Chapter 35 Physical problems and complications in the puerperium

This chapter reviews the care of women who either entered the postpartum period having experienced obstetric or medical complications, including those who did not undergo a vaginal birth, or whose postpartum recovery, regardless of the mode of delivery, did not follow a normal pattern. It includes the care for women with obvious risks for increased postpartum physical morbidity. (The effects of morbidity related to psychological trauma are covered in Chapter 36.)

The need for women-centred and women-led postpartum care

A women-centred approach to care in the postpartum period should assist physical and psychological recovery by being focused on the needs of women as individuals rather than fitting women into a routine care package (DH 2004, MaGuire 2000, NICE 2006). The midwife needs to be familiar with the woman’s background and antenatal and labour history when assessing whether or not the woman’s progress is following the expected postpartum pattern (DH 2004, Garcia et al 1998, Redshaw et al 2007).

The effects of obstetric or medical complications will be described within the context of the ongoing review by the midwife of the woman’s health over the postnatal period. The role of the midwife in these cases is first to identify whether a potentially pathological condition exists and if so, to refer the woman for appropriate investigations and care (NMC 2004). Where the birth involves obstetric or medical complications, a woman’s postpartum care is likely to differ from those women whose pregnancy and labour are considered straightforward. However, it must also be considered that some women have a perception of the whole birth experience as traumatic, although to the obstetric or midwifery staff no untoward events occurred (Singh & Newburn 2000).

Maternal mortality and morbidity after the birth

The discovery of penicillin and the provision of a blood transfusion were major contributions to saving women’s lives over the past century (Loudon 1986, 1987) and maternal death after childbirth where there has been no preceding antenatal complication is now a rare occurrence in the UK (Lewis 2007).

Thrombosis or thromboembolism continues to be the major cause of direct death but, despite the apparent advances in medication and practice, women still die postpartum as a result of haemorrhage or from sepsis associated with genital tract infection (Lewis 2007). The value of this information is to raise awareness of the degree to which care can contribute to the prevention as well as the detection and management of potentially fatal outcomes.

From research, it became clear that maternal morbidity after childbirth was remarkable in the extensive nature of the problems and the duration of time over which such problems continue to be experienced by women (Bick & MacArthur 1995, Brown & Lumley 1998, Garcia & Marchant 1993, Glazener et al 1995, Glazener & MacArthur 2001, MacArthur et al 1991, Marchant et al 1999, Waterstone et al 2003).

The midwife has a duty to undertake midwifery care for at least the first 28 days postpartum. The activities of the midwife are to support the new mother and her family unit by monitoring her recovery after the birth and to offer her appropriate information and advice as part of the statutory duties of the midwife (NMC 2004).

Immediate untoward events for the mother following the birth of the baby

Immediate (primary) postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a potentially life-threatening event which occurs at the point of or within 24 hrs of delivery of the placenta and membranes and presents as a sudden, and excessive vaginal blood loss (see Ch. 29). Secondary, or delayed PPH is where there is excessive or prolonged vaginal loss from 24 hrs after birth and for up to 6 weeks’ postpartum (Cunningham et al 2005a). Unlike primary PPH, which includes a defined volume of blood loss (≥500 mL) as part of its definition, there is no volume of blood specified for a secondary PPH and management differs according to apparent clinical need (Alexander et al 2002).

Regardless of the timing of any haemorrhage, it is most frequently the placental site that is the source. Alternatively, a cervical or deep vaginal wall tear or trauma to the perineum might be the cause in women who have recently given birth. Retained placental fragments or other products of conception are likely to inhibit the process of involution, or reopen the placental wound. The diagnosis is likely to be determined more by the woman’s condition and pattern of events (Hoveyda & MacKenzie 2001, Jansen et al 2005) and is also often complicated by the presence of infection (Cunningham et al 2005b; see Ch. 29).

Maternal collapse within 24 hrs of the birth without overt bleeding

Where no signs of haemorrhage are apparent other causes need to be considered (see Chs 22 and 23). Management of all these conditions requires ensuring the woman is in a safe environment until appropriate treatment can be administered, and meanwhile maintaining the woman’s airway, basic circulatory support as needed and providing oxygen. It is important to remember that, regardless of the apparent state of collapse, the woman may still be able to hear and so verbally reassuring the woman (and her partner or relatives if present) is an important aspect of the immediate care.

Postpartum complications and identifying deviations from the normal

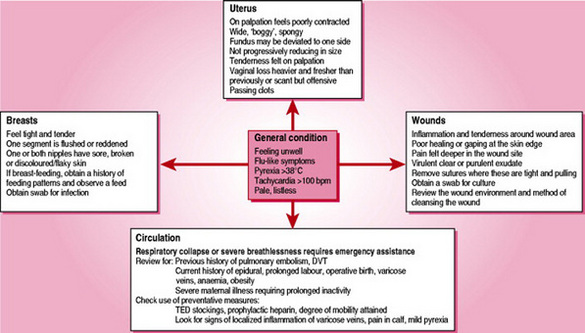

Following the birth of their baby, women recount feelings that are, at one level, elation that they have experienced the birth and survived and, at another, the reality of pain or discomfort from a number of unwelcome changes as their bodies recover from pregnancy and labour (Gready et al 1997). Women may experience symptoms that might be early signs of pathological events. These might be presented by the woman as ‘minor’ concerns, or not actually be in a form that is recognized as abnormal by the woman herself. Where the postpartum visit is undertaken as a form of review of the woman’s physical and psychological health, led by the woman’s needs, the midwife is likely to obtain a random collection of information that lacks a specific structure. Women will probably give information about events or symptoms that are the most worrying or most painful to them at that time. At this point the midwife needs to establish whether there are any other signs of possible morbidity and determine whether these might indicate the need for referral. Figure 35.1 suggests a model for linking together key observations that suggest potential risk of, or actual, morbidity.

