Care of the Surgical Patient

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Discuss reasons for which surgery might be performed.

2 Assess for potential risk factors for complications of surgery.

3 Explain the nurse’s role in the various phases of perioperative nursing.

4 Discuss how robotic surgery has made recovery time shorter.

5 Identify the types of anesthesia used for surgery.

6 State the safety measure now in place to prevent errors regarding the surgical site.

7 Assist the patient with psychological preparation for surgery.

8 Define the nurse’s role during the signing of a consent for surgery.

9 Discuss differences in the roles of the scrub person and the circulating nurse.

10 List interventions to prevent each of the potential postoperative complications.

1 Implement physical preparation of the patient before surgery.

2 Perform preoperative teaching for the patient and family.

3 Prepare to perform an immediate postoperative assessment when a patient returns to the nursing unit.

4 Promote adequate ventilation of the lungs during recovery from anesthesia.

5 Assess for postoperative pain and provide comfort measures and pain relief.

6 Promote early ambulation and return to independence in activities of daily living.

7 Perform discharge teaching necessary for postoperative home self-care.

anesthesia ( , p. 750)

, p. 750)

atelectasis ( , p. 768)

, p. 768)

autotransfusion (p. 755)

conscious (p. 751)

curative surgery (p. 748)

dehiscence ( , p. 773)

, p. 773)

elective (p. 748)

embolus ( , p. 771)

, p. 771)

evisceration ( , p. 773)

, p. 773)

laser (p. 750)

palliative surgery ( , p. 748)

, p. 748)

paralytic ileus ( , p. 771)

, p. 771)

perioperative ( , p. 749)

, p. 749)

pneumonia ( , p. 772)

, p. 772)

prosthesis ( , p. 754)

, p. 754)

stasis ( , p. 755)

, p. 755)

thrombophlebitis ( , p. 755)

, p. 755)

thrombosis ( , p. 768)

, p. 768)

unconscious (p. 751)

REASONS FOR SURGERY

Surgery is performed for a variety of reasons. A procedure may be elective (voluntary), such as when a hernia repair is scheduled a week away. Emergency surgery is often necessary in trauma cases in which serious consequences will occur if surgery is not done immediately. Palliative surgery (pain or complication relieving) is performed to make a patient more comfortable. Removing a metastatic tumor that is causing considerable pain from the abdomen is an example. Diagnostic surgery, such as a biopsy of a mass, is done to provide data for a diagnosis of the problem. Reconstructive surgery, such as mammoplasty after a mastectomy, is done to restore appearance or function. Curative surgery alleviates (cures) a problem, such as when a gallbladder that is full of stones, causing blockage or pain, is removed.

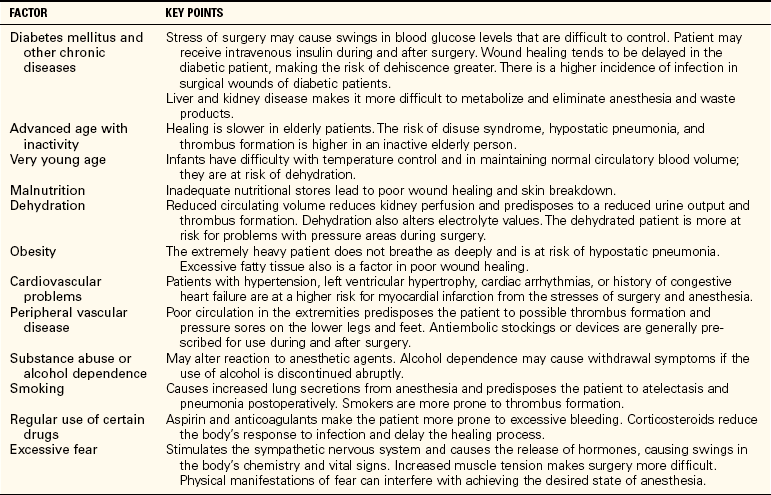

PATIENTS AT HIGHER RISK FOR SURGICAL COMPLICATIONS

The infant and the elderly person are at higher risk for complications of surgery due to either immature body systems or a decline in function of various body systems. Maintaining core body temperature is one concern for these patients. Both age groups are at risk for dehydration or overhydration. Aging causes changes in the cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, integumentary, neurologic, and metabolic systems. Elderly patients must be watched and assessed for complications very closely during and after surgery. Other types of patients who are at higher risk during and after surgery are those with bleeding disorders, cancer, heart disease, chronic respiratory disease, liver disease, immune disorders, chronic pain, upper respiratory infection, or fever, or who abuse street drugs (Table 37-1). These patients are subject to a variety of complications and should be carefully assessed during the postoperative period.

All patients are at risk for surgical site infection. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched a campaign to reduce incidents of medical harm. Box 37-1 lists the recommended measures to reduce surgical site infection in patients.

PERIOPERATIVE NURSING

Perioperative nursing refers to the care of the patient from the time of the decision to have surgery through recovery from the procedure. Learning the terminology for surgical procedures will help in identifying what the surgeon is going to do (Box 37-2). Surgery may be performed as a same-day or outpatient procedure or an inpatient procedure in a hospital or surgery center. Minor surgery is often performed in a physician’s office. Patients having same-day surgery are admitted early in the morning and discharged in the afternoon. Preparation for surgery is usually begun before admission. The patient has diagnostic tests done in the days just before the scheduled surgery. Teaching for postoperative care must be done efficiently since time of stay is short to reduce hospitalization costs (Home Care Considerations 37-1). Your ability to deliver and reinforce teaching for postoperative and home care is crucial to the well-being and quick recovery of your patients.

ENHANCEMENTS TO SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Laser (light amplification by the stimulated emission of radiation) surgery is common today and is often combined with microscopic, endoscopic, and robotic-enhanced procedures. A laser is a tube that contains a medium such as carbon dioxide or another active gas, which is energized by electricity. Mirrors reflect the energized molecules back and forth and a bright light is generated in the form of a beam. The light beam is converted to heat as tissue absorbs it. There are several varieties of lasers for different uses.

FIBEROPTIC SURGERY

Fiberoptics allows the use of endoscopes with high-resolution video cameras passed through a very small incision for an ever-increasing variety of surgical procedures. Operating microscopes can be combined with an endoscope for microscopic surgery. Small growths and organs can be removed without making a traditional surgical incision. However, two or three other puncture holes are made for the instruments and video camera attachment that provide access and a visual field for the procedure.

ROBOTIC SURGERY

More surgeons are using remote-controlled robots to perform surgeries. Robotics is seen as a key to less invasive, less traumatic surgeries in the future. The robot is operated from a nearby computer while the surgeon views magnified three-dimensional images of the surgical field on the computer’s screen. The robot’s tiny camera has multiple lenses that allow magnification up to 12 times that of normal vision. There are assistants and a second surgeon next to the patient, but the main surgeon performs the surgery at the computer. For heart surgery, the robot’s needle-like “fingers” are introduced through pencil-sized holes in the chest to perform certain heart surgery techniques. Remote-controlled instruments are inserted through small incisions. Various types of robotics that are voice activated by the surgeon are undergoing use. Computer Motion is a firm located in Santa Barbara, California, that is a pioneer in this field. These machines can provide very precise movements for the surgeon.

A big advantage of using the robot is that it has “rock-steady” hands, providing precision that is beyond human dexterity. Because only small incisions are needed, the patient has less pain postoperatively and requires less time to heal. There is less scarring and it seems that fewer infections develop with this new surgical technique.

