Nutrition

• Explain the importance of a balance between energy intake and energy requirements.

• List the end products of carbohydrate, protein, and fat metabolism.

• Explain the significance of saturated, unsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats.

• Describe the food guide pyramid and discuss its value in planning meals for good nutrition.

• List the current dietary guidelines for the general population.

• Explain the variance in nutritional requirements throughout growth and development.

• Discuss the major methods of nutritional assessment.

• Identify three major nutritional problems and describe patients at risk.

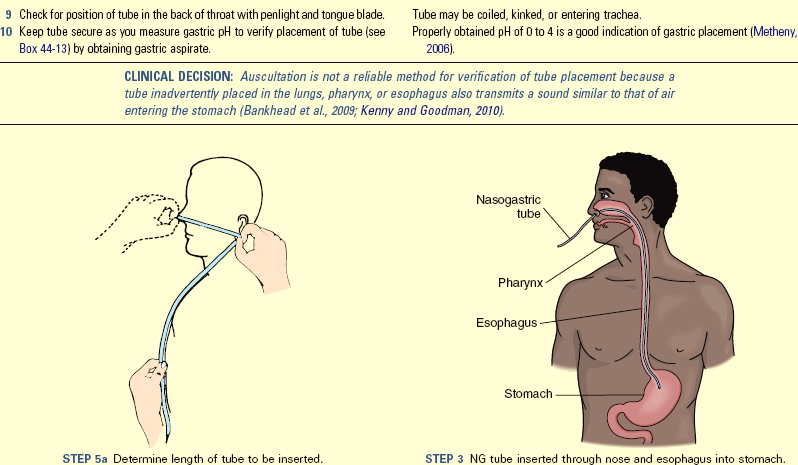

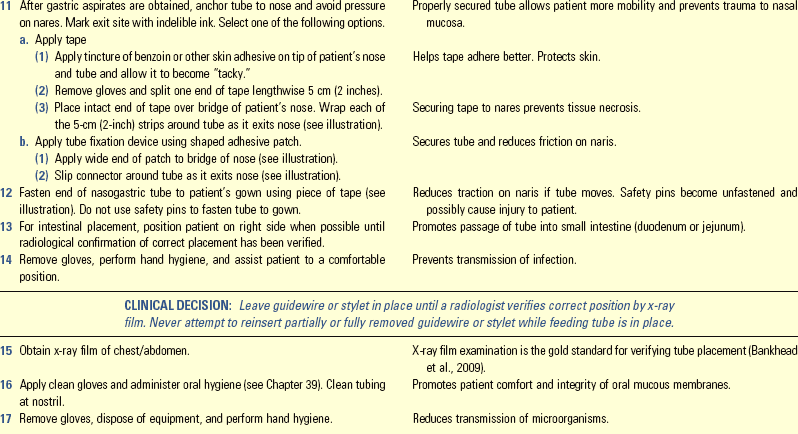

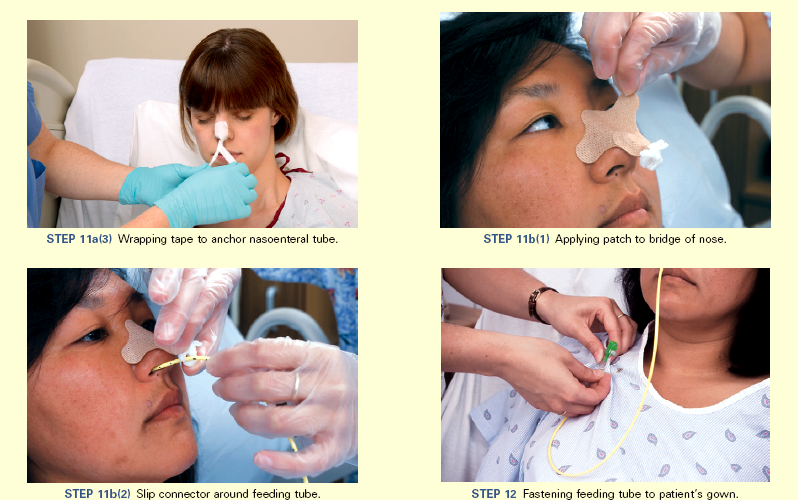

• Establish a plan of care to meet the nutritional needs of a patient.

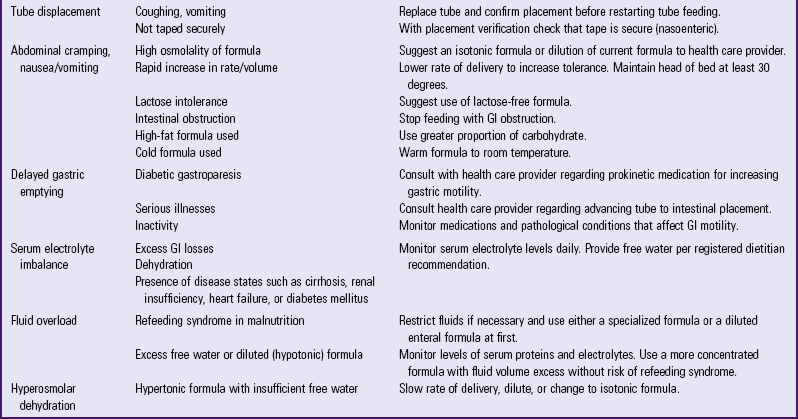

• Describe the procedure for initiating and maintaining enteral feedings.

• Describe the methods to avoid complications of enteral feedings.

• Describe the methods for avoiding complications of parenteral nutrition.

• Discuss medical nutrition therapy in relation to three medical conditions.

• Discuss diet counseling and patient teaching in relation to patient expectations.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Nutrition is a basic component of health and is essential for normal growth and development, tissue maintenance and repair, cellular metabolism, and organ function. The human body needs an adequate supply of nutrients for essential functions of cells. Food security is critical for all members of a household. This means that all household members have access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to maintain a healthy lifestyle; sufficient food is available on a consistent basis; and the household has resources to obtain appropriate food for a nutritious diet. Food also holds symbolic meaning. Giving or taking food is part of ceremonies, social gatherings, holiday traditions, religious events, the celebration of birth, and the mourning of death. The difficulty of the decision to withdraw food in a terminal illness, even in the form of intravenous (IV) nutrients, is a testament to the symbolic power of food and feeding.

Florence Nightingale understood the importance of nutrition, stressing a nurse’s role in the science and art of feeding during the mid-1800s (Dossey, 1999). Since then the nurse’s role in nutrition and diet therapy has changed. Medical nutrition therapy (MNT) uses nutrition therapy and counseling to manage diseases (American Dietetic Association, 2010b). In some illnesses such as type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM) or mild hypertension, diet therapy is often the major treatment for disease control (ADA, 2008; American Heart Association, 2010). Other conditions such as severe inflammatory bowel disease require specialized nutrition support such as enteral nutrition (EN) or parenteral nutrition (PN). Current standards of care promote optimal nutrition in all patients (American Heart Association, 2010; ACS, 2011).

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) and the Public Health Service established nutritional goals and objectives for Healthy People 2020 (USDHHS, 2010). Healthy People 2020 is the United States’ contribution to the “Health for All” strategy of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2010). Healthy People 2020 (Box 44-1) continues the objectives initiated in Healthy People 2000 and Healthy People 2010, with overall goals of promoting health and reducing chronic disease. All nutrition-related objectives include baseline data from which progress is measured. The challenge remains to motivate consumers to put these dietary recommendations into practice.

Scientific Knowledge Base

Nutrients: The Biochemical Units of Nutrition

The body requires fuel to provide energy for cellular metabolism and repair, organ function, growth, and body movement. The basal metabolic rate (BMR) is the energy needed to maintain life-sustaining activities (breathing, circulation, heart rate, and temperature) for a specific period of time at rest. Factors such as age, body mass, gender, fever, starvation, menstruation, illness, injury, infection, activity level, or thyroid function affect energy requirements. The resting energy expenditure (REE), or resting metabolic rate, is the amount of energy that an individual needs to consume over a 24-hour period for the body to maintain all of its internal working activities while at rest. Factors that affect metabolism include illness, pregnancy, lactation, and activity level.

In general, when energy requirements are completely met by kilocalorie (kcal) intake in food, weight does not change. When the kilocalories ingested exceed a person’s energy demands, the individual gains weight. If the kilocalories ingested fail to meet a person’s energy requirements, the individual loses weight.

Nutrients are the elements necessary for the normal function of numerous body processes. Energy needs are met from a variety of nutrients: carbohydrates, proteins, fats, water, vitamins, and minerals. Food is sometimes described according to its nutrient density (i.e., the proportion of essential nutrients to the number of kilocalories). High–nutrient dense foods such as fruits and vegetables provide a large number of nutrients in relationship to kilocalories. Low–nutrient dense foods such as alcohol or sugar are high in kilocalories but nutrient poor.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates, composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, are the main source of energy in the diet. Each gram of carbohydrate produces 4 kcal/g and serves as the main source of fuel (glucose) for the brain, skeletal muscles during exercise, erythrocyte and leukocyte production, and cell function of the renal medulla. People obtain carbohydrates primarily from plant foods, except for lactose (milk sugar). They are classified according to their carbohydrate units, or saccharides.

Monosaccharides such as glucose (dextrose) or fructose cannot be broken down into a more basic carbohydrate unit. Disaccharides such as sucrose, lactose, and maltose are composed of two monosaccharides and water. Both monosaccharides and disaccharides are classified as simple carbohydrates and are found primarily in sugars. Polysaccharides such as glycogen are made up of many carbohydrate units (i.e., complex carbohydrates). They are insoluble in water and digested to varying degrees. Starches are polysaccharides.

The body is unable to digest some polysaccharides because humans do not have enzymes capable of breaking them down. Fiber is a polysaccharide that is the structural part of plants that is not broken down by the human digestive enzymes. Because fiber is not broken down, it does not contribute calories to the diet. Insoluble fibers are not digestible and include cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Soluble fibers dissolve in water and include barley, cereal grains, cornmeal, and oats.

Proteins

Proteins provide a source of energy (4 kcal/g), and they are essential for synthesis (building) of body tissue in growth, maintenance, and repair. Collagen, hormones, enzymes, immune cells, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), and ribonucleic acid (RNA) are all made of protein. In addition, blood clotting, fluid regulation, and acid-base balance require proteins. These proteins transport nutrients and many drugs in the blood. Ingestion of proteins maintains nitrogen balance.

The simplest form of protein is the amino acid, which is made up of hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, and nitrogen. The body does not synthesize indispensable amino acids; thus these need to be provided in the diet. Examples of indispensable amino acids are histidine, lysine, and phenylalanine. The body synthesizes dispensable amino acids. Examples of amino acids synthesized in the body are alanine, asparagine, and glutamic acid. Amino acids can link together. Albumin and insulin are simple proteins because they contain only amino acids or their derivatives. The combination of a simple protein with a nonprotein substance produces a complex protein such as lipoprotein, formed by a combination of a lipid and a simple protein.

