Skin Integrity and Wound Care

• Discuss the risk factors that contribute to pressure ulcer formation.

• Describe the pressure ulcer staging system.

• Discuss the normal process of wound healing.

• Describe the differences of wound healing by primary and secondary intention.

• Describe complications of wound healing.

• Explain the factors that impede or promote wound healing.

• Describe the differences between nursing care of acute and chronic wounds.

• Complete an assessment for a patient with impaired skin integrity.

• List nursing diagnoses associated with impaired skin integrity.

• Develop a nursing care plan for a patient with impaired skin integrity.

• List appropriate nursing interventions for a patient with impaired skin integrity.

• State evaluation criteria for a patient with impaired skin integrity.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Skin, the largest organ in the body, constitutes 15% of the total adult body weight (Wysocki, 2012). It is a protective barrier against disease-causing organisms and a sensory organ for pain, temperature, and touch; and it synthesizes vitamin D. Injury to the skin poses risks to safety and triggers a complex healing response. A nurse’s most important responsibilities include assessing and monitoring skin integrity; identifying problems; and planning, implementing, and evaluating interventions to maintain skin integrity. Once a wound occurs, it is critical to know the process of normal wound healing to identify the appropriate nursing interventions.

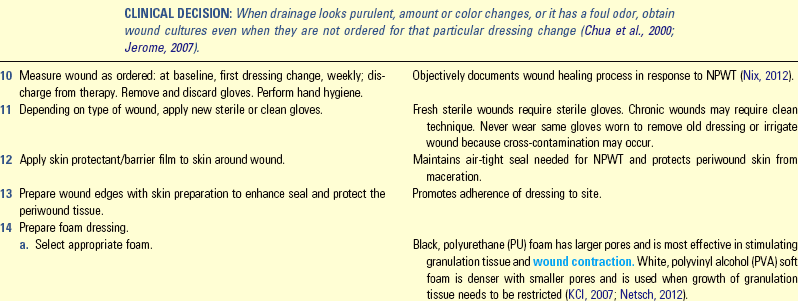

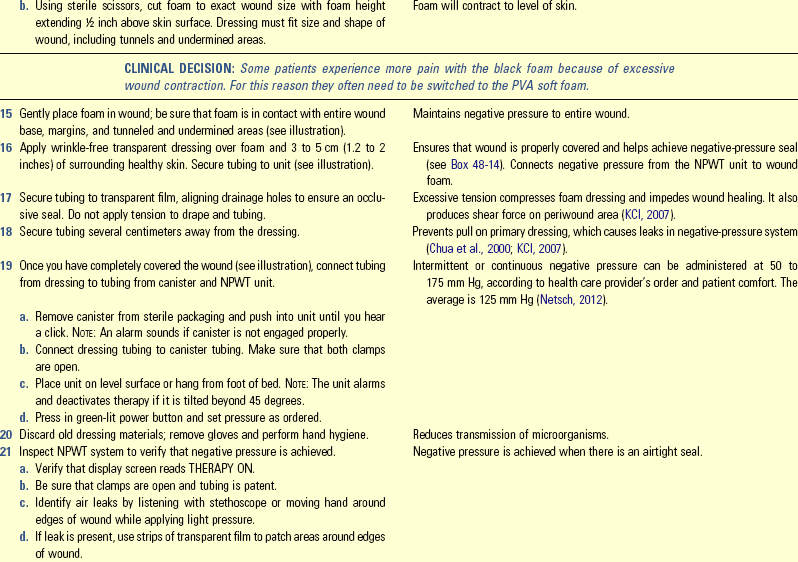

Scientific Knowledge Base

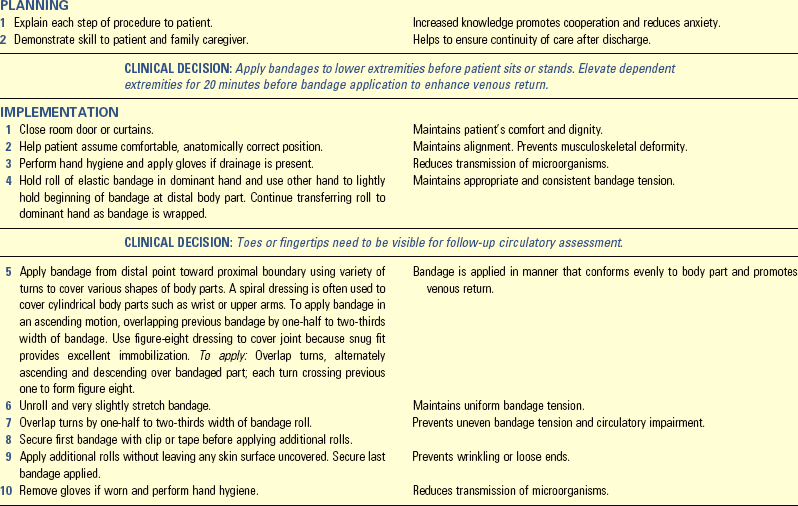

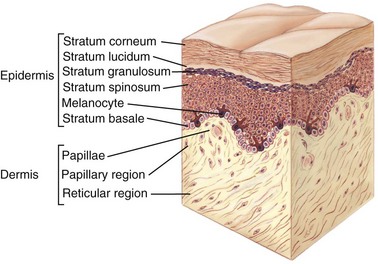

The skin has two layers: the epidermis and the dermis (Fig. 48-1). They are separated by a membrane, often referred to as the dermal-epidermal junction. The epidermis, or the top layer, has several layers. The stratum corneum is the thin, outermost layer of the epidermis. It consists of flattened, dead, keratinized cells. The cells originate from the innermost epidermal layer, commonly called the basal layer. Cells in the basal layer divide, proliferate, and migrate toward the epidermal surface. After they reach the stratum corneum, they flatten and die. This constant movement ensures replacement of surface cells sloughed during normal desquamation or shedding. The thin stratum corneum protects underlying cells and tissues from dehydration and prevents entrance of certain chemical agents. The stratum corneum allows evaporation of water from the skin and permits absorption of certain topical medications.

FIG. 48-1 Layers of skin. (From Applegate E: The anatomy and physiology learning system, ed 3, St Louis, 2006, Saunders.)

The dermis, the inner layer of the skin, provides tensile strength, mechanical support, and protection to the underlying muscles, bones, and organs. It differs from the epidermis in that it contains mostly connective tissue and few skin cells. Collagen (a tough, fibrous protein), blood vessels, and nerves are found in the dermal layer. Fibroblasts, which are responsible for collagen formation, are the only distinctive cell type within the dermis.

Understanding skin structure helps you maintain skin integrity and promote wound healing. Intact skin protects the patient from chemical and mechanical injury. When the skin is injured, the epidermis functions to resurface the wound and restore the barrier against invading organisms while the dermis responds to restore the structural integrity (collagen) and the physical properties of the skin. The normal aging process alters skin characteristics and makes skin more vulnerable to damage. Box 48-1 provides a summary of the changes in aging skin.

Pressure Ulcers

Pressure ulcer, pressure sore, decubitus ulcer, and bedsore are terms used to describe impaired skin integrity related to unrelieved, prolonged pressure. The most current terminology is pressure ulcer (Fig. 48-2), which is consistent with the recommendations of the pressure ulcer guidelines written by the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN, 2010). A pressure ulcer is localized injury to the skin and other underlying tissue, usually over a body prominence, as a result of pressure or pressure in combination with shear and/or friction. A number of contributing factors are also associated with pressure ulcers; the significance of these factors is yet to be elucidated (EPUAP and NPUAP, 2009). Any patient experiencing decreased mobility, decreased sensory perception, fecal or urinary incontinence, and/or poor nutrition is at risk for pressure ulcer development.

Many factors contribute to the formation of a pressure ulcer. Pressure is the major cause. Tissues receive oxygen and nutrients and eliminate metabolic wastes via the blood. Any factor that interferes with blood flow in turn interferes with cellular metabolism and the function or life of the cells. Prolonged, intense pressure affects cellular metabolism by decreasing or obliterating blood flow, resulting in tissue ischemia and ultimately tissue death.

Pathogenesis of Pressure Ulcers

Pressure is the major element in the cause of pressure ulcers. Three pressure-related factors contribute to pressure ulcer development: (1) pressure intensity, (2) pressure duration, and (3) tissue tolerance.

Pressure Intensity: A classic research study identified capillary closing pressure as the minimal amount of pressure required to collapse a capillary (e.g., when the pressure exceeds the normal capillary pressure range of 15 to 32 mm Hg) (Burton and Yamada, 1951). Therefore, if the pressure applied over a capillary exceeds the normal capillary pressure and the vessel is occluded for a prolonged period of time, tissue ischemia can occur. If the patient has reduced sensation and cannot respond to the discomfort of the ischemia, tissue ischemia and tissue death result.

The clinical presentation of obstructed blood flow occurs when evaluating areas of pressure. After a period of tissue ischemia, if the pressure is relieved and the blood flow returns, the skin turns red. The effect of this redness is vasodilation (blood vessel expansion), called hyperemia (redness). Evaluate an area of hyperemia by pressing a finger over the affected area. If it blanches (turns lighter in color) and the erythema returns when you remove your finger, the hyperemia is transient and is an attempt to overcome the ischemic episode, thus called blanching hyperemia (Pieper, 2012). However, if the erythematous area does not blanch (nonblanching erythema) when you apply pressure, deep tissue damage is probable.

Blanching occurs when the normal red tones of the light-skinned patient are absent. It does not occur in patients with darkly pigmented skin. The Task Force on the Implications for Darkly Pigmented Intact Skin in the Prediction and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers (Bennett, 1995) defined darkly pigmented skin as skin that “remains unchanged (does not blanch) when pressure is applied over a bony prominence, irrespective of the patient’s race or ethnicity.” Characteristics of intact dark skin that alert nurses to the potential for pressure ulcers are in Box 48-2.

Pressure Duration: Low pressure over a prolonged period and high-intensity pressure over a short period are two concerns related to duration of pressure. Both types of pressure cause tissue damage. Extended pressure occludes blood flow and nutrients and contributes to cell death (Pieper, 2012). Clinical implications of pressure duration include evaluating the amount of pressure (checking skin for reactive hyperemia) and determining the amount of time that a patient tolerates pressure (checking to be sure after relieving pressure that the affected area blanches).

Tissue Tolerance: The ability of tissue to endure pressure depends on the integrity of the tissue and the supporting structures. The extrinsic factors of shear, friction, and moisture affect the ability of the skin to tolerate pressure: the greater the degree to which the factors of shear, friction, and moisture are present, the more susceptible the skin will be to damage from pressure. The second factor related to tissue tolerance is the ability of the underlying skin structures (blood vessels, collagen) to assist in redistributing pressure. Systemic factors such as poor nutrition, increased aging, hydration status, and low blood pressure affect the tolerance of the tissue to externally applied pressure.

Risk Factors for Pressure Ulcer Development

A variety of factors predispose a patient to pressure ulcer formation. These factors are often directly related to disease such as decreased level of consciousness, the presence of a cast, or secondary to an illness (e.g., decreased sensation following a cerebrovascular accident).

Impaired Sensory Perception: Patients with altered sensory perception for pain and pressure are more at risk for impaired skin integrity than those with normal sensation. Patients with impaired sensory perception of pain and pressure are unable to feel when a portion of their body undergoes increased, prolonged pressure or pain. Thus the patient who can’t feel or sense that there is pain or pressure is at risk for the development of pressure ulcers.

Impaired Mobility: Patients unable to independently change positions are at risk for pressure ulcer development. For example, patients with spinal cord injuries have decreased or absent motor and sensory impairment and are unable to reposition off bony prominences.

Alteration in Level of Consciousness: Patients who are confused or disoriented and those who have expressive aphasia or other inability to verbalize or changing levels of consciousness are unable to protect themselves from pressure ulcer development. Patients who are confused or disoriented are sometimes able to feel pressure but are not always able to understand how to relieve it or communicate their discomfort. Patients in a coma cannot perceive pressure and are unable to move voluntarily to relieve pressure.

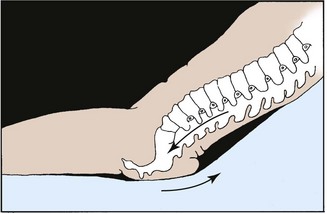

Shear: Shear force is the sliding movement of skin and subcutaneous tissue while the underlying muscle and bone are stationary (Bryant, 2012). For example, shear force occurs when the head of the bed is elevated and the sliding of the skeleton starts but the skin is fixed because of friction with the bed (Fig. 48-3). It also occurs when transferring a patient from bed to stretcher and the patient’s skin is pulled across the bed. When shear is present, the skin and subcutaneous layers adhere to the surface of the bed, and the layers of muscle and the bones slide in the direction of body movement. The underlying tissue capillaries are stretched and angulated by the shear force. As a result, necrosis occurs deep within the tissue layers. The tissue damage occurs deep in the tissues, causing undermining of the dermis.

Friction: The force of two surfaces moving across one another such as the mechanical force exerted when skin is dragged across a coarse surface such as bed linens is called friction (WOCN, 2010). Unlike shear injuries, friction injuries affect the epidermis or top layer of the skin. The denuded skin appears red and painful and is sometimes referred to as a “sheet burn.” A friction injury occurs in patients who are restless, in those who have uncontrollable movements such as spastic conditions, and in those whose skin is dragged rather than lifted from the bed surface during position changes.

