Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice

• Describe characteristics of a critical thinker.

• Discuss the nurse’s responsibility in making clinical decisions.

• Discuss how reflection improves clinical decision making.

• Describe the components of a critical thinking model for clinical decision making.

• Discuss critical thinking skills used in nursing practice.

• Explain the relationship between clinical experience and critical thinking.

• Discuss the critical thinking attitudes used in clinical decision making.

• Explain how professional standards influence a nurse’s clinical decisions.

• Discuss the relationship of the nursing process to critical thinking.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Every day you think critically without realizing it. If it’s hot outside, you take off a sweater. If your DVD doesn’t start, you reposition the disc. If you decide to walk the dogs, you change to a pair of walking shoes. These examples involve critical thinking as you face each day and prepare for all possibilities. As a nurse, you will face many clinical situations involving patients, family members, health care staff, and peers. In each situation it is important to try to see the big picture and think smart. To think smart you have to develop critical thinking skills to face each new experience and problem involving a patient’s care with open-mindedness, creativity, confidence, and continual inquiry. When a patient develops a new set of symptoms, asks you to offer comfort, or requires a procedure, it is important to think critically and make sensible judgments so the patient receives the best nursing care possible. Critical thinking is not a simple step-by-step, linear process that you learn overnight. It is a process acquired only through experience, commitment, and an active curiosity toward learning.

Clinical Decisions in Nursing Practice

Nurses are responsible for making accurate and appropriate clinical decisions. Clinical decision making separates professional nurses from technical personnel. For example, a professional nurse observes for changes in patients, recognizes potential problems, identifies new problems as they arise, and takes immediate action when a patient’s clinical condition worsens. Technical personnel simply follow direction in completing aspects of care that the professional nurse has identified as necessary. A professional nurse relies on knowledge and experience when deciding if a patient is having complications that call for notification of a health care provider or decides if a teaching plan for a patient is ineffective and needs revision. Benner (1984) describes clinical decision making as judgment that includes critical and reflective thinking and action and application of scientific and practical logic. Most patients have health care problems for which there are no clear textbook solutions. Each patient’s problems are unique, a product of the patient’s physical health, lifestyle, culture, relationship with family and friends, living environment, and experiences. Thus as a nurse you do not always have a clear picture of a patient’s needs and the appropriate actions to take when first meeting a patient. Instead you must learn to question, wonder, and explore different perspectives and interpretations to find a solution that benefits the patient.

Because no two patients’ health problems are the same, you always apply critical thinking differently. Observe patients closely, gather information about them, examine ideas and inferences about patient problems, recognize the problems, consider scientific principles relating to the problems, and develop an approach to nursing care. With experience you learn to creatively seek new knowledge, act quickly when events change, and make quality decisions for patients’ well-being. You will find nursing to be rewarding and fulfilling through the clinical decisions you make.

Critical Thinking Defined

Mr. Jacobs is a 58-year-old patient who had a radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer yesterday. His nurse, Tonya, finds the patient lying supine in bed with arms extended along his sides but tensed. When Tonya checks the patient’s surgical wound and drainage device, she notes that the patient winces when she gently places her hands to palpate around the surgical incision. She asks Mr. Jacobs when he last turned onto his side, and he responds, “Not since last night some time.” Tonya asks Mr. Jacobs if he is having incisional pain, and he nods yes, saying, “It hurts too much to move.” Tonya considers the information she has observed and learned from the patient to determine that he is in pain and has reduced mobility because of it. She decides that she needs to take action to relieve Mr. Jacobs’ pain so she can turn him more frequently and begin to get him out of bed for his recovery.

In the case example the nurse observes the clinical situation, asks questions, considers what she knows about postoperative pain and risk for immobility, and takes action. The nurse applies critical thinking, a continuous process characterized by open-mindedness, continual inquiry, and perseverance, combined with a willingness to look at each unique patient situation and determine which identified assumptions are true and relevant (Heffner and Rudy, 2008). Critical thinking involves recognizing that an issue (e.g., patient problem) exists, analyzing information about the issue (e.g., clinical data about a patient), evaluating information (reviewing assumptions and evidence) and making conclusions (Settersten and Lauver, 2004). A critical thinker considers what is important in each clinical situation, imagines and explores alternatives, considers ethical principles, and makes informed decisions about the care of patients.

Critical thinking is a way of thinking about a situation that always asks “Why?”, “What am I missing?”, “What do I really know about this patient’s situation?”, and “What are my options?” (Heffner and Rudy, 2008; Paul and Heaslip, 1995). Tonya knew that pain was likely going to be a problem because the patient had extensive surgery. Her review of her observations and the patient’s report of pain confirmed her knowledge that pain was a problem. Her options include giving Mr. Jacobs an analgesic and waiting until it takes effect so she is able to reposition and make him more comfortable. Once he has less acute pain, Tonya offers to teach Mr. Jacobs some relaxation exercises.

You begin to learn critical thinking early in your practice. For example, as you learn about administering baths and other hygiene measures, take time to read your textbook and the nursing literature about the concept of comfort. What are the criteria for comfort? How do patients from other cultures perceive comfort? What are the many factors that promote comfort? The use of evidence-based knowledge, or knowledge based on research or clinical expertise, makes you an informed critical thinker. Thinking critically and learning about the concept of comfort prepares you to better anticipate your patients’ needs, identify comfort problems more quickly, and offer appropriate care. Critical thinking requires cognitive skills and the habit of asking questions, remaining well informed, being honest in facing personal biases, and always being willing to reconsider and think clearly about issues (Facione, 1990). When core critical thinking skills are applied to nursing, they show the complex nature of clinical decision making (Table 15-1). Being able to apply all of these skills takes practice. You also need to have a sound knowledge base and thoughtfully consider what you learn when caring for patients.

TABLE 15-1

| SKILL | NURSING PRACTICE APPLICATIONS |

| Interpretation | Be orderly in data collection. Look for patterns to categorize data (e.g., nursing diagnoses [see Chapter 17]). Clarify any data you are uncertain about. |

| Analysis | Be open-minded as you look at information about a patient. Do not make careless assumptions. Do the data reveal what you believe is true, or are there other options? |

| Inference | Look at the meaning and significance of findings. Are there relationships between findings? Do the data about the patient help you see that a problem exists? |

| Evaluation | Look at all situations objectively. Use criteria (e.g., expected outcomes, pain characteristics, learning objectives) to determine results of nursing actions. Reflect on your own behavior. |

| Explanation | Support your findings and conclusions. Use knowledge and experience to choose strategies to use in the care of patients. |

| Self-regulation | Reflect on your experiences. Identify the ways you can improve your own performance. What will make you believe that you have been successful? |

Modified from Facione P: Critical thinking: a statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. The Delphi report: research findings and recommendations prepared for the American Philosophical Association, ERIC Doc No. ED 315, Washington, DC, 1990, ERIC.

Nurses who apply critical thinking in their work are able to see the big picture from all possible perspectives. They focus clearly on options for solving problems and making decisions rather than quickly and carelessly forming quick solutions (Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor, 1994). Nurses who work in crisis situations such as the emergency department often act quickly when patient problems develop. However, even these nurses exercise discipline in decision making to avoid premature and inappropriate decisions. Learning to think critically helps you care for patients as their advocate, or supporter, and make better-informed choices about their care. Facione and Facione (1996) identified concepts for thinking critically (Table 15-2). Critical thinking is more than just problem solving. It is a continuous attempt to improve how to apply yourself when faced with problems in patient care.

