CHAPTER 11 Endodontic Records and Legal Responsibilities

Endodontic Record Excellence

Importance

Endodontic therapy records serve as an important map to document and guide the clinician’s journey down the correct diagnostic and treatment path. Documentation is essential to attaining endodontic excellence.

The dental record must contain sufficient information to identify the patient, support the diagnosis, justify the treatment, and document the course and result of treatment. Records also are fundamental means of communication among health care professionals, designed to protect the patient’s welfare.

Function

Dental records should document the following information:

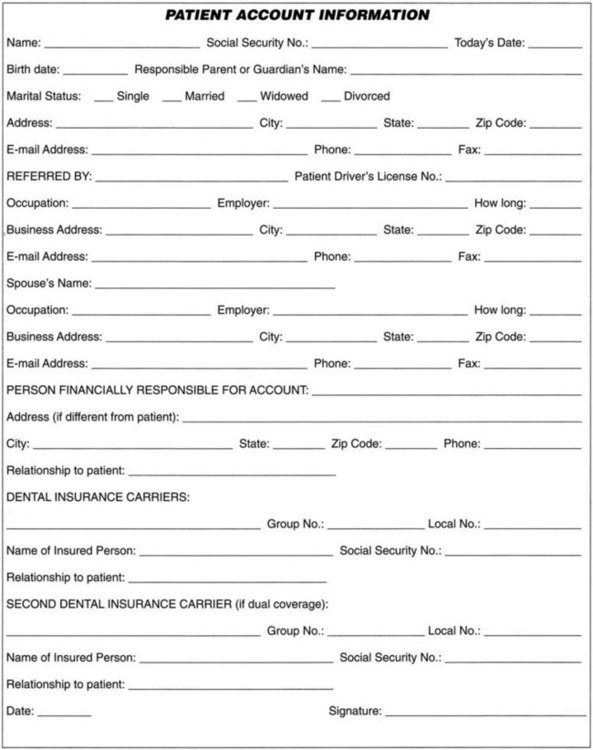

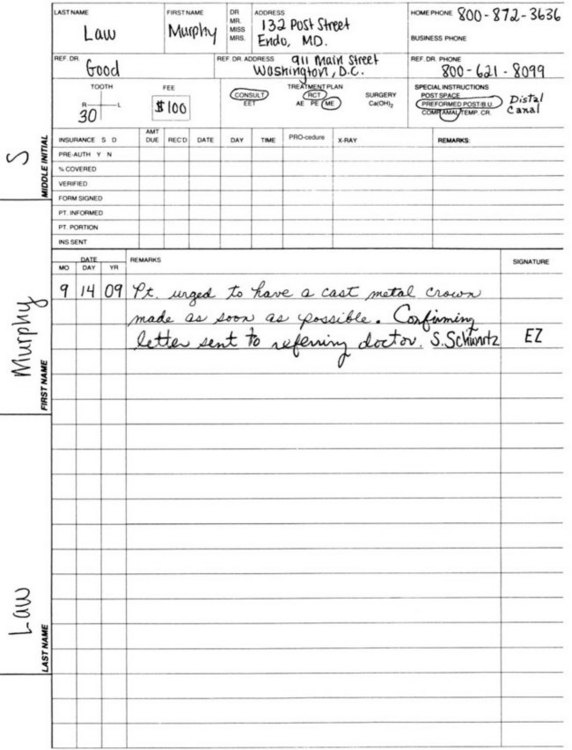

Patient Information Form

A patient information form provides essential data for patient identification and office communication. The patient’s name; home, business, e-mail addresses; and telephone and fax numbers are needed to contact the patient for scheduling purposes and inquire about postoperative sequelae.144 Location information about the patient’s spouse, relative, or a close friend who can be notified in an emergency is also suggested. In the event the patient is a minor, the responsible parent or guardian should provide the information. Questions about dental insurance and financial responsibility are included on the form to avoid any later misunderstandings and help fulfill federal requirements of the Truth in Lending Law, applicable if four or more installment payments are arranged (whether or not there are interest or late-payment charges).79 Patient information should be updated periodically (Fig. 11-1).

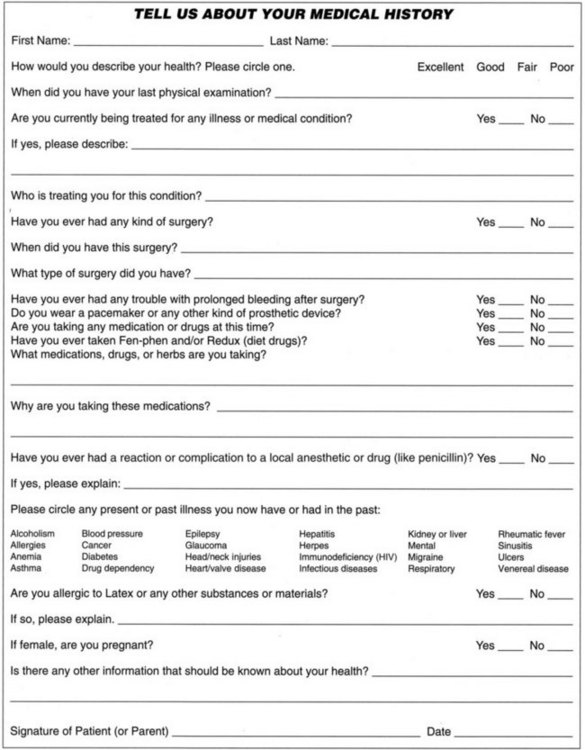

Medical Health History

Past and present health status should be thoroughly reviewed by the clinician before proceeding with treatment so that dental treatment can be safely initiated. Health questionnaires open avenues for discussion about problems of major organ systems and important biochemical mechanisms, such as blood coagulation, allergy, immunocompromised status, need for antibiotic prophylaxis, and disease susceptibility. The clinician may request that the patient be examined by a physician or undergo laboratory testing under medical supervision to determine whether a suspected medical problem may require attention before endodontic therapy proceeds or if drug sensitivity or allergy mandates treatment modifications.29,135,152 Current medications, medical therapy, and the name and location of the treating physician are essential.

Medical histories must be updated periodically (or at least annually or sooner as the need arises). The patient should be asked to review the previous and current medical history (Fig. 11-2). If no changes are necessary, the patient should date and sign the history form. If any changes occurred, the patient should identify each updated medical change, the date, and sign the form where indicated for medical update information. Periodically the patient should provide an entirely new updated form rather than changing data on the old form. Earlier medical histories should be retained in the chart for future reference. If physician communication for treatment occurs, the clinician should record such contacts. In addition, the clinician should verify physician approvals for treatment by fax, with verification of receipt or letter or preferably both, and retain copies in the chart.

Updating the medical history requires the practitioner to be apprised of changes in the patient’s medical condition and any new medications the patient is taking, including over-the-counter or herbal medications and/or supplements. A patient untrained in medical science may not appreciate the fact that new medications may suggest new diseases or changes in existing disease status. For instance, certain regurgitating valvular heart diseases may require antibiotic prophylaxis.269 New medications may also cause a synergistic effect with other medications the patient is using or another treating clinician is prescribing.

Clinicians who pass the buck by claiming, “Oh it was my secretary or my new assistant—I could do nothing about it,” are nonetheless legally liable for their staff’s actions or inactions.270 A clinician exclusively relying on staff members to obtain medical histories in a waiting room full of patients is making a mistake, because the accuracy of the histories must first be checked and then followed up by the clinician. Training and monitoring staff are duties clinicians cannot afford to ignore. President Harry Truman’s sage advice, “The buck stops here,” applies to treating clinicians who overdelegate to nonclinician staff members who lack the requisite dental education for adequate medical history follow-up.

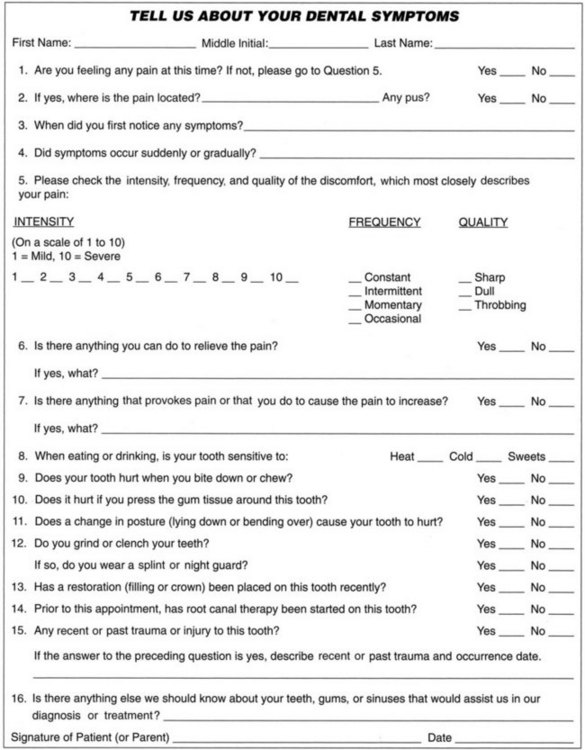

Dental History

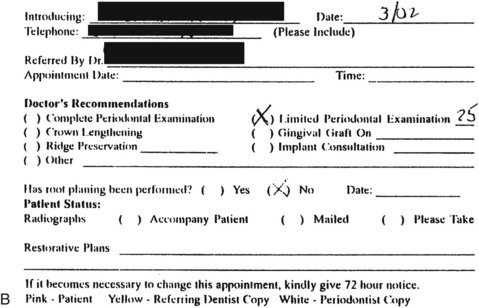

The dental history should include past dental difficulties, name and address of current or most recent treating clinician, chief complaint (including duration, frequency, type and intensity of any pain), relevant prior dental treatment, and attitude regarding teeth retention. Positive responses suggest further patient consultation and consideration for obtaining records (by written release) for elucidation from the patient’s previous and/or present treating clinician.188 After receiving positive responses, the clinician may also wish to obtain prior and concurrent treaters’ radiographs for current comparison and notes of any progressive changes (Fig. 11-3).

