34 The Abdomen of the Pig

A thick layer of subcutaneous fat obscures most underlying features of the trunk making it generally impossible to recognize the extent of the flank on simple inspection. Occasionally, and then most often in heavily pregnant sows, there is a slight bulging behind the last rib. At the other limit, the thigh and flank fold conceal the caudal part of the abdomen where it tapers to its junction with the pelvis.

THE MAMMARY GLANDS

In sows the ventral contour of the abdomen is made irregular by the presence of the mammary glands, of which there are almost invariably seven pairs arranged in a double row extending from the thorax to the groin (Figure 34–1; see also Figure 33–1). Each gland is pendulous and, though confluent with its neighbors at its base, is otherwise clearly defined. Those at the caudal end of the series are generally the largest, but the cranial ones are the most productive.

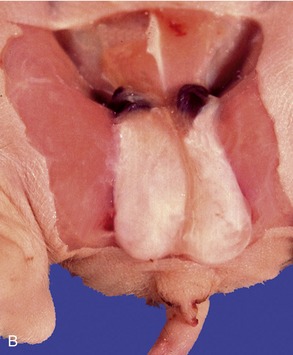

The teats are elongated and cylindrical; each has two openings at its tip (Figure 10–31, B) leading to independent gland units. Some teats tend to project a little to the side, and because sows generally suckle while laterally recumbent, certain teats may not be readily accessible to the litter; some glands may therefore be little used and regress early. On the other hand, when the litter is large some piglets may find it hard to obtain an adequate share of milk and may fail to grow normally.

The blood supply is provided by local vessels: the internal thoracic and the cranial and caudal superficial epigastric arteries. The venous drainage is satellite. Lymph from the first two (or three) pairs of glands leads to ventral superficial cervical nodes, and that from the remainder leads to the superficial inguinal.

THE ABDOMINAL WALL

The construction of the abdominal wall follows the common pattern in its essential features. The cutaneous muscle of the trunk is extensive as well as thick ventrally where it passes through the flank fold. It leaves the abdominal floor uncovered, except for cranial (and inconstant caudal) preputial muscles. The deep fascia is without the elastic component that in the larger species imparts the characteristic yellow color. The three muscles of the flank show few distinctions of importance, and because surgical experience has shown that their fleshy parts tend not to hold sutures well, attention can be concentrated on the aponeuroses. The site favored for laparotomy is an almost wholly tendinous strip, about 10 cm long and barely 5 cm wide, situated along the lateral edge of the rectus muscle and deep to the flank fold.

The alternation of the abdominal muscles with layers of fat accounts for the characteristic appearance of the bacon rasher.

Umbilical hernias used to be common in this species. If a satisfactory closure of these defects is to be obtained in the abdominal wall, it is first necessary to reflect the cranial part of the prepuce. This exposes the wide part of the linea alba that alone provides sufficient breadth of tissue to allow overlapping and suture of the margins of the hernia ring.

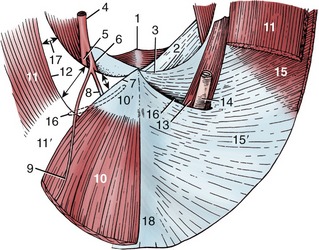

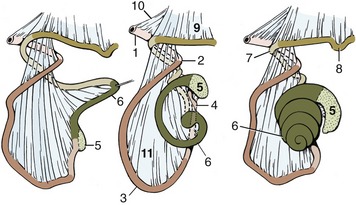

The other region of practical interest is provided by the inguinal canal. In principle, this conforms to the general arrangement: it is a potential space between the two oblique muscles (for details see Figure 34–2). The deep ring, the entry to the canal, is found between the caudal border of the internal oblique and the aponeurosis of the external oblique (see Figure 2–27). The superficial opening is the split in the external aponeurosis that defines its division into pelvic and abdominal parts. The caudal part of the canal is very short, but it widens cranially as the result of the divergent orientations of the deep and superficial inguinal rings: the deep ring is angled craniodorsally, while the superficial ring is angled slightly ventrally as well as cranially. Anomalies of gubernacular development are common in pigs; if the canal is dilated (Figure 34–3), they are predisposed to inguinal hernia. The hernia generally takes the form of a loop of small intestine that stretches the vaginal ring and forces a passage into the tunica vaginalis, which raises a subcutaneous swelling between the thighs. These hernias make castration of affected animals requiring attention.