A complete protein, also called a high-quality protein, contains all essential amino acids in sufficient quantity to support growth and maintain nitrogen balance. Examples of foods that contain complete proteins are fish, chicken, soybeans, turkey, and cheese. Incomplete proteins are missing one or more of the nine indispensable amino acids and include cereals, legumes (beans, peas), and vegetables. Complementary proteins are pairs of incomplete proteins that, when combined, supply the total amount of protein provided by complete protein sources.

Nitrogen balance is achieved when the intake and output of nitrogen are equal. When the intake of nitrogen is greater than the output, the body is in positive nitrogen balance. Positive nitrogen balance is required for growth, normal pregnancy, maintenance of lean muscle mass and vital organs, and wound healing. The body uses nitrogen to build, repair, and replace body tissues. Negative nitrogen balance occurs when the body loses more nitrogen than it gains (e.g., with infection, burns, fever, starvation, head injury, and trauma). The increased nitrogen loss is the result of body tissue destruction or loss of nitrogen-containing body fluids. Nutrition during this period needs to provide nutrients to put patients into positive balance for healing.

Protein provides energy; however, because of the essential role of protein in growth, maintenance, and repair, a diet needs to provide adequate kilocalories from nonprotein sources. When there is sufficient carbohydrate in the diet to meet the energy needs of the body, protein is spared as an energy source.

Fats

Fats (lipids) are the most calorie-dense nutrient, providing 9 kcal/g. Fats are composed of triglycerides and fatty acids. Triglycerides circulate in the blood and are composed of three fatty acids attached to a glycerol. Fatty acids are composed of chains of carbon and hydrogen atoms with an acid group on one end of the chain and a methyl group at the other. Fatty acids can be saturated, in which each carbon in the chain has two attached hydrogen atoms; or unsaturated, in which an unequal number of hydrogen atoms are attached and the carbon atoms attach to each other with a double bond. Monounsaturated fatty acids have one double bond, whereas polyunsaturated fatty acids have two or more double carbon bonds. The various types of fatty acids have significance for health and the incidence of disease and are referred to in dietary guidelines.

Fatty acids are also classified as essential or nonessential. Linoleic acid, an unsaturated fatty acid, is the only essential fatty acid in humans. Linolenic acid and arachidonic acid (also unsaturated fatty acids) are important for metabolic processes but are manufactured by the body when linoleic acid is available. Deficiency occurs when fat intake falls below 10% of daily nutrition. Most animal fats have high proportions of saturated fatty acids, whereas vegetable fats have higher amounts of unsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Water

Water is critical because cell function depends on a fluid environment. Water makes up 60% to 70% of total body weight. The percent of total body water is greater for lean people than obese people because muscle contains more water than any other tissue except blood. Infants have the greatest percentage of total body water, and older people have the least. When deprived of water, a person cannot survive for more than a few days.

An individual meets fluid needs by drinking liquids and eating solid foods high in water content such as fresh fruits and vegetables. Water is also produced during digestion when food is oxidized. In a healthy individual fluid intake from all sources equals fluid output through elimination, respiration, and sweating (see Chapters 41 and 45). An ill person has an increased need for fluid (e.g., with fever or gastrointestinal [GI] losses). By contrast, he or she also has a decreased ability to excrete fluid (e.g., with cardiopulmonary or renal disease), which often leads to the need for fluid restriction.

Vitamins

Vitamins are organic substances present in small amounts in foods that are essential to normal metabolism. They are chemicals that act as catalysts in biochemical reactions. When there is enough of any specific vitamin to meet the body’s catalytic demands, the rest of the vitamin supply acts as a free chemical and is often toxic to the body. Certain vitamins are currently of interest in their role as antioxidants. These vitamins neutralize substances called free radicals, which produce oxidative damage to body cells and tissues. Researchers think that oxidative damage increases a person’s risk for various cancers. These vitamins include betacarotene and vitamins A, C, and E (Nix, 2009).

The body is unable to synthesize vitamins in the required amounts and depends on dietary intake. Vitamin content is usually highest in fresh foods that are used quickly after minimal exposure to heat, air, or water. Vitamins are classified as fat soluble and water soluble.

Fat-Soluble Vitamins: The fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) are stored in the fatty compartments of the body. With the exception of vitamin D, people acquire vitamins through dietary intake. Hypervitaminosis of fat-soluble vitamins results from megadoses (intentional or unintentional) of supplemental vitamins, excessive amounts in fortified food, and large intake of fish oils.

Water-Soluble Vitamins: The water-soluble vitamins are vitamin C and the B complex (which is eight vitamins). The body does not store water-soluble vitamins; thus they need to be provided in daily food intake. Water-soluble vitamins absorb easily from the GI tract. Although they are not stored, toxicity can still occur.

Minerals

Minerals are inorganic elements essential to the body as catalysts in biochemical reactions. They are classified as macrominerals when the daily requirement is 100 mg or more and microminerals or trace elements when less than 100 mg is needed daily. Macrominerals help to balance the pH of the body, and specific amounts are necessary in the blood and cells to promote acid-base balance. Interactions occur among trace minerals. For example, excess of one trace mineral sometimes causes deficiency of another. Selenium is a trace element that also has antioxidant properties. Silicon, vanadium, nickel, tin, cadmium, arsenic, aluminum, and boron play an unidentified role in nutrition. Arsenic, aluminum, and cadmium have toxic effects.

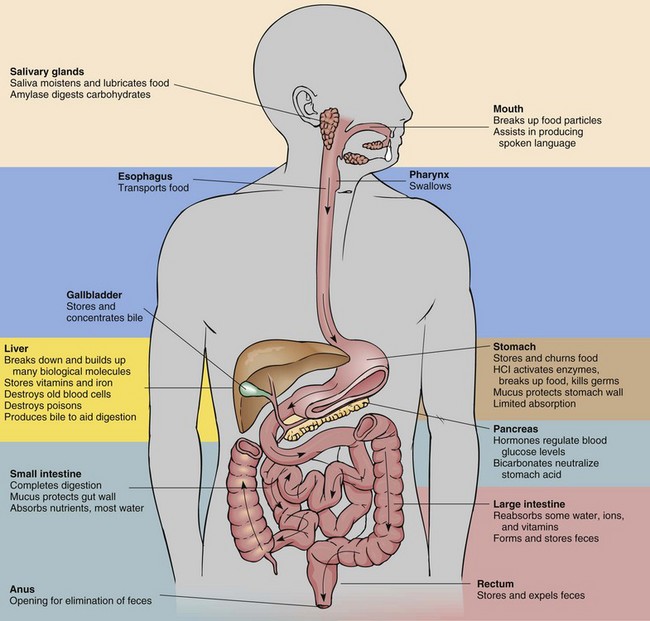

Anatomy and Physiology of the Digestive System

Digestion of food is the mechanical breakdown that results from chewing, churning, and mixing with fluid and chemical reactions in which food is reduced to its simplest form. Each part of the GI system has an important digestive or absorptive function (Fig. 44-1). Enzymes are the proteinlike substances that act as catalysts to speed up chemical reactions. They are an essential part of the chemistry of digestion.

FIG. 44-1 Summary of digestive system anatomy/organ function. HCl, Hydrochloric acid. (From Rolin Graphics.)

Most enzymes have one specific function. Each enzyme works best at a specific pH. For example, the enzyme amylase in the saliva breaks down starches into sugars. The secretions of the GI tract have very different pH levels. For example, saliva is relatively neutral, gastric juice is highly acidic, and the secretions of the small intestine are alkaline.

The mechanical, chemical, and hormonal activities of digestion are interdependent. Enzyme activity depends on the mechanical breakdown of food to increase its surface area for chemical action. Hormones regulate the flow of digestive secretions needed for enzyme supply. Physical, chemical, and hormonal factors regulate the secretion of digestive juices and the motility of the GI tract. Nerve stimulation from the parasympathetic nervous system (e.g., the vagus nerve) increases GI tract action.

Digestion begins in the mouth, where chewing mechanically breaks down food. The food mixes with saliva, which contains ptyalin (salivary amylase), an enzyme that acts on cooked starch to begin its conversion to maltose. The longer an individual chews food, the more starch digestion occurs in the mouth. Proteins and fats are broken down physically but remain unchanged chemically because enzymes in the mouth do not react with these nutrients. Chewing reduces food particles to a size suitable for swallowing, and saliva provides lubrication to further ease swallowing of the food. The epiglottis is a flap of skin that closes over the trachea as a person swallows to prevent aspiration. Swallowed food enters the esophagus, and wavelike muscular contractions (peristalsis) move the food to the base of the esophagus, above the cardiac sphincter. Pressure from a bolus of food at the cardiac sphincter causes it to relax, allowing the food to enter the fundus, or uppermost portion, of the stomach.

The chief cells in the stomach secrete pepsinogen; and the pyloric glands secrete gastrin, a hormone that triggers parietal cells to secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl). The parietal cells also secrete HCl and intrinsic factor (IF), which is necessary for absorption of vitamin B12 in the ileum. HCl turns pepsinogen into pepsin, a protein-splitting enzyme. The body produces gastric lipase and amylase to begin fat and starch digestion, respectively. A thick layer of mucus protects the lining of the stomach from autodigestion. Alcohol and aspirin are two substances directly absorbed through the lining of the stomach. The stomach acts as a reservoir where food remains for approximately 3 hours, with a range of 1 to 7 hours.

Food leaves the antrum, or distal stomach, through the pyloric sphincter and enters the duodenum. Food is now an acidic, liquefied mass called chyme. Chyme flows into the duodenum and quickly mixes with bile, intestinal juices, and pancreatic secretions. The small intestine secretes the hormones secretin and cholecystokinin (CCK). Secretin activates release of bicarbonate from the pancreas, raising the pH of chyme. CCK inhibits further gastrin secretion and initiates release of additional digestive enzymes from the pancreas and gallbladder.

Bile is manufactured in the liver and concentrated and stored in the gallbladder. It acts as a detergent because it emulsifies fat to permit enzyme action while suspending fatty acids in solution. Pancreatic secretions contain six enzymes: amylase to digest starch; lipase to break down emulsified fats; and trypsin, elastase, chymotrypsin, and carboxypeptidase to break down proteins.

Peristalsis continues in the small intestine, mixing the secretions with chyme. The mixture becomes increasingly alkaline, inhibiting the action of the gastric enzymes and promoting the action of the duodenal secretions. Epithelial cells in the small intestinal villi secrete enzymes (e.g., sucrase, lactase, maltase, lipase, and peptidase) to facilitate digestion. The major portion of digestion occurs in the small intestine, producing glucose, fructose, and galactose from carbohydrates; amino acids and dipeptides from proteins; and fatty acids, glycerides, and glycerol from lipids. Peristalsis usually takes approximately 5 hours to pass food through the small intestine.