Diagnostic and Progress Records

Diagnostic and progress records often combine fill-in and check-off types of forms. Fill-in or essay-type forms allow greater latitude of response to a question, resulting in a more detailed description. However, one drawback to these forms is that they are open to oversights unless a clinician is very conscientious in following up with further clinical information.

Using only an essay-type health history is insufficient. Often a patient may not appreciate the significance of important symptoms. A check-off format is efficient and more practical. Forms with questions that reveal pertinent data alert the clinician to medical or dental conditions that warrant further consideration or consultation.29 Moreover, such records can document any missing medical information the patient failed to provide orally. At the end of the check-off portion of the medical history, an essay question allows the patient to provide any omitted pertinent medical information or elaborate on check-marked items.221,231

Electronic Records

Electronic records represent current methodology for recording patient information (see Chapter 28 for details).246 Several safeguards are essential for their use. First, patient confidentiality and security must be protected. Consider using AES encryption with at least 2048 bit key. Be certain that only the clinician and authorized staff view patient data in conformance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) security standards, effective April 2005.120 Second, data backup of patient records, including digital radiographs and account ledgers, should be stored off-site. The entire hard drive should be periodically backed up for additional protection.70 Multiple copies of the backup data should be stored in more than one geographic location, and fault protection such as RAID Level 1 or 5 should be installed to prevent data loss.

Radiographs

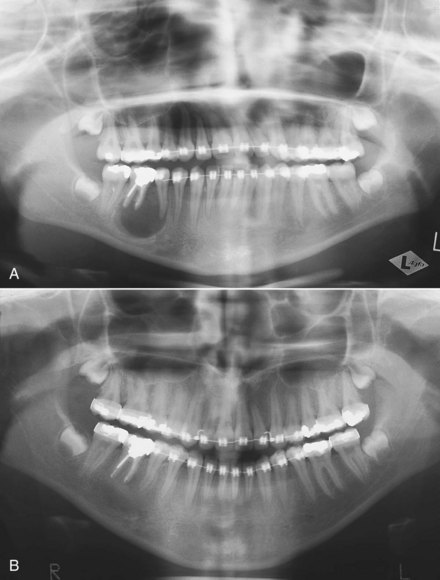

Radiographs are essential for diagnosis and also serve as additional documentation of the patient’s pretreatment condition. A panographic radiograph is not diagnostically accurate for endodontics and therefore should be used only as a screening device (see Chapter 5).114,219,279 Diagnostic quality periapical plain-film or digital radiographs are essential aids for diagnosis, for working films (e.g., measuring the length of root canals, fitting gutta-percha cones), to verify the final fill, and for follow-up comparisons at recall examinations. Therefore the clinician should retake any radiographs that lack diagnostic quality and retain all radiographs.

Digital radiography is recommended because it increases endodontic efficiency. No developing time is needed, so procedural radiographs can be viewed instantly and approved or retaken with little time in between (no downtime is required to wait for a film to exit the film processor). Newer digital x-rays with improved sensor technology use high-resolution CCD (charged coupling device) chips rather than CMOS (complementary metal-oxide semiconductor) technology, and provide close-up zooming with improved image quality as described in Chapter 29.

Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis includes evaluating pertinent history of the current problem, clinical examination, pulpal testing, periodontal probe charting, and recorded radiographic results. If therapy is indicated, the reasons should be discussed with the patient in an organized way. When other factors affect the prognosis (e.g., strategic importance or restorability of the tooth), the clinician should consider further consultation with the referring clinician or specialists, including a prosthodontist, periodontist, or both, before initiating endodontic treatment.

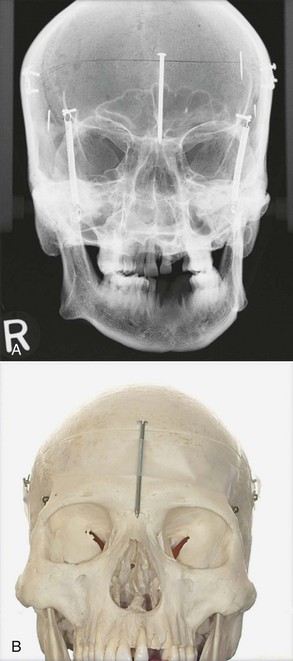

Diagnosis is essential in treatment decisions. Recommending extractions for undiagnosed pain etiology is generally contraindicated. Chronic idiopathic orofacial pain warrants referrals and consultation with other health care professionals, lest wholesale extractions worsen the patient’s dental state and not relieve pain (see Chapter 3).5 For instance, in a long-term follow-up study of patients with chronic facial pain and without recognizable odontologic pathosis, some patients were subsequently diagnosed with maladies ranging from cracked-tooth syndrome to medication-mediated illnesses.5 Accordingly, referral to other specialists is essential, lest a patient be misdiagnosed with idiopathic or atypical facial pain when instead, pain etiology was misdiagnosed. Cone-beam computerized tomography (CBCT) has greatly aided diagnosing pain sources caused by root fractures and incompletely filled, overfilled, or missed extra canals that two-dimensional (2D) periapical imaging may obscure.*

Fig. 11-4, A-B demonstrates the advantage of CBCT three-dimensional (3D) imaging compared to 2D imaging. In A, the nail appears inside the cranium, contrasted with B, which shows the nail taped outside the skull.

Diagnostic Tests

Sound endodontics begins with a proper diagnosis. Otherwise, unnecessary or risky treatment with compromised prognosis follows. Generally, as described in greater detail in Chapter 1, the following endodontic tests should be performed to arrive at a correct and accurate endodontic diagnosis:

Both positive and negative pulpal testing results should be recorded. Juries, peer-review committees, and insurance consultants often disbelieve unrecorded test results. Uncharted test findings may be regarded as never having been done. Consequently, reasonable clinicians should record all testing results, both positive and negative.

Treatment Plan

Treatment records should contain a written plan that includes all aspects of the patient’s oral health. Treatment plans should be coordinated, preferably in writing, with other concurrent or jointly treating clinicians. If an aspect of the patient’s care is not under direct supervision, the clinician is proceeding improperly. Also, the clinician should initiate contact with the other treating clinician. The patient should also be advised of the problem. For instance, endodontic treatment will probably fail if underlying periodontal pathosis is ignored or untreated, so the clinician should assess the patient’s entire dentition, not just a single root canal system. The clinician should also recommend a periodontal consultation to both the patient and referring clinician if periodontal therapy is required. Follow the maxim: If you fail to plan, plan to fail.

Examination

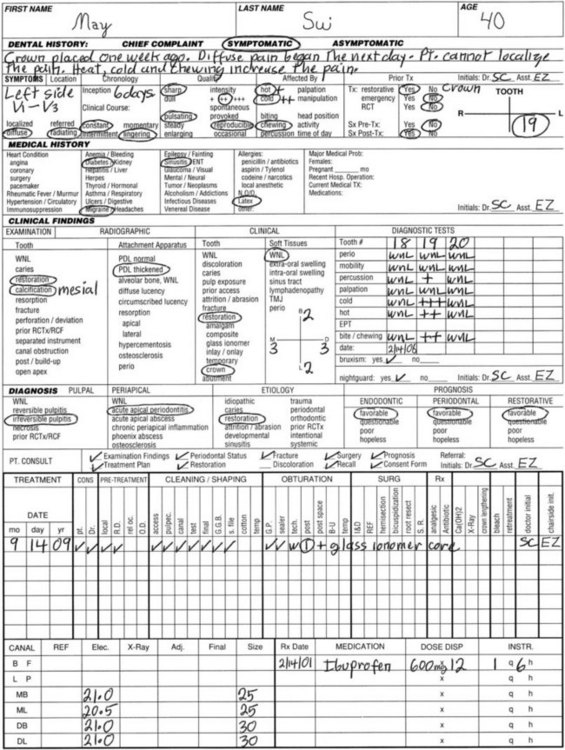

After gathering the dental and medical history, findings obtained from the various phases of the clinical and radiographic examinations are recorded as shown in Fig. 11-5. Lists in each category afford the clinician a systematic format for recording details pertinent to an accurate diagnosis. Appropriate descriptions are circled, followed by the necessary notations in the accompanying spaces. Tabular arrangement allows easier recording and comparison of diagnostic test data acquired from one tooth on different dates or from different teeth on the same visit. A pain intensity index (i.e., 0 to 10) or pain classification (i.e., mild +, moderate ++, severe +++) should be used to differentiate diagnostic test results.

Diagnosis

Careful analysis of accumulated examination data should result in the determination of an accurate pulpal and periapical diagnosis. Clinical conditions and the probable etiologic factors for the presenting problem are circled. Alternative modalities of therapy are considered and analyzed. The recommended treatment plan is circled, followed by a prognostic assessment of the intended therapeutic course.

