Chapter 26 Radiological differential diagnosis — describing a lesion

INTRODUCTION

Despite the many different conditions that can affect the jaws, they can present radiographically only as areas of relative radiolucency or radiopacity compared to the surrounding bone. Even this division based on radiodensity is not clearcut — some lesions fall into both categories, but at different stages in their development.

As a result, many of these pathological conditions resemble one another closely. This often creates considerable confusion. Fortunately, the sites where the lesions develop, how they grow and the effects they have on adjacent structures tend to follow recognizable patterns. As mentioned in Chapter 20, it is the recognition of these particular patterns that provides the key to interpretation and the formation of a radiological differential diagnosis.

A detailed description helps to identify these patterns and determine the lesion’s basic characteristics. For example, it may reveal whether the lesion is a cyst or a tumour, whether it is composed of hard or soft tissue and whether, in the case of a tumour, it is benign or malignant. The resultant list of possible diagnoses in turn often determines the patient management and mode of treatment. The final definitive diagnosis is almost always based on histological examination.

DETAILED DESCRIPTION OF A LESION

Initial mention should be made of the patient’s age and ethnic background, followed by a systematic description of the lesion which should include comments on its:

Site or anatomical position

This should be stated precisely, for example the lesion(s) could be:

• Localized to the mandible, affecting:

• Localized to the maxilla, affecting:

• Originating from a point or epicentre relative to surrounding structures, e.g.:

In the mandible, so-called odontogenic lesions develop above the inferior dental canal, while non-odontogenic lesions develop above, within or below the canal. Thus some conditions have a predilection for certain areas whilst others develop in one site only. For example, radicular dental cysts develop at the apices of non-vital teeth, while so-called fissural bone cysts develop only in the midline. The site or anatomical position of a lesion may therefore provide the initial clue as to its identity.

Size

Conventionally, the lesion is sized in one of two ways including:

• Measuring the dimensions in centimetres

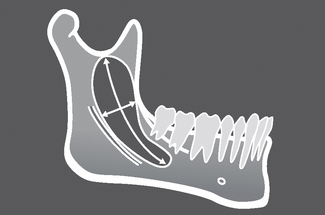

• Describing the boundaries, i.e. the lesion extends from … to … in one dimension and extends from … to … in the other dimension, as shown in Figure 26.1.

Fig. 26.1 Diagram showing the radiographic appearance of a radiolucent lesion at the angle of the mandible illustrating how to size a lesion, e.g. ‘It extends from the mesial aspect of  up to the sigmoid notch, and from the anterior border of the ramus down to the ID canal,’ or ‘It is approximately 6cm × 2cm’.

up to the sigmoid notch, and from the anterior border of the ramus down to the ID canal,’ or ‘It is approximately 6cm × 2cm’.

The size of a lesion is not a particularly helpful differentiating feature as both benign and malignant lesions may present when large or small. However, a few conditions have little or no growth potential and are therefore almost always small (e.g. 2–3 cm), such as Stafne’s idiopathic bone cavity, whilst tumours, such as ameloblastoma can grow, if untreated, to an enormous size (10 cm or more). Thus the size of a lesion, while not being specific, may still give some idea of the type of underlying condition.

Shape

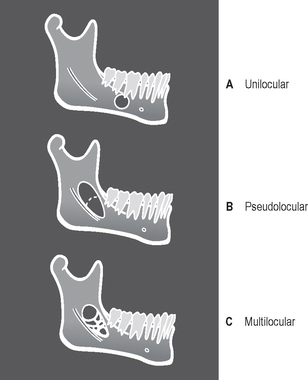

Conventionally, the shape of the lesion is described using one or more of the following terms (see Fig. 26.2):

The shape of a lesion is one of the more useful and specific characteristics that contribute to the radiological diagnosis. For example, the radicular dental cyst is round and unilocular while the giant cell lesions tend to be multilocular. An irregular shape suggests either irregular growth, such as the solitary bone cyst which typically arches up to extend between the roots of the teeth, or destruction indicating either an inflammatory or malignant lesion.

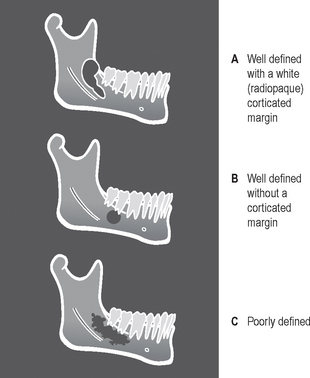

Outline / edge or periphery

The outline or periphery of lesions is described conventionally as being discrete and well defined or non-discrete and poorly defined and as having various additional characteristics (see Fig. 26.3).

