Infection Prevention and Control

• Explain the relationship between the chain and transmission of infection.

• Give an example of preventing infection for each element of the infection chain.

• Identify the normal defenses of the body against infection.

• Discuss the events in the inflammatory response.

• Identify patients most at risk for infection.

• Describe the signs/symptoms of a localized infection and those of a systemic infection.

• Explain conditions that promote the transmission of health care–associated infection.

• Explain the difference between medical and surgical asepsis.

• Explain the rationale for standard precautions.

• Perform proper procedures for hand hygiene.

• Explain how infection control measures differ in the home versus the hospital.

• Properly don a surgical mask, sterile gown, and sterile gloves.

• Explain procedures for each isolation category.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

The incidence of patients developing infections as the direct result of contact during health care is increasing. Current trends, public awareness, and rising costs of health care have increased the importance of infection prevention and control. The Joint Commission (TJC) (2011) views this as a patient safety issue. Infection prevention and control are essential for creating a safe health care environment for patients, families, and staff. Nurses play a primary role in infection prevention and control. Patients in all health care settings are at risk for acquiring infections because of lower resistance to pathogens; increased exposure to pathogens, some of which may be resistant to most antibiotics; and invasive procedures. Health care workers are at risk for exposure to infections as a result of contact with patient blood, body fluids, and contaminated equipment and surfaces. By practicing basic infection prevention and control techniques, you avoid spreading pathogens to patients and sustaining an exposure when providing direct care.

Patients and their families need to be able to recognize sources of infection and understand measures used to protect themselves. Patient teaching must include basic information about infection, the various modes of transmission, and appropriate methods of prevention.

Health care workers protect themselves from contact with infectious material, sharps injury, and/or exposure to a communicable disease by applying knowledge of the infectious process and using appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). Diseases such as hepatitis B and C, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), tuberculosis (TB), and multidrug-resistant organisms require a greater emphasis on infection prevention and control techniques (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2004, 2006).

Scientific Knowledge Base

An infection is the invasion of a susceptible host by pathogens or microorganisms, resulting in disease. It is important to know the difference between an infection and colonization. Colonization is the presence and growth of microorganisms within a host but without tissue invasion or damage (Tweeten, 2009). Disease or infection results only if the pathogens multiply and alter normal tissue function. Some infectious diseases such as viral meningitis and pneumonia have a low or no risk for transmission. Although these illnesses can be serious for the patient, they do not pose a risk to others, including caregivers.

If an infectious disease can be transmitted directly from one person to another, it is termed a communicable disease (Tweeten, 2009). If the pathogens multiply and cause clinical signs and symptoms, the infection is symptomatic. If clinical signs and symptoms are not present, the illness is termed asymptomatic. Hepatitis C is an example of a communicable disease that can be asymptomatic. It is most efficiently transmitted through the direct passage of blood into the skin from a percutaneous exposure, even if the source patient is asymptomatic (CDC, 2010c).

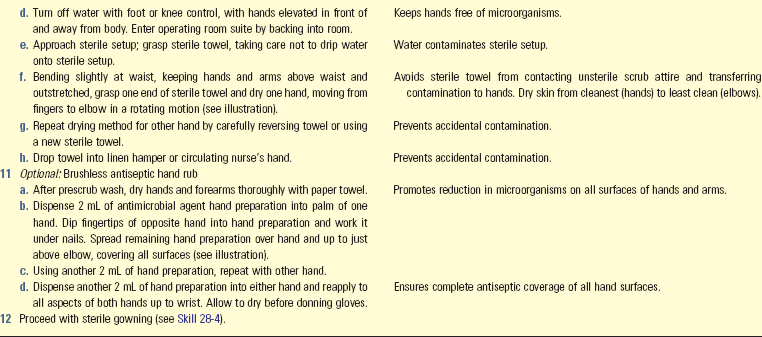

Chain of Infection

The presence of a pathogen does not mean that an infection will occur. Infection occurs in a cycle that depends on the presence of all of the following elements:

• An infectious agent or pathogen

• A reservoir or source for pathogen growth

Infection can develop if this chain remains uninterrupted (Fig. 28-1). Preventing infections involves breaking the chain of infection.

Infectious Agent

Microorganisms include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa (Table 28-1). Microorganisms on the skin are either resident or transient flora. Resident organisms (normal flora) are permanent residents of the skin, where they survive and multiply without causing illness (CDC, 2002; WHO, 2009). The potential for microorganisms or parasites to cause disease depends on the number of microorganisms present; their virulence, or ability to produce disease; their ability to enter and survive in the host; and the susceptibility of the host. Resident skin microorganisms are not virulent. However, they sometimes cause serious infection when surgery or other invasive procedures allow them to enter deep tissues or when a patient is severely immunocompromised (has an impaired immune system).

TABLE 28-1

Common Pathogens and Some Infections or Diseases They Produce

| ORGANISM | MAJOR RESERVOIR(S) | MAJOR INFECTIONS/DISEASES |

| Bacteria | ||

| Escherichia coli | Colon | Gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Skin, hair, anterior nares, mouth | Wound infection, pneumonia, food poisoning, cellulitis |

| Streptococcus (beta-hemolytic group A) organisms | Oropharynx, skin, perianal area | “Strep throat,” rheumatic fever, scarlet fever, impetigo, wound infection |

| Streptococcus (beta-hemolytic group B) organisms | Adult genitalia | Urinary tract infection, wound infection, postpartum sepsis, neonatal sepsis |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Droplet nuclei from lungs, larynx | Tuberculosis |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Genitourinary tract, rectum, mouth | Gonorrhea, pelvic inflammatory disease, infectious arthritis, conjunctivitis |

| Rickettsia rickettsii | Wood tick | Rocky Mountain spotted fever |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Skin | Wound infection, bacteremia |

| Viruses | ||

| Hepatitis A virus | Feces | Hepatitis A |

| Hepatitis B virus | Blood and certain body fluids, sexual contact | Hepatitis B |

| Hepatitis C virus | Blood, certain body fluids, sexual contact | Hepatitis C |

| Herpes simplex virus (type 1) | Lesions of mouth or skin, saliva, genitalia | Cold sores, aseptic meningitis, sexually transmitted disease, herpetic whitlow |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Blood, semen, vaginal secretions via sexual contact | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) |

| Fungi | ||

| Aspergillus organisms | Soil, dust, mouth, skin, colon, genital tract | Aspergillosis, pneumonia, sepsis |

| Candida albicans | Mouth, skin, colon, genital tract | Candidiasis, pneumonia, sepsis |

| Protozoa | ||

| Plasmodium falciparum | Blood | Malaria |

Modified from Moore V: Microbiology basics. In Carrico R, editor: APIC text of infection control and epidemiology, Washington, DC, 2009, Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology.

Transient microorganisms attach to the skin when a person has contact with another person or object during normal activities. For example, when you touch a contaminated gauze dressing, transient bacteria adhere to your skin. These organisms may be readily transmitted unless removed using hand hygiene (Larson, 2005). If hands are visibly soiled with proteinaceous material, washing with soap and water is the preferred practice. If hands are not visibly soiled, use of an alcohol-based hand product or handwashing with soap and water is acceptable for disinfecting hands of health care workers (CDC, 2002; WHO, 2009).

Reservoir

A reservoir is a place where microorganisms survive, multiply, and await transfer to a susceptible host. Common reservoirs are humans and animals (hosts), insects, food, water, and organic matter on inanimate surfaces (fomites). Frequent reservoirs for health care–associated infections (HAIs) include health care workers, especially their hands; patients; equipment; and the environment. Human reservoirs are divided into two types: those with acute or symptomatic disease and those who show no signs of disease but are carriers of it. Humans can transmit microorganisms in either case. Animals, food, water, insects, and inanimate objects can also be reservoirs for infectious organisms. To thrive, organisms require a proper environment, including appropriate food, oxygen, water, temperature, pH, and light.

Food: Microorganisms require nourishment. Some such as Clostridium perfringens, the microbe that causes gas gangrene, thrive on organic matter. Others such as Escherichia coli consume undigested foodstuff in the bowel. Carbon dioxide and inorganic material such as soil provide nourishment for other organisms.

Oxygen: Aerobic bacteria require oxygen for survival and for multiplication sufficient to cause disease. Aerobic organisms cause more infections in humans than anaerobic organisms. An example of an aerobic organism is Staphylococcus aureus. Anaerobic bacteria thrive where little or no free oxygen is available. Infections deep within the pleural cavity, in a joint, or in a deep sinus tract are typically caused by anaerobes. An example of an anaerobic organism is Clostridium difficile, an organism that causes antibiotic-induced diarrhea.

Water: Most organisms require water or moisture for survival. For example, a frequent place for microorganisms is the moist drainage from a surgical wound. Some bacteria assume a form, called a spore, which is resistant to drying. A common spore-forming bacterium is C. difficile, an organism that causes antibiotic-induced diarrhea.

Temperature: Microorganisms can live only in certain temperature ranges. Each species of bacteria has a specific temperature at which it grows best. The ideal temperature for most human pathogens is 20° to 43° C (68° to 109° F). For example, Legionella pneumophila grows best in water at 25° to 42° C (77° to 108° F) (Moore, 2009; Ritter, 2005). Cold temperatures tend to prevent growth and reproduction of bacteria (bacteriostasis). A temperature or chemical that destroys bacteria is bactericidal.

Port of Exit

After microorganisms find a site to grow and multiply, they need to find a port of exit if they are to enter another host and cause disease. Ports of exit include sites such as blood, skin and mucous membranes, respiratory tract, genitourinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, and transplacental (mother to fetus).

Skin and Mucous Membranes: The skin is considered a port of exit because any break in the integrity of the skin and mucous membranes allows pathogens to exit the body. This may be exhibited by the creation of purulent drainage. The presence of purulent drainage is a potential port of exit.

Respiratory Tract: Pathogens that infect the respiratory tract such as the influenza virus are released from the body when an infected person sneezes or coughs.

Urinary Tract: Normally urine is sterile. However, when a patient has a urinary tract infection (UTI), microorganisms exit during urination.

Gastrointestinal Tract: The mouth is one of the most bacterially contaminated sites of the human body, but most of the organisms are normal floras. Organisms that are normal floras in one person can be pathogens in another. For example, organisms exit when a person expectorates saliva. In addition, gastrointestinal ports of exit include bowel elimination, drainage of bile via surgical wounds, or drainage tubes.

Modes of Transmission

Each disease has a specific mode of transmission. Many times you are able to do little about the infectious agent or the susceptible host, but by practicing infection prevention and control techniques such as hand hygiene, you interrupt the mode of transmission (Box 28-1). The same microorganism is sometimes transmitted by more than one route. For example, varicella zoster (chickenpox) is spread by the airborne route in droplet nuclei or by direct contact.

The major route of transmission for pathogens identified in the health care setting is the unwashed hands of the health care worker (CDC, 2002; Cipriano, 2007; WHO, 2009). Equipment used within the environment (e.g., a stethoscope, blood pressure cuff, or bedside commode) often becomes a source for the transmission of pathogens.