Moisture: The presence and duration of moisture on the skin increases the risk of ulcer formation. Moisture reduces the resistance of the skin to other physical factors such as pressure and/or shear force. Prolonged moisture softens skin, making it more susceptible to damage. Immobilized patients who are unable to perform their own hygiene needs depend on the nurse to keep the skin dry and intact. Skin moisture originates from wound drainage, excessive perspiration, and fecal or urinary incontinence.

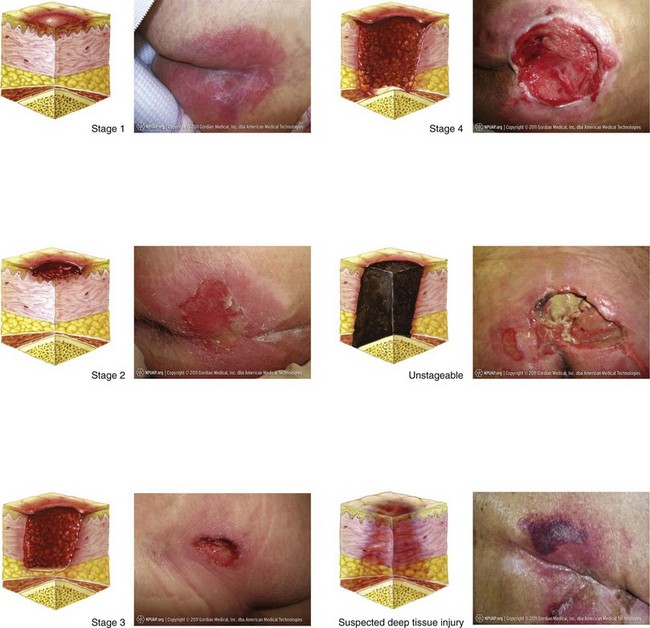

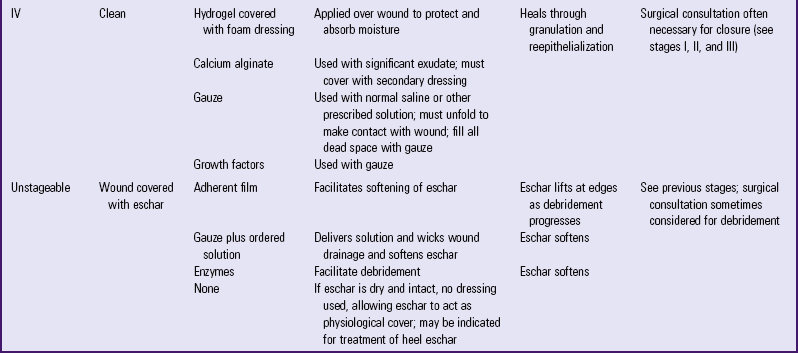

Classification of Pressure Ulcers

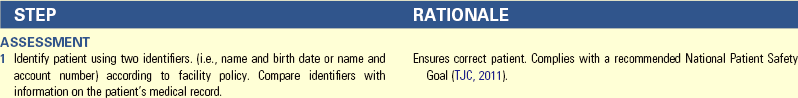

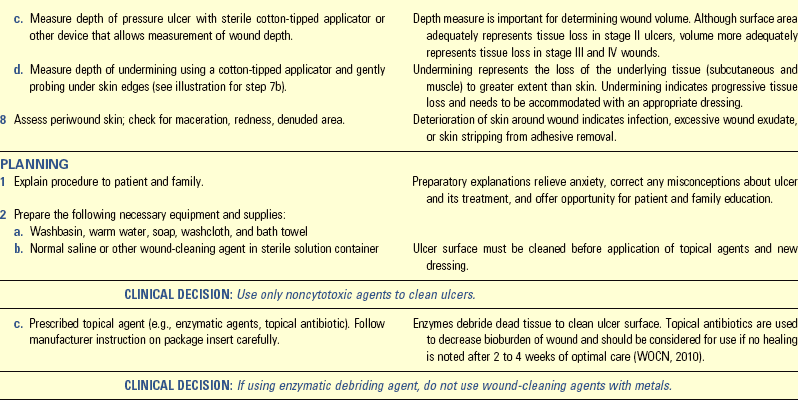

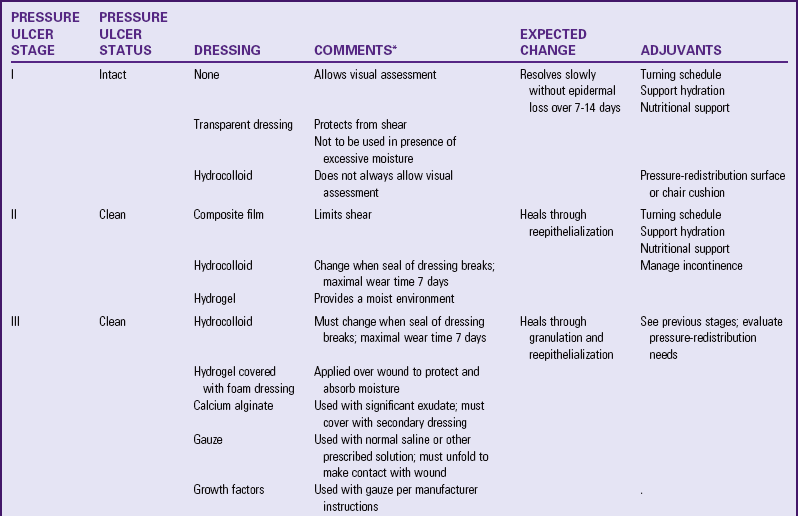

You need to assess pressure ulcers at regular intervals using systematic parameters to evaluate wound healing, plan appropriate interventions, and evaluate progress. Assessment includes depth of tissue involvement (staging), type and approximate percentage of tissue in wound bed, wound dimensions, exudate description, and condition of surrounding skin.

One method for assessment of a pressure ulcer is the use of a staging system. Staging systems for pressure ulcers are based on describing the depth of tissue destroyed. Accurate staging requires knowledge of the skin layers. A major drawback of a staging system is that you cannot stage an ulcer covered with necrotic tissue because the necrotic tissue is covering the depth of the ulcer. The necrotic tissue must be debrided or removed to expose the wound base to allow for assessment.

Pressure ulcer staging describes the pressure ulcer depth at the point of assessment. Thus, once you have staged the pressure ulcer, this stage endures even as it heals. Pressure ulcers do not progress from a stage III to a stage I; rather, a stage III ulcer demonstrating signs of healing is described as a healing stage III pressure ulcer (Pieper, 2012). The EPUAP and NPUAP have developed clinical practice guidelines for pressure ulcers and have advanced the following classification/staging system (EPUAP and NPUAP, 2009):

Stage I: Nonblanchable Redness of Intact Skin

Intact skin presents with nonblanchable erythema of a localized area usually over a bony prominence. Discoloration of the skin, warmth, edema, hardness, or pain may also be present. Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching.

Further description: The area may be painful, firm, soft, warmer, or cooler than adjacent tissue. Stage I may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. It may indicate “at-risk” persons (Fig. 48-4, A).

Stage II: Partial-thickness Skin Loss or Blister

A partial-thickness loss of dermis presents as a shallow open ulcer with a red-pink wound bed without slough. It may also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum-filled or serosangineous filled blister.

Further description: Stage II presents as a shiny or dry shallow ulcer without slough or bruising. This stage should not be used to describe skin tears, tape burns, incontinence-associated dermatitis, maceration, or excoriation (Fig. 48-4, B).

Stage III: Full-thickness Skin Loss (Fat Visible)

A stage III ulcer is a full-thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible; but bone, tendon, or muscle is not exposed. Some slough may be present. It may include undermining and tunneling.

Further description: The depth of a stage III pressure ulcer varies by anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput, and malleolus do not have (adipose) subcutaneous tissue; and stage III ulcers can be shallow. In contrast, areas of significant adiposity can develop extremely deep stage III pressure ulcers. Bone/tendon is not visible or directly palpable (Fig. 48-4, C).

Stage IV: Full-thickness Tissue Loss (Muscle/Bone Visible)

A stage IV ulcer is a full-thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon, or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present. It often includes undermining and tunneling.

Further description: The depth of a stage IV pressure ulcer varies by anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput, and malleolus do not have (adipose) subcutaneous tissue; and these ulcers can be shallow. Stage IV ulcers can extend into muscle and/or supporting structures (e.g., fascia, tendon, or joint capsule), making osteomyelitis or osteitis likely to occur. Exposed bone/muscle is visible or directly palpable (Fig. 48-4, D).

Unstageable/Unclassified: Full-thickness Skin or Tissue Loss—Depth Unknown

The EPUAP and the NPUAP (2009) developed a definition for an ulcer in which the base of the wound cannot be visualized and a definition of tissue injury in which the depth of injury is unknown. An unstageable ulcer is a full-thickness tissue loss in which actual depth of the ulcer is completely obscured by slough (yellow, tan, gray, green, or brown) and/or eschar (tan, brown, or black) in the wound bed (Fig. 48-4, E).

Further description: Until enough slough and/or eschar are removed to expose the base of the wound, the true depth cannot be determined; but it is either a stage III or IV. Stable (dry, adherent, intact without erythema or fluctuance) eschar on the heels serves as “the natural (biological) cover of the body” and should not be removed.

Suspected Deep-Tissue Injury—Depth Unknown

Suspected deep-tissue injury is a purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-filled blister caused by damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear (Fig. 48-4, F).

Further description: The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, firm, mushy, boggy, warmer, or cooler than adjacent tissue. Deep-tissue injury may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. Evolution may include a thin blister over a dark wound bed. The wound may further evolve and become covered by thin eschar. Evolution may be rapid, exposing additional layers of tissue even with treatment.

In addition, Bennett (1995) suggests that, when assessing patients with darkly pigmented skin, proper lighting is important to accurately assess the skin (see Box 48-2). Either natural light or a halogen light is recommended. This prevents the blue tones that fluorescent light sources produce on darkly pigmented skin, which interferes with accurate assessment. Additional aspects of assessing dark skin are in Box 48-3.

You need to assess the type of tissue in the wound base; this information is used to plan appropriate interventions. The assessment of tissue type includes the amount (percentage) and appearance (color) of viable and nonviable tissue. Granulation tissue is red, moist tissue composed of new blood vessels, the presence of which indicates progression toward healing. Soft yellow or white tissue is characteristic of slough (stringy substance attached to wound bed), and it must be removed by a skilled clinician before the wound is able to heal. Black or brown necrotic tissue is eschar, which also needs to be removed before healing can proceed.

The measurement of the size of the wound provides overall changes in size, which is an indicator for wound healing progress (Nix, 2012). Use disposable wound-measuring devices to obtain measurement of width and length. Select a uniform, consistent method for measuring wound length and width to facilitate meaningful comparisons of wound measurements across time (EPUAP and NPUAP, 2009). Measure depth by using a cotton-tipped applicator in the wound bed.

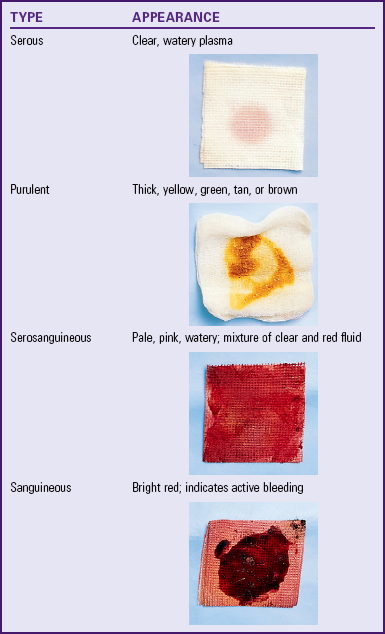

Wound exudate should describe the amount, color, consistency, and odor of wound drainage and is part of the wound assessment. Excessive exudate indicates the presence of infection. Finally, assess the condition of the skin surrounding the wound for redness, warmth, maceration, or edema (swelling). The presence of any of these factors on the skin surrounding the wound indicates wound deterioration.

The skin around the wound (periwound) should be assessed. Examine the periwound area for redness, warmth, and signs of maceration and palpate the area for signs of pain or induration.

Wound Classifications

A wound is a disruption of the integrity and function of tissues in the body (Baharestani, 2008). It is imperative for the nurse to know that all wounds are not created equal. Understanding the etiology of a wound is important because the treatment for it varies, depending on the underlying disease process.

There are many ways to classify wounds. Wound classification systems describe the status of skin integrity, cause of the wound, severity or extent of tissue injury or damage, cleanliness of the wound (Table 48-1), or descriptive qualities of the wound tissue such as color (Fig. 48-5). Wound classifications enable a nurse to understand the risks associated with a wound and implications for healing.

