Nursing Assessment

• Discuss the relationship between critical thinking and nursing assessment.

• Explain the process of data collection.

• Differentiate between subjective and objective data.

• Describe the methods of data collection.

• Discuss the process of conducting a patient-centered interview.

• Describe the components of a nursing history.

• Explain the differences among comprehensive, problem-oriented, and focused assessments.

• Explain the relationship between data interpretation and validation.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

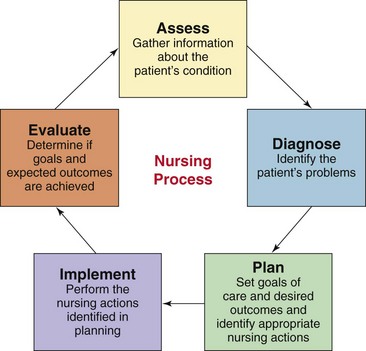

The nursing process is a critical thinking process that professional nurses use to apply the best available evidence to caregiving and promoting human functions and responses to health and illness (American Nurses Association, 2010). It is the fundamental blueprint for how to care for patients. The nursing process is also a standard of practice, which, when followed correctly, protects nurses against legal problems related to nursing care (Austin, 2008). As a nursing student, you learn the five steps of the nursing process—assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation—as if they were a linear process (Fig. 16-1). However, in fact the nursing process is dynamic and continuous; and, after more experience in practice, you learn to move back and forth among the various steps (Potter et al., 2005). Consider the following scenario that was also described in Chapter 15:

Mr. Jacobs is a 58-year-old patient who had a radical prostatectomy (removal of prostate gland) for prostate cancer yesterday. He is married to Martha, who has been at his bedside most of the morning. His nurse, Tonya Moore, just started the day shift on the surgical unit and finds the patient lying flat in bed with arms tensed and extended along his sides. When Tonya checks the surgical wound and drainage device, she notes that Mr. Jacobs winces when she gently places her hands to palpate around the incisional area. She asks Mr. Jacobs when he last turned onto his side, and he responds, “Not since last night some time.” Tonya asks Mr. Jacobs if he is having incisional pain, and he nods yes, saying, “It hurts too much to move.” Tonya clarifies, “On a scale of 0 to 10 with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain you have ever had, rate how you feel now.” Mr. Jacobs states, “Oh, this is at least a 7.” Tonya considers the information she has observed and learned from Mr. Jacobs to determine that he is in pain and has reduced mobility because of it. She decides that she needs to take action to relieve Mr. Jacobs’ pain so she can turn him more frequently and begin to get him out of bed for his recovery.

Each time you meet a patient, you apply the nursing process, as Tonya did while caring for Mr. Jacobs, to provide appropriate and effective nursing care. The process begins with the first step, assessment, the gathering and analysis of information about the patient’s health status. You then make clinical judgments from the assessment to identify the patient’s response to health problems in the form of nursing diagnoses. Once you define appropriate nursing diagnoses, you create a plan of care. Planning includes setting goals and expected outcomes for your care and selecting interventions (nursing and collaborative) individualized to each of the patient’s nursing diagnoses. The next step, implementation, involves performing the planned interventions. After performing interventions, you evaluate the patient’s response and whether the interventions were effective. The nursing process is central to your ability to provide timely and appropriate care to your patients.

The nursing process is a variation of scientific reasoning. Practicing the five steps of the nursing process allows you to be organized and conduct your practice in a systematic way. You learn to make inferences about the meaning of a patient’s response to a health problem or generalize about the patient’s functional state of health. Through assessment a pattern begins to form. For example, if Mr. Jacobs is having incisional pain, the data allow Tonya to infer that his mobility is limited. Tonya gathers more information (e.g., palpating gently over the incision, having Mr. Jacobs rate the severity of discomfort, and noting that he limits movement) until an accurate classification of the patient’s problem is determined such as the following nursing diagnosis: acute pain related to trauma of incision and the diagnosis of impaired physical mobility related to incisional pain. Clearly defining your patients’ problems provides the basis for planning and implementing nursing interventions and evaluating the outcomes of care.

Critical Thinking Approach to Assessment

Assessment is the deliberate and systematic collection of information about a patient to determine his or her current and past health and functional status and his or her present and past coping patterns (Carpenito-Moyet, 2009). Nursing assessment includes two steps:

1. Collection of information from a primary source (the patient) and secondary sources (e.g., family members, health professionals, and medical record)

2. The interpretation and validation of data to ensure a complete database

The purpose of assessment is to establish a database about the patient’s perceived needs, health problems, and responses to these problems. In addition, the data reveal related experiences, health practices, goals, values, and expectations about the health care system.

When a plumber comes to your home to repair a problem you describe as a “leaking faucet,” the plumber checks the faucet, its attachments to the water line, and the water pressure in the system to determine the real problem. A patient presents an initial health problem to you. For example, Mr. Jacobs presents with signs of pain following surgery. You then proceed to observe his behaviors, ask questions about the nature of the problem, listen to the cues he provides, and conduct a physical examination (see Chapter 30). You also usually interview family members who are familiar with the patient’s health problems and any existing medical record data. The data you collect fall into different sets or patterns of information that point to a diagnostic conclusion. Once a plumber knows the source of the leaking faucet, he is able to repair it. Once you know the nature and source of a patient’s specific health problems (such as Mr. Jacob’s incisional pain), you are able to provide interventions that will restore, maintain, or improve the patient’s health.

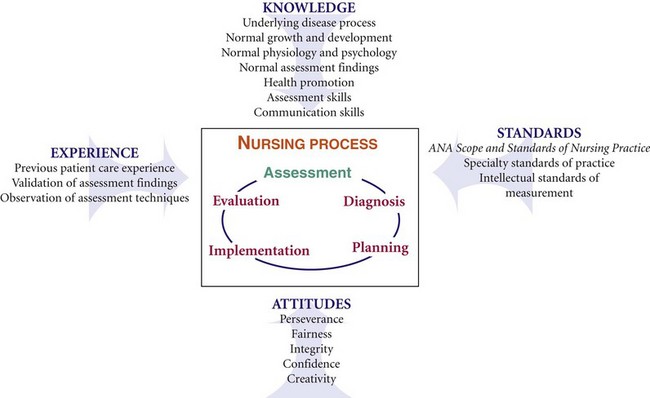

Critical thinking is a vital part of assessment (see Chapter 15). It allows you to see the big picture when you form conclusions or make decisions about a patient’s health condition. While gathering data about a patient, you synthesize relevant knowledge, recall prior clinical experiences, apply critical thinking standards and attitudes, and use standards of practice to direct your assessment in a meaningful and purposeful way (Fig. 16-2). Your knowledge from the physical, biological, and social sciences allows you to ask relevant questions and collect relevant history and physical assessment data related to the patient’s presenting health care needs. For example, Tonya knows that Mr. Jacobs had his prostate gland removed. She reviewed her medical-surgical textbook and learned that a radical prostatectomy involves removal of a lot of tissue, including the prostate gland, seminal vesicles, part of the bladder neck, and lymph nodes. This knowledge helps her to recognize that considerable swelling can potentially create acute pain; thus she decides to inspect and palpate around Mr. Jacob’s incisional area. She also questions Mr. Jacobs about how the discomfort affects his ability to turn or move in bed. Using good communication skills through interviewing and applying critical thinking intellectual standards (such as being precise and accurate in using a pain scale) enables Tonya to collect complete, accurate, and relevant data.

