Chapter 20 Introduction to radiological interpretation

Interpretation of radiographs can be regarded as an unravelling process — uncovering all the information contained within the black, white and grey radiographic images. The main objectives are:

• To identify the presence or absence of disease

• To provide information on the nature and extent of the disease

To achieve these objectives and maximize the diagnostic yield, interpretation should be carried out under specified conditions, following ordered, systematic guidelines.

Unfortunately, interpretation is often limited to a cursory glance under totally inappropriate conditions. Clinicians often fall victim to the problems and pitfalls produced by spot diagnosis and tunnel vision. This is in spite of knowing that in most cases radiographs are their main diagnostic aid.

This chapter provides an introductory approach to how radiographs should be interpreted, specifying the viewing conditions required and suggesting systematic guidelines.

ESSENTIAL REQUIREMENTS FOR INTERPRETATION

The essential requirements for interpreting dental radiographs can be summarized as follows:

• Understanding the nature and limitations of the black, white and grey radiographic image

• Knowledge of what the radiographs used in dentistry should look like, so a critical assessment of individual image quality can be made

• Detailed knowledge of the range of radiographic appearances of normal anatomical structures

• Detailed knowledge of the radiographic appearances of the pathological conditions affecting the head and neck

• A systematic approach to viewing the entire radiograph and to viewing and describing specific lesions

Optimum viewing conditions

For film-captured images these include:

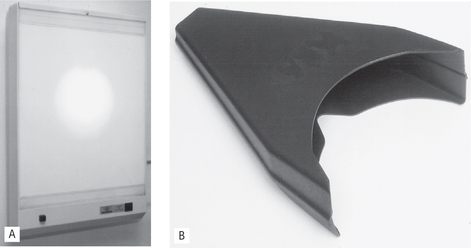

• An even, uniform, bright light viewing screen (preferably of variable intensity to allow viewing of films of different densities) (see Fig. 20.1)

• A quiet, darkened viewing room

• The area around the radiograph should be masked by a dark surround so that light passes only through the film

• Use of a magnifying glass to allow fine detail to be seen more clearly on intra-oral films

Fig. 20.1A Wardray viewing box incorporating an additional central bright-light source for viewing over-exposed dark films. B The SDI X-ray reader — an extraneous light excluding intraoral film viewer with built-in magnification.

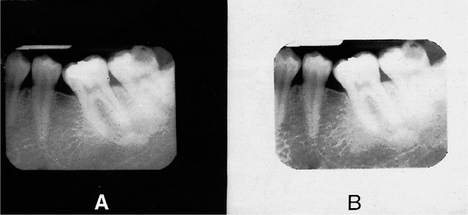

These ideal viewing conditions give the observer the best chance of perceiving all the detail contained within the radiographic image. With many simultaneous external stimuli, such as extraneous light and inadequate viewing conditions, the amount of information obtained from the radiograph is reduced (see Fig. 20.2). Film-captured radiographs should be viewed once they have dried as films still wet from processing may show some distortion of the image.

Fig. 20.2 The effect of different viewing conditions on the same periapical film. A With a black surround. B With a white surround. Note the increased detail visible in A, particularly around the molar teeth.

Digital images should be viewed on bright, high-resolution monitors in subdued lighting.

The nature and limitations of different radiographic images

The importance of understanding the nature of different types of radiographic images — film-captured or digital (depending on the type of image receptor used) and their specific limitations was explained in Chapter 1. How the visual images are created by processing — chemical or computer was explained in Chapter 7. Revision of both of these chapters is recommended. To reiterate, the final image whether captured on film or digitally is ‘a two-dimensional picture of three-dimensional structures superimposed on one another and represented as a variety of black, white and grey shadows’ — a shadowgraph.

Critical assessment of image quality

To be able to assess and interpret any radiographic image correctly, clinicians have to know what that image should look like, how it was captured, and which structures should be shown. It is for this reason that the chapters on radiography included:

1. WHY each projection was taken

2. HOW the projections were taken using different image receptors

With this practical knowledge of radiography, clinicians are in a position to make an overall critical assessment of individual film-captured and digital images.

Film-captured images

The practical factors that can influence film quality were discussed in Chapter 18, and included:

A critical assessment of radiographs can be made by combining these factors and by asking a series of questions about the final image. These questions relate to:

Here are some typical examples.

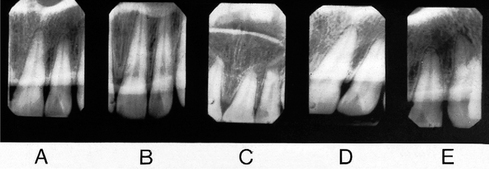

Technique (see Fig. 20.3)

• Which technique has been used?

• How were the patient, film and X-ray tubehead positioned?

• Is this a good example of this particular radiographic projection?

• How much distortion is present?

• Is the image foreshortened or elongated?

• Is there any rotation or asymmetry?

• How good are the image resolution and sharpness?

