CHAPTER 13 Clinical Manifestations of Nasal Disease

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

The nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses have a complex anatomy and are lined by mucosa. Their rostral portion is inhabited by bacteria in health. Nasal disorders are frequently associated with mucosal edema, inflammation, and secondary bacterial infection. They are often focal or multifocal in distribution. These factors combine to make the accurate diagnosis of nasal disease a challenge that can be met only through a thorough, systematic approach.

Diseases of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses typically cause nasal discharge; sneezing; stertor (i.e., snoring or snorting sounds); facial deformity; systemic signs of illness (e.g., lethargy, inappetence, weight loss); or, in rare instances, central nervous system signs. The most common clinical manifestation is nasal discharge. The general diagnostic approach to animals with nasal disease is included in the discussion of nasal discharge. Specific considerations related to sneezing, stertor, and facial deformity follow. Stenotic nares are discussed in the section on brachycephalic airway syndrome (Chapter 18).

NASAL DISCHARGE

Classification and Etiology

Nasal discharge is most commonly associated with disease localized within the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, although it may also develop with disorders of the lower respiratory tract, such as bacterial pneumonia and infectious tracheobronchitis, or systemic disorders, such as coagulopathies and systemic hypertension. Nasal discharge is characterized as serous, mucopurulent with or without hemorrhage, or purely hemorrhagic (epistaxis). Serous nasal discharge has a clear, watery consistency. Depending on the quantity and duration of the discharge, a serous discharge may be normal, may be indicative of viral upper respiratory infection, or may precede the development of a mucopurulent discharge. As such, many of the causes of mucopurulent discharge can initially cause serous discharge (Box 13-1).

BOX 13-1 Differential Diagnoses for Nasal Discharge in Dogs and Cats

BOX 13-1 Differential Diagnoses for Nasal Discharge in Dogs and Cats

Mucopurulent nasal discharge is typically characterized by a thick, ropey consistency and has a white, yellow, or green tint. A mucopurulent nasal discharge implies inflammation. Most intranasal diseases result in inflammation and secondary bacterial infection, making this sign a common presentation for most nasal diseases. Potential etiologies include infectious agents, foreign bodies, neoplasia, polyps, and extension of disease from the oral cavity (see Box 13-1). If mucopurulent discharge is present in conjunction with signs of lower respiratory tract disease, such as cough, respiratory distress, or auscultable crackles, the diagnostic emphasis is initially on evaluation of the lower airways and pulmonary parenchyma. Hemorrhage may be associated with mucopurulent exudate from any etiology, but significant and prolonged bleeding in association with mucopurulent discharge is usually associated with neoplasia or mycotic infections.

Persistent pure hemorrhage (epistaxis) can result from trauma, local aggressive disease processes (e.g., neoplasia, mycotic infections), systemic hypertension, or systemic bleeding disorders. Systemic hemostatic disorders that can cause epistaxis include thrombocytopenia, thrombocytopathies, von Willebrand’s disease, rodenticide toxicity, and vasculitides. Ehrlichiosis and Rocky Mountain spotted fever can cause epistaxis through several of these mechanisms. Nasal foreign bodies may cause hemorrhage after entry into the nasal cavity, but the bleeding tends to subside quickly. Bleeding can also occur after aggressive sneezing from any cause.

Diagnostic Approach

A complete history and physical examination can be used to prioritize the differential diagnoses for each type of nasal discharge (see Box 13-1). Acute and chronic diseases are defined by obtaining historical information regarding the onset of signs and evaluating the overall condition of the animal. Acute processes, such as foreign bodies or acute feline viral infections, often result in a sudden onset of signs, including sneezing, and the animal’s body condition is excellent. In chronic processes, such as mycotic infections or neoplasia, signs are present over a long period of time and the overall body condition can be deleteriously affected. A history of gagging or retching may indicate masses, foreign bodies, or exudate in the caudal nasopharynx.

