CHAPTER 26 Emergency Management of Respiratory Distress

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Respiratory distress, or dyspnea, refers to an abnormally increased effort in breathing. Some authors prefer to use terms such as hyperpnea and increased respiratory effort in reference to this abnormality because dyspnea and distress imply feelings that cannot be determined with certainty in animals. Breathing difficulties are extremely stressful for people and are likely so for dogs and cats as well. Dyspnea is also physically exhausting to the animal as a whole and to the respiratory musculature specifically. Animals in respiratory distress at rest should be managed aggressively, and their clinical status should be frequently assessed.

A dog or cat in respiratory distress may show orthopnea, which is a difficulty in breathing in certain positions. Animals with orthopnea will assume a sitting or standing position with their elbows abducted and neck extended. Movement of the abdominal muscles that assist ventilation may be exaggerated. Cats normally have a minimal visible respiratory effort. Cats that show noticeable chest excursions or open-mouth breathing are severely compromised. Cyanosis, in which normally pink mucous membranes are bluish, is a sign of severe hypoxemia and indicates that the increased respiratory effort is not sufficiently compensating for the degree of respiratory dysfunction. Pallor of the mucous membranes is a more common sign of acute hypoxemia resulting from respiratory disease than is cyanosis.

Respiratory distress caused by respiratory tract disease most commonly develops as a result of large airway obstruction, severe pulmonary parenchymal or vascular disease (i.e., pulmonary thromboembolism), pleural effusion, or pneumothorax. Respiratory distress can also occur as a result of primary cardiac disease causing decreased perfusion, pulmonary edema, or pleural effusion (see Chapter 1). In addition, noncardiopulmonary causes of hyperpnea must be considered in animals with apparent distress, including severe anemia, hypovolemia, acidosis, hyperthermia, and neurologic disease. Normal breath sounds may be increased in dogs and cats with these diseases, but crackles or wheezes are not expected.

A physical examination should be performed rapidly, paying particular attention to the breathing pattern, auscultatory abnormalities of the thorax and trachea, pulses, and mucous membrane color and perfusion. Attempts at stabilizing the animal’s condition should then be made before initiating further diagnostic testing.

Dogs and cats in shock should be treated appropriately (see Chapter 30). Most animals in severe respiratory distress benefit from decreased stress and activity, placement in a cool environment, and oxygen supplementation. Cage rest is extremely important, and the least stressful method of oxygen supplementation should be used initially (see Chapter 27). An oxygen cage achieves both these goals, with the disadvantage that the animal is inaccessible. Sedation of the animal may be beneficial (Box 26-1). More specific therapy depends on the location and cause of the respiratory distress (Table 26-1).

BOX 26-1 Drugs Used to Decrease Stress in Animals with Respiratory Distress

BOX 26-1 Drugs Used to Decrease Stress in Animals with Respiratory Distress

IV, Intravenously; SQ, subcutaneously; IM, intramuscularly.

| Upper Airway Obstruction: Decreases Anxiety and Lessens Respiratory Efforts, Decreasing Negative Pressure within Upper Airways | ||

| Acepromazine | Dogs and cats | 0.05 mg/kg IV, SQ |

| Morphine | Dogs only, particularly brachycephalic dogs | 0.1 mg/kg IV; repeat q3min to effect; duration, 1-4 hr |

| Pulmonary Edema: Decreases Anxiety; Morphine Reduces Pulmonary Venous Pressure | ||

| Morphine | Dogs only | 0.1 mg/kg IV; repeat q3min to effect; duration, 1-4 hr |

| Acepromazine | Dogs and cats | 0.05 mg/kg IV, SQ; duration, 3-6 hr |

| Rib Fractures, After Thoracotomy, Other Trauma: Pain Relief | ||

| Hydromorphone | Dogs | 0.05 mg/kg IV, IM; can repeat IV q3mim to effect; duration, 2-4 hr |

| Cats | 0.025-0.05 mg/kg IV, IM; can repeat IV q3min to effect but stop if mydriasis occurs; duration, 2-4 hr | |

| Butorphanol | Cats | 0.1 mg/kg IV, IM, SQ; can repeat IV q3min to effect; duration, 1-6 hr |

| Buprenorphine | Dogs and cats | 0.005 mg/kg IV, IM; repeat to effect; duration, 4-8 hr |