Prior clinical experience contributes to the skills of assessment. For example, Tonya cared for a patient with surgical incision pain in the past and knows that pain is often disabling and limits a patient’s normal motion. This experience allows Tonya to thoroughly assess the extent to which pain affects the patient’s ability to move and eventually get out of bed, an important step in Mr. Jacob’s recovery. Validation of any abnormal assessment findings and personal observation of assessments performed by skilled professionals help you become competent in assessment. You also learn to apply standards of practice and accepted standards of “normal” for physical assessment data when assessing patients. Use of critical thinking attitudes such as curiosity, perseverance, and confidence ensure you complete a comprehensive database.

Data Collection

You perform assessment to gather information needed to make an accurate judgment about a patient’s current condition (Magnan and Maklebust, 2009). Your information comes from:

• The patient, through interview, observations, and physical examination.

• Family members or significant others’ reports and response to interviews.

• Other members of the health care team.

• Medical record information (e.g., patient history, laboratory work, x-ray film results, multidisciplinary consultations).

• Scientific literature (evidence about assessment techniques and standards).

As you begin a patient assessment, think critically about what to assess for that specific patient. Determine which questions or measurements are appropriate based on your clinical knowledge and experience and your patient’s health history and responses. When you first meet a patient, perform a quick screening. Usually your screening is based on a treatment situation. For example, a community health nurse assesses the patient’s neighborhood and community; an emergency department nurse uses the ABC (airway-breathing-circulation) approach; and a surgical nurse focuses on the patient’s symptoms following surgery, the expected healing response, and potential complications. For Mr. Jacobs, Tonya first focuses on the nature and severity of his pain, the risk of limited postoperative mobility, and the possibility that the wound is infected. She later expands her assessment to determine how Mr. Jacobs is adjusting emotionally to his surgery.

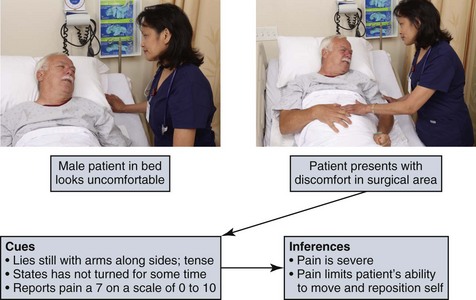

You learn to differentiate important data from the total data collected. A cue is information that you obtain through use of the senses. An inference is your judgment or interpretation of these cues (Fig. 16-3). For example, a patient crying is a cue that possibly implies fear or sadness. You ask the patient about any concerns and make known any nonverbal expressions you notice in an effort to direct the patient to share his or her feelings. It is possible to miss important cues when you conduct an initial overview. However, always try to interpret cues from the patient to know how in depth to make your assessment. Remember, thinking is human and imperfect. You acquire appropriate thinking processes when conducting assessments but expect to make mistakes in missing important cues (Lunney, 2006). Assessment is dynamic and allows you to freely explore relevant patient problems as you discover them.

After your observational screening, focus on the assessment cues and patterns of information that suggest problem areas. There are two approaches to a comprehensive assessment. One involves use of a structured database format, based on an accepted theoretical framework or practice standard. Gordon’s model of 11 functional health patterns (1994) (Box 16-1) is an example. The theory or practice standard provides categories of information for you to assess. Gordon’s functional health patterns model offers a holistic framework for assessment of any health problem. Tonya plans to direct her assessment of Mr. Jacobs to the cognitive-perceptual pattern to learn more about what the patient knows about the surgery and his prognosis and how he prefers to learn and make decisions about his care. Tonya is anticipating his need for education about postoperative recovery. She also plans to assess his sexuality-reproductive pattern to determine how he is accepting the potential change in sexual function resulting from surgery. A theoretical or standard-based assessment provides for a comprehensive review of a patient’s health care problems.

An assessment moves from the general to the specific. For example, you assess all of Gordon’s 11 functional health patterns and then determine if patterns or problems appear in your data. You then ask more focused questions about the health patterns that suggest a problem exists. You organize patterns of behavior and physiological responses that relate to a functional health category. The complete assessment of the 11 functional health patterns represents the interaction of the patient and the environment, which Gordon calls biopsychosocial integration. According to Gordon (1994), you cannot understand one health pattern without knowledge of the other patterns. Ultimately your assessment identifies functional patterns (patient strengths) and dysfunctional patterns (nursing diagnoses) that help you develop the nursing care plan.

The second approach for conducting a comprehensive assessment is the problem-oriented approach. You focus on the patient’s presenting situation and begin with problematic areas such as incisional pain or limited understanding of postoperative recovery. You ask the patient follow-up questions to clarify and expand your assessment so you can understand the full nature of the problem. Later your physical examination further confirms your observations. Tonya’s assessment of Mr. Jacobs ensures that she knows the type of pain he is having and the extent to which it limits his activities. Table 16-1 offers an example of a problem-focused assessment. Once you complete the assessment, thoroughly analyze the extent and nature of a patient’s problem so you are able to later develop a care plan.

TABLE 16-1

Example of Problem-Focused Patient Assessment: Pain

| PROBLEM AND ASSOCIATED FACTORS | QUESTIONS | PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT |

| Nature of pain | Describe your pain for me. Place your hand over the area that hurts or is uncomfortable. |

Observe nonverbal cues. Observe where patient points to pain; note if it radiates or is localized. |

| Precipitating factors | Do you notice if pain worsens during any activities or specific time of day? Is pain associated with movement? |

Observe if patient demonstrates nonverbal signs of pain during movement, positioning, swallowing. |

| Severity | Rate your pain on a scale of 0 to 10. | Inspect area of discomfort; palpate for tenderness. |

Whatever approach you use to collect data, you begin to cluster cues, make inferences, and identify emerging patterns and potential problem areas. To do this well you critically anticipate, which means that you try to stay a step ahead of the assessment. Think about what the data tell you. Remember to always have supporting cues before you make an inference. Your inferences direct you to further questions. Once you ask a patient a question or make an observation, patterns form, and the information branches to an additional series of questions or observations (Fig. 16-4). Knowing how to probe and frame questions is a skill that grows with experience. You learn to decide which questions are relevant to a situation and to attend to accurate interpretations of data.

Types of Data

There are two primary sources of data: subjective and objective. Subjective data are your patients’ verbal descriptions of their health problems. Only patients provide subjective data. For example, Mr. Jacobs’s report of incision pain and his expression of concern about whether the pain means that he will not be able to go home as soon as he hoped are subjective findings. Subjective data usually include feelings, perceptions, and self-report of symptoms. Only patients provide subjective data relevant to their health condition. The data sometimes reflect physiological changes, which you further explore through objective data collection.

Objective data are observations or measurements of a patient’s health status. Inspecting the condition of a surgical incision or wound, describing an observed behavior, and measuring blood pressure are examples of objective data. The measurement of objective data is based on an accepted standard such as the Fahrenheit or Celsius measure on a thermometer, inches or centimeters on a measuring tape, or known characteristics of behaviors (e.g., anxiety or fear). When you collect objective data, apply critical thinking intellectual standards (e.g., clear, precise, and consistent) so you can correctly interpret your findings.

Sources of Data

As a nurse you obtain data from a variety of sources that provide information about the patient’s current level of wellness and functional status, anticipated prognosis, risk factors, health practices and goals, responses to previous treatment, and patterns of health and illness.