TABLE 48-1

| DESCRIPTION | CAUSES | IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALING |

| Onset and Duration | ||

| Acute | ||

| Wound that proceeds through an orderly and timely reparative process that results in sustained restoration of anatomical and functional integrity | Trauma, a surgical incision | Wounds are usually easily cleaned and repaired. Wound edges are clean and intact. |

| Chronic | ||

| Wound that fails to proceed through an orderly and timely process to produce anatomical and functional integrity | Vascular compromise, chronic inflammation, or repetitive insults to tissue (Doughty and Sparks-Defriese, 2012) | Continued exposure to insult impedes wound healing. |

| Healing Process | ||

| Primary Intention | ||

| Wound that is closed | Surgical incision, wound that is sutured or stapled | Healing occurs by epithelialization; heals quickly with minimal scar formation. |

| Secondary Intention | ||

| Wound edges not approximated | Pressure ulcers, surgical wounds that have tissue loss | Wound heals by granulation tissue formation, wound contraction, and epithelialization. |

| Tertiary Intention | ||

| Wound left open for several days, then wound edges are approximated (see Fig. 48-4,C) | Wounds that are contaminated and require observation for signs of inflammation | Closure of wound is delayed until risk of infection is resolved (Doughty and Sparks-Defriese, 2012). |

FIG. 48-5 Wounds classified by color assessment. A, Black wound. B, Yellow wound. C, Red wound. D, Mixed-color wound. (A and D, Courtesy Scott Health Care—A Molnlyche Company, Philadelphia, Pa; B and C from Bryant RA, Nix DP, editors: Acute and chronic wounds: current management concepts, ed 4, St Louis, 2012, Mosby.)

Process of Wound Healing

Wound healing involves integrated physiological processes. The tissue layers involved and their capacity for regeneration determine the mechanism for repair for any wound (Doughty and Sparks-Defriese, 2012).

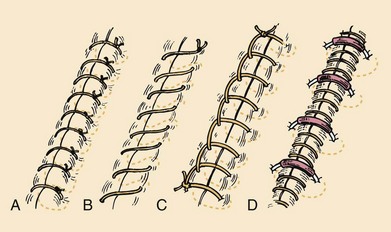

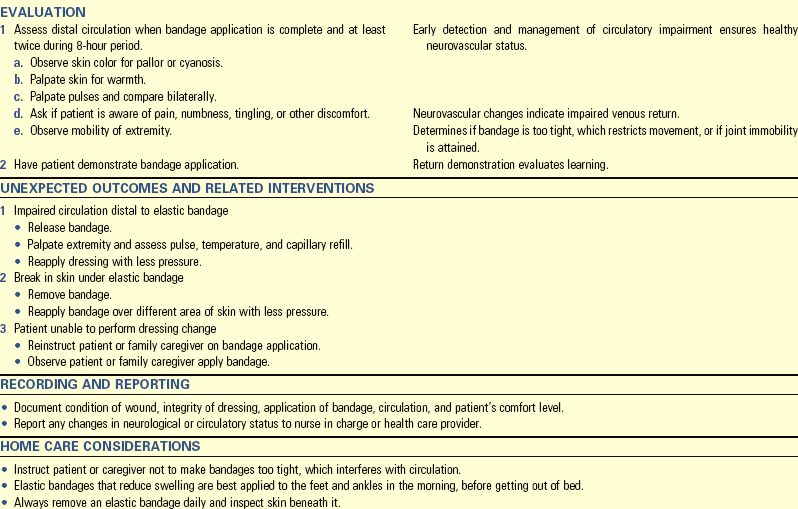

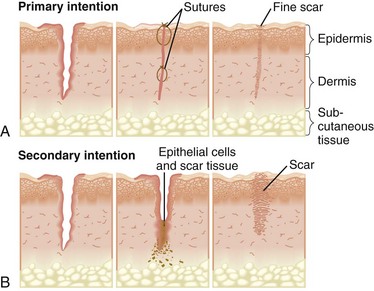

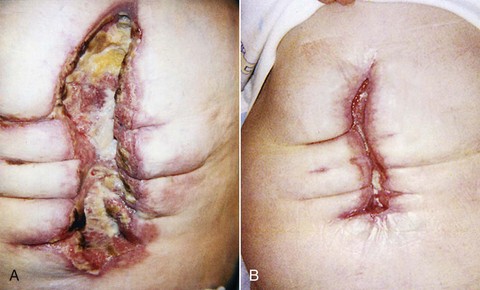

There are two types of wounds: those with loss of tissue and those without. A clean surgical incision is an example of a wound with little tissue loss. The surgical incision heals by primary intention (Fig. 48-6, A). The skin edges are approximated, or closed, and the risk of infection is low. Healing occurs quickly, with minimal scar formation, as long as infection and secondary breakdown are prevented (Doughty and Sparks-Defriese, 2012). In contrast, a wound involving loss of tissue such as a burn, pressure ulcer, or severe laceration heals by secondary intention. The wound is left open until it becomes filled by scar tissue. It takes longer for a wound to heal by secondary intention; thus the chance of infection is greater. If scarring from secondary intention is severe, loss of tissue function is often permanent (Fig. 48-6, B).

FIG. 48-6 A, Wound healing by primary intention such as a surgical incision. Wound healing edges are pulled together and approximated with sutures or staples, and healing occurs by connective tissue deposition. B, Wound healing by secondary intention. Wound edges are not approximated, and healing occurs by granulation tissue formation and contraction of the wound edges. (From Black JM, Hawks JH: Medical-surgical nursing: clinical management for positive outcomes, ed 8, St Louis, 2009, Mosby.)

Wound Repair

Partial-thickness wounds are shallow wounds involving loss of the epidermis (top layer) and possibly partial loss of the dermis. These wounds heal by regeneration because epidermis regenerates. An example of this is the repair of a clean surgical wound or an abrasion. Full-thickness wounds extending into the dermis (involving both layers of tissue) heal by scar formation because deeper structures do not regenerate. Pressure ulcers are an example of full-thickness wounds.

Partial-Thickness Wound Repair: Three components are involved in the healing process of a partial-thickness wound: inflammatory response, epithelial proliferation (reproduction) and migration, and reestablishment of the epidermal layers.

Tissue trauma causes the inflammatory response, which in turn causes redness and swelling to the area with a moderate amount of serous exudate. This response is generally limited to the first 24 hours after wounding. The epithelial cells begin to regenerate, providing new cells to replace the lost cells. The epithelial proliferation and migration start at both the wound edges and the epidermal cells lining the epidermal appendages, allowing for quick resurfacing. Epithelial cells begin to migrate across the wound bed soon after the wound occurs. A wound left open to air can resurface within 6 to 7 days, whereas one that is kept moist can resurface in 4 days. The difference in the healing rate is related to the fact that epidermal cells only migrate across a moist surface. In a dry wound the cells migrate down into a moist level before migration can occur (Doughty and Sparks-Defriese, 2012). New epithelium is only a few cells thick and must undergo reestablishment of the epidermal layers. The cells slowly reestablish normal thickness and appear as dry, pink tissue.

Full-Thickness Wound Repair: The four phases involved in the healing process of a full-thickness wound are hemostasis, inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling.

Hemostasis: A series of events designed to control blood loss, establish bacterial control, and seal the defect occurs when there is an injury. During hemostasis injured blood vessels constrict, and platelets gather to stop bleeding. Clots form a fibrin matrix that later provides a framework for cellular repair.

Inflammatory Phase: In the inflammatory stage damaged tissue and mast cells secrete histamine, resulting in vasodilation of surrounding capillaries and exudation of serum and white blood cells into damaged tissues. This results in localized redness, edema, warmth, and throbbing. The inflammatory response is beneficial, and there is no value in attempting to cool the area or reduce the swelling unless the swelling occurs within a closed compartment (e.g., ankle or neck).

Leukocytes (white blood cells) reach the wound within a few hours. The primary-acting white blood cell is the neutrophil, which begins to ingest bacteria and small debris. The second important leukocyte is the monocyte, which transforms into macrophages. The macrophages are the “garbage cells” that clean a wound of bacteria, dead cells, and debris by phagocytosis. Macrophages continue the process of clearing the wound of debris and release growth factors that attract fibroblasts, the cells that synthesize collagen (connective tissue). Collagen appears as early as the second day and is the main component of scar tissue.

In a clean wound the inflammatory phase establishes a clean wound bed. The inflammatory phase is prolonged if too little inflammation occurs, as in a debilitating disease such as cancer or after administration of steroids. Too much inflammation also prolongs healing because arriving cells compete for available nutrients. An example is a wound infection in which the increased metabolic energy requirements present in an infected wound compete for the available calorie intake.

Proliferative Phase: With the appearance of new blood vessels as reconstruction progresses, the proliferative phase begins and lasts from 3 to 24 days. The main activities during this phase are the filling of the wound with granulation tissue, contraction of the wound, and the resurfacing of the wound by epithelialization. Fibroblasts are present in this phase and are the cells that synthesize collagen, providing the matrix for granulation. Collagen mixes with the granulation tissue, and this matrix supports the reepithelialization. Collagen provides strength and structural integrity to a wound. During this period the wound contracts to reduce the area that requires healing. Finally the epithelial cells migrate from the wound edges to resurface. In a clean wound the proliferative phase accomplishes the following: the vascular bed is reestablished (granulation tissue), the area is filled with replacement tissue (collagen, contraction, and granulation tissue), and the surface is repaired (epithelialization). Impairment of healing during this stage usually results from systemic factors such as age, anemia, hypoproteinemia, and zinc deficiency.

Remodeling: Maturation, the final stage of healing, sometimes takes place for more than a year, depending on the depth and extent of the wound. The collagen scar continues to reorganize and gain strength for several months. However, a healed wound usually does not have the tensile strength of the tissue it replaces. Collagen fibers undergo remodeling or reorganization before assuming their normal appearance. Usually scar tissue contains fewer pigmented cells (melanocytes) and has a lighter color than normal skin. In dark-skinned individuals the scar tissue may be more highly pigmented than surrounding skin.

Complications of Wound Healing

Hemorrhage: Hemorrhage, or bleeding from a wound site, is normal during and immediately after initial trauma. Hemostasis occurs within several minutes unless large blood vessels are involved or the patient has poor clotting function. Hemorrhage occurring after hemostasis indicates a slipped surgical suture, a dislodged clot, infection, or erosion of a blood vessel by a foreign object (e.g., a drain). Hemorrhage occurs externally or internally. For example, if a surgical suture slips from a blood vessel, bleeding occurs internally within the tissues, and there are no visible signs of blood unless a surgical drain is present. A surgical drain may be inserted into tissues beneath a wound to remove fluid that collects in underlying tissues.

You detect internal bleeding by looking for distention or swelling of the affected body part, a change in the type and amount of drainage from a surgical drain, or signs of hypovolemic shock. A hematoma is a localized collection of blood underneath the tissues. It appears as a swelling, change in color, sensation, or warmth or mass that often takes on a bluish discoloration. A hematoma near a major artery or vein is dangerous because pressure from the expanding hematoma obstructs blood flow.

External hemorrhaging is obvious. The nurse observes dressings covering the wound for bloody drainage. If bleeding is extensive, the dressing soon becomes saturated, and frequently blood drains from under the dressing and pools beneath the patient. Observe all wounds closely, particularly surgical wounds, in which the risk of hemorrhage is great during the first 24 to 48 hours after surgery or injury.

Infection: Wound infection is the second most common health care–associated infection (nosocomial) (see Chapter 28). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2001), a wound is infected if purulent material drains from it, even if a culture is not taken or has negative results. A sample of drainage from an infected wound does not always reveal bacteria because of poor culture technique or administration of antibiotics. Positive culture findings do not always indicate an infection because many wounds contain colonies of noninfective resident bacteria. In fact, all chronic dermal wounds are considered contaminated with bacteria. What differentiates contaminated wounds from infected wounds is the amount of bacteria present. It is generally agreed that wounds with more than 100,000 (105) organisms per gram of tissue are infected (Stotts, 2012b). The chances of wound infection are greater when the wound contains dead or necrotic tissue, there are foreign bodies in or near the wound, and the blood supply and local tissue defenses are reduced. Bacterial wound infection inhibits wound healing.

Some contaminated or traumatic wounds show signs of infection early, within 2 to 3 days. A surgical wound infection usually does not develop until the fourth or fifth postoperative day. The patient has a fever, tenderness and pain at the wound site, and an elevated white blood cell count. The edges of the wound appear inflamed. If drainage is present, it is odorous and purulent, which causes a yellow, green, or brown color, depending on the causative organism (Table 48-2).

Dehiscence: When a wound fails to heal properly, the layers of skin and tissue separate. This most commonly occurs before collagen formation (3 to 11 days after injury). Dehiscence is the partial or total separation of wound layers. A patient who is at risk for poor wound healing (e.g., poor nutritional status, infection, or obesity) is at risk for dehiscence. However, obese patients have a higher risk because of the constant strain placed on their wounds and the poor healing qualities of fat tissue (Camden, 2012). Dehiscence frequently involves abdominal surgical wounds and occurs after a sudden strain such as coughing, vomiting, or sitting up in bed. Patients often report feeling as though something has given way. When there is an increase in serosanguineous drainage from a wound, be alert for the potential for dehiscence. A strategy to prevent dehiscence is to place a folded thin blanket or pillow over an abdominal wound when the patient is coughing. This provides a splint to the area, supporting the healing tissue when coughing increases the intraabdominal pressure.

Evisceration: With total separation of wound layers, evisceration (protrusion of visceral organs through a wound opening) occurs. The condition is an emergency that requires surgical repair. When evisceration occurs, the nurse places sterile towels soaked in sterile saline over the extruding tissues to reduce chances of bacterial invasion and drying of the tissues. If the organs protrude through the wound, blood supply to the tissues is compromised. The presence of an evisceration is a surgical emergency. Immediately contact the surgical team, do not allow the patient anything by mouth (NPO), observe him or her for signs and symptoms of shock, and prepare him or her for emergency surgery.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Prediction and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers

A major aspect of nursing care is the maintenance of skin integrity. Consistent, planned skin care interventions are critical to ensuring high-quality care. Nurses constantly observe their patients’ skin for breaks or impaired skin integrity. Impaired skin integrity occurs from prolonged pressure, irritation of the skin, and/or immobility, leading to the development of pressure ulcers. A pressure ulcer is a localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure or pressure in combination with shear and/or friction (EPUAP and NPUAP, 2009).