Figure 35.1 Diagrammatic demonstration of the relationship between deviation from normal physiology and potential morbidity.

The central point, as with any personal contact, is the midwife’s initial review of the woman’s appearance and psychological state. This is underpinned by a review of the woman’s vital signs, where any general state of illness is evident. It is suggested that a pragmatic approach be taken with regard to evidence of pyrexia as a mildly raised temperature may be related to normal physiological hormonal responses, for example the increasing production of breastmilk. However, infection is an important factor in postpartum maternal morbidity and mortality and the midwife should not make an assumption that a mildly raised temperature is part of the normal health parameters (Lewis 2007). The accumulation of a number of clinical signs will assist the midwife in making decisions about the presence or potential for morbidity. Where there is a rise in temperature above 38 °C it is usual for this to be considered a deviation from normal and of clinical significance.

The pulse rate and respirations are also significant observations when accumulating clinical evidence. Although there may be no evidence of vaginal haemorrhage for example, a weak and rapid pulse rate (>100 b.p.m.) in conjunction with a woman who is in a state of collapse with signs of shock and a low blood pressure (systolic <90 mmHg) may indicate the formation of a haematoma, where there is an excessive leakage of blood from damaged blood vessels into the surrounding tissues. A rapid pulse rate in an otherwise well woman might suggest that she is anaemic but could also indicate increased thyroid or other dysfunctional hormonal activity.

The midwife needs to be alert to any possible relationship between the observations overall and their potential cause with regard to common illnesses, e.g. that the woman has a common cold, and that the morbidity is associated with or affected by having recently given birth. Where the midwife is in conversation with the woman as part of the postpartum review, if she receives information that suggests the woman has signs deviating from what is expected to be normal, it is important that a range of clinical observations are undertaken to refute or confirm this.

Following an innovative research study into extended midwifery care of women beyond the conventional 10–14-day period, a set of guidelines were compiled to assist midwives make decisions about the need for referral (Bick et al 2002). As part of the NICE (2006) process compiling guidelines for core care, it was recognized that midwives develop skills and processes from their experience to accumulate evidence from their observations and conversations about the overall well-being of the mother and the baby. However, this process was mainly covert and difficult to adapt in any formal way to help less experienced midwives or even explain the course of action to the women themselves (Marchant 2006, Marchant et al 2003). To clarify the actions necessary, when the NICE guidelines were published, a quick guide was also produced providing a table of the action required for possible signs/symptoms of complications and common health problems in women (NICE 2006, p 22–24).

The uterus and vaginal loss following vaginal birth

It is expected that the midwife will undertake assessment of uterine involution at intervals throughout the period of midwifery care (see Ch. 34). It is recommended that this should always be undertaken where the woman is feeling generally unwell, has abdominal pain, a vaginal loss that is markedly brighter red or heavier than previously, is passing clots or reports her vaginal loss to be offensive (Hoveyda & MacKenzie 2001, Marchant et al 2006).

Where the palpation of the uterus identifies that it is deviated to one side, this might be as a result of a full bladder. Where the midwife has ensured that the woman had emptied her bladder prior to the palpation, the presence of urinary retention must be considered. Catheterization of the bladder in these circumstances is indicated for two reasons: to remove any obstacle that is preventing the process of involution taking place and to provide relief to the bladder itself. If the deviation is not as a result of a full bladder, further investigations need to be undertaken to determine the cause.

Morbidity might be suspected where the uterus fails to follow the expected progressive reduction in size, feels wide or ‘boggy’ on palpation and is less well contracted than expected. This might be described as subinvolution of the uterus, which can indicate postpartum infection, or the presence of retained products of the placenta or membranes, or both (Howie 1995, Khong & Khong 1993).

Treatment is by antibiotics, oxytocic drugs that act on the uterine muscle, hormonal preparations or evacuation of the uterus (ERPC), usually under a general anaesthetic.

Vulnerability to infection, potential causes and prevention

Infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogenic micro-organisms; the degree to which this results in ill-health relates to their virulence and number. Vulnerability is increased where conditions exist that enable the organism to thrive and reproduce and where there is access to and from entry points in the body. Organisms are transferred between sources and a potential host by hands, air currents and fomites (i.e. agents such as bed linen). Hosts are more vulnerable where they are in a condition of susceptibility because of poor immunity or a pre-existing resistance to the invading organism. The body responds to the invading organisms by forming antibodies, which in turn produce inflammation initiating other physiological changes such as pain and an increase in body temperature.

Acquisition of an infective organism can be endogenous, where the organisms are already present in or on the body (e.g. Streptococcus faecalis (Lancefield group B), Clostridium welchii (both present in the vagina) or Escherichia coli (present in the bowel)) or organisms in a dormant state are reactivated (notably tuberculosis bacteria). Other routes are exogenous, where the organisms are transferred from other people (or animal) body surfaces or the environment. Other transfer mechanisms include droplets – inhalations of respiratory pathogens on liquid particles (e.g. β-haemolytic streptococcus and Chlamydia trachomatis), cross-infection and nosocomial (hospital acquired) transfer from an infected person or place to an uninfected one (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus).