TABLE 15-2

Concepts for a Critical Thinker

| CONCEPT | CRITICAL THINKING BEHAVIOR |

| Truth seeking | Seek the true meaning of a situation. Be courageous, honest, and objective about asking questions. |

| Open-mindedness | Be tolerant of different views; be sensitive to the possibility of your own prejudices; respect the right of others to have different opinions. |

| Analyticity | Analyze potentially problematic situations; anticipate possible results or consequences; value reason; use evidence-based knowledge. |

| Systematicity | Be organized, focused; work hard in any inquiry. |

| Self-confidence | Trust in your own reasoning processes. |

| Inquisitiveness | Be eager to acquire knowledge and learn explanations even when applications of the knowledge are not immediately clear. Value learning for learning’s sake. |

| Maturity | Multiple solutions are acceptable. Reflect on your own judgments; have cognitive maturity. |

Modified from Facione N, Facione P: Externalizing the critical thinking in knowledge development and clinical judgment, Nurs Outlook 44(3):129, 1996.

Thinking and Learning

Learning is a lifelong process. Your intellectual and emotional growth involves learning new knowledge and refining your ability to think, problem solve, and make judgments. To learn, you have to be flexible and always open to new information. The science of nursing is growing rapidly, and there will always be new information for you to apply in practice. As you have more clinical experiences and apply the knowledge you learn, you will become better at forming assumptions, presenting ideas, and making valid conclusions.

When you care for a patient, always think ahead and ask these questions: What is the patient’s status now? How might it change and why? Which physiological and emotional responses do I anticipate? What do I know to improve the patient’s condition? In which way will specific therapies affect the patient? What should be my first action? Do not let your thinking become routine or standardized. Instead, learn to look beyond the obvious in any clinical situation, explore the patient’s unique responses to health alterations, and recognize which actions are needed to benefit the patient. With experience you are able to recognize patterns of behavior, see commonalities in signs and symptoms, and anticipate reactions to therapies. Thinking about these experiences allows you to better anticipate each new patient’s needs and recognize problems when they develop.

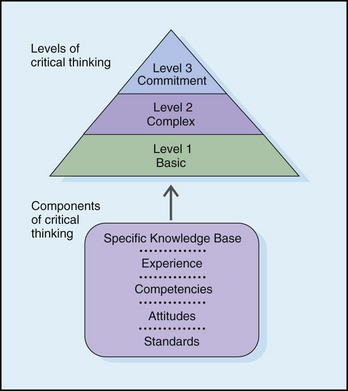

Levels of Critical Thinking in Nursing

Your ability to think critically grows as you gain new knowledge in nursing practice. Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor (1994) developed a critical thinking model (Fig. 15-1) that includes three levels: basic, complex, and commitment. An expert nurse thinks critically almost automatically. As a beginning student you make a more conscious effort to apply critical thinking because initially you are more task oriented and trying to learn how to organize nursing care activities. At first you apply the critical thinking model at the basic level. As you advance in practice, you adopt complex critical thinking and commitment.

FIG. 15-1 Critical thinking model for nursing judgment. (Redrawn from Kataoka-Yahiro M, Saylor C: A critical thinking model for nursing judgment, J Nurs Educ 33(8):351, 1994. Modified from Glaser E: An experiment in the development of critical thinking, New York, 1941, Bureau of Publications, Teachers College, Columbia University; Miller M, Malcolm N: Critical thinking in the nursing curriculum, Nurs Health Care 11:67, 1990; Paul RW: The art of redesigning instruction. In Willsen J, Blinker AJA, editors: Critical thinking: how to prepare students for a rapidly changing world, Santa Rosa, Calif, 1993, Foundation for Critical Thinking; and Perry W: Forms of intellectual and ethical development in the college years: a scheme, New York, 1979, Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.)

Basic Critical Thinking

At the basic level of critical thinking a learner trusts that experts have the right answers for every problem. Thinking is concrete and based on a set of rules or principles. For example, as a nursing student you use a hospital procedure manual to confirm how to insert a Foley catheter. You likely follow the procedure step by step without adjusting it to meet a patient’s unique needs (e.g., positioning to minimize the patient’s pain or mobility restrictions). You do not have enough experience to anticipate how to individualize the procedure. At this level answers to complex problems are either right or wrong (e.g., when no urine drains from the catheter, the catheter tip must not be in the bladder), and one right answer usually exists for each problem. Basic critical thinking is an early step in developing reasoning (Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor, 1994). A basic critical thinker learns to accept the diverse opinions and values of experts (e.g., instructors and staff nurse role models). However, inexperience, weak competencies, and inflexible attitudes can restrict a person’s ability to move to the next level of critical thinking.

Complex Critical Thinking

Complex critical thinkers begin to separate themselves from experts. They analyze and examine choices more independently. The person’s thinking abilities and initiative to look beyond expert opinion begin to change. A nurse learns that alternative and perhaps conflicting solutions exist.

Consider the case of Mr. Rosen, a 36-year-old man who had hip surgery. The patient is having pain but is refusing his ordered analgesic. His health care provider is concerned that the patient will not progress as planned, delaying rehabilitation. While discussing the importance of rehabilitation with Mr. Rosen, the nurse, Edwin, realizes the patient’s reason for not taking pain medication. Edwin learns that the patient practices meditation at home. As a complex critical thinker, Edwin recognizes that Mr. Rosen has options for pain relief. Edwin decides to discuss meditation and other nonpharmacological interventions with the patient as pain control options and how, when combined with analgesics, these interventions can potentially enhance pain relief.

In complex critical thinking each solution has benefits and risks that you weigh before making a final decision. There are options. Thinking becomes more creative and innovative. The complex critical thinker is willing to consider different options from routine procedures when complex situations develop. You learn a variety of different approaches for the same therapy.

Commitment

The third level of critical thinking is commitment (Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor, 1994). At this level a person anticipates when to make choices without assistance from others and accepts accountability for decisions made. As a nurse you do more than just consider the complex alternatives that a problem poses. At the commitment level you choose an action or belief based on the available alternatives and support it. Sometimes an action is to not act or to delay an action until a later time. You choose to delay as a result of your experience and knowledge. Because you take accountability for the decision, you consider the results of the decision and determine whether it was appropriate.

Critical Thinking Competencies

Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor (1994) describe critical thinking competencies as the cognitive processes a nurse uses to make judgments about the clinical care of patients. These include general critical thinking, specific critical thinking in clinical situations, and specific critical thinking in nursing. General critical thinking processes are not unique to nursing. They include the scientific method, problem solving, and decision making. Specific critical thinking competencies in clinical health care situations include diagnostic reasoning, clinical inference, and clinical decision making. The specific critical thinking competency in nursing involves use of the nursing process. Each of the competencies is discussed in the following paragraphs.

General Critical Thinking

The scientific method is a way to solve problems using reasoning. It is a systematic, ordered approach to gathering data and solving problems used by nurses, physicians, and a variety of other health care professionals. This approach looks for the truth or verifies that a set of facts agrees with reality. Nurse researchers use the scientific method when testing research questions in nursing practice situations (see Chapter 5). The scientific method has five steps:

Consider the following example of the scientific method in nursing practice.

A nurse caring for patients who receive large doses of chemotherapy for ovarian cancer sees a pattern of patients developing severe inflammation in the mouth (mucositis) (identifies problem). The nurse reads research articles (collects data) about mucositis and learns that there is evidence to show that having patients keep ice in their mouths (cryotherapy) during the chemotherapy infusion reduces severity of mucositis after treatment. He or she asks (forms question), “Do patients with ovarian cancer who receive chemotherapy have less severe mucositis when given cryotherapy versus standard mouth rinse in the oral cavity?” The nurse then collaborates with colleagues to develop a nursing protocol for using ice with certain chemotherapy infusions. The nurses on the oncology unit collect information that allows them to compare the incidence and severity of mucositis for a group of patients who use cryotherapy versus those who use standard-practice mouth rinse (tests the question). They analyze the results of their project and find that the use of cryotherapy reduced the frequency and severity of mucositis in their patients (evaluating the results). They decide to continue the protocol for all patients with ovarian cancer.