Patient Consultation

Patients should be advised of each diagnosis and should consent to the treatment plan before therapy is instituted. Consultation should include an explanation of reasonable alternative treatment approaches and rationales and treatment consequences of each alternative therapy, including risks from nontreatment or delayed treatment that may affect the outcome of intended therapy. Such discussion is documented by completing the checklist items.

Treatment

All treatment provided on a given date is documented by placing a check mark (✓) within the designated procedural category. Only the most frequent retreatment procedures are included for tabulation. Descriptions of occasional procedures or explanatory treatment remarks should be entered in writing. A separate dated entry should be made for each patient visit, phone call, e-mail message, and fax communication (e.g., consultations with the patient or other clinicians) or correspondence (e.g., biopsy report, treatment completion letters).

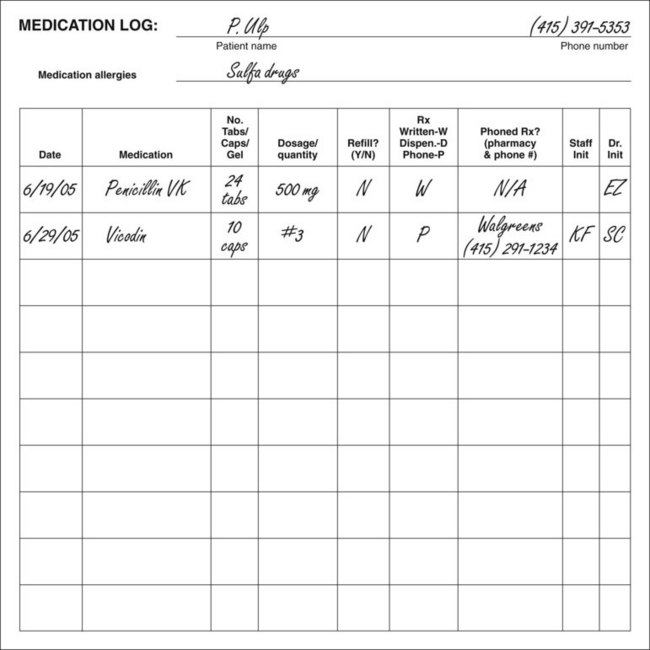

Individual root canal lengths are recorded by (1) circling the corresponding anatomic designation and the method of length determination (e.g., radiograph or electronic measuring device), (2) writing the measurement (in millimeters), and (3) indicating the reference point. For any medication prescribed, refilled, or dispensed, the treatment record should show the date and type of drug (including dose, quantity, and instructions for use) in the treatment table under the heading “Rx.” Fig. 11-6 also gives a sample medication log. Periodic recall intervals, dates, and findings are entered in the spaces provided.

If the scope of the examination or treatment is intentionally limited, such as a screening examination or emergency endodontic therapy, the limited scope of the visit should be recorded. Otherwise, the chart appears as if the examination was superficial and treatment incomplete. If a suspicious apical lesion requires subsequent reevaluation, the clinician should record the future reevaluation date and differential diagnosis (e.g., “Small apical lesion on #28. Reevaluate for changes in 2 months. Also, check for any root fractures.”). If this is not done, it appears (on the chart) as if the clinician ignored a potentially pathologic condition, such as suspected root fracture. A soft-tissue examination (including cancer check) is a standard part of any complete dental examination. E-mail prescriptions and correspondence should be documented with hard copies in the chart unless virtually all treatment records are stored in electronic format.154,246

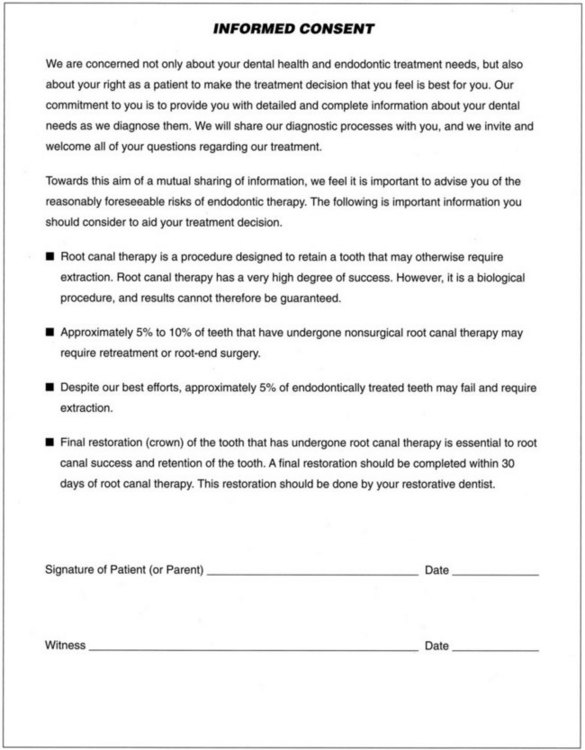

Informed Consent Form

After endodontic diagnosis, the benefits, risks, treatment plan, and alternatives to endodontic treatment—including any patient refusal of recommended treatment and consequences of refused treatment—should be presented to the patient or the patient’s guardian. This will document acceptance or rejection of treatment recommendations. The patient or guardian, along with a witness (who can be a staff member), should sign and date the consent form. Any informed-consent video should similarly be noted. Subsequent changes in the proposed treatment plan should also be discussed and initialed by the patient to indicate continued acceptance and acknowledge the patient’s understanding of any newly disclosed risks, alternatives, or referrals.

Despite a patient’s confirmed signature on an informed consent form, a jury is free to believe that the patient never read the informed consent form’s content before signing. For instance, the patient may claim it was impossible to have read the consent form, because he or she did not have reading glasses when signing, and no clinician ever explained the form contents. Another frequent factual scenario is when the patient claims the staff stated it was a standard consent form that was a mere procedural formality requiring patient signature, rather than a detailed informed consent form. Consequently, numerous legal cases have been lost at trial on the issue of inadequate informed consent despite a signed patient consent form.

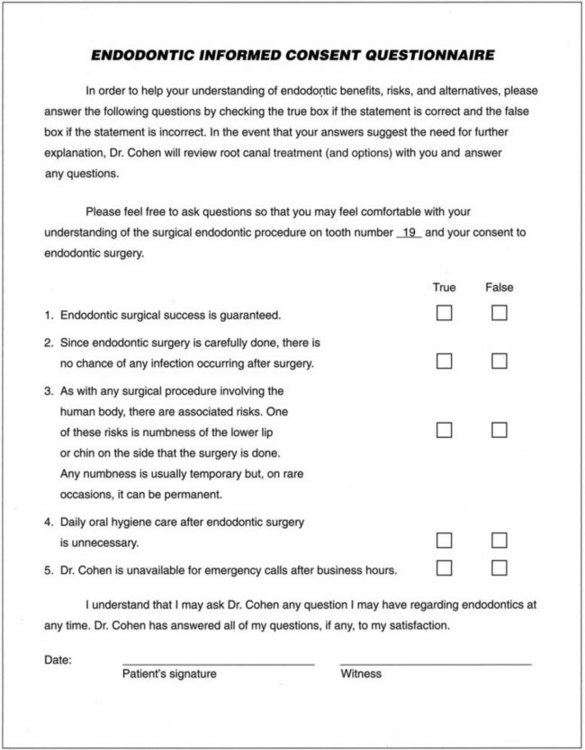

To obviate a patient’s claim that no explanation ever occurred, a patient questionnaire can additionally be used. Patients can be instructed that unless they score 100%, proposed procedures will not be done (because patient understanding is imperative and essential for cooperation, including postoperative care). To be effective, the patient questionnaire should be relatively short and simple (Fig. 11-7). Also, the patient should be given an opportunity to correct any incorrect answers after the clinician reviews with the patient the reasons why the patient answered incorrectly. Note that the majority of answers are false. This precludes a patient from guessing the correct answer by assuming that all test questions are necessarily true.

Treatment Record: Endodontic Chart

Chart

A suggested chart is presented in Fig. 11-8 to facilitate recording of information pertinent to the diagnosis, recommendations, and treatment of the endodontic patient. Systematic acquisition and arrangement of data from the patient questionnaire, along with clinical and radiographic examinations and careful recording of treatment performed, expedites accurate diagnosis and maximizes clinician efficiency. Suggested chart format and use are described in the sections that follow.

General Patient Data

Patient name, address, phone numbers, referring clinician, and chief complaint are printed or typed in the corresponding space at the patient’s initial office visit. The patient’s appointment and financial record are divided into two parts as follows:

Either the clinician or the assistant may complete portions of the diagnosis and treatment sections, but the clinician should review and approve all entries.

Dental History

Chief complaint should include whether the patient is symptomatic at the time of examination and/or recent past. Narrative facts regarding the presenting problem are then recorded. Additional details of the chief complaint obtained during successive questioning are recorded by circling the applicable word within each symptom parameter. The pain intensity index (i.e., 0 to 10) or pain classification (i.e., mild +, moderate ++, severe +++) should be registered alongside the appropriate description. For accurate assessment of the effects of prior dental treatment pertaining to the examination site, a summarized account of such procedures should be documented. In addition, all pretreatment signs and symptoms should be described. It is essential that the patient comprehend all communications with the clinician and staff. If there is any language comprehension difficulty, the clinician should ask the patient whether he or she understands completely the language the clinician is speaking. To verify patient comprehension, the clinician should ask the patient to repeat important information that has been conveyed. A clinician- or patient-provided interpreter may be necessary if language problems exist.57

Medical History

More medical history information is obtained from a patient-administered questionnaire than from the clinician obtaining an oral history solely from the patient.29,231 Maximum information is obtained if the clinician reviews with the patient the written health history form the patient has completed.