ANESTHESIA

Anesthesia (the loss of sensory perception) has been in use for surgical procedures since the 1840s. Newer anesthetics and techniques make anesthesia safer than ever, but there is still a risk any time a patient is anesthetized. The goals of anesthesia administration are (1) to prevent pain; (2) to achieve adequate muscle relaxation; and (3) to calm fear, ease anxiety, and induce forgetfulness of an unpleasant experience. Anesthetics are administered in a number of ways to achieve these goals. The choice of anesthesia rests with the anesthesiologist. The type of surgery to be performed and the age and physical condition of the patient are the influencing factors.

GENERAL ANESTHESIA

General anesthesia is induced by the administration of an inhalant gas or by medication introduced intravenously. During general anesthesia, the patient is in a deep sleep state with muscle relaxation and is not aware of anything going on in the operating room. There are four stages of general anesthesia (Box 37-3).

When the patient awakens from anesthesia, progression through the stages occurs in reverse. Quiet must be maintained while the patient is in stage II because noise may cause the patient to become excited, resulting in instability of vital signs.

REGIONAL ANESTHESIA

Regional anesthesia is accomplished by administering a nerve block. It is often more economical than general anesthesia. This may be accomplished by injecting the spinal, epidural, caudal, or peripheral nerve area. The block anesthetizes the local area or the area distal to the block. Spinal or epidural blocks are frequently used for high-risk patients undergoing pelvic or lower extremity surgery; epidural blocks are widely used in obstetric procedures.

PROCEDURAL (MODERATE) SEDATION ANESTHESIA

A local anesthetic agent at the surgical site plus intravenous sedation is used to provide systemic analgesia and conscious (awareness of one’s surroundings) sedation as well as depress the autonomic nervous system. The technique can be used for any surgery or procedure that can be done with local anesthesia and is being used more and more frequently. The patient is monitored closely for blood pressure changes, oxygen saturation levels, and heart activity.

LOCAL ANESTHESIA

Local anesthesia is used for minor procedures such as superficial tissue biopsies, surface cyst excision, insertion of a pacemaker, and insertion of vascular access devices. The patient who has had local anesthesia is transferred directly to the nursing unit and does not need care in the postanesthesia care recovery unit (PACU, also called PAR or PARU).

PREOPERATIVE PROCEDURES

Care of the surgical patient is divided into four phases: preoperative, intraoperative, postanesthesia immediate care, and postoperative care. During the preoperative phase, nonanemic patients may donate their own blood 2 to 4 weeks prior to surgery to be banked in case of postoperative autologous (related to self) transfusion need. This eliminates any possibility of transfusion with blood contaminated with a blood-borne virus, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis B or C.

SURGICAL CONSENT

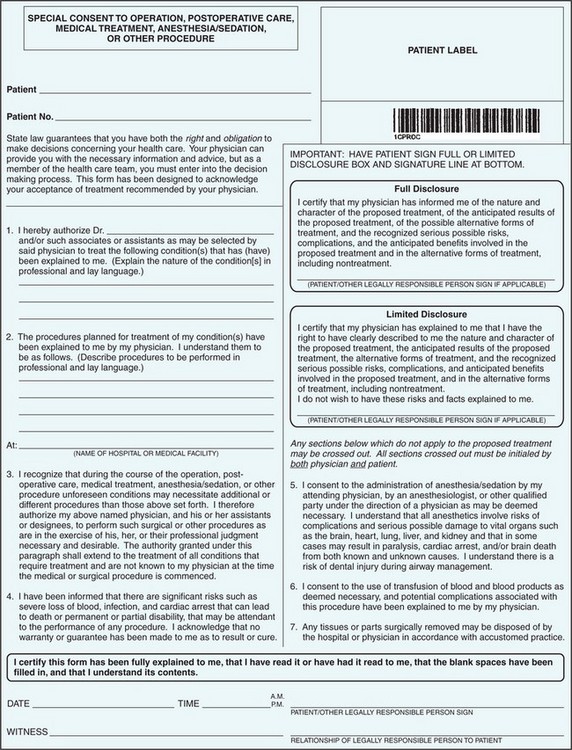

A surgical consent form must be signed prior to surgery before preoperative medications are given, when the patient’s mind is not affected by the medications (Figure 37-1). This is a legal form that must be filled out in ink with the correct spelling of procedures to be done. The surgeon is responsible for obtaining an informed surgical consent. The need for the procedure, a description of the procedure to be performed, its risks and benefits, and alternative treatments available and their possible consequences must be explained to the patient in understandable terms, and the explanation (not just the patient’s signature) should be witnessed by at least one health care professional. Any questions must be answered. The surgeon often explains the procedure with the nurse present, answers questions, and then asks the nurse to obtain the signature of the patient on the form. If the patient does not understand the procedure, or has further questions for the surgeon, refer the matter back to the surgeon. If the patient is a minor, is confused, or is mentally incompetent, another responsible party such as a parent, spouse, or guardian must be present for the explanation and may need to be the person to sign the consent form. The signature of the patient or responsible party must be witnessed by another party, usually a staff member. The consent form must show the procedure to be performed and the risks involved, must include the time and date, and must be signed in ink. A witnessed “X” is acceptable if the patient cannot sign with a signature.

If an emergency surgery is needed and the patient is not conscious or able to give consent, an attempt to contact immediate family is made. Telephone permission may be given as long as there are two witnesses on extension lines. If no family can be found, the opinion of a second surgeon regarding the need for surgery is sought and then the surgery may take place. All responsible adults are asked to complete advance directives when admitted to the hospital if they do not already have such a document on file; these are discussed in Chapter 3. Advance directives indicate the patient’s desires regarding lifesaving or life-preserving measures in the event of a cardiac arrest or other complication that threatens basic function.

SURGICAL SITE IDENTIFICATION

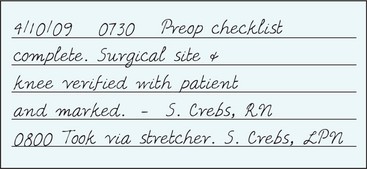

In 2003, a National Patient Safety Goal was instituted to “Eliminate wrong-site, wrong-patient, wrong-procedure surgery.” A preoperative checklist verification process is used to ensure that appropriate medical records and imaging studies are available. A process must also be implemented to mark the surgical site and involve the patient in the marking process. This should be done before preoperative medications are given so that the patient is alert to participate in this procedure. Before surgery commences, a “time-out” is called and the correct patient, correct site, and correct body part are verified by the operating team via the chart orders, operative permit, and imaging studies.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The referring physician, surgeon, or surgical resident takes a medical history and performs a physical examination. This may be done in the physician’s office. The dictated report must be in the record before the patient goes to surgery. The patient should be in the best possible physical condition, unless it is an emergency procedure that will be performed.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Diagnostic test data that are usually required before surgery include a complete blood cell count (CBC) and urinalysis. A chest x-ray is performed, and an electrocardiogram (ECG) is often ordered for many patients over 40 years of age. Other tests ordered may be tests to determine pregnancy; tests to determine electrolyte and blood glucose levels; tests indicating blood clotting ability, such as the prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APPT); blood type and crossmatch for transfusion; and a profile that gives data about liver and kidney function. Most surgeons will postpone surgery if the patient’s hemoglobin level is below 10 g/dL. The surgeon orders the tests, but you will need to explain to the patient why they are being done. Test values that are outside of normal ranges should be noted on the preoperative checklist as well as brought to the attention of the surgeon.