Problem Solving

You face problems every day such as a computer program that doesn’t function properly or a close friend who has lost a favorite pet. When a problem arises, you obtain information and use it, plus what you already know, to find a solution. Patients routinely present problems in practice. For example, a home care nurse learns that a patient has difficulty taking her medications regularly. The patient is unable to describe what medications she has taken for the last 3 days. The medication bottles are labeled and filled. The nurse has to solve the problem of why the patient is not adhering to or following her medication schedule. The nurse knows that the patient was discharged from the hospital and had five medications ordered. The patient tells the nurse that she also takes two over-the-counter medications regularly. When the nurse asks her to show the medications that she takes in the morning, the nurse notices that she has difficulty reading the medication labels. The patient is able to describe the medications that she is to take but is uncertain about the times of administration. The nurse recommends having the patient’s pharmacy relabel the medications in larger lettering. In addition, the nurse shows the patient examples of pill organizers that will help her sort her medications by time of day for a period of 7 days.

Effective problem solving also involves evaluating the solution over time to make sure that it is effective. It becomes necessary to try different options if a problem recurs. From the previous example, during a follow-up visit the nurse finds that the patient has organized her medications correctly and is able to read the labels without difficulty. The nurse obtained information that correctly clarified the cause of the patient’s problem and tested a solution that proved successful. Having solved a problem in one situation adds to a nurse’s experience in practice, and this allows the nurse to apply that knowledge in future patient situations.

Decision Making

When you face a problem or situation and need to choose a course of action from several options, you are making a decision. Decision making is a product of critical thinking that focuses on problem resolution. Following a set of criteria helps to make a thorough and thoughtful decision. The criteria may be personal; based on an organizational policy; or, frequently in the case of nursing, a professional standard. For example, decision making occurs when a person decides on the choice of a health care provider. To make a decision, an individual has to recognize and define the problem or situation (need for a certain type of health care provider to provide medical care) and assess all options (consider recommended health care providers or choose one whose office is close to home). The person has to weigh each option against a set of personal criteria (experience, friendliness, and reputation), test possible options (talk directly with the different health care providers), consider the consequences of the decision (examine pros and cons of selecting one health care provider over another), and make a final decision. Although the set of criteria follows a sequence of steps, decision making involves moving back and forth when considering all criteria. It leads to informed conclusions that are supported by evidence and reason. Examples of decision making in the clinical area include determining which patient care priority requires the first response, choosing a type of dressing for a patient with a surgical wound, or selecting the best teaching approach for a family caregiver who will assist a patient who is returning home after a stroke.

Specific Critical Thinking

Diagnostic Reasoning and Inference

Once you receive information about a patient in a clinical situation, diagnostic reasoning begins. It is the analytical process for determining a patient’s health problems (Harjai and Tiwari, 2009). Accurate recognition of a patient’s problems is necessary before you decide on solutions and implement action. It requires you to assign meaning to the behaviors and physical signs and symptoms presented by a patient. Diagnostic reasoning begins when you interact with a patient or make physical or behavioral observations. An expert nurse sees the context of a patient situation (e.g., a patient who is feeling light-headed with blurred vision and who has a history of diabetes is possibly experiencing a problem with blood glucose levels), observes patterns and themes (e.g., symptoms that include weakness, hunger, and visual disturbances suggest hypoglycemia), and makes decisions quickly (e.g., offers a food source containing glucose). The information a nurse collects and analyzes leads to a diagnosis of a patient’s condition. Nurses do not make medical diagnoses, but they do assess and monitor patients closely and compare the patients’ signs and symptoms with those that are common to a medical diagnosis. This type of diagnostic reasoning helps health care providers pinpoint the nature of a problem more quickly and select proper therapies.

Part of diagnostic reasoning is clinical inference, the process of drawing conclusions from related pieces of evidence and previous experience with the evidence. An inference involves forming patterns of information from data before making a diagnosis. Seeing that a patient has lost appetite and experienced weight loss over the last month, the nurse infers that there is a nutritional problem. An example of diagnostic reasoning is forming a nursing diagnosis such as imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements (see Chapter 17).

In diagnostic reasoning use patient data that you gather or collect to logically recognize the problem. For example, after turning a patient you see an area of redness on the right hip. You palpate the area and note that it is warm to the touch and the patient complains of tenderness. You press over the area with your finger; after you release pressure, the area does not blanch or turn white. After thinking about what you know about normal skin integrity and the effects of pressure, you form the diagnostic conclusion that the patient has a pressure ulcer. As a student, confirm your judgments with experienced nurses. At times you possibly will be wrong, but consulting with nurse experts gives you feedback to build on future clinical situations.

Often you cannot make a precise diagnosis during your first meeting with a patient. Sometimes you sense that a problem exists but do not have enough data to make a specific diagnosis. Some patients’ physical conditions limit their ability to tell you about symptoms. Some choose to not share sensitive and important information during your initial assessment. Some patients’ behaviors and physical responses become observable only under conditions not present during your initial assessment. When uncertain of a diagnosis, continue data collection. You have to critically analyze changing clinical situations until you are able to determine the patient’s unique situation. Diagnostic reasoning is a continuous behavior in nursing practice. Any diagnostic conclusions that you make will help the health care provider identify the nature of a problem more quickly and select appropriate medical therapies.

Clinical Decision Making

As in the case of general decision making, clinical decision making is a problem-solving activity that focuses on defining a problem and selecting an appropriate action. In clinical decision making a nurse identifies a patient’s problem and selects a nursing intervention. When you approach a clinical problem such as a patient who is less mobile and develops an area of redness over the hip, you make a decision that identifies the problem (impaired skin integrity in the form of a pressure ulcer) and choose the best nursing interventions (skin care and a turning schedule). Nurses make clinical decisions all the time to improve a patient’s health or maintain wellness. This means reducing the severity of the problem or resolving the problem completely. Clinical decision making requires careful reasoning (i.e., choosing the options for the best patient outcomes on the basis of the patient’s condition and the priority of the problem).

Improve your clinical decision making by knowing your patients. Nurse researchers found that expert nurses develop a level of knowing that leads to pattern recognition of patient symptoms and responses (White, 2003). For example, an expert nurse who has worked on a general surgery unit for many years is more likely able to detect signs of internal hemorrhage (e.g., fall in blood pressure, rapid pulse, change in consciousness) than a new nurse. Over time a combination of experience, time spent in a specific clinical area, and the quality of relationships formed with patients allow expert nurses to know clinical situations and quickly anticipate and select the right course of action. Spending more time during initial patient assessments to observe patient behavior and measure physical findings is a way to improve knowledge of your patients. In addition, consistently assessing and monitoring patients as problems occur help you to see how clinical changes develop over time. The selection of nursing therapies is built on both clinical knowledge and specific patient data, including:

• The identified status and situation you assessed about the patient, including data collected by actively listening to the patient regarding his or her health care needs.

• Knowledge about the clinical variables (e.g., age, seriousness of the problem, pathology of the problem, patient’s preexisting disease conditions) involved in the situation, and how the variables are linked together.

