Clinical Examination for Splinting

1 List components of a clinical examination for splinting.

2 Describe components of a history, an observation, and palpation.

3 Describe the resting hand posture.

4 Relate how skin, vein, bone, joint, muscle, tendon, and nerve assessments are relevant to splinting.

5 Identify specific assessments that can be used in a clinical examination before splinting.

6 Explain the three phases of wound healing.

7 Recognize the identifying signs of abnormal illness behavior.

8 Explain how a therapist can assess a person’s knowledge of splint precautions and wear and care instructions.

Clinical Examination

A thoughtfully selected battery of clinical assessments is crucial to therapists’ and physicians’ treatment plans. A thorough, organized, and clearly documented examination is the basis for the development of a treatment plan and splint design. In today’s health care system, a therapist completes examinations that are time and cost efficient. This chapter addresses components of the assessment in relationship to the splinting process.

Time-efficient informal assessments may indicate the level of hand function initially and the results may prompt the therapist to select more sophisticated testing procedures, as indicated by the person’s condition [Fess 1995]. Generally, initial and discharge evaluations are most comprehensive in scope, whereas regular reassessments are usually more focused.

Reassessments are typically conducted at consistent intervals of time. For example, if Joe is evaluated at his Monday appointment the therapist may reevaluate Joe every Monday or every other Monday thereafter. On some occasions, a case manager may request the therapist to reevaluate a client. However, the time span between assessments is based on the person’s condition and progress. For example, a person with a peripheral nerve injury may be reevaluated once every three weeks because of the slow nature of nerve healing. Another person being rehabilitated after a burn injury may be reevaluated every week because his condition changes more quickly, thereby affecting his functional ability.

The assessment process for the upper extremity should incorporate data from an interview, observation, palpation, and a selection of tests that are objective, valid, and reliable. Form 5-1 is a check-off sheet therapists can use when evaluating a person with upper extremity dysfunction.

History

Beginning with a medical history, the therapist gathers data from various sources. Depending on the setting, the therapist may have access to the person’s medical chart, surgical or radiologic reports, and the physician’s referral or prescription. The person’s age, gender, and diagnosis are typically easy to obtain from these sources. Client age is important because some congenital anomalies and diagnoses are unique to certain age groups. Age may also affect prognosis or length of recovery. Some problems are unique to gender.

From available sources, the therapist seeks out the person’s past medical history and the dates of occurrences, as well as current medical status and treatment. This includes invasive and noninvasive treatments. Conditions such as diabetes, epilepsy, kidney or liver dysfunction, arthritis, and gout should be reported because they can directly or indirectly influence rehabilitation (including splinting). The therapist determines whether the current upper extremity problem is the result of neurologic or orthopedic dysfunction or from an orthopedic problem or trauma affecting soft tissue (i.e., tendon laceration, burn). The nature of dysfunction helps the therapist determine the splinting approach.

With postoperative persons, therapists must know the anatomic structures involved and the surgical procedures performed. Therapists should be aware that physicians may prefer to follow conventional rehabilitative programs for certain diagnostic populations. Other physicians may prefer to follow different rehabilitative programs they have developed for specific postoperative diagnostic populations. Whether standardized or nonstandardized, these programs are known as protocols. Protocols delineate which types of splint, exercise, and therapeutic interventions are appropriate in rehabilitation programs. Protocols also indicate the timing of interventions.

Interview

The therapist collects the person’s history at the time of the initial evaluation. The goal of the interview is for the therapist to determine the impact of the condition on the person’s functioning, family, economic status, and social/emotional well-being. It is beneficial to complete introductions and explain what occupational therapy is and what the purpose of evaluation and treatment are at the beginning of the interview. In addition, the therapist should create a teaching/learning environment directed at the client’s learning style. For example, a therapist may tell a person that he or she should feel comfortable about asking any questions concerning therapy, evaluation, or treatment.

Co-histories are obtained from family, parents, friends, and caretakers of children and persons who are unable to communicate or who have cognitive impairments and are unreliable or questionable self-reporters. The therapist should obtain the following information by asking the person a variety of questions.

Therapists ask about general health as well as about any prior orthopedic, neurologic, psychologic, or cardiopulmonary conditions [Ellem 1995]. Habits and conditions such as smoking [Mosely and Finseth 1977, Siana et al. 1989], stress [Ebrecht et al. 2004], obesity [Wilson and Clark 2004], and depression [Tarrier et al. 2005] may influence rehabilitation [Ramadan 1997]. The therapist asks the client about any previous upper extremity conditions and their dates of onset in order to assess the current condition. The therapist inquires about any prior treatments and their results. The therapist can determine clients’ insight into their condition by asking them to describe what they understand about their condition.

Observation

Observations are noted immediately when the person walks into a clinic or during the first meeting between the therapist and client. For example, the therapist should observe how the person carries the upper extremity, looking for reduced reciprocal arm swing, guarding postures, and involuntary movements such as tremors or tics [Smith and Bruner 1998]. For example, facial tics may be a sign of a neurologic or psychological problem. Further information is gleaned from observing facial movements, speech patterns, and affect. For example, if there is a facial droop the therapist may suspect that the client has Bell’s palsy or has had a stroke. In addition, the therapist should always observe whether the person is able to answer questions and follow instructions.

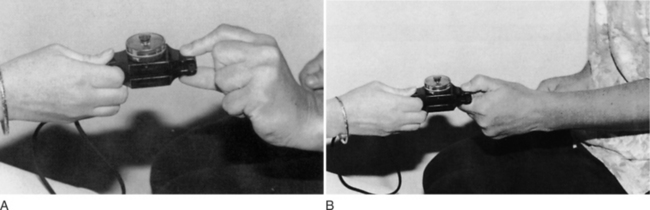

A general inspection of the person’s upper quarter (including the neck, shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist, and hand) is completed, and joint attitude is noted. The therapist notes the posture of the affected extremity and looks for any postural asymmetry and guarded or protective positioning. A normal hand at rest assumes a posture of 10 to 20 degrees of wrist extension, 10 degrees of ulnar deviation, slight flexion and abduction of the thumb, and approximately 15 to 20 degrees of flexion of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints. The fingers in a resting posture exhibit a greater composite flexion to the radial side of the hand (scaphoid bone), as shown inFigure 5-1 [Aulicino and DuPuy 1990]. The thumbnail usually lies perpendicular to the index finger. These hand postures are a useful basis for splint fabrication because a person’s hand often deviates from the normal resting posture when injury or disease is present.

Figure 5-1 (A) Normal resting posture of the hand. Note that the fingers are progressively more flexed from the radial aspect to the ulnar aspect of the hand. (B) This normal hand posture is lost because of contractures of the digits as a result of Dupuytren’s disease. (C) Loss of the normal hand posture is due to a laceration of the flexor tendons of the fifth digit. [From Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD (eds.), (1996). Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 55.]

A variety of presentations can be observed by the therapist and will contribute to the overall clinical picture of the person. The following are noteworthy observational points [Ellem 1995].