Patient: A patient is usually your best source of information. Patients who are conscious, alert, and able to answer questions correctly provide the most accurate information about their health care needs, lifestyle patterns, present and past illnesses, perception of symptoms, responses to treatment, and changes in activities of daily living. Always consider the setting for your assessment and your patient’s condition. A patient experiencing acute symptoms in an emergency department will not offer as much information as one who comes to an outpatient clinic for a routine checkup. An older adult requires more time than someone younger, and often multiple visits are required to gather a complete database (Seidel et al., 2011) (Box 16-2). Always be attentive and show a caring presence with patients (see Chapter 7). Let a patient know you are interested in what he or she has to say. Patients are less likely to fully reveal the nature of their health care problems when nurses show little interest or are easily distracted by activities around them.

Family and Significant Others: Family members and significant others are primary sources of information for infants or children; critically ill adults; and patients who are mentally handicapped, disoriented, or unconscious. In cases of severe illness or emergency situations, families are often the only sources of information for nurses and other health care providers. The family and significant others are also important secondary sources of information. They confirm findings that a patient provides (e.g., whether he takes medications regularly at home or how well he sleeps or eats). Include the family when appropriate. Remember, a patient does not always want you to question or involve the family. You must obtain a patient’s agreement to include family members or friends. Often spouses or close friends sit in during an assessment and provide their view of the patient’s health problems or needs. Not only do they supply information about the patient’s current health status, but they are also able to tell when changes in the patient’s status occurred. Family members are often very well informed because of their experiences living with the patient and observing how health problems affect daily living activities. Family and friends make important observations about the patient’s needs that can affect the way care is delivered (e.g., how a patient eats a meal or how he or she makes choices).

Health Care Team: You frequently communicate with other health care team members in gathering information about patients. In the acute care setting the change-of-shift report is how nurses from one shift communicate information to nurses on the next shift (see Chapter 26). During the report you have the chance to collect the first set of information about patients assigned to your care. Researchers found that bedside rounds, also called bedside handover, promote patient-centered care (Chaboyer, McMurray, and Wallis, 2010). During bedside rounds, the nurse who is completing care for a shift, the patient, and the nurse assuming care for a shift share information about the patient’s condition, status of problems, and treatment plan for the next shift. In some settings other health care team members participate in the rounds. When nurses, physicians, physical therapists, social workers, or other staff consult on a patient’s condition, they share information about how the patient is interacting within the health care environment, the patient’s reactions to treatment, and the result of diagnostic procedures or therapies. Every member of the team is a source of information for identifying and verifying information about the patient.

Medical Records: The medical record is a source for the patient’s medical history, laboratory and diagnostic test results, current physical findings, and the primary health care provider’s treatment plan. The record is a valuable tool for checking the consistency and similarities of your personal observations. Data in the records offer a baseline and ongoing information about the patient’s response to illness and progress to date. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 has a privacy rule that came into effect on April 14, 2003 to set standards for the protection of health information (USDHHS, 2003). Information in a patient’s record is confidential. Each health care agency has policies governing how the patient’s health information can be shared among health care providers (see Chapter 26). It is important to know organization policies for reviewing a patient’s medical record for the purpose of assessment.

Other Records and the Scientific Literature: Educational, military, and employment records sometimes contain significant health care information (e.g., immunizations). If a patient received services at a community health center or different hospital, you need written permission from the patient or guardian to access the records. The HIPAA regulations protect access to patients’ health information. The privacy rule allows health care providers to share protected information as long as they use reasonable safeguards. Check the policy of your agency for HIPAA guidelines.

Reviewing nursing, medical, and pharmacological literature about a patient’s illness completes your assessment database. This review increases your knowledge about the patient’s diagnosed problems, expected symptoms, treatment, prognosis, and established standards of therapeutic practice. The scientific literature offers evidence to direct you on how and why to conduct assessments for particular patient conditions. A knowledgeable nurse obtains relevant, accurate, and complete information for the assessment database.

Nurse’s Experience: Through clinical experience a nurse observes other patients; recognizes clinical changes; and learns the types of questions to ask, choosing only the questions that will give the most useful information. A nurse’s expertise develops after testing and refining inferences, questions, and principle- or standard-based expectations. For example, while caring for Mr. Jacobs, Tonya has learned what a prostatectomy incision looks like and how a patient responds to the associated discomfort. In the future Tonya will more quickly recognize the behavior of a patient in acute pain and how it affects normal mobility. Practical experience and the opportunity to make clinical decisions strengthen your critical thinking.

Methods of Data Collection

As a nurse you use patient-centered interviews, the nursing health history, physical examination, and results of laboratory and diagnostic tests to collect data for a patient’s assessment database.

Patient-Centered Interview

A patient-centered interview is an approach for obtaining from patients the data that are needed to foster a caring nurse-patient relationship, adherence to interventions, and treatment effectiveness (Smith et al., 2006). The interview technique is the basis of a conceptual model used by nurse practitioners to form long-term therapeutic relationships with patients (Lein and Wills, 2007). However, the model has aspects that are useful to all nurses when conducting interviews for patient assessment. The partnership that forms in a patient-centered interview empowers a patient, promotes mutual decision making with the nurse, and ensures continuity of care (Dontje et al., 2004).

The expectation in a busy acute care setting such as a hospital nursing unit or clinic is for nurses to complete in a limited amount of time a patient history and nursing assessment. In the home health setting there is usually more time and fewer distractions; this allows a nurse to conduct a thorough interview. Agencies set standards for the type of information to be collected in health histories. However, there is a risk that standard assessments do not capture the patient’s full story. In a patient-centered interview an organized conversation with the patient allows the patient to set the initial focus and initiate discussion about his or her chief problems or reasons for seeking health care (Lein and Wills, 2007).

A successful interview requires preparation. Collect available information about the patient before starting the interview. For example, review the information you learn during a change-of-shift report and then plan to interview the hospitalized patient as you make patient rounds and before you begin to provide ordered interventions. Create a favorable environment for the interview. A good interview environment is free of distractions, unnecessary noise, and interruptions. The patient is more likely to be open and honest if the interview is private (i.e., out of earshot of other patients, visitors, or staff). Timing is important in avoiding interruptions. If possible, set aside a 10- to 15-minute period when no other activities are planned. More time is even better but is difficult to plan when you have multiple patients. During the interview always observe your patient for signs of discomfort or fatigue and plan accordingly. Remember to let a patient decide whether to involve the family in the interview. After an initial interview, follow-up discussions allow you to learn more about a patient’s situation and focus on specific problem areas. An initial patient-centered interview involves: (1) setting the stage, (2) gathering information about the patient’s chief concerns or problems and setting an agenda, (3) collecting the assessment or a nursing health history, and (4) terminating the interview.

Setting the Stage: Greet the patient using his or her full name, introduce yourself and explain your role (if it is the first time you have met), and remove any barriers to privacy by closing a room curtain or shutting a door. This is the orientation phase of an interview. When you explain the reason for collecting a health history, also assure the patient that any information obtained remains confidential and is used only by health care professionals who provide his or her care. HIPAA regulations require patients to sign an authorization before you collect personal health data (USDHHS, 2003). Refer to your agency policy for the authorization process.

After giving Mr. Jacobs pain medication for his incisional pain, Tonya waits 30 minutes and decides to take the time to assess Mr. Jacobs more fully. She reviews the surgical summary in the chart and the last set of nurses’ notes and enters the patient’s room.

Tonya: Mr. Jacobs, I am Tonya Moore. I did not fully introduce myself earlier when you looked so uncomfortable. You look a bit more comfortable now. Can you rate your pain again for me on a scale of 0 to 10?”

Mr. Jacobs: “Yes, I think the medicine has helped. I would rate the pain a 4.”

Tonya: “Good. If you’re comfortable, I’d like to spend about 10 minutes to better understand what you know about your surgery and discuss it with you. Everything you share will be confidential between you and the persons providing your care. I will let nurses on the next shift know about your care.”