• A judgment about the likely course of events and outcome of the diagnosed problem, considering any health risks the patient has; includes knowledge about usual patterns of any diagnosed problem or prognosis.

• Any additional relevant data about requirements in the patient’s daily living, functional capacity, and social resources.

• Knowledge about the nursing therapy options available and the way in which specific interventions will predictably affect the patient’s situation.

Always keep the patient your center of focus as you try to solve his or her clinical problems. Making an accurate clinical decision allows you to set priorities for the interventions to implement first (see Chapter 18). Because different patients bring different variables to a situation, a certain activity is sometimes a higher priority in one situation and less of a priority in another. For example, if a patient is physically dependent, unable to eat, and incontinent of urine, you recognize skin integrity as a greater priority than if the patient was immobile but continent of urine and able to eat a normal diet. Do not assume that certain health situations produce automatic priorities. For example, a patient who has surgery is anticipated to experience a certain level of postoperative pain, which often becomes a priority for care. However, if the patient is experiencing severe anxiety that increases pain perception, it becomes necessary for you to focus on ways to relieve the anxiety before pain-relief measures will be effective.

Critical thinking and clinical decision making are complicated because nurses care for multiple patients in fast-paced and unpredictable environments. When you work in a busy setting, use criteria such as the clinical condition of the patient, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (see Chapter 6), the risks involved in treatment delays, and patients’ expectations of care to determine which patients have the greatest priorities for care. For example, a patient who is having a sudden drop in blood pressure along with a change in consciousness requires your attention immediately as opposed to a patient who needs you to collect a urine specimen or a patient who needs your help to walk down the hallway. Critical thinking allows a nurse to attend to the patient whose condition is changing quickly and delegate the specimen collection and ambulation to nursing assistive personnel (Box 15-1). For you to manage the wide variety of problems associated with groups of patients, skillful, prioritized clinical decision making is critical (Box 15-2).

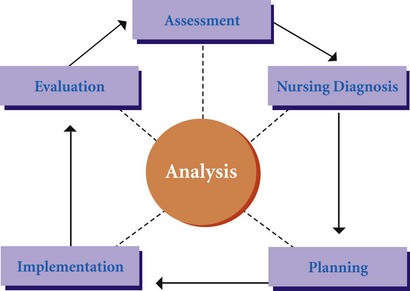

Nursing Process as a Competency

Nurses apply the nursing process as a competency when delivering patient care (Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor, 1994). The nursing process is a five-step clinical decision-making approach: assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation. The purpose of the nursing process is to diagnose and treat human responses to actual or potential health problems (American Nurses Association, 2010). Human responses include patient symptoms and physiological reactions to treatment, the need for knowledge when health care providers make a new diagnosis or treatment plan, and a patient’s ability to cope with loss. Use of the process allows nurses to help patients meet agreed-on outcomes for better health (Fig. 15-2). The nursing process requires a nurse to use the general and specific critical thinking competencies described earlier to focus on a particular patient’s unique needs. The format for the nursing process is unique to the discipline of nursing and provides a common language and process for nurses to “think through” patients’ clinical problems (Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor, 1994). Unit 3 describes the nursing process.

The nursing process allows for flexibility for use in all clinical settings. When using it, identify a patient’s health care needs by collecting thorough information and clearly defining all nursing diagnoses or collaborative problems. You plan care by determining priorities, setting goals and expected outcomes of care, and collaborating with family and health care team members. Then you deliver nursing interventions competently and evaluate the effects of your care. When you become more competent in using the nursing process, you will be able to focus not only on a single patient problem or diagnosis but on multiple problems and diagnoses. As a nurse, always be thinking and recognizing what step of the process you are using. Within each step you apply critical thinking to provide the very best professional care to your patients.

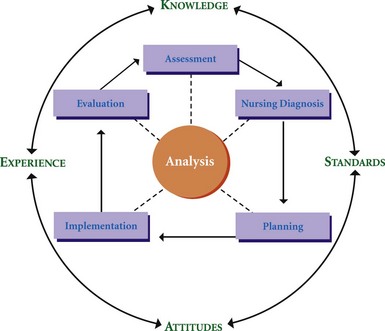

A Critical Thinking Model for Clinical Decision Making

Thinking critically is at the core of professional nursing competence. The ability to think critically, improve clinical practice, and decrease errors in clinical judgments is the vision of nursing practice (Di Vito-Thomas, 2005). This text offers a model to help you develop critical thinking. Models help to explain concepts. Because critical thinking in nursing is complex, a model explains what is involved as you make clinical decisions and judgments about your patients. Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor (1994) developed a model of critical thinking for nursing judgment based in part on previous work by a number of nurse scholars and researchers (Paul, 1993; Miller and Malcolm, 1990) (see Fig. 15-1). The model defines the outcome of critical thinking: nursing judgment that is relevant to nursing problems in a variety of settings. According to this model, there are five components of critical thinking: knowledge base, experience, critical thinking competencies (with emphasis on the nursing process), attitudes, and standards. The elements of the model combine to explain how nurses make clinical judgments that are necessary for safe, effective nursing care (see Box 15-2). Throughout this text the model shows you how to apply critical thinking as part of the nursing process. Graphic illustration of the critical thinking model in our clinical chapters shows you how to apply elements of critical thinking in assessing patients, planning the interventions you provide, and evaluating the results. If you learn to apply each element of this model in the way you think about patients, you will become a confident and effective professional.

Specific Knowledge Base

The first component of the critical thinking model is a nurse’s specific knowledge base. Knowledge prepares you to better anticipate and identify patients’ problems by understanding their origin and nature. Nurses’ knowledge varies according to educational experience and includes basic nursing education, continuing education courses, and additional college degrees. In addition, it includes the initiative you show in reading the nursing literature to remain current in nursing science. A nurse’s knowledge base is continually changing as science progresses (Swinny, 2010). As a nurse your knowledge base includes information and theory from the basic sciences, humanities, behavioral sciences, and nursing. Nurses use their knowledge base in a different way than other health care disciplines because they think holistically about patient problems. For example, a nurse’s broad knowledge base offers a physical, psychological, social, moral, ethical, and cultural view of patients and their health care needs. The depth and extent of knowledge influence your ability to think critically about nursing problems.

Consider this scenario: Robert Perez previously earned a bachelor’s degree in education and taught high school for 1 year. He is starting his third year of study in his nursing program. He has successfully completed the required courses in the sciences, health ethics, introduction to nursing concepts, and communication principles. His first clinical course is on health promotion with a clinical assignment at a general medical clinic. Although he is still new to nursing, his experiences as a teacher and his preparation and knowledge base in nursing help him know how to interview patients and begin to make clinical decisions about patients’ health promotion practices.

Experience

Nursing is a practice discipline. Clinical learning experiences are necessary to acquire clinical decision-making skills. Swinny (2010) explains that knowledge itself is not necessarily related to the development of critical thinking. Instead knowledge combined with clinical expertise from experience defines critical thinking. In clinical situations you learn from observing, sensing, talking with patients and families, and reflecting actively on all experiences. Clinical experience is the laboratory for testing your nursing knowledge. You learn that “textbook” approaches form the basis for practice, but you make safe adaptations or revisions in approaches to fit the setting, the patient’s unique qualities, and the experiences you have from caring for previous patients. With experience you begin to understand clinical situations, recognize cues of patients’ health patterns, and interpret cues as relevant or irrelevant. Perhaps the best lesson a new nursing student can learn is to value all patient experiences, which become stepping-stones for building new knowledge and inspiring innovative thinking.

