CHAPTER 54 General Principles of Periodontal Surgery

All surgical procedures should be carefully planned. The patient should be adequately prepared medically, psychologically, and practically for all aspects of the intervention. This chapter covers the preparation of the patient and the general considerations common to all periodontal surgical techniques. Complications that may occur during or after surgery are also discussed.

Surgical periodontal procedures are usually performed in the dental office. Hospital periodontal surgery is discussed later in this chapter, followed by a review of common surgical instruments.

Outpatient Surgery

Patient Preparation

Reevaluation after Phase I Therapy

Almost every patient undergoes the so-called initial or preparatory phase of therapy, which basically consists of thorough scaling and root planing and removing all irritants responsible for the periodontal inflammation. These procedures (1) eliminate some lesions entirely; (2) render the tissues more firm and consistent, thus permitting a more accurate and delicate surgery; and (3) acquaint the patient with the office and the operator and assistants, thereby reducing the patient’s apprehension and fear.

The reevaluation phase consists of reprobing and reexamining all the pertinent findings that previously indicated the need for the surgical procedure. Persistence of these findings confirms the indication for surgery. The number of surgical procedures, expected outcome, and postoperative care necessary are all decided before therapy. These are discussed with the patient, and a final decision is made, incorporating any necessary adjustments to the original plan.

Premedication*

For patients who are not medically compromised, the value of administering antibiotics routinely for periodontal surgery has not been clearly demonstrated.29 However, some studies have reported reduced postoperative complications, including reduced pain and swelling, when antibiotics are given before periodontal surgery and continued for 4 to 7 days after surgery.4,12,21,32

The prophylactic use of antibiotics in patients who are otherwise healthy has been advocated for bone-grafting procedures and purported to enhance the chances of new attachment. Although the rationale for such use appears logical, no research evidence is available to support it. In any case, the risks inherent in the administration of antibiotics should be evaluated together with the potential benefits. Other presurgical medications include administration of a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) such as ibuprofen (Motrin) 1 hour before the procedure and an oral rinse with 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate (Peridex, PerioGard).38

Smoking

The deleterious effect of smoking on healing of periodontal wounds has been amply documented20,33,43 (see Chapter26). Patients should be clearly informed of this fact and asked to quit or stop smoking for a minimum of 3 to 4 weeks after the procedure. For patients who are unwilling to follow this advice, an alternate treatment plan that does not include more sophisticated techniques (e.g., regenerative, mucogingival, esthetic) should be considered.

Informed Consent

The patient should be informed at the initial visit about the diagnosis, prognosis, and different possible treatments, with their expected results and all pros and cons of each approach. At surgery the patient should again be informed, verbally and in writing, of the procedure to be performed, and he or she should indicate agreement by signing the consent form.

Emergency Equipment

The operator, all assistants, and office personnel should be trained to handle all the possible emergencies that may arise. Drugs and equipment for emergency use should be readily available at all times.

The most common emergency is syncope, or a transient loss of consciousness caused by a reduction in cerebral blood flow. The most common cause is fear and anxiety. Syncope is usually preceded by a feeling of weakness, and then the patient develops pallor, sweating, coldness of the extremities, dizziness, and slowing of the pulse. The patient should be placed in a supine position with the legs elevated; tight clothes should be loosened and a wide-open airway ensured. Administration of oxygen is also useful. Unconsciousness persists for a few minutes. A history of previous syncopal attacks during dental appointments should be explored before treatment is begun, and if these are reported, extra efforts to relieve the patient’s fear and anxiety should be made. The reader is referred to other texts for a complete analysis of this important topic.3

Measures to Prevent Transmission of Infection

The danger of transmitting infections to the dental team or other patients has become apparent in recent years, particularly with the threat of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Universal precautions, including protective attire, and barrier techniques are strongly recommended and often required by law. These include the use of disposable sterile gloves, surgical masks, and protective eyewear. All surfaces possibly contaminated with blood or saliva that cannot be sterilized (e.g., light handles, unit syringes) must be covered with aluminum foil or plastic wrap. Aerosol-producing devices (e.g., Cavitron) should not be used on patients with suspected infections, and their use should be kept to a minimum in all other patients. Special care should be taken when using and disposing of sharp items such as needles and scalpel blades.

Sedation and Anesthesia

Periodontal surgery should be performed painlessly. The patient should be assured of this at the outset and throughout the procedure. The most reliable means of providing painless surgery is the effective administration of local anesthesia. The area to be treated should be thoroughly anesthetized by means of regional block and local infiltration. Injections directly into the interdental papillae may also be helpful.

Apprehensive and neurotic patients require special management with antianxiety or sedative-hypnotic agents. Modalities for the administration of these agents include inhalation, oral, intramuscular, and intravenous routes. The specific agents and modality of administration are based on the desired level of sedation, anticipated length of the procedure, and overall condition of the patient. Specifically, the patient’s medical history and physical and emotional status should be considered when selecting agents and techniques.

Perhaps the simplest, least invasive method to alleviate anxiety in the dental office is nitrous oxide and oxygen inhalation sedation. For many individuals, this is quite effective. Advantages include a quick onset of action, the ability to adjust the level of sedation throughout the procedure, a rapid recovery, and little or no concern for postoperative impairment of sensory or motor function. One disadvantage is that a small percentage of patients will not achieve the desired effect. This is especially true for the mentally impaired individual because nitrous oxide and oxygen sedation requires some level of patient cooperation. Overall, inhalation sedation with nitrous oxide and oxygen is a safe, effective, and reliable means of reducing mild anxiety.

For individuals with mild-to-moderate anxiety, oral administration of a benzodiazepine can be effective in decreasing anxiety and producing a level of relaxation. Oral administration of a sedative agent can be more effective than inhalation anesthesia because the level of sedation achieved may be more profound. Disadvantages of oral sedative administration include incomplete recovery, an inability to control the level of sedation, and a prolonged period of impaired sensory and motor skills. A variety of benzodiazepine agents are available for oral administration (see Chapter 55).