Set an Agenda: You begin an interview by gathering information about the patient’s current chief concerns or problems and setting an agenda. Remember, the best clinical interview focuses on the patient, not your agenda. Let the patient know your purpose (such as collecting an assessment or a nursing history) and ask the patient for his or her list of concerns or problems. This is the time that allows the patient to feel comfortable speaking with you and become an active partner in decisions about care. The professionalism and the competence that you show when interviewing patients strengthens the nurse-patient relationship.

Tonya: “I’m going to ask you questions about what you know about your surgery and what you need to do once you go home. But first tell me your main concerns.”

Mr. Jacobs: “Concerns, you mean about the surgery?”

Tonya: “Yes, or any other health problems you would like to discuss.”

Mr. Jacobs: “Well, I hope they got all of the cancer. I want to do what I need to do to get out of here as soon as I can.”

Tonya: “Ok, Is there anything else?”

Mr. Jacobs: “I’m worried about my wife and me. My doctor told me that the surgery could change our ability to have sex.”

Tonya: “Ok, your doctor will talk to you about your tumor. Don’t be afraid to ask him questions. Which changes concern you?

Mr. Jacobs: “Well I worry that, you know, I may not be able to have intercourse.”

Tonya: “It’s true; that is a risk of surgery. It’s important to learn from the doctor whether there was any nerve injury during surgery. It’s something you need to ask him. And we can discuss it further when you know the results. Now let me ask you about your expectations after surgery so we can have a teaching plan for you. Does that sound reasonable?”

Mr. Jacobs: “Yes, I’m not sure what to expect before I get out of here.”

Collect the Assessment or Nursing Health History: Start an assessment or a health history with open-ended questions that allow patients to describe more clearly their concerns and problems. For example, you can begin by having the patient explain symptoms or physical concerns, describe what he or she knows about the health problem, or ask him or her to describe health care expectations. Use attentive listening and other therapeutic communication techniques (see Chapter 24) that encourage a patient to tell his or her story. Observe verbal cues the patient expresses. Stay focused and orderly and do not rush. An initial interview (e.g., the one you conduct to collect a complete nursing history) is more extensive. You gather information about the patient’s concerns and then complete all relevant sections of the nursing history (see the following dialogue). Ongoing interviews, which occur each time you interact with your patient, do not need to be as extensive. An ongoing interview allows you to update the patient’s status and concerns, focus on changes previously identified, and review new problems. In the case study Tonya is gathering information to plan her postoperative teaching for Mr. Jacobs.

Tonya: “Mr. Jacobs, tell me what you expect over the next few days before you go home.”

Mr. Jacobs: “Well, the doctor did tell me that I would have this catheter in my bladder after I go home. But I don’t know if I have to do anything with this dressing over my stitches.”

Mr. Jacobs: “Will I have something to take for this pain as long as I am here, and what will I have to take at home?”

Tonya: “Yes, your doctor has ordered your pain medicine every 4 hours around the clock. You need to tell us when you begin to feel uncomfortable. You’ll have a pain medicine prescribed when you go home. Do you have any other concerns or questions about your surgery?”

Mr. Jacobs: “No, I don’t think so.”

Tonya: “Ok. First you’re right; the catheter will stay in your bladder, probably about 2 weeks. Your surgeon will have you come to the office to have it removed. We’ll talk about how you and your wife can manage the catheter, and we’ll probably recommend a visit by a home health nurse. I want to look at the dressing over your incision more closely. You have a small drain in the incision to make sure fluid drains and the tissues heal well. I want to talk with you and your wife about how to observe for signs of infection.”

Mr. Jacobs: “Is infection common?”

Tonya: “No, but you need to know the signs of an infection; so, if something happens once you return home, you can call your doctor quickly.”

Terminating the Interview: As in the other phases of the interview, termination requires skill. You summarize your discussion with the patient and check for accuracy of the information collected. Give your patient a clue that the interview is coming to an end. For example, say, “I have just two more questions. We’ll be finished in a few more minutes.” This helps the patient maintain direct attention without being distracted by wondering when the interview will end. This approach also gives the patient an opportunity to ask additional questions. End the interview in a friendly manner, telling the patient when you will return to provide care.

Tonya: “Thank you, Mr. Jacobs. I am just about finished with my questions. Can I get you anything?”

Mr. Jacobs: “No, I want to rest a bit.”

Tonya: You have given me a good idea of which topics we need to cover to prepare you for going home. And we’ll include your wife in these discussions. Pain control is our priority right now, and we can talk further about the medicines you’ll be taking when you go home. I want to go over catheter and dressing care after you rest so you feel prepared to go home. I also plan to come back and talk to you more about the surgery and its effects on your sexual function. Is there anything I can do for you now?”

Mr. Jacobs: “No, you’ve been helpful already.”

A skillful interviewer adapts interview strategies based on the patient’s responses. You successfully gather relevant health data when you are prepared for the interview and able to carry out each interview phase with minimal interruption.

Interview Techniques

How you conduct the interview is just as important as the questions you ask. Always use good communication techniques (see Chapter 24). During the interview you are responsible for directing the flow of the discussion so your patient has the opportunity to freely contribute stories about his or her health problems to enable you to get as much detailed information as possible. Some interviews are focused; others are comprehensive. Listen and consider the information shared because this helps you direct the patient to provide more detail or discuss a topic that might reveal a possible problem. Because a patient’s report includes subjective information, validate data from the interview later with objective data. For example, if the patient reports difficulty breathing, this will lead you to further assess respiratory rate and lung sounds during the physical examination.

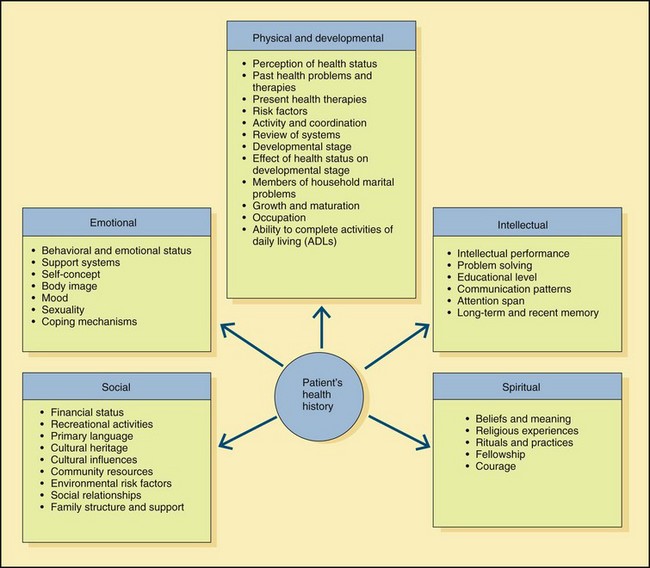

During an interview obtain information (when appropriate) about a patient’s physical, developmental, emotional, intellectual, social, and spiritual dimensions. Physical and developmental information reflects normal functioning and reveals pathological changes caused by illness, trauma, or developmental crisis. Emotional information includes the patient’s behavioral responses to changes in health and patterns of living. Relevant emotional information includes mood, perceptions, body image, self-concept, and attitudes about sexuality. Intellectual information includes intellectual performance, problem-solving ability, educational level, communication patterns, and attention span. Social information involves environmental, cultural, ethnic, or social patterns that affect the present or future level of wellness. You also collect information about life goals and values and religious practices, part of a patient’s spirituality.