Discrete or well-defined outlines, which may also be:

• Punched-out, i.e. showing no peripheral bone reaction

• Corticated, i.e. having a thick or thin surrounding radiopaque (white) cortex

• Sclerotic, i.e. having a non-uniform radiopaque boundary

• Encapsulated, i.e. surrounded by a radiolucent (black) line which may be complete or partial.

Non-discrete or poorly defined outlines, which may:

The outline or periphery provides information about the nature of the lesion, for example, whether it is benign or malignant and what the speed of growth or development appears to be. The more benign and slow growing the lesion is, the more likely it is to have a well-defined corticated outline. The malignant, more rapidly growing lesions tend to have poorly defined margins because the speed of bone destruction outstrips any bony repair.

Unfortunately, when a lesion such as a cyst becomes acutely infected, the normal outline can often be obliterated and the appearance may suggest a different, more sinister condition.

Relative radiodensity and internal structure

The radiodensity of the lesion should be assessed relative to the surrounding tissues. Radiolucent lesions are only evident within otherwise hard (radiopaque) tissues as a result of a decrease in mineralization, resorption of mineralized tissue or a decrease in thickness. As stated in Chapter 2, the amount of photoelectric absorption and hence opaque/whiteness of a structure is ∝ Z3. The atomic number (Z) of bone is approximately 12 (Z3 = 1728), whereas the atomic number of soft tissue is approximately 7 (Z3 = 343). A soft-tissue lesion replacing bone will therefore appear radiolucent.

Radiopaque lesions are evident in bone because of an increase in mineralization, increase in thickness, or superimposition on some other structure. They are also evident following calcification in soft tissues (see Ch. 28), having replaced air in the maxillary antra (see Ch. 29) or as a result of an increase in thickness of either normal or abnormal soft tissue.

Thus, relative to the surrounding tissues, the radiodensity of the lesion could be:

The relative radiodensity also helps in the differentiating process by highlighting the internal structure of partially or completely radiopaque lesions. The alternatives include:

• Fine bone trabeculae, e.g. ground glass appearance

• Thick, coarse trabeculae with enlarged trabecular spaces, e.g. honeycomb appearance

• Haphazard sclerotic bone, e.g. cottonwool patches

• Homogeneous dense cortical bone

• Discrete bony septa, which could be:

• Cementum — oval or round amorphous calcification

Effects on adjacent surrounding structures

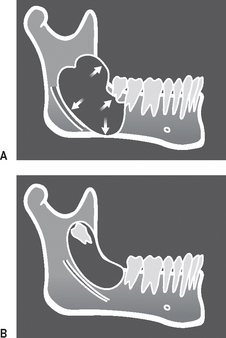

The following structures need to be checked (see Fig. 26.4):

Fig. 26.4 Diagrams showing the radiographic appearance of some of the typical effects that a lesion can have on adjacent structures. A Expansion, displacement of ID canal, tooth and bone resorption. B Tooth displacement.

The teeth — there may be evidence of:

• Resorption, which is a feature of long-standing, benign but locally aggressive lesions, chronic inflammatory lesions, and malignancy

• Disrupted development, resulting in abnormal shape and/or density

• Loss of associated lamina dura

• Increase in the width of the periodontal ligament space

Surrounding bone — there may be evidence of:

• Displacement or involvement of surrounding structures, including the:

• Increased density (sclerosis)

• Subperiosteal new bone formation

• An increase in the normal width of the inferior dental canal

• Irregular bone remodelling, resulting in an abnormal shape or unusual overall bone pattern.

Surrounding soft tissues — there may be evidence of invasion of the soft tissues producing a soft tissue mass.

Knowing what effects on adjacent surrounding structures a lesion is having, provides information about the nature of the lesion and its mode of growth. For example, the more dangerous the lesion, the more damaging and destructive its effects, and the faster its growth. Some lesions grow and expand in particular ways, such as the odontogenic keratocyst (keratocystic odontogenic tumour) which tends to infiltrate the cancellous bone and grow along the body of the mandible and produces little buccal or lingual expansion, whilst an ameloblastoma in the same site tends to expand and infiltrate in all directions.

Time present

The length of time the lesion has been present — days, weeks or years — should be determined, if possible. Unfortunately, this information is not always available. The patient may not be aware of the lesion and there may be no records of when it first became evident. If sequential radiographs are available, they can be very useful in providing information on the speed of growth, or development, of a lesion. This in turn may provide a clue about the nature of the lesion because slow-growing lesions tend to be benign, whilst fast-growing, aggressive lesions are usually malignant.

FOOTNOTE

This methodical, systematic description of the features of a lesion forms the basis of the step-by-step differential diagnostic process and is used throughout Chapters 27 and 28. As is shown later, several of the same features are shared by different conditions. Thus, no one feature alone gives enough information to provide the diagnosis. All the features should be considered carefully to determine their relevance and importance.