• Position of hand in relationship to the body: protective or guarding posture

• Diminished or absent reciprocal arm swing

• Finger pads: thin or smooth (loss of rugal folds, fingerprint lines)

• Lesions: scars, abrasions, burns, wounds

• Heberden’s or Bouchard’s nodes

• Neurologic deficit postures: claw hand, wrist drop, monkey hand

• External devices: percutaneous pins, external fixator, splints, slings, braces

• Deformities: boutonniere, mallet finger, intrinsic minus hand, swan neck

• Pilomotor signs: appearance of “goose pimples” or hair standing on end

Palpation

After a general inspection of the client, palpation of the affected areas is completed when appropriate. A therapist palpates any area in which the person describes symptoms, including any area that is swollen or abnormal [Smith and Bruner 1998]. Muscle bulk is palpated on each extremity to compare proximal and distal muscles, as well as to compare right and left. Muscle tone is best assessed through passive range of motion (PROM). When assessing tone, the therapist should coach the client to relax the muscles so that the most accurate results can be obtained. The client’s skin should be examined by the therapist. In the presence of ulcers, gangrene, inflammation, or neural or vascular impairment, skin temperature may change and can be felt during palpation [Ramadan 1997]. In the presence of infection, draining wounds, or sutured sites, therapists wear sterile gloves and follow universal precautions.

Assessments

Assessment selection is a critical step in formulating appropriate treatment interventions. There are more than 100 assessments in the musculoskeletal literature [Suk et al. 2005]. Several factors must be considered in selecting an assessment, including content, methodology, and clinical utility [Suk et al. 2005]. In order to critically choose assessment tools used for practice, one must understand the psychometric development of such tools.

Content of an assessment is what the tool is attempting to measure. Content can be separated into three categories: type, scale, and interpretation. The type of content can be focused on data gathered by the clinician or data reported by the client. The scale of the content refers to the measurements or questions that constitute the tool and how they are measured. Content interpretation addresses how scores or measures pertain to “excellent” or “poor” outcomes [Suk et al. 2005].

Methodology of the tool relates to validity, reliability, and responsiveness. Validity is the extent to which the assessment measures what it intends to measure.Table 5-1 lists and defines the various types of validity. Reliability is the consistency of the assessment.Table 5-2 lists and defines the types of reliability. Responsiveness refers to the assessment’s sensitivity to measure differences in status [Suk et al. 2005].

Table 5-1

Definitions of Types of Validity

| TYPE OF VALIDITY | DEFINITION |

| Construct validity | The degree to which a theoretical construct is measured by the tool |

| Content validity | The degree to which the items in a tool reflect the content domain being measured |

| Face validity | Determination if a tool appears to be measuring what it is intended to measure |

| Criterion validity | The degree to which a tool correlates with a “gold standard” or criterion test (it can be assessed as concurrent or predictive validity) |

| Concurrent validity | The degree to which the scores from a tool correlate with a criterion test when both tools are administered relatively at the same time |

| Predictive validity | The degree to which a measure will be a valid predictor of a future performance |

Table 5-2

Definitions of Types of Reliability

| TYPE OF RELIABILITY | DEFINITION |

| Inter-rater reliability | The degree to which two raters can obtain the same ratings for a given variable |

| Test/retest reliability | The degree to which a test is stable based on repeated administrations of the test to the same individuals over a specified time interval |

| Internal consistency | The degree to which each item of a test measures the same trait |

| Intra-rater reliability | The degree to which one rater can reproduce the same score in administering the tool on multiple occasions to the same individual |

Clinical utility refers to the degree the tool is easy to administer by the therapist and the degree of ease the client experiences in completing the assessment. Utility is a subjective component addressing the degree to which the tool is acceptable to the client and the degree to which the tool is feasible to the therapist. Factors that impact clinical utility include training on administration, cost and administration, documentation, and interpretation time [Suk et al. 2005].

Assessment tools can be categorized in several ways. There are standardized and nonstandardized assessment tools. Some assessments are norm based, whereas others are criterion based. Bear-Lehman and Abreu [1989] suggest that evaluation is a quantitative and qualitative process. Thus, therapists who select assessments that produce precise, objective, and quantitative measurement decrease subjective judgments and increase their ability to obtain reproducible findings. However, therapists are cautioned to reject the tendency to neglect important information about their clients that may not be quantifiable [Bear-Lehman and Abreu 1989]. Qualitative information—such as attitude, pain response, coping mechanisms, and locus of control (center of responsibility for one’s behavior)—influence the evaluation process. “The selection of the hand assessment tools to be used, the art of human interaction between the therapist and the client, the art of evaluating the client’s hand as a part, but also as an integrated whole, are part of the subjective processes involved in hand assessment” [Bear-Lehman and Abreu 1989, p. 1025]. Even objective evaluation tools require the comprehension and motivation of the client.

Unfortunately, there is no universally accepted upper extremity assessment tool. Depending on the setting, a battery of assessments may be developed by the facility or department. In other settings, therapists use their clinical reasoning to determine what battery of assessments will be used with each person. Therapists should keep in mind that a theoretical perspective as well as a diagnostic population can influence the evaluation selection [Bear-Lehman and Abreu 1989]. For example, one facility’s assessment reflects a biomechanical perspective whereas another facility’s assessment reflects a neurodevelopmental perspective.

The sections that follow explore common assessments performed as part of an upper extremity battery of evaluations. There is a gamut of assessments for particular conditions not presented in this text.

Pain

The therapist has several options for evaluating pain, including interview questions, rating scales, body diagrams, and questionnaires.Box 5-1 lists questions a therapist can ask the person in relationship to pain [Fedorczyk and Michlovitz 1995]. Therapists often use a combination of pain measures to obtain an accurate representation of the client’s pain [Kahl and Cleland 2005].

The Verbal Analog Scale (VeAS) can be used to determine the person’s perception of pain intensity. The person is asked to rate pain on a scale from 0 to 10 (0 refers to no pain and 10 refers to the worst pain ever experienced). Reliability scores for retesting under the VeAS are moderate to high, ranging from 0.67 to 0.96 [Good et al. 2001, Finch et al. 2002]. When correlated with the Visual Analog Scale (ViAS), the VeAS had a reliability score of 0.79 to 0.95 [Good et al. 2001, Finch et al. 2002]. Finch et al. [2002] reported that a three-point change in score is necessary to establish a true pain intensity change. Thus, the VeAS may be limited in detecting small changes, and clients with cognitive deficits may have trouble following instructions to complete the VeAS [Flaherty 1996, Finch et al. 2002].

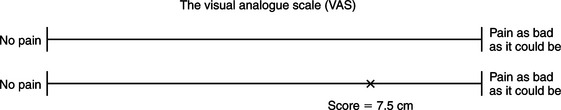

A ViAS can also be used to rate pain intensity. A person is asked to look at a 10-cm horizontal line. The left side of the line represents “no pain” and the right side represents “pain as bad as it could be.” The person indicates pain level by marking a slash on the line, which represents the pain experienced. The distance from no pain to the slash is measured and recorded in centimeters (Figure 5-2). The ViAS “may have a high failure rate because patients may have difficulty interpreting the instructions” [Weiss and Falkenstein 2005, p. 63]. Errors can occur due to changes in length of the line resulting from photocopying [Kahl and Cleland 2005]. Both VeAS and ViAS are unidimensional assessments of pain (i.e., intensity) [Kahl and Cleland 2005]. Although test-retest is not applicable to self-reported measures, studies have demonstrated a high range of test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.71 to 0.99) [Enebo 1998, Good et al. 2001, Finch et al. 2002]. When compared to the VaAS, concurrent validity measures ranged from 0.71 to 0.78 [Enebo 1998].