Intravenous (IV) administration of a benzodiazepine, alone or in combination with other agents, can be used to achieve a greater level of sedation in individuals with moderate to severe levels of anxiety. Furthermore, the onset of action of IV sedation is almost immediate, and the level of sedation can be titrated on an individual basis to the desired effect. The recovery period depends on the half-life of the agent used and the amount given. The operator should receive formal training in the techniques of sedation; this often is required by law. A thorough understanding of the indications, contraindications, and risks of these agents is required.3 The reader is referred to Chapter 55 and other texts for a more detailed discussion of conscious sedation modalities, agents, and techniques.26

Tissue Management

Scaling and Root Planing

Although scaling and root planing have been performed previously as part of Phase I therapy, all exposed root surfaces should be carefully explored and planed as needed as part of the surgical procedure. In particular, areas of difficult access, such as furcations or deep pockets, often have rough areas or even calculus that was undetected during the preparatory sessions. The assistant who is retracting the tissues and using the aspirator should also check for the presence of calculus and the smoothness of each surface from a different angle.

Hemostasis

Hemostasis is an important aspect of periodontal surgery because good intraoperative control of bleeding permits an accurate visualization of the extent of disease, pattern of bone destruction, and anatomy and condition of the root surfaces. It provides the operator with a clear view of the surgical site, which is essential for wound debridement and scaling and root planing. In addition, good hemostasis also prevents excessive loss of blood into the mouth, oropharynx, and stomach.

Periodontal surgery can produce profuse bleeding, especially during the initial incisions and flap reflection. After flap reflection and removal of granulation tissue, bleeding disappears or is considerably reduced. Typically, control of intraoperative bleeding can be managed with aspiration. Continuous suctioning of the surgical site with an aspirator is indispensable for performing periodontal surgery. Application of pressure to the surgical wound with moist gauze can be a helpful adjunct to control site-specific bleeding. Intraoperative bleeding that is not controlled with these simple methods may indicate a more serious problem and require additional control measures.

Excessive hemorrhaging after initial incisions and flap reflection may be caused by laceration of venules, arterioles, or larger vessels. Fortunately, the laceration of medium or large vessels is rare because incisions near highly vascular anatomic areas, such as the posterior mandible (lingual and inferior alveolar arteries) and the posterior, midpalatal regions (greater palatine arteries), are avoided in incision and flap design. Proper design of the flaps, taking into consideration these areas, avoids accidents (see Chapter 53). However, even when all anatomic precautions are taken, it is possible to cause bleeding from medium or large vessels because anatomic variations do occur and may result in inadvertent laceration. If a medium or large vessel is lacerated, a suture around the bleeding end may be necessary to control hemorrhage. Pressure should be applied through the tissue to determine the location that will stop blood flow in the severed vessel. Then a suture can be passed through the tissue and tied to restrict blood flow. Excessive bleeding from a surgical wound also may result from incisions across a capillary plexus. Minor areas of persistent bleeding from capillaries can be stopped by applying cold pressure to the site with moist gauze (soaked in sterile ice water) for several minutes.

The use of a local anesthetic with a vasoconstrictor may also be useful in controlling minor bleeding from the periodontal flap. Both these methods act through vasoconstriction, thus reducing the flow of blood through incised small vessels and capillaries. This action is relatively short-lived and should not be relied on for long-term hemostasis. It is important to avoid the use of vasoconstrictors to control bleeding before sending a patient home. If a more serious bleeding problem exists or a firm blood clot is not established, bleeding is likely to recur when the vasoconstrictor has metabolized and the patient is no longer in the office.

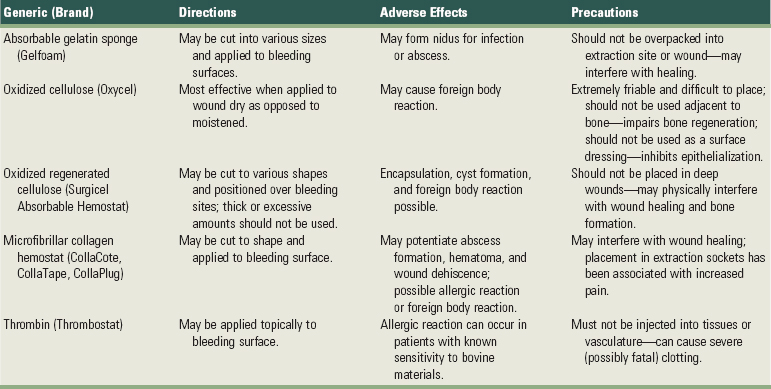

For slow, constant blood flow and oozing, hemostasis may be achieved with hemostatic agents. Absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam), oxidized cellulose (Oxycel), oxidized regenerated cellulose (Surgicel Absorbable Hemostat), and microfibrillar collagen hemostat (CollaCote, CollaTape, CollaPlug) are useful hemostatic agents for the control of bleeding in capillaries, small blood vessels, and deep wounds (Table 54-1).

Absorbable gelatin sponge is a porous matrix prepared from pork skin that helps stabilize a normal blood clot. The sponge can be cut to the desired dimensions and either sutured in place or positioned within the wound (e.g., extraction socket). It is absorbed in 4 to 6 weeks.

Oxidized cellulose is a chemically modified form of surgical gauze that forms an artificial clot. The material is friable and can be difficult to keep in place. It absorbs in 1 to 6 weeks.

Oxidized regenerated cellulose is prepared from cellulose by reaction with alkali to form a chemically pure, more uniform structure than oxidized cellulose. The material is prepared in a cloth or thin gauze form that can be cut to the desired size and sutured or layered on the bleeding surface. It can be used as a surface dressing because it does not impair epithelialization, and it is bactericidal against many gram-negative and -positive microorganisms, both aerobic and anaerobic. Caution should be used when wounds are infected or have an increased potential to becoming infected (e.g., immunocompromised patients) because the absorbable hemostatic agents can serve as a nidus for infection.

Thrombin is a drug capable of hastening the process of blood clotting. It is intended for topical use only because it is applied as a liquid or powder. Thrombin should never be injected into tissues because it can cause serious, even fatal intravascular coagulation. Also, because thrombin is a bovine-derived material, caution should be used for any patient with known allergic reaction to bovine products.

Finally, it is imperative to recognize that excessive bleeding may be caused by systemic disorders, including (but not limited to) platelet deficiencies, coagulation defects, medications, and hypertension. As a precaution, all surgical patients should be asked about current medications that may contribute to bleeding, any family history of bleeding disorders, and hypertension. All patients, regardless of health history, should have their blood pressure evaluated before surgery, and anyone diagnosed with hypertension must be advised to see a physician before surgery. Patients with known or suspected bleeding deficiencies or disorders must be carefully evaluated before any surgical procedure. A consultation with the patient’s physician is recommended, and laboratory tests should be done to assess the risk of bleeding. It may be necessary to refer the patient to a hematologist for a comprehensive workup.