The bacteria responsible for the majority of puerperal infection arise from the streptococcal or staphylococcal species. The Streptococcus bacterium has a chain-like formation and may be haemolytic or non-haemolytic, and aerobic or anaerobic; the most common species associated with puerperal sepsis is the β-haemolytic S. pyogenes (Lancefield group A) although other strains of the streptococcal bacteria have also been identified as the source of serious morbidity (Muller et al 2006). The Staphylococcus bacterium has a grape-like structure, of which the most important species is S. aureus or pyogenes. Staphylococci are the most frequent cause of wound infections; where these bacteria are coagulase positive they form clots on the plasma which can lead to more widely spread systemic morbidity. There is additional concern about their resistance to antibiotics and subsequent management to control spread of the infection. Regardless of the location of care, postpartum women and healthcare professionals should be aware of how infection can be acquired and should pay particular attention to effective hand-washing techniques, adhere to the accepted practice for aseptic technique when in contact with wound care, including the use of gloves for this, and where there is direct contact with areas in the body where bacteria of potential morbidity are prevalent.

The uterus and vaginal loss following operative delivery

A lower segment caesarean section will have involved cutting of the major abdominal muscles and damage to other soft tissues. Palpation of the abdomen is therefore likely to be very painful for the woman in the first few days after the operation. The woman who has undergone a caesarean section will have a very different level of physical activity from the woman who has had a vaginal birth. It may be some hours after the operation until the woman feels able to sit up or move about at all. Blood and debris will have been slowly released from the uterus during this time and, when the woman begins to move, this will be expelled through the vagina and may appear as a substantial fresh-looking red loss. Following this initial loss, it is usual for the amount of vaginal loss to lessen and for further fresh loss to be minimal. All this can be observed without actually palpating the uterus. For women who have undergone an operative delivery, once 3 or 4 days have elapsed, then abdominal palpation to assess uterine involution can be undertaken by the midwife where this appears to be clinically appropriate. By this time, the uterus or area around the uterus should not be overly painful on palpation.

Where clinically indicated, e.g. where the vaginal bleeding is heavier than expected, the uterine fundus can be gently palpated. If the uterus is not well contracted then medical intervention is needed. Uterine stimulants (uterotonics) are usually prescribed in the form of an intravenous infusion of oxytocin or an intravenous or intramuscular injection of ergometrine (see Ch. 29). If the bleeding continues where such treatment has been commenced, further investigations might include obtaining blood for clotting factors, or the woman might need to return to theatre for further exploration of the uterine cavity. The emergence of ultrasound scans (USS) in the postpartum period has led to some conflicting reports of the state of the normal postpartum uterus and the value of USS in distinguishing potentially pathological conditions (Hertzberg & Bowie 1991). Recent studies appear to support greater use of USS to assist diagnosis and clinical management of problems of uterine sub-involution (Deans & Dietz 2006, Shalev et al 2002).

Wound problems

Perineal problems

It is important that the midwife has an understanding of the effect of trauma as a physiological process and the normal pattern for wound healing (Steen 2007). Pain is a direct result of the assault on the nerve endings in the traumatized tissue and where women have undergone perineal trauma that has required suturing, the most immediate problem that occurs soon after the birth is that the woman complains of severe perineal pain. This might be as a result of the analgesia no longer being effective, of increased oedema in the surrounding tissues or, more seriously, of haematoma formation. Haematoma usually develops deep in the perineal fascia tissues and may not be easily visible to the observer if the perineal tissues are already oedematous and discoloured. The blood contained within such a haematoma can exceed 1000 mL and may significantly affect the overall state of the woman, who can present with signs of acute shock. Treatment is by evacuation of the haematoma and resuturing of the perineal wound, usually under a general anaesthetic.

Perineal pain that is severe and is not caused by a haematoma might arise as a result of oedema, causing the stitches to feel excessively tight. Local application of cold packs can bring relief as they reduce the immediate oedema and continue to provide relief over the first few days following the birth (Steen et al 2006). The use of oral analgesia as well as complementary medicines such as arnica and lavender oil are said to have a beneficial effect, although the effectiveness of such therapies has to date not been confirmed by research findings (Bick et al 2009). Midwives should undertake appropriate training in complementary therapies before advocating their use (see Ch. 50).

Factors that are associated with poor healing include poor diet, obesity, pre-existing medical disorders and negative social conditions such as poor housing, increased stress and smoking (Steen 2007). Where pain in the perineal area occurs at a later stage, or re-occurs, this might be associated with an infection. The skin edges are likely to have a moist, puffy and dull appearance; there may also be an offensive odour and evidence of pus in the wound. A swab should be obtained for microorganism culture and referral made to a GP. Antibiotics might be commenced immediately when there is specific information about any infective agent. Where the perineal tissues appear to be infected, it is important to discuss with the woman about cleaning the area and making an attempt to reduce constant moisture and heat. Women might be advised about using cotton underwear, avoiding tights and trousers and frequently changing sanitary pads. They should also be advised to avoid using perfumed bath additives or talcum powder.

If the perineal area fails to heal, or continues to cause pain once the initial healing process should have occurred, resuturing or refashioning might be advised. Postpartum outcomes were recorded for women who took part in a randomised trial looking at the management of the fetal head at the point of birth (McCandlish et al 1998). A total of 7% of women in the study reported perineal pain 3 months after the birth of their baby. This suggests that quite a substantial proportion of women are left with significant problems long after regular contact with healthcare professionals has ceased. This means it is important to give women information about the timescale by which healing should have occurred so that they can seek appropriate advice earlier rather than later. Women may also need to be encouraged to discuss this with their GP, or be given other support where the vaginal or perineal tissues still cause discomfort within the course of daily activities. Women should be pain free and have been able to resume sexual intercourse without pain by 6 weeks after the birth, although some discomfort might still be present depending on the degree of trauma experienced. Although high levels of sexual morbidity after childbirth have been identified, the approach to discussion and management of this area appears to be problematic (Barrett et al 2000). In giving health advice and support, healthcare professionals are advised to identify an appropriate time, not to make assumptions with regard to sexual activity after childbirth and to be conversant with support agencies relevant to a range of cultural and sexual diversities and associated needs (Barrett et al 2000, Glazener 1997, NICE 2006, RCM 2000).

