Chapter 41 Infant feeding

The establishment of good feeding practices has become even more essential given the recent increase in obesity and allergies in children in the UK. Breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is the ideal start for babies and midwives have a key role in supporting mothers to breastfeed successfully. For those mothers who are unable to or choose not to breastfeed, the midwife has an equally important role in ensuring families safely and appropriately feed their babies.

The breast and breastmilk

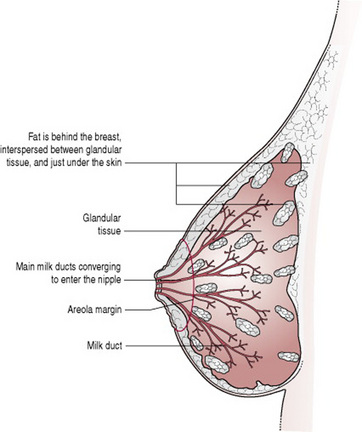

Anatomy and physiology of the breast (Fig. 41.1)

The breasts are compound secreting glands, composed of varying proportions of fat, glandular and connective tissue, arranged in lobes. Each lobe is divided into lobules that consist of alveoli and ducts.

As there is an intimate and congruous connection between the fat and glandular tissue within the breast (Nickell & Skelton 2005), the relative proportion of fat to glandular tissue is difficult to calculate non-invasively.

However, analysis of 21 non-lactating breasts (surgically removed for carcinoma in situ), (Vandeweyer & Hertens 2002) revealed that the percentage weight of fat per total breast varied from 3.6 to 37.6. Mammographic studies of non-lactating breasts have reported breast glandularity decreasing with age (Jamal et al 2004).

Investigations carried out on 25 sections of central breast tissue removed during breast reduction operations (performed on women with an average BMI of 28) found a mean of 61% fat (Cruz-Korchin et al 2002). On average, the central breast area in these women also contained only 7% glandular tissue and 29% connective tissue.

This finding, that larger breasts contain relatively more fat, is supported by an observational study of 136 patients (with an average BMI of 32), undergoing breast reduction surgery (Nickell & Skelton 2005).

Research on the volumes of 20 complete duct systems (‘lobes’) in an autopsied breast, found considerable variation in the proportion of breast tissue ‘serviced’ by each duct; the largest ‘lobe’ drained 23% of breast volume; half of the breast was drained by three ducts and 75% by the largest six. Conversely, eight small duct systems together accounted for only 1.6% of breast volume (Going & Moffat 2004).

Ultrasound investigations of the lactating breasts of 21 subjects (Ramsay et al 2005) have identified nine or so milk ducts per breast (range 4–18), which is fewer than previously believed, and in agreement with investigations conducted by Love and Barsky (2004).

Taneri et al (2006) examined 226 mastectomy specimens and found the mean number of ducts in the nipple duct bundle was 17.5. This is significantly higher than the number reported to open on the nipple surface. They reflected that this discrepancy could be due to duct branching within the nipple or the presence of some ducts which do not reach the nipple surface.

Taken together, the intimate and inseparable relationship between fat and glandular tissue, the uneven distribution of milk glands and the high variability in the number of milk ducts, have implications for those who need breast surgery, particularly breast reduction surgery, since in some cases the loss of only a few ducts may inadvertently compromise a woman’s future ability to breastfeed (see Breast surgery, below).

The alveoli contain acini cells, which produce milk and are surrounded by myoepithelial cells, which contract and propel the milk out (Fig. 41.2). Small lactiferous ducts, carrying milk from the alveoli, unite to form larger ducts. Several large ducts (lactiferous tubules) conveying milk from one or more lobe emerge on the surface of the nipple. Myoepithelial cells are oriented longitudinally along the ducts and, under the influence of oxytocin, these smooth muscle cells contract and the tubule becomes shorter and wider (Ramsay et al 2004, Woolridge 1986). The tubule distends during active milk flow, while the myoepithelial cells are maintained in a state of contraction by circulating oxytocin (2–3 min). The fuller the breast when let down occurs, the greater the degree of ductal distension (Ramsay et al 2004).

The nipple, composed of erectile tissue, is covered with epithelium and contains smooth muscle and elastic fibres, which form a tight sphincter at the end of the teat (as in most mammals; Cross 1977), to prevent unwanted loss of milk from the mammary gland when it is not being suckled.

Surrounding the nipple is an area of pigmented skin called the areola, which contains Montgomery’s glands. These produce a sebum-like substance, which acts as a lubricant during pregnancy and throughout breastfeeding. Breasts, nipples and areolae vary considerably in size from one woman to another.

The breast is supplied with blood from the internal and external mammary arteries and branches from the intercostal arteries. The veins are arranged in a circular fashion around the nipple. Lymph drains freely from the two breasts into lymph nodes in the axillae and the mediastinum.

During pregnancy, oestrogens and progesterone induce alveolar and ductal growth as well as stimulating the secretion of colostrum. Other hormones are also involved and they govern a complex sequence of events, which prepare the breast for lactation. Although colostrum is present from the 16th week of pregnancy, the production of milk is held in abeyance until after the birth, when the levels of placental hormones fall. This allows the already high levels of prolactin to initiate milk production. Continued production of prolactin is caused by the baby feeding at the breast, with concentrations highest during night feeds. Prolactin is involved in the suppression of ovulation, and some women may remain anovular until lactation ceases, although for others this effect is not so prolonged (Kennedy et al 1989, Ramos et al 1996) (see Ch. 37).

If breastfeeding (or expressing) has to be delayed for a few days, lactation can still be initiated because prolactin levels remain high, even in the absence of breast use, for at least the first week (Kochenour 1980), although the establishment of lactation will be more secure if breastfeeding or expressing begins as shortly after birth as possible.

Prolactin seems to be much more important to the initiation of lactation than to its continuation. As lactation progresses, the prolactin response to suckling diminishes and milk removal becomes the driving force behind milk production.

This is now known to be due to the presence in secreted milk of a whey protein that is able to inhibit the synthesis of milk constituents (Daly 1993, Prentice et al 1989, Wilde et al 1995).

This protein accumulates in the breast as the milk accumulates and it exerts negative feedback control on the continued production of milk. Removal of this autocrine inhibitory factor, (sometimes referred to as FIL – feedback inhibitor of lactation) by removing the milk, allows milk production to be stepped up again.

It is because this mechanism acts locally (i.e. within the breast) that each breast can function independently of the other. It is also the reason that milk production slows as the baby is gradually weaned from the breast. If necessary, it can be stepped up again if the baby is put back to the breast more often (e.g. because of illness).

Milk is synthesized continuously into the alveolar lumen, where it is stored until milk removal from the breast is initiated. It is only when oxytocin is released, and the myoepithelial cells contract, that milk is made available to the suckling infant.

Milk release is under neuroendocrine control. Tactile stimulation of the breast also stimulates the oxytocin, causing contraction of the myoepithelial cells. This process is known as the ‘let-down’ or ‘milk-ejection’ reflex and makes the milk available to the baby. This occurs in discrete pulses throughout the feed and may well trigger the bursts of active feeding.

In the early days of lactation, this reflex is unconditioned. Later, as it becomes a conditioned reflex, the mother may find her breasts responding to the baby’s cry (or other circumstances associated with the baby or feeding). In one small study, psychological stress (mental arithmetic or noise) was found to reduce the frequency of the oxytocin pulses, however there was no effect on the amplitude of the pulse. Neither was there any effect on either prolactin levels or the amount of milk the baby received (Ueda et al 1994).

Milk production and the mother

The human mother manages the process of lactation in an entirely different way from her non-primate counterpart. Much of the mis-information to which mothers are subjected derives from extrapolation from veterinary and dairy science (Woolridge 1995). Adequate milk production is largely independent of the mother’s nutritional status and body mass index (Prentice et al 1994).

Not only have dietary surveys in developed countries consistently found their calorie intake to be less than the recommended amount (Butte et al 1984, Whitehead et al 1981), but controlled trials conducted in developing countries have demonstrated that giving extra food to mothers, even those who were poorly nourished, did not increase the rate of growth of their babies (Prentice et al 1980, 1983).