Periodontal Dressings (Periodontal Packs)

In most cases, after the surgical periodontal procedures are completed, the area is covered with a surgical pack. In general, dressings have no curative properties; they assist healing by protecting the tissue rather than providing “healing factors.” The pack minimizes the likelihood of postoperative infection and hemorrhage, facilitates healing by preventing surface trauma during mastication, and protects against pain induced by contact of the wound with food or the tongue during mastication. (For a complete literature review on this subject, see Sachs et al.37)

Zinc Oxide–Eugenol Packs

Packs based on the reaction of zinc oxide and eugenol include the Wondr-Pak developed by Ward46 in 1923 and several other packs that use modified forms of Ward’s original formula. The addition of accelerators, such as zinc acetate, gives the dressing a better working time.

Zinc oxide–eugenol dressings are supplied as a liquid and powder that are mixed before use. Eugenol in this type of pack may induce an allergic reaction that produces reddening of the area and burning pain in some patients.

Noneugenol Packs

The reaction between a metallic oxide and fatty acids is the basis for Coe-Pak, which is the most widely used dressing in the United States. This is supplied in two tubes, the contents of which are mixed immediately before use until a uniform color is obtained. One tube contains zinc oxide, an oil (for plasticity), a gum (for cohesiveness), and Lorothidol (a fungicide); the other tube contains liquid coconut fatty acids thickened with colophony resin (or rosin) and chlorothymol (a bacteriostatic agent).37,40 This dressing does not contain asbestos or eugenol, thereby avoiding the problems associated with these substances.

Other noneugenol packs include cyanoacrylates6,19,24 and tissue conditioners (methacrylate gels).2 However, these are not in common use.

Retention of Packs

Periodontal dressings are usually kept in place mechanically by interlocking in interdental spaces and joining the lingual and facial portions of the pack. In isolated teeth or when several teeth in an arch are missing, retention of the pack may be difficult. Numerous reinforcements and splints and stents for this purpose have been described.17,18,47 Placement of dental floss tied loosely around the teeth enhances retention of the pack.

Antibacterial Properties of Packs

Improved healing and patient comfort with less odor and taste6 have been obtained by incorporating antibiotics in the pack. Bacitracin,5 oxytetracycline (Terramycin),13 neomycin, and nitrofurazone have been tried, but all may produce hypersensitivity reactions. The emergence of resistant organisms and opportunistic infection has been reported.35 Incorporation of tetracycline powder in Coe-Pak is generally recommended, particularly when long and traumatic surgeries are performed.

Preparation and Application of Dressing

Zinc oxide packs are mixed with eugenol or noneugenol liquids on a wax paper pad with a wooden tongue depressor. The powder is gradually incorporated with the liquid until a thick paste is formed.

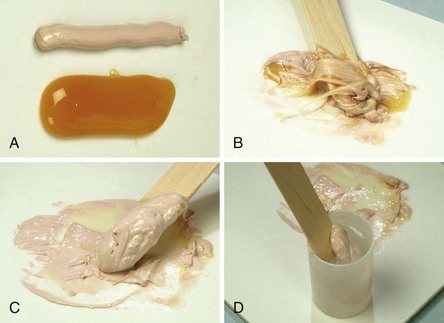

Coe-Pak is prepared by mixing equal lengths of paste from tubes containing the accelerator and the base until the resulting paste is a uniform color (Figure 54-1, A to C). A capsule of tetracycline powder can be added at this time. The pack is then placed in a cup of water at room temperature (Figure 54-1, D). In 2 to 3 minutes the paste loses its tackiness and can be handled and molded; it remains workable for 15 to 20 minutes. Working time can be shortened by adding a small amount of zinc oxide to the accelerator (pink paste) before spatulating.

Figure 54-1 Preparing the surgical pack (Coe-Pak). A, Equal lengths of the two pastes are placed on a paper pad. B, Pastes are mixed with a wooden tongue depressor for 2 or 3 minutes until the paste loses its tackiness (C). D, Paste is placed in a paper cup of water at room temperature. With lubricated fingers, it is then rolled into cylinders and placed on the surgical wound.

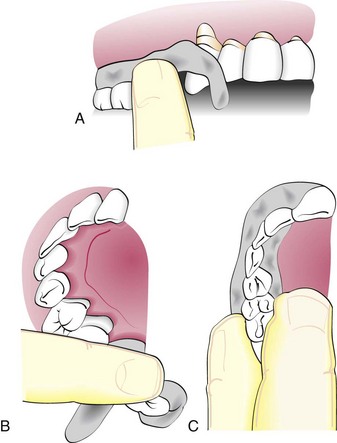

The pack is then rolled into two strips approximately the length of the treated area. The end of one strip is bent into a hook shape and fitted around the distal surface of the last tooth, approaching it from the distal surface (Figure 54-2, A). The remainder of the strip is brought forward along the facial surface to the midline and gently pressed into place along the gingival margin and interproximally. The second strip is applied from the lingual surface. It is joined to the pack at the distal surface of the last tooth, then brought forward along the gingival margin to the midline (Figure 54-2, B). The strips are joined interproximally by applying gentle pressure on the facial and lingual surfaces of the pack (Figure 54-2, C). For isolated teeth separated by edentulous spaces, the pack should be made continuous from tooth to tooth, covering the edentulous areas (Figure 54-3).

Figure 54-2 Inserting the periodontal pack. A, Strip of pack is hooked around the last molar and pressed into place anteriorly. B, Lingual pack is joined to the facial strip at the distal surface of the last molar and fitted into place anteriorly. C, Gentle pressure on the facial and lingual surfaces joins the pack interproximally.

When split flaps have been performed, the area should be covered with tin foil to protect the sutures before placing the pack (see Chapter 54).

The pack should cover the gingiva, but overextension onto uninvolved mucosa should be avoided. Excess pack irritates the mucobuccal fold and floor of the mouth and interferes with the tongue. Overextension also jeopardizes the remainder of the pack because the excess tends to break off, taking pack from the operated area with it. Pack that interferes with the occlusion should be trimmed away before the patient is dismissed (Figure 54-4). Failure to do this causes discomfort and jeopardizes retention of the pack.

The operator should ask the patient to move the tongue forcibly out and to each side, and the cheek and lips should be displaced in all directions to mold the pack while it is still soft. After the pack has set, it should be trimmed to eliminate all excess.

As a general rule, the pack is kept on for 1 week after surgery. This guideline is based on the usual timetable of healing and clinical experience. It is not a rigid requirement; the period may be extended, or the area may be repacked for an additional week.

