CHAPTER 10 Evaluation of the Child with Special Needs

CHAPTER 10 Evaluation of the Child with Special Needs

Children with disabilities (cerebral palsy), severe chronic illnesses (diabetes or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]), congenital defects (cleft lip and palate), and health-related educational and behavioral problems (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or a learning disability) are children with special health care needs. Many of these children share a broad group of experiences and encounter similar problems, such as school difficulties and family stress. The term children with special health care needs defines these children noncategorically, without regard to specific diagnoses, in terms of increased service needs. Approximately 18% of children in the United States younger than 18 years of age have a physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition requiring services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally. If the definition of chronic illness is restricted to a condition that lasts or is expected to last more than 3 months and limits age-appropriate social functioning, such as school performance or recreational activities, about 6% of children are affected in the United States.

The goal in managing a child with special health care needs is to maximize the child’s potential for productive adult functioning by treating the primary diagnosis and by helping the patient and family deal with the stresses and secondary impairments incurred because of the disease or disability. Whenever a chronic disease is diagnosed, family members typically grieve, show anger, denial, negotiation (in an attempt to forestall the inevitable), and depression. Because the child with special health care needs is a constant reminder of the object of this grief, it may take family members a long time to accept the condition. A supportive physician can facilitate the process of acceptance by education and by allaying guilty feelings and fear. To minimize denial, it is helpful to confirm the family’s observations about the child. The family may not be able to absorb any additional information initially, so written material and the option for further discussion at a later date should be offered. Parents often recount that they did not remember anything after the pediatrician shared the devastating news.

The primary pediatrician should provide a medical home to maintain close oversight of treatments and subspecialty services, provide preventive care, and facilitate interactions with school and community agencies. The family is the one constant in a child’s life, whereas service systems and support personnel within those systems fluctuate. A major goal of family-centered care is for the family and child to feel in control. Although the medical management team usually directs treatment in the acute health care setting, the locus of control should shift to the family as the child moves into a more routine, home-based life. Treatment plans should be organized to allow the greatest degree of normalization of the child’s life. As the child matures, self-management programs that provide health education, self-efficacy skills, and techniques such as symptom monitoring help promote good long-term health habits. These programs should be introduced at 6 or 7 years of age, or when a child is at a developmental level to take on chores and benefit from being given responsibility. Self-management minimizes learned helplessness and the vulnerable child syndrome, both of which occur commonly in families with chronically ill or disabled children.

MULTIFACETED TEAM ASSESSMENT OF COMPLEX PROBLEMS

When developmental screening and surveillance suggest the presence of significant developmental lags, the pediatrician should take responsibility for coordinating the further assessment of the child by the team of professionals and provide continuity in the care of the child and family. The physician should become aware of the facilities and programs for assessment and treatment in the local area. If the child is at high risk because of prematurity or another identified illness that might have long-term developmental effects, a structured follow-up program to monitor the child’s progress may already exist. Under federal law, children are entitled to developmental assessments regardless of income if there is a suspected developmental delay or a risk factor for delay (e.g., prematurity, failure to thrive, and parental mental retardation). Up to 3 years of age, special programs are developed by states to implement this policy. Developmental interventions are arranged in conjunction with third-party payers (insurance companies, Medicaid, state children’s health insurance program) with the local program funding the cost only when there is no insurance coverage. After 3 years of age, development programs usually are administered by school districts. Federal laws also mandate that special education programs be provided for all children with developmental disabilities from birth through 21 years of age.

Children with special needs may be enrolled in pre-K programs with a therapeutic core, including visits to the program by therapists to work on challenges in the context of the pre-K schedule. Children who are of traditional school age (kindergarten through secondary school) should be evaluated by the school district and provided an individualized educational plan (IEP) to address any deficiencies. An IEP may feature individual tutoring time (resource time), placement in a special education program, placement in classes with children with severe behavioral problems, or other strategies to address deficiencies. As part of the comprehensive evaluation of developmental/behavioral issues, all children should receive a thorough medical assessment. A variety of other specialists may assist in the assessment and intervention, including subspecialist pediatricians (e.g., neurology, orthopedics, psychiatry, developmental/behavioral), therapists (e.g., occupational, physical, oral-motor), and others (e.g., psychologists, early childhood development specialists).

Medical Assessment

The physician’s main goals in team assessment are to identify the cause of the developmental dysfunction, if possible (often a specific cause is not found), and identify and interpret other medical conditions that have a developmental impact. The comprehensive history (Table 10-1) and physical examination (Table 10-2) include a careful graphing of growth parameters and an accurate description of dysmorphic features. Many of the diagnoses are rare or unusual diseases or syndromes. Many of these diseases and syndromes are discussed further in Sections 9 and 24.