It has been suggested that metabolic efficiency is enhanced in lactating women, who are therefore able to conserve energy and ‘subsidize’ the cost of their milk production (Illingworth et al 1986).

The lactational performance of the human female must become compromised when under-nutrition is sufficiently severe, but it appears that this occurs only in famine or near famine conditions.

As milk production would appear to ‘drive’ appetite, rather than the reverse, hunger will effectively regulate the calorie intake of a breastfeeding woman, and the practice of encouraging breastfeeding mothers to eat excessively should be abandoned.

Similarly, if healthy breastfeeding women wish to undertake strenuous exercise (from 6 to 8 weeks after birth), or to lose weight (500–1000 g/week), they can be assured that neither the quality nor the quantity of their milk will be affected (Dewey et al 1994, Dusdieker et al 1994). Exclusive breastfeeding combined with low fat diet and exercise will result in more effective weight loss than diet and exercise alone (Dewey 1998, Hammer et al 1996).

Milk production is similarly unaffected by fluctuations in the mother’s fluid intake. It has been repeatedly demonstrated that neither a significant decrease (e.g. Dearlove & Dearlove 1981) nor a significant increase (e.g. Morse et al 1992) in maternal fluid intake has any effect on milk production or the baby’s weight.

Properties and components of breastmilk

Human milk varies in its composition:

The most dramatic change in the composition of milk occurs during the course of a feed (Hall 1979). At the beginning of the feed the baby receives a high volume of relatively low fat milk (the foremilk). As the feed progresses, the volume of milk decreases but the proportion of fat in the milk increases, sometimes to as much as five times the initial value (the hindmilk) (Jackson et al 1987). The baby’s ability to obtain this fat-rich milk is not determined by the length of time he spends at the breast, but by the quality of his attachment to the breast. The baby needs to be well attached so that he can use his tongue to maximum effect, stripping the milk from the breast, rather than relying solely on his mother’s milk ejection reflex. A poorly attached baby may have difficulty in obtaining enough fat to meet his needs, and may resort to feeding very frequently in order to obtain sufficient calories from low fat feeds. A well-attached baby may, on the other hand, obtain all he needs in a very short time.

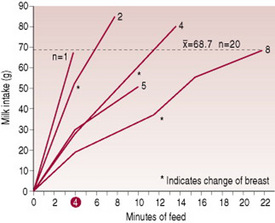

The length of the feed, provided that the baby is well attached, is thus determined by the rate of milk transfer from mother to baby. If milk transfer occurs at a high rate, feeds will be relatively short; if it occurs slowly, feeds will be longer (Woolridge et al 1982) (Fig. 41.3). Milk transfer seems to be more efficient in a second lactation than in a first (Ingram et al 2001).

Figure 41.3 Pattern of milk intake at a feed for 20 6-day-old babies.

(From Woolridge et al 1982, with permission.)

Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life

Human milk is species specific. The 54th World Health Assembly, which met in Geneva in May 2001, affirmed the importance of exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months. The new resolution (Agenda Item 13.1, Infant and young child nutrition, A54/45 in para. 2(4).) urged member states to:

support exclusive breastfeeding for six months as a global public health recommendation taking into account the findings of the WHO Expert Technical Consultation on optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding and to provide safe and appropriate complementary foods, with continued breastfeeding for up to two years or beyond …

It has been known for some time that exclusively breastfed babies who consume enough breastmilk to satisfy their energy needs will easily meet their fluid requirements, even in hot dry climates (Ashraf et al 1993, Sachdev et al 1991).

Extra water will do nothing to speed the resolution of physiological jaundice, should it occur (Carvahlo et al 1981, Nicoll et al 1982). The only consistent effect of giving additional fluids to breastfed infants is to reduce the time for which they are breastfed (Fenstein et al 1986, White et al 1992).

Fats and fatty acids

For the human infant, with his unique and rapidly growing brain, it is the fat and not the protein in human milk that has particular significance.

Some 98% of the lipid in human milk is in the form of triglycerides: three fatty acids linked to a single molecule of glycerol. Over 100 fatty acids have so far been identified, about 46% being saturated fat and 54% unsaturated fat. There has been an explosion of interest in recent years in the unsaturated fatty acid content of human milk, particularly in the long chain polyunsaturated variety (LC-PUFAs for short), because of their role in brain growth and myelination. Two of them, arachidonic acid (AA) and docosahexanoic acid (DHA) appear to play an important role in the development of the retina and visual cortex of the newborn. Fat also provides the baby with >50% of his calorific requirements (Helsing & Savage King 1982). It is utilized very rapidly because the milk itself contains the enzyme (bile-salt-stimulated lipase) needed for fat digestion, but in a form which becomes active only when it reaches the infant’s intestine. Pancreatic lipase is not plentiful in the newborn, so a baby who is not fed human milk is less able to digest fat.

Carbohydrate

The carbohydrate component of human milk is provided chiefly by lactose, which provides the baby with about 40% of his calorific requirements. Lactose is converted into galactose and glucose by the action of the enzyme lactase and these sugars provide energy to the rapidly growing brain. Lactose enhances the absorption of calcium and also promotes the growth of lactobacilli, which increase intestinal acidity thus reducing the growth of pathogenic organisms.

Protein

Human milk contains less protein than any other mammalian milk (Akre 1989a) and this accounts in part for its more ‘transparent’ appearance. Human milk is whey dominant (the whey being mainly α-lactalbumin) and forms soft, flocculent curds when acidified in the stomach.

Allergic problems occur less frequently in breastfed babies than in artificially fed babies. This may be because the infant’s intestinal mucosa is permeable to proteins before the age of 6–9 months and proteins in cow’s milk can act as allergens. In particular, bovine β-lactoglobulin, which has no human milk protein counterpart, is capable of producing antigenic responses in atopic infants (Adler & Warner 1991, Bahna 1987).

Occasionally a baby may react adversely to substances in his mother’s milk that come from her diet. However, this is rare and can be resolved by the mother identifying and avoiding the foods that cause the trouble so that she may continue to breastfeed.

Another bovine whey protein, bovine serum albumin, has been implicated as the trigger for the development of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (Paronen et al 2000, Vaarala et al 1999).

Vitamins

All the vitamins required for good nutrition and health are supplied in breastmilk, and although the actual amounts vary from mother to mother, none of the normal variations pose any risk to the infant (Worthington-Roberts 1993).

Fat-soluble vitamins

Vitamin A

Vitamin A is present in human milk as retinol, retinyl esters and beta carotene. Colostrum contains twice the amount present in mature human milk, and it is this that gives colostrum its yellow colour. Bile-salt-stimulated lipase (present in human milk – see fatty acids, above) assists the hydrolysation of the retinyl esters and may account for the rarity of vitamin A deficiency in breastfed babies in affluent societies (Fredrikzon et al 1978).

Vitamin D

Vitamin D plays an essential role in the metabolism of calcium and phosphorus in the body and prevents osteomalacia in adults and rickets in children, and is not strictly a vitamin, but a hormone triggered by ultraviolet light. It is the name given to two fat-soluble compounds, calciferol (vitamin D2) and cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). A plentiful supply of 7-dehydrocholesterol, the precursor of vitamin D3, exists in human skin, and needs only to be activated by sufficient ultraviolet light (<30 min of summer sunlight a day) to become fully potent.

For light-skinned babies, exposure to sunlight for 30 min/week wearing only a nappy, or 2 hrs/week fully clothed but without a hat, will keep vitamin D requirements within the lower limits of the normal range (Specker et al 1985).

However, the latitude and strength of the sunlight is important; research done in the 1970s in Scandinavia and the UK found that photo-conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol (i.e. sunlight triggering the hormones to do their work) occurred only between March and October, with a maximum in June and July. Those living in regions where exposure to the sun is low have always been at risk for vitamin D deficiency (Garza & Ramussen 2000).

Pregnant women need to ensure that their vitamin D levels are high enough to supply sufficient amounts via the placenta to assure adequate stores in the baby’s liver at birth, as the concentration of vitamin D in human milk is low.

It has been suggested (G. Palmer, pers comm) that 9 months is the perfect length for a pregnancy because at some stage the mother should ordinarily have been exposed to adequate sunlight.

