Urinary Elimination

• Describe the process of urination.

• Identify factors that commonly influence urinary elimination.

• Compare and contrast common alterations in urinary elimination.

• Obtain a nursing history for a patient with urinary elimination problems.

• Identify nursing diagnoses appropriate for patients with alterations in urinary elimination.

• Obtain urine specimens correctly.

• Describe characteristics of normal and abnormal urine.

• Describe the nursing implications of common diagnostic tests of the urinary system.

• Discuss nursing measures to promote normal micturition and reduce episodes of incontinence.

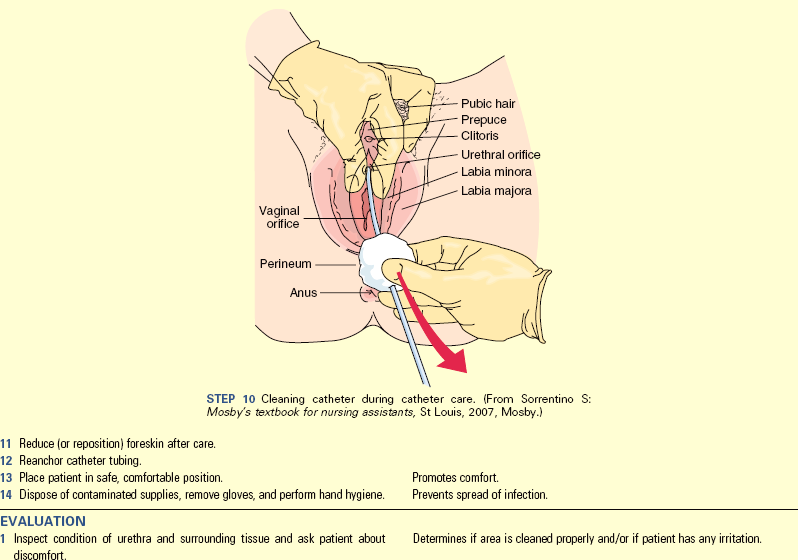

• Insert a urinary catheter correctly.

• Discuss nursing measures to reduce urinary tract infection.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Normal elimination of urinary wastes is a basic function that most people take for granted. When the urinary system fails to function properly, eventually all organ systems are affected. Patients with alterations in urinary elimination often suffer emotionally from body image changes. It is important to know the reasons for urinary elimination problems, find acceptable solutions, and provide understanding and sensitivity to all patients’ needs.

Scientific Knowledge Base

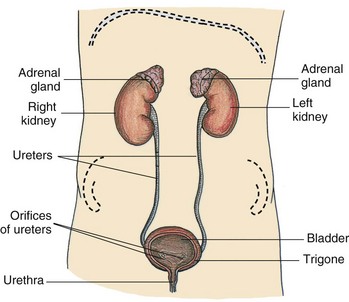

Urinary elimination depends on the function of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. Kidneys remove wastes from the blood to form urine. Ureters transport urine from the kidneys to the bladder. The bladder holds urine until the urge to urinate develops. Urine leaves the body through the urethra. All organs of the urinary system must be intact and functional for successful removal of urinary wastes. Intact efferent and afferent nerves from the bladder to the spinal cord and brain must be present (Fig. 45-1).

Kidneys

The kidneys lie on either side of the vertebral column behind the peritoneum and against the deep muscles of the back. Normally the left kidney is higher than the right because of the anatomical position of the liver.

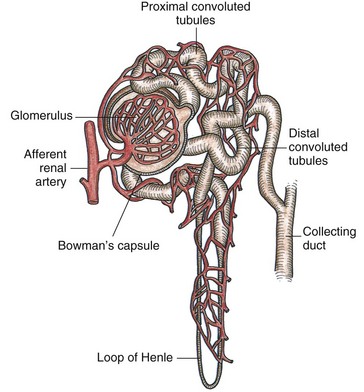

Kidneys filter waste products of metabolism that collect in the blood. The blood reaches each kidney by a renal (kidney) artery that branches from the abdominal aorta. Approximately 20% to 25% of the cardiac output circulates each minute through the kidneys. The nephron, the functional unit of the kidney, forms the urine. It is composed of the glomerulus, Bowman’s capsule, proximal convoluted tubule, loop of Henle, distal tubule, and collecting duct (Fig. 45-2).

A cluster of blood vessels forms the capillary network of the glomerulus, which is the initial site of filtration of the blood and the beginning of urine formation. The glomerular capillaries permit filtration of water, glucose, amino acids, urea, creatinine, and major electrolytes into Bowman’s capsule. Large proteins and blood cells do not normally filter through the glomerulus. The presence of large proteins in the urine (proteinuria) is a sign of glomerular injury. The glomerulus filters approximately 125 mL of filtrate per minute.

Not all of the glomerular filtrate is excreted as urine. Approximately 99% is resorbed into the plasma, with the remaining 1% excreted as urine (Huether et al., 2008). The kidneys play a key role in fluid and electrolyte balance (see Chapter 41). Although output does depend on intake, the normal adult urine output averages 1200 to 1500 mL/day. An output of less than 30 mL/hr indicates possible circulatory, blood volume, or renal alterations.

The kidneys produce several substances vital to red blood cell (RBC) production, blood pressure, and bone mineralization. They are responsible for maintaining a normal RBC volume by producing erythropoietin. Erythropoietin functions within the bone marrow to stimulate RBC production and maturation and prolongs the life of mature RBCs (Huether et al., 2008). Patients with chronic kidney conditions cannot produce sufficient quantities of this hormone; therefore they are prone to anemia.

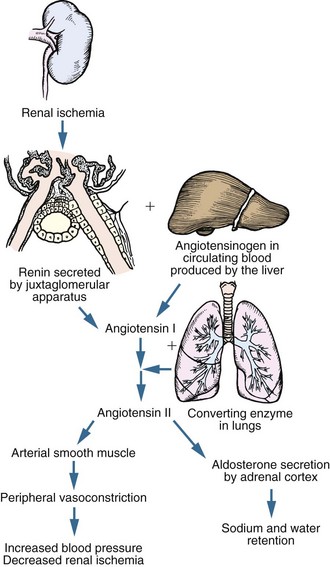

Renal hormones affect blood pressure regulation in several ways. In times of renal ischemia (decreased blood supply), renin is released from juxtaglomerular cells (Fig. 45-3). Renin functions as an enzyme to convert angiotensinogen (a substance synthesized by the liver) into angiotensin I. Angiotensin I is converted to angiotensin II in the lungs. Angiotensin II causes vasoconstriction and stimulates aldosterone release from the adrenal cortex. Aldosterone causes retention of water, which increases blood volume. The kidneys also produce prostaglandin E2 and prostacyclin, which help maintain renal blood flow through vasodilation. These mechanisms increase arterial blood pressure and renal blood flow (Huether et al., 2008).

The kidneys affect calcium and phosphate regulation by producing a substance that converts vitamin D into its active form. Patients with chronic alterations in kidney function do not make sufficient amounts of the active vitamin D. They are prone to develop renal bone disease resulting from the demineralization of bone caused by impaired calcium absorption.

Ureters

The ureters are tubular structures that enter the urinary bladder. Urine draining from the ureters to the bladder is usually sterile.

Peristaltic waves cause the urine to enter the bladder in spurts. The ureters enter obliquely through the posterior bladder wall. This arrangement prevents the reflux of urine from the bladder into the ureters during the act of micturition by the compression of the ureter at the ureterovesical junction (the juncture of the ureters with the bladder). An obstruction within a ureter such as a kidney stone (renal calculus) results in strong peristaltic waves that attempt to move the obstruction into the bladder. These waves result in pain often referred to as renal colic.

Bladder

The urinary bladder is a hollow, distensible, muscular organ (detrusor muscle) that stores and excretes urine. When empty, the bladder lies in the pelvic cavity behind the symphysis pubis. In men the bladder lies against the anterior wall of the rectum, and in women it rests against the anterior walls of the uterus and vagina.

The bladder expands as it becomes filled with urine. Pressure within it is usually low even when partly full, a factor that protects against infection. When the bladder is full, it expands and extends above the symphysis pubis. A greatly distended bladder may reach the level of the umbilicus. In a pregnant woman the developing fetus pushes against the bladder, reducing the capacity of the bladder and causing a feeling of fullness. This effect is more likely to occur in the first and third trimesters.

The trigone (a smooth triangular area on the inner surface of the bladder) is at the base of the bladder. An opening exists at each of the three angles of the trigone. Two are for the ureters, and one is for the urethra.

Urethra

Urine exits the bladder through the urethra and passes out of the body through the urethral meatus. Normally the turbulent flow of urine through the urethra washes it free of bacteria. Mucous membrane lines the urethra, and urethral glands secrete mucus into the urethral canal. Thick layers of smooth muscle surround the urethra. In addition, it descends through a layer of skeletal muscles called the pelvic floor muscles. When these muscles are contracted, it is possible to prevent urine flow through the urethra (Huether et al., 2008).

In women the urethra is approximately 4 to 6.5 cm ( to

to  inches) long. The external urethral sphincter, which is composed of skeletal muscle located about halfway down the urethra, permits voluntary flow of urine. However, the internal sphincter muscle is composed of smooth muscle and therefore is not under voluntary control. The short length of the urethra predisposes women and girls to infection. It is easy for bacteria to enter the urethra from the perineal area.

inches) long. The external urethral sphincter, which is composed of skeletal muscle located about halfway down the urethra, permits voluntary flow of urine. However, the internal sphincter muscle is composed of smooth muscle and therefore is not under voluntary control. The short length of the urethra predisposes women and girls to infection. It is easy for bacteria to enter the urethra from the perineal area.

In men the urethra, which is both a urinary canal and a passageway for cells and secretions from reproductive organs, is about 20 cm (8 inches) long. The male urethra has three sections: prostatic, membranous, and penile.

Act of Urination

Several brain structures influence bladder function, including the cerebral cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus, and brainstem. Together they inhibit the urge to void or allow voiding. Normal voiding involves contraction of the bladder and coordinated relaxation of the urethral sphincter and pelvic floor muscles.

Bladder capacity varies with the individual but generally ranges from 600 to 1000 mL of urine (Lewis et al., 2011), and an adult normally voids every 2 to 4 hours. However, individuals are able to sense the desire to urinate when the bladder contains a smaller amount of urine (150 to 200 mL in an adult and 50 to 100 mL in a child). It is important to teach parents that children do not have enough neurological development to be toilet trained until after 24 months and some are not developed enough until 36 months. As the volume increases, the bladder walls stretch, sending sensory impulses to the micturition center in the sacral spinal cord. Impulses from the micturition center respond to or ignore this urge, thus making urination under voluntary control. If the person chooses not to void, the external urinary sphincter remains contracted, inhibiting the micturition reflex. However, when a person is ready to void, the external sphincter relaxes, the micturition reflex stimulates the detrusor muscle to contract, and efficient emptying of the bladder occurs. It is vital that nurses understand this process to be able to assess and determine which form of incontinence or bladder problem may be occurring.

Damage to the spinal cord above the sacral region causes reflex incontinence. This condition causes loss of voluntary control of urination; but the micturition reflex pathway often remains intact, allowing urination to occur without sensation of the need to void. If a chronic obstruction caused by neurological damage such as prostate enlargement hinders bladder emptying, over time the micturition reflex changes, causing bladder overactivity and possibly causing the bladder to not empty completely. Overflow incontinence occurs when a bladder is overly full and bladder pressure exceeds sphincter pressure, resulting in involuntary leakage of urine. Causes often include head injury; spinal injury; multiple sclerosis; diabetes; trauma to the urinary system; and postanesthesia sedatives/hypnotics, tricyclics, and analgesia (Lewis et al., 2011). Hyperreflexia, a life-threatening problem affecting heart rate and blood pressure, is caused by an overly full bladder. It is usually neurogenic in nature; however, it can be caused functionally by blockage.

Factors Influencing Urination

Many factors influence the volume and quality of urine and the patient’s ability to urinate. Some pathophysiological conditions are acute and reversible (urinary tract infection [UTI]), whereas others are chronic and irreversible (slow, progressive development of renal dysfunction). Sociocultural factors, psychological factors, fluid balance, and surgical and diagnostic procedures affect urine and urination in several ways. In addition, medications, including anesthesia, interfere with both the production and characteristics of urine, affect the act of urination, and affect the ability to completely empty or control voiding.

Disease Conditions: Disease processes that affect urine elimination affect renal function (changes in urine volume or quality), the act of urine elimination, or both. Conditions that affect urine volume and quality are generally categorized as prerenal, renal, or postrenal in origin.

Decreased blood flow to and through the kidney (prerenal), disease conditions of the renal tissue (renal) and obstruction in the lower urinary tract that prevents urine flow from the kidneys (postrenal) sometimes alter renal function. Conditions of the lower urinary tract, including narrowing of the urethra, altered innervation of the bladder, or weakened pelvic and/or perineal muscles, affect urinary elimination.