Absorption

The small intestine is the primary absorption site for nutrients. It is lined with fingerlike projections called villi. Villi increase the surface area available for absorption. The body absorbs nutrients by means of passive diffusion, osmosis, active transport, and pinocytosis (Table 44-1).

TABLE 44-1

Mechanisms for Intestinal Absorption of Nutrients

| MECHANISM | DEFINITION |

| Active transport | An energy-dependent process whereby particles move from an area of greater concentration to an area of lesser concentration. A special “carrier” moves the particle across the cell membrane. |

| Passive diffusion | The force by which particles move outward from an area of greater concentration to lesser concentration. The particles do not need a special “carrier” to move outward in all directions. |

| Osmosis | Movement of water through a membrane that separates solutions of different concentrations. Water moves to equalize the concentration pressures on both sides of the membrane. |

| Pinocytosis | Engulfing of large molecules of nutrients by the absorbing cell when the molecule attaches to the absorbing cell membrane. |

Data from Nix S: Williams’ basic nutrition and diet therapy, ed 13, St Louis, 2009, Mosby.

Carbohydrates, protein, minerals, and water-soluble vitamins are absorbed by the small intestine, processed in the liver, and released into the portal vein circulation. Fatty acids are absorbed in the lymphatic circulatory systems through lacteal ducts at the center of each microvilli in the small intestine.

Approximately 85% to 90% of water is absorbed in the small intestine (Huether et al., 2008). Approximately 8.5 L of GI secretions and 1.5 L of oral intake are managed daily within the GI tract. The small intestine resorbs 9.5 L, and the colon absorbs approximately 0.4 L. The remaining 0.1 L is eliminated in feces. In addition, electrolytes and minerals are absorbed in the colon, and bacteria synthesize vitamin K and some B-complex vitamins. Finally, feces are formed for elimination.

Metabolism and Storage of Nutrients

Metabolism refers to all of the biochemical reactions within the cells of the body. Metabolic processes are anabolic (building) or catabolic (breaking down). Anabolism is the building of more complex biochemical substances by synthesis of nutrients. Anabolism occurs when an individual adds lean muscle through diet and exercise. Amino acids are anabolized into tissues, hormones, and enzymes. Normal metabolism and anabolism are physiologically possible when the body is in positive nitrogen balance. Catabolism is the breakdown of biochemical substances into simpler substances and occurs during physiological states of negative nitrogen balance. Starvation is an example of catabolism when wasting of body tissues occurs.

Nutrients absorbed in the intestines, including water, are transported through the circulatory system to the body tissues. Through the chemical changes of metabolism, the body converts nutrients into a number of required substances. Carbohydrates, protein, and fat are metabolized to produce chemical energy and maintain a balance between anabolism and catabolism. To carry out the work of the body, the chemical energy produced by metabolism converts to other types of energy by different tissues. Muscle contraction involves mechanical energy, nervous system function involves electrical energy, and the mechanisms of heat production involve thermal energy.

Some of the nutrients required by the body are stored in tissues. The major form of body reserve energy is fat, stored as adipose tissue. Protein is stored in muscle mass. When the energy requirements of the body exceed the energy supplied by ingested nutrients, stored energy is used. Monoglycerides from the digested portion of fats are converted to glucose by gluconeogenesis. Amino acids are also converted to fat and stored or catabolized into energy through gluconeogenesis. All body cells except red blood cells and neurons oxidize fatty acids into ketones for energy when dietary carbohydrates (glucose) are not adequate. Glycogen, synthesized from glucose, provides energy during brief periods of fasting (e.g., during sleep). It is stored in small reserves in liver and muscle tissue. Nutrient metabolism consists of three main processes:

Elimination

Chyme moves by peristaltic action through the ileocecal valve into the large intestine, where it becomes feces (see Chapter 46). Water absorbs in the mucosa as feces move toward the rectum. The longer the material stays in the large intestine, the more water is absorbed, causing the feces to become firmer. Exercise and fiber stimulate peristalsis, and water maintains consistency. Feces contain cellulose and similar indigestible substances, sloughed epithelial cells from the GI tract, digestive secretions, water, and microbes.

Dietary Guidelines

Dietary reference intakes (DRIs) present evidence-based criteria for an acceptable range of amounts of vitamins and nutrients for each gender and age-group (Institute of Medicine, 2006). There are four components to the DRIs. The estimated average requirement (EAR) is the recommended amount of a nutrient that appears sufficient to maintain a specific body function for 50% of the population based on age and gender. The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) is the average needs of 98% of the population, not the exact needs of the individual. The adequate intake (AI) is the suggested intake for individuals based on observed or experimentally determined estimates of nutrient intakes and is used when there is not enough evidence to set the RDA. The tolerable upper intake level (UL) is the highest level that likely poses no risk of adverse health events. It is not a recommended level of intake (Tolerable upper level intake, 2010).

Food Guidelines

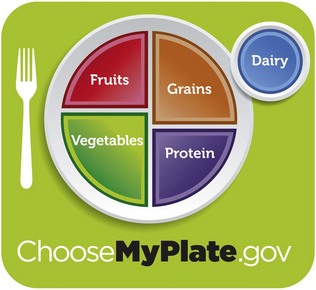

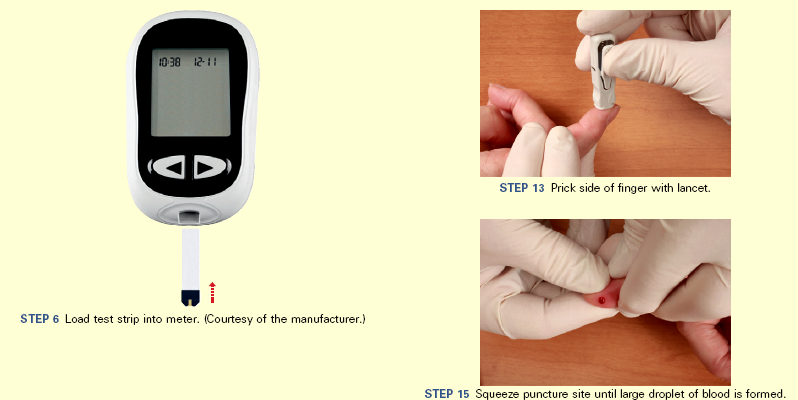

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) published the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010 and provide average daily consumption guidelines for the five food groups: grains, vegetables, fruits, dairy products, and meats (Box 44-2). These guidelines are for Americans over the age of 2 years. As a nurse, consider the food preferences of patients from different racial and ethnic groups, vegetarians, and others when planning diets. The ChooseMyPlate program was developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to replace the My Food Pyramid program. ChooseMyPlate provides a basic guide for making food choices for a healthy lifestyle (Fig. 44-2). The ChooseMyPlate program includes guidelines for balancing calories; decreasing portion size; increasing healthy foods; increasing water consumption; and decreasing fats, sodium, and sugars (USDA, 2011a).

FIG. 44-2 ChooseMyPlate. (From US Department of Agriculture: ChooseMyPlate, 2011, http://www.choosemyplate.gov).

Daily Values

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) created daily values for food labels in response to the 1990 Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA). The FDA first established two sets of reference values. The referenced daily intakes (RDIs) are the first set, comprising protein, vitamins, and minerals based on the RDA. The daily reference values (DRVs) make up the second set and consist of nutrients such as total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, carbohydrates, fiber, sodium, and potassium. Combined, both sets make up the daily values used on food labels (USFDA, 2008). Daily values did not replace RDAs but provided a separate, more understandable format for the public. Daily values are based on percentages of a diet consisting of 2000 kcal/day for adults and children 4 years or older.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Sociological, cultural, psychological, and emotional factors are associated with eating and drinking in all societies. Holidays and events are celebrated with food, food is brought to those who are grieving, and food is used for medicinal purposes. It is incorporated into family traditions and rituals and is often associated with eating behaviors. You need to understand patients’ values, beliefs, and attitudes about food and how these values affect food purchase, preparation, and intake to affect eating patterns.

Nutritional requirements depend on many factors. Individual caloric and nutrient requirements vary by stage of development, body composition, activity levels, pregnancy and lactation, and the presence of disease. Registered dietitians (RDs) use predictive equations that take into account some of these factors to estimate patients’ nutritional requirements.

Factors Influencing Nutrition

Environmental factors beyond the control of individuals contribute to the development of obesity. Obesity is an epidemic in the United States. The prevalence of obesity in adults has doubled since 1980, with 33% of adults in the United States overweight, 34% obese, and 6 % extremely obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥40) (Khan et al., 2009). Proposed contributing factors are sedentary lifestyle, work schedules, and poor meal choices often related to the increasing frequency of eating away from home and eating fast food (Kruskall, 2006). The likelihood of healthy eating and participation in exercise or other activities of healthy living is limited by environmental factors. Lack of access to full-service grocery stores, high cost of healthy food, widespread availability of less healthy foods in fast-food restaurants, widespread advertising of less healthy food, and lack of access to safe places to play and exercise are environmental factors that contribute to obesity (Khan et al., 2009).

Developmental Needs

Infants Through School-Age: Rapid growth and high protein, vitamin, mineral, and energy requirements mark the developmental stage of infancy. The average birth weight of an American baby is 3.2 to 3.4 kg (7 to  pounds). An infant usually doubles birth weight at 4 to 5 months and triples it at 1 year. Infants need an energy intake of approximately 90 to 110 kcal/kg of body weight, with premature infants needing 105 to 130 kcal/kg per day (Nix, 2009). Commercial formulas and human breast milk both provide approximately 20 kcal/oz. A full-term newborn is able to digest and absorb simple carbohydrates, proteins, and a moderate amount of emulsified fat. Infants need about 100 to 120 mL/kg/day of fluid because a large portion of total body weight is water.

pounds). An infant usually doubles birth weight at 4 to 5 months and triples it at 1 year. Infants need an energy intake of approximately 90 to 110 kcal/kg of body weight, with premature infants needing 105 to 130 kcal/kg per day (Nix, 2009). Commercial formulas and human breast milk both provide approximately 20 kcal/oz. A full-term newborn is able to digest and absorb simple carbohydrates, proteins, and a moderate amount of emulsified fat. Infants need about 100 to 120 mL/kg/day of fluid because a large portion of total body weight is water.

Breastfeeding: The American Dietetic Association strongly supports exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life and breastfeeding with complementary foods from 6 to 12 months (American Dietetic Association, 2009). Breastfeeding has multiple benefits for both infant and mother, including fewer food allergies and intolerances; fewer infant infections; easier digestion; convenience, availability, and freshness; temperature always correct; economical because it is less expensive than formula; and increased time for mother and infant interaction.

