Geriatric and Hospice Care

Supporting the Aged and Dying Patient

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

1 Describe the life stages of dogs and cats.

2 List and describe the effects of aging on body systems.

3 Discuss the importance of oral health in geriatric dogs and cats.

4 List and describe common cardiac, respiratory, orthopedic, and kidney disorders of geriatric dogs and cats.

5 List and describe common neoplastic and neurologic disorders of geriatric dogs and cats.

6 List and describe common endocrine disorders of geriatric dogs and cats.

7 Discuss components of hospice nursing care of geriatric dogs and cats.

8 Discuss components of the physical examination of a geriatric horse.

9 List and describe common disorders of geriatric horses.

10 List and describe common chronic conditions that affect geriatric horses.

GERIATRIC CATS AND DOGS

A lifetime incorporates the sum of the various life stages of dogs and cats. Age by itself is not a disease. The following life stages apply to most dogs and cats:

• The pediatric life stage is the life stage between birth and 6 months old for both dogs and cats.

• The young adult life stage is the life stage from 6 months to 2 years through 5 years old for dogs. The age ranges of a young adult vary according to the specific dog breed because the large- and giant-dog breeds spend less time as a young adult. Young adult life stage is the life stage from 6 months to 4 years old for cats.

• Mature adult life stage is the life stage from 2 years through 5 years to 9 years through 12 years old for dogs. The age ranges of a mature adult vary according to the specific dog breed because the large- and giant-dog breeds spend less time as a mature adult. Mature adult life stage is the life stage from 4 years to 12 years old for cats.

• Senior life stage is the life stage after mature adulthood. The latter times in the senior dog’s lifetime may be defined as the geriatric years, but dogs, just like humans, like to be referred to as senior citizens. The oldest dog on record was 29 years old. The oldest cat on record was 34 years old.

INTEGRATING GERIATRIC CARE

The care for aging dogs and cats is a proactive comprehensive health care program that addresses the older animal’s special needs. This specialized medical service is based on two premises: first, there are fundamental differences in specific diseases, behavior traits, and nutritional needs of the older animal; second, prevention, early detection, and timely intervention of medical problems can have a significant impact on the life span and quality of life of an older dog or cat.

Care for such older dogs and cats should focus on owner education, disease prevention strategies, and detection of medical and behavioral problems at the earliest possible stage when the prognosis is better and numerous treatment options still exist. The term “senior” or “geriatric” describes that life stage of progressive decline in physical condition, organ function, sensory function, mental function, and immunity. Although it is generally accepted that the senior life stage begins around 7 years of age for the average dog or cat, several interrelated factors, including size and individual genetics, will affect the onset and rate of the progressive decline (Box 37-1).

Although care for the older animal begins at the first new puppy or kitten examination when the animal’s entire life-stage health care program is outlined for the owner, the program is actually implemented when the animal reaches 7 years of age. Starting at 7 years, senior care promotes routine examinations of healthy animals on a twice-a-year basis and advocates routine diagnostic screening for developing diseases. The healthy animal is just one component of the group that should be targeted for senior care. Another component is the older dog or cat that is asymptomatic or is exhibiting early signs of a problem, but the owner either does not recognize the signs or just attributes the signs to “old age” and fails to seek veterinary care.

COMMON PROBLEMS

Conditions that occur commonly in our aging pet population include oral health abnormalities, vision loss, hearing loss, cardiac disease (arrhythmias, murmurs), respiratory disease, neoplasia, kidney disease, urinary and fecal incontinence, dermatologic disease, orthopedic disease, and metabolic conditions. It is important for owners to be aware of these issues and to seek veterinary attention if any of them arise. It is equally important for members of the veterinary community to question owners closely regarding their pet’s health status so that early detection of disease is possible.

Frequently, ill geriatric animals have vague symptoms including inappetence, lethargy, and weight loss. Therefore it is important to acquire a thorough history from owners and to perform a complete physical examination with routine screening tests. Older dogs and cats (those above 7 years of age) should have a complete blood count, chemistry screen, urinalysis, chest radiograph, and blood pressure measurement performed annually. Blood and urine tests screen for dysfunction in the major organ systems, including kidneys and liver. Chest radiographs can be used to evaluate heart size and lung parenchyma.

ORAL HEALTH

Good oral health is essential to ensuring that veterinary patients will continue to eat and drink well. Owner complaints of halitosis, difficulty chewing, dropping food from the mouth, or excessive salivation should prompt a thorough oral examination. Signs of periodontal inflammation, tartar and calculus accumulation, and/or fractured teeth may require surgical intervention. Although geriatric patients may be more of an anesthetic risk, these patients also are more likely to require routine dental prophylactic procedures to ensure oral comfort. Owners should be made aware of at-home prophylaxis that they can perform, such as daily teeth brushing, to limit progression of dental disease. In addition, owners should be instructed to periodically check their pet’s gums and tongue for any abnormal growth or lesion and to contact their veterinarian if there are signs of oral discomfort.

CARDIAC DISEASE

The heart is an organ commonly affected by age. Chronic valvular disease (CVD), resulting from thickening of the heart valves, affects many older dogs, especially smaller breeds. This can lead to heart murmurs, arrhythmias, and even congestive heart failure. Larger-breed dogs, although also affected by CVD, may develop different cardiac disease, such as dilated cardiomyopathy. Any cardiac disease can lead to arrhythmias and congestive heart failure. It is important that a thorough auscultation is performed in every geriatric patient and testing pursued if a murmur or arrhythmia is heard. Additionally, any reports of fatigue, exercise intolerance, collapse, or cough should be investigated further because these may all be secondary to cardiac disturbances.

RESPIRATORY DISEASE

Similar to disease of the heart, respiratory disease is commonly reported in older patients and may be due to chronic lower airway diseases, such as bronchitis, or upper airway diseases, such as a collapsing trachea. Any abnormal lung sounds or owner complaint of coughing, exercise intolerance, or change in breathing rate or effort should be immediately evaluated so as to prevent episodes of distress in the patient.

NEOPLASIA

As in our human counterparts, neoplasia is one of the most common concerns in our geriatric veterinary patients. Cancer may affect a single organ or multiple organs, depending on the type and stage of disease. Early detection is crucial to provide appropriate therapeutic measures to increase life span and improve quality of life.

KIDNEY DISEASE

Chronic renal disease is one of the most common diseases seen in geriatric patients, especially cats. In addition to causing increases in urine output and water intake, kidney disease may affect appetite and overall demeanor as it progresses. With early detection, diet changes and specific medications may be added to slow progression.

URINARY AND FECAL INCONTINENCE

As veterinary patients age, degenerative neurologic diseases and spinal cord problems may lead to difficulties with urination and defecation. This will be discussed in more depth later. Urinary incontinence may be caused by any disease that leads to distention of the urinary bladder.

NEUROLOGIC ABNORMALITIES

In addition to spinal cord abnormalities leading to incontinence, paresis, or paralysis, diseases of the brain occur with increasing frequency in the geriatric patient. Development of inflammatory or neoplastic lesions in the brain itself may lead to altered mentation or behavior changes. Any onset of behavior or mentation change should prompt a veterinary evaluation in an effort to find a medical cause. Veterinary patients, like humans, can display signs of senility with age, and there are medications available that may help if this develops.

