CHAPTER 55 Persons with Fixed and Removable Dentures

Describe demographics, risk factors, disease patterns, and psychologic factors associated with tooth loss.

Describe demographics, risk factors, disease patterns, and psychologic factors associated with tooth loss. Explain appliances used in fixed and removable prosthodontic therapy and the implications for dental hygiene care.

Explain appliances used in fixed and removable prosthodontic therapy and the implications for dental hygiene care.Normally, individuals are not conscious of the critical daily functions of teeth: eating, speaking, facial expression, and appearance. Once the teeth are lost, the person quickly realizes that eating becomes more difficult, speech is not as distinct, and facial tissues lose support, which ultimately impairs appearance and other people's perceptions of the person.

The term edentulous is derived from the Latin word edentatus, means being without teeth or lacking teeth. Although the percentage of persons with tooth loss increases with age, it is not uncommon to find clients in their second through fifth decades of life with prostheses. A prosthesis is a fixed or removable appliance that is functionally and cosmetically designed to replace a missing natural tooth or teeth. Although maintaining the oral health of clients with tooth loss entails the same basic elements of preventive and therapeutic care as for clients with a complete dentition, those with missing teeth have specialized needs. Dental hygienists must be knowledgeable about how to meet the specialized needs of clients with prostheses.

DEMOGRAPHICS OF TOOTH LOSS

Changing patterns in oral disease, professional care, and attitudes toward healthcare have decreased the number of completely edentulous individuals. Nevertheless, surveys indicate that the total number of edentulous individuals is between 20 and 25 million, suggesting that the provision of complete dentures is common in the oral healthcare environment and may remain so given longer life spans and the growing elderly population.1

Approximately 30% of U. S. adults aged 65 or older are edentulous.1 Approximately 50% of Canadian adults aged 65 or older are edentulous. These figures suggest that dental hygienists are likely to encounter edentulous clients within any dental hygiene practice setting.

RISK FACTORS FOR TOOTH LOSS

Major risk factors that contribute to a person's edentulous status are as follows:

The primary reason for tooth loss before age 35 years is dental caries, while periodontal diseases are responsible for tooth loss during the third through the fifth decades of life. Oral cancer, and the corresponding treatment for oral cancer, and oral injury also contribute to tooth loss. In addition, tooth loss is influenced by a client's socioeconomic status, access to professional oral care, frequency of professional oral care, and daily oral hygiene.

OTHER FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH TOOTH LOSS

Psychologic Factors

Client attitude and values influence the success of care, and the edentulous or the partially edentulous person is no exception. Wholesome facial image often is in deficit because of tooth loss, fear of aging, decreased sexuality, feelings of insecurity, fear of rejection, loss of self-esteem, and unrealistic expectations for tooth replacement. Self-esteem loss is especially related to clients in whom tooth loss is attributed to oral cancer and oral cancer treatment. Human responses associated with tooth loss include the five stages of bereavement, behavioral changes, embarrassment, and loss of dignity. These responses need to be considered when providing care for edentulous or partially edentulous clients.2

Physiologic Factors

Although prostheses can restore many oral functions when a person experiences tooth loss, remodeling of the orofacial tissues is invariably encountered. Placement of prostheses introduces unfamiliar forces that contribute to the following:

Residual Ridge and Alveolar Bone Resorption

After tooth extraction, major bony changes, such as residual alveolar ridge resorption, occur within the first year and continue throughout life. Correlation between degree of alveolar bone resorption and the duration of edentulousness is well documented. Metabolic bone disease, postmenopausal osteoporosis, and a calcium-poor diet also contribute to severe mandibular atrophy in edentulous individuals.3

Generally, older individuals resorb bone at faster rates than younger individuals because of anatomic, metabolic, functional, and prosthetic factors. Problems that arise as a result of residual bone resorption are magnified as the person ages. For example, severe resorption of the mandibular alveolar ridge may expose the contents of the mandibular canal and cause extreme discomfort from the prosthesis. In addition, compression of an exposed mental nerve at or near the crest of the alveolar ridge with only a thin layer of oral mucosa overlying it may cause pain and paresthesia of the lower lip and chin. During assessment, if the dental hygienist finds unmet needs for a biologically sound and functional dentition or freedom from fear and stress, immediate dental referral is indicated.

Resorption of alveolar ridges diminishes stability and retention of the prosthesis as the bony ridges continue to flatten with time. Generally, bony changes observed in the mandibular arch differ significantly from those in the maxilla. The rate of resorption is four times greater in the mandible than in the maxilla. Occasionally, irregular patterns of alveolar ridge resorption create numerous sharp spikes, especially in the mylohyoid ridge. Considerable pain can develop as the mucous membrane covering becomes trapped between the hard prosthesis base and sharp bone.3

Other bony contours from either growth abnormalities or alveolar resorption may create undesirable consequences and should be noted. Exostoses, benign bony outgrowths, frequently occur on the hard palate and lingual aspect of the mandibular alveolar ridge and are known as palatal tori and mandibular tori, respectively. Their surgical removal, before prosthesis construction, prevents the possibility of irritation of the overlying oral mucosa by the tori. Similarly, large maxillary tuberosities lead to an unsatisfactory fit of the prosthetic appliance.

TYPES OF PROSTHODONTIC APPLIANCES

Individuals can have missing teeth replaced by dental implants (see Chapter 57) or by fixed and removable dentures. Transition from a natural dentition to a completely or partially artificial dentition is a major life event that most individuals find challenging. This situation can affect client needs for wholesome facial image, freedom from anxiety and stress, and a biologically sound and functional dentition. If needs are not met or if clients believe that their needs cannot be met, successful prosthodontic therapy may be jeopardized.