Risk Assessment

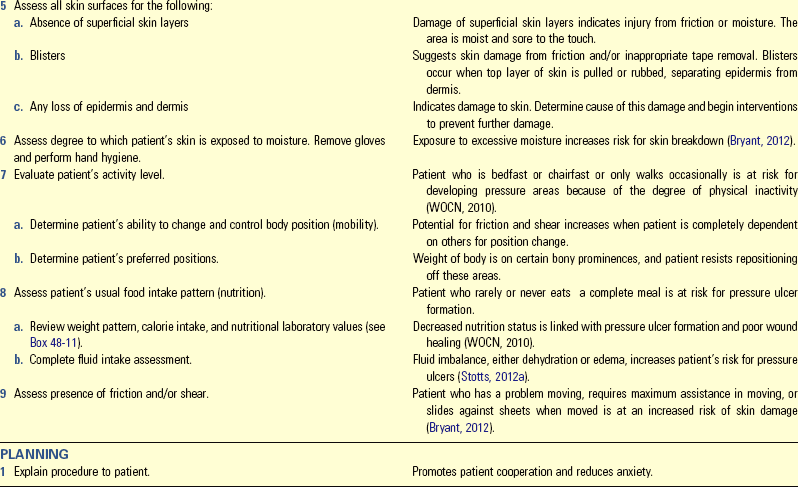

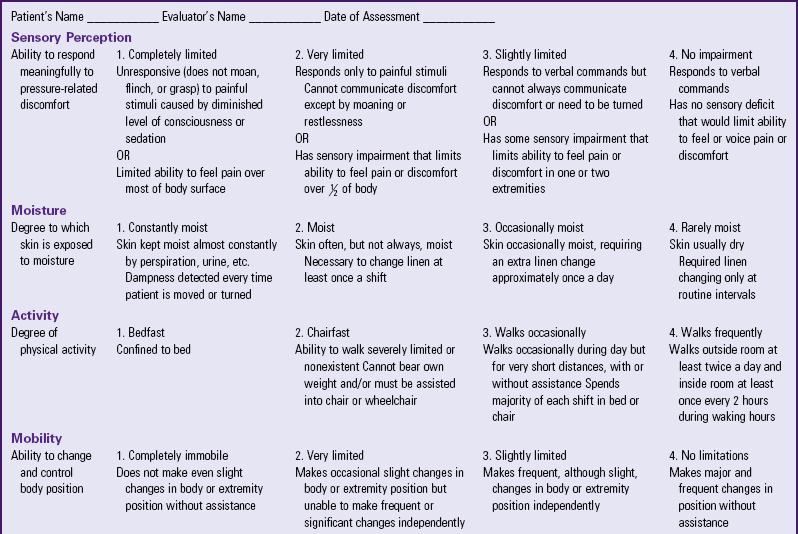

Several instruments are available for assessing patients who are at risk for developing a pressure ulcer. By identifying at-risk patients, you are able to put interventions into place for the at-risk patient and spare patients with little risk for pressure ulcer development the unnecessary and sometimes costly preventive treatment. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers are major nursing priorities. The incidence of pressure ulcers in a facility or agency is an important indicator of quality of care. Evidence exists that a program of prevention guided by risk assessment simultaneously reduces the institutional incidence of pressure ulcers by as much as 60% and brings down the costs of prevention at the same time (Braden, 2001). Several risk-assessment scales (Bergstrom et al., 1987; Norton et al., 1962) developed by nurses enable systematic risk assessment of patients. The Braden Scale, a widely used risk-assessment tool, is in the WOCN guidelines (2010) as being a valid tool to use for pressure ulcer risk assessment. The Braden Scale (Table 48-3) was developed based on risk factors in a nursing home population (Bergstrom et al., 1987) and is composed of six subscales: sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear. The total score ranges from 6 to 23; a lower total score indicates a higher risk for pressure ulcer development (Braden and Bergstrom, 1989). The cutoff score for onset of pressure ulcer risk with the Braden Scale in the general adult population is 18 (Ayello and Braden, 2002). It is highly reliable when used to identify patients at greatest risk for pressure ulcers (Bergstrom et al., 1987; Braden and Bergstrom, 1994). The Braden Scale is the most commonly used assessment scale for pressure ulcer risk.

TABLE 48-3

Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Ulcer Risk

Copyright 1988. Used with permission of Barbara Braden, PhD, RN, Professor, Creighton University School of Nursing, Omaha, Nebraska, and Nancy Bergstrom, Professor, University of Texas-Houston, School of Nursing, Houston, Texas, http://www.bradenscale.com.

Prevention

Preventing pressure ulcers is a priority in caring for patients and is not limited to patients with restrictions in mobility. Impaired skin integrity is not usually a problem in healthy, immobilized individuals but is a serious and potentially devastating problem in ill or debilitated patients (WOCN, 2010).

Economic Consequences of Pressure Ulcers: Pressure ulcers are a continual problem in acute and restorative care settings. For adult patients with pressure ulcers, 56.5% were 65 years and older (WOCN, 2010). Paralysis and spinal cord injury are common preexisting conditions among younger adults with primary diagnosis of pressure ulcers. Older adults admitted to acute and long-term facilities are a vulnerable population. Among persons admitted to long-term care, 10.3% to 18.4% had one or more pressure ulcers on admission (Baumgarten et al., 2003; Siem et al., 2003).

When a pressure ulcer occurs, the length of stay in a hospital and the overall cost of health care increase. The actual cost of treatment is difficult to estimate. About 1.6 million patients each year in acute care settings develop pressure ulcers, representing a cost of $11 to $17.2 billion to the U.S. health care system (Pieper, 2012). Adult inpatient hospital stays with a diagnosis of pressure ulcers totaled $11 billion in 2006 (WOCN, 2010). Although it is difficult to get a handle on the exact numbers of pressure ulcers, the number of patients with pressure ulcers, and the cost, the occurrence of pressure ulcers is costly to patients in terms of disability, pain, and suffering and in the costs to institutions and third-party payers. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented a policy effective October 1, 2008 whereby hospitals no longer receive additional reimbursement for care related to eight conditions, including stage III and IV pressure ulcers that occur during the hospitalization. This policy was put in place to provide additional incentives for hospitals to improve quality of care. Using guidelines such as the WOCN Guidelines (WOCN, 2010) helps reduce or eliminate the occurrence of pressure ulcers and prevent the expense that will not be reimbursed.

Factors Influencing Pressure Ulcer Formation and Wound Healing

Impaired skin integrity resulting in pressure ulcers is primarily the result of pressure. However, additional factors, including shear force, friction, moisture, nutrition, tissue perfusion, infection, and age, increase the patient’s risk for pressure ulcer development and poor wound healing.

Nutrition

For patients weakened or debilitated by illness, nutritional therapy is especially important. A patient who has undergone surgery (see Chapter 50) and is well nourished still requires at least 1500 kcal/day for nutritional maintenance. Alternatives such as enteral feedings (see Chapter 44) and parenteral nutrition (see Chapter 41) are available for patients unable to maintain normal food intake.

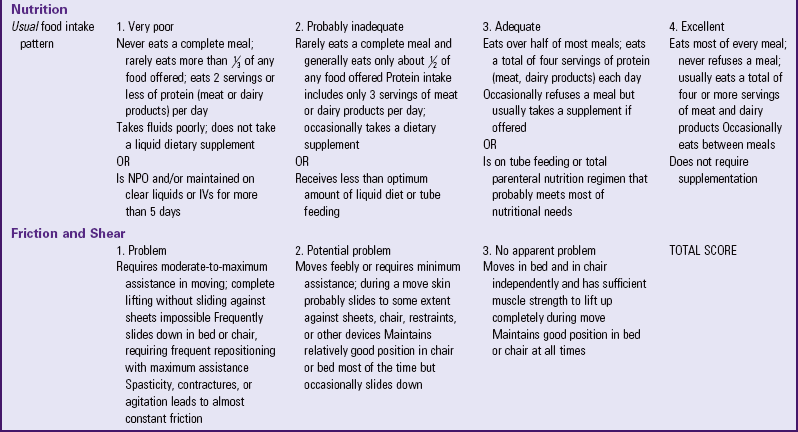

Normal wound healing requires proper nutrition (Table 48-4). Deficiencies in any of the nutrients result in impaired or delayed healing (Stotts, 2012a). Physiological processes of wound healing depend on the availability of protein, vitamins (especially A and C), and the trace minerals zinc and copper. Collagen is a protein formed from amino acids acquired by fibroblasts from protein ingested in food. Vitamin C is necessary for synthesis of collagen. Vitamin A reduces the negative effects of steroids on wound healing. Trace elements are also necessary; (i.e., zinc for epithelialization and collagen synthesis and copper for collagen fiber linking).

TABLE 48-4

Role of Selected Nutrients in Wound Healing

Modified from Ayello EA et al.: Nutritional aspects of wound healing, Home Healthc Nurse 17(11):719, 1999; and Stotts NA: Nutritional assessment and support. In Bryant RA, Nix DP, editors: Acute and chronic wounds: current management concepts, ed 4, St Louis, 2012a, Mosby.

Calories provide the energy source needed to support the cellular activity of wound healing. Protein needs especially are increased and are essential for tissue repair and growth. A balanced intake of various nutrients (i.e., protein, fat, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals) is critical to support wound healing.

Serum proteins are biochemical indicators of malnutrition (Stotts, 2012a). Serum albumin is probably the most frequently measured of these laboratory parameters. Albumin alone is not sensitive to rapid changes in nutritional status. Transferrin also evaluates protein status, but alone it does not determine malnutrition. The best measure of nutritional status is prealbumin, because it reflects not only what the patient has ingested but also what the body has absorbed, digested, and metabolized (Stotts, 2012a).

Tissue Perfusion

Oxygen fuels the cellular functions essential to the healing process; therefore the ability to perfuse the tissues with adequate amounts of oxygenated blood is critical to wound healing (Doughty and Sparks-Defriese, 2012). Patients with peripheral vascular disease are at risk for poor tissue perfusion because of poor circulation. Oxygen requirements depend on the phase of wound healing (e.g., chronic tissue hypoxia is associated with impaired collagen synthesis and reduced tissue resistance to infection).

Infection

Wound infection prolongs the inflammatory phase; delays collagen synthesis; prevents epithelialization; and increases the production of proinflammatory cytokines, which leads to additional tissue destruction (Stotts, 2012b). Indications that a wound infection is present include the presence of purulent drainage; change in odor, volume, or character of wound drainage; redness in the surrounding tissue; fever; or pain.

Age

Increased age affects all phases of wound healing. A decrease in the functioning of the macrophage leads to a delayed inflammatory response, delayed collagen synthesis, and slower epithelialization.

Psychosocial Impact of Wounds

The psychosocial impact of wounds on the physiological process of healing is unknown. The patient’s psychological response to any wound is part of the nurse’s assessment. Body image changes often impose a great stress on the patient’s adaptive mechanisms. They also influence self-concept (see Chapter 33) and sexuality (see Chapter 34). Make sure that the patient’s personal and social resources for adaptation are a part of the assessment. Factors that affect the patient’s perception of the wound include the presence of scars, drains (drains are often necessary for weeks or even months after certain procedures), odor from drainage, and temporary or permanent prosthetic devices.

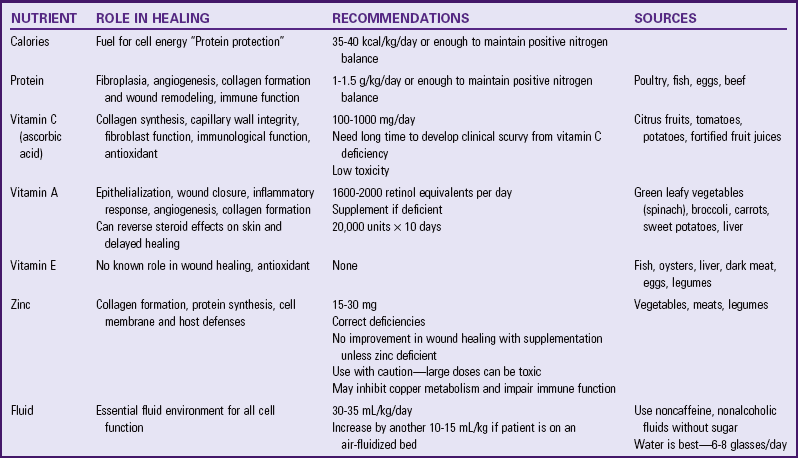

Critical Thinking

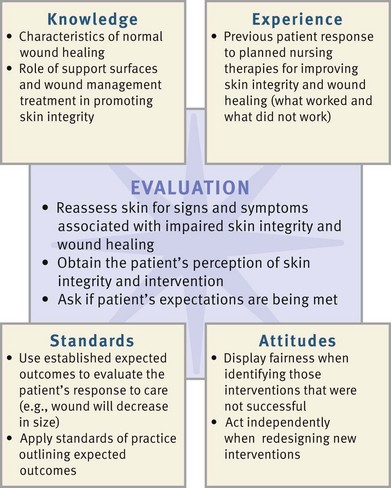

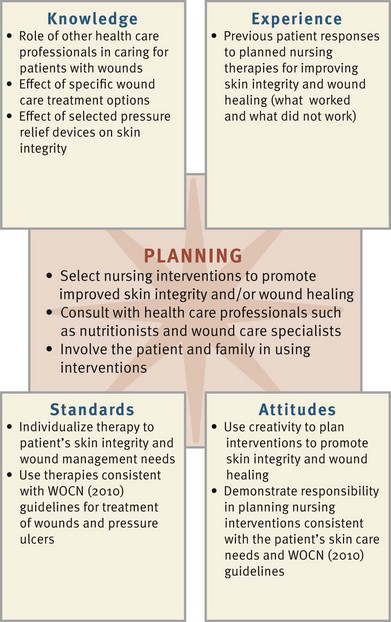

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from patients, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require the nurse to anticipate the information necessary, analyze the data, and make decisions regarding patient care. Critical thinking is always changing. During assessment (Fig. 48-7) consider all elements that build toward making appropriate nursing diagnoses.