Port of Entry

Organisms enter the body through the same routes they use for exiting. For example, when a needle pierces a patient’s skin, organisms enter the body if proper skin preparation is not performed first. Factors such as a depressed immune system that reduce body defenses enhance the chances of pathogens entering the body.

Susceptible Host

Susceptibility to an infectious agent depends on the individual’s degree of resistance to pathogens. Although everyone is constantly in contact with large numbers of microorganisms, an infection does not develop until an individual becomes susceptible to the strength and numbers of the microorganisms. A person’s natural defenses against infection and certain risk factors (e.g., age, nutritional status, presence of chronic disease, trauma, and smoking) affect susceptibility (resistance) (Fardo, 2009). Organisms such as S. aureus with resistance to key antibiotics are becoming more common in all health care settings, but especially acute care. The increased resistance is associated with the frequent and sometimes inappropriate use of antibiotics over the years in all settings (i.e., acute care, ambulatory care, clinics, and long-term care) (Arnold, 2009).

The Infectious Process

By understanding the chain of infection, you have knowledge that is vital in preventing infections. When the patient acquires an infection, observe for signs and symptoms of infection and take appropriate actions to prevent its spread. Infections follow a progressive course (Box 28-2).

If an infection is localized (e.g., a wound infection), the patient usually experiences localized symptoms such as pain, tenderness, and redness at the wound site. Use standard precautions, appropriate PPE, and hand hygiene when assessing the wound. The use of these precautions and hand hygiene blocks the spread of infection to other sites or other patients. An infection that affects the entire body instead of just a single organ or part is systemic and can become fatal if undetected and untreated.

The course of an infection influences the level of nursing care provided. The nurse is responsible for properly administering antibiotics, monitoring the response to drug therapy (see Chapter 31), using proper hand hygiene, and standard precautions. Supportive therapy includes providing adequate nutrition and rest to bolster defenses against the infectious process. The course of care for the patient often has additional effects on body systems affected by the infection.

Defenses Against Infection

The body has natural defenses that protect against infection. Normal floras, body system defenses, and inflammation are all nonspecific defenses that protect against microorganisms regardless of prior exposure. If any body defenses fail, an infection usually occurs and leads to a serious health problem.

Normal Floras

The body normally contains microorganisms that reside on the surface and deep layers of skin, in the saliva and oral mucosa, and in the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts. A person normally excretes trillions of microbes daily through the intestines. Normal floras do not usually cause disease when residing in their usual area of the body but instead participate in maintaining health.

Normal floras of the large intestine exist in large numbers without causing illness. They also secrete antibacterial substances within the walls of the intestine. The normal floras of the skin exert a protective, bactericidal action that kills organisms landing on the skin. The mouth and pharynx are also protected by floras that impair growth of invading microbes. Normal floras maintain a sensitive balance with other microorganisms to prevent infection. Any factor that disrupts this balance places a person at increased risk for acquiring a disease. For example, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for the treatment of infection can lead to suprainfection. A suprainfection develops when broad-spectrum antibiotics eliminate a wide range of normal flora organisms, not just those causing infection. When normal bacterial floras are eliminated, body defenses are reduced, which allows for disease-producing microorganisms to multiply, causing illness (Arnold, 2009).

Body System Defenses

A number of body organ systems have unique defenses against infection (Table 28-2). The skin, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract are easily accessible to microorganisms. Pathogenic organisms can adhere to the surface skin, be inhaled into the lungs, or be ingested with food. Each organ system has defense mechanisms physiologically suited to its specific structure and function. For example, the lungs cannot completely control the entrance of microorganisms. However, the airways are lined with moist mucous membranes and hairlike projections, or cilia, that rhythmically beat to move mucus or cellular debris up to the pharynx to be expelled through swallowing.

TABLE 28-2

Normal Defense Mechanisms Against Infection

Inflammation

The cellular response of the body to injury, infection, or irritation is termed inflammation. Inflammation is a protective vascular reaction that delivers fluid, blood products, and nutrients to an area of injury. The process neutralizes and eliminates pathogens or dead (necrotic) tissues and establishes a means of repairing body cells and tissues. Signs of localized inflammation include swelling, redness, heat, pain or tenderness, and loss of function in the affected body part. When inflammation becomes systemic, other signs and symptoms develop, including fever, leukocytosis, malaise, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, lymph node enlargement, or organ failure.

Physical agents, chemical agents, or microorganisms trigger the inflammatory response. Mechanical trauma, temperature extremes, and radiation are examples of physical agents. Chemical agents include external and internal irritants such as harsh poisons or gastric acid. Sometimes microorganisms also trigger this response.

After tissues are injured, a series of well-coordinated events occurs. The inflammatory response includes the following:

1. Vascular and cellular responses

2. Formation of inflammatory exudates (fluid and cells that are discharged from cells or blood vessels [e.g., pus or serum])

Vascular and Cellular Responses: Acute inflammation is an immediate response to cellular injury. Rapid vasodilation occurs, allowing more blood near the location of the injury. The increase in local blood flow causes the redness and localized warmth at the site of inflammation.

Injury causes tissue damage and possibly necrosis. As a result the body releases chemical mediators that increase the permeability of small blood vessels; and fluid, protein, and cells enter interstitial spaces. The accumulation of fluid appears as localized swelling (edema). Another sign of inflammation is pain. The swelling of inflamed tissues increases pressure on nerve endings, causing pain. As a result of physiological changes occurring with inflammation, the involved body part may have a temporary loss of function. For example, a localized infection of the hand causes the fingers to become swollen, painful, and discolored. Joints become stiff as a result of swelling, but function of the fingers returns when inflammation subsides.

The cellular response of inflammation involves white blood cells (WBCs) arriving at the site. WBCs pass through blood vessels and into the tissues. Phagocytosis is a process that involves the destruction and absorption of bacteria. Through the process of phagocytosis, specialized WBCs, called neutrophils and monocytes, ingest and destroy microorganisms or other small particles. If inflammation becomes systemic, other signs and symptoms develop. Leukocytosis, or an increase in the number of circulating WBCs, is the response of the body to WBCs leaving blood vessels. A serum WBC count is normally 5,000 to 10,000/mm3 but typically rise to 15,000 to 20,000/mm3 and higher during inflammation. Fever is caused by phagocytic release of pyrogens from bacterial cells, which causes a rise in the hypothalamic set point (see Chapter 29).

Inflammatory Exudate: Accumulation of fluid and dead tissue cells and WBCs forms an exudate at the site of inflammation. Exudate may be serous (clear, like plasma), sanguineous (containing red blood cells), or purulent (containing WBCs and bacteria). Usually the exudate is cleared away through lymphatic drainage. Platelets and plasma proteins such as fibrinogen form a meshlike matrix at the site of inflammation to prevent its spread.

Tissue Repair: When there is injury to tissue cells, healing involves the defensive, reconstructive, and maturative stages (see Chapter 48). Damaged cells are eventually replaced with healthy new cells. The new cells undergo a gradual maturation until they take on the same structural characteristics and appearance as the previous cells. If inflammation is chronic, tissue defects sometimes fill with fragile granulation tissue. Granulation tissue is not as strong as tissue collagen and assumes the form of scar tissue.

Health Care–Associated Infections

Patients in health care settings, especially hospitals and long-term care facilities, have an increased risk of acquiring infections. Health care–associated infections (HAIs), formerly called nosocomial or health care–acquired infections, result from the delivery of health services in a health care facility. They occur as the result of invasive procedures, antibiotic administration, the presence of multidrug-resistant organisms, and breaks in infection prevention and control activities.

Patients who develop HAIs often have multiple illnesses, are older adults, and are poorly nourished; thus they are more susceptible to infections. In addition, many patients have a lowered resistance to infection because of underlying medical conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus or malignancies) that impair or damage the immune response of the body. Invasive treatment devices such as intravenous (IV) catheters or indwelling urinary catheters impair or bypass the natural defenses of the body against microorganisms. Critical illness increases patients’ susceptibility to infections, especially multidrug-resistant bacteria. Meticulous hand hygiene practices, the use of chlorhexidine washes, and other advances in intensive care unit (ICU) infection prevention help to prevent these infections (Doyle et al., 2011).

Iatrogenic infections are a type of HAI from a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure. For example, procedures such as a bronchoscopy and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics increase the risk for certain infections (Arnold, 2009; Stricof, 2009). Use critical thinking when practicing aseptic techniques and follow basic infection prevention and control policies and procedures to reduce the risk of HAIs. Always consider the patient’s risks for infection and anticipate how the approach to care increases or decreases the risk.

Health care–associated infections are exogenous or endogenous. An exogenous infection comes from microorganisms found outside the individual such as Salmonella, Clostridium tetani, and Aspergillus. They do not exist as normal floras. Endogenous infection occurs when part of the patient’s flora becomes altered and an overgrowth results (e.g., staphylococci, enterococci, yeasts, and streptococci). This often happens when a patient receives broad-spectrum antibiotics that alter the normal floras. When sufficient numbers of microorganisms normally found in one body site move to another site, an endogenous infection develops. The number of microorganisms needed to cause a health care–associated infection depends on the virulence of the organism, the susceptibility of the host, and the body site affected.

The number of health care employees having direct contact with a patient, the type and number of invasive procedures, the therapy received, and the length of hospitalization influence the risk of infection. Major sites for HAIs include surgical or traumatic wounds, urinary and respiratory tracts, and the bloodstream (Box 28-3).

Health care–associated infections significantly increase costs of health care. Older adults have increased susceptibility to these infections because of their affinity to chronic disease and the aging process itself (Box 28-4). Extended stays in health care institutions, increased disability, increased costs of antibiotics, and prolonged recovery times add to the expenses both of the patient and the health care institution and funding bodies (e.g., Medicare). Often costs for HAIs are not reimbursed; as a result, prevention has a beneficial financial impact and is an important part of managed care. TJC (2011) lists several national safety goals focusing on the care of older adults (e.g., ensuring that older adults receive influenza and pneumonia vaccine or preventing infection after surgery).

Nursing Knowledge Base

Body substances such as feces, urine, and wound drainage contain potentially infectious microorganisms. Health care workers are at risk for exposure to microorganisms in the hospital and/or home setting (Fauerbach, 2009). They follow specific infection prevention practices to reduce the risk of cross-contamination and transmission to other patients when caring for a patient with a known or suspected infection (CDC, 2007).

The experience of having a serious infection creates feelings of anxiety, frustration, loneliness, and anger in patients and/or their families (Calfree et al., 2008). These feelings worsen when patients are isolated to prevent transmission of a microorganism to other patients or health care staff. Isolation disrupts normal social relationships with visitors and caregivers. Patient safety is usually an additional risk for the patient on isolation precautions (Murphy, 2009). For example, an older patient with dementia is at increased risk for falling when confined in a room with the door closed. When family members fear the possibility of developing the infection, they avoid contact with the patient. Some patients perceive the simple procedures of proper hand hygiene and gown and glove use as evidence of rejection. Help patients and families reduce some of these feelings by discussing the disease process, explaining isolation procedures, and maintaining a friendly, understanding manner.