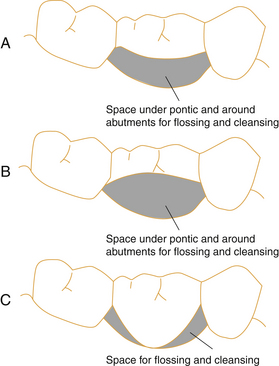

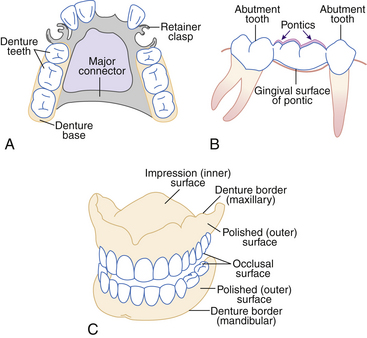

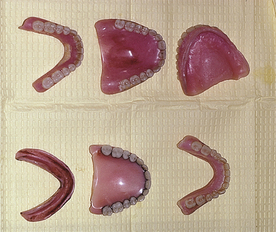

Several types of prostheses ranging from partial to complete can be fabricated to meet clients' needs. The partial denture is used to replace some, but not all, of the natural teeth (Figure 55-1, A). Partial dentures may be fixed or removable. A fixed partial denture is permanently cemented to natural teeth and is commonly called a bridge (see Figure 55-1, B); it cannot be removed by the client.

Figure 55-1 Types of prostheses. A, Removable partial denture. B, Fixed partial denture. C, Complete denture.

Components of fixed partial dentures include the following:

Abutment. The tooth or teeth used to anchor the prosthesis. Abutments are the part of the fixed partial denture used to support the pontic(s).

Abutment. The tooth or teeth used to anchor the prosthesis. Abutments are the part of the fixed partial denture used to support the pontic(s). Pontic. The artificial tooth or teeth that occupy the edentulous space and replace the missing tooth or teeth.

Pontic. The artificial tooth or teeth that occupy the edentulous space and replace the missing tooth or teeth.Removable partial dentures (Figure 55-2) can be removed and replaced by the client. This type of partial denture may be supported by retainer clasps around the natural teeth (Figure 55-3). Complete dentures (Figures 55-4 and 55-5; see Figure 55-1, C) are removable prostheses that replace either the maxillary or the mandibular arch or the entire dentition and associated structures.

Figure 55-2 Mandibular removable partial denture.

(Courtesy Dr. Christopher Wyatt, Prosthodontist, Faculty of Dentistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.)

Figure 55-3 Removable partial denture clap. Note retained plaque biofilm under the clasp in the gingival third of the abutment tooth.

Figure 55-4 Full maxillary and mandibular dentures.

(Courtesy Dr. Christopher Wyatt, Prosthodontist, Faculty of Dentistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.)

If a denture is designed for a client who has undergone oral cancer surgery, it may also need to function as an obturator. An obturator is an appliance that closes an opening or orifice that may have been created by an accident, that may be a congenital cleft, or that may have been caused by the removal of a cancerous tumor. When necessary a denture may be designed to cover an orifice, and in such cases the denture aids in retaining foods and fluids in the mouth and keeping them out of the nasal passage.

Implant dentures are designed to fit over implant fixtures that are inserted partially or entirely into living bone. The increased stability and retention derived from this type of prosthetic appliance have renewed the hopes of the edentulous population for an acceptable alternative to natural teeth (see Chapter 57).

CHALLENGES ASSOCIATED WITH REPLACEMENT OF MISSING TEETH

Although prosthodontic therapy can give the edentulous or partially edentulous individual a biologically sound and functional dentition, success depends on the client's attitude and commitment. At the outset, the client must understand the limitations of tooth replacements and their effectiveness as substitutes for natural teeth. Clients need to be informed about the physical manifestations of bone resorption related to facial appearance, potential speech difficulties, and the effects of tooth replacement on masticatory efficiency. If realistic expectations and goals for care of prostheses are outlined early, the client can successfully adapt to the artificial dentition.

Physical Appearance

Alveolar bone resorption dramatically affects physical appearance and facial image. Modifications in appearance often are visible after extensive alveolar bone resorption, such as loss of facial height (vertical dimension), reduced lip support, a sunken maxillary appearance, and increased chin prominence. The effects of physical alterations attributed to bone resorption include decreased stability, unbalanced occlusion, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, and dissatisfaction with appearance. Usually appearance is judged critically by clients themselves; however, the astute dental hygienist who focuses clients on their positive attributes increases their self-esteem and reduces their anxiety and stress.

Speech Disturbances

Speech patterns are affected by loss of teeth, loss of associated periodontal structures, and the acquisition of prostheses. Transient speech articulation difficulties and oral resonance problems are expected but soon disappear.2 To facilitate speaking with a new oral appliance, clients need to be instructed to read aloud and to speak in front of a mirror. If a speech disturbance persists longer than a few days, the prosthesis may be ill fitting and reevaluation by a dentist warranted. A speech deficit also can arise in conjunction with bone resorption because a loosely fitting prosthesis is difficult to control.

Masticatory Efficiency

Masticatory efficiency with prostheses is estimated to be 20% of that of individuals who have a natural dentition. Two primary reasons for reduction in masticatory abilities are loss of periodontal support and stability, and periodontal proprioception.

The periodontal ligament support area is critical to the stability of a prosthesis confined to one arch only. However, in edentulous persons periodontal ligament support is one fourth to one half of the support of the natural dentition. Furthermore, proprioception is a major component of the body's reception and interpretation of sensation. Without this feedback regarding movement and position from the pressoreceptors in the periodontal ligaments, chewing ability declines significantly.

Biting and chewing forces decrease tenfold and threefold, respectively, in persons with complete prostheses. Although the muscles of mastication are adequate, the mucous membrane covering the edentulous ridge cannot withstand the pressures exerted. The clients have greater success with a new prosthesis if they are taught to avoid repeated incision using anterior teeth, gum chewing, and sticky foods. Clients also need be instructed to consume food in smaller pieces, lengthen chewing time, and evenly distribute food to both the left and right sides of the mouth while chewing. Practicing these behaviors is critical to masticatory efficiency and prosthesis stability.