TABLE 10-1 Information to Be Sought During the History Taking of a Child with Suspected Developmental Disabilities

| Item | Possible Significance |

|---|---|

| Parental Concerns | Parents are quite accurate in identifying development problems in their children |

| Current Levels of Developmental Functioning | Should be used to monitor child’s progress |

| Temperament | May interact with disability or may be confused with developmental delay |

| PRENATAL HISTORY | |

| Alcohol ingestion | Fetal alcohol syndrome; an index of caretaking risk |

| Exposure to medication, illegal drug, or toxin | Development toxin (e.g., phenytoin); may be an index of caretaking risk |

| Radiation exposure | Damage to CNS |

| Nutrition | Inadequate fetal nutrition |

| Prenatal care | Index of social situation |

| Injuries, hyperthermia | Damage to CNS |

| Smoking | Possible CNS damage |

| HIV exposure | Congenital HIV infection |

| Maternal PKU | Maternal PKU effect |

| Maternal illness | Toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpesvirus infections |

| PERINATAL HISTORY | |

| Gestational age, birth weight | Biologic risk from prematurity and small for gestational age |

| Labor and delivery | Hypoxia or index of abnormal prenatal development |

| Apgar scores | Hypoxia, cardiovascular impairment |

| Specific perinatal adverse events | Increased risk of CNS damage |

| NEONATAL HISTORY | |

| Illness—seizures, respiratory distress, hyperbilirubinemia, metabolic disorder | Increased risk of CNS damage |

| Malformations | May represent syndrome associated with developmental delay |

| FAMILY HISTORY | |

| Consanguinity | Autosomal recessive condition more likely |

| Mental functioning | Increased hereditary and environmental risks |

| Illnesses (e.g., metabolic disease) | Hereditary illness associated with developmental delay |

| Family member died young or unexpectedly | May suggest inborn error of metabolism or storage disease |

| Family member requires special education | Hereditary causes of developmental delay |

| SOCIAL HISTORY | |

| Resources available (e.g., financial, social support) | Necessary to maximize child’s potential |

| Educational level of parents | Family may need help to provide stimulation |

| Mental health problems | May exacerbate child’s conditions |

| High-risk behaviors (e.g., illicit drugs, sex) | Increased risk for HIV infection; index of caretaking risk |

| Other stressors (e.g., marital discord) | May exacerbate child’s conditions or compromise care |

| OTHER HISTORY | |

| Gender of child | Important for X-linked conditions |

| Developmental milestones | Index of developmental delay; regression may indicate progressive condition |

| Head injury | Even moderate trauma may be associated with developmental delay or learning disabilities |

| Serious infections (e.g., meningitis) | May be associated with developmental delay |

| Toxic exposure (e.g., lead) | May be associated with developmental delay |

| Physical growth | May indicate malnutrition; obesity, short stature associated with some conditions |

| Recurrent otitis media | Associated with hearing loss and abnormal speech development |

| Visual and auditory functioning | Sensitive index of impairments in vision and hearing |

| Nutrition | Malnutrition during infancy may lead to delayed development |

| Chronic conditions such as renal disease | May be associated with delayed development or anemia |

CNS, central nervous system; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PKU, phenylketonuria.

From Liptak G: Mental retardation and developmental disability. In Kliegman RM, editor: Practical Strategies in Pediatric Diagnosis and Therapy, Philadelphia, 1996, WB Saunders.

TABLE 10-2 Information to Be Sought During the Physical Examination of a Child with Suspected Developmental Disabilities

| Item | Possible Significance |

|---|---|

| General Appearance | May indicate significant delay in development or obvious syndrome |

| STATURE | |

| Short stature | Williams syndrome, malnutrition, Turner syndrome; many children with severe retardation have short stature |

| Obesity | Prader-Willi syndrome |

| Large stature | Sotos syndrome |

| HEAD | |

| Macrocephaly | Alexander syndrome, Sotos syndrome, gangliosidosis, hydrocephalus, mucopolysaccharidosis, subdural effusion |

| Microcephaly | Virtually any condition that can retard brain growth (e.g., malnutrition, Angelman syndrome, de Lange syndrome, fetal alcohol effects) |

| FACE | |

| Coarse, triangular, round, or flat face; hypotelorism or hypertelorism, slanted or short palpebral fissure; unusual nose, maxilla, and mandible | Specific measurements may provide clues to inherited, metabolic, or other diseases such as fetal alcohol syndrome, cri du chat syndrome (5p− syndrome), or Williams syndrome |

| EYES | |

| Prominent | Crouzon syndrome, Seckel syndrome, fragile X syndrome |

| Cataract | Galactosemia, Lowe syndrome, prenatal rubella, hypothyroidism |

| Cherry-red spot in macula | Gangliosidosis (GM1), metachromatic leukodystrophy, mucolipidosis, Tay-Sachs disease, Niemann-Pick disease, Farber lipogranulomatosis, sialidosis III |

| Chorioretinitis | Congenital infection with cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, or rubella |

| Corneal cloudiness | Mucopolysaccharidosis I and II, Lowe syndrome, congenital syphilis |

| EARS | |

| Pinnae, low set or malformed | Trisomies such as 18, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, Down syndrome, CHARGE association, cerebro-oculofacial-skeletal syndrome, fetal phenytoin effects |