ORTHOPEDIC DISEASE

As our pet population ages, one of the most commonly seen problems is arthritis. Degenerative joint disease (DJD) occurs in most breeds of both cats and dogs. Animals that are overweight tend to be more severely affected because excess weight leads to increased stress to joints. The development of antiinflammatory medications and other medications to control pain and discomfort has dramatically improved the quality of life of many geriatric veterinary patients. Additionally, with the introduction of physical therapy and rehabilitation centers in veterinary medicine, strides have been made in the treatment of orthopedic problems.

ENDOCRINE CONDITIONS

The following are some common endocrine disorders seen in geriatric veterinary patients.

Hyperthyroidism

A common disease in geriatric cats, the clinical syndrome of hyperthyroidism is caused by excess production of thyroid hormone. This leads to an increase in metabolic rate, which may cause increased appetite with concurrent weight loss, excessive thirst and urination, lack of grooming, cool-seeking behavior, and vomiting. Life-threatening cardiac complications can also occur. Early detection of hyperthyroidism is important because there are several excellent therapeutic options. Therapy, such as administration of radioactive iodine, can be curative, and if done early enough, some of the cardiac changes induced by the disease may be reversible.

Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus, caused by either insufficient production of insulin or an inability of insulin to work at its receptors, affects middle-aged to older dogs and cats. Insulin is required for glucose to enter cells, and glucose is the necessary nutrient for the body’s cells to perform their normal functions. Diabetes mellitus leads to excessive thirst, urination, and appetite along with weight loss. It predisposes animals to infections, especially in the urinary tract, because glucose overloads the kidneys and is spilled into urine. Glucose is an excellent source of nutrients for bacteria, so animals with diabetes mellitus are at risk for urinary tract infections. Diabetic animals typically require daily injections of insulin by their owners to properly manage the disease.

Hyperadrenocorticism

Hyperadrenocorticism, also called Cushing’s disease, is caused by excessive production of glucocorticoids, such as cortisol. This leads to excessive thirst, urination, and appetite. Glucocorticoids inhibit the ability for neutrophils to adequately protect against infection; therefore animals with hyperadrenocorticism are predisposed to infections, usually of the skin and urinary tract. With appropriate treatment, this can be managed, and infections limited.

Endocrine disease in general can be managed once diagnosed. If left untreated, however, it can lead to recurrent problems related to the urinary tract, skin, and other organ systems. Ultimately, these diseases may be life threatening without proper attention. Because they occur with increased frequency in middle-aged to older veterinary patients, owners should be made aware of their clinical signs and visit a veterinarian for evaluation if one of these diseases is suspected. It is important to remember that appropriate management of these diseases will improve not only longevity, but also quality of life because the patient will likely feel better once the diseases are under control.

HOSPICE CARE FOR THE AGED AND DYING CAT AND DOG

We do what we can to prevent illness in our veterinary patients, but at some point many of our companion animals will develop terminal diseases. As we attempt to treat and control progression of these diseases, technicians in particular may play a large role in ensuring that the aged and dying geriatric patients are kept comfortable at home.

PAIN MEDICATIONS

Regardless of the disease, the goal of the veterinarian and veterinary technician is to provide comfort to the sick patient. One of the most difficult challenges is to accurately assess the level of pain experienced by a particular patient. Unlike humans, dogs and cats have subtle ways of expressing their discomfort, and owners may not be aware that their pet is in pain. However, they may report general malaise, inappetence, or decreased activity in their pet, or they may notice an unwillingness to climb stairs or jump on or off the couch. When performing a physical examination, veterinary technicians should be able to recognize signs of discomfort that may include tachycardia, tachypnea, elevated temperature, organomegaly, unwillingness to use a limb or to posture for normal eliminations (especially in pets with severe hip arthritis or lumbar pain), and yelping when a limb is manipulated. In addition, veterinary technicians must be able to determine the level of pain that the animal is experiencing and whether or not pain management drugs are indicated.

The decision to start a geriatric patient on medications to control pain should not be taken lightly. Many geriatric patients have underlying organ insufficiency, and nearly all pain medications used in veterinary medicine have some potential for organ toxicity. Fortunately, as long as close monitoring of the patient is performed while receiving the medications, permanent damage is unlikely. Complete blood work should be performed before using any type of pain medication in a geriatric patient and should be performed serially while the animal is receiving these medications.

The most common drug classes that veterinarians prescribe to geriatric patients are (1) nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), (2) steroids, and (3) opiates. They each have their own potential benefits and risks. NSAIDs are typically administered orally (although some of them may be given parenterally if necessary) and are potent antiinflammatory agents. They are the most commonly used medications for managing the pain of DJD, chronic intervertebral disk disease, and other forms of arthritis. Although side effects are rare, they may include gastrointestinal (GI) ulceration and renal and hepatic toxicity. In the past, these drugs have rarely been used to manage pain in older cats. However, the development of new formulations of NSAIDs has made their regular use a practical option in cats.

Steroids, more specifically glucocorticoids, also have potent antiinflammatory effects. Unfortunately, long-term use of steroids, such as prednisone (and in some cases even short-term use), may lead to significant side effects that can detrimentally affect quality of life in these patients. These side effects may include excessive thirst and urination, an increased susceptibility to urinary tract infections, increased panting, muscle atrophy and hind limb weakness, GI ulceration, and thromboembolic complications. For these reasons, the use of glucocorticoids for pain control is usually a last resort.

Finally, opiates are narcotic drugs that produce some degree of analgesia. These drugs are known in humans to have the potential to become habit forming and to cause sedation and respiratory depression. Several types of opiate receptors exist in the brain, and different opiates have been developed to work in the area of interest in specific patients. Different methods for administering opiate drugs exist, with the transdermal fentanyl patch providing continuous release of fentanyl over a 72- to 96-hour period of time, after which the patch needs to be removed and a new one reapplied. Tramadol, a “mu” agonist, is an opiate that binds only to “mu” receptors, providing both analgesia and a feeling of euphoria to the patient, without respiratory depression or the risk of addiction.

Refer to Chapter 26 for more information regarding specific drugs.

NURSING CARE FOR THE HOSPICE PATIENT

Many animals that are at the point of needing hospice care are those pets that have their normal mental faculties, but have physical disabilities that prevent them from performing typical daily activities. This would be common in animals with severe orthopedic or spinal cord disease, where the patient is mentally appropriate, has a continued good appetite, but cannot ambulate on its own. Teaching pet owners to care for their recumbent pets at home is therefore critical if the animal is to survive and live comfortably. Veterinary technicians play a key role in providing this valuable instruction. Pet owners need to know how to keep their animals clean and comfortable. They need to be able to assess levels of pain and determine when to give medications. In addition, owners should be taught to turn recumbent animals on a regular basis, at least every 4 to 6 hours, to limit formation of decubital ulcers, or bed sores (see later discussion). Additionally, animals that spend more time on one side than the other will develop atelectasis in the lung lobes on the “down” side, which could lead to respiratory compromise. Recumbent patients are predisposed to pneumonia and should be encouraged to ambulate regularly, if at all possible. Animals should always be in sternal recumbency when fed to prevent accidental aspiration if vomiting or regurgitation should occur. Appetite should be monitored closely because a decline in appetite may indicate the pet’s condition is deteriorating.

