Chapter 25 Dispensing techniques (compounding and good practice)

Introduction

This chapter deals with some of the practical aspects of good pharmacy practice. It will concentrate on the small-scale manufacture of medicines from basic ingredients in the community or in hospital pharmacy. This process is called compounding or extemporaneous dispensing. In addition, good practice which applies to all aspects of dispensing will be considered.

In modern practice, most medicines are manufactured by the pharmaceutical industry under well controlled conditions and packaged in suitable containers designed to maintain the stability of the product (e.g. sealed in an inert atmosphere). Therefore, extemporaneous dispensing, which cannot be as well controlled, should only be used when such products are unavailable. Reasons for unavailability of products may include:

The pharmacist undertaking extemporaneous dispensing has a responsibility to maintain equipment in working order, ensure that the formula and dose are safe and appropriate and that all materials are sourced from recognized pharmaceutical manufacturers. There are also requirements concerning calculations, maintaining good records and labelling regulations. Any staff involved in the process should be adequately trained. These requirements should all be incorporated within standard operating procedures (SOPs).

It is important to remember in any dispensing process that the end product is going to be used or taken by a person or an animal. It is therefore important that the medicine produced is of the highest achievable quality. This, in turn, means that the highest standards must be applied during the preparation process. If we expect quality assurance procedures to be important in the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry then the same careful attention to detail must be applied to small-scale production, i.e. extemporaneous dispensing.

The working environment and procedures

Organization

The working environment has a considerable influence on a worker’s efficiency. However, an individual worker, such as a dispenser, can improve efficiency and safe working by developing a tidy and organized method of working. For example, a dispensing bench cluttered with several containers all containing different ingredients makes selection of the correct ingredient more difficult and more prone to error. Ingredients should always be returned to their appropriate shelf/cupboard when the required quantity has been measured out. Thus a safe system of working is essential for a dispensary and the development and use of SOPs should be followed. Additionally, health and safety regulations must be applied in the dispensary.

Cleanliness/hygiene

The dispensing bench, the equipment and utensils, and the container which is to hold the final product must all be thoroughly clean. Lack of cleanliness can cause contamination of the preparation with other ingredients. For example, a spatula which has been used to remove an ingredient from one container will adulterate subsequent containers if not washed before being used again. Cleanliness will also minimize microbial contamination.

Similarly dispensing staff should have a high standard of hygiene and hand washing facilities should be readily available. Hence, a clean white overall should be worn and be kept fastened up since open overalls are a potential safety hazard. Open overalls may result in clothes becoming stained if any spillages occur. Hair should be tied back and preferably covered with a disposable hat/cap and any skin lesions covered with a dressing. Disposable gloves should be worn during preparative work and discarded afterwards. Consideration should be given to the use of masks if volatile substances or fine powders are to be handled.

Documenting procedures and results

Keeping comprehensive records is an essential part of the dispensing process. Records must be kept for a minimum of 2 years (ideally 5 years) and include the formula and any calculations, the ingredients and quantities used, their sources, batch numbers and expiry date. All calculations or weights/volumes should be checked by two people and recorded. Any substances requiring special handling techniques or hazardous substances should be recorded with the precautions taken. The record for a prescribed item should also include the patient and prescription details and date of dispensing. A record must be kept of the personnel involved, including the responsible pharmacist.

All SOPs should be available and adhered to. Any deviations from a SOP should be recorded.

Equipment

Not only is the selection of the correct equipment or ‘tools’ for the job essential, but the tools must also be used in the correct way and maintained in good order to ensure performance is unimpaired.

Weighing equipment

Nowadays, weighing equipment can be divided into non-automatic and automatic weighing equipment. Non-automatic weighing equipment requires an operator to place and/or remove the items from the balance pan. Such weighing equipment can be a mechanical beam balance, which has a pan on one end of the beam for weights and a pan on the other end of the beam for the material to be weighed (Fig. 25.1) or it can be an electronic top-pan balance, in which case the substance to be weighed is placed on the pan and an electronic display gives the weight. Automatic weighing equipment is designed to automatically fill a package to the required weight without the intervention of an operator. Such equipment is used in the pharmaceutical industry, but unlikely to be used for extemporaneous dispensing. Whichever type of weighing equipment is used, it must be suitable for its intended use and be sufficiently accurate. In the UK, weighing equipment must be calibrated in metric units and must be marked with maximum and minimum weights that can be weighed.