Formula: Infant formulas contain the approximate nutrient composition of human milk. Protein in the formula is typically whey, soy, cow’s milk base, casein hydrolysate, or elemental amino acids. The American Academy of Pediatrics sets standards for the level of nutrients in infant formulas. Soy protein–based formulas are used for infants allergic or intolerant to cow’s milk (Nix, 2009).

Infants should not have regular cow’s milk during the first year of life. It is too concentrated for an infant’s kidneys to manage, increases the risk of milk product allergies, and is a poor source of iron and vitamins C and E (Nix, 2009). Honey and corn syrup are potential sources of botulism toxin and should not be used in an infant’s diet. This toxin is potentially fatal in children under 1 year of age (Nix, 2009).

Introduction to Solid Food: Breast milk or formula provides sufficient nutrition for the first 4 to 6 months of life. The development of fine-motor skills of the hand and fingers parallels an infant’s interest in food and self-feeding. Iron-fortified cereals are typically the first semisolid food to be introduced. For infants 4 to 11 months, cereals are the most important nonmilk source of protein (Fox et al., 2006).

The addition of foods to an infant’s diet is governed by an infant’s nutrient needs, physical readiness to handle different forms of foods, and the need to detect and control allergic reactions. Foods such as wheat, egg white, nuts, citrus juice, and chocolate have a high incidence of allergies and should be added late (Nix, 2009). Caregivers should introduce new foods one at a time, approximately 4 to 7 days apart to identify allergies. It is best to introduce new foods before milk or other foods to avoid satiety (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

The growth rate slows during toddler years (1 to 3 years). A toddler needs fewer kilocalories but an increased amount of protein in relation to body weight; consequently appetite often decreases at 18 months of age. Toddlers exhibit strong food preferences and become picky eaters. Small frequent meals consisting of breakfast, lunch, and dinner with three interspersed high nutrient–dense snacks help improve nutritional intake (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Calcium and phosphorus are important for healthy bone growth.

Toddlers who consume more than 24 ounces of milk daily in place of other foods sometimes develop milk anemia because milk is a poor source of iron. Toddlers need to drink whole milk until the age of 2 years to make sure that there is adequate intake of fatty acids necessary for brain and neurological development. Certain foods such as hot dogs, candy, nuts, grapes, raw vegetables, and popcorn have been implicated in choking deaths and need to be avoided. Dietary requirements for preschoolers (3 to 5 years) are similar to those for toddlers. They consume slightly more than toddlers, and nutrient density is more important than quantity.

School-age children, 6 to 12 years old, grow at a slower and steadier rate, with a gradual decline in energy requirements per unit of body weight. Despite better appetites and more varied food intake, you need to assess school-age children’s diets carefully for adequate protein and vitamins A and C. They often fail to eat a proper breakfast and have unsupervised intake at school. High fat, sugar, and salt result from too-liberal intake of snack foods. Physical activity level decreases consistently, and high-calorie, readily available food increases in consumption, leading to an increase in childhood obesity (Budd and Hayman, 2008).

In the last 20 years the prevalence of overweight children has risen. The percent of obesity in children ages 6 to 11 years has doubled to 17%, and the percent of overweight adolescents has more than tripled to 17.6% (Li and Hooker, 2010). A combination of factors contributes to the problem, including a diet rich in high-calorie foods, food advertising targeting children, inactivity, genetic predisposition, use of food as a coping mechanism for stress or boredom or as a reward or celebration, and family and social factors (Budd and Hayman, 2008). Childhood obesity contributes to medical problems related to the cardiovascular system, endocrine system, and mental health (Budd and Hayman, 2008). As a result of the obesity, the incidence of type II diabetes in children is also increasing. Prevention of childhood obesity is critical because of the long-term effects. Family education is an important component in decreasing the prevalence of this problem. Promote healthy food choices and eating in moderation along with increased physical activity.

Adolescents: During adolescence physiological age is a better guide to nutritional needs than chronological age. Energy needs increase to meet greater metabolic demands of growth. Daily requirement of protein also increases. Calcium is essential for the rapid bone growth of adolescence, and girls need a continuous source of iron to replace menstrual losses. Boys also need adequate iron for muscle development. Iodine supports increased thyroid activity, and use of iodized table salt ensures availability. B-complex vitamins are necessary to support heightened metabolic activity.

Many factors other than nutritional needs influence the adolescent’s diet, including concern about body image and appearance, desire for independence, eating at fast-food restaurants, peer pressure, and fad diets. Nutritional deficiencies often occur in adolescent girls as a result of dieting and use of oral contraceptives. An adolescent boy’s diet is often inadequate in total kilocalories, protein, iron, folic acid, B vitamins, and iodine. Snacks provide approximately 25% of a teenager’s total dietary intake. Fast food, particularly value-size or super-size meals, is common and adds extra salt, fat, and kilocalories (Budd and Hayman, 2008). Skipping meals or eating meals with unhealthy choices of snacks contributes to nutrient deficiency and obesity (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Fortified foods (nutrients added) are important sources of vitamins and minerals. Snack food from the dairy and fruit and vegetable groups are good choices. To counter obesity, increasing physical activity is often more important than curbing intake. The onset of eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa often occurs during adolescence. Recognition of eating disorders is essential for early intervention (Box 44-3).

Sports and regular moderate-to-intense exercise necessitate dietary modification to meet increased energy needs for adolescents. Carbohydrates, both simple and complex, are the main source of energy, providing 55% to 60% of total daily kilocalories. Protein needs increase to 1 to 1.5 g/kg/day. Fat needs do not increase. Adequate hydration is very important. Adolescents need to ingest water before and after exercise to prevent dehydration, especially in hot, humid environments. Vitamin and mineral supplements are not required, but intake of iron-rich foods is required to prevent anemia.

Parents have more influence on adolescents’ diets than they believe. Effective strategies include limiting the amount of unhealthy food choices kept at home, encouraging smart snacks such as fruit vegetables or string cheese, and enhancing the appearance and taste of healthy foods (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2009). Making healthy food choices more convenient at home and at fast-food restaurants and discouraging adolescents from eating while watching television are ways to promote healthy eating (Befort et al., 2006).

Pregnancy occurring within 4 years of menarche places a mother and fetus at risk because of anatomical and physiological immaturity. Malnutrition at the time of conception increases risk to the adolescent and her fetus. Most teenage girls do not want to gain weight. Counseling related to nutritional needs of pregnancy is often difficult, and teens tolerate suggestions better than rigid directions. The diet of pregnant adolescents is often deficient in calcium, iron, and vitamins A and C. Prenatal vitamin and mineral supplements are recommended.

Young and Middle Adults: There is a reduction in nutrient demands as the growth period ends. Mature adults need nutrients for energy, maintenance, and repair. Energy needs usually decline over the years. Obesity becomes a problem because of decreased physical exercise, dining out more often, and increased ability to afford more luxury foods. Adult women who use oral contraceptives often need extra vitamins. Iron and calcium intake continues to be important.

Pregnancy: Poor nutrition during pregnancy causes low birth weight in infants and decreases chances of survival. Generally the needs of a fetus are met at the expense of the mother. However, if nutrient sources are not available, both suffer. The nutritional status of the mother at the time of conception is important. Significant aspects of fetal growth and development often occur before the mother suspects the pregnancy. The energy requirements of pregnancy are related to the mother’s body weight and activity. The quality of nutrition during pregnancy is important, and food intake in the first trimester includes balanced portions of essential nutrients with emphasis on quality. Protein intake throughout pregnancy needs to increase to 60 g daily. Calcium intake is especially critical in the third trimester, when fetal bones are mineralized. Iron needs to be supplemented to provide for increased maternal blood volume, fetal blood storage, and blood loss during delivery.

Folic acid intake is particularly important for deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis and the growth of red blood cells. Inadequate intake can lead to fetal neural tube defects, anencephaly, or maternal megaloblastic anemia (Nix, 2009). Women of childbearing age need to consume 400 mcg of folic acid daily, increasing to 600 mcg daily during pregnancy. Prenatal care usually includes vitamin and mineral supplementation to ensure daily intakes; however, pregnant women should not take additional supplements beyond prescribed amounts.

Lactation: The lactating woman needs 500 kcal/day above the usual allowance because the production of milk increases energy requirements. Protein requirements during lactation are greater than those required during pregnancy. The need for calcium remains the same as during pregnancy. There is an increased need for vitamins A and C. Daily intake of water-soluble vitamins (B and C) is necessary to ensure adequate levels in breast milk. Fluid intake needs to be adequate but not excessive. Caffeine, alcohol, and drugs are excreted in breast milk and should be avoided.

Older Adults: Adults 65 years and older have a decreased need for energy because their metabolic rate slows with age. However, vitamin and mineral requirements remain unchanged from middle adulthood. Numerous factors influence the nutritional status of the older adult (Box 44-4). Age-related changes in appetite, taste, smell, and the digestive system affect nutrition (Touhy and Jett, 2010). For example, older adults often experience a decrease in taste cells that alters food flavor and may decrease intake. Multiple factors contribute to the risk of food insecurity in the older adult. Income is significant because living on a fixed income often reduces the amount of money available to buy food. Health is another important influence that affects a person’s desire and ability to eat. Lack of transportation or ability to get to the grocery store because of mobility problems contributes to inability to purchase adequate and nutritious food. Often availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods is limited or uncertain.

Maintaining good oral health is significant throughout adulthood, particularly as an individual ages. Difficulty chewing, missing teeth, having teeth in poor condition, and oral pain result from poor oral health. These often contribute to malnutrition and dehydration in older adults (Touhy and Jett, 2010). Poor oral hygiene and periodontal disease are potential risk factors for systemic diseases such as joint infections, ischemic stroke, cardiovascular disease, DM, and aspiration pneumonia (O’Connor, 2008).

The older adult is often on a therapeutic diet or has difficulty eating because of physical symptoms, lack of teeth, or dentures or is at risk for drug-nutrient interactions (Table 44-2). Caution older adults to avoid grapefruit and grapefruit juice because they alter absorption of many drugs. Thirst sensation diminishes, leading to inadequate fluid intake or dehydration (see Chapter 41). Symptoms of dehydration in older adults include confusion; weakness; hot, dry skin; furrowed tongue; rapid pulse; and high urinary sodium. Some older adults avoid meats because of cost or because they are difficult to chew. Cream soups and meat-based vegetable soups are nutrient-dense sources of protein. Cheese, eggs, and peanut butter are also useful high-protein alternatives. Milk continues to be an important food for older women and men who need adequate calcium to protect against osteoporosis (a decrease of bone mass density). Screening and treatment are necessary for both older men and women. Vitamin D supplements are important for improving strength and balance, strengthening bone health, and preventing bone fractures and falls (Park et al., 2008). The diet of older adults needs to contain choices from all food groups and often requires a vitamin and mineral supplement. MyPlate for Older Adults addresses the specific nutritional needs for older adults and encourages physical activity (Tufts University, 2011).