FIG. 48-7 Critical thinking model for skin integrity and wound care assessment. WOCN, Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses Society.

When caring for patients who have impaired skin integrity and chronic wounds, integrate knowledge from nursing and other disciplines, previous experiences, and information gathered from patients to understand the risk to skin integrity and wound healing. Knowledge of normal musculoskeletal physiology, the pathogenesis of pressure ulcers, normal wound healing, and the pathophysiology of underlying diseases enables you to have a scientific basis for care. The WOCN (2010) has guidelines for assessment of risk for impaired skin integrity, prevention measures, interventions to promote wound healing, and other standards of practice, which you should use in planning care. Past experience with patients at risk for impaired skin integrity or patients with wounds increases the experiential knowledge base helping you to identify interventions. Finally you need to be disciplined during assessment to obtain comprehensive and correct assessment data. You also need to be creative. Because chronic wounds are difficult to heal, be diligent in evaluating nursing interventions and determining which interventions are effective and which need modification.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

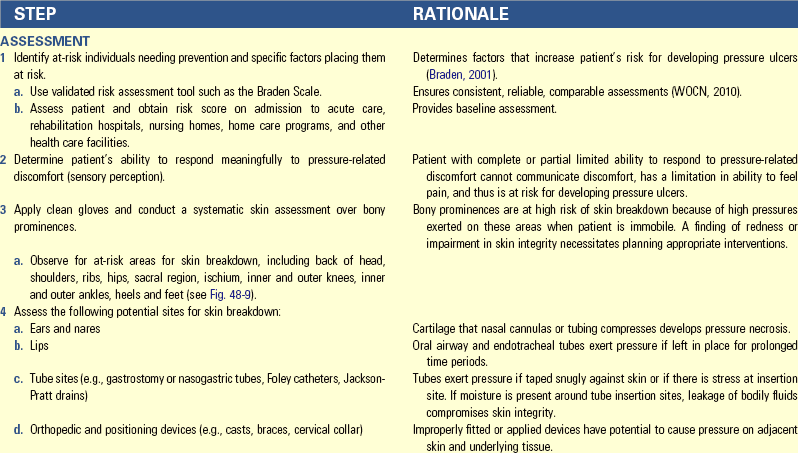

Assessment

During the assessment process thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. Baseline and continual assessment data provide critical information about a patient’s skin integrity and the increased risk for pressure ulcer development. Focusing on specific elements such as a patient’s level of sensation, movement, and continence status helps guide the skin assessment (Box 48-4).

Through the Patient’s Eyes

When patients have an acute surgical or traumatic wound, the wound sometimes heals promptly and without complications. However, when pressure ulcers or chronic wounds are present, the course of treatment is lengthy and costly. Because the patient and family need to be involved with wound care management, it is important to know the patient’s expectations. A patient who has realistic goals and is informed about the length of time for wound healing is more likely to adhere to the specific therapies designed to promote healing and prevent further skin breakdown. Therefore it is important to assess the patient’s perception of what is occurring with the wound healing interventions. The health care professional wants to determine the patient’s and family’s understanding of wound assessment; wound interventions; and supportive interventions such as positioning, nutrition, and ambulation.

Skin

A nurse continually assesses the skin for signs of ulcer development (Box 48-5). The neurologically impaired patient; the chronically ill patient in long-term care; the patient with diminished mental status; and the intensive care unit (ICU), oncology, hospice, or orthopedic patient have increased potential for developing pressure ulcers.

Assessment for tissue pressure damage includes visual and tactile inspection of the skin. Perform baseline assessment to determine a patient’s normal skin characteristics and any actual or potential areas of breakdown. You need to individualize assessment characteristics of a patient’s skin, depending on his or her skin tone (Bennett, 1995; Henderson et al., 1997). Accurate assessment of patients with darker skin pigmentation is an essential skill for all health care providers (Nix, 2012). Assessment characteristics of darkly pigmented skin are in Boxes 48-2 and 48-3.

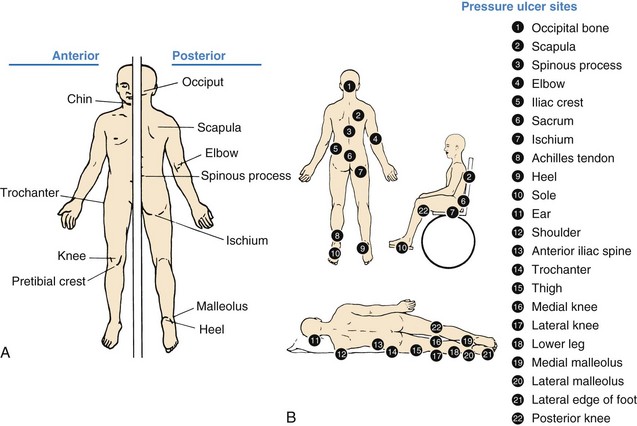

Pay particular attention to areas located over bony prominences or under casts, traction, splints, braces, collars, or other orthopedic devices. The frequency of pressure checks depends on the schedule of appliance application and the response of the skin to the external pressure (Fig. 48-8).

FIG. 48-8 Formation of pressure ulcer on heel resulting from external pressure from mattress of bed. (Courtesy Janice Colwell, RN, MS, CWOCN, FAAN, Clinical Nurse Specialist, University of Chicago Medical Center.)

When you note hyperemia, document the location, size, and color and reassess the area after 1 hour. When you suspect abnormal reactive hyperemia, outline the affected area with a marker to make reassessment easier. These signs are early indicators of impaired skin integrity, but damage to the underlying tissue is sometimes more progressive. Tactile assessment enables you to use palpation to acquire further data about induration and the damage to the skin and underlying tissues.

Gently palpate the reddened tissue, observing for blanching with return to normal skin tones in patients with light-toned skin. In addition, palpate for induration, noting the size in millimeters or centimeters of the induration around the injured area and changes in temperature of the surrounding skin and tissues.

Use visual and tactile inspection over the body areas most frequently at risk for pressure ulcer development (Fig. 48-9). For example, when a patient lies in bed or sits in a chair, he or she places body weight heavily on certain bony prominences. Body surfaces subjected to the greatest weight or pressure are at greatest risk for pressure ulcer formation.

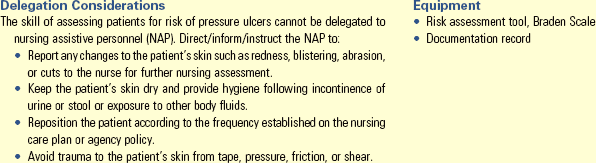

Pressure Ulcers

Pressure ulcers have multiple etiological factors. Assessment for pressure ulcer risk includes using an appropriate predictive measure and assessing a patient’s mobility, nutrition, presence of body fluids, and comfort level (Skill 48-1 on pp. 1213-1215).

Predictive Measures: On admission to acute care and rehabilitation hospitals, nursing homes, home care programs, and other health care facilities, assess individuals for risk of pressure ulcer development (WOCN, 2010). Perform pressure ulcer risk assessment systematically (WOCN, 2010). Use an assessment tool such as the Braden scale (see Table 48-3). The interpretation of the meaning of the total numerical scores differs with each risk-assessment scale. Lower numerical scores on the Braden scale indicate that a patient is at high risk for skin breakdown. A benefit of the predictive instruments is to increase a nurse’s early detection of patients at greatest risk for ulcer development. Once you identify these patients, institute the appropriate interventions to maintain skin integrity and implement prevention strategies (WOCN, 2010). Perform reassessment for pressure ulcer risk on a scheduled basis.

Mobility: Assessment includes documenting the level of mobility and the potential effects of impaired mobility on skin integrity. Documenting assessment of mobility also includes obtaining data regarding the quality of muscle tone and strength. For example, determine whether the patient is able to lift weight off of the sacral area and roll the body to a side-lying position. Some patients have adequate range of motion to move independently into a more protective position. Finally note the patient’s activity tolerance (see Chapter 38).

You must assess mobility as part of baseline data. If a patient has some degree of mobility independence, reinforce the frequency of position changes and measures to relieve pressure. The frequency of position changes is based on ongoing skin assessment; revise it as data change. Be meticulous when assessing pressure sites.

Nutritional Status: An assessment of patients’ nutritional status is an integral part of the initial assessment data for patients at risk for impaired skin integrity and wounds (Stotts, 2012a). Malnutrition is a risk factor for pressure ulcer development (Posthauer and Thomas, 2008). A loss of 5% of usual weight, weight less than 90% of ideal body weight, and a decrease of 10 pounds in a brief period are all signs of actual or potential nutritional problems (Stotts, 2012a).

Body Fluids: Continual exposure of the skin to body fluids increases a patient’s risk for skin breakdown and pressure ulcer formation (Box 48-6). Some body fluids such as saliva and serosanguineous drainage are not as caustic to the skin, and the risk of skin breakdown from exposure to these fluids is low. However, exposure to urine, bile, stool, ascitic fluid, and purulent wound exudates carries a moderate risk for skin breakdown, especially in patients who have other risk factors such as chronic illness or poor nutrition. Finally exposure to gastric and pancreatic drainage has the highest risk for skin breakdown. Again, it is important to prevent and reduce the patient’s exposure to body fluids; and, when exposure occurs, you need to provide meticulous hygiene and skin care.

Pain: Until recently there has been little research about pain and pressure ulcers. The WOCN (2010) has recommended the assessment and management of pain be included in the care of patients with pressure ulcers (Dallam et al., 2008). Maintaining adequate pain control and patient comfort increases the patient’s willingness and ability to increase mobility, which in turn reduces pressure ulcer risk.

Wounds

A nurse often assesses wounds under two conditions: at the time of injury before treatment and after therapy, when the wound is relatively stable. Each condition requires him or her to make different observations and take different actions. Regardless of the setting, it is important that you initially obtain information regarding the cause and history of the wound (see Box 48-4).

Emergency Setting: You see wounds in any setting, including clinics, emergency departments, youth camps, or your own backyard. The type of wound determines the criteria for inspection. For example, you do not need to inspect for signs of internal bleeding after an abrasion, but you should inspect in the event of a puncture wound.

When you judge a patient’s condition to be stable because of the presence of spontaneous breathing, a clear airway, and a strong carotid pulse (see Chapters 30 and 40), inspect the wound for bleeding. An abrasion is superficial with little bleeding and is considered a partial-thickness wound. The wound often appears “weepy” because of plasma leakage from damaged capillaries. A laceration sometimes bleeds more profusely, depending on the depth and location of the wound. For example, minor scalp lacerations tend to bleed profusely because of the rich blood supply to the scalp. Lacerations greater than 5 cm (2 inches) long or 2.5 cm (1 inch) deep cause serious bleeding. Puncture wounds bleed in relation to the depth and size of the wound (e.g., a nail puncture does not cause as much bleeding as a knife wound). The primary dangers of puncture wounds are internal bleeding and infection.

Inspect the wound for foreign bodies or contaminant material. Most traumatic wounds are dirty. Soil, broken glass, shreds of cloth, and foreign substances clinging to penetrating objects sometimes become embedded in the wound.

The size of the wound is the next step in assessment. A deep laceration requires suturing. A large, open wound may expose bone or tissue that needs to be protected.

When the injury is a result of trauma from a dirty penetrating object, determine when the patient last received a tetanus toxoid injection. Tetanus bacteria reside in soil and in the gut of humans and animals. A tetanus antitoxin injection is necessary if the patient has not had one within 5 years.

Stable Setting: When a patient’s condition is stabilized (e.g., after surgery or treatment), assess the wound to determine progress toward healing. If the wound is covered by a dressing and the health care provider has not ordered it changed, do not directly inspect it unless you suspect serious complications. In such a situation inspect only the dressing and any external drains. If the health care provider prefers to change the dressing, he or she assesses the wound at least daily. When removing dressings, take care to avoid accidental removal or displacement of underlying drains. Because removal of dressings can be painful, consider giving an analgesic at least 30 minutes before exposing a wound.

Wound Appearance: Observe whether wound edges are closed. A surgical incision healing by primary intention should have clean, well-approximated edges. Crusts often form along the wound edges from exudate. A puncture wound is usually a small, circular wound with the edges coming together toward the center. If a wound is open, the edges are separated, and you inspect the condition of tissue at the wound base. Also look for complications such as dehiscence and evisceration. The outer edges of a wound normally appear inflamed for the first 2 to 3 days, but this slowly disappears. Within 7 to 10 days a normally healing wound resurfaces with epithelial cells, and edges close. Table 48-5 lists assessment characteristics for abnormal wound healing in primary and secondary wounds. If infection develops, the area directly surrounding the wound becomes brightly inflamed and swollen.