FACTORS AFFECTING THE ORAL MUCOSA OF DENTURE-WEARING INDIVIDUALS

Systemic Diseases and Conditions

Poor general health results in denture problems, such as friable denture-bearing mucosa. For example, a person with kidney dysfunction may have dehydrated mucosal tissues because of a water imbalance, and thus the mucosa becomes vulnerable to trauma. Decreased tolerance to stress, impaired healing, emotional strain, and medications related to poor systemic health adversely affect oral soft tissues. Systemic conditions that may require modification of dental hygiene care include cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, allergies, psychologic problems, and chronic diseases such as diabetes, anemia, and postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Medications taken for systemic diseases or conditions can affect a client's oral condition and must be assessed and documented during each appointment (see Chapter 12). Hormones, digitalis, nitroglycerin, diazepam (Valium), and chlordiazepoxide (Librium) are among the many medications that can affect the oral environment of the edentulous client. Xerostomia, a common side effect of diuretic, antihypertensive, and antidepressive drugs, interferes with complete denture retention and stability as a result of a loss of mucosal lubrication. Uncontrollable tongue and facial movements may develop with psychotropic medications. Drugs such as cortisone, thyroid hormone, and estrogen may perpetuate a chronic soreness of mucosal tissues.4

Xerostomia (Dry Mouth)

Extreme difficulties experienced by the edentulous client with dry mouth warrant an understanding of the critical role of saliva in the maintenance of oral health. Normal salivary flow is essential for denture retention and function. A thin film of saliva provides adhesive action as well as lubrication and cushioning effects. When the mouth becomes dry, movement of the denture can cause frictional irritation of the denture-bearing mucosa. Other symptoms may arise as a result of oral dryness, including altered taste perceptions, cracked lips, a fissured tongue, and burning mouth syndrome. Although the exact cause of xerostomia may be difficult to identify, the most common factors associated with it are as follows:

Diminished salivary output is not directly associated with increased age; therefore other factors need to be considered if xerostomia is observed in older adult clients who wear dentures.

Xerostomia Management

Professional care for the denture client with xerostomia can be challenging because most remedies provide only temporary relief. The dental hygienist may recommend saliva substitutes and frequent mouth rinsing, especially during meals, to keep the mouth lubricated and to provide temporary symptomatic relief. Also, coating the tissue surface of dentures with petroleum jelly, silicone fluid, or denture adhesive material and sucking on ice chips and using xylitol gum and mints are recommended for the management of soft-tissue dryness.

In addition, oral pilocarpine (5 mg three times per day) decreases symptoms associated with xerostomia by increasing salivary flow.4 This prescriptive medication is effective in clients who have undergone head and neck radiation therapy. Although pilocarpine has not been tested in denture-wearing populations, it may be of value for denture-wearing individuals with dry mouth. This treatment option may be discussed with the client's dentist or physician and then presented to the client.4

Moisturizing products to recommend include oral lubricants, mouth rinses, toothpastes, sprays, and lozenges (e.g., Biotene, Salese, Oasis, Spry).

Denture Occlusion and Fit

The state of the oral mucosa overlying the ridges directly affects the comfort of removable partial and complete dentures. A thicker mucosal covering is more resilient and provides more padding than a thin mucosa. Unfortunately, dental interventions for minimizing discomfort associated with friable mucosa are limited. Soft lining materials such as tissue conditioners and resilient liners may alleviate discomfort for some individuals. Tissue conditioners and resilient liners, composed of soft, flexible elastomer polymers, palliatively treat chronic soreness and protect supporting tissues from functional and parafunctional occlusal stresses. Dentures with a flexible elastomer require special care because these soft materials cannot be cleaned effectively and debris can accumulate and support halitosis, a disagreeable taste, and the growth of Candida albicans. Most professionals recommend use of a very soft brush with a nonabrasive dentifrice. Oxygenating and hypochlorite-type denture cleaners can damage resilient liners and tissue conditioners. Clients need to be cautioned to avoid these types of denture cleaners.

Oral Hygiene

The client's oral mucosa reveals information about daily self-care. Accumulation of bacterial plaque biofilm, stain, and calculus on the denture and oral mucosa leads to offensive odors and mucosal irritations, such as the following:

Denture stomatitis: inflammation of the oral mucosa underlying the denture, characterized by redness, pain, and swelling

Denture stomatitis: inflammation of the oral mucosa underlying the denture, characterized by redness, pain, and swellingPresence of any of these conditions mandates that the client be educated about oral hygiene interventions to maintain the health of mucosal tissues. Specific oral hygiene techniques and products are presented in Chapters 21, 22, 23, 29, and 31.

Continuous Wear of Dentures

Masticatory stress exerted by dentures may compromise residual alveolar ridges and oral mucosa. In addition, the risk for an inflammatory condition increases if the tissues are not allowed to rest. Therefore clients are advised to remove their dentures overnight or for several hours during each 24-hour period. While out of the mouth, dentures need to be cleaned thoroughly and placed in a container filled with water to prevent drying and denture base material damage.

DENTURE-INDUCED ORAL LESIONS

Understanding the soft-tissue response to prostheses enables the dental hygienist to assess the client's skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck. The soft tissues primarily associated with the prosthetic appliance are the tongue, floor of the mouth, cheeks, lips, and mucosa overlying the edentulous ridge.

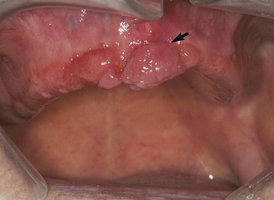

Prosthesis-bearing tissues react differently from individual to individual. For example, differences in the thickness of the mucosa in conjunction with varying degrees of keratinization can be expected in the mouth of the denture-wearing client. Some edentulous persons develop a prosthesis-induced fibrous hyperplasia as a result of fibrous tissue proliferation following alveolar bone resorption under an ill-fitting prosthesis (Figure 55-6). Although detection is sometimes difficult because of nearly normal color and texture, this flabby hyperplastic tissue is identified by palpating freely movable tissue over edentulous ridges or on the vestibular mucosa.

Figure 55-6 Prosthesis-induced fibrous hyperplasia. Chronic denture-induced trauma or irritation has resulted in an overgrowth (arrow) of soft tissue. The chief complaint from the patient was an ill-fitting denture.