Fragments of the surface of the pack may come off during the week, but this presents no problem. If a portion of the pack is lost from the operated area and the patient is uncomfortable, it is usually best to repack the area. The clinician should remove the remaining pack, wash the area with warm water, and apply a topical anesthetic before replacing the pack, which is then retained for 1 week. Again, the patient may develop pain from an overextended margin that irritates the vestibule, floor of the mouth, or tongue. The excess pack should be trimmed away, making sure that the new margin is not rough, before the patient is dismissed.

Postoperative Instructions

After the pack is placed, printed instructions are given to the patient to be read before he or she leaves the chair (Box 54-1).

BOX 54-1 Patient Instructions after Periodontal Surgery

Instructions for _____________ (Patient’s Name)

The following information on your gum operation has been prepared to answer questions you may have about how to take care of your mouth. Please read the instructions carefully; our patients have found them very helpful.

Although there will be little or no discomfort when the anesthesia wears off, you should take two acetaminophen (Tylenol) tablets every 6 hours for the first 24 hours. After that, take the same medication if you have some discomfort. Do not take aspirin because this may increase bleeding.

We have placed a periodontal pack over your gums to protect them from irritation. The pack prevents pain, aids healing, and enables you to carry on most of your usual activities in comfort. The pack will harden in a few hours, after which it can withstand most of the forces of chewing without breaking off. It may take a little while to become accustomed to it.

The pack should remain in place until it is removed in the office at the next appointment. If particles of the pack chip off during the week, do not be concerned as long as you do not have pain. If a piece of the pack breaks off and you are in pain, or if a rough edge irritates your tongue or cheek, please call the office. The problem can be easily remedied by replacing the pack.

For the first 3 hours after the operation, avoid hot foods to permit the pack to harden. It is also convenient to avoid hot liquids during the first 24 hours. You can eat anything you can manage, but try to chew on the nonoperated side of your mouth. Semisolid or finely minced foods are suggested. Avoid citrus fruits or fruit juices, highly spiced foods, and alcoholic beverages; these will cause pain. Food supplements or vitamins are generally not necessary.

Do not smoke. The heat and smoke will irritate your gums, and the immunologic effects of nicotine will delay healing and prevent a completely successful outcome of the procedure performed. If possible, use this opportunity to give up smoking. In addition to all other well-known health risks, smokers have more gum disease than nonsmokers.

Do not brush over the pack. Brush and floss the areas of the mouth not covered by the pack as you normally do. Use chlorhexidine (Peridex, PerioGard) oral rinses after brushing (the prescription for this rinse has been given to you).

During the first day, apply ice intermittently on the face over the operated area. It is also beneficial to suck on ice chips intermittently during the first 24 hours. These methods will keep tissues cool and reduce inflammation and swelling.

You may experience a slight feeling of weakness or chills during the first 24 hours. This should not be cause for alarm but should be reported at the next visit. Follow your regular daily activities, but avoid excessive exertion of any type. Golf, tennis, skiing, bowling, swimming, or sunbathing should be postponed for a few days after the operation.

Swelling is not unusual, particularly in areas that required extensive surgical procedures. The swelling generally begins 1 to 2 days after the operation and subsides gradually in 3 or 4 days. If this occurs, apply moist heat over the operated area. If the swelling is painful or appears to become worse, please call the office.

Occasionally, blood may be seen in the saliva for the first 4 or 5 hours after the operation. This is not unusual and will correct itself. If there is considerable bleeding beyond this, take a piece of gauze, form it into the shape of a U, hold it in the thumb and index finger, apply it to both sides of the pack, and hold it there under pressure for 20 minutes. Do not remove it during this period to examine it. If the bleeding does not stop at the end of 20 minutes, please contact the office. Do not try to stop bleeding by rinsing.

After the pack is removed, the gums most likely will bleed more than they did before the operation. This is perfectly normal in the early stage of healing and will gradually subside. Do not stop cleaning because of it. If any other problems arise, please call the office.

First Postoperative Week

Properly performed, periodontal surgery presents no serious postoperative problems. Patients should be told to rinse with 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate (Peridex, PerioGard) immediately after the surgical procedure and twice daily thereafter until normal plaque control technique can be resumed.30,38,45 The following complications may arise in the first postoperative week, although they are the exception rather than the rule:

Removal of Pack and Return Visit

When the patient returns after 1 week, the periodontal pack is taken off by inserting a surgical hoe along the margin and exerting gentle lateral pressure. Pieces of pack retained interproximally and particles adhering to the tooth surfaces are removed with scalers. Particles may be enmeshed in the cut surface and should be carefully picked off with fine cotton pliers. The entire area is rinsed with peroxide to remove superficial debris.

Findings at Pack Removal

The following are usual findings when the pack is removed:

Repacking

After the pack is removed, it is usually not necessary to replace it. However, repacking for an additional week is advised for patients with (1) a low pain threshold who are particularly uncomfortable when the pack is removed, (2) unusually extensive periodontal involvement, or (3) slow healing. Clinical judgment helps in deciding whether to repack the area or leave the initial pack on longer than 1 week.

Mouth Care between Procedures

Care of the mouth by the patient between the treatment of the first and the final areas, as well as after surgery is completed, is extremely important.48 These measures should begin after the pack is removed from the first surgery. The patient has been through a presurgical period of instructed plaque control and should be reinstructed at this time.

Vigorous brushing is not feasible during the first week after the pack is removed. However, the patient is informed that plaque and food accumulation impair healing and is advised to try to keep the area as clean as possible by the gentle use of soft toothbrushes and light water irrigation. Rinsing with a chlorhexidine mouthwash or its topical application with cotton-tipped applicators is indicated for the first few postoperative weeks, particularly in advanced cases. Brushing is introduced when healing of the tissues permits it; the vigor of the overall hygiene regimen is increased as healing progresses. Patients should be told that (1) more gingival bleeding will most likely occur than was present before the procedure, (2) this bleeding is perfectly normal and will subside as healing progresses, and (3) it should not deter them from following their oral hygiene regimen.