During the previous summer Robert worked as a nurse assistant in a nursing home. This experience provided valuable time for interacting with older-adult patients and giving basic nursing care. As Robert thinks about his clinical experience at the clinic, he recognizes that he still has a lot to learn. However, each patient has provided him valuable learning experiences. Specifically he has developed good interviewing skills, understands the importance of the family in an individual’s health, and has learned how nurses are patient advocates. He has also learned that older adults need more time to perform activities such as eating, bathing, and grooming; therefore he has adapted these skill techniques. His time in the physical assessment laboratory and the time he worked in the nursing home have helped him begin to be a watchful observer. Finally Robert’s previous experience as a teacher helps him apply educational principles in his nursing role.

Your practice improves from what you learn personally. The opportunities you have to experience different emotions, crises, and successes in your lives and relationships with others build your experience as a nurse.

The Nursing Process Competency

Competency, specifically the nursing process, is the third component of the critical thinking model. In your practice you apply critical thinking components during each step of the nursing process. Throughout the clinical chapters of this text, the relationship of critical thinking to the nursing process is emphasized.

Attitudes for Critical Thinking

The fourth component of the critical thinking model is attitudes. Eleven attitudes define the central features of a critical thinker and how a successful critical thinker approaches a problem (Paul, 1993) (Box 15-3). For example, when a patient complains of anxiety before a diagnostic procedure, the curious nurse explores possible reasons for the patient’s concerns. The nurse shows discipline in collecting a thorough assessment to find the source of the patient’s anxiety. Attitudes of inquiry involve an ability to recognize that problems exist and that there is a need for evidence to support the truth in what you think is true. Critical thinking attitudes are guidelines for how to approach a problem or decision-making situation. An important part of critical thinking is interpreting, evaluating, and making judgments about the adequacy of various arguments and available data. Knowing when you need more information, knowing when information is misleading, and recognizing your own knowledge limits are examples of how critical thinking attitudes guide decision making. Table 15-3 summarizes the use of critical thinking attitudes in nursing practice.

TABLE 15-3

Critical Thinking Attitudes and Applications in Nursing Practice

| CRITICAL THINKING ATTITUDE | APPLICATION IN PRACTICE |

| Confidence | Learn how to introduce yourself to a patient; speak with conviction when you begin a treatment or procedure. Do not lead a patient to think that you are unable to perform care safely. Always be well prepared before performing a nursing activity. Encourage a patient to ask questions. |

| Thinking independently | Read the nursing literature, especially when there are different views on the same subject. Talk with other nurses and share ideas about nursing interventions. |

| Fairness | Listen to both sides in any discussion. If a patient or family member complains about a co-worker, listen to the story and then speak with the co-worker as well. If a staff member labels a patient uncooperative, assume the care of that patient with openness and a desire to meet that patient’s needs. |

| Responsibility and authority | Ask for help if you are uncertain about how to perform a nursing skill. Refer to a policy and procedure manual to review steps of a skill. Report any problems immediately. Follow standards of practice in your care. |

| Risk taking | If your knowledge causes you to question a health care provider’s order, do so. Be willing to recommend alternative approaches to nursing care when colleagues are having little success with patients. |

| Discipline | Be thorough in whatever you do. Use known scientific and practice-based criteria for activities such as assessment and evaluation. Take time to be thorough and manage your time effectively. |

| Perseverance | Be cautious of an easy answer. If co-workers give you information about a patient and some fact seems to be missing, clarify the information or talk to the patient directly. If problems of the same type continue to occur on a nursing division, bring co-workers together, look for a pattern, and find a solution. |

| Creativity | Look for different approaches if interventions are not working for a patient. For example, a patient in pain may need a different positioning or distraction technique. When appropriate, involve the patient’s family in adapting your approaches to care methods used at home. |

| Curiosity | Always ask why. A clinical sign or symptom often indicates a variety of problems. Explore and learn more about the patient so as to make appropriate clinical judgments. |

| Integrity | Recognize when your opinions conflict with those of a patient; review your position, and decide how best to proceed to reach outcomes that will satisfy everyone. Do not compromise nursing standards or honesty in delivering nursing care. |

| Humility | Recognize when you need more information to make a decision. When you are new to a clinical division, ask for an orientation to the area. Ask registered nurses (RNs) regularly assigned to the area for assistance with approaches to care. |

Confidence

When you are confident, you feel certain about accomplishing a task or goal such as performing a procedure or making a diagnostic decision. Confidence grows with experience in recognizing your strengths and limitations. You shift your focus from your own needs (e.g., remembering how to perform a procedure) to the patient’s needs. When you are not confident in performing a nursing skill, you become anxious about not knowing what to do. This prevents you from giving attention to the patient. Always be aware of what you know and what you do not know. If you have a question about a procedure, discuss it with your nursing instructor first before attempting it on your patient. Never attempt anything on your patient unless you have the knowledge base and feel confident. Patient safety is of the upmost importance. When you show confidence, your patients recognize it by how you communicate and the way you perform nursing care. Confidence builds trust between you and your patients.

Thinking Independently

As you gain new knowledge, you learn to consider a wide range of ideas and concepts before forming an opinion or making a judgment. This does not mean that you ignore other people’s ideas. Instead you learn to consider all sides of a situation. However, a critical thinker does not accept another person’s ideas without question. When thinking independently, you challenge the ways others think and look for rational and logical answers to problems. Begin to raise important questions about your practice. For example, why is one type of surgical dressing ordered over another, why do your patients not get pain relief, and what can you do to help patients with literacy problems learn about their medications? When nurses ask questions and look for the evidence behind clinical problems, they are thinking independently; this is an important step in evidence-based practice (Chapter 5). Independent thinking and reasoning are essential to the improvement and expansion of nursing practice.

Fairness

A critical thinker deals with situations justly. This means that bias or prejudice does not enter into a decision. For example, regardless of how you feel about obesity, you do not allow personal attitudes to influence the way you care for a patient who is overweight. Look at a situation objectively and consider all viewpoints to understand the situation completely before making a decision. Having a sense of imagination helps you develop an attitude of fairness. Imagining what it is like to be in your patient’s situation helps you see it with new eyes and appreciate its complexity.

Responsibility and Accountability

When caring for patients you are responsible for correctly performing nursing care activities based on standards of practice. Standards of practice are the minimum level of performance accepted to ensure high-quality care. For example, you do not take shortcuts (e.g., failing to identify a patient, prepare medication doses for multiple patients at the same time) when administering medications. A professional nurse is competent in performing nursing therapies and making clinical decisions about patients. As a nurse you are answerable or accountable for your decisions and the outcomes of your actions. This means that you are accountable for recognizing when nursing care is ineffective and you know the limits and scope of your practice

Risk Taking

Persons often associate taking risks with danger. Driving 30 miles an hour over the speed limit is a risk that sometimes results in injury to the driver and an unlucky pedestrian. But risk taking does not always have negative outcomes. Risk taking is desirable, particularly when the result is a positive outcome. A critical thinker is willing to take risks in trying different ways to solve problems. The willingness to take risks comes from experience with similar problems. Risk taking often leads to advances in patient care. Nurses in the past have taken risks in trying different approaches to skin and wound care and pain management, to name a few. When taking a risk, consider all options; follow safety guidelines; analyze any potential dangers to a patient; and act in a well-reasoned, logical, and thoughtful manner.

Discipline

A disciplined thinker misses few details and follows an orderly or systematic approach when collecting information, making decisions, or taking action. For example, you have a patient who is in pain. Instead of only asking the patient, “How severe is your pain on a scale of 0 to 10?” you also ask more specific questions about the character of pain. For example, “What makes the pain worse? Where does it hurt? How long have you noticed it?” Being disciplined helps you identify problems more accurately and select the most appropriate interventions.