Information (e.g., personal physician’s name, address, and phone number; patient’s age; date of last medical examination) is recorded for reference. The clinician can obtain a detailed medical history by completing a survey of common diseases and disorders along with a comprehensive review of corresponding organ systems and assorted pathologic conditions. Specific entities that have affected the patient are circled. Essential remarks regarding these entries (e.g., details of consultations with the patient’s physician) should be documented on an attached blank sheet with dated treatment notes attached to the back of the chart (see Fig. 11-2). A review of the patient’s medical status (including recent or current conditions, treatments, and medications) completes the medical history. Updated medical histories which the patient signs or initials should be done at least annually and at reevaluation visits.

Drug History

A current drug history, both written and oral, is necessary to alert the clinician to any potential for interaction between any newly prescribed drugs and any other medication, supplements or over-the-counter medication the patient is already taking.

In patients aged 57 through 85, 40% potentially are at risk of a major drug reaction—half involving various prescription medications and the other half anticoagulant drug reactions. About half of prescription users also concurrently take over-the-counter medications plus dietary supplements.153,196

Risks of drug interactions or side-effects incidence may not be discovered and/or appreciated in premarket research-controlled drug trials for newly marketed drugs, despite FDA approval. For example, rofecoxib (Vioxx) was withdrawn from the market in September 2004 after increased incidences of myocardial infarcts and strokes manifested in a postmarket research study of 2600 patients. Merck’s voluntary recall followed an FDA researcher’s claim that the FDA tried to ostracize and intimidate him after he raised safety concerns over Vioxx.21 Currently, pharmaceutical manufacturers budget more for marketing than research and development.96 Some drug manufacturers have suppressed publication of adverse research.38,170,272 U.S. Senators Chuck Grassley (R, IA) and Herb Kohl (D, WI) are probing the financial relationships among the drug industries, health care prescribers, and researchers (Senate Bill 2029 [http://thomas.loc.gov]). If their Physician Payments Sunshine Act passes, it would require companies to disclose payments to medical/dental professionals who tout their drugs in seminars or publications.

For newly marketed drugs, the small number of premarket patients studied may lack sufficient statistical power to expose serious side effects that occur infrequently but are nonetheless life threatening.272 For instance, mibefradil (Posicor) was withdrawn from the market after 1 year because it increased plasma concentrations of 25 other coadministered drugs, including erythromycin.196,197 In another example, the popular prescription nighttime heartburn drug, Propulsid (cisapride), was linked to 70 deaths and more than 270 significant negative reactions.263 Other examples include the risk of esophageal cancer with bisphosphonate272 and bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis.69,232 In 2008, the FDA added a black box warning label for Levaquin-associated risks of tendonitis (www.levaquin.com/levaquin/medication).

FDA Drug Approval

Until 1962, drug companies were allowed to promote their products for any use so long as they were shown to be “safe” for one use. Manufacturers were marketing drugs with serious side effects for minor conditions and to vulnerable populations, resulting in many injuries and deaths. Ineffective drugs were the rule rather than the exception. When a retrospective review of all drugs was conducted after 1962, the National Academy of Sciences found that fully 80% of the uses for which drugs were being promoted could not be shown to be effective. Since 1962, the FDA has required prescription drug manufacturers to demonstrate safety and efficacy with animal and randomly controlled research trials conducted with FDA-approved protocols. FDA “approval” to market new drugs for specific uses is termed premarket approval (PMA).

In a New Drug Application (NDA) to the FDA, findings from many clinical studies are done to assess a new drug’s efficacy and safety and to gain the FDA’s PMA to market the drug. An NDA judges whether the proposed new drug (1) causes more good than harm (benefit outweighs the risk), (2) is comparatively more effective than already existing marketed drugs, or (3) has unreasonably frequent and/or severe side effects (risk outweighs the benefit).23,257

In 2008, $58 billion in privately funded drug research was approximately twice the basic federal medical research budget and encompassed an estimated 50,000 clinical trials among 2.3 million patients. Medicare drug spending is forecast to grow from 2 billion in 2000 to 153 billion in 2016, a 7550% increase.199 In 2007, one in seven U.S. residents younger than age 65 skipped prescribed medications because of rising prescription cost.81,123

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association of America has created an online database that summarizes clinical study results involving hundreds of prescription medicines. Notwithstanding, the sheer volume of clinical testing has overwhelmed the FDA’s ability to independently assess commercial trials and make all test results public. Deceptive marketing, unreported side effects, and hidden payments to medical/dental researchers highlight the gap between the number of clinical trials conducted and the number published.*

Comprehensive clinical data filed with the FDA for gaining market approval of a new drug (PMA) forms the basis for safety information that accompanies every prescription label.86,88

For the first time, under a new federal law89 effective in 2009, researchers in PMA trials will have to post their basic research results publicly on a federal online registry maintained by the National Library of Medicine. However, new registry regulation will only cover new tests, not tests with poor results done prior to the effective date of the new law. Moreover, findings are not independently FDA verified. Instead, the FDA relies on the manufacturer’s submitted trial data research.

Until September 2007, researchers only had to report the start of a clinical trial and was under no federal legal obligation to report the outcome in the FDA’s registry or in a peer-reviewed journal. Consequently, clinical data on health risks could be downplayed or benefits extolled selectively in any one of 5200 peer-reviewed biomedical journals.254,273

By January 31, 2009, as a voluntary patient guide, the federal registry (www.clinicaltrials.gov) logged 67,000 studies. The results of all drug trials that were ongoing on or after September 27, 2007, must be reported at ClinicalTrials.gov if the products under study have FDA approval. The results for drugs not yet receiving FDA approval do not have to be posted. A deficiency of the current law is that the results of older trials of drugs that were FDA approved before September 27, 2007, and that were no longer the subject of ongoing trials on or after September 27, 2007, do not need to be posted. Such drugs constitute the vast majority of current prescription drugs. The FDA considers much of the data on clinical trials it receives from sponsors—and its own analyses of these data—to be “confidential commercial information.” FDA drug-trial information released to the public is frequently heavily redacted. Redacted disclosure occurs in response to one or multiple requests made under the Freedom of Information Act, but usually only after a prolonged delay. The FDA Amendments Act of 2003 Section 916 institutionalizes this limitation by mandating that the FDA publish on its website key information related to approval of an application for a drug that contains a previously approved active ingredient only after it has received three Freedom of Information Act requests.

In a 2008 University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) study of 164 clinical trials testing 33 different drugs submitted for FDA approval, approximately one in four had yet to be published.216 Virtually all of the unpublished findings were negative. The UCSF study also reported that in 900 FDA filings involving 90 new drugs, more than half the clinical trials were still unpublished 5 years after the drug had FDA approval. UCSF researchers who reviewed the FDA’s regulatory paperwork for dozens of recently FDA-approved (PMA) drugs found that in some clinical trials previously reported to the FDA, when subsequently submitted for publication, conclusions were changed, statistics revised, and outcomes altered to make treatments appear more effective. Among 43 outcomes reported in the FDA filings that did not favor a drug, 20 were never published. In four out of five instances in which the statistical significance of findings were changed from the FDA filing, the published version was more favorable. Positive effects of a new drug were more likely to be submitted for publication than those reporting negative findings. Basic principles of evidence-based practice requires the analysis of all data. Publishing only some results but not others undermines the ability to adequately assess a product’s safety and efficacy, which is FDA’s standard for FDA approval of drugs or devices.

Journals want to sell journals. Companies wish to increase profits. Researchers promote career advancements and seek research funding. Consequently, conflict potentials are pervasive. To offset these temptations, failure to timely report basic data about clinical test results in the federal public registry can subject researchers to fines of $10,000 a day and/or loss of their federal research funding (Public Health Service Act Section 302[J]).86,273

In 2009, the Government Accounting Office (GAO) concluded in GAO’s 2009 High-Risk Series, FDA Oversight of Medical Products259:

New Laws, the complexity of items submitted to FDA for approval, and the globalization of the medical products industry are challenging FDA’s ability to guarantee the safety and effectiveness of drugs, biologic, and medical devices. As a result, the American consumer may not be adequately protected from unsafe and ineffective medical products. FDA needs to improve the data it uses to manage the foreign drug inspection program, do more inspections of foreign establishments that manufacture drugs or medical devices, more systemically review the claims made in drug advertising and promotional material, and ensure that drug sponsors accurately report clinical trial results.

Globalization of clinical research is a relatively recent phenomenon. The number of countries serving as trial sites outside the United States more than doubled in 10 years. Conversely, the proportion of trials conducted in the United States and Western Europe decreased.100 Clinical testing in developing countries help overcome stringent FDA regulatory barriers for FDA drug approval.16

Wide disparities in education, economic and social standing, and health care systems may jeopardize the rights of research participants in foreign countries. Foreign participants may lack understanding of the investigational nature of therapeutic products and/or the use of placebo research participant groups. In some places, financial compensation for research participation may exceed participants’ annual wages. Standards of health care in developing countries may also allow ethically problematic study designs or clinical research trials that would not be allowed in wealthier countries. In one study, only 56% of the 670 researchers surveyed in developing countries reported that their research had been reviewed by a local institutional review board or health ministry.128 In another study, 90% of published clinical trials conducted in China in 2004 did not report ethical review of the protocol, and only 18% adequately discussed informed consent.280

Developing countries will also not realize the benefits of clinical research trials if the drugs being evaluated do not become readily available for host-country research participants after FDA approval is obtained.16 The Declaration of Helsinki includes an expectation that every patient enrolled in a clinical trial should, at the end of the trial, be assured access to the best proven therapy identified in the research study.