Figure 34–2 Inguinal canal of the male made visible on the interior surface of the caudal abdominal wall; semischematic, cranial view. 1, Pelvic symphysis; 2, prepubic tendon; 3, caudal border of external oblique aponeurosis (“inguinal ligament”); 4, external iliac artery; 5, femoral artery; 6, deep femoral artery; 7, lateral border of rectus tendon; 8, external pudendal artery; 9, caudal epigastric artery; 10, rectus abdominis; 10′, rectus tendon; 11, muscular part of internal abdominal oblique; 11′, aponeurotic part of internal abdominal oblique; 12, caudal free border of internal abdominal oblique; 13, cremaster; 14, tunica vaginalis and spermatic cord; 15, muscular part of external abdominal oblique; 15′, aponeurotic part of external abdominal oblique; 16, superficial inguinal ring; 17, deep inguinal ring (arrows); 18, linea alba.

THE ABDOMINAL ORGANS

THE SPLEEN

The bright red, elongated, and straplike spleen is oriented more or less vertically under the protection of the more caudal ribs on the left side (Figure 34–4/6). It follows the greater curvature of the stomach to which it is loosely attached by a gastrosplenic ligament that is sufficiently generous to make splenic torsion a relatively frequent mishap. Its parietal surface is in contact with the diaphragm. Its visceral surface is divided into two narrow strips by a long hilus: the cranial strip is related to the stomach, the caudal one to the intestines. The dorsal extremity extends into the space between the stomach, left kidney, and pancreas, but it is usually prevented from making direct contact with these organs by the interposition of fat. The ventral extremity may emerge below the left costal arch and, exceptionally, may even cross the abdomen to the right side; although its position is determined by the degree of fullness of the stomach, it never wholly leaves the protection of the ribs. Its sectioned surface is patterned by the presence of very prominent splenic corpuscles.

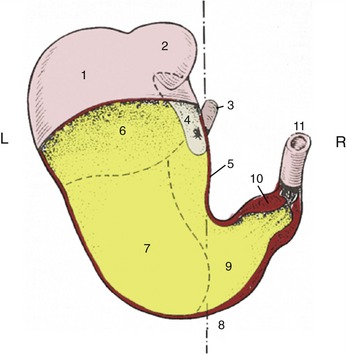

Figure 34–4 Stomach partially opened, caudoventral view, semischematic. 1, Fundus; 2, diverticulum; 3, esophagus; 4, nonglandular mucosa; 5, lesser curvature; 6, cardiac gland region; 7, region of proper gastric glands; 8, approximate position of median plane; 9, pyloric gland region; 10, torus pyloricus; 11, duodenum.

THE STOMACH

The stomach is of the simple type, presenting fundus, corpus, and a pyloric part (Figure 34–4/2). The first two are generally confined to the left side of the abdomen but may extend across the median plane when the stomach is grossly distended. They are cranially related to the liver and diaphragm. The pyloric part extends to the right and is also in contact with the liver. All parts are related caudally to various parts of the intestinal mass; the principal relation is to the ascending colic spiral. It is only when grossly distended that the stomach makes contact with the abdominal floor and, on the left, extends beyond the protection of the rib cage. A feature unique to the pig among domestic species is the presence of a conical diverticulum (Figure 34–5/2) projecting caudally from the fundus.

