometimes occur within the health care setting that interfere with plans. For example, just as you begin to provide morning hygiene for a hospitalized patient, an x-ray technician enters to take a chest x-ray film. Once the technician completes the x-ray examination, a phlebotomist arrives to draw a blood sample. In this case your priorities seem to conflict with the priorities of other health care personnel. It is important to always keep the patient’s needs at the center of attention. If the patient experienced symptoms earlier that required a chest x-ray film and laboratory work, it is important to be sure that the diagnostic tests are completed. In another example a patient is waiting to visit family, and a chest x-ray film is a routine order from 2 days earlier. The patient’s condition has stabilized, and the x-ray technician is willing to return later to shoot the film. In this case attending to the patient’s hygiene and comfort so family members can visit is more of a priority.

Use of Resources

Appropriate use of resources is an important aspect of clinical care coordination. Resources in this case include members of the health care team. In any setting the administration of patient care occurs more smoothly when staff members work together. Never hesitate to have staff assist you, especially when there is an opportunity to make a procedure or activity more comfortable and safer for the patient. For example, assistance in turning, positioning, and ambulating patients is frequently necessary when patients are unable to move. Having a staff member, such as nursing assistive personnel (NAP), assist with handling equipment and supplies during more complicated procedures such as catheter insertion or dressing change helps make procedures more efficient. In addition, you often have to recognize personal limitations and use professional resources for assistance. For example, you assess a patient and find relevant clinical signs and symptoms but are unfamiliar with the physical condition. Consulting with an RN confirms findings and ensures that you take the proper course of action for the patient. A leader knows his or her limitations and seeks professional colleagues for guidance and support.

Time Management

Changes in health care and increasing complexity of patients create stress for nurses as they work to meet patient needs (Marriner Tomey, 2009). One way to manage this stress is through the use of time management skills. These skills involve learning how, where, and when to use your time. Because you have a limited amount of time with patients, it is essential to remain goal oriented and use it wisely. You quickly learn the importance of using patient goals as a way to identify priorities. However, also learn how to establish personal goals and time frames. For example, you are caring for two patients on a busy surgical nursing unit. One had surgery the day before, and the other will be discharged the next day. Clearly the first patient’s goals center on restoring physiological function impaired as a result of the stress of surgery. The second patient’s goals center on adequate preparation to assume self-care at home. In reviewing the therapies required for both patients, you learn how to organize your time so the activities of care and patient goals are achieved. You need to anticipate when care will be interrupted for medication administration and diagnostic testing and when is the best time for planned therapies such as dressing changes, patient education, and patient ambulation. Delegation of tasks is another way to help improve time management.

One useful time-management skill involves making a priority to-do list (Hackworth, 2008). When you first begin working with a patient or patients, it helps to make a list that sequences the nursing activities you need to perform. The change-of-shift report helps to sequence activities based on what you learn about the patient’s condition and the care provided before you arrive on the unit. It is helpful to consider activities that have specific time limits in terms of addressing patient needs such as administering a pain medication before a scheduled procedure or instructing patients before their discharge home. You also analyze the items on the list that are scheduled by agency policies or routines (e.g., medications or intravenous [IV] tubing changes). Note which activities need to be done on time and which activities you can do at your discretion. You have to administer medication within a specific schedule, but you are also able to perform other activities while in the patient’s room. Finally, estimate the amount of time needed to complete the various activities. Activities requiring the assistance of other staff members usually take longer because you have to plan around their schedules.

Good time management also involves setting goals to help you complete one task before starting another (Hackworth, 2008). If possible complete the activities started with one patient before moving on to the next. Care is then less fragmented, and you are better able to focus on what you are doing for each patient. As a result, it is less likely that you will make errors. Time management requires an ability to anticipate the activities of the day and combine activities when possible. Other strategies to help you manage your time are keeping your work area clean and clutter free and trying to decrease interruptions as you are completing tasks (Pearce, 2007). Box 21-5 summarizes principles of time management.