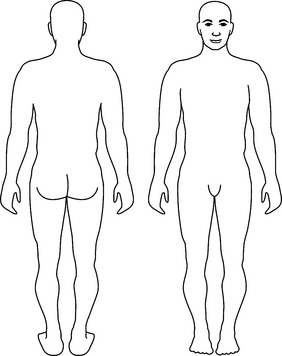

A body diagram consists of outlines of a body with front and back views, as shown inFigure 5-3. The person is asked to shade or color in the location of pain that corresponds to the body part experiencing pain. Colored pencils corresponding to a legend can be used to represent different intensities or types of pain, such as numbness, pins and needles, burning, aching, throbbing, and superficial.

Therapists may choose to use a more formal assessment, such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) [Fedorczyk and Michlovitz 1995] or the Schultz Pain Assessment [Weiss and Falkenstein 2005]. Although formal assessments usually take more time to administer than screening tools, they comprehensively assess many aspects of pain [Ross and LaStayo 1997].

Melzack [1975] developed the MPQ, which is widely used in clinical practice and for research purposes. The MPQ consists of a pain rating index, total number of word descriptors, and a present pain index. In its original version, the MPQ required 10 to 15 minutes to administer. The MPQ is a valid and reliable assessment tool. High internal consistency within the MPQ was demonstrated, with correlations of 0.89 to 0.90 [Melzack 1975]. Test-retest reliability scores for the MPQ are reported as 70.3% [Melzack 1975].

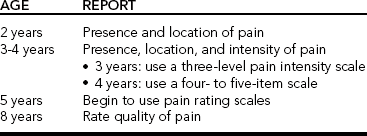

For assessment of pediatric pain, self-reporting measures are considered the gold standard [O’Rourke 2004]. A therapist must determine the child’s concepts of quantification, classification, and matching prior to administering simple pain intensity scales [Chapman et al. 1998]. Nonverbal scales using facial expressions and the ViAS are commonly used. Children can report pain according to various aspects of child development.Table 5-3 outlines ages and recommendations associated with the various types of reporting in children.

Skin

A thorough examination of the surface condition and contour of the extremity may define possible pathologic conditions, which may influence splint design. During the examination the therapist observes and documents the skin’s color, temperature, and texture. The therapist also observes the skin for muscle atrophy, scarring, edema, hair patterns, sweat patterns, and abnormal masses. Persons having fragile skin (especially persons who are older, who have been taking steroids for a long time, or who have diabetes) require careful monitoring. For these persons, the therapist carefully considers the splinting material so as to prevent harm to the already fragile skin (see Chapter 15).

With regard to skin, many clients are aware of skin allergies they have. Some are allergic to bandages, adhesive, and latex (all of which can be used in the splinting process). To avoid skin reactions, the therapist should ask each client to disclose any types of allergy before choosing splinting materials. When persons are unsure of skin allergies, the therapist should be aware that thermoplastic material, padding, and strapping supplies may create an allergic reaction. Therapists educate persons to monitor for any rashes or other skin reactions that develop from wearing a splint. The client experiencing a reaction should generally discontinue wearing the splint and report immediately to the therapist.

Veins and Lymphatics

Normally the veins on the dorsum of the hand are easy to see and palpate. They are cordlike structures. Any tenderness, pain, redness, or firmness along the course of veins should be noted [Ramadan 1997]. Venous thrombosis, subcutaneous fibrosis, and lymphatic obstruction will cause edema [Neviaser 1978].

Wounds

The therapist measures wounds or incisions (usually in centimeters) and assesses discharge from wounds for color, amount, and odor. If there is concern about the discharge being a sign of infection, a wound culture is obtained by the medical staff to identify the source of infection, and appropriate medication is prescribed. Wounds can be classified by color: black, yellow, or red [Cuzzell 1988]. A black wound consists of dark, thick eschar, which impedes epithelialization. A yellow wound may range in color from ivory to green-yellow (e.g., colonization with pseudomonas). Typically, yellow wounds are covered with purulent discharge. A red wound indicates the presence of granulation tissue and is normal.

Many wounds consist of a variety of colors [Cuzzell 1988]. Treatment focuses on treating the most serious color initially. For example, in the presence of eschar (commonly seen after thermal and crush injuries) a wound takes on a white or yellow-white color. Part of the treatment regimen for eschar is mechanical, chemical, or surgical debridement, which usually must be done before splinting. Debridement may result in a yellow wound. The yellow wound is managed by cleansing and dressing techniques to assist in the removal of debris. Once the desired red wound bed is achieved, it is protected by dressings [Walsh and Muntzer 1992].

Because open wounds threaten exposure to the person’s body fluids, the therapist follows universal precautions. The following precautions were derived from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) [Singer et al. 1995].

• Gloves are worn for all procedures that may involve contact with body fluids.

• Gloves are changed after contact with each person.

• Masks are worn for procedures that may produce aerosols or splashing.

• Protective eyewear or face shields are worn for procedures generating droplets or splashing.

• Gowns or aprons are worn for procedures that may produce splashing or contamination of clothing.

• Hands are washed immediately after removal of gloves, after contact with each person.

• Torn gloves are replaced immediately.

• Gloves are replaced after punctures, and the instrument of puncture wounds is discarded.

• Areas of skin are cleansed with soap and water immediately if contaminated with blood or body fluids.

• Mouthpieces, resuscitation bags, and other ventilatory devices must be available for resuscitation to reduce the need for mouth-to-mouth resuscitation techniques.

• Extra care is taken when using sharps (especially needles and scalpels).

• All used disposable sharps are placed in puncture-resistant containers.

Many upper extremity injuries result in wounds, whether from trauma or surgery. Therefore, therapists must know the stages of wound healing. The healing of wounds is a cellar process [Evans and McAuliffe 2002]. Experts have identified three overlapping stages [Staley et al. 1988, Smith 1990], which consist of the (1) inflammatory or epithelialization, (2) proliferative or fibroblastic, and (3) maturation and remodeling phases [Smith 1990, 1995; Evans and McAuliffe 2002].

The first stage is the inflammatory (epithelialization) phase (Staley et al. 1988, Smith 1990, 1995], which begins immediately after trauma and lasts three to six days in a clean wound. Vasoconstriction occurs during the first 5 to 10 minutes of this stage, leading to platelet adhesion of the damaged vessel wall and resulting in clot formation. This activity stimulates fibroblast proliferation. During the inflammatory phase for a repaired tendon, cells proliferate on the outer edge of the tendon bundles during the first four days [Smith 1992]. By day seven, these cells migrate into the substance of the tendon. In addition, there is vascular proliferation within the tendon, which provides the basis for intrinsic tendon healing [DeKlerk and Jouck 1982]. Extrinsic repair of the tendon occurs when the adjacent tissues provide collagen-producing fibroblasts and blood vessels [Lindsay 1987]. Fibrovascular tissue that infiltrates from tissues surrounding the tendon can become future adhesions. Adhesions will prevent tendon excursion if allowed to mature with immobilization [Smith 1992].