Geographically distinct populations can have different genetic profiles; such differences have been shown to be related to the safety and effectiveness of drugs and medical devices. For example, a study of 42 genetic variants associated with pharmacologic response in drug studies showed that more than two thirds had significant differences in frequency between persons of African ancestry and those of European ancestry.105 Genetic diversity is often not considered in study design and interpretation and in the reporting of trial results.

From fiscal 2002 through 2007, the FDA issued 15 warning letters to foreign companies with serious deficiencies, but the agency only reinspected four of the companies, and then only 2 to 5 years later. Decades ago, most pills consumed in the United States were made here. But like other manufacturing operations, drug plants have been moving to Asia because labor, construction, regulatory, and environmental costs are lower there. The world’s growing dependency on Chinese drug manufacturers become apparent in the heparin scare. In 2007, Baxter Intentional and APP Pharmaceuticals split the domestic market for heparin, an anticlotting drug needed for surgery and dialysis. When federal drug regulators discovered that Baxter’s product had been contaminated by Chinese suppliers, the FDA banned Baxter’s product and turned almost exclusively to the one from APP. However, APP also obtained its heparin product from China. Of the 1154 pharmaceutical plants with generic drug application to the FDA in 2007, only 13% were in the United States; 43% were in China, and 39% were in India.259 Drug labels often claim that the pills are manufactured in the United States, but the listed U.S. plants are often the sites where foreign-made drug powders are pounded into pills and packaged.

Under the Prescription Drug User Fee Act, known as PDUFA, pharmaceutical companies pay the FDA to facilitate their PMA applications. Congress provided PDUFA with added power to impose restrictions on the sale of drugs and enforce regulations requiring that postmarketing surveillance studies be timely completed rather than delayed or evaded. Notwithstanding PUDFA, in 2008 the FDA was still missing target dates to act on NDAs because the FDA lacks sufficiently adequate staffing to handle PMA applications.210

Dietary Supplements

The Dietary Supplements Health and Education (DSHE) Act allows dietary supplements to be sold directly to consumers without any oversight or FDA regulation. In response to intense lobbying by the multibillion-dollar dietary supplement industry, Congress in 1994 exempted these products from FDA regulation.153,167,277 Products may contain amounts claimed, but they need not, and nothing can prevent their sale if they do not. For example, an analysis of ginseng167 products showed no ginseng at all in some products. The DSHE Act places the burden of proof for dietary supplements’ safety on the FDA and not the manufacturer. As a result, consumers of herbal supplements must depend on self-regulation within the industry for assurance of product quality, consistency, potency, and purity.134,277 An understaffed and overworked FDA can hardly be expected to be a vigorous enforcer.

An herbal product label can state the way the product is intended to affect “the structure or function” of the body but cannot claim its use for a specific disease. Manufacturers thus use creative language that complies technically with the statute but generally is confusing and/or deceptive.167

A current medication history form should include over-the-counter, herbal, and illicit drugs, many of which have the potential for synergistic or antagonistic interaction with clinician-prescribed drugs.277 Ma-huang, or ephedra, a major component of many weight loss supplements, has been associated with more than 800 adverse health effects, including the death of major league baseball player Steve Bechler. It is an amphetamine-like compound with the potential for overstimulating the central nervous system and heart. Ephedra/ma-huang has been associated with 54 deaths, primarily involving cranial hemorrhage or stroke.28,117 Echinacea increases potential for liver damage when used with steroids. Gingko biloba and feverfew interfere with anticoagulants such as warfarin (Coumadin).53 Dong quai root, willow bark, goldenseal, guarana, horse chestnut, and bilberry tablets/supplements also have antiplatelet properties.242 Ginseng may cause rapid heartbeat and/or high blood pressure in some individuals, as well as coagulation disruption. Vitamin E has antiplatelet properties and inhibits vital clot formation. Gingko and selenium are powerful anticoagulants, three times stronger than vitamin E. In 1998, California investigators found about one third of 260 imported Asian drugs were either spiked with unlisted drugs or contained mercury, lead, or arsenic. In 2009, the FDA warned of 70 weight loss pills containing potentially harmful drugs unlisted on their labels.

A Los Angeles police officer who experienced a crippling stroke after taking an ephedra-based energy supplement, Dymetradine Xtreme, was awarded $4.1 million.20 The retail store owner had read but disregarded 30 journal articles warning of strokes, heart attacks, seizures, and other ailments. The stroke occurred before the FDA banned ephedra from sale in April 2004. Nonetheless, Internet sales proliferated.242

The formulations for herbal supplements—or botanicals, as they are correctly called—such as St. John’s wort and echinacea are often complex, highly variable, and impure. Many are toxic, carcinogenic, or otherwise dangerous. Side effects include blood-clotting abnormalities, high blood pressure, life-threatening allergic reactions, abnormal heart rhythms, exacerbation of autoimmune diseases, and interference with life-saving prescription drugs.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists has warned patients to stop taking herbal supplements at least 2 weeks before surgery to avoid dangerous interactions with anesthesia.

Congress exempted supplements from oversight under a 1994 law that prevents federal regulators from requiring manufacturer’s proof that botanicals are safe or effective, or even that dosage information on the label is correct. In 1999, the FDA allowed manufacturers to make dubious health claims, such as for products to treat conditions such as premenstrual syndrome and acne, although only a few botanicals are proven efficacious for anything.

MedWatch

Newly marketed drugs may not list all potential adverse drug reactions or events because of the limited number of patients in research trials before marketing. Therefore the FDA’s MedWatch program encourages clinicians to report known or suspected drug reactions. MedWatch encourages reporting of serious unexpected adverse drug reactions whose nature and severity are inconsistent with or absent from the drug’s labeled warnings.87-90196 Clinician reporting to the FDA is confidential and voluntary. The patient’s identity need not be disclosed. Clinicians should contact the FDA by telephone at (800) FDA-1088 or fax at (800) FDA-0178 to obtain the FDA Medical Products Reporting Program (MedWatch) form (FDA form #3500). The back portion of the Physicians’ Desk Reference (PDR) contains a MedWatch form. Clinicians can also download the MedWatch reporting form at http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/getforms.htm and report suspected drug interactions, reaction, or adverse product events at http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/report.htm. Other electronic drug databases are available to report and access important drug interaction information.275 For FDA-approved safety-related drug labeling online, see www.fda.gov/MedWatch.

Adverse drug reactions are injuries occurring when drugs are administered at usual doses. These reactions represent the primary focus of regulatory agencies and postmarketing surveillance. An adverse drug event suggests medication prescribing or dispensing errors that compromise patient safety. Unfortunately, clinicians report only between 1% and 5% of adverse drug incidents to the FDA, since clinician reporting is voluntary.150 On the other hand, drug manufacturers must report known adverse drug incidents to the FDA.88

Clinicians should document adverse drug reactions not only in the progress notes but also in the allergy section of the chart in order to assess whether future use of the same drug is contraindicated and to prevent a harmful recurrence. Predictable adverse drug reactions that manifest should also be recorded as consideration for future disuse of the involved particular drug.

Endodontics and Heart Disease

Associations between chronic infections such as periodontal diseases and coronary heart disease (CHD) have been suggested.226 Conversely, supporting evidence linking root canal–filled teeth or teeth with periapical disease to CHD is lacking.94

Abbreviations

Abbreviated records can be frustrating if the clinician is unable to decipher one’s own or other clinicians’ handwritten entries, so the clinician should use standard or easily understood abbreviations. Pencil entries are legally valid, but ink entries are less vulnerable to a plaintiff’s claim of erasure or alteration. A short pencil is better than a long memory; records remember, but patients and clinicians may forget.

A sample of a completed endodontic chart (see Fig. 11-9) illustrates its proper use. Box 11-1 lists a key to the abbreviations.