DECUBITAL ULCERS

As previously mentioned, one of the more common reasons that animals need at-home hospice care is that they have lost their ability to ambulate well and thus spend a significant amount of time in recumbency. This can be devastating for many dogs and can be especially worrisome in large dogs that are more prone to developing sores and ulcers at pressure points along their body. The most common places to develop these pressure point sores, or “decubital ulcers,” are around the elbows, tarsi, and hips. They can develop anywhere on the body that spends a large amount of time adjacent to the ground because they essentially are sores that occur because of excessive rubbing against the floor.

The best way to prevent such ulcers is to encourage the pet to stand and walk on a regular basis, at least every 4 to 6 hours, and to be sure that the animal does not spend excessive time lying on one side of the body. Keeping the pet clean and dry of urine and other moistness is also essential to prevent development of sores. Extra pads and cushioning should be provided, especially to support areas that are more likely to develop problems.

If ulceration does occur, a topical antibiotic ointment and a protective bandage may be applied to prevent further trauma to the area. The difficulty with bandaging the areas is that often the bandage itself is a cause of trauma because the sore then remains in close contact with the bandaging material and healing cannot occur. If the sore occurs over a joint, such as the elbow or tarsus, a doughnut type of bandage can be fashioned so that the sore itself remains exposed, but it cannot rub against surfaces, thus limiting continued trauma.

SUBCUTANEOUS FLUIDS

Whereas the vast majority of dogs and cats receiving at-home care are eating and drinking on their own, there are a number of pets that require additional fluid support to maintain adequate hydration. Many of the common geriatric diseases we see in veterinary medicine lead to excessive amounts of urination, with a secondary need for increased amounts of water intake. Sometimes the amount of fluid intake necessary to compensate for fluid loss is high, and the patient is unable to adequately compensate. This occurs most frequently with diseases such as renal failure.

If there is concern that a patient may not be receiving adequate amounts of fluid, owners may be taught to administer subcutaneous fluids. There are several methods for administering subcutaneous fluid, and the method used often depends on the amount of fluid administered and the size of the animal receiving the fluid.

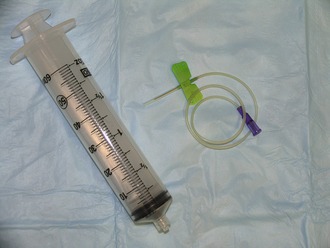

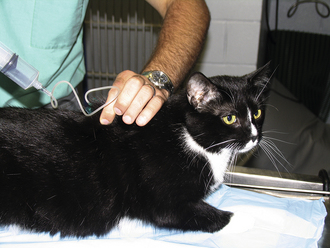

For small dogs and cats, one might choose a butterfly catheter with a needle on the end. The appropriate fluid (usually a maintenance type of fluid) is chosen, and the amount to be given is drawn up into a large syringe. Once drawn up and attached to the end of the butterfly catheter, the needle on the end of the catheter is placed under the skin of the patient (usually in an area where there is some degree of excessive skin tissue, such as between the shoulder blades). The fluid can then be administered by injecting via the syringe. The major drawbacks to this method are: (1) the butterfly needles are often smaller than regular needles, so the fluid is injected more slowly, and (2) if you are administering greater than 60 ml of fluid, you will need to connect more than one syringe because 60-ml syringes are usually the largest used (Figures 37-1 and 37-2).

FIGURE 37-1 A 60-ml syringe is shown on the left and a butterfly catheter is shown on the right. The two components are connected, and fluid is delivered to the patient subcutaneously.

FIGURE 37-2 The skin of the patient is tented, and the needle is inserted through the skin into the subcutaneous space. One hand may be used to restrain the patient and/or hold the needle in place while the other hand injects the fluid. A butterfly catheter will often remain in place once the needle has been inserted through the skin. Many animals tolerate subcutaneous fluid injections well, and it can often be performed by one person.

For a larger volume to be administered, one might elect to attach the entire fluid bag to an extension set with a needle on the end and then administer the fluid directly from the bag. Be sure to prime the extension set with fluids before administering to prevent air from being pushed under the skin. The major drawback to this method is that it is less precise than using a syringe, and the amount of fluid administered is not usually able to be measured exactly (Figures 37-3 and 37-4).

FIGURE 37-3 A bag of replacement fluid is connected to a short- to-medium length extension set, and a needle is connected to the end of the fluid line.

FIGURE 37-4 As explained in Figure 2, the patient’s skin is tented, and the needle is inserted through the skin into the subcutaneous space. The fluid bag is hung at a level above the patient such that fluid flows via gravity. To speed up the flow of fluid, pressure may be applied to the bag.

Owners should be warned that the fluid will often become dependent. In other words, although they are usually given between the shoulder blades, before they are absorbed into the body, they often travel down the side of the animal. This is not of pathologic significance, but is something owners often recognize. Owners should also be aware that excessive amounts of fluid administration, especially in cats, can be detrimental and may lead to fluid overload if the heart is not pumping correctly. Owners of any animal receiving subcutaneous fluid should report any change in respiratory pattern to the veterinarian because this could be indicative of fluid overload or heart failure.

EXPRESSING BLADDERS

Pets with orthopedic diseases, such as hip dysplasia and its associated DJD, often have a difficult time posturing to urinate and/or defecate. Additionally, animals that have had spinal cord injuries or other forms of spinal cord disease may be unable to urinate on their own. Owners can be taught to express their pet’s bladder to allow complete voiding. Bladder expression is a painless procedure if done correctly. There are different methods to perform this procedure, with the main focus on applying gentle pressure to the urinary bladder by squeezing both sides of the bladder. One method would be to have the patient standing. Place one hand on each side of the patient’s abdomen and move the hands caudally toward the pelvis until you can feel a soft, round structure that feels similar to a water balloon. This is the urinary bladder, and once it is found, gentle pressure should be applied to it. The amount of pressure to apply varies with the individual, but with the right amount of pressure, urine will be expressed through the urethra, and a nice stream should be maintained until the “balloon” feels empty.

If the animal will not stand well on his or her own or seems more comfortable in lateral recumbency, bladder expression can be successful using a similar technique as described previously. One hand should be placed on each side of the abdomen and moved caudally toward the pelvis until the bladder is felt and then gentle pressure applied until a nice stream is produced. Excessive pressure should never be applied because it is possible to rupture the urinary bladder.

It is always important to express as much urine as possible from the bladder. When urine sits in the bladder, especially in a patient that is unable to void on its own, infections are likely to occur. Therefore any animal that requires regular bladder expression should be evaluated on a routine basis for urine cultures by the primary veterinarian. Additionally, it is important that owners routinely clean the patient’s fur and skin of urine after expressing the bladder to prevent urine scalding (see later discussion).

