CHAPTER 18 Disorders of the Larynx and Pharynx

LARYNGEAL PARALYSIS

Laryngeal paralysis refers to a failure of the arytenoid cartilages to abduct during inspiration, creating extrathoracic (upper) airway obstruction. The abductor muscles are innervated by the left and right recurrent laryngeal nerves. If clinical signs develop, both arytenoid cartilages are usually affected.

Etiology

Potential causes of laryngeal paralysis are listed in Box 18-1. Laryngeal paralysis is most often idiopathic. Trauma or neoplasia involving the ventral neck can damage the recurrent laryngeal nerves directly or through inflammation and scarring. Masses or trauma involving the anterior thoracic cavity can also cause damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerves as they course around the subclavian artery (right side) or ligamentum arteriosum (left side). Dogs with polyneuropathy-polymyopathy can be presented with laryngeal paralysis as the predominant clinical sign. Polyneuropathies in turn have been associated with immune-mediated diseases, endocrinopathies, or other systemic disorders (see Chapter 71). Congenital laryngeal paralysis has been documented in the Bouvier des Flandres and is suspected in Siberian Huskies and Bull Terriers. A laryngeal paralysis-polyneuropathy complex has been described in young Dalmations, Rottweilers, and Great Pyrenees. Anecdotally, there may be an increasing incidence of idiopathic laryngeal paralysis in older Golden and Labrador Retrievers, and in one study 47 of 140 dogs (34%) with laryngeal paralysis were Labrador Retrievers (MacPhail et al., 2001). Laryngeal paralysis is uncommon in cats.

Clinical Features

Laryngeal paralysis can occur at any age and in any breed, although the idiopathic form is most commonly seen in older large-breed dogs. Clinical signs of respiratory distress and stridor are a direct result of narrowing of the airway at the arytenoid cartilages and vocal folds. The owner may also note a change in voice (i.e., bark or meow). Most patients are presented for acute respiratory distress, in spite of the chronic, progressive nature of this disease. Decompensation is frequently a result of exercise, excitement, or high environmental temperatures, resulting in a cycle of increased respi ratory efforts; increased negative airway pressures, which suck the soft tissue into the airway; and pharyngeal edema and inflammation, which lead to further increased respiratory efforts. Cyanosis, syncope, and death can occur. Dogs with respiratory distress require immediate emergency therapy.

Some dogs with laryngeal paralysis exhibit gagging or coughing with eating or have overt aspiration pneumonia, presumably resulting from concurrent pharyngeal dysfunction or a more generalized polyneuropathy-polymyopathy.

Diagnosis

A definitive diagnosis of laryngeal paralysis is made through laryngoscopy (see p. 239). Movement of the arytenoid cartilages is observed during a light plane of anesthesia while the patient is taking deep breaths. In laryngeal paralysis the arytenoid cartilages and vocal folds remain closed during inspiration and open slightly during expiration. The larynx does not exhibit the normal coordinated movement associated with breathing, opening on inspiration and closing on expiration. Additional laryngoscopic findings may include pharyngeal edema and inflammation. The larynx and pharynx are also examined for neoplasia, foreign bodies, or other diseases that might interfere with normal function and for laryngeal collapse (see p. 241).

Once a diagnosis of laryngeal paralysis is established, additional diagnostic tests should be considered to identify underlying or associated diseases, to rule out concurrent pulmonary problems (e.g., aspiration pneumonia) that may be contributing to the clinical signs, and to rule out concurrent pharyngeal and esophageal motility problems (Box 18-2). The latter is especially important if surgical correction for the treatment of laryngeal paralysis is being considered. If the diagnostic tests fail to identify a cause, idiopathic laryngeal paralysis is diagnosed.

Treatment

In animals with respiratory distress, emergency medical therapy to relieve upper airway obstruction is indicated (see Chapter 26). Following stabilization and a thorough diagnostic evaluation, surgery is usually the treatment of choice. Even when specific therapy can be directed at an associated disease (e.g., hypothyroidism), complete resolution of clinical signs of laryngeal paralysis is rarely seen. Also, most cases are idiopathic, and signs are generally progressive.