• Which artefactual shadows are present?

• How do these technique variables alter the final radiographic image?

Fig. 20.3 Examples of how variations in radiographic technique can alter the images—film or digital—produced of the same object. A Correct projection. B Incorrect vertical angulation producing an elongated image. C Incorrect vertical angulation producing a foreshortened image. D and E Incorrect horizontal angulations producing distorted images.

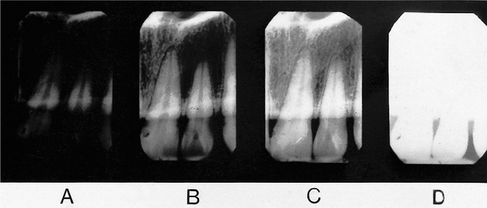

Exposure factors (see Fig. 20.4)

Digitally-captured images

The practical factors that can effect digitally-captured images, how the images are created and how they can be altered using computer soft-ware were discussed in Chapter 7 and included:

• The image receptor — solid-state or photostimulable phosphor plate

As with film-captured images a critical assessment of digital images can be made by combining these factors and by asking a series of questions about the final image. These questions relate to:

Technique

• Which technique has been used?

• How were the patient, digital receptor and X-ray tubehead positioned?

• Is this a good example of this particular radiographic projection?

• How much distortion is present?

• Has the whole area of interest been included?

• Is the image foreshortened or elongated?

• Is there any rotation or asymmetry?

• How good are the image resolution and sharpness?

• Which artefactual shadows are present?

• How do these technique variables alter the final radiographic image?

Note: These technique questions are almost identical to those relating to film-captured images. Image quality is totally dependent on high quality practical radiography whatever image receptor is chosen.

Image processing

With experience, this critical assessment of image quality is not a lengthy procedure but it is never one that should be overlooked. A poor radiographic image is a poor diagnostic aid and sometimes may be of no diagnostic value at all. Clinicians used to using film-captured images who decide to ‘go digital’ should take time to understand the nature of the digital image and the effect on the image of using powerful computer software manipulation.

Detailed knowledge of normal anatomy

A detailed knowledge of the radiographic appearances of normal anatomical structures is necessary if clinicians are to be able to recognize the abnormal appearances of the many diseases that affect the jaws.

Not only is a comprehensive knowledge of hard and soft tissue anatomy required but also a knowledge of:

• The type of radiograph being interpreted (e.g. conventional radiograph or tomograph)

• The position of the patient, image receptor and X-ray tubehead.

Only with all this information can clinicians appreciate how the various normal anatomical structures, through which the X-ray beam has passed, will appear on any particular radiograph.

Detailed knowledge of pathological conditions

Radiological interpretation depends on recognition of the typical patterns and appearances of different diseases. The more important appearances are described in Chapters 21–33 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33.

Systematic approach

A systematic approach to viewing radiographs is necessary to ensure that no relevant information is missed. This systematic approach should apply to:

The entire radiograph

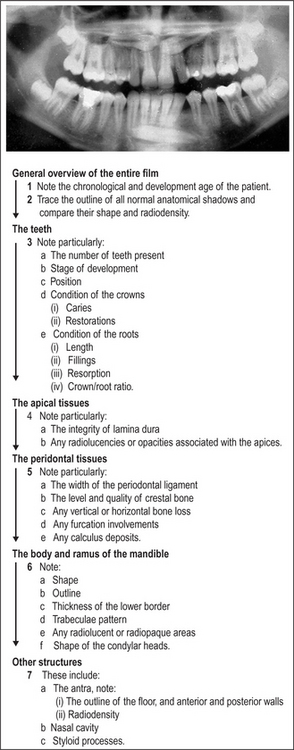

Any systematic approach will suffice as long as it is logical, ordered and thorough. Several suggested sequences are described in later chapters. By way of an example, a suggested systematic approach to the overall interpretation of dental panoramic radiographs (see Ch. 17) is shown in Figure 20.5.

Fig. 20.5 An example of a dental panoramic radiograph and a suggested systematic sequence for viewing this type of film.

This type of ordered sequential viewing of radiographs requires discipline on the part of the observer. It is easy to be sidetracked by noticing something unusual or abnormal, thus forgetting the remainder of the radiograph.

Specific lesions

A systematic description of a lesion should include its:

Making a radiological differential diagnosis depends on this systematic approach. It is described in detail and expanded on later (see Ch. 26).

Comparison with previous films

The availability of previous films for comparative purposes is an invaluable aid to radiographic interpretation. The presence, extent and features of lesions can be compared to ascertain the speed of development and growth, or the degree of healing.

Note: Care must be taken that views used for comparison have been taken with a comparable technique and are of comparable density.

Conclusion

Successful interpretation of radiographs, no matter what the quality, relies ultimately on clinicians understanding the radiographic image, being able to recognize the range of normal appearances as well as knowing the salient features of relevant pathological conditions.

The following chapters are designed to emphasize these requirements and to reinforce the basic approach to interpretation outlined earlier.