Chapter 4 Socio-behavioural aspects of treatment with medicines

Introduction

In attempting to understand the treatment process with medicines we can partially apply the same theoretical models as for illness behaviour presented in the previous chapter (see also Fig. 3.1). It is also feasible to regard the treatment process from a macro and a micro perspective. The macro perspective includes an analysis of the different systems and structural components in place to ensure a rational use of medicines, which is one of the primary goals of the system. The micro perspective includes the patient level and the interaction between patient and practitioner.

When explaining patient behaviour in taking or not taking medicines and the interaction with the environment we can, for example, use the social learning theory and the concept of self-efficacy (see p. 33). The health belief model (see p. 31) has been used to explain patients’ adherence in taking medicines. In addition, we need to understand the behaviour of the physician when prescribing the medicines and dealing with the patient. Likewise our interest is to understand the behaviour of the pharmacist and the patient–physician–pharmacist interactions. Different models and theories provide a slightly different perspective on the use of medicines, and the adequacy of the theory often depends on the question being addressed. Because this is a relatively new research area there are still many gaps in our understanding of the different processes involved and their interactions.

Functions of medicines

Social and behavioural scientists have proposed that medicines and use of medicines also serve important latent functions for the individual and society. In this context it is important to have a wide definition of the word ‘medicines’. The functions may be the same as the approved medical uses or may be hidden functions. Barber and later Svarstad have identified a long list of these functions:

A societal perspective on rational use of medicines

Defining rational use

Rational use of medicines has been defined as the safe, effective, appropriate and economic use of medicines. The definition as such seems to be clear and straightforward, but how do we define ‘safe’ and the other components of the definition? Safety relates to aspects like relative and absolute safety. It is well known that all medicines have side-effects, some less and some more. The safety aspect has to be assessed from many different angles, e.g. the severity of the disease, the available treatment options including medicines and non-medicines options, long-term or short-term treatment, whether the medicine is to cure or control symptoms, any risks of overdoses and other possible factors.

Effectiveness relates to the question of how well the medicine works in daily practice when used by unselected populations and patients having co-morbidities and other medications. Efficacy relates to a clinical trial type of situation, where we want to know the maximum effect of the medicine in a particular disease and when it is optimally used in selected patients with as few confounding factors as possible, such as co-morbidities and other medicines used simultaneously.

Appropriateness refers to how a medicine is being prescribed and used in and by patients, including aspects such as appropriate indication, with no contraindications, appropriate dosage and administration. Duration of treatment should be optimal and the medicine should be correctly dispensed with appropriate and sufficient information and counselling. To achieve the intended effects, the medicine also needs to be correctly used by the patient.

The economic aspect does not refer merely to price; rather, a cost-effectiveness approach needs to be applied, where all factors are assessed. A somewhat more expensive medicine may be preferable to a less expensive medicine, for example because it has better treatment outcomes or fewer side-effects. We should also be aware of hidden costs, such as a need for more extensive laboratory tests, which may increase the total cost of a particular treatment (see Ch. 19).

National medicines policy

Ensuring rational use of medicines requires that there are appropriate structures in place and that the processes involved are functioning well. The starting point and frame of reference is the national medicines policy (NMP). The role of an NMP is usually discussed in the context of medicine-related issues in developing countries. In industrialized countries it has received much less attention, because many key issues and policies regarding medicines and their rational use are already in place. However, the global crisis in healthcare financing, especially the medicines budget, has created a momentum to look more closely at medicine policies in industrialized countries too. When trying to understand the general principles that can be applied to all countries it is helpful to use the guidelines that have been proposed for developing countries, and from there try to understand how the system works and what might be the strong and weak points in each particular country.

The NMP can be seen as a guide for action, including the goals and priorities set by the government, the main strategies and approaches. It also serves as a framework in the coordination of different activities. Depending on cultural, historical and socio-economic factors there are differences in objectives, strategies and approaches between countries, but some common components can be distinguished. The goals for an NMP can be divided into:

There is further discussion of these issues in Chapter 7.