When establishing a plan of care, it is important for you to know how a patient reacts to an infection or infectious disease. The challenge is to identify and support behaviors that maintain human health or prevent infection.

Factors Influencing Infection Prevention and Control

Multiple factors influence a patient’s susceptibility to infection. It is important to understand how each of these factors alone or in combination increases this risk. When more than one factor is present, the patient’s susceptibility often increases, which affects length of stay, recovery time, and/or overall level of health following an illness. Understanding these factors assists in assessing and caring for a patient who has an infection or is at risk for one.

Age

Throughout life, susceptibility to infection changes. For example, an infant has immature defenses against infection. Born with only the antibodies provided by the mother, the infant’s immune system is incapable of producing the necessary immunoglobulins and WBCs to adequately fight some infections. However, breastfed infants often have greater immunity than bottle-fed infants because they receive their mother’s antibodies through the breast milk. As the child grows, the immune system matures; but the child is still susceptible to organisms that cause the common cold, intestinal infections, and infectious diseases such as mumps, measles, and chickenpox (if not vaccinated).

The young or middle-age adult has refined defenses against infection. Viruses are the most common cause of communicable illness in young or middle-age adults. Since 2000 there has been a major effort to vaccinate all children against all infectious diseases for which vaccines are available. Vaccine-preventable disease levels are at or near record lows (CDC, 2011). For example; hepatitis B infection in children and adolescents decreased by 89% in 2005 (CDC, 2005b).

Defenses against infection change with aging (Lesser, Paiusi, and Leips, 2006). The immune response, particularly cell-mediated immunity, declines. Older adults also undergo alterations in the structure and function of the skin, urinary tract, and lungs. For example, the skin loses its turgor, and the epithelium thins. As a result it is easier to tear or abrade the skin, which increases the potential for invasion by pathogens. In addition, older adults who are hospitalized or reside in an assisted-living or residential care facility are at risk for airborne infections. Ensuring that health care workers are vaccinated against influenza reduces the transmission of this illness in older adults (Thomas et al., 2010).

Nutritional Status

A patient’s nutritional health directly influences susceptibility to infection. A reduction in the intake of protein and other nutrients such as carbohydrates and fats reduces body defenses against infection and impairs wound healing (see Chapter 48). Patients with illnesses or problems that increase protein requirements, such as extensive burns and conditions causing fever, are at further risk. Patients who have undergone surgery, for example, require increased protein. A thorough diet history is necessary. Determine a patient’s normal daily nutrient intake and whether preexisting problems such as nausea, impaired swallowing, or oral pain alter food intake. Confer with a dietitian to assist in calculating the calorie count of foods ingested.

Stress

The body responds to emotional or physical stress by the general adaptation syndrome (see Chapter 37). During the alarm stage the basal metabolic rate increases as the body uses energy stores. Adrenocorticotropic hormone increases serum glucose levels and decreases unnecessary antiinflammatory responses through the release of cortisone. If stress continues or becomes intense, elevated cortisone levels result in decreased resistance to infection. Continued stress leads to exhaustion, which causes depletion in energy stores, and the body has no resistance to invading organisms. The same conditions that increase nutritional requirements such as surgery or trauma also increase physiological stress.

Disease Process

Patients with diseases of the immune system are at particular risk for infection. Leukemia, AIDS, lymphoma, and aplastic anemia are conditions that compromise a host by weakening defenses against infectious organisms. For example, patients with leukemia are unable to produce enough WBCs to ward off infection. Patients with HIV are often unable to ward off simple infections and are prone to opportunistic infections.

Patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and multiple sclerosis are also more susceptible to infection because of general debilitation and nutritional impairment. Diseases that impair body system defenses such as emphysema and bronchitis (which impair ciliary action and thicken mucus), cancer (which alters the immune response), and peripheral vascular disease (which reduces blood flow to injured tissues) increase susceptibility to infection. Patients with burns have a high susceptibility to infection because of the damage to skin surfaces. The greater the depth and extent of the burns, the higher the risk for infection.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

Assessment

During the assessment process, thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. Determine how the patient feels about the illness or risk for infection. Assess his or her defense mechanisms, susceptibility, and knowledge of how infections are transmitted (Table 28-3). Conduct a review of systems and travel history with the patient and family to reveal any risks for exposure to a communicable disease. Immunization and vaccination history are also very useful. It is important to be thorough in assessing a patient’s clinical condition. A medication history is necessary to identify medications that increase a patient’s susceptibility to infection. An analysis of laboratory findings provides information about a patient’s defense against infection. The early recognition of infection or risk factors helps you make the correct nursing diagnosis and establish a treatment plan.

TABLE 28-3

Assessing the Risk of Infection in Adults

| RISK FACTOR | CAUSES | OUTCOME |

| Chronic disease | COPD, heart failure, diabetes | Pneumonia, skin breakdown, venous stasis ulcers |

| Lifestyle—high-risk behaviors | Exposure to communicable/infectious diseases, use of IV drugs and other drugs/substances | STIs, HIV, HBV, HCV, opportunistic infections, viral infections, yeast infections, liver failure |

| Occupation | Miner, unemployed, homeless | Black lung disease, pneumonia, TB, poor nutritional intake, lack of access to medical care, stress |

| Diagnostic procedures | Invasive radiology, transplant | Multiple IV lines, immunosuppressive drugs |

| Heredity | Sickle cell disease, diabetes | Anemia, delayed healing |

| Travel history | West Nile virus, SARS, avian flu, Hantavirus | Meningitis, acute respiratory distress |

| Trauma | Fractures, internal bleeding | Sepsis, secondary infection |

| Nutrition | Obesity, anorexia | Impaired immune response |

COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IV, intravenous; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; TB, tuberculosis.

Modified from Tweeten SM: General principles of epidemiology. In Carrico R, editor: APIC text of infection control and epidemiology, Washington, DC, 2009, Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

Some patients with infection have a variety of problems. It is important to ask specific questions to determine the patient’s and family’s needs related to the risk for infection or disease status (Box 28-5). These needs vary from patient to patient and include physical, psychological, social, or economic needs. Patients with chronic or serious infection, especially communicable infections such as TB or AIDS, experience psychological and social problems from self-imposed isolation or rejection by friends and family. Ask the patient how the infection affects the ability to maintain relationships and perform activities of daily living. Determine whether chronic infection has drained the patient’s financial resources. Ask about his or her expectations of care and determine how much he or she wants to be involved in planning care. Some patients and their families wish to know more about the disease process, whereas others only want to know the interventions necessary to treat the infection. Encourage patients to verbalize their expectations so you are able to establish interventions to meet patients’ priorities.

Status of Defense Mechanisms

Review physical assessment findings and the patient’s medical condition to determine the status of normal defense mechanisms against infection. For example, any break in the skin such as an ulcer on the foot of a patient who has diabetes is a potential site for infection. Any reduction in the primary or secondary defenses of the body against infection, such as a weakened ability to cough, places a patient at increased risk.

Patient Susceptibility

As noted in a previous section, age, nutritional status, stress, and disease process are factors that influence susceptibility to infection. Gather information about each factor through your interview and the patient’s and family’s medical history.

Medical Therapy: Some drugs and medical therapies compromise immunity to infection. Assess your patient’s medication history to determine whether he or she takes any medications that increase infection susceptibility. These include any over-the-counter medications and herbal supplements. A review of therapies received within the health care setting further reveals risks. For example, adrenal corticosteroids, prescribed for several conditions, are antiinflammatory drugs that cause protein breakdown and impair the inflammatory response against bacteria and other pathogens. Cytotoxic and antineoplastic drugs attack cancer cells but also cause the side effects of bone marrow depression and normal cell toxicity, which affects the body’s response against pathogens.

Clinical Appearance

The signs and symptoms of infection may be local or systemic. Localized infections are most common in areas of skin or mucous membrane breakdown such as surgical and traumatic wounds, pressure ulcers, oral lesions, and abscesses.

To assess an area for localized infection, first inspect it for redness and swelling caused by inflammation. Because there may be drainage from open lesions or wounds, wear clean gloves. Infected drainage may be yellow, green, or brown, depending on the pathogen. For example, green nasal secretions often indicate a sinus infection. Ask the patient about pain or tenderness around the site. Some patients complain of tightness and pain caused by edema. If the infected area is large enough, movement is restricted. Gentle palpation of an infected area usually results in some degree of tenderness. Wear protective eyewear and a surgical mask when there is a risk for splash or spray with blood or body fluids.

Systemic infections cause more generalized symptoms than local infection. These symptoms often include fever, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and malaise. Lymph nodes that drain the area of infection often become enlarged, swollen, and tender during palpation. For example, an abscess in the peritoneal cavity causes enlargement of lymph nodes in the groin. An infection of the upper respiratory tract causes cervical lymph node enlargement. If an infection is serious and widespread, all major lymph nodes may enlarge.

Systemic infections sometimes develop after treatment for localized infection has failed. Be alert for changes in the patient’s level of activity and responsiveness. As systemic infections develop, an elevation in body temperature can lead to episodes of increased heart and respiratory rates and low blood pressure. Involvement of major body systems produces specific symptoms. For example, a pulmonary infection results in a productive cough with purulent sputum. A UTI results in cloudy, foul-smelling urine.

An infection does not always present with typical signs and symptoms in all patients. For example, some older adults have an advanced infection before it is identified. Because of the aging process, there is a reduced inflammatory and immune response. Older adults have increased fatigue and diminished pain sensitivity. A reduced or absent fever response often occurs from chronic use of aspirin or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Atypical symptoms such as confusion, incontinence, or agitation may be the only symptoms of an infectious illness (Fardo, 2009). For example, as many as 20% of older adults with pneumonia do not have the typical signs and symptoms of fever, shaking, chills, and rusty productive sputum. Often the only symptoms are an unexplained increase in heart rate, confusion, or generalized fatigue. A pneumonia vaccine is available and recommended for all persons with chronic respiratory problems and those over 65 years of age.

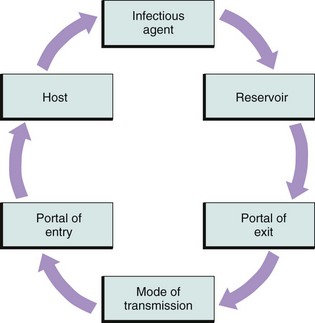

Laboratory Data

Review laboratory data as soon as they are available. Laboratory values such as increased WBCs and/or a positive blood culture often indicate infection (Table 28-4). However, laboratory values are not enough to detect infection. You need to assess other clinical signs. A culture result may show growth of an organism in the absence of infection. For example, in the older adult bacterial growth in urine without clinical symptoms does not always indicate the presence of a UTI (Gantz, 2009). It is also important to note that laboratory values often vary from laboratory to laboratory. Be sure to know the standard range of laboratory values for the laboratory in your facility.