| Hearing | Loss of acuity in mucopolysaccharidosis; hyperacusis in many encephalopathies |

| HEART | |

| Structural anomaly or hypertrophy | CHARGE association, CATCH-22, velocardiofacial syndrome, glycogenosis II, fetal alcohol effects, mucopolysaccharidosis I; chromosomal anomalies such as Down syndrome; maternal phenylketonuria; chronic cyanosis may impair cognitive development |

| LIVER | |

| Hepatomegaly | Fructose intolerance, galactosemia, glycogenosis types I to IV, mucopolysaccharidosis I and II, Niemann-Pick disease, Tay-Sachs disease, Zellweger syndrome, Gaucher disease, ceroid lipofuscinosis, gangliosidosis |

| GENITALIA | |

| Macro-orchidism | Fragile X syndrome |

| Hypogenitalism | Prader-Willi syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, CHARGE association |

| EXTREMITIES | |

| Hands, feet, dermatoglyphics, and creases | May indicate specific entity such as Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome or be associated with chromosomal anomaly |

| Joint contractures | Sign of muscle imbalance around joints (e.g., with meningomyelocele, cerebral palsy, arthrogryposis, muscular dystrophy; also occurs with cartilaginous problems such as mucopolysaccharidosis) |

| SKIN | |

| Café au lait spots | Neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, Bloom syndrome |

| Eczema | Phenylketonuria, histiocytosis |

| Hemangiomas and telangiectasia | Sturge-Weber syndrome, Bloom syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia |

| Hypopigmented macules, streaks, adenoma sebaceum | Tuberous sclerosis, hypomelanosis of Ito |

| HAIR | |

| Hirsutism | de Lange syndrome, mucopolysaccharidosis, fetal phenytoin effects, cerebro-oculofacial-skeletal syndrome, trisomy 18 |

| NEUROLOGIC | |

| Asymmetry of strength and tone | Focal lesion, cerebral palsy |

| Hypotonia | Prader-Willi syndrome, Down syndrome, Angelman syndrome, gangliosidosis, early cerebral palsy |

| Hypertonia | Neurodegenerative conditions involving white matter, cerebral palsy, trisomy 18 |

| Ataxia | Ataxia-telangiectasia, metachromatic leukodystrophy, Angelman syndrome |

CATCH-22, cardiac defects, abnormal face, thymic hypoplasia, cleft palate, hypocalcemia, defects on chromosome 22; CHARGE, coloboma, heart defects, atresia choanae, retarded growth, genital anomalies, ear anomalies (deafness).

From Liptak G: Mental retardation and developmental disability. In Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS, editors: Practical Strategies in Pediatric Diagnosis and Therapy, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, WB Saunders, p 540.

Motor Assessment

The comprehensive neurologic examination is an excellent basis for evaluating motor function, but it should be supplemented by an adaptive functional evaluation (see Chapter 179). Watching the child at play aids assessment of function. Specialists in early childhood development and therapists (especially occupational and physical therapists who have experience with children) can provide excellent input into the evaluation of age-appropriate adaptive function.

Psychological Assessment

Psychological assessment includes the testing of cognitive ability (Table 10-3) and the evaluation of personality and emotional well-being. The IQ and mental age scores, taken in isolation, are only partially descriptive of a person’s functional abilities, which are a combination of cognitive, adaptive, and social skills. Tests of achievement are subject to variability based on culture, educational exposures, and experience and must be standardized for social factors. Projective and nonprojective tests are useful in understanding the child’s emotional status. Although a child should not be labeled as having a problem solely on the basis of a standardized test, such tests do provide important and reasonably objective data for evaluating a child’s growth within a particular educational program.

| Test | Age Range | Special Features |

|---|---|---|

| INFANT SCALES | ||

| Bayley Scales of Infant Development (2nd ed) | 2–42 mo | Mental, psychomotor scales, behavior record; weak intelligence predictor |

| Cattell Infant Intelligence Scale | Birth–30 mo | Used to extend Stanford-Binet downward |

| Gesell Developmental Schedules | Birth–3 yr | Used by many pediatricians |

| Ordinal Scales of Infant Psychological Development | Birth–24 mo | Six subscales; based on Piaget’s stages; weak in predicting later intelligence |

| PRESCHOOL SCALES | ||

| Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (4th ed) | 2 yr–adult | Four area scores, with subtests and composite IQ score |

| McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities | 2½–8 yr | 6–18 subtests; good at defining learning disabilities; strengths/weaknesses approach |

| Wechsler Primary and Preschool Test of Intelligence–Revised (WPPSI-R) | 3–6½ yr | 11 subtests; verbal, performance IQs; long administration time; good at defining learning disabilities |

| Merrill-Palmer Scale of Mental Tests | 2–4½ yr | General test for young children |

| Differential Abilities Scale | 2½ yr–adult | Special nonverbal composite; short administration time |

| SCHOOL-AGE SCALES | ||

| Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (4th ed) | 2 yr–adult | See above |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4th ed) (WISC IV) | 6–16 yr | See comments on WPPSI-R |

| Leiter International Performance Scale | 2 yr–adult | No verbal abilities needed |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised (WAIS-R) | 16 yr–adult | See comments on WPPSI-R |

| Differential Abilities Scale | 2½ yr–adult | See above |

| ADAPTIVE BEHAVIOR SCALES | ||

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale | Birth–adult | Interview/questionnaire; typical persons and blind, deaf, developmentally delayed and retarded |

| American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR) Adaptive Behavioral Scale | 3 yr–adult | Useful in mental retardation, other disabilities |

