CHAPTER 43 Phase I Periodontal Therapy

Phase I therapy is the first in the chronologic sequence of procedures that constitute periodontal treatment. The objective is to alter or eliminate the microbial etiology and factors that contribute to gingival and periodontal diseases to the greatest extent possible, therefore halting the progression of disease and returning the dentition to a state of health and comfort.1 Phase I therapy is referred to by a number of names, including initial therapy,1 nonsurgical periodontal therapy,13 cause-related therapy,9 and the etiotropic phase of therapy.21 All terms refer to the procedures performed to treat gingival and periodontal infections, up to and including tissue reevaluation, which is the point at which the course of ongoing care is determined.

Rationale

During phase I, therapy includes the initiation of a comprehensive daily plaque control regimen, thorough removal of calculus and microbial plaque, correction of defective restorations, and treatment of carious lesions.2,4,8,10,16 These procedures are a required part of periodontal therapy, regardless of the extent of disease present. In many cases, phase I therapy will be the only set of procedures required to restore periodontal health, or they will constitute the preparatory phase for surgical therapy. Figures 43-1 and 43-2 show the results of phase I therapy in two patients with chronic periodontitis.

Figure 43-1 Results of phase I therapy, severe chronic periodontitis. A, 45-year-old patient with deep probe depths, bone loss, severe swelling, and redness of the gingival tissues. B, Results 3 weeks after the completion of phase I therapy. Note that the gingival tissue has returned to a normal contour, with redness and swelling dramatically reduced.

Figure 43-2 Results of phase I therapy, moderate chronic periodontitis. A, 52-year-old patient with moderate attachment loss and probe depths in the 4- to 6-mm range. Note that the gingiva appears pink because it is fibrotic. Inflammation is present in the periodontal pockets but disguised by the fibrotic tissue. Bleeding occurs on probing. B, Lingual view of the patient with more visible inflammation and heavy calculus deposits. C and D, 18 months after phase I therapy the same areas show significant improvement in gingival health. The patient returned for regular maintenance visits at 4-month intervals.

Phase I therapy is a critical aspect of periodontal treatment. Data from clinical research indicate that the long-term success of periodontal treatment depends predominantly on maintaining the results achieved with phase I therapy and much less on any specific surgical procedures. In addition, phase I therapy provides an opportunity for the dentist to evaluate tissue response and patient motivation about periodontal care, both of which are crucial elements to the overall success of treatment.

Based on the knowledge that microbial plaque is the major etiologic agent in gingival inflammation, one specific aim of phase I therapy for every patient is effective daily plaque removal at home. These plaque control procedures can be complex, time consuming, and often require changing long-standing habits. Good oral hygiene is most easily accomplished if the tooth surfaces are free of calculus deposits and other irregularities so that surfaces are easily accessible. Therefore, in addition to teaching periodontal patients adequate home plaque control procedures, management of contributing local factors includes the following therapies, as required:

Treatment Sessions

After careful analysis and diagnosis of the specific periodontal condition present, the dentist must develop a treatment plan that includes all required procedures and estimates the number of appointments necessary to complete phase I therapy. In most cases, patients require several treatment sessions for the complete debridement of tooth surfaces. Sometimes carious lesions and other contributing factors have to be controlled before an accurate estimate can be made. All of the conditions listed in the following must be considered when determining and developing the phase I treatment plan13:

Sequence of Procedures

Step 1: Plaque Control Instruction

Plaque control is the essential component to successful periodontal therapy, and instruction should begin in the first treatment appointment. The patient must learn to correctly brush the teeth, focusing on applying the bristles at the gingival third of the clinical crowns of the teeth, and begin using floss or other aids for interdental cleaning. This is sometimes referred to as “targeted oral hygiene”18 and emphasizes thorough plaque removal around the periodontal tissues. The multiple appointment approach to phase I therapy permits the dentist to evaluate, reinforce, and improve the patient’s oral hygiene skills. (Chapter 44 details plaque control options.)

