Chapter 64 NURSING MANAGEMENT: arthritis and connective tissue diseases

1. Compare and contrast the sequence of events leading to joint destruction in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

2. Detail the clinical manifestations, and multidisciplinary care and nursing management of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

3. Summarise the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and multidisciplinary care and nursing management of ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and reactive arthritis.

4. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care of septic arthritis, tick-borne infection and gout.

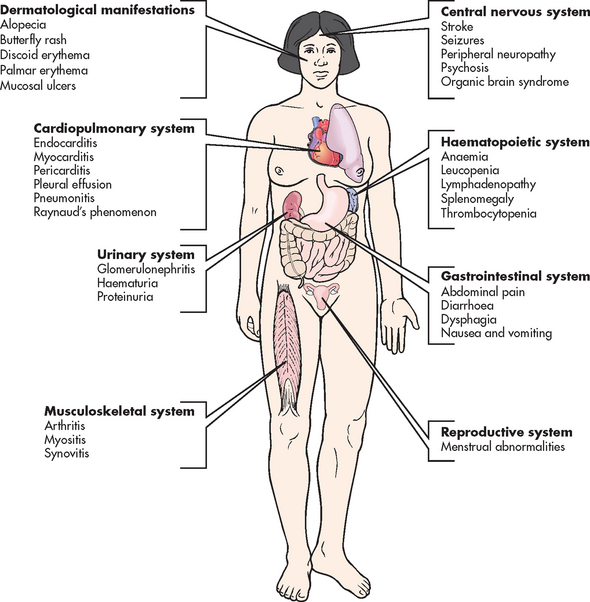

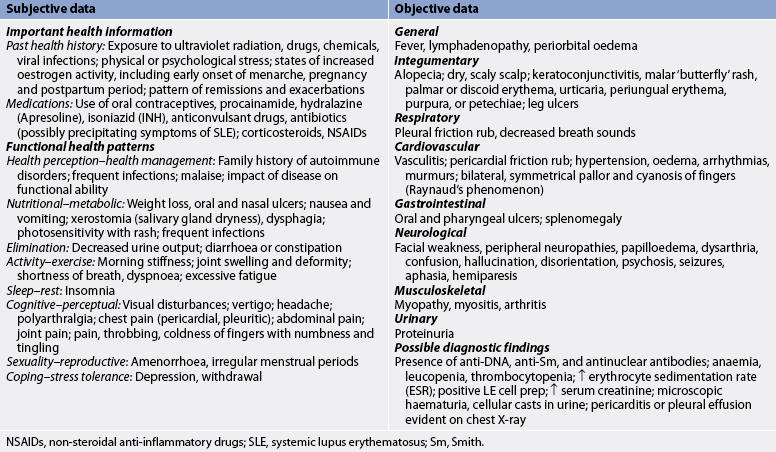

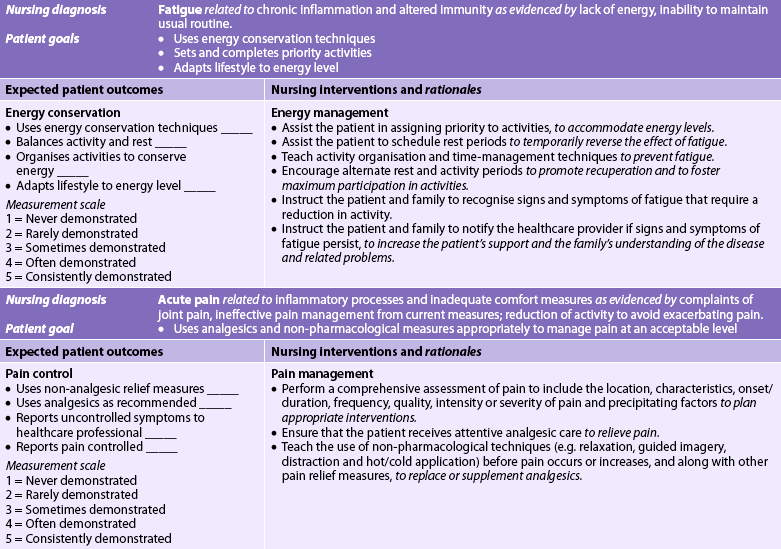

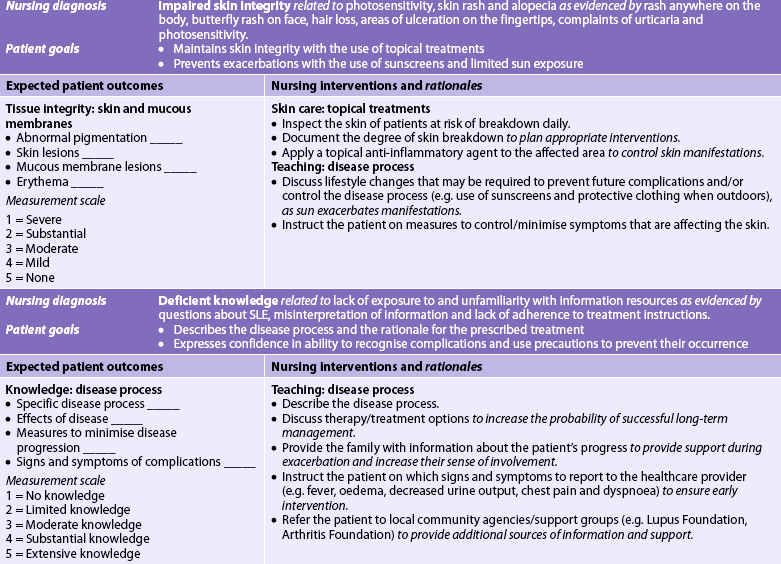

5. Evaluate the differences in pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and multidisciplinary care and nursing management of systemic lupus erythematosus, polymyositis, dermatomyositis and Sjögren’s syndrome.

6. Explain the drug therapy and related nursing management associated with arthritis and connective tissue diseases.

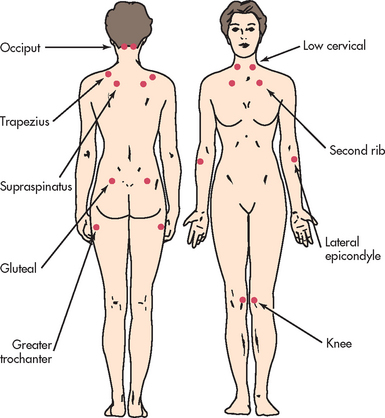

7. Compare and contrast the possible aetiologies, clinical manifestations, and collaborative and nursing management of myofascial pain syndrome, fibromyalgia syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome.

ARTHRITIS

Arthritis refers to the inflammation of a joint, whereas rheumatic disease involves the bones and muscles, as well as the joints. It is estimated that more than 3.1 million Australians are affected by arthritis (a prevalence rate of 15.2%). Because the rate of arthritis increases as people age, the prevalence rate will increase as the population ages. Within Australia, for those aged over 75 the greater proportion of sufferers are women, but for those aged between 22 and 44 years, arthritis is slightly more common in men. Factors such as socioeconomic status have been found to affect the prevalence of the disease. Arthritis occurs less frequently among those living in high socioeconomic areas compared to those living in relatively low socioeconomic areas.1 Indigenous Australians have been found to have a higher prevalence than non-Indigenous Australians.

Within New Zealand, one in seven adults (14.8%) have been told by a doctor that they have arthritis. This equates to 460,500 adults. The prevalence of arthritis is higher in women (13.2%) than in men (10.9%), and among the different ethnic groups the prevalence is 16.1% in Europeans, 11.1% in Māori, 7.9% in Pacific Islanders and 6.2% in Asians.2

There are more than 100 types of arthritis, with the most prevalent types in the developed world being osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and gout. Arthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions account for around $4 billion in health expenditure in Australia per year.1

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA), the most common form of joint (articular) disease in Australia and New Zealand, is a slowly progressive non-inflammatory disorder of the diarthrodial (synovial) joints. Osteoarthritis involves the formation of new joint tissue in response to cartilage destruction.3

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

OA is no longer considered to be a normal part of the ageing process, but ageing is one risk factor for disease development.4 Cartilage destruction may actually begin between 20 and 30 years of age and the majority of adults are affected by the age of 40. Few patients experience symptoms until they are 50 or 60, but more than half of those over 64 have X-ray evidence of the disease in at least one joint. Women are more often affected than men and they may have more severe OA.5

OA may occur as an idiopathic (formerly primary) or secondary disorder. The cause of idiopathic OA is unknown, whereas secondary OA is caused by a known event or condition that directly damages cartilage or causes joint instability (see Table 64-1).

TABLE 64-1 Causes of secondary osteoarthritis

| Cause | Effects on joint cartilage |

|---|---|

| Trauma | Dislocations or fractures may lead to avascular necrosis or uneven stress on cartilage |

| Mechanical stress | Repetitive physical activities (e.g. sports activities) cause cartilage deterioration |

| Inflammation | Release of enzymes in response to local inflammation can affect cartilage integrity |

| Joint instability | Damage to supporting structures causes instability, placing uneven stress on articular cartilage |

| Neurological disorders | Pain and loss of reflexes from neurological disorders, such as diabetic neuropathy and Charcot’s joint, causes abnormal movements that contribute to cartilage deterioration |

| Skeletal deformities | Congenital or acquired conditions such as Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease or dislocated hip contribute to cartilage deterioration |

| Haematological/endocrine disorders | Chronic haemarthrosis (e.g. haemophilia) can contribute to cartilage deterioration |

| Drugs | Drugs such as indomethacin, colchicine and corticosteroids can stimulate collagen-digesting enzymes in joint synovium |

Researchers have been unable to identify a single cause for OA, but a number of factors have been linked to disease development. The increased incidence of OA in ageing women is believed to be due to oestrogen reduction at menopause. Genetic factors also appear to play a significant role in the occurrence of OA. Modifiable risk factors have been identified, including obesity, which contributes to hip and knee OA. Regular moderate exercise, which also helps with weight control, has been shown to decrease the likelihood of disease development and progression. Anterior cruciate ligament injury, which is associated with quick stops and pivoting as in all types of football, netball and soccer, has been linked to an increased risk of knee OA.6 Occupations that require frequent kneeling and stooping are also linked to a higher risk of knee OA.

