Chapter 75The Carpal Canal and Carpal Synovial Sheath

Anatomy

The carpal canal encloses the carpal synovial sheath, which contains the superficial (SDFT) and deep (DDFT) digital flexor tendons. The dorsal wall of the carpal canal is formed by the common palmar ligament of the carpus, which is a thickened part of the fibrous joint capsule that extends distally as the accessory ligament of the DDFT (ALDDFT). Proximally the accessory ligament of the SDFT (ALSDFT) forms the medial wall of the canal. Laterally the carpal canal is formed by the accessory carpal bone and the accessorioquartale and accessoriometacarpeum ligaments extending distally. The caudal antebrachial fascia, flexor retinaculum, and palmar metacarpal fascia form the palmar aspect of the canal.

The carpal synovial sheath extends from 7 to 10 cm proximal to the antebrachiocarpal joint to the midmetacarpal region. The proximal recess is wide and extends between the ulnaris lateralis and lateral digital extensor muscles laterally, but it is firmly supported on the medial aspect by the antebrachial fascia. The distal recess extends between the DDFT and its accessory ligament. If the carpal sheath is distended, swelling can be seen on the lateral aspect of the distal antebrachium and between the DDFT and its accessory ligament, medially or laterally in the metacarpal region.

The ALSDFT arises from the caudomedial aspect of the radius about 10 cm proximal to the antebrachiocarpal joint. The ALSDFT is a fibrous fan-shaped band that merges with the SDFT at the level of the antebrachiocarpal joint and prevents overload of the SDFT muscle during overextension of the metacarpophalangeal joint. After desmotomy of the ALSDFT in cadaver specimens, strain on the SDFT is increased.1 At the level of the distal aspect of the radius is an extension from the lateral aspect of the sheath wall between the SDFT and DDFT. At the level of the accessory carpal bone is a mesotendon extending from the lateral aspect of the DDFT to the sheath wall. In clinically normal horses, the amount of fluid within the carpal sheath varies, but it is usually the same bilaterally in each horse.

Fluid within the sheath may be seen readily by ultrasonography between the DDFT and its accessory ligament in normal horses, with no palpable distention of the sheath wall.2 Within the proximal part of the carpal sheath, the SDFT and DDFT contain muscular tissue and therefore have hypoechoic regions within them on ultrasonographic examination.3-5 However, the ALSDFT is uniform in its echogenicity.4,5 The position of the accessory carpal bone prohibits ultrasonographic examination from the caudal aspect of the carpus. The carpal sheath and its contents are evaluated most easily from the distal caudomedial aspect of the antebrachium and carpus and the palmar aspect of the proximal metacarpal region. The heterogeneous echogenicity of the digital flexor tendons proximally can make definitive diagnosis of a tendon lesion difficult, but comparison with the contralateral limb may be helpful. Endoscopic evaluation may yield further information and permit surgical debridement of torn fibers (see Chapter 24).

The transverse ridge of the distal aspect of the radius is at about the same level as the distal physis. Irregular roughening of this ridge may be seen radiologically in normal horses and should not be confused with entheseous new bone associated with tearing of the attachment of the ALSDFT further proximally.

Occasionally abnormalities cannot be detected using conventional imaging techniques and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is required (see Figure 75-1, B). Normal MRI anatomy of the carpal region has recently been described.6

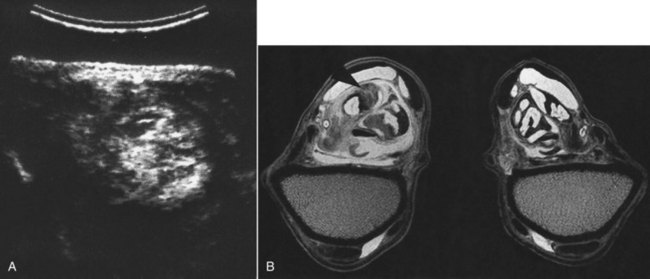

Fig. 75-1 A, Transverse ultrasonographic image of the carpal sheath of a 9-year-old dressage horse with chronic left forelimb lameness of 3 months’ duration. Medial is to the left. There is thickening of the sheath wall and enlargement of the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT), but no internal structural abnormality could be defined because of the normal heterogeneous echogenicity of the tendon at this level from muscle tissue. The horse failed to respond to intrathecal medication or endoscopic debridement of the proliferative synovial membrane. B, Transverse T2* gradient echo magnetic resonance image of the carpus at the level of the musculotendonous junction of the SDFT of the left (shown on the left) and right forelimbs of a horse with chronic left forelimb lameness. There is enlargement of the left fore SDFT. Normal muscle tissue is replaced by an area of low signal intensity consistent with fibrosis (arrow).