Nursing Diagnosis

During assessment gather objective data such as inspection of an open incision or a reduced caloric intake record and subjective data such as a patient’s complaint of tenderness over a surgical wound site. Review the data carefully, looking for clusters of defining characteristics or risk factors that create a pattern. This pattern suggests a specific nursing diagnosis (Box 28-6). The following are examples of nursing diagnoses that often apply:

• Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements

• Impaired oral mucous membrane

It is necessary to validate data such as inspecting the integrity of a wound more carefully and to review laboratory findings to confirm a diagnosis. Success in planning appropriate nursing interventions depends on the accuracy of the diagnosis and the ability to meet the patient’s needs. This requires an accurate related to factor in the diagnostic statement. For example, minimizing the risk for infection in a patient with a diagnosis of impaired oral mucous membrane related to mouth breathing requires proper hygiene measures, including frequent oral care. Minimizing the risk for infection in a patient with a nursing diagnosis of imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to inability to absorb nutrients requires good nutritional support and fluid balance. The correct “related to” factor will ensure relevant and appropriate interventions for a patient.

Planning

The patient’s care plan is based on each nursing diagnosis and related factor (see the Nursing Care Plan). Develop a plan that sets realistic outcomes so interventions are purposeful, direct, and measurable. When you care for a patient with broken skin who has a nursing diagnosis of risk for infection, implement skin and wound care measures to promote healing. The expected outcome of “absence of drainage” sets a target for measuring the patient’s improvement. Common goals of care applicable to patients with infection often include the following:

• Preventing exposure to infectious organisms

• Controlling or reducing the extent of infection

• Maintaining resistance to infection

• Verbalizing understanding of infection prevention and control techniques (e.g., hand hygiene)

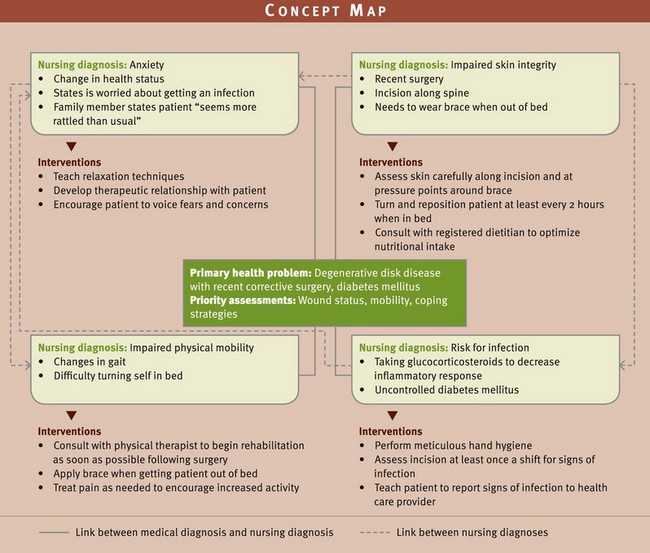

Patients often have multiple nursing diagnoses that are interrelated, and one diagnosis impacts on another diagnosis. A concept map for Mrs. Andrews helps to show the relationships between multiple nursing diagnoses (Fig. 28-2).

Setting Priorities

Establish priorities for each diagnosis and related goals of care. For example, you are caring for a patient with cancer who develops an open wound and is unable to tolerate solid foods. The priority of administering therapies to promote wound healing such as improved nutritional intake overrides the goal of educating the patient to assume self-care therapies at home. When the patient’s condition improves, the priorities change, and patient education becomes an essential intervention.

Teamwork and Collaboration

The development of a care plan includes prevention and infection control practices from multiple disciplines. Select interventions in collaboration with the patient, the family, and others on the health care team such as the dietitian or respiratory therapist. Know the patient’s sociocultural preferences to help you in identifying the most appropriate types of interventions (Box 28-7). In addition, consult with an expert in infection control in planning the patient’s care. Before discharge consult with case management to complete a home assessment and identify home health needs. Case managers work with the patient, family, and home care services to ensure that a safe discharge plan is in place.

When care continues into the patient’s home, the home care nurse plans to ensure that the home environment supports good infection prevention and control practices. For example, if a patient does not have running water yet requires wound care, even simple hand hygiene with soap and water is difficult to achieve. Home health nurses instruct patients to perform hand hygiene with either bottled water and soap or alcohol-based hand products.

Implementation

By identifying and assessing a patient’s risk factors and implementing appropriate measures, you can effectively reduce the risk of infection.

Health Promotion

Use your critical thinking skills to prevent an infection from developing or spreading. In the home and community settings, strengthen the defenses of a potential host against infection. Nutrition support, rest, maintenance of physiological protective mechanisms, and recommended immunizations protect patients. For example, an annual vaccination to protect against influenza is an important element of risk reduction.

In health care settings, implement procedures to minimize the numbers and kinds of organisms that are transmitted. Eliminating reservoirs of infection, controlling ports of exit and entry, and avoiding actions that transmit microorganisms prevent bacteria from finding a new site in which to grow. Proper use of sterile supplies, barrier precautions, standard precautions, transmission-based precautions, and hand hygiene are examples of methods to control the spread of microorganisms.

Having an infection prevention and control conscience helps you apply principles of medical and surgical asepsis. When a patient develops an infection, implement techniques and procedures to reduce the opportunity for health care personnel and other patients to be exposed to the infection. Patients with communicable diseases often require specific isolation precautions to break the chain of infection.

Acute Care

Treatment of an infectious process includes eliminating the infectious organisms and supporting the patient’s defenses. To identify the causative organism, the nurse collects specimens of body fluids such as sputum or drainage from infected body sites for cultures. When the disease process or causative organism is identified, the health care provider prescribes the most effective treatment.

Systemic infections require measures to prevent complications of fever (see Chapter 29). Maintaining intake of fluids prevents dehydration resulting from diaphoresis. The patient’s increased metabolic rate requires an adequate nutritional intake. Rest preserves energy for the healing process.

Localized infections often require measures to assist removal of debris to promote healing. You apply principles of wound care to remove infected drainage from wound sites and support the integrity of healing wounds. When changing a dressing, wear a mask and goggles or a mask with a face shield if splashing or spraying with blood or body fluids is anticipated. Apply gloves to reduce the transmission of microorganisms into the wound (CDC, 2007). Apply special dressings to facilitate removal of drainage and promote healing of wound margins. Sometimes a surgeon will insert drainage tubes to remove infected drainage from body cavities. Use medical and surgical aseptic techniques to manage wounds and ensure correct handling of all drainage or body fluids (see Chapter 48).

During the course of infection, support the patient’s body defense mechanisms. For example, if a patient has diarrhea, maintain skin integrity by frequent cleansing, application of a skin barrier cream, and frequent repositioning to prevent breakdown and the entrance of additional microorganisms. Other routine hygiene measures such as cleaning the oral cavity and bathing protect the skin and mucous membranes from invasion and overgrowth of organisms.

Asepsis

Base efforts to minimize the onset and spread of infection on the principles of aseptic technique. Asepsis is the absence of pathogenic (disease-producing) microorganisms. Aseptic technique refers to practices/procedures that help reduce the risk for infection. The two types of aseptic technique are medical and surgical asepsis.

Medical asepsis, or clean technique, includes procedures for reducing the number of organisms present and preventing the transfer of organisms. Hand hygiene, barrier techniques, and routine environmental cleaning are examples of medical asepsis.

Principles of medical asepsis are also commonly followed in the home; hand hygiene with soap and water before preparing food is an example. It is also important to include cultural, religious, or social beliefs of the patient and family.

After an object becomes unsterile or unclean, it is considered contaminated. In medical asepsis an area or object is considered contaminated if it contains or is suspected of containing pathogens. For example, a used bedpan, the over-bed table, and a used dressing are considered to be contaminated items.