TABLE 44-2

Sample of Drug-Nutrient Interactions*

| DRUG | EFFECT |

| Analgesic | |

| Acetaminophen | Decreased drug absorption with food; overdose associated with liver failure |

| Aspirin | Absorbed directly through stomach; decreased drug absorption with food; decreased folic acid, vitamins C and K, and iron absorption |

| Antacid | |

| Aluminum hydroxide | Decreased phosphate absorption |

| Sodium bicarbonate | Decreased folic acid absorption |

| Antiarrhythmic | |

| Amiodarone (Codarone) | Taste alteration |

| Digitalis | Anorexia, decreased renal clearance in older people |

| Antibiotic | |

| Penicillin | Decreased drug absorption with food, taste alteration |

| Cephalosporin | Decreased vitamin K |

| Rifampin (Rifadin) | Decreased vitamin B6, niacin, vitamin D |

| Tetracycline | Decreased drug absorption with milk and antacids; decreased nutrient absorption of calcium, riboflavin, vitamin C caused by binding |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Decreased folic acid |

| Anticoagulant | |

| Warfarin (Coumadin) | Acts as antagonist to vitamin K |

| Anticonvulsant | |

| Carbamazepine (Tegretol) | Increased drug absorption with food |

| Phenytoin (Dilantin) | Decreased calcium absorption; decreased vitamins D and K and folic acid; taste alteration; decreased drug absorption with food |

| Antidepressant | |

| Amitriptyline | Appetite stimulant |

| Clomipramine (Anafranil) | Taste alteration, appetite stimulant |

| Fluoxetine (Prozac) (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) | Taste alteration, anorexia |

| Antihypertensive | |

| Captopril (Capoten) | Taste alteration, anorexia |

| Hydralazine | Enhanced drug absorption with food, decreased vitamin B6 |

| Labetalol (Normodyne) | Taste alteration (weight gain for all beta-blockers) |

| Methyldopa | Decreased vitamin B12, folic acid, iron |

| Antiinflammatory | |

| All steroids | Increased appetite and weight, increased folic acid, decreased calcium (osteoporosis with long-term use), promotes gluconeogenesis of protein |

| Antiparkinson | |

| Levodopa (Dopar) | Taste alteration, decreased vitamin B6 and drug absorption with food |

| Antipsychotic | |

| Chlorpromazine | Increased appetite |

| Thiothixene | Decreased riboflavin, increased need |

| Bronchodilator | |

| Albuterol sulfate | Appetite stimulant |

| Theophylline | Anorexia |

| Cholesterol Lowering | |

| Cholestyramine (Prevalite) | Decreased fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K); vitamin B12; iron |

| Diuretic | |

| Furosemide (Lasix) | Decreased drug absorption with food |

| Spironolactone (Aldactone) | Increased drug absorption with food |

| Thiazides | Decreased magnesium, zinc, and potassium |

| Laxative | |

| Mineral oil | Decreased absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), carotene |

| Platelet Aggregate Inhibitor | |

| Dipyridamole (Persantine) | Decreased drug absorption with food |

| Potassium Replacement | |

| Potassium chloride | Decreased vitamin B12 |

| Tranquilizer | |

| Benzodiazepines | Increased appetite |

*Not intended to be an exhaustive or all-inclusive list. Always check pharmacology references before administering medications.

Data from Hermann J: Nutrient and drug interactions, http://pods.dasnr.okstate.edu/docushare/dsweb/Get/Document-2458/T-3120web.pdf; accessed October 31, 2010; Lehne RA: Pharmacology for nursing care, ed 7, St Louis, 2010, Saunders.

The USDHHS Administration on Aging (AOA) requires states to provide nutrition screening services to older adults who benefit from home-delivered or congregate meal services. This program requires meals to provide at least one third of the DRI for an older adult and meet the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (American Dietetic Association, 2010a). Homebound older adults with chronic illnesses have additional nutritional risks. They frequently live alone with little or no social or financial resources to assist in obtaining or preparing nutritionally sound meals, contributing to the risk for food insecurity. Approximately 19% of older adults experience some degree of food insecurity as a result of low income or poverty (American Dietetic Association, 2010a). Increased nutrition screening by the nurse results in early recognition and treatment of nutritional deficiencies. Undernourishment of older adults often results in health problems that lead to admission to acute care hospitals or long-term care facilities.

Alternative Food Patterns

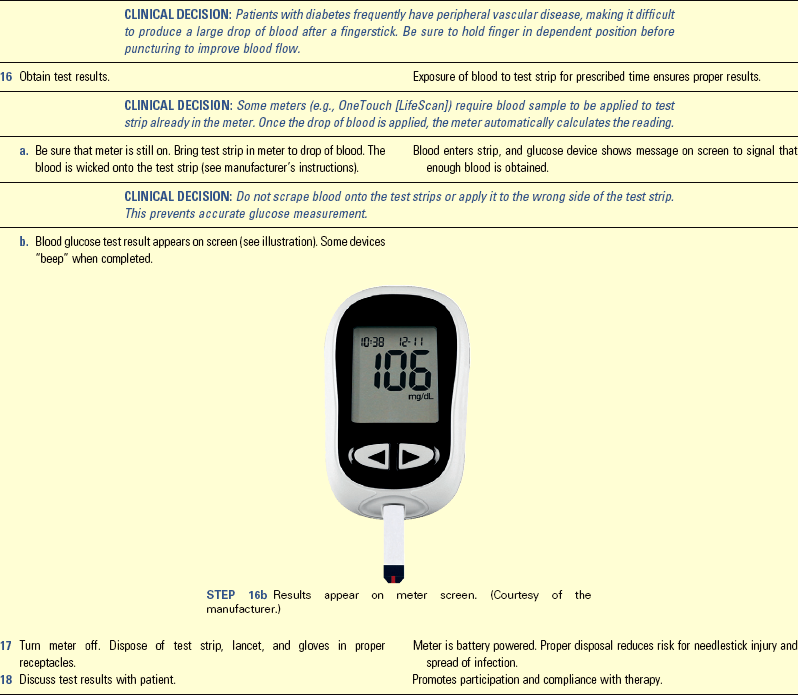

Long before the FDA issued recommended allowances and guidelines, many people followed special patterns of food intake based on religion (Table 44-3), cultural background (Box 44-5), ethics, health beliefs, personal preference, or concern for the efficient use of land to produce food. Such special diets are not necessarily more or less nutritious than diets based on the MyPlate or other nutritional guidelines because good nutrition depends on a balanced intake of all required nutrients.

Vegetarian Diet

A common alternative dietary pattern is the vegetarian diet. Vegetarianism is the consumption of a diet consisting predominantly of plant foods. Some vegetarians are ovolactovegetarian (avoid meat, fish, and poultry but eat eggs and milk), lactovegetarians (drink milk but avoid eggs), or vegans (consume only plant foods). Through careful selection of foods, individuals following a vegetarian diet can meet recommendations for proteins and essential nutrients (Nix, 2009). Zen macrobiotic (primarily brown rice, other grains, and herb teas) and fruitarian (only fruit, nuts, honey, and olive oil) diets are nutrient poor and frequently result in malnutrition. Knowledge related to complementary use of high and low biological value proteins is necessary. Children who follow a vegetarian diet are especially at risk for protein and vitamin deficiencies such as vitamin B12. Careful planning helps to ensure a balanced, healthy diet.

Critical Thinking

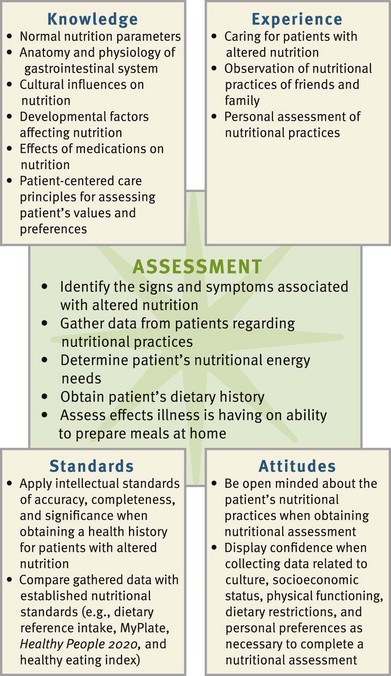

Effective critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge, experience, information collected from patients, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require you to anticipate the required information, analyze the data, and make decisions regarding patient care. Critical thinking is a dynamic process. During assessment (Fig. 44-3) consider all elements that build toward making appropriate nursing diagnoses.

Integrate knowledge from nursing and other disciplines, previous experiences, and information gathered from patients and families regarding customary food preferences and recent diet history. Use of professional standards such as the DRIs, the USDA MyPlate dietary guidelines, and Healthy People 2020 objectives provide guidelines to assess and maintain patients’ nutritional status. Other professional standards by the American Heart Association (AHA, 2010), the American Diabetes Association (ADA, 2008), The American Cancer Society (ACS, 2011), and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) (Bankhead et al., 2009) are available. These standards are evidence based and regularly updated for optimal patient care.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

Assessment

During the assessment process, thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. Early recognition of malnourished or at-risk patients has a strong positive influence on both short- and long-term health outcomes. Studies indicate that 40% to 55% of adult hospitalized patients are either malnourished or at risk for malnutrition (Mason, 2006). Patients who are malnourished on admission are at greater risk of life-threatening complications such as arrhythmia, sepsis, or hemorrhage during hospitalization.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

Assess patients’ nutritional status by using the nursing history to gather information about factors that usually influence nutrition. As the nurse you are in an excellent position to recognize signs of poor nutrition and take steps to initiate change. Close contact with patients and their families enables you to make observations about physical status, food intake, food preferences, weight changes, and response to therapy. Always ask patients about their food preferences, their values regarding nutrition, and what they expect from nutritional therapy. In attempting to affect eating patterns, you need to understand patient’s values, beliefs, and attitudes about food. Also assess family traditions and rituals related to food, cultural values and beliefs, and nutritional needs. Determine how these factors affect food purchase, preparation, and intake.

Screening

Nutrition screening is an essential part of an initial assessment. Screening a patient is a quick method of identifying malnutrition or risk of malnutrition using sample tools (Charney, 2008). Nutrition screening tools need to gather data on the current condition, stability of the condition, assessment of whether it will worsen, and if the disease process accelerates. These tools typically include objective measures such as height, weight, weight change, primary diagnosis, and the presence of other co-morbidities (Charney, 2008). Combine multiple objective measures with subjective measures related to nutrition to adequately screen for nutritional problems. Identification of risk factors such as unintentional weight loss, presence of a modified diet, or the presence of altered nutritional symptoms (i.e., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation) requires nutritional consultation.