Observe the patient’s nonverbal communication such as use of eye contact, body language, or tone of voice. While observing a patient’s nonverbal behavior, appearance, and interaction with the environment, determine whether the data you obtain are consistent with what the patient states verbally. Your observations lead you to pursue further objective information to form accurate conclusions. Patients also obtain information during interviews. If you establish a trusting nurse-patient relationship, the patient feels comfortable asking you questions about the health care environment, planned treatments, diagnostic testing, and available resources. The patient needs this information to make decisions about goals and the plan of care.

Open-ended Questions: In a patient-centered interview you try to find out, in the patient’s own words, what the health problem is and its probable cause. Remember, patients are usually the best resources in talking about their symptoms or relating their health history. Begin by asking the patient an open-ended question to elicit his or her story (Box 16-3). An open-ended question does not presuppose a specific answer. For example, say, “So, why did you come to the hospital today?” or “Tell me about the problems you’re having.” The use of open-ended questions prompts patients to describe a situation in more than one or two words. This technique leads to a discussion in which patients actively describe their health status. The use of open-ended questions strengthens your relationship with a patient because it shows that you want to hear the patient’s thoughts and feelings. Remember to encourage and let the patient tell the entire story.

Back Channeling: Reinforce your interest in what the patient has to say through the use of good eye contact and listening skills. In addition, you may use back channeling, which includes active listening prompts such as “all right,” “go on,” or “uh-huh.” These indicate that you have heard what the patient says and are interested in hearing the full story. Back channeling encourages a patient to give more details.

Probing: As a patient tells his or her story, encourage a full description without trying to control the direction the story takes. This requires you to probe with further open-ended statements such as, “Is there anything else you can tell me?” or “What else is bothering you?” Ask as many questions as it takes until the patient has nothing else to say. Remember to be observant. If the patient becomes fatigued or uncomfortable, know when to postpone an interview.

Closed-ended Questions: Once a patient finishes his or her story, use a problem-seeking interview technique. This approach takes the information provided in the patient’s story and more fully describes and identifies specific problem areas. For example, a patient reports experiencing indigestion over the course of several days and acknowledges having some diarrhea and loss of appetite. The patient’s explanation for the cause relates to a recent series of trips that changed his eating habits. Focus on the symptoms the patient identifies and the general indigestion problem by asking closed-ended questions that limit answers to one or two words such as “yes” or “no” or a number or frequency of a symptom (see Box 16-3). For example, ask, “How often does the diarrhea occur?” or “Do you have pain or cramping?” Closed-ended questions require short answers and clarify previous information or provide additional information. The questions do not encourage the patient to volunteer more information than you request. This type of questioning helps you acquire specific information about health problems such as symptoms, precipitating factors, or relief measures.

A good interviewer leaves with a complete story that contains enough details for understanding a patient’s perceptions of his or her health status and the information needed to help identify nursing diagnoses and/or collaborative health problems. Always clarify or validate any information about which you are unclear.

Cultural Considerations in Assessment

As a professional nurse it is important to conduct all assessments with cultural competence. This involves a conscientious understanding of your patient’s culture so you can offer better care within differing value systems and act with respect and understanding without imposing your own attitudes and beliefs (Seidel et al., 2011). To conduct an accurate and complete assessment, you need to consider a patient’s cultural background. When cultural differences exist between you and a patient, respect the unfamiliar and be sensitive to a patient’s uniqueness. For clarity, explain the intent of any questions you have. Avoid making stereotypes; the assumptions tied to stereotypes can lead you to collect inaccurate information. Instead draw on knowledge from your assessment and ask questions in a constructive and probing way to allow you to truly know who the patient is. You must be sure that you grasp exactly what a patient means and know exactly what a patient thinks you mean in words and actions. If you are unsure about what a patient is saying, ask for clarification to prevent making the wrong diagnostic conclusion. Do not make assumptions about a patient’s cultural beliefs and behaviors without validation from the patient (Seidel et al., 2011).

Communication and culture are interrelated in the way feelings are expressed verbally and nonverbally. If you learn the variations in how people of different cultures communicate, you will gather more accurate information from patients. For example, people from Spain and France make firm eye contact when speaking. However, this is considered rude or immodest by certain Asian or Middle Eastern cultures. Americans often tend to let the eyes wander (Seidel et al., 2011). Using the right approach with eye contact shows respect for your patient and likely results in the patient sharing more information. It is easier to explore cultural differences if you allow time for thoughtful answers and ask your questions in a comfortable order. Here are examples (Seidel et al., 2011; Swartz, 2010):

Nursing Health History

You gather a nursing health history during either your initial or an early contact with a patient. The history is a major component of assessment. Most health history forms are structured. However, based on information you gained from your patient’s story (during the patient-centered interview), you learn which components of the history to explore fully and which require less detail. A good assessor learns to refine and broaden questions as needed to correctly assess the patient’s unique needs. Time and patient priorities determine how complete a history will be. A comprehensive history covers all health dimensions (Fig. 16-5), allowing you to develop a complete plan of care. A nursing history usually contains the same basic components.

Biographical Information

Biographical information is factual demographic data about the patient. The patient’s age, address, occupation and working status, marital status, source of health care, and types of insurance are included. Admitting office staff usually collect this information.

Reason for Seeking Health Care

This is the information you gather when you initially set an agenda during the patient-centered interview. You learn the patient’s chief concerns or problems. Compare what you learn from the patient with the “chief complaint,” which is often typed on the patient’s admission sheet. Often you learn much more. Ask a patient why he or she is seeking health care; for example, “Tell me, Mr. Lynn, what brought you to the clinic today?” You record the patient’s response in quotations to indicate the subjective response. The patient’s statement is not diagnostic; instead it is his or her perception of reasons for seeking health care. Clarification of the patient’s perception identifies potential needs for symptom management, education, counseling, or referral to community resources.

Patient Expectations

The assessment of patient expectations is not the same as the reason for seeking medical care, although they are often related. It is important to assess the patient’s understanding of why he or she is seeking health care. Failure to identify a patient’s expectations of health care providers results in poor patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction is a standard measure of quality for all hospitals throughout the country (see Chapter 2). Patients typically have expectations of receiving information about their treatments and prognosis and a plan of care for returning home. In addition, patients expect relief of pain and other symptoms and caring expressed by health care providers. During the initial interview a patient expresses expectations when entering the health care setting. Later, as the patient interacts with health care providers, it is valuable to assess whether these expectations have changed or been met.

Present Illness or Health Concerns

If a patient presents with an illness, collect essential and relevant data about the symptoms and their effects on the patient’s health. Apply the critical thinking intellectual standards of complete and deep (see Box 15-3 on p. 199) by assessing these factors:

• Location—Where is the symptom located?

• Onset and duration—When did it start? How long has it lasted?

• Precipitating factors—What makes symptoms worse? Are there activities (e.g., exercise) that affect the symptoms?

• Relieving factors—What does the patient do to become more comfortable or relieve the symptoms?

• Quality—Have the patient describe what the symptom feels like.

• Severity—Have the patient rate the severity on a scale of 0 to 10. This gives you a baseline with which to compare in follow-up assessments.

• Concomitant symptoms—Does the patient experience other symptoms along with the primary symptom? For example, does nausea accompany pain?

Health History

The information in a patient’s health history provides data on the patient’s health care experiences and current health habits (see Fig. 16-5). Assess whether the patient has ever been hospitalized, injured, or had surgery. Include a complete medication history (including herbal and over-the-counter drugs). Also essential are descriptions of allergies, including allergic reactions to food, latex, drugs, or contact agents (e.g., soap). Asking patients if they have had problems with medications or food helps to clarify the type and amount of agent, the specific reaction, and whether the patient has required treatment. If the patient has an allergy, note the specific reaction and treatment on the assessment form.