(Courtesy Dr. Catherine Poh, Oral Pathologist, Faculty of Dentistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.)

If fibrous tissue proliferation is observed, the dental hygienist refers the client to the dentist for evaluation and treatment. Depending on the severity of hypermobile tissue, treatment may involve a period of tissue rest, prosthesis adjustment, and/or surgical excision to reduce the excess tissue. Keratinization of edentulous alveolar ridges may be completely absent or may progress to a hyperkeratinized state. This focal (frictional) hyperkeratosis, classified as a hyperkeratotic white lesion of the oral mucosa, usually resolves with time on discontinuation of the underlying trauma.5

Although it is highly unlikely that chronic irritation due to ill-fitting dentures will cause oral carcinoma, trauma induced by dentures and other mechanical irritations probably accelerates the progression of the disease. It is important for the dental hygienist to be especially attentive to signs and symptoms of oral cancer: ulceration or erosion, induration, fixation, chronicity, lymphadenopathy, leukoplakia, and erythroplakia (see Chapter 44).

Many oral mucosal conditions in denture wearers are associated with improper oral hygiene care, extended denture wear, or poor prosthesis fit. More specifically, denture-induced lesions are subdivided into the following three categories according to causative factors and clinical features5 (Table 55-1):

TABLE 55-1 Types of Oral Soft-Tissue Lesions in Denture-Wearing Clients Indicating an Unmet Need for Skin and Mucous Membrane Integrity of the Head and Neck

| Oral Manifestation | Due to | As Evidenced by |

|---|---|---|

| Reactive Lesions | ||

| Acute ulcers | ||

| Chronic ulcers | Same as above | |

| Focal (frictional) hyperkeratosis | Chronic rubbing or friction of dentures | |

| Denture-induced fibrous hyperplasia (epulis fissurata, denture hyperplasia) | Ill-fitting denture | |

| Infectious Lesions | ||

| Denture stomatitis (denture sore mouth) | ||

| Angular cheilitis | ||

| Mixed Lesions | ||

| Papillary hyperplasia | ||

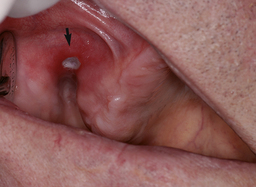

Figure 55-7 Reactive/traumatic lesion. A traumatic ulcer (arrow) resulting from elongated buccal flange of the upper complete denture.

(Courtesy Dr. Catherine Poh, Oral Pathologist, Faculty of Dentistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.)

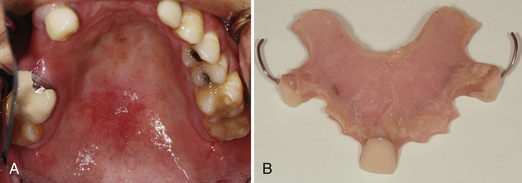

Figure 55-8 Infectious lesions. A, Chronic candidiasis on upper palate (erythematous area). B, Partial denture causing the palatal lesion.

(Courtesy Dr. Catherine Poh, Oral Pathologist, Faculty of Dentistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.)

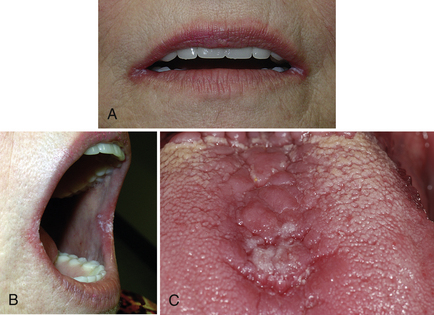

Figure 55-9 Oral candidiasis. A and B, Angular cheilitis. Note on mouth commissures there are bilateral irregular white plaques on an erythematous base. C, Candidiasis on dorsum of tongue (erythematous and depapillated area at the center).

(Courtesy Dr. Eli Whitney, Certified Specialist in Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology, Faculty of Dentistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.)

Figure 55-10 Mixed reactive and infectious lesions. Palatal papillary hyperplasia associated with candidiasis. Note that the generalized granular erythematous change of the palatal mucosa matches the shape of a repeatedly relined removable partial denture. Also note denture-induced papillary hyperplasia of the palate.

(Courtesy Dr. Catherine Poh, Oral Pathologist, Faculty of Dentistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.)

Generally, denture relining or remaking and/or client education can eliminate the irritation.

Reactive or Traumatic Lesions

Reactive or traumatic lesions commonly are secondary to either acute or chronic injury. Lesions in this category are ulcers (see Figure 55-7), focal (frictional) hyperkeratosis, and denture-induced papillary hyperplasia (see Figure 55-10). Figure 55-11 shows an overexuberant repair response that produces hyperplastic tissue. This condition often is painless, but pain may develop if the fibrous lesion is traumatized or ulcerated. Surgical excision and removal of the irritating factor are effective methods of treating reactive lesions.5 Palliative treatment can include products such as Cancer Cover, Rincinol, and Ameseal.

Figure 55-11 Prosthesis-induced fibrous hyperplasia (epulis fissuratum). Chronic denture-induced trauma has resulted in leaflike masses (arrow) of soft tissue that overgrow the denture flange.

(Courtesy Dr. Catherine Poh, Oral Pathologist, Faculty of Dentistry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.)

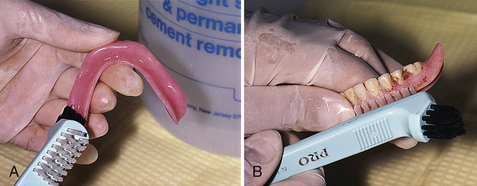

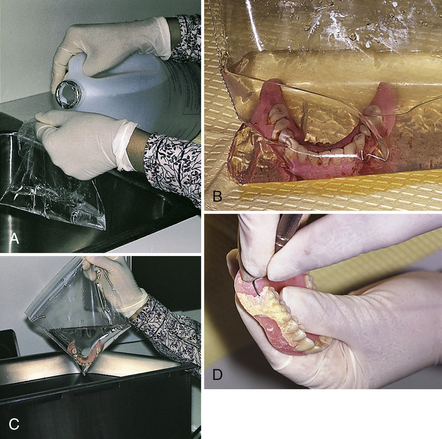

Figure 55-12 Ultrasonic cleaning of denture. A, Fill plastic bag with stain and calculus remover solution. B, Place denture in bag with solution. C, Place bag in ultrasonic cleaner chamber and set for 10 to 14 minutes. D, Some dentures may require manual scaling to remove deposits; however, the inner impression is avoided.