Diabetes mellitus and neuromuscular diseases such as multiple sclerosis cause changes in nerve functions that can lead to possible loss of bladder tone, reduced sensation of bladder fullness, or inability to inhibit bladder contractions. Older men often suffer from benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), which makes them prone to urinary retention and incontinence. Some patients with cognitive impairments, such as Alzheimer’s disease, lose the ability to sense a full bladder or are unable to recall the procedure for voiding. Diseases that slow or hinder physical activity interfere with the ability to void. Degenerative joint disease and Parkinsonism are examples of conditions that make it difficult to reach and use toilet facilities.

Diseases that cause irreversible damage to kidney tissue result in end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Eventually the patient has symptoms resulting from uremic syndrome. An increase in nitrogenous wastes in the blood, marked fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, nausea, vomiting, headache, coma, and convulsions characterize this syndrome. As the uremic symptoms worsen, aggressive treatment is indicated for survival (Box 45-1). These treatments are renal replacement therapies.

Dialysis and organ transplantation are two methods of renal replacement. Dialysis takes one of two forms, peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis. Patients can use both dialysis modalities for a short or long term, but they require specialized equipment and nurses with specialized education.

Peritoneal dialysis is an indirect method of cleaning the blood of waste products using osmosis and diffusion, with the peritoneum functioning as a semipermeable membrane. This method removes excess fluid and waste products from the bloodstream when a sterile electrolyte solution (dialysate) is instilled into the peritoneal cavity by gravity via a surgically placed catheter. The dialysate remains in the cavity for a prescribed time interval and then is drained out by gravity, taking accumulated wastes and excess fluid and electrolytes with it.

Hemodialysis requires a machine equipped with a semipermeable filtering membrane (artificial kidney) that removes accumulated waste products and excess fluids from the blood. In the dialysis machine dialysate fluid is pumped through one side of the filter membrane (artificial kidney) while a patient’s blood passes through the other side. The processes of diffusion, osmosis, and ultrafiltration clean the patient’s blood. Then the blood returns through a specially placed vascular access device (Gore-Tex graft, arteriovenous fistula, or hemodialysis catheter).

Organ transplantation is the replacement of a patient’s diseased kidney with a healthy one from a living or cadaver donor of compatible blood and tissue type. The new organ is surgically implanted into the abdomen. Special medications (immunosuppressives) are administered, often for life, to prevent the body from rejecting the transplanted organ. Unlike the other treatments, successful organ transplantation offers patients the potential for restoration of normal kidney function.

Sociocultural Factors: The degree of privacy needed for urination varies with cultural norms. North Americans expect toilet facilities to be private, whereas some European cultures accept communal toilet facilities. Social expectations (e.g., school recesses) influence the time of urination.

Psychological Factors: Anxiety and emotional stress cause a sense of urgency and increased frequency of urination. Anxiety often prevents a person from being able to urinate completely; as a result, the urge to void returns shortly after voiding. Emotional tension makes it difficult to relax abdominal and perineal muscles. Attempting to void in a public restroom sometimes results in a temporary inability to void. Privacy and adequate time to urinate are usually important to most people.

Fluid Balance: The kidneys primarily maintain the balance between retention and excretion of fluids (see Chapter 41). If fluids and the concentration of electrolytes and solutes are in equilibrium, an increase in fluid intake causes an increase in urine production. This amount varies with food and fluid intake. The volume of urine formed at night is about half of the volume formed during the day because both intake and metabolism decline. Nocturia (awakening to void one or more times at night) is often a sign of renal alteration. In a healthy person the intake of water in food and fluids balances the output of water in urine, feces, and insensible losses in perspiration and respiration. An excessive output of urine is polyuria. A urine output that is decreased despite normal intake is called oliguria. Oliguria often occurs when fluid loss through other means (e.g., perspiration, diarrhea, or vomiting) increases. It also occurs in early kidney disease. Often in severe kidney disease no urine is produced (anuria).

Ingestion of certain fluids directly affects urine production and excretion. Coffee, tea, cocoa, and cola drinks that contain caffeine promote increased urine formation (diuresis). Alcohol inhibits the release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also resulting in increased water loss in urine.

Febrile conditions affect urine production. A patient with excessive perspiration loses a large amount of fluids through insensible water loss, which decreases urine production. Fever causes an increase in body metabolism and accumulation of body wastes. Although urine volume is reduced, it is highly concentrated.

Surgical Procedures: The stress of surgery initially triggers the general adaptation syndrome (see Chapter 37). Preoperative orders of nothing-by-mouth or an underlying disease condition affect fluid balance before surgery, which reduces urine output. In addition, the stress response releases an increased amount of ADH, which increases water resorption. Stress also elevates the level of aldosterone, causing retention of sodium and water. Both of these substances reduce urine output in an effort to maintain circulatory fluid volume.

Anesthetics and narcotic analgesics slow the glomerular filtration rate, reducing urine output. These pharmacological agents also impair sensory and motor impulses traveling among the bladder, spinal cord, and brain. Patients are often unable to sense bladder fullness and initiate or inhibit micturition. Spinal anesthetics, in particular, create the risk of urinary retention because of an inability to sense the need to void and a possible inability of the bladder muscles and urethral sphincters to respond (Lewis et al., 2011).

Surgery of lower abdominal and pelvic structures sometimes impairs urination because of local trauma to surrounding tissues. After returning from surgery involving the ureters, bladder, and urethra, patients routinely have urinary catheters.

Medications: Many medications directly or indirectly contribute to urinary dysfunction. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, alpha-adrenergic agonists, and calcium channel blockers can cause urinary retention and overflow incontinence. Alpha-antagonists, diuretics, sedative hypnotics, opioid analgesics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and antihistamines can cause urinary incontinence. Antiparkinson medications may cause urinary urgency and subsequent incontinence. Always consider these medications as the cause of new-onset urinary incontinence, especially in older adults.

Some medications change the color of urine. For example, phenazopyridine (Pyridium) colors the urine a bright orange to rust; amitriptyline causes a green or blue discoloration, whereas levodopa discolors the urine to brown or black. Cancer chemotherapy drugs also color the urine and are often toxic to the bladder and/or kidneys. Patients with impaired kidney function require dosage adjustments in medications excreted by the kidneys.

Diagnostic Examination: Examination of the urinary system influences micturition. Some procedures such as an intravenous pyelogram (IVP) require patients to limit fluids before the test. A restriction in fluid intake commonly lowers urine output. Diagnostic examinations (e.g., cystoscopy) involving direct visualization of urinary structures cause localized edema of the urethral passageway and spasm of the bladder sphincter. After the procedure, a patient may have difficulty voiding or have red or pink urine because of trauma to the urethral or bladder mucosa.

Alterations in Urinary Elimination

Most patients with urinary problems are unable to store urine or fully empty the bladder. These disturbances result from impaired bladder function, obstruction to urine outflow, or inability to voluntarily control micturition.

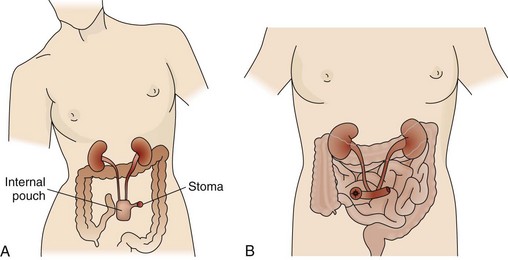

Some patients may have permanent or temporary changes in the normal pathway of urinary excretion. The surgical formation of a urinary diversion temporarily or permanently bypasses the bladder and urethra as the exit routes for urine. Permanent urinary diversions are often necessary in the patient with cancer of the bladder. The patient with a urinary diversion has a stoma (artificial opening) on the abdomen to drain urine. He or she has many special needs because urine drains to the outside through a stoma.

Urinary Retention: Urinary retention is an accumulation of urine resulting from an inability of the bladder to empty properly. Normally urine production slowly fills the bladder and prevents activation of stretch receptors until it distends to a certain level of stretch. The micturition reflex occurs, and the bladder empties. In urinary retention the bladder is unable to respond to the micturition reflex and thus is unable to empty. Urine continues to collect in the bladder, stretching its walls and causing feelings of pressure, discomfort, tenderness over the symphysis pubis, restlessness, and diaphoresis (sweating).

As retention progresses, retention with overflow develops. Pressure in the bladder builds to a point at which the external urethral sphincter is unable to hold back urine. The sphincter temporarily opens to allow a small volume of urine (25 to 60 mL) to escape. As urine exits, the bladder pressure falls enough to allow the sphincter to regain control and close. With retention a patient may void small amounts of urine 2 or 3 times an hour with no real relief of discomfort or may continually dribble urine. Be aware of the volume and frequency of voiding to assess for urinary retention. Assess the abdomen for evidence of bladder distention and tenderness.

In acute retention key signs are bladder distention and absence of urine output over several hours. A patient under the influence of anesthetics or analgesics often feels only pressure, but the alert patient has severe pain as the bladder distends beyond its normal capacity. In severe urinary retention the bladder holds as much as 2000 to 3000 mL of urine. Retention occurs as a result of urethral obstruction, surgical or childbirth trauma, and alterations in motor and sensory innervation of the bladder such as occurs with neuropathy secondary to diabetes. It may occur after removal of an indwelling catheter. Medication side effects or anxiety may also result in urinary retention. If a patient cannot void or completely empty the bladder, he or she must be catheterized because a UTI, kidney stones, and hyperreflexia can occur.

Retained or residual urine, also referred to as postvoid residual (PVR), occurs if a patient has urinary retention or cannot empty the bladder completely. You can use a portable noninvasive bladder ultrasound device (bladder scanner) or the technique of straight/intermittent catheterization to assess for PVR. Bladder scanners are often not readily available for nurses to use in all clinical settings, and straight/intermittent catheterization may be the only means to determine bladder urine volume. Regardless of the method used to determine PVR, assess the amount of urine left in the bladder within 10 to 15 minutes after a patient voids (Altschuler and Diaz, 2006). Instruct the patient not to void again before measurement. At least two residuals should be obtained since a patient may empty well one time and not the next. Spastic bladders and some medications and problems such as using a bedpan or not sitting upright to void cause inconsistent emptying. In normal micturition or in a normal void the bladder should empty completely.

Urinary Tract Infections: UTI is the most common health care–acquired infection; 80% of these infections result from the use of an indwelling urethral catheter (Lo et al., 2009). Catheterization results in over 1 million UTIs each year in the United States (Matteucci and Walsh, 2011). Infection frequently occurs after placement of urinary catheters, and each day a catheter is in place there is a 5% increase in bacteria in the urine (Saint et al., 2009). Catheter-associated UTIs (CAUTIs) are associated with increased hospitalizations, increased morbidity and mortality, longer hospital stay, and increased hospital costs (Newman, 2007). Each episode of CAUTI and ensuing complications are estimated to cost between $600 and $2800 (Saint et al., 2009). Because a CAUTI is common, costly, and believed to be reasonably preventable, as of October 1, 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) chose it as one of the complications for which hospitals no longer receive additional payment to compensate for the extra cost of treatment (Saint et al., 2009). Consequently there has been a shift in reimbursement practices from its traditional focus on early recognition and prompt treatment to one of prevention (Wilson et al., 2009).

Although several different microorganisms cause CAUTIs, the patient’s own colonic flora, including Escherichia coli, remains the most common causative pathogen (Ksycki and Namias, 2009). Bacteriuria (bacteria in the urine) leads to the spread of organisms into the kidneys and possibly to bacteremia or urosepsis (bacteria in the bloodstream) (Lewis et al., 2011). Microorganisms commonly enter the urinary tract through the ascending urethral route. Bacteria inhabit the distal urethra and external genitalia in men and women and the vagina in women. Organisms enter the urethral meatus easily and travel up the inner mucosal lining to the bladder. Women are more susceptible to infection because of a short urethra and the proximity of the anus to the urethral meatus. In men prostatic secretions containing an antibacterial substance and the length of the urethra reduce the susceptibility to UTIs. However, men are at increased risk for infection-related renal disease. Older adults and patients with progressive underlying disease or decreased immunity are also at increased risk.

In a healthy person with good bladder function, organisms are flushed out during voiding. Residual (retained) urine in the bladder becomes more alkaline and is an ideal site for microorganism growth. Any condition resulting in urinary retention such as a kinked, obstructed, or clamped catheter increases the risk of a UTI.

Poor perineal hygiene is another cause of UTIs in women. Inadequate handwashing, failure to wipe from front to back after voiding or defecating, and frequent sexual intercourse predispose women to infection.