General rules for the use and maintenance of weighing equipment

Balances can give incorrect readings because of poor practice or misuse. The following points are important to ensure accurate weighing:

Use of a beam balance

As well as the above, the following ‘rules’ apply to the use of a beam balance:

Use of top-pan balance

In addition to using the balance correctly there are one or two other rules which should be observed when weighing, to ensure good dispensing practice. These are:

Measuring liquids

Liquid measures

All measures for liquids must comply with current weights and measures regulations and should be stamped accordingly. Traditionally, conical measures (Fig. 25.2) have been used in dispensing, although, if not used carefully, they can be less accurate than cylindrical measures.

Whichever type of measure is chosen, always ensure the following:

Example 25.1

25 mL of glycerol is required.

Because of the viscosity it is difficult to remove it completely from the measure.

It is therefore advisable to measure, say, 35 mL and pour off the 25 mL required, ensuring that 10 mL is left in the measure. Remember to allow sufficient time for the liquid to drain back down.

When measuring liquids it is important to observe two simple rules which ensure good dispensing practice:

Measuring small volumes

It is important to select the correct equipment when measuring. The minimum measurable volume for a 10 mL conical measure is 1 mL. Graduated pipettes can be used for volumes from 5 mL down to 0.1 mL. For volumes smaller than this, a trituration should be made. The viscosity of the substance being measured should also be considered.

Correct use of pipettes

Pipettes can be either the ‘drainage’ or ‘blow-out’ variety. A rubber bulb or teat should be used. Never use mouth suction.

Nowadays, semi-automatic pipettes can be used for dispensing.

Mixing and grinding

Mortar and pestle

The mortar (bowl) and pestle (pounding device) are used to reduce the size of powders, mix powders, mix powders and liquids, and make emulsions. Two types, each available in a range of sizes, are used.

Glass mortar and pestle

These are generally small and therefore cannot be used for large quantities of material. The smooth surface of the glass reduces the friction which can be generated, so they are only suitable for size reduction of friable materials (such as crystals). They are useful for dissolving small quantities of ingredients, for mixing small quantities of fine powders and for the mixing of substances such as dyes which are absorbed by and stain composition or porcelain mortars.

Porcelain or composition mortars and pestles

These are normally larger than the glass variety and have a rougher surface. They are ideal for size reduction of solids and for mixing solids and liquids, as in the preparation of suspensions and emulsions.

Size reduction using a mortar and pestle

Selection of the correct type of mortar and pestle is vital for this operation. A flat-bottomed mortar and a pestle with a flat head should be chosen. A flat-headed pestle in a mortar with a round bottom, or vice versa, will mean a lot of wasted effort.

Using a mortar and pestle for mixing powders

Adequate mixing will only be achieved if there is sufficient space. Overfilling of the mortar should therefore be avoided. The pestle should be rotated in both right and left directions to ensure thorough mixing. Undue pressure should not be used, as this will cause impaction of the powder on the bottom of the mortar.

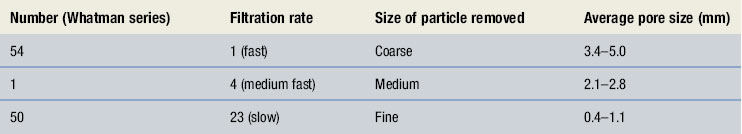

Filters

There are occasions when clarification of a liquid is required. Pouring the liquid through muslin can carry out coarse filtration, or ‘straining’. Where a finer degree of filtration is required, filter paper, sintered glass filters or membrane filters should be used. Filter paper and membrane filters come in different grades and selection of the correct grade is determined by the size of the particles to be removed. Details of grades of filter paper are found in Table 25.1. Filter paper has the disadvantages of introducing fibres into the filtrate and may also absorb significant amounts of active ingredient. This is less likely with membrane filters.

Heat sources

In the dispensing process it may be necessary to heat ingredients, e.g. melt semi-solids in the preparation of ointments/creams, warm liquids to aid dissolution of solids.

Bunsen (gas) burners

Bunsen burners are useful for small-scale heating if a gas supply is available. They should always be placed on a heat-resistant mat and care taken by the operator to avoid burns. When heating with a Bunsen burner, a blue flame should be used.