LARGE AIRWAY DISEASE

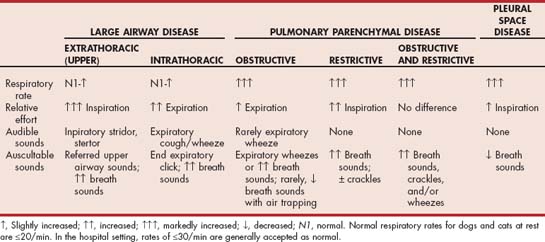

Diseases of the large airways result in respiratory distress by obstructing the flow of air into the lungs. For the purposes of these discussions, extrathoracic large airways (otherwise known as upper airways) include the pharynx, larynx, and trachea proximal to the thoracic inlet; intrathoracic large airways include the trachea distal to the thoracic inlet and bronchi. Animals presenting in respiratory distress caused by large airway obstruction typically have a markedly increased respiratory effort with a minimally increased respiratory rate (see Table 26-1). Excursions of the chest may be increased (i.e., deep breaths are taken). Breath sounds are often increased.

EXTRATHORACIC (UPPER) AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Patients with extrathoracic (upper) airway obstruction typically have the greatest breathing effort during inspiration, which is generally prolonged relative to expiration. Stridor or stertor is usually heard, generally during inspiration. A history of voice change may be present with laryngeal disease.

Laryngeal paralysis and brachycephalic airway syndrome are the most common causes of upper airway obstruction (see Chapter 18). Other laryngeal and pharyngeal diseases are listed in Boxes 16-1 and 16-2. Severe tracheal collapse can result in extrathoracic or intrathoracic large airway obstruction or both. Rarely, other diseases of the extrathoracic trachea, such as foreign body, stricture, neoplasia, granuloma, and hypoplasia, result in respiratory distress.

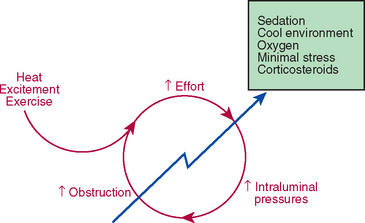

Patients with extrathoracic airway obstruction usually present with acute distress in spite of the chronic nature of most of these diseases because of a vicious cycle of increased respirations leading to increased obstruction, as described in Chapter 16. This cycle can almost always be broken with medical management (Fig. 26-1). The patient is sedated (see Box 26-1) and provided a cool, oxygen-rich environment (e.g., oxygen cage). For dogs with pharyngeal disease, primarily brachycephalic airway syndrome, morphine is given. Otherwise, acepromazine is used. Subjectively, dogs with brachycephalic airway syndrome seem to have more difficulty maintaining a patent airway when sedated with acepromazine compared with morphine. Short-acting corticosteroids are thought by some to be effective in decreasing local inflammation (e.g., dexamethasone, 0.1 mg/kg intravenously [IV], or prednisolone sodium succinate, up to 10 mg/kg IV).

FIG 26-1 Patients with extrathoracic (upper) airway obstruction often present in acute respiratory distress because of a progressive worsening of airway obstruction after an exacerbating event. Medical intervention is nearly always successful in breaking this cycle and stabilizing the patient’s respiratory status.