In the past, if a baby was born in March the mother’s vitamin D levels might be starting to dip by the time of the birth, but the spring sunshine would soon cause the baby’s levels to rise. If the baby was born in October he/she might have been well provided for by his mother’s (summer) sunlight exposure, but might be at slight risk by March. The introduction of other foods (6 months later) combined with spring sunshine, would raise the baby’s levels.

However, in recent years, social mobility, cultural considerations, and concerns over skin cancer from sunlight have increased the risk of vitamin D deficiency by reducing the skin’s exposure to sunlight. In the UK, this is of particular concern in women and infants of Asian and Afro-Caribbean ethnic origin (Gregory et al 2000, Leaf 2007).

Maternal vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy has been linked to maternal osteomalacia as well as reduced birthweight, neonatal hypocalcaemia and tetany (Cockburn et al 1980).

Vitamin D is fat soluble, and the principal unfortified dietary source is fish liver oils, with butter, eggs and cheese contributing much smaller amounts. In the UK, only margarine fortification (with 2800–3520 IU/kg of vitamin D) is compulsory. This began in 1940 when dietary sources were in short supply (Kendell & Adams 2002). (In other countries, vitamin D fortification of various other foods is either compulsory or permitted.)

Based on the Expert Group on Vitamins and Minerals EVM (2003) report, the Food Standards Agency currently recommends an intake for pregnant women of 10 μg (0.01 mg) (equivalent to 400 IU) of vitamin D each day.

In 2003, the American Academy of Pediatrics published new guidelines on preventing vitamin D deficiency in infants and children, and recommended an intake of 200 IU vitamin D/day, (5 μg) for all infants and children (Gartner & Greer 2003).

In line with these two recommendations, the New UK Healthy Start programme (see below) now provides vitamin D (and A and C) supplements free of charge for all eligible pregnant women and children.

The review of the evidence undertaken and published by NICE in 2008, contains recommendations as follows:

Toxicity

Neither sunlight nor vitamin D consumed from the diet is likely to cause toxicity, unless large amounts of cod liver oil are consumed. It is much more likely to occur from high intakes of vitamin D in supplements, or possibly fortified foods.

Excessive vitamin D intake may lead to hypercalcaemia and hypercalciuria. Vitamin D promotes the absorption of calcium and the resorption of bone; in excess this would result in the deposition of calcium in soft tissues, diffuse demineralization of bones and irreversible renal and cardiovascular toxicity. Patients with sarcoidosis are abnormally sensitive to vitamin D, due to uncontrolled conversion of the vitamin to its active form in the granulomatous tissue. Although the condition is uncommon, it would be a potential hazard if affected individuals were to take vitamin D in the form of supplements or possibly fortified foods.

In the general population, a daily supplement of 0.025 mg vitamin D (1000 IU) would not be expected to cause adverse effects. This is equivalent to 0.0004 mg/kg per day for a 60 kg adult (EVM 2003).

Vitamin E

Although vitamin E is present in human milk, its role is uncertain. It appears to prevent the oxidization of polyunsaturated fatty acids and may prevent certain types of anaemia to which preterm infants are susceptible.

Vitamin K

Vitamin K (83% of which is present as α-tocopherol), is essential for the synthesis of blood-clotting factors. It is present in human milk and absorbed efficiently. Because it is fat soluble, it is present in greater concentrations in colostrum and in the high fat hindmilk (Kries et al 1987), although the increased volume of milk as lactation progresses means that the infant obtains twice as much vitamin K from mature milk as he does from colostrum (Canfield et al 1991).

It has been suggested that by 2 weeks of age the breastfed baby’s gut flora should be synthesizing adequate amounts of vitamin K (Akre 1989b), although others maintain that the diet is the only source of vitamin K in humans (Kries et al 1987).

Babies who are at risk of haemorrhage, such as the pre-term and those delivered precipitately or instrumentally, commonly receive a prophylactic dose, usually by intramuscular injection. Many paediatricians currently consider that all breastfed babies should receive vitamin K soon after birth, although there is little evidence to guide practice. Doubt currently exists as to how much and how often breastfed babies might require additional vitamin K (see Ch. 45). Research undertaken by Greer (1997) has confirmed earlier work suggesting that marked increases in breastmilk concentrations of vitamin K (and corresponding increases in infant blood levels) can be obtained by giving mothers oral vitamin K preparations, although whether this is necessary (since prothrombin times in infants were not altered) is still open to question. Policies in units throughout the UK vary widely, and there is no clear consensus on which babies are at increased risk of bleeding due to vitamin K deficiency (Ansell et al 2001).

Water-soluble vitamins

Unless the mother’s diet is seriously deficient, breast-milk will contain adequate levels of all the vitamins. Since most vitamins are fairly widely distributed in foods, a diet significantly deficient in one vitamin will be deficient in others as well. Thus an improved diet will be more beneficial than artificial supplements. With some vitamins, particularly vitamin C, a plateau may be reached where increased maternal intake has no further impact on breastmilk composition.

Minerals and trace elements

Iron

Normal term babies are usually born with a high haemoglobin level (16–22 g/dL), which decreases rapidly after birth. The iron recovered from haemoglobin breakdown is re-utilized. They also have ample iron stores, sufficient for at least 4–6 months. Although the amounts of iron are less than those found in formulae, the bioavailability of iron in breastmilk is very much higher: 70% of the iron in breastmilk is absorbed, whereas only 10% is absorbed from a formula (Saarinen & Siimes 1979). The difference is due to a complex series of interactions that take place within the gut. Babies who are fed fresh cow’s milk or a formula may become anaemic because of micro- haemorrhages of the bowel.

Zinc

A deficiency of this essential trace mineral may result in failure to thrive and typical skin lesions. Although there is more zinc present in formulae than in human milk, the bioavailability is greater in human milk. Breastfed babies maintain high plasma zinc values compared with formula-fed infants, even when the concentration of zinc is three times that of human milk (Sandstrom et al 1983). Pre-term babies may need zinc supplements.

Calcium

Calcium is more efficiently absorbed from human milk than from breastmilk substitutes because of the higher calcium: phosphorus ratio of human milk. Infant formulas, which are based on cow’s milk, inevitably have a higher phosphorus content than human milk, and this has been reported to increase the risk of neonatal tetany (Specker et al 1991).

Other minerals

Human milk has significantly lower levels of calcium, phosphorus, sodium and potassium than formulae. Copper, cobalt and selenium are present at higher levels. The higher bioavailability of these minerals and trace elements ensures that the infant’s needs are met while also imposing a lower solute load on the neonatal kidney than do breastmilk substitutes.

Anti-infective factors

Leucocytes

During the first 10 days, there are more white cells/mL in breastmilk than there are in blood. Macrophages and neutrophils are among the most common leucocytes in human milk and they surround and destroy harmful bacteria by their phagocytic activity.

Immunoglobulins

Five types of immunoglobulin have been identified in human milk: IgA, IgG, IgE, IgM and IgD. Of these the most important is IgA, which appears to be both synthesized and stored in the breast. Although some IgA is absorbed by the infant, much of it is not. Instead it ‘paints’ the intestinal epithelium and protects the mucosal surfaces against entry of pathogenic bacteria and enteroviruses. It affords protection against Escherichia coli, salmonellae, shigellae, streptococci, staphylococci, pneumococci, poliovirus and the rotaviruses.

Lysozyme

Lysozyme kills bacteria by disrupting their cell walls. The concentration of lysozyme increases with prolonged lactation (Hamosh 1998).

Lactoferrin

Lactoferrin binds to enteric iron, thus preventing potentially pathogenic E. coli from obtaining the iron they need for survival. It also has antiviral activity (against HIV, CMV and HSV), by interfering with virus absorption or penetration, or both.

Bifidus factor

Bifidus factor in human milk promotes the growth of Gram-positive bacilli in the gut flora, particularly Lactobacillus bifidus, which discourages the multiplication of pathogens. (Babies who are fed on cow’s-milk-based formulae have more potentially pathogenic bacilli in their gut flora.)

Hormones and growth factors

Epidermal growth factor and insulin-like growth factor stimulate the baby’s digestive tract to mature more quickly and strengthen the barrier properties of the gastrointestinal epithelium. Once the initially leaky membrane lining the gut matures, it is less likely to allow the passage of large molecules, and becomes less vulnerable to micro organisms. The timing of the first feed also has a significant effect on gut permeability, which drops markedly if the first feed takes place soon after birth.