Caesarean section wounds

It is now common practice for women undergoing an operative birth to have prophylactic antibiotics at the time of the surgery (Smaill & Hofmeyr 2000). This has been demonstrated to significantly reduce the incidence of subsequent wound infection and endometritis. In addition, it is now usual for the wound dressing to be removed after the first 24 hrs, as this also aids healing and reduces infection. Advice needs to be offered to the woman about care of her wound and adequate drying when taking a bath or shower, or for more obese women where abdominal skin folds are present and are likely to create an environment that is constantly warm and moist. For these women, a dry dressing over the suture line might be appropriate.

A wound that is hot, tender and inflamed and is accompanied by a pyrexia is highly suggestive of an infection. Where this is observed, a swab should be obtained for microorganism culture and medical advice should be sought. Haematoma and abscesses can also form underneath the wound and women may identify increased pain around the wound where these are present. Rarely a wound may need to be probed to reduce the pressure and allow infected material to drain, reducing the likelihood of the formation of an abscess. With the hospital stay now being much shorter than previously, these problems increasingly occur after the woman has left hospital.

Circulation

Pulmonary embolism remains a major cause of maternal deaths in the UK and midwives and general practitioners need to be more alert to identify high risk women and the possibility of thromboembolism in puerperal women with leg pain and breathlessness (Lewis 2007). Women who have a previous history of pulmonary embolism, a deep vein thrombosis, are obese or who have varicose veins have a higher risk of postpartum problems. Postpartum care of women who have pre-existing or pregnancy-related medical complications relies on prophylactic precautions and should be undertaken for women who undergo surgery and have these pre-existing factors. Thromboembolitic D (TED) stockings should be provided during, or as soon as possible after, the birth and prophylactic heparin prescribed until women attain normal mobility. All women who undergo an epidural anaesthetic, are anaemic, or have a prolonged labour or an operative birth are slightly more at risk of developing complications linked to blood clots. Women with pre-existing problems are at higher risk because of their overall health status and environment of care postpartum. For example, women who undergo a caesarean section as a result of maternal illness are more likely to spend longer in bed, thereby reducing their mobility and increasing their risk of morbidity.

Clinical signs that women might report include the following (from the most common to the most serious). The signs of circulatory problems related to varicose veins are usually localized inflammation or tenderness around the varicose vein, sometimes accompanied by a mild pyrexia. This is superficial thrombophlebitis, which is usually resolved by applying support to the affected area and administering antiinflammatory drugs, where these are not in conflict with other medication being taken or with breastfeeding. Unilateral oedema of an ankle or calf accompanied by stiffness or pain and a positive Homan’s sign might indicate a deep vein thrombosis that has the potential to cause a pulmonary embolism. Urgent medical referral must be made to confirm the diagnosis and commence anticoagulant or other appropriate therapy. The most serious outcome is the development of a pulmonary embolism. The first sign might be the sudden onset of breathlessness, which may not be associated with any obvious clinical sign of a blood clot. Women with this condition are likely to become seriously ill and could suffer a respiratory collapse with very little prior warning.

Some degree of oedema of the lower legs and ankles and feet can be viewed as being within normal limits where it is not accompanied by calf pain (especially unilaterally), pyrexia or a raised blood pressure.

Hypertension

Women who have had previous episodes of hypertension in pregnancy may continue to demonstrate this postpartum for several weeks after the birth (Tan & de Swiet 2002). There is still a risk that women who have clinical signs of pregnancy-induced hypertension can develop eclampsia in the hours and days following the birth although this is a relatively rare outcome in the normal population (Atterbury et al 1998, Tan & de Swiet 2002). In addition, some women appear to develop eclampsia postpartum where there has been no previous history of raised blood pressure or proteinuria (Chames et al 2002, Matthys et al 2004). Some degree of monitoring of the blood pressure should be continued for women who were hypertensive antenatally, and postpartum management should proceed on an individual basis (Tan & de Swiet 2002). For these women, the medical advice should determine optimal systolic and diastolic levels, with instructions for treatment with antihypertensive drugs if the blood pressure exceeds these levels. As women can develop postnatal pre-eclampsia without having antenatal problems associated with this, because the symptoms can be fairly non-specific, such as a headache or epigastric pain or vomiting, the woman may delay or fail to contact a healthcare professional for advice, or where they do seek advice, the healthcare professional may not be alert to the possibility of the development of post-partum eclampsia (Chames et al 2002). Failure to detect symptoms at this initial stage may lead to more serious outcomes as the disease develops untreated (Chames et al 2002, Matthys et al 2004, Tan & de Swiet 2002). Therefore, if a postpartum woman presents with signs associated with pre-eclampsia, the midwife should be alert to this possibility and undertake observations of the blood pressure and urine and obtain medical advice.

For women with essential hypertension, the management of their overall medical condition will be reviewed postpartum by their usual caregivers. Undertaking clinical observation of blood pressure for a period after the birth is advisable so that information is available upon which to base the management of this for the woman in the future (Tan & de Sweit 2002).

Headache

This is a common ailment in the general population; concern in relation to postpartum morbidity should therefore centre around the history of the severity, duration and frequency of the headaches, the medication being taken to alleviate them and how effective this is. As this is also associated with hypertension, a recording of the blood pressure should be undertaken to exclude this as a primary factor. In taking the history, if an epidural analgesic was administered, medical advice should be sought. Headaches from a dural tap typically arise once the woman has become mobile after the birth and they are at their most severe when standing, lessening when the woman lies down. They are often accompanied by neck stiffness, vomiting and visual disturbances. These headaches are very debilitating and are best managed by stopping the leakage of cerebral spinal fluid by the insertion of 10–20 mL of blood into the epidural space; this should resolve the clinical symptoms. Where women have returned home after the birth, they would need to return to the hospital to have this procedure.