Various laryngoplasty techniques have been described, including arytenoid lateralization (tie-back) procedures, partial laryngectomy, and castellated laryngoplasty. The goal of surgery is to provide an adequate opening for the flow of air but not one so large that the animal is predisposed to aspiration and the development of pneumonia. Several operations to gradually enlarge the glottis may be necessary to minimize the chance of subsequent aspiration. The recommended initial procedure for most dogs and cats is unilateral arytenoid lateralization.

If surgery is not an option, medical management consisting of antiinflammatory doses of short-acting glucocorticoids (e.g., prednisone, 0.5 mg/kg given orally q12h initially) and cage rest may reduce secondary inflammation and edema of the pharynx and larynx and enhance airflow.

Prognosis

The overall prognosis for dogs with laryngeal paralysis treated surgically is fair to good. As many as 90% of owners of dogs with laryngeal paralysis that underwent unilateral arytenoid lateralization consider the procedure successful 1 year or longer after surgery (White, 1989; Hammel et al., 2006). MacPhail et al. (2001) reported a median survival time of 1800 days (nearly 5 years) for 140 dogs that underwent various surgical procedures, although the mortality rate from postoperative complications was high at 14%. The most common complication is aspiration pneumonia. A guarded prognosis is warranted for patients with signs of aspiration, dysphagia, megaesophagus, or systemic polyneuropathy or polymyopathy. Dogs with laryngeal paralysis as an early manifestation of generalized polyneuropathy or polymyopathy may have progression of signs.

BRACHYCEPHALIC AIRWAY SYNDROME

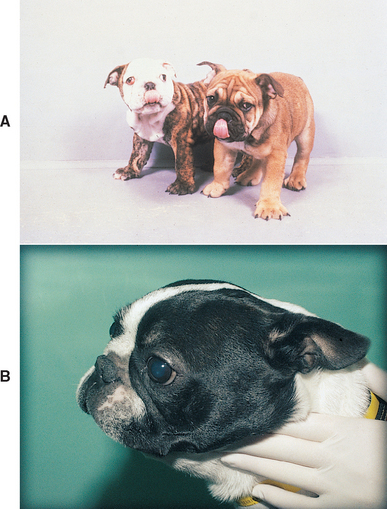

The term brachycephalic airway syndrome, or upper airway obstruction syndrome, refers to the multiple anatomic abnor malities commonly found in brachycephalic dogs and, to a lesser extent, in short-faced cats such as Himalayans. The predominant anatomic abnormalities include stenotic nares, elongated soft palate, and, in Bulldogs, hypoplastic trachea. Prolonged upper airway obstruction resulting in increased inspiratory efforts may lead to eversion of the laryngeal saccules and, ultimately, laryngeal collapse. The severity of these abnormalities varies, and one or any combination of these abnormalities may be present in any given brachycephalic dog or short-faced cat (Fig. 18-1).

FIG 18-1 Two Bulldog puppies (A) and a Boston Terrier (B) with brachycephalic airway syndrome. Abnormalities can include stenotic nares, elongated soft palate, everted laryngeal saccules, laryngeal collapse, and hypoplastic trachea.

Concurrent gastrointestinal signs such as ptyalism, regurgitation, and vomiting are common in dogs with brachycephalic airway syndrome (Poncet et al., 2005) Underlying gastrointestinal disease may be a concurrent problem in these breeds of dogs or may result from or be exacerbated by the increased intrathoracic pressures generated in response to the upper airway obstruction.