Nasal discharge is characterized as unilateral or bilateral on the basis of both historical and physical examination findings. When nasal discharge is apparently unilateral, a cold microscope slide may be held close to the external nares to determine the patency of the side of the nasal cavity without discharge. Condensation will not be visible in front of the naris if airflow is obstructed, which suggests that the disease is actually bilateral. Although any bilateral process can cause signs from one side only and unilateral disease can progress to involve the opposite side, some generalizations can be made. Systemic disorders and infectious diseases tend to involve both sides of the nasal cavity, whereas foreign bodies, polyps, and tooth root abscessation tend to cause unilateral discharge. Neoplasia may initially cause unilateral discharge that later becomes bilateral after destruction of the nasal septum.

Ulceration of the nasal plane is highly suggestive of a diagnosis of nasal aspergillosis (Fig. 13-1). Polypoid masses protruding from the external nares in the dog are typical of rhinosporidiosis, and in the cat they are typical of cryptococcosis.

FIG 13-1 Depigmentation and ulceration of the planum nasale is suggestive of nasal aspergillosis. The visible lesions usually extend from one or both nares and are most severe ventrally. This dog has unilateral depigmentation and mild ulceration.

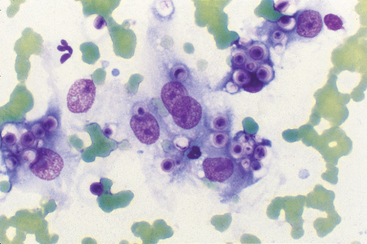

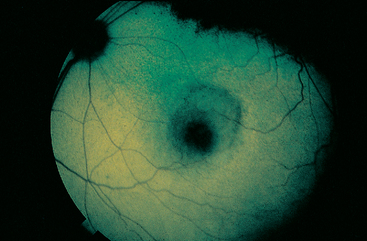

A thorough assessment of the head, including facial symmetry, teeth, gingiva, hard and soft palate, mandibular lymph nodes, and eyes, should be performed. Mass lesions invading beyond the nasal cavity can cause deformity of facial bones or the hard palate, exophthalmos, or inability to retropulse the eye. Pain on palpation of the nasal bones is suggestive of aspergillosis. Gingivitis, dental calculi, loose teeth, or pus in the gingival sulcus should raise an index of suspicion for oronasal fistulae or tooth root abscess, especially if unilateral nasal discharge is present. Foci of inflammation and folds of hyperplastic gingiva in the dorsum of the mouth should be probed for oronasal fistulae. A normal examination of the oral cavity does not rule out oronasal fistulae or tooth root abscess. The hard and soft palates are examined for deformation, erosions, or congenital defects such as clefts or hypoplasia. Mandibular lymph node enlargement suggests active inflammation or neoplasia, and fine-needle aspirates of enlarged or firm nodes are evaluated for organisms, such as Cryptococcus, and neoplastic cells (Fig. 13-2). A fundic examination should always be performed because active chorioretinitis can occur with cryptococcosis, ehrlichiosis, and malignant lymphoma (Fig. 13-3). Retinal detachment can occur with systemic hypertension or mass lesions extending into the bony orbit. With epistaxis, identification of petechiae or hemorrhage in other mucous membranes, skin, ocular fundus, feces, or urine supports a systemic bleeding disorder. Note that melena may be present as a result of swallowing blood from the nasal cavity.

FIG 13-2 Photomicrograph of fine-needle aspirate of a cat with facial deformity. Identification of cryptococcal organisms provides a definitive diagnosis for cats with nasal discharge or facial deformity. Organisms can often be found in swabs of nasal discharge, fine-needle aspirates of facial masses, or fine-needle aspirates of enlarged mandibular lymph nodes. The organisms are variably sized, ranging from about 3 to 30μm in diameter, with a wide capsule and narrow-based budding. They may be found intracellularly or extracellularly.

FIG 13-3 Fundic examination can provide useful information in animals with signs of respiratory tract disease. This fundus from a cat with chorioretinitis caused by cryptococcosis has a large, focal, hyporeflective lesion in the area centralis. Smaller regions of hyporeflectivity were also seen. The optic disk is in the upper left-hand corner of the photograph.