PREOPERATIVE CARE

During the preoperative period, the patient is prepared physically and psychologically for surgery. As much privacy as possible should be provided. If the patient is very ill, a significant other may join in the interview process. For the best result, focus completely on the patient in an unhurried manner. Ask open-ended questions and avoid judgmental responses.

Assessment (Data Collection)

The nursing history and assessment focus on possible factors that indicate the patient is at higher risk for complications from surgery (see Table 37-1). An important part of your assessment is determining what supplements and herbs a patient is using (Table 37-2). The surgeon and anesthesiologist must be aware of what substances are in the patient’s body in addition to their normal medications. Besides checking for drug allergies, it is important to determine whether the patient has a latex allergy.

Table 37-2

Herbs and Supplements Affecting Surgical Outcomes

| SUBSTANCE | POSSIBLE EFFECT |

| Echinacea | May cause liver inflammation if used with certain medications |

| Feverfew | May inhibit platelet aggregation and increase bleeding |

| Garlic, ginger, ginkgo biloba, ginseng, or valerian | May increase bleeding tendency, particularly if receiving anticoagulants |

| Goldenseal | May increase blood pressure; may cause increased swelling |

| Kava | May prolong effects of anesthetics or antiseizure medication; may cause liver damage |

| Licorice | May alter electrolytes, increase blood pressure, or increase fluid retention |

| St. John’s wort | May prolong the effect of anesthetic agents |

| Vitamin E or aspirin | May increase bleeding, particularly in conjunction with anticoagulants |

Adapted from Lewis, S.L., Heitkemper, M.M., Dirksen, S.R., et al. (2007). Medical-Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems (7th ed., p. 347). St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby.

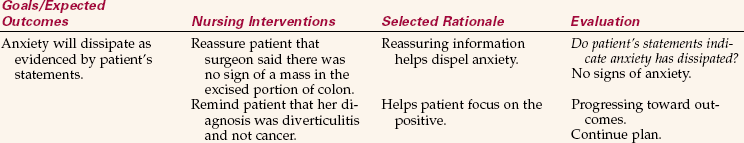

Psychosocial assessment includes attitudes and concerns about any changes in body image and lifestyle that the surgery may cause (Box 37-4, Communication Cues 37-1).

Cultural beliefs and values regarding surgery must be taken into consideration (Cultural Cues 37-1). If the patient does not speak the same language as the surgical team, an interpreter should be enlisted to assist with communication. If a female patient’s culture has strict rules for female attire, she needs assurance of sufficient privacy and protection of modesty to allay any fears she might have; such issues and interventions must be conveyed to the operating room. If there are certain cultural taboos regarding an aspect of the surgery, the surgical team needs to know about them and plan a way to achieve a good outcome without violating such a taboo. It is especially important to know whether the patient will accept a blood transfusion. Jehovah’s Witnesses usually do not wish to have blood administered.

The operating room is notified if the patient is hard of hearing, is essentially blind when glasses are not in place, or has a prosthesis (artificial body part).

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing diagnoses in the preoperative stage include actual and potential problems identified by your data collection and the RN assessment. Examples of common nursing diagnoses are as follows:

• Anxiety related to the surgical experience and outcome

• Fear related to risk for death, effects of impending surgery, or loss of control due to anesthesia

• Anticipatory grieving related to impending loss of a body function or body part

• Deficient knowledge related to preoperative and postoperative routines

• Sleep deprivation related to stress or unfamiliar environment

• Ineffective coping related to lack of problem-solving skills or adequate support

• Ineffective role performance related to inability to care for children during hospitalization

Planning

Expected outcomes are written for the specific individual nursing diagnoses assigned to each patient. However, general goals for all preoperative patients are the same in that the patient will be as follows:

• Prepared for surgery physically and emotionally

• Able to demonstrate deep breathing, coughing, and leg exercises

• Able to verbalize understanding of the procedure and the expectations of him in the postoperative period

• Able to maintain fluid and electrolyte balance throughout the perioperative period

When preoperative patients are assigned, you must plan the work for the shift carefully to have the patients ready without neglecting the needs of other assigned patients. At the beginning of the shift, check to see that any ordered preoperative medications are on hand. Check the surgery schedule and estimate the time that the patient will need to be prepared for surgery.

Implementation

Preoperatively, your time is divided between preparing the patient for surgery and teaching about what will happen and how to assist in the recovery period. The same-day surgery patient receives teaching from the physician’s office nurse or a surgical intake nurse. Teaching sessions may be scheduled when the patient comes for diagnostic testing. Sending written instructions home with the patient reinforces what has been taught. The patient should be given a phone number to call for answers to questions that arise before entering the hospital for surgery. Many scheduled surgery patients begin care in the same-day surgery unit rather than spending the night in the hospital before surgery.

Teaching for Postoperative Exercises: Teaching the patient breathing, coughing, turning, and leg exercises is a high priority during the preoperative period. Venous return is often hampered during the surgical procedure due to the position assumed on the operating table and pooling of blood in the lower extremities. The stasis (stoppage of flow) of blood places the patient at risk for thrombophlebitis (blood clot causing inflammation of a vessel). Specific leg exercises help to prevent this complication (Figure 37-2). Explain the importance of doing the exercises and show the patient how to do each one; ask for a return demonstration (Patient Teaching 37-1).

For deep breathing and coughing, it is preferable for the patient to sit up with the back away from the mattress or chair. This allows for full lung expansion. The surgical incision should be splinted with a pillow (Figure 37-3).

Deep breathing and coughing should be performed every 2 hours for 72 hours after general anesthesia. The surgeon may order use of an incentive spirometer. Instruct the patient in its use and supervise until the patient has mastered the technique (Patient Teaching 37-2). Help the same-day surgery patient devise a schedule for doing the exercises.

Show the patient how to turn in bed by flexing the legs to relax the abdominal muscles, grabbing on to the side rail, and slowly turning to the side. This maneuver is also used for getting up out of bed. The patient is also instructed in what to expect before, during, and after surgery.

NPO Status: Food and fluids will often be restricted before surgery, and the patient is placed on NPO (nothing by mouth) status. A light meal such as toast and clear fluids may be allowed up to 6 hours before surgery and a heavier meal 8 hours prior to surgery. For elective surgery, the American Society of Anesthesiology revised the practice guideline in 1999 for preoperative fasting in healthy patients. Clear liquids such as black coffee, tea, apple juice, or carbonated beverages may be consumed up to 2 hours before surgery in some elective cases. Sometimes the surgeon will allow an oral blood pressure or heart medication to be given with a sip of water the morning of surgery. Always check the physician’s order before giving anything by mouth in the immediate preoperative period. The purpose of the restriction is to prevent vomiting and aspiration, which can occur with anesthesia, but is rarely seen with modern anesthesia.

Elimination: If the patient is having colon surgery, enemas may be ordered to be given until clear. The patient may be on a special soft or liquid diet for the 3 days prior to surgery to decrease the content of the bowel.

Expected Tubes and Equipment: If a nasogastric tube will be inserted during surgery for postoperative use, explain its purpose, care, and what it will feel like to the patient. Give an estimate of how long the tube will remain in the stomach. Explain the function of other expected tubes such as drains, intravenous (IV) line, oxygen delivery and monitoring devices, chest tube, and urinary catheter, as well as their care and probable duration of use.