Educational Assessment

Educational assessment involves the evaluation of areas of specific strengths and weaknesses in reading, spelling, written expression, and mathematical skills. Schools routinely screen children with group tests to aid in problem identification and program evaluation. For the child with special needs, this screening ultimately should lead to individualized testing and the development of an IEP that would enable the child to progress comfortably in school. Diagnostic teaching, in which the child’s response to various teaching techniques is assessed, also may be helpful.

Social Environment Assessment

Assessment of the environment in which the child is living, working, playing, and growing is important in understanding the child’s development. A home visit by a social worker, community health nurse, or home-based intervention specialist can provide valuable information about the child’s social milieu. If there is a suspicion of inadequate parenting and, especially, if there is a suspicion of neglect or abuse (including emotional abuse), the child and family must be referred to the local child protection agency. Information about reporting hotlines and local child protection agencies usually is found inside the front cover of local telephone directories (see Chapter 22).

MANAGEMENT OF DEVELOPMENTAL PROBLEMS

Intervention in the Primary Care Setting

The clinician must decide whether a problem requires referral for further diagnostic workup and management or whether management in the primary care setting is appropriate. Counseling roles required in caring for these children are listed in Table 10-4. When a child is young, much of the counseling interaction takes place between the parents and the clinician, and as the child matures, direct counseling shifts increasingly toward the child.

The assessment process may be therapeutic in itself. By assuming the role of a nonjudgmental, supportive listener, the clinician creates a climate of trust in which the family feels free to express difficult or painful thoughts and feelings. Expressing emotions may allow the parent or caregiver to move on to the work of understanding and resolving the problem.

Interview techniques also may facilitate clarification of the problem for the family and for the clinician. The family’s ideas about the causes of the problem and descriptions of attempts to deal with it can provide a basis for developing strategies for problem management that are much more likely to be implemented successfully because they emanate in part from the family. The clinician shows respect by endorsing the parent’s ideas when appropriate; this can increase self-esteem and sense of competency.

Educating parents about normal and aberrant development and behavior may prevent problems through early detection and anticipatory guidance. Such education also communicates the physician’s interest in hearing parental concerns. Early detection allows intervention before the problem becomes entrenched, and associated problems develop.

The severity of developmental and behavioral problems ranges from variations of normal, to problematic responses to stressful situations, to frank disorders. The clinician must try to establish the severity and scope of the patient’s symptoms so that appropriate intervention can be planned.

Counseling Principles

Behavioral change is difficult in any situation. For the child, behavioral change must be learned, not simply imposed. It is easiest to learn when the lesson is simple, clear, and consistent and presented in an atmosphere free of fear or intimidation. Parents often try to impose behavioral change in an emotionally charged atmosphere, most often at the time of a behavioral violation. Clinicians often try to teach parents with hastily presented advice when the parents are distracted by other concerns or not engaged in the suggested behavioral change.

Apart from management strategies directed specifically at the problem behavior, regular times for positive parent-child interaction should be instituted. Frequent, brief, affectionate physical contact over the day provides opportunities for positive reinforcement of desirable child behaviors and for building a sense of competence in the child and the parent.

Most parents feel guilty when their children have a developmental/behavioral problem. This guilt may be caused by the assumption or fear that the problem was caused by inadequate parenting or guilt about previous angry responses to the child’s behavior. If possible and appropriate, the clinician should find ways to alleviate guilt, which may be a serious impediment to problem solving.

Interdisciplinary Team Intervention

In many cases, a team of professionals is required to provide the breadth and quality of services needed to appropriately serve the child who has developmental problems. The primary care physician should monitor the progress of the child and continually reassess that the requisite therapy is being accomplished.

Educational intervention for a young child begins as home-based infant stimulation, often with an early childhood educator; nurse; or occupational, speech, or physical therapist providing direct stimulation for the child and training the family to provide the stimulation. As the child matures, a center-based nursery program may be indicated. For the school-age child, special services may range from extra attention given by the classroom teacher to a self-contained special education classroom.

Psychological intervention may be parent or family directed or may become, with an older child, primarily child directed. Examples of therapeutic approaches are guidance therapies, such as directive advice giving, counseling the family and child in their own solutions to problems, psychotherapy, behavioral management techniques, psychopharmacologic methods, and cognitive therapy.