Headaches might also be precursors of psychological distress and it is important that other issues related to the birth event are explored, taking the time and opportunity to do this in a sensitive manner. Factors that might be overlooked include dehydration, sleep loss and a greater than usual stressful environment (see Ch. 36). However, the midwife should take time to discuss the woman’s feelings and offer advice or reassurance about these where possible.

Backache

Many women experience pain or discomfort from backache in pregnancy as a result of separation or diastasis of the abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis diastasis, or RAD, see Ch. 16). Where backache is causing pain that affects the woman’s activities of daily living, referral can be made to local physiotherapy services. Pelvic girdle pain experienced in pregnancy should resolve in the weeks after the baby is born but it may continue for a much longer period (Aslan & Fynes 2007).

Urinary problems

Women who have experienced an uncomplicated labour are less likely to experience acute retention of urine following the birth. However, it is still important to monitor urinary function and to ask women about this and the sensations associated with normal bladder control. Management of urine output has been shown to lack consistency and recognition of its potential importance (Zaki et al 2004). For some women a short period of poor bladder control may be present for a few days after the birth, but this should resolve within a week at the most. Women with perineal trauma may have difficulty in deciding whether they have normal urinary control and retention of urine might be detected by the midwife as a result of abdominal palpation of the uterus. Abdominal tenderness in association with other urinary symptoms, for example a poor output, dysuria or offensive urine and a pyrexia or general flu-like symptoms, might indicate a urinary tract infection. Very rarely urinary incontinence might be a result of a urethral fistula following complications from the labour or birth.

Where women have undergone an epidural or spinal anaesthetic, this can have an effect on the neurological sensors that control urine release and flow. This might cause acute retention in some women and be identified within hours of the birth where, as a result of the physiological diuresis, large volumes of urine are produced. In other cases, women may appear to be voiding urine without difficulty but not emptying the bladder each time. They may pass small amounts of urine and be unaware that more urine has remained in the bladder (Lee et al 1999). The main complication of any form of urine retention is that the uterus might be prevented from effective contraction, which leads to increased vaginal blood loss. There is also increased potential for the woman to contract a urine infection with possible kidney involvement and long term effects on bladder function.

It is not uncommon for some women to have a small degree of leakage of urine or retention within the first 2 or 3 days while the tissues recover from the birth, but this should resolve with the practice of postnatal exercise and healing of any localized trauma. Women might feel embarrassed about having urinary problems and midwives may need to consider appropriate ways of encouraging women to talk about any problems so that they can advise women about their future management. Referral to a physiotherapist might be an appropriate first step as pelvic floor exercises and bladder training have been found to improve the outcome significantly in women with long term urinary incontinence (Glazener et al 2001). Specific enquiry about these issues should be made when women attend for their 6-week postnatal examination; further investigations should be made for women who are encountering these problems.

Bowels and constipation

It is the relationship of the regularity of bowel movements to the woman’s previous experience that is likely to assist the midwife in determining whether or not there is a problem. The occurrence of haemorrhoids and constipation is not uncommon during pregnancy and is a result of the influence of progesterone on smooth muscle. Additional factors include following an altered diet, a degree of dehydration during labour and concern about further pain from any perineal trauma. A diet that includes soft fibre, increased fluids and the use of prophylactic laxatives that are non-irritant to the bowel can be prescribed to alleviate constipation, the most common and apparently effective of these being lactulose (Eogan et al 2007). Women need advice that any disruption to their normal bowel pattern should resolve within days of the birth, taking into consideration the recovery required by the presence of perineal trauma. They should also be reassured about the effect of a bowel movement on the area that has been sutured as many women may be unnecessarily anxious about the possibility of tearing their perineal stitches. Where women have prolonged difficulty with constipation, anal fissures can result (Corby et al 1997). These are painful and difficult to resolve and therefore advice about bowel management is important in avoiding this situation. Women who have haemorrhoids should also be given advice on following a diet high in fibre and fluids, preferably water and the use of appropriate laxatives to soften the stools as well as topical applications to reduce the oedema and pain.

It is also of concern where women might experience loss of bowel control and whether this is faecal incontinence. It is important to determine the nature of the incontinence and distinguish it from an episode of diarrhoea. It might be helpful to ask whether the woman has taken any laxatives in the previous 24 hrs and explore what food was eaten. Where the problems do not seem to be associated with other factors the woman should first be advised to see her GP. Faecal incontinence is not always associated with a third degree tear and its prevalence is unclear but it is associated with a range of risk factors that include instrumental birth, and primiparity (Guise et al 2007, Thornton & Lubowski 2006). In the last few years, much more attention has been given to it and recent reports suggest that it is more common than was previously thought (Glazener et al 2001, Guise et al 2007, MacArthur et al 1997). The role of the midwife is to facilitate women to talk about these problems by being proactive in asking women about any problems with bowel control. Where women identify any change to their pre-pregnant bowel pattern by the end of the puerperal period, they should be advised to have this reviewed further whether it is constipation or loss of bowel control.