TABLE 48-5

Assessment of Abnormal Healing in Primary and Secondary Intention Wounds

| PRIMARY INTENTION WOUNDS | SECONDARY INTENTION WOUNDS |

| Incision line poorly approximated | Pale or fragile granulation tissue, granulation tissue bed excessively dry or moist |

| Drainage present more than 3 days after closure | Purulent exudate present |

| Inflammation increased in first 3-5 days after injury | Necrotic or slough tissue present in wound base |

| No epithelialization of wound edges by day 4 | Epithelialization not continuous |

| No healing ridge by day 9 | Fruity, earthy, or putrid odor present |

| Presence of fistula(s), tunneling, undermining |

Modified from Stotts NA, Cavanaugh CE: Assessing the patient with a wound, Home Healthc Nurse 17(1):27, 1999.

Skin discoloration usually results from bruising of interstitial tissues or hematoma formation. Blood collecting beneath the skin first takes on a bluish or purplish appearance. Gradually, as the clotted blood is broken down, shades of brown and yellow appear.

Character of Wound Drainage: Note the amount, color, odor, and consistency of drainage. The amount of drainage depends on the location and extent of the wound. For example, drainage is minimal after a simple appendectomy. In contrast, it is moderate for 1 to 2 days after drainage of a large abscess. When you need an accurate measurement of the amount of drainage within a dressing, weigh the dressing and compare it with the weight of the same dressing when clean and dry. The general rule is that 1 g of drainage equals 1 mL of volume of drainage. Another method of quantifying wound drainage is to chart the number of dressings used and the frequency of change. An increase or decrease in the number or frequency of dressings indicates a relative increase or decrease in wound drainage. The color and consistency of drainage vary, depending on the components. Types of drainage include the following: serous, sanguineous, serosanguineous, and purulent (see Table 48-2). If the drainage has a pungent or strong odor, you should suspect an infection. Describe the appearance of the wound according to characteristics observed. An example of accurate recording follows:

Abdominal incision is 5 cm in length in RLQ; edges well approximated without inflammation or exudate. 1.2-cm diameter circle of serous drainage present on one 4 × 4 gauze changed every 8 hours.

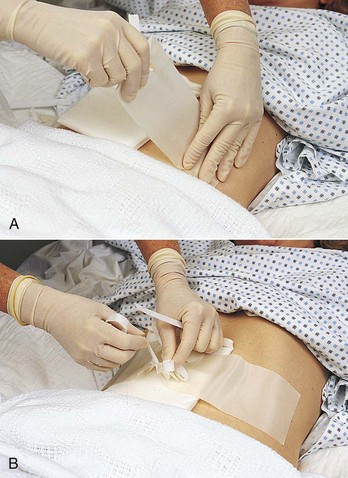

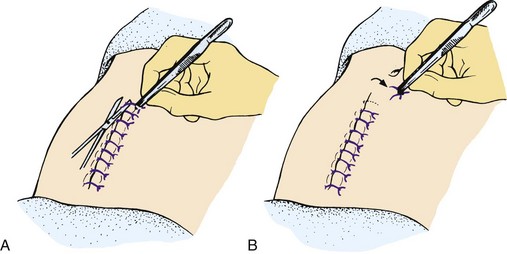

Drains: The health care provider inserts a drain into or near a surgical wound if there is a large amount of drainage. Some drains are sutured in place. Exercise caution when changing the dressing around drains that are not sutured in place to prevent accidental removal. A Penrose drain lies under a dressing; at the time of placement a pin or clip is placed through the drain to prevent it from slipping farther into a wound (Fig. 48-10). It is usually the health care provider’s responsibility to pull or advance the drain as drainage decreases to permit healing deep within the drain site.

Assess the number of drains, drain placement, character of drainage, and condition of collecting equipment. Observe the security of the drain and its location with respect to the wound. Next note the character of drainage. If there is a collecting device, measure the drainage volume. Because a drainage system needs to be patent, look for drainage flow through and around the tubing. A sudden decrease in drainage through the tubing may indicate a blocked drain, and you need to notify the health care provider. When a drain is connected to suction, assess the system to be sure that the pressure ordered is being exerted. Evacuator units such as a Hemovac or Jackson-Pratt (Fig. 48-11) exert a constant low pressure as long as the suction device (bladder or container) is fully compressed. These types of drainage devices are often referred to as self-suction. When the evacuator device is unable to maintain a vacuum on its own, notify the surgeon, who then orders a secondary vacuum system (such as wall suction). If fluid accumulates within the tissues, wound healing does not progress at an optimal rate, and this increases the risk of infection.

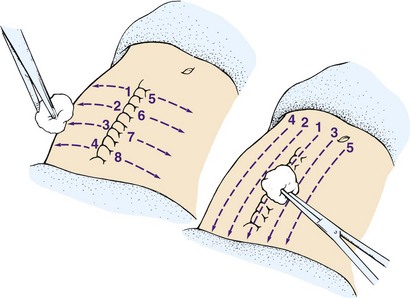

Wound Closures: Surgical wounds are closed with staples, sutures, or wound closures. A frequent skin closure is the stainless-steel staple. The staple provides more strength than nylon or silk sutures and tends to cause less irritation to tissue. Look for irritation around staple or suture sites and note whether closures are intact. Normally for the first 2 to 3 days after surgery the skin around sutures or staples is edematous. Continued swelling may indicate that the closures are too tight. The skin can be cut by overly tight suture material, leading to wound separation. Early suture removal reduces formation of defects along the suture line and minimizes chances of unattractive scar formation.

Dermabond is a tissue adhesive that forms a strong bond across apposed wound edges, allowing normal healing to occur below. It can be used to replace small sutures for incisional repair. A vial containing the Dermabond solution is used to apply the product to approximated tissue. The wound edges are held together until the solution dries, providing an adhesive closure. Although generally used for small superficial lacerations, some surgeons use it on larger wounds where subcutaneous sutures are needed (Bruns and Worthington, 2000).

Palpation of Wound: When inspecting a wound, observe swelling or separation of wound edges. While wearing gloves, lightly press the wound edges, detecting localized areas of tenderness or drainage collection. If pressure causes fluid to be expressed, note the character of the drainage. The patient is normally sensitive to palpation of wound edges. Extreme tenderness indicates infection.

Wound Cultures: If you detect purulent or suspicious-looking drainage, obtaining a specimen of the drainage for culture may be necessary (see Chapter 28). Never collect a wound culture sample from old drainage. Resident colonies of bacteria from the skin grow within exudate and are not always the true causative organisms of a wound infection. Clean a wound first with normal saline to remove skin flora. Aerobic organisms grow in superficial wounds exposed to the air, and anaerobic organisms tend to grow within body cavities. Use a different method of specimen collection for each type of organism per agency policy (Box 48-7).

Gram stains of drainage are often performed as well. This test allows the health care provider to order appropriate treatment earlier than when only cultures are done. No additional specimens are usually required. The microbiology laboratory needs only to be notified to perform the additional test.

The gold standard of wound culture is tissue biopsy. A health care provider or wound care specialist with special training obtains the biopsy (Stotts, 2012b).

Nursing Diagnosis

Assessment reveals clusters of data to indicate whether an actual or a risk for impaired skin integrity exists. In addition, the assessment data will provide information on the related factor. For example, a postoperative patient has purulent drainage from a surgical wound and reports tenderness around the area of the wound. These data support a nursing diagnosis of impaired skin integrity related to infection (Box 48-8). After completing an assessment of a patient’s wound, the nurse identifies nursing diagnoses that direct supportive and preventive care. Multiple nursing diagnoses are associated with impaired skin integrity and wounds:

• Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements

• Risk for impaired skin integrity

Some patients are at risk for poor wound healing because of previously defined factors that impair healing. Thus, even though the patient’s wound appears normal, the nurse identifies nursing diagnoses such as impaired nutrition or ineffective peripheral tissue perfusion that direct nursing care toward support of wound repair.

The nature of a wound can cause problems unrelated to wound healing. Alteration in comfort and impaired mobility are problems that have implications for the patient’s eventual recovery. For example, a large abdominal incision causes enough pain to interfere with the patient’s ability to turn in bed effectively.

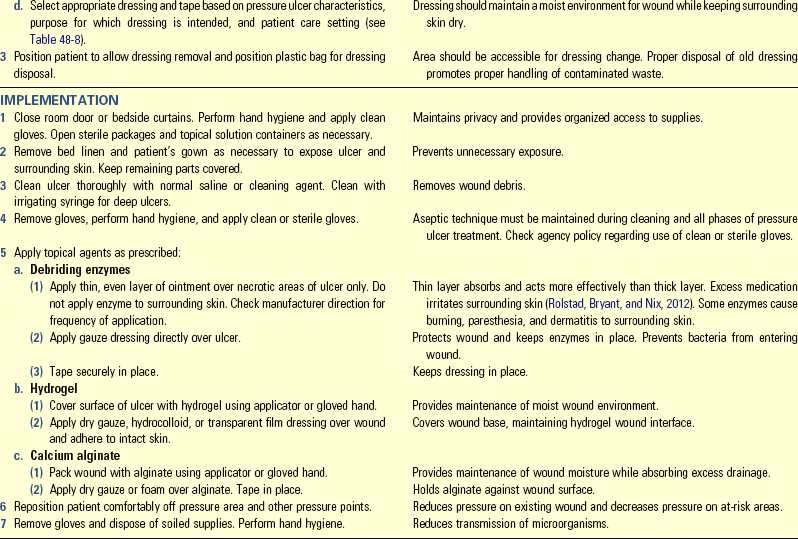

Planning

After identifying nursing diagnoses, develop a plan of care for a patient who has actual or is at risk for impaired skin integrity. During planning synthesize information from multiple resources (Fig. 48-13). Critical thinking ensures that a patient’s plan of care integrates all that you know about the individual and key critical thinking elements. Professional standards are especially important to consider when you develop a plan of care.

FIG. 48-13 Critical thinking model for skin integrity and wound care planning. WOCN, Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses Society.

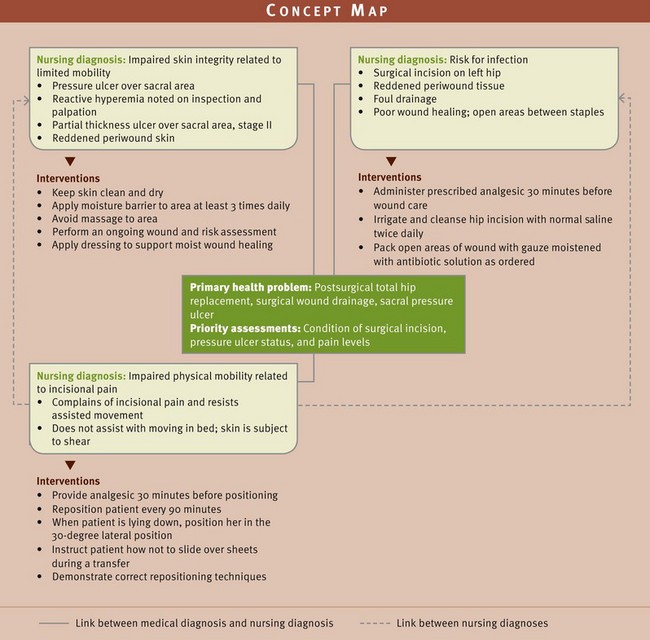

Patients who have large, chronic wounds or infected wounds have multiple nursing care needs. A concept map helps to individualize care for a patient who has multiple health problems and related nursing diagnoses (Fig. 48-14). This map helps you use critical thinking skills to organize complex patient assessment data into related nursing diagnoses with the patient’s chief medical diagnosis. As you identify linkages between the nursing diagnoses and the chief medical diagnosis, the concept map also links potential interventions that apply to the patient’s health care needs.

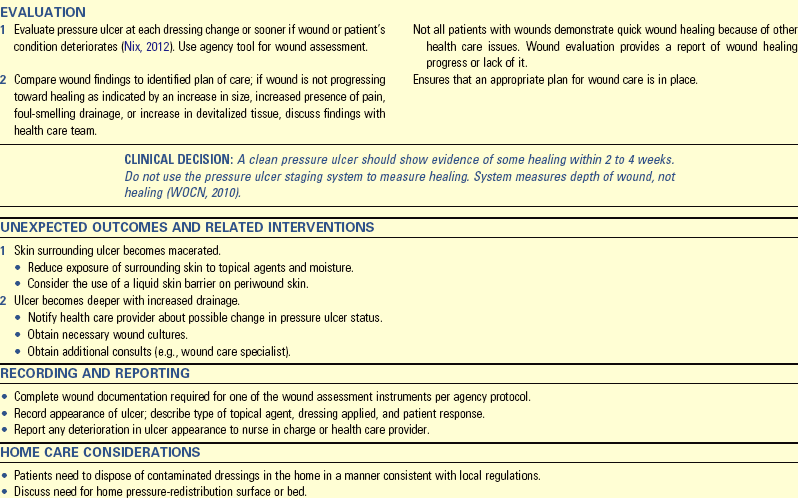

Goals and Outcomes

Nursing care is based on a patient’s identified needs and priorities. You establish goals and expected outcomes, and from the goals you plan interventions according to the risk for pressure ulcers or the type and severity of the wound and the presence of any complications such as infection, poor nutrition, peripheral vascular diseases, or immunosuppression that can affect wound healing (see the Nursing Care Plan). A goal frequently identified when working with a patient with a wound is to see wound improvement within a 2-week period. The outcomes of this goal can include the following:

• Higher percentage of granulation tissue in the wound base

These outcomes are reasonable if the overall goal for the patient is to heal the wound. Plan therapies according to the severity and type of wound and the presence of any complicating conditions (e.g., infection, poor nutrition, immunosuppression, and diabetes) that affect wound healing. Other goals of care for patients with wounds include the following: promoting wound hemostasis, preventing infection, promoting wound healing, maintaining skin integrity, gaining comfort, and promoting health.