Water baths

These are used to provide gentle heat, for example when melting ointment bases or preparing suppositories. Normally the materials to be heated are placed in a porcelain evaporating basin and placed over the hot water in the water bath. There is no necessity to have the water boiling vigorously – this does not increase the heat but does increase the risk of scalding.

Manipulative techniques

Selection of the correct equipment and using it appropriately is fundamental to good compounding. Several basic manipulative techniques may require practice.

Mixing

The goal of any mixing operation should be to ensure that even distribution of all the ingredients has occurred. If a sample is removed from any part of the final preparation, it should be identical to a sample taken from any other part of the container (Aulton 2007).

Mixing of liquids

Simple stirring or shaking is usually all that is required to mix two or more liquids. The degree of stirring or shaking will be dependent on the viscosities of the liquids. Thus mixing liquids of low viscosities will require only minimal stirring, while mixing two liquids with high viscosities will need more vigorous agitation.

Mixing solids with liquids

Particle size reduction should always be considered. This will either speed up the dissolution process or improve the uniform distribution of the solid throughout the liquid. When a solution is being made, a stirring rod will be adequate. However, a suspension will require a pestle and mortar.

Mixing solids with solids

As well as the correct use of a mortar and pestle, the amounts of material being mixed together must be considered. Where the quantity of material to be mixed is small and the proportions are approximately the same, the materials can be added to an appropriately sized mortar and effectively mixed. Where a small quantity of powder has to be mixed with a large quantity, in order to achieve effective mixing it must be done in stages:

Mixing semi-solids

This usually occurs in the preparation of ointments where two or more ointment bases may be mixed together. If all the ingredients are semi-solids or liquids, they can be mixed together by rubbing them down on an ointment slab, using a spatula. If there is a significant difference in the quantities of the ingredients, a ‘doubling-up’ process should be used. An alternative method is the fusion method.

The fusion method

When using the fusion method, do not be tempted to add any solid active ingredients to the basin before the bases have set. Addition of any further ingredients is best done by rubbing down on an ointment slab. Further details of methods used in the preparation of ointments can be found in Chapter 33.

Tared containers

Liquid preparations should as far as possible be made up to volume in a measure. There are, however, instances when accurate transfer of the preparation to the final container is difficult; for example with some suspensions it can be almost impossible to remove all the insoluble ingredients when pouring from one container to another. Emulsions and viscous preparations can also be difficult to transfer accurately. In these cases a tared container should be used.

To tare a bottle

A volume of water identical to the volume of the product being dispensed is accurately measured. This is then poured into the chosen medicine container and the meniscus marked with the upper edge of a small adhesive label, effectively making the bottle into a single-point measure. The container is then emptied and allowed to drain thoroughly. The preparation is then poured into the container and made up to volume, using the tare mark as the guide. Remove the tare label.

This procedure should be used with discretion and only in situations when major inaccuracies would occur in the transfer of liquids. In addition, it should only be used when water is present as one of the ingredients. Putting medicines into a wet bottle is generally considered bad practice.

Ingredients

All ingredients must be sourced and obtained from reputable suppliers and be of a quality suitable for the preparation and dispensing of pharmaceutical products. Additionally, ingredients must be suitably stored to preserve stability and integrity. For example, regular checks on expiry dates of stored products should be made and any ingredient outside its expiry date should be discarded. Hence arrangements should be made for the regular collection and disposal of pharmaceutical waste (see Ch. 43). Some ingredients may require special storage conditions and these should be provided. Many pharmaceutical ingredients and products require storage in a refrigerator, which should be fitted with a maximum/minimum thermometer and regularly checked on a daily basis.

Selection

When dispensing, selection of the correct product is vital. The label on each container must be read carefully and checked to ensure that it contains the required product. There are many examples of drugs and preparations where names may be misread if care is not taken; examples include folic acid and folinic acid, cefuroxime and cefotaxime. Further examples are given in Chapter 23. Extemporaneously dispensed medicines may contain several ingredients, so the potential for error by wrong selection is increased.

Some ingredients of extemporaneously dispensed medicines may occur in a variety of forms or a synonym is used.

Variety of forms

Coal tar, for example, is available as coal tar solution, strong coal tar solution and coal tar. Clearly if all three containers are on the same shelf, the wrong item may be selected by accident. Some other materials where confusion can occur are listed in Table 25.2. This list is not meant to be comprehensive and only contains common exemplars. The only foolproof method of avoiding errors is to read the container label carefully.