(Courtesy M. Davidson, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, N.C.)

Diagnostic tests that should be considered for a dog or cat with nasal discharge are included in Box 13-2. The signalment, history, and physical examination findings dictate in part which diagnostic tests are ultimately required to establish the diagnosis. As a general rule, less invasive diagnostic tests are performed initially. A complete blood count (CBC) with platelet count, coagulation panel (i.e., activated clotting time or prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times), buccal mucosal bleeding time, and arterial blood pressure should be evaluated in dogs and cats with epistaxis. Von Willebrand’s factor assays are performed in purebred dogs with epistaxis and in dogs with prolonged mucosal bleeding times. Determination of Ehrlichia spp. and Rocky Mountain spotted fever titers are indicated for dogs with epistaxis in regions of the country where potential exposure to these rickettsial agents exists. Testing for Bartonella sp. is also considered. Testing for feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and feline leukemia virus (FeLV) should be performed in cats with chronic nasal discharge and potential exposure. Cats infected with FeLV may be predisposed to chronic infection with herpesvirus or calicivirus, whereas those with FIV may have chronic nasal discharge without concurrent infection with these upper respiratory viruses.

Most animals with intranasal disease have normal thoracic radiographs. However, thoracic radiographs may be useful in identifying primary bronchopulmonary disease, pulmonary involvement with cryptococcosis, and rare metastases from neoplastic disease. They may also be a useful preanesthetic screening test for animals that will require nasal imaging, rhinoscopy, and nasal biopsy.

Cytologic evaluation of superficial nasal swabs may identify cryptococcal organisms in cats (see Fig. 13-2). Nonspecific findings include proteinaceous background, moderate to severe inflammation, and bacteria. Tests to identify herpesvirus and calicivirus infections may be performed in cats with acute and chronic rhinitis. These tests are most useful in evaluating cattery problems rather than the condition of an individual cat (see Chapter 15).

Fungal titer determinations are available for aspergillosis in dogs and cryptococcosis in dogs and cats. The test for aspergillosis detects antibodies in the blood. A single positive test result strongly suggests active infection by the organism; however, a negative titer does not rule out the disease. In either case, the result of the test must be interpreted in conjunction with results of nasal imaging, rhinoscopy, and nasal histology and culture.

The blood test of choice for cryptococcosis is the latex agglutination capsular antigen test (LCAT). Because organism identification is usually possible in specimens from infected organs, organism identification is the method of choice for a definitive diagnosis. The LCAT is performed if cryptococcosis is suspected but an extensive search for the organism has failed. The LCAT is also performed in animals with a confirmed diagnosis as a means of monitoring therapeutic response (see Chapter 98).

In general, nasal radiography or computerized tomography (CT), rhinoscopy, and biopsy are required to establish a diagnosis of intranasal disease in most dogs and in cats in which acute viral infection is not suspected. These diagnostic tests are performed with the dog or cat under general anesthesia. Nasal radiographs or CT scans are obtained first, followed by oral examination and rhinoscopy and then specimen collection. This order is recommended because the results of radiography or CT and rhinoscopy are often useful in the selection of biopsy sites. In addition, hemorrhage from biopsy sites could obscure or alter radiographic and rhinoscopic detail if the specimen were collected first. In dogs and cats suspected of having acute foreign body inhalation, rhinoscopy is performed first in the hopes of identifying and removing the foreign material. (See Chapter 14 for more detail on nasal radiography, CT, and rhinoscopy.)

The combination of radiography, rhinoscopy, and nasal biopsy has a diagnostic success rate of approximately 80% in dogs. Dogs with persistent signs in which a diagnosis cannot be obtained following the assessment described earlier require further evaluation. It is more difficult to evaluate the success rate for cats. High proportions of cats with chronic nasal discharge suffer from feline chronic rhinosinusitis (idiopathic rhinitis) and are diagnosed only through exclusion. Cats are evaluated further only if signs suggestive of another disease are found during any part of their evaluation or if the clinical signs are progressive or intolerable to the owners.

