Acute care

Patients who are NBM and receive only standard IV fluids for more than 7 days are at nutritional risk. In addition, nutritional problems commonly occur in conditions such as HIV infection, cancer, eating disorders, GI disease, critical illness, malabsorption problems, metabolic diseases, obesity, renal disease and diseases of the liver, pancreas and gallbladder, and following major surgical procedures.

Table 36-11 gives an overview of the immune system and how it relates to nutrient intake. The normal course of dietary advancement and a basic description of each type of therapeutic diet for hospitalised patients are summarised in Box 36-10.

TABLE 36-11 NUTRITION AND THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

| IMMUNE/PHYSIOLOGICAL COMPONENT | MALNUTRITION EFFECT | VITAL NUTRIENT |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Decreased amount | Protein, vitamins A, C, B12, B6, folic acid, thiamine, biotin, riboflavin, niacin |

| Gastrointestinal (GI) tract | Translocation of bacteria to systemic bodily areas | Arginine, glutamine, omega-3 fatty acids |

| Granulocytes and macrocytes | Longer time for phagocytosis kill time and lymphocyte activation | Protein, vitamins A, C, B12, B6, folic acid, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, zinc, iron |

| Mucus | Flat microvilli in GI tract, decreased antibody secretion | Vitamins B12, B6, C, biotin |

| Skin | Integrity compromised, density reduced, wound healing slowed | Protein, vitamins A, B12, C, niacin, copper, zinc |

| T-lymphocytes | Depressed T-cell distribution | Protein, arginine, iron, zinc, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins A, B12, B6, folic acid, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid |

Modified from Grodner M and others 2007 Foundations and clinical applications of nutrition: a nursing approach, ed 4. St Louis, Mosby.

BOX 36-10 DIET PROGRESSION OF HOSPITALISED CLIENTS

CLEAR LIQUID

Broth, bouillon, coffee, tea, carbonated drinks, clear fruit juices, gelatin, ice blocks.

FULL LIQUID

As above with addition of smooth-textured dairy products, custards, refined cooked cereals, vegetable juice, pureed vegetables, all fruit juices.

PUREED

All of above with addition of scrambled eggs, pureed meats, vegetables, fruits, mashed potatoes and gravy.

MECHANICAL SOFT

All of above with addition of minced or finely diced meats, flaked fish, cottage cheese, cheese, rice, potatoes, pancakes, light breads, cooked vegetables, cooked or canned fruits, bananas, soups, peanut butter.

SOFT

All of above with addition of moist tender meat, poultry, fish, soft casseroles, lettuce, tomatoes, soft fresh fruit, cake, biscuits without nuts or coconut.

From Grodner M and others 2007 Foundations and clinical applications of nutrition: a nursing approach, ed 4. St Louis, Mosby.

ENTERAL TUBE FEEDING

Enteral nutrition (EN) refers to nutrients given via the GI tract. EN is the preferred method of meeting nutritional needs if the patient’s GI tract is functioning because it provides physiological, safe and economical nutrition support. Enterally fed patients receive formula via nasogastric, jejunal or gastric tubes. Gastric feedings may be given to patients with a low risk of aspiration; however, if there is a risk of aspiration, jejunal feeding is preferred. Box 36-11 lists indications for tube feeding. Enteral tube feedings are easily given in the home setting by either the nurse or the family. Regardless of the setting, the principles in Skills 36-1, 36-2 and 36-3 for enteral feedings must be maintained.

SKILL 36-1 Inserting a small-bore nasoenteric tube for enteral feedings

DELEGATION CONSIDERATIONS

This task requires the problem-solving and knowledge-application skills of professional nurses. For this reason, delegation of this task to nurse assistants is inappropriate.

EQUIPMENT

• Nasogastric or nasointestinal tube (8–12 Fr) with guide wire or stylet

• 60 mL or larger Luer-lock or catheter-tip syringe

• Hypoallergenic tape and tincture of benzoin

• Suction equipment in case of aspiration

| STEPS | RATIONALE | |

|---|---|---|

| Identifying patients who need tube feedings before they become nutritionally depleted may help to prevent complications related to malnutrition. | ||

| Evaluates nares for patency. | ||

| Nares may be obstructed. Assessment determines which naris to use. | ||

| Identifies ability to swallow and risk of aspiration. | ||

| Nurse may seek doctor’s order to change route of nutritional support or to place tube past the stomach into the intestine with increased risk of aspiration. | ||

| Procedure and tube feedings require a doctor’s order. | ||

| Reduces transfer of microorganisms. | ||

| Reduces anxiety and helps patient to assist in insertion. | ||

| Allows easier manipulation of tube. Fowler’s position reduces risk of aspiration and promotes effective swallowing. | ||