BOX 11-1 Standard Abbreviation Key

| Ab | = | Antibiotic |

| ABS | = | Abscess |

| access | = | Access cavity |

| AG or AmAL | = | Amalgam |

| AE | = | Air embolus |

| analg. | = | Analgesic |

| apico | = | Apicoectomy |

| B-U | = | Buildup of tooth |

| Bisp | = | Bisphosphate |

| BW | = | Bite wing |

| canal | = | Identify canal that has been cleaned and shaped |

| CBCT | = | Cone-beam computed tomography |

| comp | = | Composite |

| cotton | = | Placed in pulp chamber between treatments |

| CRN | = | Crown |

| Dx | = | Diagnosis |

| ENDO | = | Endodontics |

| EPT | = | Electric pulp test |

| epin | = | Epinepherine |

| final | = | Final file |

| Fx | = | Fracture |

| G.G.B. | = | Gates-Glidden bur |

| G.P. | = | Gutta-percha |

| I & D | = | Incision and drainage |

| I.P. | = | Irreversible puplitis |

| L.A. or local | = | Local anesthetic |

| mm | = | Millimeters |

| O+D | = | Open and drain |

| P.A. | = | Periapical |

| perio | = | Periodontal |

| post | = | Preformed, custom, or transilluminated post |

| pt | = | Patient |

| pulpec | = | Pulpectomy |

| R.D. | = | Rubber dam |

| Rel occ | = | Relieved occlusion |

| resorp. | = | Resorption |

| retro | = | Retrograde procedure |

| S/R | = | Suture removal |

| s.file | = | Serial filing |

| S/D | = | Single insurance or dual coverage |

| sealer | = | Sealer type used |

| sepr | = | Separated |

| sutr | = | Suture |

| SX | = | Symptom |

| tech. | = | Technique for canal obturation |

| temp | = | Temporary restoration |

| test | = | Test file |

| Tx | = | Treatment |

| WNL | = | Within normal limits |

Computerized Treatment Records

Clinicians are increasingly using computerized record storage as described in Chapter 29. To avoid a claim of record falsification, whatever computer system is used should be able to demonstrate that records indicating earlier treatment were not recently falsified. Software technology, such as the “write only read memory” (WORM) system, used to identify computer data tampering, is not foolproof because it cannot detect tampering where an entire disk of recent origin has been substituted for an earlier version. Periodically, a hard copy of computer data should be printed out, hand-initialed, dated in ink, and stored in the chart to provide written verification of the computer records if the office is not a virtual paperless office.246

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

The Department of Health and Human Services’ Security and Electronic Signature Standards rule is part of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. This act emphasizes the safeguarding of clinicians’ health care information and permits a patient to obtain a copy of the requesting patient’s records. Most states have authorized digital electronic signatures as binding for most contracts and orders. Digital signatures with electronic transactions are authorized by the Third Millennium Electronic Commerce Act (also called the Electronic Signature in Global and National Commerce Act).255

Pertinent HIPAA requirements stipulate that:

Record Size

Although there is little harm in recording too much information, there is great danger in recording too little. Standard  × 11 inch or larger clinical records possess the advantage of providing the treating clinician adequate space for clinical notes.

× 11 inch or larger clinical records possess the advantage of providing the treating clinician adequate space for clinical notes.

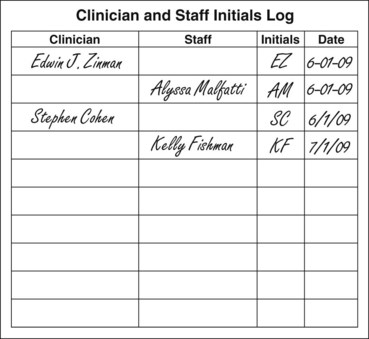

Identity of Entry Author

Either a clinician or an auxiliary can chart clinical entries unless state law indicates otherwise. Some states require clinicians and assistants to sign or initial each treatment entry.39 What is important is that the correct clinical information is recorded. Each person who makes a clinical chart entry should record the date and initial the entry. Otherwise, the author’s identity may be forgotten if the individual who recorded the entry is needed in a legal proceeding. For instance, initialing the entry makes it easier to identify the particular clinician or auxiliary who, after the original recording, is now employed elsewhere. A separate log of clinician and staff initials should be created and stored for later comparison to identify the entrant’s initials (Fig. 11-9).

Patient Record Request

Patient requests for record transfers or copies must be honored. It is unethical to refuse to transfer patient records, on patient request, to another treating clinician.10

Moreover, refusing to provide patient records is illegal in some states, subjecting the clinician to discipline and fines should the records not be provided to the patient on written request, even if an outstanding balance is owed.42

Patient Education Pamphlets

Patient education pamphlets may be used in litigation as evidence that a patient was properly informed and given endodontic alternatives but instead chose extraction. Such pamphlets include the American Dental Association’s (ADA’s) Your Teeth Can Be Saved by Endodontic Root Canal Treatment or the American Association of Endodontists’ (AAE’s) Your Guide to Endodontic Treatment, Your Guide to Endodontic Retreatment, and Your Guide to Endodontic Surgery. The clinician should indicate in the patient’s chart which particular pamphlets the patient was provided or which video was shown, since this may prove useful should the patient later deny being informed of endodontic alternatives.

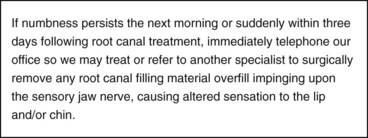

Postoperative Instructions

It is unlikely a patient will remember oral postoperative instructions unless accompanied with written instructions. After endodontic procedures, the patient may be sedated or affected by analgesic drugs. Accordingly, written postoperative instructions are beneficial. Emergency phone numbers to contact the treating clinician should be included on the form. Written instructions reduce postoperative morbidity and pain and improve patient compliance.4 Document that both written and oral postoperative instructions were provided. If treating in close proximity to the inferior alveolar nerve canal (IANC), place a precaution, such as seen in Fig. 11-10, in the postoperative instruction sheet.

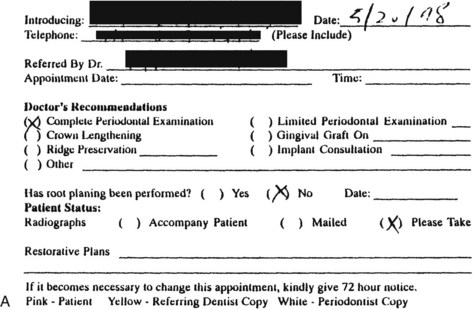

Recording Referrals

Every clinician, including the endodontic specialist, has a duty to refer under appropriate circumstances. If consultations with additional experts or specialists become necessary, referrals should be recorded lest they be forgotten or refused. Carbonless, two-part referral cards allow the clinician to provide an original referral slip to the patient while retaining a copy for the patient’s chart. The clinician or staff member should document the fact that the original referral card was given to the patient and record the name of the person who provided the referral card and the date on which it was provided. Document if mailed to the patient. A copy of the referral card should also be sent to the referred doctor. If the patient fails to keep the referral appointment, this copy will provide proof that a referral was made. The clinician should request that the patient and the referred clinician report back if the referral appointment is canceled. Staff should calendar to verify that the referral consultation occurred.

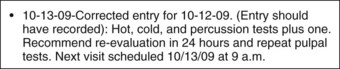

Record Correction

Records must be complete, accurate, legible, and dated. All diagnosis, treatments, and referrals should be recorded. Chart additions may expand, correct, define, modify, or clarify (as long as they are currently dated to indicate a belated entry).

To correct an entry, the clinician should make a line through (but not erase or obscure) the erroneous entry. The correction should then be written on the next available line and dated. Handwriting and ink experts use ink chemical tags, age dating, and infrared technology to prove falsified additions, deletions, or substitutions. If records are proved to be falsified, the clinician may be subject to punitive damages in civil litigation. In addition, the clinician may be subject to license revocation for intentional misconduct.39 Professional liability insurance policies may defend but will usually not indemnify punitive damages if the clinician is found to have committed fraud or deceit.43,45 In addition, insurance carriers may deny renewal of professional liability coverage to a clinician who fraudulently alters dental records.

If an erroneous entry occurs, the clinician should add another entry dated as a late entry to demonstrate later corrected information. Fig. 11-11 gives an example of the proper method of belated record correction.

When patient records have been requested or subpoenaed, it is wise to refrain from examining in detail prior to copying to avoid the temptation to clarify or belatedly add an entry. Alteration of clinical records is a cause of large settlements.

Spoliation

Spoliation is the destruction or significant alteration of evidence, or the failure to preserve property for another’s use as evidence, in pending or reasonably foreseeable litigation under Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(b)(2)(C).78

Spoliation occurs when the wrongdoer alters, changes, or substitutes dental records in an attempt to defeat a civil lawsuit.47,258 It is far easier to defend a dental negligence lawsuit with poor records compared to attempting to justifiably defend altered (falsified) records. A jury and/or a judge will likely conclude the clinician acted with consciousness of guilt for falsifying records compared with excusing staff clerical oversight if records are poorly maintained. Dental records, like all business records, deserve accuracy and completeness.

Questioned document experts utilize ink age dating, examine watermarks, or apply infrared techniques to ascertain substituted pages and additions or deletions in records, including prior erasures, entries underneath whiteouts, and indentations made when one page is overwritten on another page. Infrared technique analyzes these patterns of indentations underneath the altered pages that detect belated second entries. In one case, the defendant clinician claimed a written referral was made to a specialist in 1998, but the patient refused the referral. During litigation, the patient denied the referral and subpoenaed records of the print shop where the specialist’s referral forms were printed. These subpoenaed records proved the carbon copy of the form used for the purported 1998 referral was instead first printed in 2000, which was 2 years after the alleged referral was made (Fig. 11-12, A-B).

In another example, altered records were detected in nine different entries in one medical negligence case involving an undiagnosed malignancy. The physician’s carrier subsequently settled for $1 million. Also, the defendant personally paid a separate fine to the court. As part of the settlement, the defendant authored an article for the Washington Medical Association detailing why records falsification is wrong.17

Records are subjected to (1) audits by insurance carriers for documentation that treatment was performed, (2) review by peer review committees, and (3) subpoena by state licensing boards or agencies for disciplinary proceedings. Accordingly, falsified records expose the clinician not only to civil liability for professional negligence but also to criminal penalties for criminal offenses, such as insurance fraud.47,251,255,258,260

Deliberate record alteration with intent to deceive may also subject the clinician to licensing39 and ethical discipline as well as punitive damages for deceitful misconduct. Insurance carriers may defend but not indemnify a verdict for intentional material alteration of dental records done with intent to deceive.