Perseverance

A critical thinker is determined to find effective solutions to patient care problems. This is especially important when problems remain unresolved or recur. Learn as much as possible about a problem and try various approaches to care. Persevering means to keep looking for more resources until you find a successful approach. For example, a patient who is unable to speak following throat surgery poses challenges for the nurse to be able to communicate effectively. Perseverance leads the nurse to try different communication approaches (e.g., message boards or alarm bells) until he or she finds a method that the patient is able to use. A critical thinker who perseveres is not satisfied with minimal effort but works to achieve the highest level of quality care.

Creativity

Creativity involves original thinking. This means that you find solutions outside of the standard routines of care while still keeping standards of practice. Creativity motivates you to think of options and unique approaches. A patient’s clinical problems, social support systems, and living environment are just a few examples of factors that make the simplest nursing procedure more complicated. For example, a home care nurse has to find a way to help an older patient with arthritis have greater mobility in the home. The patient has difficulty lowering and raising herself in a chair because of pain and limited range of motion in her knees. The nurse uses wooden blocks to elevate the chair legs so the patient is able to sit and stand with little discomfort while making sure the chair is safe to use.

Curiosity

A critical thinker’s favorite question is “Why?” In any clinical situation you learn a great deal of information about a patient. As you analyze patient information, data patterns appear that are not always clear. Having a sense of curiosity motivates you to inquire further (e.g., question family, consult with a physician, or review the scientific literature) and investigate a clinical situation so you get all the information you need to make a decision.

Integrity

Critical thinkers question and test their own knowledge and beliefs. Your personal integrity as a nurse builds trust from your co-workers. Nurses face many dilemmas or problems in everyday clinical practice, and everyone makes mistakes at times. A person of integrity is honest and willing to admit to mistakes or inconsistencies in his or her own behavior, ideas, and beliefs. In addition, the professional nurse always tries to follow the highest standards of practice.

Humility

It is important for you to admit to any limitations in your knowledge and skill. Critical thinkers admit what they do not know and try to find the knowledge needed to make proper decisions. It is common for a nurse to be an expert in one area of clinical practice but a novice in another. That is because the knowledge in all areas of nursing is unlimited. A patient’s safety and welfare are at risk if you do not admit your inability to deal with a practice problem. You have to rethink a situation; learn more; and use the new information to form opinions, draw conclusions, and take action.

The first patient Robert meets in the clinic is a young man who has signs and symptoms of chlamydia, a sexually transmitted disease. The patient has had the symptoms for over 3 weeks and voices concern about what it means to have the disease. Robert examines the young man and finds that the patient has redness and itching on the penis with a yellowish discharge. He uses discipline to check further and asks if the patient has pain on urination. He also checks him for fever. Robert has limited knowledge about chlamydia, so he consults with the clinic nurse practitioner, who explains the nature of the infection, the risks it poses to the patient, and the usual course of treatment. Robert returns and speaks more confidently with the patient about chlamydia, the reason for his symptoms, the need to tell sex partners about the infection, and the importance of wearing a condom.

Standards for Critical Thinking

The fifth component of the critical thinking model includes intellectual and professional standards (Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor, 1994).

Intellectual Standards

Paul (1993) identified 14 intellectual standards (see Box 15-3) universal for critical thinking. An intellectual standard is a guideline or principle for rational thought. You apply these standards when you use the nursing process. When you consider a patient problem, apply the intellectual standards such as preciseness, accuracy, and consistency to make sure that all clinical decisions are sound. A thorough use of the intellectual standards in clinical practice makes certain that you do not perform critical thinking haphazardly.

Mrs. Lamar is an 82-year-old patient who comes to the medical clinic for a follow-up following the diagnosis of a diabetic foot ulcer. Robert finds the ulcer on the patient’s left foot. A quick check of the patient’s medical record reveals a description of the ulcer by one of the clinic nurses from 2 weeks earlier. The patient is receiving a topical medication for the ulcer. Robert uses the same assessment criteria applied during the last clinic visit to examine the patient’s ulcer (consistent). He methodically inspects the affected area of the skin, measures the size of the ulcer, and notes the appearance of any drainage (complete). He asks the patient to describe how she has been caring for the ulcer to determine if she needs health teaching (relevant). When the patient explains that she washes the ulcer, Robert asks her to describe exactly what she has used to clean the ulcer and how often (precise). He documents the wound location and appearance in the clinic record using specific anatomical terms (accurate). By applying appropriate intellectual standards, Robert is able to determine that the ulcer is healing and has improved since the last assessment.

Professional Standards

Professional standards for critical thinking refer to ethical criteria for nursing judgments, evidence-based criteria used for evaluation, and criteria for professional responsibility (Paul, 1993). Application of professional standards requires you to use critical thinking for the good of individuals or groups (Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor, 1994). Professional standards promote the highest level of quality nursing care.

Excellent nursing practice is a reflection of ethical standards (Chapter 22). Patient care requires more than just the application of scientific knowledge. Being able to focus on a patient’s values and beliefs helps you make clinical decisions that are just, faithful to the patient’s choices, and beneficial to the patient’s well-being. Critical thinkers maintain a sense of self-awareness through conscious awareness of their beliefs; values; feelings; and the multiple perspectives that patients, family members, and peers present in clinical situations. Critical thinking also requires the use of evidence-based criteria for making clinical judgments. These criteria are sometimes scientifically based on research findings (see Chapter 5) or practice based on standards developed by clinical experts and performance improvement initiatives of the institution. Examples are the clinical practice guidelines developed by individual clinical agencies and national organizations such as the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality (AHRQ). A clinical practice guideline includes standards for the treatment of select clinical conditions such as stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pressure ulcers. Another example is clinical criteria used to categorize clinical conditions such as the criteria for staging pressure ulcers (see Chapter 48) and rating phlebitis (see Chapter 41). Evidence-based evaluation criteria set the minimum requirements necessary to ensure appropriate and high-quality care.

Nurses routinely use evidence-based criteria to assess patients’ conditions and determine the efficacy of nursing interventions. For example, accurate assessment of symptoms such as pain includes use of assessment criteria such as the duration, severity, location, aggravating or relieving factors, and effects on daily lifestyle (see Chapter 43). In this case assessment criteria allow you to accurately determine the nature of a patient’s symptoms, select appropriate therapies, and evaluate if the therapies are effective. The standards of professional responsibility that a nurse tries to achieve are the standards cited in Nurse Practice Acts, institutional practice guidelines, and professional organizations’ standards of practice (e.g., The American Nurses Association Standards of Professional Performance (see Chapter 1). These standards “raise the bar” for the responsibilities and accountabilities that a nurse assumes in guaranteeing quality health care to the public.

Developing Critical Thinking Skills

To develop critical thinking skills, it is important to learn how to connect knowledge and theory with practice. Your ability to make sense of what you learn in the classroom, from reading, or from having dialogue with other students and then to apply it during patient care is always challenging.

Reflective Journaling

How often do you think back on a situation to consider the following: Why did that occur? How did I act? What could I have done differently? What knowledge could I have applied? Reflection is the process of purposefully thinking back or recalling a situation to discover its purpose or meaning. It is like rewinding a videotape. Reflection involves playing back a situation in your head and taking time to honestly review everything you remember about it. Reflective practice is a conscious process of thinking, analyzing, and learning from your work situations by way of journaling or regularly meeting with colleagues to explore work situations and self-evaluate (Cirocco, 2007). Critical thinking becomes more deliberate through reflection because it allows you to think about your previous thinking to make your future thinking better (Jackson, 2006).