Nasal CT is considered if not performed previously and if a diagnosis has not been made. CT provides excellent visualization of all of the nasal turbinates and may allow the identification of small masses that are not visible on nasal radiography or rhinoscopy. CT is also more accurate than nasal radiography in determining the extent of nasal tumors. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be more accurate than CT in the assessment of soft tissues, such as nasal neoplasia. In the absence of a diagnosis, nasal imaging (preferably CT or MRI), rhinoscopy, and biopsy can be repeated after a 1- to 2-month delay.

Exploratory rhinotomy with turbinectomy is the final diagnostic test. Surgical exploration of the nose allows direct visualization of the nasal cavity for the presence of foreign bodies, mass lesions, or fungal mats and for obtaining biopsies and culture specimens. The potential benefits of surgery, however, should be weighed against the potential complications associated with rhinotomy and turbinectomy. The Suggested Readings section offers surgical references.

SNEEZING

Etiology and Diagnostic Approach

A sneeze is an explosive release of air from the lungs through the nasal cavity and mouth. It is a protective reflex to expel irritants from the nasal cavity. Intermittent, occasional sneezing is considered normal. Persistent, paroxysmal sneezing should be considered abnormal. Disorders commonly associated with acute-onset, persistent sneezing include nasal foreign body and feline upper respiratory infection. The canine nasal mite, Pneumonyssoides caninum, and exposure to irritating aerosols are less common causes of sneezing. All the nasal diseases considered as differential diagnoses for nasal discharge are also potential causes for sneezing; however, animals with these diseases generally present with nasal discharge as the primary complaint.

The owners should be questioned carefully concerning the possible recent exposure of the pet to foreign bodies (e.g., rooting in the ground, running through grassy fields), powders, and aerosols or, in cats, exposure to new cats or kittens. Sneezing is an acute phenomenon that often subsides with time. A foreign body should not be excluded from the differential diagnoses just because the sneezing subsides. In the dog a history of acute sneezing followed by the development of a nasal discharge is suggestive of a foreign body.

Other findings may help narrow the list of differential diagnoses. Dogs with foreign bodies may paw at their nose. Foreign bodies are typically associated with unilateral, mucopurulent nasal discharge, although serous or serosanguineous discharge may be present initially. Foreign bodies in the caudal nasopharynx may cause gagging, retching, or reverse sneezing. The nasal discharge associated with reactions to aerosols, powders, or other inhaled irritants is usually bilateral and serous in nature. In cats other clinical signs supportive of a diagnosis of upper respiratory infection, such as conjunctivitis and fever, may be present as well as a history of exposure to other cats or kittens.

Dogs in which acute, paroxysmal sneezing develops should undergo prompt rhinoscopic examination (see Chapter 14). With time, foreign material may become covered with mucus or migrate deeper into the nasal passages, and any delay in performing rhinoscopy may interfere with the identification and removal of the foreign bodies. Nasal mites are also identified rhinoscopically. In contrast, cats sneeze more often as a result of acute viral infection rather than a foreign body. Immediate rhinoscopic examination is not indicated unless there has been known exposure to a foreign body or the history and physical examination findings do not support a diagnosis of viral upper respiratory infection.

REVERSE SNEEZING

Reverse sneezing is a paroxysm of noisy, labored inspiration initiated by nasopharyngeal irritation. Such irritation can be the result of a foreign body located dorsal to the soft palate or nasopharyngeal inflammation. Foreign bodies usually originate from grass or plant material that is prehended into the oral cavity and which, presumably, is coughed up or migrates into the nasopharyx. Epiglottic entrapment of the soft palate has also been proposed as a cause. The majority of cases are idiopathic. Small-breed dogs are usually affected, and signs may be associated with excitement or drinking. The paroxysms last only a few seconds and do not significantly interfere with respiration. Although these animals usually display this sign throughout their life, the problem rarely progresses.

The diagnosis is generally made by a thorough history and physical examination. Generally, no treatment is needed because the episodes are self-limiting. Some owners report that massaging the neck shortens an ongoing episode or that administration of antihistamines decreases the frequency and severity of episodes, but controlled studies are lacking. Further evaluation for potential nasal or pharyngeal disorders is indicated if syncope, exercise intolerance, or other signs of respiratory disease are reported or if the reverse sneezing is severe or progressive.