Evaluation

Evaluation is one of the most important aspects of clinical care coordination (see Chapter 20). It is a mistake to think that evaluation occurs at the end of an activity. It is an ongoing process. Once you assess a patient’s needs and begin therapies directed at a specific problem area, immediately evaluate whether therapies are effective and the patient’s response. The process of evaluation compares actual patient outcomes with expected outcomes. For example, a clinic nurse assesses a foot ulcer of a patient who has diabetes to determine if healing has progressed since the last clinic visit. When expected outcomes are not met, evaluation reveals the need to continue current therapies for a longer period, revise approaches to care, or introduce new therapies. As you care for a patient throughout the day, anticipate when to return to the bedside to evaluate care (e.g., 30 minutes after a medication was administered, 15 minutes after an IV line has begun infusing, or 60 minutes after discussing discharge instructions with the patient and family).

Keeping a focus on evaluation of the patient’s progress lessens the chance of becoming distracted by the tasks of care. It is common to assume that staying focused on planned activities ensures that you will perform care appropriately. However, task orientation does not ensure good patient outcomes. Learn that at the heart of good organizational skills is the constant inquiry into the patient’s condition and progress toward an improved level of health.

Team Communication

As a part of a nursing team, you are responsible for open, professional communication. Regardless of the setting, an enriching professional environment is one in which staff members respect one another’s ideas, share information, and keep one another informed. On a busy nursing unit this means keeping colleagues informed about patients with emerging problems, physicians who have been called for consultation, and unique approaches that solved a complex nursing problem. Strategies to improve your communication with physicians include addressing the physician by name, having the patient and chart available when discussing patient issues, focusing on the patient problem, and being professional and not aggressive (Nadzam, 2009). In a clinic setting it may mean sharing unusual diagnostic findings or conveying important information regarding a patient’s source of family support. One way of fostering good team communication is by setting expectations of one another. A nurse treats colleagues with respect, listens to the ideas of other staff members without interruption, explores the way other staff members think, and is honest and direct while communicating. Part of good communication is clarifying what others are saying and building on the merits of co-workers’ ideas (Marriner Tomey, 2009). An efficient team knows that it is able to count on all members when needs arise. Sharing expectations of what, when, and how to communicate is a step toward establishing a strong work team. Structured communication techniques that improve communication include briefings or short discussions among team members, group rounds on patients, and the use of Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation (SBAR) when sharing information (see Chapter 26) (Nadzam, 2009).

Delegation

The art of effective delegation is a skill you need to observe and practice to improve your own management skills. The American Nurses Association (1995) defined delegation as transferring responsibility for the performance of an activity or task while retaining accountability for the outcome. Delegation results in achievement of quality patient care, improved efficiency, increased productivity, empowered staff, and development of others (Huston, 2009; Marriner Tomey, 2009). Asking a staff member to obtain an ordered specimen while you attend to a patient’s pain medication request effectively prevents a delay in the patient gaining pain relief and accomplishes two tasks related to the patient. Delegation also provides job enrichment. You show trust in colleagues by delegating tasks to them and showing staff members that they are important players in the delivery of care. Successful delegation is important to the quality of the RN-NAP relationship and their willingness to work together (Bittner and Gravlin, 2009; Potter et al., 2010). Never delegate a task that you dislike doing or would not do independently because this creates negative feelings and poor working relationships (Huston, 2009). For example, if you are in the room when a patient asks to be placed on a bedpan, you assist the patient rather than leave the room to find the nurse assistant. Remember that, even though the delegation of a task transfers the responsibility and authority to another person, you are accountable for the delegated task.

As a nurse you are responsible and accountable for providing care to patients and delegating care activities to NAP. However, the nurse does not delegate the steps of the nursing process of assessment, diagnosis, planning, and evaluation because these steps require nursing judgment (American Nurses Association [ANA] and National Council of State Boards of Nursing [NCSBN], 2005). recognize that when you delegate to NAP, you delegate tasks, not patients. Do not give NAP sole responsibility for the care of patients. Instead, it is you as the professional nurse in charge of patient care who decides which activities NAP perform independently and which the RN and NAP perform in partnership. One way to accomplish this is to have the RN and technician or NAP conduct rounds together. You assess each patient as the technician helps to attend to basic patient needs. Care is delegated based on assessment findings and priority setting. As an RN, you are always responsible for the assessment of a patient’s ongoing status; but if a patient is stable you delegate vital sign monitoring to NAP.