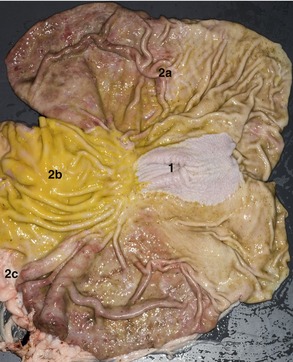

The interior displays a narrow nonglandular strip of mucosa that extends into the diverticulum and follows the lesser curvature for some distance below the cardia (Figure 34–5/1). The remainder of the mucosa is divided into the usual three glandular regions, which are more clearly distinguished by color than in most species, although their borders are not always sharply defined (Figure 34–5/2a, 2b, 2c). A second feature of distinction is the very prominent torus narrowing the pyloric canal at the exit into the duodenum (Figure 34–4/10).

Figure 34–5 The stomach laid open (cardia to the right). 1, Nonglandular region; 2a, region with cardiac glands; 2b, region with proper gastric glands; 2c, region with pyloric glands.

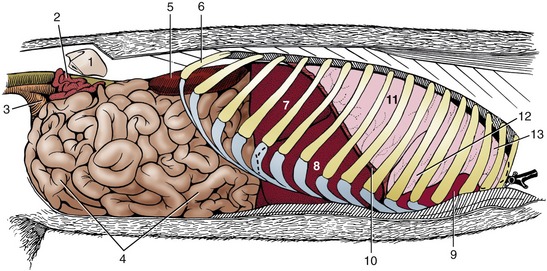

Although the omenta are arranged much as in the dog, the greater one is less extravagantly developed, does not intervene between the intestines and the abdominal floor, and is therefore not encountered when the abdomen is first opened (Figure 33–4/5).

THE SMALL INTESTINE

The duodenum is also arranged rather like that of the dog, descending toward the pelvis before turning to run forward to the left of the root of the mesentery before dipping ventrally to be continued by the jejunum (Figure 34–7/1,2,3). It is entered by the bile duct about 3 cm beyond the pylorus and by the single (accessory) pancreatic duct about 10 cm farther on. Both openings are raised on papillae.

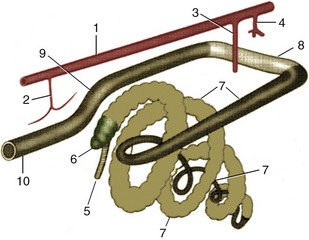

Figure 34–7 The development of the ascending colon, left lateral view. 1, Descending duodenum; 2, caudal flexure of duodenum; 3, jejunum; 4, ileum; 5, cecum; 6, ascending colon; 7, transverse colon; 8, descending colon; 9, descending mesocolon; 10, mesoduodenum; 11, mesentery.

The jejunum is arranged in many small loops (Figure 34–9/4) suspended by a mesentery that gives them much freedom of position (Figure 34–7/11). The greater part lies in the right half of the abdomen, ventrally and toward the pelvis, but some part may be in contact with the left flank behind the colic spiral. Like many other abdominal organs, the jejunum must accommodate its position to the condition of the stomach and, in sows, to that of the uterus.

Figure 34–9 Abdominal and thoracic viscera, right lateral view. 1, Wing of ilium; 2, uterine horns; 3, bladder; 4, jejunum; 5, right kidney; 6, last rib; 7, 8, right lateral and medial lobes of liver; 9, heart in pericardium; 10, diaphragm, cut; 11-13, caudal, middle, and cranial lobes of right lung.

THE LARGE INTESTINE

The large intestine is capacious and, like that of the horse, is much sacculated, being drawn into a series of pouches by two (on the colon) or three (on the cecum) teniae that run along its length. The peculiar disposition presented by the cecum and ascending colon in this animal, unique among domestic species, results from the greater than 360° rotation performed by the loop of bowel that it is herniated into the umbilical cord early in development (Figures 3–64 and 3–65). This carries the caudal limb of the loop, including the cecocolic junction, to the left of the mesenteric axis, where it remains throughout later development and into adult life. The ascending colon thus commences on the left side and only gains its usual continuation into the transverse colon on the right side of the abdomen in consequence of the reversal of course described below.