Management of Postoperative Pain

Periodontal surgery that follows the basic principles outlined here should produce only minor pain and discomfort.41 One study of 304 consecutive periodontal surgical interventions revealed that 51.3% of the patients reported minimal or no postoperative pain, and only 4.6% reported severe pain. Of these, only 20.1% took 5 or more doses of analgesic.11 The same study showed that mucogingival procedures result in 6 times more discomfort and osseous surgery in 3.5 times more discomfort than plastic gingival surgery. In the few patients who may have severe pain, its control then becomes an important part of patient management.29

A common source of postoperative pain is overextension of the periodontal pack onto the soft tissue beyond the mucogingival junction or onto the frena. Overextended packs cause localized areas of edema, usually noticed 1 to 2 days after surgery. Removal of excess pack is followed by resolution in about 24 hours. Extensive and excessively prolonged exposure and dryness of bone also induce severe pain. For most healthy patients, a preoperative dose of ibuprofen (600 to 800 mg) followed by 1 tablet every 8 hours for 24 to 48 hours is very effective in reducing discomfort after periodontal therapy. Patients are advised to continue taking ibuprofen or change to acetaminophen if needed thereafter. If pain persists, acetaminophen plus codeine (Tylenol #3) can be prescribed. Caution should be used in prescribing or dispensing ibuprofen to patients with hypertension controlled by medications because it can interfere with the effectiveness of the medication. When severe postoperative pain is present, the patient should be seen at the office on an emergency basis. The area is anesthetized by infiltration or topically, the pack is removed, and the wound is examined. Postoperative pain related to infection is accompanied by localized lymphadenopathy and a slight elevation in temperatures.31 It should be treated with systemic antibiotics and analgesics.

Treatment of Sensitive Roots

Root hypersensitivity is a relatively common problem in periodontal practice. It may occur spontaneously when the root becomes exposed as a result of gingival recession or pocket formation, or it may appear after scaling and root planing and surgical procedures (see Curro10 for literature review). It is manifested as pain induced by cold or hot temperature more often cold), by citrus fruits or sweets, or by contact with a toothbrush or a dental instrument.

Root sensitivity occurs more frequently in the cervical area of the root, where the cementum is extremely thin. Scaling and root-planing procedures remove this thin cementum, inducing the hypersensitivity.

Transmission of stimuli from the surface of the dentin to the nerve endings located in the dental pulp or in the pulpal region of the dentin could result from the odontoblastic process or from a hydrodynamic mechanism (displacement of dentinal fluid). The latter process seems more likely and would explain the importance of burnishing desensitizing agents to obturate the dentinal tubule. An important factor for reducing or eliminating hypersensitivity is adequate plaque control. However, hypersensitivity may prevent plaque control, and therefore a vicious cycle of escalating hypersensitivity and plaque accumulation may be created.

Desensitizing Agents

A number of agents have been proposed to control root hypersensitivity. Clinical evaluation of the many agents proposed is difficult because (1) measuring and comparing pain between different persons is difficult, (2) hypersensitivity disappears by itself after a time, and (3) desensitizing agents usually take a few weeks to act.

The patient should be informed about the possibility of root hypersensitivity before treatment is undertaken. The following information on how to cope with the problem should also be given to the patient:

Desensitizing agents can be applied by the patient at home or by the dentist or hygienist in the dental office. The most likely mechanism of action is the reduction in the diameter of the dentinal tubules so as to limit the displacement of fluid in them. According to Trowbridge and Silver,44 this can be attained by (1) formation of a smear layer produced by burnishing the exposed surface, (2) topical application of agents that form insoluble precipitates within the tubules, (3) impregnation of tubules with plastic resins, or (4) sealing of the tubules with plastic resins.

Agents Used by the Patient

The most common agents used by the patient for oral hygiene are dentifrices. Although many dentifrice products contain fluoride, additional active ingredients for desensitization are strontium chloride, potassium nitrate, and sodium citrate. The American Dental Association (ADA) has approved the following dentifrices for desensitizing purposes: Sensodyne and Thermodent, which contain strontium chloride7,9,36; Crest Sensitivity Protection, Denquel, and Promise, which contain potassium nitrate1,9; and Protect, which contains sodium citrate. Fluoride rinsing solutions and gels can also be used after the usual plaque control procedures.42

Patients should be aware that several factors must be considered in the treatment of tooth hypersensitivity, including the history and severity of the problem, as well as the physical findings of the tooth or teeth involved. A proper diagnosis is required before any treatment can be initiated so that pathologic causes of pain (e.g., caries, cracked tooth, pulpitis) can be ruled out before attempting to treat hypersensitivity. Desensitizing agents act through the precipitation of crystalline salts on the dentin surface, which block dentinal tubules. Patients must be aware that their use will not prove to be effective unless used continuously for at least 2 weeks.

Agents Used in the Dental Office

Box 54-2 lists various office treatments for the desensitization of hypersensitive dentin. These products and treatments aim to decrease hypersensitivity by blocking dentinal tubules with either a crystalline salt precipitation or an applied coating (varnish or bonding agent) on the root surface.44

BOX 54-2 From Trowbridge HO, Silver DR: Dent Clin North Am 34:566, 1990.

Office Treatments for Dentinal Hypersensitivity

Several agents have been used to precipitate crystalline salts on the dentin surface in an attempt to occlude the dentinal tubules. Fluoride solutions and pastes historically have been the agents of choice. In addition to their antisensitivity properties, fluoride agents have the advantage of anticaries activity, which is particularly important for patients with a tendency to develop root caries. Certain agents, however, such as chlorhexidine, decrease the ability of fluoride to bind with calcium on the root surfaces.1 Thus it is important to advise patients not to rinse or eat for 1 hour after a desensitizing treatment. Currently, potassium oxalate (Protect) and ferric oxalate (Sensodyne Sealant) solutions are the preferred agents; special applicators have been developed for their use. These agents form insoluble calcium oxalate crystals that occlude the dentinal tubules.27,30

A newer method of treatment for hypersensitive dentin is the use of varnishes or bonding agents to occlude dentinal tubules. Newer restorative materials, such as glass-ionomer cements and the dentin bonding agents, are still under investigation, but when the tooth needs recontouring or difficult cases do not respond to other treatments, the dentist may choose to use a restorative material. Resin primers alone could be promising, but the effects are not permanent, and investigations are ongoing.14 Despite some successes in decreasing dentin hypersensitivity, it is important to note that these “dental office” treatments have not been a predictable means of solving hypersensitivity, and the success achieved is often short-lived. The crystalline salts and varnishes and the sealants can be washed away over time, and hypersensitivity may return. When this occurs, patients can have sensitive root surfaces treated again.