Rest and Sedation: It is desirable for the patient to be as well rested as possible prior to surgery so the body is not compromised in meeting the stresses of anesthesia and the procedure. A sedative is usually ordered for the night before surgery, but, if in the hospital, the patient often must ask for it. Same-day surgery patients need to be told how early to take the sedative and retire the night before surgery because it will be necessary to arise early to enter the hospital.

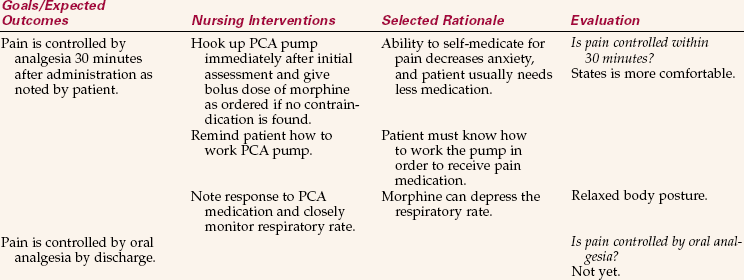

Pain Control: Many surgeons will order a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump for their patients postoperatively. If this is to be the case, patients should receive instruction about the pump and how to operate it prior to surgery. If patients will be receiving injections for pain control, explain that this type of medication is ordered on an as-needed basis every 3 to 4 hours and that they must ask for it.

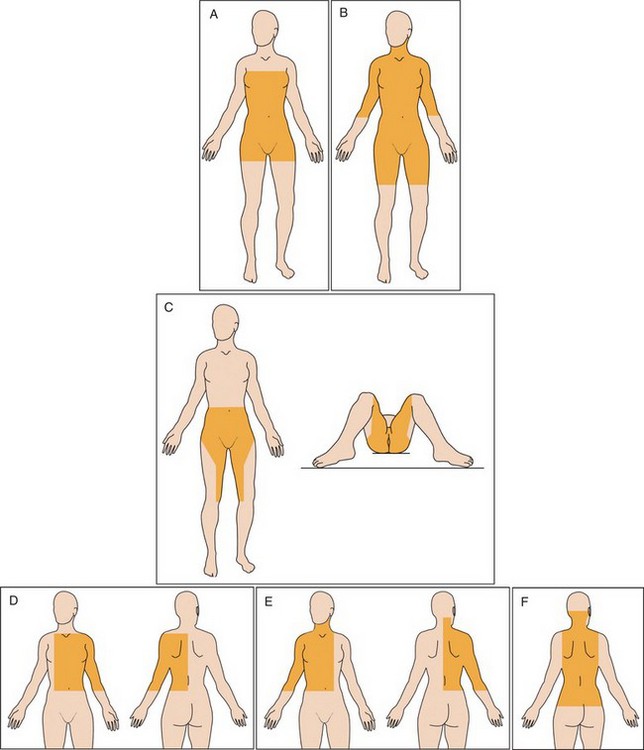

Skin Preparation: The patient may be asked to shower with a special antibacterial cleanser the night or morning before surgery to remove as many microorganisms from the skin as possible. Removing hair from the operative site may be done just before surgery, but is not generally recommended anymore (see Box 37-1). Explain the process, the area to be prepared, and timing of the prep to the patient (Figure 37-4). Although this is often done in the operating room, it may be part of your job to clip hair or use a depilatory before the patient goes to surgery. (Refer to Skill 37-2: Performing a Surgical Prep on the Companion CD-ROM). If a depilatory is used, a skin test for sensitivity should be performed many hours before its use over the surgical site.

Immediate Preoperative Care: The patient is dressed in a clean hospital gown, without underwear, for the operating room. Hair is covered with a surgical paper cap. Long hair should be dressed so that it will tangle minimally; all hairpins and barrettes must be removed. Jewelry is removed and, along with money and credit cards, is given to a significant other to keep or is secured in a valuables envelope and placed under lock and key. If a wedding band is to be worn to surgery, tape it to the finger without restricting circulation. Dentures are removed, placed in a labeled cup, and kept in a designated place according to hospital policy. Sometimes the anesthesiologist will order the dentures left in place to facilitate the administration of anesthesia by mask.

The patient’s identification bracelet is checked with the chart for accuracy to avoid any error or mix-up of patients in the operating room.

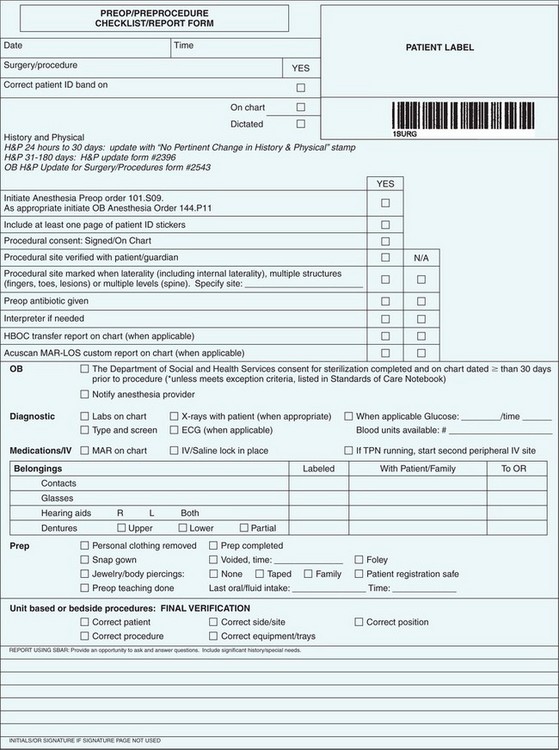

Attend to all items on the preoperative checklist that can be handled ahead of time early in the morning (Figure 37-5). This prevents hurrying and mistakes and prevents delaying the departure for the operating room while the list is completed. If the facility wants the surgical area marked before the patient leaves the room, confer with the patient and appropriately mark the site according to agency policy. Seek feedback from the patient that the site is marked properly.

Assist in transferring the patient to the stretcher when the transport person comes to take the patient to surgery. Compare the patient’s identification bracelet name and numbers with the transport request sheet. Check the chart to make certain that everything ordered has been done and make a final entry in the nurse’s notes (Figure 37-6).

Preparation of the Patient Unit: While patients are in surgery, prepare the patient unit for their return. Make the bed with fresh linen, including a drawsheet placed at shoulder height. Place an underpad at the hip area. Fan-fold the top covers to the far side of the bed or to the bottom of the bed. Have the bed in a raised position at the height of the stretcher that will return the patient and arrange furniture so that the stretcher can be pulled up alongside the bed (Figure 37-7).