Motor intervention may be performed by a physical or occupational therapist. Neurodevelopmental therapy (NDT), the most commonly used method, is based on the concept that nervous system development is hierarchical and subject to some plasticity. The focus of NDT is on gait training and motor development, including daily living skills; perceptual abilities, such as eye-hand coordination; and spatial relationships. Sensory integration therapy is also used by occupational therapists to structure sensory experience from the tactile, proprioceptive, and vestibular systems to allow for adaptive motor responses.

Speech-language intervention by a speech therapist (oral-motor therapist) is usually part of the overall educational program and is based on the tested language strengths and weaknesses of the child. Children needing this type of intervention may show difficulties in reading and other academic areas and develop social and behavioral problems because of their difficulties in being understood and in understanding others. Hearing intervention, performed by an audiologist (or an otolaryngologist), includes monitoring hearing acuity and providing amplification when necessary via hearing aids.

Social and environmental intervention generally takes the form of nursing or social work involvement with the family. Frequently the task of coordinating the services of other disciplines falls to these specialists. These case managers may be in the private sector, from the child’s insurance or Medicaid plan or part of a child protection agency.

Medical intervention for a child with a developmental disability involves providing primary care as well as specific treatment of conditions associated with disability. Although curative treatment often is not possible because of the irreversible nature of many disabling conditions, functional impairment can be minimized through thoughtful medical management. Certain general medical problems are found more frequently in delayed and developmentally disabled people (Table 10-5). Many of these children have associated medical conditions, especially if the delay is part of a known syndrome (Down syndrome or vertebral defects, imperforate anus, trachoesophageal fistula, and radial and renal dysplasia [VATER association]). Some children may have a limited life expectancy. Supporting the family through palliative care, hospice, and bereavement is another important role of the primary care pediatrician.

TABLE 10-5 Recurring Medical Issues in Children with Developmental Disabilities

| Problem | Ask About or Check |

|---|---|

| Motor | Range of motion examination; scoliosis check; assessment of mobility; interaction with orthopedist, physiatrist, and physical therapist/occupational therapist as needed |

| Diet | Dietary history, feeding observation, growth parameter measurement and charting, supplementation as indicated by observations |

| Sensory impairments | Functional vision and hearing screening; interaction as needed with ophthalmologist, audiologist |

| Dermatology | Examination of all skin areas for decubitus ulcers or infection |

| Dentistry | Examination of teeth and gums; confirmation of access to dental care |

| Behavioral problems | Aggression, self-injury, pica; sleep problems; psychotropic drug levels and side effects |

| Advocacy | Educational program, family supports, financial supports |

| Seizures | Major motor, absence, other suspicious symptoms; monitoring of anticonvulsant levels and side effects |

| Infectious diseases | Ear infections, diarrhea, respiratory symptoms, aspiration pneumonia, immunizations (especially hepatitis B and influenza) |

| Gastrointestinal problems | Constipation, gastroesophageal reflux, gastrointestinal bleeding (stool for occult blood) |

| Sexuality | Sexuality education, hygiene, contraception (when appropriate), genetic counseling |

| Other syndrome-specific problems | Ongoing evaluation of other “physical” problems as indicated by known mental retardation/developmental disability etiology |

SELECTED CLINICAL PROBLEMS: THE SPECIAL NEEDS CHILD

Mental Retardation

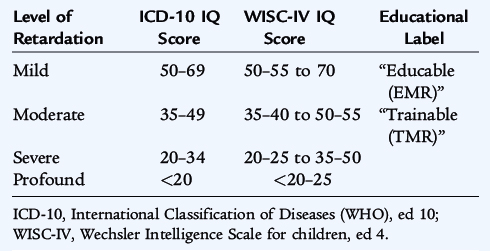

Mental retardation (MR) is defined as significantly subnormal intellectual functioning for a child’s developmental stage, existing concurrently with deficits in adaptive behaviors (self-care, home living, communication, and social interactions). MR is defined statistically as cognitive performance that is two standard deviations below the mean (roughly below the third percentile) of the general population as measured on standardized intelligence testing. There have been no longitudinal studies of the prevalence of MR in the United States, and cross-sectional estimates have varied immensely. The last known estimates were about 20,000 per million, or 2%. Levels of MR from IQ scores derived from two typical tests are shown in Table 10-6. Caution must be exercised in interpretation because these categories do not reflect actual functional level of the tested individual.

The etiology of the central nervous system insult resulting in MR may involve genetic disorders, teratogenic influences, perinatal insults, acquired childhood disease, and environmental and social factors (Table 10-7). Mild MR correlates with socioeconomic status, although profound MR does not. Although a single organic cause may be found, each individual’s performance should be considered a function of the interaction of environmental influences with the individual’s organic substrate. It is common for a child with MR to have behavioral difficulties resulting from the MR itself and from the family’s reaction to the child and the condition. More severe forms of MR can be traced to biologic factors. The earlier the cognitive slowing is recognized, the more severe the deviation from normal is likely to be.