Ensuring safety of medicines

Why is it important to regulate and control the medicine sector with special laws and regulations? The medicine sector is of concern to the whole population. Most citizens will use medicines and related services on a regular basis and therefore the functioning of the sector is of common interest. There are also many parties involved – patients, healthcare providers, manufacturers and sales people – requiring detailed rules for interaction and functioning. The consequences from the lack of medicines or their misuse might be serious. History has shown that informal controls are not sufficient or respected. Generally there is little disagreement about the need to regulate the medicine sector; the disagreement lies rather in the extent to which it should be regulated.

Legislation and regulation include different health-related laws, pharmacy law, trademark and patent laws, criminal law, international treaties (e.g. on narcotic and psychotropic drugs) and governmental decrees. Sometimes there may be a lack of political will or a weak infrastructure to enforce the laws. When looking at the legal situation in the medicine sector in different countries, the problems seem to be more often in the enforcement of legislation than in the lack of legislation.

Registration of medicines is a key tool in assuring the safety, quality and efficacy of a new medicine being introduced on the market. In this connection the new medicine will also be scheduled to a certain category such as prescription or over the counter (OTC) medicine. The infrastructure that will assure quality, safety and efficacy can be ascertained by licensing and inspection of manufacturers, distributors and the premises, but also by setting some standards on the professionals working there. There is wide international cooperation in this field among the different competent authorities. Nevertheless every now and then the media have reports about counterfeit products and toxic products sold to the public, sometimes with disastrous consequences. News such as somebody having replaced glycerin with diethyleneglycol in paracetamol syrups intended for small children should not be possible with all the controls in place today.

Pharmaco-epidemiological studies are used to assure the safety of new medicines after they have been accepted on the market. This kind of information can supplement that available from pre-marketing studies; it can also give a better quantification of the incidence of known adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and also of the beneficial effects. For ethical and other reasons it is not always suitable to perform clinical trials on certain patient groups such as children, elderly people and pregnant women in the early phase of a new product. It is also important to establish how other medicines and diseases may alter the positive effects. New types of information not available from pre-marketing studies, such as rare undetected ADRs, long-term effects that manifest only after long use or after long latency periods, and effects with low frequency are also the concern of pharmaco-epidemiological studies. Further aspects on the safety and evaluation of medicines are dealt with in Chapters 19 and 47.

Ensuring the availability of medicines

Availability of medicines is one of the key requirements in a well functioning pharmaceutical system. This includes a functioning manufacturing and importation system of medicines, good procurement and distribution practices. These functions are often taken for granted in industrialized countries, while in developing countries they are key issues for a functioning system. In developing countries the maintenance of a constant supply of medicines, keeping them in good condition and minimizing losses due to spoilage and expiry are issues that need to be solved to assure the availability of medicines to the population.

With more and more sophisticated new medicines, the prices of new products are beyond reach for a large part of the population if no mechanisms like price control or reimbursement/insurance systems are in place. Economic availability of medicines will be a major policy issue in all countries during the next few years. With national medicine budgets increasing annually by more than 10%, there is a doubling of the budget every 5–6 years.

Use of medicines

Medicine (drug) use or utilization studies and pharmaco-epidemiological studies during the last 25 years have basically tried to describe who are using the medicines and how much are being used. On a macro level, factors influencing medicine consumption include among others: size of population, age and gender distributions, occupational structure, income levels (gross national product), availability of health services, number and type of health facilities, number and type of personnel, social insurance and reimbursement mechanisms.

Medicine use studies have also been used to identify different types of ‘irrational use’, e.g. overuse of psychotropics and antibiotics in the 1970s and 1980s (such as people using them, when not indicated, for too long periods and habitual use of analgesics every morning without a medical reason). There has also been a lot of interest in the ‘underuse’ of medicines for major chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and elevated lipids (not starting or stopping treatment, ‘drug holidays’, taking only half of what is prescribed). Underuse, together with misuse or erratic use (wrong way of administration, taking with contraindicated medicines/food, etc.), has been one of the main focuses of patient adherence studies. From these studies we know something about the use of medicines and its clinical, social and economic consequences (see also Ch. 46).