The history also includes a description of the patient’s habits and lifestyle patterns. Assessing for the use of alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, or recreational drugs (e.g., methamphetamine or cocaine) determines the patient’s risk for diseases involving the liver, lungs, heart, or nervous system. Noting the type of habit and the frequency and duration of use provides essential data. Assessing patterns of sleep (see Chapter 42), exercise (see Chapter 38), and nutrition (see Chapter 44) are also important when planning nursing care. Ultimately your aim is to match the patient’s lifestyle patterns with approaches in the plan of care as much as possible.

Family History

The family history obtains data about immediate and blood relatives. The objectives are to determine whether the patient is at risk for illnesses of a genetic or familial nature and to identify areas of health promotion and illness prevention (see Chapter 6). The family history also provides information about family structure, interaction, support, and function that often is useful in planning care (see Chapter 10). For example, Tonya assesses the level of support Mrs. Jacobs is willing to provide. Mrs. Jacobs tells Tonya that the two have been married 32 years and states, “I feel I can do whatever is needed for him.” Tonya’s assessment shows a pattern that Mrs. Jacob is supportive and able to help her husband adjust to any initial limitations in activity when he returns home. Her assessment ultimately allows her to incorporate Mrs. Jacobs into the patient teaching portion of the patient’s plan of care (see Chapter 18). If a patient’s family is not supportive, it is better to not involve them in care. Stressful family relationships are sometimes a significant barrier when you try to help patients with problems involving loss, self-concept, spiritual health, and personal relationships.

Environmental History

The environmental history provides data about a patient’s home and working environments with a focus on determining the patient’s safety. Information about the home environment includes function of utilities, layout of rooms in the house, and the presence of any barriers or risks for injury. The history also identifies exposure to pollutants in the workplace, existence of high crime in the patient’s neighborhood, and available resources that assist patients in returning to the community.

Psychosocial History

A psychosocial history reveals the patient’s support system, which often includes spouse, children, other family members, and close friends. The history includes information about ways that the patient and family typically cope with stress (see Chapter 37). Behaviors patients use at home to cope with stress, such as walking, reading, or talking with a friend, can also be used as nursing interventions if the patient experiences stress while receiving health care. In addition, you need to learn if the patient has experienced any recent losses that create a sense of grief (see Chapter 36).

Spiritual Health

Life experiences and events shape a person’s spirituality. The spiritual dimension represents the totality of one’s being and is difficult to assess quickly (see Chapter 35). Review with patients their beliefs about life, their source for guidance in acting on beliefs, and the relationship they have with family in exercising their faith. Also assess rituals and religious practices that patients use to express their spirituality.

Review of Systems

The review of systems (ROS) is a systematic approach for collecting the patient’s self-reported data on all body systems (see Chapter 30). You probably will not cover all of the questions in each system every time you collect a history. Nevertheless, always include some questions about each system in the nursing history, but pay close attention when a patient mentions an unexpected sign or symptom. In this case explore the system more in depth. The systems you assess depend on the patient’s condition and the urgency in starting care. During the ROS ask the patient about the normal functioning of each body system and any noted changes. Such changes are subjective data because they are described as perceived by the patient. Findings from the ROS are later confirmed during the physical examination.

Documentation of History Findings

As you conduct the nursing health history, record your assessment data in a clear, concise manner using appropriate terminology. Standardized forms make it easy to enter data as the patient responds to questions. In settings that have computerized documentation, entry of assessment data becomes very easy. A clear, concise record is necessary for use by other health care professionals (see Chapter 26). Regardless of the model used in a documentation system, you need to have a thorough database that provides historical and current information about the patient’s health. This information then becomes the baseline against which you evaluate any future changes.

Physical Examination

A physical examination (see Chapter 30) is an investigation of the body to determine its state of health. The examination involves use of the techniques of inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation, and smell. A complete examination includes a patient’s height, weight, vital signs, and a head-to-toe examination of all body systems. The data from a hands-on physical assessment allow you to collect valuable objective information needed to form accurate diagnostic conclusions. Always conduct an examination competently with a caring and culturally sensitive approach.

Observation of Patient Behavior

Throughout a patient-centered interview and physical examination it is important for you to closely observe a patient’s verbal and nonverbal behaviors. The information adds depth to your objective database. You learn to determine if data obtained by observation matches what the patient communicates verbally. For example, if a patient expresses no concern about an upcoming diagnostic test but shows poor eye contact, shakiness, and restlessness, all suggesting anxiety, verbal and nonverbal data conflict. Observations direct you to gather additional objective information to form accurate conclusions about the patient’s condition.

An important aspect of observation includes a patient’s level of function: the physical, developmental, psychological, and social aspects of everyday living. Observation of level of function differs from observation you make during an interview. Observation of level of function involves watching what a patient does such as eating or making a decision about preparing a medication rather than what the patient tells you he or she can do. Observation of function often occurs in the home or in a health care setting during a return demonstration.

Diagnostic and Laboratory Data

The results of diagnostic and laboratory tests provide further explanation of alterations or problems identified during the nursing health history and physical examination. For example, during the history the patient reports having a bad cold for 6 days and at present has a productive cough with brown sputum and mild shortness of breath. On physical examination you notice an elevated temperature, increased respirations, and decreased breath sounds in the right lower lobe. You review the results of a complete blood count and note that the white blood cell count is elevated (indicating an infection). You report your results to the patient’s health care provider, who orders a chest x-ray film. When the results of the x-ray film show the presence of a right lower lobe infiltrate, the health care provider makes the medical diagnosis of pneumonia. Your assessment leads to the associated nursing diagnosis of impaired gas exchange.

Some patients collect and monitor laboratory data in the home. For example, patients with diabetes mellitus often measure blood glucose daily. Ask patients about their routine results to determine their response to illness and information about the effects of treatment measures. Compare laboratory data with the established norms for a particular test, age-group, and gender.

Interpreting and Validating Assessment Data

Whichever clinical situation you face, assessment involves the continuous interpretation of information. This is one critical thinking aspect of assessment. The successful interpretation and validation of assessment data ensure that you have collected a complete database for your patient. Ultimately this leads you to the second step of the nursing process, in which you make clinical decisions in your patient’s care. These decisions are either in the form of nursing diagnoses or collaborative problems that require treatment from several disciplines (Carpenito-Moyet, 2009) (see Chapter 17).

Interpretation

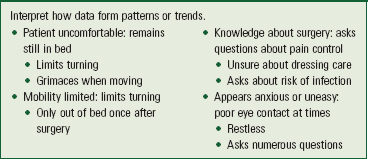

When interpreting assessment information critically, you determine the presence of abnormal findings, recognize that further observations are needed to clarify information, and begin to identify the patient’s health problems. As you form a database, you begin to see patterns of data that direct you to collect more information and clarify what you have. The patterns of data reveal meaningful and usable clusters. A data cluster is a set of signs or symptoms that you group together in a logical way (Box 16-4). The clusters begin to clearly identify the patient’s health problems.

Data Validation

Before you complete data interpretation, validate the collected information you have to avoid making incorrect inferences. Validation of assessment data is the comparison of data with another source to determine data accuracy. For example, you observe a patient crying and logically infer that it is related to hospitalization or a medical diagnosis. Making such an initial inference is not wrong, but problems result if you do not validate the inference with the patient. Instead ask, “I notice that you have been crying. Can you tell me about it?” By validating you discover the real reason for the patient’s crying behavior. Ask patients to validate unclear information obtained during an interview and history. Validate findings from the physical examination and observation of patient behavior by comparing data in the medical record and consulting with other nurses or health care team members. Often family or friends can validate your assessment information.