Clinical Features

The abnormalities associated with the brachycephalic airway syndrome impair the flow of air through the extrathoracic (upper) airways and cause clinical signs of upper airway obstruction, including loud breathing sounds, stertor, increased inspiratory efforts, cyanosis, and syncope. Clinical signs are exacerbated by exercise, excitement, and high environmental temperatures. The increased inspiratory effort commonly associated with this syndrome may cause secondary edema and inflammation of the laryngeal and pharyngeal mucosae and enhance eversion of the laryngeal saccules or laryngeal collapse, further narrowing the glottis, exacerbating the clinical signs, and creating a vicious cycle. As a result, some dogs may be presented with life-threatening upper airway obstruction that requires immediate emergency therapy. Concurrent gastrointestinal signs are commonly reported.

Diagnosis

A tentative diagnosis is made on the basis of the breed, clinical signs, and the appearance of the external nares (Fig. 18-2). Stenotic nares are generally bilaterally symmetric, and the alar folds may be sucked inward during inspiration, thereby worsening the obstruction to airflow. Laryngoscopy (see Chapter 17) and radiographic evaluation of the trachea (see Chapter 20) are necessary to fully assess the extent and severity of abnormalities. Most other causes of upper airway obstruction (see Chapter 26, and Boxes 16-1 and 16-2) can also be ruled in or out on the basis of the results of these diagnostic tests.

Treatment

Therapy should be designed to enhance the passage of air through the upper airways and to minimize the factors that exacerbate the clinical signs (e.g., excessive exercise and excitement, overheating). Surgical correction of the anatomic defects is the treatment of choice. The specific surgical procedure selected depends on the nature of the existing problems and can include widening of the external nares and removal of excessive soft palate and everted laryngeal saccules.

Correction of stenotic nares is a simple procedure and can lead to a surprising alleviation of the signs in affected patients. Stenotic nares can be safely corrected at 3 to 4 months of age, ideally before clinical signs develop. The soft palate should be evaluated at the same time and also corrected if elongated. Such early relief of obstruction should decrease the amount of negative pressure placed on the pharyngeal and laryngeal structures during inspiration and decrease progression of disease.

Medical management consisting of the administration of short-acting glucocorticoids (e.g., prednisone, 0.5 mg/kg given orally q12h initially) and cage rest may reduce the secondary inflammation and edema of the pharynx and larynx and enhance airflow, but it will not eliminate the problem. Emergency therapy may be required to alleviate the upper airway obstruction in animals presenting in respiratory distress (see Chapter 26).

Weight management and concurrent treatment for gastrointestinal disease should not be neglected in patients with brachycephalic airway syndrome.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the severity of the abnormalities at the time of diagnosis and the ability to surgically correct them. The clinical signs will progressively worsen if the underlying problems go uncorrected. The prognosis after early surgical correction of the abnormalities is good for many animals. Laryngeal collapse (see p. 241) is generally considered a poor prognostic indicator, although a recent study demonstrated that even dogs with severe laryngeal collapse can respond well to surgical intervention (Torrez et al., 2006). Permanent tracheostomy can be considered as a salvage procedure in animals with severe collapse that are not responsive. A hypoplastic trachea is not surgically correctable, but there is no clear relationship between the degree of hypoplasia and morbidity or mortality.

OBSTRUCTIVE LARYNGITIS

Nonneoplastic infiltration of the larynx with inflammatory cells can occur in dogs and cats, causing irregular proliferation, hyperemia, and swelling of the larynx. Clinical signs of an upper airway obstruction result. The larynx may appear grossly neoplastic during laryngoscopy but is differentiated from neoplasia on the basis of the histopathologic evaluation of biopsy specimens. Inflammatory infiltrates can be granulomatous, pyogranulomatous, or lymphocytic-plasmacytic. Etiologic agents have not been identified.

This syndrome is poorly characterized and probably includes several different diseases. Some animals respond to glucocorticoid therapy. Prednisone or prednisolone (1.0 mg/kg given orally q12h) is used initially. Once the clinical signs have resolved, the dose of prednisone can be tapered to the lowest amount that effectively maintains remission of clinical signs. Conservative excision of the tissue obstructing the airway may be necessary in animals with severe signs of upper airway obstruction or large granulomatous masses.