| Prevents soiling of gown. Insertion of tube may produce tears. | ||

| Length approximates distance from nose to stomach in 98% of patients. For duodenal or jejunal placement, an additional 20-30 cm is required. | ||

| Tubes will become stiff and inflexible, causing trauma to mucous membranes. | ||

| Aids in guide wire or stylet insertion. | ||

| Promotes smooth passage of tube into GI tract. Improperly positioned stylet can induce serious trauma. | ||

| Reduces transmission of microorganisms. | ||

| Activates lubricant to facilitate passage of tube into naris to GI tract. | ||

| Natural contours facilitate passage of tube into GI tract; reduces gagging by patient. | ||

| Closes off glottis and reduces risk of tube entering trachea. | ||

| Critical decision point: Encourage patient to swallow by giving small sips of water or ice chips when possible. Advance tube as patient swallows. Rotate tube 180 degrees while inserting. | ||

| Helps facilitate passage of tube and alleviates patient’s fears during the procedure. | ||

| Reduces discomfort and trauma to patient. | ||

| Tube may be coiled, kinked or entering trachea. | ||

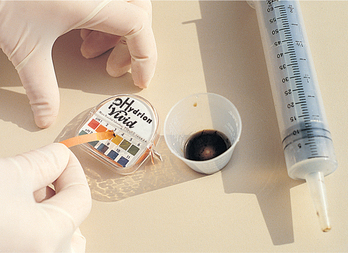

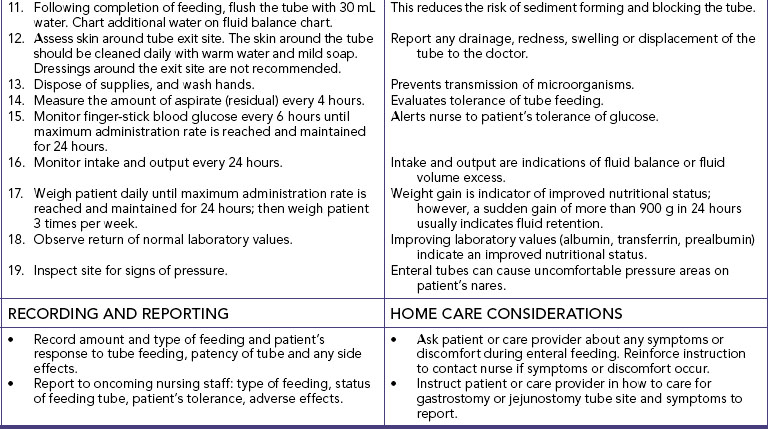

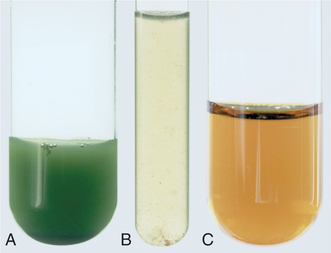

| Gastric contents are usually cloudy and grassy green or tan to off-white; in contrast, intestinal fluid is usually deep golden yellow and is more clear than gastric fluid (see Figure 36-11). Fasting gastric pH is usually in a range of 1-4; only infrequently is it greater than 6. In contrast, intestinal sites usually have a pH of 7 or greater. | ||

| Critical decision point: Auscultation is no longer considered a reliable method for verification of tube placement because a tube inadvertently placed in the lungs, pharynx or oesophagus can transmit a sound similar to that of air entering the stomach (Tho and others, 2011). | ||

| Helps tape adhere better. Protects skin. | ||

| A properly secured tube allows the patient more mobility and prevents trauma to nasal mucosa. | ||

| Securing tape to nares prevents tissue necrosis. | ||

| Reduces traction on the naris if tube moves. | ||

| Promotes passage of the tube into the small intestine (duodenum or jejunum). | ||

| Critical decision point: Leave guide wire or stylet in place until correct position is ensured by X-ray. Never attempt to reinsert partially or fully removed guide wire or stylet while feeding tube is in place. | ||

| Placement of tube is verified by X-ray examination. | ||

|

23. Put on gloves, and administer oral hygiene (see Chapter 34). Clean tubing at nostril. |

Promotes patient comfort and integrity of oral mucous membranes. | |

| Reduces transmission of microorganisms. | ||

| If insertion was difficult, irritation of naris or oropharynx may have occurred. | ||

| Evaluates patient’s level of comfort. | ||

| Malposition of the tube may cause these symptoms. | ||

SKILL 36-2 Administering enteral feedings via nasoenteric tubes

DELEGATION CONSIDERATIONS

This task requires the problem-solving and knowledge-application skills of professional nurses. For this reason, delegation of this task to nurse assistants is inappropriate.