Management of breastfeeding

Antenatal preparation

Breasts and nipples are altered by pregnancy (see Ch. 14). Increased sebum secretion obviates the need for cream to lubricate the nipple. Women who have inverted and non-protractile (flat) nipples often find that they improve spontaneously during pregnancy (Hytten & Baird 1958). If not, help given with attaching the baby to the breast after birth often results in successful breastfeeding. Neither the wearing of Woolwich shells nor Hoffmann’s exercises are of any value (Main Trial Collaborative Group 1994) and should not be recommended, nor should any other un-evaluated commercially available device. Education of the mother is likely to be more use than any physical exercises.

The first feed

The mother should have her baby with her immediately after birth. Early and extended skin contact will ensure the cues that indicate that the baby is ready to feed will not be missed. Early feeding contributes to the success of breastfeeding but the time of the first feed should, to a large extent, depend on the needs of the baby. Some may demonstrate a desire to feed almost as soon as they are born. Other babies may show no interest until they are an hour or so old (Righard & Alade 1990, Widström et al 1987).

The first feed should be supervised by the midwife. If it proceeds without pain and if the baby is allowed to terminate the feed spontaneously, both mother and baby will have been helped to begin the learning process necessary for good breastfeeding in a happy and positive way.

The next feed

All mothers should be offered help with the next feed also. Once the baby is feeding satisfactorily the mother should be told about the cause, and therefore prevention, of sore nipples. She should be urged to seek help if problems do arise. She should be told about the changes that will take place in her breasts during the next few days. Helping mothers to understand that breastfeeding is a learned, not an instinctive, skill will enable them to be patient with themselves and their babies during this time (RCM 2001). Mothers who receive the right help and education at the start will require less support and remedial intervention later.

Positioning the mother

There are two main positions for the mother to adopt while she is breastfeeding. The first is lying on her side and this may be appropriate at different times during her lactation (see Plate 5). If she has had a caesarean section, or if her perineum is very painful, this may be the only position she can tolerate in the first few days after birth. It is likely that she will need assistance in placing the baby at the breast in this position, because she will only have one free hand. When feeding from the lower breast it may be helpful if she raises her body slightly by tucking the end of a pillow under her ribs. Once she can do this unaided she may find this a comfortable and convenient position for night feeds, enabling her to get more sleep.

The second position is sitting up (see Plate 6). In the early days it is particularly important that the mother’s back is upright and at a right angle to her lap. This is not possible if she is sitting in bed with her legs stretched out in front of her, or if she is sitting in a chair with a deep backward-sloping seat and a sloping back.

Both lying on her side and sitting correctly in a chair (with her back and feet supported) enhance the shape of the breast and also allow ample room in which to manoeuvre the baby.

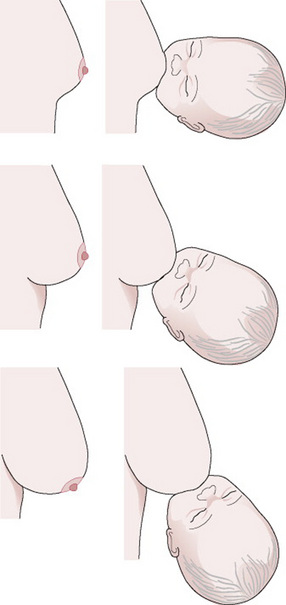

Positioning the baby

The baby’s body should be turned towards the mother’s body (Fig. 41.4) so that he is coming up to her breast at the same angle as her breast is coming down to him. Thus the more the mother’s breast points down, the more on his back he needs to be (Fig. 41.5). (The advice to have the baby tummy to tummy may be mistakenly taken to imply that the baby should always be lying on his side; taking account of the ‘angle of the dangle’ might be more useful). If the baby’s nose is opposite his mother’s nipple before he is brought to the breast and his neck is slightly extended, the baby’s mouth will be in the correct relationship to the nipple (Fig. 41.6).

Figure 41.5 Baby’s body in relation to the mother’s body, depending on the angle of the breast.

(From an original drawing by Hilary English.)

Figure 41.6 The baby’s mouth opposite the nipple, the neck slightly extended.

(From an original drawing by Jenny Inch.)

Attaching the baby to the breast

The baby should be supported across his shoulders, so that the slight extension of his neck can be maintained. His head may be supported by the extended fingers of the supporting hand (see Plate 7) or on his mother’s forearm (see Plate 8). It may be helpful to wrap the baby in a small sheet (Vancouver wrap) so that his hands are by his sides (see Plate 9).

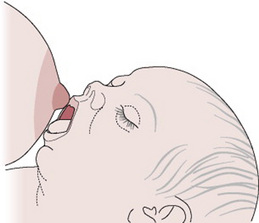

If the baby’s mouth is moved gently but persistently against his mother’s nipple he will open his mouth wide (see Plate 10). As he gapes (drops his lower jaw and darts his tongue down and forward) he needs to be moved quickly to the breast. The intention is to aim the bottom lip as far away from the base of the nipple as is possible. This allows the baby to draw breast tissue as well the nipple into his mouth with his tongue (see Plate 11). If correctly attached, the baby will have formed a ‘teat’ from the breast and the nipple (Fig. 41.7) (Woolridge 1986). The nipple should extend almost as far as the junction of the hard and soft palate. Contact with the hard palate triggers the sucking reflex. The baby’s lower jaw moves up and down, following the action of the tongue. If the baby is well attached, minimal suction is required to hold the ‘teat’ within the oral cavity and the tongue can then apply rhythmical cycles of compression and relaxation so that milk is removed from the ducts. Although the mother may be startled by the physical sensation, she should not experience pain.

Figure 41.7 The baby has formed a ‘teat’ from the breast and the nipple, which causes the nipple to extend back as far as the junction of the hard and soft palates. The lactiferous ducts are within the baby’s mouth. A generous portion of areola is covered by the bottom lip.

(Reproduced from Woolridge 1986, with permission.)

The baby feeds from the breast rather than from the nipple and the mother should guide her baby towards her breast without distorting its shape. The baby’s neck should be slightly extended and the chin should be in contact with the breast. If the baby approaches the breast as illustrated in Figure 41.6, a generous portion of areola will be taken in by the lower jaw, but it is positively unhelpful to urge the mother to try to get ‘the whole of the areola’ in the baby’s mouth.

The role of the midwife

The midwife’s role during the first few feeds is two-fold. First, she must ensure that the baby is adequately fed at the breast. Second, she must help the mother to develop the necessary skills so that she is able to feed her baby by herself. Women who have not breastfed before, need encouragement and reassurance (emotional support), they need to be taught the fundamentals of good attachment so that feeding is pain free (practical support) and they need to receive factual information about breastfeeding (informational support) in small, manageable chunks.

Some mothers will need more teaching and support than others.

Hands-on help from the midwife

Pragmatically, it may be necessary for the midwife to help attach the baby to the breast for several feeds. In this case, she should think of her own comfort, as well as that of the mother and her baby. She will put less strain on her own back if she kneels (on a foam mat) beside the mother, rather than bending over her (see Plate 12).

She should also consider which hand guides the baby most skillfully. For example, a right-handed midwife who is helping a mother who is lying on her left side will attach the baby to the left breast with her right hand. Instead of asking the mother to turn on her right side (so that she can feed from the right breast), the midwife could raise up the baby on a pillow and attach him to the right breast, again using her right hand. Alternatively, if the mother is sitting up, she could consider placing the baby under the mother’s arm on the right side, so that she can again use her right hand. (Some midwives feel more comfortable if they stand behind the mother.)

Once the baby has fed efficiently he is more likely to do so again and it is from this point that the mother can begin to learn how to feed her baby by herself.

If the midwife needs to give hands-on help to the mother, she should also explain what she is doing, and why, so that the mother learns from the encounter. If no explanation is given, or the midwife just attaches the baby and leaves the mother, the mother may have help with every feed and yet still be unable to attach the baby to her breast herself days later.