The second stage is the proliferative (fibroblastic) phase, which begins two to three days after the injury and lasts about two to six weeks [Staley et al. 1988, Smith 1990, 1995]. During this stage, epithelial cells migrate to the wound bed. Fibroblasts begin to multiply 24 to 36 hours after the injury. The fibroblasts initiate the process of collagen synthesis [Evans and McAuliffe 2002]. The fibers link closely and increase tensile strength. A balanced interplay between collagen synthesis and its remodeling and reorganization prevents hypertrophic scarring. During tendon healing, the proliferative phase begins by day seven and is marked by collagen synthesis [Smith 1992]. In a tendon repair where there is no gap between the tendon ends, collagen appears to bridge the repair [Smith 1992]. Collagen fibers and fibroblasts are initially oriented perpendicularly to the axis of the tendon. However, by day 10 the new collagen fibers begin to align parallel to the longitudinal collagen bundles of the tendon ends [Lindsay 1987].

The final stage is the maturation (remodeling) phase, which can last up to one or two years after the injury [Staley et al. 1988; Smith, 1990, 1995]. During this stage the tensile strength continues to increase. Initially, the scar may appear red, raised, and thick, but with maturation a normal scar softens and becomes more pliable. The maturation phase for healing tendons is lengthier than time needed for skin or muscle because the blood supply to the tendons is much less [Smith 1992]. Tendon strength increases in a predictable fashion [Smith 1992]. Smith [1992] points out that in 1941 Mason and Allen first described how tensile strength of a repaired tendon progresses. From 3 to 12 weeks after tendon repair, mobilized tendons appear to be twice as strong as immobilized tendons. At 12 weeks, immobilized tendons have approximately 20% of normal tendon strength. In comparison, mobilized tendons at 12 weeks have 50% of normal tendon strength.

Bone

When assessing a person who has a skeletal injury, the therapist reviews the surgery and radiology reports. The therapist places importance on knowing the stability level of the fracture reduction, the method the physician used to maintain good alignment, the amount of time since the fracture’s repair, and fixation devices still present in the upper extremity. A physician may request that the therapist fabricate a splint after the fracture heals. On occasion, the therapist may fabricate a custom splint or use a commercial fracture brace to stabilize the fracture before healing is complete. For example, for a person with a humeral fracture a commercially available humeral cuff may be prescribed.

The rationale for using a commercially fabricated fracture brace rather than fabricating a custom splint is based on time, client comfort, ease of application, and cost. Custom fabrication of fracture braces can be challenging because the client is typically in pain and the custom splint involves the use of large pieces of thermoplastic material, which can be difficult to control. The commercial fracture brace saves the therapist’s time and therefore minimizes expense. A commercial brace also minimizes donning and doffing for fitting, which can also be uncomfortable for the client. Indications for fabricating a custom fracture brace may include bracing extremely small or large extremities.

Joint and Ligament

Joint stability is important to assess and is evaluated by carefully applying a manual stress to any specific ligament. Each digital articulation achieves its stability through the collateral ligaments and a dense palmar plate [Cailliet 1994]. The therapist should carefully assess the continuity, length, and glide of these ligaments. Joint play or accessory motion of a joint is assessed by grading the elicited symptoms upon passive movement. The grading system is as follows: 0 = ankylosis, 1 = extremely hypomobile, 2 = slightly hypomobile, 3 = normal, 4 = slightly hypermobile, 5 = extremely hypermobile, and 6 = unstable [Wadsworth 1983]. Unstable joints, subluxations, dislocations, and limited PROM directly affect splint application. Lateral stress on finger joints should be avoided. In addition, the person may wear a splint to prevent unequal stress on the collateral ligaments [Cannon et al. 1985].

Muscle and Tendon

Tensile strength is the amount of long-axis force a muscle or tendon can withstand [Fess et al. 2005]. When a tendon is damaged or undergoes surgical repair, tensile strength directly affects the amount of force a splint should provide. Tensile strength also mandates which exercises or activities the person can safely perform.

Therapists should keep in mind that proximal musculature can affect distal musculature tension in persons experiencing spasticity. For example, wrist position can influence the amount of tension placed on finger musculature. When the therapist is attempting to increase wrist extension in the presence of spasticity, the wrist, hand, and fingers must be incorporated into the splint’s design. If the splint design addresses only wrist extension, the result may be increased finger flexion. Conversely, if the splint design addresses only the fingers, the wrist may move into greater flexion (see Chapter 14).

Nerve

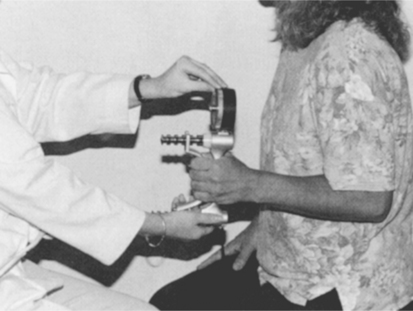

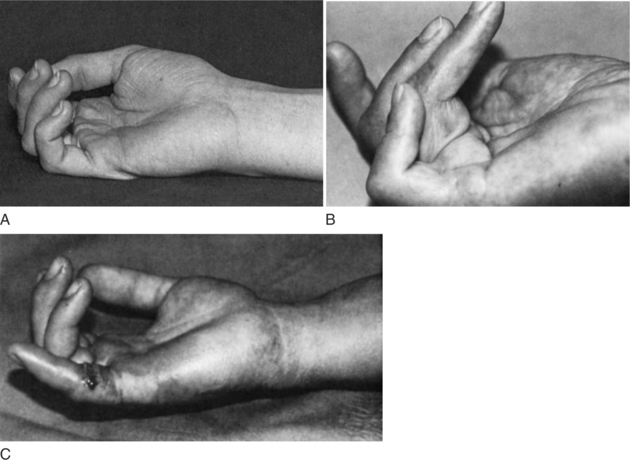

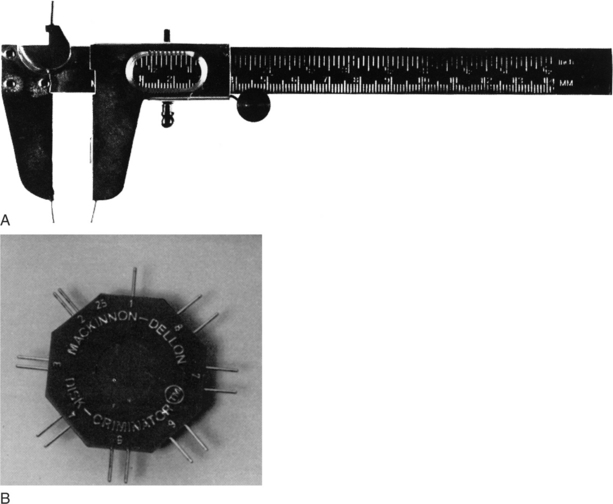

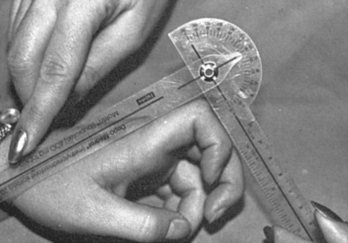

Sensory evaluations are important to determine areas of diminished or absent sensibility. Conventional tests for protective sensibility include the sharp/dull and hot/cold assessments. Discriminatory sensibilities include assessment for stereognosis, proprioception, kinesthesia, tactile location, and light touch. Aulicino and DuPuy [1990] recommend two-point discrimination testing (Figure 5-4) as a quick screening for sensibility. In addition, the American Society for Surgery of the Hand recommends static and moving two-point discrimination tests. The Semmes-Weinstein Monofilament test (Figure 5-5) provides useful detailed mapping of the level of functional sensibility, particularly during rehabilitation of peripheral nerve injury. This mapping is useful to physicians, therapists, clients, case managers, and employers [Tomancik 1987]. The Semmes-Weinstein Monofilament test is the most reliable sensation test available and is often used as the comparison for concurrent validity studies [Dannenbaum et al. 2002].