EQUIPMENT

• Disposable feeding bag and tubing or ready-to-hang system

• 30 mL or larger Luer-lock or catheter-tip syringe

• Infusion pump (required for intestinal feedings): use pump designed for tube feedings

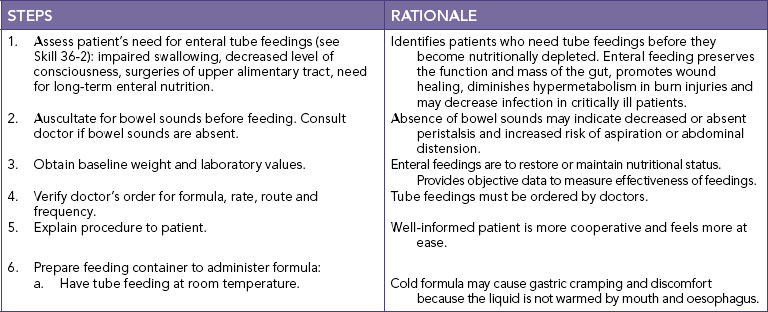

| STEPS | RATIONALE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Identify patients who need tube feedings before they become nutritionally depleted. | |||

| Absent bowel sounds may indicate decreased ability of GI tract to digest or absorb nutrients. | |||

| Enteral feedings are to restore or maintain a patient’s nutritional status. Provides objective data to measure effectiveness of feedings. | |||

| Tube feedings, laboratory tests and bedside tests must be ordered by doctor. | |||

| Well-informed patient is more cooperative and at ease. | |||

| Reduces transmission of microorganisms. | |||

| Cold formula may cause gastric cramping and discomfort because the liquid is not warmed by mouth and oesophagus. | |||

| Tubing must be free of contamination to prevent bacterial growth. | |||

| Filling the tubing with formula prevents excess air from entering GI tract. | |||

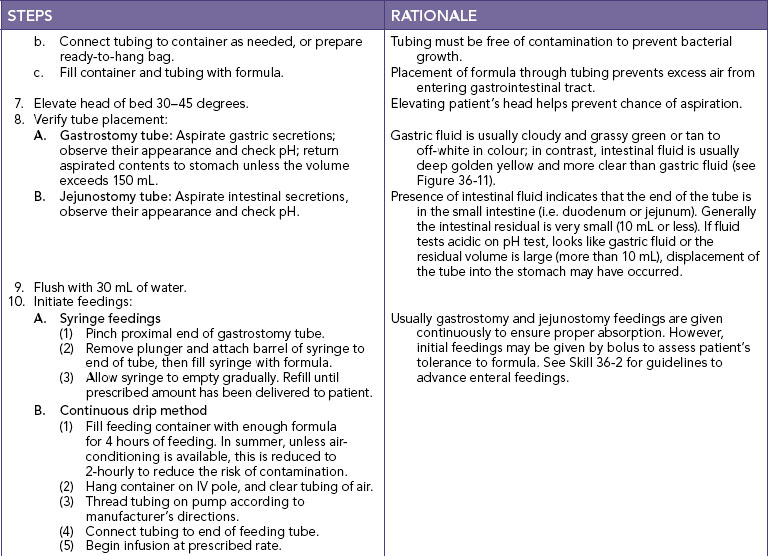

| Elevated head helps prevent aspiration. | |||

| Presence of gastric secretions indicates that the distal end of the tube is in the stomach. Residual volume indicates whether gastric emptying is delayed. Delayed gastric emptying may be reflected by 150 mL or more remaining in the patient’s stomach. | |||

| Fasting gastric pH is usually equal to or less than 4; it is only infrequently greater than 6; in contrast, intestinal aspirates usually have a pH equal to or greater than 7. | |||

| Gastric fluid is usually cloudy and grassy green or tan to off-white in colour; in contrast, intestinal fluid is usually deep golden yellow and is more clear than gastric contents (see Figure 36-11). | |||

| An aspirate with a low pH and a typical gastric fluid colour indicates a high probability of gastric placement; in contrast, a golden-coloured aspirate with a high pH indicates a high probability of intestinal placement. | |||

| Critical decision point: Auscultation is no longer considered a reliable method for verification of placement of tube because air in tube inadvertently placed in lungs, pharynx or oesophagus can transmit sound similar to that of air entering stomach. | |||