Several standardized nutrition screening tools are available for use in the outpatient setting. The Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) uses the patient history, weight, and physical assessment data to evaluate nutritional status (Charney, 2008). SGA is a simple, inexpensive technique that is able to predict nutrition-related complications. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) (Fig. 44-4) was developed to use for screening older adults in home care programs, nursing homes, and hospitals. The tool has 18 items that are divided into screening and assessment. If a patient scores 11 or less on the screening portion, the health care provider completes the assessment portion (Kondrup et al., 2003). A total score of less than 17 indicates protein-energy malnutrition (Guigoz et al., 1996; Guigoz and Vellas, 1999). The Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST) is an effective measure of nutritional problems for patients in a variety of health care settings (Charney, 2008).

FIG. 44-4 Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA). (Copyright © Nestlé, 1994, Revision 2009. N67200 12/99 10M.)

Assess patients for malnutrition when they have conditions that interfere with their ability to ingest, digest, or absorb adequate nutrients. Use standardized tools to assess nutrition risks when possible. Congenital anomalies and surgical revisions of the GI tract interfere with normal function. Patients fed only by IV infusion of 5% or 10% dextrose are at risk for nutritional deficiencies. Chronic diseases or increased metabolic requirements are risk factors for development of nutritional problems. Infants and older adults are at greatest risk.

Anthropometry

Anthropometry is a measurement system of the size and makeup of the body. Nurses obtain height and weight for each patient on hospital admission or entry into any health care setting. If you are not able to measure height with the patient standing, position him or her lying flat in bed as straight as possible with arms folded on the chest and measure him or her lengthwise. Serial measures of weight over time provide more useful information than one measurement. The patient needs to be weighed at the same time each day, on the same scale, and with the same clothing or linen. Document his or her weight and compare height and weight to standards for height-weight relationships. An ideal body weight (IBW) provides an estimate of what a person should weigh. Rapid weight gain or loss is important to note because it usually reflects fluid shifts. One pint or 500 mL of fluid equals 1 lb (0.45 kg). For example, for a patient with renal failure, a weight increase of 2 lbs (0.90 kg) in 24 hours is significant because it usually indicates that the patient has retained a liter (1000 mL) of fluid.

Other anthropometric measurements often obtained by dietitians help identify nutritional problems. These include the ratio of height-to-wrist circumference, midupper arm circumference (MAC), triceps skinfold (TSF), and midupper arm muscle circumference (MAMC). A dietitian will compare values for MAC, TSF, and MAMC to standards and calculate them as a percentage of the standard. Changes in values for an individual over time are of greater significance than isolated measurements (Nix, 2009).

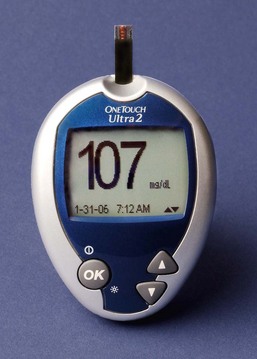

Body mass index (BMI) measures weight corrected for height and serves as an alternative to traditional height-weight relationships. Calculate BMI by dividing the patient’s weight in kilograms by height in meters squared: Weight (kg) divided by height2 (m2). For example, a patient who weighs 165 lbs (75 kg) and is 1.8 m (5 feet 9 inches) tall has a BMI of 23.15 (75 ÷ 1.82 = 23.15). The website for the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (http://www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/) provides an easy way to calculate BMI. A patient is overweight if his or her BMI is 25 to 30. A BMI of greater than 30 is defined as obesity and places a patient at higher medical risk of coronary heart disease, some cancers, DM, and hypertension.

Laboratory and Biochemical Tests

No single laboratory or biochemical test is diagnostic for malnutrition. Factors that frequently alter test results include fluid balance, liver function, kidney function, and the presence of disease. Common laboratory tests used to study nutritional status include measures of plasma proteins such as albumin, transferrin, prealbumin, retinol binding protein, total iron-binding capacity, and hemoglobin. After feeding, the response time for changes in these proteins ranges from hours to weeks. The metabolic half-life of albumin is 21 days, transferrin is 8 days, prealbumin is 2 days, and retinol binding protein is 12 hours. Use this information to determine the most effective measure of plasma proteins for your patients. Factors that affect serum albumin levels include hydration; hemorrhage; renal or hepatic disease; large amounts of drainage from wounds, drains, burns, or the GI tract; steroid administration; exogenous albumin infusions; age; and trauma, burns, stress, or surgery. Albumin level is a better indicator for chronic illnesses, whereas prealbumin level is preferred for acute conditions (Pagana and Pagana, 2009).

Nitrogen balance is important to determining serum protein status (see discussion of protein in this chapter). Calculate nitrogen balance by dividing 6.25 into the total grams of protein ingested in a day (24 hours). Use laboratory analysis of a 24-hour urinary urea nitrogen (UUN) to determine nitrogen output. For patients with diarrhea or fistula drainage, estimate a further addition of 2 to 4 g of nitrogen output. Calculate nitrogen balance by subtracting the nitrogen output from the nitrogen intake. A positive 2- to 3-g nitrogen balance is necessary for anabolism. By contrast, negative nitrogen balance is present when catabolic states exist.

Diet History and Health History

In addition to the general nursing history, use data from a more specific diet history to assess a patient’s actual or potential needs. Box 44-6 lists some specific assessment questions to ask in the diet history. The diet history focuses on a patient’s habitual intake of foods and liquids and includes information about preferences, allergies, and other relevant areas such as the patient’s ability to obtain food. Gather information about the patient’s illness/activity level to determine energy needs and compare food intake. Your nursing assessment of nutrition includes health status; age; cultural background (see Box 44-5); religious food patterns (see Table 44-3); socioeconomic status; personal food preferences; psychological factors; use of alcohol or illegal drugs; use of vitamin, mineral, or herbal supplements; prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) drugs (see Table 44-2); and the patient’s general nutrition knowledge.

In outpatient settings the patient keeps a 3- to 7-day food diary. This allows you to calculate nutritional intake and to compare it with DRI to see if the patient’s dietary habits are adequate. Use food questionnaires to establish patterns over time (Bankhead et al., 2009). In health care settings nurses collaborate with RDs to complete calorie counts for patients.

Physical Examination

The physical examination is one of the most important aspects of a nutritional assessment. Because improper nutrition affects all body systems, observe for malnutrition during physical assessment (see Chapter 30). Complete the general physical assessment of body systems and recheck relevant areas to evaluate a patient’s nutritional status. The clinical signs of nutritional status (Table 44-4) serve as guidelines for observation during physical assessment.

TABLE 44-4

Physical Signs of Nutritional Status

| BODY AREA | SIGNS OF GOOD NUTRITION | SIGNS OF POOR NUTRITION |

| General appearance | Alert: responsive | Listless, apathetic, cachectic |

| Weight | Weight normal for height, age, body build | Obesity (usually 10% above ideal body weight [IBW]) or underweight (special concern for underweight) |

| Posture | Erect posture; straight arms and legs | Sagging shoulders; sunken chest; humped back |

| Muscles | Well-developed, firm; good tone; some fat under skin | Flaccid, poor tone, underdeveloped tone; “wasted” appearance; impaired ability to walk properly |

| Nervous system control | Good attention span; not irritable or restless; normal reflexes; psychological stability | Inattention; irritability; confusion; burning and tingling of hands and feet (paresthesia); loss of position and vibratory sense; weakness and tenderness of muscles (may result in inability to walk); decrease or loss of ankle and knee reflexes; absent vibratory sense |

| Gastrointestinal function | Good appetite and digestion; normal regular elimination; no palpable organs or masses | Anorexia; indigestion; constipation or diarrhea; liver or spleen enlargement |

| Cardiovascular function | Normal heart rate and rhythm; lack of murmurs; normal blood pressure for age | Rapid heart rate (above 100 beats/min), enlarged heart; abnormal rhythm; elevated blood pressure |

| General vitality | Endurance; energy; sleeps well; vigorous | Easily fatigued; no energy; falls asleep easily; tired and apathetic |

| Hair | Shiny, lustrous; firm; not easily plucked; healthy scalp | Stringy, dull, brittle, dry, thin, and sparse, depigmented; easily plucked |

| Skin (general) | Smooth and slightly moist skin with good color | Rough, dry, scaly, pale, pigmented, irritated; bruises; petechiae; subcutaneous fat loss |

| Face and neck | Uniform color; smooth, pink, healthy appearance; not swollen | Greasy, discolored, scaly, swollen; dark skin over cheeks and under eyes; lumpiness or flakiness of skin around nose and mouth |

| Lips | Smooth; good color; moist; not chapped or swollen | Dry, scaly, swollen; redness and swelling (cheilosis); angular lesions at corners of mouth; fissures or scars (stomatitis) |

| Mouth, oral membranes | Reddish-pink mucous membranes in oral cavity | Swollen, boggy oral mucous membranes |

| Gums | Good pink color; healthy and red; no swelling or bleeding | Spongy gums that bleed easily; marginal redness, inflammation; receding |

| Tongue | Good pink or deep reddish color; no swelling; smooth, presence of surface papillae; lack of lesions | Swelling, scarlet and raw; magenta, beefiness (glossitis); hyperemic and hypertrophic papillae; atrophic papillae |

| Teeth | No cavities; no pain; bright, straight; no crowding; well-shaped jaw; clean with no discoloration | Unfilled caries; missing teeth; worn surfaces; mottled (fluorosis), malpositioned |

| Eyes | Bright, clear, shiny; no sores at corner of eyelids; moist and healthy pink conjunctivae; prominent blood vessels; no fatigue circles beneath eyes | Eye membranes pale (pale conjunctivas); redness of membrane (conjunctival injection); dryness; signs of infection; Bitot’s spots; redness and fissuring of eyelid corners (angular palpebritis); dryness of eye membrane (conjunctival xerosis); dull appearance of cornea (corneal xerosis); soft cornea (keratomalacia) |

| Neck (glands) | No enlargement | Thyroid or lymph node enlargement |

| Nails | Firm, pink | Spoon shape (koilonychia); brittleness; ridges |

| Legs, feet | No tenderness, weakness, or swelling; good color | Edema; tender calf; tingling; weakness |

| Skeleton | No malformations | Bowlegs; knock-knees; chest deformity at diaphragm; prominent scapulae and ribs |

From Nix S: Williams’ basic nutrition and diet therapy, ed 13, St Louis, 2009, Mosby.