Anaemia

Paterson et al (1994) conducted a study investigating the clinical finding of postpartum anaemia in over 1000 women and the key factors and outcomes related to these findings. While there are now many more studies about treatment and management of postpartum anaemia, including a Cochrane review, no recent study has been identified to date that demonstrates more clearly the relevant issues for women and for midwifery care. The impact of the events of the labour and birth may leave many women looking pale and tired for a day or so afterwards. Where it is evident that a larger than normal blood loss has occurred, it can be valuable to obtain an overall blood profile within which the red blood cell volume and haemoglobin can be assessed so as to provide appropriate treatment to reduce the effects of the anaemia; these include blood transfusions and iron supplements (Bhandal & Russell 2006, Dodd et al 2004, Paterson et al 1994). The degree to which the haemoglobin level has fallen should determine the appropriate management and this is particularly important in the presence of pre-existing haemoglobinopathies, sickle cell and thalassaemia. Where the haemoglobin level is <9.0 g/dL a blood transfusion might be appropriate, otherwise oral iron and appropriate dietary advice are advocated where the level is <11.0 g/dL. However, where the woman has returned home soon after the birth, the postpartum woman’s haemoglobin values might not have been undertaken where there was no history of anaemia prior to labour and the blood loss at birth was not assessed as excessive. If there is no clinical information to hand, the midwife needs to rely on the woman’s clinical symptoms; if these include lethargy, tachycardia and breathlessness as well as a clinical picture of pale mucous membranes, it would be prudent to arrange for the blood profile to be reviewed. Some researchers have questioned blood loss estimation after childbirth as well as the timing of blood tests taken to assess the physiological impact of this (Jansen et al 2007, Paterson et al 1994). Therefore the postnatal day when the haemoglobin test was taken might have a clinically significant bearing on the subsequent management.

Breast problems

Regardless of whether women are breastfeeding, they may experience tightening and enlargement of their breasts towards the 3rd or 4th day as hormonal influences encourage the breasts to produce milk (see Ch. 41). For women who are breastfeeding the general advice is to feed the baby and avoid excessive handling of the breasts. Simple analgesics may be required to reduce discomfort. For women who are not breastfeeding, the advice is to ensure that the breasts are well supported but that this is not too constrictive and, again, that taking regular analgesia for 24–48 hrs should reduce the discomfort. Heat and cold applied to the breasts via a shower or a soaking in the bath may temporarily relieve acute discomfort as well as the use of chilled cabbage leaves (Nikodem et al 1993, Roberts et al 1995).

Practical skills for postpartum midwifery care after an operative birth

In the immediate period after an operative birth, the attendant will be closely monitoring recovery from the anaesthetic used for the caesarean section. If the operation was performed under a general anaesthetic, the attendant will observe for signs of cognitive recovery and reorientation as well as taking the usual recording of temperature, pulse, respiration rate and blood pressure. Women who have undergone a spinal anaesthetic will also require monitoring of the level of sensation of their lower body and limbs. Regular observation of vaginal loss, leakage on to wound dressings and fluid loss in any ‘redivac’ drain system should also be undertaken.

Once the woman has fully recovered from the operation she should be transferred to a ward environment. Midwifery care involves the overall framework of core care (see Ch. 34). Appropriate care is to assess the needs of the individual woman and to formalize this within a stated pattern of care so that she and caregivers have similar and agreed expectations (DH 2004, RCM 2000). Women who have undergone an operative delivery need time to recover from a major physical shock to the systems of the body, for optimal conditions to allow tissue repair to take place as well as psychological adjustment to the events of the birth.

Women who have undergone an operative birth will require assistance with a number of activities they would otherwise have done themselves. In the hospital environment, they will need help to maintain their personal hygiene, to get out of bed and to start to care for their baby. The rate at which each woman will be able to regain control over these areas of activity is highly individual. It is strongly suggested that caregivers should not expect all women to have reached a certain level of recovery in line with their ‘postnatal day’. Using such a framework to assess the degree to which a woman is recovering from a major operation leads to a tendency to become judgemental. Women may view undergoing a caesarean section or any complication in the birth in different ways depending on their social and cultural background and this might have associations to their ongoing psychological health (Chien et al 2006, McCourt 2006).

It is now common for women to have a much shorter period in hospital after birth; some women might return home 72 hrs after a major operation with very minimal support. Practical advice about the management of their recovery and use of resources at home is also within the remit of midwifery postpartum care. For example; the midwife might suggest that the woman identifies what she will need for herself and the baby and gather this together in one place at the start of the day to reduce the need to go upstairs too often. Alongside this, women can be encouraged to go out with their baby when someone is available to help with all the baby transportation equipment; this will encourage venous return and cardiac output at a level that is beneficial rather than exhausting.

One aspect of current care that can be misunderstood is the need for mobility after surgery. Although women may be supplied with thromboembolitic stockings prior to the operation and be prescribed an anticoagulant regimen such as heparin, women need to be encouraged to mobilize as soon as practical after the operation to reduce the risk of circulatory problems. Although women need an explanation that mobility is of benefit soon after the birth, it is also an important part of care to recognize when the woman has reached her limit with regard to physical activity and may need to rest. Regular use of appropriate analgesia should be made available to women where this is required.

Psychological deviation from normal

Psychological distress and psychiatric illness in relation to childbirth are covered in depth in Chapter 36. However, it is relevant to reflect here on the possible importance of the relationship that develops between the woman and the midwife during their contact postpartum. Clearly, such relationships are of greater depth where there has been antenatal contact or a degree of continuity postpartum, or both, and women have commented positively where such continuity has been achieved (Singh & Newburn 2000). This prior knowledge can mean that the midwife might detect or be concerned about a change in the woman’s behaviour that has not been noticed by her family. Any initial concerns of the mother or the family should be explored by the midwife making use of open questions and listening skills during the visit in the home or the contact time in the hospital setting (NICE 2007). Behavioural changes may be very subtle, but, however small, they might be of importance in the woman’s overall psychological state; it is the balance between the woman’s physical condition and her psychological state that might influence an eventual decision to refer for expert advice.