Recently, attempts have been made to improve the success and longevity of these treatments using lasers. Low-level laser “melting” of the dentin surface appears to seal dentinal tubules without damage to the pulp.15,22 in a combined treatment modality, the Nd:YAG laser has been used to congeal fluoride varnish on root surfaces. This in vitro study demonstrated that the laser-treated fluoride varnish resisted removal by electric toothbrushing, with 90% of tubules remaining blocked, whereas in the controls (no laser treatment), the fluoride varnish was almost completely brushed away.23 Despite these convincing preliminary results, more research is needed before laser treatment can be considered an effective and predictable means of desensitization (see Chapter 64).

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

The majority of periodontal surgeries can be carried out solely with thorough application of local anesthesia, but clinicians have the obligation to ensure a patient-centered approach that should include oral, intravenous, and inhalational sedation in their spectrum of available services to be used as needed.

An efficient, precise, and minimally traumatic management of tissues is the way to obtain the best clinical outcomes. All patients need oral analgesic support and should be given the necessary pain-relieving medication so that an effective level of analgesic is present in the immediate postsurgical period and thereafter as needed. The use of longer acting local anesthesia agents, such as bupivacaine, and protective periodontal dressings also helps reduce postsurgical pain.

In the immediate postsurgical weeks, plaque control and healing are enhanced by the use of antimicrobial mouthrinses such as chlorhexidine. Postsurgical root sensitivity is well controlled by ensuring plaque control is optimal, and desensitizing agents will be needed only occasionally.

Hospital Periodontal Surgery

Ordinarily, periodontal surgery is an office procedure performed in quadrants or sextants, usually at biweekly or longer intervals. Under certain circumstances, however, it is in the best interest of the patient to treat the mouth at one surgery with the patient in a hospital operating room under general anesthesia.

Indications

Indications for hospital periodontal surgery include optimal control and management of apprehension, convenience for individuals who cannot endure multiple visits to complete surgical treatment, and patient protection.

Patient Apprehension

Gentleness, understanding, and preoperative sedation usually suffice to calm the fears of most patients. For some patients, however, the prospect of a series of surgical procedures is sufficiently stressful to trigger disturbances that jeopardize their well-being and hamper treatment. Explaining that the treatment at the hospital will be performed painlessly and that it will be accomplished by a level of anesthesia that is neither practical nor safe for patients in a dental office is an important step in allaying their fears. The thought of completing the necessary surgical procedures in one session rather than in repeated visits is an added comfort to the patient because it eliminates the prospect of repeated anxiety in anticipation of each treatment.

Patient Convenience

With complete mouth surgery, there is less stress for the patient and less time involved in postoperative care. For patients whose occupation entails considerable contact with the public, surgery performed at biweekly intervals sometimes presents a significant problem. It means that for several weeks, some area of the mouth will have undergone surgery and may be covered by a periodontal pack. With the complete mouth technique, the surgery is completed in one visit and although the pack may cover the entire treated area, it is usually only retained for 1 week. Patients find this an acceptable alternative to several weeks of discomfort in different areas of the mouth and multiple dressing applications. For a variety of other reasons, patients may prefer to address their surgical needs in one session under optimal “operating room” conditions.

Patient Protection

Some patients have systemic conditions that are not severe enough to contraindicate elective surgery but may require special precautions best provided in a hospital setting. This group includes but is not limited to patients with severe cardiovascular disease, abnormal bleeding tendencies, hyperthyroidism, or uncontrolled hypertension. Treating such a patient in a hospital operating room or equivalent procedure room with an anesthesiologist present to monitor and manage vitals signs and comfort level throughout the surgical procedure is the safest way to manage them.

The purpose of hospitalization is to protect patients by anticipating their special needs, not to perform periodontal surgery when it is contraindicated by the patient’s general condition. For some patients, elective surgery is contraindicated regardless of whether it is performed in the dental office or hospital. When consultation with the patient’s physician leads to this decision, palliative periodontal therapy, in the form of scaling and root planing if permissible, is the necessary compromise.

Patient Preparation

Premedication

Patients should be given a sedative the night before surgery. Benzodiazepines work well for most patients, allowing the patient to sleep well the night before surgery. If the patient is extremely nervous about the procedure, it is also helpful to advise them to take a benzodiazepine on the morning of surgery. This ensures that they will be rested and as relaxed as possible before surgery.

Patients with systemic problems (e.g., history of rheumatic fever, cardiovascular problems) are premedicated as needed (see Chapter 37).

Anesthesia

Local or general anesthesia26 may be used. Local anesthesia is the method of choice, except for especially apprehensive patients. It permits unhampered movement of the head, which is necessary for optimal visibility and accessibility to the various root surfaces. Local anesthesia is used in the same manner as for routine periodontal surgery.

When general anesthesia is indicated, it is administered by an anesthesiologist. It is important that the patient also receive local anesthesia, administered as for routine periodontal surgery, to ensure comfort for the patient and reduced bleeding during the procedure. The judicious use of local anesthetics to block regional nerves allows the level of sedation or general anesthesia to be lighter. Hence the entire operation is performed with a wider margin of safety.

Positioning and Periodontal Dressing

Surgery in the operating room is typically performed on the operating table with the patient lying down and the table either positioned flat or with the head inclined up to 30 degrees. Some operating rooms are equipped with dental chairs that can be used either flat or up to 30 degrees.

When general anesthesia is used, it is advisable to delay placing the periodontal dressing until the patient has recovered sufficiently to have a demonstrable cough reflex. Periodontal dressings placed before the end of general anesthesia can be displaced during the recovery period and pose serious risks of blocking the airway.

Postoperative Instructions

After a full recovery from general anesthesia, most patients can be discharged home with a responsible adult. The effects of general anesthesia and sedative agents make the patient drowsy for hours, and adult supervision at home is recommended for up to 24 hours after surgery. The typical postoperative instructions should be given to the responsible adult and the patient scheduled for a postoperative visit in 1 week.

Surgical Instruments

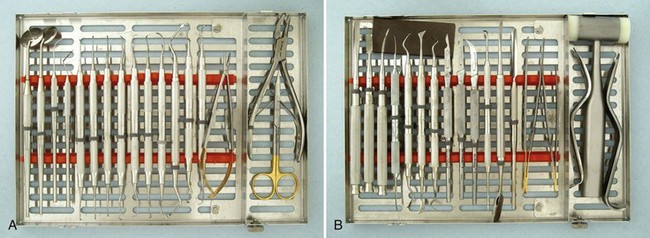

Periodontal surgery is accomplished with numerous instruments; Figure 54-5 shows a typical surgical cassette. Periodontal surgical instruments are classified as follows:

Figure 54-5 Typical series of periodontal surgical instruments, divided into two cassettes. A, From left, Mirrors, explorer, probe, series of curettes, needleholder, rongeurs, and scissors. B, From left, Series of chisels, Kirkland knife, Orban knife, scalpel handles with surgical blades (#15C, 15, 12D), periosteal elevators, spatula, tissue forceps, cheek retractors, mallet, and sharpening stone.