| Prevents air from entering patient’s stomach. | |||

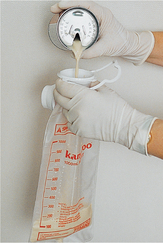

| Gradual emptying of tube feeding by gravity from syringe or feeding bag reduces risk of abdominal discomfort, vomiting or diarrhoea induced by bolus or too-rapid infusion of tube feedings. | |||

| Continuous feeding method is designed to deliver prescribed hourly rate of feeding. This method reduces risk of abdominal discomfort. Patients who receive continuous drip feedings should have residuals checked every 4 h and tube placement verified. | |||

| Tube feedings should be advanced gradually to prevent diarrhoea and gastric intolerance to formula. | |||

| Reduces the risk of sediment forming and blocking the tubing. | |||

| Prevents air from entering stomach between feedings. | |||

| Provides patient with source of water to help maintain fluid and electrolyte balance. | |||

| Rinsing bag and tubing with warm water clears old tube feedings and reduces bacterial growth. | |||

| Evaluates tolerance of tube feeding. | |||

| Alerts nurse to patient’s tolerance of glucose. | |||

| Intake and output are indications of fluid balance or fluid volume excess or deficit. | |||

| Weight gain is indicator of improved nutritional status; however, sudden gain of more than 900 g in 24 hours usually indicates fluid retention. | |||

| Improving laboratory values (e.g. albumin, transferrin and prealbumin) indicate an improved nutritional status. | |||

| RECORDING AND REPORTING | HOME CARE CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|

SKILL 36-3 Administering enteral feedings via gastrostomy or jejunostomy tube

Tube feedings are typically started at full strength at slow rates of 20–50 mL/h. The hourly rate is increased by 25 mL increments every 12–24 hours if no signs of intolerance appear (nausea, cramping, vomiting, diarrhoea).

Studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect of enteral feedings compared with parenteral nutrition. Feeding by the enteral route may reduce sepsis, blunt the hypermetabolic response to trauma and maintain intestinal structure and function (Sudakin, 2006). EN has been used successfully within 24–48 hours after surgery or trauma to provide fluids, electrolytes and nutritional support. Gastric ileus may prevent nasogastric feedings, while nasointestinal or jejunal tubes allow successful postpyloric feeding where formula is placed directly into the small intestine or jejunum or beyond the pyloric sphincter of the stomach (Sudakin, 2006).

Aspiration of enteral formula into the lungs irritates the bronchial mucosa, resulting in decreased blood supply to affected pulmonary tissue. This then leads to necrotising infection, pneumonia and potential abscess formation. The high glucose content serves as a bacterial medium for growth, promoting infection. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is also an outcome frequently associated with aspiration of gastric contents (Baskin, 2006).

EN formulas vary in composition and nutrient density. General categories of EN formulas include standard whole-protein formulas, hydrolysed protein (elemental or peptide) and disease-specific formulas or crystalline amino acids (see Table 36-12).

TABLE 36-12 CLASSIFICATION OF ENTERAL NUTRITION PRODUCTS

| CLASSIFICATION | FORMULA CHARACTERISTICS |

|---|---|

| INTACT PROTEIN | |

| Blenderised | Isotonic; nutritionally complete; contain fibre; lactose-containing and lactose-free |

| Low-residue: | |

| Standard protein | Isotonic; nutritionally complete; lactose-free |

| Intermediate–high protein | Isotonic; nutritionally complete; lactose-free |

| Concentrated | Kilojoule-dense; lactose-free; nutritionally complete; hyperosmolar |

| Fibre-supplemented | Isotonic; nutritionally complete; lactose-free; fibre ranges from 5 to 14.4 g/L; standard to intermediate protein |

| Disease-specific: | |

| Renal | Low and standard protein; low mineral, vitamin A and vitamin D content; lactose-free; kilojoule-dense; hyperosmolar |

| Glucose-intolerant | Low CHO, high fat; lactose-free; isotonic; contain fibre; nutritionally complete |

| Pulmonary | Low CHO, high fat; lactose free; nutritionally complete; hyperosmolar; kilojoule-dense |

| Trauma/s tress | High protein; isotonic to hyperosmolar; lactose-free; nutritionally complete; some contain fibre, hydrolysed protein, supplemental amino acids (branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), arginine, glutamine) and beta-carotene; low to high fat |

| HYDROLYSED PROTEIN | |

| Very low fat | Nutritionally complete, lactose-free, less than 10% of the energy from fat, hyperosmolar, vary in peptide length, contain amino acids |

| Low fat | Nutritionally complete, lactose-free, 11–30% of the energy from fat, hyperosmolar, vary in peptide length, contain amino acids |

| Moderate fat | Nutritionally complete, lactose-free, 30–35% of the energy from fat (high in medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs)); hyperosmolar, vary in peptide length, contain amino acids |