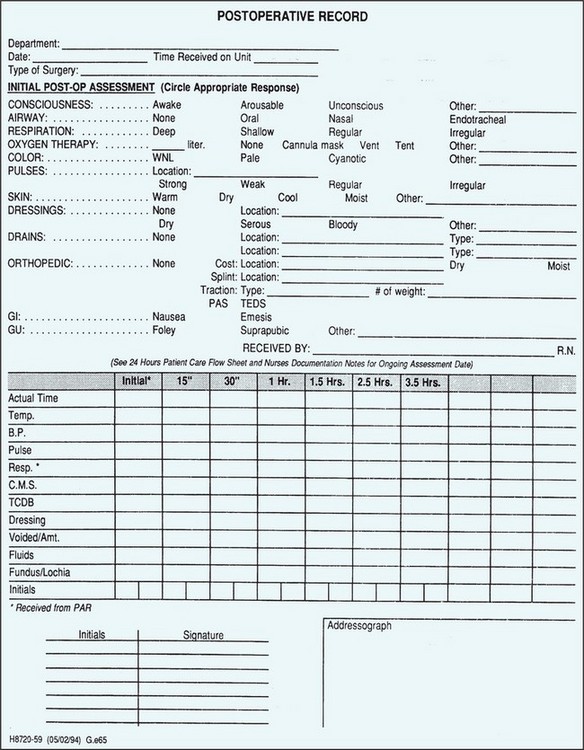

Gather an emesis basin, tissues, a frequent vital signs sheet or postoperative record, an intake and output sheet, a small towel and washcloth, and a pencil and place them on the bedside table or console (Figure 37-8). Place an IV pole at the head of the bed. Connect oxygen and suction equipment if their need is anticipated. A thermometer, sphygmomanometer and stethoscope, and pulse oximeter should be close at hand on the patient’s return to the unit. If a PCA pump, sequential pneumatic compression devices, or a passive range-of-motion machine will be needed, see that they are obtained and ready.

Evaluation

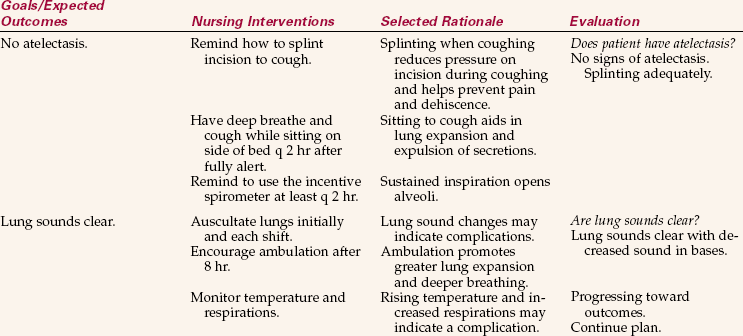

Evaluation is accomplished by determining if the expected outcomes and goals have been met. If the patient is properly prepared for surgery, is kept NPO, is reasonably calm, and is knowledgeable about the procedure and what is expected of him, then the general goals have been met. If the patient was not ready for transport at the appointed time, then you need to review your steps to see where improvement can occur. Other areas to evaluate are to assess whether the patient’s valuables were safely returned after surgery, and dentures, glasses, or hearing aid were found and reinserted. If any of these items were misplaced, then procedures need to be changed. Expected outcomes written for individual nursing diagnoses must also be addressed during evaluation (Nursing Care Plan 37-1).

INTRAOPERATIVE CARE

The patient is transported to a holding room where the circulating nurse will verify the patient’s identification and verify that all preoperative orders have been accomplished. The anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist will start an IV if one is not already in place. Any ordered preoperative medications will be administered. When the operating room (OR) is ready, the patient is transferred to the operating table (Figure 37-9, p. 765). Patient identification is verified again by the circulating nurse. The surgical consent form is checked to ensure that the patient is being prepared for the correct surgery on the correct body part. The surgical site is verified with the patient and marked, if not already done, before medications are given. The patient is positioned with padding to prevent injury to nerves and to minimize pressure over bony prominences. Safety straps are secured around the patient.

All personnel who will be entering the OR wear clean scrub outfits, hair covers, shoe covers, and sterile gowns and masks, and perform a surgical scrub prior to entering the room. Strict surgical asepsis is mandatory throughout the surgical area. The circulating nurse or scrub nurse and OR technician prepare the instruments and sterile supplies (Figure 37-10). As the patient is draped, anesthesia is begun. Further skin preparation is done at this time.

A study found that warming the patient before an operation can reduce the risk of surgical wound infection by 57%. Two different warming systems were used in the study (Melling et al., 2002).

Role of the Scrub Person and Circulating Nurse

A surgical technician or a specially trained nurse (LPN/LVN or RN) may be the scrub person. A licensed nurse usually fulfills the duties of the circulating nurse. Box 37-5 compares the functions of the two.

POSTANESTHESIA IMMEDIATE CARE

The period immediately following surgery for the patient who had general anesthesia or a major procedure performed with spinal anesthesia is a critical time and requires constant observation by specially trained nurses. The postanesthesia care recovery unit (PACU) provides care for all basic needs (Figure 37-11). The patient is positioned to prevent aspiration and promote lung expansion. The patient must be kept warm by covering with warmed blankets and should be reassured that the surgery is over. Vital signs are taken every 5 to 15 minutes until stable. Emergency equipment is on hand. The anesthesia recovery period usually takes 2 to 6 hours. The patient remains in the PACU until the vital signs are stable and the patient is awake and able to respond to stimuli. A form of the Aldrete scoring system may be used to determine readiness for transfer. Activity, respiration, circulation, consciousness, and skin color are each given a score of 1 to 3. A total score of 9 or 10 usually indicates the patient is ready for transfer. Because patients are coming out of anesthesia through the various stages and are unstable, the environment is kept as quiet as possible. Communication among the staff is kept to a minimum and is done in hushed tones. Once the patient is awake, family is sometimes allowed to visit for a few minutes so that they are assured that their loved one is alive and recovering.

Postanesthesia Care on the Surgical Floor

For many procedures, the patient may be transferred from the OR directly back to the same-day surgery unit. The nurse monitors the patient’s respiration, circulation, vital signs, neurologic status, fluid balance, wound drainage and dressings, and comfort level. When the vital signs are stable, the patient is allowed to sit up and then is ambulated. When able to ambulate unassisted, the patient may be discharged if vital signs are stable. Recovery time in the same-day surgery unit takes about 1 to 4 hours. Discharge teaching is begun before the surgery and continues once the patient is again alert. Written instructions are always sent home with the patient.

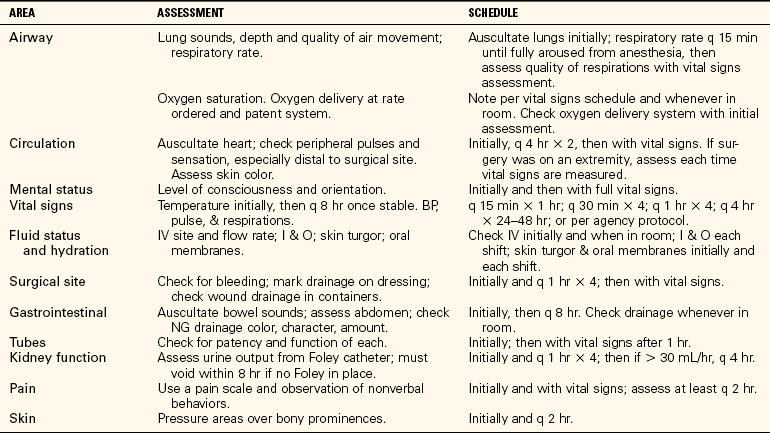

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Upon receiving the patient from the PACU nurse, checking his identity, and settling him in bed, perform an initial postoperative assessment. This provides a baseline for frequent postoperative assessments performed to prevent or quickly catch signs of complications. Initial postoperative assessment is outlined in Table 37-3. Vital signs and careful assessment are performed every 15 minutes for 1 hour, every 30 minutes for 2 hours, every hour for 4 hours, then every 4 hours until the patient is totally recovered from anesthesia and vital signs have returned to normal. Vital signs are taken more frequently if they are unstable; this is a nursing judgment.