Clinical Signs

Lameness associated with the carpal synovial sheath is usually accompanied with some distention of the sheath. There may be generalized thickening in the region of the flexor retinaculum. The horse may have restricted flexibility of the carpus, with pain on passive flexion. Alternatively, the horse may resent full extension of the carpus. Rarely, increased pressure within the carpal sheath may result in compromised blood flow within the median artery and reduction in arterial pulse amplitudes in the more distal part of the limb.7 Palpation of the structures within the proximal part of the carpal sheath is not possible, but the SDFT, DDFT, and ALDDFT should be assessed carefully in the metacarpal region. Lameness varies from mild to severe and usually is improved by intrathecal analgesia. Clinical investigation should include radiographic and ultrasonographic examinations. In the absence of effusion of the carpal sheath, intrathecal analgesia should be performed to verify the source of pain and the clinical significance of any postulated lesion.

Carpal sheath effusion is not always associated with a primary lesion within the sheath per se but can be seen in association with injuries of the ALDDFT, the proximal aspect of the suspensory ligament, trauma or fractures involving the antebrachiocarpal joint, and cellulitis in the distal aspect of the antebrachium, carpus, or proximal metacarpal region (see Chapters 14 and 37).

Idiopathic Synovitis

Synovitis of the carpal sheath usually results in acute-onset, moderate to severe unilateral lameness associated with distention of the carpal sheath. No palpable abnormalities of the digital flexor tendons are apparent. Ultrasonographic examination reveals an abnormal amount of fluid within the sheath but no other structural abnormality. Horses usually respond well to box rest and controlled walking exercise for 4 to 6 weeks, combined with intrathecal administration of corticosteroids and hyaluronan. If lameness is recurrent, synovectomy may be required.

Intrathecal Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage within the carpal sheath may be idiopathic, result from trauma (e.g., a fall), or occur secondary to either a tear of the SDFT or DDFT, a tear of the ALSDFT, or a fracture of the accessory carpal bone (see pages 446 and 780). The horse may be very lame. Diagnosis is confirmed by synoviocentesis. The fluid within the sheath may appear more echogenic than synovial fluid. Careful ultrasonographic examination of the digital flexor tendons and the retinaculum should be performed to identify any primary lesion. In the absence of a primary tendon lesion and fracture, some relief of pain may be gained by draining blood from the sheath. This should be followed by administration of hyaluronan to reduce the risks of subsequent adhesion formation. The horse should be rested for 4 to 6 weeks with administration of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication. The prognosis is usually good unless there is underlying primary pathology.

Trauma Resulting in Chronic Enlargement of the Carpal Sheath

A horse may have acute distention of the carpal sheath and moderate to severe lameness after a fall. In the acute stage, ultrasonographic examination may reveal only an abnormal amount of fluid within the sheath, but over the next several weeks thickening of the sheath wall and the palmar retinaculum may become apparent, with echogenic fibrous material within the sheath (Figure 75-1). The margin of the SDFT or DDFT may be poorly demarcated, and either structure may be enlarged. Some horses respond satisfactorily to rest and controlled exercise combined with repeated medication of the sheath with hyaluronan. Early aggressive treatment seems to yield the best results. Passive flexion of the carpus also may be beneficial. If lameness persists for more than 6 weeks, endoscopic evaluation of the sheath and its contents should be considered (see Chapter 24).