(Courtesy Bertha Chan.)

Figure 55-13 Inexpensive denture cleaners. A, Combination of sodium hypochlorite, Calgon, and water for denture without metal. B, Combination of hydrogen peroxide and sodium bicarbonate forms an alkaline peroxide solution for dentures with metal.

(Courtesy Bertha Chan.)

Infectious Lesions

Denture Stomatitis

The most common inflammation of the denture-bearing mucosa is denture stomatitis (see Figure 55-8). Despite minimal pain associated with denture stomatitis, it is often referred to inappropriately as “denture sore mouth.” With a predilection for women, the condition has an incidence of 20% to 40% of the edentulous population and occurs in up to 65% of older adults who wear complete maxillary dentures.5

Angular Cheilitis

Angular cheilitis is a mixed bacterial and fungal infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus and C. albicans (see Figure 55-9, A and B). The condition results from small amounts of saliva accumulating at the commissural angles, which promotes the colonization of yeast. Clinically, angular cheilitis appears as cracked, eroded, and encrusted commissural folds and may cause moderate pain. Often it is secondary to overclosure resulting from a reduction in the client's vertical dimension. Vitamin B (riboflavin) deficiency resulting from inadequate nutrition also can cause angular cheilitis.5

Dental treatment requires correcting the denture to eliminate trauma and prescribing antifungal drugs to eliminate the Candida infection. Dental hygiene care to prevent recurrence includes instructing the client in thorough daily cleansing of the infected denture using chemical immersion. A weak sodium hypochlorite solution is used to soak the denture overnight (Box 55-1). Sodium hyperchlorite damages metal and should never be used when metal is part of any oral appliance. Moreover, if the sodium hyperchlorite is too concentrated, it can bleach the colored portion of the resin base and discolor soft reline materials. Other denture cleaners include nonabrasive dentifrices, commercial denture cleaners, and vinegar. Household cleaners other than a weak sodium hypochlorite solution should never be used to clean oral appliances (see section on denture cleansers).

Chronic Candidiasis

Most denture-related infections, including denture stomatitis, are caused by a chronic candidiasis infection and are treated using a topical antifungal agent such as nystatin. Prescribed by the dentist for use at home, nystatin cream is applied to both affected tissues and the dentures to eliminate the fungi. To be effective, topical antifungal agents must be used by the client for approximately 1 week after the disappearance of clinical symptoms.

A chronic Candida infection is primarily responsible for the development of denture stomatitis, although recent studies implicate bacteria as the causative agent: gram-positive Streptococcus species and Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, and Actinomyces species. Other contributing factors include plaque biofilm accumulation on dentures; chronic, low-grade soft-tissue trauma due to ill-fitting dentures; an unbalanced occlusal relationship; and continuous wearing of the denture at night. In some circumstances systemic conditions such as diabetes, anemia, menopause, malnutrition, and nutrient malabsorption in the digestive tract can predispose an individual to a Candida infection.

Chronic candidiasis appears on the palatal mucosa rather than on the mandibular alveolar mucosa (see Figure 55-8). Clinical features demonstrate variations in surface texture ranging from a smooth, velvety appearance to a more nodular or hyperplastic form. With severe infections, surfaces may appear eroded, with small confluent vesicles. Characteristically the bright-red color of the denture-supporting mucosa is confined within a well-defined denture border.5

Mixed Reactive and Infectious Lesions (see Figure 55-10)

Both trauma and infection are causative factors contributing to mixed reactive and infectious lesions, such as papillary hyperplasia. A “cobblestone” appearance describes the granular papillary projections that result from a hyperplastic tissue response. This condition can predispose or potentiate the growth of C. albicans under the denture and further complicate the problem. Multiple dental therapies to resolve the lesions include surgical excision, antifungal agents, soft-tissue conditioners and liners, and strict oral hygiene measures.5

IMPORTANCE OF REGULAR PROFESSIONAL CARE

Findings from a national study reported that only 13% of edentulous seniors had seen a dentist within the previous 12 months, and 67% of them had not visited the dentist within the previous 3 years.1 These findings underscore a critical role for the dental hygienist in encouraging regular maintenance care and in recognizing oral changes that often go unnoticed by the client.

Periodic maintenance care provides an excellent opportunity to identify denture-related tissue lesions and refer clients for dental evaluation and treatment. Although studies have demonstrated no correlation between cancer at specific sites and the wearing of dentures, denture irritation may be a co-carcinogenic factor in predisposed individuals.

Some clients erroneously perceive that prostheses last a lifetime without further modifications; however, in reality new prostheses are needed every 4 to 8 years. Hence, education is a priority for the prosthesis-wearing individual.

DENTAL HYGIENE CARE FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH FIXED AND REMOVABLE DENTURES

From the outset, the client needs to be educated regarding expectations, oral hygiene practices, denture use and care, and regular periodic maintenance appointments. Also, the dental hygienist educates the client about the causes of bone resorption and suggests methods of minimizing the rate of resorption, including removal of the prosthesis at night, regular evaluation to ensure well-fitting prostheses, and a calcium-rich diet. Resorption rates vary enormously among individuals, and well-fitting prostheses decrease the rate of resorption. Local factors including trauma can affect the rate of resorption so that the prosthesis becomes ill-fitting.

Successful prosthodontic therapy also greatly depends on clients who possess a sense of responsibility regarding their oral health status. The dental hygienist encourages clients to set personal goals for oral health and suggests behavior patterns and techniques that are compatible with their lifestyle, cultural customs, values, and physical capabilities.