| Disease-specific: trauma | Nutritionally complete, lactose-free, intermediate to high protein content, 25–35% of the energy from fat (high in MCTs), vary in peptide length, contain amino acids, may contain supplemental arginine and beta-carotene |

| Crystalline amino acids | Nutritionally complete, lactose-free, low fat (1–3% of the total energy), low to standard protein content, hyperosmolar |

| Disease specific: | High BCAAs, nutritionally incomplete, lactose-free, low to moderate fat |

| Hepatic failure | Essential amino acids plus histidine, nutritionally incomplete, lactose-free, hyperosmolar, low fat |

| Renal failure | Essential and non-essential amino acids, nutritionally incomplete but contain water-soluble vitamins, hyperosmolar, lactose-free, low fat |

Standard formulas are suitable for patients who do not have altered digestion or absorption; elemental and peptide formulas are used for patients who have impaired digestion or absorption; and disease-specific formulas have modifications in the content of specific nutrients or in caloric density. Nearly all tube-feeding formulas are lactose-free. Specialty enteral products tend to be very costly, and their use is generally reserved for specific indications (Sudakin, 2006). Research is examining nutrients such as glutamine, arginine, nucleotides, and omega-3 fatty acids for enteral formulas.

ENTERAL ACCESS TUBES

When the patient is unable to ingest food but is still able to digest and absorb nutrients, enteral tube feeding is indicated. Feeding tubes can be inserted through the nose (nasogastric or nasointestinal), surgically (gastrostomy or jejunostomy) or endoscopically (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) or jejunostomy (PEJ)). If enteral therapy is for less than 4 weeks in total, nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding tubes may be used. Surgical or endoscopically placed tubes are preferred for long-term feeding (more than 4 weeks) to reduce the discomfort of a nasal tube and to provide a more secure, reliable access. Patients with gastroparesis (decreased or absent innervation to the stomach that results in delayed gastric emptying) or oesophageal reflux, at risk of aspiration or with a history of aspiration pneumonia require placement of tubes beyond the stomach into the intestine (Baskin, 2006).

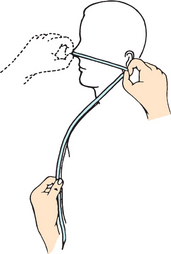

Nursing research has investigated the problems associated with nasoenteric tube placement, type of feeding instilled, rate of feeding and complications associated with tube feeding. Small-bore feeding tubes create less discomfort for the patient and are currently most often used (Figure 36-10). For the adult, most of these tubes are 8–12 French gauge (Fr) and 90–110 cm long. A stylet is often used during insertion of a small-bore tube to stiffen it. The stylet is removed when the correct position of the feeding tube is confirmed. Skills 36-1, 36-2 and 36-3 describe the procedures for inserting a small-bore nasoenteric tube and initiating enteral feedings.

FIGURE 36-10 Enteral tubes, small bore.

From Potter PA, Perry Ag 2013 Fundamentals of nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby.

Upon insertion, the placement of small-bore feeding tubes is verified by X-ray examination. The tube should then be marked where it exits the nose and taped securely. Historically, feeding-tube placement was checked by injecting air through the tube while auscultating the stomach for a gurgling or bubbling sound, or asking the patient to speak (Tho and others, 2011). These methods have a high degree of inaccuracy. At present, the most reliable method is radiographical verification, which is cost-prohibitive for ongoing placement verification. Measurement of the pH of secretions withdrawn from the feeding tube may help to differentiate the location of the tube. For accurate pH measurements, 30 mL of air is injected into the tube before measurement to flush out formula, medications, flush solutions or other substances (Turgay and Khorsid, 2010). Addition of blue food colouring to enteral formula (0.2 mL/250 mL) assists with the detection of formula aspirated into the lung, presumably by staining the tracheobronchial secretions. However, the absence of blue-stained tracheobronchial secretions does not rule out pulmonary aspiration (Tho and others, 2011). Another method sometimes advocated for detecting pulmonary aspiration of enteral formula is testing the tracheobronchial secretions for the presence of glucose (using glucose reagent strips) (Baskin, 2006).

Checking samples of fluid withdrawn from newly inserted feeding tubes for acidic (gastric) or alkaline (intestinal) values prior to use and before intermittent feedings is perhaps the most sensitive bedside indicator of tube placement (Turgay and Khorsid, 2010). X-ray verification remains the ‘gold standard’. Concurrent use of acid-inhibitor medications alters gastric pH; however, in patients who have fasted for at least 4 hours, gastric pH continues to be ≤4 in slightly over half of cases. When acid inhibitors are used, fasting gastric pH is ≤6 in about three-quarters of the cases (Tho and others, 2011). Acid inhibitors have no effect on intestinal pH, which is usually ≥7. For a continuously tube-fed patient, gastric pH is expected to be higher because most enteral formulas have pH values close to 6. Thus, although pH is a helpful indicator of tube location, additional markers are needed to help differentiate between gastric and intestinal fluids.