Step 2. Removal of Supragingival and Subgingival Calculus

Removal of calculus is accomplished using scalers, curettes, ultrasonic instrumentation, or combinations of these devices during one or more appointments. Evidence suggests that the treatment results for chronic periodontitis are similar for all instruments,6 and some dentists now incorporate laser technology into periodontal therapy, including phase I therapy.3,15

Step 3. Recontouring Defective Restorations and Crowns

Corrections for restorative defects, which are plaque traps, may be made by smoothing surfaces and overhangs with burs or hand instruments or by replacing restorations. These procedures can be completed concurrently with other phase I procedures.

Step 4. Management of Carious Lesions

Removal of the carious tissue and placement with either temporary or permanent restorations is indicated in phase I therapy because of the infectious nature of the caries process. Healing of the periodontal tissues will be maximized by removing the reservoir of bacteria in these lesions so that they cannot repopulate the microbial plaque.

Step 5. Tissue Reevaluation

After scaling, root planing, and other phase I procedures, the periodontal tissues require approximately 4 weeks to heal sufficiently to be probed accurately. Patients also need the opportunity to improve their plaque control skills to both reduce inflammation and adopt new habits. At the reevaluation appointment, periodontal tissues are probed, and all related anatomic conditions are carefully evaluated to determine if further treatment, including periodontal surgery, is indicated. Additional improvement from periodontal surgical procedures can be expected only if phase I therapy resulted in the gingiva being free of overt inflammation and the patient has learned effective daily plaque control.

Results

Scaling and root planing therapy has been studied extensively to evaluate its effects on periodontal disease. Countless studies indicated that this treatment is both effective and reliable. Studies ranging from 1 month to 2 years in length demonstrated up to 80% reduction in bleeding on probing and mean probing depth reductions of 2 to 3 mm. Others demonstrated that the percentage of periodontal pockets of 4-mm or greater depth was reduced more than 50% and up to 80%.4 Figures 43-1 and 43-2 show examples of the effectiveness of phase I therapy.

The control of infectious organisms during phase I treatment is of critical importance. Recently, there has been considerable interest in providing phase I therapy in one long appointment or two appointments on consecutive days while the patient is receiving an aggressive prescribed regimen of antimicrobial agents rather than staged appointments to treat one quadrant or sextant at a time, usually with 1 week separating appointments. This single-stage treatment sequence has been referred to as “antiinfective” or “disinfection” treatment.11,14 Recent studies suggested both the one appointment and staged or multiple appointment treatment strategies work well. The modest differences in clinical parameters in comparing healing after one session or multiple sessions were not clinically significant.7,17 In addition, microbial parameters were not significantly different after 8 months, regardless of treatment modality17 and the risk of recurrence of periodontal pockets was no greater for either modality.20 Until evidence indicates otherwise, the sequence and duration of phase I therapy appointments should be determined based on amount of disease present and patient comfort.5 Staged therapy permits the advantage of evaluating and reinforcing oral hygiene care, and the one or two appointment therapies can be more efficient in reducing the number of office visits the patient is required to attend.

Additional individual treatments, such as caries control and correction of poorly fitting restorations, clearly augment the healing gained through good plaque control and scaling and root planing by making tooth surfaces accessible to cleaning procedures. Figure 43-3 demonstrates the effects of an overhanging amalgam restoration on gingival inflammation in an otherwise healthy periodontium. Maximal healing from phase I treatment is not possible when local conditions retain plaque and provide reservoirs for repopulation of periodontal pathogens.

Figure 43-3 Effects of overhanging amalgam margin on interproximal gingiva of maxillary first molar in otherwise healthy mouth. A, Clinical appearance of rough, irregular, and overcontoured amalgam. B, Gentle probing of interproximal pocket. C, Extensive bleeding elicited by gentle probing indicating severe inflammation in the area.

Healing

Healing of the gingival epithelium consists of the formation of a long junctional epithelium rather than new connective tissue attachment to the root surfaces. The attachment epithelium reappears 1 to 2 weeks after therapy. Gradual reductions in inflammatory cell population, crevicular fluid flow, and repair of connective tissue result in decreased clinical signs of inflammation, including less redness and swelling. One or two millimeters of recession is often apparent as the result of tissue shrinkage.4

Transient root sensitivity frequently accompanies the healing process. Although evidence suggests that relatively few teeth in a few patients become highly sensitive, this development is common and can be disconcerting to patients. The extent of the sensitivity can be diminished through good plaque removal.19 Warning patients about these potential outcomes, the teeth appearing longer because of shrinkage of periodontal tissues and tooth root sensitivity, at the beginning of the treatment sequence will avoid surprise if these changes occur. Unexpected and possibly uncomfortable consequences to treatment may result in distrust and loss of motivation to continue therapy.