Table 25.2 Some substances which occur in a variety of forms

| Substance/form | Use |

| Light magnesium carbonate | Because of its lightness and diffusible properties, it is used in suspensions |

| Heavy magnesium carbonate | Normally used in bulk or individual powders |

| Light kaolin | Used in suspensions |

| Heavy kaolin | Used in the preparation of kaolin poultice |

| Precipitated sulphur | This has a smaller particle size than sublimed sulphur and is preferred in preparations for external use, e.g. suspensions, creams and ointments |

| Sublimed sulphur | Slightly gritty powder which does not produce such elegant preparations as precipitated sulphur |

| Yellow soft paraffin | Used as an ointment base |

| White soft paraffin | Bleached yellow soft paraffin normally used when the other ingredients are not strongly coloured |

Synonyms

Some substances used in dispensing may be known by more than one name. An awareness of this is useful when selecting ingredients. Some examples of commonly used materials are given in Table 25.3. This table is not intended to be comprehensive.

Table 25.3 Example of substances with synonyms

| Substance | Synonym |

| Wool fat | Anhydrous lanolin |

| Hydrous wool fat | Lanolin |

| Hard paraffin | Paraffin wax |

| Compound benzoic acid ointment | Whitfield’s ointment |

| Macrogol 2000 | Polyethylene glycol 2000 or PEG 2000 |

| Theobroma oil | Cocoa butter |

Problem solving in extemporaneous dispensing

For extemporaneous dispensing, it is helpful if a method detailing how to prepare the product is available. Methods for ‘official’ preparations can sometimes be found in reference sources such as the Pharmaceutical Codex. However, on many occasions no method is available. In such a situation, it may be helpful to consider similar formulas in reference sources. Additionally, the application of simple scientific knowledge, especially of physical properties, is often all that is needed. The following gives an example of how this is done.

Putting theory into practice

Solubility

Always check the solubility of any solid materials. If they are soluble in the main vehicles, then a solution is likely to be produced. If solubility is limited to one liquid, this will assist in achieving uniform dose distribution. Solution will be achieved more quickly if the particle size is small and so size reduction should be considered for any soluble ingredients which are presented in a lumpy or granular form. If the substance is not soluble, then a suspension will need to be produced. Whether a suspending agent will be required should be considered (see Ch. 31). Where one material is an oil and another aqueous, it is likely that an emulsifying agent will be required to produce an emulsion (see Ch. 32).

Volatile ingredients

If an ingredient is volatile then it should be added near the end of the dispensing process. If it is added too early, much may be lost due to evaporation.

Viscosity

The viscosity of a liquid will have a bearing on how it is measured, i.e. is a pipette or measure suitable, or should it be measured by difference, and how will it be incorporated? (See Example 25.1.)

Expiry date

All extemporaneously prepared products should be awarded an expiry date. Ideally stability studies should be undertaken in order to predict an accurate shelf life for all products. This is not usually possible for ‘one-off’ preparations and most hospital pharmacies have guidelines based on previous stability studies. Further information on stability and appropriate expiry dates is found in Chapter 43.

Example 25.2 illustrates how some very simple facts can be applied to develop an accurate method of preparation.

Example 25.2

The following prescription is received:

Sodium bicarbonate ear drops BP

Counting devices

Tablets and capsules form a large proportion of the medicines which are dispensed today. Most are presented in patient packs or original packs, but occasionally tablets/capsules are supplied in bulk packs and the prescribed amount is counted from them.

Various methods can be used for this counting:

These methods all have their advantages and disadvantages and it is up to each pharmacist to select the most appropriate for the task, depending on the equipment available. Whichever method is selected it must be noted that the medicines must not be touched by hand (wear disposable gloves to avoid touching the formulation). The equipment should also be carefully cleaned before use (again wear gloves), as powder left from one product could cause contamination of the next one.

The manual method

This consists of pouring the product on to a piece of clean white paper which overlaps another piece. The products are then counted off in tens, using a spatula, on to the second piece of paper. This is formed into a small funnel and the tablets or capsules poured into the appropriate container.

Concentration must be maintained or the wrong quantity may be counted. Remember to wear gloves.