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing diagnoses commonly used for postoperative patients who had general anesthesia are as follows:

• Pain related to disruption of tissue

• Risk for infection related to surgical wound

• Impaired gas exchange related to the effect of anesthesia on the lungs

• Ineffective airway clearance related to inability to breathe deeply and cough without discomfort

• Self-care deficit, bathing/hygiene related to decreased mobility, tubes, and dressings

• Risk for injury related to sedation, decreased level of consciousness, or excessive blood loss

• Ineffective tissue perfusion related to surgery, anesthesia, and positioning on the operating table

• Ineffective coping related to loss of body part or change in body image

For patients who have undergone spinal anesthesia, include the first two diagnoses on the above list plus the following:

Planning

The expected outcomes depend on the individual specific nursing diagnoses. General nursing goals are as follows:

• Maintain patent airway and adequate respiratory exchange.

• Maintain adequate tissue perfusion.

• Promote psychological adjustment to lifestyle or body image changes.

When planning the shift work, you must allow time for frequent postoperative assessments. Careful planning is essential to care for the early postoperative patient properly and not neglect the needs of other assigned patients.

Implementation

Protect the Patient from Injury:

Maintaining an open airway is a priority measure.: The patient must be positioned on the side or with the head turned to the side to prevent aspiration, if not contraindicated, until fully recovered, alert, and with the swallowing reflex intact.

Side rails are kept raised for safety until patients are fully recovered from anesthesia. Reassure the patient who has had spinal anesthesia that it is normal for the legs to feel numb and heavy and that feeling will soon return to normal. Sense of position will return to the legs first, then sensation to deep pressure, then voluntary movement, and finally feeling of superficial pain and temperature. A feeling of “pins and needles” in the legs is common. The patient is prone to hypotension until all effects of the spinal anesthesia are gone. The patient is observed for a spinal headache, but it is not necessary to stay totally flat for the first 12 hours because this has proven to be ineffective. If a headache develops, staying flat reduces the pain.

The surgical site is checked when the patient returns to the unit. The dressing should be dry. If it is stained, the area is outlined with pen and the time noted so that further bleeding can be assessed later. If the bleeding has saturated the dressing, reinforce with more dressing supplies; the dressing is not changed without an order to do so. The surgical site should be checked each hour for the first 4 hours, then every 2 hours if bleeding has not been occurring. Excessive bleeding is reported to the surgeon. The bed linens under the patient must be checked as well because sometimes blood runs under the dressing and pools under the patient.

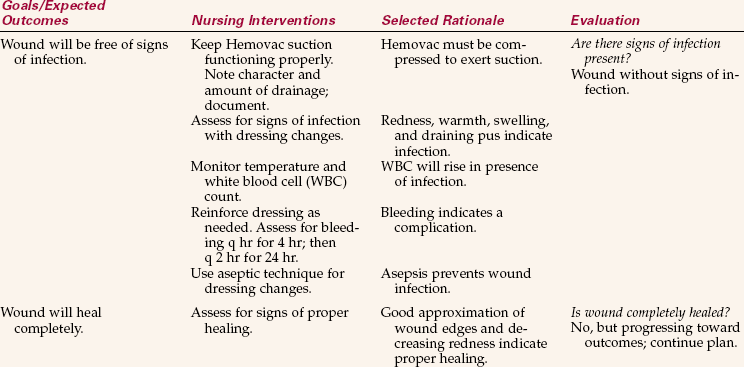

Drains are assessed for patency when the wound is checked, and drainage devices are emptied and recompressed as needed. The amount of drainage is recorded on the intake and output record (Table 37-4). The drainage devices must be positioned so that there is no pulling on the entry sites. During assessment, the tubes are checked for kinking and to ensure that the patient is not lying on them. Common types of drains left in to help remove fluid from the surgical site are Penrose, Hemovac, and Jackson-Pratt (J-P) drains, chest tubes, and a T-tube to the common bile duct.

Table 37-4

Expected Drainage from Tubes and Catheters Postoperatively

| TYPE OF DRAINAGE | AMOUNT OF DRAINAGE IN 24 HOURS |

| Urine | 500-700 mL for 1-2 days postoperatively, then 1500–2500 mL thereafter depending on intake |

| Gastric contents | Up to 1500 mL/day |

| Wound drainage | Variable with procedure and type of drain |

| T-tube/bile | Up to 500 mL |

Adapted from Lewis, S.L., Heitkemper, M.M., Dirksen, S.R., et al. (2007). Medical-Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems (7th ed., p. 393). St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby.

Promote Respiratory Function: The postoperative patient is at risk for respiratory problems from the effects of anesthesia on the lungs, from being in one position on the OR table for the duration of surgery, and from limited mobility in the immediate postoperative period. The patient may have oxygen per nasal cannula ordered for 24 hours after surgery. Some degree of atelectasis (collapse of alveoli in the lungs) exists after anesthesia. A mild hypoxia is usually present for about 48 hours after surgery. Auscultate the lungs carefully for absence of sound or crackles indicating retained secretions, assess the rate and depth of breathing, and encourage the patient to deep breathe and cough every 2 hours. This is essential to prevent pneumonia and relieve atelectasis. Hypostatic pneumonia occurs when lack of movement or of position change causes stasis of secretions, which become a breeding ground for bacteria. Coughing may be contraindicated for patients who have had hernia repair or eye, ear, or brain surgery. Check the physician’s orders.

Coughing is for the purpose of moving out secretions. If the patient cannot cough effectively, instruct him to take a deep breath and forcibly exhale with the mouth open; have him repeat the “huff” maneuver again; then ask him to take a deep breath and cough strongly as he exhales to move the secretions out of the airways. Little coughs just clear the throat. Be certain the patient turns every 2 hours as well because this changes the distribution of gas and blood flow in the lungs and helps move secretions.

Signs of complications are complaints of shortness of breath, pain on inspiration, and extreme fatigue, which is related to hypoxemia. The use of an incentive spirometer is especially helpful to prevent atelectasis and hypoventilation. The elderly patient may need extra coaching to master the technique.

A pulse oximeter may be utilized to determine blood oxygenation. Monitor the readings periodically and report arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) readings below 92% to the physician. Pulse oximetry is covered in Chapter 28.

Promote Circulation: When considerable blood is lost during surgery, transfusion may be ordered. Autologous transfusion may be done if the patient donated blood several weeks prior to surgery or if the patient’s blood was collected as it was lost. This blood is filtered and returned to the patient.

When there has been a procedure involving an extremity or the pelvic area, the distal or peripheral pulse is checked during each full assessment. Swelling at the surgical site can compress vessels and decrease blood flow distal to the area. The skin should be warm to the touch and there should be good capillary refill in the fingers or toes.

Blood pressure and pulse should be compared with preoperative values to determine significant changes. An increase in pulse may indicate that internal bleeding is occurring, but it can also signify incomplete pain control. Blood pressure falling below normal baseline level may indicate major bleeding.