Major complications of enteral nutrition are outlined in Table 36-13. Of special note, severely malnourished patients are at risk of electrolyte disturbances from refeeding syndrome, as ions such as potassium, magnesium and phosphate move intracellularly during enteral or parenteral nutrition therapy.

TABLE 36-13 ENTERAL TUBE FEEDING COMPLICATIONS

| PROBLEM | POSSIBLE CAUSE | INTERVENTION |

|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary aspiration | ||

| Diarrhoea |

Deliver formula continuously, lower rate, dilute or change to isotonic EN Liquid medications are often sweetened with sorbitol, consider as possible cause Albumin 25 g/L lessens oncotic pressure equilibrium Antibiotics may destroy normal intestinal flora; doctor may change medication; treat symptoms with Lomotil, Kaopectate Do not hang formula longer than 4–8 hours in bag, wash bag out well when refilling, change tube feeding bags every 24 hours and use aseptic practices Check for pancreatic insufficiency, use low-fat, lactose-free formula and continuous feedings. |

|

| Constipation |

Select a formula containing fibre Add water as needed as flushes* Evaluate side effects; suggest stool softener or bulk-forming laxative Monitor patient’s mobility; collaborate with doctor for activity order or physiotherapy |

|

| Tube occlusion |

Irrigate with 20 mL water before and after each medication per tube* Dilute crushed medications if not liquid Avoid crushed medications, if liquid available Shake cans well before administering (read label) Read pharmacological information on compatibility of drugs and formula |

|

| Tube displacement | ||

| Abdominal cramping, nausea/vomiting | ||

| Delayed gastric emptying | ||

| Serum electrolyte imbalance | ||

| Increased respiratory quotient | Overfeeding of carbohydrates | Balance kilojoule needs provided from fat, protein and carbohydrate with greater proportion of fat in formula (to decrease CO2 production) |

| Fluid overload | ||

| Hyperosmolar dehydration | Hypertonic formula with insufficient free water | Slow rate of delivery, dilute or change to isotonic formula |

*Check first for fluid-restricted conditions that would affect volume of water given.

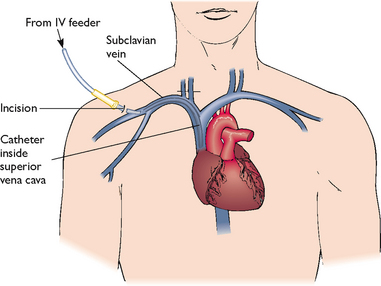

PARENTERAL NUTRITION

Parenteral nutrition (PN) is a form of specialised nutrition support in which nutrients are provided intravenously. Safe administration of this form of nutrition depends on appropriate assessment of nutrition needs, meticulous management of the central venous catheter (CVC) and careful monitoring to prevent or treat metabolic complications. PN is administered in a variety of settings, including the patient’s home. Regardless of the setting, the nurse adheres to the same principles of asepsis and infusion management to ensure safe nutrition support.

FIGURE 36-11 Gastric contents: A, Stomach. B, Stomach. C, Intestinal.

Courtesy Dr Norma Metheny, St Louis University School of Nursing.

Patients who are unable to digest or absorb enteral nutrition benefit from PN. Patients in highly stressed physiological states such as sepsis, head injury or burns are candidates for PN therapy. Box 36-11 outlines indications for PN.

Throughout PN therapy, clinical and laboratory monitoring by a multidisciplinary team is required (Table 36-14). The need for continued PN is constantly re-evaluated. The goal to move towards use of the GI tract is constant (Sudakin, 2006). Disuse of the GI tract has been associated with villus atrophy and generalised cell shrinkage. Translocation of bacteria from the local gut to systemic regions has been noted in relation to GI cell shrinkage, resulting in Gram-negative septicaemia (Baskin, 2006).