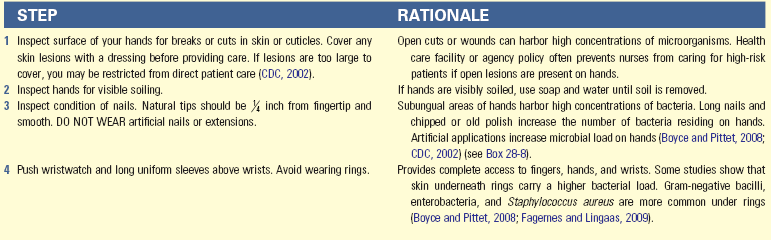

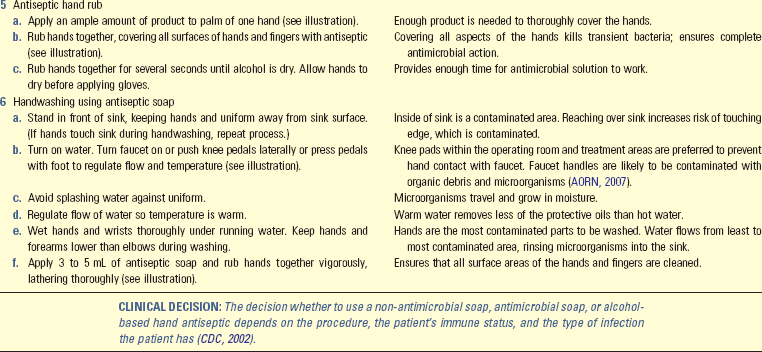

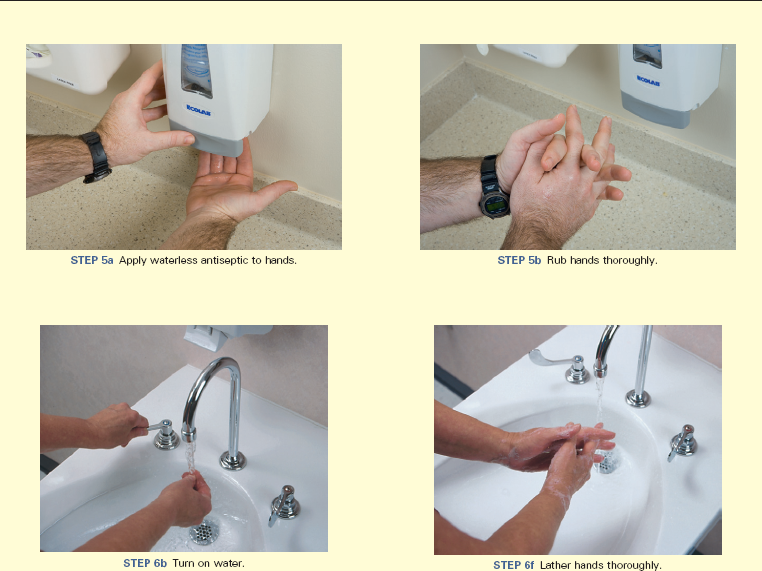

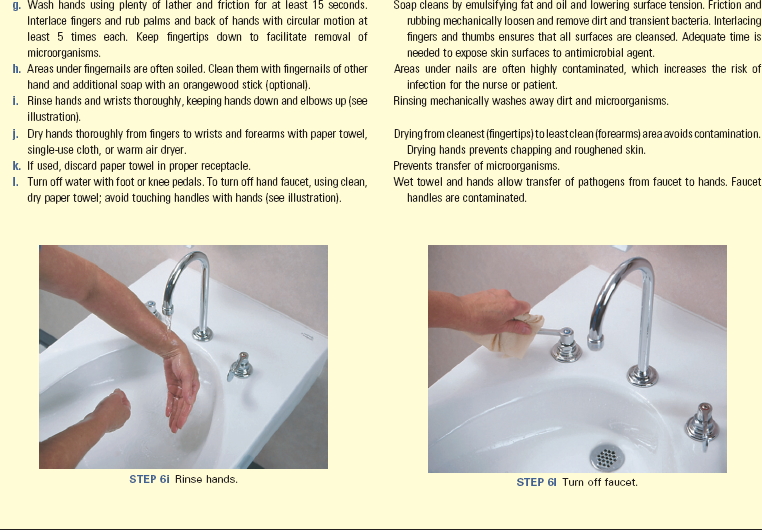

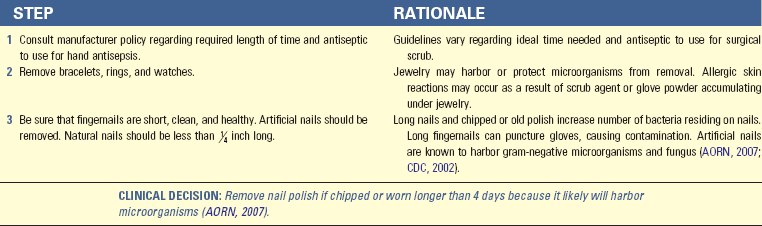

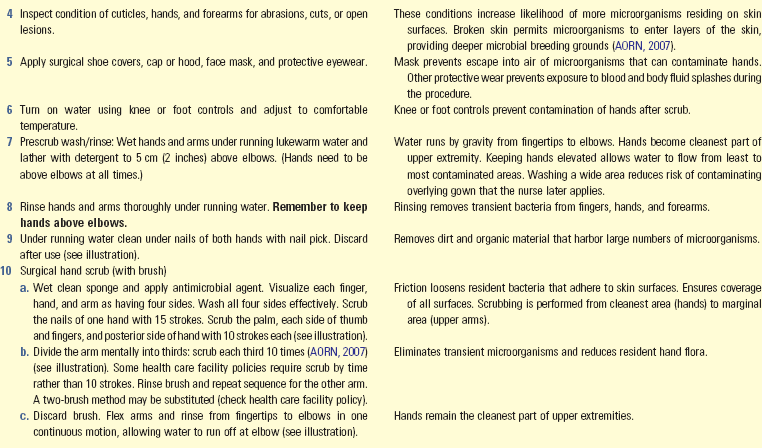

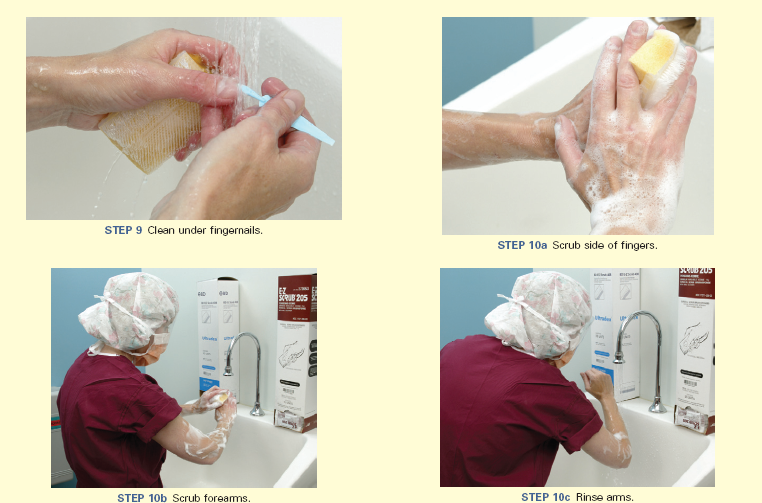

You will learn to follow certain principles and procedures, including standard precautions, to prevent and control infection and its spread. Standard precautions apply to contact with blood, body fluid, nonintact skin, and mucous membranes from all patients. These precautions protect the patient and provide protection for the health care worker. A major component of patient and worker protection is hand hygiene (Skill 28-1, pp. 425-427). Hand hygiene includes using an instant alcohol hand antiseptic before and after providing patient care, washing hands with soap and water when they are visibly soiled, and performing a surgical scrub. Handwashing is the act of washing hands with soap and water, followed by rinsing under a stream of water for 15 seconds (CDC, 2002). The friction of rubbing hands together removes soil and transient organisms from the hands.

Contaminated hands of health care workers are a primary source of infection transmission in health care settings. It is recommended that health care workers have well-manicured nails and refrain from wearing artificial nails (Box 28-8) to reduce microorganism transmission. Transmission of infection occurs very easily. For example, you are performing a dressing change, and the patient’s roommate asks for assistance with a blocked IV line. If you do not perform hand hygiene before handling the IV line, you transfer organisms from the patient’s wound to the roommate’s IV site. TJC has identified compliance with proper hand hygiene as a National Patient Safety Goal (TJC, 2011).

The use of alcohol-based hand rubs is recommended by the CDC (2002) to improve hand hygiene practices, protect health care worker’s hands, and reduce transmission of pathogens to patients and personnel in health care settings. Alcohols have excellent germicidal activity and are as effective as soap and water.

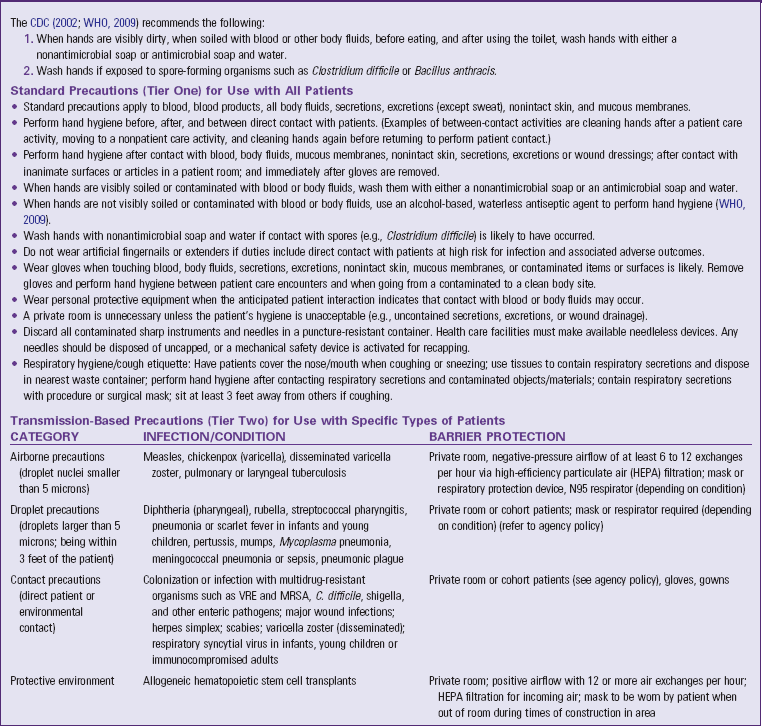

The CDC (2002; WHO, 2009) recommends the following:

1. When hands are visibly dirty, when soiled with blood or other body fluids, before eating, and after using the toilet, wash hands with water and either a nonantimicrobial or antimicrobial soap.

2. Wash hands if exposed to spore-forming organisms such as Clostridium difficile or Bacillus anthracis.

3. If hands are not visibly soiled (WHO, 2009), use an alcohol-based waterless antiseptic agent for routinely decontaminating hands in the following clinical situations:

a. Before, after, and between direct patient contact (e.g., taking a pulse, lifting a patient, performing a procedure)

b. After contact with body fluids or excretions, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, or wound dressings

c. When moving from a contaminated to a clean body site during patient care

d. After contact with inanimate surfaces or objects in the patient’s room (e.g., over-bed table, bed linen, IV pump)

e. Before caring for patients with severe neutropenia or other forms of severe immune suppression

f. Before putting on sterile gloves and before inserting indwelling urinary catheters, peripheral vascular catheters, or other invasive devices

Instruct patients and visitors about the proper technique and times for hand hygiene. Teaching hand hygiene is particularly important if health care is to continue at home. Patients need to wash their hands before eating or handling food; after handling contaminated equipment, linen, or organic material; and after elimination. Encourage visitors to wash their hands before eating or handling food; after coming in contact with infected patients; and after handling contaminated equipment, patient furniture, or organic material (Gould et al., 2011).

You are responsible for providing the patient with a safe environment. Many hospitals are encouraging patients to follow the recommendations of The Joint Commission’s “Speak Up” campaign. The Joint Commission, together with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, launched a national campaign in 2002 to urge patients to take a role in preventing health care errors by becoming active, involved, and informed participants on the health care team. The program features brochures, posters, and buttons on a variety of patient safety topics. One recommendation is to have patients speak up to be sure the health care provider has cleaned his or her hands or wears gloves.

The effectiveness of infection prevention practices depends on the conscientiousness and consistency in using effective aseptic technique by all health care providers. It is human nature to forget key procedural steps or, when hurried, to take shortcuts that break aseptic procedures. However, failure to comply with basic procedures places the patient at risk for an infection that can seriously impair recovery or lead to death.

Cleaning, Disinfection, and Sterilization

Proper cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization of contaminated objects significantly reduce and often eliminate microorganisms. In health care facilities a sterile processing department is responsible for the disinfection and sterilization of reusable supplies and equipment. However, in the home care setting sometimes the nurse has to perform these functions. Many principles of cleaning and disinfection also apply to the home.

Cleaning: Cleaning is the removal of all soil (e.g., organic and inorganic material) from objects and surfaces (Rutala and Weber, 2008, 2009). Generally cleaning involves use of water and mechanical action with detergents or enzymatic products. When an object comes in contact with an infectious or potentially infectious material, it is contaminated. If the object is disposable, it is discarded. Reusable objects need to be cleaned thoroughly before reuse and then either disinfected or sterilized according to manufacturer recommendations. Failure to follow manufacturer recommendations transfers liability from the manufacturer to the health care facility or agency if an infection results from improper processing.

Apply protective eyewear (or a face shield) and utility (dishwashing style) gloves when cleaning equipment that is soiled by organic material such as blood, fecal matter, mucus, or pus. Protective barriers provide protection from potentially infectious organisms. A brush and detergent or soap are necessary for cleaning. The following steps ensure that an object is clean:

1. Rinse contaminated object or article with cold running water to remove organic material. Hot water causes the protein in organic material to coagulate and stick to objects, making removal difficult.

2. After rinsing, wash the object with soap and warm water. Soap or detergent reduces the surface tension of water and emulsifies dirt or remaining material. Rinse the object thoroughly.