(A Courtesy Hu-Friedy, Chicago; B Courtesy G. Hartzell & Son, Concord, CA.)

Excisional and Incisional Instruments

Periodontal Knives (Gingivectomy Knives)

The Kirkland knife is representative of knives typically used for gingivectomy. These knives can be obtained as either double-ended or single-ended instruments. The entire periphery of these kidney-shaped knives is the cutting edge (Figure 54-6, A).

Interdental Knives

The Orban knife #1-2 (Figure 54-6, B) and the Merrifield knife #1, 2, 3, and 4 are examples of knives used for interdental areas. These spear-shaped knives have cutting edges on both sides of the blade and are designed with either double-ended or single-ended blades.

Surgical Blades

Scalpel blades of different shapes and sizes are used in periodontal surgery. The most common blades are #12D, 15, and 15C (Figure 54-7). The #12D blade is a beak-shaped blade with cutting edges on both sides, allowing the operator to engage narrow, restricted areas with both pushing and pulling cutting motions. The #15 blade is used for thinning flaps and general purposes. The #15C blade, a narrower version of the #15 blade, is useful for making the initial, scalloping-type incision. The slim design of this blade allows for incising into the narrow interdental portion of the flap. All these blades are discarded after one use.

Electrosurgery (Radiosurgery) Techniques and Instrumentation

The term electrosurgery or radiosurgery39 is currently used to identify surgical techniques performed on soft tissue using controlled, high-frequency electrical (radio) currents in the range of 1.5 to 7.5 million cycles per second, or megahertz. There are three classes of active electrodes: single-wire electrodes for incising or excising; loop electrodes for planing tissue; and heavy, bulkier electrodes for coagulation procedures.16,28

The four basic types of electrosurgical techniques are electrosection, electrocoagulation, electrofulguration, and electrodesiccation.

Electrosection, also referred to as electrotomy or acusection, is used for incisions, excisions, and tissue planing. Incisions and excisions are performed with single-wire active electrodes that can be bent or adapted to accomplish any type of cutting procedure.

Electrocoagulation provides a wide range of coagulation or hemorrhage control by using the electrocoagulation current. Electrocoagulation can prevent bleeding or hemorrhage at the initial entry into soft tissue, but it cannot stop bleeding after blood is present. All forms of hemorrhage must be stopped first by some form of direct pressure (e.g., air, compress, or hemostat). After bleeding has momentarily stopped, final sealing of the capillaries or large vessels can be accomplished by a short application of the electrocoagulation current. The active electrodes used for coagulation are much bulkier than the fine tungsten wire used for electrosection. Electrosection and electrocoagulation are the procedures most often used in all areas of dentistry. The two monoterminal techniques, electrofulguration and electrodesiccation, are not in general use in dentistry.

The most important basic rule of electrosurgery is: always keep the tip moving. Prolonged or repeated application of current to tissue induces heat accumulation and undesired tissue destruction, whereas interrupted application at intervals adequate for tissue cooling (5 to 10 seconds) reduces or eliminates heat buildup. Electrosurgery is not intended to destroy tissue; it is a controllable means of sculpturing or modifying oral soft tissue with little discomfort and hemorrhage for the patient.

The indications for electrosurgery in periodontal therapy and a description of wound healing after electrosurgery are presented in Chapter 56. Electrosurgery is contraindicated for patients who have incompatible or poorly shielded cardiac pacemakers.

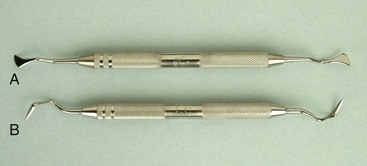

Surgical Curettes and Sickles

Larger and heavier curettes and sickles are often needed during surgery for the removal of granulation tissue, fibrous interdental tissues, and tenacious subgingival deposits. The Prichard curette (Figure 54-8) and the Kirkland surgical instruments are heavy curettes, whereas the Ball scaler #B2-B3 is a popular heavy sickle. The wider, heavier blades of these instruments make them suitable for surgical procedures.

Periosteal Elevators

The periosteal elevators are needed to reflect and move the flap after the incision has been made for flap surgery. The Woodson and Prichard elevators are well-designed periosteal instruments (Figure 54-9).

Surgical Chisels

The back-action chisel is used with a pull motion Figure 54-10, whereas the straight chisel (e.g., Wiedelstadt, Ochsenbein #1-2) is used with a push motion (Figure 54-11). The Ochsenbein chisel is a useful chisel with a semicircular indentation on both sides of the shank that allows the instrument to engage around the tooth and into the interdental area. The Rhodes chisel is another popular back-action chisel.

Tissue Forceps

The tissue forceps is used to hold the flap during suturing. It is also used to position and displace the flap after the flap has been reflected. The DeBakey forceps is an extremely efficient instrument (Figure 54-12).

Scissors and Nippers

Scissors and nippers are used in periodontal surgery to remove tabs of tissue during gingivectomy, trim the margins of flaps, enlarge incisions in periodontal abscesses, and remove muscle attachments in mucogingival surgery. Many types are available, and individual preference determines the choice. The Goldman-Fox #16 scissors has a curved, beveled blade with serrations (Figure 54-13).

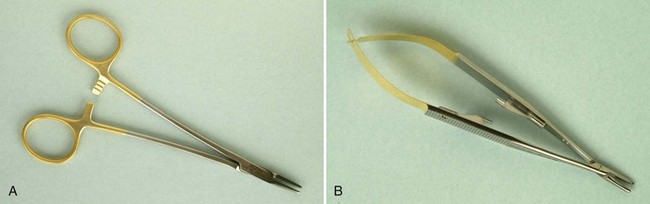

Needleholders

Needleholders are used to suture the flap at the desired position after the surgical procedure has been completed. In addition to the regular types of needleholder (Figure 54-14, A), the Castroviejo needleholder is used for delicate, precise techniques that require quick and easy release and grasp of the suture (Figure 54-14, B).

1 ADA guide to dental therapeutics. Chicago: American Dental Association, 1998.

2 Addy M, Douglas WH. A chlorhexidine-containing methacrylic gel as a periodontal dressing. J Periodontol. 1975;46:465.

3 Allen GD. Dental anesthesia and analgesia (local and general), ed 3. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1984.