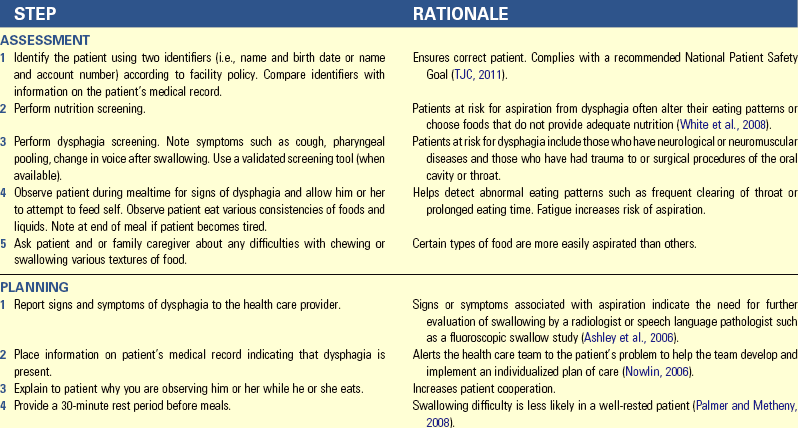

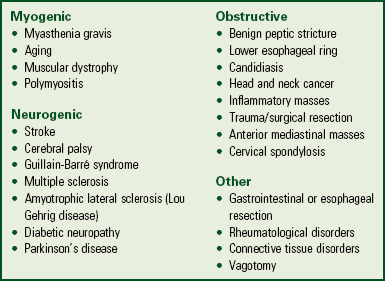

Dysphagia

Dysphagia refers to difficulty swallowing. The causes (Box 44-7) and complications of dysphagia vary. Complications include aspiration pneumonia, dehydration, decreased nutritional status, and weight loss. Dysphagia leads to disability or decreased functional status, increased length of stay and cost of care, increased likelihood of discharge to institutionalized care, and increased mortality (Ashley et al., 2006).

Be aware of warning signs for dysphagia. They include cough during eating; change in voice tone or quality after swallowing; abnormal movements of the mouth, tongue, or lips; and slow, weak, imprecise, or uncoordinated speech. Abnormal gag, delayed swallowing, incomplete oral clearance or pocketing, regurgitation, pharyngeal pooling, delayed or absent trigger of swallow, and inability to speak consistently are other signs of dysphagia. Patients with dysphagia often do not show overt signs such as coughing when food enters the airway. Silent aspiration is aspiration that occurs in patients with neurological problems that lead to decreased sensation. It often occurs without a cough, and symptoms usually do not appear for 24 hours (Palmer and Metheny, 2008). Silent aspiration accounts for most of the 40% to 70% of aspiration in patients with dysphagia following stroke (Kwon et al., 2006).

Dysphagia often leads to an inadequate amount of food intake, which often results in malnutrition. Frequently patients with dysphagia become frustrated with eating and show changes in skinfold thickness and albumin. Adjustment to new dietary restrictions during the rehabilitation period affects intake for long periods of time. Malnutrition significantly slows swallowing recovery and may increase mortality (Robbins et al., 2007).

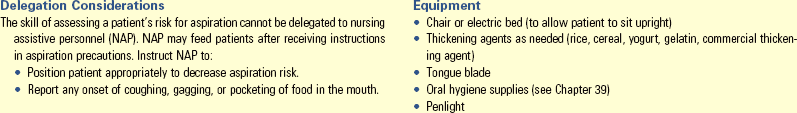

Dysphagia screening quickly identifies problems with swallowing and helps nurses initiate referrals for more in-depth assessment by a speech pathologist (Skill 44-1 on pp. 1026-1027). Early and ongoing assessment of patients with swallowing difficulties and use of a valid dysphagia screening tool increase quality of care and decrease incidence of aspiration pneumonia (AY Cichero et al., 2009). Dysphagia screening includes medical record review; observation of a patient at a meal for change in voice quality, posture, and head control; percentage of meal consumed; eating time; drooling or leakage of liquids and solids; cough during/after a swallow; facial or tongue weakness; palatal movement; difficulty with secretions; pocketing; choking; and presence of voluntary and dry cough. A number of validated screening tools are available, such as the Bedside Swallowing Assessment, Burke Dysphagia Screening Test, Acute Stroke Dysphagia Screen, and Standardized Swallowing Assessment (Edmiaston et al., 2010). The Acute Stroke Dysphagia screen is an easily administered and reliable tool for health care professionals who are not speech-language pathologists. Screening for and treatment of dysphagia requires a multidisciplinary team approach of nurses, RDs, health care providers, and speech language pathologists (SLPs) (Robbins et al., 2007).

Nursing Diagnosis

Cluster all assessment data to identify actual or at-risk nursing diagnoses (Box 44-8). A nutritional problem often occurs when overall intake is significantly decreased or increased or when one or more nutrients are not ingested, completely digested, or completely absorbed. Nursing diagnoses are related to either the actual nutrition problems (e.g., inadequate intake) or problems that place the patient at risk for nutritional deficiencies such as oral trauma, severe burns, or infections.

Select a nursing diagnostic statement based on defining characteristics in the assessment database. Make sure the nursing diagnosis is as precise as possible. The following are examples of nursing diagnoses that apply to nutritional problems:

• Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements

• Imbalanced nutrition: more than body requirements

• Risk for imbalanced nutrition: more than body requirements

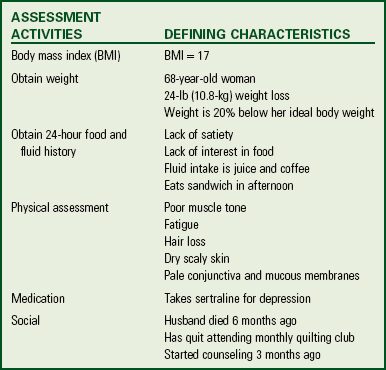

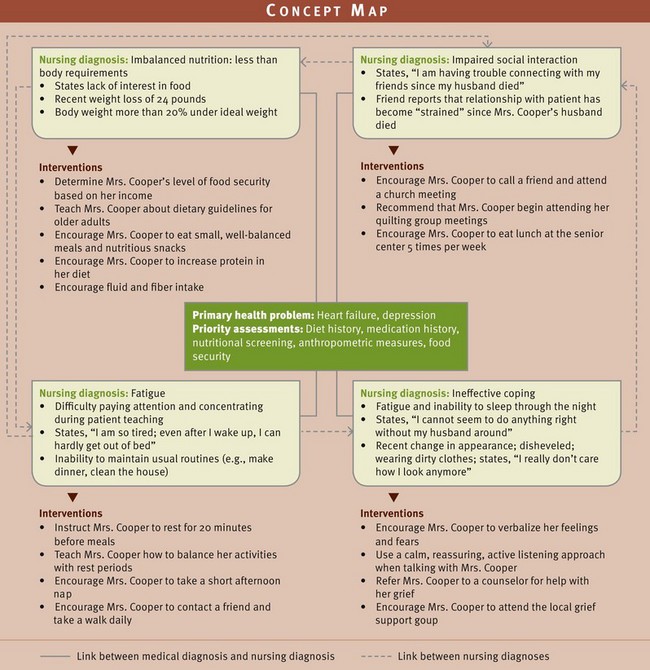

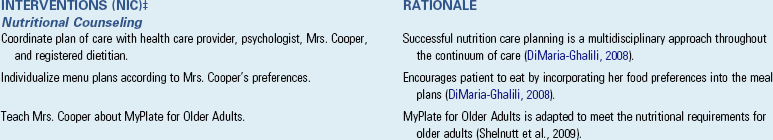

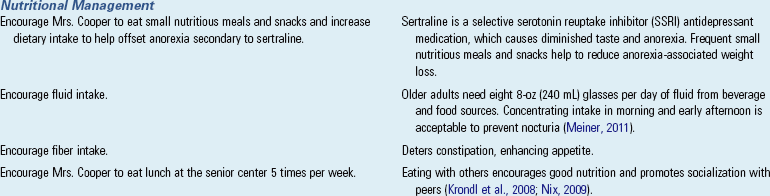

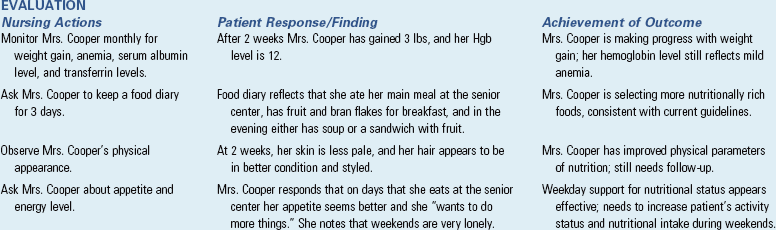

Be sure to select the appropriate related factor for a nursing diagnosis. Related factors need to be accurate so you select the appropriate interventions. In addition, there are also clinical situations in which patients have multiple related problems. The concept map in Fig. 44-5 shows the relationship of nursing diagnoses for Mrs. Cooper.

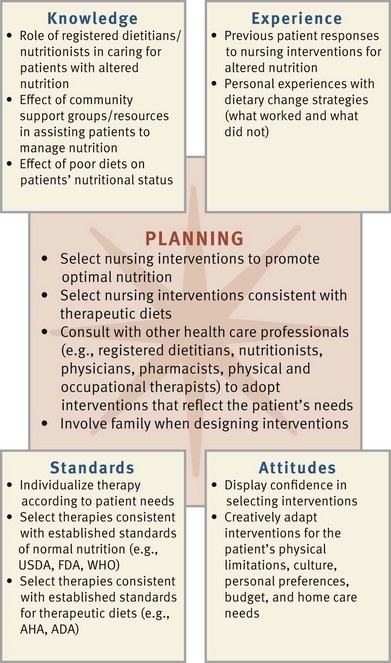

Planning

Planning to maintain patients’ optimal nutritional status requires a higher level of care than simply correcting nutritional problems. Often there is a need for patients to make long-term changes for nutrition to improve. Synthesis of patient information from multiple sources is necessary to create an individualized approach of care that is relevant to a patient’s needs and situation (Fig. 44-6). Apply critical thinking to ensure that you consider all data sources in developing a patient’s plan of care. The accurate identification of nursing diagnoses related to patients’ nutritional problems results in a care plan that is relevant and appropriate (see the Nursing Care Plan). Referring to professional standards for nutrition is especially important during this step, because published standards are based on scientific findings.

FIG. 44-6 Critical thinking model for nutrition planning. ADA, American Diabetes Association; AHA, American Heart Association; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; USDA, U.S. Department of Agriculture; WHO, World Health Organization.

Goals and Outcomes

Goals and outcomes of care reflect a patient’s physiological, therapeutic, and individualized needs. Nutrition education and counseling are important to prevent disease and promote health. Patients on therapeutic diets need to understand the implications of their diets and how prescribed diets help to control their illnesses. When planning care, be aware of all factors that influence a patient’s food intake. In one study patients with heart failure identified that decreased hunger, diet restrictions, fatigue, shortness of breath, anxiety, and sadness influenced their food intake (Lennie et al., 2006).

Individualized planning is essential. Explore patients’ feelings about their weight and diet and help them set realistic and achievable goals (Daniels, 2006). Mutually planned goals negotiated among the patient, RD, and nurse ensure success. For the patient with heart failure described previously, an overall goal is “Patient will achieve appropriate BMI height-weight range or be within 10% of IBW.” The following outcomes assist in achievement of this goal:

• Patient’s daily nutritional intake meets the minimal DRIs.