The RN is the one in most settings who decides when delegation is appropriate. The LPN directs care in many long-term care facilities. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (1995) has provided some guidelines for delegation of tasks in accordance with an RN’s legal scope of practice (Box 21-6). As the leader of the health care team, the RN gives clear instructions, effectively prioritizes patient needs and therapies, and gives staff timely and meaningful feedback. NAP respond positively when you include them as part of the nursing team.

Appropriate delegation begins with knowing which skills you are able to delegate. This requires you to be familiar with the Nurse Practice Act of the state, institutional policies and procedures, and job description for NAP provided by the institution. These standards help to define the necessary level of competency of NAP.

An institution’s policies, procedures, and job description for NAP contain specific guidelines regarding which tasks or activities a nurse is able to delegate. The job description identifies any required education and the types of tasks NAP can perform, either independently or with RN direct supervision. Institutional policy defines the amount of training required of NAP while employed. Procedures detail who is qualified to perform a given nursing procedure, whether supervision is necessary, and the type of reporting required. You need to have a means to easily access policies or have supervisory staff who inform you about NAP’s job duties.

As a professional nurse you cannot simply assign NAP to tasks without considering the implications. Assess a patient and determine a plan of care before identifying which tasks someone else is able to perform. When directing NAP, determine how much supervision is necessary. Is it the first time a staff member performed the task? Does the patient present a complicating factor that makes the RN’s assistance necessary? Does the staff member have prior experience with a particular type of patient in addition to having received training on skill performance? The final responsibility is to evaluate whether NAP performed a task properly and whether desired outcomes were met.

Efficient delegation requires constant communication (i.e., sending clear messages and listening so all participants understand expectations regarding patient care) (Gravlin and Bittner, 2010). Provide clear instructions when delegating tasks. These instructions initially focus on the procedure itself, what will be accomplished, and the unique needs of a patient. The RN also communicates when and what information to report such as expected observations and specific patient concerns (NCSBN, 2005). Communication is a two-way process in delegation; thus NAP need to have the chance to ask questions and have your expectations made clear (ANA and NCSBN, 2005; NCSBN, 2005). Conflict often occurs between RNs and NAP when there is little or poor communication (Potter et al., 2010). Handoff disconnects, lack of knowledge about the workload of team members, and difficulty dealing with conflict are examples of communication failures that often result in delegation ineffectiveness and omissions of nursing care (Gravlin and Bittner, 2010). As you become more familiar with a staff member’s competency, trust builds, and staff need fewer instructions; but clarification of patients’ specific needs is always necessary.

Another important step in delegation is evaluation of the staff member’s performance, achievement of the patient’s outcomes, the communication process used, and any problems or concerns that occurred (NCSBN, 2005). When an NAP performs a task correctly and does a good job, it is important to provide praise and recognition. If the staff member’s performance is not satisfactory, give constructive and appropriate feedback. As a nurse, always give specific feedback regarding any mistakes that staff members make, explaining how to avoid the mistake or a better way to handle the situation. Giving feedback in private is the professional way and preserves the staff member’s dignity. When giving feedback, make sure to focus on things that can be changed, choose only one issue at a time, and give specific details. Frequently when the NAP’s performance does not meet expectations, it is the result of inadequate training or assignment of too many tasks. You discover the need to review a procedure with staff and offer demonstration or even recommend that additional training be scheduled with the education department. If too many tasks are being delegated, this might be a nursing practice issue. All staff need to discuss the appropriateness of delegation on their unit. Sometimes NAP need help in learning how to prioritize. In some cases you discover that you are overdelegating.

