Papulosquamous eruptions

Papulosquamous eruptions are raised, scaly and marginated, and include psoriasis, lichen planus and other conditions listed in Table 1. Eczema is not included as it does not usually have a sharp edge. These eruptions are not related aetiologically. Several are characterized by fine scaling and have the prefix ‘pityriasis’, which means ‘bran-like scale’.

Table 1 Papulosquamous eruptions

Pityriasis rosea

Pityriasis rosea is an acute, self-limiting disorder probably infective in origin, characterized by scaly oval papules and plaques that occur mainly on the trunk.

Clinical presentation

The generalized eruption is preceded in most patients by the appearance of a single lesion, 2–5 cm in diameter, known as a ‘herald patch’ (Fig. 1). Some days later, many smaller plaques appear, mainly on the trunk but also on the upper arms and thighs. Individual plaques are oval, pink and have a delicate peripheral ‘collarette’ of scale. They are distributed parallel to the lines of the ribs, radiating away from the spine. Itching is mild or moderate. The eruption fades spontaneously in 4–8 weeks. It tends to affect teenagers and young adults. The cause is unknown, but epidemiological evidence of ‘clustering’ suggests an infective aetiology.

Differential diagnosis and management

Guttate psoriasis, pityriasis versicolor and secondary syphilis may cause confusion. A serological test for syphilis is needed in doubtful cases. The condition is self-limiting, and treatment does not hasten clearance, although a moderate potency topical steroid can help to relieve pruritus.

Pityriasis (tinea) versicolor

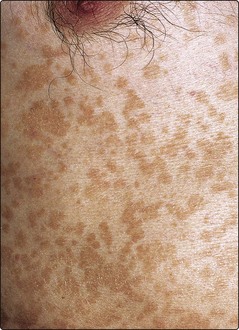

Pityriasis versicolor is a chronic, often asymptomatic, fungal infection characterized by pigmentary changes and involving the trunk.

Clinical presentation

The condition is caused by overgrowth of the mycelial form of the commensal yeast Malassezia (previously Pityrosporum ovale) and is particularly common in humid or tropical conditions. In Europe, it mainly affects young adults, appearing on the trunk and proximal parts of the limbs (Fig. 2). In untanned, white caucasians, brown or pinkish oval or round superficially scaly patches are seen, but, in tanned or racially pigmented skin, hypopigmentation is found as a result of the release by the organism of dicarboxylic acids that inhibit melanogenesis.

Differential diagnosis

Differentiation from vitiligo is important: usually pityriasis versicolor has a fine scale, and scrapings readily show the ‘grapes and bananas’ appearance of the spores and short hyphae on microscopy. Pityriasis rosea and tinea corporis may occasionally appear similar.

Management

Treatment involves either the topical application of one of the imidazole antifungals (e.g. Canesten or Daktarin cream) or the use of 2.5% selenium sulphide (Selsun) shampoo applied for 30 min (or ketoconazole (Nizoral) shampoo applied for 30 min) and showered off (use three times a week for 2 weeks). Itraconazole, 200 mg by mouth daily for 7 days, is effective for resistant cases. Recurrences are common, and patients are advised that re-treatment may be required.

Reiter’s disease

Reiter’s disease is a syndrome of polyarthropathy, urethritis, iritis and a psoriasiform eruption.

Clinical presentation and management

Reiter’s disease almost invariably affects males who have the HLA-B27 genotype and commonly follows a genitourinary or bowel infection. The joint and eye changes are often severe. Skin involvement includes a balanitis (p. 121) and red, scaly, pustular, psoriasiform plaques on the feet (keratoderma blenorrhagicum).

Severe skin changes are unresponsive to topical therapy, and methotrexate or acitretin by mouth is often needed.

Chronic superficial dermatitis

Previously known as parapsoriasis, a term best avoided, this is an uncommon chronic dermatitis of small scaly pink–brown oval or round-shaped plaques, mainly on the trunk. The variant with larger plaques may proceed to mycosis fungoides (cutaneous T cell lymphoma) or be this from the onset.

Clinical presentation

In chronic superficial dermatitis, scaly patches develop, usually on the abdomen, buttocks or thighs (Fig. 3). The onset is in young to mid-adult life, and the plaques are indolent. It may be difficult to predict which cases will progress to mycosis fungoides (p. 104), especially as the evolution may take place over many years, but the ‘benign’ lesions tend to be small and finger-like in shape, whereas the ‘premalignant’ plaques are larger, asymmetrical, atrophic and can show associated poikiloderma (reticulate pigmentation, telangiectasia and atrophy). Biopsy is necessary to look for the changes of mycosis fungoides, and further biopsy of any changed area is required. The disease is often indolent and may persist over a period of several years.