Figure 5-4 The recommended instruments for testing two-point discrimination include the Boley Gauge (A) and the Disk-Criminator (B). [From Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD (eds.), (1996). Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 146.]

Figure 5-5 The monofilament collapses when a force dependent on filament diameter and length is reached, controlling the magnitude of the applied touch pressure. [From Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD (eds.), (1996). Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 76.]

Therapists searching for objective sensory assessment data should be aware that “tests that were considered objective in the past can be demonstrated to be subjective in application dependent on the technique of the examiner” [Bell-Krotoski 1995, p. 109; Bell-Krotoski and Buford 1997]. For example, when administering the Semmes-Weinstein Monofilament test if the stimulus is applied too quickly “the force can result in an overshoot beyond the desired stimulus” [Bell-Krotoski and Buford 1997, p. 304] and affect the test results. In addition, even when the Semmes-Weinstein Monofilament test is administered with excellent technique the cooperation and comprehension of the client are required.

When peripheral nerve injuries have occurred or are suspected, a Tinel’s test can be conducted. Tinel’s test can be performed in two ways. The first method involves gently tapping over the suspected entrapment site to help determine whether entrapment is present. The second method consists of tapping the nerve distal to proximal. The location where the paresthesias are felt is considered the level to which a nerve has regenerated after Wallerian degeneration has occurred. A person is said to have a positive Tinel’s sign if he or she experiences tingling or shooting sensations in one of two areas: at the site of tapping or in a direction distally from the tapped area [Ramadan 1997]. If the person experiences paresthesia or hyperparesthesia in a direction proximal to the tapped area, the Tinel’s test is negative.

A Phalen’s sign is present if a person feels similar symptoms when resting elbows on the table while flexing the wrists for 1 minute [American Society for Surgery of the Hand 1983]. Phalen’s sign may indicate a median nerve problem. One should be aware that Tinel’s and Phalen’s signs can be positive in normal subjects [Smith and Bruner 1998].

Cervical nerve problems must be ruled out before a diagnosis of peripheral nerve injury can be made. For example, a person may have signs similar to carpal tunnel syndrome in conjunction with complaints of neck pain. In the absence of a cervical nerve screen, the person may have a misdiagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome but actually have cervical nerve involvement. In the absence of electrical studies, many surgeons still make the diagnosis of nerve compression.

During the fitting process, hand splints may cause pressure and friction on vulnerable areas with impaired sensibility. If a person has decreased sensibility, the therapist uses a splint design with long, well-molded components. The reason for using such a splint is to distribute the forces of the splint over as much surface area as possible, thereby decreasing the potential for pressure areas.

When splinting occurs across the wrist, the superficial branch of the radial nerve is at risk of compression. If the radial edge of the forearm splint stops beyond the mid-lateral forearm near the dorsum of the thumb, the superficial branch of the radial nerve can be compressed [Cannon et al. 1985]. During the evaluation of splint fit, therapists should be aware of the signs of compression of the superficial branch of the radial nerve. Splints that cause compression require adjustments to decrease the pressure near the dorsum of the thumb.

Vascular Status

To understand the vascular status of a diseased or injured hand, the therapist monitors the skin’s color and temperature and checks for edema. The therapist clearly defines areas of questionable tissue viability and adapts splints to prevent obstruction of arterial and venous circulation. To assess radial and ulnar artery patency, the therapist uses Allen’s test [American Society for Surgery of the Hand 1983].

A therapist can take circumferential measurements proximal and distal to the location of a splint’s application. Then, after applying the splint to the extremity the therapist measures the same areas and compares them with the previous measurements. An increase in measurements taken while the splint is on indicates that the splint is exerting too much force on the underlying tissues. This situation poses a risk for circulation. When fluctuating edema is present, the therapist should make the splint design larger. A well-fitting circumferential splint, sometimes in conjunction with a pressure garment, can control or eliminate fluctuating edema. In addition, fluctuating edema may signal poor compliance with elevation. A sling and education about its use may assist in edema control.

The therapist can also use the Fingernail Blanch Test to assess circulation [Aulicino and DuPuy 1990]. Long-lasting blanched areas of the fingertips indicate restricted circulation.

When a therapist applies a splint to the upper extremity, the skin should maintain its natural color. Red or purple areas indicate obstructed venous circulation. Dusky or white areas indicate obstructed arterial circulation. Splints causing circulation problems must be modified or discontinued.

Range of Motion and Strength

The therapist records active and passive motions when no contraindications are present (Figure 5-6), and takes measurements on both extremities for a baseline data comparison. The therapist also records total active motion (TAM) and total passive motion (TPM) [American Society for Surgery of the Hand 1983]. Grasp and pinch strengths are completed and documented only when no contraindications are present (Figures 5-7 and 5-8). Manual muscle testing (MMT) assesses muscle strength but should be done only when there are no contraindications. For example, if a person with rheumatoid arthritis in an exacerbated state is being evaluated, MMT should be avoided to prevent further exacerbation of pain and swelling.

Figure 5-6 Goniometric measurements of active and passive motion are taken regularly when no contraindications are present. [From Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD (eds.), (1996). Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 34.]

Coordination and Dexterity

Hand coordination and dexterity are needed for many functional performance tasks, and it is important to evaluate them. Many standardized tests for coordination and dexterity exist, including the Nine Hole Peg Test (Figure 5-9), the Minnesota Rate of Manipulation Test, the Crawford Small Parts Dexterity Test, the Purdue Peg Board Test, the Rosenbusch Test of Dexterity, and the Valpar Tests. Most dexterity tests are based on time measurements, and normative data are available for all of these tests. In particular, the Valpar work samples use methods time measurement (MTM). MTM is a method of analyzing work tasks to determine how long a trained worker will require to complete a certain task at a rate that can be sustained for an eight-hour workday.

Figure 5-9 The Nine Hole Peg Test is a quick test for coordination. [From Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD (eds.), (1996). Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 1158.]

The Sequential Occupational Dexterity Assessment (SODA) was developed in the Netherlands [Van Lankveld et al. 1996]. The SODA is a test to measure hand dexterity and the client’s perception of difficulty and pain while performing four unilateral and eight bilateral activities of daily living (ADL) tasks [Massey-Westropp et al. 2004]. In a study conducted by Massey-Westropp et al. [2004] on 62 clients with rheumatoid arthritis, they concluded that “The SODA is also valid and reliable for assessing disability in a clinical situation that cannot be generalized to the home” (p. 1996). More research should be conducted to test such findings.

Function

Function can be assessed by observation, interview, task performance, and standardized testing. Close observation during the interview and splint fabrication gives the therapist information regarding the person’s views of the injury and disability. The therapist also observes the person for protected or guarded positioning, abnormal hand movements, muscle substitutions, and pain involvement during functional tasks. During evaluation, the person’s willingness for the therapist to touch and move the affected extremity is noted.

During the initial interview, the therapist questions the person about the status of ADL, instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and avocational and vocational activities. The therapist notes problem areas. Having clients perform tasks as part of an evaluation may result in more information, particularly when self-reporting is questioned by the therapist.