Once you delegate the task appropriately, it is important to monitor and supervise NAP in task performance. Clear directions and statement of desired outcomes increase the likelihood of successful completion of the task. If you observe a change in patient status, if the task is not being performed as directed or by agency policy and procedures, or if the NAP is having difficulty completing the task, you need to intervene and follow up as needed (ANA and NCSBN, 2005; NCSBN, 2005). It is your responsibility to complete documentation of the delegated task. Here are a few tips on appropriate delegation (Huston, 2009):

• Assess the knowledge and skills of the delegatee: Assess the knowledge and skills of the NAP by asking open-ended questions that elicit conversation and details about what he or she knows; for example, “How do you usually apply the cuff when you measure a blood pressure?” or “Tell me how you prepare the tubing before you give an enema.”

• Match tasks to the delegatee’s skills: Know which tasks and skills are in the scope of practice and job description for the team members to whom you delegate in your facility. Determine if personnel have learned critical thinking skills such as knowing when a patient is in harm or the difference between normal clinical findings and changes to report.

• Communicate clearly: Always provide clear directions by describing a task, the desired outcome, and the time period within which NAP need to complete the task. Never give instructions through another staff member. Make the person feel as though he or she is part of the team. Begin requests for help with please and end with thank you. For example, “I’d like you to please help me by getting Mr. Floyd up to ambulate before lunch. Be sure to check his blood pressure before he stands and write your finding on the graphic sheet. OK? Thanks.”

• Listen attentively: Listen to NAP’s response after you provide directions. Do they feel comfortable in asking questions or requesting clarification? If you encourage a response, listen to what the person has to say. Be especially attentive if the staff member has a deadline to meet for another nurse. Help sort out priorities.

• Provide feedback: Always give NAP feedback regarding performance, regardless of outcome. Let them know of a job well done. A thank you increases the likelihood of the NAP helping in the future. If an outcome is undesirable, find a private place to discuss what occurred, any miscommunication, and how to achieve a better outcome in the future.

Knowledge Building

As a professional nurse, recognize the importance of pursuing knowledge to remain competent. You need to maintain and improve your knowledge and skills. Lifelong learning is needed to be able to continuously provide safe, effective, quality care to patients (Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, 2008). A leader recognizes that there is always something new to learn. Opportunities for learning occur with each patient interaction, each encounter with a professional colleague, and each meeting or class session in which health care professionals meet to discuss clinical care issues. People always have different experiences and knowledge to share. Ongoing development of skills in delegation, communication, and teamwork helps maintain and build competency (Gravlin and Bittner, 2010). In-service programs, workshops, professional conferences, and collegiate courses offer innovative and current information on the rapidly changing world of health care. To become a leader, actively pursue learning opportunities, both formal and informal, and learn to share knowledge with the professional colleagues you encounter.

Key Points

• A manager sets a philosophy for a work unit, ensures appropriate staffing, mobilizes staff and institutional resources to achieve objectives, motivates staff members to carry out their work, sets standards of performance, and makes decisions to achieve objectives.

• Consideration communicates mutual trust, respect, and rapport between a manager and staff members.

• Empowering staff members brings out the best in a manager and allows him or her to concentrate on effective patient care systems, support risk taking and innovation, and focus on results and rewards.

• An empowered nursing staff has decision-making authority to change how they practice.

• Nursing care delivery models vary according to the responsibility and autonomy of the RN in coordinating care delivery and the roles other staff members play in assisting with care.

• Critical to the success of decision making is making staff members aware that they have the responsibility, authority, autonomy, and accountability for the care they give and the decisions they make.

• A nurse manager encourages decentralized decision making by establishing nursing practice committees, supporting nurse-physician and interdisciplinary collaboration, setting and implementing quality improvement plans, and maintaining timely staff communication.

• Clinical care coordination involves accurate clinical decision making, establishing priorities, efficient organizational skills, appropriate use of resources and time management skills, and an ongoing evaluation of care activities.

• In an enriched professional environment, each member of a nursing work team is responsible for open, professional communication.

• Effective delegation requires the use of good communication skills.

• When done correctly, delegation improves job efficiency, productivity, and job enrichment.