Patients with lower UTIs have pain or burning during urination (dysuria) as urine flows over inflamed tissues. Fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, and malaise develop as an infection worsens. An irritated bladder (cystitis) causes a frequent and urgent sensation of the need to void. Irritation to bladder and urethral mucosa results in blood-tinged urine (hematuria). The urine appears concentrated and cloudy because of the presence of white blood cells (WBCs) or bacteria. If infection spreads to the upper urinary tract (kidneys—pyelonephritis), flank pain, tenderness, fever, and chills are common.

Another common cause of infection is the introduction of instruments into the urinary tract. For example, the introduction of a catheter through the urethra provides a direct route for microorganisms (Nazarko, 2008). With an indwelling catheter bacteria ascend along the outside of the catheter on the urethral wall or travel up its lumen. Local irritation to the urethra or bladder predisposes tissues to bacterial invasion.

Urinary Incontinence: Urinary incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine that is sufficient to be a problem. It can be either temporary or permanent, continuous or intermittent. Urinary incontinence related to urinary causes is called either stress or urge urinary incontinence (Palmer and Newman, 2007). Urge incontinence is more common in younger women and may be caused by local irritating factors such as UTIs (Ebersole et al., 2008). Individuals sense the urge to urinate but cannot keep from urinating long enough to reach a toilet. Stress incontinence occurs more often in older women when intraabdominal pressure exceeds urethral resistance. Muscles around the urethra become weak; thus even a small amount of urine may leak spontaneously (Ebersole et al., 2008). Some patients may have a mixed form of incontinence that has features of both stress and urge urinary incontinence. Table 45-5 on p. 1060 describes the types of urinary incontinence, their symptoms, and treatment interventions. Hyperactive or overactive bladder (OAB) is associated with individuals of all ages, but older adults are more likely to have incontinence associated with it following physical and cognitive decline associated with aging and effects of medications (Stewart, 2010). OAB results from sudden, involuntary contraction of the muscles of the urinary bladder, resulting in an urge to urinate (urge incontinence). Common abnormalities of the nervous system that cause OAB include cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and other head injuries, spinal cord injury, and diabetic neuropathy. Other causes include UTI and anxiety.

Approximately 15% to 30% of adult women experience urinary incontinence. It is present in as many as 30% to 70% of nursing home residents and in 30% of adults living at home (Touhy and Jett, 2010). Incontinence can impair body image and often leads to a loss of independence. Clothing becomes wet with urine, and the accompanying odor adds to the embarrassment. As a result, patients with this problem often avoid social activities. They often fail to discuss this condition with health care providers or nurses, and as a result urinary incontinence is underreported and undertreated. Resources for information about continence care, patient education, and treatment are available at the following websites: the Society for Urological Nurses and Associates (http://www.suna.org), the National Association for Continence (http://www.nafc.org), and the Simon Foundation (http://www.simonfoundation.org).

Physical limitations and environmental barriers are risks for incontinence. People with restricted mobility have greater chances of being incontinent because of their inability to reach toilet facilities in time. Low-set chairs and beds raised well above the floor are obstacles for people who must get up to reach a toilet. Some patients often lack the energy to walk very far at one time. The toilet is sometimes too far away for patients with urge incontinence. Patients who have difficulty undoing buttons or manipulating zippers face another obstacle.

Continued episodes of incontinence is a risk for impaired skin integrity. The character of urine changes when it remains in contact with skin, causing skin breakdown. The immobilized patient with frequent incontinence is especially at risk for pressure ulcers (see Chapter 48). Additional health care and patient education resources are available at the websites for the American Geriatrics Society (http://www.americangeriatrics.org) or the American Urogynecologic Society (http://www.augs.org).

Urinary Diversions: Conditions such as bladder cancer, radiation injury to the bladder, or chronic urinary infections may necessitate a urinary diversion to drain urine from a diseased or dysfunctional bladder. There are two types of continent urinary diversions (Fig. 45-4, A). One is a continent urinary reservoir that is created from a distal portion of the ileum and proximal portion of the colon. The ureters are embedded in the reservoir. This reservoir is situated under the abdominal wall and has a narrow ileal segment brought out through the abdominal wall to form a small stoma. The ileocecal valve creates a one-way valve in the pouch through which a catheter is inserted to empty the urine from the pouch. Patients must be willing and able to catheterize the pouch 4 to 6 times a day for the rest of their lives.

The second continent urinary diversion is an orthotopic neobladder that also uses an ileal pouch to replace the bladder. Anatomically the pouch is in the same position where the bladder was before removal, allowing patients to void normally.

Incontinent urinary diversions are less commonly performed. The surgery involves connecting the ureters to a section of the intestinal ileum with formation of a stoma on the abdominal wall (Fig. 45-4, B). Urine drains continuously because a patient has no sensation or control over urinary output, requiring the application of a collection pouch at all times.

Some patients need urinary drainage directly from one or both kidneys. In this case a tube is placed directly into the renal pelvis. This procedure is called a nephrostomy.

Any urinary diversion poses threats to a patient’s body image. The patient must learn how to manage the diversion, and those who do not have a continent urinary diversion must wear an artificial device at all times. However, most patients are able to wear normal clothing, engage in physical activity, travel, and have sexual relations. Care must be taken not to pull on tubing, especially in a nephrostomy, since it can be pulled out, causing tissue and organ damage and infection. Most nephrostomies are sutured into the kidney.

Refer patients with a urinary diversion to an ostomy nurse (a nurse with specialized education in this area). This specialist is a valuable resource for assisting a patient and family with matters pertaining to all aspects of care. The ostomy nurse often meets with the patient and family before surgery. In addition, refer the patient to the United Ostomy Associations of America (http://www.uoaa.org). This organization provides information about support groups to enhance coping and adaptation to lifestyle and body-image changes.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Urinary elimination is a basic function and is usually a private process. Many patients need physiological and psychological assistance from the nurse. Whether a patient has an actual or potential urinary problem, be sensitive to his or her elimination needs. You need knowledge of concepts beyond the anatomy and physiology of the urinary system to give appropriate care. In addition, you need to understand and apply knowledge about infection control principles.

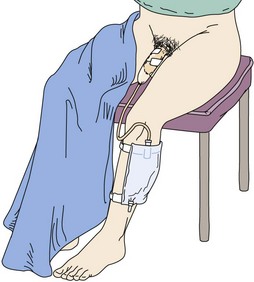

Infection Control and Hygiene

The urinary tract is sterile. Use infection control principles to help prevent the development and spread of UTIs and treat existing infections. E. coli, a common bacteria found in feces, causes many CAUTIs. Infection can occur in any location of the urinary tract. Apply knowledge of medical and surgical asepsis when providing care involving the urinary tract or external genitalia (see Chapter 28). Any invasive procedure of the urinary tract such as catheterization requires sterile technique. Procedures such as perineal care or examination of the genitalia require medical asepsis, including proper hand hygiene. Use medical asepsis by wiping off tubing with antiseptic wipes when changing from a large-volume urinary bag to a small-volume leg bag.

Factors Influencing Urination

Factors in a patient’s history that normally affect urination are age, environmental factors, medication history, psychological factors, muscle tone, fluid balance, current surgical or diagnostic procedures, and presence of disease conditions. Be alert to individual needs related to normal changes of aging that predispose older adults to certain elimination problems (Box 45-2). Also assess the bowel elimination pattern because constipation often interferes with normal urine elimination (see Chapter 46). Problems with urination also stem from dehydration. Evaluate environmental barriers in the home or health care setting. Aids such as elevated toilet seats, grab bars, or a portable commode are often necessary to ensure patient safety.

Growth and Development

Growth and development factors determine a patient’s ability to control the act of urination during the life span. Infants and young children cannot effectively concentrate urine. Their urine appears light yellow or clear. In relation to their small body size, infants and children excrete large volumes of urine. For example, a 6-month-old infant who weighs 13 to 18 pounds (6 to 8 kg) excretes 400 to 500 mL of urine daily.

The neurological system is not well developed until 2 to 3 years of age in a normal toddler. Until this age he or she is not able to associate the sensations of bladder filling and urination. A child must be able to recognize the feeling of bladder fullness, to hold urine for 1 to 2 hours, and to communicate the sense of urgency. Many toddlers are then able to control the external sphincter, and toilet training begins. Daytime control of urination is easier to accomplish than nighttime control and occurs earlier in the child’s development, usually by 2 to 3 years of age. Some children do not gain full control until age 4 or 5. Occasional daytime accidents or nocturnal enuresis (nighttime voiding without awakening) sometimes continue until age 5 (see Chapter 12).

During pregnancy urinary frequency is common, and susceptibility to UTI increases. Temporary or permanent changes resulting from repeated deliveries or hormonal changes often result in decreased perineal muscle tone, leading to urgency and stress incontinence.

Aging often impairs micturition. In men prostate enlargement usually begins during the 40s and continues throughout life, resulting in urinary frequency and possible urinary retention. In women changes in the urethral mucosa associated with loss of estrogen during and after menopause contribute to increased susceptibility to UTIs (Palmer and Newman, 2007).

Changes in kidney and bladder function also occur with aging. The ability of the kidney to concentrate urine declines. The older adult often experiences nocturia. The bladder loses muscle tone, and capacity decreases, resulting in increased urinary frequency. Because the bladder cannot contract effectively, an older adult often retains urine in it after voiding. These changes increase the risk for bacterial growth and development of UTIs.

Muscle Tone

Weak abdominal and pelvic floor muscles impair the ability of the urinary sphincter to maintain tone during increased abdominal pressure. Poor control of micturition or incontinence results from muscle wasting caused by prolonged immobility, muscle damage during vaginal childbirth, being overweight, caffeine use because caffeine relaxes the smooth muscle of the sphincter, muscle atrophy secondary to menopause, or other traumatic damage to pelvic nerves and muscles.

Critical Thinking

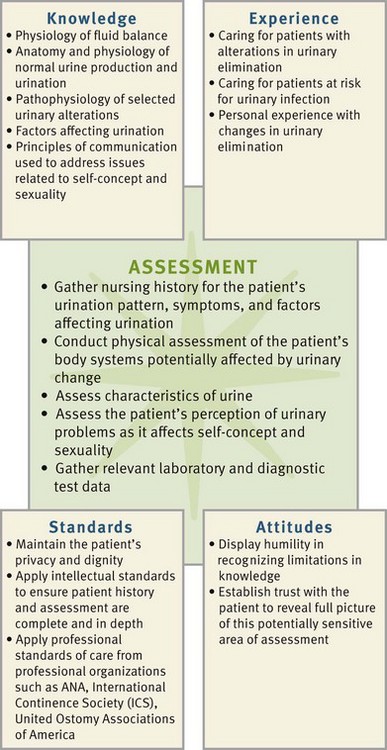

Successful critical thinking requires synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from patients, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require you to collect necessary information, analyze the data, and anticipate and make decisions regarding patient care.

During assessment consider all elements that build toward making appropriate nursing diagnoses. In the case of urinary elimination, integrate knowledge from nursing and other disciplines, previous experiences, and information gathered from patients to understand the process of urinary elimination and the impact on a patient and family. As a result, you are able to identify the unique impact of these problems on patients and families.

In addition, use critical thinking attitudes such as perseverance to find a plan of care to provide successful management of urinary elimination problems. Professional standards provide valuable directions for management. You are in a key position to serve as a patient advocate by suggesting noninvasive alternatives to catheterization use (e.g., the use of a bladder scanner to evaluate urine volume without invasive instrumentation or implementation of a voiding schedule for the incontinent patient).

When planning and implementing care for the patient with alterations in urinary elimination, also use standards developed by professional organizations such as the American Nurses Association (ANA), the International Continence Society (ICS), and the United Ostomy Associations of America as a guide for individualized patient care.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in the care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

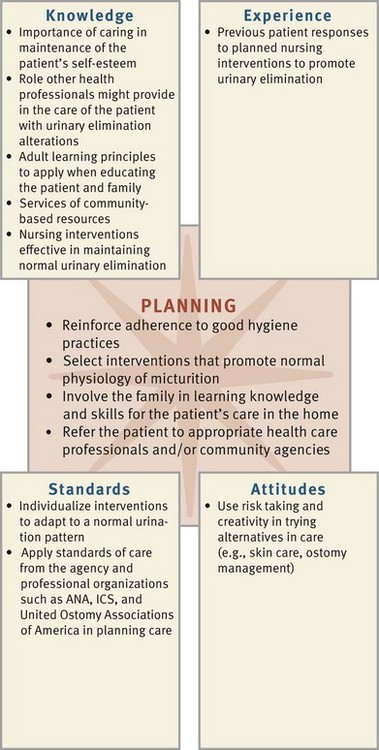

Assessment

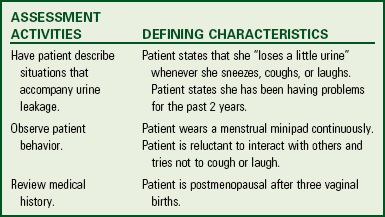

During the assessment process, thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

Throughout the assessment process it is important to consider the patient’s frame of reference of his or her illness experience. Also consider whether the patient understands his or her health status along with his or her self-care ability. Value the patient’s expertise with his or her own health and symptoms. Consider the patient’s cognitive ability to understand the signs and symptoms of the illness. Remember that you are in partnership with the patient or designated surrogates in planning, implementing, and evaluating care. Always ask what he or she expects from care. Does the patient expect that the UTI will be resolved?