Validation opens the door for gathering more assessment data because it involves clarifying vague or unclear data. Occasionally you need to reassess previously covered areas of the nursing history or gather further physical examination data. Continually analyze and think about a patient’s database to make concise, accurate, and meaningful interpretations. Critical thinking applied to assessment enables you to fully understand the patient’s problems, judge the extent of the problems carefully, and discover possible relationships between the problems.

Tonya gathered initial data about the character of Mr. Jacob’s incisional pain. She applied critical thinking in her assessment as she considered what she knew about a prostatectomy and the anticipated postoperative problems that can develop. As she assessed Mr. Jacobs, she applied intellectual standards, being precise (location of pain), consistent and accurate (use of pain-rating scale), and complete (probing for factors that worsen pain). However, Mr. Jacobs was also having trouble resting, showed irritability at times when questioned, and had poor eye contact when speaking. Tonya saw the need for more information. She directed her assessment to learn more about Mr. Jacob’s concerns about the success of his surgery and what to expect during recovery. Tonya asks, “Mr. Jacobs, you earlier said that you hoped they got all of the cancer. You seem uneasy. Can you tell me how you feel about your surgery?” Mr. Jacobs tells Tonya, “My friend had prostate cancer. He had surgery, but it came back. He had a long fight.” Tonya could make several inferences from this information, but she applies the critical thinking attitude of discipline and stays focused to ensure that her assessment is accurate and comprehensive. She validates her inferences with Mr. Jacobs, “You sound anxious about the outcome of your surgery. Your friend had a recurrence of his cancer. Are you uncertain about what to expect?” Mr. Jacobs validates Tonya’s assessment, “Yes, I’m worried. My friend and family members have died from cancer. My wife depends on me; well, we depend on one another. I’m a person who likes to have information so I can make the right decisions and know what to do.” Tonya now has more complete information to help her identify Mr. Jacob’s health problems and make correct diagnostic conclusions.

Data Documentation

Data documentation is the last part of a complete assessment. The timely, thorough, and accurate documentation of facts is required in recording patient data. If you do not record an assessment finding or problem interpretation, it is lost and unavailable to anyone else caring for the patient. If information is not specific, the reader is left with only general impressions. Observing and recording patient status are legal and professional responsibilities. The Nurse Practice Acts in all states and the American Nurses Association Nursing’s Social Policy Statement (2010) require accurate data collection and recording as independent functions essential to the role of the professional nurse.

Being factual is easy after it becomes a habit. The basic rule is to record all observations succinctly. When recording data, pay attention to facts and be as descriptive as possible. Anything heard, seen, felt, or smelled should be reported exactly. Record objective information in accurate terminology (e.g., weighs 170 kg, abdomen is soft and nontender to palpation). Record subjective information from a patient in quotation marks. When entering data, do not generalize or form judgments through written communication. Conclusions about such data become nursing diagnoses and thus must be factual and accurate. As you gain experience and become familiar with clusters and patterns of signs and symptoms, you correctly conclude the existence of a problem. Review Chapter 26 for details on documentation.

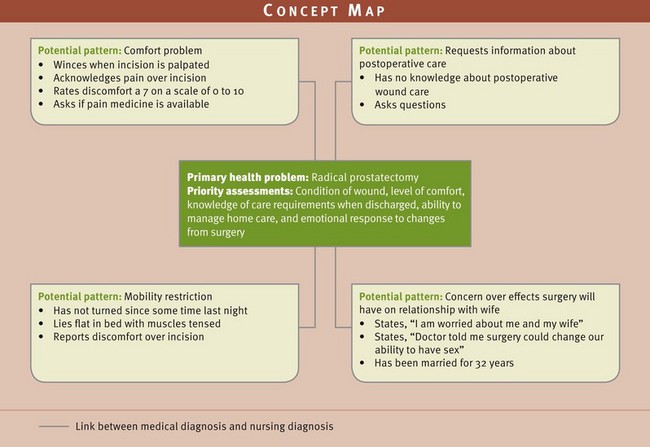

Concept Mapping

Most of the patients for whom you care present with more than one health problem. A concept map is a visual representation that allows you to graphically show the connections between a patient’s many health problems. Hinck et al. (2006) showed that concept mapping is an effective learning strategy to understand the relationships that exist among patient problems (Box 16-5). Concept maps help students evaluate their thinking patterns and see the reasons for nursing care (Taylor and Wros, 2007). Your first step in concept mapping is to organize the assessment data you collect for your patient. Placing all of the cues together into the clusters that form patterns leads you to the next step of the nursing process, nursing diagnosis (see Chapter 17). Through concept mapping you obtain a holistic perspective of your patient’s health care needs, which ultimately leads you to making better clinical decisions. Fig. 16-6 shows the first step in a concept map that Tonya will develop for Mr. Jacobs as a result of her nursing assessment. Tonya begins to identify patterns reflecting the problems Mr. Jacobs faces. As a result of the assessment she has noted: a mobility restriction, discomfort over incision, need for instruction about surgical postoperative care, and the patient’s concern over effects that surgery will have on relationship with wife. The next step (see Chapter 17) is to identify specific nursing diagnoses so appropriate nursing interventions can be provided.

Key Points

• The nursing process is a variation of scientific reasoning that involves five steps: assessment, nursing diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation.

• Assessment involves collecting information from the patient and secondary sources (e.g., family members) along with interpreting and validating the information to form a complete database.

• There are two approaches to gathering a comprehensive assessment: use of a structured database format and use of a problem-focused approach.

• Once a patient provides subjective data, explore the findings further by collecting objective data.

• During assessment critically anticipate and use an appropriate branching set of questions or observations to collect data and cluster cues of assessment information to identify emerging patterns and problems.

• In a patient-centered interview an organized conversation with the patient allows the patient to set the initial focus and initiate discussion about his or her health problems.

• A successful interview requires preparation, including reviewing all available information about the patient, preparing the interview environment, and timing to avoid interruptions.

• An initial patient-centered interview involves: (1) setting the stage, (2) gathering information about the patient’s problems and setting an agenda, (3) collecting the assessment or a nursing health history, and (4) terminating the interview.

• The best clinical interview focuses on the patient, not your own agenda.

• During an assessment interview encourage patients to tell their stories about their illnesses or health care problems.

• It is easier to explore cultural differences if you allow time for thoughtful answers and ask your questions in a comfortable order.

• When collecting a complete nursing history, let the patient’s story guide you in fully exploring the components related to his or her problems.

• Successful interpretation and validation of assessment data ensure that you have collected a complete database.

Preparing for Clinical Practice

Tonya is planning to return to Mr. Jacob’s room and spend more time discussing his concerns about going home and what to expect. She knows that Mrs. Jacobs usually comes in to visit around 11 am, just before lunchtime. Tonya believes that Mrs. Jacobs will be an important source of support in providing Mr. Jacobs any ongoing home care. The surgeon has ordered home health for Mr. Jacobs since he is going home with an indwelling catheter. Tonya’s assessment will be shared with the home health agency.

1. Tonya goes to Mr. Jacob’s room and asks if it is okay to include Mrs. Jacobs in the discussion about his postoperative care. Explain why Tonya has asked for Mr. Jacob’s consent.

2. Tonya and Mr. Jacobs have the following interaction:

Tonya: Mr. Jacobs, I want to know what you understand about your urinary catheter.