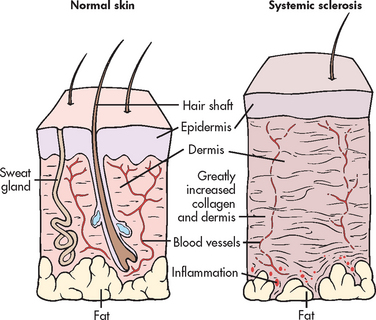

OA results from cartilage damage that triggers a metabolic response at the level of the chondrocytes (see Fig 64-1). Progression of OA causes the normally smooth, white, translucent articular cartilage to become dull, yellow and granular. Affected cartilage gradually becomes softer, less elastic and less able to resist wear with heavy use. The body’s attempts at cartilage repair cannot keep up with the destruction that is occurring. Continued changes in the collagen structure of the cartilage lead to fissuring and erosion of the articular surfaces. As the central cartilage becomes thinner, cartilage and bony growth (osteophytes) increase at the joint margins. The resulting incongruity in joint surfaces creates an uneven distribution of stress across the joint and contributes to a reduction in motion.

Figure 64-1 Pathological changes in osteoarthritis. A, Normal synovial joint. B, An early change in osteoarthritis is destruction of articular cartilage and narrowing of the joint space. There is inflammation and thickening of the joint capsule and synovium. C, With time, there is thickening of subarticular bone caused by constant friction of the two bone surfaces. Osteophytes form around the periphery of the joint by irregular overgrowths of bone. D, In osteoarthritis of the hands, osteophytes on the distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers are termed Heberden’s nodes and appear as small nodules.

Although inflammation is not characteristic of OA, a secondary synovitis may result when phagocytic cells try to rid the joint of small pieces of cartilage torn from the joint surface. These inflammatory changes contribute to the early pain and stiffness of OA. The pain of later disease results from contact between exposed bony joint surfaces after the articular cartilage has deteriorated completely.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Systemic

Systemic manifestations, such as fatigue, fever and organ involvement, are not present in OA. This is an important distinction between OA and inflammatory joint disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Joints

Manifestations of OA range from mild discomfort to significant disability. Joint pain is the predominant symptom and the typical reason that the patient seeks medical attention. Pain generally worsens with joint use. In the early stages of OA, joint pain is relieved by rest. In advanced disease, however, the patient may complain of pain with rest or experience sleep disruptions caused by increasing joint discomfort. Pain may also become worse as the barometric pressure falls before inclement weather. As OA progresses, increasing pain can contribute significantly to disability and loss of function. The pain of OA may be referred to the groin, buttock or medial side of the thigh or knee. Sitting down becomes difficult, as does rising from a chair when the hips are lower than the knees. As OA develops in the intervertebral (apophyseal) joints of the spine, localised pain and stiffness are common.

Unlike pain, which is typically provoked by activity, joint stiffness occurs after periods of rest or static position. Early morning stiffness is common but generally resolves within 30 minutes, a factor distinguishing OA from inflammatory arthritic disorders. Overactivity can cause a mild joint effusion that temporarily increases stiffness. Crepitation, a grating sensation caused by loose particles of cartilage in the joint cavity, can also contribute to stiffness. Crepitation indicates the loss of cartilage integrity and is present in more than 90% of patients with knee OA.

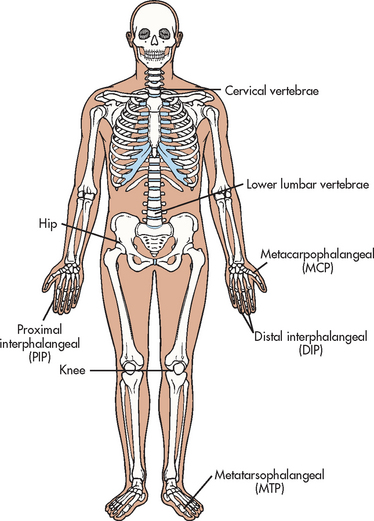

OA usually affect joints asymmetrically. The most commonly involved joints are the distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints of the fingers, the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint of the thumb, weight-bearing joints (hips, knees), the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint of the foot, and the cervical and lower lumbar vertebrae (see Fig 64-2).

Deformity

Deformity or instability associated with OA is specific to the involved joint. For example, Heberden’s nodes occur on the DIP joints as an indication of osteophyte formation and loss of joint space (see Fig 64-1, D). They can appear in the OA patient as early as age 40 and tend to be seen in family members. Bouchard’s nodes on the PIP joints indicate similar disease involvement. Heberden’s and Bouchard’s nodes are often red, swollen and tender. Although these bony enlargements usually do not cause significant loss of function, the patient may be distressed by the visible disfigurement.

Knee OA often leads to joint malalignment as a result of cartilage loss in the medial compartment. The patient has a characteristic bowlegged appearance and may develop an altered gait in response to the obvious deformity. In advanced hip OA, one of the patient’s legs may become shorter from a loss of joint space.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A bone scan, computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful to diagnose OA because of the sensitivity of these tests to detect early joint changes. X-rays are helpful in confirming disease and staging the progression of joint damage. As OA progresses, X-rays typically show joint space narrowing, bony sclerosis and osteophyte formation. However, these changes do not always correlate with the degree of pain experienced by the patient. Despite significant radiological indications of disease, the patient may be relatively free of symptoms. Conversely, another patient may have severe pain with only minimal X-ray changes.

No laboratory abnormalities or biomarkers have been identified that are specific diagnostic indicators of OA. Blood tests to confirm OA remain an active area of investigation.7 The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is normal except in instances of acute synovitis, when minimal elevations may be noted. Other routine blood tests (e.g. full blood count [FBC], renal and liver function tests) are useful only in screening for related conditions or for establishing baseline values before the initiation of therapy. Synovial fluid analysis allows differentiation between OA and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. In the presence of OA, the fluid remains clear yellow with little or no sign of inflammation.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Because there is no cure for OA, multidisciplinary care focuses on managing pain and inflammation, preventing disability, and maintaining and improving joint function (see Box 64-1). Non-pharmacological interventions are the foundation for OA management and should be maintained throughout the patient’s treatment period. Drug therapy serves as an adjunct to non-pharmacological treatments. Symptoms of disease are often managed conservatively for many years, but the patient’s loss of joint function, unrelieved pain and diminished ability to independently perform self-care may prompt a recommendation for surgery. Reconstructive surgical procedures are discussed in Chapter 62. Arthroscopic surgery for knee OA remains widely practised although recent randomised controlled trials showed no benefit in reducing patient pain and improving function.8

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative therapy

Nutritional and weight management counselling

Rest and joint protection, use of assistive devices

Complementary and alternative therapies

Drug therapy*

*See Table 64-2.

Rest and joint protection

The OA patient must understand the importance of maintaining a balance between rest and activity. The affected joint should be rested during any periods of acute inflammation and maintained in a functional position with splints or braces if necessary. However, immobilisation should not exceed 1 week because of the risk of joint stiffness with inactivity. The patient may need to modify their usual activities to decrease stress on affected joints. For example, the patient with knee OA should avoid prolonged periods of standing, kneeling or squatting. Using an assistive device such as a cane, walker or crutches can also help decrease stress on arthritic joints.

Heat and cold applications

Applications of heat and cold may help reduce complaints of pain and stiffness. Although ice is not used as often as heat in the treatment of OA, it can be appropriate if the patient experiences acute inflammation. Heat therapy is especially helpful for stiffness, including hot packs, whirlpool or spa baths, ultrasound and paraffin wax baths.

Nutritional therapy and exercise

If the patient is overweight, a weight-reduction program is a critical part of the total treatment plan. The nurse needs to help the patient evaluate their current diet to make appropriate changes. (Ch 40 discusses ways to assist the patient in attaining and maintaining a healthy body weight.) Because the load on the joints and the degree of joint mobilisation are essential to the preservation of articular cartilage integrity, the National Health and Medical Research Council in conjunction with the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners have identified exercise as a fundamental part of OA management.9 Aerobic conditioning, range-of-motion (ROM) exercises and specific programs for strengthening the quadriceps have been beneficial for many patients with knee OA.

Complementary and alternative therapies

Complementary and alternative therapies for symptom management of arthritis have become increasingly popular with patients who have failed to find relief through traditional medical care. Acupuncture, for example, has been found to be a safe treatment resulting in decreased arthritis pain for some patients with OA.10 Other therapies include yoga, massage, guided imagery and therapeutic touch (see Ch 7). Nutritional supplements such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate may be helpful in some patients for relieving moderate-to-severe arthritis pain in the knees and improving joint mobility (see the Complementary & alternative therapies box).

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Scientific evidence

Strong evidence for use in the treatment of mild-to-moderate osteoarthritis of the knee; good evidence for use in treatment of osteoarthritis in general.*

*Based on a systematic review of scientific literature. Available at www.naturalstandard.com.

Drug therapy

Drug therapy is based on the severity of the patient’s symptoms (see Table 64-2). The patient with mild to moderate joint pain may receive relief from paracetamol. The patient may receive up to 1000 mg every 6 hours, with the daily dose not to exceed 4 g.