4 Ariaudo AA. The efficacy of antibiotics in periodontal surgery. J Periodontol. 1969;40:150.

5 Baer PN, Goldman HM, Scigliano J. Studies on a bacitracin periodontal dressing. Oral Surg. 1958;11:712.

6 Baer PN, Summer CFIII, Miller G. Periodontal dressings. Dent Clin North Am. 1969;13:181.

7 Blitzer B. A consideration of the possible causes of dental hypersensitivity: treatment by a strontium ion dentifrice. Periodontics. 1967;5:318.

8 Burch J, Conroy CW, Ferris RT. Tooth mobility following gingivectomy: a study of gingival support of the teeth. Periodontics. 1960;6:90.

9 Collins JF, Gingold J, Stanley H, et al. Reducing dentinal hypersensitivity with strontium chloride and potassium nitrate. Gen Dent. 1984;32:40.

10 Curro FA. Tooth hypersensitivity. Dent Clin North Am. 1990;34:403.

11 Curtis JWJr, McLain JB, Hutchinson RA. The incidence and severity of complications and pain following periodontal surgery. J Periodontol. 1985;56:597.

12 Dal Pra DJ, Strahan JD. A clinical evaluation of the benefits of a course of oral penicillin following periodontal surgery. Aust Dent J. 1972;17:219.

13 Fraleigh CM. An evaluation of topical Terramycin in postgingivectomy pack. J Periodontol. 1956;27:201.

14 Gangarosa LP Sr. Current strategies for dentist-applied treatment in the management of hypersensitive dentine. Arch Oral Biol. 1994;39(suppl):101S.

15 Gerschman JA, Ruben J, Gebart-Eaglemont J. Low-level laser therapy for dentinal tooth hypersensitivity. Aust Dent J. 1994;39:353.

16 Gnanasekhar JD, al-Duwairi YS. Electrosurgery in dentistry. Quintessence Int. 1998;29:649.

17 Hirschfeld AS, Wassermen BH. Retention of periodontal packs. J Periodontol. 1958;29:199.

18 Holmes CH. Periodontal pack on single tooth retained by acrylic splint. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;64:831.

19 Javelet J, Torabinejad M, Danforth A. Isobutyl cyanoacrylate: a clinical and histological comparison with sutures in closing mucosal incisions in monkeys. Oral Surg. 1985;59:91.

20 Jones JK, Triplett RG. The relationship of cigarette smoking to impaired intraoral wound healing: a review of evidence and implications for patient care. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:237.

21 Kidd EA, Wade AB. Penicillin control of swelling and pain after periodontal osseous surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1974;1:52.

22 Lan WH, Liu HC. Treatment of dentin hypersensitivity by Nd:YAG laser. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1996;14:89.

23 Lan WH, Liu HC, Lin CP. The combined occluding effect of sodium fluoride varnish and Nd:YAG laser irradiation on human dentinal tubules. J Endodont. 1999;25:424.

24 Levin MP, Cutright DE, Bhaskar SN. Cyanoacrylate as a periodontal dressing. J Oral Med. 1975;30:40.

25 Majewski I, Sponholz H. Ergebnisse nach parodonal therapeutischen Massnahmen unter besonderer Berucksichtigung der Zahnbeweglichkeitssung mit dem Makroperiodontometer nach Muhlemann. Zahnaerztl Rundsch. 1966;75:57.

26 Malamed SF. Sedation: a guide to patient management, ed 3. St Louis: Mosby; 1995.

27 Miller JT, Shannon KL, Kilyore WG, et al. Use of water-free stannous fluoride–containing gel in the control of dental hypersensitivity. J Periodontol. 1969;40:490.

28 Moore DA. Electrosurgery in dentistry: past and present. Gen Dent. 1995;43:460.

29 Murphy NC, DeMarco TJ. Controlling pain in periodontal patients. Dent Surv. 1979;55:46.

30 Newman MG, Sanz M, Nachnani S, et al. Effect of 0.12% chlorhexidine on bacterial recolonization after periodontal surgery. J Periodontol. 1989;60:577.

31 Pack PO, Haber J. The incidence of clinical infection after periodontal surgery: a retrospective study. J Periodontol. 1983;54:441.

32 Pendrill K, Reddy J. The use of prophylactic penicillin in periodontal surgery. J Periodontol. 1980;51:44.

33 Preber H, Bergstrom J. Effect of cigarette smoking on periodontal healing following surgical therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17:324.

34 Romanow I. Allergic reactions to periodontal pack. J Periodontol. 1957;28:151.

35 Romanow I. Relationship of moniliasis to the presence of antibiotics in periodontal packs. Periodontics. 1964;2:298.

36 Ross MR. Hypersensitive teeth: effect of strontium chloride in a compatible dentifrice. J Periodontol. 1961;32:49.

37 Sachs HA, Fanroush A, Checchi L, et al. Current status of periodontal dressings. J Periodontol. 1984;55:689.

38 Sanz M, Newman MG, Anderson L, et al. Clinical enhancement of post-periodontal surgical therapy by 0.12 per cent chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinse. J Periodontol. 1989;60:570.

39 Sherman JA. Oral radiosurgery: an illustrated clinical guide, ed 2. London: Martin Dunitz; 1997.

40 Smith DC. A materialistic look at periodontal packs. Dent Pract Dent Rec. 1970;20:273.

41 Strahan JD, Glenwright HD. Pain experience in periodontal surgery. J Periodontal Res. 1967;1:163.

42 Tarbet WJ, Silverman G, Stolman JW, et al. A clinical evaluation of a new treatment for dentinal hypersensitivity. J Periodontol. 1980;51:535.

43 Tonetti MS, Pini Prato G, Cortellini P. Effect of cigarette smoking on periodontal healing following GTR in infrabony pockets: a preliminary retrospective study. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:229.

44 Trowbridge HO, Silver DR. A review of current approaches to in-office management of tooth hypersensitivity. Dent Clin North Am. 1990;34:583.

45 Vaughan ME, Garnick JJ. The effect of 0.125 per cent chlorhexidine rinse on inflammation after periodontal surgery. J Periodontol. 1989;60:704.

46 Ward AW. Inharmonious cusp relation as a factor in periodontoclasia. J Am Dent Assoc. 1923;10:471.

47 Watts TA, Combe EC. Adhesion of periodontal dressings to enamel in vitro. J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:62.

48 Westfelt E, Nyman S, Socransky SS. Significance of frequency of professional cleaning for healing following periodontal surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:148.