Feeding behaviour

When the baby first goes to the breast he feeds vigorously, with few pauses. As the feed progresses, pausing occurs more frequently and lasts longer. Pausing is an integral part of the baby’s feeding rhythm and should not be interrupted. The midwife should simply encourage the mother to allow the baby to pace the feed. The change in the pattern probably relates to milk flow. The foremilk, which he obtains first, is more generous in quantity but lower in fat than the hindmilk delivered at the end, which is thus higher in calories (Woolridge & Fisher 1988). If the baby receives an excessive quantity of foremilk (owing to either poor attachment or premature breast switching, see below), it may result in increased gut fermentation causing colic, flatus and explosive stools (Woolridge & Fisher 1988).

This is the commonest cause of colic in breastfed babies and is resolved by improving attachment. Simethicone preparations, which are often prescribed for this condition, have been shown to be of no value (Metcalf et al 1994).

Finishing the first breast and finishing a feed

The baby will release the breast when he has had sufficient milk from it. His ability to know this may be controlled either by the calories he has received or by the change in the volume available. The baby should be offered the second breast after he has had the opportunity to bring up wind. Sometimes in the early days the baby will not need to feed from the second breast.

The baby should not be deliberately removed from the breast before he releases it spontaneously, unless he is causing pain (in which case he should be reattached, if he is still willing). Taking the baby off the first breast before he has finished may cause two problems. First, the baby is deprived of the high calorie hindmilk; second, if adequate milk removal has not taken place, milk stasis may occur ultimately leading to mastitis or a reduced milk production, or both. Provided that the baby starts each feed on alternate sides, both breasts will be used equally. If the baby does not release the breast or will not settle after a feed, the most likely reason is that he had not been correctly attached to the breast and was therefore unable to remove the milk efficiently.

Other reasons for baby coming off the breast are:

There is no justification for imposing either one breast per feed or alternatively both breasts per feed as a feeding regimen.

Timing and frequency of feeds

A well, term baby knows better than anyone else how often and for how long he needs to be fed. This is described as baby-led feeding, which is a term preferable to ‘demand feeding’.

It is not unusual in the 1st day or so for the baby to feed infrequently, and have 6–8 hrs gaps between good feeds, each of which may be quite long (Inch & Garforth 1989, Waldenström & Swensen 1991). This is normal and provides the mother with the opportunity to sleep if she needs to. As the milk volume increases, the feeds tend to become more frequent and a little shorter. It is unusual for a baby to feed less often than six times in 24 hrs from the 3rd day, and most babies ask for between six and eight feeds per 24 hrs by the time they are 1 week old. Babies who feed infrequently may be consuming less milk than they need, or they may be unwell, or both. Babies who feed very often (10–12 feeds in 24 hrs after the 1st week) may be poorly attached. The feeding technique and the weight should be monitored. However, individual mother–baby pairs develop their own unique pattern of feeding and, provided the baby is thriving and the mother is happy, there is no need to change it.

Volume of the feed

Well-grown term infants are born with good glycogen reserves and high levels of antidiuretic hormone. Consequently they do not need large volumes of milk or colostrum any sooner than these are made available physiologically. In the first 24 hrs, the baby takes an average of 7 mL per feed; in the second 24 hrs, this increases to 14 mL per feed (RCM 2001).

No precise information is available on the actual volume of breastmilk an individual baby requires in order to grow satisfactorily. Previous recommendations (150 mL/kg) were based on the requirements of artificially fed babies, and these can therefore be used only as a guideline.

Weight loss and weight gain

Most newborn babies lose some weight during their 1st week of life, and there is a general expectation that the baby will be back to birthweight by 10–14 days. There is less agreement about how great a weight loss is within the bounds of normal or acceptable. Although the figure of 10% is often cited as the upper limit of normal, there is little evidence to support a figure as high as this. Data from nine studies conducted between 1986 and 1999 suggest a normal range of 3–7%; and more recently, normative data on 435 breastfed babies born in a Scottish ‘Baby Friendly’ Hospital, reported a median maximum weight loss of 6.6% (Macdonald et al 2003).

Over the first 4 days of life, the stools change from black meconium to the characteristic yellow stool of the baby, fed on breastmilk. A stool that is still ‘changing’ at 96 hrs of life could indicate that further attention needs to be paid to the way the mother is feeding her baby (see Plate 15).

If the baby is difficult to attach, because he is sleepy or because the breast tissue is inelastic, the same principles ought to apply to this situation as when the baby and mother are separated by virtue of illness or prematurity – namely to teach the mother how to hand express in order to get lactation established. If this is not done, the mother’s lactation will be in arrears of her baby’s needs when he starts to ask for larger volumes on the 3rd/4th day.

If the mother is still not able to feed effectively as the end of the 1st week approaches, she should make expressing her milk her priority, using either her hands or an effective breast pump, so that her lactation is secured and her baby is fed. Ongoing help with improving breastfeeding will also be needed.

Expressing breastmilk

Although all breastfeeding mothers should know how to hand express milk, routine expression of the breasts should not be part of the normal management of lactation, even for mothers who have delivered by caesarean section (Chapman et al 2001).

Provided that no limitation is placed on either feed frequency or duration and the baby is correctly attached, the volume of milk produced will be in step with the requirements of the baby. This will prevent the occurrence of problems (such as engorgement) that would require artificial removal of milk.

The situations where expressing is appropriate are:

Manual expression of milk

Manual expression has several advantages over mechanical pumping and should be taught to all mothers. It is usually the most efficient method of obtaining colostrum. Some mothers will find hand expressing superior to any breast pump, as illustrated in the new Joint Dept of Health/UNICEF leaflet ‘Off to the best start’. There are now a variety of useful teaching aids available; models, videos and leaflets (contact UNICEF-UK Baby Friendly Initiative, see Useful addresses, below).

Expressing with a breast pump

If it is possible and practical, the mother should be able to experiment with a variety of breast pumps, so that she can discover what will suit her best (Auerbach & Walker 1994). Not all pumps work well for all women.

Hand pumps

Manually controlled

Most manually operated pumps are not efficient enough to allow initiation of full lactation but they can be useful when expressing is necessary in established lactation. It is helpful to mothers to explain that the pumps function most efficiently if the vacuum phase is considerably longer than the release phase.

Electrically controlled

Some pumps provide a regular vacuum and release cycle, with variability in the strength of the suction. Some vary the frequency of the cycle as well. Double pumping is possible with most models, and this has repeatedly been shown to be of benefit, either by reducing the time for which the mother needs to pump at each session to obtain the available milk (Groh-Wargo et al 1995, Hill et al 1999), or by increasing the volume of milk obtained, for mothers of both term (Auerbach 1990) and pre-term (Jones et al 2001) babies.

How much and how often?

The mothers of pre-term babies who begin pumping as soon as possible after birth and pump a minimum of six times per 24 hrs are more likely to sustain lactation at adequate levels than those who delay pumping or pump less frequently, or both. The earlier the mother is able to express good volumes of milk (per 24 hrs), the better the outlook for continued adequate milk production.

Breast massage (Jones et al 2001) and kangaroo care (Hill et al 1999) have also been positively associated with enhanced milk production.

No time limit should be set for the length of each expressing session. The mother should be guided by the milk flow, not the clock. Expressing should continue until milk flow slows, followed by a short break, and each breast should be expressed twice (either separately (sequential pumping) or together (double pumping)). When milk flow slows for the second time the session should end. Frequent pumping sessions are more likely to have the desired effect than infrequent marathons.

Inadequate milk volume, followed by declining production, are common problems for the mothers of pre-term babies who are expressing their milk. Prevention, by the midwife discussing with the mother the importance of early initiation, the appropriate use of the (correct size of) equipment and stressing the importance of the frequency (rather than regularity) of expression, is preferable to trying to rescue failing lactation pharmacologically.

Storage of mother’s own breastmilk

NICE (2008) advises that expressed milk can be stored for:

They also advise that mothers who wish to store expressed breastmilk for <5 days should do so in the fridge, as this preserves its properties more effectively than freezing.

Care of the breasts

Daily washing is all that is necessary for breast hygiene. The normal skin flora are beneficial to the baby. Brassieres may be worn in order to provide comfortable support and are useful if the breasts leak and breast pads (or breast shells) are used.