URINE SCALDING

Patients that are nonambulatory and recumbent may have urinary incontinence or may consciously urinate in a recumbent position. Urinary incontinence is common in patients that have spinal cord disease. The innervation to the external urethral sphincter arises from spinal cord segments at S1 to S3; therefore spinal cord disease in this area often leads to “lower motor neuron” bladder dysfunction, whereby the sphincter does not close tightly and urine leaks. Additional causes for urinary incontinence may include senility or decreased mobility such that the bladder becomes too full and begins to leak. Any disease that causes excessive urination and thirst will lead the bladder to become distended. Without proper attention, such as regular expression of the bladder or frequent walks to allow for elimination, the animal may dribble urine uncontrollably.

If urine leakage occurs, it may stain and soak the fur and scald the skin. If left untreated, this can eventually lead to sores and skin infections. This is painful and contributes to a poor quality of life. It is important to keep these patients clean and dry at all times. Because bladder expression may lead to urine on the fur and skin, it is important to be aware of this when expressing the bladder and to always clean and dry the patient afterward.

APPETITE STIMULANTS

Decreased appetite and associated weight loss is a serious problem in some geriatric cats and dogs. The first thing to bear in mind when an animal’s appetite begins to wane is that there is usually an underlying cause, such as a systemic illness, orthopedic pain, or central neurologic depression. Every effort should be made to identify and treat an underlying disease. If a focus of orthopedic discomfort is found, for example, antiinflammatory medications or other pain medications may improve appetite.

If no underlying cause is found or if the appetite remains poor even with treatment of the underlying illness, medications, such as antiemetics and appetite stimulants, may be administered.

FEEDING TUBES

The use of feeding tubes for the geriatric patient is a controversial issue because nutritional support in the hospice care setting may be inhumane if the patient is otherwise debilitated. One of the most important indicators of how an animal feels is the presence or absence of an appetite. In a recumbent, debilitated patient, anorexia may mark the time to consider euthanasia of the pet. In this way, placing a feeding tube disrupts an important communication from the animal that his quality of life has deteriorated. It is therefore considered unethical in some cases by some clinicians.

Feeding tubes are necessary sometimes such as in cases where the animal’s alimentary tract is abnormal (megaesophagus), but the patient is otherwise leading a good quality of life. As we discussed earlier, animals often need subcutaneous fluids at home to maintain proper hydration. Feeding tubes may be used for fluid and nutritional support in select animals.

There are many types of feeding tubes available in veterinary medicine. Some are used for short-term management, some for long-term support. The most common short-term feeding tube is a nasoesophageal tube. Whereas animals may be sent home with this type of feeding tube, it is typically for temporary use when we suspect the animal will begin eating on its own relatively soon. This is a flexible, soft, thin-diameter tube that is placed into the nasal cavity and then into the nasopharynx before it ends up in the esophagus. It is held in place by a suture to the side of the pet’s face. Because of its location, animals can easily paw at them and cause early removal; therefore an Elizabethan collar needs to be worn at all times. Because these tubes tend to be thought of as causing mild discomfort to the patient, they again are only temporary. Additionally, the types of food given through the tube are limited and must be of liquid consistency.

A more permanent type of tube is an esophagostomy tube, which is placed while the patient is under general anesthetic through an incision directly into the esophagus from the neck. A slightly larger tube may be used for this type of tube, and thus the choice of liquid or slurry diet is more varied. Additionally, animals tend to tolerate these tubes better because they are not interfering with their face and cause less discomfort.

Finally the most permanent type of tube we can place is one that goes directly into the stomach. A gastrotomy tube may be placed surgically or via endoscopic assistance and typically provides an even larger diameter tube. It is away from the face and the neck and rarely interferes with normal daily activities of the patient. It is ideal for patients with esophageal disorders because the esophagus is avoided entirely. Its drawback is that its placement is much more invasive, and complications, although uncommon, can be devastating and life threatening (i.e., bacterial infection in the abdomen if the tube leaks).

Feeding tubes are reserved for specific occasions and are generally not recommended as a “life support” type of measure. The animal should have a good quality of life other than its inability to adequately obtain nutritional means.

CARTS AND SLINGS

As animals age, orthopedic and neurologic disease can lead to severe impairment in ambulatory abilities. This has historically been difficult to handle because often the animal maintains its mental faculties but simply is unable to get around. Products have been developed that make this type of problem manageable for many owners, while still providing a good quality of life for the pet.

Slings can be used to support the hind end in an animal that has normal use of the front end of its body and still maintains some control of the hind end. Typically, slings fit around the caudal portion of the body, just cranial to the hind limbs, allowing for the caretaker to simply support the hind limbs while the animal ambulates. A sling works best if the animal can still use the hind limbs to some extent, and often the sling is used merely as a support and fail-safe device in the event that the animal cannot bear its entire weight. If the animal is only mildly affected, a soft blanket or towel can be used as a sling. There are products available for purchase (Figure 37-5).

FIGURE 37-5 Bottom’s Up Leash (2003 to 2005 Bottom’s Up Leash, a division of Watson’s Pet Co., Santa Monica, CA 90404) is being used in this patient for support of the hind limbs. Alternatively, depending upon the severity of the hind limb weakness, a towel or soft blanket may be used as a temporary sling. The sling should be used for support only and not as a replacement for walking unless the animal is unable to use their limbs entirely.

For animals that maintain little to no function of their hind limbs, as often occurs with spinal cord injuries, carts have become available for purchase. The hind limbs fit into the apparatus, allowing the animal to use his or her front limbs to move around (Figure 37-6). Some devices exist that may be used for animals that have difficulties with all four limbs (Figure 37-7). Animals typically adapt to these devices quite well.

FIGURE 37-6 This is a cart used for an animal with hind limb paresis. To work properly, the animal must have normal mobility of the front limbs. The patient’s head and front limbs fit through the soft red padding to the left of the picture, and the hind limbs fit through the black doughnut-shaped holes to the right. Normal mobility in the front limbs allows the animal to ambulate fairly well and to control direction changes. These carts can be sized for the particular patient, such that the fitting can actually encourage use of the hind limbs.

FIGURE 37-7 This cart may be used for a patient that has difficulty using all four of their limbs. A benefit of this type of apparatus is that it can be used as an aid to physical therapy because the animal can attempt to use their legs to guide the cart around. It is great for exercise in an otherwise recumbent animal.

WHEN IS THE RIGHT TIME FOR EUTHANASIA?

We are fortunate to be part of veterinary medicine during a time when pets are treated like family members and medical and technologic advances continue to be made. It is important to bear in mind, however, that we have an ethical obligation to prevent suffering in veterinary patients. Owners will often rely on members of the veterinary community to aid in the decision of euthanasia. Although veterinarians, veterinary technicians, and staff members should be careful not to make the decision for owners, they should be prepared to answer questions regarding when the right time might be. Educating owners about determining what signs their animal might show when they are in discomfort is important. Signs such as persistent anorexia, change in breathing rate or effort, pain that is unable to be controlled by medication, or loss of interest in interacting with the owner may all be indicators that the pet’s health is declining. Once the owner recognizes these signs, she should seek advice from her veterinary caregiver. Making the decision to euthanize a pet is difficult for most pet owners, and it is important to support the owner by providing as much clinical information as possible so that the best possible choice can be made for the animal. Refer to Chapter 38 for more information about euthanasia.