Attempts to understand the medicine use behaviours of patients have been less common. However, more recently, a new research line has emerged using qualitative research methods such as in-depth interviews. These studies have focused more on what people think about their medicines, on their motives when taking or not taking them, their attitudes and beliefs about medicines and their experiences and expectations.

Some general consumer behaviour models have been used to explain non-prescription and prescription purchases. In one American study the medicine attributes that consumers rated as important included possible side-effects, physician recommendation, strength, prior use, price and the availability of generic versions. Medicines are not ordinary goods and consumers acknowledge this. According to one purchase theory, purchase motivations can also be characterized as being either transformational (positive) or informational (negative). Positive purchases are made to enhance or generate a positive situation or state of mind (e.g. clothes, music) and negative purchases to minimize or prevent negative situations (e.g. car service). Negative purchases are based on (rational) choices like perceived benefits and convenience (and therefore require more information), while positive purchases are more emotional and based on subjective appeal and positive shopping experience. Research has shown that OTC medicines and vitamins are neutral on the positive–negative dimension and oral contraceptives highly negative. This type of research is still not very well developed within the pharmaceutical field.

Like general illness behaviour, medicine use occurs in a social context. Choosing self-medication or consulting a physician to obtain prescription medicines is not based solely on symptoms or clinical aspects. The concept of social knowledge has been used to describe collective understanding, which is based on available information and nature of prior experiences. Family members, friends, work colleagues and their experiences, books and the media in addition to our own experiences, form the basis of social knowledge of medicines. Montagne has described some interesting social conceptions or fundamental principles about medicines in peoples’ minds, which he calls ‘pharmacomythologies’. It is a common belief among lay people that a specific medicine produces only one ‘main’ effect, which is positive. Other effects are considered as negative or ‘side’-effects. Likewise it is believed that a medicine produces the same main effect every time it is taken and in each person who takes it. This means that medicine effects are caused by the taken medicine and the effect of the medicine is a property residing inside the chemical compound and not a function of some change in a living organism. This easily leads to the belief that medicines cure the diseases.

The general health behaviour models and theories previously presented – such as the health belief model, theory of reasoned action, social learning theory, conflict theory and behavioural decision theory – can all be used to explain certain types of behaviour related to taking medicines. Basic decision-making and problem-solving skills are important components of patients’ seemingly rational and irrational behaviours. As presented earlier, the choices do not always follow the criteria of medical rationality, but may seem quite rational to the patient. It may be useful to consider rationality as a continuum rather than either/or. The degree of rationality is also influenced by social knowledge and the micro and macro environment, as described earlier, as well as the actual health problem.

Improving public understanding of medicines

During the last few years there have been different attempts both in developed and developing countries to improve knowledge and understanding about medicines among the general public. This can be seen as an attempt to influence and improve (from a medical point of view) social knowledge related to medicines and health in general. Campaigns such as ‘Ask about your medicines’ are good examples of this kind of activity. A more balanced partnership between consumer-patients and healthcare providers is one of the goals in such activities. A better appreciation of the limits of medicines and a lessening of the belief that there is a ‘pill for every ill’ are examples of the goals of such efforts.

The general public also needs to develop a more critical attitude towards advertising and other commercial information, which may often fail to give objective information about medicines. The use of medicines should be seen within the context of a society, community, family and individual, recognizing cultural diversity in concepts of health and illness or how medicines work. Improvement of the public’s knowledge about medicines should start at school. To facilitate informed choices on use of medicines, public education should be accompanied by supportive legislation and controls on availability of medicines. Non-governmental organizations, community groups and consumer and professional organizations should be involved in the planning and implementation of such programmes. Effective public education requires a commitment to and understanding of the need for improved communication between healthcare providers and patients. This should also be reflected in the basic and continuing education of healthcare personnel.

Prescribing

The process of prescribing has gained a lot of interest lately because of ever increasing medicine costs and the concern for rational prescribing from a clinical point of view (see also Ch. 17). Before this, social scientists had studied aspects such as the decision-making process in prescribing and the adoption of new medicines, using the ‘diffusion of innovations’ theory. Concern about prescribing habits is not new. In 1752 the famous Swedish physician and botanist Carl von Linne mentioned in a paper 21 different reasons for irrational prescribing, including factors like outdated knowledge, wrong diagnosis and chemical incompatibility, which are still relevant aspects when assessing rationality of prescribing. It is noteworthy that he used pharmacy records as his source of information.