Although the woman and her partner are likely to have an expectation of reduced sleep once the baby is born, the actual experience of this can have very varied effects on individual women. The cause of the lack of sleep or tiredness is what is important – is it being unable to get to sleep as a result of anxiety about the future and what is, as yet, unknown? This might include fears about the possibility of a cot death, or a lack of confidence in coping as a mother, or financial or relationship worries. The opportunity to sleep might be reduced because the feeding is not yet established or the baby is not in a settled environment and so the mother is constantly disturbed when she tries to sleep. In addition, other people may not be allowing the mother to sleep when the baby does not need her attention. Unravelling these issues can help the midwife and the women to determine what is the underlying cause and whether management of this could improve the situation. As a result of this enquiry, women who come into the category where anxiety prevents them from sleeping when the opportunity arises may benefit from interagency support. Alternatively, where there is a physiological reason for the tiredness, as a result of anaemia for example, the situation can be managed clinically (Jansen et al 2007). The midwife is an important member of the primary health care team and should operate within an interagency context (see Ch. 36).

Talking after childbirth

The essence of the contact between the woman and the midwife after the birth event is to strive to maintain a framework of support and advice that existed antenatally. Within the current provision of care, it is not always possible to achieve the continuity of carer postnatally and some women will have postnatal home visits from several different midwives possibly previously unknown to them.

Once the birth is over and the woman has returned to her home environment, there may be aspects of the birth that she does not understand or that even distress her to think about. Where appropriate, a midwife undertaking postnatal care in the woman’s home might be able to help the woman review and reflect on the birth by talking about it and identifying her concerns and anxieties. Where necessary, the midwife can facilitate referral to the key people involved in order that the woman can discuss the birth or see the notes kept of the birth and clarify any outstanding issues (Allen 1999, Charles & Curtis 1994, NICE 2006). Other forms of support, for instance specific counselling for those with traumatic emotional experiences, might also be appropriate under professional guidance (NICE 2007) (see Ch. 36).

Allen H. Debriefing for postnatal women: does it help? Professional Care of Mother and Child. 1999;9(3):77-79.

Alexander J, Thomas P, Sanghera J. Treatments for secondary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2002.

Aslan E, Fynes M. Symphysial pelvic dysfunction. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;19(2):133-139.

Atterbury JL, Groome L, Hoff C, et al. Clinical presentation of women re-admitted with postpartum severe pre-eclampsia or eclampsia. Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Neonatal Nursing. 1998;27(2):134-141.

Barrett G, Pendry E, Peacock J, et al. Women’s sexual health after childbirth. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;107(2):186-195.

Bick D, MacArthur C. The extent, severity and effect of health problems after childbirth. British Journal of Midwifery. 1995;3:27-31.

Bick D, MacArthur C, Knowles H, et al. Postnatal care: evidence and guidelines for management, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2009.

Bhandal N, Russell R. Intravenous versus oral iron therapy for postpartum anaemia. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113(11):1248-1252.

Brown S, Lumley J. Maternal health after childbirth: results of an Australian population based study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105:156-161.

Chames MC, Livingston JC, Ivester TS, et al. Late postpartum eclampsia: a preventable disease? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;186(6):1174-1177.

Charles J, Curtis L. Birth afterthoughts: a listening and information service. British Journal of Midwifery. 1994;2(7):331-334.

Chien LY, Tai CJ, Ko YL, et al. Adherence to ‘doing-the-month’ practices is associated with fewer physical and depressive symptoms among postpartum women. Taiwan Research in Nursing and Health. 2006;29(5):374-383.

Corby H, Donnelly VS, O’Herlihy C, et al. Anal canal pressures are low in women with postpartum anal fissure. British Journal of Surgery. 1997;84(1):86-88.

Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom S, et al, editors. Maternal physiology, 22nd edn. Williams obstetrics. McGraw Hill Medical, New York, 2005:121-150. 695–710

Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom S, et al, editors. Puerperal infection, 22nd edn. Williams obstetrics. McGraw Hill Medical, New York, 2005;710-724.

Deans R, Dietz HP. Ultrasound of the post-partum uterus Australian and New Zealand. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;46(4):345-349.

DH ( Department of Health ). National Service Framework for Children. Young People and Maternity Services. Stationery office, London, 2004. Section 11

Dodd J, Dare MR, Middleton P. Treatment for women with postpartum iron deficiency anaemia. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2004.

Eogan M, Daly L, Behan M, et al. Randomised clinical trial of a laxative alone versus a laxative and a bulking agent after primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter injury. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;114(6):736-740.

Garcia J, Marchant S. Back to normal? Postpartum health and illness. Research and the Midwife Conference Proceedings, 1992, University of Manchester, Manchester, 1993, 2-9.

Garcia J, Redshaw M, Fitzsimmons B, et al. First class delivery, a national survey of women’s views of maternity care. Abingdon: Audit Commission, 1998.

Glazener C, Abdalla M, Stroud P, et al. Postnatal maternal morbidity: extent, causes, prevention and treatment. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1995;102(4):282-287.

Glazener C. Sexual function after childbirth: women’s experiences, persistent morbidity and lack of professional recognition. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:330-335.

Glazener C, Herbison GP, Wilson CD, et al. Conservative management of persistent postnatal urinary and faecal incontinence: a randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 2001;323:593-598.

Glazener CMA, MacArthur C. Postnatal morbidity Obstetrician and Gynaecologist. 2001;3(4):179-183.

Gready M, Buggins E, Newburn M, et al. Hearing it like it is: understanding the views of users. British Journal of Midwifery. 1997;5(8):496-500.