GERIATRIC HORSES

As a result of advances in equine management and nutrition in the last few decades, many horses are living beyond 30 years of age. Many of these horses are pasture pets and well loved by their owners, but are not referred to a veterinary hospital when problems arise. Factors such as advanced age, inability to ride in a trailer, and economics play a part in the owner’s decision to not refer the patient. Therefore many equine veterinarians in private practice manage these horses on the farm.

Aged horses are often defined as greater than 20 years old. Many of these horses are greater than 30 years old and often live into their late 30s or even early 40s. These aged horses suffer from a myriad of problems, including poor body condition, lack of teeth, Cushing disease, musculoskeletal disease, such as DJD, or osteoarthritis, and chronic laminitis (inflammation of the laminae in their feet, leading to chronic foot pain and lameness). Cushing disease is a common disease of older horses and will be discussed in detail in this chapter.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

An annual physical examination is crucial to maintain good health of the aged horse. Often problems are found on a thorough examination. Refer to Chapter 8 for a detailed description of physical examination of the equine patient. An annual body condition score is helpful to determine if the aged horse is maintaining an adequate body condition. Acute or chronic weight loss indicates an underlying problem, such as lack of teeth, inability of the GI tract to absorb nutrients, or neoplasia. The horse’s hair coat should be short and smooth. If it is long, wavy, and not shedding out completely in the spring, the horse has Cushing disease, discussed later in the chapter. Common problems in older horses include heaves, laminitis, dental problems, equine recurrent uveitis (ERU), sinusitis, neurologic deficits, and DJD.

COMMON PROBLEMS

The general physical examination of a geriatric horse follows the same guidelines of an examination performed on a younger horse. However, aged horses are more prone to certain problems, so these are highlighted in the following discussion (Box 37-2).

The horse should have a body score performed on physical examination. This system offers an objective way to determine the horse’s condition and assess if weight loss occurs over time. Body condition scoring uses a scale from 1 to 9. One indicates that the horse is emaciated, and 9 is obesity. The horse’s attitude is assessed as bright and alert or depressed (Figure 37-8). Many older horses appear quiet and depressed, but it is often due to Cushing disease and can improve with treatment. The hair coat should be short and shiny. If it is dull, long, wavy, and not shedding completely in the spring (hirsutism), the horse has Cushing disease.

ORAL AND NASAL HEALTH

An oral examination is important to perform since older horses are often in poor condition, unable to chew properly, and drop food when chewing. Many older horses are missing teeth or have sharp points on their teeth preventing normal chewing (hooks) (Figure 37-9). The most severe change is called a wave mouth. This condition occurs when the horse’s teeth are different lengths, preventing normal chewing action. Geriatric horses are also prone to chronic sinus infections, so presence of nasal discharge and a dull sound when percussing the sinuses indicates that the sinus cavity contains fluid.

VISION

An ophthalmic examination evaluates the horse’s eyes for diseases, such as ERU and cataracts. It is not uncommon for an older horse to have significant visual impairment, which is only discovered after an ophthalmic examination. Many older horses are housed on the same farm for years and are able to compensate for loss of vision. If they are moved to a new location, the owner will discover the horse has difficulty maneuvering in the new environment as a result of decreased vision.

CARDIAC DISEASE

Cardiac auscultation is important to assess a resting heart rate and presence of murmurs or arrhythmias. It is helpful to simultaneously evaluate the pulse quality to ensure that it is strong and synchronous with the heartbeat. Mitral regurgitation is the most common valvular lesion in horses greater than 15 years old. One will auscultate a systolic murmur on the left side. Aortic regurgitation also occurs in older horses. One will auscultate a diastolic murmur on the left side. The most common arrhythmia in an older horse is atrial fibrillation. It is often an incidental finding on physical examination. The rhythm is irregularly irregular, and the horse will have a higher resting heart rate than normal. Many horses can tolerate this arrhythmia for years and appear healthy, but may exhibit exercise intolerance at high levels of exercise.

RESPIRATORY DISEASE

A respiratory examination evaluates respiratory rate, respiratory effort, and presence of nasal discharge or coughing. Older horses often have heaves (recurrent airway obstruction) and will have an increased respiratory rate and effort. Chronic cases develop a heave line (hypertrophy of abdominal muscles) resulting from increased effort to exhale.

GASTROINTESTINAL DISEASE

The GI tract is assessed initially by evaluating consistency and amount of manure. The manure should have a normal consistency and not contain large pieces of hay or grain. If these pieces are present, the horse has poor chewing ability to grind food well and needs an oral examination. Presence of diarrhea may indicate chronic colitis or malabsorptive disease.

KIDNEY DISEASE

The horse’s renal system can be assessed by evaluating the amount of water consumed daily and frequency of urination. Annual urinalysis is important to assess concentrating ability of the kidneys and ensure that urine does not contain substances such as protein or glucose.

SKIN DISORDERS

The horse’s integument is examined for dermatitis and abrasions, especially around bony areas, such as the pelvis. Reproductive organs are visually examined. Male horses may have tumors on their sheath (prepuce) or penis. These tumors are often squamous cell carcinoma and require treatment. The rectal area is evaluated for presence of melanomas and normal anal tone.

NEUROLOGIC ABNORMALITIES

On general neurologic examination, older horses may drag their hind feet and have blunted toes. This change may be due to neurologic deficits or musculoskeletal pain (e.g., DJD in the hocks). The horse’s neck should also be examined for evidence of pain. Offer the horse a carrot or handful of grain to encourage the horse to touch his nose to his shoulder. If the horse is reluctant or unable to perform this action, it indicates neck pain. Sometimes this is due to fractures of the cervical vertebrae, diagnosed on cervical radiographs.

ORTHOPEDIC DISEASE

The musculoskeletal examination is an important part of a general physical examination. Older horses are prone to laminitis and may have changes, such as rings on the hoof wall, indicating chronic laminitis (Figure 37-10). They also often have DJD in multiple joints (e.g., carpus, hock) and become stiff without regular pasture turnout (Figure 37-11). Muscle atrophy is also common, especially on the dorsum and around the gluteal area (Figure 37-12).

ENDOCRINE CONDITIONS

Equine Cushing Disease (Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction)

Equine Cushing disease, also known as pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID), is a common disease in horses, especially those greater than 15 years old. Certain breeds, such as quarter horses, also seem more predisposed than other breeds (e.g., thoroughbreds). It is caused by excessive hormonal secretions (pro-opiomelanocortin [POMC]-derived peptides) from the pituitary pars intermedia (PI), stimulating excessive cortisol release from the adrenal glands.

In the brain, the hypothalamus is the master endocrine gland, controlling many activities of other endocrine glands. It resides above the pituitary gland and has neurons with long axons that synapse on melanotrophs in the pituitary PI. Dopamine secreted by these hypothalamic neurons inhibits the production of POMC by the pituitary PI. However, there is a loss of dopamine in Cushing disease, leading to excessive production of POMC by the pituitary gland. POMC is converted into different hormones, including adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which stimulates the adrenal glands to produce excessive cortisol.