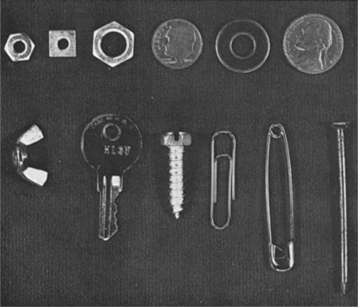

The therapist may use standardized hand function assessments. The Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function Test (Figure 5-10) is helpful because it gives objective measurements of standardized tasks with norms the therapist uses for comparison [Jebsen et al. 1969]. The Dellon modification of the Moberg Pick-up Test evaluates hand function when the person grasps common objects (Figure 5-11) [Moberg 1958]. Similar objects in the test require the person to have sensory discrimination and prehensile abilities [Callahan 1990].

Figure 5-10 The Jebsen-Taylor Hand Test assesses the ability to perform prehension tasks. [From Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD (eds.), (1996). Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 98.]

Figure 5-11 Items used in the Dellon modification of the Moberg Pick-up Test. [From Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD (eds.), (1990). Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Third Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, p. 608.]

Other functional outcome assessments that may be used include the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM); the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS); the Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH), and the Short Form-36 (SF-36).

The COPM is a client-centered outcome measure used to assess self-care, productivity, and leisure [Law et al. 1990]. Clients rate their performance and satisfaction with performance on a 1 to 10 point scale. The result is a weighted individualized client goal plan (Law et al. 1998). It is a top-down assessment, which is done before administration of tests to evaluate performance components. Test-retest reliability was reported as ICC = 0.63 for performance and ICC = 0.84 for satisfaction (as cited in Case-Smith, 2003) (Sanford et al. 1994). “Validity was estimated by correlating COPM change scores with changes in overall function as rated by caregivers (r = 0.55, r = 0.56), therapist (r = 0.30, r = 0.33), and clients (r = 0.26, r = 0.53)” (Case-Smith, 2003, p. 501).

The DASH is a standardized questionnaire rating disability and symptoms related to upper extremity conditions. The DASH includes 30 pre-determined questions that explore function within performance areas. The client rates on a scale of 1 (no difficulty) to 5 (unable) his or her current ability to complete particular skills, such as opening a jar or turning a key. Beaton, Katz, Fossel, Wright, Tarasuk and Bombardier (2001) studied reliability and validity of the DASH. Excellent test-retest reliability was reported (ICC = 0.96) in a study of 86 clients. Concurrent validity was established with correlations with other pain and function measures (r > 0.69).

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) measures eight aspects of health that contribute to quality of life [Ware et al. 2000]. The SF-36 “yields an eight scale profile of functional health and well being scores, as well as psychometrically based physical and mental health summary measures and a preference based health utility index” [Ware 2004, p. 693]. Reliability scores range from r = 0.43 to r = 0.96 [Brazier et al. 1992]. Evidence of content, concurrent, criterion, construct, and predictive evidence of validity have been established [Ware 2004]. The tool has been translated for use in more than 60 countries and languages.

Both the COPM and AMPS may take more time to administer than screening tools. However, the assessments are focused on functional performance. In addition, therapists using these tests should be trained in their administration, scoring, and interpretation.

Work

Evaluations of paid and unpaid work entail assessment of the work to be done and how the work is performed [Mueller et al. 1997]. It is estimated that 36% of all functional capacity evaluations (FCEs) are conducted because of upper extremity and hand injuries [Mueller et al. 1997]. Some facilities use a specific type of FCE system, such as the Blankenship System or the Key Method. Standardized testing includes the Work Evaluations Systems Technologies II (WEST II), the EPIC Lift Capacity (ELC), the Bennett Hand Tool Dexterity Test, the Purdue Pegboard, the Minnesota Rate of Manipulation Test (MRMT), and the Valpar Component Work Samples (VCWS). Commercially available computerized tests can be administered in work evaluations. Isometric, isoinertional, and isokinetic tests can be performed on equipment tools manufactured by Cybex, Biodex, and Baltimore Therapeutic Equipment (BTE). FCEs frequently assess abnormal illness behavior and often include observation, psychometric testing, and physical or functional testing. New and experienced therapists should have specialized training in administering and interpreting FCEs because of the standardized nature of the examination and the legal implications of these assessments [Mueller et al. 1997].

Other Considerations

The person’s motivation, ability to understand and carry out instructions, and compliance may affect the type of splint the therapist chooses. The therapist considers a person’s vocational and avocational interests when designing a splint. Some persons wear more than one splint throughout the day to allow for completion of various activities. In addition, some persons wear one splint design during the day and a different design at night.

Related to motivation may be the presence or absence of a third-party reimbursement source. Whenever possible, the therapist discusses reimbursement issues with the client before completing the initial visit. If a third party is paying for the client’s services, the therapist first determines whether that source intends to pay for any or all of the splint fabrication services. At times, some clients will be very motivated to comply with the rehabilitation program if they have to pay for the services. In other cases, where third-party reimbursement is quite good and the client is temporarily on a medical leave from work, the client may be less motivated and perhaps show signs of abnormal illness behavior. Terms such as malingering, secondary gain, hypochondriases, hysterical neurosis, conversion, somatization disorder, functional overlay, and nonorganic pain have been used to describe abnormal illness behaviors [Mueller et al. 1997]. Gatchel et al. [1986] reported the following red flags, which can assist the therapist in identifying such abnormal behaviors [Blankenship 1989].

• Client agitates other clients with disruptive behaviors

• Client has no future work plan or changes to previous work plan

• Client is applying for or receiving Social Security or long-term disability

• Client opposes psychological services and refuses to answer questions or fill out forms

• Client has obvious psychosis

• Client has significant cognitive or neuropsychological deficits

• Client expresses excessive anger at persons involved in case

• Client is a substance abuser

• Client’s family is resistant to his or her recovery or return to work

• Client has young children at home or has a short-term work history for primarily financial reasons

• Client perpetually complains about the facility, staff, and program rather than being willing to deal with related physical and psychological issues

• Client is chronically late to therapy and is noncompliant, with excuses that do not check out

• Client focuses on pain complaints in counseling sessions rather than dealing with psychological issues

Splinting Precautions

During the splint assessment, the therapist must be aware of splinting precautions. An ill-fitting splint can harm a person. Several precautions are outlined in Form 5-2, which a therapist can use as a check-off sheet. The therapist must not only educate a client about appropriate precautions but evaluate the client’s understanding of them. The client’s understanding can be assessed by having him or her repeat important precautions to follow or by role-playing (e.g., if this happens, what will you do?). In follow-up visits, the client can be questioned again to determine whether precautions are understood. Form 5-3 lists splint fabrication hints to follow. Adherence to the hints will assist in avoiding situations that result in clients experiencing problems with their splints.

Pressure Areas

After fabricating a splint, the therapist does not allow the person to leave until the splint has been evaluated for problem areas. A general guideline is to have the person wear the splint at least 20 to 30 minutes after fabrication. Red areas should not be present 20 minutes after removal of the splint. Splints often require some adjustment. After receiving assurance that no pressure areas are present, the therapist instructs the person to remove the splint and to call if any problems arise. Persons with fragile skin are at high risk of developing pressure areas. The therapist provides the person with thorough written and verbal instructions on the wear and care of the splint. The instructions should include a phone number for emergencies. During follow-up visits, the therapist inquires about the splint’s fit to determine whether adjustments are necessary in the design or wearing schedule.