Decision to Refer for Specialist Treatment

Often, periodontal conditions heal sufficiently well after phase I therapy that no further treatment is required beyond routine maintenance, making treatment of most periodontal patients the responsibility of the general dentist. However, advanced or complicated cases benefit from specialist care. It is critical to be skilled in determining which patients would benefit from specialist care and should be referred.12,16

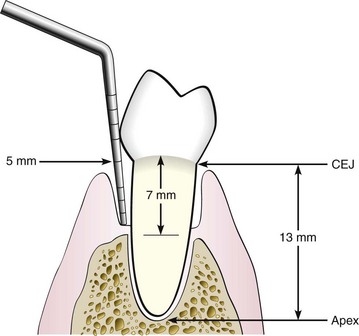

The 5-mm standard has been commonly used as a guideline for identifying candidates for referral and relates to the presence of 5 mm or more of clinical attachment loss present at the reevaluation appointment. The rationale behind the 5-mm standard is that the typical root length is about 13 mm and the crest of the alveolar bone is at a level approximately 2 mm apical to the bottom of the pocket. When there is 5 mm of clinical attachment loss the crest of bone is about 7 mm apical to the cementoenamel junction, therefore only about half the bony support for the tooth remains. Specialist care can help preserve teeth in these cases by eliminating deep pockets and regenerating support for the tooth. Figure 43-4 depicts the relationship of clinical attachment loss to tooth support. In terms of probing depths, the treatment of periodontal diseases is generally successful in patients with 6- to 8-mm probe depths. Success rates diminish when probing depths are 9 mm or greater, so early referral of advanced cases is likely to provide the best results.

Figure 43-4 The 5-mm standard for referral to a periodontist is based on root length, probing depth, and clinical attachment loss. The standard serves as a reasonable guideline to analyze the case for referral for specialist care. CEJ, Cementoenamel junction.

(Redrawn with permission from Armitage G, editor: Periodontal maintenance therapy, Berkeley, Calif, 1974, Praxis.)

In addition to the 5-mm standard and evaluation of probe depths, the following factors must also be considered in the decision to refer:

Every patient is unique, and the decision process for each patient is complex. The considerations presented in this chapter should provide guidance understanding the significance of phase I therapy and in making referral decisions.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

The major goal of phase I therapy is to control the factors responsible for the periodontal inflammation; the removal of subgingival bacterial deposits and the subsequent control of plaque levels by patients are particularly significant. Phase I therapy should be comprehensive and include scaling, root planing, and oral hygiene instruction, as well as other therapies such as caries control, replacement of defective restorations, occlusal therapy, orthodontic movement, and smoking cessation. Comprehensive reevaluation after phase I therapy is essential to validate treatment options and to estimate prognosis. Many patients can have their periodontal disease controlled with phase I therapy and not require further surgical intervention. In patients who do need surgical treatment, phase I therapy is advantageous in that it also provides tissue with reduced inflammatory infiltration, thus improving the surgical management of the tissue and improving the healing response.

For patients with 5 mm or more of attachment loss and with pockets present after phase I treatment, surgical treatment should be planned. Advanced cases may be best treated by periodontal specialists.

Those patients who do not demonstrate the ability to have 20% or less of tooth surfaces free of plaque are poor candidates for successful surgical outcomes and should be closely monitored on a recall maintenance program until plaque control is established.

1 American Academy of Periodontology, Ad Hoc Committee on the Parameters of Care: Phase I therapy. J Periodontol. 2000;71(suppl):856.

2 Axelsson P, Lindhe J. The effect of a preventive programme on dental plaque, gingivitis and caries in school children: results after one and two years. J Clin Periodontol. 1974;1:126.