Clinical signs of Cushing disease vary with each patient. The affected horse may exhibit one or more clinical signs including hirsutism (overlong hair coat), patchy sweating, lethargy, polyuria, polydipsia (PU/PD), laminitis, “potbelly” appearance, and muscle wasting on the dorsum. Other possible clinical signs include spontaneous lactation in mares without foals, tachypnea (increased respiratory rate), and immunosuppression, resulting in parasitism. Horses with Cushing disease are more prone to concurrent diseases, such as recurrent uveitis, heaves (recurrent airway obstruction), and sinusitis. Abnormalities noted on blood work (complete blood cell count and chemistry profile) include hyperglycemia (blood glucose level greater than 180 mg/dl), increased liver enzymes, neutrophilia, lymphopenia, and anemia.

In the past, many older horses with Cushing disease were misdiagnosed as having hypothyroidism (low thyroid hormone levels). One of the common clinical signs thought to indicate hypothyroidism in horses was presence of a thick, crest neck. It is now recognized that hypothyroidism is not common in horses and the thick neck is due to fat deposits. Measuring baseline thyroid hormone levels (e.g., T4 and T3) is not reliable in horses. These levels can be decreased for many reasons and should not be used as a screening test. Although many horses receive thyroid supplementation, it is not a benign medication in human patients and should be used only when indicated in equine patients.

Diagnosis of Cushing disease is made based on the horse’s history, signalment, physical examination, and ancillary diagnostic blood tests. There are three tests typically used: dexamethasone suppression test (DST) to assess cortisol response; serial measurements of ACTH, insulin, and dextrose; and thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) stimulation. The DST is not always reliable and can give inconsistent results. The test requires steroid administration, and steroids are associated with laminitis in horses. Horses with Cushing disease are more prone to laminitis and/or may have a current episode of laminitis, so steroid administration is often contraindicated. Serial measurements of ACTH, insulin, and dextrose can be more accurate than DST. Steroids are not used in this test, so it is a good option for many horses with Cushing disease. However, one sample may not be diagnostic, so taking three blood samples in one day (am, noon, pm) is optimal. ACTH levels increase in the fall as compared with January or May, so results should be interpreted based on the time of year. The TRH stimulation appears to be a promising diagnostic test. In recent publications, it may be more accurate than DST or serial measurements of ACTH, insulin, and dextrose. TRH administration will increase ACTH concentrations in both clinically normal and abnormal horses. However, ACTH levels are greater in abnormal horses in the amount of increase, maximum ACTH concentration, and persistence of high concentrations. Despite different diagnostic tests available, sometimes owners of geriatric horses refuse diagnostic tests. Empirical treatment should be considered if the owner refuses diagnostic tests and the horse’s history, signalment, and physical examination findings are consistent with Cushing disease.

The primary treatment for Cushing disease is a dopamine agonist, pergolide. Many 450-kg horses respond well to 1 mg pergolide orally once a day, but the dose needs to be altered based on response to treatment. Many clinical signs will improve with treatment, but hirsutism usually remains. Numerous horses with Cushing disease appear quiet and depressed, but once treatment is initiated, become much more alert and act younger. Rechecking blood tests after starting medication will aid in determining the optimum pergolide dose. Another medication, cyproheptadine, was used in the past to treat Cushing disease. It is not as effective as pergolide and more expensive.

General management is important for horses with Cushing disease. The horse should have his teeth floated every 6 months or yearly to maintain oral health. Regular foot care every 4 to 5 weeks will keep him more comfortable and prevent an overlong toe, which can aggravate lameness or laminitis. Regular deworming and manure management, such as weekly removal from the pasture, will aid in parasite control. Horses with Cushing disease have poor thermoregulation and patchy sweating associated with hirsutism. These patients are more comfortable with regular body clipping to minimize hirsutism and using blankets in the winter. Clipping also permits better assessment of the horse’s body condition.

Nutrition is important with aged equine patients and those with Cushing disease. Feeding small amounts of a senior diet often, adding corn oil (¼ cup daily) and grass pasture, and avoiding lush pastures are beneficial. Alfalfa hay or soaked cubes or pellets can help maintain an older horse’s body condition. Alternate sources include processed hay, such as Dengie hay.

CHRONIC DISEASES OF THE GERIATRIC HORSE

Geriatric horses often have multiple problems that require close attention to minimize complications. Cushing disease is common in older horses and can cause immunosuppression. It also leads to or exacerbates other diseases, such as heaves (recurrent airway obstruction), ERU, laminitis, and sinusitis. To successfully manage these other conditions, Cushing disease requires treatment with pergolide to minimize immunosuppression.

HEAVES (RECURRENT AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION)

This disease can be acute or chronic in nature. Some horses are only affected a few weeks each year, some horses are affected year-round. Usually, if a horse acutely develops signs of heaves, it eventually becomes a chronic condition and requires careful management to minimize clinical signs. Horses with heaves are often allergic to dust or mold in the environment. Horses living in a dusty stable with minimal pasture turnout, exposed to cobwebs, straw, and hay are prone to developing heaves. This allergic reaction leads to inflamed airways and constriction of the smooth muscle in the airways. This combination causes narrowed airways and leads to difficult breathing, especially when exhaling. Clinical signs on physical examination include increased respiratory rate (tachypnea) and increased effort (dyspnea), nostril flare, and dry cough. The horse will have no fever and may have a clear nasal discharge. Horses with chronic heaves are often in poor body condition with a heave line (extreme development of the external abdominal oblique muscles as a result of increased effort on exhalation). The horse may extend his head on exhalation to improve airflow. On thoracic auscultation, wheezes will be heard on both sides of the chest, especially on expiration. A rebreathing bag (large trash bag) may be used to encourage the horse to inhale deeply, permitting better thoracic auscultation. After removing the bag, a horse with heaves will cough and take a long time to return to normal breathing. Additional diagnostic tests include blood tests (CBC, chemistry profile), transtracheal wash, bronchioalveolar lavage (BAL), and thoracic radiographs. Abnormalities on blood tests include increased total protein and increased fibrinogen concentration. Samples of airway secretions can be obtained on transtracheal wash or BAL and submitted for cytology and culture to differentiate heaves from infection (e.g., pneumonia). Changing the horse’s environment to minimize allergens is the most important part of therapy. Increasing pasture turnout, soaking hay for 4 hours before feeding and eliminating dusty bedding is vital to minimize clinical signs. Medication to control inflammation and bronchoconstriction is administered systemically (e.g., IV, IM, PO) or locally (e.g., using an inhaler). Steroids (e.g., dexamethasone, fluticasone) are used to decrease inflammation, and bronchodilators (e.g., clenbuterol, albuterol) dilate narrowed airways. Local treatment using an AeroMask provides effective treatment while minimizing possible side effects. However, this method is expensive because inhalers for human patients are used. It also requires a dedicated caregiver initially giving medications a few times daily. Systemic steroids are effective, but have been associated with laminitis in horses. Horses with heaves require management changes, close monitoring, and early treatment at onset of clinical signs, but can live comfortably for a long time if treated properly.