Setting Priorities

You establish nursing care priorities in wound care based on the comprehensive patient assessment and goals and established outcomes. These priorities also depend on whether the patient’s condition is stable or emergent. An acute wound needs immediate intervention; whereas in the presence of a chronic, stable wound the patient’s hygiene is more important. When there is a risk for pressure ulcer development, preventive interventions such as skin care practices, elimination of shear, and positioning are high priorities. Promotion of wound healing is a major nursing priority; and the type of wound care administered depends on the type, size, and location of the wound and overall treatment goals.

Other patient factors to consider when establishing priorities include patient preferences, daily activities, and family factors. These factors are important regardless of the setting for health care. The priorities of care may not vary from outpatient, home, acute care, or restorative care settings.

Teamwork and Collaboration

With early discharge from health care settings, it is important to consider a patient’s plan for discharge. Anticipating the patient’s discharge wound care needs and related equipment and resources such as referral to a home care agency or outpatient wound care clinic helps to improve not only wound healing but also the patient’s level of independence. Patients and their families often need to continue the objectives of wound management after discharge (Box 48-9). You need to consider the ability of the caregiver and the amount of time needed to change a particular dressing when selecting a dressing for the patient to use after discharge. For example, in the home setting some caregivers choose more expensive dressing materials to reduce the frequency of dressing changes. The nurse and patient work together to establish ways of maintaining patient involvement in nursing care and promoting wound healing, whether the patient is in the hospital or home.

Implementation

Perhaps the most effective intervention for problems with skin integrity and wound care is prevention. Prompt identification of high-risk patients and their risk factors helps to prevent pressure ulcers.

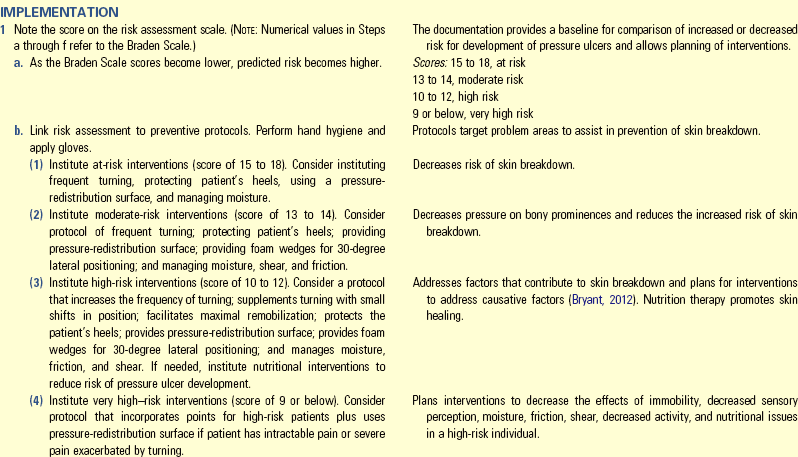

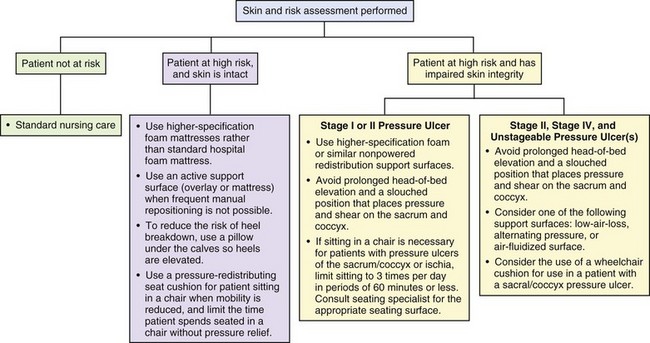

Prevention of Pressure Ulcers: When a patient is immobile, the major risk to the skin is the formation of pressure ulcers. Nursing interventions focus on prevention. The first step in prevention is to assess the patient’s risk factors for pressure ulcer development (Table 48-6). Plan on reducing or eliminating the identified risk factors.

TABLE 48-6

A Quick Guide to Pressure Ulcer Prevention

| RISK FACTOR | NURSING INTERVENTIONS |

| Decreased sensory perception | Assess pressure points for signs of nonblanching reactive hyperemia. Provide pressure-redistribution surface. |

| Moisture | Assess need for incontinence management. Following each incontinent episode, clean area with no-rinse perineal cleaner and protect skin with moisture-barrier ointment. |

| Friction and shear | Reposition patient using drawsheet and lifting off surface. Provide trapeze to facilitate movement. Position patient at a 30-degree lateral turn and limit head elevation to 30 degrees. |

| Decreased activity/mobility | Establish and post individualized turning schedule. |

| Poor nutrition | Provide adequate nutritional and fluid intake; assist with intake as necessary. Consult dietitian for nutritional evaluation. |

Early identification of patients at risk and their risk factors helps you prevent pressure ulcers. Prevention minimizes the impact that risk factors or contributing factors have on pressure ulcer development. Three major areas of nursing interventions for prevention of pressure ulcers are: (1) skin care and management of incontinence; (2) mechanical loading and support devices, which include proper positioning and the use of therapeutic surfaces; and (3) education (WOCN, 2010).

Topical Skin Care and Incontinence Management: You need to perform frequent skin assessment (see Box 48-5) at a minimum on a once-a-day basis. However, high-risk patients have more frequent skin assessments such as every shift. In addition, ensure that the patient’s skin is clean and dry.

When you clean the skin, avoid soap and hot water. Use cleaners with nonionic surfactants that are gentle to the skin (WOCN, 2010). Many types of products are available for skin care, and you need to match their use to the specific needs of the patient. After you clean the skin and make sure that it is completely dry, apply moisturizer to keep the epidermis well lubricated but not oversaturated.

Make an effort to control, contain, or correct incontinence, perspiration, or wound drainage. Patients who have fecal incontinence and who are also receiving enteral tube feeding provide a management challenge. When patients have an incontinent episode, gently clean the area, dry, and apply a thick layer of moisture barrier to the exposed areas. A moisture barrier protects the skin from excessive moisture and bacteria found in the urine or stool.

It is helpful to use the expertise of an advanced practice nurse with a focus on wound care or management of incontinence while caring for at-risk patients. Methods for controlling or containing incontinence vary. You can treat urinary incontinence with behavioral techniques, medication, and surgery. Behavioral techniques help patients learn ways to control their bladder and sphincter muscles. Two examples are bladder and habit training, which is also called timed voiding.

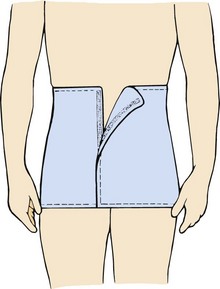

Consider using absorbent pads and garments only after trying these measures. Although controversial, absorbent products such as absorptive underpads and garments are sometimes part of the treatment plan for an incontinent patient. Use only products that wick moisture away from the patient’s skin (WOCN, 2010).

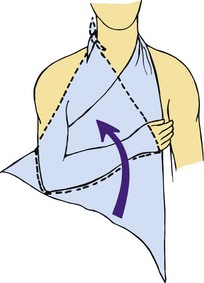

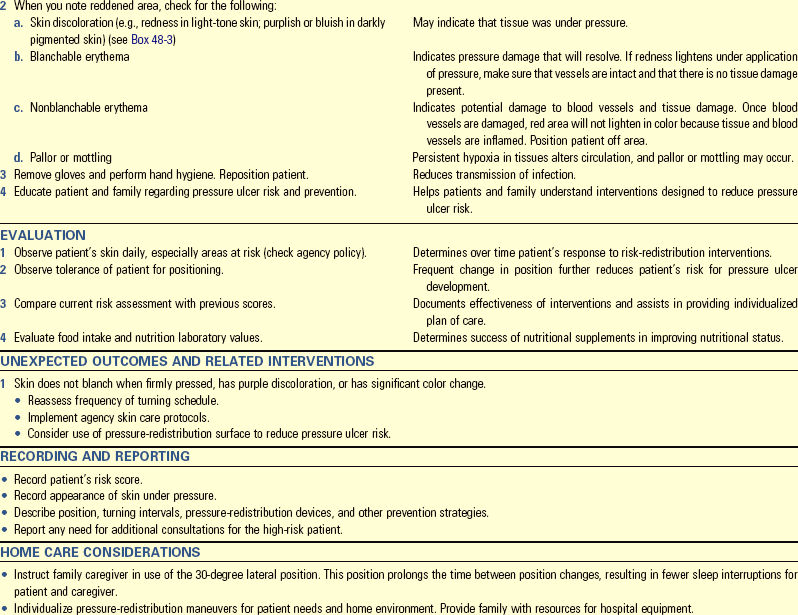

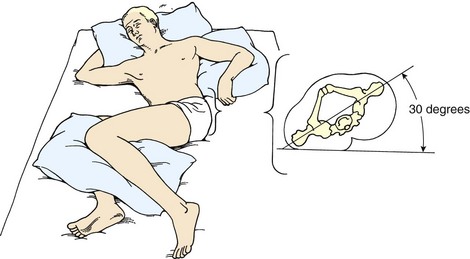

Positioning: Positioning interventions reduce pressure and shearing force to the skin. Elevating the head of the bed to 30 degrees or less decreases the chance of pressure ulcer development from shearing forces (WOCN, 2010). Change the immobilized patient’s position according to activity level, perceptual ability, and daily routines (Brienza et al., 2008). A standard turning interval of  to 2 hours does not always prevent pressure ulcer development. Patients need repositioning on a schedule of at least every 2 hours if allowed by their overall condition. When repositioning, use positioning devices to protect bony prominences (WOCN, 2010). The WOCN guidelines (2010) recommend a 30-degree lateral position (Fig. 48-15), which should prevent positioning directly over the bony prominence. To prevent shear and friction injuries, use a transfer device to lift rather than drag the patient when changing positions (see Chapter 47).

to 2 hours does not always prevent pressure ulcer development. Patients need repositioning on a schedule of at least every 2 hours if allowed by their overall condition. When repositioning, use positioning devices to protect bony prominences (WOCN, 2010). The WOCN guidelines (2010) recommend a 30-degree lateral position (Fig. 48-15), which should prevent positioning directly over the bony prominence. To prevent shear and friction injuries, use a transfer device to lift rather than drag the patient when changing positions (see Chapter 47).

FIG. 48-15 Thirty-degree lateral position at which pressure points are avoided. (Adapted from Bryant RA, Nix DP, editors: Acute and chronic wounds: current management concepts, ed 4, St Louis, 2012, Mosby.)

Some patients are able to sit in a chair. Make sure to limit the total amount of time they sit to 2 hours or less. In the sitting position the pressure on the ischial tuberosities is greater than in the supine position. In addition, teach a mobile patient at risk for skin breakdown in a sitting position to shift weight every 15 minutes (WOCN, 2010). Shifting weight provides short-term relief on the ischial tuberosities. Also have him or her sit on foam, gel, or an air cushion to redistribute weight away from the ischial areas. Rigid and donut-shaped cushions are contraindicated because they reduce blood supply to the area, resulting in wider areas of ischemia (WOCN, 2010).

After repositioning the patient, reassess the skin. Identifying characteristics that indicate early signs of tissue ischemia in darkly pigmented skin are in Boxes 48-2 and 48-3. For patients with light-toned skin, observe for normal reactive hyperemia and blanching. Never massage the reddened areas. Massaging reddened areas increases breaks in the capillaries in the underlying tissues and the risk of injury to underlying tissue and pressure ulcer formation (WOCN, 2010).

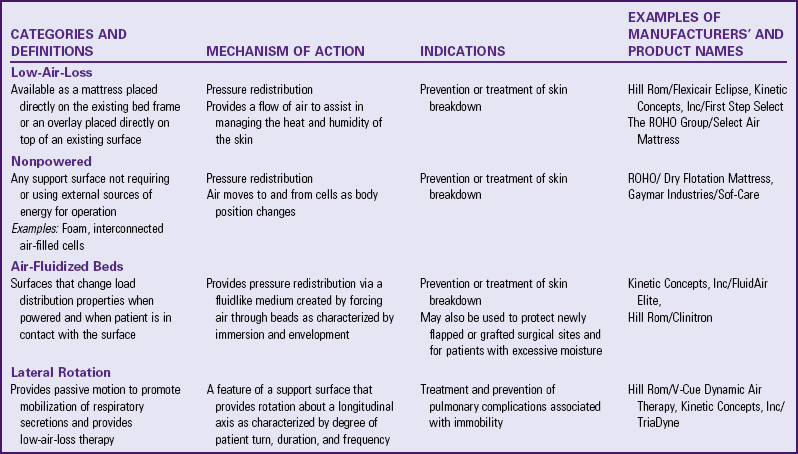

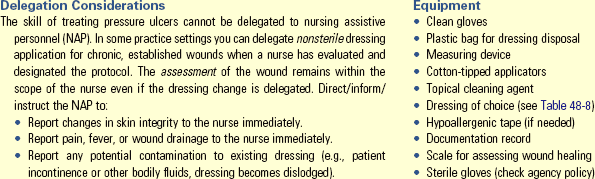

Support Surfaces (Therapeutic Beds and Mattresses): A support surface is a specialized device for pressure redistribution designed for management of tissue loads, microclimate, and/or other therapeutic functions (i.e., mattresses, integrated bed system, mattress replacement, overlay or seat cushion, or seat cushion overlay) (EPUAP and NPUAP, 2009). A variety of support surfaces, including specialty v and mattresses, reduce the hazards of immobility to the skin and musculoskeletal system. However, none eliminates the need for meticulous nursing care. No single device eliminates the effects of pressure on the skin.