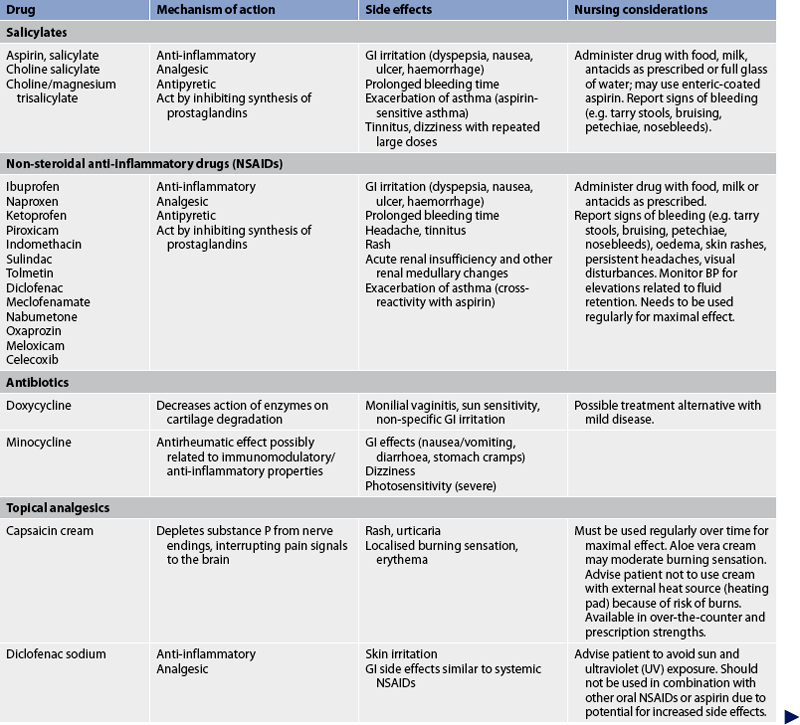

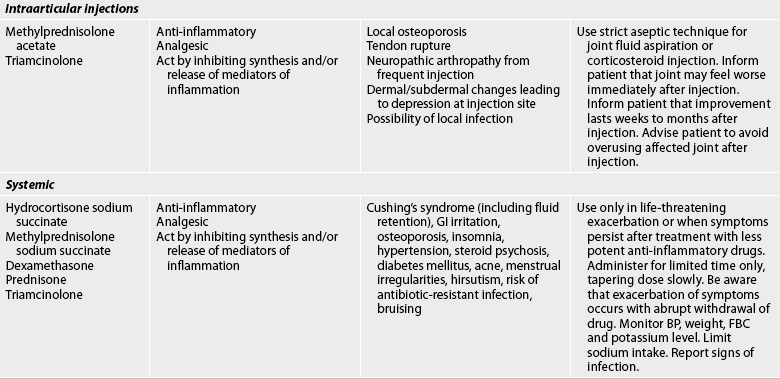

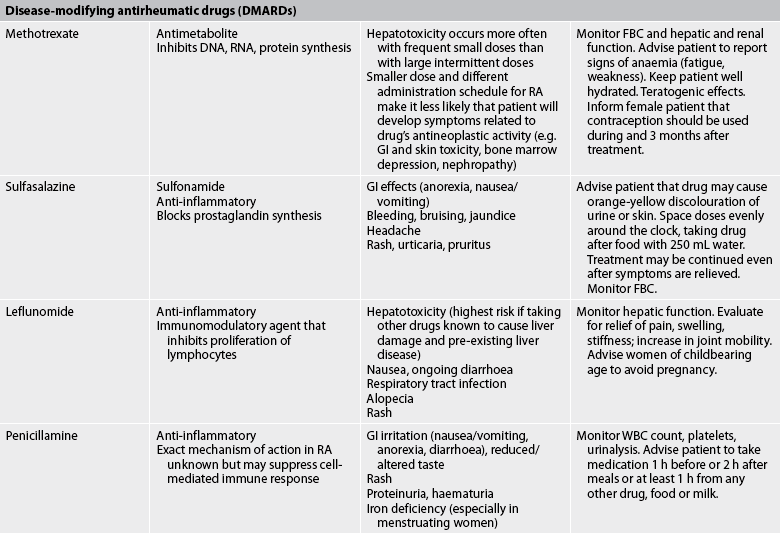

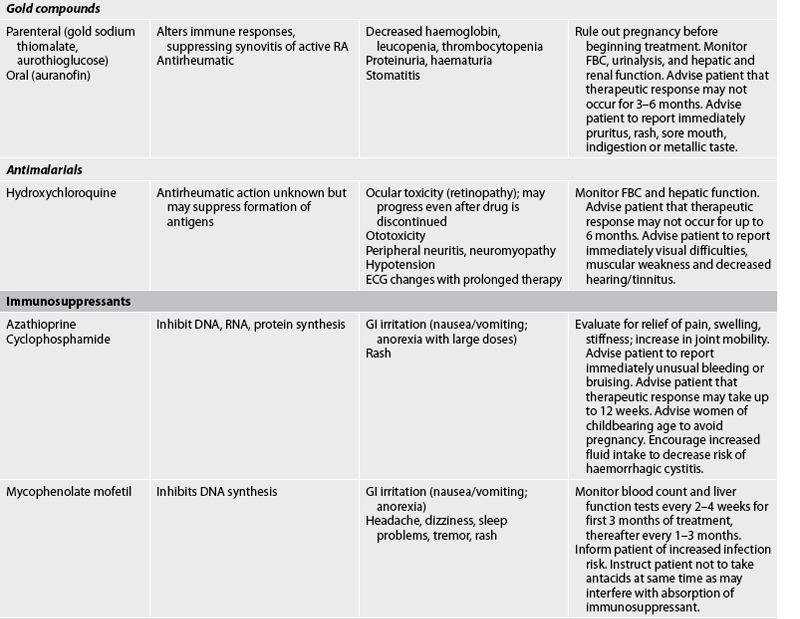

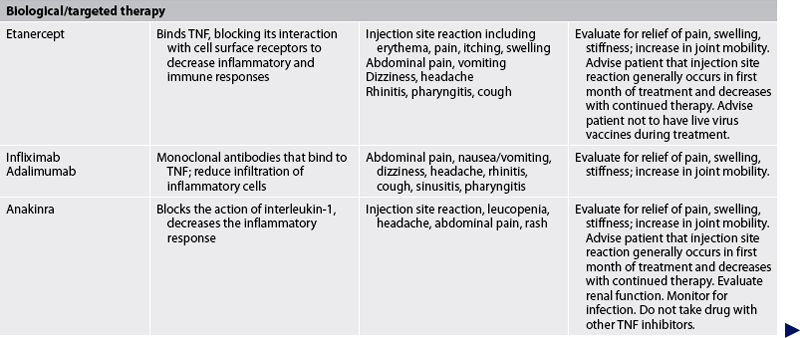

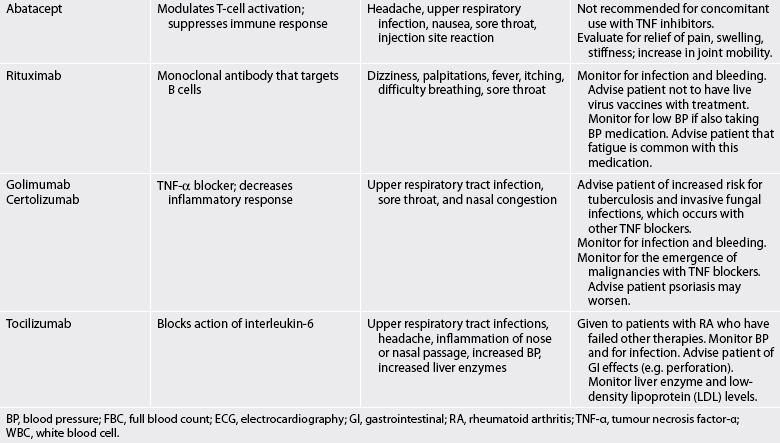

TABLE 64-2 Arthritis and connective tissue disorders

Bp, blood pressure; FBC, full blood count; ECG, electrocardiography; gi, gastrointestinal; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-α; WBC, white blood cell.

A topical agent such as capsaicin cream (a constituent of many over-the-counter creams) may also be beneficial, either alone or in conjunction with paracetamol. It blocks pain by locally interfering with substance P, which is responsible for the transmission of pain impulses. A concentrated product is available by prescription, but creams of 0.025% to 0.075% capsaicin are sold over-the-counter. Other over-the-counter products that contain camphor, eucalyptus oil and menthol may also provide temporary pain relief. Topical salicylates that can be absorbed into the blood are another alternative for patients who are able to take aspirin-containing medication. Because the effects of topical agents are not sustained, several applications may be needed daily.

For the patient who fails to obtain adequate pain management with paracetamol or for the patient with moderate-to-severe OA pain, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) may be more effective for pain treatment. NSAID therapy is typically initiated in low-dose over-the-counter strengths (ibuprofen 200 mg up to four times daily), with the dose increased as patient symptoms indicate. If the patient is at risk for or experiences gastrointestinal (GI) side effects with a conventional NSAID, supplemental treatment with a protective agent such as misoprostol may be indicated. Arthrotec 50, a combination of misoprostol and the NSAID diclofenac, is also available. Diclofenac gel may be applied for knee and hand joint pain.

Because traditional NSAIDs block the production of prostaglandins from arachidonic acid by inhibiting the production of cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (see Fig 8-9), the risk for GI erosion and bleeding is increased. Traditional NSAIDs affect platelet aggregation, leading to a prolonged bleeding time. Patients on both warfarin and an NSAID are at high risk for bleeding. Concerns have also been raised regarding the possible negative effects of long-term NSAID treatment on cartilage metabolism, particularly in older patients who may already have diminished cartilage integrity. As an alternative to traditional NSAIDs, treatment with the COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib may be considered in selected patients.11 However, the New Zealand Ministry of Health has restricted the use of COX-2 agents: they are not recommended for routine use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis except where the patient is at high risk of developing a serious GI adverse effect from other standard NSAIDs. COX-2 agents should not be prescribed to patients who are at high risk of heart attack or stroke and those taking aspirin. Within Australia, manufacturers of COX-2 inhibitors are required to place explicit warnings in product information about the increased risk of cardiovascular adverse events associated with this group of drugs.

When given in equivalent anti-inflammatory dosages, all NSAIDs are considered comparable in efficacy but vary widely in cost. Individual responses to NSAIDs are also variable. Aspirin is still preferred by some patients, but it is no longer a common treatment, and it should not be used in combination with NSAIDs because both inhibit platelet function and prolong bleeding time. Intraarticular injections of corticosteroids may be appropriate for the elderly patient with local inflammation and effusion. Four or more injections without relief suggest the need for additional intervention. Systemic use of corticosteroids is not indicated and it may actually accelerate the disease process.

Another treatment for mild-to-moderate knee OA is hyaluronic acid (HA), a type of viscosupplementation. HA is found in normal joint fluid and articular cartilage. It contributes to both the viscosity and the elasticity of synovial fluid, and its degradation can result in joint damage. Synthetic and naturally occurring HA derivatives are administered in three weekly injections directly into the joint space. Hylan G-F 20, a newer single-injection HA drug, may offer pain relief for up to 6 months. HA may be added to oral supplements of glucosamine and chondroitin. Few side effects have been reported with HA.

Medications thought to slow the progression of OA or support joint healing are known as disease-modifying osteoarthritis drugs (DMOADs). A number of drugs are under investigation with mixed results as to whether they are effective and safe. Among them is the antibiotic doxycycline, which may decrease the loss of cartilage in some patients with knee OA.12

NURSING MANAGEMENT: OSTEOARTHRITIS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: OSTEOARTHRITIS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

The nurse should carefully assess and document the type, location, severity, frequency and duration of the patient’s joint pain and stiffness. The patient should also be questioned about the extent to which these symptoms affect their ability to perform activities of daily living. The nurse should note pain management practices and question the patient about the duration and success of each treatment. Physical examination of the affected joint or joints includes assessment of tenderness, swelling, limitation of movement and crepitation. An involved joint should be compared with the contralateral joint if it is not affected.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with OA may include, but are not limited to, the following:

• acute and chronic pain related to physical activity and lack of knowledge of pain self-management techniques

• impaired physical mobility related to weakness, stiffness or pain on ambulation

• self-care deficits related to joint deformity and pain with activity

• imbalanced nutrition: more than body requirements related to intake in excess of energy output

• chronic low self-esteem related to changing physical appearance and social and work roles.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with OA will: (1) maintain or improve joint function through a balance of rest and activity; (2) use joint protection measures (see Box 64-2) to improve activity tolerance; (3) achieve independence in self-care and maintain optimal role function; and (4) use pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies to manage pain satisfactorily.