TABLE 10-7 Differential Diagnosis of Mental Retardation*

EARLY ALTERATIONS OF EMBRYONIC DEVELOPMENT

UNKNOWN CAUSES

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL PROBLEMS

PREGNANCY PROBLEMS AND PERINATAL MORBIDITY

HEREDITARY DISORDERS

ACQUIRED CHILDHOOD ILLNESS

TORCH, toxoplasmosis, other (congenital syphilis and viruses), rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus.

* Some health problems fit in several categories (e.g., lead intoxication may be involved in several areas).

† This also may be considered as an acquired childhood disease.

The first step in the diagnosis and management of a child with MR is to identify functional strengths and weaknesses for purposes of medical and habilitative therapies. When the developmental delays have been identified, the history and physical examination may suggest a diagnostic approach that, then, may be confirmed by laboratory testing and/or imaging. Frequently used laboratory tests include chromosomal analysis and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. Almost one third of individuals with MR do not have readily identifiable reasons for their disability.

Vision Impairment

Significant visual impairment is a problem in many children. Partial vision (defined as visual acuity between 20/70 and 20/200) occurs in 1 in 500 school-age children in the United States, with about 35,000 children having visual acuity between 20/200 and total blindness. Legal blindness is defined as distant visual acuity of 20/200 or worse. Although this definition allows for considerable residual vision, such impairment can be a major barrier to optimal educational development.

The most common cause of severe visual impairment in children is retinopathy of prematurity (see Chapter 61). Congenital cataracts may lead to significant amblyopia. Cataracts also are associated with other ocular abnormalities and developmental disabilities. Amblyopia is defined as a pathologic alteration of the visual system characterized by a reduction in visual acuity in one or both eyes with no clinically apparent organic abnormality that can completely account for the visual loss. Amblyopia is due to a distortion of the normal clearly formed retinal image (from congenital cataracts or severe refractive errors); abnormal binocular interaction between the eyes with one eye competitively inhibiting the other (strabismus); or a combination of both mechanisms. Albinism, hydrocephalus, congenital cytomegalovirus infection, and birth asphyxia are other significant contributors to blindness in children.

Children with mild to moderate visual impairment usually are discovered to have an uncorrected refractive error. The most common presentation is myopia or nearsightedness. Other causes are hyperopia (farsightedness) and astigmatism (alteration in the shape of the cornea leading to visual distortion). In children younger than 6 years of age, high refractive errors in one or both eyes also may cause amblyopia, which aggravates the vision impairment.

The diagnosis of severe visual impairment commonly is made when an infant is 4 to 8 months of age. Clinical suspicion is based on parental concerns aroused by unusual behavior, such as lack of smiling in response to appropriate stimuli, the presence of nystagmus, other wandering eye movements, or motor delays in beginning to reach for objects. Fixation and visual tracking behavior can be seen in most infants by 6 weeks of age. This behavior can be assessed by moving a brightly colored object (or the examiner’s face) across the visual field of a quiet but alert infant at a distance of 1 foot. The eyes also should be examined for red reflexes and pupillary reactions to light, although optical alignment (binocular vision with both eyes consistently focusing on the same spot) should not be expected until the infant is beyond the newborn period. Persistent nystagmus is abnormal at any age. If ocular abnormalities are identified, referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist is indicated.

During the newborn period, vision may be assessed by physical examination and by visual evoked response (VER). This test evaluates the conduction of electrical impulses from the optic nerve to the occipital cortex of the brain. The eye is stimulated by a bright flash of light or with an alternating checkerboard of black-and-white squares and the resulting electrical response is recorded from electrodes strategically placed on the scalp, similar to an electroencephalogram.

There are many developmental implications of visual impairment. Perception of body image is abnormal, and imitative behavior, such as smiling, is delayed. Delays in mobility may occur in children who are visually impaired from birth, although their postural milestones (ability to sit) usually are achieved appropriately. Social bonding with the parents also is affected.

Visually impaired children can be helped in various ways. Classroom settings may be augmented with resource-room assistance to present material in a nonvisual format; some schools consult with an experienced teacher of the blind. Fine motor activity development, listening skills, and Braille reading and writing are intrinsic to successful educational intervention with the child who has severe visual impairment.