Edema

The therapist completes an evaluation for excessive tightness of the splint or straps. Often edema is caused by inappropriate strapping, especially at the wrist or over the MCP joints. Strapping systems should be evaluated and modified if they are contributing to increased edema. If the splint is too narrow, it may also inadvertently contribute to increased edema. Persons can usually wear splints over pressure garments if necessary. However, therapists should monitor circulation closely.

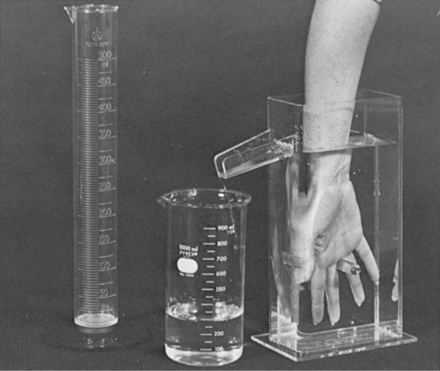

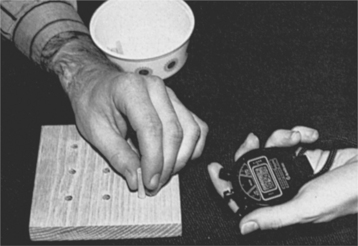

The therapist assesses edema by taking circumferential or volumetric measurements (Figure 5-12). When taking volumetric measurements, the therapist administers the test according to the testing protocol and then compares the involved extremity measurement with that of the uninvolved extremity. If edema fluctuates throughout the day, it is best to fabricate the splint when edema is present so as to ensure that the splint will accommodate the edema fluctuation. When edema is minimal but fluctuates during the day, the splint design must be wider to accommodate the edema [Cannon et al. 1985].

Splint Regimen

Upon provision of a splint, the therapist determines a wearing schedule for the client. Most diagnoses allow persons to remove the splints for some type of exercise and hygiene. The therapist provides a written splint schedule and reviews the schedule with the person, nurse, and caregiver responsible for putting on and taking off the splint. If the person is confused, the therapist is responsible for instructing the appropriate caregiver regarding proper splint wear and care. The therapist must evaluate the client or caregiver’s understanding of the wearing schedule.

Clients wearing mobilizing (dynamic) splints should follow several general precautions. A therapist must be cautious when instructing a client to wear a mobilizing (dynamic) splint during sleep. Because of moving parts on mobilization splints, the person could accidentally scratch, poke, or cut himself or herself. Therefore, therapists must design splints with no sharp edges and must consider the possibility of using elastic traction (see Chapter 11).

Typically, persons should wear mobilizing (dynamic) splints for a few minutes out of each hour and gradually work up to longer time periods. As with all splints, a therapist never fabricates a mobilizing (dynamic) splint without checking its effect on the person. The therapist also considers the diagnosis and appropriately schedules splint wearing. Often, but not always, a splint regimen will allow for times of rest, exercise, hygiene, and skin relief. The therapist considers the client’s daily activity schedule when designing the splint regimen. However, treatment goals must sometimes supersede the desire for the client to perform activities. In addition, the therapist uses clinical judgment to determine and adjust the splint-wearing schedule and reevaluates the splint consistently to alter the treatment plan as necessary.

Compliance

On the basis of the initial interview and statements from conversations, the therapist must determine whether compliance with the wearing schedule and rehabilitation program is a problem. (Chapter 6 contains strategies to help persons with compliance and acceptance.) If the hand demonstrates that the splint is not achieving its goal, the therapist must check that the splint is well designed and fits properly and then determine whether the splint is being worn. If the therapist is certain about the design and fit, compliance is probably poor. Clients returning for follow-up visits must bring their splints. The therapist can generally determine whether a client is wearing the splint by looking for signs of normal wear and tear. Signs include dirty areas or scratches in the plastic, soiled straps, and nappy straps (caused by pulling the strap off the Velcro hook).

Splint Care

Therapists are responsible for educating persons about splint care. An evaluation of a person’s understanding of splint care must be completed before the client leaves the clinic. Assessment is accomplished by asking the client to repeat instructions or demonstrate splint care. To keep the splint clean, washing the hand with warm water and a mild soap and cleansing the splint with rubbing alcohol are effective. The person or caregiver should thoroughly dry the hand and splint before reapplication. Chlorine occasionally removes ink marks on the splint. Rubbing alcohol, chlorine bleach, and hydrogen peroxide are good disinfectants to use on the splint for infection control.

Persons should be aware that heat may melt their splints and should be careful not to leave their splints in hot cars, on sunny windowsills, or on radiators. Therapists should discourage persons from making self-adjustments, including the heating of splints in microwave ovens (which may cause splints to soften, fold in on themselves, and adhere). If the person successfully softens the plastic, a burn could result from the application of hot plastic to the skin. However, clients should be encouraged to make suggestions to improve a splint. Therapists, especially novice therapists, tend to ignore the client’s ideas. Not only does this send a negative message to the client but clients often have wonderful ideas that are too beneficial to discount.

Summary

Evaluation before splint provision is an integral part of the splinting process. The evaluation process includes report reading, observation, interview, palpation, and formal and informal assessments. Evaluation before, during, and after splint provision results in the therapist’s ability to understand how the splint affects function and how function affects the splint. A thorough evaluation process ultimately results in client satisfaction.

1. What are components of a thorough hand examination before splint fabrication?

2. What is the posture of a resting hand?

3. What information should a therapist obtain about the person’s history?

4. What sources can therapists use to obtain information about persons and their conditions?

5. What should a therapist be noting when palpating a client?

6. What observations should be made when a client first enters a clinic?

7. What types of formal upper extremity assessments for function are available?

8. What procedure can a therapist use when assessing whether a newly fabricated splint fits well on a person?

9. What precautions should a therapist keep in mind when designing and fabricating a splint?

10. How can a therapist evaluate a client’s understanding of a splint-wearing schedule?

11. What safeguard can a therapist employ to avoid skin reactions from splinting materials?

References

American Society for Surgery of the Hand. The Hand. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1983.

Aulicino, PL, DuPuy, TE. Clinical examination of the hand. In Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Third Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1990.

Bear-Lehman, J, Abreu, BC. Evaluating the hand: Issues in reliability and validity. Physical Therapy. 1989;69(12):1025–1031.

Beaton, DE, Katz, JN, Fossel, AH, Wright, JG, Tarasuk, V, Bombardier, C. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2001;14(2):128–146.

Bell-Krotoski, JA. Sensibility testing: Current concepts. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

Bell-Krotoski, JA, Buford, WL. The force/time relationship of clinically used sensory testing instruments. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1997;10(4):297–309.

Blankenship, KL. The Blankenship System: Functional Capacity Evaluation, The Procedure Manual. Macon, GA: Blankenship Corporation, Panaprint, 1989.

Brazier, JE, Harper, R, Jones, N, O’Cathain, A, Thomas, KJ, Usherwood, T. Validating the SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. British Medical Journal. 1992;305:160–164.

Cailliet, R. Hand Pain and Impairment, Fourth Edition. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1994.

Callahan, AD. Sensibility testing: Clinical methods. In Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Macklin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Third Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1990.