LAMINITIS (FOUNDER)

Laminitis is a devastating, sometimes fatal disease in young and older horses. Although there has been extensive research, the pathophysiology of laminitis is not clear. It may be acute or chronic in nature, and all four feet may be affected or just one or two feet. Ultimately the soft tissue in the foot (laminas) holding the bone (distal phalanx, or P3) and hoof wall together becomes inflamed and necrotic. The horse may initially develop separation of the hoof wall from the bone. In severe cases, the bone will rotate, sink, and penetrate the bottom of the foot (sole), necessitating euthanasia. Laminitis may be a complication from a primary problem (e.g., postcolic surgery) or develop acutely with no apparent cause. However, laminitis most commonly occurs in the geriatric horse from Cushing disease. Some breeds are more prone to developing laminitis (e.g., quarter horse, ponies). Laminitis is a painful condition because the horse is standing on the affected foot and often cannot find relief from pain. Clinical signs of laminitis include reluctance to walk and turn, bounding digital arterial pulses (palpated over the fetlock near the sesamoid bones), rings on the hoof wall, depression, and inappetence resulting from discomfort. Diagnostic tests include radiographs of the feet and additional tests to diagnose the inciting cause. If the inciting cause is identified, treatment is directed at the disease. For example, if Cushing disease is diagnosed, treatment with pergolide is paramount to control laminitis. Treatment for laminitis is often symptomatic and includes shoeing changes (e.g., blunting the toe), footpads, deep bedding in the stall (e.g., sand), and NSAIDs (e.g., phenylbutazone). It is ideal if the horse will lie down to relieve pressure from affected feet. Laminitis may be acute or chronic; geriatric horses often develop chronic laminitis and require regular foot care every 4 weeks to minimize clinical signs. Recovery can be complete, or there may be permanent damage of the laminas, so long-term care is directed at the individual patient.

SINUSITIS

Chronic sinusitis is common in older horses with Cushing disease because of immunosuppression. One or more sinuses may be affected. Clinical signs include purulent, unilateral nasal discharge, and a reddish color may be present. Percussing the sinuses in the middle of the horse’s head will elicit a dull sound, indicating fluid accumulation. Diagnostic tests include an oral examination to look for tooth root abscessation, upper airway endoscopy, skull radiographs, and evaluation for Cushing disease. Treatment includes long-term antimicrobials, flushing the sinuses under general anesthetic, removal of an infected tooth root, and pergolide if Cushing disease is present.

DENTAL PROBLEMS

Geriatric horses often develop dental disease as they age. As their teeth wear down or fall out, the opposing tooth will become too long or develop points (sharp areas on the tooth). This causes abnormal occlusion, and the horse will not be able to chew properly. The most severe abnormality is called wave mouth. The horse will have abnormal occlusion of all teeth and extreme difficulty chewing food. Wave mouth is a common problem in geriatric horses. Clinical signs of oral abnormalities include poor body condition, slow chewing, dropping a lot of grain or hay from the mouth, discomfort when chewing, and whole grain in manure. A thorough dental examination should be performed at least annually on horses 20 years or older to prevent oral abnormalities. When proper dental care is provided, many older horses are able to chew their food well and maintain their body condition.

EQUINE RECURRENT UVEITIS (ERU OR MOON BLINDNESS)

Geriatric horses often develop eye problems, and the leading cause of blindness in horses is equine recurrent uveitis. It is a progressive disease causing frequent episodes of inflammation and degeneration in one or both eyes. Some breeds, such as appaloosas, are more commonly affected. Clinical signs include a swollen and painful eye, photophobia, corneal edema (blue tint to cornea), corneal abrasion or ulceration, miosis (constricted pupillae), neovascularization (blood vessel growth on cornea), anterior uveitis (inflammation in the front chamber of the eye), hypopyon (cellular debris in the eye), and hyphema (hemorrhage in the eye). A horse with a swollen, painful eye is treated as an emergency because the cornea is thin (1.5 mm thick) with no blood supply and the eye can rupture if not treated quickly. Horses also live in a contaminated environment and can develop fungal ulcers that can be resistant to therapy. Diagnostic evaluation includes sedating the horse to perform a thorough ophthalmologic examination, applying fluorescein stain to evaluate the cornea for ulceration, and taking samples for cytology and culture. When a corneal ulcer is present, the damaged corneal epithelium will stain bright green, showing the extent of the ulcer. Both eyes should be evaluated because many geriatric horses will have cataracts and degenerative retinal changes. If the horse lacks vision in the clinically unaffected eye and the other eye is swollen and painful, the horse may be scared and react differently than normal. Treatment depends on if there are primarily inflammatory changes or if a corneal ulcer is present. If no ulcer is present, topical steroids (e.g., dexamethasone, prednisolone) and other medications (atropine, serum, systemic NSAIDs, such as flunixin meglumine) are used to eliminate inflammation and dilate the pupil. If an ulcer is present, topical antimicrobials and other medications (atropine, serum, systemic NSAIDs, such as flunixin meglumine) are used until the ulcer resolves, and then steroids can be used. Mild cases can be treated with topical ointments or solutions. Severe cases require frequent treatment that is difficult in a horse with a painful eye, so a subpalpebral catheter can be placed for ease of treatment. Sometimes surgery is also required to aid healing. Once the episode has resolved, preventative treatment, such as using a fly mask and antiinflammatory medications, are often needed to minimize additional inflammatory flares. Enucleation (removing the affected eye) is the last resort in older horses since both eyes are often affected. Without treatment, the horse will be in pain and the affected eye will become smaller over time.

NEUROLOGIC DEFICITS

Older horses can develop mild or progressive neurologic deficits as a result of trauma or chronic changes, such as cervical fractures compressing the spinal cord. Clinical signs in an affected horse include depression, decreased proprioception, dragging toes, ataxia, and reluctance to turn his neck. Diagnostic tests include a thorough physical and neurologic examination, blood tests including liver function tests, cervical radiographs, and cerebrospinal fluid aspiration. Treatment includes antiinflammatory medications and small paddock turnout and stall confinement, if needed. These horses are often weak and may lose their position in the hierarchy. Therefore it is important to place them with other horses in similar condition and to feed them individually to ensure that they are receiving adequate nutrition.

MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

Geriatric horses often have multiple sites of DJD (osteoarthritis) and can be lame at the walk and trot. The hocks, carpi, cervical vertebrae, and pelvis are most commonly affected. Soft tissue problems include degeneration of the suspensory tendon. Diagnostic tests include lameness examination, local anesthetic for nerve blocks, sonographic evaluation, and radiographs to identify the affected areas. Treatment includes local joint injection of steroids to relieve clinical signs, but cannot be repeated too many times. Many of these horses require long-term NSAIDs (e.g., phenylbutazone) to have a good quality of life. Monitoring the horse using diagnostic tests, such as chemistry profile, packed-cell volume (PCV) and total protein, and urinalysis, is an important part of using these medications. Although there are side effects with chronic NSAID use, such as renal insufficiency or right dorsal colitis, it is also paramount to keep these geriatric horses comfortable at the end of their lives. There is a new NSAID, firocoxib, that is promising because it is a COX-2 inhibitor with minimal side effects, sparing gastric mucosal protection and renal blood flow. Pasture turnout as much as possible is important because older horses become stiff when standing in the stall for too long. Regular foot trimming every 4 weeks and shoes are often vital to maintain the horse’s comfort.