Reflective journal writing is a tool for developing critical thought and reflection by clarifying concepts. Reflective writing gives you the opportunity to define and express the clinical experience in your own words (Di Vito-Thomas, 2005). By keeping a journal of each of your clinical experiences, you are able to explore personal perceptions or understanding of each experience and develop the ability to apply theory in practice. The use of a journal improves your observation and descriptive skills. Writing skills also improve through the development of conceptual clarity. The Circle of Meaning model adapted to nursing encourages concept clarification and a search for meaning in nursing practice (Bilinski, 2002). The model uses the following questions to help you journey through a clinical experience and find meaning:

1. Which experience, situation, or information in your clinical experience seems confusing, difficult, or interesting?

2. What is the meaning of the experience? What feelings did you have? What feelings did your patient have? What influenced the experience? Which guesses or questions developed with the first connection in question 1? Give examples.

3. Do the feelings, guesses, or questions remind you of any experience from the past or present or something that you think is a desirable future experience? How does it relate? What are the implications/significance?

4. What are the connections between what is being described and what you have learned about nursing science, research, and theory? What are some possible solutions? Which approach or solution would you choose and why? How is this approach effective?

Keeping a journal of your patient care experiences helps you become aware of how you make clinical decisions. Begin by recording notes after a clinical experience. Telling a story and drawing a picture are two additional ways to identify the experience on which you wish to reflect. Describe in detail what you felt, thought, and did. Analyze the experience by considering feelings, thoughts, and possible meaning. Challenge any preconceived ideas you have when you look at actual clinical situations. Describe the significance of the experience. Do not include patient identification in your journal, and refer to your journal when you care for patients in similar situations.

Meeting with Colleagues

Another way to develop critical thinking skills is regularly meeting with colleagues to discuss and examine work experiences. Having the chance to discuss anticipated and unanticipated outcomes in any clinical situation allows you to continually learn and develop your expertise and knowledge (Cirocco, 2007). When nurses have a formal means to discuss their experiences such as a staff meeting or unit practice council, the dialogue allows for questions, differing viewpoints, and sharing experiences. When they are able to discuss their practices, the process validates good practice and also offers challenges and constructive criticism. Much can be learned by drawing from others’ experiences and perspectives to promote reflective critical thinking.

Concept Mapping

As a nurse you care for patients who have multiple nursing diagnoses or collaborative problems. A concept map is a visual representation of patient problems and interventions that shows their relationships to one another. It offers a nonlinear picture of a patient that can then be used for comprehensive care planning (Taylor and Wros, 2007). The primary purpose of concept mapping is to better synthesize relevant data about a patient, including assessment data, nursing diagnoses, health needs, nursing interventions, and evaluation measures (Hill, 2006). Through drawing a concept map, you learn to organize or connect information in a unique way so the diverse information that you have about a patient begins to form meaningful patterns and concepts. You begin to see a more holistic view of a patient. When you see the relationship between the various patient diagnoses and the data that support them, you better understand a patient’s clinical situation. Concept maps become more detailed, integrated, and comprehensive as you learn more about the care of a patient and the care you provide similar patients (Ferrario, 2004). The similarities and differences that you see among patients build your decision-making skills. Unit 3 includes chapters that provide diagrams of actual concept maps and more detail on their development. Concept maps can also be found in Units 5 and 6.

Critical Thinking Synthesis

Critical thinking is a reasoning process by which you reflect on and analyze your own thoughts, actions, and knowledge. To be a good critical thinker requires dedication and a desire to grow intellectually. As a beginning nurse it is important to learn the steps of the nursing process and incorporate the elements of critical thinking (Fig. 15-3). The two processes go hand in hand in making quality decisions about patient care. This text provides a model to show you how important critical thinking is in nursing practice. Throughout the clinical chapters of this text, the components of critical thinking are emphasized to help you better understand their relationship to the nursing process.

Key Points

• Clinical decision making involves judgment that includes critical and reflective thinking and action and application of scientific and practical logic.

• Nurses who apply critical thinking in their work focus on options for solving problems and making decisions rather than rapidly and carelessly forming quick, single solutions.

• Following a procedure step by step without adjusting to a patient’s unique needs is an example of basic critical thinking.

• In complex critical thinking a nurse learns that alternative and perhaps conflicting solutions exist.

• In diagnostic reasoning you collect patient data and analyze them to determine the patient’s problems.

• The nursing process is a blueprint for patient care that involves both general and specific critical thinking competencies in a way that focuses on a particular patient’s unique needs.

• The critical thinking model combines a nurse’s knowledge base, experience, competence in the nursing process, attitudes, and standards to explain how nurses make clinical judgments that are necessary for safe, effective nursing care.

• Clinical learning experiences are necessary for you to acquire clinical decision-making skills.

• Critical thinking attitudes help you to know when more information is necessary and when it is misleading and to recognize your own knowledge limits.

• The use of intellectual standards during assessment ensures that you obtain a complete database of information.

• Professional standards for critical thinking refer to ethical criteria for nursing judgments, evidence-based criteria for evaluation, and criteria for professional responsibility.

• Meeting regularly with colleagues allows you to discuss anticipated and unanticipated outcomes in any clinical situation to continually learn and develop your expertise and knowledge.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

Josh is a second-year nursing student working in a surgical clinic. He is checking Mr. Isaac’s surgical wound. After removing the gauze dressing, he notes in the nurses’ notes from the last visit that the wound was 3 cm long and the skin around the wound was tender when palpated. When Josh examines the wound, he measures the length and width in centimeters with a tape measure, observes the character of the tissues, looks for drainage, and palpates around the wound for tenderness and an increase in drainage. He asks Mr. Isaac if he is having discomfort from the wound and if the pain is limiting his activity.

1. Explain which intellectual standards Josh used in the wound assessment and support your answers.

2. Mr. Isaac asks Josh if the wound is going to heal soon, stating, “I thought it would have healed by now.” Josh responds by saying, “What did your doctor tell you about the time it would take to heal the wound? I plan to talk with him to let him know how the wound looks so we’re sure we’re using the right type of dressing.” In this example Josh is displaying which of the following attitudes for critical thinking during his communication:

3. Two weeks later Mr. Isaac again comes to the clinic. The wound has not progressed, but there are no signs of infection. Josh talks with Mr. Isaac about his activities. He also has Mr. Isaac describe the type of diet he has been eating and the amount of food intake. Josh’s line of questioning is an example of which critical thinking competency? Explain.

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. While assessing a patient, the nurse observes that the patient’s intravenous (IV) line is not infusing at the ordered rate. The nurse assesses the patient for pain at the IV site, checks the flow regulator on the tubing, looks to see if the patient is lying on the tubing, checks the point of connection between the tubing and the IV catheter, and then checks the condition of the site where the intravenous catheter enters the patient’s skin. After the nurse readjusts the flow rate, the infusion begins at the correct rate. This is an example of:

2. The nurse sits down to talk with a patient who lost her sister 2 weeks ago. The patient reports she is unable to sleep, feels very fatigued during the day, and is having trouble at work. The nurse asks her to clarify the type of trouble. The patient explains she can’t concentrate or even solve simple problems. The nurse records the results of the assessment, describing the patient as having ineffective coping. This is an example of:

3. A patient on a surgical unit develops sudden shortness of breath and a drop in blood pressure. The staff respond, but the patient dies 30 minutes later. The manager on the nursing unit calls the staff involved in the emergency response together. The staff discusses what occurred over the 30-minute time frame, the actions taken, and whether other steps should have been implemented. The nurses in this situation are:

4. A nurse has worked on an oncology unit for 3 years. One patient has become visibly weaker and states, “I feel funny.” The nurse knows how patients often have behavior changes before developing sepsis when they have cancer. The nurse asks the patient questions to assess thinking skills and notices the patient shivering. The nurse goes to the phone, calls the physician, and begins the conversation by saying, “I believe that your patient is developing sepsis. I want to report symptoms I’m seeing.” What examples of critical thinking concepts does the nurse show? (Select all that apply.)