The prognosis varies, depending on the size of the lesion, the severity of laryngeal damage, and the responsiveness of the lesion to glucocorticoid therapy.

LARYNGEAL NEOPLASIA

Neoplasms originating from the larynx are uncommon in dogs and cats. More commonly, tumors originating in tissues adjacent to the larynx, such as thyroid carcinoma and lymphoma, compress or invade the larynx and distort normal laryngeal structures. Clinical signs of extrathoracic (upper) airway obstruction result. Laryngeal tumors include carcinoma (squamous cell, undifferentiated, and adenocarcinoma), lymphoma, melanoma, mast cell tumors and other sarcomas, and benign neoplasia. Lymphoma is the most common tumor in cats.

Clinical Features

The clinical signs of laryngeal neoplasia are similar to those of other laryngeal diseases and include noisy respiration, stridor, increased inspiratory efforts, cyanosis, syncope, and a change in bark or meow. Mass lesions can also cause concurrent dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia, or visible or palpable masses in the ventral neck.

Diagnosis

Extralaryngeal mass lesions are often identified by palpation of the neck. Primary laryngeal tumors are rarely palpable and are best identified by laryngoscopy. Laryngeal radiographs, ultrasonography, or computed tomography can be useful in assessing the extent of disease. Differential diagnoses include obstructive laryngitis, nasopharyngeal polyp, foreign body, traumatic granuloma, and abscess. For a definitive diagnosis of neoplasia to be made, histologic examination of a biopsy specimen of the mass must be done. A diagnosis of malignant neoplasia should not be made on the basis of the gross appearance alone.

Treatment

The therapy used depends on the type of tumor identified histologically. Benign tumors should be excised surgically, if possible. Complete surgical excision of malignant tumors is rarely possible, although ventilation may be improved and time may be gained to allow other treatments such as radiation or chemotherapy to become effective. Complete laryngectomy and permanent tracheostomy may be considered in select animals.

Braund KG, et al. Laryngeal paralysis-polyneuropathy complex in young Dalmatians. Am J Vet Res. 1994;55:534.

Burbridge HM. A review of laryngeal paralysis in dogs. Br Vet J. 1995;151:71.

Costello MF, et al. Acute upper airway obstruction due to laryngeal disease in 5 cats. Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2001;11:205.

Gabriel A, et al. Laryngeal paralysis-polyneuropathy complex in young related Pyrenean mountain dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2006;47:144.

Hammel SP, et al. Postoperative results of unilateral arytenoid lateralization for treatment of idiopathic laryngeal paralysis in dogs: 39 cases (1996-2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;228:1215.

Hendricks JC. Brachycephalic airway syndrome. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1992;22:1145.

Jakubiak MJ, et al. Laryngeal, laryngotracheal, and tracheal masses in cats: 27 cases (1998-2003). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2005;41:310.

MacPhail CM, et al. Outcome of and postoperative complications in dogs undergoing surgical treatment of laryngeal paralysis: 140 cases (1985–1998). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;218:1949.

Mahony OM, et al. Laryngeal paralysis-polyneuropathy complex in young Rottweilers. J Vet Intern Med. 1998;12:330.

Poncet CM, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal tract lesions in 73 brachycephalic dogs with upper respiratory syndrome. J Small Anim Pract. 2005;46:273.

Riecks TW, et al. Surgical correction of brachycephalic airway syndrome in dogs: 62 cases (1991-2004). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;230:1324.

Schachter S, et al. Laryngeal paralysis in cats: 16 cases (1990–1999). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;216:1100.

Torrez CV, et al. Results of surgical correction of abnormalities associated with brachycephalic airway syndrome in dogs in Australia. J Small Anim Pract. 2006;47:150.

White RAS. Unilateral arytenoid lateralisation: an assessment of technique and long term results in 62 dogs with laryngeal paralysis. J Small Anim Pract. 1989;30:543.

BOX 18-1

BOX 18-1 BOX 18-2

BOX 18-2