STERTOR

Stertor refers to coarse, audible snoring or snorting sounds associated with breathing. It indicates upper airway obstruction. Stertor is most often the result of pharyngeal disease (see Chapter 16). Intranasal causes of stertor include obstruction caused by congenital deformities, masses, exudate, or blood clots. Evaluation for nasal disease proceeds as described for nasal discharge.

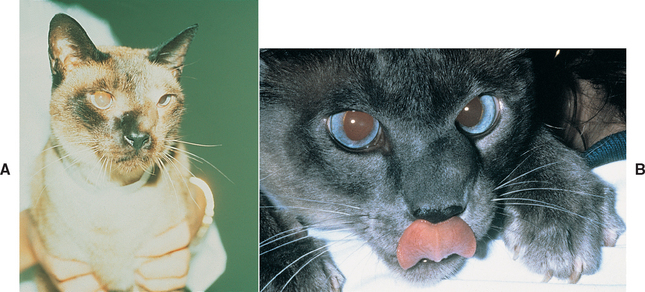

FACIAL DEFORMITY

Carnaissal tooth root abscess in dogs can result in swelling, often with drainage, adjacent to the nasal cavity and beneath the eye. Excluding dental disease, the most common causes of facial deformity adjacent to the nasal cavity are neoplasia and, in cats, cryptococcosis (Fig. 13-4). Visible swellings can often be evaluated directly through fine-needle aspiration or punch biopsy (see Fig. 13-2). Further evaluation proceeds as for nasal discharge if such an approach is not possible or is unsuccessful.

FIG 13-4 Facial deformity characterized by firm swelling over the maxilla in two cats. A, Deformity in this cat was the result of carcinoma. Notice the ipsilateral blepharospasm. B, Deformity in this cat was the result of cryptococcosis. A photomicrograph of the fine-needle aspirate of this swelling is provided in Fig. 13-2.

Demko JL, et al. Chronic nasal discharge in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;230:1032.

Fossum TW. Small animal surgery, ed 3. St Louis: Mosby, 2007.

Henderson SM. Investigation of nasal disease in the cat: a retrospective study of 77 cases. J Fel Med Surg. 2004;6:245.

Lent SE, et al. Evaluation of rhinoscopy and rhinoscopy-assisted mucosal biopsy in diagnosis of nasal disease in dogs: 119 cases (1985–1989). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992;201:1425.

Pomrantz JS, et al. Comparison of serologic evaluation via agar gel immunodiffusion and fungal culture of tissue for diagnosis of nasal aspergillosis in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;203:1319.

Slatter D. Textbook of small animal surgery, ed 3. St Louis: WB Saunders, 2003.

Strasser JL, et al. Clinical features of epistaxis in dogs: a retrospective study of 35 cases (1999-2002). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2005;41:179.

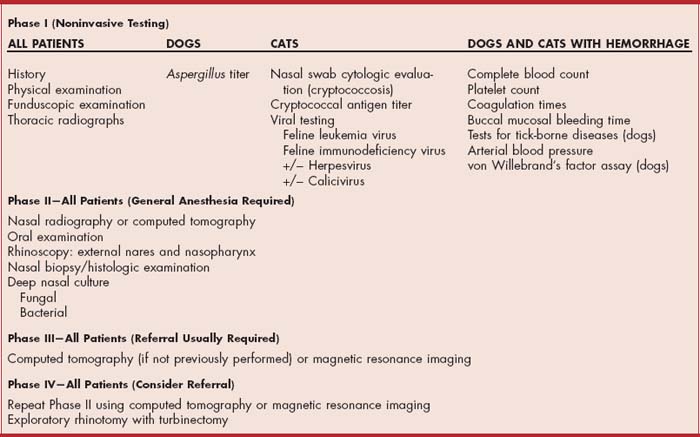

BOX 13-2

BOX 13-2