Differential diagnosis and management

Psoriasis, discoid eczema and tinea corporis may need to be considered in the diagnosis, but the plaques of chronic superficial dermatitis are distinguished by being fixed.

The first-line treatment with moderately potent topical steroids is sometimes helpful. Ultraviolet B (UVB) or psoralen with UVA (PUVA) will often be needed for the large plaque variant. Long-term follow-up is recommended.

Other pityriases

Other varieties of pityriasis include the following:

Pityriasis lichenoides. A rare chronic eruption in which small papules topped by a fine single scale appear on the limbs and trunk. It is seen in adolescents and young adults and may occur in an acute form (Fig. 4), which heals with scarring.

Pityriasis lichenoides. A rare chronic eruption in which small papules topped by a fine single scale appear on the limbs and trunk. It is seen in adolescents and young adults and may occur in an acute form (Fig. 4), which heals with scarring.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris. A rare, scaly follicular eruption, which may progress to erythroderma (see p. 44).

Pityriasis rubra pilaris. A rare, scaly follicular eruption, which may progress to erythroderma (see p. 44).

Pityriasis alba. Occurs in children or young adults and is characterized by fine scaly white patches on the face or arms. It is a type of eczema and often seen in atopic patients.

Pityriasis alba. Occurs in children or young adults and is characterized by fine scaly white patches on the face or arms. It is a type of eczema and often seen in atopic patients.

Secondary syphilis

Definition

Secondary syphilis is an inflammatory response in the skin and mucous membranes to the disseminated Treponema pallidum spirochaete. There has been a resurgence of syphilis in recent years.

Clinical presentation

The secondary phase of syphilis (p. 120) starts 4–12 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre and consists of an eruption, lymphadenopathy and variable malaise. Pink or copper-coloured macules, which later develop into papules, appear in a symmetrical distribution on the trunk and limbs and are non-itchy (Fig. 5). Annular patterns are not uncommon, and involvement of the palms and soles is distinctive. Other signs are moist warty lesions (condyloma lata) in the anogenital area, buccal erosions that may be arcuate (snail-track ulcers) and a diffuse patchy alopecia. Mucosal lesions are infectious. Without treatment, the lesions of secondary syphilis resolve spontaneously in 1–3 months.

Differential diagnosis and management

Pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, drug eruption, infectious mononucleosis, rubella and measles may need to be considered. Treponemal serology is positive in all patients with secondary syphilis. Treatment is with intramuscular benzathine benzylpenicillin (p. 120). Patients with syphilis are best managed by physicians familiar with the treatment of genitourinary infections.

Papulosquamous eruptions

Pityriasis rosea is a fairly common self-limiting eruption that involves the trunk of young adults. Scaly oval plaques follow a herald patch. It may be infective in origin.

Pityriasis rosea is a fairly common self-limiting eruption that involves the trunk of young adults. Scaly oval plaques follow a herald patch. It may be infective in origin.

Pityriasis versicolor is a common truncal eruption of young adults and is due to Malassezia, a commensal yeast. It is often revealed in the summer as pale areas adjacent to tanned skin.

Pityriasis versicolor is a common truncal eruption of young adults and is due to Malassezia, a commensal yeast. It is often revealed in the summer as pale areas adjacent to tanned skin.

Reiter’s syndrome typically affects young males and follows a genitourinary or bowel infection. Keratotic skin lesions are seen with eye and joint changes.

Reiter’s syndrome typically affects young males and follows a genitourinary or bowel infection. Keratotic skin lesions are seen with eye and joint changes.

Chronic superficial dermatitis is an uncommon truncal eruption seen in young or middle-aged adults. The large plaque variant may represent early cutaneous T cell lymphoma.

Chronic superficial dermatitis is an uncommon truncal eruption seen in young or middle-aged adults. The large plaque variant may represent early cutaneous T cell lymphoma.

Pityriasis lichenoides is a rare chronic eruption of scaly-topped papules on the trunk and limbs. An acute form may scar.

Pityriasis lichenoides is a rare chronic eruption of scaly-topped papules on the trunk and limbs. An acute form may scar.

Secondary syphilis is a symmetrical, non-itchy truncal eruption with mucosal and palmar or plantar lesions, due to infection with Treponema pallidum.

Secondary syphilis is a symmetrical, non-itchy truncal eruption with mucosal and palmar or plantar lesions, due to infection with Treponema pallidum.