In rare cases, sedation and oxygen supplementation will not resolve the respiratory distress and the obstruction must be physically bypassed. Placement of an endotracheal tube is generally effective. A short-acting anesthetic agent is administered. Long and narrow endotracheal tubes with stylets should be available to pass by large or deep obstructions. If an endotracheal tube cannot be placed, a transtracheal catheter can be inserted distal to the obstruction (see Chapter 27). If a tracheostomy tube is needed, it can then be placed under controlled, sterile conditions. It is rarely necessary to perform a nonsterile emergency tracheostomy.

INTRATHORACIC LARGE AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Respiratory distress caused by intrathoracic large airway obstruction is rare. Patients with intrathoracic large airway obstruction typically have the greatest breathing effort during expiration, which is generally prolonged relative to inspiration. The most common cause of intrathoracic large airway obstruction is collapse of the mainstem bronchi and/or intrathoracic trachea (tracheobronchomalacia; see Chapter 21). A high-pitched, wheezing, coughlike sound is often heard during expiration in these patients, and crackles or wheezes may be auscultated. Other differential diagnoses include foreign body, advanced Oslerus infection, tracheal neoplasia, tracheal stricture, and bronchial compression by extreme hilar lymphadenopathy.

Sedation, oxygen supplementation, and minimizing stress as described for the management of upper airway obstruction are often effective in stabilizing these patients as well. High doses of hydrocodone or butorphenol will provide cough suppression and sedation (see Chapter 21). Dogs with chronic bronchitis may benefit from bronchodilators and corticosteroids.

PULMONARY PARENCHYMAL DISEASE

Diseases of the pulmonary parenchyma result in hypoxemia and respiratory distress through a variety of mechanisms, including the obstruction of small airways (obstructive lung disease; e.g., idiopathic feline bronchitis); decreased pulmonary compliance (restrictive lung disease, “stiff” lungs; e.g., pulmonary fibrosis); and interference with pulmonary circulation (e.g., pulmonary thromboembolism). The majority of patients with pulmonary parenchymal disease, such as those with pneumonias or pulmonary edema, develop hypoxemia through a combination of these mechanisms that contribute to V./Q. mismatch (see Chapter 20), including airway obstruction and alveolar flooding, and decreased compliance.

Animals presenting in respiratory distress caused by pulmonary parenchymal disease typically have a markedly increased respiratory rate (see Table 26-1). Patients with primarily obstructive disease, usually cats with bronchial disease, may have prolonged expiration relative to inspiration with increased expiratory efforts. Expiratory wheezes are commonly auscultated. Patients with primarily restrictive disease, usually dogs with pulmonary fibrosis, may have prolonged inspiration relative to expiration and effortless expiration. Crackles are commonly auscultated. Occasionally, cats with severe bronchial disease will develop a restrictive breathing pattern in association with air trapping and hyperinflation of the lungs. Other patients, with a combination of these processes occurring, have increased efforts during both phases of respiration; shallow breathing; and crackles, wheezes, or increased breath sounds on auscultation. Differential diagnoses for dogs and cats with pulmonary disease are provided in Box 19-1.

Oxygen therapy is the treatment of choice for stabilizing dogs or cats with severe respiratory distress believed to be caused by pulmonary disease (see Chapter 27). Bronchodilators, diuretics, or glucocorticoids can be considered as additional treatments if oxygen therapy alone is not adequate.

Bronchodilators, such as short-acting theophyllines or β-agonists, are used if obstructive lung disease is suspected because they decrease bronchoconstriction. In combination with oxygen, they are the treatment of choice for cats with signs of bronchitis (see Chapter 21). Subcutaneous terbutaline (0.01 mg/kg, repeated in 5 to 10 minutes if necessary) or albuterol administered by metered dose inhaler are most often used in emergency situations. Bronchodilators are described in more detail in Chapter 21 (see pp. 290 and 296 and Box 21-2).