Hearing Impairment

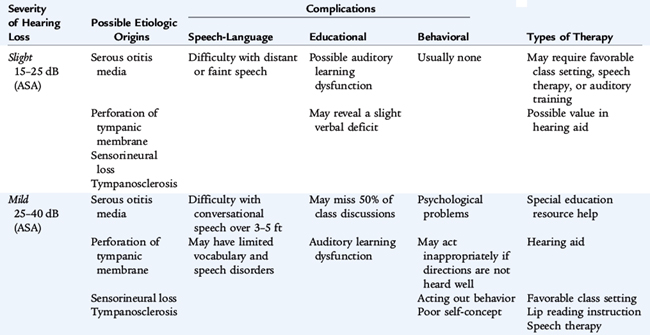

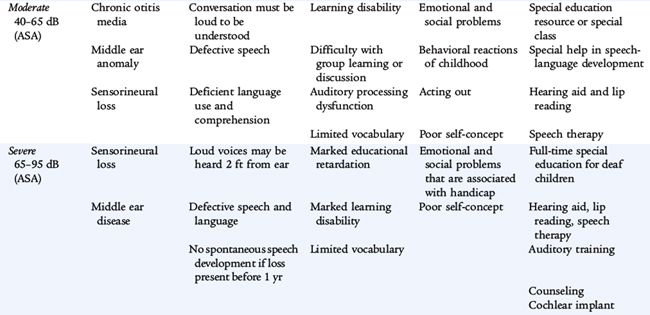

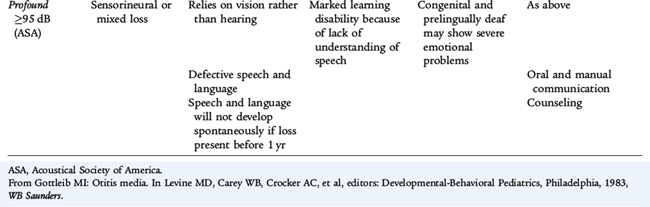

The clinical significance of hearing loss varies with its type (conductive vs. sensorineural), its frequency, and its severity as measured in number of decibels heard or the number of decibels of hearing lost. The most common cause of mild to moderate hearing loss in children is a conduction abnormality caused by acquired middle ear disease. This abnormality may have a significant effect on the development of speech and other aspects of language development, particularly if there is chronic fluctuating middle ear fluid. When hearing impairment is more severe, sensorineural hearing loss is more common. Causes of sensorineural deafness include congenital infections (e.g., rubella or cytomegalovirus), meningitis, birth asphyxia, kernicterus, ototoxic drugs (especially aminoglycoside antibiotics), and tumors and their treatments. Genetic deafness may be either dominant or recessive in inheritance; this is the main cause of hearing impairment in schools for the deaf. In Down syndrome, there is a predisposition to conductive loss caused by middle ear infection and sensorineural loss caused by cochlear disease. Any hearing loss may have a significant effect on the child’s developing communication skills. These skills then affect all areas of the child’s cognitive and skills development (Table 10-8).

It is sometimes quite difficult to determine accurately the presence of hearing in infants and young children. Using developmental surveillance to inquire about a newborn’s or infant’s response to parental sounds or even observing the response to sounds in the office is unreliable for identifying hearing-impaired children. Universal screening of newborns is required prior to nursery discharge and includes:

Both of these tests are quick (5 to 10 minutes), painless, and may be performed while the infant is sleeping or lying still. The tests are sensitive but not as specific as more definitive tests. Infants who fail these tests are referred for more comprehensive testing. Many of these infants have normal hearing on definitive testing. Infants who do not having normal hearing are immediately referred for etiologic diagnosis and early intervention.

For children not screened at birth or children with suspected acquired hearing loss, later testing may allow early appropriate intervention. Hearing can be screened by means of an office audiogram, but other techniques are needed (ABR, behavior audiology) for young, neurologically immature or impaired, and behaviorally difficult children. The typical audiologic assessment includes pure-tone audiometry over a variety of sound frequencies (pitches), especially over the range of frequencies in which most speech occurs. Tympanometry is used in the assessment of middle ear function and the evaluation of tympanic membrane compliance for pathology in the middle ear, such as fluid, ossicular dysfunction, and eustachian tube dysfunction (see Chapter 9).

The treatment of conductive hearing loss (largely due to otitis media and middle ear effusions) is discussed in Chapter 105. Treatment of sensorineural hearing impairment may be medical or surgical. The audiologist may believe that amplification is indicated, in which case hearing aids can be tuned preferentially to amplify the frequency ranges in which the patient has decreased acuity. Educational intervention typically includes speech-language therapy and teaching American Sign Language. Even with amplification, many hearing-impaired children show deficits in processing information presented through the auditory pathway, requiring special educational services for helping to read and for other academic skills. Cochlear implants may benefit some children. A cochlear implant is a surgically implantable device that provides hearing sensation to individuals with severe to profound hearing loss who do not benefit from hearing aids. The implants are designed to substitute for the function of the middle ear, cochlear mechanical motion, and sensory cells, transforming sound energy into electrical energy that initiates impulses in the auditory nerve. Cochlear implants are indicated for children between 12 months and 17 years of age with profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss who have limited benefit from hearing aids. In addition, they have failed to progress in auditory skill development and have no radiologic or medical contraindications. Implanting children as young as possible gives them the most advantageous auditory environment for speech-language learning.

Speech-Language Impairment

Parents often bring the concern of speech delay to the physician’s attention when they compare their young child with others of the same age (Table 10-9). The most common causes of the speech delay are MR, hearing impairment, social deprivation, autism, and oral-motor abnormalities. If a problem is suspected based on screening with tests such as the Denver II or other standard screening test (Early Language Milestone Scale), a referral to a specialized hearing and speech center is indicated. While awaiting the results of testing or initiation of speech-language therapy, parents should be advised to speak slowly and clearly to the child (and avoid baby talk). Parents and older siblings should read to the speech-delayed child frequently.