3. Use a brush to remove dirt or material in grooves or seams. Friction dislodges contaminated material for easy removal. Open hinged items for cleaning.

4. Rinse the object in warm water.

5. Dry the object and prepare it for disinfection or sterilization if indicated by classification of the item—critical, semicritical, or noncritical.

6. The brush, gloves, and sink used to clean the equipment are considered contaminated and are cleaned and dried according to policy.

Disinfection and Sterilization: Disinfection describes a process that eliminates many or all microorganisms, with the exception of bacterial spores, from inanimate objects (Rutala and Weber, 2008, 2009). There are two types of disinfection: the disinfection of surfaces and high-level disinfection, which is required for some patient care items such as endoscopes and bronchoscopes. You accomplish disinfection using a chemical disinfectant or wet pasteurization (used for respiratory therapy equipment). Examples of disinfectants are alcohols, chlorines, glutaraldehydes, hydrogen peroxide, and phenols. Glutaraldehydes are caustic and toxic to tissues and pose a potential health risk. Sterilization is the complete elimination or destruction of all microorganisms, including spores. Steam under pressure, ethylene oxide (ETO) gas, hydrogen peroxide plasma, and chemicals are the most common sterilizing agents. ETO poses a potential health risk to staff processing with this agent, and exposure must be monitored.

The decision to clean, clean and disinfect, or sterilize depends on the intended use of the item. There are three categories of device classification (Box 28-9). Be familiar with the health care facility or agency policy and procedures for cleaning, handling, and delivering care items for eventual disinfection and sterilization. Workers in the central processing area who are specially trained in disinfection and sterilization perform most of the procedures. The following factors influence the efficacy of the disinfecting or sterilizing method:

• Concentration of solution and duration of contact—A weakened concentration or shortened exposure time lessens its effectiveness.

• Type and number of pathogens—The greater the number of pathogens on an object, the longer the required disinfecting time.

• Surface areas to treat—All dirty surfaces and areas need to be fully exposed to disinfecting and sterilizing agents. The type of surface is an important factor. Is the surface porous or nonporous?

• Temperature of the environment—Disinfectants tend to work best at room temperature.

• Presence of soap—Soap causes certain disinfectants to be ineffective. Thorough rinsing of an object is necessary before disinfecting.

• Presence of organic materials—Disinfectants become inactivated unless blood, saliva, pus, or body excretions are washed off.

Table 28-5 lists processes for disinfection and sterilization and their characteristics. Some delicate instruments requiring sterilization cannot tolerate steam and must be processed using gas or plasma.

TABLE 28-5

Examples of Disinfection and Sterilization Processes

| CHARACTERISTICS | EXAMPLES OF USE |

| Moist Heat | |

| Steam is moist heat under pressure. When exposed to high pressure, water vapor reaches temperature above boiling point to kill pathogens and spores. | Autoclave sterilizes heat-tolerant surgical instruments and semicritical patient care items. |

| Chemical Sterilants—High-Level Disinfection (HLD) | |

| A number of chemical disinfectants are used in health care. These include alcohols, chlorines, formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, hydrogen peroxide, iodophors, phenolics, and quaternary ammonium compounds. Each product performs in a unique manner and is used for a specific purpose. | Chemicals disinfect heat-sensitive instruments and equipment such as endoscopes, respiratory therapy equipment. |

| Ethylene Oxide (ETO) Gas | |

| This gas destroys spores and microorganisms by altering metabolic processes of cells. Fumes are released within an autoclave-like chamber. Ethylene oxide gas is toxic to humans, and aeration time varies with products. | This gas sterilizes most medical materials. |

| Boiling Water | |

| Boiling is least expensive for use in home. Bacterial spores and some viruses resist boiling. It is not used in health care facilities. | Commonly used in the home for items such as urinary catheters, suction tubes, and drainage collection devices. |

Infection Prevention and Control—Patient Safety

Effective prevention and control of infection requires you to remain aware of the modes of transmission and ways to control them (Box 28-10). In the hospital, home, or extended care facility a patient needs a personal set of care items. Sharing bedpans, urinals, bath basins, and eating utensils easily leads to cross-infection. In facilities where health care–associated diarrhea occurs, electronic thermometers are not recommended for rectal temperatures. You usually use oral or tympanic thermometers to assess temperature (Ackley and Ladwig, 2011). Do not use electronic thermometers for patients on contact isolation.

Always be careful when handling exudate such as urine, feces, emesis, and blood. Contaminated fluids easily splash while being discarded in toilets or hoppers. These containers need to be emptied at water level to reduce the risk of splash or splatter, and gloves and protective eyewear are worn. Appropriately dispose of disposable soiled items in trash bags. Dispose of items contaminated with large amounts of blood in biohazard bags. Check the location of the biohazard bags because it varies depending on the health care facility. Handle laboratory specimens from all patients as if they were infectious and place them in designated biohazard containers or bags for transport or disposal.

Even though there is no science to show that medical waste poses a health risk, you need to be aware of the state regulations for the handling and disposal of medical (infectious) waste. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations address the handling and disposal of blood and body fluids that potentially pose a risk for the transmission of bloodborne pathogens. These regulations defer to state laws and regulations (OSHA, 2001a).

To control organisms exiting via the respiratory tract, cover your mouth or nose when coughing or sneezing. Teach patients, health care staff, patient’s families, and visitors respiratory hygiene or cough etiquette (Table 28-6). The use of posters and written material explaining cough etiquette to learners is beneficial. Cough etiquette has become more important because of concerns for transmission of respiratory infections such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and H1N1 influenza (CDC, 2005a, 2007, 2010b). The elements of a respiratory hygiene or cough etiquette include (1) covering your nose/mouth with a tissue when you cough and promptly disposing of the contaminated tissue; (2) placing a surgical mask on a patient if it does not compromise respiratory function or is applicable, which may not be feasible in pediatric populations; (3) hand hygiene after contact with contaminated respiratory secretions; and (4) spatial separation greater than 3 feet from persons with respiratory infections (CDC, 2007).

TABLE 28-6

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Isolation Guidelines

MRSA, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococcus.

Modified from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hospital Infection Control Practice Advisory Committee: Guidelines for isolation precautions in hospitals, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 57/RR-16:39, 2007.

Health care personnel with upper respiratory tract infections are often placed on work restriction. Working when ill poses an additional risk to patients and co-workers. Work restriction for non–work-related illness requires the use of sick time. Work-related illness or exposures are covered by workers’ compensation. Employee health and infection prevention and control services are often responsible for ensuring compliance with these guidelines.

To prevent transmission of microorganisms through indirect contact, you keep soiled items and equipment from touching your clothing. A common error is to carry dirty linen in the arms against the uniform. Use fluid-resistant linen bags or carry soiled linen with hands held out from the body. Cover laundry hampers and empty them before they become overloaded.

Many measures that control the exit of microorganisms likewise control the entrance of pathogens. Maintaining the integrity of skin and mucous membranes reduces the chances of microorganisms reaching a host. Keep the patient’s skin well lubricated by using lotion as appropriate. Patients who are immobilized and debilitated are particularly susceptible to skin breakdown. Do not position patients on tubes or objects that cause breaks in the skin. Dry, wrinkle-free linen reduces the chances of skin breakdown. It is important to turn and position patients before their skin becomes reddened. Frequent oral hygiene prevents drying of mucous membranes. A water-soluble ointment keeps the patient’s lips well lubricated.

After elimination instruct women to clean the rectum and perineum by wiping from the urinary meatus toward the rectum. Cleaning in a direction from the least to the most contaminated area helps reduce genitourinary infections. Meticulous and frequent perineal care is especially important in older adult women who wear disposable incontinence pads.

Another cause for entrance of microorganisms into a host is improper handling and management of urinary catheters and drainage sets (see Chapter 45). Keep the point of connection between a catheter and drainage tube closed and intact. As long as such systems are closed, their contents are considered sterile. Outflow spigots on drainage bags should also remain closed to prevent entrance of bacteria. Minimize movement of the catheter at the urethra by stabilizing it with tape or a securing device to reduce chances of microorganisms ascending the urethra into the bladder. Do not share urine-measuring containers among patients. Perform hand hygiene when caring for urinary drainage systems. Sometimes you care for patients with closed drainage systems that collect wound drainage, bile, or other body fluids. Make sure that the site from which a drainage tube exits remains clear of excess moisture or accumulated drainage. Keep all tubing connected throughout use and only open drainage receptacles when it is necessary to discard or measure the volume of drainage (see Chapter 48).

As a nurse you sometimes obtain specimens from drainage tubes or IV tubing ports. Disinfect tubes and ports by scrubbing the surface with alcohol or a chlorhexidine solution for 15 seconds before entering the system.

A final method for reducing the entry of microorganisms is the technique for wound cleaning. The surgical wound is considered to be sterile. To prevent entry of microorganisms into the wound, always clean outward from a wound site. When applying an antiseptic or cleaning with soap and water, wipe around the wound edge first and then clean outward away from the wound (see Chapter 48). Use clean gauze for each revolution around the circumference of the wound. A patient’s resistance to infection improves as you protect normal body defenses against infection. Intervene to maintain the normal reparative processes of the body (Box 28-11). Nurses also protect themselves and others through the use of isolation precautions.

The risk of transmitting HAIs or infectious disease among patients is high, especially with an organism such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). When a patient has a suspected or known infection, health care workers are alerted and follow infection prevention and control practices. However, they are not always aware that patients have an infection. Body substances such as feces, saliva, mucus, and wound drainage always contain potentially infectious organisms.

Isolation and Isolation Precautions

Isolation is the separation and restriction of movement of ill persons with contagious diseases. Health care facilities are required to have the capability of isolating patients. For example, patients with suspected or confirmed active TB are usually placed in an airborne infection isolation room (CDC, 2007). However, not all communicable diseases require placing a patient in a special private room. You can conduct many isolation practices in standard rooms using barrier precautions.

Barrier precautions include the appropriate use of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gowns, gloves, masks, eyewear, and other protective devices or clothing. The choice of barriers depends on the task being performed. Barrier protection applies to all patients because every patient has the potential to transmit infection via blood and body fluids and the risk for infection transmission is unknown. The CDC issued new isolation guidelines in 2007 that build on the two-tiered approach established in the 1996 guidelines.

The first and most important tier is standard precautions. The second tier addresses isolation precautions, which are based on the mode of transmission of a disease (see Table 28-6). Isolation precautions are termed airborne, droplet, contact, and protective environment. The precautions are for patients with highly transmissible pathogens. The protective environment category is designed for patients who have undergone transplants and gene therapy (CDC, 2007).

• Contact precautions: Used for direct and indirect contact with patients and their environment. Direct contact refers to the care and handling of contaminated body fluids. An example includes blood or other body fluids from an infected patient that enter the health care worker’s body through direct contact with compromised skin or mucous membranes. Indirect contact involves the transfer of an infectious agent through a contaminated intermediate object such as contaminated instruments or hands of health care workers. The health care worker may transmit microorganisms from one patient site to another if hand hygiene is not performed between patients (CDC, 2007).