Guise JM, Morris C, Osterweil P, et al. Incidence of fecal incontinence after childbirth. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;109(2 Part 1):281-288.

Hertzberg B, Bowie J. Ultrasound of the postpartum uterus. Journal of Ultrasound Medicine. 1991;10:451-456.

Howie PW. The puerperium and its complications. In: Whitfield C, editor. Dewhurst’s textbook of obstetrics and gynaecology. 5th edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1995:421-437.

Hoveyda F, MacKenzie IZ. Secondary postpartum haemorrhage: incidence, morbidity and current management. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2001;108(9):927-930.

Jansen AJG, van Rhenen DJ, Steegers EAP, et al. Postpartum hemorrhage and transfusion of blood and blood components. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey. 2005;60(10):663-671.

Jansen AJ, Duvekot JJ, Hop WC, et al. New insights into fatigue and health-related quality of life after delivery. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2007;86(5):579-584.

Khong TY, Khong TK. Delayed postpartum haemorrhage: a morphologic study of causes and their relation to other pregnancy disorders. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;82(1):17-22.

Lee SNS, Lee CP, Tang OSF, et al. Postpartum urinary retention. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 1999;66:287-288.

Lewis G. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003–2005. The seventh report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. CEMACH, London, 2007.

Loudon I. Obstetric care, social class, and maternal mortality. British Medical Journal. 1986;293:606-608.

Loudon I. Puerperal fever, the streptococcus, and the sulphonamides, 1911–1945. British Medical Journal. 1987;295:485-490.

MacArthur C, Bick DE, Keighley M. Faecal incontinence after childbirth. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:46-50.

MacArthur C, Lewis M, Knox G. Health after childbirth: an investigation of long term health problems beginning after childbirth in 11701 women. London: HMSO, 1991.

McCandlish R, Bowler U, van Asten H, et al. A randomised controlled trial of care of the perineum during second stage of normal labour. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105(2):1262-1272.

McCourt C. Becoming a parent. In: Page LA, McCandlish R, editors. The new midwifery: science and sensitivity in practice. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2006:54-56.

MaGuire M. The transition to parenthood. In: Life after birth: reflections on postnatal care, report of a multi-disciplinary seminar. London: Royal College of Midwives; 2000. 3rd July

Marchant S, Alexander J, Garcia J, et al. A survey of women’s experiences of vaginal loss from 24 hours to three months after childbirth (the BLiPP Study) Midwifery. 1999;15(2):72-81.

Marchant S, Alexander J, Garcia J. Routine midwifery assessment of postpartum uterine involution. In: Wickham S, editor. Midwifery best practice. London: Elsevier, 2003.

Marchant S. The postnatal care journey are we nearly there yet? MIDIRS Midwifery Digest. 2006;16(3):295-304.

Marchant S, Alexander J, Thomas P, et al. Risk factors for hospital admission related to excessive and/or prolonged postpartum vaginal blood loss after the first 24 h following childbirth. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2006;20(5):392-402.

Matthys LA, Coppage KH, Lambers DS, et al. Delayed postpartum preeclampsia: an experience of 151 cases. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;190(5):1464-1466.

Muller AE, Oostvogel PM, Steegers EAP, et al. Morbidity related to maternal group B streptococcal infections. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2006;85(9):1027-1037.

NICE (National Institute for Health and Excellence). Routine postnatal care of women and their babies. London: NICE, 2006.

NICE (National Institute for Health and Excellence). Antenatal and postnatal mental health: Clinical management and service guidance. London: NICE, 2007.

Nikodem VC, Danziger D, Gebka N, et al. Do cabbage leaves prevent breast engorgement? A randomized, controlled study. Birth. 1993;20(2):61-64.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council). Midwives rules and standards. London: NMC, 2004.

Paterson J, Davis J, Gregory M, et al. A study on the effects of low haemoglobin on postnatal women. Midwifery. 1994;16:77-86.

RCM (Royal College of Midwives). Midwifery practice in the postnatal period: recommendations for practice. London: Davies Communications, 2000.

Redshaw M, Rowe R, Hockley C, et al. Recorded delivery: a national survey of women’s experience of maternity care. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, 2007.

Roberts KL. A comparison of chilled cabbage leaves and chilled gelpaks in reducing breast engorgement. Journal of Human Lactation. 1995;11(1):17-20.

Shalev J, Royburt M, Fite G, et al. Sonographic evaluation of the puerperal uterus: correlation with manual examination. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 2002;53:38-41.

Singh D, Newburn M, editors. Access to maternity information and support: the experiences and needs of women before and after giving birth. London: National Childbirth Trust, 2000.

Smaill F, Hofmeyr GJ. Antibiotic prophylaxis for caesarean section (Cochrane review). The Cochrane Library. (Issue 3):2000. Update Software,Oxford

Steen M, Briggs M, King D. Alleviating postnatal perineal trauma: to cool or not to cool? British Journal of Midwifery. 2006;14(5):304-306. 308

Steen M. Perineal tears and episiotomy: how do wounds heal? British Journal of Midwifery. 2007;15(5):273-274. 276–280

Tan LK, deSwiet M. The management of postpartum hypertension. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;109(7):733-736.

Thornton MJ, Lubowski DZ. Obstetric-induced incontinence: a black hole of preventable morbidity. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;46(6):468-473.

Waterstone M, Wolfe C, Hooper R, et al. Postnatal morbidity after childbirth and severe obstetric morbidity. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2003;110(2):128-133.

Zaki MM, Pandit M, Jackson S. National survey for intrapartum and postpartum bladder care: assessing the need for guidelines. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;111(8):874-876.