BOX 64-2 Joint protection and energy conservation

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

Include the following instructions when teaching patients with arthritis to protect joints and conserve energy.

• Maintain appropriate weight.

• Use assistive devices, if indicated.

• Avoid forceful repetitive movements.

• Avoid positions of joint deviation and stress.

• Use good posture and proper body mechanics.

• Seek assistance with necessary tasks that may cause pain.

• Develop organising and pacing techniques for routine tasks.

• Modify home and work environment to create less stressful ways to perform tasks.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

Prevention of primary OA is not possible. However, community education should focus on the alteration of modifiable risk factors through weight loss and the reduction of occupational and recreational hazards. Sports instruction and physical fitness programs should include safety measures that protect and reduce trauma to the joint structures. Congenital conditions, such as Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, that are known to predispose a patient to the development of OA should be treated promptly.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

The person with OA most often complains of pain, stiffness, limitation of function and the frustration of coping with these physical difficulties on a daily basis. The older adult may believe that OA is an inevitable part of ageing and that nothing can be done to ease the discomfort and related disability.

The patient with OA is usually treated on an outpatient basis, often by an interdisciplinary team of healthcare providers that includes a rheumatologist, a nurse, an occupational therapist and a physiotherapist. Health assessment questionnaires are often used to pinpoint areas of difficulty for the patient with arthritis. Questionnaires are updated at regular intervals to document disease and treatment progression. Treatment goals can be developed based on data from the questionnaires and the physical examination, with specific interventions to target identified problems. The patient is usually hospitalised only if joint surgery is planned (see Ch 62).

Drugs are administered for the treatment of pain and inflammation. Non-pharmacological pain management strategies may include massage, the application of heat (thermal packs) or cold (ice packs), relaxation and guided imagery. Splints may be prescribed to rest and stabilise painful or inflamed joints. Once an acute exacerbation has subsided, a physiotherapist can provide valuable assistance in planning an exercise program. Therapists may recommend Tai Chi as a low-impact form of exercise. Tai Chi can be performed by patients of all ages and may be done in a wheelchair. Nurses need to emphasise the importance of warming up beforehand to prevent stretch injuries.

Patient and family teaching related to OA is an important nursing responsibility in any care setting and is the foundation of successful disease management. The nurse should provide information about the nature and treatment of the disease, pain management, correct posture and body mechanics, correct use of assistive devices such as a cane or walker, principles of joint protection and energy conservation (see Box 64-2), nutritional choices, weight and stress management, and a therapeutic exercise program. The nurse should assure the patient that OA is a localised disease and that severe deforming arthritis is not the usual course. The patient can also gain support and understanding of the disease process through community resources available in each state in Australia and through Arthritis New Zealand. A number of organisations have self-management programs that can be suggested to people who have OA (see the Resources on p 1855).

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

Chronic pain and a loss of function of the affected joints continue to be primary concerns. Home management goals should be individualised to meet the patient’s needs, and the carer, family members and significant others should be included in goal setting and teaching. Home and work environment modification is essential for patient safety, accessibility and self-care.13 Measures include removing scatter rugs, providing rails for stairs and the bath, using night-lights and wearing well-fitting supportive shoes. Assistive devices such as canes, walkers, elevated toilet seats and grab bars also reduce the load on an affected joint and promote safety. The nurse should urge the patient to continue all prescribed therapies at home and to be open to the discussion of new approaches to symptom management.

Sexual counselling may help the patient and significant other to enjoy physical closeness by introducing the idea of alternative positions and timing for intercourse. Discussion also increases awareness of each partner’s needs. The patient can take analgesics or a warm bath to decrease joint stiffness before sexual activity.

Evaluation

Evaluation

The expected outcomes are that the patient with OA will: (1) maintain or improve joint function through a balance of rest and activity; (2) use joint protection measures to improve activity tolerance; (3) achieve independence in self-care and maintain optimal role function; (4) use pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies to manage pain satisfactorily; and (5) demonstrate that they understand what OA is and develop self-management strategies in collaboration with their healthcare team.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disease characterised by inflammation of connective tissue in the diarthrodial (synovial) joints, typically with periods of remission and exacerbation. RA is frequently accompanied by extraarticular manifestations.

RA occurs globally, affecting all ethnic groups. It can occur at any time of life, but the incidence increases with age, peaking between 30 and 50 years old. It is the second most common type of arthritis and the most common autoimmune disease. Between 1 and 2% of the populations of New Zealand and Australia are affected by RA.14 Women are affected more commonly than men.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The cause of RA is unknown. Despite past theories, no infectious agent has been cultured from blood and synovial tissue or fluid with enough reproducibility to suggest an infectious cause for the disease. An autoimmune aetiology is currently the most widely accepted.

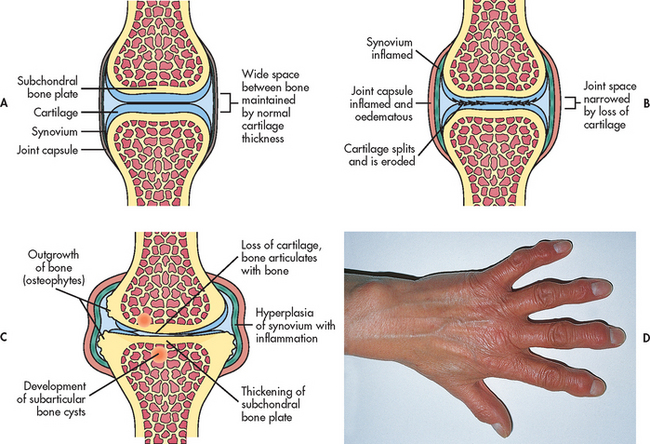

Autoimmunity

The autoimmune theory suggests that changes associated with RA begin when a susceptible host experiences an initial immune response to an antigen. The antigen, which is probably not the same in all patients, triggers the formation of an abnormal immunoglobulin G (IgG). RA is characterised by the presence of autoantibodies against this abnormal IgG. The autoantibodies are known as rheumatoid factor (RF) and they combine with IgG to form immune complexes that initially deposit on synovial membranes or superficial articular cartilage in the joints. Immune complex formation leads to the activation of complement, and an inflammatory response results. (Complement activation is discussed in Ch 12 and immune complex formation is discussed in Ch 13.) Neutrophils are attracted to the site of inflammation, where they release proteolytic enzymes that can damage articular cartilage and cause the synovial lining to thicken (see Fig 64-3). Other inflammatory cells include T helper (CD4) cells, which are the primary orchestrators of cell-mediated immune responses. Activated CD4 cells stimulate monocytes, macrophages and synovial fibroblasts to secrete the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF). These cytokines are the primary factors that drive the inflammatory response in RA.

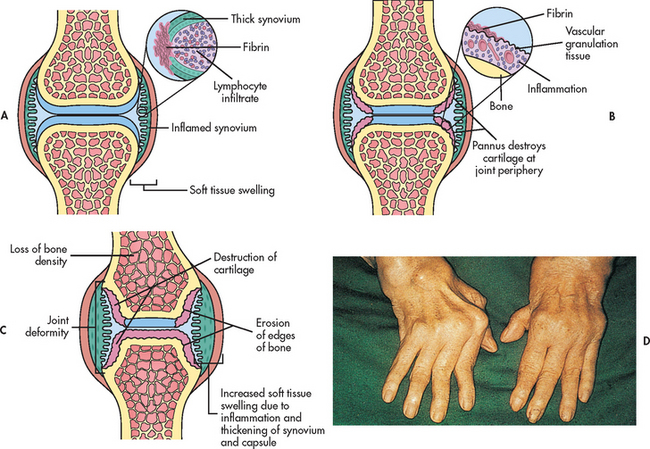

Figure 64-3 Rheumatoid arthritis. A, An early pathological change in rheumatoid arthritis is rheumatoid synovitis. The synovium is inflamed. There is a great increase in lymphocytes and plasma cells. B, With time, there is articular cartilage destruction; vascular granulation tissue grows across the surface of the cartilage (pannus) from the edges of the joint, and the articular surface shows loss of cartilage beneath the extending pannus, most marked at the joint margins. C, Inflammatory pannus causes focal destruction of bone. At the edges of the joint there is osteolytic destruction of bone, responsible for erosions seen on X-rays. This phase is associated with joint deformity. D, Characteristic deformity and soft-tissue swelling associated with severe advanced rheumatoid disease of the hands.

Joint changes from chronic inflammation begin when the hypertrophied synovial membrane invades the surrounding cartilage, ligaments, tendons and joint capsule. Pannus (highly vascular granulation tissue) forms within the joint. It eventually covers and erodes the entire surface of the articular cartilage. The production of inflammatory cytokines at the pannus–cartilage junction further contributes to cartilage destruction. The pannus also scars and shortens supporting structures such as tendons and ligaments, ultimately causing joint laxity, subluxation and contracture.

Genetic factors

Genetic predisposition appears to be important in the development of RA. For example, a higher occurrence of the disease has been noted in identical twins compared to fraternal twins. The strongest evidence for a familial influence is the increased occurrence of a human leucocyte antigen (HLA) known as HLA-DR4 in Caucasian RA patients. Other HLA variants have also been identified in patients from other ethnic groups. (HLA is discussed in Ch 13.) Smoking significantly increases the risk of RA for both men and women who are genetically predisposed to the disease.15

The pathogenesis of RA is more clearly understood than its aetiology. If unarrested, the disease progresses through four stages, which are identified in Box 64-3. The symptoms of RA and systemic lupus erythematosus can be very similar in the early stages, so it is important that the symptoms are explored properly and treated.

BOX 64-3 Anatomical stages of rheumatoid arthritis

Stage II: Moderate

X-ray evidence of osteoporosis, with or without slight bone or cartilage destruction; no joint deformities (although possibly limited joint mobility); adjacent muscle atrophy; possible presence of extraarticular soft-tissue lesions (e.g. nodules, tenosynovitis)

Stage III: Severe

X-ray evidence of cartilage and bone destruction in addition to osteoporosis; joint deformity, such as subluxation, ulnar deviation or hyperextension, without fibrous or bony ankylosis; extensive muscle atrophy; possible presence of extraarticular soft-tissue lesions (e.g. nodules, tenosynovitis)

Source: American College of Rheumatology. Classification criteria for determining progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Available at www.hopkins-arthritis.org/physician-corner/education/acr/acr.html. Used in Australia and New Zealand to classify progression.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Joints

The onset of RA is typically insidious. Non-specific manifestations such as fatigue, anorexia, weight loss and generalised stiffness may precede the onset of arthritic complaints. The stiffness becomes more localised in the following weeks to months. Some patients report a history of a precipitating stressful event such as infection, work stress, physical exertion, childbirth, surgery or emotional upset. However, research has been unable to correlate directly such events with the onset of RA.15

Specific articular involvement is manifested clinically by pain, stiffness, limitation of motion and signs of inflammation (e.g. heat, swelling, tenderness).3 Joint symptoms occur symmetrically and frequently affect the small joints of the hands (PIP and MCP) and feet (MTP). Larger peripheral joints such as the wrists, elbows, shoulders, knees, hips, ankles and jaw may also be involved. The cervical spine may be affected, but the axial spine is generally spared. Table 64-3 compares RA and OA.