The use of antiembolic (elastic) stockings increases venous return from the legs and helps prevent stasis of blood in the lower extremities (Skill 37-1). If the patient is at considerable risk of venous thrombosis (blood clot), the surgeon will order sequential pneumatic compression devices to be applied to the legs. These alternately compress and release, squeezing the vessels and propelling blood along them (Figure 37-12).

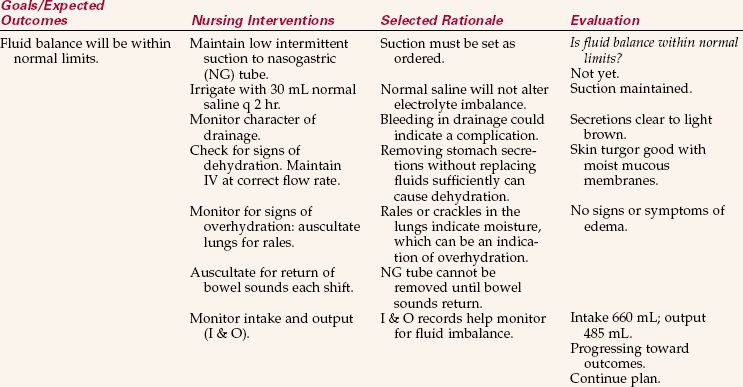

Maintain Fluid Balance: The urine output is monitored after surgery. If the patient has an indwelling catheter, the urine in the bag is observed every hour in the early postoperative period. There should be a urinometer on the drainage bag for this purpose. If the urine flow is less than 5 mL/kg/hr, it is reported to the charge nurse. If flow is less than 60 mL over a 2-hour period, the surgeon is notified. The catheter is checked to ensure that it is not kinked and that the connecting tubing is not lying beneath the patient. If no catheter is present, the patient must void within 8 hours of surgery. If the patient is unable to empty the bladder spontaneously, an order for catheterization is obtained.

The patient usually has an intravenous infusion running when he returns from surgery. Depending on the type of surgery, IV fluids may be continued for a few days or may be discontinued after the fluid has infused. Check to make certain that the fluid running is the one that the surgeon ordered. No potassium additive should be given until the urine flow is at least 5 mL/kg/hr. Potassium may cause hyperkalemia if kidney function is not adequate. The IV site is assessed for patency and lack of complications when vital signs are taken. The IV flow rate is rechecked as well. All IV fluid administered is recorded as intake on the intake and output record.

As soon as the patient is conscious and the swallowing reflex has returned, the patient may be offered a few ice chips or sips of water unless there is an order to maintain NPO status. All intake is recorded on the intake and output record. At the end of each shift, the difference between the intake and output is noted. The body will initially retain fluid due to the stress reaction from surgery. Postoperatively, the output will slowly rise until it is more than the intake; after 2 to 3 days, a balance should again occur.

Anesthesia may make the patient nauseated, and vomiting is not uncommon. The emesis basin is kept close at hand, and the patient is positioned on the side to prevent aspiration. The surgeon usually writes an order for medication in the event of excessive nausea or vomiting. It is best to medicate the patient before actual vomiting occurs. After emesis, mouth care should be provided. If vomiting is uncontrolled with medication, a nasogastric tube may have to be inserted to suction stomach contents and prevent further fluid and electrolyte loss.

Surgeons often leave in a nasogastric tube after most abdominal procedures because handling of the gastrointestinal tract, and general anesthesia, causes peristalsis to halt and secretions will not flow through the system properly. When a nasogastric tube is in place, check that the suction is set according to orders, and is working properly. Assess the amount of drainage produced every 1 to 2 hours. If the tubing is kept above the level of the stomach, drainage will occur more easily. If the drainage turns dark brown and grainy, it should be checked for blood with a special reagent. The presence of blood should be reported to the surgeon.

Promote Gastrointestinal Function: Eating is not allowed until bowel sounds have returned after surgery and general anesthesia due to the risk of development of paralytic ileus (failure of forward movement of bowel contents). Listen for bowel sounds at least once per shift. When eating is resumed, the surgeon usually orders clear liquids, followed by full liquids, then a regular diet if the preceding diets have been tolerated. After spinal anesthesia, the patient may be allowed to eat right away.

Once the patient is eating again, he should have a bowel movement within 2 to 3 days. If one does not occur, an order for a suppository may be needed to stimulate a bowel movement. Patients receiving narcotic analgesics may become constipated and require stool softeners or laxatives to produce normal bowel movements.

Promote Comfort: If the patient is complaining of pain upon return to the unit, check through the notes from the PACU and see if any pain medication was given. Note what preoperative medications were administered.

If respirations are within normal limits and there is no contraindication to doing so, medicate promptly with the ordered analgesic. If it is too soon to give more analgesia, reposition the patient, be sure the bladder is not distended and causing discomfort, check that the patient is warm enough, and use other comfort measures to relieve the pain, such as distraction and imagery. Note when analgesia is due and have it ready to administer at the appointed time.

The patient may feel cold and should be kept warm with extra blankets or warmed bath blankets applied under the top covers. Placing socks on the feet may help. Some anesthetic agents may cause tremors as they wear off. If uncontrollable shivering occurs, contact the physician for medication orders.

Dressings on extremities should be checked to be certain that they are not so tight that circulation is cut off. Check the distal pulse and skin temperature. Check with the physician or charge nurse before loosening a dressing.

Abdominal distention and considerable flatus may occur after general anesthesia because the gastrointestinal tract action ceases. This may cause discomfort. Ambulating is helpful in moving and evacuating gas. Taking only small amounts of liquid or food at a time, drinking liquids that are neither very hot nor very cold, and refraining from drinking with a straw helps keep flatus to a minimum. If permitted, the patient can try resting in a slight Trendelenburg’s position, with the legs and rectum higher than the stomach; this may assist in the evacuation of flatus. Chewing gum, if permitted, may also aid the return of proper gastrointestinal function.

Occasionally continuous hiccups will occur after surgery, making the patient quite uncomfortable. Having the patient breathe into a paper bag will often relieve the hiccups, but persistent hiccups require more vigorous treatment prescribed by the physician.

Rest and Activity: The patient needs to sleep after surgery. The room should be kept quiet and nursing activities grouped to prevent waking the patient more than necessary. Every 2 hours the patient must do the leg exercises and change position. Orders for ambulation may begin 8 hours after surgery. Raise the head of the bed first and let the body adjust to the position change. Then sit the patient on the side of the bed, allowing the legs to dangle over the side with the feet on the floor. After a few minutes, slowly assist the patient to stand. Have the patient walk around the room, or for at least a few steps. Have someone assist you if the patient is very weak. Pain medication can be timed so that it is effective but the patient is not too groggy. Emphasize to the patient that exercise is vital to prevent circulatory problems. Do not rub the legs to promote circulation. Such an action may disrupt a clot that has formed and cause an embolus (clot that travels and lodges in a vessel) to the lung, heart, or brain. Praise the patient for any efforts. Continue to ambulate on a set schedule until the patient is up and about independently.

If the patient is on bed rest, range-of-motion exercises must be performed at least four times a day. The patient may do active range of motion on most joints, but passive range of motion on joints the patient is unable to exercise must be done unless physical therapy visits have been ordered. See Chapter 18 for directions for range-of-motion exercises.