The edentulous person's ability to adapt to the prosthesis greatly influences eating pleasure, eating proficiency, and overall health. The quality and quantity of nutritional intake are not necessarily modified in the edentulous individual. Nonetheless, if the prosthesis is ill-fitting, nutritional status may suffer. Eating becomes a chore and less pleasurable. The dental hygienist facilitates success of denture therapy by assessing the client's nutritional status and providing dietary counseling to ensure that nutritionally rich foods, such as vegetables, meats, beans, fish, and fruits, are not ignored (see Chapter 33).

The dental hygienist assesses loss of retention, stability, and support of the prosthesis and calls problems to the dentist's attention (Procedure 55-1). The dental hygienist also documents unmet human needs, informs both the client and the dentist, and recommends daily self-care to prevent further tissue destruction.

Procedure 55-1 PROFESSIONAL CARE FOR CLIENTS WITH FIXED AND REMOVABLE DENTURES

STEPS

Assessment

Implementation

The newly edentulous person commonly requires a denture adjustment within the first 6 to 12 months. Thereafter, annual continued care is essential to denture longevity and meets the need for denture duplication, rebasing, or replacement. Individuals with poor oral hygiene may require more-frequent visits.

Clients need to be advised of the importance of daily care of their dentures and the associated soft tissues. Procedure 55-2 provides instructions for daily oral care for individuals with removable prostheses. Procedure 55-3 provides an overview of instructions for daily oral care for individuals with fixed prostheses. Both verbal and written instructions reinforce the homecare regimen, especially for the elderly. A simple reminder to rinse the dentures and mouth after each meal helps eliminate accumulation of food debris and plaque biofilm. Written instructions or other formal educational materials that include proper denture hygiene and cleansing of the oral tissues provide specific, tangible recommendations for maintaining oral health. Pertinent information to teach the client is presented in the section on client education issues. At continued-care visits, the dental hygienist assesses the client's ability to perform meticulous oral hygiene care at home.

Procedure 55-2 DAILY ORAL AND DENTURE HYGIENE CARE FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH REMOVABLE PROSTHESES

EQUIPMENT

STEPS

Procedure 55-3 DAILY ORAL CARE FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH FIXED PROSTHESES

EQUIPMENT

STEPS

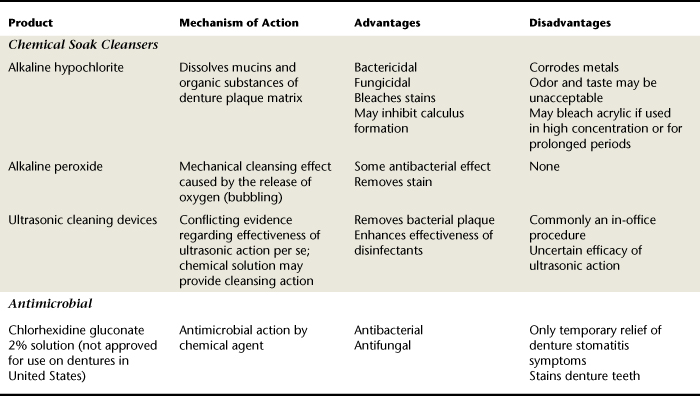

DENTURE CLEANSERS

Maintaining denture hygiene is essential to promote esthetics, control malodor, and prevent and treat oral infections in the denture client. Proper hygienic care can be confusing for the client because of the many products available for home use as well as the various in-office procedures used to maintain denture hygiene. Commonly available denture cleansers include the following:

Table 55-2 describes common denture cleansers available. When selecting a denture cleanser, denture-wearer and denture safety are paramount. Abrasive powders and pastes are not recommended for cleaning dentures because of the potential for the client to use these products incorrectly, thus damaging the prosthesis. Denture acrylic can become abraded, and this abrasion may alter the denture fit if a hard-bristle brush or extreme vigor is used when the prosthesis is cleaned.

Denture cleanser efficacy depends partially on the client's dexterity. Brushing with toothpaste is suitable for the client who is motivated and has the dexterity to thoroughly clean all surfaces; however, this denture cleansing method is the most difficult, especially for the physically challenged or older adult client. Chemical soak cleansers are effective alternatives to mechanical cleansing. Alkaline peroxide and hypochlorite solutions can be recommended for dentures with and without metal components, respectively. The majority of clinical studies report hypochlorites to be the most efficacious soaking method for dentures constructed with only acrylic materials. Caution, however, must be taken to avoid use of hypochlorites on any metal-containing prostheses. If an offensive taste and odor linger after the hypochlorite soak, alkaline peroxide may be used subsequently. (See Box 55-1 for how to make an effective denture cleaner.) Table 55-3 presents the variety of oral appliances and dental prostheses that also can be cleaned by these denture-cleaning methods.

TABLE 55-3 Comparison of Various Oral Appliances and Dental Prostheses (also see Chapter 35)

| Appliance | Definition | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Athletic mouth guard (mouth protector) | An oral appliance designed to protect the teeth and head from trauma during contact sports | Prevents oral and facial injury |

| Bleaching trays | A custom-made stent in the shape of the teeth and dental arch for carrying the bleaching or whitening agents | Holds the whitening agent against the tooth surfaces |

| Dentures | Replaces teeth (form, function, and appearance) in edentulous or partially edentulous dental arches | |

| Complete (full) denture | A prosthetic appliance designed to replace an entire arch of missing teeth and the surrounding alveolar bone; can be inserted and removed by the client | Same as for Dentures above |

| Fixed partial denture (bridge) | A prosthetic appliance designed to replace several missing teeth; permanently cemented in place and removed only by the dentist | Same as for Dentures above |

| Removable partial denture | A prosthetic appliance designed to replace several missing teeth and the surrounding alveolar bone; can be inserted and removed by the client | Same as for Dentures above |

| Implant denture | A prosthetic appliance designed to fit over osseointegrated implant fixtures | Same as for Dentures above |

| Immediate denture | A prosthetic appliance placed immediately after remaining teeth are extracted from a partially edentulous arch | Same as for Dentures above |

| Fluoride tray (custom) | A custom-made stent in the shape of the teeth and dental arch for carrying the fluoride agent to the tooth structure | Holds the prescription agent against the tooth surface to decrease caries risk |