Breast problems

Sore and damaged nipples

The cause is almost always trauma from the baby’s mouth and tongue, which results from incorrect attachment of the baby to the breast. Correcting this will provide immediate relief from pain and will also allow rapid healing to take place. Epithelial growth factor, contained in fresh human milk and saliva, may aid this process.

‘Resting’ the nipple also enables healing to take place but makes the continuation of lactation much more complicated because it is necessary to express the milk and to use some other means of feeding it to the baby.

Nipple shields should be used with extreme caution, and never before the mother has begun to lactate. They may make feeding less painful, but often they do not. Their use does not enable the mother to learn how to feed her baby correctly, and their longer term use may result in reduced milk transfer from mother to baby. This in turn may result in either mastitis in the mother (reduced milk removal), or slow weight gain or prolonged feeds in the baby (reduced milk transfer), or both. If mothers choose to use them, they should be advised to seek help with learning to attach the baby comfortably without a nipple shield as soon as practicable.

Other causes of soreness

Infection with Candida albicans (thrush) can occur, although it is not common during the 1st week. The sudden development of pain when the mother has had a period of trouble-free feeding is suggestive of thrush. The nipple and areola are often inflamed and shiny, and pain typically persists throughout the feed. The baby may show signs of oral or anal thrush. Both mother and baby should receive concurrent fungicidal treatment (such as miconazole, see Ch. 49) and it may take several days for the pain in the nipple to disappear.

Dermatitis

Sensitivity may develop to topical applications such as creams, ointments or sprays (including those used to treat thrush).

Anatomical variations

Long nipples

Long nipples can lead to poor feeding because the baby is able to latch on to the nipple without drawing breast tissue into his mouth.

Short nipples

Short nipples should not cause problems as the baby has to form a teat from both the breast and nipple.

Abnormally large nipples

If the baby is small, his mouth may not be able to get beyond the nipple and onto the breast. Lactation could be initiated by expressing, either by hand or by pump, provided that the nipple fits into the breast cup. As the baby grows and the breast and nipple become more protractile, breastfeeding may become possible.

Problems with breastfeeding

Engorgement

This condition occurs around the 3rd or 4th day postpartum. The breasts are hard (often oedematous), painful and sometimes flushed. The mother may be pyrexial. Engorgement is usually an indication that the baby is not in step with the stage of lactation. Engorgement may occur if feeds are delayed or restricted or if the baby is unable to feed efficiently because he is not correctly attached to the breast.

Management should be aimed at enabling the baby to feed well (Box 41.1). In severe cases the only solution will be the gentle use of a pump. This will reduce the tension in the breast and will not cause excessive milk production. The mother’s fluid intake should not be restricted, as this has no effect on milk production.

Box 41.1 Babies who are difficult to attach

Inelastic breast tissue, overfull or engorged breasts or deeply inverted nipples may present the baby with more of a challenge.

When attachment is difficult, the priorities should be to ensure that the baby is adequately fed on his mother’s milk, and to work on making the breast tissue more elastic (both of which can be facilitated by hand or electrical expressing). Attaching the baby to the breast directly can come later.

Deep breast pain

In most cases, this responds to improvement in breastfeeding technique and is thus likely to be due to raised intraductal pressure caused by inefficient milk removal. Although it may occur during the feed it typically occurs afterwards, and thus can be distinguished from the sensation of the let-down reflex, which some mothers experience as a fleeting pain. Very rarely, deep breast pain may be the result of ductal thrush infection.

Mastitis

Mastitis means inflammation of the breast. In the majority of cases, it is the result of milk stasis, not infection, although infection may supervene (Thomsen et al 1984). Typically, one or more adjacent segments are inflamed (as a result of milk being forced into the connective tissue of the breast) and appear as a wedge-shaped area of redness and swelling. If milk is also forced back into the bloodstream, the woman’s pulse and temperature may rise and in some cases flu-like symptoms, including shivering attacks or rigors, may occur. (The presence or absence of systemic symptoms does not help to distinguish infectious from non-infectious mastitis; WHO 2000.)

Non-infective (acute intramammary) mastitis

Non-infective (acute intramammary) mastitis results from milk stasis. It may occur during the early days as the result of unresolved engorgement or at any time when poor feeding technique results in the milk from one or more segments of the breast not being efficiently removed by the baby. It occurs much more frequently in the breast that is opposite the mother’s preferred side for holding her baby (Inch & Fisher 1995). Pressure from fingers or clothing has been blamed for causing the condition, without any supporting evidence. It is extremely important that breastfeeding from the affected breast continues, otherwise milk stasis will increase further and provide ideal conditions for pathogenic bacteria to replicate. An infective condition may then arise which could, if untreated, lead to abscess formation.

Where supervision is available, 12–24 hrs could be allowed to elapse to ascertain whether the mastitis can be resolved by helping the mother to improve her feeding technique and encouraging her to allow the baby to finish the first breast first. If supervision is not available, or if no improvement occurs during that period, antibiotics (e.g. cephalexin, flucloxacillin or erythromycin) should be given prophylactically (RCM 2001, WHO 2000).

Infective mastitis

The main cause of superficial breast infection is damage to the epithelium, which allows bacteria to enter the underlying tissues. The damage usually results from incorrect attachment of the baby to the breast, which has caused trauma to the nipple. The mother therefore urgently needs help to improve her technique, as well as the appropriate antibiotic. Multiplication of bacteria may be enhanced by the use of breast pads or shells. In spite of antibiotic therapy, abscess formation may occur. Infection may also enter the breast via the milk ducts if milk stasis remains unresolved.

Breast abscess

Here a fluctuant swelling develops in a previously inflamed area. Pus may be discharged from the nipple. Simple needle aspiration may be effective, or incision and drainage may be necessary (Dixon 1988). It may not be possible to feed from the affected breast for a few days; however, milk removal should continue and breastfeeding should recommence as soon as practicable because this has been shown to reduce the chances of further abscess formation (WHO 2000). A sinus that drains milk may form, but it is likely to heal in time.

Blocked ducts

Lumpy areas in the breast are not uncommon; the mother is usually feeling distended glandular tissue. If they become very firm and tender (and sometimes flushed) they are often described as ‘blocked ducts’. This description carries with it the image of a physical obstruction within the lumen of the duct – like ‘a golf ball in a hosepipe’. This is very rarely the cause of the symptoms. It is much more likely to be the case that milk removal has been somewhat uneven (as a consequence of less than optimal attachment) and that the secreted milk is now trying to occupy more space than is actually available – thus distending the alveoli. It may subsequently be forced out into the connective tissue of the breast where it causes inflammation. The inflammatory process then narrows the lumen of the duct by exerting pressure on it from the outside as the tissue swells. A more helpful image might therefore be that of ‘compressing the hosepipe’. This is, effectively, mastitis or incipient mastitis. Consequently, the solution is to improve milk removal by improved attachment, and possibly milk expression as well and to treat the accompanying pain and inflammation. Massage, which is often advocated to clear the imagined ‘blockage’, may make matters worse by forcing more milk into the surrounding tissue.

White spots

Very occasionally, a ductal opening in the tip of the nipple may become obstructed by a white granule or by epithelial overgrowth.

White granules

White granules appear to be caused by the aggregation and fusion of casein micelles to which further materials become added. This hardened lump may obstruct a milk duct as it slowly makes its way down to the nipple, where it may be removed by the baby during a feed, or expressed manually (WHO 2000).

Epithelial overgrowth

Epithelial overgrowth seems to be the more common cause of a physical obstruction. A white blister is evident on the surface of the nipple, and it effectively closes off one of the exit points in the nipple, which leads from one or more milk-producing sections of the breast.

This may also be resolved by the baby feeding. Alternatively, after the baby has fed and the skin is softened, it may be removed with a clean fingernail, a rough flannel, or a sterile needle.

True blockages of this sort tend to recur, but once the woman understands how to deal with them, the progression to mastitis can be avoided.

Feeding difficulties due to the baby

Cleft lip

Provided that the palate is intact, the presence of a cleft in the lip should not interfere with breastfeeding because the vacuum that is necessary to enable the baby to attach to the breast is created between the tongue and the hard palate, not the breast and the lips.