Counting triangles and capsule counters

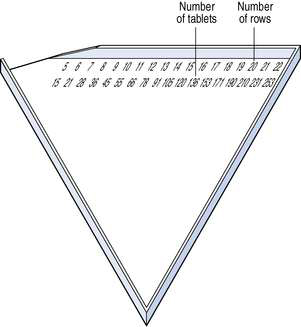

Counting triangles

This is a fast, accurate and simple way to count tablets. The triangles are made of either metal or plastic. Two rows of figures are printed or etched along the edge. The top row of figures refers to the number of rows and the numbers below refer to the number of tablets contained in that number of rows. This is illustrated in Figure 25.3. Tablets are poured into the triangle and rows completed using a spatula. Any excess of tablets is returned using the spatula and the correct number poured into a tablet bottle.

Capsule counters

Because of their shape, capsules cannot be counted on triangles. A capsule counter, illustrated in Figure 25.4, is a metal tray which consists of 10 rows of grooves. The capsules are poured on to the tray and, using a spatula, lined up in the grooves. Each complete row will contain 10 capsules so the number of complete rows multiplied by 10 gives the number of capsules.

Capsule counters are not as easy to manipulate as triangles but are an efficient method for counting capsules. Studies testing the accuracy of the various counting methods have shown these two devices to be the best.

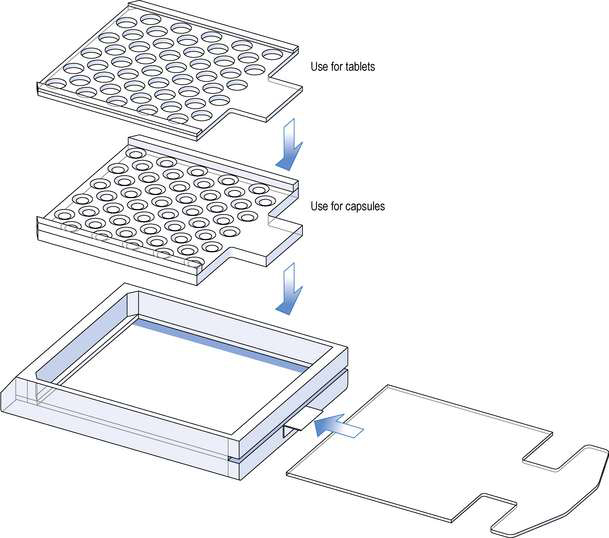

Perforated counting trays

These are normally made of clear perspex. They consist of a rectangular box with a sliding lid, on top of which is placed a perforated tray. Each box is supplied with several trays with different sized perforations to accommodate different sizes and types of products (Fig. 25.5). These trays can be used to count tablets or capsules.

The main disadvantage is the necessity to change the trays for different products.

Electronic counters

There are two types of electronic counter, those which use the weight of the product to count and those which count using a photoelectric cell.

Electronic balances

Between 5 and 20 of the required dosage form is put on a balance pan or scoop. From the weight of this reference sample, a microprocessor within the device calculates the total number of dosage forms, as they are added. The main problem with this type of device is that for accurate counting, it requires consistent uniformity of the weight of the tablets or capsules. There can be problems with accuracy when counting sugar-coated or very small tablets.

Photoelectric cell counters

The product to be counted is poured through a hopper on the top of the machine. The tablets or capsules are then channelled into a straight line and counted as they interrupt the beam of light to the photoelectric cell. This is an efficient method of counting and these devices are widely used. They are not without their problems, however:

Severe allergic reactions can be initiated in previously sensitized persons by very small amounts of certain drugs and of excipients and other materials used in the manufacture of tablets and capsules. In order to minimize that risk, counting devices should be carefully cleaned after each dispensing operation involving any uncoated tablet, or any coated tablet or capsule from a bulk container holding damaged contents. As cross-contamination with the penicillins is particularly serious, special care should be taken when dispensing products containing those drugs.

This type of device should therefore be reserved for counting only coated tablets or capsules or for prepacking operations.

Automated dispensing systems

There are a number of automated dispensing systems available of varying degrees of sophistication. They are linked to a computer, which is used for label production and creation of the patient medication record. The computer ‘orders’ counting of loose tablets or capsules (using a photoelectric cell counter) into a suitable container, or retrieval of a prepackaged medicine. Some incorporate bar-coding technology to improve speed and accuracy. Tests indicate that these machines are less prone to error than human dispensing.

Conclusion

Developing good practice takes time and requires attention to detail.