Mr. Jacobs: I think it helps me to pass urine until I heal.

Mr. Jacobs: I think the doctor said it would still be in when I go home.

Tonya’s phrase “uh huh … go on” is an example of what interviewing technique? Explain why it is useful.

3. While in Mr. Jacob’s room, Tonya discusses his knowledge about surgery and performs a routine assessment of his current condition. Tonya has collected information from her assessment of Mr. Jacobs. Identify each of the items in the assessment list as either subjective or objective data.

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. A nurse assesses a patient who comes to the pulmonary clinic. “I see that it’s been over 6 months since you’ve been in, but your appointment was for every 2 months. Tell me about that. Also I see from your last visit that the doctor recommended routine exercise. Can you tell me how successful you have been following his plan?” The nurse’s assessment covers which of Gordon’s functional health patterns?

2. The nurse asks a patient, “Describe for me your typical diet over a 24-hour day. What foods do you prefer? Have you noticed a change in your weight recently?” This series of questions would likely occur during which phase of a patient-centered interview?

3. What type of interview techniques does the nurse use when asking these questions, “Do you have pain or cramping?” “Does the pain get worse when you walk?” (Select all that apply.)

4. What technique(s) best encourage(s) a patient to tell his or her full story? (Select all that apply.)

5. A nurse gathers the following assessment data. Which of the following cues form(s) a pattern suggesting a problem? (Select all that apply.)

1. The skin around the wound is tender to touch.

2. Fluid intake for 8 hours is 800 mL.

3. Patient has a heart rate of 78 and regular.

4. Patient has drainage from surgical wound.

5. Body temperature is 101° F (38.3° C).

6. Patient asks, “I’m worried that I won’t return to work when I planned.”

6. The nurse makes the following statement during a change of shift report to another nurse. “I assessed Mr. Diaz, my 61-year-old patient from Chile. He fell at home and hurt his back 3 days ago. He has some difficulty turning in bed, and he says that he has pain that radiates down his leg. He rates his pain at a 6, but I don’t think it’s that severe. You know that back patients often have chronic pain. He seems fine when talking with his family. Have you cared for him before?” What does the nurse’s conclusion suggest?

1. The nurse is making an accurate clinical inference.

2. The nurse has gathered cues to identify a potential problem area.

3. The nurse has allowed stereotyping to influence her assessment.

4. The nurse wants to validate her information with the other nurse.

7. A nurse checks a patient’s intravenous (IV) line in his right arm and sees inflammation where the catheter enters the skin. She uses her finger to apply light pressure (i.e., palpation) just above the IV site. The patient tells her the area is tender. The nurse checks to see if the IV line is running at the correct rate. This is an example of what type of assessment?

8. A patient who visits the allergy clinic tells the nurse practitioner that he is not getting relief from shortness of breath when he uses his inhaler. The nurse decides to ask the patient to explain how he uses the inhaler, when he should take a dose of medication, and what he does when he gets no relief. On the basis of Gordon’s functional health patterns, which pattern does the nurse assess?

9. A nurse is conducting a patient-centered interview. Place the statements from the interview in the correct order.

1. “You say you’ve lost weight. Tell me how much weight you have lost in the last month.”

2. “My name is Todd. I’ll be the nurse taking care of you today. I’m going to ask you a series of questions to gather your health history.”

3. “I have no further questions. Thank you for your patience.”

4. “Tell me what brought you to the hospital.”

5. “So, to summarize, you’ve lost about 6 pounds in the last month, and your appetite has been poor—correct?”

10. Which of the following are examples of data validation? (Select all that apply.)

1. The nurse assesses the patient’s heart rate and compares the value with the last value entered in the medical record.

2. The nurse asks the patient if he is having pain and then asks the patient to rate the severity.

3. The nurse observes a patient reading a teaching booklet and asks the patient if he has questions about its content.

4. The nurse obtains a blood pressure value that is abnormal and asks the charge nurse to repeat the measurement.

5. The nurse asks the patient to describe a symptom by saying, “Go on.”

11. A patient tells the nurse during a visit to the clinic that he has been sick to his stomach for 3 days and he vomited twice yesterday. Which of the following responses by the nurse is an example of probing?

1. So you’ve had an upset stomach and began vomiting—correct?

2. Have you taken anything for your stomach?

12. The nurse is assessing the character of a patient’s migraine headache and asks, “Do you feel nauseated when you have a headache?” The patient’s response is “yes.” In this case the finding of nausea is which of the following?

13. During the review of systems in a nursing history, a nurse learns that the patient has been coughing mucus. Which of the following nursing assessments would be best for the nurse to use to confirm a lung problem? (Select all that apply.)

14. A nurse working on a medicine nursing unit is assigned to a 78-year-old patient who just entered the hospital with symptoms of H1N1 flu. The nurse finds the patient to be short of breath with an increased respiratory rate of 30 breaths/min. He lost his wife just a month ago. The nurse’s knowledge about this patient results in which of the following assessment approaches at this time? (Select all that apply.)

2. A structured comprehensive approach

3. Using multiple visits to gather a complete database

4. Focusing on the functional health pattern of role-relationship

15. A 58-year-old patient with nerve deafness has come to his doctor’s office for a routine examination. The patient wears two hearing aids. The advanced practice nurse who is conducting the assessment uses which of the following approaches while conducting the interview with this patient? (Select all that apply.)

Answers: 1. 4; 2. 3; 3. 3, 4; 4. 1, 2, 4; 5. 1, 4, 5; 6. 3; 7. 2; 8. 1; 9. 2, 4, 1, 5, 3; 10. 1, 4; 11. 3; 12. 4; 13. 3, 4; 14. 1, 3; 15. 2, 3.

References

American Nurses Association. Nursing’s social policy statement: the essence of the profession, ed 3. Washington, DC: The Association; 2010.

Austin, S. Seven legal tips for safe nursing practice. Nursing. 2008;38(3):34.

Carpenito-Moyet, LJ. Nursing diagnosis: application to clinical practice, ed 13. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

Dontje, J, et al. A unique set of interactions: The MSU sustained partnership model of nurse practitioner primary care. J Am Academy Nurs Pract. 2004;16(2):63.

Gordon, M. Nursing diagnosis: process and application, ed 3. St Louis: Mosby; 1994.

Lein, C, Wills, CE. Using patient-centered interviewing skills to manage complex patient encounters in primary care. J Am Academy Nurs Pract. 2007;19(5):215.

Lunney, M. Helping nurses use NANDA, NOC, and NIC: novice to expert. J Nurs Admin. 2006;36(3):118.

Magnan, MA, Maklebust, J. The nursing process and pressure ulcer prevention: making the connection. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2009;22:83.

Seidel, HM, et al. Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2011.

Swartz, MH. Textbook of physical diagnosis, ed 6. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

Taylor, J, Wros, P. Concept mapping: a nursing model for care planning. J Nurs Ed. 2007;46(5):211.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Summary of the HIPAA privacy rule. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/summary/privacysummary.pdf, 2003. [Accessed January 17, 2012].

Research References

Chaboyer, W, McMurray, A, Wallis, M. Bedside nursing handover: a case study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16(1):27.

Hinck, SM, et al. Student learning with concept mapping of care plans in community-based education. J Prof Nurs. 2006;22(1):23.

Phelps, SE, et al. Staff development story: concept mapping: a staff development strategy for enhancing oncology critical thinking. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2009;25(1):42.

Potter, P, et al. Understanding the cognitive work of nursing in the acute care environment. J Nurs Admin. 2005;35(7/8):327.

Smith, RC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:671.