Cleft palate

Because of the cleft, the baby is unable to create a vacuum and thus form a teat out of the breast and nipple. The use of an orthodontic plate is unlikely to help because the baby is unable to feel the breast against the hard palate and this is necessary to elicit the sucking response. There is no reason why the mother should be discouraged from putting the baby to the breast – for comfort, pleasure or food – provided that she is aware of the above and appreciates that it is likely that she will need to give her baby her expressed milk as well.

Many mothers have expressed their milk and used various techniques to feed it to their babies. A device called the Haberman feeder has proved useful. (These are now provided free of charge by CLAPA; see Useful addresses, below). Some mothers have maintained their lactation until the baby has had a surgical repair and have then succeeded in breastfeeding.

Tongue tie

If the baby cannot extend his tongue over his lower gum he is unlikely to be able to draw the breast deeply into his mouth, which he needs to do to feed effectively. Sometimes this is because the tongue is short, and sometimes this is because the frenulum, the whitish strip of tissue that attaches the tongue to the floor of the mouth, is preventing it. As the baby lifts his tongue, the tip becomes heart shaped as the frenulum pulls on it. Previous empirical evidence, which suggested that tongue-tie can interfere with breastfeeding, and of the value of frenotomy (surgical release of the frenulum, which takes a few seconds and is usually bloodless and painless), is now supported by evidence from ultrasound studies (Ramsay 2005) and clinical trials (Dollberg et al 2006, Hogan et al 2005).

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE 2005) concluded that the division of tongue-tie to help babies with this condition to breastfeed was safe enough and worked well enough for use in the NHS.

Blocked nose

Babies normally breathe through their noses. If there is an obstruction, they have great difficulty with feeding because they have to interrupt the process in order to breathe. A blockage caused by mucus may be relieved with a twist of damp cotton wool, or by instilling drops of normal saline before a feed (Bollag et al 1984).

Down syndrome

Down syndrome babies can be successfully breastfed, although extra help and encouragement may be necessary initially.

Prematurity

Pre-term infants who are sufficiently mature to have developed sucking and swallowing reflexes may successfully breastfeed. Breastfeeding is less tiring than bottle feeding for the pre-term baby (Meier & Cranston-Anderson 1987). If the reflexes are not strongly developed, the baby may tire before the feed is complete and complementary tube feeding may be necessary.

Babies who are too immature to breastfeed may be able to cup feed, as an alternative to being tube-fed (Lang et al 1994). Less mature babies who are unable to suck or swallow at all will be dependent on artificial methods such as tube-feeding and intravenous alimentation.

Contraindications to breastfeeding

Medications (see Ch. 49)

Breastfeeding may have to be suspended temporarily following the administration of certain drugs or following diagnostic techniques.

Most regions have drug centres where advice may be sought about the safety of drugs for lactating women.

Cancer

If the mother has cancer, the treatment she receives will make it impossible to breastfeed without harming the baby. However, if she wishes to, she could express and discard her milk for the duration of the treatment and resume breastfeeding later. If she has had a mastectomy, she may feed successfully from the other breast. She may also be able to breastfeed following a lumpectomy for cancer. She should seek advice from her surgeon.

Breast surgery

Neither breast reduction nor augmentation are an inevitable contraindication to breastfeeding, but much depends on the techniques used. Where possible, advice should be sought from the surgeon. If the nipple has been displaced, the duct system is not likely to be patent. Nickell & Skelton (2005) recommend that if surgery is proposed for a woman who wishes to breastfeed in the future, it may be possible to alter the surgery to preserve the ductal system.

Ultimately, the only way to determine if the breast will function effectively is to test it out by allowing the baby to go to the breast.

Breast injury

Injuries caused by scalding in childhood may cause such severe scarring that breastfeeding is impossible. Burns or other accidents may also cause serious damage.

One breast only

It is perfectly possible to feed a baby well using just one breast. If the mother has only one functioning breast, she should be reassured that in all women each breast works independently. If the baby is offered only one breast, that breast will make enough milk to feed that one baby. There are documented cases of women feeding two babies with just one breast (Nicolls 1997).

HIV infection

HIV may be transmitted in breastmilk. In developed countries, where artificial feeding is relatively safe, the mother may be advised not to breastfeed if she is HIV-positive (see Ch. 23). In countries where artificial feeding is a significant cause of infant mortality, exclusive breastfeeding may be the safer option (Coovadia et al 2007, Coutsoudis et al 1999).

Cessation of lactation

Suppression of lactation

If a mother chooses not to breastfeed or if she has a late miscarriage or stillbirth, lactation will still begin. The woman may experience discomfort for a day or two, but if unstimulated the breasts will naturally cease to produce milk. Very rarely severe discomfort with engorgement occurs. Expressing small amounts of milk once or twice can afford great relief without interfering with the rapid regression of the condition. The mother will be more comfortable if her breasts are supported but it is doubtful if binding the breasts contributes anything towards suppression.

There is no basis on which to advise the mother to restrict her fluid intake or to seek a prescription for a diuretic, which will be equally ineffective (Hodge 1967).

These measures merely add to the woman’s discomfort by making her thirsty. Pharmacological suppression of lactation with dopamine receptor agonists is effective but is not recommended for routine use. Two such drugs, bromocriptine and cabergoline, are currently licensed for this use in the UK, although bromocriptine has now had its USA licence withdrawn.

Discontinuation of breastfeeding

Stopping lactation abruptly once breastfeeding has become established may cause serious problems for the mother. She could develop engorgement or mastitis, or even a breast abscess. She should be encouraged to mimic normal weaning by expressing her breasts but reducing the frequency over several days or possibly weeks. The gradual reduction in the volume of milk removed will result in a corresponding diminution in the production of milk. Eventually she should be encouraged to express only if she feels uncomfortable. Cabergoline might be appropriate following the death of a baby.

Returning to work

If the breastfeeding mother returns to work, her baby will have to be fed in her absence. She may wish her baby to have her own milk at all times and she may express for this purpose.

If the mother finds it difficult to express at work, her baby could receive a formula feed (or ‘solid’ food if over 6 months) while she is away, but breastfeed at all other times. Returning to work does not mean that breastfeeding has to be terminated.

Weaning from the breast

When the mother or the baby decides to stop breastfeeding, feeds should be tailed off gradually. Breastfeeds may be omitted, one at a time, and spaced further apart. Adding supplementary foods should not begin until about 6 months of age. If the mother is using solid food to give the baby ‘tastes’ and the experience of different textures before weaning, these should be given after the breastfeed. Solid foods given before the breastfeed (weaning) will result in the baby taking less milk from the breast and thus less will be produced. Allowing the baby to lead the process of weaning (Rapley 2006) may make the transition much easier.

Complementary and supplementary feeds

Complementary feeds (or ‘top-ups’) are feeds given after a breastfeed. Complementary feeds of breast-milk substitutes (‘formula milk’) should be given as a last resort, not as a quick fix. Any formula at all is enough to sensitize susceptible infants (Host 1991).

In Bolling et al’s study (2005) 33% of babies born in UK hospitals receive breastmilk substitutes while in hospital. The only demonstrable effect of giving complementary feeds in hospitals is to reduce the overall duration of breastfeeding. The mothers of these babies are three times more likely to have given up breastfeeding by the time their baby is 2 weeks old, in comparison with mothers whose babies have received only breastmilk (White et al 1992).

About 10% of newborns are at risk for hypoglycaemia (see Ch.48), and may thus need a higher intake straight from birth than their mothers are able to provide. Where possible this should be human milk – from a human milk bank.

Babies who are well but sleepy (Box 41.2), jaundiced (see Ch. 47), unsettled (Box 41.3), or difficult to attach (Box 41.1), should, if necessary, be given their mother’s own expressed milk in addition to being offered the breast.

Provided that the baby is otherwise well, which will be determined by checking the baby from time to time, there is no evidence that long intervals between feeds have any adverse affect. As few as three feeds in the first 24 hrs of life is within the normal range.

Box 41.3 If the baby is unsettled

An unsettled baby of any age that is crying again soon after he has been fed may not have been well attached.

If complementary feeds are clinically indicated and the mother is unable to express sufficiently, donor milk from a human milk bank could be used. Donors will have been serologically tested for HIV and a negative result received before their milk can be accepted.