• An important responsibility for the nurse who delegates nursing care is evaluation of the staff member’s performance and patient outcomes.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

You are a staff nurse on a 32-bed cardiac step-down unit. The hospital obtained Magnet recognition last year. You are assigned as the preceptor for Tony, RN, who is a new graduate nurse, who just started his nursing career on your floor.

1. You and Tony just received morning shift report on your patients. You are assigned the following patients. Which patient do you and Tony need to see first? Explain your answer.

1. Mr. Dodson, a 52-year-old patient who was admitted yesterday with a diagnosis of angina pectoris. He is scheduled for a cardiac stress test at 0900.

2. Mrs. Wallace, a 60-year-old patient who was transferred out of intensive care at 0630 today. She had uncomplicated coronary artery bypass surgery yesterday.

3. Mr. Workman, a 45-year-old patient who experienced a myocardial infarction 2 days ago. He is complaining of chest pain rated as 6 on a scale of 0 to 10.

4. Mrs. Harris, a 76-year-old patient who had a permanent pacemaker inserted yesterday. She is complaining of incision pain rated as a 5 on a scale of 0 to 10.

2. As you work with Tony, you notice that he has trouble with organizational skills when providing patient care. What strategies will you suggest to Tony to help him improve in organizing his delivery of patient care?

3. Marianne, a NAP, is paired to work with you and Tony. You overhear Tony giving Marianne directions for what she needs to do. Tony says, “Marianne, in the next hour please assist Mrs. Harris in room 418 with her afternoon walk. She needs to walk 200 feet, which is from her room down the hall to the nurses’ station and back to her room. Take her pulse before and after she walks and record it in her chart. I’ll check with you when you’re finished to see how she did. Do you have any questions before you walk her? Thank you for your help.” Based on what you know about delegation, did Tony give appropriate or inappropriate directions to Marianne? Provide rationale for your answer.

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. After the 0700 shift report the registered nurse (RN) delegates three tasks to the nursing assistant. At 1300 the RN tells the nursing assistant that he would like to talk to her about the first task that was delegated, which was walking the patient, Mrs. Taylor, earlier that morning. The RN says, “You did a good job walking Mrs. Taylor by 0930. I saw that you recorded her pulse before and after the walk. I saw that Mrs. Taylor walked in the hallway barefoot. For safety, the next time you walk a patient, you need to make sure that the patient wears slippers or shoes. Please walk Mrs. Taylor again by 1500.” Which characteristics of good feedback did the RN use when talking to the nursing assistant? (Select all that apply.)

1. Feedback is given immediately.

2. Feedback focuses on one issue.

3. Feedback offers concrete details.

4. Feedback identifies ways to improve.

5. Feedback focuses on changeable things.

6. Feedback is specific about what is done incorrectly only.

2. As the nurse, you need to complete all of the following. Which task do you complete first?

1. Administer the oral pain medication to the patient who had surgery 3 days ago

2. Make a referral to the home care nurse for a patient who is being discharged in 2 days

3. Complete wound care for a patient with a wound drain that has an increased amount of drainage since last shift

4. Notify the health care provider of the decreased level of consciousness in the patient who had surgery 2 days ago

3. You are the charge nurse on a surgical unit. You are doing staff assignments for the 3-to-11 shift. Which patient do you assign to the licensed practical nurse (LPN)?

1. The patient who transferred out of intensive care an hour ago

2. The patient who requires teaching on new medications before discharge

3. The patient who had a vaginal hysterectomy 2 days ago and is being discharged tomorrow

4. The patient who is experiencing some bleeding problems following surgery earlier today

4. The type of care management approach that coordinates and links health care services to patients and their families while streamlining costs and maintaining quality is:

5. While administering medications, the nurse realizes that she has given the wrong dose of medication to a patient. She acts by completing an incident report and notifying the patient’s health care provider. The nurse is exercising:

6. Your nursing manager distributes biweekly newsletters of ongoing unit or health care agency activities and posts minutes of committee meetings on a bulletin board in the staff break room. This is an example of:

7. The nurse asks the nursing assistant to hold the legs of a female patient during a Foley catheter insertion. This is an example of a nurse displaying:

8. The nurse is assisting the patient with coughing and deep-breathing exercises following abdominal surgery. This is which priority nursing need for this patient?