Digital radiography may have dental advantages, but because the digital images originally may be computer manipulated, they may be legally suspect as altered.137,251 Therefore, hard copies of the digital images may also be printed and dated in ink to show the informational baseline upon which the clinician based diagnostic or therapeutic decisions. This also protects against computer glitches, such as disk drive crashes, electrical power surges, computer viruses, and operator delete errors.

False Claims

Performing or billing for unnecessary endodontic therapy, such as prophylactic endodontic therapy with every crown preparation, subjects the clinician to fraud. In non–pulpal exposure crown preparation, the likely incidence of subsequent endodontic therapy is approximately 3%. Therefore performing prophylactic endodontics on the other 97% of patients represents unnecessary and therefore fraudulent treatment. Excessive treatment also ethically violates the Hippocratic Oath of “primum non nocere” (i.e., “first, do no harm”).

The Federal False Claims Act carries both civil and general penalties of treble damages, fines, and attorneys’ fees for fraudulently billing government programs, such as CHAMPUS (Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services) or Medicare. Fines between $5000 and $10,000 per claim form apply if the U.S. mail was used for a false-claim submission. If any portion of the claimed treatment was fraudulently misrepresented, even if a small minority, a violation results.258 Fraudulent intent need not be conclusively proved. Reckless disregard for the accuracy of submitted data is all that is necessary to obtain a federal criminal conviction or prove civil wrongdoing.252

Legal Responsibilities

Malpractice Prophylaxis: Importance of Records

Good clinicians keep good records. Records represent the single most critical evidence a clinician can present in court as confirmation that an accurate diagnosis, proper planned treatment, and informed consent were provided.

Prevention is the goal of modern dental care. Competent endodontic treatment performed within the requisite standard of care not only saves endodontically treated teeth but also helps prevent a lawsuit for professional negligence. Thus sound and carefully applied endodontic principles protect both patient and clinician. Prudent practices reduce avoidable and unreasonable risks associated with imprudent endodontic diagnosis or therapy.

Standard of Care

Good endodontic practice, as defined by the courts, is the standard of reasonable care legally required to be performed by a reasonably careful clinician. The standard of care does not require perfection; instead, the legal standard is the reasonable degree of skill, knowledge, and care ordinarily possessed and exercised by reasonably careful clinicians under similar circumstances.140

Although the standard of care is flexible to accommodate individual variations in treatment, it is objectively tested based on what a reasonable clinician should do. Reasonable conduct represents a minimum standard required for legal due care. Reasonable care is care based upon reasoning supported by sound science such as evidence-based peer-reviewed literature. Additional precautionary steps that rise above this minimal floor of reasonableness and reach towards the ceiling of ideal care are laudable, but they are not legally mandated. Again, the standard of care does not require perfection; nor does it require ideal endodontics. Nevertheless, prudent clinicians should always strive to achieve a higher level of care than barely or minimally adequate care. Excellent clinicians always strive to do their best and practice endodontics at the highest level. Some have criticized this concept by contending that average care is below average, since 49% of clinicians practice as a minority compared to the majority of clinicians. Careful clinicians should strive to avoid the mediocrity of minimally acceptable care and instead zealously pursue a goal of endodontic excellence.

The written policies and procedures of a clinician, institution, or organization may be used as evidence of standard of care. An expert may consider these the appropriate standard of care in testifying about alleged breaches of standard of care on that issue. For instance, an expert may rely upon AAE’s 1998 position paper on paraformaldehyde-containing root canal filling materials as substandard practice, as well as the fact that all U.S. dental schools teach that toxic paraformaldehyde substances should not be used for adult patients as a root canal obturant.

Health Maintenance Organization Care versus Standard of Care

Reasonably careful or prudent practitioners (not insurance carriers) set the standard of care. Third-party payers may limit reimbursement but should not limit access to quality care. Clinicians have an affirmative duty on behalf of patients to appeal insurance carrier care denial decisions and, in some states, are protected against retaliation.267 The clinician who complies (without protest) with restrictive limitations or denials imposed by a third-party payer when sound judgment dictates otherwise cannot avoid ultimate responsibility for the patient’s care.267

Although dental insurance companies do not set the standard of care, insurance carriers may contractually limit dental benefits. Therefore a clinician is obligated to inform patients of their dental needs, regardless of carrier reimbursement. Patients may then elect to pay out of pocket or decline uninsured services. Informed choice is uninformed if the clinician fails to provide patients with all reasonable options and alternatives.171

If an insurance carrier denies endodontic therapy or limits endodontics to only certain clinical conditions, a prudent clinician must provide informed consent to the patient both legally and ethically that a tooth may be endodontically treated and retained rather than extracted.51,181,233,245,281 The California Dental Association’s Dental Patient Bill of Rights advises patients that “You have the right to ask your clinician to explain all treatment options regardless of coverage or cost.”41

Clinicians may agree to a discounted fee with a health maintenance organization (HMO) carrier but must never discount the quality of care provided. Peer review and the courts recognize only one standard of care. A lower, double, or different standard of care for reduced-fee HMO plans is not legally recognized. Expediency should not be exercised at the expense of quality patient care. Section Three of the ADA Code of Ethics affirms, “Managed care contract obligations do not excuse clinicians from their ethical duty to put the patient’s welfare first.”

An Illinois appellate court held that a clinician may be sued for injuries a patient experiences as a result of the clinician’s failure to disclose a contractual arrangement with the patient’s HMO that creates financial incentives to minimize diagnostic tests and referrals to specialists. The court recognized a distinct cause of action for breach of fiduciary duty for failure to disclose these types of financial incentives.192 In reaching its conclusion, the court cited an American Medical Association (AMA) ethics opinion that stated that a clinician must ensure that a patient is aware of financial incentives through which health insurers limit diagnostic tests and treatment options.

Managed care organizations use a variety of strategies to influence the practice styles of providers. One of the most controversial of these methods is the use of financial incentives designed to limit referrals to specialists. Such financial incentives usually take the form of bonus payments drawn from surpluses in risk pools funded by “withholds.” These funds are deducted from the primary care provider’s base payments or otherwise reserved under contracts in which the care provider bears financial risk. Such bonuses are based on referral limitations.111

Plans that delay treatment approval, resulting in endodontic complications or tooth nontreatability, may be subject to liability.193,245 HMO carriers have not always succeeded in arguing that the 1974 Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) preempts state law for dental negligence claims against entities who administrate health care benefits to an ERISA plan and shift blame to the clinician.200

Capitation systems have a built-in incentive to undertreat, delay, or discourage treatment and access to care. For the HMO-paid clinician, the patient may be perceived as a threat to profits. Thus capitation creates incentives that can transform clinicians from the patient’s advocate to the patient’s adversary.

Although clinicians seem like double agents serving two masters (i.e., managed care carriers and patients), the law is clear that the clinician must always act in the patient’s best interest, since the clinician owes a fiduciary obligation to the patient. Should the carrier deny requested care, the clinician is legally obligated to appeal the decision to protect the patient’s dental health.267 A patient’s best interest is always paramount, both legally and ethically, to a clinician’s financial interest.97,268

Although profitable to insurance carriers, the success of denying or limiting benefits has created an era of rightfully indignant patients and frustrated clinicians. Consequently, the clinician must guard against patient disappointment with limited insurance benefits by explaining that although insurance carriers determine coverage under their patients’ insurance policy, carriers do not set the standard of care. Regardless of how much or how little is covered by the patient’s insurance carrier, prudent and reasonably careful clinicians set the standard of care. Providing less than necessary care because of insurance carriers’ dictates may explain resulting deficient endodontics but does not excuse such conduct. Moreover, the legal doctrine of informed consent mandates the patient be informed of alternative therapy choices which the patient may pay privately even though the HMO denies approval for alternative therapies. Follow the maxim: Do not x-ray a patient’s pocketbook. Reasonable informed consent is primarily based upon patient choice and not cost alone.

Dental Negligence Defined

Dental negligence is defined as a violation of the standard of care (i.e., an act or omission that a reasonably careful or prudent clinician under similar circumstances would not have done).140 Negligence is equated with carelessness or inattentiveness.145 Malpractice is a lay term for such professional negligence. Dental negligence occurs for two reasons:

One simple test to determine if an adverse outcome results from negligence is to ask the following question: Was the treatment result reasonably avoidable? If the answer is “yes,” it is probably malpractice. If the answer is “no,” it is instead an unfortunate maloccurrence that resulted despite reasonable care attempts.

Not all examples of negligent endodontic treatment are included in this chapter, because the myriad of malpractice incidents far exceeds its scope and length. Rather, only select examples are elucidated for educational purposes.

Locality Rule

The locality rule, which provides for a different standard of care in different communities, is rapidly becoming outdated. Originating in the 19th century, the rule was designed to acknowledge differences in facilities, training, and equipment between rural and urban communities.161,282

The trend across the United States is to move from a locally based standard to a statewide standard, at least for generalists. For endodontists, a national standard of care is applied, since the AAE Board is national in scope.235 Because of nationally published endodontic literature, advances in Internet communication, continuing education courses, and reasonably available transportation for patients, no disparity generally exists between rural and urban endodontic standards. A current exception may be the limited geographic availability of specific cone-beam CT technology such as the Accuitomo or Kodak 9000. Their higher resolution provides superior radiographic endodontic diagnosis compared with 2D imaging and even other CBCT devices.* As CBCT machine pricing is lowered and availability increases, the locality rule may be broadened beyond a local community for CBCT technology. On the other hand, time is critical if an endodontic overfill enters the IANC.206 In such instances, a referral to a distant CBCT facility may be required to assess the need for immediate microsurgical removal or instead obtain at the very least a medical CT in the local geographic area.