Make sure that your approach to a patient’s elimination needs considers personal, social, and gender habits. Be sensitive and ask questions in a straightforward manner. Gender influences positioning for urination: males stand, whereas females sit. Place patients in a position of comfort. Some men who cannot stand to urinate become overly distressed. Gender differences also affect risk factors associated with urinary alterations. If a patient prefers privacy, try to prevent interruptions as he or she voids. Treat all patients with understanding and acceptance.

Be aware of your own attitudes and values about working with patients from diverse ethnic, social, and cultural backgrounds. Know that culture influences the choice of appropriate nursing interventions. In some cultures the embarrassment related to urinary elimination problems is so great that many patients, especially women, refuse to seek treatment. In some cultures patients prefer to squat over a receptacle rather than sit on one. Culture dictates when and where it is appropriate to urinate. It also determines whether it is proper for a male to care for the urinary needs of a female or if gender-congruent care is needed (see Chapter 9).

Identifying Urinary Alterations

To identify a urinary elimination problem and gather data for a care plan, use scientific and nursing knowledge, conduct a nursing history, perform a physical assessment, assess the patient’s urine, and review information from diagnostic tests and examinations. Use critical thinking to synthesize this information as assessment proceeds (Fig. 45-5). Adequate assessment results in the formulation of nursing diagnoses appropriate for alterations in urinary elimination. When assessing for problems with urinary elimination, be aware of the impact of the patient’s culture and language in the assessment process (Box 45-3).

Nursing History

The nursing history includes a review of a patient’s elimination patterns and symptoms of urinary alterations and an assessment of other factors that possibly affect the ability to urinate normally. Use questions to help direct the patient to focus on specific urinary problems (Box 45-4).

Pattern of Urination: Ask the patient about daily voiding patterns, including frequency and times of day, normal volume at each voiding, and any recent changes. Frequency varies among individuals and with intake and other types of fluid losses. The common times for urination are on awakening, after meals, and before bedtime. Most people void an average of 5 or more times a day. Some patients who void frequently during the night may have renal disease, prostate enlargement, or cardiac disease. Information about the pattern of urination establishes a baseline for comparison.

Symptoms of Urinary Alterations: Certain symptoms specific to urinary alterations may occur in more than one type of disorder. During assessment ask the patient about any symptoms related to urination (Table 45-1). Also assess whether the patient is aware of conditions or factors that precipitate or aggravate symptoms and determine what the patient does when any of these symptoms occur.

TABLE 45-1

Common Types of Urinary Alterations

| SYMPTOMS | DESCRIPTIONS | CAUSES OR ASSOCIATED FACTORS |

| Urgency | Feeling of need to void immediately | Full bladder, bladder irritation or inflammation from infection, overactive bladder, psychological stress |

| Dysuria | Painful or difficult urination | Bladder inflammation, trauma or inflammation of urethral sphincter |

| Frequency | Voiding at frequent intervals (less than 2 hours) | Increased fluid intake, bladder inflammation, increased pressure on bladder (pregnancy), diuretic therapy |

| Hesitancy | Difficulty initiating urination | Prostate enlargement, anxiety, urethral edema |

| Polyuria | Voiding large amounts of urine | Excess fluid intake, diabetes mellitus or insipidus, use of diuretics, postobstructive diuresis |

| Oliguria | Diminished urinary output relative to intake (usually 400 mL/24 hr) | Dehydration, renal failure, UTI, increased ADH secretion, heart failure |

| Nocturia | Voiding one or more times at night | Excessive fluid intake before bed (especially coffee or alcohol), renal disease, aging process, prostate enlargement |

| Dribbling | Leakage of urine despite voluntary control of urination | Stress incontinence, overflow from urinary retention (e.g., from BPH) |

| Incontinence | Involuntary loss of urine | Multiple factors: Unstable urethra, loss of pelvic muscle tone, fecal impaction, neurological impairment, overactive bladder |

| Hematuria | Blood in urine | Neoplasms of kidney or bladder, glomerular disease, infection of kidney or bladder, trauma to urinary structures, calculi, bleeding disorders |

| Retention | Accumulation of urine in bladder, with inability of bladder to empty fully | Urethral obstruction (stricture), decreased sensory activity, neurogenic bladder, prostate enlargement, postanesthesia effects, side effects of medications (e.g., anticholinergics, opioids) |

| Residual urine | Volume of urine remaining after voiding (≥100 mL) | Inflammation or irritation of bladder mucosa from infection, neurogenic bladder, prostate enlargement, trauma, or inflammation of urethra |

ADH, Antidiuretic hormone; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Note the presence of an indwelling catheter. It places a patient at risk for infection, catheter blockage, or skin-care problems. Monitor fluid balance through regular intake and output (I&O) measurements (see Chapter 41). Patients with a urinary diversion sometimes need special assistance to maintain adequate urine elimination and skin care integrity.

Physical Assessment

A physical examination (see Chapter 30) provides you with data to determine the presence and severity of urinary elimination problems. The primary structures to assess include the skin and mucosal membranes, kidneys, bladder, and urethral meatus. Fluid intake and the pattern and amounts, which are objective data, are important to assess (see Chapter 41).

Skin and Mucosal Membranes: Observe the condition of the skin and mucosal membranes. Problems with urinary elimination are frequently associated with fluid and electrolyte disturbances. By assessing skin turgor and the oral mucosa you gather data about the patient’s hydration status. Urinary incontinence increases the risk for skin breakdown. Observe the perineum for rashes, blistering, irritation, and breakdown.

Kidneys: Nurses with advanced examination skills learn to palpate the kidneys during abdominal examination. The position, shape, and size of the kidneys reveal problems such as tumors; whereas tenderness indicates inflammation. Auscultation is sometimes performed to detect the presence of a renal artery bruit (sound resulting from turbulent blood flow through a narrowed artery).

Bladder: In adults the bladder rests below the symphysis pubis. When it is distended, it rises above the symphysis pubis at the midline of the abdomen and often extends to just below the umbilicus. On inspection you may note a swelling or convex curvature of the lower abdomen. Gently palpate the lower abdomen. The partially filled bladder normally feels smooth and rounded. Gentle palpation on a distended bladder causes the patient to feel the urge to urinate, tenderness, or even pain. Percussion of a full bladder yields a dull percussion note.

Urethral Meatus: Observe the urinary meatus for any discharge, inflammation, and lesions. To examine the female, a dorsal recumbent position provides full exposure of the genitalia. While wearing clean gloves, retract the labial folds to see the urethral meatus. Normally it is pink, it appears as a small slitlike opening below the clitoris and above the vaginal orifice, and there is no discharge; if discharge is present, obtain specimens of urethral discharge before the patient voids.

Women with vaginal infections are susceptible to UTIs because it is easy for the drainage to travel to the urethral meatus. If yeast (candidiasis) is found in urine, it is important to inspect the vagina, in the groin area, under the breasts, and in the mouth for the source. It needs to be treated to keep UTI from yeast recurring. Older women may have vaginitis as a result of estrogen deficiency. Inspect the vaginal orifice carefully for signs of inflammation and describe any drainage.

A man’s urethral meatus is normally a small opening at the tip of the penis. Inspect the meatus for discharge, inflammation, and lesions. It is necessary to retract the foreskin in uncircumcised men to see the meatus. Wear clean gloves when retracting the foreskin. Be sure to replace it after the examination is complete to prevent swelling of the tissue around the glans of the penis.

Assessment of Urine

Assessment of urine involves measuring patients’ fluid I&O and observing characteristics of their urine.

Intake and Output: Assess the patient’s average daily fluid intake. If you need an accurate measurement of fluid intake from the patient who is at home, ask him or her to estimate his or her intake by showing a measurement on a commonly used glass or cup.

In a health care setting measure a patient’s fluid intake either when the health care provider orders I&O measurements or when you judge that measurement is needed (see Chapter 41). A change in urine volume is a significant indicator of fluid alterations or kidney disease. While caring for the patient, use a graduated receptacle to measure urinary output from a bedpan or urinal after each voiding. Special receptacles (urimeters) that attach between indwelling catheters and drainage bags are a convenient means of accurately measuring urine volume. A urimeter holds 100 to 200 mL of urine. After measuring urine from a urimeter, drain the cylinder into the urinary drainage bag or into a receptacle for disposal. Use urimeters when precise hourly measurements of urine are necessary.

When you measure urine from a drainage bag, the use of a separate plastic graduated measuring receptacle obtains a more precise measurement of urine output (Fig. 45-6). Each patient needs to have a graduated receptacle for his or her exclusive use to prevent potential cross-contamination. Label each container with patient name. The container needs to be rinsed after emptying, and the tubing that drains the bag securely clamped and cleaned with alcohol before putting it back in the holder.

Report any extreme increase or decrease in urine volume. An individual’s daily output generally ranges from 1200 to 1500 mL of urine (Hall, 2011). An hourly output of less than 30 mL for more than 2 consecutive hours is cause for concern. Similarly, you need to report consistently high volumes of urine (polyuria) (i.e., over 2000 to 2500 mL daily).

Characteristics of Urine: Inspect the patient’s urine for color, clarity, and odor.

Color: Normal urine ranges from a pale, straw color to amber, depending on its concentration. Urine is usually more concentrated in the morning or with fluid volume deficits. As a person drinks more fluids, urine becomes less concentrated.

Bleeding from the kidneys or ureters causes dark red urine; bleeding from the bladder or urethra causes bright red urine. Various medications and foods also change urine color. For example, phenazopyridine, a urinary analgesic, colors urine bright orange. Eating beets, rhubarb, or blackberries causes red urine. Special dyes used in intravenous diagnostic studies eventually discolor urine. Dark amber urine is the result of high concentrations of bilirubin caused by liver dysfunction. Document and report any abnormal color or sediment, especially if the cause is unknown.

Clarity: Normal urine appears transparent at voiding. Urine that stands in a container becomes cloudy. Freshly voided urine in patients with renal disease appears cloudy or foamy because of high protein concentrations. Urine may also appear thick and cloudy as a result of bacteria and WBCs.

Odor: Urine has a characteristic odor. The more concentrated the urine, the stronger the odor. Stagnant urine has an ammonia odor, which is common in patients who are repeatedly incontinent. A sweet or fruity odor occurs from acetone or acetoacetic acid (by-products of incomplete fat metabolism) seen with diabetes mellitus or starvation. Some food and medications can affect the odor of urine (e.g., asparagus and amoxicillin). A foul odor is often associated with a possible infection.

Urine Testing: Nurses often collect urine specimens for laboratory testing. The type of test determines the method of collection. Label all specimens with the patient’s name, date, and time of collection. Transport specimens to the laboratory in a timely fashion to ensure accuracy of test results. Agency infection control policies require the adherence to standard precautions by all personnel during specimen handling (see Chapter 34).