9. The registered nurse (RN) checks on a patient who was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia. The patient is coughing profusely and requires nasotracheal suctioning. Orders include an intravenous (IV) infusion of antibiotics. The patient is febrile and asks the RN if he can have a bath because he has been perspiring profusely. Which task is appropriate to delegate to the nursing assistant?

10. Which task is appropriate for a registered nurse (RN) to delegate to the nursing assistant?

1. Explaining to the patient the preoperative preparation before the surgery in the morning

2. Administering the ordered antibiotic to the patient before surgery

3. Obtaining the patient’s signature on the surgical informed consent

4. Assisting the patient to the bathroom before leaving for the operating room

11. Which of the following strategies focus on improving nurse-physician collaborative practice? (Select all that apply.)

1. Inviting the physician to attend the practice council meeting

2. Participating in physician morning rounds

3. Placing physician photos and names in unit newsletter

4. Contacting physician promptly to discuss patient problems

5. Providing a list of physician contact numbers to all staff nurses

12. The nurses on the unit developed a system for self-scheduling of work shifts. This is an example of:

13. Which example demonstrates the nurse performing the skill of evaluation?

1. The nurse explains the side effects of the new blood pressure medication ordered for the patient.

2. The nurse asks the patient to rate pain on a scale of 0 to 10 before administering the pain medication.

3. After completing the teaching, the nurse observes the patient draw up and administer an insulin injection.

4. The nurse changes the patient’s leg ulcer dressing using aseptic technique.

14. The nurse is explaining the case management model to a group of nursing students. Which characteristics best describe the model? (Select all that apply.)

1. Case managers provide all patient care.

2. Multidisciplinary care plans are used.

3. Case managers coordinate discharge planning.

4. Staffing is expensive and may not decrease care costs.

5. Communication with health care team members is important.

15. The nurse collects the supplies for the dressing change for the patient in bed 1 and signs out the capillary blood glucose monitoring equipment to test the glucose of the patient in bed 2 before walking down the hall to the room. The nurse is displaying:

Answers: 1. 2, 3, 4, 5; 2. 4; 3. 3; 4. 4; 5. 3; 6. 1; 7. 2; 8. 3; 9. 4; 10. 4; 11. 1, 2, 4; 12. 2; 13. 3; 14. 2, 3, 5, 6; 15. 1.

References

American Nurses Association. Position statement on registered nurse utilization of assistive personnel. Am Nurse. 1995;25(2):7.

American Nurses Association (ANA), National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN). Joint statement on delegation. http://www.ncsbn.org/pdfs/Joint_statement.pdf, 2005.

American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC). Magnet Recognition Program. http://www.nursecredentialing.org/Magnet.aspx, 2010.

Anders, RL, Hawkins, JA. Mosby’s nursing leadership and management online. St Louis: Mosby; 2006.

Baker, DP, et al. Teamwork as an essential component of high-reliability organizations. Health Service Res. 2006;41(4):1576.

Batcheller, J, et al. A practice model for patient safety: the value of the experienced registered nurse. J Nurs Admin. 2004;34(4):200.

Benner, P, et al, Clinical reasoning, decision making, and action: thinking critically and clinically. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality AHRQ Pub No. 08-0043. Patient safety and quality: an evidence-based handbook for nurses. The Agency: Rockville, Md, 2008.

Carr, DD. Case managers optimize patient safety by facilitating effective care transitions. Prof Case Manage. 2007;12(2):70.

Case Management Society of America. What is a case manager? http://www.cmsa.org/Home/CMSA/whatisacasemanager/tabid/224/Default.aspx, 2010.

Cronenwett, L, et al. Quality and safety education for nurses. Nurs Outlook. 2007;55(3):122.

Gokenbach, V. Professional nurse councils: a new model to create excitement and improve value and productivity. J Nurs Admin. 2007;37(10):440.