• Droplet precautions: Focus on diseases that are transmitted by large droplets expelled into the air and travel 3 to 6 feet from the patient. Droplet precautions require the wearing of a surgical mask when within 3 feet of the patient, proper hand hygiene, and some dedicated-care equipment. An example is a patient with influenza.

• Airborne precautions: Focus on diseases that are transmitted by smaller droplets, which remain in the air for longer periods of time. This requires a specially equipped room with a negative air flow referred to as an airborne infection isolation room. Air is not returned to the inside ventilation system but is filtered through a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter and exhausted directly to the outside. All health care personnel wear an N95 respirator every time they enter the room.

• Protective environment: Focuses on a very limited patient population. This form of isolation requires a specialized room with positive airflow. The airflow rate is set at greater than 12 air exchanges per hour, and all air is filtered through a HEPA filter. Patients are not allowed to have dried or fresh flowers or potted plants in these rooms (CDC, 2007).

• When using the isolation guidelines of the CDC, refer to additional CDC documents to prevent health care–associated aspergillosis and Legionnaires’ disease in immunocompromised patients and the spread of multidrug-resistant organisms (CDC, 2007).

Regardless of the type of isolation system, follow these basic principles:

• Use thorough hand hygiene before entering and leaving the room of a patient in isolation.

• Dispose of contaminated supplies and equipment in a manner that prevents spread of microorganisms to other persons as indicated by the mode of transmission of the organism.

• Apply knowledge of a disease process and the mode of infection transmission when using protective barriers.

• Protect all persons who might be exposed during transport of a patient outside the isolation room.

Psychological Implications of Isolation: When a patient requires isolation in a private room, a sense of loneliness sometimes develops because normal social relationships become disrupted. This situation can be psychologically harmful, especially for children. A recent study noted that patients in isolation suffered more depression and anxiety and were less satisfied with their care (Abad et al., 2010). Patients’ body images become altered as a result of the infectious process. Some feel unclean, rejected, lonely, or guilty. Infection prevention and control practices further intensify these beliefs of difference or undesirability. Isolation disrupts normal social relationships with visitors and caregivers. Take the opportunity to listen to a patient’s concerns or interests. If you rush care or show a lack of interest in a patient’s needs, he or she feels rejected and even more isolated.

Before you institute isolation measures, the patient and family need to understand the nature of the disease or condition, the purposes of isolation, and steps for carrying out specific precautions. If they are able to participate in maintaining infection prevention and control practices, the chances of reducing the spread of infection increase. Teach the patient and family to perform hand hygiene and use barrier protection if appropriate. Demonstrate each procedure; be sure to give the patient and family an opportunity for practice. It is also important to explain how infectious organisms are transmitted so the patient and family understand the difference between contaminated and clean objects. Explaining and demonstrating these procedures, especially hand hygiene, helps the family to consistently practice correct hand hygiene and prescribed isolation measures (Gould et al., 2011).

Take measures to improve the patient’s sensory stimulation during isolation. Make sure that the room environment is clean and pleasant. Open drapes or shades and remove excess supplies and equipment. Listen to the patient’s concerns or interests. Mealtime is a particularly good opportunity for conversation. Providing comfort measures such as repositioning, a back massage, or a warm sponge bath increase physical stimulation. Depending on the patient’s condition, encourage him or her to walk around the room or sit up in a chair. Recreational activities such as board games or cards are an option to keep the patient mentally stimulated.

Explain to the family the patient’s risk for depression or loneliness (Abad et al., 2010). Encourage visiting family members to avoid expressions or actions that convey revulsion or disgust related to infection prevention and control practices. Discuss ways to provide meaningful stimulation.

The Isolation Environment: Private rooms used for isolation sometimes provide negative-pressure airflow to prevent infectious particles from flowing out of a room to other rooms and the air handling system. Special rooms with positive-pressure airflow are also used for highly susceptible immunocompromised patients such as recipients of transplanted organs. On the door or wall outside the room the nurse posts a card listing precautions for the isolation category in use according to health care facility policy. The card is a handy reference for health care personnel and visitors and alerts anyone who might enter the room accidentally that special precautions must be followed.

The isolation room or an adjoining anteroom needs to contain hand hygiene and PPE supplies. Soap and antiseptic (antimicrobial) solutions need to be available. Personnel and visitors perform hand hygiene before approaching the patient’s bedside and again before leaving the room. If toilet facilities are unavailable, there are special procedures for handling portable commodes, bedpans, or urinals.

All patient care rooms, including those used for isolation; contain an impervious bag for soiled or contaminated linen and a trash container with plastic liners. Impervious receptacles prevent transmission of microorganisms by preventing leaking and soiling of the outside surface. A disposable rigid container needs to be available in the room to discard used sharps such as safety needles and syringes.

Remain aware of infection prevention and control techniques while working with patients in protected environments. You need to feel comfortable performing all procedures and yet remain conscious of infection prevention and control principles. Depending on the microorganism and mode of transmission, evaluate which articles or equipment to take into an isolation room. For example, the CDC (2007) recommends the dedicated use of articles such as stethoscopes, sphygmomanometers, or rectal thermometers in the isolation room of a patient infected or colonized with vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Do not use these devices on other patients unless they are first adequately cleaned and disinfected. Box 28-12 describes the procedures to perform when using shared equipment.

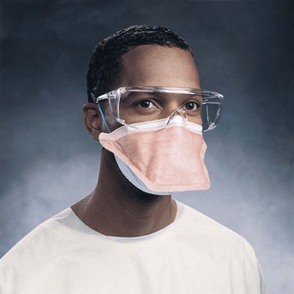

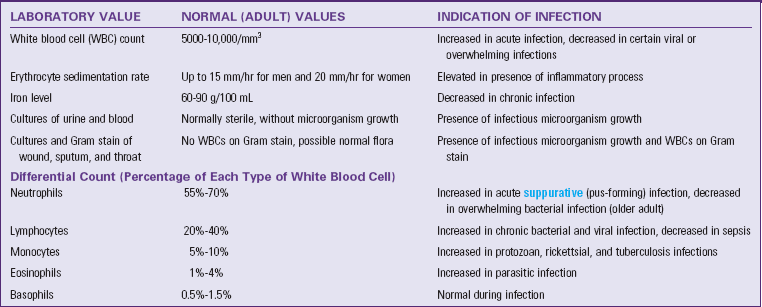

Personal Protective Equipment: PPE, specialized clothing or equipment worn by a health care worker for protection against infectious materials (gowns, masks or respirators, protective eyewear, and gloves), should be readily available for personnel performing patient care (CDC, 2004). The equipment to be used is task based.