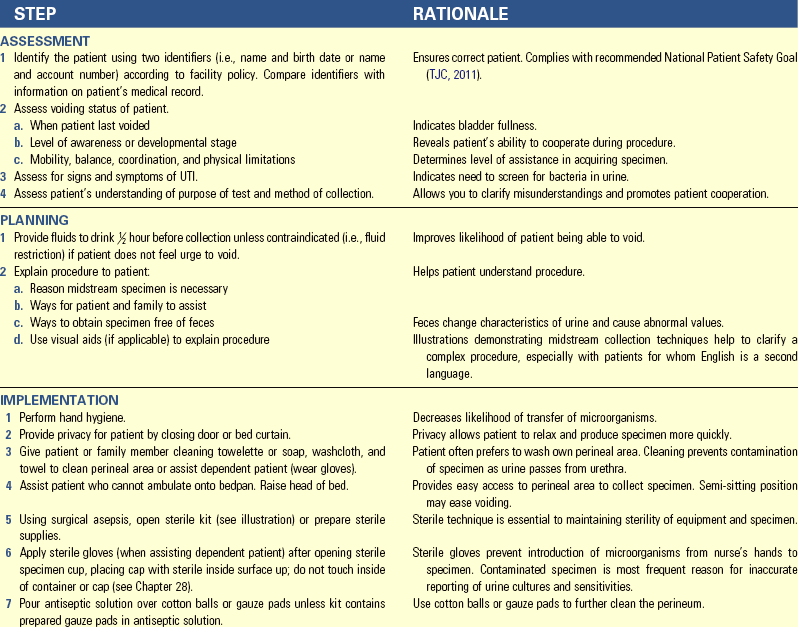

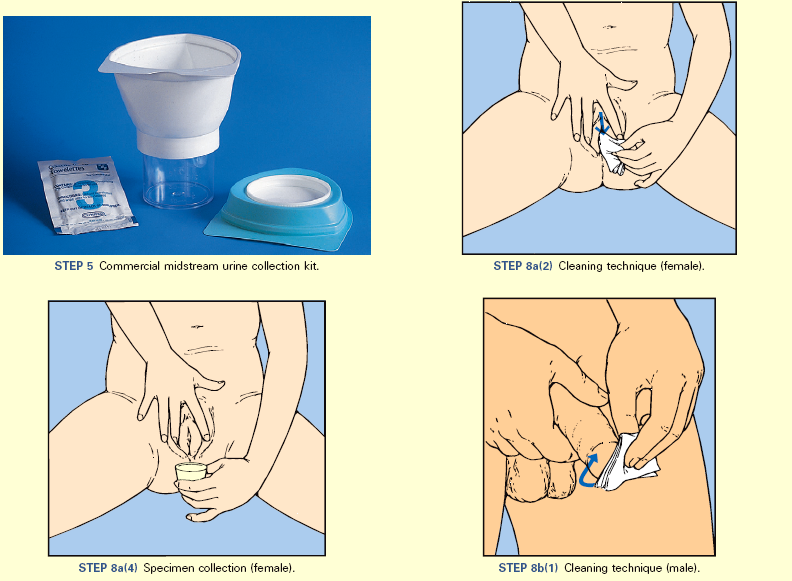

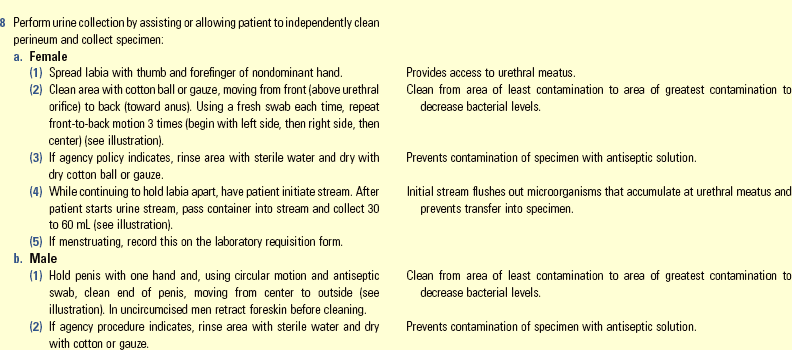

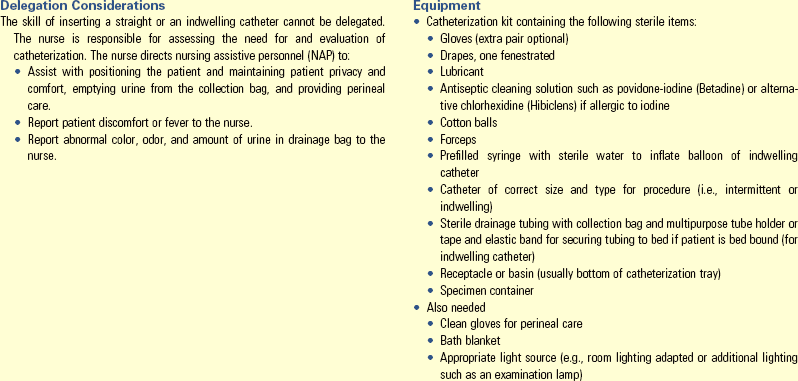

Specimen Collection: The nurse collects random, clean-voided or midstream, sterile, and timed specimens (Table 45-2). The method of collection varies based on a patient’s developmental level and the type of specimen ordered.

TABLE 45-2

| COLLECTION TYPE/USE OF SPECIMEN | NURSING CONSIDERATIONS |

| Random (routine urinalysis) | Collect during normal voiding or from an indwelling catheter or urinary diversion collection bag. Do not collect from an indwelling catheter drainage bag. Use a clean specimen cup. |

| Clean-voided or midstream (culture and sensitivity) | See Skill 45-1 on pp. 1068-1070. Use a sterile specimen cup. |

| Sterile specimen (culture and sensitivity) | If the patient has an indwelling catheter, collect a sterile specimen by using aseptic technique through the special sampling port (Fig. 45-7) found on the side of the catheter. |

| Clamp the tubing below the port, allowing fresh, uncontaminated urine to collect in the tube. After wiping the port with an antimicrobial swab, insert a sterile syringe hub and withdraw at least 3 to 5 mL of urine (check agency policy). | |

| Using sterile aseptic technique, transfer the urine to a sterile container (see Chapter 28). | |

| Timed urine specimens (for measuring levels of adrenocortical steroids or hormones, creatinine clearance, or protein quantity tests) | Time required may be 2-, 12-, or 24-hour collections. The timed period begins after the patient urinates and ends with a final voiding at the end of the time period. The patient voids into a clean receptacle, and the urine is transferred to the special collection container, which often contains special preservatives. Each specimen must be free of feces and toilet tissue. Missed specimens make the whole collection inaccurate. Check with agency policy and the laboratory for specific instructions. |

Urine Collection in Children: Specimen collection from infants and children is often difficult. Adolescents and school-age children are usually able to cooperate, although some are embarrassed. Preschool children and toddlers have difficulty voiding on request. It often helps to offer the child fluids 30 minutes before requesting a specimen. You need to use terms for urination that the child is able understand. A young child is often reluctant to void in unfamiliar receptacles. A potty chair or specimen hat placed under the toilet seat is usually effective. You will need to use special collection devices for infants or toddlers who are not toilet trained. You can attach clear plastic, single-use bags with self-adhering material over the child’s urethral meatus. Do not obtain specimens by squeezing urine from the diaper because the results will be inaccurate.

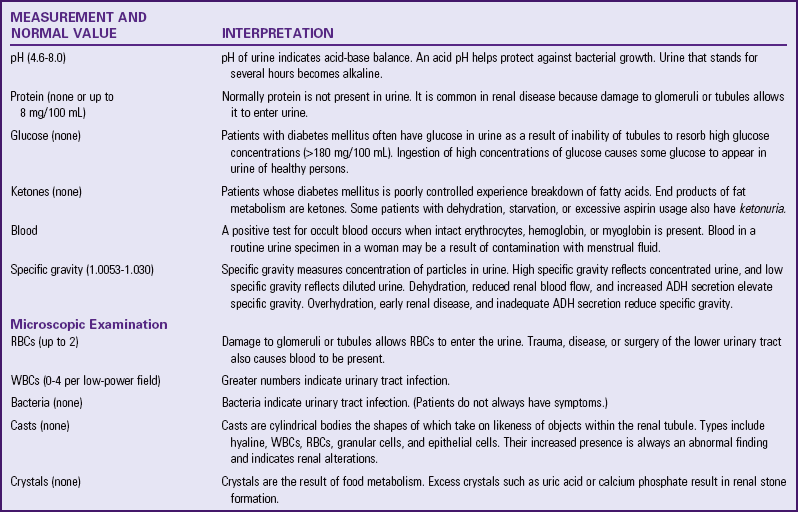

Urinalysis: The laboratory performs a urinalysis on a specimen obtained by any of the previously described methods. Table 45-3 lists normal values for a urinalysis. A lab examines specimens as soon as possible, preferably within 2 hours. Make sure that it is the first voided specimen in the morning to ensure a uniform concentration of constituents. For a quick screening perform certain portions of the urinalysis with special reagent strips. Dip the strips into the urine and observe for a color change in the time interval designated on the package (Fig. 45-8).

Specific Gravity: The specific gravity is the weight or degree of concentration of a substance compared with an equal volume of water. Pour a urine specimen into a special clean, dry cylinder. The weighted urinometer is suspended in the cylinder of urine. The concentration of dissolved substances in the urine aids in determination of a patient’s fluid balance. This measurement is always part of a complete urinalysis. Nurses in critical care units are often responsible for doing periodic measurements of urine specific gravity (see Table 45-3).

If questions regarding the accuracy of specific gravity measurements arise, obtain a urine osmolality test. Although both tests measure urine concentration, the osmolality test is more accurate because it measures the total number of particles in a solution (see Chapter 41).

Urine Culture: A urine culture requires a sterile or clean-voided sample of urine. It takes approximately 24 to 48 hours before the laboratory can report findings of bacterial growth. While awaiting results, a broad-spectrum antibiotic is sometimes ordered as soon as a culture has been obtained. The test for sensitivity determines which specific antibiotics are effective. The results (sensitivities) of a urine culture may show that another antibiotic would be more effective. In this case a new antibiotic is ordered.

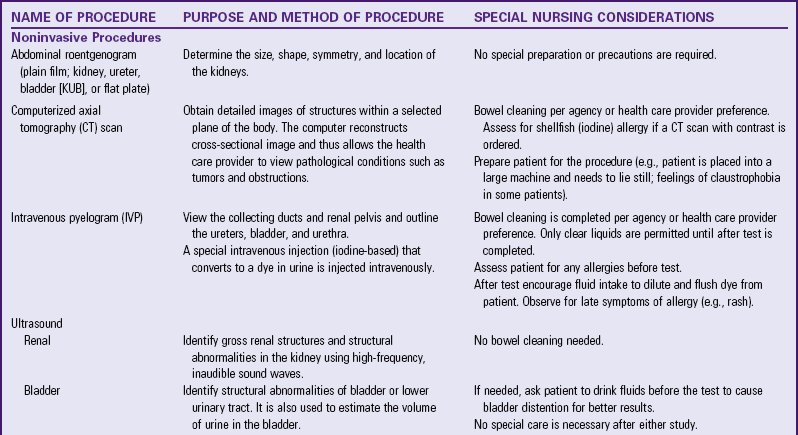

Diagnostic Examinations

The urinary system is one of the few organ systems amenable to accurate diagnostic study by several radiographic techniques. The two approaches for visualization of urinary structures, direct and indirect techniques, are either quite simple or very complex, requiring extensive nursing intervention. These procedures are further subdivided into invasive or noninvasive categories (Table 45-4).

TABLE 45-4

Modified from Pagana KD, Pagana TJ: Mosby’s diagnostic and laboratory test reference, ed 10, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.

Many of the nursing responsibilities related to diagnostic examinations of the urinary tract are common to many of the studies. The common responsibilities before the study include the following:

• Obtain a signed consent (check agency policy)

• Assess patient for history of any allergies and whether they have had a previous reaction to a contrast agent (Schabelman and Witting, 2010). Allergic individuals in general (including individuals with asthma) are at mildly increased risk for developing adverse reactions to radiocontrast media (Beaty, Lieberman, and Slavin, 2008).