Desmitis of the Accessory Ligament of the Superficial Digital Flexor Tendon

Desmitis of the ALSDFT is an unusual injury in show jumpers, event horses, dressage horses, and Thoroughbred racehorses, but it seems to occur more commonly in European Standardbred trotters.8 The condition is rarely recognized in North American trotters.9 Lameness is usually sudden in onset and associated with localized swelling.

Diagnosis is based on ultrasonographic examination. Abnormalities of the ALSDFT include enlargement, abnormal fiber pattern, and reduced echogenicity. Enlargement of the ALSDFT results in increased distance between the caudal aspect of the radius and the median artery. Injuries to the ALSDFT are often seen with other injuries either in the carpal canal, including superficial digital flexor (SDF) tendonitis or thickening of the flexor retinaculum, or elsewhere.10,11 These injuries include tenosynovitis of the flexor carpi radialis tendon sheath and suspensory desmitis.

Treatment consists of box rest and controlled exercise for up to 6 months, combined with intrathecal administration of hyaluronan and corticosteroids. The prognosis for horses with simple injuries is fair. Six of eight horses with uncomplicated desmitis of the ALSDFT returned to the former athletic function.10 However, horses with concurrent injuries were more likely to suffer recurrent lameness. Debridement of the torn ALSDFT using a tenoscopic approach combined with rest and intrathecal medication was successful in a trotter.9

Superficial Digital Flexor Tendonitis

Older horses (>15 years of age) and occasionally Standardbred racehorses may show acute SDF tendonitis within the carpal canal (see Chapter 69).2 In the acute stage, the carpal sheath is distended, but the horse may show no palpable abnormality of the SDFT in the metacarpal region or only slight peritendonous edema proximally. Diagnosis is based on ultrasonographic identification of lesions of the SDFT. In some horses, lesions may not be detectable acutely but may become apparent over the next several weeks. Some older horses initially show SDF tendonitis, which progresses proximally to involve the SDFT within the carpal sheath. These horses have a poor prognosis regardless of the method of management.

Younger horses may develop SDF tendonitis in the proximal metacarpal region. Such lesions may extend proximally into the carpal region, with only slight distention of the carpal sheath. A high proportion of these lesions result in recurrent lameness if treated conservatively. In horses with chronic tendonitis, surgical treatment by desmotomy of the ALSDFT combined with transection of the carpal retinaculum and proximal metacarpal fasciotomy should be considered (see Chapter 69). Moderate results have been achieved in a small number of racehorses and ponies.9

Injury of the Superficial Digital Flexor Tendon at the Musculotendonous Junction

Rupture of the SDFT at the musculotendonous junction is usually the result of a fall and is a catastrophic injury meriting humane destruction of the horse. There is rapid development of soft tissue swelling in the antebrachium. The horse is severely distressed and is unable to fully load the limb, and if it tries to do so there is abnormal sinking of the fetlock. Diagnosis is usually made based on the results of clinical examination.

Focal tears of the SDFT at the musculotendonous junction occur rarely and result in moderate to severe lameness associated with distention of the carpal sheath. Diagnosis is based on ultrasonographic examination,5 which may not be straightforward because the normal muscle tissue is anechogenic. Hematoma formation may be seen as a region of increased echogenicity. Careful comparison with the contralateral limb reveals that the tendon is enlarged, and there may be echogenic material extending from the tendon margins, reflecting tearing. Horses with low-grade lesions within the musculotendonous junction may respond favorably to conservative management but those with large tears warrant a more guarded prognosis. Surgical debridement, performed tenoscopically, has yielded disappointing results, with most horses remaining lame despite prolonged rest.

Injury of the Flexor Retinaculum

Primary injury of the flexor retinaculum is rare but does occasionally occur. More commonly, thickening and loss of echogenicity are seen ultrasonographically in association with other injuries, such as desmitis of the ALSDFT, carpal sheath tenosynovitis, or SDF tendonitis.

Deep Digital Flexor Tendonitis

Primary deep digital flexor (DDF) tendonitis within the carpal sheath is unusual, but marginal tears have been identified endoscopically in a small number of horses with persistent lameness associated with carpal sheath distention. Surgical debridement has resulted in clinical improvement. Secondary tears on the cranial aspect of the DDFT may occur with a solitary osteochondroma or a distal radial physeal exostosis (see the following sections). Carpal sheath distention with incomplete rupture of the cranial head of the DDFT has been reported.12 Hemorrhagic fluid was aspirated from the sheath, and disruption of the DDF muscle was identified by ultrasonography.