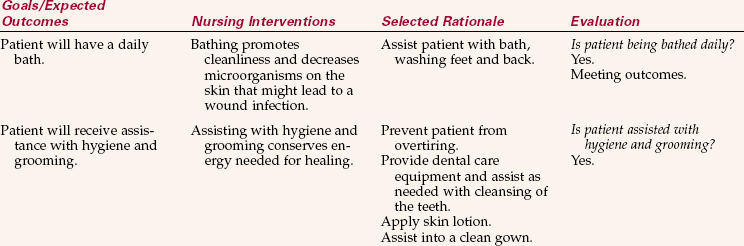

Prevent Infection: Aseptic technique must be used when caring for the postoperative patient. Good handwashing is the primary means of preventing infection. Dressing changes are performed with strict aseptic technique while the patient is in the hospital; the patient may use clean technique at home. Encouraging fluids to flush the bladder will help prevent a bladder infection for the patient who was catheterized or has an indwelling catheter. Turning, coughing, and deep breathing, plus ambulation, will assist in preventing pneumonia (inflammation and consolidation of the lung with exudate) from retained secretions and lack of movement.

The surgical wound site should be inspected each shift and assessed for signs of infection: local pain, increased tenderness, warmth, redness, or drainage of pus. The blood count is monitored for increasing leukocytes (WBCs), and the temperature is monitored for unexpected increase.

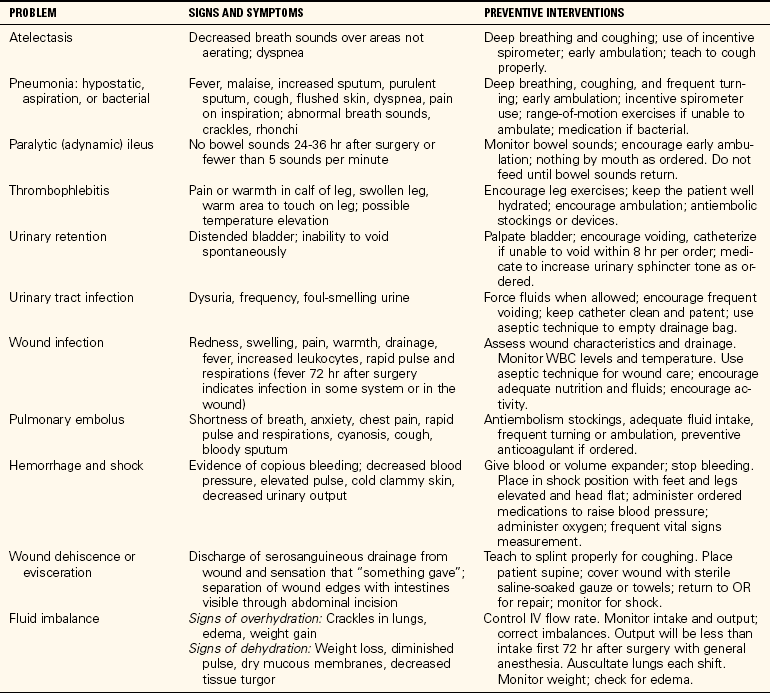

Complications of Surgery: A major nursing responsibility is continuous monitoring for signs of the various complications that may occur as a result of surgery. Table 37-5 summarizes postoperative complications and nursing actions to prevent them. Dehiscence (separation of the layers of the surgical wound) and evisceration (extrusion of the viscera through the surgical incision) may occur when the patient is coughing, particularly if the abdominal incision is not properly splinted. Research has shown that giving a bolus of IV Plasma-Lyte 148 (20 mL/kg), an isotonic electrolyte solution, prior to surgery can reduce the adverse reactions of drowsiness, headache, nausea, vomiting, and hypotension (Winslow & Jacobson, 1997).

Evaluation

Evaluation is based on whether goals and expected outcomes have been met. Evaluative statements regarding previously stated general goals might be as follows:

• Lungs clear to auscultation; respirations 18

• Pulse 82, BP 136/86, peripheral pulses present

• Pain controlled for 4 hours with analgesia; states pain medication controls pain for about 4 hours

• Incision clean, dry, and without redness

• States is glad he will not have periods of pain and malaise anymore

Each nursing care plan is evaluated on whether the individual specific outcomes have been met. Further examples of evaluation are in the nursing care plan for this chapter.

NCLEX-PN® EXAMINATION–STYLE REVIEW QUESTION

Choose the best answer(s) for each question.

1. When signing an informed surgical consent form, the patient is verifying that:

1. the correct operation is entered on the form.

2. the risks and alternatives for the surgical procedure have been explained.

3. all possible consequences of having or not having the procedure are understood.

4. the surgical procedure and its implications have been explained.

2. Your patient had an appendectomy 2 days ago. To properly auscultate for bowel sounds, you would:

1. listen in the lower right quadrant for 2 minutes.

2. listen in both lower quadrants for 2 minutes.

3. A similarity of roles for the scrub nurse and the circulating nurse is that they both:

1. set up initial sterile instruments and supplies.

2. position lights and step stools.

4. The priority responsibility of the nurse in the PACU when receiving a patient is assessment of:

5. As part of a patient’s immediate care in the PACU, the nurse would: (Select all that apply.)

1. check vital signs every 15 minutes.

2. assess adequacy of respirations

6. A patient returns to his room after surgery. When he arrives, you notice that he is still groggy from anesthesia and that he has an IV still running in one arm. As you help settle him in bed, you: (Select all that apply.)

1. assess the IV for patency and correct fluid and rate.

2. position to prevent aspiration while still groggy.

7. If your fresh postoperative patient has not voided within 8 hours of the end of surgery, you would first:

1. seek an order to catheterize the patient.

2. assist the patient to attempt to void using measures to encourage voiding.

3. allow another hour in which the patient might spontaneously void.

4. obtain catheterization equipment and bring it to the bedside.

8. Since your surgery patient returned to her room, you have assisted her to turn and encouraged her to breathe deeply, to cough, and to move her legs at least every 2 hours. By deep breathing and coughing, the patient will be less likely to develop the postoperative complication of ______________________. (Fill in the blank.)

9. The second day after surgery, the nasogastric tube is removed and an order is written for fluids as tolerated and a liquid diet. The patient is eager to try taking fluids. What would you recommend that he do?

1. Wait until his liquid diet tray arrives at mealtime.

2. Start with small sips of water at first to see if they are retained.

10. The patient has a PCA pump to be used for pain control. Should her pain not be adequately controlled with use of the pump, you would: (Select all that apply.)

1. administer an oral analgesic in addition to the pump medication.

2. seek a medication order change from the physician.

3. straighten the bed and clothing and plump the pillows.

11. On his third postoperative day, a patient states that he does not feel well and that he has a lot more pain in the incision area. You inspect the incision and notice that the lower end of it is very red. From these symptoms, you suspect that this patient has developed:

12. On the sixth postoperative day, a patient complains of malaise and pain in her right lower leg. The lower leg is warm to the touch. She has a positive Homans’ sign. You suspect that she may have ____________________. (Fill in the blank.)

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES Read each clinical scenario and discuss the questions with your classmates.

Theresa Hijazi is scheduled for surgery this morning. You are assigned two other patients to care for as well as Theresa. One of these patients is stable and will be going home. The other patient is going for a computed tomography (CT) scan at 11A.M.

Scenario B

You have prepared your 16-year-old patient for surgery, given instructions, and left her a clean gown to put on. When you return to assist in transferring him to the stretcher for the trip to the OR, you find he has put on underwear and is wearing a St. Christopher’s medal around his neck.