Functions of prescriptions

Besides the pharmacological-therapeutic use, physicians may sometimes use medicine knowingly or unknowingly for other reasons too. According to Smith (2002), these can be either patient or physician centred. He has also presented a long list of latent functions of prescriptions in addition to their intended and recognized functions (method of therapy, legal document, record source and means of communication). Medicines may be used to stimulate the patient’s expectations for recovery and to meet patients’ expectations, e.g. the use of antibiotics for viral infections or boosting a patient’s morale in intractable diseases. The physician may also want to gain some time to diagnose the condition more precisely. The medicine also legitimizes the physician–patient relationship. The prescription is a sign of the physician’s power to heal and his efforts to try to heal and care for the patient. For the patient the prescription is a sign and symbol that they really are ill. Thus it also legitimizes their sick role and confirms that they have fulfilled one of the obligations of the sick role, to try to become well again (p. 30). Finally the physician uses the prescription to communicate to the patient that the office visit is over. Sometimes it may be difficult to distinguish between rational/pharmacological and non-pharmacological use of medicines. It can also raise ethical dilemmas, for example when purposely using placebos. Is the physician in this case cheating and/or behaving in a paternalistic way, when he should have an honest and trustful physician–patient relationship?

Choosing the right medicine

Therapeutic effect is the most important criterion when the physician decides which medicine to prescribe. When treating severe cases this aspect is even more important. A second consideration is the incidence and severity of side-effects. It has been shown that physicians tend to concentrate on a few serious side-effects. The medical situation often determines the acceptable level of side-effects. Economic aspects have a lower priority than the first two dimensions. Low cost or actual amount paid by the patient has a minor role due to reimbursement systems in place in most industrialized countries. If patients pay, the physician gives more attention to cost. Patient convenience and compliance may be decision criteria in situations when medically similar preparations are available, e.g. suppositories not being recommended when oral preparations are feasible. When prescribing for children, taste may be an important factor to consider (see Ch. 30).

In studies concerning the adoption of new medicines, it was shown that those physicians at the centre of a professional network tended to be innovators and started prescribing the new medicine at an early point. An early adopter in one therapeutic area might not necessarily be an early adopter in another therapeutic area. The opinion of colleagues is important; two physicians in close contact with each other tend to start a new medicine at the same time. Also the type of practice is an important factor. Physicians working alone adopt a new preparation more slowly than those working in group practices.

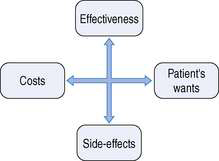

Barber has shown the dilemma the physician faces when choosing the right medicine. The problem is summarized in the question of how to find the right balance between the areas shown in Figure 4.1:

Models to study prescribing

Several studies have tried to find typical characteristics of prescribing physicians and their work settings that would explain both irrational prescribing and prescribing in general. Basically three types of models and approaches have been used:

There seems to be no general competency to prescribe rationally, since a physician may prescribe rationally in one area and irrationally in another. This could be expected if, for example, an ophthalmologist prescribed for cardiac conditions. Younger and more recently graduated physicians usually seem to prescribe more rationally than older physicians. It has been found that physicians with a negative attitude towards the use of medicines for social problems tend to prescribe fewer psychotropic medicines. The availability of non-medicine alternatives (e.g. cognitive therapy) reduces benzodiazepine prescribing. Also the social environment may be important in prescribing, for example during the Gulf War, benzodiazepine prescribing doubled in Israel compared with the period before and after the conflict. A more cosmopolitan attitude and a more critical attitude towards commercial information were associated with more careful prescribing of risky medicines in one study. Another study showed that ‘less rational prescribers’, defined as those with a high rate of benzodiazepine prescriptions, rely more on commercial information from the pharmaceutical industry than others. Professional satisfaction and reading professional material seem to translate into better prescribing.