• Administer bowel-cleaning medications as ordered (check agency policy)

• Ensure that patient receives appropriate pretest diet (clear liquids) or nothing by mouth (NPO) as needed

The common responsibilities following the study include the following:

Nursing Diagnosis

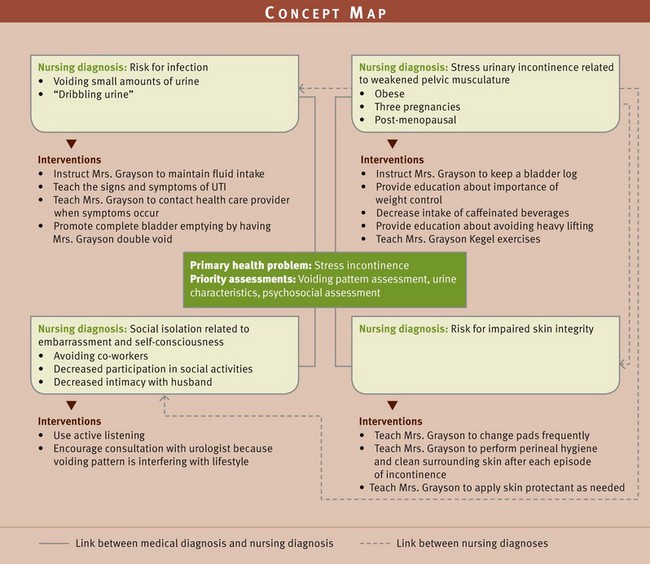

A thorough assessment of a patient’s urinary elimination function reveals patterns of data that allow a nurse to make relevant and accurate nursing diagnoses. Use critical thinking to reflect on knowledge of previous patients, apply knowledge of urinary function and the effects of disorders, review defining characteristics, and make a specific nursing diagnosis. Data from questions about the urinary system are important in identifying nursing diagnoses. The diagnosis focuses on a specific urinary elimination alteration or an associated problem such as impaired skin integrity related to urinary incontinence. Identification of defining characteristics leads to selection of an appropriate diagnosis. An important part of formulating nursing diagnoses is identifying the relevant causative or related factor. You choose interventions that treat or modify the related factor for the diagnosis to be resolved. Specifying related factors for each diagnosis allows selection of individualized nursing interventions (Ackley and Ladwig, 2011). For example, impaired skin integrity related to incontinence requires interventions such as a toileting schedule or assisting the patient to the toilet at frequent intervals. In contrast, impaired skin integrity related to inability to change positions requires interventions such as placing the patient on a turning schedule. Box 45-5 provides an example of diagnostic reasoning. Some nursing diagnoses common to patients with urine elimination alterations include the following:

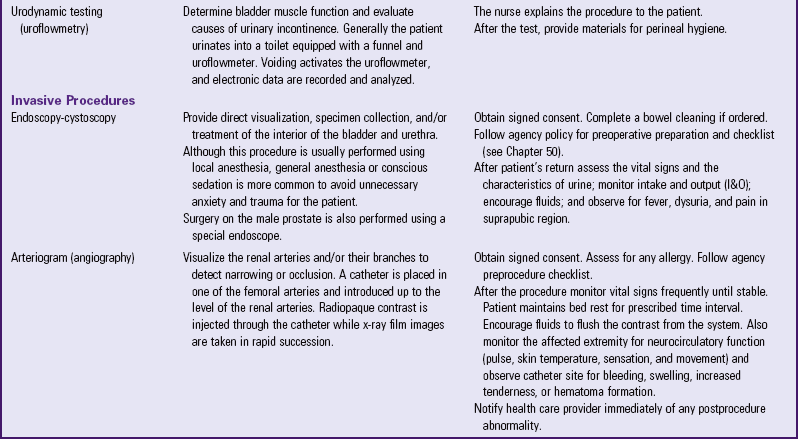

Planning

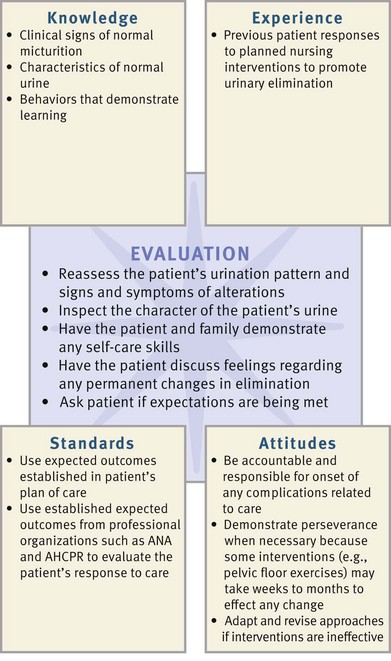

During planning integrate the knowledge from assessment and information about available resources and therapies to develop an individualized plan of care (see the Nursing Care Plan). Match the patient’s needs with clinical and professional standards recommended in the literature (Fig. 45-9). Building a relationship of trust with patients is important because the implementation of care involves interaction of a very personal nature.

FIG. 45-9 Critical thinking model for urinary elimination planning. ANA, American Nurses Association; ICS, International Continence Society.

Goals and Outcomes

The plan of care for urinary elimination alterations must include realistic and individualized goals along with relevant outcomes. The nurse and the patient need to collaborate in setting goals and outcomes and ultimately in choosing nursing interventions. A general goal is often normal urinary elimination; but sometimes the individual goal differs, depending on the problem. The goals are short or long term. For example, urinary retention following surgery requires a short-term goal: “Patient will have normal voiding with complete bladder emptying within 24 hours.” Relevant expected outcomes for this goal include the following:

• Patient will void within 4 hours.

• Urinary output of 300 mL or greater will occur with each voiding.

Conversely, the patient with stress incontinence often has a long-term goal that depends on weeks of pelvic floor muscle exercise to achieve urinary control: “Patient will achieve full urinary continence within 8 weeks after start of exercise program (Kegel).” Make sure that goals are reasonably achievable and relevant to the patient’s situation.

Setting Priorities

Urinary elimination is a personal and intimate activity. Establish a relationship with the patient that allows discussion and intervention. While you are collaborating with the patient, his or her priorities become apparent, and he or she should develop an understanding of all the goals.

When a patient has multiple nursing diagnoses (Fig. 45-10), it is important to recognize the primary health problem and its influence on other problems. In the example of the patient with chronic confusion, the resultant incontinence creates several risks. Focusing on the management of incontinence resolves more than one nursing diagnosis. Although physical needs appear to have higher priority, the psychological needs related to self-esteem or sexuality are sometimes a higher priority for the patient. Attention to the patient’s perceived needs is the most satisfactory and successful approach to accomplishing all the goals. Reinforcement of good health habits that are already followed improves compliance with the care plan.

Teamwork and Collaboration

Incorporate individualized health promotion activities and therapeutic interventions to meet the patient’s needs. Consider the patient’s home environment and normal elimination routines when planning therapies. Collaborate with several health care disciplines, the patient, and the patient’s family. For example, a nurse specialist in urinary continence teaches pelvic floor exercises, whereas a physical therapist designs an exercise plan to increase overall strength and endurance so the patient is able to ambulate to the bathroom. In addition, a health care provider prescribes an indwelling catheter. The nurse monitors the length of time that it is in place and communicates this to the health care provider. Explore the need for home care services and make the appropriate referrals. The family may need to alter the home environment to make it easier and safer for the patient to use the bathroom. The patient’s plan requires multiple interventions.

Implementation

Complete independent and collaborative interventions to help the patient achieve the desired outcomes and goals. The independent activities are those in which nurses use their own judgment. An example of this is teaching self-care activities to the patient. Collaborative activities are those prescribed by the health care provider and carried out by the nurse such as medication administration.

Health Promotion

Health promotion assists the patient in understanding and participating in self-care practices to preserve and protect healthy urinary system function. You can achieve this focus using several means.

Patient Education: Success of therapies aimed at eliminating or minimizing urinary elimination problems depends in part on successful patient education (Box 45-6). Although many patients need to learn about all aspects of urinary elimination, first focus the teaching on their specific elimination problems. For example, patients who practice poor hygiene benefit most from learning about normal sterility of the urinary tract and how frequent handwashing and proper perineal hygiene reduce the risks for infection. Patients also learn the significance of symptoms of urinary alterations so they can initiate early preventive health care.

You can easily incorporate teaching when giving nursing care. For example, a good time to discuss the benefits of increasing fluid intake is while giving fluids with medications or meals. Often you are more successful in teaching about perineal hygiene while giving a bath or performing catheter care.

Promoting Normal Micturition: Maintaining normal urinary elimination helps to prevent many urination problems. Many nursing measures promote normal voiding in patients at risk for urination difficulties and in those with established urination problems. Some of these measures are independent nursing interventions.

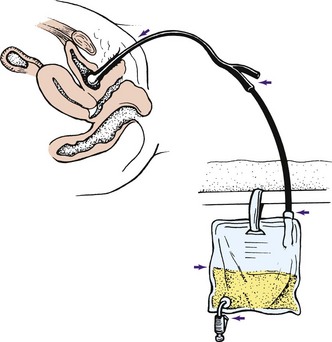

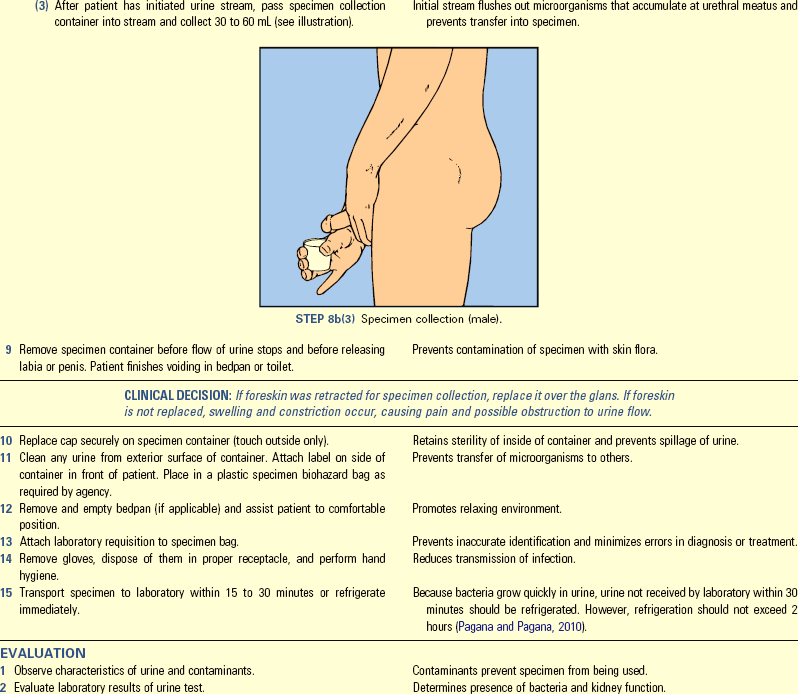

Stimulating Micturition Reflex: A patient’s ability to void depends on feeling the urge to urinate, being able to control the urethral sphincter, and being able to relax during voiding. Help patients learn to relax and stimulate the reflex to void by helping them assume the normal position for voiding. A woman is better able to void in a squatting or sitting position. If the patient is unable to use toilet facilities, position him or her in a squatting position on a bedpan (see Chapter 46) or bedside commode. A man voids more easily in the standing position. If the man cannot reach toilet facilities, have him stand at the bedside and void into a urinal (a metal or plastic receptacle for urine) (Fig. 45-11). At times it is necessary for one or more nurses to help a man stand.

Other measures that promote relaxation and the ability to void include sensory stimuli. The sound of running water helps many patients void through the power of suggestion. Stroking the inner aspect of the thigh stimulates sensory nerves and promotes the micturition reflex. You can also pour warm water over the patient’s perineum and create the sensation to urinate. If you need to measure urine output, first measure the volume of water that you pour over the perineal area.

Maintaining Elimination Habits: Many patients follow routines to promote normal voiding. In a hospital or long-term care facility health care routines often conflict with those of patients. Integrating patients’ habits into the care plan fosters normal voiding and helps prevent problems related to urination.

Maintaining Adequate Fluid Intake: A simple method of promoting normal micturition is maintaining optimal fluid intake. A patient with normal renal function who does not have heart or kidney disease needs to drink 2200 to 2700 mL of fluid daily. However, a minimal daily intake of 1200 to 1500 mL of fluids is usually adequate unless the patient has a history of UTI.

Increasing fluid intake helps flush out solutes or particles that collect in the urinary system. Because some patients are unwilling to drink 2500 mL of water daily, encourage fluids that the patient prefers. Many vegetables and fruits also have a high fluid content. At home it helps to set a schedule for drinking fluids (e.g., with meals or medications). To minimize nocturia, avoid fluids 2 hours before bedtime.

Promoting Complete Bladder Emptying: Under normal conditions a small amount of a patient’s urine remains in the bladder after voiding (residual urine). Encouraging patients to wait until urine stops flowing or to attempt to void again (double voiding) can improve bladder emptying (Table 45-5). Urinary retention care includes scheduled toileting (Lewis et al., 2011). In addition, Credé’s method or manual compression of the bladder walls with each attempted void may be used (Madineh, 2008). Instruct the patient to place both hands flat on the abdomen below the umbilicus and above the symphysis pubis with the fingers pointed down toward the bladder dome. Have him or her compress the hands downward against the walls of the bladder while tightening the perineum, contracting the abdominal wall, and holding the breath. The maneuver promotes bladder emptying by relaxing the urethral sphincter.

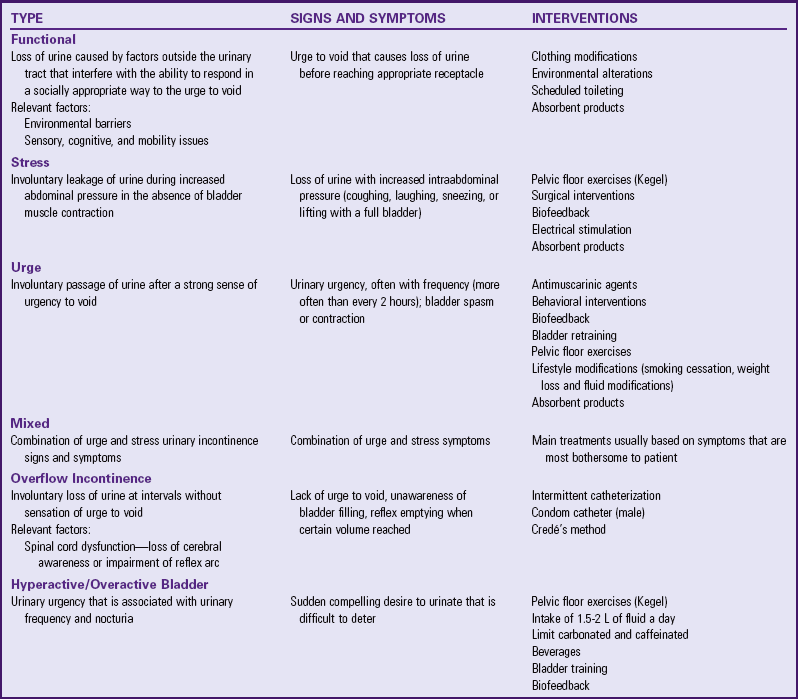

TABLE 45-5

Urinary Incontinence and Treatment Options

Modified from Palmer MH, Newman DK: Urinary incontinence and estrogen, Am J Nurs 107(3):35, 2007; Doughty DB: Urinary and fecal incontinence: current management concepts, ed 3, St Louis, 2006, Mosby; and McKertich K: Urinary incontinence: Assessment in women: Stress, urge or both? Aust Fam Physician 37(3):112, 2008.