| Nightguard and dayguard | A hard acrylic appliance that fits over all or just several of the maxillary or mandibular teeth to create a functional occlusion or to relax the muscles; may be worn at night or during the day | |

| Oral habit appliance | An oral appliance used to interfere with habits such as thumbsucking, tongue sucking, or tongue thrusting | Prevents the habitual behavior from occurring |

| Orthodontic appliance or repositioner | An oral appliance used for tooth movement and the treatment of malocclusion | Provides tooth movement and stabilization |

| Stent | A device used after periodontal surgery to support and protect the oral tissues and/or to hold a medicinal or other desired agent in a particular area | |

| Sleep apnea or snoring appliance | A flexible, custom-made device that positions the jaw forward during sleep | |

| Space maintainer | A fixed or removable oral appliance to maintain a space created by premature tooth loss | Maintains an open space in the dental arch caused by premature tooth loss until the permanent tooth can erupt |

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH FIXED AND REMOVABLE DENTURES

Many of the lesions associated with denture wearing are a result of ill-fitting dentures, poor denture and oral hygiene care, and prolonged wearing of the prosthesis. Nutritional deficiencies are seldom noticed and therefore infrequently corrected. For example, a client deficient in B-complex vitamins may have symptoms of atrophic glossitis; angular cheilitis; or cracking, fissuring, or ulceration of the lips. These clinical signs may be interpreted as a chronic C. albicans infection rather than a nutritional deficiency. Although nutritional deficiencies are difficult to identify, the dental hygienist must be cognizant of changes related to them in some denture wearers. After assessment the dental hygienist informs the dentist of potential nutritional problems and either recommends dietary measures to the client that may improve oral health or refers the client to a dietitian.

Nutritional Factors (see Chapter 33)

Key nutritional factors for clients include the following:

Water is an essential nutrient for all body functions. Hence, evidence of tissue dehydration can be recognized throughout the body, especially in elderly individuals, as wrinkled skin, loss of muscle mass, decreased sweat and sebaceous gland secretions, dry eyes, xerostomia, and a smooth, atrophic tongue. The best dietary recommendation for dehydrated clients is to consume vegetable soup because both water and nutrients are more effectively retained in this form.

A negative calcium balance results in osteoporosis, which can precipitate rapid and extensive resorption of the alveolar ridges. A deficit in calcium intake, absorption, or transport may be responsible for the bony changes. Low-fat milk and milk products are good dietary sources of calcium (see Chapter 33 for food sources of calcium).

Protein depletion most notably affects muscle mass but also may increase tissue fragility and lip cracking. A decrease in mass and strength of the muscles of mastication is especially evident in the older adult and can be monitored by placing the finger in the vestibule of the mouth and asking the client to clench his or her teeth. Clients are encouraged to maintain a high-protein diet (e.g., meat, fish, beans, tofu, and legumes) to maintain muscle mass.

Undoubtedly, food nutritional quality depends on the preparation method. Variations in food preparation result from the client's physical capabilities, living conditions, and cultural preferences. Hence, dietary advice should include cooking instructions that maximize the nutrient value of the diet with consideration of individual circumstances and preferences. For example, meat and fish are most nutritious when broiled or boiled rather than fried. In addition to limiting saturated fat intake, boiling foods breaks down complex proteins into more easily digestible components. On the other hand, fried protein-rich foods lose some nutritional value because the protein coagulates and becomes more difficult to digest.

Nutrition and the Edentulous Older Adult (see Chapters 33 and 54)

For the edentulous older adult, diet is of great concern. Essential nutrient deficiency magnifies the tissue friability and diminishes repair potential observed in geriatric clients. Many older adults have low incomes, inadequate kitchen facilities, loneliness, poor physical health, and other conditions that predispose them to poor nutritional habits. A lack of knowledge and interest in proper nutrition also contributes to malnutrition. The older adult's dietary intake is often affected by wearing dentures, and deficiencies in protein, calcium, and B-complex vitamins may be present. Normally these nutrients are essential in the maintenance and repair of oral tissues and bone. Many older adults have a limited ability to digest and absorb food. This problem can be exacerbated by ill-fitting dentures, which may result in chewing difficulties and diminish consumption of fibrous foods. Hence, digestion, absorption, and use of nutrients are impaired. Two common dietary tendencies of the aged edentulous person are the following:

For these reasons the dental hygienist routinely assesses nutritional habits and suggests healthy food alternatives to promote weight control and a nutritionally balanced diet (Table 55-4). This assessment and counseling can be effectively accomplished if simple, well-defined, concise guidelines are constructed so that no major changes in food habits and preferences are made. The client and the dental hygienist can set nutritional goals, taking into account lifestyle, financial resources, and cultural preferences. With the edentulous client, nutritional deficits should always be considered during determination of factors that contribute to a denture-related problem.

TABLE 55-4 Nutritional Guidelines for Maintenance of Oral Health in Edentulous and Partially Edentulous Clients (also see Chapter 33)

| Nutritional Goal | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Eat a variety of foods. | Essential for repair and maintenance of structurally and functionally competent body parts; increases likelihood of getting necessary nutrients. |

| Select foods high in complex carbohydrates: fruits, vegetables, whole-grain bread, and cereals. | Blood glucose levels rise less if complex carbohydrates are consumed rather than simple sugars. Also, fiber in these foods promotes normal bowel function and may reduce serum cholesterol. |

| Protein-rich foods including lean meat, poultry, fish, dried peas, and beans are required daily. | Maintains strength and integrity of tissues, especially when exposed to physiologic stress. |

| Obtain calcium from dairy products; some nondairy foods also contain substantial amounts of calcium. | Calcium intake is critical to maintain bone mass. Alveolar bone is an early site of calcium withdrawal if dietary calcium intake is low. |

| Consume fruit juices containing vitamin C and citrus fruit daily. | Essential for repair and healing of wounds and for absorption of other vitamins and minerals. |

| Limit intake of processed foods high in saturated and hydrogenated fats and sodium. | |

| Limit intake of bakery products high in fat and simple sugars. | Bakery products are often high in calories and/or low in nutrients. |

| Drink eight glasses of water daily. | Essential nutrient for all body functions. |

Adapted from Zarb GA, Bolender CL, Carlson GE: Boucher's prosthodontic treatment for edentulous patients, ed 11, St Louis, 1997, Mosby.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Explain the types of chemical cleansing agents, frequency and duration of their application, and other instructions for their use (see Table 55-2).