Cannon, NM, Foltz, RW, Koepfer, JM, Lauck, MF, Simpson, DM, Bromley, RS. Manual of Hand Splinting. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1985.

Chapman, GD, Goodenough, B, von Baeyer, C, Thomas, W. Measurement of pain by self-report. In: Finley GA, McGrath PJ, eds. Measurement of Pain in Infants and Children. Seattle: IASP Press; 1998:123–160.

Cuzzell, JZ. The new RYB color code: Next time you assess an open wound, remember to protect red, cleanse yellow and debride black. American Journal of Nursing. 1988;88(10):1342–1346.

Dannenbaum, RM, Michaelsen, SM, Desrosiers, J, Levin, MF. Development and validation of two new sensory tests of the hand for patients with stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2002;16:630–639.

DeKlerk, AJ, Jouck, LM. Primary tendon healing: An experimental study. South African Medical Journal. 1982;62(9):276.

Ebrecht, M, Hextall, J, Kirtley, LG, Taylor, A, Dyson, M, Weinman, J. Perceived stress and cortisol levels predict speed of wound healing in healthy male adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:798–809.

Ellem, D. Assessment of the wrist, hand and finger complex. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy. 1995;3(1):9–14.

Enebo, BA. Outcome measures for low back pain: Pain inventories and functional disability questionnaires. Journal of Chiropractic Technique. 1998;10:68–74.

Evans, RB, McAuliffe, JA. Wound classification and management. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:311–330.

Fedorczyk, JM, Michlovitz, SL. Pain control: Putting modalities in perspective. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

Fess, EE. Documentation: Essential elements of an upper extremity assessment battery. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

Fess, EE, Gettle, KS, Philips, CA, Janson, JR. Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby, 2005.

Finch, E, Brooks, D, Stratford, PW, Mayo, N. Physical Rehabilitation Outcome Measures: A Guide to Enhanced Clinical Decision Making, Second Edition. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

Fisher, AG. Assessment of Motor and Process Skills Manual. Fort Collins, CO: Three Star Press, 1995.

Flaherty, SA. Pain measurement tools for clinical practice and research. AANA Journal. 1996;64:133–140.

Gatchel, R, Mayer, T, Capra, P, Barnett, J. Million behavioral health inventory: Predicting physical function in patients with low back pain. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1986;67:879–882.

Good, M, Stiller, C, Zauszniewski, JA, Anderson, GC, Stanton-Hicks, M, Grass, JA. Sensation and distress of pain scales: Reliability, validity, and sensitivity. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2001;9:219–238.

Jebsen, RH, Taylor, N, Trieschmann, RB, Trotter, MJ, Howard, LA. An objective and standardized test of hand function. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1969;50(6):311–319.

Kahl, C, Cleland, JA. Visual analogue scale, numeric pain rating scale and the McGill Pain Questionnaire: An overview of psychometric properties. Physical Therapy Reviews. 2005;10:123–128.

Law, M, Baptiste, S, Carswell, A, McColl, M, Polatajko, H, Pollock, N. Canadian Occupational Performance Measures, Third Edition. Ottowa, Ontario: CAOT, 1998.

Law, M, Baptiste, S, McColl, M, Opzoomer, A, Polatajko, H, Pollock, N. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: An outcome measure for occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1990;57(2):82–87.

Lindsay, WK. Cellular biology of flexor tendon healing. In: Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Mackin EJ, eds. Tendon Surgery in the Hand. St. Louis: Mosby, 1987.

Massy-Westropp, N, Krishnan, J, Ahern, M. Comparing the AUSCAN osteoarthritis hand index, Michigan hand outcomes questionnaire, and sequential occupational dexterity assessment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2004;31:1996–2001.

Melzack, R. The McGill pain questionnaire: Major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–299.

Moberg, E. Objective methods for determining the functional value of sensibility in the hand. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1958;40:454–476.

Mosely, LH, Finseth, F. Cigarette smoking: Impairment of digital blood flow and wound healing in the hand. Hand. 1977;9:97–101.

Mueller, BA, Adams, ED, Isaac, CA. Work activities. In: Van Deusen J, Brunt D, eds. Assessment in Occupational Therapy and Physical Therapy. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1997.

Neviaser, RJ. Closed tendon sheath irrigation for pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1978;3:462–466.

O’Rourke, D. The measurement of pain in infants, children, and adolescents: From policy to practice. Physical Therapy. 2004;84:560–570.

Ramadan, AM. Hand analysis. In: Van Deusen J, Brunt D, eds. Assessment in Occupational Therapy and Physical Therapy. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1997.

Ross, RG, LaStayo, PC. Clinical assessment of pain. In: Van Deusen J, Brunt D, eds. Assessment in Occupational Therapy and Physical Therapy. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1997.

Sanford J, Law M, Swanson L, Guyant G (1994) Assessing clinically important change on an outcome of rehabilitation in older adults. Paper presented at the Conference of the American Society of Aging. San Francisco.

Siana, JE, Rex, S, Gottrup, F. The effect of cigarette smoking on wound healing. Scandinavian Journal of Plastic Reconstructive Surgery & Hand Surgery. 1989;23:207–209.

Singer, DI, Moore, JH, Byron, PM. Management of skin grafts and flaps. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

Smith, GN, Bruner, AT. The neurologic examination of the upper extremity. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: State of the Art Reviews. 1998;12(2):225–241.

Smith, KL. Wound care for the hand patient. In Hunter JM, Schneider LH, Macklin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Third Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1990.

Smith, KL. Wound care for the hand patient. In Hunter JM, Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, eds.: Rehabilitation of the Hand: Surgery and Therapy, Fourth Edition, St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

Smith, KL. Wound healing. In: Stanley BG, Tribuzi SM, eds. Concepts in Hand Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1992.

Staley, MJ, Richard, RL, Falkel, JE. Burns. In O’Sullivan SB, Schmidtz TJ, eds.: Physical Rehabilitation: Assessment and Treatment, Third Edition, Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1988.

Suk, M, Hanson, B, Norvell, D, Helfelt, D. Musculo-skeletal Outcome Measures and Instruments. Switzerland: AO Publishing, 2005.

Tarrier, N, Gregg, L, Edwards, J, Dunn, K. The influence of pre-existing psychiatric illness on recovery in burn injury patients: The impact of psychosis and depression. Burns. 2005;31:45–49.

Tomancik, L. Directions for Using Semmes-Weinstein Monofilaments. San Jose, CA: North Coast Medical, 1987.

Van Lankveld, W, van’t Pad Bosch, P, Bakker, J, Terwindt, S, Franssen, M, van Riel, P. Sequential occupational dexterity assessment (SODA): A new test to measure hand disability. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1996;9(1):27–32.

Wadsworth, CT. Wrist and hand examination and interpretation. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 1983;5(3):108–120.

Walsh, M, Muntzer, E. Wound management. In: Stanley BG, Tribuzzi SM, eds. Concepts in Hand Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1992.

Ware, JE, SF-36 Health Survey update. Maruish, ME, eds. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment, Third Edition, volume 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004;693–718.

Ware, JE, Snow, KK, Kosinski, M, Gandek, B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric, Inc, 2000.

Weiss, S, Falkenstein, N. Hand Rehabilitation: A Quick Reference Guide and Review, Second Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, 2005.

Wilson, JA, Clark, JJ. Obesity: Impediment to postsurgical wound healing. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2004;17:426–435.