A clinician should provide reasonably careful endodontic care to a patient regardless of treatment locality. Rather than focusing on different standards for different communities, more important considerations include knowledge of endodontic advances in the field gained with continuing education to utilize improved diagnostics, instrumentation, and therapeutic interventions.

The locality rule has two major drawbacks. In areas with small populations, clinicians may be reluctant to testify as expert witnesses against other local clinicians. Also, the locality rule allows a small group of clinicians in an area to establish a local standard of care inferior to what the law requires of larger urban areas. Peer-reviewed publications are available to all clinicians in print and online. Clinicians can easily travel great distances to attend continuing education courses or attend webcasts in their own office; to blame technologic ignorance on a clinician’s rural location is inexcusable with modern media, computer technology, and travel ease.

Standards of Care: Generalist versus Endodontist

A general practitioner performing treatment ordinarily performed exclusively by specialists, such as apical endodontic surgery, periodontal surgical grafting, or full bony impaction surgery, will be held to the specialist’s standard of care.103,104 To avoid performing treatment that is below the specialist’s standard, a generalist should refer to a specialist rather than perform procedures that are beyond the general practitioner’s training or competency. The three levels of clinical skill are (1) competency or beginning level, (2) proficiency, and (3) mastery. To err is human. Even specialists may not always know what they believe they know.74,145 Approximately 80% of general practitioners in the United States provide some endodontic therapy. Endodontic expansion into the realm of the generalist can be linked to (1) refinements in root canal preparation and improved obturation (i.e., packing) techniques currently taught in dental schools; (2) continuing education courses; and (3) significant improvements in the armamentarium of instruments, equipment, and materials available to all clinicians.

Ethical Guidelines

The ADA’s Code of Ethics guides conduct that distinguishes the dental profession from a trade by placing patient service paramount and profit secondary.97 Section 5 of the ADA Code of Ethics regarding veracity (“truthfulness”) states that “Professionals have a duty to be honest and trustworthy in their dealings with people.” Accordingly, both ethically and legally,129 clinicians are obligated to communicate truthfully and without deception to patients. Announcements to the public must be truthful so that the average person is not materially misled. Truth in dentistry is the rule and not the exception.97

Section 5.I of the ADA Code of Ethics provides: General Practitioner Announcement … general clinicians who wish to announce the services available in their practices are permitted to announce the availability of those services so long as they avoid any communications that express or imply specialization. Thus clinicians should not misrepresent or overstate the facts of their training and competence in any way that would be false or misleading in any material or significant manner to the public or their peers. General clinicians should avoid false and misleading self-representation regarding endodontic “superiority.” Implying credentials which the generalist lacks misrepresents a general clinician’s endodontic skill and knowledge as equivalent to a board-eligible or board-certified endodontist. A generalist’s 30-year experience may be little more than 1 year’s experience repeated 30 times. Every state has specific laws governing advertising. Consult your state’s law, because each state deals differently with specialty announcements.

Telephone directory listings are organized into categories based on types of procedure, such as endodontics. Generalists must also state in such ads that endodontic services are being provided by general clinicians. The public is entitled to be informed of the distinction between an endodontist specialist versus a generalist, although each provide endodontics. Only a board-eligible or board-certified clinician is entitled to represent that the clinician is an endodontist. With this distinction in mind, the ADA-recognized endodontic specialty organization is entitled the American Association of Endodontists, not the American Association of Endodontics.

Standard of Care for Endodontics

Endodontists set the standard for routine endodontics. Therefore if the endodontist’s standard of care cannot be met, such as the need for microscopy, the generalist should refer the patient to an endodontist.55,103,104,149

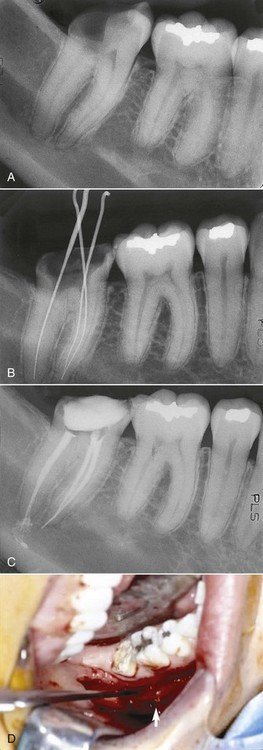

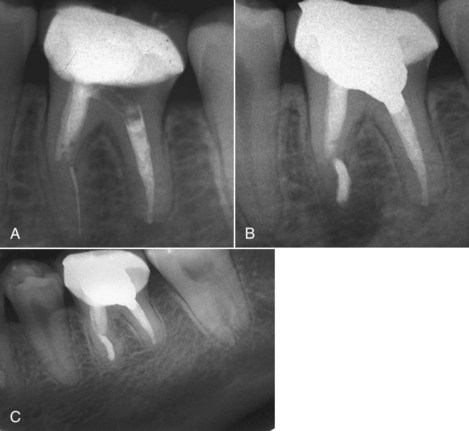

Endodontists should not forget their general clinician training. Even though a patient may be referred for a specific procedure or undertaking, the endodontist should not overlook sound biologic principles inherent in the overall treatment. A specialist may also be held liable for relying solely on the information referral card or radiographs of the referring clinician if the diagnosis or therapeutic recommendations prove incorrect, unnecessary, or the referral card lists the wrong tooth for treatment. Fig. 11-13 demonstrates a general clinician’s radiograph showing apparent complete endodontic fill within the canal space, whereas Fig. 11-14 demonstrates an endodontist’s radiograph showing a transported canal. This difference is explained by radiographic quality and angulation. Taking radiographs at different angles improves radiographic accuracy.163,166

FIG. 11-13 A general clinician’s radiograph that ostensibly shows a complete endodontic fill within the root canal space.

Endodontists should not provide rubber-stamp treatment to whatever the clinician refers or recommends. Without performing an independent examination, the endodontist risks misdiagnosis and resulting incorrect treatment. Prevention of misdiagnosis or incorrect treatment requires an accurate medical and dental history preceding a clinical examination (not only of the specific tooth or teeth involved but also of the general oral condition). Obvious problems such as oral lesions, periodontitis, or gross decay should be noted in the chart and the patient advised regarding a referral for further examination, testing, or another specialist’s consultation.

Radiographs from the referring clinician should be reviewed for completeness, clarity, and diagnostic accuracy. An endodontist should expose a new radiograph to verify current status before treatment and only use the referring clinician’s radiograph for historical comparison. Unfortunately, the referring clinician may surreptitiously forward a pretreatment film with the referred patient, rather than the referring clinician’s own posttreatment film depicting a perforation or broken file that necessitated the referral. This may occur whenever an errant clinician attempts to fraudulently conceal negligently performed endodontic treatment in an attempt to shift blame for bungled treatment to the endodontist. In such cases, a valuable lesson is learned when the endodontist exposes independent pretreatment radiographs, rather than relying exclusively on the referring clinician’s radiographs to determine current status of endodontic treatment.

Poor oral hygiene may contribute to periodontal disease. In such cases, endodontic treatment may be compromised unless the associated periodontal condition, along with the tooth being tested endodontically, is brought under periodontal disease control, including any crown-lengthening needs (see Chapter 18 for more information). Referral to a periodontist may be necessary before or contemporaneous with completion of endodontic treatment.

In summary, it is necessary for the endodontist to:

Ordinary Care Equals Prudent Care

Ordinary is commonly understood (outside its legal context) to mean “lacking in excellence” or “being of poor or mediocre quality.”179 As expressed in the context of actions for negligence, however, ordinary care has assumed a technical legal definition somewhat different from its common meaning. The eighth edition of Black’s Law Dictionary describes ordinary care as “that degree which persons of ordinary care and prudence are accustomed to use or employ … that is, reasonable care.”31

In adopting this distinction, the courts have defined ordinary care as “that degree of care which people ordinarily prudent could be reasonably expected to exercise under circumstances of a given case.”83 It has been equated with the reasonable care and prudence exercised by ordinarily prudent clinicians under similar circumstances.107,213 It is not extraordinary or ideal care. Thus ordinary care is not average care but instead equates with prudently careful care. Stated otherwise, average care may be below the average of what all reasonable clinicians should practice.

Although the standard required of a professional cannot be only that of the most highly skilled practitioner, neither can it be limited to the arithmetic-average member of the profession, because those who possess somewhat less than median skill may still be competent and qualified to treat.213 By such an illogical definition of average care, half of all clinicians would automatically fall short of the mark and be negligent as a matter of law. As one court explained, “We are not permitted to aggregate into a common class the quacks, the young men who have not practiced, the old ones who have dropped out of practice, the good, and the very best, and then strike an average between them.”227 Thus the standard of care equates with reasonable and not average care.

Customary Practice versus Negligence

Customary practice may constitute evidence of the standard of care, but it is not the only determinant. Moreover, if the customary practice constitutes negligence, it is not considered reasonable (although or even if customarily practiced by a majority of clinicians).26 Rather, the reasonably careful clinician is the standard of care and not an average or mediocre practitioner. For instance, a majority of clinicians did not perform biologic testing of the dental unit water lines despite ADA recommendations to do so.181,183 However, careful clinicians did follow the ADA’s recommendation (Box 11-2 and Fig. 11-15).

BOX 11-2 Typical Examples of Negligent Customs