The cecum and colon must be considered together as they combine in a conical, ventrally tapering mass suspended from the roof of the abdomen (Figure 34–6). The cecum, which has a capacity of about 2 L, has its origin below the left kidney and extends ventrally or caudoventrally against the left flank to its rounded, blind apex. The ascending colon is arranged around its mesentery in a cone that points ventrally to reach the abdominal floor (with some deviation possible in any direction) (Figure 34–7). The outer part of the cone is provided by the wide, sacculated portion continuing from the cecum; when viewed from above, it spirals ventrally, clockwise and centripetally, before reversing course at the apex of the cone to ascend in narrower, smoother, and tighter centrifugal coils concealed within the center of the cone. These carry it dorsally to emerge from the base of the cone, pass to the right of the root of the mesentery, and continue as the transverse colon. The cecocolic mass mainly occupies the middle third of the left side of the abdomen, leaving the caudal and right regions available to the jejunum. However, variation is common and, especially where the jejunum is concerned, can be considerable. There is little notable about the remainder of the large intestine beyond the existence of a rectal ampulla.

THE LIVER

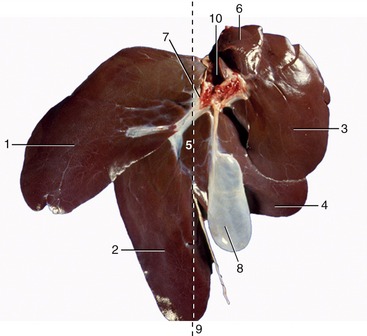

The liver resembles that of the dog in position and lobation. It is divided by deep fissures into left lateral and medial lobes and right medial and lateral major lobes, supplemented by a smaller quadrate lobe and caudate process (Figure 34–8).

Figure 34–8 Visceral surface of the liver. 1, Left lateral lobe; 2, left medial lobe; 3, right lateral lobe; 4, right medial lobe; 5, quadrate lobe; 6, caudate process; 7, porta; 8, gallbladder; 9, approximate position of median plane; 10, caudal vena cava.

The gallbladder is situated between the quadrate and right medial lobes. Apart from its ventral margin, the liver lies under the protection of the ribs (Figure 33–4/3); the somewhat larger part is situated to the right of the median plane (Figure 34–8; see also Figure 3–53, B). The cranial surface is shaped to the diaphragm, and the caudal surface is indented by the stomach and duodenum; other contacts with the pancreas, jejunum, and colon leave less distinct or no impressions.

The two most notable features of the liver of this species are the lack of contact with (and molding by) the right kidney and the very well-developed fibrous tissue framework that prominently outlines the hepatic lobules on the surface and in section (Figure 3–52, A-B). The latter feature is relevant to the clinician because surgery is required if a biopsy is indicated (aspiration is impossible with so fibrous a tissue) and is also relevant to the producer because it limits the price the consumer can be charged for a not very palatable foodstuff.

THE PANCREAS

The pancreas is related to the abdominal roof, largely on the left side. It is related ventrally to the gastric fundus, the spleen, and the left kidney (through fat) and, on the right, follows the duodenum. Other contacts are with the liver and right kidney. As happens in most mammals, it is penetrated by the portal vein traveling to the liver.

THE KIDNEYS

The shape of the pig’s kidneys is very distinctive. They are flattened (see Figure 5–21, C) against the abdominal roof (within a fatty capsule), extending between the level of the last rib to that of the fourth lumbar vertebra (Figure 34–9/5). This symmetry of position is most unusual and deprives the right kidney of the expected contact with the liver. The left kidney is related ventrally to the colic spiral, the cecum, and the pancreas; the right one is related to the descending duodenum and also possibly to the pancreas.