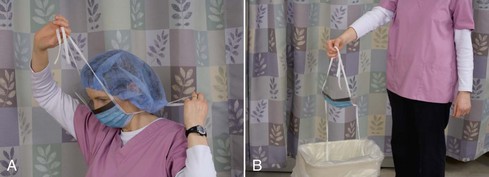

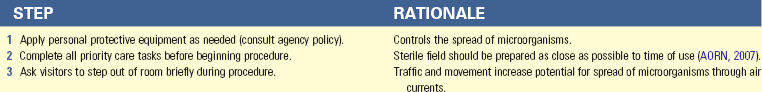

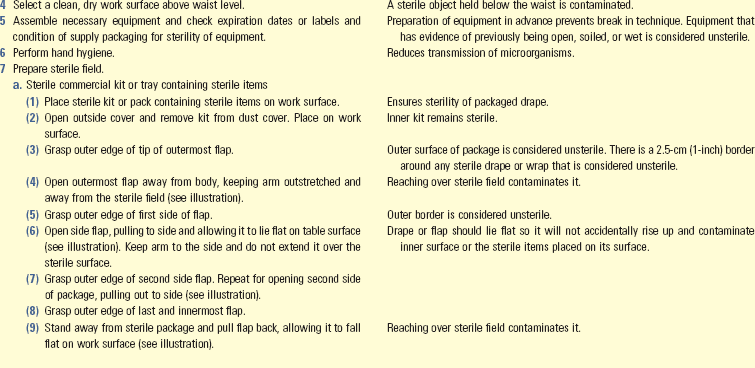

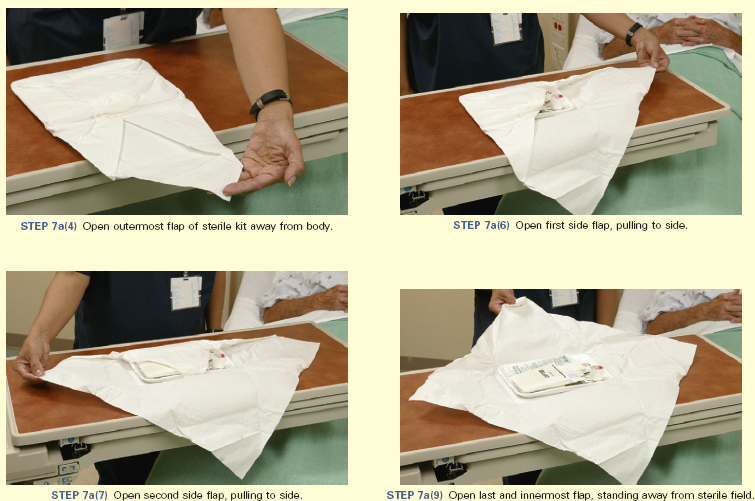

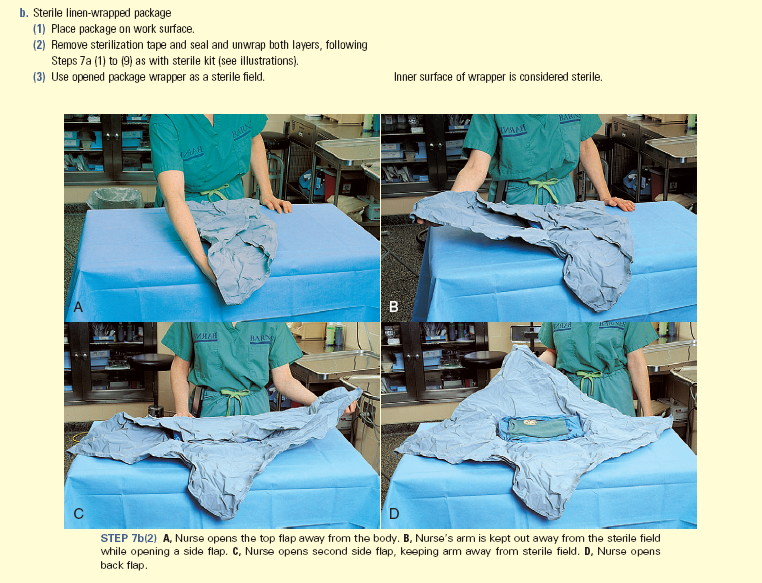

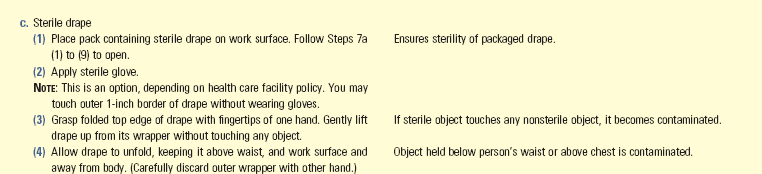

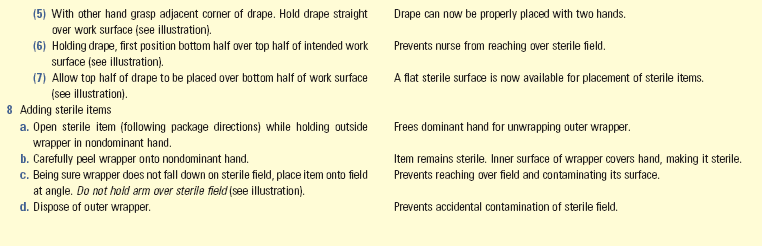

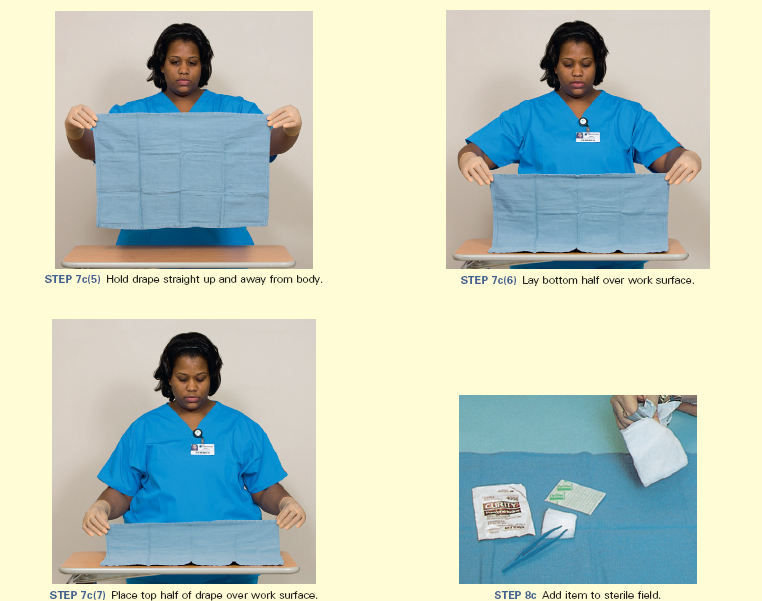

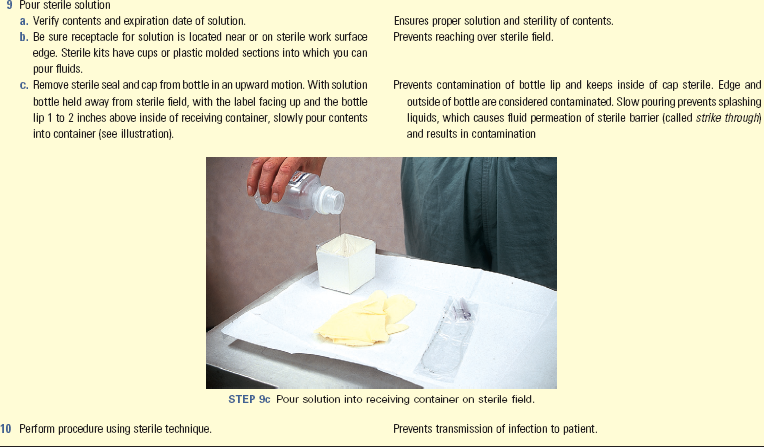

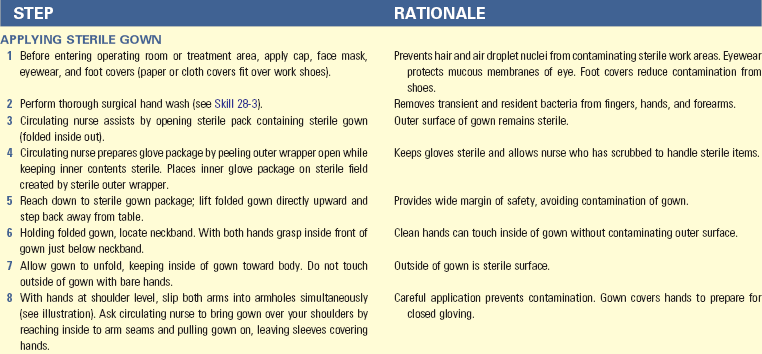

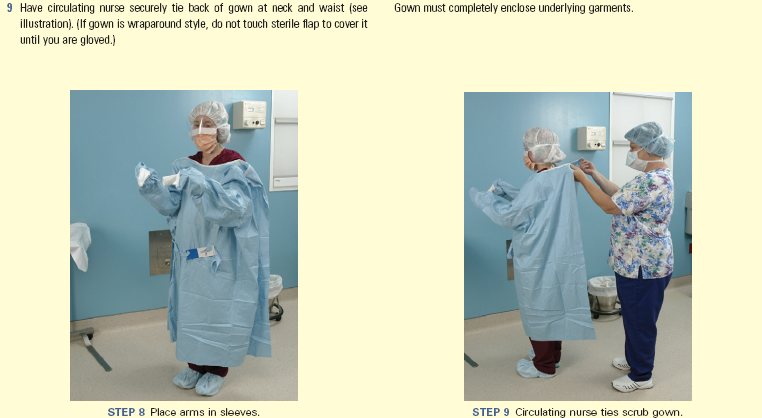

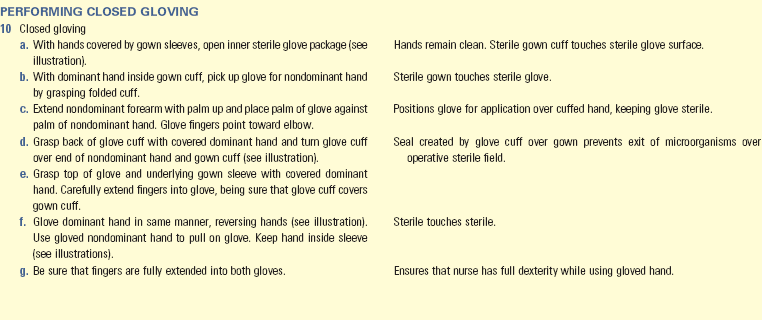

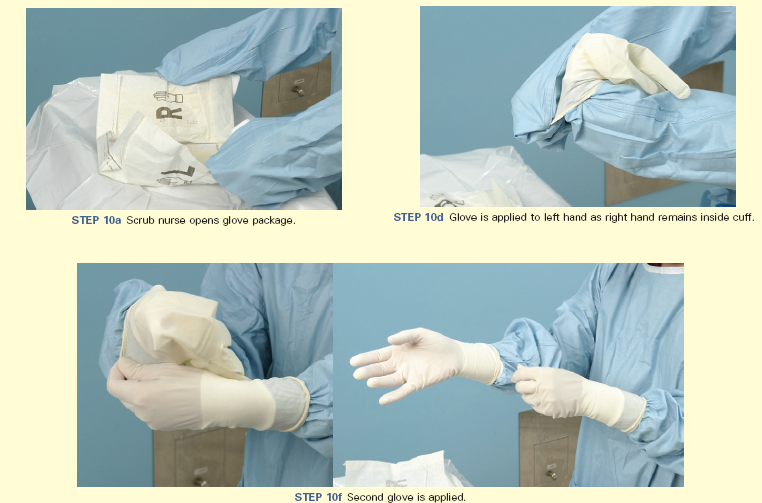

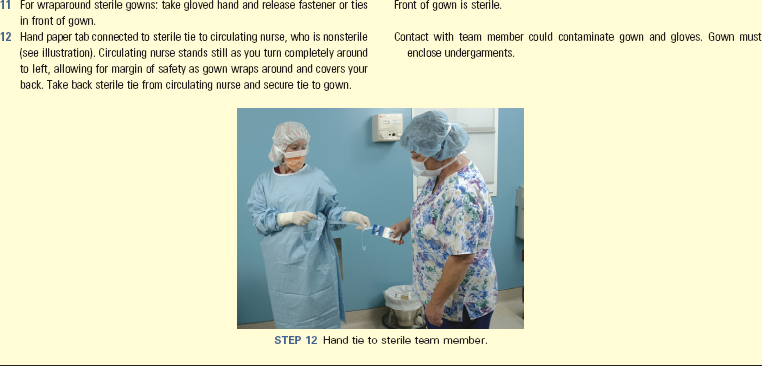

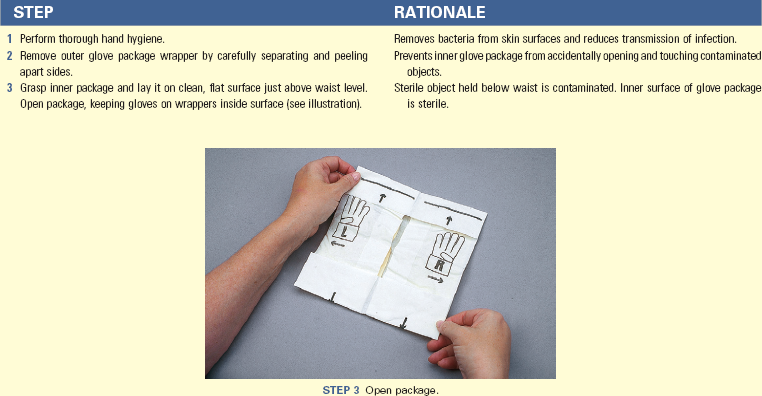

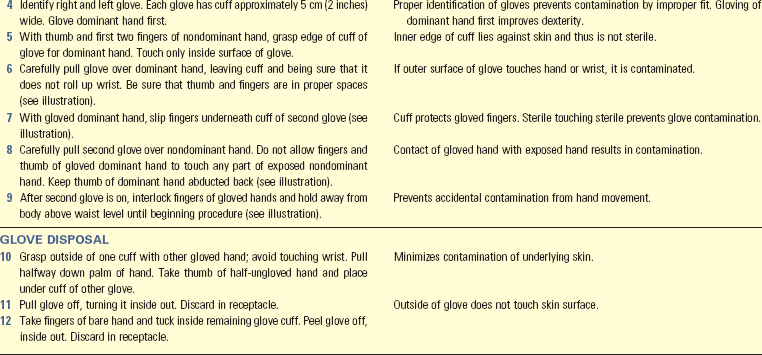

Gowns: The primary reason for gowning is to prevent soiling clothes during contact with a patient. Gowns or cover-ups protect health care personnel and visitors from coming in contact with infected material and blood or body fluids. Gowns are often required depending on the expected amount of exposure to infectious material. Gowns used for barrier protection are made of a fluid-resistant material. Change gowns immediately if damaged or heavily contaminated. Isolation gowns are disposable or reusable.