Occasionally DDF muscle injuries occur proximal to the carpal sheath, resulting in localized swelling and lameness. Ultrasonography is required for definitive diagnosis.5 Acute injuries result in a region of reduced echogenicity reflecting muscle tearing and hemorrhage, whereas a more chronic injury may be hyperechogenic reflecting hematoma formation or fibrosis. Off-incidence artifact can be used to differentiate between a hematoma and fibrosis.

Solitary Osteochondroma

An osteochondroma is an exostosis continuous with the cortex of the bone and is covered by cartilage. The distal caudal radius is a common site, immediately proximal to the distal radial physis. An osteochondroma is readily identifiable radiologically and by ultrasonography. Almost invariably an impingement lesion is found on the cranial aspect of the DDFT. Treatment is by surgical removal of the osteochondroma and debridement of any torn fibers of the DDFT. Treatment usually produces an excellent functional and cosmetic result.2

Distal Radial Physeal Exostoses

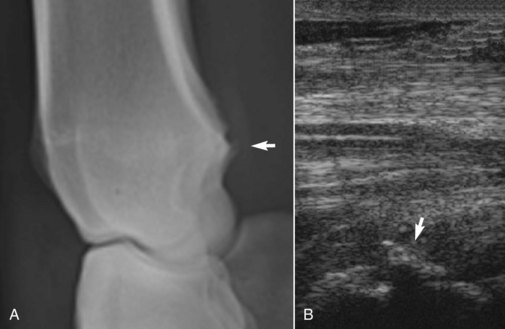

Small spikes or exostoses may develop on the distal caudal aspect of the radius at the level of the physis.11 These vary in size and have the potential to create tears in the cranial aspect of the DDFT (Figure 75-2). Importantly, it is the exostoses that occur on midline and not those that can be seen peripherally on oblique radiographic images that irritate and injure the DDFT. Careful examination of a dorsopalmar radiographic image of the carpus is required. Although some can be identified radiologically, others are only identified using ultrasonography. A typical history is of sporadic severe lameness that frequently resolves very rapidly (within hours). The carpal sheath may be mildly to moderately distended at the time of lameness, but in some horses there are no detectable localizing clinical signs, creating a diagnostic challenge. Surgical removal of the spike and debridement of torn tendon fibers usually yield an excellent prognosis.

Fig. 75-2 A, Lateromedial radiographic image of the distal radius of a 7-year-old Warmblood dressage horse with sporadic severe lameness, associated with distention of the carpal sheath. There is a physeal exostosis (arrow) on the caudodistal aspect of the radius that was impinging on the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT). B, Longitudinal ultrasonographic image of the carpal sheath obtained from the caudomedial aspect. Proximal is to the right. There is an exostosis (arrow) impinging on the DDFT.

Fractures of the Accessory Carpal Bone

Fractures of the accessory carpal bone are often the result of a fall and result in acute-onset, moderate to severe lameness (see Chapter 38). The majority have a vertical configuration.14,15 Reports are conflicting about the incidence of carpal canal syndrome secondary to a fibrous union or nonunion of the accessory carpal bone.14-16 Seven of 11 horses returned to full athletic function without complications after a vertical (frontal) fracture of the accessory carpal bone, despite healing by fibrous union in the six horses reexamined radiographically.15 The four remaining horses were sound: two were retired for breeding, and two were used for pleasure riding. I have had similar experience. However, if lameness associated with thickening of the carpal sheath wall persists, resection of a piece of the carpal retinaculum may be successful.14 Radiographs should be inspected carefully because occasionally chip fractures of the articular margin of the accessory carpal bone occur alone or concurrently with a more typical vertical fracture. Horses with such fractures warrant a more guarded prognosis. Small chip fractures may be removed surgically, but osteoarthritis of the antebrachiocarpal joint may rapidly ensue. Horses with severely comminuted fractures warrant a guarded prognosis.