Many physicians base their selection of medicines on their own experience, which may not be an accurate base for rational selection. The probability of observing rare but important side-effects is very small for an individual physician. The same biases that were mentioned earlier affecting patients’ decision making also affect physicians’ decision making. If they have high initial positive expectations before starting a new treatment, the outcomes will be interpreted in a way that meets these expectations. Negative aspects will not be accounted for. Only positive aspects transform into writing more new prescriptions. Irrational prescribing is also often legitimized by positive personal experiences from prescribing or using that medicine. High medical uncertainty may also contribute to irrational prescribing. On the other hand it may also result in seeking information from many sources to reduce this uncertainty.

Certain patient factors also influence the probability of receiving a prescription for psychotropic medicines. The most widely studied factors have been age and gender. The elderly are usually prescribed more than younger people, which may be a reflection of a higher rate of symptoms and psychological distress. There is also a tendency to write more repeat prescriptions for the elderly, partly reflecting the type of medication being prescribed. Women are prescribed psychotropic medicines more often, which is partly explained by a higher consultation rate. The sex of the physician does not seem to influence this tendency to prescribe more for women. Physicians’ expectations that women have more psychological–emotional disorders that can be treated successfully with benzodiazepines may also partly explain the difference.

Influencing prescribing

Providing information and employing educational programmes to change physicians’ prescribing behaviour has become an integral part of the pharmacist’s new role. Pharmacists participate in this kind of activity as part of their daily work, but also in formal trials or programmes in community and institutional settings. Several experimental studies have shown that pharmacists providing information and educating physicians produce positive effects on knowledge and attitudes, but the effects on prescribing behaviour have usually been modest. Providing physicians with printed material alone will not influence prescribing habits.

Individual feedback coupled with one-to-one education is the method most likely to be successful. Educational outreach or academic detailing has been studied and practised for the last 20 years. It follows the same principles as do medical representatives for pharmaceutical companies in their promotional activities. The basic principles are that physicians need to be interviewed in their own office where they are most receptive, the facilitators (often pharmacists) should be well presented and briefed, and the messages should be concise, clear and relevant to the prescriber. The programme should also be ongoing with repeat visits on a regular basis to maintain the contact and keep the messages up to date. The second major strategy includes managerial and regulatory activities such as use of limited lists (e.g. for reimbursement purposes), hospital or regional drug and therapeutic committees and formularies, structured medicine order forms (e.g. special forms for narcotics), drug utilization review (DUR) and treatment guidelines.

Pharmacies and the pharmacy profession

Historically a pharmacy has been the place for preparing and dispensing medicines. The first known pharmacy was established in the year 766 in Baghdad. In Europe the first pharmacies date back to the 11th century. In ancient times the same person acted as both doctor and pharmacist, i.e. diagnosed, prescribed and prepared the medicines for the patient. But in 1231 the German emperor and king of Sicily, Frederick II of Hohenstaufen in the edict of Palermo, legally separated the professions of medicine and pharmacy. Physicians were to diagnose and prescribe medicines, while pharmacists were to be responsible for preparing the medicines and providing these to the patients. Pharmacies were also designated to certain areas, where they had the monopoly of selling medicines. Certain physicians were also to oversee the work of pharmacists. Frederick also laid down rules about the education of healthcare professionals. These and other provisions given by him were the basis of legislation and practice of pharmacy in many European countries until the 20th century.

Elsewhere the distinction between the medical and pharmaceutical professions has not always been so clear and we can still find dispensing doctors today. However, in most countries, through the last centuries, pharmacists have acted as the ‘poor man’s doctor’, diagnosing and prescribing. It should be remembered that the classification of medicines into prescription and OTC medicines has happened only fairly recently. Some other countries have similar legislation in place, but it is not enforced. The system of dispensing doctors has been defended based on availability and grounds of patient convenience. The problems related to the system are an apparent conflict of interest, which is present when the income of the physician depends on the volume and price of medicines prescribed. This problem has been highlighted in Japan, which also has one of the highest costs of medicines per capita in the world and where prescription medicines are mainly distributed by physicians. The same conflict of interest is often mentioned in the context of the professional and business roles of the pharmacist, especially concerning sales of non-prescription medicines.