If the baby is very young, these additional feeds should be given by oral syringe or cup rather than in a bottle. An oral syringe (or dropper) will reduce wastage and the use of a cup would allow the baby to remain more in control of his intake.

If the problem (such as attachment difficulty) persists, the mother may find it quicker and more efficient to give her expressed milk by bottle. She should be reassured that there is no evidence that the baby will subsequently refuse the breast in these circumstances (Brown et al 1999, Howard et al 2003, Schubiger et al 1997).

Supplementary feeds are feeds given in place of a breastfeed. There can be no justification for their use except in extreme circumstances (such as severe illness or unconsciousness) because each breastfeed missed by the baby will interfere with the establishment of lactation and damage the mother’s confidence.

Human milk banking

In the late 1970s and early 1980s there were over 60 human milk banks in the UK. Most of them closed in the late 1980s, driven by both the fear of HIV transmission and the rising popularity of pre-term formulae. By the early 1990s there were only six milk banks left in the UK.

Slowly this number has risen, encouraged by research that demonstrated the effectiveness of pasteurization as a means of destroying HIV (Eglin & Wilkinson 1987) and the importance of human milk in the prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis (Lucas & Cole 1990); and aided by the formation, in 1998, of the UK Human Milk Banking Association (UKAMB). Banked human milk is used predominantly for pre-term and sick newborns. Occasionally, if there is sufficient, it is used for term babies whose mothers are temporarily unable to meet their babies’ needs with their own (expressed) milk. Mothers who are offered donated milk for their babies should have sufficient information about the collection and screening of human milk to enable them to make an informed choice whether to accept it or not (Box 41.4).

If you are offering a mother donated human milk for her baby for any reason, she might find the information below helpful in deciding whether to accept it.

Feeding the baby – breast or bottle?

Although the majority of women who choose to breastfeed have made this decision very early on, some may not make a final decision until after giving birth. Asking the mother to make a decision antenatally is unhelpful, as it may close the door to further discussion or make her feel that she cannot change her mind, or both.

The subject may be more usefully raised as part of an ongoing discussion in later pregnancy. The midwife should ensure that the mother is aware of the risks of artificial feeding, and knows what the usual practice of the hospital is in relation to skin contact at birth, the management of breastfeeding, rooming-in and so on, so that the woman can make her own preferences known.

Actually seeing a baby being breastfed can strongly influence the decision to breastfeed either positively or negatively, depending on the context (Hoddinott & Pill 1999). This may be of particular relevance to women for whom theoretical knowledge may have less power than embodied knowledge. It has therefore been suggested that women intending to breastfeed might benefit from an antenatal ‘apprenticeship’ with a known breastfeeding mother. Peer group support can influence both the initiation and the continuation of breastfeeding (Fairbank et al 2000), and introducing pregnant women to other mothers with young babies, may be helpful.

Time should be taken during the antenatal period to talk briefly about the day-to-day progress and management of early breastfeeding. The woman should be aware that breastfeeding is a learned skill, that it should not hurt and that she may well receive conflicting advice. This does not mean that she will not need to be taught about the major details of management after the baby is born. The midwife’s responsibility to the woman is to ensure that her choice is ‘fully informed’, rather than to persuade her to breastfeed. She will be unable to do this if the midwife withholds information from her.

The nutritional and immunological consequences of not breastfeeding are seen in population studies, and are to do with relative risks. It is not possible to narrow the risk down to the individual. Nevertheless all pregnant women should be made aware that, compared with a fully breastfed baby, a baby who is bottle-fed from birth is:

Additionally, the pregnant woman should know that she may increase her own risk of pre-menopausal breast cancer, ovarian cancer and osteoporosis if she does not breastfeed (UNICEF and Department of Health 2007).

Artificial feeding

Most breastmilk substitutes (infant formulae) are modified cow’s milk. Until the early 1970s, they consisted of crudely modified dried cow’s milk with added vitamins. Their high solute loads contributed to infantile hypocalcaemia and to hypernatraemic dehydration.

Currently, the minimum and maximum permitted levels of named ingredients, and named prohibited ingredients, are now laid down by statute in the Infant Formula and Follow-on Formula Regulations 1995. However, considerable variations in composition can (and do) exist within the legally permitted ranges. Over 100 changes a year have been made to commercially available breastmilk substitutes (Messenger 1994).

The two main components used are skimmed milk (a by-product of butter manufacture) and whey (a by-product of cheese manufacture). Breastmilk substitutes may contain fats from any source, animal or vegetable (except from sesame and cotton seeds), provided that they do not contain >8% transisomers of fatty acids. The fat source may not always be apparent from reading the label: oleo, for example, is beef fat – unacceptable to Hindus and vegetarians; ‘oils of vegetable origin’ may have come from marine algae. They may also contain, among other things, soya protein, maltodextrin, dried glucose syrup and gelatinized and pre-cooked starch.

Formulae

There are two main types of formula: whey dominant and casein dominant. Both can be used from birth.

Whey-dominant formulae

In these, a small amount of skimmed milk is combined with demineralized whey. The ratio of proteins in the formulae approximates to the ratio of whey to casein found in human milk (60:40). These feeds are more easily digested than the casein-dominant formulae, which will have an effect on gastric emptying times. This leads to feeding patterns that more closely resemble those of breastfed babies.

Casein-dominant formulae

These are also sold as being suitable for use from birth, but they are aimed at mothers whose babies are ‘hungrier’. Although the proportions of the macronutrients (fat, carbohydrate, protein, etc.) are the same as is found in whey-dominant formulae, more of the protein present is in the form of casein (20:80). This forms large relatively indigestible curds in the stomach and is intended to make the baby feel full for longer. This will inevitably place even greater metabolic demands on the infant.

Babies intolerant of standard formulae

Predicting which babies will be prone to allergies is an inexact science. It is estimated that the likelihood of a child being predisposed to allergy is about 20–35% if one parent is affected, 40–60% if both parents are affected and 50–70% if both parents have the same allergy (Brostoff & Gamlin 1998, p 261).

Hydrolysate formula

If breastfeeding is not possible, there are (prescription-only) alternatives that carry less risk of allergy than standard formulas – hydrolysates – some of which are designed to treat an existing allergy, and some of which are designed for preventative use in bottle-fed babies who are at high risk of developing cow’s milk protein allergy (Brostoff & Gamlin 1998, p 232). This is reflected in the British National Formulary prescribing guidelines, which require ‘proven intolerance’ for some hydrolysates, but not for others.

These substances are considerably more expensive than either standard or soya-based formula.

Hydrolysate formula is made of cow’s milk, cornstarch and other foods, which is then treated with digestive enzymes so that the milk proteins are partially broken down. This makes them a good deal less allergenic, although they may still cause problems to babies who are highly allergenic.

Whey hydrolysates

These are made from the whey of cow’s milk (rather than whole milk) and are thought to be potentially more useful for highly allergenic babies. However, NICE guidance (2008) maintains that there is insufficient evidence to suggest that infant formula based on partially or extensively hydrolysed cow’s milk protein helps to prevent allergies.

Amino-acid-based formula, or elemental formula

Amino-acid-based formula, or elemental formula has a completely synthetic protein base, providing the essential and non-essential amino acids, together with fat, maltodextrin, vitamins, minerals and trace elements. (It is very expensive.)

Soya-based formula

Soya-based formula was developed as a response to the emergence of cow’s milk protein intolerance in babies fed cow’s-milk-based formulae and has been covered by the Infant Formula and Follow-on Formula Regulations since 1995. It was subsequently approved for use (by the Advisory Committee for Borderline Substances) as the sole source of nourishment for young infants and could be purchased without prescription.

However in 2004, The Chief Medical Officer recommended that soya-based formulas should only be used in exceptional circumstances to ensure adequate nutrition. For example, they may be given to infants of vegan parents who are not breastfeeding or infants who find alternatives (such as amino acid formulae) unacceptable.

This edict was in response to mounting evidence that soya-based formula’s high phytoestrogen content could pose a risk to the long-term reproductive health of infants (Martyn 1999, Minchin 2001), and the advice from the UK’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN), which questioned the benefit of using any milk protein other than from cows, or any plant protein, including soya (SACN 2003).