Explain the types of chemical cleansing agents, frequency and duration of their application, and other instructions for their use (see Table 55-2). Demonstrate techniques for mechanical cleaning of the prosthesis and cleansing and massage of the oral tissues (see Procedures 55-1, 55-2, and 55-3).

Demonstrate techniques for mechanical cleaning of the prosthesis and cleansing and massage of the oral tissues (see Procedures 55-1, 55-2, and 55-3). Reinforce the need for regular professional care for denture-wearing individuals that includes intraoral and extraoral assessment and examination of prosthesis.

Reinforce the need for regular professional care for denture-wearing individuals that includes intraoral and extraoral assessment and examination of prosthesis. Emphasize self-care strategies including daily oral hygiene, adequate nutrition, oral tissue self-examination, and resting denture-bearing surfaces.

Emphasize self-care strategies including daily oral hygiene, adequate nutrition, oral tissue self-examination, and resting denture-bearing surfaces. Recommend techniques and products for prosthetic use, care, and cleaning. Avoid oxygenating and hypochlorite-type denture cleaners in the presence of resilient liners and tissue conditioners.

Recommend techniques and products for prosthetic use, care, and cleaning. Avoid oxygenating and hypochlorite-type denture cleaners in the presence of resilient liners and tissue conditioners. Instruct client to consume foods in smaller pieces, lengthen chewing time, evenly distribute food to both the left and the right sides of the mouth while chewing, and avoid repeated incision with anterior denture teeth.

Instruct client to consume foods in smaller pieces, lengthen chewing time, evenly distribute food to both the left and the right sides of the mouth while chewing, and avoid repeated incision with anterior denture teeth.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Provide services within the scope of dental hygiene practice as stipulated by the regulatory body of each province or state.

Provide services within the scope of dental hygiene practice as stipulated by the regulatory body of each province or state. Maintain written and dated records (in ink) of the status of the client's oral condition, condition of dental appliances, the treatment provided, recommended treatment, recommended referrals, client's refusal or acceptance of treatment, and any pertinent information regarding care.

Maintain written and dated records (in ink) of the status of the client's oral condition, condition of dental appliances, the treatment provided, recommended treatment, recommended referrals, client's refusal or acceptance of treatment, and any pertinent information regarding care. Have client remove and reinsert the dental appliance; if the client is unable to do so, the dental hygienist should request that the dentist, accompanying family member, or client caregiver remove and reinsert the prosthesis.

Have client remove and reinsert the dental appliance; if the client is unable to do so, the dental hygienist should request that the dentist, accompanying family member, or client caregiver remove and reinsert the prosthesis.KEY CONCEPTS

A prosthesis is a fixed or removable appliance that is functionally and cosmetically designed to replace a missing tooth or teeth.

A prosthesis is a fixed or removable appliance that is functionally and cosmetically designed to replace a missing tooth or teeth. Persons who wear dental prostheses receive an oral examination periodically to monitor the health of hard and soft tissues, the functional integrity of the prosthesis, and changes that might be warranted. Frequency should be based on the client's risk factors for disease.

Persons who wear dental prostheses receive an oral examination periodically to monitor the health of hard and soft tissues, the functional integrity of the prosthesis, and changes that might be warranted. Frequency should be based on the client's risk factors for disease. A removable dental prosthesis should be marked with the wearer's name or identification number, especially if the person lives in an institutional setting.

A removable dental prosthesis should be marked with the wearer's name or identification number, especially if the person lives in an institutional setting. Just like natural oral structure, the dental prosthesis and oral cavity of the wearer must be thoroughly cleaned daily.

Just like natural oral structure, the dental prosthesis and oral cavity of the wearer must be thoroughly cleaned daily. Risk factors for edentulism include caries, periodontal disease, low socioeconomic status, inadequate access to professional care, low frequency of care, and poor daily oral hygiene.

Risk factors for edentulism include caries, periodontal disease, low socioeconomic status, inadequate access to professional care, low frequency of care, and poor daily oral hygiene. Loss of natural teeth is associated with fear of aging, decreased sexuality, feelings of insecurity, fear of rejection, loss of self-esteem, and unrealistic expectations for tooth replacement.

Loss of natural teeth is associated with fear of aging, decreased sexuality, feelings of insecurity, fear of rejection, loss of self-esteem, and unrealistic expectations for tooth replacement. Oral changes related to tooth loss include resorption of the residual ridge and alveolar bone, oral mucous membrane remodeling, and loss of orofacial muscle tone.

Oral changes related to tooth loss include resorption of the residual ridge and alveolar bone, oral mucous membrane remodeling, and loss of orofacial muscle tone. Clients who lose teeth face challenges in their physical appearance, speech, and masticatory efficiency.

Clients who lose teeth face challenges in their physical appearance, speech, and masticatory efficiency.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

In each case, develop a dental hygiene diagnosis, client goals, and a dental hygiene care plan.

Refer to the Procedures Manual where rationales are provided for the steps outlined in the procedures presented in this chapter.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000.

2. Fiske J., Davis D.M., Frances C., Gelbier S. The emotional effects of tooth loss in edentulous people. Br Dent J. 1998;184:90.

3. Carlsson G.E., Persson G. Morphological changes of the mandible after extraction and wearing of dentures: a longitudinal, clinical, and x-ray cephalometric study covering five years. Odontol Revy. 1967;18:27.

4. Zarb G.A., Bolender C.L., Carlsson G.E. Boucher's prosthodontic treatment for edentulous patients, ed 11. St Louis: Mosby; 1997.

5. Regezi J.A., Sciubba J.J., Jordan R. Oral pathology: clinical pathologic correlations, ed 5. St Louis: Saunders; 2008.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..