TABLE 64-3 Comparison of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis

| Parameter | Rheumatoid arthritis | Osteoarthritis |

|---|---|---|

| Age at onset | Young to middle age | Usually age >40 |

| Gender | Female/male ratio is 2:1 or 3:1; less marked gender difference after age 60 | Before age 50, more men than women; after age 50, more women than men |

| Weight | Lost or maintained weight | Often overweight |

| Disease | Systemic disease with exacerbations and remissions | Localised disease with variable, progressive course |

| Affected joints | Small joints first (PIPS, MCPs, MTPs), wrists, elbows, shoulders, knees; usually bilateral, symmetrical | Weight-bearing joints of knees and hips, small joints (MCPs, DIPs, PIPs), cervical and lumbar spine; often asymmetrical |

| Pain characteristics | Stiffness lasts 1 h to all day and may decrease with use, pain is variable, may disrupt sleep | Stiffness occurs on arising but usually subsides after 30 min, pain gradually worsens with joint use and disease progression, relieved with rest |

| Effusions | Common | Uncommon |

| Nodules | Present, especially on extensor surfaces | Heberden’s (DIPs) and Bouchard’s (PIPs) nodes |

| Synovial fluid | WBC count >20,000/μL with mostly neutrophils | WBC count <2000/μL (mild leucocytosis) |

| X-rays | Joint space narrowing and erosion with bony overgrowths, subluxation with advanced disease; osteoporosis related to corticosteroid use | Joint space narrowing, osteophytes, subchondral cysts, sclerosis |

| Laboratory findings | RF positive in 80% of patients | RF negative |

| Elevated ESR, CRP indicative of active inflammation | Transient elevation in ESR related to synovitis |

CRP, C-reactive protein; dips, distal interphalangeals; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MCPs, metacarpophalangeals; MTPs, metatarsophalangeals; PIPs, proximal interphalangeals; RF, rheumatoid factor; WBC, white blood cell.

The patient characteristically experiences joint stiffness after periods of inactivity. Morning stiffness may last from 60 minutes to several hours or more, depending on disease activity. MCP and PIP joints are typically swollen. In early disease, the fingers may become spindle shaped from synovial hypertrophy and thickening of the joint capsule. Joints become tender, painful and warm to the touch. Joint pain increases with motion, varies in intensity and may not be proportional to the degree of inflammation. Tenosynovitis frequently affects the extensor and flexor tendons around the wrists, producing manifestations of carpal tunnel syndrome and making it difficult for the patient to grasp objects.

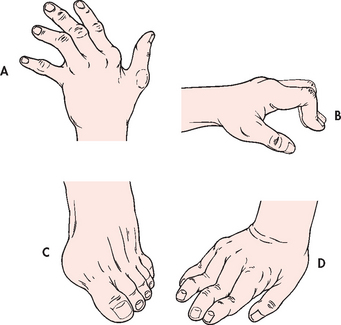

As disease activity progresses, inflammation and fibrosis of the joint capsule and supporting structures may lead to deformity and disability. Atrophy of muscles and destruction of tendons around the joint cause one articular surface to slip past the other (subluxation). Typical distortions of the hand include ulnar drift (‘zig-zag deformity’), swan neck and Boutonnière deformities (see Fig 64-4 and also Fig 64-3, D). Metatarsal head subluxation and hallux valgus (bunion) in the feet may cause pain and walking disability.

Extraarticular manifestations

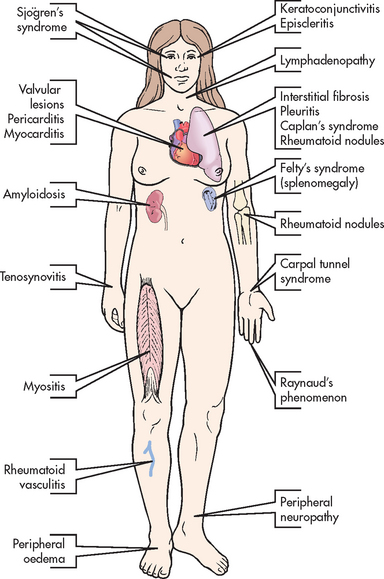

RA can affect nearly every system in the body. Extraarticular manifestations of RA are depicted in Figure 64-5. The three most common are rheumatoid nodules, Sjögren’s syndrome and Felty’s syndrome.

Rheumatoid nodules develop in up to 25% of all patients with RA. Those affected with nodules usually have high titres of RF. Rheumatoid nodules appear subcutaneously as firm, non-tender, granuloma-type masses and are usually located over the extensor surfaces of joints such as fingers and elbows. Nodules at the base of the spine and back of the head are common in older adults. Nodules develop insidiously and can persist or regress spontaneously. They are usually not removed because of the high probability of recurrence, but they can easily break down or become infected. Nodules that appear on the sclera or lungs indicate active disease and a poorer prognosis.

Sjögren’s syndrome is seen in 10–15% of patients with RA. It can occur as a disease by itself or in conjunction with other arthritic disorders such as RA and systemic lupus erythematosus. Affected patients have diminished lacrimal and salivary gland secretion, leading to complaints of dry mouth as well as burning, gritty, itchy eyes with decreased tearing, and photosensitivity. (Sjögren’s syndrome is discussed later in this chapter.)

Felty’s syndrome occurs most commonly in patients with severe, nodule-forming RA. It is characterised by inflammatory eye disorders, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, pulmonary disease and blood dyscrasias (anaemia, thrombocytopenia, granulocytopenia).

COMPLICATIONS

Without treatment, joint destruction begins as early as the first year of the disease. Flexion contractures and hand deformities cause diminished grasp strength and affect the patient’s ability to perform self-care tasks. Nodular myositis and muscle fibre degeneration can lead to pain similar to that of vascular insufficiency. Cataract development and loss of vision can result from scleral nodules. Complications can also result from rheumatoid nodules. On the skin, these nodules can ulcerate, similar to pressure ulcers. Nodules on the vocal cords lead to progressive hoarseness, and nodules in the vertebral bodies can cause bone destruction. In later disease, cardiopulmonary effects may occur. These may include pleurisy, pleural effusion, pericarditis, pericardial effusion and cardiomyopathy. Carpal tunnel syndrome of the wrist can result from swelling of the synovial membrane, which causes pressure on the median nerve and results in pain.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

An accurate diagnosis is essential to the initiation of appropriate treatment and the prevention of unnecessary disability. A diagnosis is often made based on the history and physical findings, but some laboratory tests are useful for confirmation and to monitor disease progression (see Box 64-4). Positive RF occurs in approximately 80% of patients, and titres rise during active disease. ESR and C-reactive protein (CRP) are general indicators of active inflammation. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) titres are also seen in some RA patients. Antibodies to cyclic citrulline protein (anti-CCP) are showing important potential as a marker for the early detection of RA. CCP antibodies have been found in the patient’s blood for up to 10 years before symptoms appear.7

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative therapy

Nutritional and weight management counselling

Rest and joint protection, use of assistive devices

Complementary and alternative therapies

Drug therapy*

*See Table 64-2.

Synovial fluid analysis in early disease often shows a straw-coloured fluid with many fibrin flecks. The enzyme MMP-3 is increased in the fluid of the patient with RA and it may be a marker of progressive joint damage. The white blood cell (WBC) count of synovial fluid is elevated (up to 25,000/μL). Inflammatory changes in the synovium can be confirmed by tissue biopsy.

X-rays are not specifically diagnostic of RA. They may be inconclusive during early stages of the disease, revealing only soft-tissue swelling and possible bone demineralisation. In later disease, narrowing of the joint space, destruction of articular cartilage, erosion, subluxation and deformity are seen. Malalignment and ankylosis are often evident in advanced disease. Baseline films may be useful in monitoring disease progression and treatment effectiveness. Bone scans are more useful in detecting early joint changes and confirming a diagnosis so that RA treatment can be initiated.

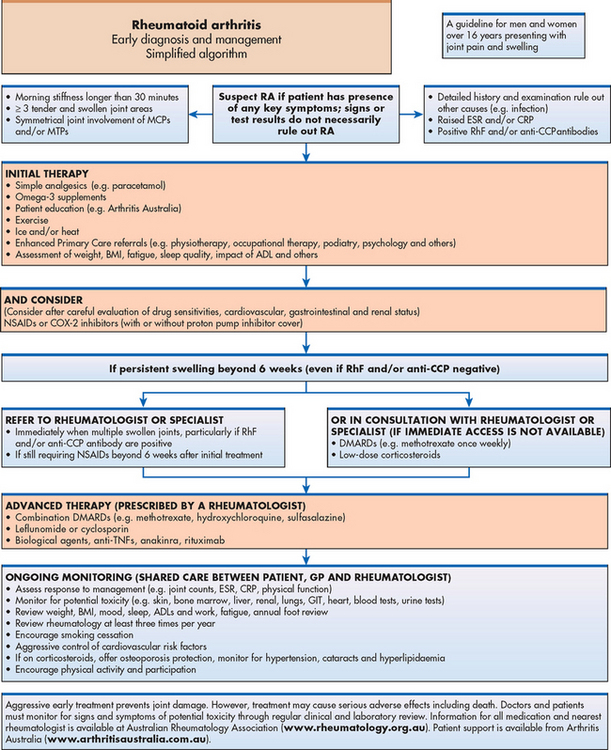

While still used by many clinicians, the 1987 American College of Rheumatology (ACR; formerly the American Rheumatism Association) classification criteria for RA have been criticised for their lack of sensitivity in early disease. The 2009 clinical guidelines developed by the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners are used in New Zealand and Australia and focus on identifying early RA. This has been done in order to emphasise the importance of earlier diagnosis and the implementation of effective disease-suppressing therapy to prevent or minimise the occurrence of the undesirable sequelae of RA. Early treatment and diagnostic tests are summarised in Figure 64-6.