There has been much discussion about the occupational status of pharmacists. Is pharmacy a true profession or not? Two major approaches have been used by academics in trying to answer the question. One approach is to look at the functions pharmacists perform for society, asking if they are vital for the society. The second approach is to look at certain characteristic traits of the occupation and determine whether they fulfil typical traits of a profession. During the last 50 years, different traits have been mentioned by different academics, but there are some common ones. In the 1950s, Lewis & Maude mentioned the following traits that characterize a profession:

Most authors agree that the basic traits of a learned profession are advanced and lengthy training in a highly specialized body of knowledge. This knowledge is to be used in the service of society and mankind. Research and abstract reasoning are the ways of expanding this unique body of knowledge. The services provided by a profession are also related to the degree of impact or danger they may have on individuals or society. Besides the expert knowledge the professional possesses, he must also exert his professional judgement to the benefit of the client. Co-workers in the same or related occupations acknowledge the level of expertise of the profession, which is also important in legitimating the practice. There is also a certain level of trust that the public must place in the work performance of the professional. Professionals themselves define which kind of activities are allowed and what privileges members may claim. They also define, through ethical codes and legislation, which they have often themselves had an opportunity to draw up, the type of controls that guarantee the social privileges given to them (like autonomy of action, monopoly of practice, remuneration) are not abused.

Role of pharmacists

The origin of the pharmacy profession was in the unique knowledge base and skills needed to compound a drug product. With the growth of the pharmaceutical industry, this function decreased throughout the 20th century, especially in the 1950s and 1960s. Today it is impossible for the individual pharmacist in the pharmacy to compound similar products to those of the pharmaceutical industry. Also the pharmacist’s traditional role of procuring and storing crude drugs has vanished. As the pharmacist’s knowledge about the proper preparation, storage and handling of medicines is still greater than any other professional group, the quality assurance aspects of medicines are still their responsibility. Both the society and the profession have defined that the duty of the profession is to ensure that the medicines provided to patients are safely and accurately dispensed. The question raised in the 1960s was whether the status of pharmacy as a profession could be maintained if it were based solely on storing and distributing medicines. The discussion was referred to as ‘the profession in search of a role’. This discussion was one contributory factor in the rise of the clinical pharmacy movement in the USA starting in the 1960s. The debate about the pharmacist’s role has continued ever since, with new developments like the pharmaceutical care movement and the ‘extended role’ of the pharmacist in the 1990s. Today there seems to be some kind of consensus among pharmacy spokespersons that the future of pharmacy as a profession lies in pharmaceutical care. In different countries, however, there seem to be different interpretations about what pharmaceutical care is all about. Another question is to what extent the profession at the grass-root level has embraced this philosophy and to what extent it is being practised in everyday pharmacy practice.

International guidelines for good pharmacy practice by the FIP

The International Pharmacy Federation (FIP) has issued its guidelines for good pharmacy practice (GPP), stating that the mission of pharmacy practice is to provide medications and other healthcare products and services and to help people and society to make the best use of them. The concept of GPP is based mainly on the concept of pharmaceutical care. The patient and community are the primary beneficiaries of the pharmacist’s actions and the pharmacist’s first concern must be the welfare of the patient in all settings. The core of pharmacy activity is the supply of medication and other healthcare products of assured quality, appropriate information and advice to the patient and monitoring the effects of their use. From an international perspective, a rather new aspect is the quest for the pharmacist’s contribution to the promotion of rational and economic prescribing and appropriate medicine use. According to GPP the objective of each element of pharmacy service should be relevant to the individual, clearly defined and effectively communicated to all those involved.

In satisfying GPP requirements, professional factors should be the main philosophy underlying practice. Economic factors are also important, but they should not be the driving force. Pharmacists should give their input to decisions on medicine use, and a therapeutic partnership with physicians and good relationships with other pharmacists are important. Pharmacists are also responsible for the evaluation and improvement of the quality of services given. There is a need for keeping patient profiles and to record pharmacists’ interventions (see also Ch. 15). Pharmacists need independent, comprehensive, objective and current information about medicines. They should also accept personal responsibility for lifelong learning and educational programmes should address changes in practice. National standards of GPP need to be put in place and adhered to.