Hackworth, T. Time management for the nurse leader. Nurs 2008 Crit Care. 2008;3(2):10.

Huston, CJ. 10 tips for successful delegation. Nursing. 2009;39(3):54.

Josiah, Macy, Jr. Foundation: Continuing education in the health professions: improving healthcare through lifelong learning. J Cont Educ Nurs. 2008;34(3):112.

Manojlovich, M, et al. Nursing practice and work environment issues in the 21st century. Nurs Res. 2008;57(1S):S11.

Marriner Tomey, A. Guide to nursing management and leadership, ed 8. St Louis: Mosby; 2009.

Nadzam, DM. Nurses’ role in communication and patient safety. J Nurs Care Qual. 2009;24(3):184.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN). Delegation: concepts and decision-making process. Chicago: The Council; 1995.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Working with others: a position paper. Chicago: The Council; 2005.

Pearce, C. Ten steps to managing time. Nurs Manage. 2007;14(1):23.

Seago, JA, Professional communication. Agency for Health Research and Quality AHRQ Pub No. 08-0043. Patient safety and quality: an evidence-based handbook for nurses. The Agency: Rockville, Md, 2008.

Tiedeman, ME, Lookinland, S. Traditional models of care delivery: what have we learned? J Nurs Admin. 2004;34(6):291.

Toofany, S. Critical thinking among nurses. Nurs Manage. 2008;14(9):28.

Upenieks, VV, Sitterding, M. Achieving Magnet redesignation: a framework for cultural change. J Nurs Admin. 2008;38(10):419.

Weston, MJ. Defining control over nursing practice and autonomy. J Nurs Admin. 2008;38(9):404.

Research References

Armstrong, K, et al. Workplace empowerment and Magnet hospital characteristics as predictors of patient safety climate. J Nurs Care Qual. 2009;24(1):55.

Berkow, S, et al. Fourteen unit attributes to guide staffing. J Nurs Admin. 2007;37(3):150.

Bittner, NP, Gravlin, G. Critical thinking, delegation, and missed care in nursing practice. J Nurs Admin. 2009;39(3):142.

Feltner, A, et al. Nurses’ views on the characteristics of an effective leader. AORN J. 2008;87(2):363.

Gravlin, G, Bittner, NP. Nurses’ and nursing assistants’ reports of missed care and delegation. J Nurs Admin. 2010;40(7/8):329.

Hendry, C, Walker, A. Priority setting in clinical nursing practice: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(4):427.

Hughes, LC, et al. Quality and strength of patient safety climate on medical-surgical units. Health Care Manage Rev. 2009;34(1):19.

Kearney, MH. Report of the findings from the post-entry competence study. Chicago: National Council of State Boards of Nursing; 2009.

Kramer, M, et al. Structures and practices enabling staff nurses to control their practice. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30(5):539.

Kramer, M, et al. Nine structures and leadership practices essential for a magnetic (healthy) work environment. Nurs Admin Q. 2010;34(1):4.

Lacey, SR, et al. Nursing support, workload, and intent to stay in Magnet, Magnet-aspiring, and non-Magnet hospitals. J Nurs Admin. 2007;37(4):199.

Lacey, SR, et al. Differences between pediatric registered nurses’ perception of organizational support, intent to stay, workload, and overall satisfaction, and years employed as a nurse in Magnet and non-Magnet pediatric hospitals: implications for administrators. Nurs Admin Q. 2009;33(1):6.

Potter, PA, et al. Delegation practices between registered nurses and nursing assistive personnel. J Nurs Manage. 2010;18:157.

Schmalenberg, C, Kramer, M. Clinical units with the healthiest work environments. Critical Care Nurse. 2008;28(3):65.

Thomas, PL. Case manager role definition: do they make an organizational impact? Prof Case Manage. 2008;13(2):61.

Ulrich, BT, et al. How RNs view the work environment: results of a national survey of registered nurses. J Nurs Admin. 2005;33(9):389.

Ulrich, BT, et al. Magnet status and registered nurse views of the work environment and nursing as a career. J Nurs Admin. 2009;39(7/8):S54.