5. A nurse who is working on a surgical unit is caring for four different patients. Patient A will be discharged home and is in need of instruction about wound care. Patients B and C have returned from the operating room within an hour of each other, and both require vital signs and monitoring of their intravenous (IV) lines. Patient D is resting following a visit by physical therapy. Which of the following activities by the nurse represent(s) use of clinical decision making for groups of patients? (Select all that apply.)

1. Consider how to involve patient A in deciding whether to involve the family caregiver in wound care instruction.

2. Think about past experience with patients who develop postoperative complications.

3. Decide which activities can be combined for patients B and C.

4. Carefully gather any assessment information and identify patient problems.

6. The surgical unit has initiated the use of a pain-rating scale to assess patients’ pain severity during their postoperative recovery. The registered nurse (RN) looks at the pain flow sheet to see the pain scores recorded for a patient over the last 24 hours. Use of the pain scale is an example of which intellectual standard?

7. During a home health visit the nurse prepares to instruct a patient in how to perform range-of-motion (ROM) exercises for an injured shoulder. The nurse verifies that the patient took an analgesic 30 minutes before arrival at the patient’s home. After discussing the purpose for the exercises and demonstrating each one, the nurse has the patient perform them. After two attempts with only the second of three exercises, the patient stops and says, “This hurts too much. I don’t see why I have to do this so many times.” The nurse applies the critical thinking attitude of integrity in which of the following actions?”

1. “I understand your reluctance, but the exercises are necessary for you to regain function in your shoulder. Let’s go a bit more slowly and try to relax.”

2. “I see that you’re uncomfortable. I’ll call your doctor to decide the next step.”

3. “Show me exactly where your pain is and rate it for me on a scale of 0 to 10.”

4. “Is anything else bothering you? Other than the pain, is there any other reason you might not want to do the exercises?”

8. The nurse cared for a 14-year-old with renal failure who died near the end of the work shift. The health care team tried for 45 minutes to resuscitate the child with no success. The family was devastated by the loss, and, when the nurse tried to talk with them, the mother said, “You can’t make me feel better; you don’t know what it’s like to lose a child.” Which of the following examples of journal entries might best help the nurse reflect and think about this clinical experience? (Select all that apply.)

1. Data entry of time of day, who was present, and condition of the child

2. Description of the efforts to restore the child’s blood pressure, what was used, and questions about the child’s response

3. The meaning the experience had for the nurse with respect to her understanding of dealing with a patient’s death

4. A description of what the nurse said to the mother, the mother’s response, and how the nurse might approach the situation differently in the future

9. A nurse has been working on a surgical unit for 3 weeks. A patient requires a Foley catheter to be inserted, so the nurse reads the procedure manual for the institution to review how to insert it. The level of critical thinking the nurse is using is:

10. A patient had hip surgery 16 hours ago. During the previous shift the patient had 40 mL of drainage in the surgical drainage collection device for an 8-hour period. The nurse refers to the written plan of care, noting that the health care provider is to be notified when drainage in the device exceeds 100 mL for the day. On entering the room, the nurse looks at the device and carefully notes the amount of drainage currently in it. This is an example of:

11. A 67-year-old patient will be discharged from the hospital in the morning. The health care provider has ordered three new medications for her. Place the following steps of the nursing process in the correct order.

____ 1. The nurse returns to the patient’s room and asks her to describe the medicines she will be taking at home.

____ 2. The nurse talks with the patient and family about who will be available if the patient has difficulty taking medicines and considers consulting with the health care provider about a home health visit.

____ 3. The nurse asks the patient if she is in pain, feels tired, and is willing to spend the next few minutes learning about her new medicines.

____ 4. The nurse brings the containers of medicines and information leaflets to the bedside and discusses each medication with her.

____ 5. The nurse considers what she learns from the patient and identifies the patient’s nursing diagnosis.

12. The nurse asks a patient how she feels about her impending surgery for breast cancer. Before the discussion the nurse reviewed the description of loss and grief and therapeutic communication principles in his textbook. The critical thinking component involved in the nurse’s review of the literature is:

13. A nurse is working with a nursing assistive personnel (NAP) on a busy oncology unit. The nurse has instructed the NAP on the tasks that need to be performed, including getting patient A out of bed, collecting a urine specimen from patient B, and checking vital signs on patient C, who is scheduled to go home. Which of the following represent(s) successful delegation? (Select all that apply.)

1. A nurse explains to the NAP the approach to use in getting the patient up and why the patient has activity limitations.

2. A nurse is asked by a patient to help her to the bathroom; the nurse leaves the room and directs the NAP to assist the patient instead.

3. The nurse sees the NAP preparing to help a patient out of bed, goes to assist, and thanks the NAP for her efforts to get the patient up early.

4. The nurse is in patient B’s room to check an intravenous (IV) line and collects the urine specimen while in the room.

5. The nurse offers support to the NAP when needed but allows her to complete patient care tasks without constant oversight.

14. Which of the following is unique to the commitment level of critical thinking?

1. Weighs benefits and risks when making a decision.

2. Analyzes and examine choices more independently.

4. Anticipates when to make choices without others’ assistance.

15. In which of the following examples is the nurse not applying critical thinking skills in practice?

1. The nurse considers personnel experience in performing intravenous (IV) line insertion and ways to improve performance.

2. The nurse uses a fall risk inventory scale to determine a patient’s fall risk.

3. The nurse observes a change in a patient’s behavior and considers which problem is likely developing.

4. The nurse explains the procedure for giving a tube feeding to a second nurse who has floated to the unit to assist with care.

Answers: 1. 4; 2. 1; 3. 3; 4. 3, 4; 5. 1, 3; 6. 3; 7. 1; 8. 2, 3, 4; 9. 3; 10. 2; 11. The correct order is 3 (assessment), 5 (nursing diagnosis), 2 (planning), 4 (intervention), 1 (evaluation); 12. 3; 13. 1, 3, 4; 14. 4; 15. 4.

References

American Nurses Association. Nursing’s social policy statement: the essence of the profession. Washington, DC: The Association; 2010.

Benner, P. From novice to expert: excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley; 1984.

Bilinski, H. The mentored journal. Nurs Educ. 2002;27(1):37.

Facione, N, Facione, P. Externalizing the critical thinking in knowledge development and clinical judgment. Nurs Outlook. 1996;44:129.

Ferrario, CG. Developing nurses’ critical thinking skills with concept mapping. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2004;20(6):261.

Harjai, PK, Tiwari, R. Model of critical diagnostic reasoning: achieving expert clinician performance. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2009;30(5):305.

Heffner, S, Rudy, S. Critical thinking: what does it mean in the care of elderly hospitalized patients? Crit Care Nurs Q. 2008;31(1):73.

Hill, C. Integrating clinical experiences into the concept mapping process. Nurse Educ. 2006;31(1):36.

Jackson, M. Defining the concept of critical thinking. In: Jackson M, Ignatavicius DD, Case B, eds. Conversations in critical thinking and clinical judgment, American Association of Critical Care Nurses. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett, 2006.