Figure 64-6 RA simplified algorithm: early diagnosis and management. ADLs, activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; CCP, cyclic citrullinated peptide; CRP, C-reactive protein; DMARDs, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GIT, gastrointestinal tract; MCP, metacarpal phalanges; MTP, metatarsal phalanges; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Source: Clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of early rheumatoid arthritis. Melbourne: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2009.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Care of the patient with RA begins with a comprehensive program of education and drug therapy. Teaching regarding drug therapy includes correct administration, reporting of side effects, and frequent medical and laboratory follow-up visits. The nurse should educate the patient and family about the disease process and home management strategies. NSAIDs are prescribed to promote physical comfort. Physiotherapy helps the patient to maintain joint motion and muscle strength. Occupational therapy develops upper extremity function and encourages joint protection with splints or other assistive devices and strategies for activity pacing.

An individualised treatment plan considers the nature of the disease activity, joint function, age, gender, family and social roles, and response to previous treatment (see Box 64-4). A caring, long-term relationship with an arthritis healthcare team can promote the patient’s self-esteem and positive coping.

Drug therapy

Drugs remain the cornerstone of RA treatment (see Table 64-2). Instead of maintaining the patient on high doses of aspirin or NSAIDs until X-rays show clear evidence of the disease, healthcare providers now aggressively prescribe disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) with the knowledge that irreversible joint changes can occur as early as the first year of RA.16 These drugs have the potential to lessen the permanent effects of RA, such as joint erosion and deformity. The choice of drug is based on disease activity, the patient’s level of function and lifestyle considerations, such as the desire to bear children.

Treatment of early RA often involves therapy with methotrexate. The rapid anti-inflammatory effect of methotrexate reduces clinical symptoms in days to weeks. It is also inexpensive and has a lower toxicity compared to other drugs. Side effects include bone marrow suppression and hepatotoxicity. Methotrexate therapy requires frequent laboratory monitoring, including FBC and chemistry panel. Sulfasalazine and the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine may be effective DMARDs for mild-to-moderate disease. They are rapidly absorbed, relatively safe and well-tolerated medications. The synthetic DMARD leflunomide blocks immune cell overproduction. Its efficacy is similar to methotrexate and sulfasalazine with side effects of severe liver injury, diarrhoea and teratogenesis. In women of childbearing age, pregnancy must be excluded before therapy is initiated.

Biological/targeted therapies are also used to slow disease progression in RA. These drugs include etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, anakinra and abatacept. They can be used to treat patients with moderate-to-severe disease who have not responded to DMARDs, or in combination therapy with an established DMARD such as methotrexate.

Etanercept is a biologically engineered copy (using recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid [DNA] technology) of the TNF cell receptor. This soluble TNF receptor binds to TNF in circulation before TNF can bind to the cell surface receptor. By inhibiting binding of TNF, etanercept inhibits the inflammatory response. This drug is given in 25-mg doses twice per week (3–4 days apart) or as a 50-mg dose once weekly in a subcutaneous injection.

Infliximab and adalimumab are monoclonal antibodies against TNF. They bind to TNF, thus preventing it from binding to TNF receptors on cells. Infliximab is given intravenously (IV) as an initial dose, followed by additional dosing at 2 and 6 weeks, and then every 8 weeks thereafter. It should be given in combination with methotrexate. Adalimumab is given subcutaneously every other week. If the response is inadequate, dosing can be increased to weekly.

Anakinra is a recombinant version of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra). It blocks the biological activity of IL-1 by competitively inhibiting IL-1 binding to the IL-1 receptor. Anakinra is not available for use in New Zealand and its use is restricted in Australia. It is given as a daily subcutaneous injection. Anakinra is used to reduce the pain and swelling associated with moderate to severe RA. It can be used in combination with DMARDs but not with TNF inhibitors. Concurrent use of these agents can cause serious infection and neutropenia.

Abatacept is recommended for patients who have an inadequate response to DMARDs or TNF inhibitors. Abatacept blocks T cell activation and is given by IV infusion. Similar to anakinra, it should not be used concomitantly with TNF inhibitors.

Rituximab may be used in combination with methotrexate for patients with moderate-to-severe RA not responding to TNF antagonist therapies (e.g. etanercept, infliximab). This drug is a monoclonal antibody that targets B cells (see Ch 15). It is initially given in two IV infusions separated by 2 weeks. Some patients may be treated with a second course of the drug after 4–6 months.

Two newer TNF inhibitors, golimumab and certolizumab, improve symptoms in patients with moderate-to-severe RA. Both drugs are given in combination with methotrexate. When compared to other biological therapies, certolizumab stays in the system longer and may also show a more rapid (1–2 weeks) and significant reduction in RA symptoms.17 This drug is also used in treating Crohn’s disease.

Tocilizumab is a relatively new drug used to treat patients with moderate-to-severe RA who have not adequately responded to or cannot tolerate other approved drug classes for RA. This drug works by blocking the action of interleukin-6 (IL-6), a proinflammatory cytokine.

Additional medications used infrequently for treating RA include antibiotics (minocycline), immunosuppressants (azathioprine, penicillamine) and gold compounds (auranofin, gold sodium thiomalate).

Corticosteroid therapy can be used to aid in symptom control. Intraarticular injections may temporarily reduce the pain and inflammation associated with disease flare-ups. Long-term use of oral corticosteroids should not be a mainstay of RA treatment because of the risk of complications, including osteoporosis and avascular necrosis. However, low-dose prednisone may be used for a limited time in select patients to decrease disease activity until a DMARD effect is seen.

Various NSAIDs and salicylates continue to be included in the drug regimen to treat arthritis pain and inflammation. Enteric-coated aspirin may be used in high dosages of 4–6 g per day (10–18 tablets). The ability to obtain serum salicylate levels is helpful in developing and evaluating individualised treatment plans.

NSAIDs have anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic properties. Although many NSAIDs are potent inhibitors of inflammation, they do not appear to alter the natural history of RA. Some relief may be noted within days of the start of treatment with NSAIDs, but full effectiveness may take 2–3 weeks. NSAIDs may be used when the patient cannot tolerate high doses of aspirin. Anti-inflammatory drugs that are taken only once or twice a day may improve the patient’s ability to follow the treatment regimen (see Table 64-2). The newer-generation NSAIDs, the COX-2 inhibitors, are effective in RA as well as OA. Celecoxib is currently the only available COX-2 inhibitor, though the rheumatologist will need to discuss the risks associated with this medication with the patient.

Nutritional therapy

Although there is no special diet for RA, balanced nutrition is important. Fatigue, pain, depression, limited endurance and mobility deficits often accompany RA and may cause a loss of appetite or interfere with the patient’s ability to shop for and prepare food. Weight loss may result. An occupational therapist may help the patient to modify their home environment and to use assistive devices to make food preparation easier.

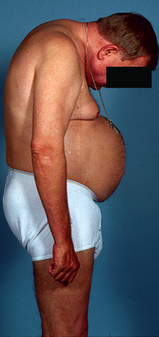

Corticosteroid therapy or immobility secondary to pain may result in unwanted weight gain. A sensible weight loss program consisting of balanced nutrition and exercise reduces stress on affected joints. Corticosteroids also increase the appetite, resulting in a higher kilojoule intake. In addition, the patient may become distressed as signs and symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome, including moon face and the redistribution of fatty tissue to the trunk, change the physical appearance. The patient should be encouraged to continue a balanced diet and not to alter the corticosteroid dose or stop therapy abruptly. Weight slowly adjusts to normal several months after cessation of therapy.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

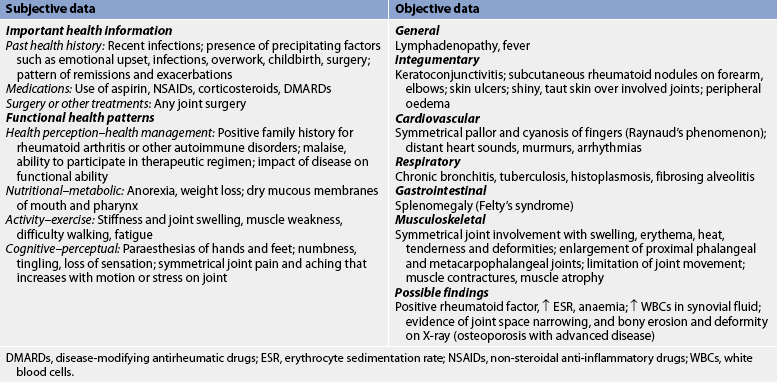

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from the patient with RA are presented in Table 64-4.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