• Patient’s daily nutritional fat intake is less than 30%.

• Patient removes sugared beverages from diet.

• Patient refrains from eating unhealthy foods between meals and after dinner.

Meeting nutritional goals requires input from the patient and the multidisciplinary team. Knowledge of the role of each discipline in providing nutrition support is necessary to maximize nutritional outcomes. For example, collaboration with an RD helps develop appropriate nutrition treatment plans. Calorie counts are frequently ordered, and assistance is necessary in obtaining accurate data. An effective plan of care requires accurate exchange of information among disciplines.

Setting Priorities

After identifying patients’ nursing diagnoses, you determine priorities in order to plan timely and successful interventions. For example, managing a patient’s oral pain will be a priority over the diagnosis of imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements if the patient is unable to swallow and maintain adequate food intake. Deficient knowledge regarding diet therapy will be a priority if it is necessary to promote long-term and effective weight loss.

During acute illness or surgery the intake of food is often altered in the perioperative period. The priority of care is to provide optimal preoperative nutrition support in patients with malnutrition. The priority for the resumption of food intake after surgery depends on the return of bowel function, the extent of the surgical procedure, and the presence of any complications (see Chapter 50). For example, when patients have oral and throat surgery, they chew and swallow food in the presence of excision sites, sutures, or tissue manipulated during surgery. The priority of care is to first provide comfort and pain control. Then address nutritional priorities and plan care to maintain nutrition that does not cause pain or injury to the healing tissues.

The patient and family must collaborate with the nurse in planning care and setting priorities. This is important because food preferences, food purchases, and preparation involve the entire family. The plan of care cannot succeed without their commitment to, involvement in, and understanding of the nutritional priorities.

Teamwork and Collaboration

The care of the patient often extends beyond the acute hospital setting, requiring continued collaboration among members of the health care team. It is important that discharge planning include nutritional interventions as patients return to their homes or extended care facilities. Communicate patient goals and planned interventions to all team members to achieve expected patient outcomes. Consult with an SLP, RD, pharmacist, and/or occupational therapist when working with patients with dysphagia or who need ongoing nutritional assessment and interventions to meet their nutritional needs.

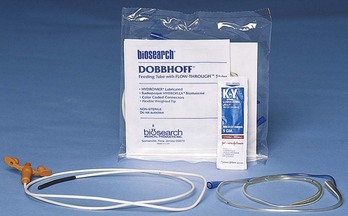

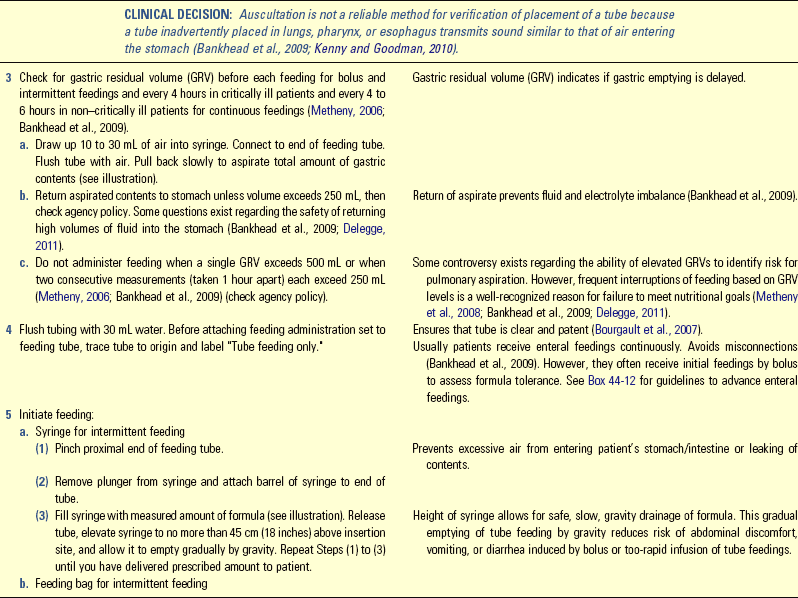

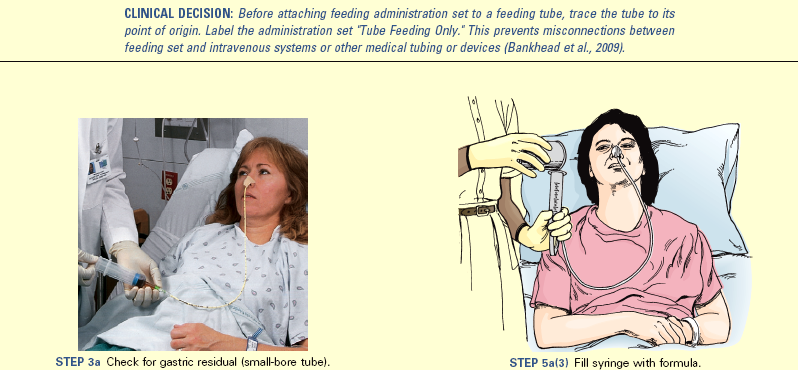

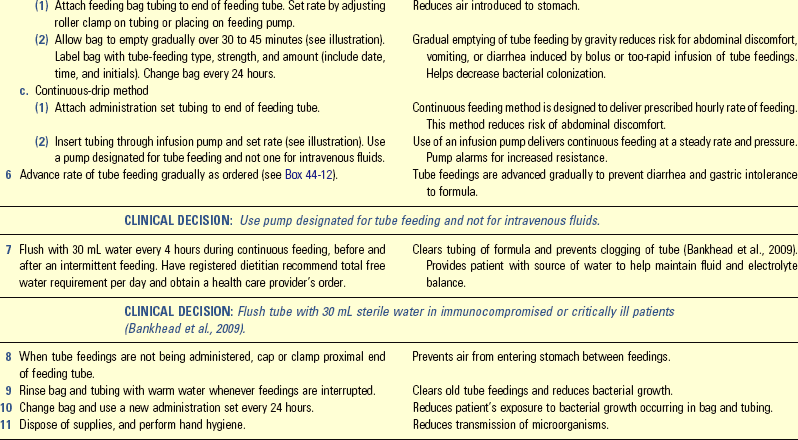

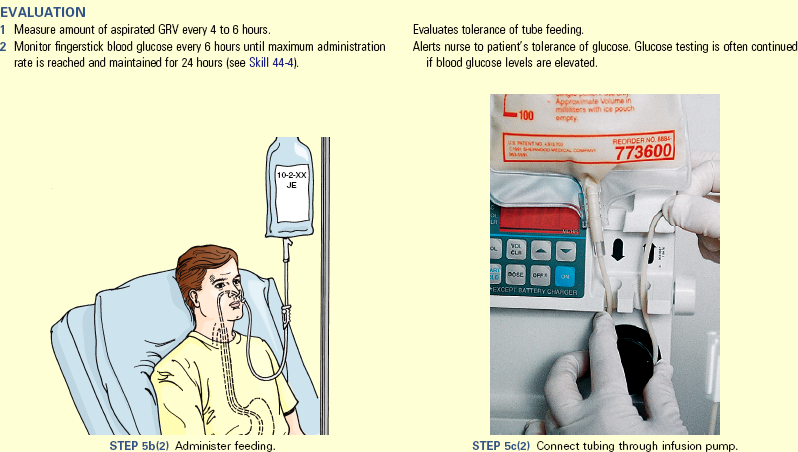

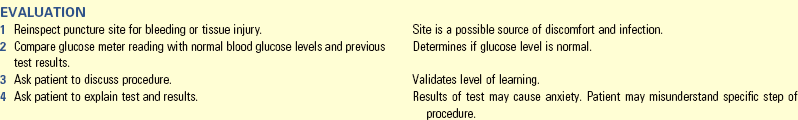

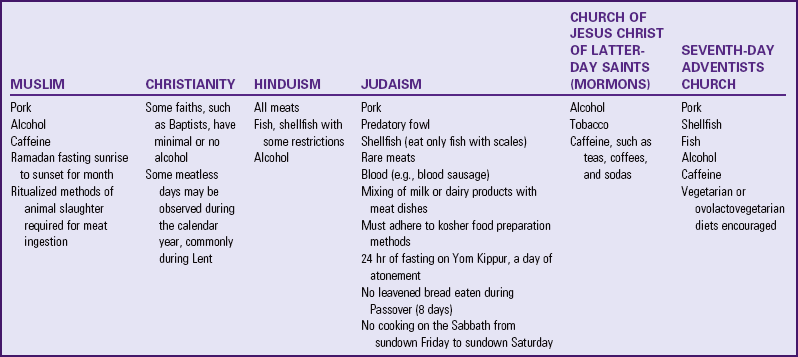

Enteral tube feedings are often administered into the stomach or intestines via a tube inserted through the nose or a percutaneous access (Skills 44-2 and 44-3 on pp. 1028-1035). These enteral feedings supplement a patient’s oral nutritional intake in the home, acute care, extended care, or rehabilitation setting when they cannot meet their nutritional needs by mouth. Regardless of the setting, the RD assesses and monitors the patient’s nutritional status and intake and makes recommendations for changes. RDs are expert in the choice of enteral formulas and dietary modifications required for specific disease states. Long-term management of nutritional problems is a challenge that requires collaboration among the patient, family, and health care team members.

Patients who cannot tolerate nutrition through the GI tract receive parenteral nutrition, a solution consisting of glucose, amino acids, lipids, minerals, electrolytes, trace elements, and vitamins, through an indwelling peripheral or central venous catheter (CVC) (see Chapter 41). The pharmacist is an expert who reviews medications to identify drug-nutrient interactions. Pharmacists are also experts in preparing mixtures of total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

When patients have difficulty feeding themselves, occupational therapists work with them and their families to identify assistive devices. Devices such as utensils with large handles and plates with elevated sides help a patient with self-feeding. An SLP helps a patient with swallowing exercises and techniques to reduce the risk of aspiration. Occupational therapists also help patients maintain function in the home setting by rearranging food preparation areas in an effort to maximize a patient’s functional capacity.

Implementation

Diet therapies are numerous and are chosen on the basis of a patient’s overall health status, ability to eat and digest normally, and long-term nutritional needs. The focus of health promotion is to educate patients and family caregivers about balanced nutrition and to assist them in obtaining resources to eat high-quality meals. In acute care, your role as a nurse is to manage acute conditions that alter patients’ nutritional status and assist in ways to promote their appetite and ability to take in nutrients. Patients who are ill or debilitated often have poor appetites (anorexia). Anorexia has many causes (e.g., pain, fatigue, and the effects of medications). Help patients understand the factors that cause anorexia and use creative approaches to stimulate appetite. In the restorative care setting, you will assist patients in learning how to follow the therapeutic diets necessary for recovery and treatment of chronic health conditions.

Health Promotion