Preventing Infection: One of the most important considerations is to prevent infection of the urinary system. Good perineal hygiene that includes cleaning the urethral meatus after each voiding or bowel movement is essential. A minimal daily fluid intake of 1200 to 1500 mL dilutes urine, promotes regular micturition, and flushes the urethra of microorganisms. Voiding after intercourse; not using excessive soap or taking bubble baths; wearing cotton underwear; and drinking enough fluids, especially fluids high in acid ash such as apple or cranberry juice help prevent UTI.

Acute Care

Maintaining Elimination Habits: Patients usually require time to void. Requesting a urine specimen on demand does not contribute to relaxation and normal voiding habits. Give patients at least 30 minutes to provide a specimen. Patients normally void on awakening or before meals; therefore offer the opportunity to use toilet facilities then. Also important is the need to respond to and anticipate patients’ urges to urinate. For example, many older-adult falls are related to the urge to urinate. Anticipate the need and provide for scheduled bathroom visits to help reduce the fall risk in these patients.

Many patients need privacy for voiding. If a patient cannot reach the bathroom and uses a bedside commode or bedpan, make sure that the bedside curtain is closed. Patients who are debilitated and live at home often prefer using a bedside commode screened by a partition or room divider. Young children are often unable to void in the presence of persons other than their parents.

When possible encourage the continued use of special measures that the patient uses to void. Some patients are able to relax and void more easily while reading or listening to music. Having a cup or glass of fluids also promotes urination.

Medications: Drug therapy given alone or with other therapies often helps problems of incontinence or retention. The bladder is innervated by the parasympathetic nervous system. Drugs that block the muscarinic receptors suppress bladder contractions and reduce incontinence caused by bladder irritation. Examples include solifenacin (Vesicare) and oxybutynin chloride (Ditropan). These medications can cause constipation, dry mouth, and skin irritation (Lehne, 2010). Irritants present in the urine such as caffeine or alcohol may cause uncontrolled bladder contractions, and thus patients should avoid them.

When the bladder empties, the detrusor muscle contracts in response to parasympathetic stimulation. Incomplete bladder emptying results from impaired innervation or weakness of the detrusor muscle. The patient experiences retention and possible overflow incontinence. Cholinergic drugs increase contraction of the bladder and improve emptying. Bethanechol (Urecholine) stimulates parasympathetic nerves to increase bladder wall contraction and relax the sphincter. You can administer bethanechol by subcutaneous or oral routes. Cholinergic drugs often cause diarrhea as a side effect (Lehne, 2010).

The dribbling or overflow incontinence seen in men with prostatic enlargement can be treated with an alpha1-adrenergic blocker such as tamsulosin (Flomax). Tamsulosin is given orally and relaxes prostatic smooth muscle, thus relieving obstructive symptoms. This drug has few side effects and does not cause transient hypotension as other alpha-adrenergic blockers do (Lehne, 2010).

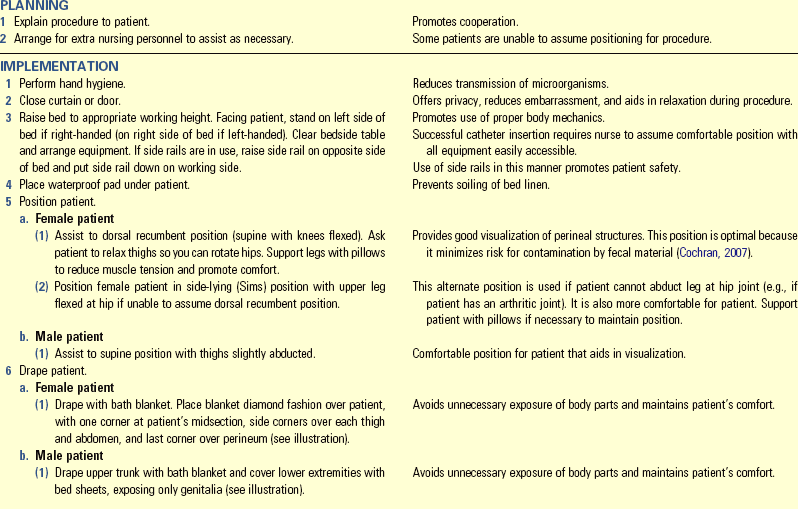

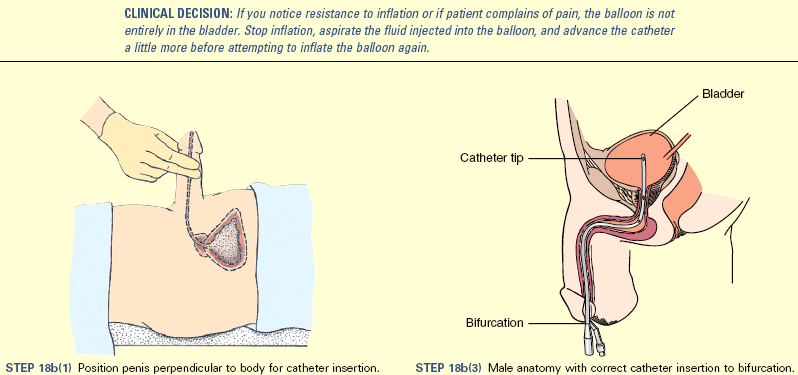

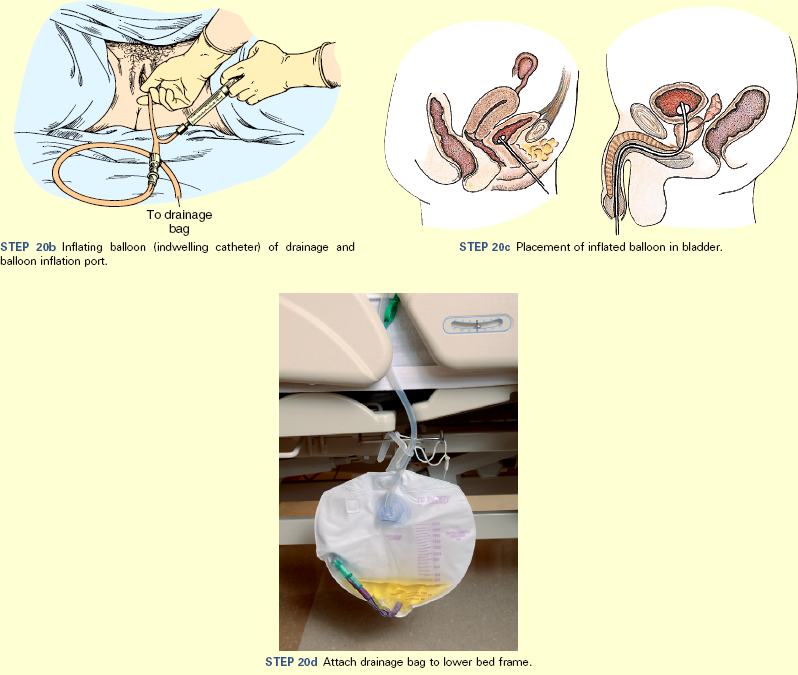

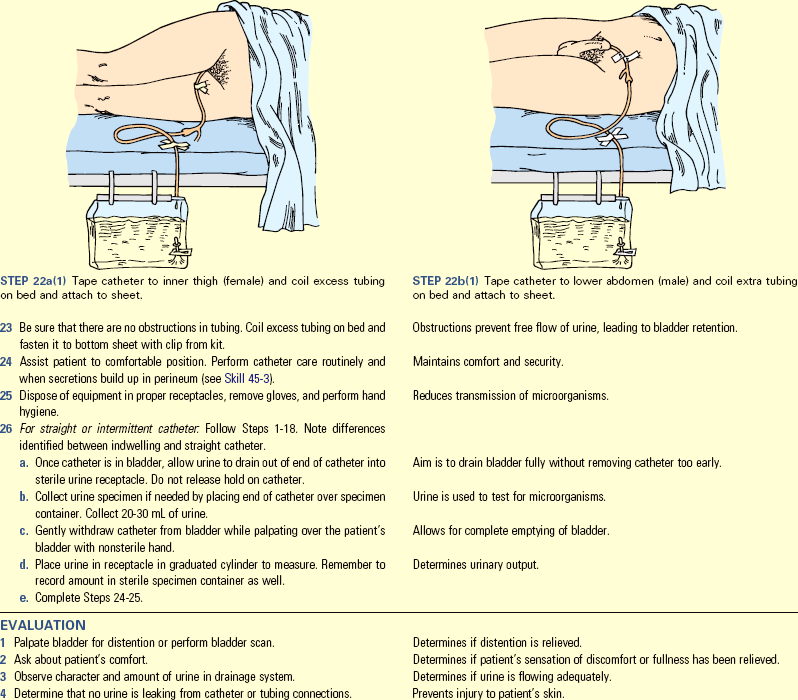

Catheterization: Catheterization of the bladder involves introducing a latex or plastic tube through the urethra and into the bladder. The catheter provides a continuous flow of urine in patients unable to control micturition or those with obstructions. It also provides a means of assessing urine output in hemodynamically unstable patients. Because bladder catheterization carries the risk of UTI, blockage, and trauma to the urethra, it is preferable to rely on other measures for either specimen collection or management of incontinence.