3 Cobb CM. Lasers in periodontics: a review of the literature. J Periodontol. 2006;77:545.

4 Cobb CM. Non-surgical pocket therapy: mechanical. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:443.

5 Eberhard J, Jepsen S, Jervoe-Storm P-M, et al. Full mouth disinfection for the treatment of adult chronic periodontitis. Cochrane Collaboration Review. www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab004622.html. June 27, 2009

6 Ioannou I, Dimitriadis N, Papadimitriou K, et al. Hand instrumentation versus ultrasonic debridement in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: a rendomized clinical and microbiological trial. J Clin Perio. 2009;36:132.

7 Lang N, Tan WC, Krahenmann MA, Zwahlen M. A systematic review of the effects of full-mouth debridement with and without antiseptics in patients with chronic periodontitis. J Clin Perio. 2008;35:8.

8 Lightner LM, O’Leary TJ, Drake RB, et al. Preventive periodontics treatment procedures: results over 46 months. J Periodontol. 1971;42:555.

9 Lindhe J. Textbook of clinical periodontology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1983.

10 Lindhe J, Kock G. The effect of supervised oral hygiene on the gingiva of children: progression and inhibition of gingivitis. J Periodontal Res. 1966;1:260.

11 Mongardini C, van Steenberghe D, Dekeyser C, et al. One stage full- versus partial-mouth disinfection in the treatment of chronic adult or generalized early-onset periodontitis. I. Long-term clinical observations. J Periodontol. 1999;70:632.

12 Parr RW, Pipe P, Watts T. Shall I refer? In Armitage G, editor: Periodontal maintenance therapy, ed 2, Berkeley, Calif: Praxis, 1982.

13 Perry DA, Beemsterboer PB. Periodontology for the dental hygienist, ed 3. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007.

14 Quirynen M, Mongardini C, Pauwels M, et al. One stage full- versus partial-mouth disinfection in the treatment of chronic adult or generalized early-onset periodontitis. II. Long-term impact on microbial load. J Periodontol. 1999;70:646.

15 Romanos GE. Letter to editor: re: lasers in periodontics. J Periodontol. 2007;78:595.

16 Suomi JD, Greene JC, Vermillion JR, et al. The effect of controlled oral hygiene procedures on the progression of periodontal disease in adults: results after third and final year. J Periodontol. 1971;42:152.

17 Swierkot K, Nonnenmacher CI, Mutters R, et al. One-stage full-mouth disinfection versus quadrant and full-mouth root planing. J Clin Perio. 2009;36:240.

18 Takei H: Personal communication. 2009.

19 Tommaro S, Wennstrom JL, Bergenholtz G. Root-dentin sensitivity following non-surgical periodontal treatment. J Clin Perio. 2001;27:690.

20 Tomasi C, Bertelle A, Dellasega E, Wennstrom JL. Full-mouth ultrasonic debridement and risk of disease recurrence: a 1-year follow-up. J Clin Perio. 2006;33:626.

21 Wilkins EM. Clinical practice of the dental hygienist. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1989.

Suggested Readings

2000 American Academy of Periodontology, Ad Hoc Committee on the Parameters of Care: Phase I therapy. J Periodontol. 2000;71(suppl):856.

Axelsson P, Lindhe J. The effect of a preventive programme on dental plaque, gingivitis and caries in school children: results after one and two years. J Clin Periodontol. 1974;1:126.

Cobb CM. Non-surgical pocket therapy: mechanical. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:443.

Ioannou I, Dimitriadis N, Papadimitriou K, et al. Hand instrumentation versus ultrasonic debridement in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: a randomized clinical and microbiological trial. J Clin Perio. 2009;36:132.

Lang N, Tan WC, Krahenmann MA, Zwahlen M. A systematic review of the effects of full-mouth debridement with and without antiseptics in patients with chronic periodontitis. J Clin Perio. 2008;35:8.

Suomi JD, Greene JC, Vermillion JR, et al. The effect of controlled oral hygiene procedures on the progression of periodontal disease in adults: results after third and final year. J Periodontol. 1971;42:152.

Tommaro S, Wennstrom JL, Bergenholtz G. Root-dentin sensitivity following non-surgical periodontal treatment. J Clin Perio. 2001;27:690.

Tomasi C, Bertelle A, Dellasega E, Wennstrom JL. Full-mouth ultrasonic debridement and risk of disease recurrence: a 1-year follow-up. J Clin Perio. 2006;33:626.