TABLE 36-14 MONITORING PARENTERAL NUTRITION (PN)*

| PARAMETER | BASELINE | ROUTINE |

|---|---|---|

| Weight | Daily | Daily |

| Glucose (bedside) | Every 6 hours | Every 6 hours |

| Vital signs/temperature | Once a shift when necessary (prn) | Once a shift/prn |

| Intake/output | Daily | Daily |

| Electrolytes | Daily first 3 days | Biweekly |

| Creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) | Baseline | Biweekly |

| Albumin, prealbumin, transferrin | Baseline | Weekly |

| Cholesterol | Baseline | As ordered |

| Triglycerides | Baseline | As ordered |

| Liver enzymes (LFTs) | Baseline | Weekly |

| Full blood count (FBC) | Baseline | Weekly |

| Prothrombin time (PT)/partial thromboplastin time (PTT)† | Baseline | Weekly |

| Platelets | Baseline | As ordered |

| Nitrogen balance (24-hour UUN) | 1–2 days after PN started | Weekly |

| Serum trace minerals and vitamins | Baseline | As ordered |

| Estimate energy requirements | Baseline | As needed |

*Patients at home often adapt to less-frequent monitoring.

†Give intramuscular vitamin K once weekly while on total parenteral nutrition and nil by mouth.

Modified from Grodner M and others 2007 Foundations and clinical applications of nutrition: a nursing approach, ed 4. St Louis, Mosby.

LIPID EMULSIONS

provide supplemental energy and prevent essential fatty acid deficiencies. These emulsions can be administered through a separate peripheral line, through the central line via Y-connector tubing (see Chapter 38) or as an admixture to the PN solution. The addition of lipid emulsion to the PN solution is called a total parenteral nutrition (TPN) mixture and is given over a 24-hour period. The admixture should not be used if oil droplets are observed or if an oil or creamy layer is observed on the surface of the admixture. This observation indicates that the emulsion has broken into large lipid droplets that can cause fat emboli if administered. Lipid emulsions are white and opaque; thus care should be taken to avoid confusing enteral formula with parenteral lipids.

INITIATING PN

Solutions of less than 10% dextrose may be given in a peripheral vein in combination with amino acids and lipids. Peripheral solutions are not as calorically dense and are therefore usually temporary. Parenteral nutrition with greater than 10% dextrose requires a CVC that is placed into a high-flow central vein such as the superior vena cava by a doctor under sterile conditions (Figure 36-12). Nurses who have special training insert peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) that are started in a vein of the forearm and threaded into the subclavian or superior vena cava vein.

After CVC placement, the catheter is flushed with saline or heparin until the position is radiographically confirmed. The doctor sutures the catheter in place and covers the site with a sterile dressing. A chest X-ray examination identifies any complications.

BEGINNING AN INFUSION

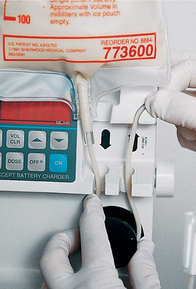

Before beginning an infusion, the nurse compares the doctor’s order with the solution prepared by the pharmacy and checks the solution for particulate matter or a break in the lipid emulsion. An infusion pump is always used.

INFUSION FLOW RATE

Patients initially receive PN solutions at a moderate rate such as 40–60 mL/h. The rate is gradually increased until the target energy needs are being supplied. Too-rapid administration of hypertonic dextrose can result in an osmotic diuresis and dehydration (see Chapter 38). If an infusion falls behind schedule, the nurse should not increase the rate in an attempt to catch up. Sudden discontinuation of the solution can cause hypoglycaemia. Usually, 5–10% dextrose is infused when PN solution is suddenly discontinued. Diabetic patients are more at risk.

Patients who receive PN at home on a long-term basis are frequently acclimatised to a system of delivering 1–3 L of PN over 12 hours at night. The CVC is flushed and bunged (plugged with a sterile ‘bung’ or stopper) each morning for independent mobility during daytime hours. Nocturnal administration of PN is done by tapering the flow rate up at the beginning and down when ending. This individualised routine is tested during hospital stays for success.

PREVENTING COMPLICATIONS

Complications of PN include mechanical complications from insertion of the CVC, infection and metabolic aberrations (Table 36-15). Pneumothorax results from a puncture insult to the pulmonary system and culminates in accumulation of air in the pleural cavity with subsequent impaired breath. Pneumothorax is usually accompanied by symptoms of sudden sharp chest pain, dyspnoea and coughing, and occurs most often during CVC placement. Other complications of CVC insertion are cardiac dysrhythmias and, infrequently, rupture of major vessels.