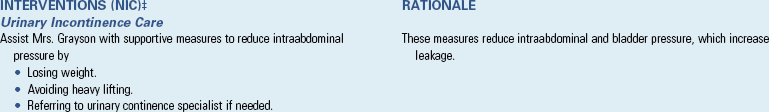

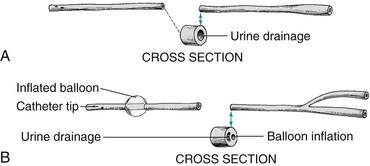

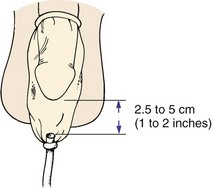

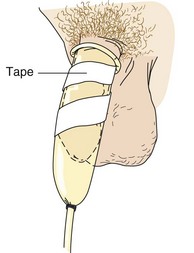

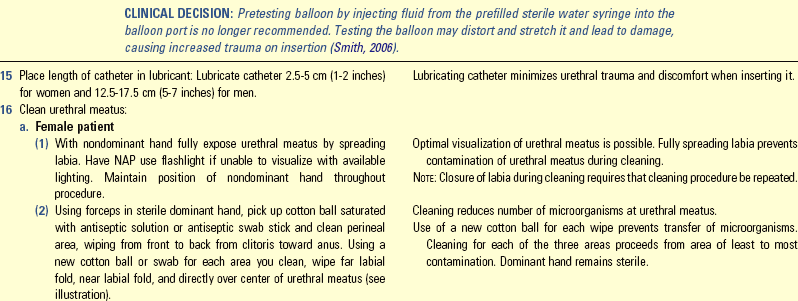

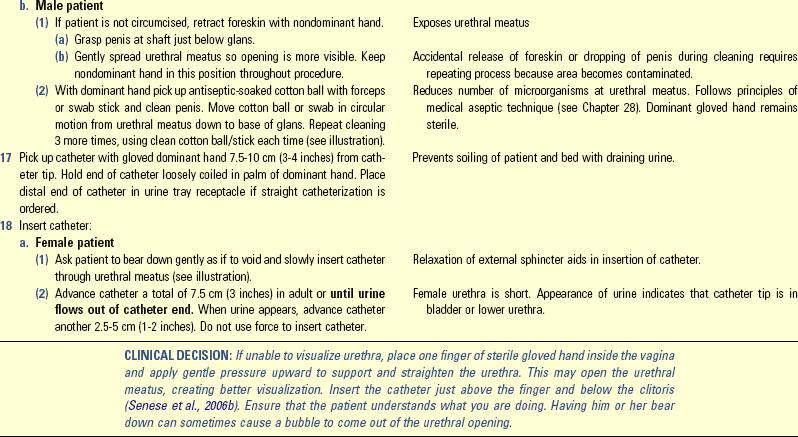

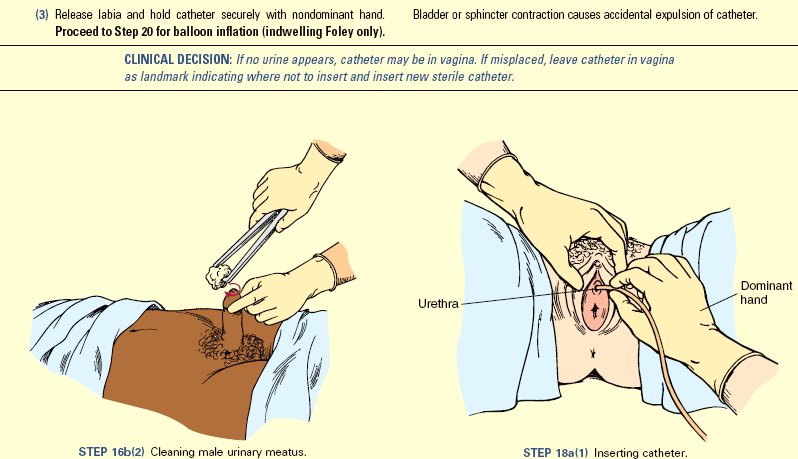

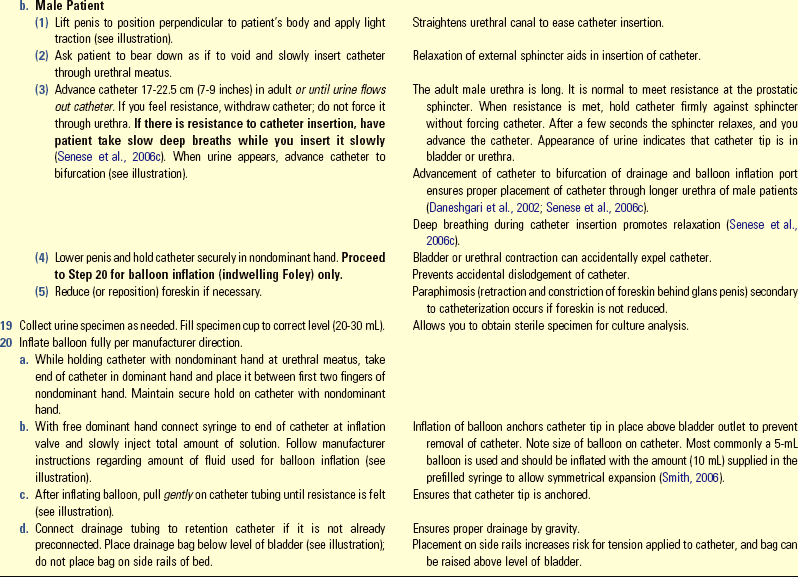

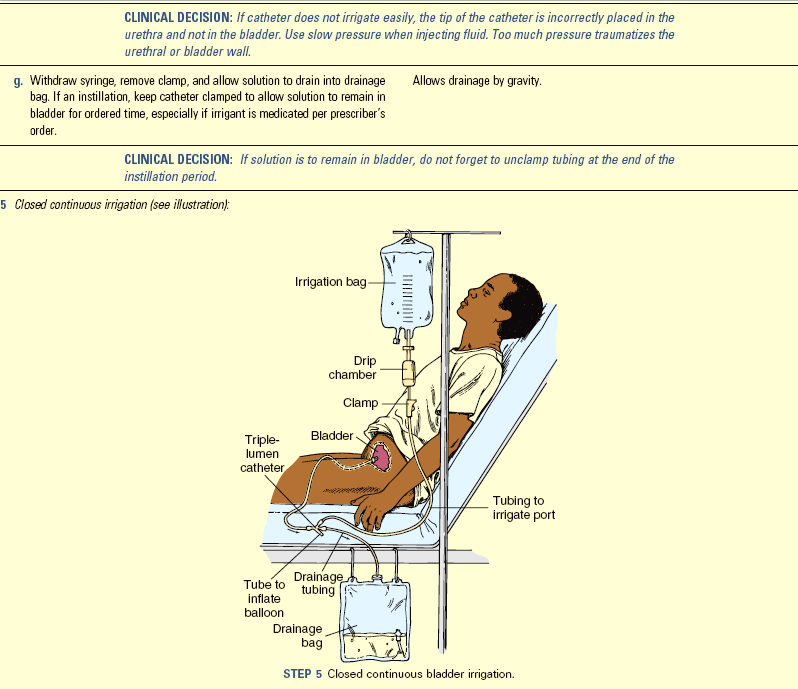

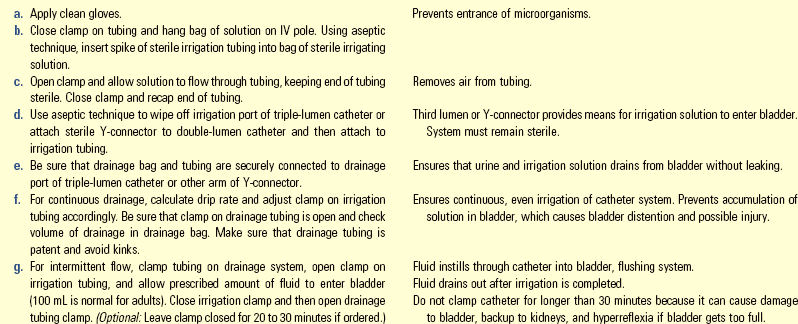

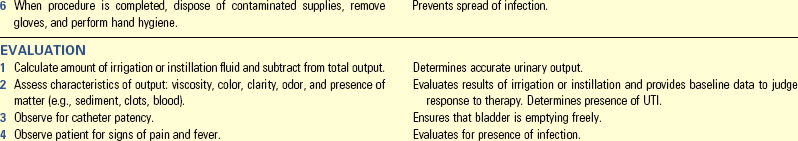

Types of Catheterization: Intermittent and indwelling retention catheterizations are the two forms of catheter insertion. With the intermittent technique you introduce a straight single-use catheter (Fig. 45-12, A) long enough to drain the bladder (5 to 10 minutes). When the bladder is empty, you immediately withdraw the catheter. You can repeat intermittent catheterization as necessary, but each catheter insertion increases risk of trauma and infection. It is common for people with spinal cord injury or other neurological problems such as multiple sclerosis to perform self–intermittent catheterization up to every 4 hours daily for months or years. If done correctly with use of clean technique, they frequently do not experience more UTIs; in fact, the UTI rate is lower than for patients with long-term indwelling catheters. An indwelling or Foley catheter (Fig. 45-12, B) remains in place for a longer period, until a patient is able to void voluntarily or continuous accurate urine measurements are no longer needed (Box 45-7).

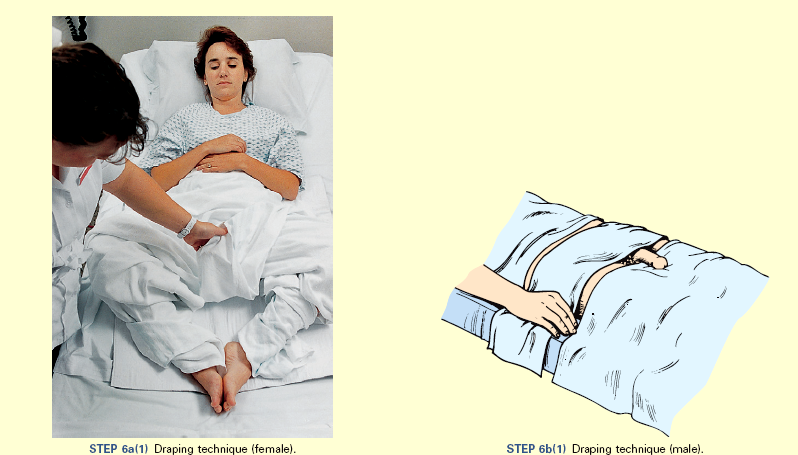

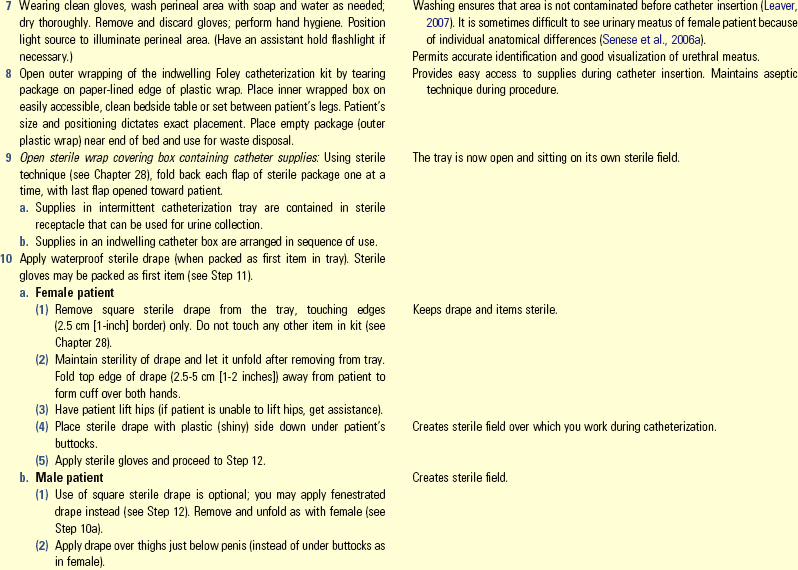

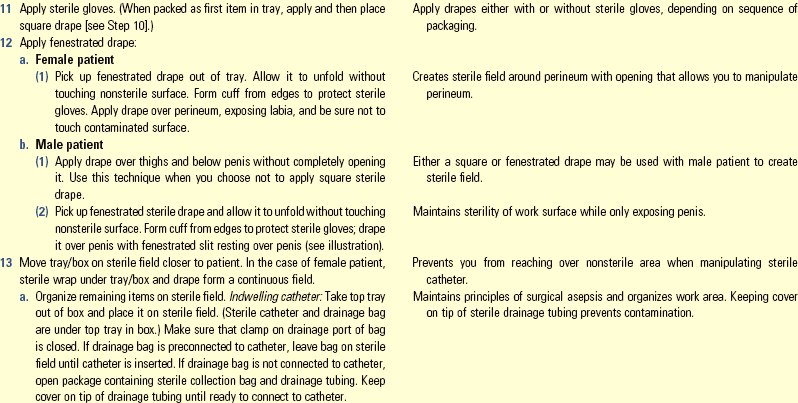

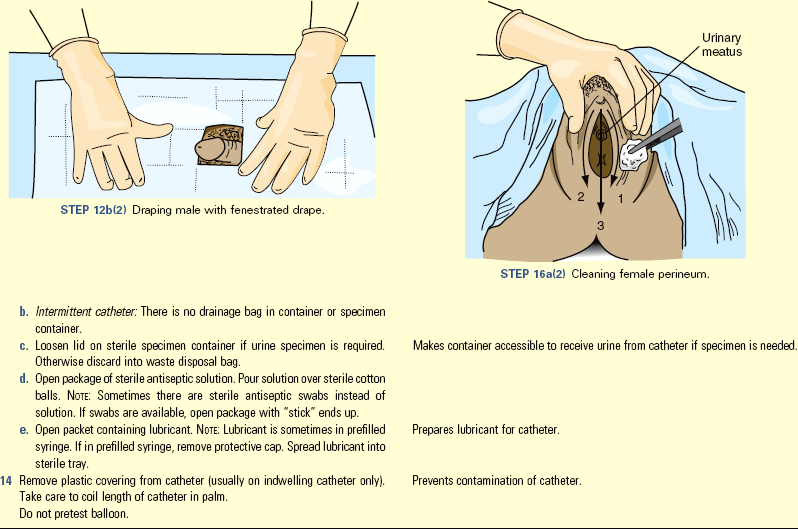

The straight single-use catheter has a single lumen with a small opening about 1.3 cm ( inch) from the tip. Urine drains from the tip, through the lumen, and to a receptacle. An indwelling Foley catheter has a small inflatable balloon that encircles the catheter just above the tip. When inflated the balloon rests against the bladder outlet to anchor the catheter in place. The indwelling retention catheter often has two or three lumens within the body of the catheter (see Fig. 45-12, B). One lumen drains urine through the catheter to a collecting tube. A second lumen carries sterile water to and from the balloon when it is inflated or deflated. A third (optional) lumen is sometimes used to instill fluids or medications into the bladder. It is easy to determine the number of lumens by the number of drainage and injection ports at the end of the catheter.