According to the guidelines there are four main elements of GPP: promotion of good health, supply and use of medicines, self-care and influencing prescribing and medicine use. It also encompasses cooperation with other healthcare professionals in health promotion activities, including the minimization of abuse and misuse of medicines. Professional assessment of promotional materials for medicines should also be carried out and evaluated as well as information about medicines and health care disseminated to the public. The involvement in all stages of clinical trials is also recommended. The guidelines include further areas within the four main elements that need to be addressed, such as national standards for facilities for confidential conversation, provision of general advice on health matters, involvement in health campaigns and the quality assurance of equipment used and advice given in diagnostic testing. In the supply and use of prescribed medicines, standards are needed for facilities, procedures and use of personnel. Assessment of the prescription by the pharmacist should include therapeutic aspects (pharmaceutical and pharmacological), appropriateness for the individual and social, legal and economic aspects.

Furthermore, national standards are needed for information sources, competence of pharmacists and medication records. Advice should be given to ensure that the patient receives and understands sufficient oral and written information. It is also important to have standards on how to follow up the effect of prescribed treatments and the recording of professional activities. When trying to influence prescribing and medicine use, general rational prescribing policies and national standards are needed. In research and practice documentation, pharmacists have a professional responsibility to document professional practice experience and activities and to conduct and/or participate in pharmacy practice research and therapy research. These guidelines form an international consensus on current practice of pharmacy and point to the direction for national guidelines and efforts to improve it.

Outcomes of medical treatment

Evaluation and outcomes research

Evaluation and outcomes research are fairly new topics within pharmacy. They are integral elements of pharmaceutical care and much more effort needs to be put into these aspects of pharmacy practice and research in the future. Evaluation has been defined as making a comparative assessment of the value of the intervention, using systematically collected and analysed data, in order to make informed decisions about how to act or to understand causal mechanisms and general principles. One important aspect from society’s point of view is the question ‘What are we getting for our money?’ According to the model originally proposed by Donabedian, evaluation of health care can focus on:

Traditionally evaluation has focused on structure and process and to a lesser extent on outcomes. More recently a whole new research field has emerged within health care called ‘outcomes research’.

One difficulty in health-related outcomes research is to demonstrate the linkages between the three elements of the model: structure–process–outcome. For example, will a new computer-based patient medication record system in the pharmacy (structure) improve the follow-up of a patient (process), so that the pharmacist is able to detect more efficiently a medicine-related problem in the use of the antihypertensive medicine with the outcome of lowered blood pressure and the patient feeling better and living a healthier, longer and happier life (outcome)? Even if there is little empirical evidence, it is the general view that good structure leads to a more appropriate process resulting in better outcomes.

A general observation in the healthcare field is that we still lack evidence of many widely used procedures and interventions. Since the mid 1960s new medicines have undergone clinical trials and an official evaluation through the registration process. This does not mean that all medicines currently on the market or being marketed are safe, effective, economic or appropriate. Furthermore, even if we have only high-quality medicines on the market, the outcome of medical treatment is ultimately dependent on how the medicines are being prescribed by physicians and used by patients.

Within the pharmaceutical field a more comprehensive framework has been proposed by Kozma and his colleagues. This model, named ECHO, classifies outcomes in three categories: economic, clinical and humanistic outcomes. Clinical outcomes have been defined as medical events that occur as a result of the condition or its treatment. Economic outcomes are the direct, indirect and intangible costs compared with consequences of medical treatment alternatives. Humanistic outcomes include well-being, health-related quality of life and patient satisfaction.

Health-related quality of life

The primary objective of health care is to improve patients’ quality of life. To what extent this objective is achieved often remains unanswered. This may be due to lack of proper measures, the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare providers or some other factor. The central feature and objective of pharmaceutical care is to achieve outcomes by identifying, solving and preventing medicine-related problems that will improve a patient’s quality of life. In experimental settings this has been shown to be the case. To what extent it is achieved in ordinary everyday practice is still an open question.