TABLE 10-9 Clues to When a Child with a Communication Disorder Needs Help

0–11 MONTHS

12–23 MONTHS

24–36 MONTHS

ALL AGES

Adapted from Weiss CE, Lillywhite HE: Communication Disorders: A Handbook for Prevention and Early Detection, St Louis, 1976, Mosby.

Speech disorders include articulation, fluency, and resonance disorders. Articulation disorders include difficulties producing sounds in syllables or saying words incorrectly to the point that other people cannot understand what is being said. Fluency disorders include problems such as stuttering, the condition in which the flow of speech is interrupted by abnormal stoppages, repetitions (st-st-stuttering), or prolonging sounds and syllables (ssssstuttering). Resonance or voice disorders include problems with the pitch, volume, or quality of a child’s voice that distract listeners from what is being said.

Language disorders can be either receptive or expressive. Receptive disorders refer to difficulties understanding or processing language. Expressive disorders include difficulty putting words together, limited vocabulary, or inability to use language in a socially appropriate way.

Speech-language pathologists (speech or oral-motor therapists) assess the speech, language, cognitive-communication, and swallowing skills of children; determine what types of communication problems exist; and the best way to treat these challenges. Speech-language pathologists skilled at working with infants and young children are also vital in training parents and infants in other oral-motor skills, such as teaching the parent of an infant born with cleft lip and palate how to feed the infant appropriately.

Speech-language therapy involves having a speech-language specialist work with a child on a one-on-one basis, in a small group, or directly in a classroom to overcome a specific disorder using a variety of therapeutic strategies. Language intervention activities involve having a speech-language specialist interact with a child by playing and talking to him or her. The therapist may use pictures, books, objects, or ongoing events to stimulate language development. The therapist also may model correct pronunciation and use repetition exercises to build speech and language skills. Articulation therapy involves having the therapist model correct sounds and syllables for a child, often during play activities.

Children enrolled in therapy early in their development (<3 years of age) tend to have better outcomes than children who begin therapy later. Older children can make progress in therapy, but progress may occur more slowly because these children often have learned patterns that need to be modified or changed. Parental involvement is crucial to the success of a child’s progress in speech-language therapy.

Cerebral Palsy

Cerebral palsy (CP) refers to a group of nonprogressive, but often changing, motor impairment syndromes secondary to anomalies or lesions of the brain usually arising before or after birth. A total of 2 to 2.5 of every 1000 live-born children in developed countries have CP; incidence is higher in premature and twin births. Prematurity and low birth weight infants (leading to perinatal asphyxia), congenital malformations, and kernicterus are causes of CP noted at birth. Ten percent of children with CP have acquired CP that occurs at later ages. Meningitis and head injury (accidental and nonaccidental) are the most common causes of acquired CP (Table 10-10). Nearly 50% of children with CP have no identifiable risk factors.

TABLE 10-10 Risk Factors for Cerebral Palsy

PREGNANCY AND BIRTH

ACQUIRED AFTER THE NEWBORN PERIOD

Most children with CP, except in its mildest forms, are diagnosed in the first 18 months of life when they fail to attain motor milestones or when they show abnormalities such as asymmetric gross motor function, hypertonia, or hypotonia. CP can be characterized further by the affected parts of the body (Table 10-11) and descriptions of the predominant type of motor disorder (Table 10-12). Comorbidities in these children often include epilepsy, learning difficulties, behavioral challenges, and sensory impairments. Many of these children have an isolated motor defect. Some affected children may be intellectually gifted.

TABLE 10-11 Descriptions of Cerebral Palsy by Site of Involvement

TABLE 10-12 Classification of Cerebral Palsy by Type of Motor Disorder

Treatment depends on the pattern of dysfunction. Physical and occupational therapy can facilitate optimal positioning and movement patterns, increasing function of the affected parts. Spasticity management also may include oral medications, botulinum toxin injections, and implantation of intrathecal baclofen pumps. Management of seizures, spasticity, orthopedic impairments, and sensory impairments all may help improve educational attainment. CP cannot be cured, but a host of interventions can improve functional abilities, participation in society, and quality of life.

Brosco J., Mattingly M., Sanders L. Impact of specific medical interventions on reducing the prevalence of mental retardation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:302-309.

Council on Children With Disabilities. Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics. Bright Futures Steering Committee. Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):405-420.

Daniels S., Greer F. Committee on Nutrition: Lipid screening and cardiovascular health in childhood. Pediatrics. 2008;122:198-208.

Gardner H.G. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Office-based counseling for unintentional injury prevention. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):202-206.

Hagan J., Shaw J., Duncan P. Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents, 3rd ed, Elk Grove Village Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008.

Kliegman R., Behrman R., Jenson H., et al. Nelson textbook of pediatrics, 18th ed, Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2007.