CHAPTER 16 Clinical Manifestations of Laryngeal and Pharyngeal Disease

CLINICAL SIGNS

LARYNX

Regardless of the cause, diseases of the larynx result in similar clinical signs, most notably respiratory distress and stridor. Voice change is specific for laryngeal disease but is not always reported. Clients may volunteer that they have noticed a change in their dog’s bark or cat’s meow, but specific questioning may be necessary to obtain this important information. Localization of disease to the larynx can generally be achieved with a good history and physical examination. A definitive diagnosis is made through a combination of laryngeal radiography, laryngoscopy, and laryngeal biopsy.

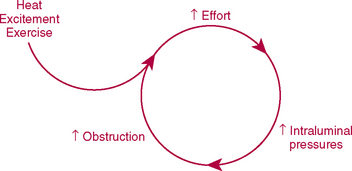

Respiratory distress resulting from laryngeal disease is due to airway obstruction. Although most laryngeal diseases are progressive over several weeks to months, animals typically present in acute distress. Dogs and cats are able to compensate for their disease initially through self-imposed exercise restriction. Often an exacerbating event occurs, such as exercise, excitement, or high ambient temperature, resulting in markedly increased respiratory efforts. These increased efforts lead to excess negative pressures on the diseased larynx, sucking the surrounding soft tissues into the lumen, and causing laryngeal inflammation and edema. Obstruction to airflow becomes more severe, leading to even greater respiratory efforts (Fig. 16-1). The airway obstruction can ultimately be fatal.

FIG 16-1 Patients with extrathoracic (upper) airway obstruction often present in respiratory distress as a result of a progressive worsening of airway obstruction after an exacerbating event.

A characteristic breathing pattern can often be identified on physical examination of patients in distress from extrathoracic (upper) airway obstruction, such as results from laryngeal disease (see Chapter 26). The respiratory rate is normal to only slightly elevated (often 30 to 40 breaths/min), which is particularly remarkable in the presence of overt distress. Inspiratory efforts are prolonged and labored, relative to expiratory efforts. The larynx tends to be sucked into the airway lumen as a result of negative pressure within the extrathoracic airways that occurs during inspiration, making inhalation of air more difficult. During expiration, pressures are positive in the extrathoracic airways, “pushing” the soft tissues open. Nevertheless, expiration may not be effortless. Some obstruction to airflow may occur during expiration with fixed obstructions, such as laryngeal masses. Even with the dynamic obstruction that results from laryngeal paralysis, in which expiration should be possible without any blockage to flow, resultant laryngeal edema and inflammation can interfere with normal expiration. On auscultation, referred upper airway sounds are heard and lung sounds are normal to increased.

Stridor, a high-pitched wheezing sound, is sometimes heard during inspiration. It is audible without a stethoscope, although auscultation of the neck may aid in identifying mild disease. Stridor is produced by air turbulence through the narrowed laryngeal opening. Narrowing of the extrathoracic trachea less commonly produces stridor.

In patients that are not presented for respiratory distress (e.g., for patients with exercise intolerance or voice change), it may be necessary to exercise the patient to identify the characteristic breathing pattern and stridor associated with laryngeal disease.

Some patients with laryngeal disease, particularly whose laryngeal paralysis is an early manifestation of diffuse neuromuscular disease or with distortion of normal laryngeal anatomy, have subclinical aspiration or overt aspiration pneumonia resulting from the loss of normal protective mechanisms. Patients may have clinical signs reflecting aspiration, such as cough, lethargy, anorexia, fever, tachypnea, and abnormal lung sounds. (See p. 309 for a discussion of aspiration pneumonia.)

PHARYNX

Space-occupying lesions of the pharynx can cause signs of upper airway obstruction as described for the larynx, but overt respiratory distress occurs only with advanced disease. More typical presenting signs of pharyngeal disease are stertor, reverse sneezing, gagging, retching, and dysphagia. Stertor is a loud, coarse sound such as that produced by snoring or snorting. Stertor results from excessive soft tissue in the pharynx, such as an elongated soft palate or mass, causing turbulent air flow. Reverse sneezing (see p. 210), gagging, or retching may occur from local stimulation from the tissue itself or from secondary secretions. Dysphagia results from physical obstruction, usually because of a mass. As with laryngeal disorders, a definitive diagnosis is made through a combination of visual examination, radiography, and biopsy of abnormal tissue. Visual examination includes a thorough evaluation of the oral cavity, larynx (see p. 239), and caudal nasopharynx (see p. 215).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES FOR LARYNGEAL SIGNS IN DOGS AND CATS

Differential considerations for dogs and cats with respiratory distress are discussed in Chapter 26.

Dogs are more commonly presented for laryngeal disease than cats and usually have laryngeal paralysis (Box 16-1). Laryngeal neoplasia can occur in dogs or cats. Obstructive laryngitis is a poorly characterized inflammatory disorder. Other possible diseases of the larynx include laryngeal collapse (see p. 241), web formation (i.e., adhesions or fibrotic tissue across the laryngeal opening, usually as a complication of surgery), trauma, foreign body, and compression caused by an extraluminal mass. Acute laryngitis is not a wellcharacterized disease in dogs or cats but presumably could result from viral or other infectious agents, foreign bodies, or excessive barking.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES FOR PHARYNGEAL SIGNS IN DOGS AND CATS

The most common pharyngeal disorders in dogs are brachycephalic airway syndrome and elongated soft palate (Box 16-2). Elongated soft palate is a component of brachycephalic airway syndrome and is discussed with this disorder in Chapter 18 (p. 244), but it can also occur in nonbrachycephalic dogs. The most common pharyngeal disorders in cats are lymphoma and nasopharyngeal polyps (Allen et al., 1999). Nasopharyngeal polyps, nasal tumors, and foreign bodies are discussed in the chapters on nasal diseases (see Chapters 13 to 15). Other differential diagnoses are abscess or granuloma and compression caused by an extraluminal mass.

BOX 16-1

BOX 16-1