MANAGEMENT, NUTRITION, AND NURSING CARE OF THE GERIATRIC HORSE

Management of the aged horse is paramount to maintaining optimal health and keeping the horse comfortable. Frequent hoof trimming every 4 weeks is important to maintain the horse’s comfort, especially when he has DJD and lameness. If the horse’s foot grows too long, it changes the angle of the leg and makes walking more difficult. Routine dental floating every 6 months will keep the horse comfortable, eating well, and prevent problems, such as a wave mouth.

It is notoriously difficult to maintain weight and body condition in older horses. It is especially difficult to improve a horse’s condition if he has lost weight or is already thin.

There are additional considerations in treating geriatric horses. These horses seem more sensitive to certain medications, such as sedation and NSAIDs. It may be a combination of decreased muscle mass and renal and/or liver insufficiency, but many geriatric horses only tolerate one half of a typical dose of sedative given intravenously. For example, only give 75 mg xylazine and 1 mg butorphanol or 2 mg detomidine and 1 mg butorphanol to an average 450-kg (1000 lb) horse. Some older horses are sensitive to NSAIDs, such as flunixin meglumine or phenylbutazone, and only tolerate one half of a typical dose given intravenously. For example, give 250 mg flunixin meglumine or 1 gram phenylbutazone to an average 450-kg (1000 lb) horse. Many of these horses receive daily NSAID treatment for chronic DJD (osteoarthritis). They may receive 1 g of phenylbutazone orally daily for a few years and without medication are in significant pain. When administering NSAID medication, the owner should be aware of potential side effects, such as renal failure or right dorsal colitis. It is important to monitor the horse’s attitude, appetite, manure production, renal values (creatinine, blood urea nitrogen [BUN]), urinalysis, and PCV and total protein. If there are any changes in these values, the patient and treatment protocol should be reassessed.

General management recommendations include regular deworming, either daily or every 8 weeks using dewormers on a rotational schedule. Frequent manure removal and low stocking density (e.g., a few horses in a large pasture) are important to minimize parasite burden in a pasture. Regular fecal examinations are helpful to assess if the deworming schedule is adequate. It is not uncommon to have a false-negative test result from fecal examination, but the horse has a parasite burden, so regular deworming is important even if the fecal examination test result is negative.

Regular vaccination is recommended, using the recommended vaccine protocol for the area. If a horse has a history of vaccine reactions, pretreatment with an NSAID, such as phenylbutazone or flunixin meglumine, is recommended. Many horses develop more severe reactions over time, so geriatric horses with a history of vaccine reaction are at higher risk. If the horse still has a reaction despite pretreatment, only the necessary vaccines should be administered to minimize complications. Annual physical examinations are important to maintain the health of a geriatric horse and to detect any problems. Many geriatric horses seem to develop renal and liver insufficiency over time, so annual blood tests (e.g., CBC, chemistry profile) are important to monitor their health.

Management is paramount to maintaining a healthy geriatric horse. Geriatric horses can have a good quality of life with proper care, but require close monitoring. Many are turned out in pasture and not monitored well. They may be in poor condition under a thick hair coat, so it is best to train the owner to assess the horse’s body condition. Clipping older horses and placing a blanket in the winter keep these older horses comfortable. Geriatric horses with an overlong hair coat are not able to thermoregulate well, may have patchy sweating, and be prone to develop dermatitis. It is also advisable to clip over the jugular vein before administering intravenous medications to easily visualize the vein and avoid the carotid artery. Frequent pasture turnout is ideal to maintain body condition, GI tract health, and minimize stiffness. It is also important to turn the geriatric horse out with other horses in equal condition. Otherwise, the older horse will be at the bottom of the hierarchy and may not have adequate access to food. If the older horse is in poor body condition, feeding him individually is important to ensure that the horse is receiving enough food and assess appetite. Feeding free-choice high-quality hay with supplementation of alfalfa (either hay or soaked alfalfa cubes or pellets) will aid in maintaining weight. Feeding an Equine Senior feed is also good to maintain weight or provide calories when the horse has lost teeth. Adding corn oil (¼ to ½ cup per day) to the feed provides additional calories.

END OF LIFE ISSUES

When a geriatric horse is no longer living a good quality of life, euthanasia may be considered by the owner and/or recommended by the veterinarian. Considerations for euthanasia include poor body condition or rapidly losing weight, refractory pain (e.g., acute, severe laminitis), and severe DJD, leading to chronic, severe lameness. Additional considerations include episodes of the horse falling frequently and impending cold weather. Cold weather, snow, and icy conditions are difficult times for older horses to maintain body condition. If the horse slips on the ice, it may be impossible to lift the horse up again, necessitating euthanasia. These geriatric horses have often been a part of the family for years, and the entire family would like to be present for the horse’s final moments. A scheduled euthanasia can allow the family to say goodbye and offer a peaceful end to a beloved horse.

Geriatric horses have many good years ahead of them if properly cared for and closely monitored. They often make excellent companions to younger horses and provide much enjoyment for their owners. When problems arise, they need to be detected quickly and treatment initiated to offer optimal quality of life for the geriatric equine patient. The veterinary technician plays an integral role in caring for these patients by educating clients, providing thorough nursing care, and recognizing and addressing the needs of these special patients.

CONCLUSION

There are numerous ways that we, as members of the veterinary community, can contribute to the health and well-being of our veterinary patients. As pets continue to be considered family members by more and more people, there will be a continued need for home and barn support for these patients. Technicians can play a large role in providing hospice care for these patients. It is important to remember that hospice care should be provided only while the animal maintains a good quality of life. Once quality of life declines, euthanasia should be considered.

Couetil, L., Paradis, M.R., Knoll, J. Plasma adrenocorticotropin concentration in healthy horses and in horses with clinical signs of hyperadrenocorticism. J Vet Intern Med. 1996;10:1–6.

Donaldson, M.T. Equine Cushing’s disease: diagnosis, treatment, pathogenesis and clinical signs. Proc North Am Vet Conference. 2004.

Donaldson, M.T., LaMonte, B.H., Morresey, P., et al. Treatment with pergolide or cyproheptadine of pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (equine Cushing’s disease). J Vet Intern Med. 2002;16:742–746.

Dybdal, N.O. Endocrine disorders. In Bradford, Smith, eds.: Large animal internal medicine, ed 3, St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Dybdal, N.O., Hargreaves, K.M., Madigan, J.E., et al. Diagnostic testing for pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction in horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1994;204:627–632.

Perkins, G., Lamb, S., Erb, H., et al. Plasma adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) concentrations and clinical response in horses treated for equine Cushing disease with cyproheptadine or pergolide. Equine Vet J. 2002;34:679–685.

TECHNICIAN NOTE

TECHNICIAN NOTE