TABLE 36-15 COMPLICATIONS OF PARENTERAL NUTRITION (PN)

| PROBLEM | SIGNS/SYMPTOMS | INTERVENTION |

|---|---|---|

| Air embolism | Tachypnoea, apnoea, wheezing, hypotension, cyanosis |

Turn patient to left lateral decubitus position, instruct patient to perform Valsalva manoeuvre and lower head of bed Cap open end of catheter or tape perforation in catheter wall Administer oxygen; notify doctor Maintain integrity of closed system, and have patient perform Valsalva manoeuvre when changing cap |

| Catheter occlusion | No flow or sluggish flow through the catheter | Temporarily stop infusion and flush with heparin; if effort to flush is unsuccessful, attempt to aspirate a clot; if still unsuccessful, follow protocol for use of thrombolytic agent (e.g. urokinase) |

| Catheter sepsis | Fever, chills, glucose intolerance, positive blood culture |

To prevent, change catheter site dressing if it becomes wet or contaminated, use aseptic technique when changing dressing or handling IV tubing, catheter caps or PN containers Do not hang a single container of PN for more than 24 hours, or lipids more than 12 hours; use an inline 22-micron filter to remove bacteria* |

| Electrolyte imbalance | Monitor Na, Ca, K, Cl, PO4, Mg and CO2 levels |

See Chapter 39 for signs of deficiency/toxicity Check TPN for supplemental electrolyte levels. Notify doctor of imbalances |

| Fatty liver | LFT and bilirubin elevation, jaundice, upper abdominal pain | |

| Hypercapnia | Increased oxygen consumption, increased CO2, respiratory quotient > 1.0, minute ventilation | To prevent, ventilator-dependent patients are at risk; monitor parameters; provide 30–60% of energy requirements as fat |

| Hyperglycaemia | Thirst, headache, lethargy, increased urination | |

| Hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar non-ketotic dehydration/coma (HHNC) | Hyperglycaemia (> 500 mg/dL), glycosuria, serum osmolarity > 350 mOsm/L, confusion, azotaemia, headache, severe signs of dehydration (see Chapter 39), hypernatraemia, metabolic-acidosis, convulsions, coma |

To prevent, monitor blood glucose, BUN, serum osmolarity, glucose in urine and fluid losses; administer insulin as ordered; replace fluids as needed; maintain consistent infusion rate; and provide 30% of daily energy needs as fat Patients at risk are hypermetabolic, receiving steroids, elderly, diabetic, have impaired renal or pancreatic function or are septic |

| Hypoglycaemia | Diaphoresis, shakiness, confusion, loss of consciousness | |

| Pneumothorax | Severe dyspnoea, cyanosis, X-ray confirmation | Complication that occurs upon catheter insertion, may evolve slowly afterwards. Monitor for first 24 hours for pulmonary distress. Notify doctor |

| Thrombosis of central vein | Unilateral oedema of neck, shoulder and arm, pain | Follow measures to prevent sepsis; repeated or traumatic catheterisations are likely to result in thrombosis |

*With 3-in-1-admixture total parenteral nutrition (TPN), filtration is not possible due to large lipid molecules.

Air embolus can occur during insertion of the catheter or when changing the tubing or cap. Having the patient perform a Valsalva manoeuvre (holding one’s breath and ‘bearing down’) while assuming a left lateral position can prevent air embolus.

To avoid infection, the infusion tubing should be changed every 24 hours for a lipid infusion and every 48 hours when lipids are not infused. During CVC dressing changes, sterile mask and gloves are always used and insertion sites should be assessed for signs and symptoms of infection (see Chapter 29).

The TPN solution contains most of the major electrolytes, vitamins and minerals. Supplemental vitamin K must be given as ordered throughout therapy. Vitamin K can be synthesised by microflora found in the jejunum and ileum with normal use of the GI tract; since PN circumvents GI use, exogenous vitamin K must be administered.

Electrolyte and mineral imbalances may occur. Administration of concentrated glucose is accompanied by increases in endogenous insulin production, which causes ions (potassium, magnesium and phosphorus) to move intracellularly. Blood glucose levels are monitored and insulin is given if required. Liver function studies are monitored to determine the development of fatty deposits in the liver. In malnourished or cachectic patients, the resulting low serum (extracellular) levels of electrolytes and oedema may cause cardiac arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, respiratory distress, convulsions, coma or death. This has been called refeeding syndrome.

The goal is to move patients from parenteral to enteral and/or oral feeding. Once patients are meeting one-third to half their kilojoule needs per day enterally, TPN is usually decreased to half the original volume. Enteral feedings should then be increased to meet needs. When 75% of daily energy needs are consistently met with tube feeding, parenteral feeding may be discontinued. Patients who make the transition from PN to oral feedings typically have early satiety and decreased appetite. PN should be gradually decreased in response to increased oral intake. If oral intake is inadequate, small frequent meals may prove helpful. Kilojoule/protein counts are recommended when patients begin taking soft foods. When 75% of needs are being met by reliable dietary intake, PN therapy may be discontinued.