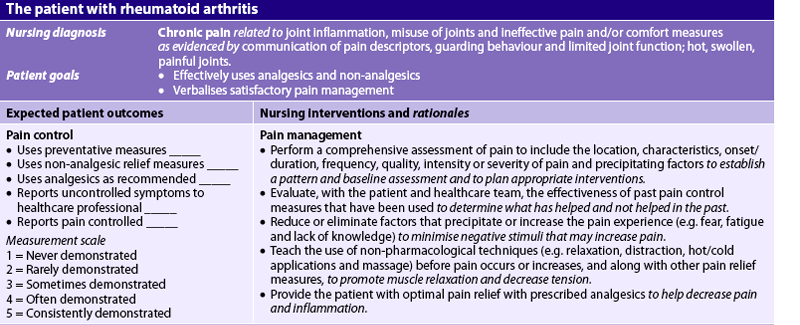

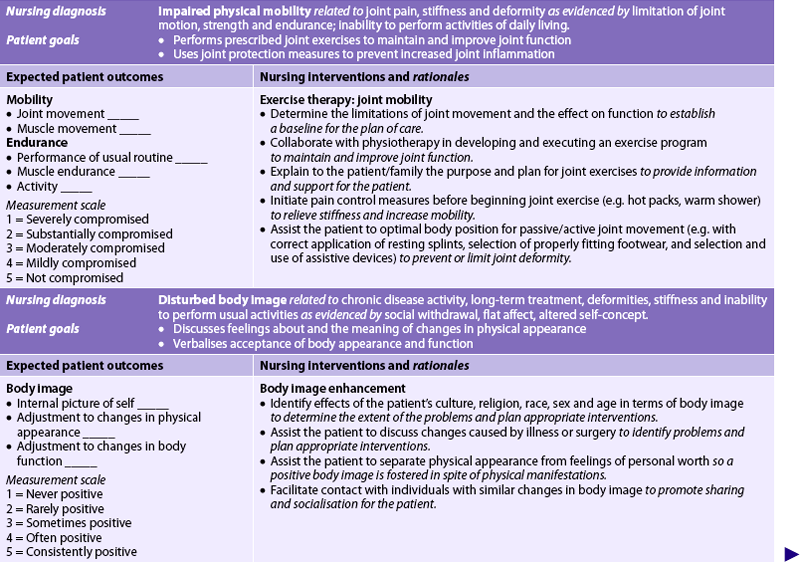

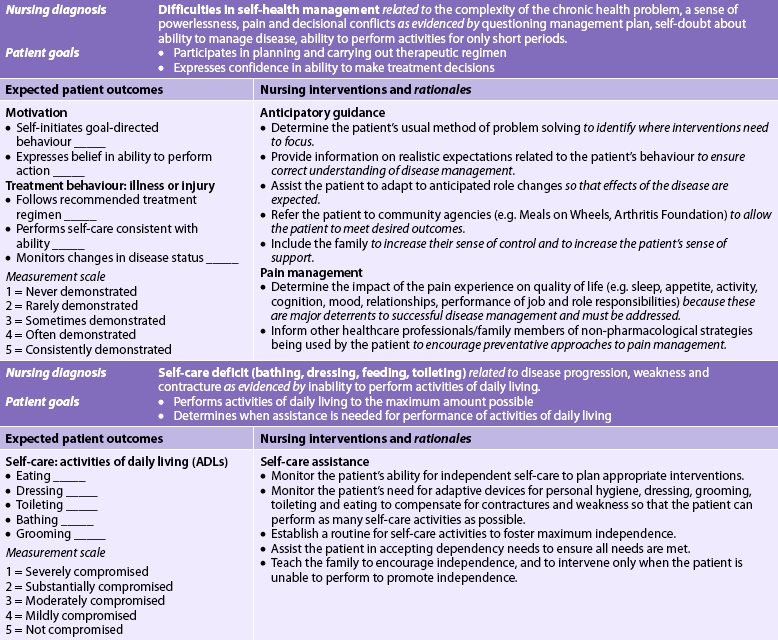

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with RA may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 64-1.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with RA will: (1) have satisfactory pain management; (2) have minimal loss of functional ability of the affected joints; (3) participate in planning and carrying out the therapeutic regimen; (4) maintain a positive self-image; and (5) perform self-care to the maximum amount possible.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

Prevention of RA is not yet possible. However, community education programs should focus on symptom recognition to promote early diagnosis and treatment of RA. Arthritis New Zealand and the various Arthritis Foundations in Australia offer many publications, classes and support activities to assist people (see the Resources on p 1855).

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

The primary goals in the management of RA are the reduction of inflammation, management of pain, maintenance of joint function and prevention or minimisation of joint deformity. Goals may be met through a comprehensive program of drug therapy, rest, joint protection, heat and cold applications, exercise, and patient and family teaching. The nurse works closely with the healthcare provider, physiotherapist, occupational therapist and social worker to help the patient to restore function and make appropriate lifestyle adjustments to chronic illness.

The newly diagnosed RA patient is usually treated on an outpatient basis, although hospitalisation may be necessary for patients with extraarticular complications or advancing disease requiring reconstructive surgery for disabling deformities. Intervention begins with a careful physical assessment (e.g. joint pain, swelling, ROM and general health status) and includes an evaluation of psychosocial needs (e.g. family support, sexual satisfaction, emotional stress, financial constraints, career limitations) and environmental concerns (e.g. transportation, home or work modifications). After any problems have been identified, the nurse can coordinate a carefully planned program for rehabilitation and education with the interdisciplinary healthcare team.

Suppression of inflammation may be achieved effectively through the administration of NSAIDs, DMARDs and biological/targeted therapies. Careful attention to timing is critical to sustain a therapeutic drug level and reduce early morning stiffness. The nurse should discuss the action and side effects of each prescribed drug and the importance of necessary laboratory monitoring. Many patients with RA will take several different drugs, and the nurse needs to make the drug regimen as understandable as possible. Patients should be encouraged to develop a method for remembering to take their medications (e.g. pill containers or other system).

Non-drug management may include the use of therapeutic heat and cold, rest, relaxation techniques, joint protection (see Boxes 64-2 and 64-5), biofeedback, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (see Ch 8) and hypnosis. The patient and family should choose therapies that promote optimal comfort within the parameters of their lifestyle.

BOX 64-5 Protection of small joints

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

Include the following instructions when teaching the patient with arthritis to protect small joints.

Lightweight splints may be prescribed to rest an inflamed joint and to prevent deformity from muscle spasms and contractures. The splints should be removed at regular intervals to give skin care and perform ROM exercises. After assessment has been completed and supportive care has been given, the splints are reapplied as prescribed. The occupational therapist may help to identify additional self-help devices that can assist in activities of daily living.

Nursing care and procedures should be planned around the patient’s morning stiffness. Sitting or standing in a warm shower, sitting in a bath with warm towels around the shoulders or simply soaking the hands in a basin of warm water may help relieve joint stiffness and allow the patient to perform activities of daily living more comfortably.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

Rest

Rest

Alternating scheduled rest periods with activity throughout the day helps relieve fatigue and pain. The amount of rest needed varies according to the severity of the disease and the patient’s limitations. The patient should rest before becoming exhausted. Total bed rest is rarely necessary and should be avoided to prevent stiffness and immobility. However, even a patient with mild disease may require daytime rest in addition to 8–10 hours of sleep at night. The nurse can help the patient to identify ways to modify daily activities to avoid overexertion that can lead to fatigue and exacerbation of disease activity. For example, the patient may tolerate meal preparation more easily while sitting on a high stool in front of the sink. The nurse should assist the patient to pace activities and set priorities based on realistic goals.

Good body alignment while resting can be maintained through use of a firm mattress or bed board. Positions of extension should be encouraged, and positions of flexion should be avoided. Splints and casts may be helpful in maintaining proper alignment and promoting rest, especially when joint inflammation is present. Lying prone for half an hour twice daily is also recommended. To decrease the risk of joint contracture, pillows should never be placed under the knees. A small, flat pillow may be used under the head and shoulders.

Joint protection

Joint protection

Protecting joints from stress is important. The nurse can help the patient to identify ways to modify tasks to put less stress on joints during routine activities (see Box 64-5). Energy conservation requires careful planning. The emphasis is on work simplification techniques. Work should be done in short periods with scheduled rest breaks to avoid fatigue (pacing). Work should also be spread throughout the week rather than attempted at one time (e.g. all cleaning should not be done on the weekend). Activities should be organised to avoid going up and down stairs repeatedly. Carts can be used to carry supplies, or materials that are used often can be stored in a convenient, easily reached area. Time-saving joint protective devices (e.g. an electric can opener) should be used whenever possible. Tasks can also be delegated to other family members.

Patient independence may be increased by occupational therapy training with assistive devices that help simplify tasks, such as built-up utensils, buttonhooks, modified drawer handles, lightweight plastic dishes and raised toilet seats. Wearing shoes with Velcro fasteners and clothing with buttons or a zipper down the front instead of the back makes dressing easier. A cane or walker offers support and relief of pain when walking. A platform wheeled walker further minimises strain on the small joints of the hands and wrists.

Can folic acid decrease gastrointestinal side effects of methotrexate therapy?

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Clinical question

For patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) on long-term methotrexate therapy (P), does folic acid supplementation (I) versus no folic acid supplementation (C) decrease gastrointestinal (GI) side effects (O)?

Critical appraisal and synthesis of evidence

Implications for nursing practice

• Consult with treating doctor regarding folic acid supplements for patients on long-term methotrexate therapy.

• Counsel the patient that folic acid supplements will probably be needed as methotrexate therapy continues.

• Use of folic acid supplements does not decrease the need to monitor laboratory values for early hepatic toxicity.

P, patient population of interest; I, intervention or area of interest; C, comparison of interest or comparison group; O, outcome(s) of interest.

Visser K, Katchamart W, Loza E, et al. Multinational evidence-based recommendations for the use of methotrexate in rheumatic disorders with a focus on rheumatoid arthritis: integrating systematic literature research and expert opinion of a broad international panel of rheumatologists in the 3E Initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1086.

Heat and cold therapy and exercise

Heat and cold therapy and exercise

Heat and cold applications can help relieve stiffness, pain and muscle spasm. Application of ice is especially beneficial during periods of disease exacerbation, whereas moist heat appears to offer better relief of chronic stiffness. The treatment modality should be selected according to disease severity, ease of application and cost. Superficial heat sources such as heating pads, moist hot packs, paraffin baths, whirlpool or spa baths and warm baths or showers can relieve stiffness to allow participation in therapeutic exercises. Plastic bags of frozen vegetables (e.g. peas or corn), which can easily mould around the shoulder, wrists or knees, are an easy home treatment. The patient can also use ice cubes or small paper cups of frozen water to massage proximal or distal to a painful joint. Heat and cold can be used as often as desired; however, the heat application should not exceed 20 minutes at one time, and the cold application should not exceed 10–15 minutes at one time. The nurse should alert the patient to the possibility of an ice burn and to avoid the use of a heat-producing cream (e.g. capsaicin) with another external heat device.

Individualised exercise is an integral part of the treatment plan. A therapeutic exercise program is usually developed by a physiotherapist and includes exercises that improve the flexibility and strength of the affected joints, and the patient’s overall endurance. Reinforce program participation and ensure that the exercises are being done correctly. Inadequate joint movement can result in progressive joint immobility and muscle weakness, and overaggressive exercise can result in increased pain, inflammation and joint damage. Emphasise that participating in a recreational exercise program (e.g. walking, swimming) or performing usual daily activities does not eliminate the patient’s need for therapeutic exercise to maintain adequate joint motion.

Gentle ROM exercises are usually done daily to keep the joints functional. The patient should have the opportunity to practise the exercises with supervision. Careful adherence to the prescribed exercise program should be a prime goal of the teaching program. Aquatic exercises in warm water (25–30°C) allow easier joint movement because of the buoyancy of the water. At the same time, although movement seems easier, water provides two-way resistance that makes muscles work harder than they would on land. Aerobic conditioning programs have been shown to improve the physical fitness levels of patients with RA. During acute inflammation, exercise should be limited to one or two repetitions.

Psychological support

Psychological support

Self-management and adherence to an individualised home treatment program can be accomplished only if the patient has a thorough understanding of RA, the nature and course of the disease, and the goals of therapy. In addition, the patient’s value system and perception of the disease must be considered. The patient is challenged constantly by problems of limited function and fatigue, loss of self-esteem, altered body image and fear of disability and deformity. Alterations in sexuality should be discussed. Chronic pain or loss of function may make the patient vulnerable to unproven or even dangerous remedies through the claims of false advertising. The nurse can help the patient to recognise fears and concerns that are faced by all people who live with chronic illness.

Evaluation of the family support system is important. Financial planning may be necessary. Community resources such as a home care nurse, homemaker services and vocational rehabilitation may be considered. Self-help groups may be beneficial for some patients.

SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES

The spondyloarthropathies are a group of interrelated multisystem inflammatory disorders that affect the spine, peripheral joints and periarticular structures. These disorders are all negative for RF. Thus they are often referred to as seronegative arthropathies. Inheritance of HLA-B27 is strongly associated with occurrence of these diseases. Both genetic and environmental factors play a role in the development of this group of diseases, which includes ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and reactive arthritis. (HLAs and their relationship to autoimmune diseases are discussed in Ch 13.) The spondyloarthropathies share clinical and laboratory characteristics that make it difficult to distinguish among them in early disease. A diagnosis is made when inflammatory spinal pain or asymmetrical synovitis is accompanied by one or more of the following: (1) episodes of alternating buttock pain; (2) radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis; (3) heel enthesopathy (e.g. plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinitis); (4) positive family history of spondyloarthropathy in a first-degree relative; (5) current or documented history of psoriasis; (6) current or documented history of inflammatory bowel disease; and (7) urethritis, cervicitis or acute diarrhoea that occurred within the month preceding onset of arthritic symptoms.18

Ankylosing spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory disease that primarily affects the axial skeleton, including the sacroiliac joints, intervertebral disc spaces and costovertebral articulations. The HLA-B27 antigen is found in approximately 80–90% of people with AS. Individuals with the antigen have a 20 times greater risk of developing a spondyloarthropathy than those who are HLA-B27 negative.19 Although the usual age of onset is 15–35 years, the highest incidence of the disease is in people 25–34 years of age. Men are three to five times more likely to develop AS than women. The disease may go undetected in women because of a milder course and because the disease is not often considered in a differential diagnosis for women.

Gerontological considerations: arthritis

The prevalence of arthritis in older adults is high, and the disease is accompanied by problems unique to this age group. The most problematic areas related to connective tissue disease in older adults include the following:

1. The high incidence of OA expected in older adults may prevent their healthcare provider from considering the presence of other types of arthritis.

2. Age alone causes changes in serological profiles, making interpretation of laboratory values such as RF and ESR more difficult.

3. Polypharmacy in the older adult can result in iatrogenic arthritis.

4. Non-organic musculoskeletal pain syndromes and weakness may be related to depression and physical inactivity.

5. Diseases such as SLE, which commonly occurs in younger adults, can develop in a milder form in older adults.

Ageing brings many physical and metabolic changes that may increase the older patient’s sensitivity to both the therapeutic and the toxic effects of some drugs. The use of NSAIDs with a shorter half-life may require more frequent dosing but may also produce fewer side effects in the older patient with altered drug metabolism. The older adult who takes NSAIDs has an increased risk for side effects, particularly GI bleeding and renal toxicity. The common occurrence of polypharmacy makes the use of additional drugs in RA treatment particularly challenging in the older adult because of the increased likelihood of untoward drug interactions. The drug regimen should be simplified as much as possible to increase adherence (e.g. limited number of drugs with decreased frequency of administration), particularly for the patient without regular assistance.

A major concern of treatment in the older patient relates to the use of corticosteroid therapy. Corticosteroid-induced osteopenia can add to the problem of decreased bone density related to age and inactivity. It can also increase the occurrence of pathological fractures, especially compression fractures of vertebrae. Corticosteroid-induced myopathy can be minimised or prevented by an age-appropriate exercise program. Although important for all age groups, an adequate support system for the older adult is a critical factor in the ability to follow a treatment regimen that includes nutritional planning, exercise, general health maintenance and appropriate pharmacotherapy.

HEALTH DISPARITIES

Incidence

• HLA-B27 is present in 8% of the general population, including those without ankylosing spondylitis (AS)

• About 80–90% of people with AS have the HLA-B27 antigen

• Only 2% of people with HLA-B27 have clinically detectable disease

• AS is three to five times more common in men than in women

• It occurs more often in those of Western European descent than in other ethnic groups

Clinical implications

• Diagnosis of AS usually occurs between the ages of 18 and 40

• It is a systemic disease often affecting the eyes and heart

• Genetic and environmental factors play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease

• AS is present in about 3–10% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

• About 50–70% of patients with both AS and IBD are HLA-B27 positive

Source: Better Health Victoria. Ankylosing spondylitis. Available at www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/bhcv2/bhcarticles.nsf/pages/ankylosing_spondylitis.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The cause of AS is unknown. Genetic predisposition appears to play an important role in the disease pathogenesis, but the precise mechanisms are unknown. Aseptic synovial inflammation in the joints and adjacent tissue causes the formation of granulation tissue (pannus) and the development of dense fibrous scars that lead to fusion of articular tissues. Extraarticular inflammation can affect the eyes, lungs, heart, kidneys and peripheral nervous system.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND COMPLICATIONS

AS is characterised by symmetrical sacroiliitis and progressive inflammatory arthritis of the axial skeleton. Symptoms of inflammatory spine pain are the first clues to a diagnosis of AS. The patient typically complains of low back pain, stiffness and limitation of motion that is worse during the night and in the morning but improves with mild activity. In women, early symptoms of disease may manifest as pain and stiffness in the neck rather than the lower back. General symptoms such as fever, fatigue, anorexia and weight loss are rarely present. Uveitis (intraocular inflammation) is the most common non-skeletal symptom. It can appear as an initial presentation of the disease years before arthritic symptoms develop. AS patients may also experience chest pain and sternal/costal cartilage tenderness that can be distressing.

Severe postural abnormalities and deformity can lead to significant disability for the patient with AS (see Fig 64-7). Impaired spinal ROM and fixed kyphosis contribute to altered visual function, raising concerns about safe ambulation. Aortic insufficiency and pulmonary fibrosis are frequent complications. Cauda equina syndrome can also result, contributing to lower extremity weakness and bladder dysfunction. In addition, the patient is at risk for spinal fracture because of osteoporosis.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

X-rays are essential for the diagnosis of AS. However, spinal X-rays are seldom useful in initial diagnosis. Instead, pelvic X-rays demonstrate characteristic changes of sacroiliitis that range from subtle erosion to completely fused joints in which the joint spaces have been obliterated. Changes on later spinal films include the appearance of ‘bamboo spine’, which is the result of calcifications (syndesmophytes) that bridge from one vertebra to another. Laboratory testing is not specific, but an elevated ESR and mild anaemia may be seen. When the suspicion of AS is high, the presence of the HLA-B27 antigen improves the likelihood of this diagnosis.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Prevention of AS is not possible. However, families with other diagnosed HLA-B27–positive rheumatic diseases (e.g. acute anterior uveitis, juvenile spondyloarthritis) should be alert to signs of low back pain for early identification and treatment of AS.

Care of the patient with AS is aimed at maintaining maximal skeletal mobility while decreasing pain and inflammation. Heat applications can help in the relief of local symptoms. NSAIDs and salicylates are commonly prescribed. DMARDs such as sulfasalazine or methotrexate have little effect on spinal disease but may be helpful with peripheral joint disease. Local corticosteroid injections may be beneficial in relieving symptoms. Etanercept, a biological/targeted therapy, binds TNF and inhibits its action. TNF, which promotes inflammation, is found in elevated levels in the blood and certain tissues of patients with AS. Etanercept has been shown to reduce active inflammation and improve spinal mobility.20 Additional anti-TNF biological agents (infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab) may also be effective.

Once pain and stiffness are managed, exercise is essential. Postural control is important to minimise spinal deformity. The exercise regimen should include back, neck and chest stretches. Hydrotherapy has also been shown to decrease pain and facilitate spinal extension. Surgery may be indicated for severe deformity and mobility impairment. Spinal osteotomy and total joint replacement are the most commonly performed procedures (see Ch 62).

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS

A key responsibility is to educate the patient with AS about the disease and the principles of therapy. The home management program should include regular exercise and attention to posture, local moist heat applications and knowledgeable use of drugs.

Baseline ROM assessment should include chest expansion (using breathing exercises). If the patient smokes, they should be encouraged to give up smoking to decrease the risk for lung complications in those with reduced chest expansion. Ongoing physiotherapy should include gentle, graded stretching and strengthening exercises to preserve ROM and improve thoracolumbar flexion and extension. Excessive physical exertion should be discouraged during periods of active flare-up of the disease. Proper positioning at rest is essential. The mattress should be firm and the patient should sleep on their back with a flat pillow, avoiding positions that encourage flexion deformity. Postural training emphasises avoiding spinal flexion (e.g. leaning over a desk), heavy lifting and prolonged walking, standing or sitting. Sports that facilitate natural stretching, such as swimming and racquet games, should be encouraged. Family counselling and vocational rehabilitation are important.

Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriasis is a common benign, inflammatory skin disorder that appears to have a genetic predisposition (see Ch 23). Approximately 10% of the 3 million people with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA). PsA is now recognised as a progressive inflammatory disease that can cause significant disability. The exact cause of PsA is unknown, but a combination of immune, genetic and environmental factors is suspected. PsA can occur in five forms:

• arthritis involving primarily the small joints of the hands and feet

• asymmetrical arthritis involving joints of the extremities

• symmetrical polyarthritis resembling RA

• arthritis of the sacroiliac joints and spine (psoriatic spondylitis)

• arthritis mutilans, a rare but very deforming and destructive disease.21

On X-ray, the cartilage loss and erosion resemble that of RA. Advanced cases of PsA often reveal widened joint spaces, and a ‘pencil in cup’ deformity is common at the DIP joints as a result of osteolysis. Elevated ESR, mild anaemia and elevated blood uric acid levels can be seen in some patients. Therefore, the diagnosis of gout must be excluded. Treatment includes splinting, joint protection and physiotherapy. Intramuscular gold therapy was used to treat PsA in the past with some success, but has been replaced by newer DMARDs such as methotrexate, which are effective for both articular and cutaneous manifestations. Sulfasalazine and cyclosporin have been used with some success, and biological/targeted therapy drugs, including etanercept, golimumab, adalimumab and infliximab, are also used.

Reactive arthritis

Reactive arthritis (Reiter’s syndrome) occurs more commonly in young men than in young women. It is associated with a symptom complex that includes urethritis, conjunctivitis and mucocutaneous lesions. In women, symptoms also include cervicitis. Although the exact aetiology is unknown, reactive arthritis appears to occur after certain types of genitourinary or GI tract infections.22 Chlamydia trachomatis is most often implicated in sexually transmitted reactive arthritis. Men and women appear to have equal risk for developing dysenteric reactive arthritis, which typically occurs within days or weeks after infection with Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter or Yersinia. Individuals with inherited HLA-B27 are at increased risk of developing reactive arthritis after sexual contact or exposure to certain enteric pathogens, supporting the likelihood of a genetic predisposition.