A classic list of outcomes in medical care has been crystallized in the ‘five Ds’ – death, disease, disability, discomfort and dissatisfaction. These include a wide range of different aspects, but are all negative terms. They will give partial answers to the questions about the quality of life of the patient, but are not sufficient to cover all aspects of quality of life. The term ‘health-related quality of life’ has been used quite differently in the literature and daily practice. Explicit definitions are quite rare because of the multidimensionality of the concept. The domains of health-related quality of life usually include functional health (physical activity, mobility and self-care), emotional health (anxiety, stress, depression, spiritual well-being) social and role functioning (personal and community interactions, work and household activities), cognitive functioning (memory), perceptions of general well-being and life satisfaction, and perceived symptoms.

Health-related quality of life has been measured with disease-specific instruments and general or generic instruments, e.g. health profiles and measures based on utilities. Disease-specific instruments provide a greater detail concerning functioning and well-being in that particular disease. The disease-specific measures (e.g. those used in hypertension and asthma) can also be further categorized as population specific (e.g. elderly), function specific (e.g. sexual) and condition specific (e.g. pain). Examples of these instruments include the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire and the Diabetes Quality of Life Questionnaire.

The generic measures include health profiles, which constitute a number of questions covering the different aspects giving separate scores for each domain of life mentioned earlier. Examples include the Nottingham Health Profile, Sickness Impact Profile, McMaster Index and SF-36. The advantage of health profiles is that they provide a comprehensive array of scores that is multidimensional. If the measure used is sensitive enough, through the profile we may be able to distinguish, for example, when a medicine influences the emotional domain while having no effect on the functional health domain.

The utility-based measures incorporate specific patient health states while adjusting for the preferences (utilities) for the health state. The outcome scores range from 0 to 1, where 0 represent quality of life associated with death and 1 represents perfect health. The preferences have been empirically tested in different populations and been through a validation process. These utility-based measures have been extensively used in pharmacoeconomics research and more specifically in cost–utility analysis (see Ch. 19).

The most accurate and comprehensive end result may be achieved by using both a generic and a disease-specific measure when possible. The focus in current medicine is more on patient-perceived impact on long-term morbidity than on limiting mortality. It is good to remember that medicines can both increase and decrease the quality of life. The goal of medical therapy is to improve health and make patients feel better. Physiological measures may change without people feeling any better. Treatment of mildly elevated blood pressure is a good example of this. Nevertheless, treatment may improve subjective health without any measurable changes in clinical parameters. There may also be a trade-off between positive treatment outcomes and adverse events.

Client and patient satisfaction

An important aspect when measuring the outcomes of pharmacy practice and pharmaceutical interventions is the satisfaction of clients and patients. Measurement of client satisfaction can be an important tool in quality assurance of pharmacy practice (see also Ch. 11). There are difficulties in defining the quality of pharmacy services. One approach is to divide the quality into a technical dimension (i.e. what is offered) and a functional dimension (i.e. how it is offered). Different proposals have been made to cover different aspects of service provision in general. One comprehensive model is that by Parasuram. He distinguishes between 10 different dimensions: reliability, responsiveness, competence, access, courtesy, communication, credibility, security, understanding/knowing the customer and tangibles. Hedvall has presented a somewhat simplified model. She has proposed four dimensions: professionalism, commitment, confidentiality and milieu, which also contain the essence of what Parasuram has proposed. Customers may have difficulties in distinguishing between all 10 dimensions and some of them tend to overlap. The proposed dimensions represent important aspects to both prescription and self-care clients visiting the pharmacy. These aspects also have a direct linkage to communication skills and pharmaceutical care.

Measurement of patient satisfaction has usually focused more specifically on aspects in providing care. Cleary & McNeil have listed the following dimensions that are typically covered in the measurements of patient satisfaction: accessibility and availability of care, convenience, technical quality, physical setting, efficacy, personal aspects of care, continuity and economic aspects. In these dimensions we can distinguish a technical or cognitively based evaluation of the services offered and also an emotional or affective aspect – how well they are offered. The significance of client satisfaction can be correlated to patronage, patient adherence, and ultimately to the survival of the pharmacy profession.