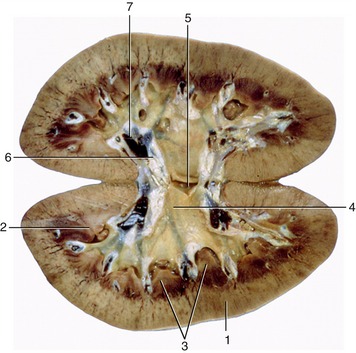

The internal structure resembles that of the human kidney (Figure 34–10). A central cavity with two recesses (major calices) directed toward the poles comprise the pelvis, which extends about a dozen minor calices, each embracing a renal papilla through which the papillary ducts discharge urine. The papillae correspond to renal pyramids, and because the number of these is reduced by fusions in the course of development, there is some inequality in the size of the units presented by the mature organ.

THE LYMPHATIC STRUCTURES OF THE ABDOMEN

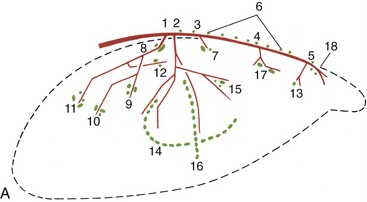

The numerous abdominal lymph nodes fall into three groups: those of the abdominal roof, those associated with the mesogastric viscera (supplied by the celiac artery), and those associated with the viscera supplied by the two mesenteric arteries (Figure 34–11).

Figure 34–11 A, Schema of the major abdominal arteries and lymph nodes. 1, Celiac artery; 2, cranial mesenteric artery; 3, renal artery; 4, caudal mesenteric artery; 5, deep circumflex iliac artery; 6, lumbar aortic nodes; 7, renal nodes; 8, celiac nodes; 9, splenic nodes; 10, gastric nodes; 11, hepatic nodes; 12, pancreaticoduodenal nodes; 13, lateral iliac nodes; 14, jejunal nodes; 15, ileocolic nodes; 16, colic nodes; 17, caudal mesenteric nodes; 18, medial iliac nodes. B, Part of the jejunum, showing the inclusion of jejunal lymph nodes in the mesentery.

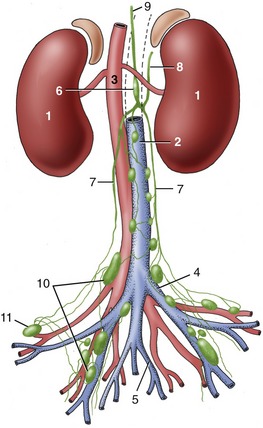

The first group includes aortic, renal, and iliac nodes whose disposition is illustrated (Figure 34–12). The iliac assemblage receives lymph from structures of the hindlimb and pelvis and from part of the belly wall, including most mammary glands. Most nodes of this group drain lymph from structures of the back and forward it to the lumbar trunks or directly into the cisterna chyli.

Figure 34–12 The lymph nodes of the sublumbar area, ventral view. 1, Kidneys; 2, aorta; 3, caudal vena cava; 4, external iliac artery; 5, internal iliac artery; 6, cisterna chyli; 7, lumbar trunks and lumbar aortic nodes; 8, intestinal trunk; 9, thoracic duct; 10, medial iliac nodes; 11, lateral iliac node.

The nodes associated with the mesogastric viscera are mainly located close to where the arteries enter the individual organs; others, directly related to the celiac artery, provide an additional station on the drainage route, which ultimately joins the cisterna chyli. The celiac nodes also receive some lymph from caudal thoracic structures, including the caudal lobes of the lungs.

The group that drains lymph from the small and large intestines includes a long chain in the mesentery of the jejunum, placed midway between its root and the gut, and a second set within the mesentery of the ascending colon; others are more randomly placed in relation to the remainder of the large intestine. All drain to the cisterna via an intestinal trunk. The nodes associated with the jejunum are of particular importance in meat inspection (Figure 34–11, B).