Diuretics, such as furosemide (2 mg/kg, administered intravenously), are indicated for the management of pulmonary edema. If edema is among the differential diagnoses of an unstable patient, a short trial of furosemide therapy is reasonable. However, potential complications of diuretic use resulting from volume contraction and dehydration should be taken into consideration. Continued use of diuretics is contraindicated in animals with exudative lung disease or bronchitis because systemic dehydration results in the drying of airways and airway secretions. The mucociliary clearance of airway secretions and contaminants is decreased, and airways are further obstructed with mucus plugs.

Glucocorticoids decrease inflammation. Rapid-acting formulations, such as prednisolone sodium succinate (up to 10 mg/kg, administered intravenously), are indicated for animals in severe respiratory distress caused by the following conditions: idiopathic feline bronchitis, thromboembolism after adulticide treatment for heartworms, allergic bronchitis, pulmonary parasitism, and respiratory failure soon after the initiation of treatment for pulmonary mycoses. Animals with other inflammatory diseases or acute respiratory distress syndrome may respond favorably to glucocorticoid administration. The potential negative effects of corticosteroids must be considered before their use. For example, the immunosuppressive effects of these drugs can result in the exacerbation of an infectious disease. Although the use of short-acting corticosteroids for the acute stabilization of such cases probably will not greatly interfere with appropriate antimicrobial therapy, long-acting agents and prolonged administration should be avoided. Glucocorticoid therapy potentially interferes with the results of future diagnostic tests, particularly if lymphoma is a differential diagnosis. Appropriate diagnostic tests are performed once the patient can tolerate the stress.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are administered if there is evidence of sepsis (e.g., fever, neutrophilic leukocytosis with left shift and moderate to marked toxicity of neutrophils) or a high degree of suspicion of bacterial or aspiration pneumonia. Note that airway specimens (usually tracheal wash) should be obtained for culture if at all possible before initiating broad-spectrum antibiotics in order to confirm the diagnosis of bacterial infection and to obtain susceptibility data. Specimens obtained after initiating antibiotics are often not diagnostic, even with continued progression of signs. However, airway sampling may not be possible in these unstable patients. If sepsis is suspected, blood and urine cultures may be useful. The diagnosis and treatment of bacterial and aspiration pneumonia are described in Chapter 22.

If the dog or cat does not respond to this management, it may be necessary to intubate the patient and institute positive-pressure ventilation (see Chapter 27) until a diagnosis can be established and specific therapy initiated.

PLEURAL SPACE DISEASE

Pleural space diseases cause respiratory distress by preventing normal lung expansion. They are similar mechanistically to restrictive lung disease. Animals presenting in respiratory distress as a result of pleural space disease typically have a markedly increased respiratory rate (see Table 26-1). Relatively increased inspiratory efforts may be noted but are not always obvious. Decreased lung sounds on auscultation distinguish patients with tachypnea caused by pleural space disease from patients with tachypnea caused by pulmonary parenchymal disease. Increased abdominal excursions during breathing may be noted.

Most patients in respiratory distress resulting from pleural space disease have pleural effusion or pneumothorax (see Chapter 23). Other differential diagnoses are diaphragmatic hernia and mediastinal masses. If pleural effusion or pneumothorax is suspected to be causing respiratory distress, needle thoracocentesis (see Chapter 24) should be performed immediately before further diagnostic testing is performed or any drugs are administered. Oxygen can be provided by mask while the procedure is performed, but successful drainage of the pleural space will quickly improve the animal’s condition. Occasionally, emergency placement of a chest tube is necessary to evacuate rapidly accumulating air (see Chapter 24).

As much fluid or air should be removed as possible. The exception is in animals with acute hemothorax. Hemothorax is usually the result of trauma or rodenticide intoxication. The respiratory distress associated with hemothorax is often the result of acute blood loss rather than an inability to expand the lungs. In this situation, as little volume as is needed to stabilize the animal’s condition is removed. The remainder will be reabsorbed (autotransfusion), to the benefit of the animal. Aggressive fluid therapy is indicated.

TABLE 26-1

TABLE 26-1