When selecting support surfaces, incorporate the patient’s needs. Knowledge about support surface characteristics (Table 48-7) assists you in clinical decision making. In selecting a support surface, know the patient’s risks and the purpose for the support surface; a flow chart is often helpful (Fig. 48-16). Teach patients and families the reason for and proper use of the beds or mattresses (Box 48-10). Some common errors with support surfaces are placing the wrong side of the support surface toward the patient, not plugging powered support surfaces into the electrical source, not turning on the power source for powered support surfaces, failing to place hand between the metal bed frame and the mattress to determine if patient sinks to the point of touching the bed frame for some support surfaces, and improperly inflating some support surfaces. When used correctly, these support services help reduce pressure ulcers in patients at risk.

FIG. 48-16 Considerations for choosing the appropriate support surface. (Modified from WOCN: Guideline for prevention and management of pressure ulcers, 2010, Mt Laurel, NJ; and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) and European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP): International guideline for prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers, Washington DC, 2009, National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel.)

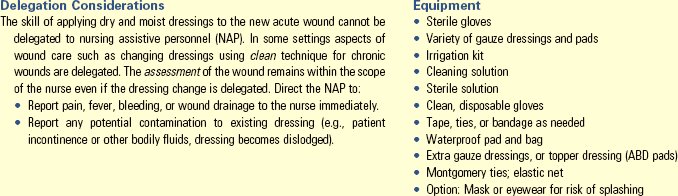

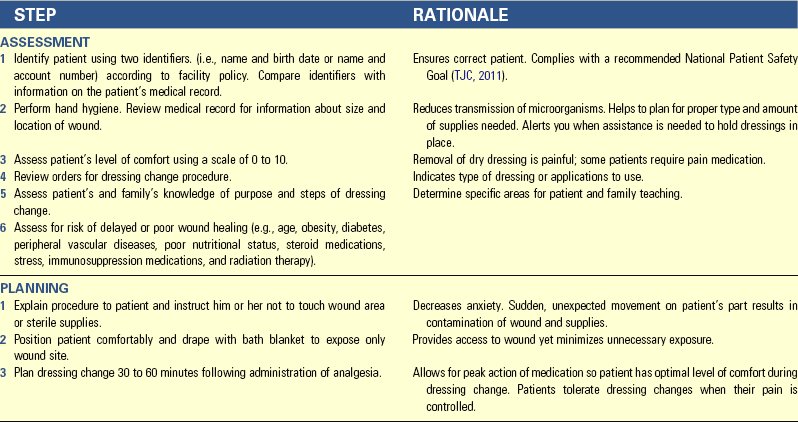

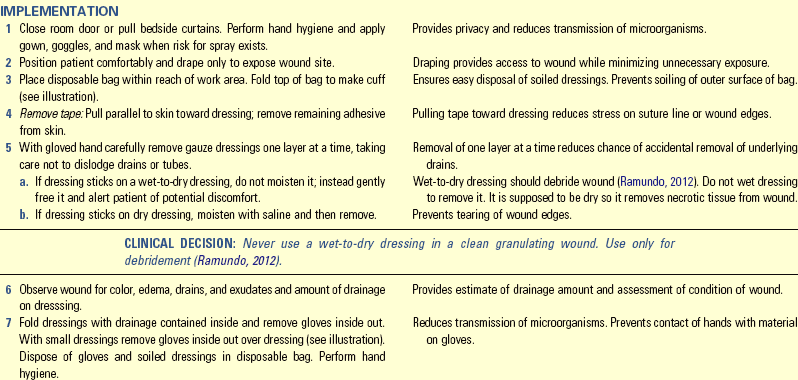

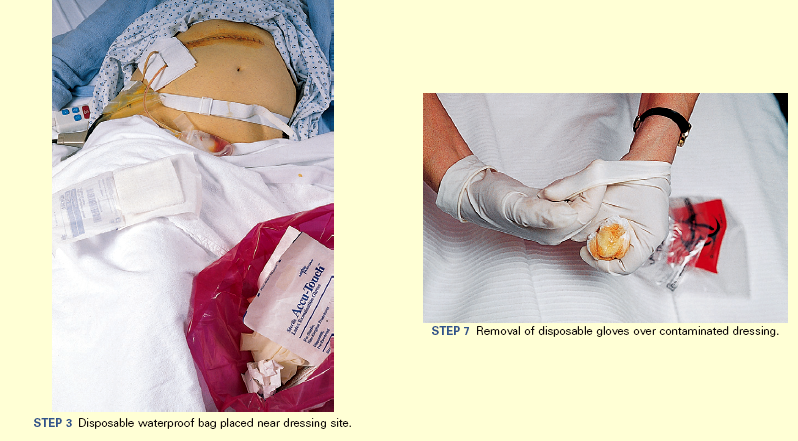

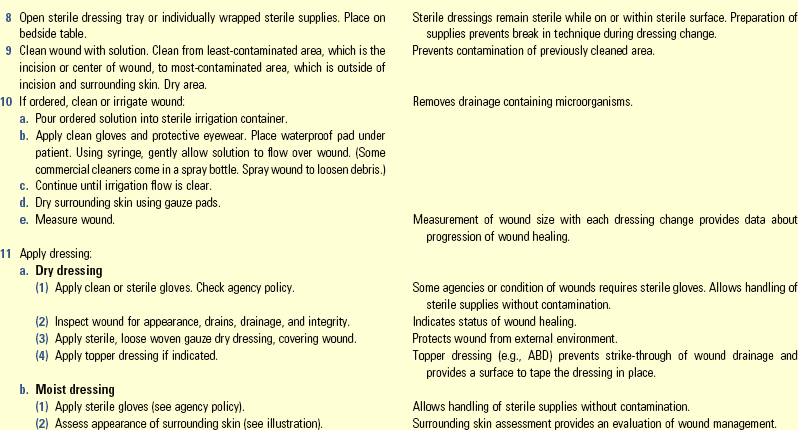

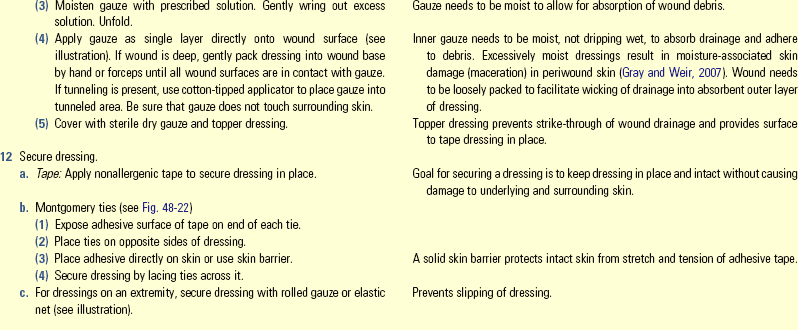

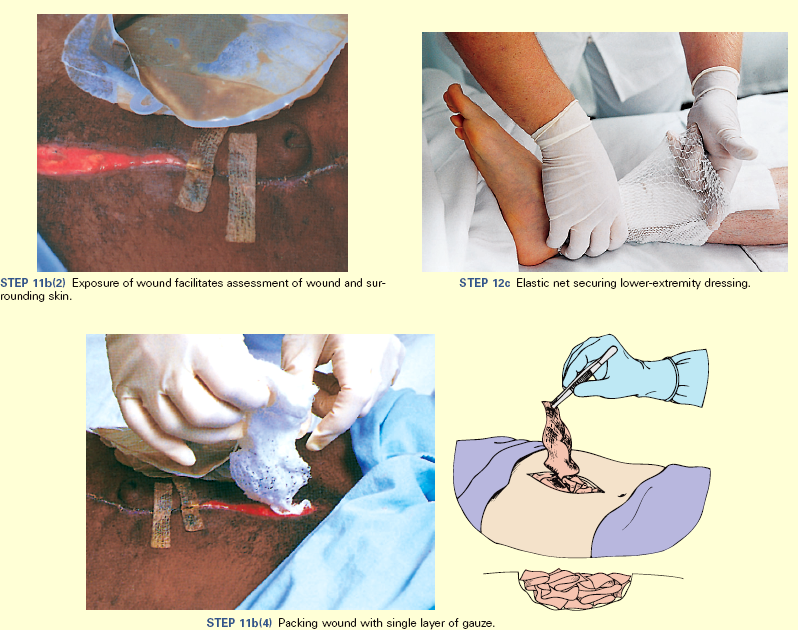

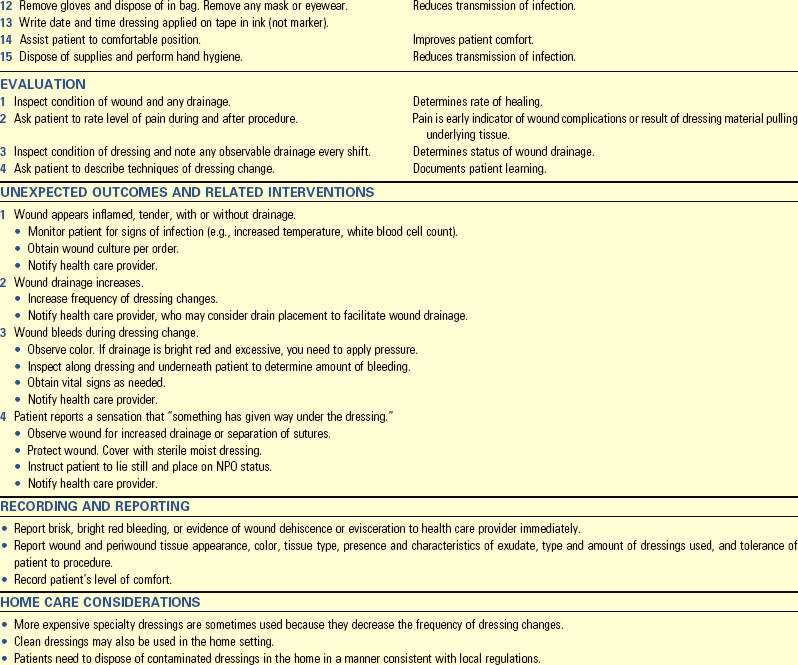

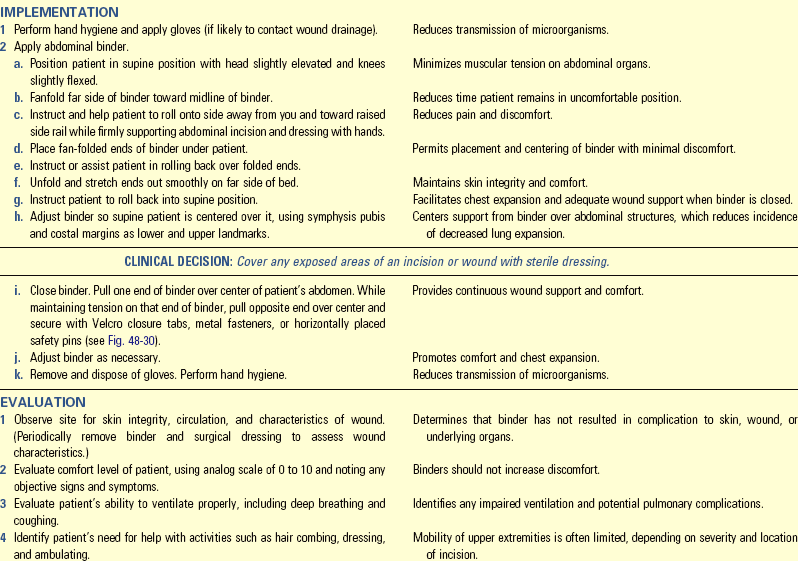

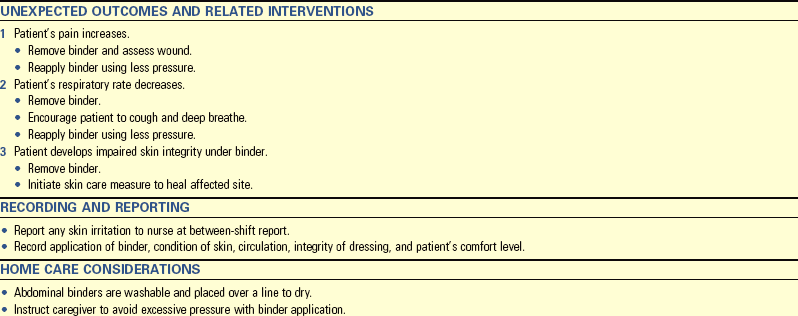

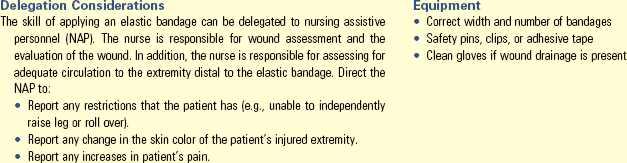

Acute Care